Abstract

Background: Leaders are needed to address healthcare changes essential for implementation of integrated primary care. What kind of leadership this needs, which professionals should fulfil this role and how these leaders can be supported remains unclear.

Objectives: To review the literature on the effectiveness of programmes to support leadership, the relationship between clinical leadership and integrated primary care, and important leadership skills for integrated primary care practice.

Methods: We systematically searched PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO until June 2018 for empirical studies situated in an integrated primarycare setting, regarding clinical leadership, leadership skills, support programmes and integrated-care models. Two researchers independently selected relevant studies and critically appraised studies on methodological quality, summarized data and mapped qualitative data on leadership skills.

Results: Of the 3207 articles identified, 56 were selected based on abstract and title, from which 20 met the inclusion criteria. Selected papers were of mediocre quality. Two non-controlled studies suggested that leadership support programmes helped prepare and guide leaders and positively contributed to implementation of integrated primary care. There was little support that leaders positively influence implementation of integrated care. Leaders’ relational and organizational skills as well as process-management and change-management skills were considered important to improve care integration. Physicians seemed to be the most adequate leaders.

Conclusion: Good quality research on clinical leadership in integrated primary care is scarce. More profound knowledge is needed about leadership skills, required for integrated-care implementation, and leadership support aimed at developing these skills.

Keywords: General practice/family medicine, general, integrated care, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, skills training

KEYMESSAGES

Research to build a stronger evidence base for leadership and supportive leadership interventions is urgently needed to warrant the current emphasis on leadership in integrated primary care.

Evidence on essential leadership skills adds that physicians require relational and organizational skills, as well as process-management and change-management skills.

Introduction

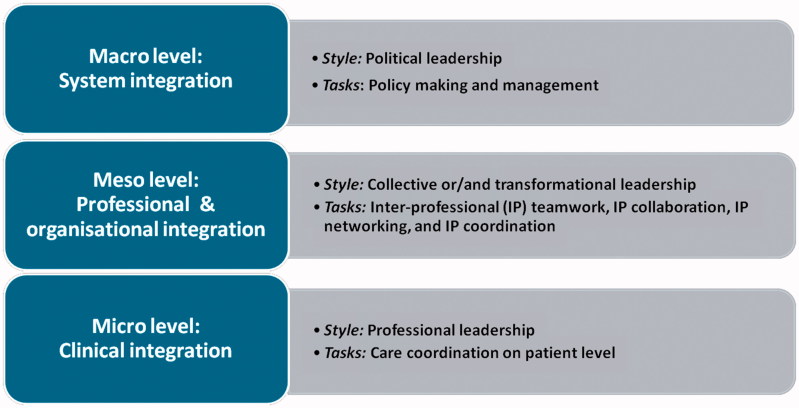

As numbers of chronically ill patients with complex healthcare needs are increasing, primary care professionals will be challenged to deliver integrated care. Integrated care is about ‘delivering seamless care for patients with complex long-term problems cutting across multiple services, providers and settings’ ([1], p. 58). It covers care processes that take place on the micro (clinical integration), meso- (professional and organizational integration) and macro (system integration) level (Figure 1) [2], and requires interprofessional care including teamwork, collaboration, coordination and networking [3]. Consequently, implementation of integrated care is a complex and sometimes even chaotic process, requiring a fundamental redesign of usual primary care [4,5].

Figure 1.

The three different levels of care integration and their leadership styles and tasks.

Leadership is considered a prerequisite for integrated primary care [6–9] to give direction and align within organizations and interprofessional teams [10,11]. Worldwide, physician leadership is endorsed to foster collaboration with colleagues interprofessionally [9,12]. Therefore, physician leadership should exceed leading multidisciplinary meetings. It is also about the ability to change the care process, e.g. defining new roles for different professionals, handling different interests and implementing patient care coordination.

A review of studies in the hospital setting recently showed that nursing leadership might lead to higher patient satisfaction, lower patient mortality, fewer medication errors and fewer hospital-acquired infections [13]. Within the Chronic Care Model, the most accepted integrated-care model, leadership is recommended to enlarge the effectiveness of integrated care [14]. However, lack of leadership power is often reported in integrated-care studies [7,8] and few studies support the assertion that leadership advances integrated care [15].

Because of the diversity in autonomous professionals and the differences in care arrangements, experiences and views of professionals in primary care [16], it is plausible that leadership aimed at primary care integration requires specific leadership styles and skills (See Box 1 and Figure 1 for leadership styles and tasks) [17].

BOX 1.

Leadership styles related to integrated care

Two important leadership styles can be distinguished in relation to integrated care:

collective leadership (e.g. shared, collaborative, dispersed, distributed or team leadership) that involves the collective influence of team members and is based on social interactions [18].

transformational leadership, a more hierarchical style, where leaders transform their followers by charisma and motivate them to achieve more than what is expected and challenge them to look beyond self-interest [19].

