Abstract

There is scarce knowledge on early intestinal obstruction in Crohn’s disease (CD) after infliximab treatment. Therefore, we describe two cases of early intestinal obstruction in a series of 46 CD patients treated with infliximab. Both our two cases were 21-year-old men with newly diagnosed CD who were diagnosed with perianal disease 2 years previously. They were suffering from diarrhea and abdominal pain, but there were no symptoms indicating bowel obstruction. Radiographic studies revealed stenotic sites in the terminal ileum in both cases. In both cases, infliximab 300 mg was infused, after which their abnormal laboratory data as well as symptoms such as diarrhea and abdominal pain clearly improved. However, on the 11th or 13th day post-treatment, they presented abdominal distension with air-fluid levels on imaging studies. Ileocolonic resection was performed in both cases. Early intestinal obstruction after infliximab therapy is characterized by initial improvement of the symptoms and the laboratory data, which is soon followed by clinical deterioration. This outcome indicates that infliximab is so swiftly effective that the healing process tapers the stenotic site, resulting in bowel obstruction. Thus, although unpleasant and severe, the obstruction cannot be considered as a side effect but rather a consequence of infliximab’s efficacy. CD patients with intestinal stricture, particularly the penetrating type with stricture, should be well informed about the risk of developing intestinal obstruction after infliximab therapy and the eventual need for surgical intervention.

Keywords: Infliximab, Ileus, Crohn’s Disease

INTRODUCTION

Infliximab was the first monoclonal antibody biologic drug used to treat Crohn’s disease (CD), and it revolutionized therapeutic modalities for the disease. We consider inflammatory bowel disease to be a lifestyle disease mainly mediated by a westernized diet.1 In this regard, we developed a plant-based diet as a countermeasure against the westernized diet.1 We administered infliximab together with a plant-based diet as first-line (IPF) therapy on an inpatient basis in 46 CD patients (A1 below 16 y: 6; A2 between 17 and 40 y: 33; A3 above 40 y: 7; L1 Ileal: 1; L2 Colonic: 13; L3 Ileocolonic 32; B1 Nonstricturing/nonpenetrating: 33; B2 Stricturing: 12; B3 Penetrating: 1; p perianal disease modifier: 33).2 Our plant-based diet was a lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet with fish once a week and meat every other week.1 Plant-based diets prevent chronic diseases and bring longevity. Therefore, they are recommended to the public.2 All patients achieved clinical remission by week 6 after the first infliximab infusion, except for two patients who experienced obstruction within 2 weeks following the first infliximab infusion.2,3 Our protocol using infliximab2 brought early improvement compared to the administration of adalimumab.4 Mean Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) scores were 314, 163, and 115 at baseline and weeks 1 and 2, respectively, for the infliximab group.2 The scores for the adalimumab group were 313, 264, and 232, respectively.4

There have been brief statements or abstracts in the literature reporting early intestinal obstruction requiring surgical treatment after infliximab treatment in Crohn’s disease,5-7 but no precise reports are found.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

