Abstract

Date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) is the most popular fruit in the Middle East and North Africa. It is consumed widely and has been used for traditional medicine purposes for a long time. The fruits are nutrient rich, containing dietary fibers, sugar, protein, vitamins, minerals, flavonoid, and phenolic compounds. Due to the presence of the phenolic compounds, date palm fruits are antioxidant rich with potent bioactivities against several bacterial pathogens. Therefore, on the basis of the available evidence as reviewed in this paper, it was found that date fruits are a good source of natural antioxidants, which can be used for the management of oxidative stress–related and infectious diseases.

KEYWORDS: Antibacterial, antimicrobial, antioxidant, date fruit, Phoenix dactylifera

INTRODUCTION

Phoenix dactylifera (date palm) is a flowering plant belonging to the palm family, Arecaceae, which is mostly cultivated for the consumption of its fruit. Date fruits are a staple food for the people in the Middle East and North Africa, although its original source is still subjected to debate. Now it is mostly cultivated in many tropical and subtropical regions around the world. Moreover, it is now consumed as food in many different parts of the world, especially Europe.[1,2] Date trees can grow as long as 21–23 m, with leaves growing up to 4–6 m and having around 150 leaflets. The trees usually grow singly or in clumps from a single root system. There are currently over 100 million date trees cultivated globally, most of which are in the Middle East (approximately 90%). Therefore, they are currently considerably related to the Arab Muslim world, although historically, it has been linked to early Judaism and Christianity, partly as the tree was heavily cultivated as a food supply in ancient Israel. It is the tradition to eat date fruit first to break the fast during Ramadan fasting of Muslims. For Muslims all over the world, dates are of religious importance and are mentioned in many places in the Quran.[2,3]

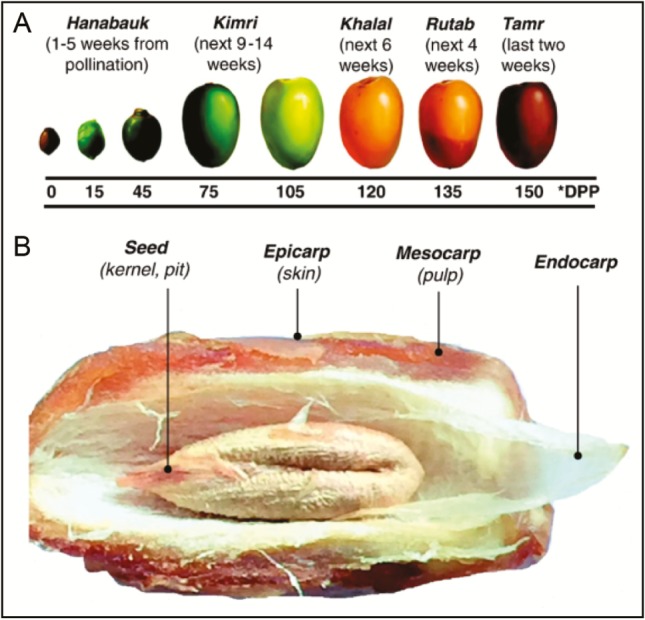

The date fruit is made up of the pericarp, mesocarp, endocarp, and a seed (kernel or pit) as shown in Figure 1. The mesocarp is the largest part, which is composed of parenchymatous cells that are separated into an outer mesocarp and an inner mesocarp with intermediate layers of tanniferous cells.[4] The fruits undergo different stages of development including Hanabauk, Kimri, Khalal (or Besser), Rutab, and Tamr. For the purpose of consumption, date fruits are used at different stages of maturation including Khalal or Besser (the mature but unripe with 50% moisture), Rutab (ripened with 30%–35% moisture), and Tamr (mature with 10%–30% moisture).[5] Aside from consumption of the date fruits, many more dishes are made from these fruits for human consumption.[6]

Figure 1.

(A) Different ripening stages of date palm fruit showing the three edible stages of the fruit Khalal, Rutab, and Tamr. (B) The anatomy of the date fruit at Tamr stage showing the epicarp, mesocarp, endocarp, and seed. (Source: Ghnimi et al.[2]). *DPP = days post-pollination

NUTRITIONAL VALUE OF DATE FRUITS

Date fruits have been reported to contain 6.5%–11.5% total dietary fibers (up to 90% of which is insoluble and 10% of soluble dietary fiber), approximately 1% fat, 2% proteins, and 2% ash. It is also a rich source of phenolic antioxidants.[7] Similarly, the soft date fruit is mostly composed of invert sugars (fructose and glucose) with little or no sucrose, whereas the dry ones have high proportion of sucrose. Accordingly, the fruits are classified based on their sugar type into (i) invert sugar types containing mainly glucose and fructose (e.g., Barhi and Saidy), (ii) mixed sugar types (e.g., Khadrawy, Halawy, Zahidi, and Sayer), and (iii) cane sugar types containing mainly sucrose (e.g., Deglet Nour and Deglet Beidha).[2] Date fruits contain a wide variety of essential nutrients, making them very nutritious. The ripe fruits mostly contain sugar (80%), with smaller amounts of protein, fiber, and trace elements including boron, cobalt, copper, fluorine, magnesium, manganese, selenium, and zinc [Table 1].[8] In view of the nutritious and antioxidant-rich contents of date fruits, there have been attempts to develop functional foods from it.[3]

Table 1.