A recent scoping review identified collective leadership as the most important style to facilitate interprofessional care, although it remained unclear how this style was applied. Only a few studies described leadership skills needed for collaboration with colleagues with different professional or organizational backgrounds [20].

Several preparation and support programmes exist to develop leadership skills among healthcare professionals [20]. Most of these programmes target physicians and nurses (clinical leadership) in hospital settings [15], and only few address care integration [21]. Despite the broadly shared idea that leadership is essential for the delivery of integrated care, the nature and strength of the association between leadership and integrated primary care practice remains unclear [20]. In a review of the literature, we therefore, aimed to primarily study the effectiveness of leadership preparation and support programmes on integrated primary care practice. Furthermore, we explored the association between clinical leadership and integrated primary care practice and outcomes and skills required for effective clinical leadership in an integrated primary care context.

Methods

Search strategy

We performed a systematic review according to the PRISMA recommendations [22] (Prospero CRD42016036746). We searched the electronic databases of PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO up to 30 June 2018, including relevant synonyms for (1) Leadership AND (2) Integrated Care, namely ‘Chronic Care Model,’ ‘coordinated healthcare,’ ‘integrated health service,’ ‘collaborative healthcare,’ ‘interprofessional collaboration,’ ‘interprofessional cooperation,’ ‘inter organizational collaboration’ and ‘inter organizational cooperation,’ without restrictions regarding language or year of publication. Additionally, we performed the snowball method and manually searched systematic reviews on implementation of integrated care (Supplemental Material, available online).

Inclusion criteria

For inclusion, articles had to (1) describe empirical research with quantitative and/or qualitative data collection, full text available; (2) address clinical leadership in an integrated primary care setting or collaboration between primary and hospital care; (3) focus on the effectiveness of leadership support and training, on required leadership skills and/or the association between leadership and integrated primary care practice; and (4) focus on the meso-level of integrated care (Figure 1).

Excluded were reviews, opinion papers, papers on health policy, papers solely situated within the hospital setting, and papers that report on clinical interventions with the focus on process indicators. We excluded studies on integrated care defined as public health programmes, oral health, telehealth, disease management, care pathways, educational programmes, and studies with the following perspectives: non-clinical leadership (management, governance, political, church, military, civic and lay leaders) and care integration not exceeding the micro level (care coordination).

Selection of papers, critical appraisal and data extraction

After exclusion of duplicates, a first selection was made based on article titles by one reviewer (MN); then, abstracts were independently screened by two researchers (MP, MN). The relevant articles were read full-text and assessed for inclusion. In case of disagreement, discussion led to consensus or a third researcher was consulted (MvdM). To determine the level of agreement, Cohen’s к was calculated.

Subsequently, the studies included were appraised independently on methodological quality by two researchers (MP, MN). We used the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) as this tool allows concomitant appraisal of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies [23]. MMAT scores represent the number of criteria met, divided by four and translated in percentages; scoring varies from 25% (noted as *, low quality) to 100% (noted as ****, high quality), with scores in between noted as ** or *** of mediocre quality. Additionally, all qualitative studies were assessed using the COREQ criteria and these scores were integrated in MMAT scores [24].

Primarily, data extraction was targeted on the effectiveness of leadership support and training programmes as a structural component of the integrated primary care implementation strategy on all possible outcomes e.g. individual or organizational. Secondarily, data were collected on the association between clinical leadership and integrated primary care with outcomes on the patient level and leadership skills needed for effective implementation of integrated primary care. We extracted additional data on study characteristics such as publication date, country, integrated-care setting, target patient population, design, data collection and participants and leadership perspective/approach.

We performed a narrative synthesis on results for leadership skills by categorizing outcomes using the Bell framework on collaboration [25]. This framework consists of five different themes: (1) shared ambition; (2) mutual gains; (3) relationship dynamics; (4) organization dynamics; and (5) process management [17]. After categorizing the data in these themes, we defined subthemes.

