ABSTRACT

Objectives

To describe patterns of multimorbidity in six diverse Latin American and Caribbean countries, examine its effects on primary care experiences, and assess its influence on reported overall health care assessments.

Methods

Cross-sectional data are from the Inter-American Development Bank's international primary care survey, conducted in 2013/2014, and represent the adult populations of Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, Jamaica, Mexico and Panama. Robust Poisson regression models were used to estimate the extent to which those with multimorbidity receive adequate and appropriate primary care, have confidence in managing their health condition, and are able to afford needed medical care.

Results

The prevalence of multimorbidity ranged from 17.5% in Colombia to 37.3% in Jamaica. Most of the examined conditions occur along with others, with diabetes and heart disease being the two problems most associated with other conditions. The proportions of adults with high out-of-pocket payments, problems paying their medical bills, seeing multiple doctors, and being in only fair/poor health were higher among those with greater levels of multimorbidity and poorer primary care experiences. Multimorbidity and difficulties with primary care were positively associated with trouble paying for medical care and managing one's conditions. Nonetheless, adults with multimorbidity were more likely to have received lifestyle advice and to be up to date with preventive exams.

Conclusions

Multimorbidity is reported frequently. Providing adequate care for the growing number of such patients is a major challenge facing most health systems, which will require considerable strengthening of primary care along with financial protection for those most in need.

Keywords: Morbidity, Primary Health Care, Health systems, Latin America, Caribbean Region

RESUMEN

Objetivos

Describir los modelos de multimorbilidad en seis países distintos de América Latina y el Caribe, examinar sus efectos en las experiencias de atención primaria y evaluar su influencia con base en informes sobre evaluaciones generales de atención de salud.

Métodos

Los datos transversales son de la encuesta internacional de atención primaria del Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, realizada en el 2013-2014, y representan la población adulta de Brasil, Colombia, El Salvador, Jamaica, México y Panamá. Se utilizaron modelos robustos de regresión de Poisson en personas con multimorbilidad para estimar hasta qué punto reciben la atención primaria suficiente y apropiada, tienen confianza en que pueden controlar su estado de salud, y pueden costear la atención médica necesaria.

Resultados

Se observó que la prevalencia de la multimorbilidad abarcaba desde 17,5% en Colombia hasta 37,3% en Jamaica. La mayoría de las afecciones examinadas se presentan acompañadas de otras, siendo la diabetes y las cardiopatías los dos problemas más asociados con otras afecciones. La proporción de adultos que afrontan pagos directos altos, problemas para pagar sus cuentas médicas, consultas con múltiples médicos y un estado de salud entre aceptable y desmejorado fue mayor en aquellos con niveles de multimorbilidad más altos y experiencias de atención primaria más deficientes. La multimorbilidad y las dificultades concernientes a la atención primaria presentaron una asociación positiva con la dificultad para costear la atención médica y controlar su estado de salud. No obstante, los adultos con multimorbilidad tenían mayores probabilidades de haber recibido asesoramiento sobre su estilo de vida y de estar al día con sus exámenes preventivos.

Conclusiones

La multimorbilidad se notifica con frecuencia. Ofrecer un cuidado adecuado para el número cada vez mayor de pacientes con esas características es un reto importante al que se enfrenta la mayoría de los sistemas de salud, que necesitarán un fortalecimiento considerable de la atención primaria y de la protección financiera para atender a aquellos más necesitados.

Palabras clave: Morbilidad; atención primaria de salud; sistemas de salud; América Latina, Región del Caribe

RESUMO

Objetivos

Descrever os padrões de multimorbidade em seis países da América Latina e Caribe, examinar os efeitos da multimorbidade na prática de atenção primária e avaliar a influência nas avaliações relatadas pelos pacientes atendidos.

Métodos

Estudo baseado em dados transversais obtidos de uma pesquisa internacional de atenção primária realizada pelo Banco Interamericano de Desenvolvimento (BID) em 2013–2014, representativos da população adulta do Brasil, Colômbia, El Salvador, Jamaica, México e Panamá. Modelos robustos de regressão de Poisson foram usados para estimar em que medida a atenção primária prestada aos pacientes com multimorbidade é adequada e oportuna, eles se sentem seguros em controlar a própria doença e podem pagar pela atenção médica necessária.

Resultados

A prevalência de multimorbidade variou entre 17,5% na Colômbia e 37,3% na Jamaica. A maioria das doenças avaliadas ocorre junto com outros problemas, sendo a diabetes e a doença cardíaca mais comumente associadas a outras doenças. Os percentuais de adultos que relataram grandes desembolsos por conta própria, dificuldade para pagar as contas médicas, consultas a vários médicos distintos e estado de saúde regular/ruim foram maiores nos pacientes com maior número de doenças e experiências de atendimento piores na atenção primária. A multimorbidade e problemas com a atenção primária tiveram uma associação positiva com a dificuldade de pagar pela atenção médica e controlar a própria doença. Porém, verificou-se uma probabilidade maior de os adultos com multimorbidade receberem orientações sobre estilo de vida e manter em dia os exames preventivos.

Conclusões

A multimorbidade é frequente. Proporcionar atenção adequada ao número crescente de pacientes portadores de diversas doenças é um grande desafio enfrentado pela maioria dos sistemas de saúde e requer um reforço substancial da atenção primária e proteção financeira para os mais carentes.