Nutritional value of date fruits (Deglet Nour)

| Nutrient | Content (per 100 g) |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1178 kJ (282 kcal) |

| Carbohydrates | 75.03 g |

| Sugars | 63.35 g |

| Dietary fiber | 8 g |

| Fat | 0.39 g |

| Protein | 2.45 g |

| Vitamins | |

| Beta-carotene | 6 μg |

| Vitamin A | 10 IU |

| Thiamine (vitamin B1) | 0.052 mg |

| Riboflavin (vitamin B2) | 0.066 mg |

| Niacin (vitamin B3) | 1.274 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (vitamin B5) | 0.589 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 0.165 mg |

| Folate (vitamin B9) | 19 μg |

| Vitamin C | 0.4 mg |

| Vitamin E | 0.05 mg |

| Vitamin K | 2.7 μg |

| Minerals | |

| Calcium | 39 mg |

| Iron | 1.02 mg |

| Magnesium | 43 mg |

| Manganese | 0.262 mg |

| Phosphorus | 62 mg |

| Potassium | 656 mg |

| Sodium | 2 mg |

| Zinc | 0.29 mg |

| Water | 20.53 g |

Source: USDA Nutrient Database[8]

Table 2 shows the major phenolic classes and types found in the date fruit. The content of antioxidants varies even though these fruits are believed to be rich in antioxidants.[9] For example, soluble phenolic compounds in Omani dates were reported to be considerably high (217–343 mg ferulic acid equivalents/100 g) compared to other fruits.[2] However, storage conditions have also been shown to affect the antioxidant content and the activity of date fruits.[10] Storage at ambient temperature may be decreased as result of conversion of soluble tannins into insoluble tannins[11] and enzymatic oxidation of flavans and caffeoylshikimic acid.[12,13] The health-promoting effects of date fruits are reported to be due to secondary metabolites of their phenolic compounds, which form an integral component of a fruit’s structural and cellular integrity.[14]

Table 2.

Phenolic compounds in date fruits

| Class | Compounds |

|---|---|

| Benzoic acid and derivatives | Gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, vanillic acid, syringic acid, sinapic acid |

| Cinnamic acid and derivatives | Caffeic acid, hydrocaffeic acid, ferulic acid, p-coumaric acid, syringic acid, dactyliferic acid, 2 caffeoylshikimic acid hexoside, 3-caffeoylshikimic acid, 4-caffeoylshikimic acid, 5-caffeoylshikimic acid, caffeoylsinapoyl hexoside, and dicaffeoylsinapoyl hexoside |

| Flavonoid glycosides and esters | Luteolin, quercetin, and apigenin, quercetin rhamnosyl-hexoside sulfate, quercetin 3-O-rutinoside (rutin), quercetin hexoside sulfate, quercetin acetyl-hexoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside, isorhamnetin hexoside, chrysoeriol rhamnosyl-hexoside, isorhamnetin acetyl-hexoside, quercetin 3-O-glucoside (isoquercitrin), chrysoeriol hexoside sulfate, and chrysoeriol hexoside |

| Flavan-3-ols | (+)-catechin, and (−)-epicatechin |

| Proanthocyanidins | Procyanidin oligomers based on (−)-epicatechin including procyanidin B1, procyanidin B2, procyanidin trimer, procyanidin tetramer, procyanidin pentamer, and procyanidin polymers based on (−)-epicatechin (decamers to heptadecamers) |

| Anthocyanins | Cyanidin (in some dark varieties) |

Source: Ghnimi et al.[2]

However, the classes of antioxidants commonly found in date fruits have all been reported to elicit strong antioxidant activities with the potential to ameliorate oxidative stress–related diseases and infectious diseases.[2]

ANTIOXIDANT AND ANTIMICROBIAL PROPERTIES OF DATE FRUITS

Date fruit is used as traditional medicine in some cultures for the treatment of ailments such as intestinal disorders, fever, bronchitis, and wound healing. This is because of their wide variety of essential nutrients. Recent studies have provided more evidence for the use of date fruits for medicinal purposes. Accordingly, preclinical studies have shown that date fruit has antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity. More studies, especially human trials, are however still needed to evaluate the clinical validity of these findings. Similarly, the mechanism of action of the compounds in date fruits warrants investigation.[9]

STUDIES BASED ON GEOGRAPHICAL ORIGIN OF DATE FRUITS

Most studies on the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of date fruits are from the Middle East and North Africa with a few from other parts of the world [Table 3]. Moroccan date fruits were studied by Bammou and colleagues (2016)[15] for their phenolic contents. Date fruit is one of the oldest known staple crops in Morocco. This study evaluated six varieties of ripe date fruits (Bouskri, Bousrdon, Bousthammi, Boufgous, Jihl, and Majhoul), the results of which showed that the compounds present in date fruit exhibited antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Specifically, Bousrdon and Jihl had the highest antioxidant potentials based on their phenolic and flavonoid contents, whereas Jihl had the highest antioxidant activity based on the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) scavenging activity and ferric-reducing power. Similarly, Bousrdon and Jihl extracts had the strongest activities against select microbes including gram-positive (Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus) and gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella abony). There was also a high correlation between the observed biological activities and antioxidant properties.[15]

Table 3.