Results

Study characteristics

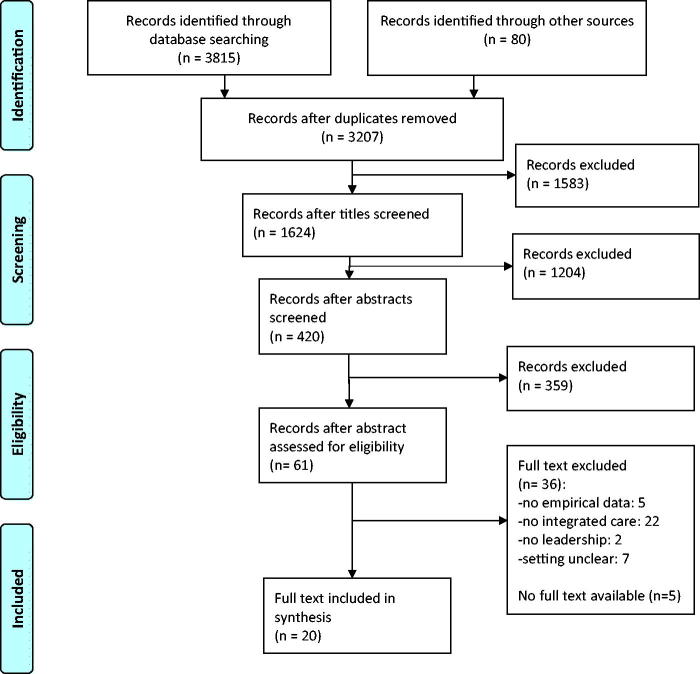

From the 3207 citations identified, 61 abstracts were found eligible of which 56 full-text articles were available (Figure 2). The researchers initially agreed on 48 articles for inclusion or exclusion (к = 0.86), on seven articles consensus was reached after discussion and for one article a third researcher was consulted. Finally, 20 articles were included (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Diagram of information flow through phases of systematic review.

Table 1.

Overall characteristics of the papers included in order reference by year of publication.

| Reference, year, study quality | Country | Integrated-care setting (when specified target patient population) | Study design | Data collection | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [26] 2006*** | USA | Within primary care (depression care) | Qualitative | Telephone interview | 5 community-based healthcare organizations/29 participating practices, 91 participants |

| [27]2006* | Canada | Between primary care and hospital (oncology care) | Qualitative | Longitudinal case study; non-participating observation of meetings, semi-structured interviews, documentary analysis | Local, regional and supra-regional multidisciplinary teams; five hospitals, 65 clinician leaders, medical and nursing staff members and managers |

| [28] 2007* | UK | Within primary care | Mixed methods, largely qualitative | Questionnaires, open-ended interviews, one-to-one consultations, discussion, individual case-study report, individual feedback and group presentations | 6 district nurses/district nurse team leaders |

| [29] 2008** | Canada | Within primary care (palliative care) | Qualitative | Focus groups | 8 primary care teams |

| [30] 2009** | Australia | Between primary care, hospital and residential (aged) care | Mixed methods, largely qualitative | Multi-method case-study: journals, interviews, focus groups and surveys | 3 (student) nurse practitioners |

| [31] 2010*** | Canada | Between primary care (addiction rehabilitation) and hospital (psychiatric) | Qualitative | Case study: interviews, focus groups, non-participant observation and document analysis | 2 cases: 25 clinicians and administrators |

| [32] 2010** | France | Between primary care and hospital (community-dwelling elderly people with complex needs) | Qualitative | Interviews, observation, documents and focus groups | 56 stakeholders: primary care, community-based services, hospitals and funding agencies |

| [33] 2010*** | Canada | Within primary care | Qualitative | Exploratory case study and semi-structured interviews | 14 family health teams |

| [34] 2012** | The Netherlands | Within primary care and between primary care and hospital (COPD, diabetes cardiovascular, psychiatric diseases) | Quantitative, cross-sectional design | Questionnaires: | 22 disease-management partnerships |

| Partnership synergy and functioning (PSAT) | |||||

| Imp activeness disease-management partnership (ACIC) | 218 professionals | ||||

| [35] 2012** | UK | Within primary care (depression care) | Qualitative | Case study, in-depth interviews, documentary material | 20 managers and practitioners |

| [36] 2013*** | USA | Within primary care (diabetes, asthma) | Mixed methods | Qualitative: focus groups, clinical measures on diabetes and asthma and monthly practice implementation | Practice clinicians and managers of 76 practices; subsample of 12 practices for the focus group |

| Quantitative: leadership and practice engagement scores rated by external practice coach | |||||

| [37] 2014** | USA | Between primary care and hospital | Mixed method, largely qualitative | Internal evaluation: Monthly performance data on three levels: beginner, middle and expert level on practice operation, clinical process and outcomes, and patient experience | 9 collaborative practices involved, 260 000 patients, 450 professionals |

| External evaluation: to determine how well the collaboration achieves aims | |||||

| [38] 2014** | USA | Within primary care | Mixed methods | Qualitative: interviews | 22 practitioners from 5 pilots |

| Quantitative: web-based survey | 400 practitioners pilot and non-pilot | ||||

| [39] 2014*** | USA | Within primary care (depression care) | Mixed methods | Qualitative: site visits, observation, interviews, structured narratives | 42 practices from 14 medical groups |

| Quantitative: PHQ-9 scores, activation rates and remission rates of 1192 patients | |||||

| [40] 2015** | Australia | Within primary care (Aboriginals) | Qualitative | In-depth interview | 5 senior leaders |

| [41] 2015**** | Ireland | Within primary care | Qualitative | Semi-structured interview | 2 primary care teams, 19 team members |