Palavras-chave: Morbidade; atenção primária à saúde; sistemas de saúde; América Latina, Região do Caribe

The Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region is experiencing rapid demographic and epidemiologic changes (1). Among these, longevity has improved considerably while noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) have become the leading causes of mortality and disability, now accounting for 68 percent of deaths and 60 percent of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)—a toll that is even more pronounced in poor communities (2,3). The direct and indirect costs incurred from NCDs in the LAC region are estimated to have reached hundreds of billions of dollars and are likely to increase (4).

One of the effects of increasing longevity and corresponding changes in epidemiological profiles is an increase in the prevalence of multimorbidity (defined as the presence of two or more chronic conditions, or morbidities, in the same individual). Multimorbidity increases with age and is more common among women and individuals of lower socioeconomic status (5). Multimorbidity is associated with greater disability and mortality, worse quality of life and more frequent use of health care services (6, 7). Individuals with multimorbidity are more likely to report treatment burdens due to poor coordination between providers, which in turn imply greater financial costs, lower adherence to medication regimens, and difficulty initiating and maintaining lifestyle changes (8). Providing treatment for individuals with multimorbidity requires health systems to shift their current focus to foster a patient-centered approach that will reduce adverse consequences, overtreatment and higher medical costs to a minimum (9). Achieving such a realignment can be a challenge given that most health systems are structured to provide treatment on a disease-by-disease basis (10).

A number of different strategies have been proposed to prevent and control non communicable chronic diseases, most of which include elements that range from primary to quaternary prevention (11). In addition to strong public policies to reduce exposure to risk factors such as tobacco, alcohol, and poor dietary intake, national NCD prevention and control strategies are increasingly incorporating health system interventions (12). Strengthening the role of primary care (PC) by expanding its multidisciplinary scope and enhancing coordination with other levels of the health system has become one of the most salient approaches, especially in light of the 40th anniversary of the Alma Ata declaration on Primary Health Care (13).

Nonetheless, few cross-country studies to date illustrate the relationship between a country's primary care approach and its impact on helping individuals manage chronic conditions, especially when they are afflicted by more than one (2).

In 2013, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) financed the collection of nationally representative data on chronic disease prevalence and patient-reported measures of their PC primary care experiences in each subregion of the Americas, to wit, South America (Brazil, Colombia), Central America (El Salvador, Panama), the Caribbean (Jamaica), and North America (Mexico) (14). Together, these countries make up nearly three-quarters of the estimated LAC population of 525 million.

The purpose of this study is to describe patterns of multimorbidity in the six countries surveyed, characterize patterns of association between multimorbidity and primary care experiences, and assess the extent to which respondents with multimorbidity feel they receive adequate and appropriate primary care, have confidence in managing their health condition, and are able to afford needed medical care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study analyzes cross-sectional data collected as part of the IDB's international primary care survey conducted in 2013/14. In each country, a national sample of the adult (18 years and older), non-institutionalized population was selected from a nationwide list of households and interviewed by telephone. Both cell phones and landlines were included, making it possible to obtain representative samples from rural as well as urban populations, for a total of about 1,500 interviews per country. The survey instrument was an adapted version of the questionnaire that the Commonwealth Fund has used to survey several high income countries (OECD) since 1998 (15). The questionnaire was translated, adapted, pre-tested, and adjusted to improve comprehension (14). The Random Iterative Method (RIM) was used to generate survey weights that balance the age, sex, socioeconomic status, education and household size distributions based on recent census data in each country (16). RIM helps to reduce potential selection biases, resulting from non-coverage or non-response. Further details can be found in previous publications (14, 17-19).

Study variables

Chronic conditions were enumerated by self-report. Respondents were asked whether a health professional had ever told them they had one or more of the following conditions or risk factors: arthritis, asthma, cancer (any type), depression, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, and/or high cholesterol. These are among the most common risk factors and chronic conditions in LAC (20). We created an index that represents a count of the number of chronic conditions each person reported and created a categorical variable reflecting that index, with no conditions (0, reference), 1 chronic condition, 2 chronic conditions, and 3 or more chronic conditions.

People's primary care experiences were assessed using 15 self-reported items in accordance with previously validated methods (21). The items represent attributes of effective PC (accessibility/absence of barriers to receiving care; longitudinal/continuous care; coordination of care; and primary care provider communication, interpersonal relations, and cultural competence) (22, 23). The list of categorical responses (always, almost always, rarely, never) was then coded as a binary variable to represent negative experiences or problems (rarely/never categorized as 1 vs. always/almost always coded as 0).

Data analysis

We evaluated the association between a respondent's PC problems and degree of chronic disease comorbidity with a set of outcomes important to chronic care management: high out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses (since expenditures are reported in local currency, this measure was operationalized as whether the individual reported spending more than the country median for OOP payments during the past year), reported difficulty paying medical bills, seeing three or more different physicians in the past year, received healthy lifestyle advice (a health professional provided advice on diet, physical activity, and avoiding tobacco), had kept basic preventive exams up to date (blood pressure checked in the past year and cholesterol checked in the past 5 years), had confidence they could manage their chronic condition, and self-rated their health status (dichotomized as fair/poor health versus excellent, very good and good) as an overall measure of well-being (24). Multivariable analyses report Incidence-Rate Ratios (IRRs) from robust Poisson regression because the outcomes analyzed are binary but their prevalence is relatively high (generally over 10%), and alternatives such as logistic regression would likely overestimate the magnitude of associations between variables (25). All models additionally control for sex, age categories, educational attainment, and private health insurance (in most cases, supplementary to public coverage). Country fixed effects (with Mexico as the reference category) control for unmeasured time-invariant country characteristics (26). All results take into account the sample design and include final sample weights.

