Abstract

Purpose

To identify the qualitative evidence on the experience of cancer and comorbid illness from the perspective of patients, carers and health care professionals to identify psycho-social support needs, experience of health care, and to highlight areas where more research is needed.

Methods

A qualitative systematic review following PRISMA guidance. Relevant research databases were searched using an exhaustive list of search terms. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts and discussed variations. Included articles were subject to quality appraisal before data extraction of article characteristics and findings. Thomas and Harden’s thematic synthesis of extracted findings was undertaken.

Results

Thirty-one articles were included in the review, covering a range of cancer types and comorbid conditions; with varying time since cancer diagnosis and apparent severity of disease for both cancer and other conditions. The majority of studies were published after 2010 and in high income countries. Few studies focused exclusively on the experience of living with comorbid conditions alongside cancer; such that evidence was limited. Key themes identified included the interaction between cancer and comorbid conditions, symptom experience, illness identities and ageing, self-management and the role of primary and secondary care.

Conclusions

In addition to a better understanding of the complex experience of cancer and comorbidity, the review will combine with research prioritisation work with consumers to inform an interview study with the defined patient group.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Expanding this evidence base will help to illuminate developing models of cancer patient-centred follow-up care for the large proportion of patients with comorbid conditions.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11764-019-0734-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Comorbidity, Systematic review, Qualitative, Supportive care, Cancer experience, Survivorship care

Introduction

Macmillan Cancer Support estimates that there are now 2.5 million people living with and beyond cancer in the UK, and this figure is expected to rise to 4 million by 2030 [1], explained, in part, by the ageing population, and improved screening, earlier diagnosis and better treatments. Deborah Boyle insightfully described the changing ‘cancer patient mosaic’, and the reality is that most people living beyond cancer are living with additional comorbid illness [2]. As many as 78% of cancer patients report at least one other condition, and such multi-morbidity also increases with age [3, 4]. A recent study suggested that cancer survivors had an average of five comorbid conditions, with some of these developing after cancer diagnosis [5]. Commonly reported comorbid conditions among cancer survivors included heart- and lung-related illnesses, ear and eye problems, hypertension, arthritis or rheumatism and depression and anxiety [5, 6]. Prevalence and comorbidity type varied according to time since diagnosis and cancer type, as well as associations with ethnicity, marital status, weight and physical activity [5]. Evidence suggests that the presence of comorbid conditions among those diagnosed with cancer is associated with poorer survival and quality of life, due to increased symptom burden, being less likely to receive treatment with curative intent and these patients are often excluded from clinical trials [7].

Psychosocial support for cancer survivors has become an increasing priority on the policy agenda over the last 10 years, as evidenced by a recent Lancet Oncology paper series devoted to cancer survivorship [8]. In the UK, this policy priority was set out in the Cancer Reform Strategy, which in turn led to the development of the National Cancer Survivorship Initiative in England and Wales [9, 10], and forms part of the remit for Scotland’s Better Cancer Care [11].

Follow-up care and psychosocial support for survivors of cancer presents challenges to health care services [12] and has implications for the role of primary, secondary and community care as new models of follow-up are recommended [13, 14]. This picture becomes more complex in the presence of comorbidities, with implications for the coordination of quality care and support [15, 16]. While valuable research has been conducted to understand the experience of living with and beyond cancer for the patient [10, 17], and their relatives [18–22], less is known about the impact of additional chronic illness. Research exploring the support needs of people living with multiple complex conditions, including cancer, therefore needs to be identified [23]. Service development and provision would also benefit from insights in this area, in order to highlight areas for further research [17, 24].

Aims and research questions

Understanding the challenges experienced by people living after a cancer diagnosis with other chronic conditions such as COPD, diabetes or mental ill health, can give new insights into patient-centred models of care. A systematic review approach provides a comprehensive process to explore the current evidence base and define a research agenda building on prior knowledge [25]. This systematic review aimed to identify and synthesise qualitative evidence on the experience of living with and beyond cancer with one or more additional long-term illnesses. Insights from the review will inform further research in this area. The review seeks to answer the following questions:

What qualitative evidence is available that explores the experience of living with both cancer and one or more comorbidities from patient, carer and provider perspectives?

What are the psychosocial support needs of people living with cancer and one or more comorbidity as identified in the literature?

What are patient, carer and provider experiences of service provision for cancer and comorbid conditions reported in the literature and what research priorities can be derived from the available evidence?

Methods

The review methods are detailed in full in a published protocol [26]. The methods are summarised below. The review protocol is registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database (registration number: CRD42016041796).