| [42] 2015** | USA | Within primary care (depression care) | Mixed methods | Qualitative: observation of quality improvement team monthly meetings | 1 community health centre |

| Quantitative: chart reviews | 5044 adult patients | ||||

| [43] 2015**** | USA | Between primary care and hospital | Qualitative | Observation during site visits and interviews | 9 sites, 80 participants from 12 professions |

| [44] 2017** | Japan | Within community and primary care (elderly) | Qualitative | Semi-structured interview and observation | 26 medical professionals, including physicians, nurses, public health nurses, medical social workers and clerical personnel |

| [45] 2018*** | The Netherlands | Within primary care (elderly) | Qualitative | Focus groups and observation | 46 healthcare and social service professionals from four general practitioners practices |

= low quality, 25% on MMAT criteria.

= mediocre quality, 50% on MMAT criteria.

= mediocre quality, 75% on MMAT criteria.

= high quality, 100% on MMAT criteria.

MMAT, Mixed methods appraisal tool; ACIC, assessment of chronic illness care; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PHQ-9, patient health questionnaire-9; PSAT, partnership self-assessment tool.

Studies included were conducted in Western countries, most in the USA (n = 7) and Canada (n = 4). The majority of studies used a qualitative design (n = 12) or a mixed methods design (n = 7). Two studies obtained the maximum MMAT scores (****); 16 studies were of mediocre and two of low quality. Studies were all conducted after 2006. In 12 studies, integrated care was targeted for specific chronic care diseases, e.g. depression and diabetes or the elderly population. Integrated-care interventions ranged from collaborative working and interprofessional collaboration to full Chronic Care Model implementation, including case management, and multidisciplinary teams and consortium building [28,31–34,36,38,44,45].

Ten studies explicitly mentioned the use of clinical leadership perspective [26–28,31,32,39,42–45]. Five studies focused on collective leadership [30,35,36,38,41]. Three articles mentioned that different leadership styles were needed in different phases of integrated-care implementation [27,32,39]. Five papers did not describe the leadership style addressed [29,30,33,38,41].

Effectiveness of leadership interventions to improve integrated-care practice

We found no clinical trials on effectiveness of leadership interventions (support and preparation). Two studies, one mixed method study of mediocre quality [37] and one qualitative design of low quality [28], reported on the impact of a leadership intervention on integrated primary care practice. Bitton et al. investigated a leadership academy’s curriculum, including skill development and peer mentoring, that supported clinical leadership and change management [37]. Nineteen primary care practice teams, which consisted of clinical physician leaders, followed the leaderships academy’s curriculum during an 18-month period. The evaluation showed that clinical leadership behaviour improved (from 6.2 to 7.9, P <0.001, on the validated self-report patient centered medical home assessment, subscale ‘engaged clinical leadership;’ scores range from 0 (worst) to 12 (best)). Additional qualitative research findings suggested that leadership competencies must be augmented and learned at practice level to succeed in changing towards collaborative practice.

Alleyne et al. evaluated the clinical nursing leadership and action process model (CLINLAP), an approach to support firmly clinical (nursing) leadership [28]. This course included a two-day management-development workshop, group clinical supervision (90 min, weekly). Participants were additionally supported by a management development tool. In a qualitative evaluation, six district nurses stated that the CLINLAP model improved their capacity to enhance the quality of collaborative services provided to their patients, increased their confidence to perform and made implementing change more practical and manageable.

Association between clinical leadership and integrated primary care practice and outcomes

Thirteen studies explored the association between leadership and integrated primary care (Table 2). Three studies used a quantitative, cross-sectional correlation design (MMAT **/***), and 10 studies used a qualitative design (MMAT * to ****). All these studies reported a positive influence of leadership on the integration of primary care and provided in-depth information on the most fruitful leadership approaches clinical leadership [27,31] and different types of collective leadership: team leadership and dispersed leadership [30,35,38,41]. Two studies revealed the value of continuity of leadership in person for implementation of integrated primary care [26,42]. Five studies reported explicitly that physician leaders were the most suited professionals for practicing the clinical leadership role [33,38,43–45]. One study found a strong relationship (β = 0.25) between effectiveness of leadership and chronic care model integrated partnership [34]. Two studies showed a significant correlation between strong leadership and patient outcome measures, such as patients’ activation (r = 0.6) and the proportion of patients having nephropathy screening (OR: 1.37) [36,39].

Table 2.

