Short abstract

Objective

Pediatricians have used podcasts to communicate with the public since 2006 and medical students since 2008. Previous work has established quality criteria for medical education podcasts and examined the benefit of offering continuing medical education (CME) credit for online activities. This is the first descriptive study to outline the development and reach of a pediatric podcast that targets post-graduate healthcare providers, enhances communication by incorporating quality criteria, and offers free accredited CME to listeners.

Methods

We produced 26 podcast episodes from March 2015 to May 2017. Episodes incorporated quality criteria for medical education podcasts and offered free CME credit. They were published on a website, available for listening on multiple digital platforms and promoted through several social media channels. Data were analyzed for frequency of downloads and geographic location of listeners.

Results

The cumulative total of episode downloads was 91,159 with listeners representing 50 U.S. states and 108 countries. Podcast listenership grew over time. Individual episodes had their largest number of downloads immediately following release, but continued recruiting new listeners longitudinally, suggesting use of the archive as an “on-demand” source of educational content.

Conclusions

Pediatric podcasts that incorporate quality criteria and offer free CME credit can be used to deliver educational content to a large global audience of post-graduate healthcare providers. Since podcast communication is rapidly growing, future work should focus on identifying the professional roles of listeners; exploring listener perceptions of quality, value and satisfaction; and examining podcast impact on knowledge transfer, clinical practice, public policy and health outcomes.

Keywords: Continuing medical education, faculty development, free open access medical education, healthcare communication, medical knowledge, pediatrics, podcast, social media

Introduction

The integration of digital technology into clinical practice, medical education and biomedical research supports new opportunities for the delivery of medical content.1–3 Podcasts are episodic digital audio recordings used to communicate knowledge through the use of downloaded files and online streaming.4 With over 3 billion annual downloads,5 podcast familiarity and listenership is growing. Between 2006 and 2017, the percentage of Americans aware of podcasts grew from 22% to 60%, and those who had listened to at least one podcast grew from 11% to 40%.6 Monthly listenership is also increasing, with the percentage of Americans listening to a podcast in the past month growing from 9% to 24% between 2008 and 2017.6 Podcasts support the communication of medical education content in a large number of disciplines,7–16 and have the potential to reach beyond the local learner, attracting national and international audiences.13,15

Pediatric podcasts for the general public have been available since 2006.17 The use of pediatric podcasts within a medical school curriculum began in 2008,18 and several podcasts currently target pediatric healthcare providers.19–23 In an effort to improve this form of digital communication, quality criteria for medical education podcasts have been described.24 Additionally, the number of physicians seeking medical education online is rapidly growing,25,26 and the perceived credibility and preference for online activities increases when continuing medical education (CME) credit is offered.26 Despite these findings, and a call for physicians to participate in the development and surveillance of medical education podcasts,27,28 there are no descriptive articles outlining the development and reach of a pediatric podcast that incorporates published quality indicators for these digital audio programs.

Methods

Development of our podcast began with a definition of the program’s target audience: pediatric healthcare providers with an interest in continuing medical education, faculty development, technology, and innovation. We enlisted help from several institutional partners at Nationwide Children’s Hospital (NCH), including marketing and public relations, the medical staff office, information services, legal services, and the education department. Infrastructure development grew from experience producing PediaCast: A Pediatric Podcast for Parents.17 This parent-focused podcast began in 2006, and is recorded in an audio studio on our hospital campus, located in Columbus, Ohio. The new endeavor would share studio space and be named PediaCast CME, a reference to the established podcast and the intended audience and educational nature of the new program. Infrastructure development for PediaCast CME was funded by NCH marketing and a grant from the medical staff office education endowment fund. These resources provided an annual budget of U.S. $3000 to cover equipment, software, web development, and podcast-hosting needs, as well as 0.2 full-time equivalent (FTE) salary allocation to provide time for podcast planning, recording, and production. In keeping with the tenants of free open-access medical education (FOAM),8,29 we decided to distribute the podcast across multiple digital platforms and not require payment from those wishing to listen and claim credit.