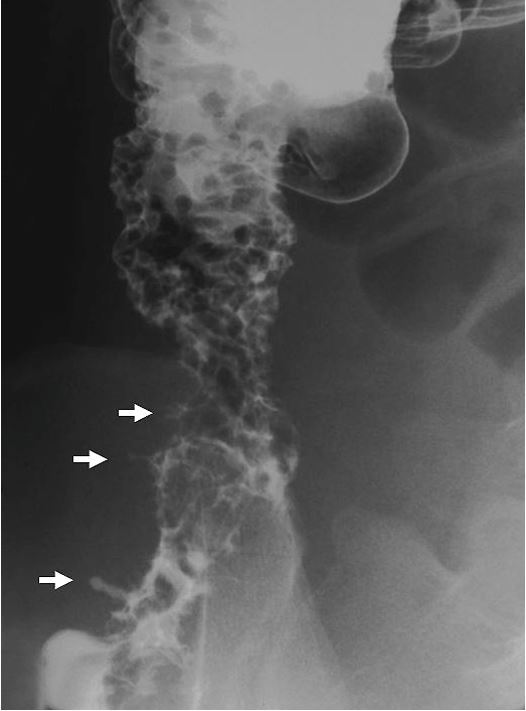

A 21-year-old man was referred because of a perirectal abscess followed by right lower quadrant abdominal pain and diarrhea. The initial diagnostic workup revealed the cobblestone appearance of the mucosa and fissurings in the right colon (Figure 1), leading to a diagnosis of CD. At that time, his BMI was 19.8 after losing 6 kg in the previous 7 months. Physical examination was non-contributory, except for anal skin tags and a perianal fistula scar. Laboratory data revealed abnormalities consistent with CD (Table 1). Plain film of the abdomen showed an isolated air-fluid level (Figure 2A), but he did not have symptoms indicating an intestinal obstruction. Therefore, routine examination and treatment for CD were performed.2

Figure 1. Double-contrast barium enema of the colon showing inflammation of the ascending colon and the cecum. The bowel is narrowed at the lower portion of the ascending colon. Cobblestone appearance is seen in the upper portion of the ascending colon. Fissurings are indicated by arrows.

Table 1. Change in laboratory data after infliximab (IFX) treatment.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Normal range | Before IFX | After IFX | Before IFX |

After IFX | |||

| 1 week | 13 days | 5 days | 11 days | |||||

| CRP | ≤0.3 mg/dL | 3.6 | 1.0 | 2.9 | 5.5 | 1.8 | 0.2 | |

| ESR | <15 mm/hr | 84 | 38 | 23 | 40 | 43 | 27 | |

| Hb | 13.8-17.5 g/dL | 12.2 | 12.3 | 12.5 | 7.9 | 8.6 | 8.8 | |

| WBC | 3900-8800/mm3 | 7700 | 7800 | 4900 | 6000 | 3400 | 3600 | |

| Platelets | 15.2-31.4x104/mm3 | 56.2 | 42.0 | 42.3 | 87.0 | 69.5 | 56.0 | |

| T. protein | 6.7-8.2 g/dL | 7.9 | 7.3 | 6.7 | 7.4 | 6.7 | 6.5 | |

| Albumin | 3.8-5.2 mg/dL | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.1 | |

| T. cholesterol | 110-220 mg/dL | 147 | 139 | 120 | 124 | 95 | 110 | |

| α2-globulin | 4.8-8.6% | 13.7 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 14.0 | 12.1 | 10.2 | |

| FOB | <200 ng/mL | 153 | n.a. | 211 | 154 | 28 | 820 | |

| CDAI | n.a. | 377 | 183 | 115 | ||||

CDAI = Crohn disease activity index; CRP = C-reactive protein; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FOB = fecal occult blood; Hb = hemoglobin; IFX = infliximab; n.a. = not available; T. cholesterol = Total cholesterol; T. protein = total protein; WBC = white blood cells.