Association between clinical leadership and integrated primary care and outcomes.

| Reference | Study design | Leadership perspective | Integrated-care outcomes: Clinical measures or practice changes towards care integration: Teamwork, IPP, collaborative care |

|---|---|---|---|

| [26] | Qualitative | Clinical leadership | Leadership and durability of leadership was clearly associated with success in sustaining and spreading the intervention |

| [27] | Qualitative | Clinical leadership | Clinical leaders succeeded in influencing professional practices. However, it is obvious that change does not depend solely on the clinical leaders’ role |

| Change leadership | |||

| [30] | Mixed methods, largely qualitative | Clinical leadership | Collaboration and leadership attributes were interrelated and contributed to the impact of the emerging NP role. Leadership supported the work of the team |

| [31] | Qualitative | Clinical leadership | Clinical leadership had determinative positive influence on integration process |

| [33] | Qualitative | Clinical leader | Critical role of physician leadership in supporting collaborative care |

| Change leadership | Essential role of a manager in supporting an sustaining collaborative care | ||

| [34] | Quantitative, cross-sectional | Overall leadership/senior leaders | Strong relationship (β = 0.25; P ≤ 0.01) between impact of disease management partnership (ACIC scores) and leadership (11 items on PSAT) |

| Practice team leadership | |||

| [35] | Qualitative | Leadership with focus on learning and knowledge management | Dispersed leadership approaches are the most appropriate for collaborative depression care |

| [36] | Mixed methods | Clinical leadership by practice leaders | Leadership was significantly associated with one clinical measure: the proportion of patients having nephropathy screening (OR: 1.37; 95%CI: 1.08–1.74) |

| The odds of making practice changes were greater for practices with higher leadership scores at any given time (OR: 2.41–4.20). Leadership rated monthly on a 0–3 scale during one year | |||

| [38] | Mixed methods | Clinical leadership | Local physician leader facilitated sense of teamwork |

| [39] | Mixed methods | Top leadership | Statistically significant and moderately strong positive correlations for patient activation and strong leadership support (0.63)/strong care manager (0.62)/strong primary care practice champion (0.60) |

| Primary care practice champion | |||

| Care manager | |||

| [41] | Qualitative | Clinical leadership | Lack of leadership was considered to be a barrier to more efficient outcomes |

| Formal leadership may not be fundamental to team working; team leadership would be advantageous | |||

| [42] | Mixed methods | Clinic QI leadership | Having onsite programme champions and durability of this leadership was important for implementation of collaborative care |

| [43] | Qualitative | Clinical leadership | IPP best practices emphasized role of physician leadership. Within historic hierarchy of medical care, physicians often are tone setting |

ACIC, assessment of chronic illness care; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; IPP, interprofessional practice; NP, nurse practitioner; PSAT, partnership self-assessment tool.

Leadership skills required for integrated primary care

Fourteen qualitative studies, one of high [43] and 13 of mediocre quality [26,29–33,35,36,38,40,42,44,45], described skills needed for integrated-care implementation and practice. Eleven studies reported skills related to relational dynamics such as encouraging team culture, facilitating interpersonal communication, fostering accountability and responsibilities of team members, positive role modelling and developing new professional roles [29,30,32,33,35,36,38,42–45]. Seven studies provided insight into organizational skills needed for clinical leaders: being visionary, decisive, being a catalyst and problem solving [26,30,31,36,40,43,45]. Process-management skills and change-management skills were reported in seven articles [26,29,31–33,36,45]. Two studies stated the need for leaders’ qualities to ensure the commitment of multidisciplinary team members to a shared purpose [32,35]. No skills required for Bell’s ‘mutual gains’ (understanding the various interests of the involved partners) category were mentioned (Table 3).

Table 3.

Leadership skills required for integrated primary care.

| Subthemes | Reference | Method for data collection | Leadership skills required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shared ambition (shared commitment of the involved partners) | |||

| Commitment | [32] | Interviews, observation, focus groups | Ensuring the broadening commitment of different health and social services |

| [35] | In-depth interviews | Helping to develop and negotiate shared purpose | |

| Relationship dynamics (relational capital among the partners) | |||

| Team culture | [29] | Focus groups | Shared leadership: team members empowering each other in their team |

| [30] | Case-study journals, interviews, focus group and surveys | Being able to function in a networked rather than a hierarchical manner | |

| [32] | Interviews, observation, focus groups | Maintain trusting relationships | |

| Establishing a collaborative culture: sensitivity to roles and contributions of different staff members | |||

| [35] | In-depth interviews | Encouraging working in groups and teams | |

| [36] | Focus groups | Fostering culture of teamwork | |

| Sensitivity to issues learning to ‘work together’ | |||

| [43] | Observation during site visits, interviews | Valuing contribution of team member | |

| Creating safe space for team members | |||

| [44] | Semi-structured interviews | Being able to consider the circumstances and ways of thinking of each discipline | |

| Interpersonal communication | [29] | Focus groups | Conflict resolution |

| Facilitate meetings | |||

| [43] | Observation during site visits, interviews | Communicating expectations of team member overtly or implicitly | |

| [44] | Semi-structured interviews | Promoting the creation of good communication and close interaction between disciplines | |