NCH marketing and information services collaborated in creating a WordPress website,30 which was published at PediaCastCME.org.31 The website included plug-ins,32,33 allowing listeners to sign-up for a free member account, complete post-tests, and claim free AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Each podcast episode had a dedicated page on the website, which included an audio player, CME instructions, speaker credentials, disclosure statements, learning objectives, hyperlinks to cited references and resources, and a four-question post-test. The website also provided a contact form, which allowed listeners to communicate with the program, and a terms of use agreement developed by NCH legal services. CME accreditation was provided by the NCH education department. We uploaded monthly episodes as mp3 audio files to Libsyn,34 a popular podcast service offering unlimited downloads and advanced listener statistics. We created a new episode page on the PediaCast CME website with each new release,31 and updated our Rich Site Summary (RSS) feeds.35 When the podcast launched, we had registered these feeds with numerous podcast repositories,36,37 including iTunes,38 Google Play,39 iHeartRadio,40 Stitcher,41 and Tune-In.42 Web-based audio players use RSS feeds to populate content; and registering feeds with iTunes ensures episodes are available in third-party podcast apps on a variety of digital platforms, including computers, televisions, and smartphones.43 We promoted new episodes through PediaCast and NCH accounts on Facebook,44 Twitter,45 Google Plus,46 and Pinterest.47 We also announced each release to NCH-affiliated faculty and staff by email. Following publication, we conducted listenership analysis with the Libsyn Advanced Statistics Tool,48 which reports frequency of episode downloads and geographic location of listeners.

When PediaCast CME launched, there were no published quality indicators for medical education podcasts. Quality was initially addressed by meeting standards for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Securing accreditation had additional benefits. Offering CME credit improves the perceived credibility of online educational activities,26 and meets a growing need because the number of physicians seeking online CME is rapidly increasing.25,26 During the first year of PediaCast CME production, an international group of healthcare educators developed quality indicators for medical education podcasts.24 Ten indicators achieved ≥90% consensus from the group. These describe several domains, including content, credibility, bias, transparency, academic rigor, functionality, orientation, and professionalism. We used the indicators to evaluate past episodes of the program and to inform development of future ones (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Quality indicators for medical education podcasts recommended by Lin et al.24

| Quality indicator | Domain | Consensusa | How this was met |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do the authorities that created the resource list their conflict of interest? | Bias Credibility |

100 | Conflicts of interest were published on the website. |

| Is the information presented in the resource accurate? | Academic Rigor Content |

100 | Content experts participated in the development of each episode. References were published on the website. |

| Is the identity of the resource’s author clear? | Credibility Transparency |

95 | Names and credentials of content experts were stated in each episode and published on the website. |

| Does the resource make a clear distinction between fact and opinion? | Bias Credibility |

95 | Presenters differentiated fact and opinion. References were published on the website |

| Does the resource employ technology that is universally available to allow learners with standard equipment and software access? | Design Functionally |

94 | Episodes were accessible with standard equipment and technologies (computer, mobile device, web browser, internet access) and did not require additional software or payment. |

| Does the resource clearly differentiate between advertisement and content? | Bias Credibility |

90 | No advertising or commercial funding was used. |

| Is the resource transparent about who was involved in its creation? | Credibility Transparency |

90 | Podcasts were recorded and produced at Nationwide Children’s Hospital by a variety of content experts. Names and credentials of those involved were stated in each episode and published on the website. |

| Is the content of this educational resource of good quality? | Content | 90 | Learning objectives and post-tests were published on the website. Each episode was designated for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. |

| Is the content of the resource professional? | Content Professionalism |

90 | Detailed planning and research ensured each episode was accurate and professional. Episodes were recorded in an audio studio and edited to enhance sound quality. |

| Is the resource useful and relevant for its intended audience? | Content Orientation |

90 | The intended audience was post-graduate pediatric providers. Topics were chosen, episodes planned and CME provided with this audience in mind. |

aPercent consensus among 44 health professions educators at the 2014 International Conference on Residency Education.

Each PediaCast CME episode presented a single medical knowledge or faculty development topic to satisfy the needs of community and academic-based pediatricians. Episode planning followed a typical sequence: defining the topic, writing learning objectives and interview questions, researching content, gathering references and resources, and creating a four-question post-test. Episodes averaged 1 h in length and included an interview with one or more content experts. Experts consisted of local faculty, visiting professors and remote guests connected to the studio by telephone. Each guest completed a podcast release form. This was created by NCH legal services and granted consent for participation in the recording and release of the episode.