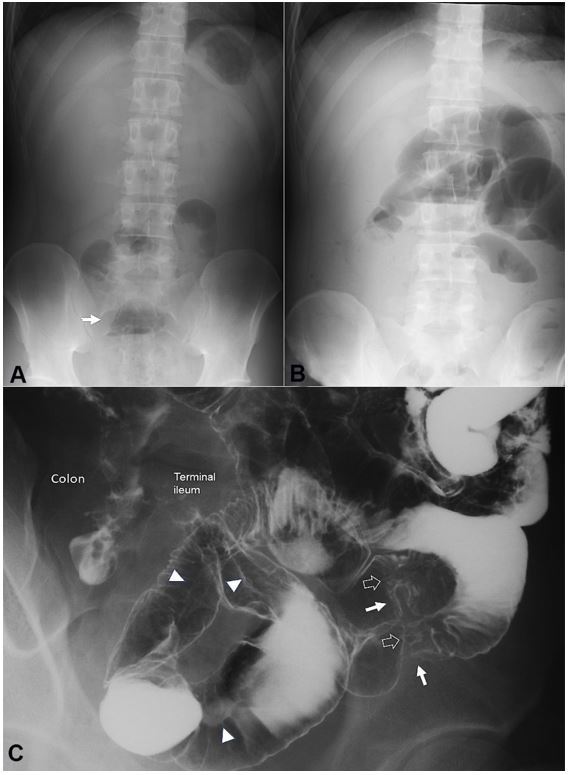

Figure 2. Plain abdominal radiographs on admission (A) and 13 days after the first infusion of infliximab (B). Solitary air-fluid level is indicated by an arrow (A). Multiple air-fluid levels are seen (B); C – Picture of the enteroclysis. Two stenotic portions are observed in the distal part of the ileum (white arrows). At the sites of stenosis, white soft shadows are seen (hollowed arrows) indicating active ulcers. Pre-stenotic dilatation is not observed. Longitudinal ulcers are observed (arrowheads).

The patient received liquid infusion without meals during morphological studies to assess clinical types and intestinal stenosis. Enteroclysis revealed stenotic portions and longitudinal ulcers in the distal portion of the ileum (Figure 2C). On the 8th hospital day, infliximab 300 mg (Remicade 5 mg/kg; Centocor, Malvern, PA, USA) was infused.8 A plant-based diet1,2 (1700 kcal/day) was initiated on the day after the infusion. Laboratory data 1 week after the infusion showed apparent improvement (Table 1), and the patient felt better after the 1st infusion of infliximab. However, on the 13th day, he presented abdominal distension after the first infusion. Intestinal obstruction was diagnosed due to clear air-fluid levels on plain abdominal radiographs (Figure 2B).

At this point, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was further improved, but C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration was elevated (Table 1). The 2nd infusion8 was cancelled, and the patient underwent ileocolonic resection 2 weeks later. Critical stenosis was found in the terminal ileum at 40 cm from the ileocecal valve. Perioperative endoscopy did not reveal another stenotic site proximally. The resected specimen showed round ulcers at the proximal site and a longitudinal ulcer of approximately 30 cm (Figure 3). The pathological findings were consistent with CD, namely, non-caseating epithelioid cell granulomas. A registered dietitian designed dietary guidance on a plant-based diet before discharge, and he was prescribed mesalazine, 2.25 g/day.

Figure 3. Gross examination of the resected specimen of case 1. Two round ulcers at the proximal site (arrowheads) and a longitudinal ulcer of 30 cm (arrows) are seen in the terminal ileum. Cobblestone appearance is seen in the ascending colon. The appendix (Ap) is swollen.

He was followed up every 8 weeks. Endoscopic remission was ascertained after 4 years of follow up, and medication was withdrawn 3 years later. The patient completed 13 years of follow-up, with normal laboratory tests, and no complications. His plant-based diet score,9 which evaluates adherence to the plant-based diet, was –2 before admission, followed by 38 and 20 out of 40 at 2 years and 9 years after discharge, respectively.

Case 2

A 21-year-old man was referred because of a long-lasting draining anal fistula, followed by diarrhea and abdominal pain. Colonoscopy revealed skipped lesions in the colon and longitudinal ulcers in the sigmoid. Non-caseating epithelioid cell granuloma was found in the biopsy specimen. Barium enema study revealed shortening of the right colon, stenotic sites, fistulas in the terminal ileum (Figure 4), and a diffuse coarse mucosa from the sigmoid to the distal part of the descending colon (Figure 4A). He was diagnosed as having CD. After losing 10 kg over the last 4 months, his BMI was 18.9. The physical examination was unremarkable, except for an anal fistula. Laboratory data revealed an elevated CRP concentration, marked anemia, and moderate hypoalbuminemia (Table 1). Plain film of the abdomen was unremarkable, however, enteroclysis revealed entero-enteric fistulas and stenotic sites in the distal ileum (Figure 4B). On the 5th hospitalization day, 300 mg of infliximab was infused.

