Abstract

Background:

As tooth loss declines in an ageing America, retaining enough natural teeth for function is important for quality of life.

Methods:

Data from the 1999-2004 and 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) were used to assess changes in tooth loss in adults age 50 and older. Changes in edentulism, retaining all teeth, and having a functional dentition (21 or more natural teeth) by poverty status were evaluated.

Results:

Edentulism was lower in 2009-2014 compared to 1999-2004 (11% vs. 17%) for adults age 50 and older, but this decrease was not significant among the poor. Complete tooth retention improved from 14% to 21% between 1999-2004 and 2009-2014 for persons age 50 and older. Gains were mostly attributed to non-poor adults. More older adults had a functional dentition in 2009-2014 compared to 1999-2004 (67% vs. 55%), although the increases generally were significant only for those not living in poverty.

Conclusion:

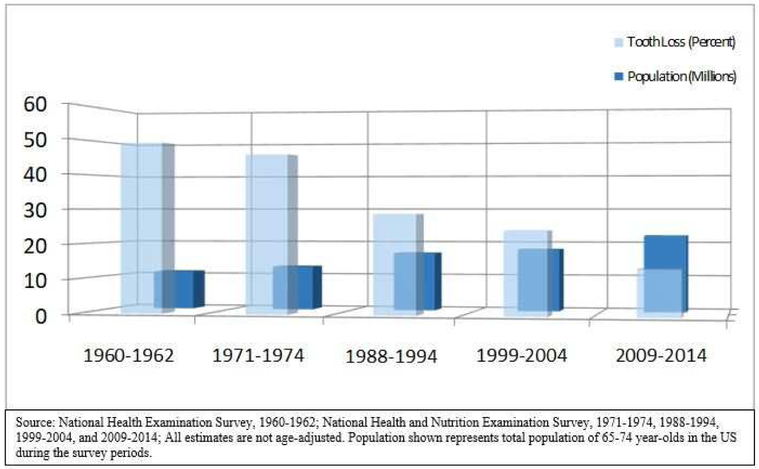

Complete tooth loss has declined by more than 75% for those age 65-74 years over the past five decades in the US. Tooth loss measures improvements, such as edentulism and complete tooth retention, have been most significant among the non-poor, while poor have experienced less improvements.

Practice Implications:

With an aging population that is experiencing less edentulism and more tooth retention, older adults may need more regular dental care and prevention services to address concerns such as dental root caries and periodontal disease.

Keywords: Edentulism, functional dentition, poverty, oral health, epidemiology, dental public health, NHANES, health disparities, adults

INTRODUCTION

The population of older adults in the United States continues to grow over time, with the number of individuals age 65 years and older expected to double by the year 20501. This trend has been propelled by the aging baby-boomer population, and it will result in an increased geriatric population for whom the healthcare system will need to care for. As it relates to oral health, older adults possess unique risk factors for tooth loss including: the lack of a routine oral health benefit in Medicare; side effects of taking multiple medications, such as xerostomia; and less access to oral healthcare 2,3.

The complete loss of natural teeth represents the cumulative aftereffect of severe dental caries and periodontal disease, both of which share recurring exposure to risk factors (e.g. unhealthy diet or tobacco use) commonly associated with other chronic diseases. Globally, edentulism affects approximately 30% of adults age 65-74 years with prevalence accelerating in low-to-mid-income countries 4. Although 2.5 billion people world-wide have untreated dental caries and accounts for much of the overall burden of prevalent adverse oral health conditions 5, edentulism constitutes a substantial amount of the overall global burden when the disability adjusted life year (DALY) measure is used 6.

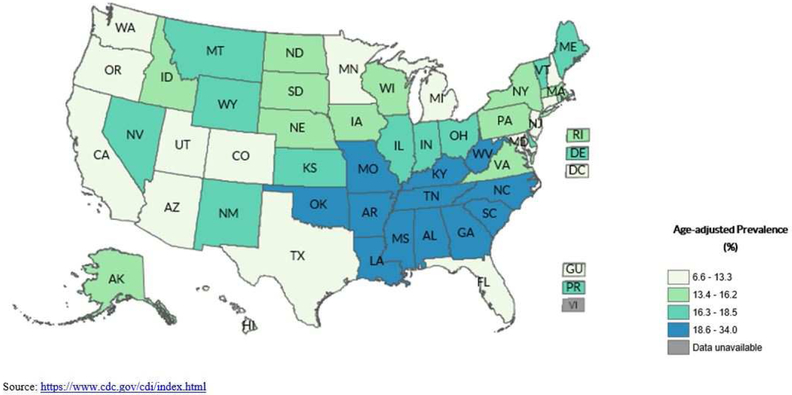

Among adults age 65-74 in the United States, the prevalence of edentulism has declined by more than 75% in the past 5 decades with social-determinants accounting for sizeable differences among population groups 7,8. Edentulism also varies substantially by geographical area in the United States. In 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that edentulism among adults age 65 and older was highest in West Virginia (34%) and lowest in Hawaii (7%) (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, older adults are retaining more of the natural dentition longer which is likely due to increased exposures to fluoride, better preventive modalities, and an increased desire for tooth preservation 3,8,9,10,11.

Figure 1.

Complete tooth loss among adults 65 years of age and older by states, United States 2014

Understanding the prevalence of complete tooth retention (no natural tooth loss) and functional dentition (having at least 21 natural teeth) in older adults is also important because as the number of missing natural teeth increases, chewing function decreases 12,13. Poorer chewing function can subsequently result in decreased dietary quality and nutrient intake 14,15 and older adults with 10 or fewer teeth are less likely than those with 11 or more teeth to meet dietary recommendations 16. Generally, older adults who are either edentulous, have fewer natural teeth, or fewer pairs of posterior teeth are less likely to eat fruits and vegetables like fresh apples, oranges, pears, carrots, tomatoes, and dark yellow and green leafy vegetables including salads, nuts, cooked meats, and well-done steaks 17,18,19,20,21,22. Overall, tooth loss can have a negative effect on individual’s oral health-related quality of life 23,24.

Disparities have been observed based on poverty status for edentulism 25,26,27. National survey data from 2005-2008 found that adults age 65 and older living below 100% of the FPL had over twice the prevalence of complete tooth loss (37%) as those living at 200% of the FPL or higher (16%) 26. However, little information is known regarding observed disparities for tooth retention among older adults by poverty status. For working-age adults, those aged 20-64 living at 200% of the poverty level or higher had a significantly higher prevalence of complete tooth retention (52%) than near poor adults (44%) or poor adults (40%) 26. This suggests that inequalities in tooth retention for older adults (age 65 and older) exist by poverty status. To the authors’ knowledge, national estimates for the prevalence of missing teeth by tooth type (i.e. tooth number) in older adults currently are not available. Moreover, there is no contemporary information on individual tooth loss by poverty status.

The purpose of the current study is to understand the changes related to tooth loss among older adults by poverty status in the United States from 1999-2004 to 2009-2014. Specifically, we aim to: (1) ascertain the prevalence of edentulism, complete dentition, and functional dentition among older adults by selected demographics from 1999-2004 to 2009-2014; and (2) to assess the prevalence of individual missing teeth in older adults and to explore patterns of tooth loss by poverty status from 1999-2004 to 2009-2014.

METHODS

Data source

Data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999-2004 and 2009-2014 were used for this study. The NHANES is a cross-sectional survey that uses a stratified, multistage sampling design to obtain a representative probability sample of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population of the United States. Multiple two-year periods can be combined to form a national probability sample for a longer time period to improve estimation, power, and reliability. Oral health data collection protocols were approved by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Ethics Review Board (an Institutional Review Board equivalent) and all survey participants provided written informed consent.

Participants were interviewed in their homes and received a health examination in mobile examination centers (MEC). All oral health examinations were conducted in a MEC by trained dental examiners who were general dentists, except for in 2009-2010 when the examiners were registered dental hygienists. All dental examiners were trained and calibrated by the survey’s reference examiner. Examination techniques and criteria for assessing tooth presence were consistent throughout the entire study period. Overall, data quality and examiner reliability analyses indicated that examiner performance was similar between the two survey periods being compared (1999-2004 and 2009-2014) 28,29,30,31. Additional information about NHANES can be located at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm.

Study population

For our study, data on persons age 50 and older who participated in either NHANES 1999-2004 or NHANES 2009-2014 with information on poverty were included in the analytical sample. There were 16,006 older adults participating in the home interview during 1999-2004 and 2009-2014. Among these individuals, 13,480 completed an oral health exam. After excluding persons with no information on poverty status and not including persons identified as multi-racial or “other” race, we had 11,476 older adults in our analytical sample. Detailed information on the demographic distribution of the study population is presented in eTable 1.

eTable 1.