Design and ethics

A review of qualitative papers was chosen to fit with the aim of exploring people’s experiences, using a person-centred approach to highlight context and generate meaningful and relevant findings [27]. The review used methods of qualitative synthesis to combine, integrate and interpret, where possible, the evidence from the included papers [27, 28]. The review aimed to move beyond the aggregation of available data to provide further interpretive insights into living with complex illness and define where future research can add to what is known [28].

The review method follows the PRISMA statement guidance for conducting a systematic review [29].

This review was exempt from NHS and internal University of Edinburgh Usher Institute for Population Health Sciences and Informatics Ethics Review Committee because no primary data was used.

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included if they were published in English between January 2000–January 2017 to capture the current survivorship agenda while allowing for a broad view of issues as they have developed. Eligible articles included wholly qualitative studies and the qualitative component of mixed methods studies (including unpublished literature) addressing the topic of psychosocial dimensions of living with cancer and comorbid illness (diagnosed before or after the cancer diagnosis but not directly caused by the cancer), including issues of support and experience of service provision from diagnosis to end of life. Adult patients (18 years or over), informal carer and health care professional perspectives were included.

Any cancer type was included along with any comorbidity (as defined by the ISD Scotland report [30]) and listed in Barnett et al.’s paper mapping the epidemiology of multi-morbidity [4], listed in Online Resource 1. Long-term side effects of cancer treatment and second primary cancers were not included. See Online Resource 2 for a summary of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Dimensions of interest

The review includes physical, social, emotional, psychological and spiritual dimensions of experience of cancer and comorbidity. Full details of the review topic can be found in the study protocol [26].

Information sources

Literature was identified using a variety of methods, including database searching, citation and snowball searching, known expert consultation via email and related articles searches in PubMed and Google scholar. The databases consulted were Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ASSIA, Sociological Abstracts, Web of Science, SCOPUS and, for grey literature, OpenGrey and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Search strategy

A broad search strategy was developed to reflect the exploratory nature of the review (see Online Resource 3 for an example search strategy for Medline, adapted to each database using free text, MeSH and subject headings where possible for maximum sensitivity and specificity).

Data collection and analysis

Study records and screening

Identified records were imported into EndNoteX7 and managed in subsequent databases to track the number of records at each stage of the screening process. Two reviewers (DC and LH) screened articles in three stages: title, abstract and full text. A third reviewer (CC) screened a proportion of articles and discrepancies were discussed and resolved by the third reviewer.

Quality assessment

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool was used to assess the quality of the included studies as it was considered an appropriate tool for qualitative studies and is widely used (www.casp-uk.net). DC, LH and MD carried out critical appraisal and discussed any discrepancies of one point or more on the 10-point scale. The overall quality of the included studies was appraised as good, with scores ranging from 5.5 to 10. A summary of the quality appraisal is shown in Online Resource 4. No articles were excluded on the basis of poor quality. Findings were interpreted in the context of the quality markers and corresponding limitations of the included studies.

Data extraction

Data was extracted by DC and LH from included studies into a Microsoft Excel proforma, including: author; year of publication; country of study; study type; setting; relevant background and impetus for the study; methodological approach and specified methods; patient characteristics and demographics including cancer and comorbidity type; main findings relating to illness experience, psychosocial needs and supportive care; strengths and limitations and key relevant discussion points.

Data synthesis

Thematic synthesis, developed by Thomas and Harden, was chosen as an appropriate, transparent method for combining and interpreting qualitative findings [27, 28] (see protocol for full details on the chosen approach) for a heterogeneous body of evidence. This method allowed comparison of concepts and themes that relate different studies and uses a similar approach to developing descriptive themes and an interpretive account, as a grounded theory approach does with primary data analysis [31, 32].

Patient and public involvement

A consumer member of the research team (EB) was involved in the design and implementation of the systematic review, commenting and helping to shape the protocol and search strategy for the study, the synthesis and the paper drafting.