Results

Twenty-six podcast episodes were produced between March 2015 and May 2017. Individual episode descriptions, running time, and download numbers are presented in Table 2. Sixteen episodes had a medical knowledge focus, while the remaining episodes focused on faculty development topics. The mean duration of each episode was 61 min (range 46–72 min). The total number of podcast downloads was 91,159. Medical knowledge topics averaged 3837 downloads per episode (range 1903–8352), while the faculty development topics averaged 2978 (range 1437–9055) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

PediaCast CME episode descriptions and downloads.

| Release date | Episode title | Focus | Length | Downloads |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 20, 2015 | Doctors Teaching Doctors | Faculty Development | 59:12 | 1549 |

| April 2, 2015 | Micro-Teaching in Medical Education | Faculty Development | 46:16 | 1652 |

| April 23, 2015 | Medical Marijuana | Medical Knowledge | 53:33 | 2291 |

| May 20, 2015 | Difficult Learners | Faculty Development | 1:03:20 | 1818 |

| June 10, 2015 | Refining the Sports Physical | Medical Knowledge | 57:57 | 2127 |

| July 7, 2015 | ADHD, Oppositional Defiant, Aggression | Medical Knowledge | 57:48 | 3158 |

| July 22, 2015 | Mood Disorders, Anxiety, Schizophrenia | Medical Knowledge | 1:00:29 | 2969 |

| August 19, 2015 | Evidence-Based Medicine | Faculty Development | 1:03:11 | 2194 |

| September 16, 2015 | Migraine & Tension-Type Headaches | Medical Knowledge | 1:01:58 | 3405 |

| November 4, 2015 | Work-Life Balance | Faculty Development | 57:44 | 1863 |

| January 6, 2016 | Appendicitis & the Non-Operative Approach | Medical Knowledge | 53:51 | 1903 |

| January 27, 2016 | Critical Reflection | Faculty Development | 53:05 | 1860 |

| April 6, 2016 | Type 2 Diabetes | Medical Knowledge | 59:03 | 2017 |

| April 27, 2016 | Introduction to Mentoring | Faculty Development | 1:01:48 | 1437 |

| June 9, 2016 | Pediatric Hypertension | Medical Knowledge | 48:20 | 1933 |

| June 29, 2016 | Taking the HEAT | Faculty Development | 1:05:16 | 1816 |

| July 21, 2016 | Birth Control for Teenagers | Medical Knowledge | 1:10:50 | 3326 |

| July 27, 2016 | Food Allergies | Medical Knowledge | 1:03:14 | 3060 |

| September 21, 2016 | Lyme Disease | Medical Knowledge | 1:06:32 | 7125 |

| September 28, 2016 | Health Literacy | Faculty Development | 1:07:37 | 6531 |

| November 16, 2016 | RSV Bronchiolitis | Medical Knowledge | 1:03:23 | 8352 |

| January 25, 2017 | Motor Delay Screening | Medical Knowledge | 59:15 | 4755 |

| February 15, 2017 | Not Another Boring Lecture! | Faculty Development | 1:10:16 | 9055 |

| March 1, 2017 | Support for Breastfeeding Moms | Medical Knowledge | 1:05:28 | 7520 |

| April 12, 2017 | Transitioning Pediatric Patients to Adult Health Care | Medical Knowledge | 1:05:11 | 4026 |

| May 17, 2017 | Toxic Stress & Resiliency | Medical Knowledge | 1:12:58 | 3417 |

Podcasts were downloaded in 50 U.S. states and 108 countries. States with the most downloads were Virginia, Ohio, California, Texas, and New York. Countries with the most downloads were the United States, France, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Japan. A complete list of U.S. and international downloads is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Geographic reach of PediaCast CME.