Ethics approval

The study received human subjects and ethics council approval from research review boards in each participating site, and from the IDB (14). Informed consent was obtained from each respondent before a telephone interview. All personally identifying information was removed from survey data prior to analysis. The complete de-identified dataset is publicly available from the IDB: https://publications.iadb.org/handle/11319/9095.

RESULTS

Self-reported multimorbidity (defined as having 2 or more chronic conditions) ranged from 12.4% in Colombia to 25.1% in Jamaica, whereas the prevalence reported by respondents in Mexico (14.4%), El Salvador (15.5%), Brazil (16.8%), and Panama (18.3%) was intermediate (data available upon request). The mean age among all respondents was 40.3 years (SD 0.2) but rose as the number of comorbid conditions increased (Table 1). Although women made up about half of the total sample, female respondents comprised higher proportions of the total who listed a greater number of comorbidities. Educational levels were relatively low overall, with 40% of the sample having attained a secondary education or less. People with less education had more comorbid conditions. A large share of the respondents (43.9%) had high OOP and 18.5% had trouble paying their medical bills. About a third of those surveyed had seen three or more physicians in the previous year. The proportions of adults with high OOP, problems paying their medical bills, and seeing multiple doctors rose as the number of concurrent chronic conditions increased. About a third of all respondents had received healthy behavior advice and 36% were up-to-date with preventive exams, but the proportion was higher among those with more multimorbidity. Among those with at least one condition, the majority (84.6%) reported having confidence in being able to manage their conditions, but confidence was stated more frequently by those who had fewer medical conditions. Higher degrees of multimorbidity were associated with larger proportions of individuals reporting a health status that was only fair/poor. Among those with three or more conditions, 51.6% reported having fair/poor health compared to 39.49% among those with two conditions.

TABLE 1. Descriptive statistics of adults in selected Latin American and Caribbean countries surveyed in 2013/2014, categories by number of chronic disease conditions.

| Total sample | 0 conditions | 1 condition | 2 conditions | 3 or more | p-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 40.3 | 35.8 | 43.7 | 50.1 | 56.4 | <0.001 |

| (SD) | (0.2) | (0.2) | (0.5) | (0.7) | (0.9) | |

| Female | 52.0 | 47.2 | 56.0 | 64.4 | 65.2 | <0.001 |

| [95% CI] | [50.6,53.3] | [45.6,48.8] | [52.9,58.9] | [60.1,68.5] | [60.1,69.9] | |

| Less than high school | 39.9 | 36.3 | 40.8 | 51.0 | 53.5 | <0.001 |

| [38.6,41.3] | [34.7,38.0] | [37.8,43.9] | [46.5,55.4] | [48.5,58.4] | ||

| High school completed | 40.3 | 43.1 | 38.7 | 32.8 | 30.6 | |

| [39.0,41.6] | [41.53,44.71] | [35.8,41.6] | [29.0,36.9] | [26.4,35.1] | ||

| Some college or more | 19.8 | 20.6 | 20.5 | 16.3 | 16.0 | |

| [18.9,20.7] | [19.4,21.8] | [18.5,22.7] | [13.7,19.2] | [13.0,19.5] | ||

| Private health insurance | 18.0 | 17.5 | 18.4 | 18.6 | 21.0 | >0.05 |

| [17.1,19.0] | [16.3,18.7] | [16.4,20.6] | [15.5,22.2] | [17.3,25.3] | ||

| High out-of-pocket expenses | 43.9 | 39.6 | 50.5 | 50.7 | 55.4 | <0.001 |

| [42.4,45.4] | [37.8,41.4] | [47.0,54.0] | [45.5,55.9] | [49.3,61.3] | ||

| Problems paying medical bills | 18.5 | 14.2 | 23.5 | 27.6 | 29.2 | <0.001 |

| [17.4,19.6] | [13.0,15.5] | [20.9,26.2] | [23.7,31.9] | [24.8,34.0] | ||

| Consulted 3 or more different physicians, past year | 31.2 | 25.3 | 39.2 | 42.0 | 46.5 | <0.001 |

| [30.0,32.4] | [23.9,26.7] | [36.2,42.2] | [37.5,46.5] | [41.4,51.8] | ||

| Healthy behavior advice received | 31.6 | 26.8 | 35.5 | 43.5 | 46.5 | <0.001 |

| [30.4,32.9] | [25.4,28.3] | [32.7,38.4] | [39.1,48.0] | [41.5,51.5] | ||

| Preventive exams up to date | 36.2 | 26.0 | 45.5 | 59.6 | 66.8 | <0.001 |

| [34.9,37.4] | [24.6,27.4] | [42.6,48.5] | [55.1,64.0] | [61.7,71.4] | ||

| Confidence can manage condition | 84.6 | – | 88.5 | 81.9 | 79.8 | <0.001 |

| [82.7,86.3] | – | [86.0,90.5] | [77.9,85.3] | [75.4,83.7] | ||

| Fair/poor health status | 19.1 | 10.4 | 25.0 | 39.5 | 51.6 | <0.001 |

| [18.0,20.3] | [9.4,11.4] | [22.3,27.9] | [35.1,44.1] | [46.6,56.7] |

Source: Weighted means, percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated by the authors based on individual-level data.