Number of sampled persons 50 years of age or older participating in NHANES by selected demographics: United States, 1999-2004 and 2009-2014

| 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIQ | MEC | OHX | HIQ | MEC | OHX | |

| Total | 7,493 | 6,776 | 6,316 | 8,513 | 8,206 | 7,164 |

| Age | ||||||

| 50-64 yrs | 3,144 | 2,966 | 2,777 | 4,434 | 4,315 | 3,843 |

| 65-74 yrs | 2,085 | 1,942 | 1,816 | 2,233 | 2,162 | 1,864 |

| 75 yrs or more | 2,264 | 1,868 | 1,723 | 1,846 | 1,729 | 1,457 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 3,845 | 3,436 | 3,175 | 4,350 | 4,187 | 3,608 |

| Male | 3,648 | 3,340 | 3,141 | 4,163 | 4,019 | 3,556 |

| Race / Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 4,331 | 3,851 | 3,644 | 3,908 | 3,784 | 3,314 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1,262 | 1,168 | 1,065 | 1,918 | 1,853 | 1,655 |

| Mexican American | 1,415 | 1,324 | 1,213 | 1,034 | 994 | 827 |

| Other Race | 286 | 257 | 239 | 834 | 792 | 687 |

| Other Hispanic | 199 | 176 | 155 | 819 | 783 | 681 |

| Poverty Status¥ | ||||||

| Poor (<100%FPG) | 1,063 | 971 | 893 | 1,534 | 1,472 | 1,246 |

| Near Poor (100-199%FPG) | 1,926 | 1,738 | 1,616 | 2,091 | 2,006 | 1,765 |

| Non-Poor (≥200%FPG) | 3,635 | 3,369 | 3,197 | 4,046 | 3,945 | 3,494 |

Notes

Based on federal poverty guidelines; HIQ is number of sampled persons completing a Home Interview Questionnaire; MEC is a Mobile Examination Center; and OHX is an Oral Health Examination.

Variables

All three key outcome variables were based on the presence or absence of natural, permanent teeth only. Edentulism was defined as the complete loss of all permanent teeth (32 teeth in all), tooth retention (complete dentition) was defined as having all 28 permanent teeth present (excluding third molars), and a functional dentition was defined as having 21 or more permanent teeth (excluding third molars). Age was categorized into three groups: age 50-64 years, 65-74 years, and 75 years and older. Race/ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic to reflect the survey’s sampling strategy and to follow the NHANES analytical guidelines 32. Hispanics include Mexican Americans and other Hispanics.

Poverty status was defined as the ratio of family income to The Department of Health and Human Services’ poverty guidelines (FPG), and varies by family size and calendar year. This measure was used instead of reported family income to provide a consistent measure independent of changing monetary value over time. For example, in 2014 the poverty threshold for a family of four was $23,850. This means that a 2014 survey participant with this family income and this family size was classified to be at 100% of the poverty level. In 2004, the poverty threshold for a family of four was $19,223. Additional information can be located at http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/11poverty.shtml. For our study, poverty status was defined as poor (0-99% FPG), near-poor (100-199% FPG), and non-poor (200% FPG and higher).

Data Analysis

The analytical approach used in this report was comparable to methods previously published 33. Estimates were age adjusted to the 2010 US population to account for changes in population distribution between the two periods of data collection. Population estimates and standard errors using Taylor Series Linearization were calculated. Differences between groups were evaluated using a t-statistic at the p < 0.05 significance level. All results with a relative standard error (RSE) equal to or greater than 30% but less than 40% were reported but should be interpreted with caution. Estimates with a RSE > 40% were considered data statistically unreliable (DSU) and not reported. The RSE is equal to the standard error of a survey estimate divided by the survey estimate and then multiplied by 100 for expression to a percentage. Tests were conducted without adjustment for other socio-demographic factors, except for age adjustment as previously described. All analyses were undertaken using SAS 9.4 Survey Procedures (SAS Institute Inc.) except for the graphs illustrating individual toot loss, which were conducted in STATA/SE 14.2 and the Heatmaps, which were conducted in R. All differences discussed are statistically significant unless otherwise indicated.

RESULTS

In 2009-2014, 11% or about 6.2 million Americans age 50 and older were edentulous and complete tooth loss was lower compared to 1999-2004 (11% vs. 17%) (Table 1). Although edentulism was lower in 2009-2014 (23%) compared to 1999-2004 (30%) for adults living in poverty, the difference was not statistically significant. However, men living in poverty experienced a substantial decrease in edentulism (29% vs. 20%), whereas women living in poverty did not (30% vs. 26%). Overall, 1.7 million adults age 65-74 years were edentulous in 2009-2014. Edentulism declined from 23% to 13% for those age 65-74 years between 1999-2004 and 2009-2014 and was substantially lower for the non-poor and those living near poverty. For these older adults living in poverty, edentulism was lower, but the difference was not significant (37% vs. 29%). Among those age 65-74 years, edentulism declined substantially for men living in poverty (50% vs. 26%) but remained unchanged for women in poverty (28% vs. 31%).

Table 1.

Prevalence of edentulism among people 50 years of age and older, by selected characteristics: United States, 1999-2004 and 2009-2014

| Poverty Status |

All | Male | Female | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | ||||||||||||||

| AGE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | |

| 50-64£ | 1 Poor | 22.02 | 3.10 | 17.16 | 3.21 | 21.28 | 4.16 | 17.58 | 2.84 | 22.14 | 2.85 | 17.76 | 2.98 | 17.16 | 6.17†† | 7.60 | 2.12 | 21.10 | 3.82 | 10.97 | 2.72* | 23.92 | 4.18 | 22.88 | 4.34 |

| 2 Near Poor | 17.68 | 2.20 | 10.53 | 1.99* | 15.59 | 2.98 | 9.73 | 2.51 | 19.91 | 3.32 | 11.55 | 2.83 | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | 16.82 | 3.06 | 8.80 | 2.60 | 20.72 | 2.97 | 13.80 | 2.34 | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 7.70 | 0.74 | 3.39 | 0.68* | 9.49 | 1.15 | 3.83 | 0.98* | 5.82 | 0.92 | 2.88 | 0.81* | DSU | DSU | 3.11 | 0.95†† | 10.44 | 1.53 | 4.51 | 1.03* | 7.85 | 0.83 | 3.38 | 0.79* | |

| Total | 10.68 | 0.93 | 6.30 | 0.96* | 11.39 | 1.28 | 6.17 | 1.05* | 9.95 | 1.13 | 6.62 | 1.24 | 7.47 | 2.24 | 3.80 | 0.80 | 14.29 | 1.43 | 7.47 | 1.27* | 10.75 | 1.07 | 6.51 | 1.13* | |

| 65-74£ | 1 Poor | 37.27 | 5.00 | 29.22 | 3.37 | 49.61 | 4.91 | 25.94 | 5.08* | 27.62 | 5.62 | 31.30 | 3.15 | 35.39 | 6.49 | 26.02 | 5.06 | 29.99 | 3.36 | 28.95 | 4.82 | 46.70 | 6.32 | 33.99 | 6.22 |

| 2 Near Poor | 33.18 | 2.58 | 22.95 | 3.87* | 36.53 | 3.51 | 33.55 | 5.38 | 29.66 | 3.08 | 15.89 | 3.33* | 18.18 | 4.61 | 12.06 | 3.36 | 28.31 | 5.18 | 20.61 | 3.43 | 35.83 | 3.13 | 27.82 | 5.57 | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 16.97 | 1.56 | 7.75 | 1.14* | 13.73 | 1.92 | 9.28 | 1.98 | 20.09 | 2.29 | 6.39 | 1.59* | 16.60 | 3.26 | 10.76 | 3.39†† | 23.66 | 4.06 | 14.88 | 3.46 | 16.41 | 1.83 | 7.23 | 1.30* | |

| Total | 23.26 | 1.52 | 13.33 | 1.67* | 21.59 | 1.93 | 15.13 | 2.39* | 24.35 | 2.06 | 11.94 | 1.63* | 25.27 | 5.16 | 14.71 | 2.28 | 24.53 | 2.43 | 20.38 | 2.23 | 22.84 | 1.73 | 12.60 | 2.14* | |

| 75 or more£ | 1 Poor | 47.11 | 3.86 | 36.44 | 3.91 | 34.32 | 5.71 | 30.53 | 7.40 | 50.70 | 4.49 | 36.83 | 5.67 | 36.44 | 5.19 | DSU | DSU | 47.01 | 8.37 | 47.27 | 10.56 | 49.12 | 5.21 | 39.63 | 6.61 |

| 2 Near Poor | 39.52 | 3.05 | 30.08 | 2.53* | 39.39 | 2.68 | 29.06 | 3.73* | 39.50 | 3.76 | 30.21 | 3.62 | 50.44 | 8.30 | DSU | DSU | 40.69 | 4.61 | 40.93 | 8.16 | 38.50 | 3.22 | 29.47 | 2.76* | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 18.01 | 1.70 | 14.91 | 2.68 | 17.37 | 2.25 | 15.72 | 3.27 | 18.48 | 2.18 | 14.87 | 2.89 | 20.20 | 7.16†† | DSU | DSU | 36.62 | 6.99 | 23.30 | 5.16 | 17.10 | 1.83 | 14.29 | 2.95 | |

| Total | 30.57 | 1.86 | 22.49 | 2.19* | 26.49 | 1.87 | 19.84 | 2.54* | 33.02 | 2.20 | 24.38 | 2.62* | 41.32 | 4.31 | 21.39 | 3.86* | 40.84 | 4.57 | 36.05 | 4.87 | 29.10 | 2.04 | 21.50 | 2.53* | |

| 65 or more¶ | 1 Poor | 42.04 | 3.90 | 33.53 | 3.25 | 41.54 | 3.45 | 29.30 | 4.45* | 40.00 | 5.59 | 35.48 | 4.19 | 36.31 | 7.53 | 18.60 | 2.75* | 35.68 | 5.00 | 39.13 | 5.06 | 46.60 | 5.06 | 36.10 | 5.18 |