Summary of the functional properties of Phoenix dactylifera

| Source of the sample (reference) | Study protocol | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Saudi Arabia[3] | Commercially purchased date fruit from a market in Madinah | Flavonoid glycosides extracted from the date fruits had significant antibacterial activity against imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa. The major flavonoids found in the extract were quercetin, luteolin, and apigenin. |

| Morocco[15] | Six varieties of ripe date fruits (Bouskri, Bousrdon, Bousthammi, Boufgous, Jihl, and Majhoul) | Bousrdon and Jihl had the highest antioxidant potentials based on their phenolic and flavonoid contents. Jihl had the highest antioxidant activity based on DPPH scavenging activity and a ferric-reducing power. Bousrdon and Jihl extracts had the strongest activities against select microbes including gram-positive (Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus) and gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella abony). |

| Mauritania[16] | Six varieties of ripening (Blah) and fully ripe (Tamr) date fruits: Ahmar dli, Ahmar denga, Bou seker, Tenterguel, Lemdina, and Tijib | The Blah stage had higher polyphenols and flavonoids from all varieties based on total phenolic and flavonoid contents. It also had the highest total antioxidant activity, and a high positive correlation was found between total phenolics and TEAC of the fruit methanolic extracts compared to the flavonoids, suggesting that phenolics were the major contributor to the antioxidant activity. |

| Malaysia[10] | Effects of chilling and storage on antibacterial properties and antioxidant capacities of Saudi Arabian cultivars (Mabroom, Safawi, and Ajwa) versus the Iranian cultivar (Mariami) | After storage at 20°C and 4°C for 5 weeks, Mariami had the highest TAC (3.18 and 1.40 mg cyd 3-glu/100 g DW, respectively), whereas Mabroom had the lowest TAC (0.54 and 0.15 mg cyd 3-glu/100 g DW, respectively). The TAC of all extracts increased after storage. The chilling of date palm fruits for 8 weeks before solvent extraction elevated the TPC of all date fruit extracts, except for methanolic extracts of Mabroom and Mariami. The TPC of all cultivar extracts decreased after 5 weeks of extract storage. IC50 values of all cultivar extracts increased after extract storage, except for the methanolic extracts of Safawi and Ajwa. Different cultivars exhibited different antibacterial properties. Only the methanolic extract of Ajwa exhibited antibacterial activity against all four bacteria tested: S. aureus, B. cereus, Serratia marcescens, and E. coli. |

| Sudan[17] | Six varieties of ripe date fruits (Barakawi, Gondaila, Jaw, Mishrig, Bittamoda, and Madini) | All date varieties were found to have good amounts of total polyphenols and total flavonoids (35.82–199.34 mg GAE/100 g and 1.74–3.39 mg catechin equivalent/100 g, respectively). Bittamoda and Madini had the highest TPC, whereas Bittamoda and Gondaila had the highest TFC. They also had high antioxidant activities including ferric-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), chelation of Fe2+ ion, and scavenging of H2O2. |

| Algeria[18] | Seven varieties of ripe date fruits (Tantebouchte, Biraya, Degla Baidha, Deglet-Nour, Ali Ourached, Ghars, and Tansine) | All varieties had high polyphenols, flavonoids, and flavonols, although the methanolic extract of Ali Ourached cultivar had the highest |

| USA[19] | Six commercially available varieties of date fruits: Deglet Nour (Algeria), Deglet Nour (California), Deglet Nour (Tunisia), Shahia (Tunisia), Barni (Saudi Arabia), and Khudri (Saudi Arabia) | Total phenolic contents were found to be high (33–125 mg GAE/100 g dry weight), although Barni (Saudi Arabia) had the highest. Antioxidant activities were also found to be high based on DPPH, FRAP, and ORAC. |

| Oman[20] | Twenty-two varieties of date fruits (Fardh, Helali Oman, Manhi, Qush Basrah, Handal, Naghal, Qushbu Maan, Qushbu Norenjah, Qush Balquan, Qush Jabri, Seedi, Khasab, Khunaizi, Barshi, Qush Mamoor, Barni, Azad, Zabad, Khalas, Qush Tabak, Qush Lulu, and Halali Alhasa) | All varieties showed high antioxidant activity (40%–86%); Khasab, Khalas, and Fardh had the highest activities. |

| Saudi Arabia[21] | Two date fruit varieties (Al Sagey, Helwat Al Jouf, and Al Sour) | All varieties possessed potent antioxidant capacities because of their rich phenolic (caffeic acid, ferulic acid, protocatechuic acid, catechin, gallic acid, p-coumaric acid, resorcinol, chlorogenic acid, and syringic acid) and flavonoid (quercetin, luteolin, apigenin, isoquercitrin, and rutin) contents. Al Sagey cultivar possessed the strongest antioxidant capacities and the highest phenolic contents. Al Sagey and Helwat Al Jouf showed comparable glutathione and ascorbate redox status, whereas in Al Sour, glutathione redox status was the least. |

| UK[22] | Three commercially available date fruits (Deglet Nour, Khouat Allig, and Zahidi) | The majority of the total phenolic content (2058–2984 mg GAE/100 g) was assumed to be composed of flavonoids (1271–1932 mg CAE/100 g). These families of dietary phenolics may be the major ones responsible for the high antioxidant capacity reported in date seeds, which varied from 12540 and 27699 μmol TE per 100 g |

| Saudi Arabia[23] | Mosaifah variety fruit, seed, leaf, and bark were studied | The fruit had the highest antibacterial activity against S. aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa. Carbohydrates, alkaloids, flavonoids, steroids, saponins, and +tannins were the major constituents identified. |

| Tunisia[24] | Three cultivars (Allig, Deglet Nour, and Bejo) | All cultivars showed strong antioxidant activities and contents, although Allig had the highest followed by Bejo and Deglet Nour. Antioxidant activities correlated positively with the total phenolic and flavonoid contents of the dates. |

| Tunisia[35] | Four cultivars (Gondi, Gasbi, Khalt Dhahbi, and Rtob Ahmar) of Tunisian date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) fruits at three maturation stages, Besser, Rutab, and Tamr | All cultivars showed highest antioxidant potentials (TPC, TFC, CTC, and AA) at Besser stage, and a significant correlation (P < 0.05) was found between the antioxidant activities and ripening. The major phenolics found were caffeic acid, ferulic acid, protocatechuic acid, and catechin for all cultivars. |