| State | Downloads | Country | Downloads | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Virginia | 14,496 | 1 | United States | 73,093 |

| 2 | Ohio | 13,033 | 2 | France | 6588 |

| 3 | California | 10,515 | 3 | Canada | 2103 |

| 4 | Texas | 3552 | 4 | United Kingdom | 1877 |

| 5 | New York | 2304 | 5 | Japan | 1363 |

| 6 | Michigan | 2257 | 6 | Australia | 939 |

| 7 | Pennsylvania | 2192 | 7 | South Africa | 859 |

| 8 | Oregon | 2188 | 8 | Germany | 521 |

| 9 | New Jersey | 1942 | 9 | Denmark | 303 |

| 10 | Illinois | 1715 | 10 | China | 232 |

| 11 | Florida | 1630 | 11 | Netherlands | 207 |

| 12 | North Carolina | 1447 | 12 | Saudi Arabia | 189 |

| 13 | Massachusetts | 1234 | 13 | Philippines | 180 |

| 14 | Minnesota | 1002 | 14 | Taiwan | 153 |

| 15 | Colorado | 920 | 15 | Spain | 136 |

| 16 | Maryland | 867 | 16 | Mexico | 135 |

| 17 | Washington | 839 | 17 | New Zealand | 134 |

| 18 | Georgia | 827 | 18 | Switzerland | 124 |

| 19 | Indiana | 686 | 19 | Russian Federation | 103 |

| 20 | Tennessee | 665 | 20 | Hong Kong | 88 |

| 30 other states | 8782 | 88 other countries | 1832 |

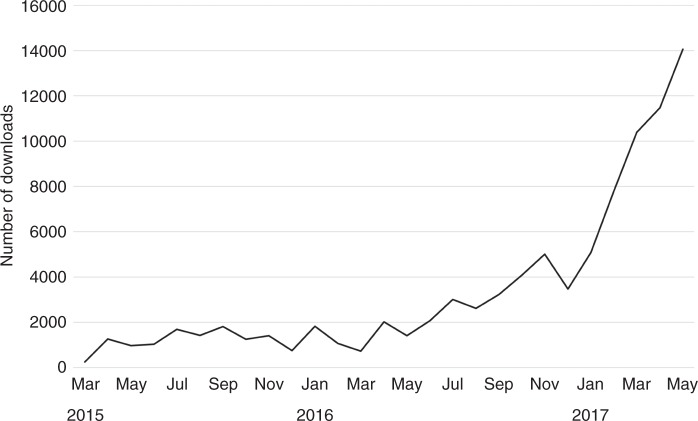

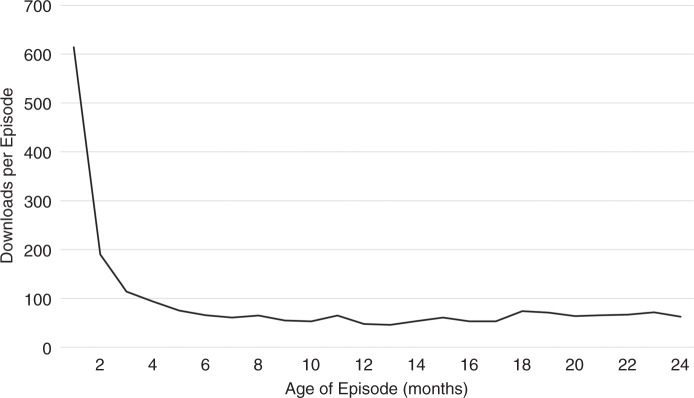

Comparing early production (April to June 2015) with later production (March to May 2017), average monthly downloads increased from 1087 to 11,975 (see Figure 1). Episodes 1–10 were available in the archive ≥18 months. Downloads of these episodes were highest during the first month following release. Listenership then declined over 6 months before remaining steady through the remainder of the study period (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

PediaCast CME growth in monthly downloads of all published episodes.

Figure 2.

Recruitment of new listeners by episode age (PediaCast CME episodes 1–10).

A total of 943 individuals registered to claim CME credits at the PediaCast CME website.31 Registered members represented 45 states and 19 countries, and claimed 2103 hours of AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Half of the registrants (51%) were affiliated with NCH (n = 478). The professional roles of CME registrants were physician (n = 517, 54.8% of all participants), advanced practice nurse or physician assistant (n = 160, 17.0%), nurse (n = 158, 16.8%), other healthcare provider (n = 79, 8.4%), student (n = 13, 1.4%), researcher (n = 11, 1.2%), and parent/consumer (n = 5, 0.5%).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the development and reach of a pediatric medical education podcast that communicates with post-graduate healthcare providers. The podcast was available on numerous digital platforms, adhered to the tenets of FOAM,8,29 met relevant quality indicators for medical education podcasts24 and offered free AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™.

Previous work has highlighted the use of digital technology in the dissemination of medical knowledge.1–3 One of these digital technologies, the audio podcast, has been shown useful in the communication of pediatric educational content within a medical school curriculum.18 Additional studies have shown the utility of podcast communication in several other medical disciplines.7–16 Medical education podcasts have been shown to reach beyond the local learner, attracting national and international audiences.13,15 Quality indicators have been established for medical education podcasts,24 and the benefits of offering CME credit for online activities has been described.25,26 This study supports and strengthens these findings. It adds to the collective evidence by describing the development and reach of a pediatric podcast that successfully targets post-graduate healthcare providers, incorporates quality criteria for medical education podcasts, offers free CME credit, and communicates with a large global audience of listeners.

This study also demonstrates the recruitment of episode listeners longitudinally (Figure 2). This suggests listeners not only download episodes as they are released, but also use the podcast archive as an “on demand” educational repository, a finding consistent with studies in other disciplines.4,13,49 This is informative for individuals and institutions seeking an asynchronous method for the communication of medical education content. The total number of episode downloads increased dramatically beginning in December 2016 (Figure 1). The reason for this rapid increase in downloads is not entirely clear. Older episodes continued to recruit new listeners, but only at a rate of 50–75 downloads per month (Figure 2). This does not account for the rise in monthly downloads from 3800 in December 2016 to 14,000 in May 2017. We did not change the manner in which we released or promoted the program and surmise the increase in total monthly downloads was likely due to exponential awareness of the program among national and international audiences as our listeners shared the show within their own social media communities.

Half of CME registrants (51%) were affiliated with NCH. This is likely due to an elevated awareness of the program among local faculty and staff. Compared with the number downloads, a relatively small percentage of listeners claimed CME credit. However, since offering CME credit improves the perceived credibility of online educational activities,26 it is possible that listeners engaged the podcast because of the CME offering even if they had no plan to claim credit. Furthermore, given the dramatic growth in podcast downloads, it is likely listeners found gain beyond earning AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Possible reasons for low CME participation include lack of awareness that CME was offered, difficulty using technology, and obtaining CME credit elsewhere. Also, given the large number of international listeners and the professional diversity of participants, many listeners may have required a different type of continuing education credit or no credit at all.

Finally, this study supports the development of future medical education podcasts by describing infrastructure development, the inclusion of quality criteria and CME accreditation, and methods of content creation, episode release, and social media promotion. Aspiring producers will find podcasts relatively easy to produce and distribute. Audio recording equipment and software is available for a variety of budgets,50–52 step-by-step instructions exist for creating, hosting and distributing podcasts,53,54 and social media channels can be utilized to enhance global reach.55–57

Podcast producers can also participate in healthcare communications and social media curricula,58,59 which aim to develop message-crafting skills and digital-engagement strategies.

A limitation of this study is the use of podcast downloads to represent listeners. In an effort to avoid counting duplicate downloads, Libsyn Advanced Statistics counts each IP address once and ignores spikes in file access by web robots and search engines.48 This improves the accuracy of using downloads to represent listeners, but it is still possible for an individual to download an episode and listen to only a portion of audio or not listen at all.

Conclusion

It is possible to develop a pediatric medical educational podcast that targets post-graduate healthcare providers and reaches a global audience of listeners. Given this reach, audio podcasts appear to be an effective means of communicating pediatric knowledge and faculty development content. Those planning to develop a medical educational podcast can use quality indicators to inform content creation and abide by the tenants of FOAM by making episodes freely available on a variety of digital platforms.8,24,29 Inclusion of episodes in podcast repositories, such as iTunes and Google Play, and promotion of episodes through social media channels is associated with the recruitment of a large global audience. Those wishing to offer AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ will need to partner with an accredited organization. Further institutional collaboration with marketing and public relations, medical staff office, information services, legal services, and education department will provide additional support for a successful program. Future work should continue to identify the professional roles of those who listen to medical education podcasts and explore listener perceptions of quality, value, and satisfaction. This will help podcast producers refine content, align educational goals with listener need, and further improve the implementation of this digital communication strategy. Another opportunity for future study is an evaluation of how podcasts impact consumer and professional perceptions of sponsoring institutions, and how podcasts affect medical referral patterns. Finally, since podcast listenership is growing rapidly, future study should examine the impact podcasts have on knowledge transfer, clinical practice, public policy, and health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Stephanie Cannon, Donna Teach, William Long, Karyn Wulf, Bruce Meyer, and Roger Friedman for their help and support with the PediaCast CME project.