| Responsibilities | [29] | Focus groups | Foster accountability |

| Divide responsibilities for different tasks to different team members | |||

| [32] | Interviews, observation, focus groups | Clarifying dysfunctional areas and revising task distributions | |

| [42] | Observation of team monthly meetings | To champion protocol adherence | |

| Role modelling | [30] | Case-study journals, interviews, focus group and surveys | Positive professional role modelling, to share expertise |

| Developing transboundary role | |||

| [33] | Semi-structured interviews | Positive physician role modelling | |

| [45] | Focus groups, observation | Taking initiative to build multidisciplinary teams | |

| Emphasizing the role of professionals close to patients, especially nurses and social workers | |||

| Role developing | [32] | Interviews, observation, focus groups | Refining and legitimating the role of the case manager |

| [38] | Interviews, web-based survey | Providing confidence among individuals in adopting new roles | |

| Clarifying the scope of new role and responsibilities | |||

| Providing a vehicle for incorporating new roles into routine practice | |||

| Organization dynamics (governance arrangements among the partners) | |||

| Visionary | [26] | Telephone interviews | Visionary and committed |

| [36] | Focus groups | Vision about the importance of the work | |

| [43] | Observation during site visits, interviews | Vision on IPP, including patient- and family-centred care, high-quality care | |

| [45] | Focus groups, observation | Passionate about delivering integrated, good quality, person-centred care | |

| Decisiveness | [30] | Case-study journals, interviews, focus group and surveys | Evolving sense of authority |

| [31] | Interviews, focus groups, non-participant observation and document analysis | Having determinative influence | |

| Having clearly decisiveness to implement practice changes | |||

| Taking personal initiatives to set events in motion aimed at integrating healthcare resources | |||

| [40] | In-depth interviews | Display of determination to persevere when faced with challenges an barriers to change | |

| Persistence in facing resistance to change from staff | |||

| [45] | Focus groups and observation | Deciding on the composition of the multidisciplinary team | |

| Catalyst problem solving | [36] | Focus groups | Serve as link between top management and staff |

| [30] | Case-study journals, interviews, focus group and surveys | Taking positive action to resolve problems | |

| [40] | In-depth interviews | Overcome bureaucratic hurdles | |

| Process management (process steering among the partners) | |||

| Change management | [26] | Telephone interviews | Supporting improvement change culture, that permeates the organization |

| [29] | Focus groups | Should have knowledge of change theory | |

| [32] | Interviews, observation, focus groups | Transforming the classic hierarchical relationship between GPs and nurses/case managers | |

| [33] | Semi-structured interviews | Should encourage change | |

| Should be innovative, creative and possess project development and management skills | |||

| [36] | Focus groups | Test and implement innovations | |

| Project management | [29] | Focus groups | Public speaking, presentation skills, coaching skills, writing proposals and abstracts |

| [31] | Interviews, focus groups, non-participant observation and document analysis | To empower individuals to participate in transformation activities | |

| [32] | Interviews, observation, focus groups | Tailoring to the various phases of the diagnostic, design and implementation process | |

| [36] | Focus groups | Taking personal initiative to set events in motion aimed at integrating healthcare resources | |

| [45] | Focus groups, observation | Networking at the strategic level: connecting primary and secondary care, social services, and the community | |

GP, general practitioner; IPP, interprofessional practice; QI, quality improvement.

Bells Framework consists of [1] shared ambition, [2] mutual gains, [3] relationship dynamics, [4] organization dynamics and [5] process management.

Mutual gains was not mentioned.

Discussion

Main findings

In this systematic review, we found no controlled studies on the effectiveness of clinical leadership on integrated primary care practice and outcomes on patient level. Two articles suggested that leadership support programmes may contribute to preparing leaders for the implementation of integrated primary care. Leaders’ relational and organizational skills as well as process-management and change-management skills were considered important to improve care integration but were never tested. Physicians were appointed as the most adequate leaders. Most empirical studies included in the review were explorative by nature and of mediocre quality. The focus on leadership as a research target in relation to integrated care seems to be a new phenomenon as all studies selected were conducted after 2006.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this first systematic review covering the association between leadership and integrated primary care is that we performed a sensitive search with few limitations. However, we may still have missed potentially relevant articles because the underlying concepts of integrated care as well as leadership are not yet clearly defined. This also might have given rise to multiple interpretations during the selection process. To overcome this problem, the screening process was carried out by two researchers with at least ten years of experience in the field of integrated primary care. Moreover, they independently screened 420 abstracts and 56 full-text articles, with a high agreement rate.

Another limitation is that our search was limited to databases of clinical research when studying a management topic. Since this review focused on clinical leadership, we argue that we are probably able to identify the most relevant papers in the databases used. We tried to diminish this factor further by using snowball methods and manual searching of key articles on the implementation of integrated care including studies published in organizational science journals.