| Saudi Arabia[25] | Five cultivars (Helali, Medjool, Lonet-Mesaed, Khenazi, and Barhee) during different stages of ripening | The antioxidant capacity measured by the DPPH method and the antioxidant compound (phenols, tannins, and vitamin C) concentrations decreased from young stages through to the maturation and the ripening stages. The antioxidant capacity was highly positively correlated with the concentration of antioxidant compounds in most cultivars. The activities of the antioxidant enzymes, peroxidase, catalase, and polyphenol oxidase increased from the Hanabauk through to the Kimri and/or the Besser stage, on cultivar, and thereafter, declined at the ripening stages. |

| Algeria[26] | Ten cultivars (Mech Degla, Deglet Ziane, Deglet Nour, Thouri, Sebt Mira, Ghazi, Degla Beida, Arechti, Halwa, and Itima) | Ghazi, Arechti, and Sebt Mira possessed the strongest antioxidant capacities and the highest phenolic contents. Four phenolic acids (gallic, ferulic, coumaric, and caffeic acids) and five flavonoids (isoquercitrin, quercitrin, rutin, quercetin, and luteolin) were identified. |

| Tunisia[27] | Ten Tunisian date varieties (Smiti, Kenta, Bekrari, Mermella, Garn ghzal, Nefzaoui, Baht, Korkobbi, Bouhattam, and Rotbi) | Results showed that date fruit varieties were rich in soluble sugars, which varied from 35.57 (Smiti variety) to 77.88 g/100 g fresh weight (FW) (Korkobbi variety). Several minerals were also present in the following order: K, Ca, P, Mg, Na, Fe, Cu, Zn, and Mn. The potassium content reached 0.74 g/100 g dry weight in Smiti variety. For all date varieties, the phenol content did not exceed 9.70 milligram of GAE/100 g FW). The original antioxidant activity reached 31.86 mg of ascorbic acid equivalent antioxidant capacity/100 g FW for Garn ghzal variety. However, it was only 17.77 for the Nefzaoui. |

| Iran[28] | Ten date varieties (Khenizi, Sayer, Lasht, Kabkab, Maktoub, Gentar Shahabi, Majoul, Khazui, and Zahedi) | Among 10 different varieties, Khenizi showed the highest antioxidant activity with the FRAP value of 3279.48 μmol/100 g of the dry plant and DPPH inhibitory percentage of 56.61%. DPPH scavenging radical and FRAP values of some varieties including Khenizi, Sayer, Shahabi, and Maktub showed a significant increase and were comparable to α-tocopherol (10 mg/L). Shahabi variety with 276.85 mg GAE/100 g of the dry plant showed the highest total phenolic content compared to other varieties. There was no correlation between the accumulation of total phenol and antioxidant activity of extracts, explaining the existence of other antioxidant components in date fruits. |

| Saudi Arabia[29] | Three varieties (Khalas, Sukkari, and Ajwa) | Water extract has shown significantly higher contents of total phenols than alcoholic extract, especially in Ajwa (455.88 and 245.66 mg/100 g, respectively). However, phenolic profile indicated that Sukkari contained the highest rutin concentration (8.10 mg/kg), whereas catechin was approximately the same in Sukkari and Ajwa (7.50 and 7.30 mg/kg, respectively). Khalas was the variety with highest content of caffeic acid (7.40 mg/kg). A significant difference was indicated among extracts and varieties in suppressing lipid peroxidation. Sukkari and Ajwa have reduced the oxidation with 50% at lower concentration in water extract than alcoholic extract (0.63, 0.70 and 1.60, 1.43 mg/mL, respectively). Furthermore, high positive linear correlation was found between total phenols in water (r = 0.96) and alcohol (r = 0.85) extracts and inhibition of lipid oxidation activity. The compounds responsible for the activity were catechin (r = 0.96), and rutin (r = 0.74) in water extract, whereas this correlation decreased in alcoholic extract (r = 0.66) for catechin and very weak (r = 0.38) for rutin. No correlation was found between caffeic acid and lipid peroxidation in both extracts. Similar significant results were obtained with DPPH test, except with Sukkari, which showed no difference between aqueous and alcoholic extracts (4.30 and 4.10 mg/mL, respectively). |

| UK[30] | Date syrup from commercially available Khadrawi cultivar | DS has a high content of total polyphenols (605 mg/100 g) and is rich in tannins (357 mg/100 g), flavonoids (40.5 mg/100 g), and flavanols (31.7 mg/100 g), which are known potent antioxidants. Furthermore, DS and polyphenols extracted from DS, the most abundant bioactive constituent of DS, are bacteriostatic to both gram-positive and gram-negative E. coli and S. aureus, respectively. It has further been shown that the extracted polyphenols independently suppress the growth of bacteria at minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 30 and 20 mg/mL for E. coli and S. aureus, and have observed that DS behaves as a prooxidant by generating hydrogen peroxide that mediates bacterial growth inhibition as a result of oxidative stress. At sublethal MIC concentrations, DS showed antioxidative activity by reducing hydrogen peroxide, and at lethal concentrations, DS showed prooxidant activity that inhibited the growth of E. coli and S. aureus. The high sugar content naturally present in DS did not significantly contribute to this effect. |