From design-corrected F-test comparing outcomes by chronic disease category. P values >0.05 were considered to be not statistically significant.

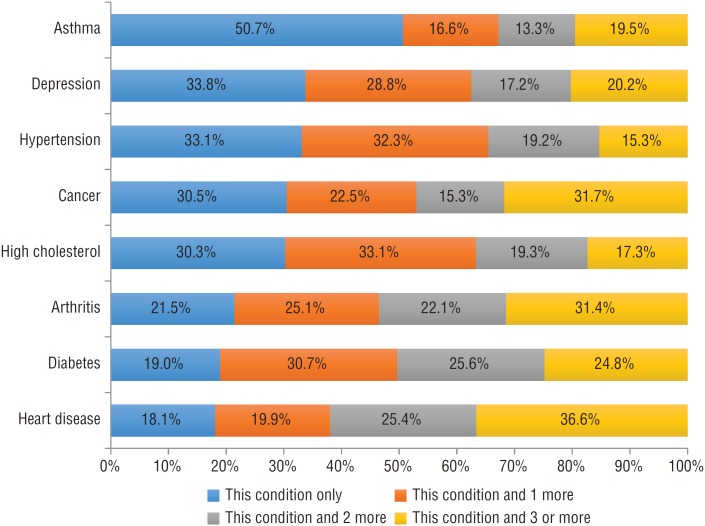

Different health conditions follow different patterns of multimorbidity (Figure 1). Over half of the individuals who reported having asthma reported having this condition alone. For all other conditions studied, multimorbidity was common. Among interviewees reporting depression, hypertension, cancer or high cholesterol, around 30% had only these conditions. The proportions citing only arthritis, diabetes or heart disease were even smaller (some 20%). For those reporting cancer, arthritis or heart disease, over 30% had an additional three or more conditions.

FIGURE 1. Comorbidity patterns for eight chronic conditions among adults in selected Latin American and Caribbean countries surveyed in 2013/2014.

Source: Weighted proportions calculated by the authors based on individual-level data.

Results displayed in Table 2 show that higher numbers of concurrent health conditions are associated with greater difficulty accessing health care, such as scheduling an exam, and challenges related to continuity of care, such a usual source of care. Differences were less marked for indicators of patient centeredness. Respondents with greater degrees of multimorbidity more commonly reported long waits for a diagnosis, but those with fewer health conditions reported more difficulties related to care coordination by their usual source of care. In general, those with no health conditions had fewer PC problems than those with any conditions.

TABLE 2. Primary care experiences of adults in six Latin American and Caribbean countries surveyed in 2013/2014, by number of chronic conditions.

| Total | 0 conditions | 1 condition | 2 conditions | 3 or more | P-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | ||||||

| Did not get exam due to scheduling | 19.9 | 15.3 | 24.8 | 29.0 | 33.0 | <0.001 |

| [18.8,21.0] | [14.2,16.5] | [22.3,27.5] | [25.2,33.3] | [28.3,38.0] | ||

| No doctor visit due to transport | 10.3 | 8.6 | 13.0 | 12.8 | 14.3 | <0.001 |

| [9.4,11.2] | [7.7,9.6] | [11.1,15.1] | [10.1,16.2] | [11.0,18.3] | ||

| Difficult to get care on weekends | 74.9 | 75.3 | 75.3 | 74.3 | 70.4 | >0.05 |

| [73.0,76.0] | [73.9,76.7] | [72.6,77.8] | [70.2,78.1] | [65.5,74.9] | ||

| 5+ days wait for doctor appointment | 33.6 | 32.4 | 33.8 | 37.0 | 38.0 | <0.05 |

| [32.3,34.9] | [30.9,34.0] | [31.0,36.7] | [32.6,41.5] | [33.2,43.1] | ||

| Continuity of care | ||||||

| Has a usual source of care (USC) | 51.7 | 57.3 | 45.2 | 40.7 | 35.7 | <0.001 |

| [50.4,53.0] | [55.7,58.9] | [42.2,48.2] | [36.4,45.2] | [31.0,40.6] | ||

| USC knows medical history | 33.6 | 34.0 | 33.8 | 32.9 | 31.7 | >0.05 |

| [32.1,35.2] | [32.1,35.9] | [30.7,37.2] | [28.3,38.0] | [26.6,37.34] | ||

| Patient centeredness | ||||||

| Difficult to communicate w/ doctor | 45.0 | 44.4 | 46.2 | 46.5 | 43.5 | >0.05 |

| [43.4,46.6] | [42.4,46.5] | [42.8,49.8] | [41.3,51.7] | [37.9,49.3] | ||

| Difficult to ask doctor questions | 28.1 | 27.1 | 33.0 | 24.7 | 27.2 | <0.05 |

| [26.7,29.6] | [25.3,28.9] | [29.8,36.4] | [20.5,29.4] | [22.5,32.4] | ||

| Visit does not last enough time | 40.0 | 39.8 | 41.9 | 40.1 | 35.9 | >0.05 |

| [38.4,41.5] | [37.9,41.8] | [38.6,45.3] | [35.1,45.3] | [30.7,41.4] | ||

| Doctor does not explain things well | 26.2 | 25.3 | 30.1 | 23.8 | 24.7 | <0.05 |