Comparison with existing literature

Effectiveness of leadership interventions. This review revealed that the use of leadership as the implementation strategy, although recommended in the Chronic Care Model and by many experts in the field, was hardly applied or described since we only found two studies of low and mediocre quality that evaluated leadership-training interventions aimed at structurally supporting implementation processes of integrated care. This shows that the importance of leadership to integrated primary care does not yet transcend the level of opinions.

Association between clinical leadership and integrated primary care. The association between leadership and integrated care is not substantiated with firm evidence [20]. This review appoints physicians as the professionals most capable of transforming care towards more integration. Until now, physicians have indeed been the principal players in either opposing or supporting successful transformative efforts [46]. Recognition of the need for physicians’ leadership role development and support and increased attention on clinicians’ collaboration and leadership skills were recently stipulated in physicians competency profiles (i.e. CANMED roles) [12,47]. Other professionals, e.g. nurses and social workers, may lack the hierarchical position in comparison with physicians and possibly need more support to perform their leadership role; skills to perform this role are not automatically present in professionals and the importance of supporting professionals in their leadership role is still underestimated [20].

Required leadership skills. Our review indicates that some relational leadership styles, especially collective leadership and team leadership, may be fruitful in the implementation of integrated primary care. Relational and organizational skills, as well as process-management and change-management skills, such as communicating expectations, maintaining trusting relationships and creating safe space, were also found important in other reviews [8,20]. Remarkably, the need for leaders to be able to understand mutual gains was not mentioned in the papers included. A possible explanation is that the ability to oversee the consequences of care integration for the organizations involved is complicated, as competitive dynamics may hinder crossing organizational borders [48].

Implications for research and/or practice

This review underlines the need for innovation in leadership research, training and practice. Furthermore, it shows that evaluating leadership in integrated primary care is challenging. Future research could benefit from better-defined concepts and a clear research agenda on leadership in the context of integrated primary care [20]. Leadership skills identified in this review can fuel the development of leadership programmes in vocational training curricula and interprofessional education. Evaluation of complex educational leadership interventions and the complex integrated primary care setting may ask for innovative research designs instead of classical randomized controlled trials. An example of such an innovative design is the longitudinal mixed methods case study to evaluate DementiaNet, an implementation programme for networked primary dementia care [49]. This design enabled a better understanding of the effects and working mechanisms. Outcomes in this study were network maturity and quality of care. These outcomes and their interrelatedness, combined with leadership skills assessment, are also relevant for the evaluation of clinical leadership programmes in the integrated primary care setting.