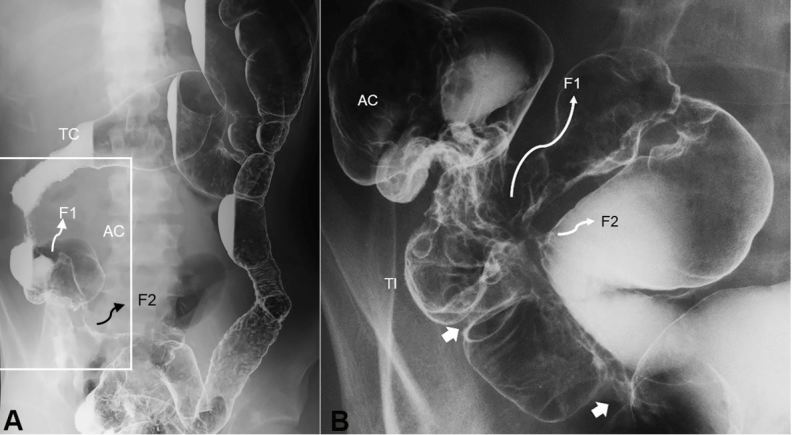

Figure 4. Double-contrast barium enema study. Entire picture of the colon (A) and enlarged picture of the ileocolic portion (B). A – Shortening of the right colon is seen. Diffuse coarse mucosa from the sigmoid colon to the distal part of the descending colon is observed. B - Two stenotic sites in the terminal ileum are indicated by white arrows. There are two entero-enteric fistulas indicated by F. TC, transverse colon; AC, ascending colon; TI, terminal ileum; F, fistula.

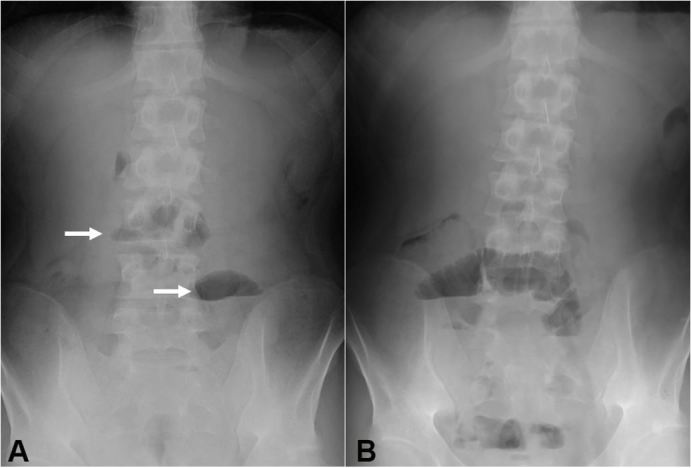

A plant-based diet (800 kcal/day) was concomitantly started. Laboratory data 5 days after the infusion showed apparent improvement (Table 1). He felt better after the 1st infusion of infliximab. His caloric intake increased to 1100 kcal and then 1400 kcal/day. However, he complained of abdominal distension and vomiting on the 11th day after the first infusion. Radiographic signs of intestinal obstruction were found (Figure 5A), and meals were withdrawn. At this point, CRP normalized and CDAI10 decreased from 377 to 115, which is considered to be remission (Table 1). The standard infliximab induction therapy8 proceeded to preserve the left colon. Colonoscopy after the 3rd infusion revealed endoscopic remission in the left colon including scars of the longitudinal ulcers in the sigmoid colon. Resumption of meals (800 kcal/day) resulted in repetition of abdominal distension and air-fluid level on the following day (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Plain abdominal radiographs on the 11th day after the first infusion of infliximab (A) and the day following resumption of meals after the 3rd infliximab infusion (B). Air-fluid levels are indicated by arrows (A).

He then underwent surgery. There were adhesions of the ileum and colon and ileocolonic fistulas (ileum-ascending colon, ileum-sigmoid colon). He underwent ileo-right hemicolonic resection with side (the ileum) to side (the transverse colon) anastomosis and partial sigmoidectomy. The resected specimen showed longitudinal ulcers in the ileum and colon (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Gross examination of the resected specimen of the case 2. The terminal ileum is fixed to the ascending colon by adhesion through fistulas. They were removed en bloc. Arrows indicate longitudinal ulcers (scar).