| [24.8,27.6] | [23.6,27.2] | [27.0,33.4] | [19.7,28.5] | [20.0,30.1] | ||

| Coordination/problem resolution | ||||||

| Doctor does not solve your health problem(s) | 30.7 | 29.6 | 32.9 | 32.5 | 29.8 | >0.05 |

| [29.2,32.1] | [27.8,31.5] | [29.8,36.2] | [27.8,37.4] | [25.0,35.1] | ||

| Waited too long for a diagnosis | 21.4 | 15.6 | 28.7 | 34.0 | 34.6 | <0.001 |

| [20.3,22.5] | [14.4,16.8] | [25.97,31.6] | [29.85,38.4] | [29.9,39.7] | ||

| Doctor does not coordinate care | 60.5 | 60.8 | 63.5 | 61.5 | 50.2 | <0.05 |

| [58.9,62.1] | [58.8,62.8] | [60.1,66.8] | [56.1,66.6] | [44.3,56.0] | ||

| Primary care problem categories | ||||||

| 0 to 3 | 60.9 | 65.1 | 53.8 | 53.6 | 53.8 | <0.001 |

| [59.6,62.2] | [63.5,66.6] | [50.7,56.8] | [49.1,58.0] | [48.7,58.8] | ||

| 4 to 7 | 30.5 | 28.1 | 34.3 | 35.0 | 33.7 | |

| [29.2,31.7] | [26.71,29.62] | [31.5,37.2] | [30.7,39.5] | [29.1,38.6] | ||

| 8 or more | 8.7 | 6.8 | 12.0 | 11.4 | 12.5 | |

| [7.9,9.5] | [6.0,7.6] | [10.1,14.1] | [9.0,14.4] | [9.5,16.3] | ||

Source: Weighted proportions and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated by the authors based on individual-level data.

From design-corrected F-test comparing outcomes by chronic disease category. P values >0.05 were considered to be not statistically significant.

Results from regression analyses (Table 3) highlight that, compared to those with no health problems, individuals with at least one condition had more difficulties paying for their medical care (i.e. having high OOP, trouble paying medical bills) and were more likely to consult three or more physicians in the last year. For example, adults with 3 or more conditions were more likely to report having higher OOP (IRR=1.5) and problems paying for medical bills (IRR=1.8) compared to those with no conditions. Compared to those with no conditions, respondents with multimorbidity were more likely to report that their overall health was only poor/fair health: IRR=3.1, for those with 2 conditions, and IRR=4.0, for those with 3 or more. On the other hand, those with multimorbidity were more likely to answer that they received lifestyle advice (IRR=1.9, for those with 3 or more conditions) and were more likely to say they were up to date with preventive exams (IRR=2.1, for those with 3 or more conditions). However, compared to those with only one chronic condition, respondents with more were less likely to have confidence in their ability to manage their diseases.

TABLE 3. Association between number of chronic disease conditions, number of primary care problems and selected outcomes among adults surveyed in six countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2013/2014.

| High Out of pocket1 | Problems paying medical bills | Consulted 3 or more physicians, past year | Lifestyle advice received | Preventive exams up to date | Confident can manage condition2 | Poor self-rated health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic disease/condition status (“0,” or no conditions, reference group) | |||||||

| 1 condition | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.6 | – | 2.1 |

| [1.2,1.4] P<0.001 | [1.3,1.7] P<0.001 | [1.3,1.6] P<0.001 | [1.2,1.5] P<0.001 | [1.4,1.7] P<0.001 | – | [1.8,2.5] P<0.001 | |

| 2 conditions | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 3.1 |

| [1.2,1.5] P<0.001 | [1.5,2.1] P<0.001 | [1.5,1.9] P<0.001 | [1.5,1.9] P<0.001 | [1.8,2.1] P<0.001 | [0.9,1.0] P<0.01 | [2.7,3.7] P<0.001 | |

| 3+ conditions | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 4.0 |

| [1.3,1.7] P<0.001 | [1.5,2.2] P<0.001 | [1.6,2.1] P<0.001 | [1.6,2.1] P<0.001 | [1.9,2.3] P<0.001 | [0.9,1.0] P<0.01 | [3.4,4.8] P<0.001 | |

| Number of primary care problems (0-3 problems as reference) | |||||||

| 4-7 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.5 |

| [1.1,1.22] P<0.001 | [1.5,1.9] P<0.001 | [1.4,1.6] P<0.001 | [0.9,1.1] P>0.05 | [0.9,1.1] P>0.05 | [0.9,1.0] P<0.01 | [1.3,1.6] P<0.001 | |

| 8+ | 1.2 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.9 |

| [1.1,1.5] P<0.001 | [1.9,2.6] P<0.001 | [1.4,1.8] P<0.001 | [0.7,0.9] P<0.01 | [0.8,1.0] P>0.05 | [0.8,0.9] P<0.001 | [1.6,2.2] P<0.001 | |

| N | 6799 | 8917 | 8575 | 9012 | 9012 | 2653 | 8967 |

Source: Incidence Rate Ratios (IRRs), p-values, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated by the authors based on individual-level data from survey-adjusted and weighted robust Poisson regressions. Models additionally control for age, sex, private health insurance, education, and country.

Only for those with any out of pocket expenditures in the past year. Defined as out of pocket expenditures above the country-specific median.

Only for those with at least one chronic condition.