Conclusion

In the field of primary care, experts consider leadership to be a relevant factor for good-quality integrated care. However, this review revealed that there is no firm evidence for its positive impact. The evidence available is limited mainly to qualitative studies. Leadership support aimed at developing skills for integrated-care implementation is probably effective but a more profound evidence base is required. We therefore, advocate the development of higher-quality knowledge about leadership focused on the implementation of the integrated-care practice.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This research project was funded by Gieskes Strijbis fonds.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Goodwin N. Are networks the answer to achieving integrated care? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13:58–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valentijn PP, Schepman SM, Opheij W, et al. . Understanding integrated care: a comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. Int J Integr Care. 2013;13:e010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reeves S, Xyrichis A, Zwarenstein M. Teamwork, collaboration, coordination, and networking: why we need to distinguish between different types of interprofessional practice. J Interprof Care. 2018;32:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin C, Sturmberg J. Complex adaptive chronic care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al. . Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20:64–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans JM, Grudniewicz A, Baker GR, et al. . Organizational context and capabilities for integrating care: a framework for improvement. Int J Integr Care. 2016;16:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadu MK, Stolee P. Facilitators and barriers of implementing the chronic care model in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davy C, Bleasel J, Liu H, et al. . Factors influencing the implementation of chronic care models: a systematic literature review. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley-Patterson D. What kind of leadership does integrated care need? London J Prim Care (Abingdon). 2012;5:3–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West M, Armit K, Loewenthal L, et al. . Leadership and leadership development in healthcare: the evidence base. London: Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Husebø SE, Olsen ØE. Impact of clinical leadership in teams’ course on quality, efficiency, responsiveness and trust in the emergency department: study protocol of a trailing research study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dath DCM-K, Abbott C, CanMEDS 2015: from manager to leader. Ottawa, Canada: TRCoPaSo; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong CA, Cummings GG, Ducharme L. The relationship between nursing leadership and patient outcomes: a systematic review update. J Nurs Manag. 2013;21:709–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daly J, Jackson D, Mannix J, et al. . The importance of clinical leadership in the hospital setting. J Healthc Leadersh. 2014;6:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoen C, Osborn R, Huynh PT, et al. . On the front lines of care: primary care doctors’ office systems, experiences, and views in seven countries. Health Affair. 2006;25:w555–w571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valentijn PP, Vrijhoef HJ, Ruwaard D, et al. . Exploring the success of an integrated primary care partnership: a longitudinal study of collaboration processes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forsyth C, Mason B. Shared leadership and group identification in healthcare: the leadership beliefs of clinicians working in interprofessional teams. J Interprof Care. 2017;31:291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dionne SD, Gupta A, Sotak KL, et al. . A 25-year perspective on levels of analysis in leadership research. Leadership Quart. 2014;25:6–35. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brewer ML, Flavell HL, Trede F, et al. . A scoping review to understand “leadership” in interprofessional education and practice. J Interprof Care 2016;30:408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clausen C, Cummins K, Dionne K. Educational interventions to enhance competencies for interprofessional collaboration among nurse and physician managers: an integrative review. J Interprof Care. 2017;31:685–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Souto RQ, Khanassov V, Hong QN, et al. . Systematic mixed studies reviews: updating results on the reliability and efficiency of the mixed methods appraisal tool. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:500–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health C. 2007;19:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bell J, Kaats E, Opheij W. Bridging disciplines in alliances and networks: in search for solutions for the managerial relevance gap. IJSBA. 2013;3:50–68. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nutting PA, Gallagher KM, Riley K, et al. . Implementing a depression improvement intervention in five health care organizations: experience from the RESPECT-Depression trial. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34:127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Touati N, Roberge D, Denis J, et al. . Clinical leaders at the forefront of change in health-care systems: advantages and issues. Lessons learned from the evaluation of the implementation of an integrated oncological services network. Health Serv Manage Res. 2006;19:105–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alleyne J, Jumaa MO. Building the capacity for evidence-based clinical nursing leadership: the role of executive co-coaching and group clinical supervision for quality patient services. J Nurs Manag. 2007;15:230–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall P, Weaver L, Handfield-Jones R, et al. . Developing leadership in rural interprofessional palliative care teams. J Interprof Care. 2008;22:73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bail K, Arbon P, Eggert M, et al. . Potential scope and impact of a transboundary model of nurse practitioners in aged care. Aust J Prim Health. 2009;15:232–237. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brousselle A, Lamothe L, Sylvain C, et al. . Key enhancing factors for integrating services for patients with mental and substance use disorders. MH/SU. 2010;3:203–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Stampa M, Vedel I, Mauriat C, et al. . Diagnostic study, design and implementation of an integrated model of care in France: a bottom-up process with continuous leadership. Int J Integr Care. 2010;10:e034. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldman J, Meuser J, Rogers J, et al. . Interprofessional collaboration in family health teams: an Ontario-based study. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:e368–e374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. Disease-management partnership functioning, synergy and effectiveness in delivering chronic-illness care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24:279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams P. The role of leadership in learning and knowledge for integration. JICA. 2012;20:164–174. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donahue KE, Halladay JR, Wise A, et al. . Facilitators of transforming primary care: a look under the hood at practice leadership. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:S27–S33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bitton A, Ellner A, Pabo E, et al. . The Harvard medical school academic innovations collaborative: transforming primary care practice and education. Acad Med. 2014;89:1239–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grace SM, Rich J, Chin W, et al. . Flexible implementation and integration of new team members to support patient-centered care. Healthc (Amst). 2014;2:145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitebird RR, Solberg LI, Jaeckels NA, et al. . Effective implementation of collaborative care for depression: what is needed? Am J Manag C. 2014;20:699–707. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carroll V, Reeve C, Humphreys J, et al. . Re-orienting a remote acute care model towards a primary health care approach: key enablers. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15:2942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kennedy N, Armstrong C, Woodward O, et al. . Primary care team working in Ireland: a qualitative exploration of team members' experiences in a new primary care service. Health Soc Care Community. 2015;23:362–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Price-Haywood EG, Dunn-Lombard D, Harden-Barrios J, et al. . Collaborative depression care in a safety NET medical home: facilitators and barriers to quality improvement. Popul Health Manag. 2015;19:46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tubbesing G, Chen FM. Insights from exemplar practices on achieving organizational structures in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28:190–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asakawa T, Kawabata H, Kisa K, et al. . Establishing community-based integrated care for elderly patients through interprofessional teamwork: a qualitative analysis. JMDH. 2017;10:399–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grol SM, Molleman GRM, Kuijpers A, et al. . The role of the general practitioner in multidisciplinary teams: a qualitative study in elderly care. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Best A, Greenhalgh T, Lewis S, et al. . Large-system transformation in health care: a realist review. Milbank Q. 2012;90:421–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willcocks SG, Wibberley G. Exploring a shared leadership perspective for NHS doctors. Leadersh Health Serv. 2015;28:345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:759–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richters A, Nieuwboer MS, Olde Rikkert MGM, et al. . Longitudinal multiple case study on effectiveness of network-based dementia care towards more integration, quality of care, and collaboration in primary care. PloS One. 2018;13:e0198811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.