Considering the signs of poor prognosis (penetrating type of CD, association of anal fistula, onset at a young age, and terminal ileal involvement),11-13 scheduled maintenance therapy with infliximab14 was initiated. A few months later, although there were no symptoms, colonoscopy was performed because CRP had increased from 0.3 to 1.0 mg/dL and fecal occult blood test had deteriorated from 759 ng/mL to >1000 ng/mL. Endoscopic relapse, i.e., shallow circular ulceration at the site of anastomosis, was observed. Azathioprine (50 mg/day) was added to the therapeutic regimen. The patient has maintained clinical remission for nearly 6 years to the present (with 45 courses of infliximab). His CRP concentration was normal on six of seven occasions in the latest year, and fecal occult blood tests were negative on all seven occasions. We plan to stop infliximab maintenance therapy when he achieves successive normal CRP concentrations and negative fecal occult blood tests for 2 years. His plant-based diet score was 6 of 40 before admission and 24 of 40 at 27 months after discharge.

DISCUSSION

Lichtenstein et al.15 reported that infliximab therapy per se did not increase intestinal stenosis, stricture, or obstruction (SSOs) in CD. In their study, however, SSOs that did not necessitate surgery were included and the observation period extended to 1.8 years. There is no description of early development of obstruction necessitating surgery in their report.15

The intervals from infliximab infusion to development of an obstruction in our two cases were 11 and 13 days. In our cases, symptoms and laboratory data clearly improved after infliximab therapy (Table 1). The induction treatment with adalimumab did not obstruct any of the 97 patients with symptomatic small bowel stricture.16 Adalimumab was then switched to infliximab in 35 nonresponders. Eight out of these 35 patients subsequently required intestinal resection. The exact timing of the resections is not described.16 On the other hand, infliximab caused intestinal obstruction necessitating surgery in four of six patients with symptomatic small bowel stricture.17 Two patients underwent surgery 10 days after infliximab due to deterioration. The other two patients showed symptomatic relief first but deteriorated later, resulting in resection within 8 weeks after infliximab.17 Clinical improvement was achieved using infliximab in all 17 cases reported by Toy et al.6 and in all seven cases reported by Vasilopoulos et al.7 before obstructive symptoms appeared. Therefore, our observation together with others6,7,17 supports the interpretation that infliximab is so swiftly effective in healing ulcers18 that the healing process narrows, even more, the stenotic site, resulting in bowel obstruction. Early obstruction after infliximab administration cannot be categorized as a conventional side effect, but rather as an event due to the efficacy of infliximab. It is unlikely that the plant-based diet per se induced intestinal obstruction because the obstruction occurred in similar chronologic fashion in the absence of the plant-based diet.6,7,17

Considering that the early obstruction after infliximab administration was due to the efficacy of infliximab, IPF therapy was effective in all 46 cases.2 This supports our rationale of IPF therapy: infliximab as first-line treatment and incorporation of a plant-based diet.2 Immunomodulators were not needed for induction of remission in our IPF therapy.

When biologics and/or immunomodulators should be withdrawn is an unsolved issue.19 CD is relentless. The stable quiescent phase is ascertained by clinical remission and normal biomarkers (CRP, fecal occult blood). If these conditions last for 2 years and morphological remission is ascertained with endoscopy, we believe that relapse is unlikely to occur. Therefore, we withdraw infliximab first. If clinical course is uneventful for the next few years, then azathioprine is withdrawn.

In the absence of signs of obstruction, stricture per se is no longer regarded as a contraindication for infliximab therapy.20,21 Indeed, no obstruction occurred after infliximab treatment in our 11-case series of patients with stricture.2 If bowel obstruction happens after infliximab therapy, it is surgically treated without any disadvantages due to infliximab use.22,23 Infliximab use may be an advantage in terms of improving the patient’s clinical condition because the obstruction will not occur if infliximab is ineffective.7 It is critical that CD patients with stricture, and particularly CD patients with the penetrating type like case 2 of this report, are fully informed about the risk of intestinal obstruction necessitating surgery prior to initiating infliximab therapy.