| 2 Near Poor | 36.50 | 1.94 | 25.96 | 2.82* | 37.84 | 2.67 | 28.83 | 3.11* | 35.60 | 2.12 | 23.46 | 3.28* | 37.54 | 6.34 | 17.86 | 3.97* | 32.51 | 3.46 | 31.71 | 3.95 | 37.44 | 2.20 | 26.93 | 3.65* | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 17.31 | 1.30 | 11.11 | 1.71* | 15.44 | 1.82 | 11.98 | 2.14 | 19.14 | 1.56 | 10.20 | 1.78* | 24.99 | 7.93†† | 15.27 | 3.69 | 26.39 | 4.08 | 17.43 | 3.30 | 16.63 | 1.52 | 10.52 | 1.84* | |

| Total | 26.51 | 1.41 | 17.61 | 1.67* | 23.67 | 1.66 | 17.10 | 1.82* | 28.55 | 1.53 | 17.83 | 1.80* | 34.11 | 4.91 | 16.79 | 1.75* | 31.09 | 2.79 | 27.67 | 2.54 | 25.64 | 1.58 | 16.66 | 2.05* | |

| 50 or more± | 1 Poor | 30.02 | 2.47 | 23.43 | 2.55 | 29.28 | 3.55 | 20.26 | 2.28* | 29.59 | 3.14 | 25.63 | 3.53 | 25.52 | 6.93 | 11.97 | 1.76 | 25.95 | 3.10 | 22.72 | 3.38 | 33.20 | 3.16 | 27.68 | 3.40 |

| 2 Near Poor | 25.59 | 1.62 | 16.86 | 1.66* | 24.36 | 2.01 | 18.26 | 2.45 | 26.70 | 2.36 | 15.65 | 2.16* | 18.96 | 2.91 | 8.06 | 1.71* | 23.87 | 3.19 | 18.51 | 2.54 | 28.35 | 1.91 | 18.70 | 2.09* | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 11.24 | 0.75 | 6.54 | 0.86* | 11.33 | 1.03 | 7.02 | 1.06* | 11.11 | 0.97 | 6.04 | 0.99* | 11.14 | 3.17 | 7.87 | 1.38 | 16.26 | 1.90 | 9.76 | 1.50* | 11.07 | 0.85 | 6.26 | 0.94* | |

| Total | 16.68 | 0.99 | 10.88 | 1.10* | 15.75 | 1.11 | 10.54 | 1.22* | 17.30 | 1.12 | 11.09 | 1.16* | 17.62 | 3.05 | 8.98 | 0.90* | 20.26 | 1.37 | 15.69 | 1.47* | 16.38 | 1.13 | 10.57 | 1.33* | |

Notes: Edentulism is complete tooth loss (32 teeth)

Estimates from NHANES 1999-2004 and 2009-2014 were adjusted by single years of age from the 2010 US population

Estimates were adjusted by grouped age (65-74 and 74 and more) from the 2010 US population

Estimates were adjusted by grouped age (50-64, 65-74 and 74 and more) from the 2010 US population

statistical significance: p < 0.05.

Does not meet standards of statistical reliability and precision (relative standard error ⇒ 30% but < 40%). DSU: Data statistically unreliable (relative standard error ⇒ 40%).

There were important improvements in edentulism by race/ethnic groups between 1999-2004 and 2009-2014 too. Overall edentulism was lower for all Hispanics age 50 and older (18% vs. 9%). Among older Hispanics age 65 and older living in poverty, edentulism declined from 36% to 19%. Although complete tooth loss was also lower for all non-Hispanic blacks age 50 and older during the same period (20% vs. 16%), this decline mostly affected adults age 50-64 years, particularly among non-Hispanic blacks living in poverty (21% vs. 11%). Edentulism declined from 16% to 11% for non-Hispanic whites age 50 and older between 1999-2004 and 2009-2014. Although poor non-Hispanic whites generally had higher estimates of edentulism compared to similar-aged non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics, non-Hispanic whites living at 200% or higher of the federal poverty guidelines continued to experience a decline in edentulism. For example, non-poor adults age 65-74 years, edentulism declined from 16% to 7%.

Table 2 shows the prevalence of a complete tooth retention (i.e., no natural tooth loss) for persons age 50 and older. Overall, 11.8 million adults age 50 and older have a complete natural dentition and complete tooth retention improved from 14% to 21% between 1999-2004 and 2009-2014. Gains were mostly attributed to non-poor adults across the various age groups evaluated, with some of the more substantial gains observed for those age 50-64 years. Among these adults, complete tooth retention improved for those living near poverty and the non-poor (5% vs. 14% and 23% vs. 35%, respectively). Overall, complete tooth retention improved from 14% to 23% for women. Generally, improvement was observed across all the age groups for women and mostly for those living near poverty and the non-poor. Although the prevalence of complete tooth retention improved for non-Hispanic blacks and whites (16% to 24% for non-Hispanic whites) between 1999-2004 and 2009-2014, non-Hispanic blacks continued to experience lower tooth retention (4% vs. 7%). There was no change in complete tooth retention for Hispanics during this period (8% vs. 9%).

Table 2.

Prevalence of a complete dentition among people 50 years of age and older, by selected characteristics: United States, 1999-2004 and 2009-2014

| Poverty Status |

All | Male | Female | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | ||||||||||||||

| AGE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | |

| 50-64£ | 1 Poor | 7.81 | 2.27 | 4.92 | 0.93 | 6.63 | 2.09†† | 5.19 | 1.40 | 5.07 | 1.72†† | 4.48 | 1.13 | 7.17 | 2.71†† | 7.61 | 2.05 | 6.37 | 2.43†† | DSU | DSU | 8.16 | 2.93†† | 4.95 | 1.51†† |

| 2 Near Poor | 5.16 | 1.31 | 13.67 | 2.20* | 4.18 | 1.21 | 7.40 | 2.39†† | 4.96 | 1.65†† | 17.82 | 2.89* | 6.60 | 2.38†† | 14.60 | 3.84 | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | 4.67 | 1.59†† | 16.50 | 2.23* | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 22.66 | 1.49 | 34.73 | 2.24* | 22.24 | 1.69 | 33.70 | 2.78* | 22.83 | 1.76 | 35.37 | 2.67* | 11.37 | 2.10 | 15.97 | 2.53 | 5.72 | 1.28 | 16.49 | 1.85* | 25.02 | 1.69 | 38.12 | 2.43* | |

| Total | 18.86 | 1.31 | 27.46 | 1.84* | 18.89 | 1.49 | 26.03 | 2.11* | 18.55 | 1.45 | 28.40 | 2.26* | 8.78 | 1.35 | 12.69 | 1.67 | 5.18 | 1.08 | 9.80 | 1.08* | 21.74 | 1.64 | 32.01 | 2.08* | |

| 65-74£ | 1 Poor | DSU | DSU | 6.37 | 1.90 | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | 8.52 | 2.47 | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU |

| 2 Near Poor | 3.16 | 1.07†† | 7.79 | 2.47†† | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | 10.82 | 2.89* | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | 8.14 | 1.91* | 3.36 | 1.25†† | 7.83 | 3.07†† | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 11.11 | 1.09 | 18.84 | 2.26* | 9.64 | 2.00 | 17.22 | 2.65* | 12.67 | 1.90 | 21.63 | 3.70* | 25.34 | 5.48 | 9.15 | 3.12*†† | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | 11.08 | 1.19 | 20.74 | 2.57* | |

| Total | 8.48 | 0.79 | 15.39 | 1.86* | 7.57 | 1.27 | 13.84 | 2.34* | 9.42 | 1.24 | 17.13 | 2.44* | 9.96 | 2.87 | 5.29 | 1.68†† | DSU | DSU | 4.32 | 1.21 | 8.97 | 0.89 | 17.83 | 2.29* | |

| 75 or more£ | 1 Poor | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU |

| 2 Near Poor | 2.56 | 0.83†† | DSU | DSU | 4.28 | 1.23 | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | 2.77 | 0.92†† | DSU | DSU | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 7.00 | 1.41 | 8.84 | 1.69 | 7.17 | 1.92 | 5.97 | 1.93†† | 7.05 | 1.89 | 11.84 | 2.78 | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | 7.55 | 1.51 | 9.66 | 1.88 | |

| Total | 4.59 | 0.65 | 6.48 | 1.04 | 5.39 | 1.11 | 4.95 | 1.37 | 4.12 | 0.83 | 7.58 | 1.40* | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | 5.07 | 0.73 | 7.42 | 1.23 | |

| 65 or more¶ | 1 Poor | DSU | DSU | 4.28 | 1.39†† | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | 5.86 | 1.90†† | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU |

| 2 Near Poor | 3.08 | 0.72 | 6.43 | 1.85 | 4.18 | 0.97 | 5.53 | 2.15†† | 2.45 | 0.88†† | 7.05 | 1.90* | 2.45 | 0.85†† | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | 4.79 | 1.32* | 3.41 | 0.84 | 7.08 | 2.46†† | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 9.21 | 0.81 | 14.31 | 1.70* | 8.35 | 1.17 | 12.08 | 1.95 | 10.06 | 1.37 | 16.56 | 2.27* | 14.15 | 5†† | 5.67 | 1.79*†† | DSU | DSU | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.45 | 0.89 | 15.64 | 1.93* | |