| Algeria[31] | Five cultivars (Deglet Nour [DN], Degla Baidha [DB], Ghars [Gh], Tamjhourt [Tam], and Tafezauine [Taf]) | Total phenolic content ranged from 41.80 to 84.73 mg GAE/100 g and the total flavonoid content varied from 7.52 to 14.10 mg rutin equivalents (RE)/100 g. The antioxidant activities of methanolic extracts were evaluated in vitro using scavenging assays of DPPH radical, ABTS radical ion, and potassium ferricyanide complex as reducing power assay. Effective scavenging concentration (IC50) on DPPH radical ranged from 10.83 to 21.27 mg/L, the IC50 values decreased in the order DN > Tam > DB > Taf. ABTS radical cation scavenging activity (trolox equivalent 1.66–3.35 mM), the trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity values decreased in the order DN > Gh > DB > Tam > Taf. In the potassium ferricyanide complex assay, the antioxidant capacity of the extracts ranged between 2.06 and 4.21 mM ascorbic acid equivalents and the ascorbic acid equivalents antioxidant capacity values of the extracts decreased in the order Gh > Tam > DB > DN > Taf. |

| Tunisia[32] | Five cultivars (Beidh Hmam, Degla, Khalt Ahmar, Rtob, and Rtob Hodh) at different stages of ripening (Besser, Rutab, and Tamr). | Results showed that the content of these phytochemicals are very important at Besser stage and then decreased as the fruit ripening progressed, followed by a decrease in the antioxidant and the antibacterial activities. The analysis of the phenolic profile revealed the presence of 13 compounds. Caffeic, ferulic, and p-coumaric were detected as the major acids especially at Besser stage. |

| Egypt[33] | Commercially available ripe (Tamr) date variety | Water extract of Tamr stage date variety showed a higher content (14.80 mg GAE/g sample) of phenolic compounds than ethanol extract (10.31 mg GAE/g sample). High-performance liquid chromatography analysis showed the extracts contain high concentration of esculetin (15.11 and 17.30 mg/100 g) and tannic acid (2.85 and 1.79 mg/100 g). On the other hand, protocatechuic acid, catechol, pyrogallol, and cinnamic acid were not detected in both extracts. Moderate concentrations of gallic acid (7.51 and 5.28 mg/100 g), itaconic acid (6.40 and 5.91 mg/100 g), and traces of ferulic acid (0.15 and 0.22 mg/100 g) were detected. DPPH assay revealed a good antioxidant capacity of water extract, which was higher than that of ethanol extract. Antimicrobial data exhibited an impressive antibacterial activity for date extract. Date extract showed a strong antibacterial activity (for water and ethanol extracts) against E. coli (20 ± 0.57 and 16 ± 0.57 mm), Salmonella enterica (20 ± 0.54 and 14 ± 0.52 mm), and B. subtilis (18 ± 0.32 and 15 ± 0.23 mm) and moderate inhibition against S. aureus (8 ± 0.48 and 5 ± 0.52 mm) and Enterococcus faecalis (5 ± 0.36 and 2 ± 0.57 mm). |

| Tunisia[34] | Three cultivars (Deglet Nour, Allig, and Bejo) at full ripeness (Tamr stage) | The results revealed that second-grade dates reported three benzoic acids, five cinnamic acids, and two flavonoids, with the predominance of q-coumaric acid (1998.80 μg/100 g). The antimicrobial activities showed that the date extracts were active against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, showing marked activity against E. coli with an inhibition zone of 25 mm. Cytotoxicity assays showed that the date extracts were able to inhibit the proliferation of HeLa cell lines. |

AA = antioxidant activities; CAE = catechin equivalents; CTC = condensed tannins content; DS = date syrup; DW = dry weight; ORAC = oxygen radical absorbance capacity; TAC = total anthocyanin content; TE = trolox equivalents; TEAC = trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity; TFC = total flavonoid content; TPC = total phenolic content

In Mauritania, date fruits are considered an important source of nutrition, with over 2.6 million date palm trees producing some 58,000 tons of dates annually. Thus, the antioxidant contents and activities of six date palm cultivars (Ahmar dli, Ahmar denga, Bou seker, Tenterguel, Lemdina, and Tijib) at two edible stages of development—ripening (Blah) and fully ripe (Tamr)—were investigated by Mohamed Lemine et al. (2014).[16] The results showed that polyphenols and flavonoids were higher in the Blah stage compared to those in the fully mature Tamr stage from all cultivars, with average total phenolics at the Blah and Tamr stages being 728.5 and 558.9 mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE)/100 g of dry matter, respectively, and average flavonoid content of 119.6 and 67.3 mg quercetin equivalents/100 g of dry matter, respectively. The Blah stage also had the highest total antioxidant activity, followed by Tijib, and a higher positive correlation was observed for total phenolics in both Tamr and Blah stages and antioxidant activities, compared to the flavonoids.[16]

Using Saudi date fruit varieties (Al Sagey, Helwat Al Jouf, and Al Sour), Hamad[21] showed that these varieties possessed potent antioxidant capacities, mostly as a result of their phenolic (caffeic acid, ferulic acid, protocatechuic acid, catechin, gallic acid, p-coumaric acid, resorcinol, chlorogenic acid, and syringic acid) and flavonoid (quercetin, luteolin, apigenin, isoquercitrin, and rutin) contents. Al Sagey cultivar possessed the strongest antioxidant capacities and the highest phenolic contents. Similarly, Al Sagey and Helwat Al Jouf showed comparable glutathione and ascorbate redox status, whereas Al Sour showed the least glutathione redox status.[21] In another study from Saudi Arabia, date fruits (ripe Tamr stage) commercially purchased from a market in Madinah were shown to have significant antibacterial activity against imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa as a result of its rich flavonoid glycoside content including quercetin, luteolin, and apigenin.[3] Again, Al-daihan and Bhat[23] showed that the fruit of the Mosaifah cultivar from Saudi Arabia had stronger antibacterial activity compared to the leaf, seed, and bark, against select pathogenic bacteria including S. aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa. The antibacterial activity of the fruit was correlated with its rich antioxidant contents including alkaloids, flavonoids, and tannins.