Findings

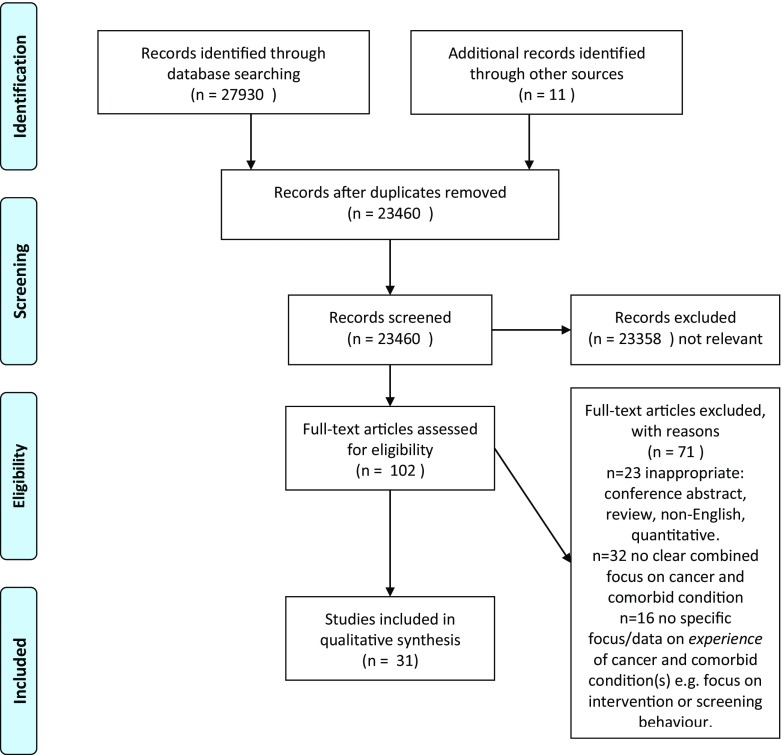

Thirty-one articles were included in the final review [23, 33–62], based on 28 independent studies from an original yield of 27,941 papers identified through searching, reference snowballing, related articles and expert recommendation. The full screening process is outlined in the PRISMA flowchart in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). The characteristics of the 31 included papers can be found in the characteristics of included studies (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author (year) | Country of study/setting | Study type/method used | Study focus | Subjects/gender (N) | Age of subjects | Analysis/theoretical underpinnings reported | Cancer type (years since diagnosis) | Comorbid illness(es) reported | Themes evidenced in article |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker [33] 2015 | USA | QL/in-depth semi-structured interviews at two time points | Clinical care providers’ views on survivors’ weight management | Professionals: oncologists, surgeons, PCPs, nurses, dieticians. (N = 33) | ? | Constant comparative analysis | Prostate, breast, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (years not reported) | Diabetes, hypertension | 1, 2, 4, 5 |

| Bartlett [34] 2012 | UK | QL/in-depth interviews | Health professional views on needs assessment and communication with cancer patient with dementia | Healthcare professionals (N = 5) | ? | Heidegger’s phenomenological approach | Not reported; professional interviews | Dementia | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Beck [35] 2009 | USA | Mixed/interviews and psychometric tests | Symptom experience, QoL and functional performance of cancer survivors at 1 and 3 months post-treatment | Male and female cancer patients (N = 52) | 65+ | Not reported | All—most common breast and prostate (1 and 3 years after diagnosis) | Arthritis, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, lung disease, neuromuscular disease | 1, 2, 3, 5 |

| Clarke [36] 2013 | Canada | QL/semi-structured interviews at two time points | Experience of multiple conditions in later life and influence of gender and age. | Male and female patients with multi-morbidity (N = 35) | 73+ | Patton’s thematic analysis | Not clearly reported (one bladder cancer) | Arthritis, back pain, heart disease, COPD | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Corner [37] 2013 | UK | Mixed/QL free text comments analysis | How free text comments on PROMs added to understanding of QoL issues for survivors | Male and female cancer patients (N = 1056) | Over 16 | Content analysis | Breast cancer, colorectal cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, prostate cancer (1–5 years) | Hypertension, arthritis, osteoporosis, back pain | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Courtier [38] 2016 | UK | QL/case studies | Outpatient experiences of patients with dementia and oncology management | Male and female cancer/dementia patients and five HCPs (N = 16) | ? | Wolcott’s framework for qualitative data analysis | Breast cancer, prostate cancer, head and neck cancers, pelvic cancer, colorectal (years not reported) | Dementia | 1, 3, 4, 5 |

| Dahlhaus [39] 2014 | Germany | QL/semi-structured telephone interviews | German GPs’ views on involvement in patients’ cancer care | Male and female GPs (N = 30) | ? | Mayring’s qualitative content analysis | Any professional interviews | Dementia, hypertension | 5 |

| Fenlon [40] 2013 | USA | QL/in-depth semi-structured interviews | Lived experience, support and information needs of breast cancer patients with comorbid illness | Male and female patients (N = 48, 43 are male) | 70–90 years | Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis | