Abstract

Ribosomal proteins are the building blocks of ribosome biogenesis. Beyond their known participation in ribosome assembly, the ribosome-independent functions of ribosomal proteins are largely unknown. Here, using immunoprecipitation, subcellular fractionation, His-ubiquitin pulldown, and immunofluorescence microscopy assays, along with siRNA-based knockdown approaches, we demonstrate that ribosomal protein L6 (RPL6) directly interacts with histone H2A and is involved in the DNA damage response (DDR). We found that in response to DNA damage, RPL6 is recruited to DNA damage sites in a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)–dependent manner, promoting its interaction with H2A. We also observed that RPL6 depletion attenuates the interaction between mediator of DNA damage checkpoint 1 (MDC1) and H2A histone family member X, phosphorylated (γH2AX), impairs the accumulation of MDC1 at DNA damage sites, and reduces both the recruitment of ring finger protein 168 (RNF168) and H2A Lys-15 ubiquitination (H2AK15ub). These RPL6 depletion–induced events subsequently inhibited the recruitment of the following downstream repair proteins: tumor protein P53-binding protein 1 (TP53BP1) and BRCA1, DNA repair-associated (BRCA1). Moreover, the RPL6 knockdown resulted in defects in the DNA damage–induced G2–M checkpoint, DNA damage repair, and cell survival. In conclusion, our study identifies RPL6 as a critical regulatory factor involved in the DDR. These findings expand our knowledge of the extraribosomal functions of ribosomal proteins in cell physiology and deepen our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying DDR regulation.

Keywords: DNA damage response, ubiquitylation (ubiquitination), DNA repair, cell signaling, E3 ubiquitin ligase, histone, histone H2A, MDC1, PARP, Ribosomal Protein L6

Introduction

The eukaryotic ribosome consists of approximately 80 ribosomal proteins (r-proteins) and rRNAs (1). Ribosome biogenesis is a tightly regulated process closely associated with cell growth and division. The process of ribosome biogenesis involves pre-rRNA synthesis and processing, r-protein synthesis and nuclear-cytoplasm transport, and ribosome assembly (2–4). R-proteins are transcribed in the nucleus by RNA polymerase II and are translated in the cytoplasm. Newly synthesized r-proteins are imported into the nucleus and assembled with rRNAs into large and small subunits within the nucleus (5, 6).

In addition to their role in ribosome biogenesis, r-proteins also have functions independent of the protein translation machinery. For example, several r-proteins play important roles in regulating p53 activity in response to nucleolar stress (7–9). Nucleolar disruption induced by actinomycin D treatment leads to the release of RPL5, RPL11, and other r-proteins from the nucleoli into the nucleoplasm (10–13). Our previous studies have demonstrated similar regulatory functions of RPS14 and RPL6 in the nucleolar stress response (14, 15). These released r-proteins bind to Mdm2, suppress Mdm2 E3 activity, and stabilize and activate p53. In addition, RPL26 binds to p53 mRNA and regulates its translation activity. Recently, RPS26 has been reported to directly regulate p53 transcriptional activity in response to DNA damage (16). Knockdown of RPS26 greatly reduces the recruitment of p53 to the promoters of its target genes and inhibits p53 acetylation. It has been found that mutations in r-protein genes, including those for RPL22, RPL10, RPL5, and RPL11, lead to the dysfunction of ribosome biogenesis in cancers (17, 18). However, other ribosome-independent functions of r-proteins remain to be elucidated.

DNA damage, including DNA double-stranded break (DSB),3 can be generated spontaneously or induced by environmental factors (19, 20). When DSBs occur in cells, a cascade of reactions mediated by the DNA damage checkpoint kinases ATM and ATR are activated, and H2AX is phosphorylated at Ser-139 (γH2AX) in the vicinity of the damage sites (21, 22). MDC1 binds γH2AX and initiates an ubiquitination cascades. E3 ligase RNF8 recognizes phosphorylated MDC1 and promotes the recruitment of RNF168. Subsequently, RNF168 catalyzes H2A/H2AX monoubiquitination at Lys-13 and Lys-15 and initiates the formation of a Lys-63–linked polyubiquitin chain (20, 23–26). RNF8- and RNF168-mediated ubiquitination cascades promote recruitment of DNA damage repair proteins such as BRCA1 and 53BP1 (26–28). 53BP1 plays a critical role in promoting nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ), whereas BRCA1 antagonizes 53BP1-dependent end joining and promotes homologous recombination (HR) (35). Meanwhile, DNA damage checkpoints are activated and induce cell cycle arrest to provide more time for cells to repair the DNA lesions. Once DNA damage is repaired, cells will re-enter the normal cycle. Alternatively, if the damage is too severe to be repaired, cells will undergo apoptosis (29). The protein 53BP1 acts as a DNA damage checkpoint and is required for maintaining cell cycle arrest (30, 31).

Here, we demonstrate that the ribosomal protein RPL6 is a partner of histone H2A. Upon DNA damage, RPL6 is rapidly recruited to DNA damage sites in a PARP-dependent manner. RPL6 depletion reduces H2AK15ub and impairs recruitment of MDC1, BRCA1, and 53BP1, leading to defects in DNA repair and the G2–M checkpoint. In addition, we show that RPL6 binds to the nucleosome and promotes the binding of MDC1 to γH2AX. Our study identified RPL6 as a novel regulator involved in the DDR, which is important for understanding the extraribosomal physiological functions of ribosomal proteins.

Results

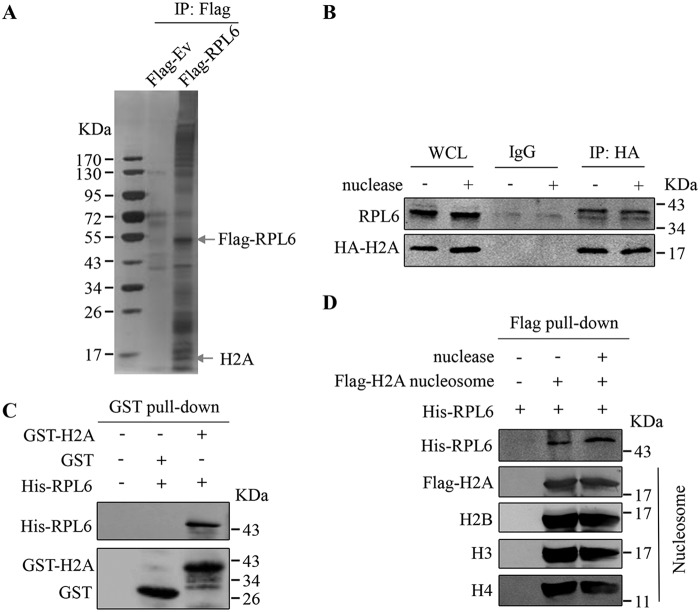

RPL6 is a direct interaction partner of H2A

To investigate the ribosome-independent functions of RPL6, immunoprecipitation assays were performed to identify new partners of RPL6 by using an anti-FLAG antibody in HEK293T cells transfected with FLAG–RPL6. Mass spectrometry analysis showed that H2A was immunoprecipitated by FLAG–RPL6 (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1). Co-IP assays confirmed the interaction between RPL6 and H2A (Fig. 1B). Moreover, the H2A–RPL6 interaction was not affected by hydrolyzing DNA and RNA using Benzonase nuclease (Fig. 1B), suggesting that RPL6 interacts with H2A independently of nucleic acids. To assess whether RPL6 directly interacts with H2A, we purified GST-tagged H2A and His-tagged RPL6 proteins in Escherichia coli and performed GST pulldown assays. The results demonstrated a direct interaction between RPL6 and H2A in vitro (Fig. 1C). Because H2A functions as a part of the nucleosome, we further extracted nucleosomes from HEK293T cells transfected with FLAG–H2A, and in vitro FLAG pulldown assays showed that RPL6 interacted with the FLAG–H2A contained in the nucleosomes independently of nucleic acids (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that RPL6 interacts with H2A under physiological conditions.

Figure 1.

RPL6 directly interacts with H2A. A, identification of RPL6 partners using IP and MS. HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged RPL6, and then co-IP assays were performed 48 h after transfection using anti-FLAG antibodies followed by SDS-PAGE and MS analysis. B, the RPL6–H2A interaction was not affected by nucleic acids. The HEK293T cells transfected with HA-H2A were treated with or without Benzonase nuclease (active against both RNA and DNA) and then subjected to co-IP assays by using anti-HA. C, RPL6 interacts with H2A in vitro. GST pulldown assays were performed by using GST, GST-H2A, and His-RPL6 proteins purified from E. coli. D, RPL6 interacts with H2A-containing nucleosomes in vitro. Nucleosome-associated FLAG–H2A was immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells with anti-FLAG antibodies and subjected to FLAG pulldown assays by incubating each sample with His-RPL6 protein purified from E. coli. WCL, whole cell lysate.

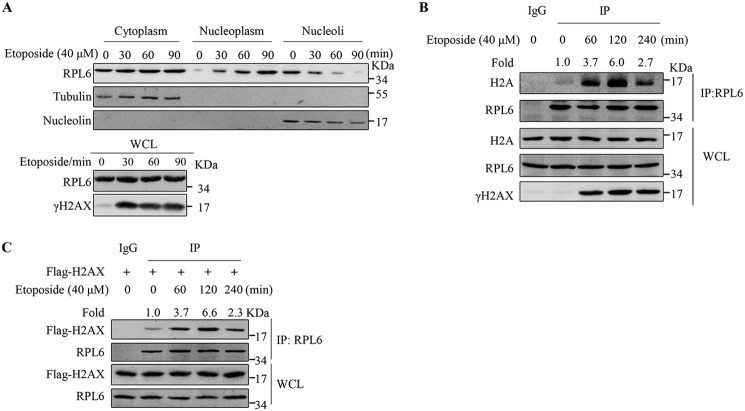

DNA damage promotes interaction between RPL6 and H2A

RPL6 is synthesized in the cytoplasm and assembled into nascent large ribosomal subunits in the nucleoli, which are then exported to the cytoplasm and processed into mature 60S ribosome subunits (32). To investigate the dynamic subcellular localization of RPL6 in response to DNA damage, cells were treated with etoposide (40 μm) to induce DSBs, and subcellular fractionation was performed. The result showed that RPL6 translocated from the nucleoli to the nucleoplasm, whereas the abundance of RPL6 in whole cell lysates and cytoplasm had no obvious change (Fig. 2A). Next, we assessed whether DNA damage influenced the interaction between H2A and RPL6 in the DDR. Co-IP assays performed using cells with or without etoposide treatment showed that the RPL6–H2A interaction increased after etoposide treatment, suggesting that more RPL6 binds to H2A in response to DNA damage (Fig. 2B). We also found that more H2AX interacted with RPL6 in response to DNA damage (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that the interaction between RPL6 and H2A/H2AX is enhanced by DNA damage.

Figure 2.

DNA damage promotes the interaction between RPL6 and H2A. A, etoposide treatment induces the subcellular translocation of RPL6 from the nucleoli to the nucleoplasm. Cells treated with 40 μm etoposide as indicated were collected and subjected to a subcellular fractionation assay. RPL6 levels in the cytoplasm, nucleoplasm, and nucleoli fractions were detected through Western blotting using the anti-RPL6 antibody. Tubulin and nucleolin served as the markers of the cytoplasm and the nucleoli, respectively. B, DNA damage promotes the interaction between RPL6 and H2A. HEK293T cells treated with 40 μm etoposide were harvested, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with anti-RPL6 antibodies. C, etoposide treatment promotes the interaction between RPL6 and H2AX. HEK293T cells transfected with FLAG–H2AX and then treated with 40 μm etoposide as indicated were harvested, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with anti-RPL6 antibodies. WCL, whole cell lysate.

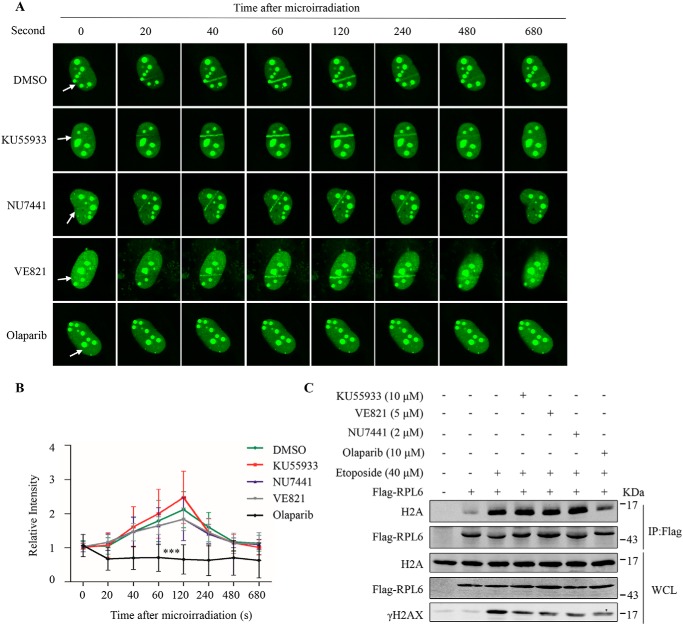

RPL6 is recruited to DNA damage sites in a PARP-dependent manner

We performed laser microirradiation analysis to screen proteins involved in the DNA damage response. Interestingly, we found that RPL6 was rapidly recruited to DNA damage sites (Fig. 3, A and B). In addition to RPL6, RPL8, and RPS14, but not RPL9, accumulated at DNA damage sites (Fig. S2). ATM, ATR, and DNA-PKcs play important roles in the DDR through a series of phosphorylation events (20). Therefore, we treated cells with ATM inhibitor KU55933, DNA-PK inhibitor NU7441, and ATR inhibitor VE821 and found that these inhibitors had no obvious effect on the recruitment of RPL6 to damage sites (Fig. 3, A and B). When DSBs occur, PARP1 and PARP2 are activated and catalyze the synthesis of PAR chains on target proteins, which are essential for recruitment of DDR factors. We also examined the effect of PARP1/2 inhibitor olaparib on RPL6 recruitment. Olaparib inhibited RPL6 accumulation at DNA damage sites, suggesting that recruitment of RPL6 depends on PARP1/2 (Fig. 3, A and B). Moreover, we assessed whether the interaction between RPL6 and H2A was affected by these inhibitors. The cells were treated with the inhibitors before etoposide treatment and subjected to co-immunoprecipitation. Consistent with the observations described above, RPL6–H2A interaction was suppressed by olaparib (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that PARP activity is required for the recruitment of RPL6 and thus interaction between RPL6 and H2A.

Figure 3.

RPL6 is recruited to DNA damage sites in a PARP-dependent manner. A and B, RPL6 is recruited to DNA damage sites in a PARP-dependent manner. U2OS cells were transfected with GFP-RPL6. At 24 h after transfection, the cells were treated with 10 μm ATM inhibitor KU55933, 2 μm DNA-PK inhibitor NU7441, 5 μm ATR inhibitor VE821, or 10 μm PARP inhibitor olaparib for 2 h, after which laser microirradiation assays were performed (A). Quantitation of the intensity within the microirradiated nuclear strip and nonmicroirradiated strip was performed, and the relative ratio of the intensities is presented as the mean ± S.D. (n = 20; B). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way analysis of variance. C, the interaction between RPL6 and H2A is PARP-dependent. HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG–RPL6. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with 10 μm KU55933, 2 μm NU7441, 5 μm VE821, or 10 μm olaparib for 2 h, followed by etoposide (40 μm) treatment. Next, the cells were harvested, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies. WCL, whole cell lysate. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

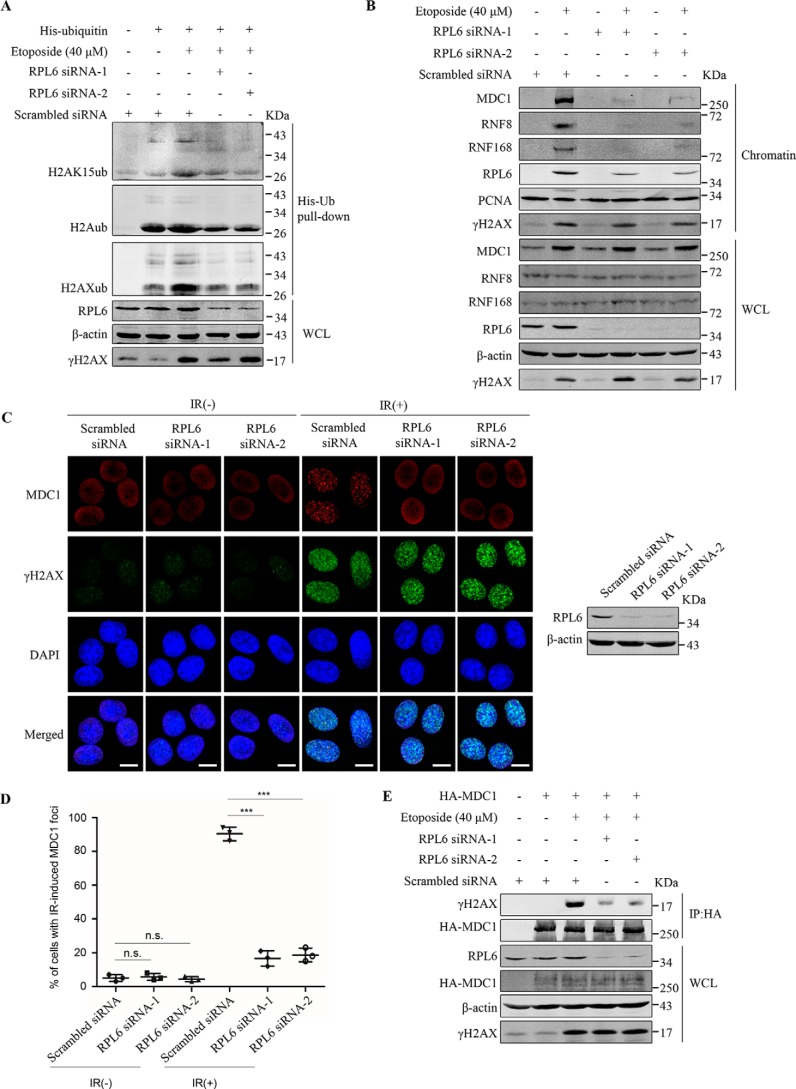

Depletion of RPL6 impairs the DNA damage response

The data above show that in response to DNA damage, RPL6 accumulates at damage sites, where it interacts with H2A. Because ubiquitination of H2A K15 induced by DNA damage plays a significant role in the recruitment of DNA repair proteins (26), we performed His-ubiquitin pulldown assays to investigate whether RPL6 affected H2A K15 ubiquitination. The results showed that H2A K15 ubiquitination increased after etoposide treatment, whereas RPL6 knockdown achieved using siRNAs impaired H2AK15ub (Fig. 4A and Fig. S3A). Moreover, knockdown of RPL6 also impaired ubiquitination of H2AX (Fig. 4A and Fig. S3A), and these effects could be rescued by co-transfection of moderate amounts of siRNA-resistant FLAG–RPL6 (Fig. S3A).

Figure 4.

Knockdown of RPL6 impairs the DNA damage response. A, RPL6 depletion impairs DNA damage–induced H2A/H2AX ubiquitination. HEK293T cells were transfected first with the indicated siRNAs, followed by His-ubiquitin. After 48 h, the cells were treated with 40 μm etoposide and harvested. The levels of H2AK15ub, H2Aub, and H2AXub were detected by His-ubiquitin pulldown analysis using the indicated antibodies. B, RPL6 depletion impairs the recruitment of MDC1, RNF8, and RNF168 to chromatin. HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs. After 48 h, the cells were treat with or without 40 μm etoposide, and chromatin was isolated. The levels of MDC1, RNF8, RNF168, and γH2AX were detected using indicated antibodies. C and D, knockdown of RPL6 inhibits IR-induced MDC1 accumulation at damage sites. HeLa cells transfected with control siRNA or RPL6 siRNAs were treated with or without IR (10 gray), and immunofluorescence analysis was performed using anti-MDC1 antibodies (red) and anti-γH2AX (green) antibodies (C). The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. Cells with ≥10 MDC1 foci (D) were quantified and presented as the means ± S.D. (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test. 100 cells in each group were counted. E, depletion of RPL6 weakens the interaction between MDC1 and γH2AX. HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated siRNAs and HA-tagged MDC1. After 48 h, the cells were treated with or without 40 μm etoposide and subjected to co-IP assay using anti-HA antibodies. DAPI, 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole; WCL, whole cell lysate. IR, ionization radiation.

Previous studies have shown that MDC1 binds to γH2AX and initiates an ubiquitination cascade (33). Therefore, we measured the effect of RPL6 on recruitment of MDC1 and downstream E3 ligases RNF8 and RNF168. Cells were transfected with control or RPL6 siRNAs and subjected to etoposide treatment to induce DNA damage, after which chromatin extraction assay was performed. RPL6 depletion had no influence on abundance of MDC1, RNF8, and RNF168 in whole cell lysates, whereas it suppressed accumulation of all the three proteins at chromatin (Fig. 4B). Consistently, immunofluorescence and microirradiation assays showed that RPL6 depletion abrogated formation of MDC1 foci after IR exposure (Fig. 4, C and D) and accumulation of MDC1 at laser-induced strip (Fig. S3, B and D). Notably, knockdown of RPL6 had no apparent effect on γH2AX level (Fig. 4, A and B) or IR-induced γH2AX foci formation (Fig. 4C). Based on the results above, we speculated that depletion of RPL6 might interfere with the recruitment of MDC1 to damage sites by γH2AX. Co-IP assay revealed that in cells transfected with RPL6 siRNAs, DNA damage–induced interaction between MDC1 and γH2AX was impaired (Fig. 4E).

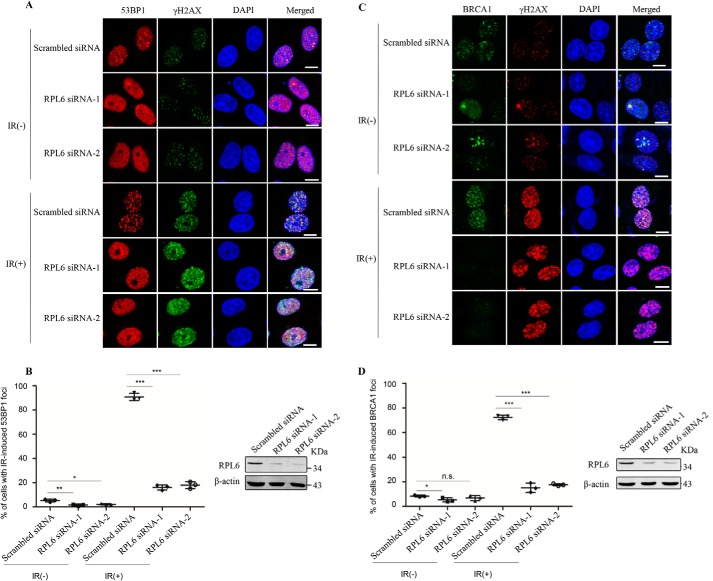

Because H2A/H2AX ubiquitination facilitates the recruitment of downstream repair proteins such as 53BP1 and BRCA1, we found that knockdown of RPL6 also reduced the abundance of 53BP1 at the laser-induced strip (Fig. S3, C and D). To confirm the effect of RPL6 on the recruitment of damage repair proteins, cells transfected with control or RPL6 siRNAs were treated with or without IR to induce DSBs and then subjected to immunofluorescence assays. Consistently, IR treatment promoted 53BP1 and BRCA1 foci formation, whereas RPL6 depletion significantly abrogated IR-induced 53BP1 and BRCA1 accumulation at DNA damage sites (Fig. 5). Taken together, these results suggest that RPL6 depletion abrogates the accumulation of MDC1 at damage sites and the subsequent recruitment of repair proteins.

Figure 5.

RPL6 depletion impairs the recruitment of DNA damage repair proteins. A–D, knockdown of RPL6 inhibits IR-induced 53BP1 and BRCA1 accumulation at damage sites. HeLa cells transfected with control siRNA or RPL6 siRNAs were treated with or without IR (10 gray), and immunofluorescence analysis was performed using anti-53BP1 antibodies (red) and anti-γH2AX (green) antibodies (A) or anti-BRCA1 (green) and anti-γH2AX (red) antibodies (C). The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. Cells with ≥15 53BP1 foci (B) or ≥10 BRCA1 foci (D) were quantified and presented as the means ± S.D. (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test. Approximately 500 cells in each group were counted. DAPI, 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole. IR, ionization radiation.

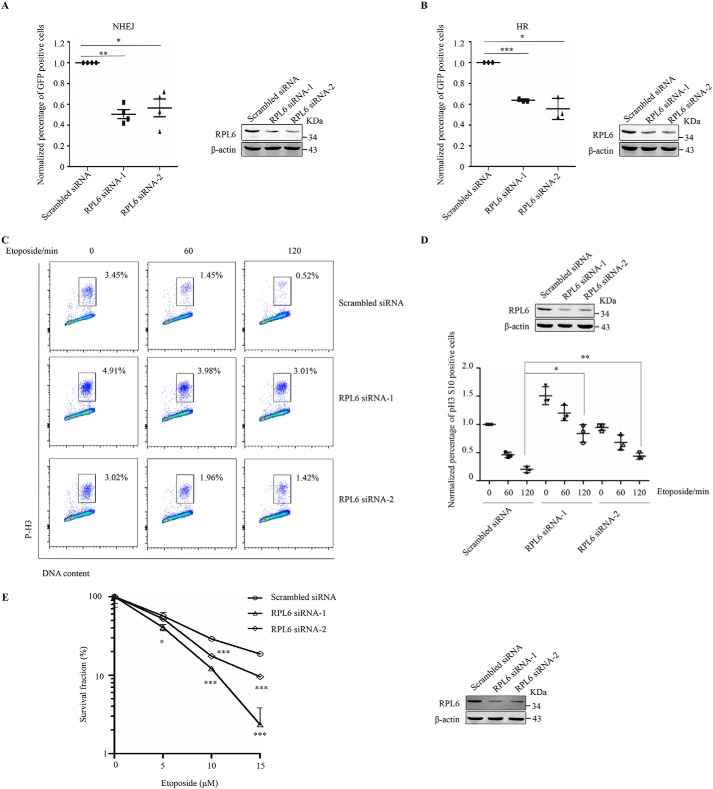

Knockdown of RPL6 results in defects in DNA damage repair, the G2-M checkpoint, and cell survival

NHEJ and HR are two major pathways utilized by mammalian cells to repair DSBs (34). 53BP1 and BRCA1 play critical roles in the selection of DNA repair pathways (35). Because RPL6 depletion impairs recruitment of 53BP1 and BRCA1, we examined DNA repair efficiency in cells treated with control or RPL6 siRNAs by performing reporter assays. RPL6 knockdown decreased the repair efficiency of NHEJ and HR (Fig. 6, A and B). 53BP1 plays an important role in DNA damage–induced G2–M checkpoint activation and prevents damaged cells from entering into mitosis (36, 37). The effect of RPL6 on 53BP1 recruitment led us to detect the effect of RPL6 on the G2–M checkpoint. Cells transfected with control or RPL6 siRNAs were treated with etoposide for the indicated time periods, after which the percentage of cells in mitosis was determined by staining with phosphohistone H3 and propidium iodide. The FACS analysis showed that, in response to DNA damage, the G2–M checkpoint was activated, and fewer cells entered into mitosis (Fig. 6, C and D). However, compared with control cells, more RPL6-depleted cells entered into mitosis, especially those treated with etoposide for 120 min, suggesting that cells with depleted RPL6 display a DNA damage–induced G2–M checkpoint defect (Fig. 6, C and D). We further assessed the effect of RPL6 on cell survival. Control or RPL6-depleted HeLa cells were treated with or without etoposide at different dosages and subjected to clonogenic survival assays. RPL6 depletion exacerbated cell death in the DDR (Fig. 6E), indicating that RPL6 is required for cell survival upon DNA damage.

Figure 6.

Knockdown of RPL6 causes defects in DNA damage repair, the G2–M checkpoint, and cell survival. A and B, depletion of RPL6 decreases the efficiency of NHEJ and HR. HEK293T cells were transfected with control siRNA or RPL6 siRNAs followed by NHEJ (A) or HR (B) reporters. FACS assays were performed at 36 h (for NHEJ) or 48 h (for HR) after transfection. The results were normalized to those of the cells transfected with control siRNA. The data are presented as the means ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test. C and D, knockdown of RPL6 increases the percentage of cells entering into mitosis. HEK293T cells transfected with control siRNA or RPL6 siRNAs were treated with etoposide for the indicated time periods. Cells in mitosis were determined by staining with propidium iodide and phosphohistone H3 (Ser-10) antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488. The percentage of cells in mitosis was measured using a FACSVerse cytometer (C). The results were normalized to those of the cells transfected with control siRNA in the absence of etoposide treatment. The data are presented as the means ± S.D. (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test (D). E, RPL6-depleted cells are more sensitive to etoposide. HeLa cells transfected with control siRNA or RPL6 siRNAs were subjected to clonogenic survival assays. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test.

Discussion

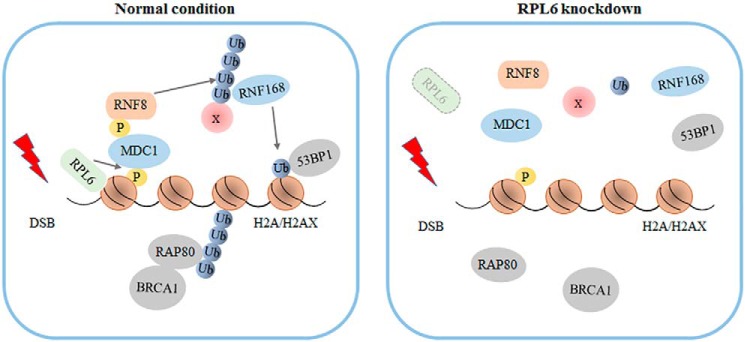

The DDR is a tightly regulated and sophisticated cascade for maintaining genome integrity, cell cycle, apoptosis, and various other physiological activities. A detailed understanding of the DDR remains to be delineated. Herein, we identified that RPL6, a component of the ribosomal large subunit, plays a vital role in regulating the DDR. DNA damage induces rapid recruitment of RPL6 to the damage sites and promotes its interaction with histone H2A. RPL6 functions upstream of ubiquitination cascades and is required for the binding of MDC1 to γH2AX (Fig. 7). RPL6 depletion impairs the recruitment of MDC1 and reduces H2A/H2AX ubiquitination, which further abrogates the accumulation of downstream repair proteins 53BP1 and BRCA1 at DNA damage sites and reduces the efficiency of HR and NHEJ, leading to defects in DNA repair, the G2–M checkpoint, and cell survival. Our study provides a novel understanding of the regulatory network of the DDR and extends knowledge of the functional territory of ribosomal proteins.

Figure 7.

A proposed model illustrating how RPL6 is involved in the DDR. In response to DNA damage, RPL6 is recruited to DNA damage sites. RPL6 facilitates the binding of MDC1 to γH2AX. MDC1 initiates RNF8-RNF168-mediated ubiquitination cascade and promotes the recruitment of DNA repair protein 53BP1 and BRCA1. Knockdown of RPL6 impairs the recruitment of MDC1 to damage sites and abrogates downstream signaling.

Recently, it has been reported that ID3 plays a critical role in recruitment of MDC1 to DNA damage sites. In response to double-stranded breaks, ID3 is phosphorylated by ATM. Phosphorylated ID3 accumulates at damage sites and promotes binding of MDC1 to γH2AX through interacting with both MDC1 and γH2AX (38). In this study, we found that RPL6 also accumulates at damage sites and is essential for interaction between MDC1 and γH2AX. However, recruitment of RPL6 is not regulated by ATM, ATR or DNA-PKcs (Fig. 3, A and B), suggesting that RPL6 may not function as a substrate in the phosphorylation cascade. In addition, we failed to detect an interaction between RPL6 and MDC1 with or without treatment of etoposide (data not shown). Based on these observations, we speculated that RPL6 regulates binding of MDC1 to γH2AX through an alternative mechanism, on which further researches are required.

Ribosomal proteins are canonically considered the basic elements of ribosomes and critical determinants for protein translation. Potential extraribosomal functions of ribosomal proteins remain poorly documented. Recently, an increasing number of studies have demonstrated the essential regulatory roles of ribosomal proteins in many ribosome-independent cellular processes. The best-known case is the nucleolar stress-induced p53 activation (15, 18, 41, 42). Under cellular stresses, including nutrition depletion and DNA damage stimuli, ribosomal proteins, such as RPL5, RPL6, and RPL11, translocate from the nucleoli to the nucleoplasm, where they bind to HDM2, stabilizing p53 (9). In addition, RPS26 forms a complex with p53 and p300, and the knockdown of RPS26 impairs DNA damage–induced p53 recruitment and acetylation (16). Our study demonstrates that RPL6 participates in the DDR. In addition, RPL8 and RPS14 are also recruited to DNA damage sites (Fig. S2), suggesting that other ribosomal proteins may be involved in this process. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the functions of different ribosomal proteins in the DDR.

In this study, we showed that RPL6 is rapidly recruited to DNA damage sites under DNA damage stress in a PARP1/2-dependent manner (Fig. 2, A and B). PARP1 and PARP2 are sensors that detect DSBs and catalyze the formation of PAR chains on substrate proteins to promote the recruitment of DDR factors. A number of target proteins of PARP1/2 have been reported, including linker histone H1 and all core histones (43, 44). Future studies are needed to identify proteins that are ADP-ribosylated and thereby promote the recruitment of RPL6 to DNA damage sites. Determination of the manner in which ADP-ribosylation regulates the interaction between RPL6 and histone H2A is of great importance because the interaction between RPL6 and H2A is also affected by PARP inhibitors (Fig. 3C).

In summary, DNA damage triggers RPL6 translocation from the nucleoli to the nucleoplasm, where it interacts with H2A/H2AX. RPL6 affects the recruitment of MDC1 and modulates DNA damage repair and the G2–M checkpoint, thus ultimately regulating cell viability upon DNA damage. This study advances the knowledge of ribosome-independent functions of ribosomal proteins and provides a comprehensive understanding of the DDR regulatory network. Given that proper DNA damage repair is critical in maintaining genome integrity and preventing tumorigenesis, the regulatory function of RPL6 identified in the DDR provides a new target in cancer therapy.

Experimental procedures

Antibodies and reagents

Mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG (F3165) and anti-HA (H9658) were purchased from Sigma, mouse anti-His (D291–3) and rabbit monoclonal anti-Actin (PM053) were purchased from MBL (Nagoya, Japan), rabbit monoclonal anti-H2A (39209) was obtained from Active Motif, rabbit monoclonal anti-γH2AX (BS4760) and anti-H2AX (BS2984) were from Bioworld, and anti-H2AK15ub (EDL H2AK15–4) was from Millipore. Mouse monoclonal anti-H2B (BE3207), anti-H3 (BE3015), and anti-H4 (BE3194) were purchased from EASYBIO. Rabbit polyclonal anti-MDC1 (ab11169) was purchased from Abcam. Rabbit polyclonal anti-53BP1 (sc-22760) and mouse monoclonal anti-BRCA1 (sc-6954) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Rabbit monoclonal phosphohistone H3 (Ser-10) (3465S) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Rabbit polyclonal anti-RNF8 (A7302) was purchased from Abclonal. Rabbit monoclonal anti-RNF168 (TA306771) was purchased from Origene. KU55933 (S1092), NU7441 (S2638), and VE821 (S8007) were purchased from Selleck. Etoposide (E1383) was purchased from Sigma. Olaparib was a gift from Dr. Dongyi Xu.

Plasmids and siRNA

The cDNA of H2A and RPL6 was cloned into the pcDNA–3FLAG vector. The prokaryotic expression vector of RPL6 was cloned into the pET28a vector, and that of H2A was cloned into the pGEX-4T-1 vector. The plasmid encoding HA-tagged MDC1 was kindly provided by Zhenkun Lou (45). The sequences of the scrambled siRNA, RPL6 siRNA-1, and siRNA-2 oligonucleotides were ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT, GCGCAAGAUUGAUCAGAAATT, and CUGCCAUGUAUUCCAGAAATT, respectively.

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T, HeLa, and U2OS cells from ATCC were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Gibco) with 10% fetal calf serum (HyClone) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Plasmids were transfected using MegaTran 1.0 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Origene). siRNA transfections were performed using Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen).

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting assays

HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were harvested and lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer composed of 50 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.4, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 μg/ml pepstatin. For immunoprecipitation of histones, soluble supernatants were removed, after which the sediment was collected and sonicated to release chromatin-associated proteins for further analyses. The lysates were precleared and incubated with antibody-coated beads. The precipitated proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Pall Corporation), and detected using the Odyssey Imaging System (LI-CDR).

Mononucleosome purification

Mononucleosome purification was performed following previously described procedures (46) with the following modifications. HEK293T cells expressing FLAG–H2A were lysed sequentially in hypotonic buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 0.3% Nonidet P-40, proteinase inhibitors) and nuclear extraction buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 0.3% Nonidet P-40, 420 mm NaCl, proteinase inhibitors). The nuclear pellets were washed with MNase digestion buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2) and digested with MNase for 30 min at 37 °C. Following sonication, nuclear lysates were centrifuged, after which the resulting supernatants were incubated with 30 μl of anti-FLAG M2 beads for 4 h at 4 °C. Next, the beads were washed three times with washing buffer (10 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm KCl, 10% glycerol, proteinase inhibitors). Mononucleosomes were eluted for 2 h at 4 °C with 400 μg/ml FLAG peptide.

His-ubiquitin pulldown assay

The cells were transfected with a His-ubiquitin plasmid for 48 h and then harvested and lysed with 6 ml of cell lysis buffer (6 m guanidinium chloride, 0.1 m Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0), followed by incubation at room temperature for 30 min. Ni2+–nitrilotriacetate–agarose beads (75 μl) were added and incubated for another 4 h. The beads were collected by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 5 min and then sequentially washed with buffer A (8 m urea, 0.1 m Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, and 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0), buffer B (8 m urea, 0.1 m Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, and 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.3), and buffer C (8 m urea, 0.1 m Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, and 10 mm Tris-HCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 8.0). Finally, the modified proteins were eluted with 50 μl of elution buffer containing 0.2 m imidazole, 5% SDS, 0.15 m Tris-HCl, and 10% glycerol at pH 6.7. The enriched protein samples combined with an equal volume of 2× SDS loading buffer were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

The subcellular localization of proteins was examined by immunofluorescence microscopy according to our previous protocol (47) and observed using an LSM 710 NLO and DuoScan (CarlZeiss, Germany).

Subcellular fractionation

Subcellular fractionation was performed according to previously described procedures (48). First, 1 × 107 HeLa cells were harvested and washed using ice-cold PBS at 4 °C. Then 5% of the cells were used for the whole-cell lysate fraction, and the rest of the cells were resuspended in hypotonic buffer (10 mm HEPES, 10 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, and 0.5 mm DTT, pH 7.4) with a protease inhibitor mixture for 8 min on ice. The swollen cells were transferred to a precooled Dounce homogenizer, homogenized 15 times on ice, centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, and resuspended with 250 μl of cytoplasmic extract buffer (0.3 m HEPES, 1.4 m KCl, 0.03 m MgCl2, and 0.5 mm DTT, pH 7.9). The supernatant was collected as the cytosolic fraction, and the pellet was sonicated for 10 s for 10 repetitions using microprobes and dissociated in 200 μl of dialysis buffer (20 mm HEPES, 20% glycerol, 100 mm KCl, 0.2 mm EDTA, and 0.5 mm DTT, pH 7.9) and then centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed and used as the nucleoplasm fraction, and the pellet was collected as the nucleoli fraction. All of the fractions above were separated using SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies.

Chromatin extraction assay

Chromatin extraction was performed as previously described (49). The cells were lysed in 100 μl of chromatin extraction buffer A (10 mm PIPES, 300 mm sucrose, 100 mm NaCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EGTA, 0.2% Triton X-100, pH 6.8) on ice. After 30 min, the mixture was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 5 min, and the cell pellets were harvested with 100 μl of buffer B (3 mm EDTA, 0.2 mm EGTA, 1 mm DTT). After 30 min, the mixture was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 5 min, and the sediment was resuspended in 50 μl buffer C (50 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.0).

Protein purification and in vitro pulldown

Recombinant GST-fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 cells and purified using GSH-Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare). His-tagged proteins were also expressed in E. coli BL21 cells and purified using a Ni2+–Sepharose affinity column (GE Healthcare). In vitro pulldown assays were performed as described previously (49).

Laser microirradiation and immunofluorescence assays

To detect whether RPL6 was recruited to DNA damage sites, U2OS cells were seeded onto thin glass-bottomed plates and then transfected with GFP-RPL6. After 24 h, the cells were treated with KU55933 (10 μm), NU7441 (2 μm), VE821 (5 μm), or olaparib (10 μm). Laser microirradiation was carried out using an Andor Micropoint system (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK) with an UV laser (16-Hz pulse, 41% laser output). Images were acquired using a Nikon A1 confocal imaging system every 20 s. For laser microirradiation and immunofluorescence assays, U2OS cells were seeded onto thin glass-bottomed plates and then transfected twice with the RPL6 siRNA, after which laser microirradiation was performed. The cells were then washed with PBS and fixed in precooled methanol for 8 min at −20 °C. Immunofluorescence assays were performed following the procedure described above. Quantitation of the intensity within the microirradiated nuclear strip and nonmicroirradiated strip of the same length was performed, and the relative ratio of the intensities was calculated. At least 20 independent cells were counted at different time points.

NHEJ and HR analyses

The cells were first transfected with scrambled siRNA or RPL6 siRNA followed by NHEJ or HR reporters, after which the analyses were carried out following the procedures described previously (49).

FACS analysis

The FACS analysis was performed as previously described (37, 50). Briefly, the cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA and RPL6 siRNA. After 48 h, the cells were treated with 40 μm etoposide for the indicated time periods. Next, the treated cells were collected, washed with PBS, and fixed with 70% ethanol. After fixation, the cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 0.25% Triton X-100 on ice for 15 min. The cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 1% BSA containing 1 μl of phosphohistone H3 (Ser10) antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Next, the cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in PBS containing 100 μg/ml propidium iodide and 100 μg/ml RNase A, after which they were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. FACS analysis was performed using a FACSVerse cytometer.

Clonogenic survival assay

HeLa cells were seeded in 6-well plates (150–1500 cells/well) in triplicate. After 24 h, the cells were cultured in medium containing different concentrations of etoposide for 1 h, washed twice with PBS, and then cultured for 12 days, with the medium refreshed every 2 days. For staining, the cells were rinsed using PBS, fixed in methanol at −20 °C for 10 min, and stained with crystal violet (0.1% w/v) for 20 min. The clone numbers were counted. The survival fraction was normalized to the number of untreated cells.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis in this research was performed using Student's t test (two-tailed) and two-way analysis of variance. All of the results are presented as the means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Author contributions

C. Y., W. Z., T. L., and X. Z. conceptualization; C. Y. and W. Z. data curation; C. Y., W. Z., Y.J., T. L., Y. Y., and X. Z. formal analysis; C. Y., W. Z., Y.J., T. L., and Y. Y. investigation; C. Y., W. Z., Y.J., T. L., and X. Z. writing-original draft; C. Y., W. Z., and X. Z. writing-review and editing; X. Z. supervision; X. Z. funding acquisition; X. Z. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Dr. Zhenkun Lou for providing the plasmids of MDC1. We are thankful for the helpful discussion from Junhong Guan and Dongmei Bai and the technical help from Liwen Zhang from Peking University. We also appreciate the assistance of Xiaochen Li, Guopeng Wang, Liying Du, and Hongxia Lv from the Core Facilities of Life Sciences at Peking University for assistance with microscopic imaging and cell flow cytometry.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation of China Grants 81730080, 31670786, and 31470754 and the National Key Research and Development Program of China Grant 2016YFC1302401. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S3.

- DSB

- double-stranded break

- DDR

- DNA damage response

- PARP

- poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- MDC1

- mediator of DNA damage checkpoint 1

- γH2AX

- H2A histone family member X

- NHEJ

- nonhomologous end joining

- HR

- homologous recombination

- IP

- immunoprecipitation.

References

- 1. Nomura M., Gourse R., and Baughman G. (1984) Regulation of the synthesis of ribosomes and ribosomal components. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 53, 75–117 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.000451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Naganuma T., Nomura N., Yao M., Mochizuki M., Uchiumi T., and Tanaka I. (2010) Structural basis for translation factor recruitment to the eukaryotic/archaeal ribosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4747–4756 10.1074/jbc.M109.068098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rodnina M. V., and Wintermeyer W. (2009) Recent mechanistic insights into eukaryotic ribosomes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 435–443 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tschochner H., and Hurt E. (2003) Pre-ribosomes on the road from the nucleolus to the cytoplasm. Trends Cell Biol. 13, 255–263 10.1016/S0962-8924(03)00054-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nerurkar P., Altvater M., Gerhardy S., Schütz S., Fischer U., Weirich C., and Panse V. G. (2015) Eukaryotic ribosome assembly and nuclear export. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 319, 107–140 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim H., Abeysirigunawarden S. C., Chen K., Mayerle M., Ragunathan K., Luthey-Schulten Z., Ha T., and Woodson S. A. (2014) Protein-guided RNA dynamics during early ribosome assembly. Nature 506, 334–338 10.1038/nature13039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pan W., Issaq S., and Zhang Y. (2011) The in vivo role of the RP-Mdm2-p53 pathway in signaling oncogenic stress induced by pRb inactivation and Ras overexpression. PLoS One 6, e21625 10.1371/journal.pone.0021625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deisenroth C., and Zhang Y. (2010) Ribosome biogenesis surveillance: probing the ribosomal protein–Mdm2–p53 pathway. Oncogene 29, 4253–4260 10.1038/onc.2010.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nicolas E., Parisot P., Pinto-Monteiro C., de Walque R., De Vleeschouwer C., and Lafontaine D. L. (2016) Involvement of human ribosomal proteins in nucleolar structure and p53-dependent nucleolar stress. Nat. Commun. 7, 11390 10.1038/ncomms11390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xiong X., Zhao Y., He H., and Sun Y. (2011) Ribosomal protein S27-like and S27 interplay with p53-MDM2 axis as a target, a substrate and a regulator. Oncogene 30, 1798–1811 10.1038/onc.2010.569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yadavilli S., Mayo L. D., Higgins M., Lain S., Hegde V., and Deutsch W. A. (2009) Ribosomal protein S3: a multi-functional protein that interacts with both p53 and MDM2 through its KH domain. DNA Repair 8, 1215–1224 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen D., Zhang Z., Li M., Wang W., Li Y., Rayburn E. R., Hill D. L., Wang H., and Zhang R. (2007) Ribosomal protein S7 as a novel modulator of p53-MDM2 interaction: binding to MDM2, stabilization of p53 protein, and activation of p53 function. Oncogene 26, 5029–5037 10.1038/sj.onc.1210327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bhat K. P., Itahana K., Jin A., and Zhang Y. (2004) Essential role of ribosomal protein L11 in mediating growth inhibition-induced p53 activation. EMBO J. 23, 2402–2412 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang J., Bai D., Ma X., Guan J., and Zheng X. (2014) hCINAP is a novel regulator of ribosomal protein-HDM2-p53 pathway by controlling NEDDylation of ribosomal protein S14. Oncogene 33, 246–254 10.1038/onc.2012.560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bai D., Zhang J., Xiao W., and Zheng X. (2014) Regulation of the HDM2-p53 pathway by ribosomal protein L6 in response to ribosomal stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 1799–1811 10.1093/nar/gkt971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cui D., Li L., Lou H., Sun H., Ngai S. M., Shao G., and Tang J. (2014) The ribosomal protein S26 regulates p53 activity in response to DNA damage. Oncogene 33, 2225–2235 10.1038/onc.2013.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miliani de Marval P. L., and Zhang Y. (2011) The RP-Mdm2-p53 pathway and tumorigenesis. Oncotarget 2, 234–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stepiński D. (2016) Nucleolus-derived mediators in oncogenic stress response and activation of p53-dependent pathways. Histochem. Cell Biol. 146, 119–139 10.1007/s00418-016-1443-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giglia-Mari G., Zotter A., and Vermeulen W. (2011) DNA damage response. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a000745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ciccia A., and Elledge S. J. (2010) The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell 40, 179–204 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berkovich E., Monnat R. J. Jr., and Kastan M. B. (2007) Roles of ATM and NBS1 in chromatin structure modulation and DNA double-strand break repair. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 683–690 10.1038/ncb1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Falck J., Coates J., and Jackson S. P. (2005) Conserved modes of recruitment of ATM, ATR and DNA-PKcs to sites of DNA damage. Nature 434, 605–611 10.1038/nature03442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Doil C., Mailand N., Bekker-Jensen S., Menard P., Larsen D. H., Pepperkok R., Ellenberg J., Panier S., Durocher D., Bartek J., Lukas J., and Lukas C. (2009) RNF168 binds and amplifies ubiquitin conjugates on damaged chromosomes to allow accumulation of repair proteins. Cell 136, 435–446 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mailand N., Bekker-Jensen S., Faustrup H., Melander F., Bartek J., Lukas C., and Lukas J. (2007) RNF8 ubiquitylates histones at DNA double-strand breaks and promotes assembly of repair proteins. Cell 131, 887–900 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huen M. S., Grant R., Manke I., Minn K., Yu X., Yaffe M. B., and Chen J. (2007) RNF8 transduces the DNA-damage signal via histone ubiquitylation and checkpoint protein assembly. Cell 131, 901–914 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mattiroli F., Vissers J. H., van Dijk W. J., Ikpa P., Citterio E., Vermeulen W., Marteijn J. A., and Sixma T. K. (2012) RNF168 ubiquitinates K13–15 on H2A/H2AX to drive DNA damage signaling. Cell 150, 1182–1195 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fradet-Turcotte A., Canny M. D., Escribano-Díaz C., Orthwein A., Leung C. C., Huang H., Landry M. C., Kitevski-LeBlanc J., Noordermeer S. M., Sicheri F., and Durocher D. (2013) 53BP1 is a reader of the DNA-damage-induced H2A Lys 15 ubiquitin mark. Nature 499, 50–54 10.1038/nature12318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang B., and Elledge S. J. (2007) Ubc13/Rnf8 ubiquitin ligases control foci formation of the Rap80/Abraxas/Brca1/Brcc36 complex in response to DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 20759–20763 10.1073/pnas.0710061104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Finn K., Lowndes N. F., and Grenon M. (2012) Eukaryotic DNA damage checkpoint activation in response to double-strand breaks. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 69, 1447–1473 10.1007/s00018-011-0875-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. DiTullio R. A. Jr., Mochan T. A., Venere M., Bartkova J., Sehested M., Bartek J., and Halazonetis T. D. (2002) 53BP1 functions in an ATM-dependent checkpoint pathway that is constitutively activated in human cancer. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 998–1002 10.1038/ncb892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shibata A., Barton O., Noon A. T., Dahm K., Deckbar D., Goodarzi A. A., Löbrich M., and Jeggo P. A. (2010) Role of ATM and the damage response mediator proteins 53BP1 and MDC1 in the maintenance of G2/M checkpoint arrest. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 3371–3383 10.1128/MCB.01644-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boulon S., Westman B. J., Hutten S., Boisvert F. M., and Lamond A. I. (2010) The nucleolus under stress. Mol. Cell 40, 216–227 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chapman J. R., and Jackson S. P. (2008) Phospho-dependent interactions between NBS1 and MDC1 mediate chromatin retention of the MRN complex at sites of DNA damage. EMBO Rep. 9, 795–801 10.1038/embor.2008.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bohgaki T., Bohgaki M., and Hakem R. (2010) DNA double-strand break signaling and human disorders. Genome Integr. 1, 15 10.1186/2041-9414-1-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chapman J. R., Barral P., Vannier J. B., Borel V., Steger M., Tomas-Loba A., Sartori A. A., Adams I. R., Batista F. D., and Boulton S. J. (2013) RIF1 is essential for 53BP1-dependent nonhomologous end joining and suppression of DNA double-strand break resection. Mol. Cell 49, 858–871 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fernandez-Capetillo O., Chen H. T., Celeste A., Ward I., Romanienko P. J., Morales J. C., Naka K., Xia Z., Camerini-Otero R. D., Motoyama N., Carpenter P. B., Bonner W. M., Chen J., and Nussenzweig A. (2002) DNA damage–induced G2–M checkpoint activation by histone H2AX and 53BP1. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 993–997 10.1038/ncb884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang B., Matsuoka S., Carpenter P. B., and Elledge S. J. (2002) 53BP1, a mediator of the DNA damage checkpoint. Science 298, 1435–1438 10.1126/science.1076182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee J. H., Park S. J., Hariharasudhan G., Kim M. J., Jung S. M., Jeong S. Y., Chang I. Y., Kim C., Kim E., Yu J., Bae S., and You H. J. (2017) ID3 regulates the MDC1-mediated DNA damage response in order to maintain genome stability. Nat. Commun. 8, 903 10.1038/s41467-017-01051-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Deleted in proof.

- 40. Deleted in proof.

- 41. Dai M. S., and Lu H. (2004) Inhibition of MDM2-mediated p53 ubiquitination and degradation by ribosomal protein L5. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 44475–44482 10.1074/jbc.M403722200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang Y., and Lu H. (2009) Signaling to p53: ribosomal proteins find their way. Cancer Cell 16, 369–377 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schreiber V., Dantzer F., Ame J. C., and de Murcia G. (2006) Poly(ADP-ribose): novel functions for an old molecule. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 517–528 10.1038/nrm1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Messner S., and Hottiger M. O. (2011) Histone ADP-ribosylation in DNA repair, replication and transcription. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 534–542 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nowsheen S., Aziz K., Aziz A., Deng M., Qin B., Luo K., Jeganathan K. B., Zhang H., Liu T., Yu J., Deng Y., Yuan J., Ding W., van Deursen J. M., and Lou Z. (2018) L3MBTL2 orchestrates ubiquitin signalling by dictating the sequential recruitment of RNF8 and RNF168 after DNA damage. Nat. Cell Biol. 20, 455–464 10.1038/s41556-018-0071-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhu P., Zhou W., Wang J., Puc J., Ohgi K. A., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Glass C. K., and Rosenfeld M. G. (2007) A histone H2A deubiquitinase complex coordinating histone acetylation and H1 dissociation in transcriptional regulation. Mol. Cell 27, 609–621 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li T., Guan J., Huang Z., Hu X., and Zheng X. (2014) RNF168-mediated H2A neddylation antagonizes ubiquitylation of H2A and regulates DNA damage repair. J. Cell Sci. 127, 2238–2248 10.1242/jcs.138891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bailly A., Perrin A., Bou Malhab L. J., Pion E., Larance M., Nagala M., Smith P., O'Donohue M. F., Gleizes P. E., Zomerdijk J., Lamond A. I., and Xirodimas D. P. (2016) The NEDD8 inhibitor MLN4924 increases the size of the nucleolus and activates p53 through the ribosomal-Mdm2 pathway. Oncogene 35, 415–426 10.1038/onc.2015.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang C., Zang W., Tang Z., Ji Y., Xu R., Yang Y., Luo A., Hu B., Zhang Z., Liu Z., and Zheng X. (2018) A20/TNFAIP3 regulates the DNA damage response and mediates tumor cell resistance to DNA-damaging therapy. Cancer Res. 78, 1069–1082 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2018-1069,10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ward I. M., Minn K., van Deursen J., and Chen J. (2003) p53 Binding protein 53BP1 is required for DNA damage responses and tumor suppression in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 2556–2563 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2556-2563.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.