Footnotes

How to cite: Chiba M, Tanaka Y, Ono I. Early intestinal obstruction after infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease. Autops Case Rep [Internet]. 2019;9(1):e2018068. https://doi.org/10.4322/acr.2018.068

The study ID number: UMIN000019061, UMIN000020335: Registration: http://www.umin.ac.jp

Financial support: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Chiba M, Abe T, Tsuda H, et al. Lifestyle-related disease in Crohn’s disease: relapse prevention by a semi-vegetarian diet. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(20):2484-95. 10.3748/wjg.v16.i20.2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiba M, Tsuji T, Nakane K, et al. Induction with infliximab and a plant-based diet as first-line (IPF) therapy in Crohn disease: a single-group trial. Perm J. 2017;21(4):17-009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiba M, Tsuji T, Nakane K, Ishii H, Komatsu M. How to avoid primary nonresponders to infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(11):E55-6. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn’s disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(2):323-33. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.030. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Haens G, Van Deventer S, Van Hogezand R, et al. Endoscopic and histological healing with infliximab anti-tumor necrosis factor antibodies in Crohn’s disease: a European multicenter trial. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(5):1029-34. 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toy LS, Scherl EJ, Kornbluth A, et al. Complete bowel obstruction following initial response to infliximab therapy for Crohn’s disease: a series of newly described complication. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:A569. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasilopoulos S, Kugathasan S, Saeian K, et al. Intestinal strictures complicating initially successful infliximab treatment for luminal Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2503. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB. Infliximab in the treatment of Crohn’s disease: a user’s guide for clinicians. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(12):2962-72. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiba M, Nakane K, Takayama Y, et al. Development and application of a plant-based diet scoring system for Japanese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Perm J. 2016;20(4):62-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanauer SB, Sandborn W, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology . Management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(3):635-43. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenstein AJ, Lachman P, Sachar DB, et al. Perforating and non-perforating indications for repeated operations in Crohn’s disease: evidence for two clinical forms. Gut. 1988;29(5):588-92. 10.1136/gut.29.5.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Predictors of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):650-6. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solberg IC, Vatn MH, Høie O, et al. Clinical course in Crohn’s disease: results of a Norwegian population-based ten-year follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(12):1430-8. 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutgeerts P, D’Haens G, Targan S, et al. Efficacy and safety of retreatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody (infliximab) to maintain remission in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(4):761-9. 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70332-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lichtenstein GR, Olson A, Travers S, et al. Factors associated with the development of intestinal strictures or obstructions in patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(5):1030-8. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouhnik Y, Carbonnel F, Laharie D, et al. Efficacy of adalimumab in patients with Crohn’s disease and symptomatic small bowel stricture: a multicentre, prospective, observational cohort (CREOLE) study. Gut. 2018;67(1):53-60. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louis E, Boverie J, Dewit O, Baert F, De Vos M, D’Haens G. Treatment of small bowel subocclusive Crohn’s disease with infliximab: an open pilot study. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2007;70(1):15-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiba M, Sugawara T, Tsuda H, Abe T, Tokairin T, Kashima Y. Esophageal ulcer in Crohn’s disease: disappearance in 1 week with infliximab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(8):1121-2. 10.1002/ibd.20769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torres J, Boyapati RK, Kennedy NA, Louis E, Colombel JF, Satsangi J. Systematic review of effects of withdrawal of immunomodulators or biologic agents from patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1716-30. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorrentino D. Role of biologics and other therapies in stricturing Crohn’s disease: what have we learnt so far? Digestion. 2008;77(1):38-47. 10.1159/000117306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pelletier AL, Kalisazan B, Wienckiewicz J, Bouarioua N, Soule JC. Infliximab treatment for symptomatic Crohn’s disease strictures. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(3):279-85. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fumery M, Seksik P, Auzolle C, et al. Postoperative complications after ileocecal resection in Crohn’s disease: a prospective study from the REMIND Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(2):337-45. 10.1038/ajg.2016.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotze PG, Saab MP, Saab B, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors did not influence postoperative morbidity after elective surgical resection in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(2):456-64. 10.1007/s10620-016-4400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]