| Total | 6.79 | 0.55 | 11.23 | 1.15* | 6.60 | 0.79 | 9.85 | 1.56 | 7.04 | 0.82 | 12.37 | 1.36* | 6.77 | 2.48†† | 3.09 | 0.92 | DSU | DSU | 2.86 | 0.81* | 7.31 | 0.62 | 12.84 | 1.42* | |

| 50 or more± | 1 Poor | 6.67 | 1.89 | 4.55 | 0.67 | DSU | DSU | 3.45 | 0.87 | 6.30 | 2.07†† | 5.02 | 0.76 | DSU | DSU | 5.18 | 1.36 | DSU | DSU | DSU | DSU | 7.94 | 2.97†† | 4.73 | 1.28 |

| 2 Near Poor | 4.49 | 1.01 | 10.96 | 2.10* | 4.95 | 1.33 | 6.96 | 2.62 | 4.22 | 1.17 | 14.16 | 2.68* | 4.64 | 1.55†† | 7.61 | 1.90 | DSU | DSU | 4.57 | 1.37 | 4.84 | 1.36 | 13.01 | 2.69* | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 17.34 | 0.96 | 26.48 | 1.62* | 16.78 | 1.01 | 24.49 | 1.99* | 17.90 | 1.22 | 28.49 | 2.05* | 13.15 | 2.78 | 12.09 | 1.68 | 4.12 | 0.85 | 9.79 | 1.29* | 18.78 | 1.06 | 28.88 | 1.72* | |

| Total | 14.11 | 0.86 | 20.93 | 1.35* | 14.23 | 0.95 | 19.27 | 1.63*†† | 14.03 | 1.00 | 22.46 | 1.63* | 8.28 | 1.46 | 8.86 | 1.06 | 3.62 | 0.75 | 7.14 | 0.85* | 16.00 | 1.05 | 24.18 | 1.50* | |

Notes: Complete dentition is missing no teeth (28 teeth)

Estimates from NHANES 1999-2004 and 2009-2014 were adjusted by single years of age from the 2010 US population

Estimates were adjusted by grouped age (65-74 and 74 and more) from the 2010 US population

Estimates were adjusted by grouped age (50-64, 65-74 and 74 and more) from the 2010 US population

statistical significance: p < 0.05.

Does not meet standards of statistical reliability and precision (relative standard error⇒ 30% but < 40%). DSU: Data statistically unreliable (relative standard error ⇒ 40%).

More adults had a functional dentition (i.e., having 21 or more natural teeth) in 2009-2014 compared to 1999-2004 (67% vs. 55%) (Table 3). Although 37.7 million adults age 50 and older have a functional dentition, 18.6 million adults lacked a functional dentition in 2009-2014. Although increases in retaining a functional dentition were observed across all age groups, these increases generally were significant only for the near poor and non-poor. However, for poor adults age 65-74, having a functional dentition increased significantly from 18% to 31%. Overall, the prevalence of having a functional dentition increased from 43% to 62% for this age group. Overall, more men age 50 and older had a functional dentition in 2009-2014 (67%) than in 1999-2004 (55%); but for poor men, prevalence remained unchanged at 37-38%. Among women, prevalence increased from 55% to 67% as well, but unlike men, there was a substantial increase among poor women (28% vs. 40%) in having a functional dentition. Overall, functional dentition increased for non-Hispanic blacks (35% to 43%), for Hispanics (46% to 55%), and for non-Hispanic whites (58% to 71%). However, prevalence varied greatly by age and poverty.

Table 3.

Prevalence of people with a functional dentition among people 50 years of age and older, by selected characteristics: United States, 1999-2004 and 2009-2014

| Poverty Status |

All | Male | Female | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | ||||||||||||||

| AGE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | |

| 50-64£ | 1 Poor | 39.02 | 3.88 | 47.36 | 3.83 | 39.49 | 4.65 | 45.99 | 4.21 | 33.54 | 3.38 | 48.94 | 3.96* | 39.13 | 5.06 | 61.23 | 3.76* | 35.83 | 5.46 | 41.50 | 4.08 | 37.85 | 4.88 | 43.98 | 5.95 |

| 2 Near Poor | 43.89 | 2.87 | 61.24 | 2.19* | 37.88 | 2.48 | 59.76 | 3.29* | 46.95 | 4.15 | 61.84 | 3.34* | 59.56 | 3.02 | 64.35 | 4.36 | 48.18 | 3.88 | 52.07 | 2.42 | 38.76 | 3.72 | 61.30 | 2.74* | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 71.89 | 1.72 | 82.95 | 1.44* | 67.04 | 2.04 | 80.82 | 2.13* | 76.70 | 1.92 | 85.07 | 1.98* | 68.53 | 4.57 | 79.09 | 2.86 | 49.06 | 3.20 | 63.71 | 2.73* | 74.32 | 1.81 | 85.04 | 1.56* | |

| Total | 64.94 | 1.75 | 74.96 | 1.87* | 61.82 | 1.99 | 73.26 | 2.06* | 67.80 | 1.93 | 76.35 | 2.29* | 59.89 | 3.14 | 69.97 | 2.35* | 45.41 | 2.57 | 55.66 | 1.84* | 67.99 | 2.10 | 78.36 | 2.30 | |

| 65-74£ | 1 Poor | 18.39 | 3.95 | 30.76 | 4.31* | 15.07 | 3.26 | 25.06 | 4.78 | 20.88 | 4.98 | 33.58 | 4.41 | 25.58 | 4.61 | 28.99 | 4.55 | 21.64 | 4.88 | 18.28 | 6.79†† | DSU | DSU | 31.23 | 5.92* |

| 2 Near Poor | 25.82 | 3.18 | 38.43 | 3.86* | 25.43 | 3.83 | 28.82 | 6.05 | 26.24 | 4.48 | 45.59 | 4.42* | 34.01 | 4.78 | 39.49 | 4.90 | 20.05 | 4.42 | 33.26 | 3.73* | 26.14 | 3.86 | 37.33 | 5.06 | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 53.34 | 2.16 | 73.69 | 1.94* | 55.19 | 3.26 | 73.57 | 3.39* | 51.29 | 2.80 | 72.94 | 2.88* | 48.15 | 5.63 | 57.20 | 4.49 | 25.66 | 3.92 | 35.25 | 4.13 | 55.34 | 2.42 | 76.92 | 2.04* | |

| Total | 42.78 | 2.29 | 61.76 | 2.53* | 45.10 | 3.04 | 61.14 | 3.59* | 40.47 | 2.79 | 61.77 | 2.74* | 34.28 | 5.08 | 43.93 | 3.36 | 21.46 | 2.05 | 30.65 | 2.35* | 45.74 | 2.65 | 67.07 | 2.99* | |

| 75 or more£ | 1 Poor | 15.98 | 4.11 | 21.30 | 4.28 | 15.85 | 3.08 | 30.49 | 7.38 | 14.36 | 4.52†† | 20.33 | 5.51 | 9.86 | 3.54†† | DSU | DSU | 10.15 | 3.76†† | DSU | DSU | 18.94 | 4.99 | 27.67 | 7.29 |

| 2 Near Poor | 25.38 | 2.49 | 34.67 | 3.29* | 28.23 | 3.21 | 36.48 | 4.08 | 23.36 | 2.98 | 34.06 | 3.91* | 12.89 | 3.72 | DSU | DSU | 19.13 | 4.29 | DSU | DSU | 26.88 | 2.73 | 37.41 | 3.59* | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 44.69 | 2.51 | 58.57 | 3.17* | 43.53 | 3.50 | 60.23 | 3.31* | 45.68 | 2.98 | 55.79 | 4.41 | 32.28 | 9.06 | DSU | DSU | 18.17 | 4.75 | 21.69 | 6.96†† | 46.10 | 2.65 | 62.22 | 3.37* | |

| Total | 33.04 | 1.99 | 46.40 | 2.97* | 35.94 | 2.63 | 51.90 | 3.00* | 30.79 | 2.18 | 42.30 | 3.66* | 13.64 | 2.53 | 18.91 | 4.70 | 16.27 | 2.66 | 14.94 | 3.26 | 35.52 | 2.13 | 50.85 | 3.35* | |

| 65 or more¶ | 1 Poor | 17.56 | 3.42 | 25.53 | 3.45 | 16.50 | 3.10 | 24.55 | 5.60 | 18.68 | 4.93 | 26.20 | 3.91 | 19.45 | 6.61†† | 23.24 | 3.11 | 15.67 | 2.30 | 16.80 | 6.54†† | 15.57 | 4.72†† | 29.08 | 5.15 |

| 2 Near Poor | 25.60 | 2.30 | 37.70 | 2.76* | 26.71 | 3.01 | 34.57 | 4.25 | 25.08 | 2.68 | 40.38 | 3.30* | 20.79 | 3.65 | 33.31 | 4.26* | 16.84 | 3.20 | 20.95 | 3.46 | 26.75 | 2.67 | 39.49 | 3.41* | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 49.01 | 1.66 | 67.24 | 2.01* | 49.68 | 2.62 | 69.09 | 2.73* | 48.33 | 2.20 | 65.39 | 2.59* | 36.06 | 7.16 | 42.99 | 4.23 | 23.68 | 2.85 | 30.06 | 3.79 | 50.75 | 1.82 | 70.68 | 2.08* | |