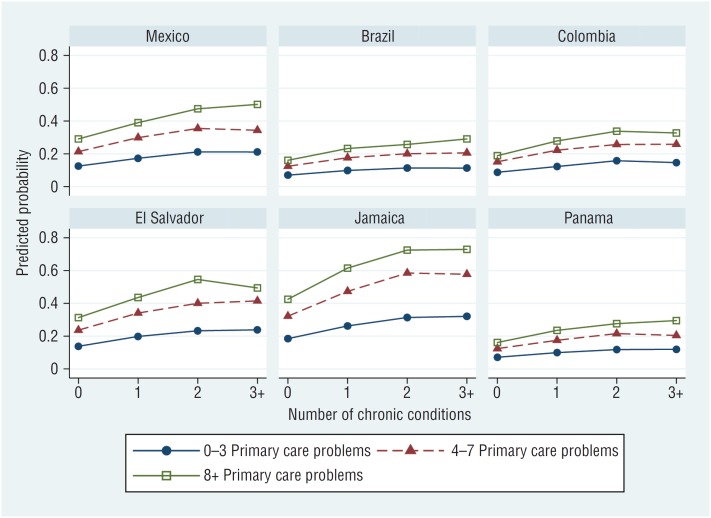

Regression results were used to generate predicted levels of outcome variables (Figure 2). The findings indicate that respondents with more chronic conditions were more likely to have financial difficulties, which were further exacerbated among those with less satisfactory primary care experiences. There were also important country-specific differences; individuals in Brazil, Colombia, and Panama reported fewer financial problems than respondents in the other countries, regardless of the severity of multimorbidity or primary care problems.

FIGURE 2. Reported problems paying medical bills, by number of chronic conditions, primary care problems and country, 2013/2014 survey data.

Predicted values from robust Poisson regression models that additionally control for age, sex, private health insurance, education, and country, calculated by the authors based on individual-level data.

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of a representative sample of adults in six Latin America and Caribbean countries we found that non-communicable diseases are common, with nearly 20% of respondents reporting 2 conditions, and 10% reporting three or more conditions. Most of the examined conditions occur together with others, and diabetes and heart disease are the two problems most often associated with other conditions. Results further show that those with chronic conditions and multimorbidity had more frequent encounters with the health system, which provided some benefits, such as more visits to doctors, better guidance on lifestyle modification and a greater likelihood of being up to date with preventive exams. However, more encounters with the health system entails greater expenditures and higher reported problems paying medical bills even in the countries where healthcare coverage is universal and free of charge at the point of care.

The prevalence of multimorbidity varied substantially across these countries with rates reported in Jamaica almost double those in Colombia. Comparisons with other studies are difficult given methodological differences in measuring multimorbidity (27). A recent study of Brazilian adults found that multimorbidity (based on 14 conditions) was 24.2%, similar to the 24% reported here (28). Another study based on the WHO SAGE data estimated the prevalence of multimorbidity at 21.9% (based on 8 conditions) in six middle income countries (China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia and South Africa) with differing health systems (29).

The findings presented here confirm previous studies suggesting that the prevalence of multimorbidity increases with age (30, 31), is higher among women (30, 32), and is more frequent among those with lower SES (30, 32). Besides confirming these relationships, this study points to the need for health care systems to adapt to rapid population aging. Furthermore, growing numbers of women will have multiple chronic conditions, which are often associated with disability and worse quality of life (33). Even though women generally use health services more frequently (34), which can increase the number of diagnoses, they also tend to be more exposed to poverty and obstacles to adequate treatment (35). The higher burden of multimorbidity among lower socioeconomic groups is particularly important to note as these groups also tend to have greater health care needs, which can lead to impoverishing, and even catastrophic, healthcare expenditures (36).

Even though some of the increased contact with providers can prove beneficial, our results suggest that the benefits depend on the performance of the health care system, whereby those with worse primary care experiences are less likely to report benefits. In fact, individuals with multimorbidity report greater problems with fragmentation of care because most health care systems still tend to be organized around the treatment of single diseases or risk factors. In our sample, only 36% of respondents with three or more conditions reported having a usual source of care, compared to 57% of those with no chronic conditions. Besides encountering problems related to the continuity of care, those suffering from multimorbidity also cited more trouble accessing care, reported a greater proportion of missed exams due to scheduling, and experienced the absence of patient-centered care, with visits too short to address their concerns. These negative experiences reflect major challenges that require substantial health system reorganization.

Changes to improve access, patient centeredness and coordination will also have to tackle healthcare financing. Our results indicate that multimorbidity is associated with greater financial burdens, including difficulty paying for medical treatment and being more likely to have high out-of-pocket expenditures. These results are similar to those described by Lee and colleagues when analyzing middle-income countries using WHO SAGE data (29).

We found that most chronic conditions, except for asthma, cluster with other diseases, a result consonant with other studies (28). Asthma, which is relatively common in the Americas, does not share a similar etiology with the other chronic conditions selected for analysis, which helps explain the lack of co-occurrence. In contrast, diabetes and heart disease are the conditions most commonly clustered with others, and more than 80% of the adults with these conditions had coexisting morbidities. Patients with diabetes often share a cluster of common risk factors, such as unhealthy weight, poor diet, hypertension and sedentary lifestyles, which are also associated with heart disease (37). We found, as well, that conditions like cancer, arthritis and heart disease often occur jointly with three or more additional conditions. These combinations create challenges for adults with chronic conditions to receive accessible, appropriate, and high-quality care. Scheduling and waiting for a doctor's appointment and waiting to receive a medical diagnosis are often reported by those with multimorbidity. For other primary care indicators, the main difference observed was between those without any reported chronic conditions and those with a first diagnosis. Even those with only one chronic condition reported some difficulty asking questions and understanding the information provided by their usual care providers—both of which are essential for managing their conditions properly.

People with chronic conditions report worse self-rated health, which underscores the negative association between multimorbidity and quality of life (38). We find that nearly 50% of people with three or more chronic conditions report having poor/fair health. Therefore, it is important to better understand the difficulties encountered in managing these conditions and thereby develop and implement interventions to improve quality of life. While contemporary examples are limited, the bulk of the evidence suggests that chronic disease interventions will be more effective and sustainable when they target upstream influences affecting risk factors and integrate the range of care with health systems whose foundation is strong primary care (39).

This study had several limitations. Prevalence counts of chronic conditions were obtained by self-reports of diagnoses and measures of disease duration were not included. Under-reporting of chronic conditions varies according to socioeconomic characteristics, such as educational level and access to health insurance, and may have influenced some of our findings(40). However, when we evaluated these relationships in multivariable models, we were able to discern an inverse dose-response relationship by educational level similar to that observed in other studies. Survey questions on chronic conditions did not elicit information on the severity of the condition, which also could alter the frequency of interactions with primary care and overall health care experiences. There is no standard definition of multimorbidity or the inclusion of conditions (27). We therefore selected a combination of eight conditions for our analysis, because they are common health concerns in the region. It is possible that using such a small set of chronic conditions underestimates the true prevalence of multimorbidity. A further limitation may stem from the fact that our data are cross-sectional, as a result of which the possibility of reverse causality cannot be ruled out. For instance, our findings suggested that multimorbidity was associated with more physician visits, but it is possible that more frequent medical encounters simply increased the chances that chronic conditions would be diagnosed.

This study focused on the experiences of adults in six countries that were selected as a purposive sample; therefore, the results cannot be generalized to other countries in the LAC region. The survey had relatively low response rates – Brazil (40.7%), Colombia (29.0%), El Salvador (43.8%), Jamaica (31.1%), Mexico (31.0%), and Panama (33.8%). Nonetheless, these levels are expected given the study design, are comparable to similar studies (41) and lie within the expected parameters of a minimum of 20% established by the Commonwealth Fund (42). We used survey weights so the results were representative of a larger sample, but it is possible that individuals included in the analyses differed systematically from those who did not participate, including those who did not have a telephone, were hospitalized, or were too sick to respond to a telephone survey. Even so, access to telephone, particularly cellphones, has increased dramatically in the region. Except for Jamaica, the number of cellphones per capita is higher in the countries surveyed than in high-income OECD countries (14). Under-coverage of those who have worse health should underestimate multimorbidity estimates and therefore our general findings should be seen as conservative.

Self-reported multimorbidity is relatively common in Latin America and the Caribbean. Clustering of chronic conditions makes it difficult to adequately manage them given that health care systems, health professional training, and clinical guidelines tend to focus on treating individual conditions. Providing adequate care for the expanding number of multimorbid patients will be a challenge for societies that are experiencing rapid population aging, compounded by economic and health system challenges. As health systems move toward consolidating universal health coverage, they will need to assign priority to improving primary care that enhances patient centeredness, facilitates coordination of services, improves health outcomes, reduces costs, and improves the quality of life.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and thank country collaborators.

Footnotes

Suggested citation Macinko J, Andrade FCD, Nunes BP, Guanais FC. Primary care and multimorbidity in six Latin American and Caribbean countries. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2019;43:e8. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2019.8

Funding. Data collection for this study was supported by the Inter-American Development Bank.

Disclaimer. Authors hold sole responsibility for the views expressed in the manuscript, which may not necessarily reflect the opinion or policy of the RPSP/PAJPH, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the IDB, its board of directors, or its technical advisers.

REFERENCES

- 1.Palloni A, McEniry M. Aging and health status of elderly in Latin America and the Caribbean: preliminary findings. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2007;22(3):263–285. doi: 10.1007/s10823-006-9001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glassman A, Gaziano TA, Bouillon Buendia CP, Guanais de Aguiar FC. Confronting the chronic disease burden in Latin America and the Caribbean. [Epub 2010/12/08];Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 29(12):2142–2148. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hospedales CJ, Barcelo A, Luciani S, Legetic B, Ordunez P, Blanco A. NCD Prevention and Control in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Regional Approach to Policy and Program Development. [Epub 2012 Apr 13];Glob Heart. 2012 7(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan American Health Organization The Economic Burden of Non-communicable Diseases in the Americas: an Issue Brief. [Accessed on 7 November 2018]. Available from: http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&gid=15737&Itemid=

- 5.Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, Mangialasche F, Karp A, Garmen A, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. [Epub 2011 Mar 23];Ageing Res Rev. 2011 10(4):430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gijsen R, Hoeymans N, Schellevis FG, Ruwaard D, Satariano WA, Van Den Bos GAM. Causes and consequences of comorbidity: A review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(7):661–674. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nunes BP, Flores TR, Mielke GI, Thumé E, Facchini LA. Multimorbidity and mortality in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. [Epub 2016 Aug 2];Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016 67:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran V-T, Barnes C, Montori VM, Falissard B, Ravaud P. Taxonomy of the burden of treatment: a multi-country web-based qualitative study of patients with chronic conditions. BMC Medicine. 2015;13(1):115–115. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0356-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: Implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294(6):716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM. Designing health care for the most common chronic condition—multimorbidity. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2493–2494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization 2008–2013 Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. 2008.