Awad et al.[25] studied five cultivars (Helali, Medjool, Lonet-Mesaed, Khenazi, and Barhee) during different stages of ripening from Saudi Arabia. The antioxidant capacity, antioxidant compounds, and antioxidant enzyme activities in the date fruit were studied in the 2009 and 2010 seasons. Both the antioxidant capacity measured by the DPPH method and the antioxidant compound (phenols, tannins, and vitamin C) concentrations decreased with increasing fruit maturation, whereas the antioxidant capacity positively correlated with the concentration of antioxidant compounds. However, the activities of the antioxidant enzymes, peroxidase, catalase, and polyphenol oxidase, increased through the maturation process but later decreased at the final ripening stages. Another study using three premium quality date varieties (Khalas, Sukkari, and Ajwa) from Saudi Arabia evaluated the antioxidant content of their water extract, the results of which showed high contents of total phenols especially in Ajwa, although Sukkari had the highest rutin concentration, whereas catechin was similar in Sukkari and Ajwa. Khalas had the highest content of caffeic acid. These date varieties all suppressed lipid peroxidation with a high positive linear correlation with total phenols, catechin, and rutin.[29]

Six date varieties (Barakawi, Gondaila, Jaw, Mishrig, Bittamoda, and Madini) from Sudan were tested by Mohamed et al.[17] In Sudan, date fruits are believed to have been cultivated for more than 3000 years. The results showed that these date varieties contained high amounts of total polyphenol, total flavonoids, and antioxidant activities. Bittamoda, and Madini had the highest total phenols, whereas Bittamoda and Gondaila had the highest total flavonoids.

In Algeria, where date palm (P. dactylifera L.) fruits are widely consumed, Ali Haimoud et al.[18] used seven date fruit varieties (Tantebouchte, Biraya, Degla Baidha, Deglet Nour, Ali Ourached, Ghars, and Tansine) to test the antioxidant properties. The results showed that all varieties had high polyphenol, flavonoid, and flavonol contents, although the methanolic extract of Ali Ourached cultivar had the highest antioxidant activity. They also studied the anti-inflammatory effects of these varieties, the results of which showed significant attenuation of inflammation by these varieties. Ten Algerian cultivars (Mech Degla, Deglet Ziane, Deglet Nour, Thouri, Sebt Mira, Ghazi, Degla Beida, Arechti, Halwa, and Itima) were also analyzed by Benmeddour et al.[26] who found that the varieties had potent antioxidant potentials. Ghazi, Arechti, and Sebt Mira had the most potent antioxidant capacities and the highest phenolic contents. Gallic, ferulic, coumaric, and caffeic acids were found to be the main phenolics present, whereas isoquercitrin, quercitrin, rutin, quercetin, and luteolin were the main flavonoids. In addition, five Algerian cultivars (Deglet Nour, Degla Baidha, Ghars, Tamjhourt, and Tafezauine) were analyzed by Zineb et al.,[31] who reported that total phenolics, total flavonoids, and antioxidant activities were high based on the scavenging assays of DPPH radical, 2,20-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate) (ABTS), and potassium ferricyanide complex as reducing power assay.

In another study, three Tunisian cultivars (Allig, Bejo, and Deglet Nour) were evaluated for their antioxidant potentials. The results showed that the fruits of these cultivars had strong antioxidant activities and contents, with Allig being the highest followed by Bejo and Deglet Nour. Similarly, the antioxidant activities of these date cultivars correlated positively with their total phenolic and flavonoid contents. By using in vitro antioxidant assays (DPPH radical scavenging activity, ferric-reducing antioxidant power [FRAP] assay, H2O2 scavenging activity, and metal chelating activity), the fruit varieties were found to contain high activities: Allig > Bejo > Deglet Nour, with strong correlation between antioxidant activities and phenolic and flavonoid contents.[24] Four cultivars (Gondi, Gasbi, Khalt Dhahbi, and Rtob Ahmar) of Tunisian date fruits at three maturation stages, mature firm (Besser or Khalal), half-ripe (Rutab), and ripe (Tamr), were analyzed for their antioxidant contents and activities, the results of which showed the highest antioxidant contents and activities at the Besser stage, which were significantly correlated. Sixteen phenolic compounds were identified with caffeic, ferulic, protocatechuic, and catechin being the major ones.[35] Chaira et al.[27] also showed that Tunisian dates had high antioxidant potentials. They studied 10 Tunisian date varieties (Smiti, Kenta, Bekrari, Mermella, Garn ghzal, Nefzaoui, Baht, Korkobbi, Bouhattam, and Rotbi) and reported high antioxidant activity for all varieties. The phytochemical composition and phenolic profile changes as well as antioxidant and antibacterial properties of five date cultivars (Beidh Hmam, Degla, Khalt Ahmar, Rtob, and Rtob Hodh) at three distinct maturity stages (Besser, Rutab, and Tamr) were reported by Lotfi Achour et al.[32] The results showed that the antioxidant contents decreased with increasing fruit ripening, with a corresponding decrease in the antioxidant and the antibacterial activities. Caffeic, ferulic, and p-coumaric acids were the major acids detected, especially at Besser stage. Date extract also strongly inhibited bacterial food pathogens (E. coli, Salmonella typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, B. cereus, S. aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Listeria monocytogenes, and Enterococcus faecalis). Similarly in Tunisia, three cultivars (Deglet Nour, Allig, and Bejo) at full ripeness stage (Tamr) were studied by Kchaou et al.[34] The results showed the presence of benzoic acid, cinnamic acid, and flavonoids, and strong antimicrobial activities against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria but most potently against E. coli.