| Total | 38.22 | 1.69 | 54.90 | 2.33* | 41.01 | 2.29 | 57.94 | 3.01* | 36.10 | 1.89 | 52.67 | 2.50* | 23.94 | 4.24 | 33.36 | 2.77 | 19.10 | 1.58 | 24.07 | 2.25 | 40.96 | 1.88 | 59.78 | 2.74* | |

| 50 or more± | 1 Poor | 31.72 | 2.83 | 39.22 | 2.86 | 37.24 | 4.16 | 37.98 | 3.89 | 27.76 | 3.51 | 40.29 | 3.25* | 32.09 | 4.42 | 45.93 | 3.04* | 29.00 | 3.86 | 33.01 | 3.61 | 31.77 | 4.02 | 39.06 | 4.52 |

| 2 Near Poor | 36.63 | 2.30 | 52.26 | 1.90* | 34.60 | 2.02 | 48.76 | 2.42* | 38.48 | 3.51 | 55.15 | 2.78* | 44.35 | 2.95 | 49.96 | 3.68 | 30.89 | 3.84 | 38.89 | 2.09 | 34.29 | 2.94 | 54.67 | 2.48* | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 63.46 | 1.37 | 76.39 | 1.33* | 61.20 | 1.73 | 75.88 | 1.52* | 65.82 | 1.50 | 76.93 | 1.77* | 56.91 | 4.09 | 64.88 | 2.67 | 39.53 | 2.54 | 50.43 | 2.45* | 65.51 | 1.47 | 78.96 | 1.44* | |

| Total | 54.93 | 1.53 | 66.81 | 1.81* | 54.62 | 1.75 | 66.89 | 1.94* | 55.49 | 1.61 | 67.03 | 2.02* | 46.44 | 2.89 | 55.12 | 2.11 | 35.18 | 1.66 | 43.02 | 1.70* | 57.82 | 1.82 | 70.81 | 2.18* | |

Notes: Functional dentition is having 21 or more natural teeth (28 teeth)

Estimates from NH 1999-2004 and 2009-2014 were adjusted by single years of age from the 2010 US population

Estimates were adjusted by grouped age (65-74 and 74 and more) from the 2010 US population

Estimates were adjusted by grouped age (50-64, 65-74 and 74 and more) from the 2010 US population

statistical significance: p < 0.05.

Does not meet standards of statistical reliability and precision (relative standard error ⇒ 30% but < 40%). DSU: Data statistically unreliable (relative standard error =⇒ 40%).

The mean number of teeth increased from 20.9 to 22.5 among all adults age 50 and older between 1999-2004 and 2009-2014 (Table 4). Among women living in poverty, the mean number of teeth increased from 17.3 to 19.1. However, poor men did not experience an increase in mean number of teeth (18.3 to 17.1) during the same period. The mean number of teeth for non-Hispanic blacks and whites increased from 17.6 and 21.4 to 18.9 and 23.1 respectively. Although the mean number of teeth was higher for Hispanics between 1999-2004 and 2009-2014 (19.1 vs. 201.), this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 4.

Mean number of permanent teeth among dentate people 50 years of age and older, by selected characteristics: United States, 1999-2004 and 2009-2014

| Poverty Status |

All | Male | Female | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | 1999-2004 | 2009-2014 | ||||||||||||||

| AGE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

| 50-64£ | 1 Poor | 19.08 | 0.41 | 19.63 | 0.38 | 19.24 | 0.47 | 19.14 | 0.63 | 17.87 | 0.47 | 20.41 | 0.43* | 19.48 | 0.73 | 20.98 | 0.47 | 18.16 | 0.86 | 18.26 | 0.54 | 18.74 | 0.55 | 19.86 | 0.55 |

| 2 Near Poor | 18.86 | 0.48 | 21.54 | 0.31* | 17.62 | 0.58 | 21.07 | 0.41* | 19.60 | 0.45 | 21.65 | 0.45* | 20.45 | 0.49 | 21.68 | 0.51 | DSU | DSU | 19.59 | 0.39 | 18.24 | 0.57 | 21.89 | 0.40* | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 22.91 | 0.26 | 24.49 | 0.25* | 22.33 | 0.33 | 24.12 | 0.43* | 23.39 | 0.26 | 24.83 | 0.19* | 21.61 | 0.71 | 23.46 | 0.38* | DSU | DSU | 21.79 | 0.33 | 23.32 | 0.28 | 24.83 | 0.30* | |

| Total | 22.08 | 0.24 | 23.51 | 0.24* | 21.65 | 0.33 | 23.11 | 0.34* | 22.42 | 0.24 | 23.84 | 0.21* | 20.76 | 0.47 | 22.26 | 0.34* | 19.29 | 0.30 | 20.45 | 0.31* | 22.59 | 0.29 | 24.11 | 0.28* | |

| 65-74£ | 1 Poor | 15.76 | 0.89 | 16.52 | 0.86 | 15.73 | 1.09 | 12.78 | 1.07 | 16.04 | 0.98 | 17.69 | 0.80 | 16.83 | 0.63 | 16.85 | 0.93 | DSU | DSU | 14.99 | 1.36 | 13.79 | 1.01 | 15.76 | 1.02 |

| 2 Near Poor | 16.82 | 0.66 | 19.00 | 0.53* | 17.21 | 0.57 | 17.34 | 0.85 | 16.39 | 0.88 | 19.86 | 0.58* | 17.51 | 0.73 | 17.12 | 0.75 | DSU | DSU | 17.74 | 0.67 | 17.05 | 0.81 | 19.61 | 0.58* | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 20.60 | 0.29 | 23.15 | 0.24* | 20.73 | 0.41 | 23.21 | 0.42* | 20.25 | 0.49 | 23.02 | 0.32* | 20.20 | 0.93 | 20.90 | 0.62 | DSU | DSU | 17.86 | 0.74 | 20.90 | 0.30 | 23.58 | 0.25* | |

| Total | 19.39 | 0.30 | 21.84 | 0.25* | 19.71 | 0.39 | 21.70 | 0.44* | 18.93 | 0.43 | 21.91 | 0.29* | 18.15 | 0.68 | 18.89 | 0.69 | 15.32 | 0.61 | 17.14 | 0.53* | 19.88 | 0.34 | 22.64 | 0.26* | |

| 75 or more£ | 1 Poor | 15.45 | 0.87 | 15.78 | 0.97 | 12.77 | 0.94 | 16.22 | 1.74 | 15.80 | 0.79 | 15.88 | 1.12 | 13.46 | 0.93 | 14.05 | 1.24 | 13.71 | 1.01 | DSU | DSU | 16.28 | 1.19 | 17.51 | 1.08 |

| 2 Near Poor | 17.11 | 0.47 | 18.27 | 0.56 | 16.61 | 0.67 | 18.29 | 0.93 | 17.28 | 0.53 | 18.31 | 0.61 | 15.56 | 1.19 | DSU | DSU | 14.48 | 1.32 | DSU | DSU | 17.43 | 0.49 | 18.66 | 0.60 | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 19.50 | 0.36 | 20.99 | 0.40* | 19.10 | 0.58 | 21.07 | 0.56* | 19.89 | 0.42 | 20.72 | 0.65 | 16.72 | 1.78 | DSU | DSU | 14.53 | 1.02 | DSU | DSU | 19.73 | 0.38 | 21.52 | 0.43* | |

| Total | 18.27 | 0.31 | 19.75 | 0.39* | 18.03 | 0.48 | 20.08 | 0.51* | 18.39 | 0.34 | 19.34 | 0.50 | 14.43 | 0.72 | 14.16 | 0.57 | 14.53 | 0.94 | 15.49 | 0.67 | 18.69 | 0.31 | 20.44 | 0.41* | |

| 65 or more¶ | 1 Poor | 15.55 | 0.79 | 16.05 | 0.75 | 14.49 | 0.98 | 14.56 | 1.40 | 16.01 | 0.99 | 16.89 | 0.79 | 15.65 | 1.07 | 15.07 | 0.83 | 15.03 | 0.72 | 15.01 | 1.45 | 15.24 | 1.38 | 16.69 | 1.09 |

| 2 Near Poor | 17.07 | 0.51 | 18.85 | 0.40* | 17.02 | 0.54 | 18.21 | 0.80 | 17.09 | 0.61 | 19.25 | 0.48* | 15.88 | 0.81 | 18.05 | 0.67* | 14.78 | 1.02 | 15.81 | 0.72 | 17.39 | 0.61 | 19.24 | 0.48* | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 20.08 | 0.22 | 22.24 | 0.20* | 19.97 | 0.32 | 22.43 | 0.28* | 20.17 | 0.36 | 22.04 | 0.30* | 18.55 | 1.08 | 18.01 | 0.66 | 15.23 | 0.58 | 17.14 | 0.65* | 20.35 | 0.22 | 22.71 | 0.21* | |

| Total | 18.88 | 0.24 | 20.90 | 0.25* | 19.01 | 0.31 | 21.12 | 0.38* | 18.76 | 0.30 | 20.73 | 0.29* | 16.50 | 0.69 | 16.98 | 0.52 | 14.99 | 0.51 | 16.36 | 0.46* | 19.35 | 0.26 | 21.61 | 0.26* | |

| 50 or more± | 1 Poor | 17.84 | 0.41 | 18.23 | 0.40 | 18.31 | 0.60 | 17.13 | 0.78 | 17.34 | 0.56 | 19.07 | 0.48* | 17.89 | 0.68 | 18.76 | 0.43 | 17.22 | 0.67 | 17.14 | 0.72 | 17.86 | 0.64 | 18.42 | 0.66 |

| 2 Near Poor | 18.26 | 0.39 | 20.59 | 0.27* | 17.69 | 0.47 | 20.02 | 0.41* | 18.76 | 0.44 | 21.01 | 0.33* | 18.48 | 0.47 | 19.94 | 0.43* | 17.08 | 0.56 | 18.02 | 0.39 | 18.16 | 0.52 | 21.18 | 0.32* | |

| 3 Non-Poor | 21.87 | 0.17 | 23.56 | 0.16* | 21.57 | 0.21 | 23.43 | 0.22* | 22.17 | 0.21 | 23.70 | 0.19* | 20.57 | 0.57 | 21.26 | 0.35 | 17.89 | 0.37 | 19.99 | 0.36* | 22.21 | 0.17 | 23.94 | 0.18* | |

| Total | 20.91 | 0.19 | 22.45 | 0.21* | 20.78 | 0.24 | 22.30 | 0.27* | 21.03 | 0.21 | 22.62 | 0.22* | 19.16 | 0.40 | 20.14 | 0.30 | 17.58 | 0.30 | 18.85 | 0.29* | 21.40 | 0.22 | 23.08 | 0.23* | |