- 12.Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Alleyne G, Horton R, Li L, Lincoln P, et al. UN High-Level Meeting on Non-Communicable Diseases: addressing four questions. Lancet. 2011;378(9789):449–455. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60879-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever: World Health Report 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guanais FC, Regalia F, Perez-Cuevas R, Anaya M, editors. Desde el paciente: Experiencias de la atención primaria de salud en América Latina y el Caribe. Washington, DC: InterAmerican Development Bank; 2018. Available: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoen C, Osborn R, Doty MM, Bishop M, Peugh J, Murukutla N. Toward higher-performance health systems: adults’ health care experiences in seven countries, 2007. Health Aff. 2007;26(6):w717–w734. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.w717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heeringa SG, West BT, Berglund PA. Applied survey data analysis. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macinko J, Guanais FC, Mullachery P, Jimenez G. Gaps In Primary Care And Health System Performance In Six Latin American And Caribbean Countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(8):1513–1521. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pérez-Cuevas R, Guanais FC, Doubova SV, Pinzón L, Tejerina L, Pinto Masis D, et al. Understanding public perception of the need for major change in Latin American healthcare systems. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(6):816–824. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doubova SV, Guanais FC, Pérez-Cuevas R, Canning D, Macinko J, Reich MR. Attributes of patient-centered primary care associated with the public perception of good healthcare quality in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and El Salvador. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(7):834–843. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czv139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation HDN, The World Bank . The Global Burden of Disease: Generating Evidence, Guiding Policy – Latin America and Caribbean Regional Edition. Seattle, WA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macinko J, Guanais FC. Population experiences of primary care in 11 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Shi L, Starfield B. Validating the Adult Primary Care Assessment Tool. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(2):161–161. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carinci F, Van Gool K, Mainz J, Veillard J, Pichora EC, Januel JM, et al. OECD Health Care Quality Indicators Expert Group. Towards actionable international comparisons of health system performance: expert revision of the OECD framework and quality indicators. International J Qual Health Care. 2015;27(2):137–146. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzv004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(3):307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. [Epub 2003/10/22];BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003 3:21–21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angrist JD, Pischke JS. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist's Companion. Princeton University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Reste JY, Nabbe P, Manceau B, Lygidakis C, Doerr C, Lingner H, et al. The European General Practice Research Network presents a comprehensive definition of multimorbidity in family medicine and long term care, following a systematic review of relevant literature. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(5):319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rzewuska M, de Azevedo-Marques JM, Coxon D, Zanetti ML, Zanetti ACG, Franco LJ, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity within the Brazilian adult general population: Evidence from the 2013 National Health Survey (PNS 2013) PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JT, Hamid F, Pati S, Atun R, Millett C. Impact of noncommunicable disease multimorbidity on healthcare utilisation and out-of-pocket expenditures in middle-income countries: cross sectional analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0127199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Violan C, Foguet-Boreu Q, Flores-Mateo G, Salisbury C, Blom J, Freitag M, et al. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies. PloS One. 2014;9(7):e102149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garin N, Koyanagi A, Chatterji S, Tyrovolas S, Olaya B, Leonardi M, et al. Global multimorbidity patterns: a cross-sectional, population-based, multi-country study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;71(2):205–214. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nunes BP, Thumé E, Facchini LA. Multimorbidity in older adults: magnitude and challenges for the Brazilian health system. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1172–1172. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2505-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrade FCD, Guevara PE, Lebrão ML, de Oliveira Duarte YA, Santos JLF. Gender differences in life expectancy and disability-free life expectancy among older adults in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Women's Health Issues. 2011;21(1):64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Capilheira MF, Santos IdSd. Individual factors associated with medical consultation by adults. Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40(3):436–443. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102006000300011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kingfisher C. Western welfare in decline: Globalization and women's poverty. University of Pennsylvania Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaspers L, Colpani V, Chaker L, van der Lee SJ, Muka T, Imo D, et al. The global impact of non-communicable diseases on households and impoverishment: a systematic review. [Epub 2014/12/21];Eur J Epidemiol. 2015 30(3):163–188. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9983-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martín-Timón I, Sevillano-Collantes C, Segura-Galindo A, del Cañizo-Gómez FJ. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: Have all risk factors the same strength? World J Diabetes. 2014;5(4):444–470. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i4.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C, Vanasse A, Ntetu AL, Maltais D. Multimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2(1):51–51. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, Hudon C, O’Dowd T. Managing patients with multimorbidity: systematic review of interventions in primary care and community settings. BMJ. 2012;345:e5205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burgard SA, Chen PV. Challenges of health measurement in studies of health disparities. Soc Sci Med. 2014;106:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vallance JK, Eurich DT, Gardiner PA, Taylor LM, Stevens G, Johnson ST. Utility of telephone survey methods in population-based health studies of older adults: an example from the Alberta Older Adult Health Behavior (ALERT) study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):486–486. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty MM. Access, affordability, and insurance complexity are often worse in the United States compared to ten other countries. Health Aff. 2013;32(12):2205–2215. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]