Furthermore, in Iran, 10 date varieties (Khenizi, Sayer, Lasht, Kabkab, Maktoub, Gentar, Shahabi, Majoul, Khazui, and Zahedi) were evaluated and Khenizi was found to have the highest antioxidant activity.[28] Al-Harrasi et al.[20] also showed that among 22 varieties of date fruits from Oman (Fardh, Helali Oman, Manhi, Qush Basrah, Handal, Naghal, Qushbu Maan, Qushbu Norenjah, Qush Balquan, Qush Jabri, Seedi, Khasab, Khunaizi, Barshi, Qush Mamoor, Barni, Azad, Zabad, Khalas, Qush Tabak, Qush Lulu, and Halali Alhasa), Khasab, Khalas, and Fardh had highest activities, although all varieties showed potent antioxidant activities (40%–86%) and rich nutritional contents. In Egypt, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of date fruits (Tamr stage) were evaluated with the results showing high antioxidant contents mostly as a result of esculetin, tannic acid, gallic acid, itaconic acid, and ferulic acid. Strong antibacterial activity against E. coli, Salmonella enterica, and B. subtilis and moderate inhibition against S. aureus and E. faecalis were also observed.[33] Six commercially available date cultivars in the US, Deglet Nour (Algeria), Deglet Nour (California), Deglet Nour (Tunisia), Shahia (Tunisia), Barni (Saudi Arabia), and Khudri (Saudi Arabia), were also reported to have high antioxidant contents and activities, with Deglet Nour from Algeria having the highest antioxidant properties.[19] Similar results were obtained when three commercially available date fruits (Deglet Nour, Khouat Allig, and Zahidi) were studied in the UK; the fruits were found to be nutrient rich with potent antioxidant capacities.[22] Another study from the UK used a commercially available cultivar (Khadrawi) to test for antimicrobial properties. The results showed that the date fruits were rich in polyphenols, tannins, flavonoids, and flavanols, which exerted potent bacteriostatic effects against gram-positive and gram-negative E. coli and S. aureus, respectively.[30] In Malaysia, the effects of chilling and storage on antibacterial properties and antioxidant capacities of Saudi Arabian cultivars (Mabroom, Safawi, and Ajwa) versus the Iranian cultivar (Mariami) were reported by Samad et al.[10] The results suggested that storage at 4°C and 20°C increased the anthocyanin contents of date fruits, whereas chilling for 8 weeks increased the phenolic content. They also showed antibacterial activity against S. aureus, B. cereus, Serratia marcescens, and E. coli.[10]

In aggregate, several studies have reported positive correlation between antioxidant activities of date fruits and antioxidant contents, whereas antimicrobial activities have been shown against common bacterial food pathogens and correlated with antioxidant contents. The data on antimicrobial activity are interesting because they show that the date fruits have potent inhibitory effects against important disease pathogens such as P. aeruginosa, which is an important nosocomial pathogen that is difficult to treat and can spread among hospital staff and patients with severe consequences.[3] Date fruits were also inhibitory toward pathogens that cause food poisoning meaning it could lower the burden of these diseases.[10,32,33,34] Similarly, studies have shown decreasing antioxidant contents and bioactivities including antimicrobial activity with increasing fruit ripening, which suggest that consumption of the fruit at its ripening stages may confer the most bioactivity,[32] although keeping the fruit at lower temperatures in a refrigerator or freezer may preserve and even potentiate the antioxidant content and bioactivity.[10] It is therefore possible that for commercially available date fruits in the UK and USA, which were found to have retained their antioxidant properties,[19,22] maintaining a cold chain during transportation and storage at sales points may in fact increase the health benefits of these fruits.