Notes: Dentate is based on 28 permanent teeth, excluding 3rd molars

Estimates from NHANES 1999-2004 and 2009-2014 were adjusted by single years of age from the 2010 US population

Estimates were adjusted by grouped age (65-74 and 74 and more) from the 2010 US population

Estimates were adjusted by grouped age (50-64, 65-74 and 74 and more) from the 2010 US population

statistical significance: p < 0.05.

Does not meet standards of statistical reliability and precision (relative standard error ⇒ 30% but < 40%). DSU: Data statistically unreliable (relative standard error ⇒ 40%).

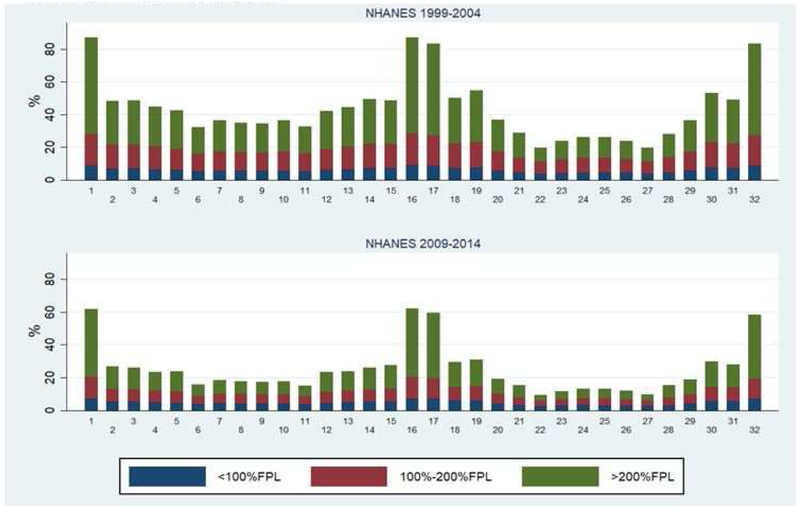

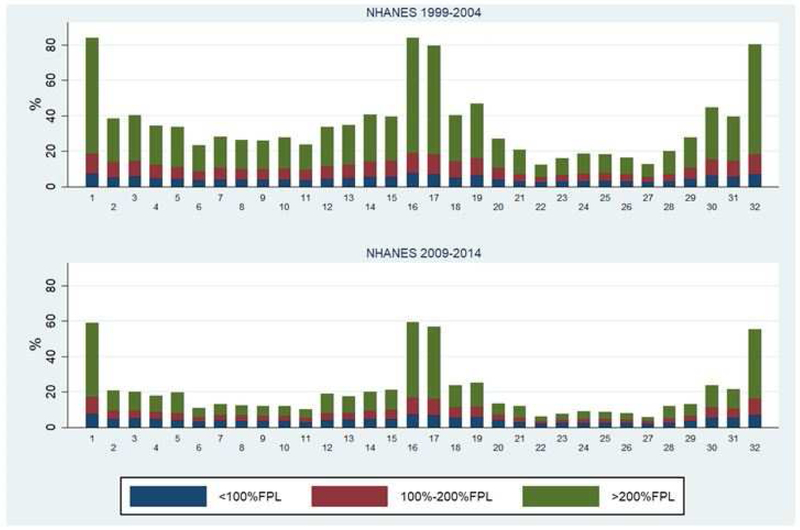

Prevalence of missing teeth was higher for third molars than for any other tooth type (Fig 2). Among adults age 50 and older, more than 80% had either tooth #1, 16, 17, or 32 missing in 1999-2004. The prevalence was lower (approximately 60%) for missing third molars in 2009-2014. For both periods, those living above 200% of the federal poverty guidelines (the non-poor) had the highest proportion of missing third molars compared to the near poor and the non-poor. Mandibular canines (#22 and #27) had the highest retention prevalence among adults age 50 and older. About 1 in 5 people were missing their mandibular canines in 1999-2004 and this decreased to about 1 in 10 in 2009-2014. Among all missing mandibular canines, about 26-27% can be attributed to those living in poverty, about one-third to the near poor, and about 38-39% to the non-poor in 2009-2014. About half of adults were missing their first and second molars in 1999-2004 and this decreased to about a quarter of adults in 2009-2014. The majority of missing first and second molars can be attributed to the non-poor. Individual tooth loss becomes higher in the older age groups and the influence of poverty on tooth loss changes in the older age cohorts (eFigs 1–3). For example, among those age 75 and older, the near poor generally have the highest proportion missing teeth.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of each tooth missing for adults 50 years of age and older with contribution to missing by poverty status: United States, 1999-2004 and 2009-2014

eFigure 1.

Prevalence of each tooth missing for adults 50-64 years of age with contribution to missing by poverty status: United States, 1999-2004 and 2009-2014

eFigure 3.

Prevalence of each tooth missing for adults 75 years of age and older with contribution to missing by poverty status: United States, 1999-2004 and 2009-2014

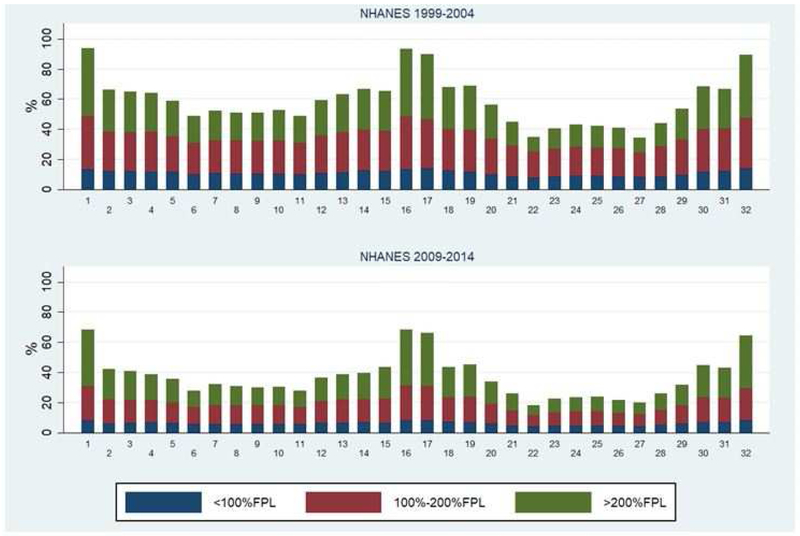

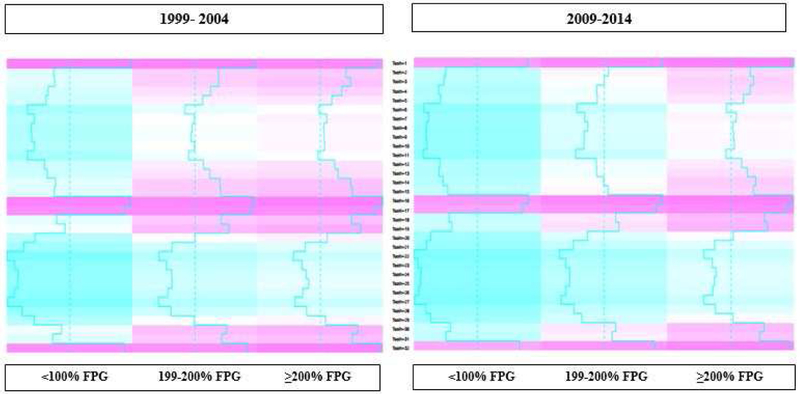

Figure 3 shows changing patterns from 1999-2004 to 2009-2014 in tooth loss. The most notable areas of improvement (changing from pink to teal color tones) for retaining teeth is among the near poor (199-200% FPG) in the maxillary dentition. This shows that gains in tooth retention between the two survey periods, particularly for the upper anterior teeth, was the most substantial among the near poor. Among the poor, there was some modest improvement (changing from light to darker teal) in retaining teeth in both the maxillary and mandibular dentition and there was little change in tooth retention among the nonpoor (color tones remained consistent between the two survey periods).

Figure 3.

Heat map of missing teeth for adults 65 years of age and older with contribution to missing by poverty status: United States, 1999-2004 and 2009-2014

DISCUSSION

Overall, the prevalence of edentulism in adults age 50 and older in the United States has significantly declined from 1999-2004 through 2009-2014 (17% vs. 11%). Likewise, the prevalence of both complete tooth retention (14% vs 21%) and functional dentition (55% vs 67%), and the mean number of permanent teeth (21 vs 22) in adults age 50 and older in the US significantly increased during the same period. Taken together, our analyses of permanent dentition status indicate that older adults in the US have retained more of their natural teeth over the past decade, although important differences in these findings were noted based on some socio-demographic factors, including poverty status. Although the overall change among adults age 50 and older was for a significant improvement in the retention of a natural dentition, this was predominately experienced by adults not living in poverty. The only measure with a significant improvement affecting adults living in poverty was for a functional dentition among older adults age 65-74.

Similar to previous reports on edentulism 33,34, our analyses indicated that while the overall prevalence of edentulism declined for all older adult age groups over the 1999-2004 through 2009-2014 time periods, the decrease tended to only be significant for non-poor and near poor adults. Poor older adults in the total sample, irrespective of their age group, did not experience significant declines in edentulism prevalence. Likewise, as the prevalence of complete tooth retention increased significantly for adults age 50 and older from 1999-2004 through 2009-2014, in general, only non-poor older adults experienced an increase that was significant across socio-demographic factors. However, the increase in complete tooth retention was not significant for adults age 75 or older in the total sample, regardless of poverty status. Compared to an earlier report examining the mean number of permanent teeth in dentate adults age 65 and older from 1988-1994 through 1999-2004 33, which found that only non-poor experienced a significant increase; our more recent data found that both non-poor and near-poor adults age 65 and older in the overall sample experienced a significant increase in complete tooth retention prevalence. Not surprisingly, our analyses also found that the poorest individuals (those living <100% FPL) in each age category of the total sample, did not experience significant increases in the prevalence of functional dentition or mean number of teeth, where as their near-poor and non-poor counterparts did.

While some improvements in the dentate status of the poorest older adults were observed, they tended to not be significant, and their overall oral health status tended to be worse than their non-poor and near poor counterparts. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Seerig and coauthors found that individuals with lower income levels displayed a greater chance of tooth loss compared to those with higher incomes (pooled Odds Ratio of 2.52 (95%CI 2.11–3.01)) 35. Poorer oral health outcomes in lower socioeconomic groups is not surprising, and points to the need for continued efforts to increase access to oral healthcare and to better understand the vast array of social determinants of health that can impact oral health status 36,37,38,39. The association between lower income and poorer oral health behaviors can lead to the progression of oral diseases, and ultimately result in tooth loss 35.

Cost has been cited as the primary barrier for adults and older adults to access dental care 40. The negative impact of poverty on oral health status in older adults may be magnified because Medicare does not contain a routine oral health benefit, and comprehensive oral health benefits for adults are not covered by Medicaid in all states 2. Additionally, access to oral healthcare may be even more challenging for older adult populations 2-3. While it was encouraging to see improvements in dentate status of poor older adults, even if not significant, the fact that these improvements tended to be less than those observed in their nonpoor and near poor counterparts indicates the potential for disparities in dentate status by poverty status to worsen and the need for population-based oral health promotion in older adults to focus more on older adults living in poverty. Additionally, changes that incorporate more comprehensive oral health benefits into public programs may be necessary to help reduce disparities in tooth loss in older adults observed by poverty level, since poor adults and older adults rely more heavily on these programs to access dental care 41.

Both men and women aged 65 and older showed significant declines in the prevalence of edentulism over the 1999-2004 through 2009-2014 time periods, and in 2009-2014 both groups showed a prevalence of approximately 17%. This is an important finding because previous national data comparing changes in edentulism prevalence in adults 65 and older from 1988-1994 through 1999-2004 found that only men experienced a significant decline over the period, and had a substantially lower prevalence than women 33. Findings from the current study suggest that the gender disparity in edentulism in adults age 65 and older has been nearly eliminated. It is important to note that gender differences in edentulism prevalence based on poverty status were noted. Only poor males age 50 and older (and age 65 and older) experienced a significant decline while poor females did not. Additionally, among adults age 75 and older, although both gender groups showed a decline over the period, females (24%) displayed a higher prevalence than males (20%) in 2009-2014.

Adults 50 and older of all race/ethnicity groups experienced significant declines in the prevalence of edentulism from 1999-2004 through 2009-2014; however, racial/ethnic disparities in edentulism were still found to exist. For example, non-Hispanic blacks aged 50 and older displayed a higher prevalence (16%) than both non-Hispanic whites (11%) and Hispanics (9%). Additionally, among adults 65 and older and 75 and older, both Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites showed significant declines in prevalence over the same period, while non-Hispanic blacks did not. Non-poor non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic whites 50 and older showed a significant decline in edentulism prevalence, while non-poor Hispanics did not. However, poor Hispanics (65 and older, and 75 and older) did see significant declines over the same period. Both non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic whites age 50 and older showed significant increases in the prevalence of complete tooth retention, while Hispanics did not. It is important to note that non-Hispanic whites in this age category displayed a substantially higher prevalence of complete dentition than their racial/ethnic counterparts during 2009-2014, especially among the non-poor and near-poor.

Racial/ethnic disparities in edentulism prevalence in older US adults have been widely reported previously. Although our findings indicated that disparities based on race/ethnicity still exists, particularly affecting African Americans, it was encouraging to see that the prevalence of edentulism decreased significantly among non-Hispanic blacks, particularly among the non-poor aged 50-64. Similarly, non-Hispanic blacks aged 50 and older displayed a significant increase in the prevalence of complete tooth retention, driven by those in the 50-64 age group.

Both men and women aged 50 and older showed a significant increase in complete tooth retention prevalence from 1999-2004 through 2009-2014; however, this increase was greater for women. Near poor and non-poor females of all age groups except for those over the age of 75, also experienced significant increases in complete tooth retention prevalence, whereas only non-poor males tended to experience an increase prevalence over the same period. Poor women age 50 and older, were found to have significant increases in the prevalence of functional dentition and mean number of teeth over the 1999-2004 through 2009-2014 time periods, in contrast to poor men who did not. Sex/gender differences seen in edentulism and tooth retention are thought to be related to a complex interplay of genetic, physiological, behavioral, and socioeconomic factors that impact dental diseases and ultimately tooth loss and tooth retention 42. For example, gender differences related to tobacco use, smoking, oral health behaviors, and socioeconomic status are some factors that likely affect edentulism and tooth retention changes that were observed in our study 42,43,44.

Among the factors that are most likely responsible for contributing to the increase in tooth retention and subsequent decrease in edentulism that have been observed, smoking is probably the leading determinant. Smoking, a significant risk factor for periodontal disease (which subsequently increases the risk for eventual tooth loss), has continued to decline over time 11,45. For example, in 1965 the prevalence of smoking was 42.4% and has declined to nearly 15.5% in 2015 11,45. Moreover, there continues to be increase exposure to fluoride at the population-level from a variety of sources, including community water fluoridation, fluoride-containing oral hygiene products, and professionally-applied fluoride products 3,11. Additionally, there has been an emphasis on primary and secondary prevention of oral diseases in general, well-before they lead to irreversible morbidity, such as tooth loss 46. These factors and others, including patients’ increasing desire to retain their natural dentition, likely help explain the improvements in tooth retention measures observed at the population-level.

Edentulism is a global public health issue. It is estimated that at least 4% (276 million) of the global population is edentulous and among the adverse oral health conditions measured by Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, edentulism is the leading cause of DALYs (7.6 million) resulting from an oral condition 5. This substantially impacts quality of life, especially for older adults. An “adequate” dentition is important for well-being and ageing 47 and we used the concept of a “functional dentition” as a proxy for an adequate dentition. There have been many attempts to identify a minimum dentition required to maintain oral function and generally, that number has been around no less than 20 natural teeth remaining 48. As part of an ambitious set of global oral health goals for 2020, the FDI, WHO, and IADR defined a functional dentition as having 21 or more natural teeth 49. The current study presents the first findings on a functional dentition in the US. Although the prevalence of a functional dentition has increased significantly to where more than half of the population age 65 and older currently has a functional dentition, substantial disparities persist by poverty status. The persistence of this large disparity has the potential to contribute to a myriad of significant public health problems as the US population ages.

Our study had several strengths. This included the use of nationally representative data of the United States, study participants were not selected based on any pre-existing conditions, examination methodology was unchanged between both study periods, and examiner reliability and data quality were high. An important limitation of our study was the inability to assess why changes were observed or not observed, but this limitation is common to all cross-sectional studies.

CONCLUSION

Overall, 6.2 million Americans age 50 and older are edentulous. Reflecting backwards, the prevalence of edentulism has declined by more than 75% among adults age 65-74 in the US in the past five decades as the population of older Americans has more than doubled (Fig4) 32,50,51. As edentulism continues to decline among adults age 50 and older, the percent of adults retaining all of their natural teeth continues to increase in the US. With an aging population that is experiencing less edentulism and more tooth retention, older adults may need more regular dental care and prevention services to address concerns such as dental root caries and periodontal disease. Equally important, there are 18.6 million older Americans lacking a functional dentition. Although older Americans have experienced some improvements in their dentate status over the past decade (1999-2004 through 2009-2014), differences persist based on poverty status. Overall, poor older adults continue to experience more natural tooth loss than their counterparts. The changes observed in this study highlight that for many older Americans, important aspects of their oral health continue to improve, but this improvement is not resulting in a substantial reduction in oral health disparities. This suggest that an emphasis on oral health prevention and promotion efforts should focus on poor and racial/ethnic minority older adults to facilitate the reduction of these disparities.