Contributorship

All authors are responsible for the reported research and have participated in the concept and design; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting or revising of the manuscript, and all have approved the manuscript as submitted.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was used for this manuscript.

Guarantor

Michael D. Patrick

Peer review

This manuscript was reviewed by Michael Cosimi, Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, USA and one other individual who has chosen to remain anonymous.

References

- 1.Baird A, Nowak S. Why primary care practices should become digital health information hubs for their patients. BMC Fam Pract 2014; 15:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yazdani S, Khoshgoftar Z, Ahmady S, et al. Medical education in cyberspace: critical considerations in the health system. J Adv Med Educ Prof 2017; 5(1):11–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckarma EH, Thiels CA, Gas BL, et al. Influence of social media on the dissemination of a traditional surgical research article. J Surg Educ 2017; 74(1):79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lichtenheld A, Nomura M, Chapin N, et al. Development and implementation of an emergency medicine podcast for medical students: EMIGcast. West J Emerg Med 2015; 16(6):877–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pew Research Center. Podcasting: Number of podcast download requests, http://www.journalism.org/2016/06/15/podcasting-fact-sheet;/ (2016, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 6.Edison Research. The Podcast Consumer 2017, http://www.edisonresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Podcast-Consumer-2017.pdf (2017, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 7.Alikhan A, Kaur RR, Feldman SR. Podcasting in dermatology education. J Dermatolog Treat 2010; 21(2):73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadogan M, Thoma B, Chan TM, et al. Free Open Access Meducation (FOAM): the rise of emergency medicine and critical care blogs and podcasts (2002–2013). Emerg Med J 2014; 31(e1):e76–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadjianastasis M, Nightingale KP. Podcasting in the STEM disciplines: the implications of supplementary lecture recording and ‘lecture flipping'. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2016; 363(4): pii: fnw006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Childers RE, Dattalo M, Christmas C. Podcast pearls in residency training. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160(1):70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matava CT, Rosen D, Siu E, et al. eLearning among Canadian anesthesia residents: a survey of podcast use and content needs. BMC Med Educ 2013; 13:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meade O, Bowskill D, Lymn JS. Pharmacology podcasts: a qualitative study of non-medical prescribing students' use, perceptions and impact on learning. BMC Med Educ 2011; 11:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nwosu AC, Monnery D, Reid VL, et al. Use of podcast technology to facilitate education, communication and dissemination in palliative care: the development of the AmiPal podcast. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017; 7(2):212–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moriarity SA, Burns TM. The Neurology(R) podcast: 2007–2012: can you hear me now? Neurology 2012; 79(10):956–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White JS, Sharma N, Boora P. Surgery 101: evaluating the use of podcasting in a general surgery clerkship. Med Teach 2011; 33(11):941–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirsch JA, Fargen K, Ducruet AF, et al. JNIS podcasts: the early part of our journey. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9(2):211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nationwide Children’s Hospital. PediaCast: A pediatric podcast for parents, http://www.pediacast.org (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 18.Gill P, Kitney L, Kozan D, et al. Online learning in paediatrics: a student-led web-based learning modality. Clin Teach 2010; 7(1):53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Children’s Mercy Kansas City. Transformational pediatrics, https://www.childrensmercy.org/podcasts/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 20.HIPPO Education. Peds RAP, http://www.hippoed.com/peds/rap/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 21.Medscape. Medscape Pediatrics Podcast, https://www.medscape.org/pediatrics (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 22.Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Primary care perspectives: Podcast for pediatricians, http://www.chop.edu/health-resources/primary-care-perspectives-podcast-pediatricians (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 23.Pediatric Emergency Medicine Playbook. PEM Playbook Podcast, http://pemplaybook.org/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 24.Lin M, Thoma B, Trueger NS, et al. Quality indicators for blogs and podcasts used in medical education: modified Delphi consensus recommendations by an international cohort of health professions educators. Postgrad Med J 2015; 91(1080):546–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris JM, Jr, Sklar BM, Amend RW, et al. The growth, characteristics, and future of online CME. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2010; 30(1):3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young KJ, Kim JJ, Yeung G, et al. Physician preferences for accredited online continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2011; 31(4):241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adorisio O, Buonuomo PS, Tozzi AE, et al. Podcasts are yet to make an impact in paediatric journals. J Paediatr Child Health 2010; 46(5):278–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahn J, Inboriboon PC, Bond MC. Podcasts: Accessing, choosing, creating, and disseminating content. J Grad Med Educ 2016; 8(3):435–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nickson CP, Cadogan MD. Free Open Access Medical education (FOAM) for the emergency physician. Emerg Med Australas 2014; 26(1):76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WordPress. Meet WordPress, https://wordpress.org/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 31.Nationwide Children’s Hospital. PediaCast CME, http://www.pediacastcme.org (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 32.Simple Membership. WordPress Membership Plugin, https://simple-membership-plugin.com/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 33.Calendar Scripts. WatuPRO WordPress Plugin, http://calendarscripts.info/watupro/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 34.Libsyn. Libsyn Podcast Hosting, https://www.libsyn.com/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 35.Digital Trends. What is an RSS feed and how can I use it? https://www.digitaltrends.com/computing/how-to-use-rss/ (2017, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 36.Nationwide Children’s Hospital. PediaCast CME RSS Feed, http://www.pediascribe.com/podcast/pediacast-cme.xml (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 37.Nationwide Children’s Hospital. PediaCast RSS Feed for iHeartRadio, http://www.pediascribe.com/podcast/clearchannel/cc-pediacast.xml (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 38.Apple iTunes. PediaCast CME, https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/pediacast-cme/id971329903 (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 39.Google Play Music. PediaCast CME, https://play.google.com/music/listen#/ps/Isnqgujfma2ry5csdlatbi4na2u (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 40.iHeartRadio. PediaCast, https://www.iheart.com/podcast/PediaCast-21231395/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 41.Stitcher. PediaCast CME, http://www.stitcher.com/podcast/pediacast-cme (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 42.Tune In. PediaCast CME, https://beta.tunein.com/radio/PediaCast-CME-p716865/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 43.The Media Briefing. Updated: How to publish your podcast on a variety of platforms, https://www.themediabriefing.com/analysis/updated-how-to-publish-your-podcast-on-a-variety-of-platforms/ (2017, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 44.Facebook. PediaCast, https://www.facebook.com/pediacast/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 45.Twitter. @pediacast, https://twitter.com/pediacast?lang=en (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 46.Google Plus. PediaCast, https://plus.google.com/114792618247465082999 (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 47.Pinterest. PediaCast CME, https://www.pinterest.com/pediacast/pediacast-cme-episodes/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 48.Libsyn. Libsyn Support: Advanced Statistics, https://support.libsyn.com/kb/advanced-statistics/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 49.Copley J. Audio and video podcasts of lectures for campus-based students: production and evaluation of student use. Innov Educ Teach Int 2007; 44(4):387–399. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Podcast Blastoff. How to build a podcast studio on any budget, https://podcastblastoff.com/post/How-to-Build-a-Podcast-Studio-on-Any-Budget (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 51.School of Podcasting. Podcast equipment recommendations, http://schoolofpodcasting.com/equipment/ (2009, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 52.The Podcasters’ Studio. Gear, http://thepodcastersstudio.com/gear/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 53.School of Podcasting. The 27 steps to get your podcast into iTunes, http://schoolofpodcasting.com/the-27-steps-to-get-your-podcast-into-itunes/ (2011, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 54.The Audacity to Podcast. Award-winning “how to” podcast about podcasting to help you launch or improve your own podcast, https://theaudacitytopodcast.com/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 55.The Audacity to Podcast. Eleven ways to use Twitter to promote your blog or podcast, https://theaudacitytopodcast.com/tap067-11-ways-to-use-twitter-to-promote-your-blog-or-podcast/(2012, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 56.Entrepreneur. 8 Ways to drive traffic to your podcast on social media, https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/284274 (2016, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 57.Blubrry. Podcast promotion, https://create.blubrry.com/manual/podcast-promotion/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 58.PediaCast CME. Healthcare communications and social media curriculum, http://pediacastcme.org/hcsm/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).

- 59.Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clinic Social Media Network, https://socialmedia.mayoclinic.org/ (2018, accessed 19 April 2018).