CONCLUSION

Date fruit is frequently consumed in many countries in the Middle East and North Africa and is used for various ethnomedical purposes. This review summarizes the antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of date fruits from different countries around the world. The review suggests that date fruits are a good source of natural antioxidants and may be used as a functional food in the management of oxidative stress–related and infectious diseases. These benefits are not restricted to date fruits from any region as shown by the positive data from different countries. Human lifestyle variations, especially in eating habits, caused remarkable metabolic disorders, resulting in the increased risk of numerous chronic metabolic diseases. Research studies on the beneficial properties of date palm fruits are abundant, and the reviewed ones are only a sample of big population. Those reviews showed that date palm fruits are a safe, natural alternative and complementary treatment comparable with synthetic drugs to combat many disease conditions. The benefit ought to go farther than that to be incorporated as food ingredients to develop novel products. Further studies are also merited to offer details on the functional properties of date palm fruit components to evaluate their values as a functional food ingredient. In addition to its traditional and medicinal uses, the exploration of the prospective use of date palm fruits in food and pharmaceutical applications is needed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tengberg M. Beginnings and early history of date palm garden cultivation in the Middle East. J Arid Enviro. 2012;86:139–47. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghnimi S, Umer S, Karim A, Kamal-Eldin A. Date fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.): an underutilized food seeking industrial valorization. NFS J. 2017;6:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selim S, El Alfy S, Al-Ruwaili M, Abdo A, Al Jaouni S. Susceptibility of imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa to flavonoid glycosides of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) tamar growing in Al Madinah, Saudi Arabia. African J Biotechnol. 2012;11:416–22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shomer I, Borochov-Neori H, Luzki B, Merin U. Morphological, structural and membrane changes in frozen tissues of Madjhoul date (Phoenix dactylifera L.) fruits. Postharvest Biol Technol. 1998;14:207–15. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baliga MS, Baliga BRV, Kandathil SM, Bhat HP, Vayalil PK. A review of the chemistry and pharmacology of the date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Food Res Int. 2011;44:1812–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan H, Khan SA, June M, June M. Date palm revisited. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci. 2016;7:2010–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong YJ, Tomas-Barberan FA, Kader AA, Mitchell AE. The flavonoid glycosides and procyanidin composition of Deglet Nour dates (Phoenix dactylifera) J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:2405–11. doi: 10.1021/jf0581776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juices F. National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release Legacy April, 2018 Full Report (All Nutrients) 09087, Dates, United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, USDA Food Composition Databases. Deglet Nour a. 2018:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taleb H, Maddocks SE, Morris RK, Kanekanian AD. Chemical characterisation and the anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic and antibacterial properties of date fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.) J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;194:457–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samad MA, Hashim SH, Simarani K, Yaacob JS. Antibacterial properties and effects of fruit chilling and extract storage on antioxidant activity, total phenolic and anthocyanin content of four date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) cultivars. Molecules. 2016;21:419. doi: 10.3390/molecules21040419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mutlak HH, Mann J. Darkening of dates: control by microwave heating. Date Palm J. 1984;3:303–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maier VP, Metzler DM. Changes in individual date polyphenols and their relation to browning. J Food Sci. 1965;30:747–52. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maier VP, Metzler DM. Quantitative changes in date polyphenols and their relation to browning. J Food Sci. 1965;30:80–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macheix JJ, Fleuriet A, Billot J. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 1990. Fruit phenolics. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouhlali E dine T, Bammou M, Sellam K, Benlyas M, Alem C, Filali-Zegzouti Y. Evaluation of antioxidant, antihemolytic and antibacterial potential of six Moroccan date fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.) varieties. J King Saud Univ–Sci. 2016;28:136–42. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohamed Lemine FM, Mohamed Ahmed MV, Ben Mohamed Maoulainine L, Bouna Zel AO, Samb A, O Boukhary AOMS. Antioxidant activity of various Mauritanian date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) fruits at two edible ripening stages. Food Sci Nutr. 2014;2:700–5. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohamed RM, Fageer AS, Eltayeb MM, Mohamed Ahmed IA. Chemical composition, antioxidant capacity, and mineral extractability of Sudanese date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) fruits. Food Sci Nutr. 2014;2:478–89. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ali Haimoud S, Allem R, Merouane A. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of widely consumed date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) fruit varieties in Algerian Oases. J Food Biochem. 2016;40:463–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Jasass FM, Siddiq M, Sogi DS. Antioxidants activity and color evaluation of date fruit of selected cultivars commercially available in the United States. Adv Chem. 2015;2015:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Harrasi A, Rehman NU, Hussain J, Khan AL, Al-Rawahi A, Gilani SA, et al. Nutritional assessment and antioxidant analysis of 22 date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) varieties growing in Sultanate of Oman. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7S1:S591–8. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60294-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamad I. Phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of Saudi date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) fruit of various cultivars. Life Sci J. 2014;11:1268–71. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mistrello J, Sirisena SD, Ghavamic A, Marshalld RJ, Krishnamoorthy S. Determination of the antioxidant capacity, total phenolic and flavonoid contents of seeds from three commercial varieties of culinary dates. Int J Food Stud. 2014;3:34–44. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-daihan S, Bhat RS. Antibacterial activities of extracts of leaf, fruit, seed and bark of Phoenix dactylifera. African J Biotechnol. 2012;11:10021–5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kchaou W, Abbès F, Attia H, Besbes S. In vitro antioxidant activities of three selected dates from Tunisia (Phoenix dactylifera L.) J Chem 2014. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Awad MA, Al-Qurashi AD, Mohamed SA. Antioxidant capacity, antioxidant compounds and antioxidant enzyme activities in five date cultivars during development and ripening. Sci Hortic. 2011;129:688–93. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benmeddour Z, Mehinagic E, Meurlay D Le, Louaileche H. Phenolic composition and antioxidant capacities of ten Algerian date (Phoenix dactylifera L.) cultivars: a comparative study. J Funct Foods. 2013;5:346–54. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaira N, Mrabet A, Ferchichi A. Evaluation of antioxidant activity, phenolics, sugar and mineral contents in date palm fruits. J Food Biochem. 2009;33:390–403. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khanavi M, Saghari Z, Mohammadirad A, Khademi R, Hadjiakhoondi A, Abdollahi M. Comparison of antioxidant activity and total phenols of some date varieties. DARU: J Pharmac Sci. 2009;1:104–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saleh EA, Tawfik MS, Abu-Tarboush HM. Phenolic contents and antioxidant activity of various date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) fruits from Saudi Arabia. Food Nutr Sci. 2011;02:1134–41. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taleb H, Maddocks SE, Morris RK, Kanekanian AD. The antibacterial activity of date syrup polyphenols against S. aureus and E. coli. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:198. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zineb G, Boukouada M, Djeridane A, Saidi M, Yousfi M. Screening of antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of various date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) fruits from Algeria. Med J Nutrition Metab. 2012;5:119–26. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lotfi Achour P, El Arem A, Behija Saafi E, Ben Slama R, Zayen N, Hammami M, et al. Phytochemical composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of common date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) fruit during three maturation stages. Tunis J Med Plants Nat Prod. 2013;10:33–48. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sohaimy SA El, Abdelwahab AE, Brennan CS. Phenolic content, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Egyptian date palm fruits. Australian J Basic Appl Sci. 2015;9:141–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kchaou W, Abbès F, Mansour RB, Blecker C, Attia H, Besbes S. Phenolic profile, antibacterial and cytotoxic properties of second grade date extract from Tunisian cultivars (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Food Chem. 2016;194:1048–55. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.08.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amira el A, Behija SE, Beligh M, Lamia L, Manel I, Mohamed H, et al. Effects of the ripening stage on phenolic profile, phytochemical composition and antioxidant activity of date palm fruit. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:10896–902. doi: 10.1021/jf302602v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]