Figure 4.

Estimated total population and prevalence of edentulism among adults 65-74 years of age United States, 1960 to 2014

eFigure 2.

Prevalence of each tooth missing for adults 65-74 years of age with contribution to missing by poverty status: United States, 1999-2004 and 2009-2014

Acknowledgments

Funding Body Agreements & Policy: This research was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) and the authors were paid a salary by the NIH.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement: All study participants gave informed consent in accordance with the Ethics Review Board and study ethic guidelines at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors do not have any financial or other competing interests to declare.

Disclosure. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Bruce A. Dye, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Darien J. Weatherspoon, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Gabriela Lopez Mitnik, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, Bethesda, MD, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ortman J, Velkoff V, Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States. Current Population Reports. 2014. May Available at: https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf. Accessed: February 11, 2018.

- 2.Ahluwalia KP, Cheng B, Josephs PK, Lalla E, Lamster IB. Oral disease experience of older adults seeking oral health services. Gerodontology. 2010. June;27(2):96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffin SO, Jones JA, Brunson D, Griffin PM, Bailey WD. Burden of oral disease among older adults and implications for public health priorities. Am J Public Health. 2012. March;102(3):411–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. http://www.who.int/oral_health/action/groups/en/index1.html

- 5.Kassebaum NJ, Smith AGC, Bernabé E, Fleming TD, Reynolds AE, Vos T, Murray CJL, Marcenes W, GBD 2015 Oral Health Collaborators. 2017. Global, regional, and national prevalence, incidence, and disability adjusted life years for oral conditions for 195 countries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. J Dent Res 96(4):380–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dye BA. The global burden of oral disease: research and public health significance. J Dent Res 2017; 96(4): 361–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson ES, Kelly JE, Van Kirk LE. Selected Dental Findings in Adults by Age, Race, and Sex: United States, 1960-1962. Vital and Health Statistics. Series 11 Report. No. 7. November 1965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dye B, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, Iafolla T. Dental caries and tooth loss in adults in the United States, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2015. May;(197):197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglass CW, Jiménez MC. Our current geriatric population: demographic and oral health care utilization. Dent Clin North Am 2014. October;58(4):717–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman PK, Kaufman LB, Karpas SL. Oral health disparity in older adults: dental decay and tooth loss. Dent Clin North Am 2014. October;58(4):757–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rozier RG, White BA, Slade GD. Trends in Oral Diseases in the U.S. Population. J Dent Educ 2017. August;81(8):eS97–eS109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brennan DS1, Spencer AJ, Roberts-Thomson KF. Tooth loss, chewing ability and quality of life. Qual Life Res 2008. March;17(2):227–35. Epub 2007 Dec 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheiham A1, Steele J. Does the condition of the mouth and teeth affect the ability to eat certain foods, nutrient and dietary intake and nutritional status amongst older people? Public Health Nutr 2001. June;4(3):797–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu Y1, Hollis JH2. Tooth loss and its association with dietary intake and diet quality in American adults. J Dent 2014. November;42(11):1428–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ervin RB, Dye BA. Number of natural and prosthetic teeth impact nutrient intakes of older adults in the United States. Gerodontology. 2012. June;29(2):e693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savoca MR, Arcury TA, Leng X, Chen H, Bell RA, Anderson AM, Kohrman T, Frazier RJ, Gilber GH, Quandt SA. Severe Tooth Loss in Older Adults as a Key Indicator of Compromised Diet Quality. Public Health Nutr 2010; 13(4): 466–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailey RL, Ledikwe JH, Smiciklas-Wright H, Mitchell DC, Jensen GL. Persistent oral health problems associated with comorbidity and impaired diet quality in older adults. J Am Diet Assoc 2004; 104:1273–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahyoun NR, Chien-Lung L, Krall E. Nutritional status of the older adult is associated with dentition status. J Am Diet Assoc 2003; 103:61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheiham A, Steele J. Does the condition of the mouth and teeth affect the ability to eat certain foods, nutrient and dietary intake and nutritional status amongst older people? Public Health Nutr 2001; 4: 797–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshipura KJ, Willett WC, Douglass CW. The impact of edentulousness on food and nutrient intake. J Am Dent Assoc 1996; 127:459–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nowjack-Raymer RE, Sheiham A. Association of edentulism and diet and nutrition in US adults. J Dent Res 2003;82: 123–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nowjack-Raymer RE, Sheiham A. Numbers of natural teeth, diet, and nutritional status in US adults. J Dent Res 2007; 86:1171–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan H, Peres KG, Peres MA. Retention of teeth and oral health-related quality of life. J Dent Res 2016; 95(12): 1350–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haag DG, Peres KG, Balasubramanian M, Brennan DS. Oral conditions and health-related quality of life: a systematic review. J Dent Res 2017; 96(8): 864–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dye BA, Thornton-Evans G. Trends in oral health by poverty status as measured by Healthy People 2010 objectives. Public Health Rep 2010. Nov-Dec;125(6):817–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.aDye BA, Li X, Beltran-Aguilar ED. Selected oral health indicators in the United States, 2005-2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2012. May;(96):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.bDye BA, Li X, Thorton-Evans G. Oral health disparities as determined by selected healthy people 2020 oral health objectives for the United States, 2009-2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012. August;(104):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dye BA, Barker LK, Selwitz RH, Lewis BG, Wu T, Fryar CD, Ostchega Y, Beltran ED, Ley E. Overview and Quality Assurance for the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Oral Health Component, 1999-2002. Community Dentistry Oral Epidemiology 2007; 35: 140–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dye BA, Nowjack-Raymer R, Barker LK, Nunn JH, Steele JG, Tan S, Lewis BG, Beltran ED. Overview and quality assurance for the oral health component of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2003-2004. J Public Health Dent 2008; 68: 218–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dye BA, Li X, Lewis BG, Iafolla T, Beltran-Aguilar ED & Eke PI Overview and quality assurance for the oral health component of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2009-2010. J Public Health Dent 2014; 74: 248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dye BA, Thornton-Evans G, Iafolla T. Overview and Quality Assurance for the Oral Health Component of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2011-2014. Under Review (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2011-2012/analytic_guidelines_11_12.pdf.

- 33.Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, Lewis BG, Barker LK, Thornton-Evans G, Eke P, Beltran-Aguilar ED, Horowitz AM, Li CH. Trends in Oral Health Status—United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Vital Health Stat 11. 2007. April (248): 1–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beltrén-Aguilar ED1, Barker LK, Canto MT, Dye BA, Gooch BF, Griffin SO, Hyman J, Jaramillo F, Kingman A, Nowjack-Raymer R, Selwitz RH, Wu T; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for dental caries, dental sealants, tooth retention, edentulism, and enamel fluorosis--United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2002. MMWR Surveill Summ 2005. August 26;54(3): 1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seerig LM, Nacimento GG, Peres MA, Horta BL, Demarco FF. Tooth loss in adults and income: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2015. September;43(9):1051–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: a Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang DL, Park M. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic oral health disparities among US older adults: oral health quality of life and dentition. J Public Health Dent 2015. Spring;75(2):85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JY, Divaris K. The ethical imperative of addressing oral health disparities: a unifying framework. J Dent Res 2014. March;93(3):224–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tiwari T, Scarbro S, Bryant LL, Puma J. Factors Associated with Tooth Loss in Older Adults in Rural Colorado. J Community Health. 2016. June;41(3):476–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vujicic M, Buchmueller T, Klein R. Dental care presents the highest level of financial barriers, compared to other types of health care services. Health Aff 2016; 35: 2176–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vujicic M. Our dental care system is stuck: And here is what to do about it. JADA 2018; 149: 167–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russell SL, Gordon S, Lukacs JR, Kaste LM. Sex/Gender differences in tooth loss and edentulism: historical perspectives, biological factors, and sociologic reasons. Dent Clin North Am 2013. April;57(2):317–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jette AM, Feldman HA, et al. Tobacco use: a modifiable risk factor for dental disease among the elderly. Am J Public Health 1993; 83(9): 1271–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krall EA, Dawson-Hughes B, et al. Smoking, smoking cessation, and tooth loss. J Dent Res 1997; 76(10): 1653–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm.

- 46.Mount GJ. A new paradigm for operative dentistry. J Conserv Dent 2008. January;11(1):3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Emami E, de Souza RF, Kabawat M, Feine JS. The impact of edentulism on oral and general health. Int J Dent 2013; https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijd/2013/498305/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gotfredsen K, Walls AW. What dention assures oral function? Clin Oral Implants Res 2007;Suppl 3: 34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hobdell M, Petersen PE, Clarkson J, Johnson N. Global goals for oral health 2020. Int Dent J 2003; 53: 285–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kelly JE, Van Kirk LE, Garst C. Tooth loss of teeth in adults, United States – 1960-1962. Vital Health Stat 11. 1967. October(27):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kelly JE, Harvey CR. Basic data on dental examination findings of persons 1-74 years. United States, 1971-1974. Vital Health Stat 11. 1979. May(214):1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]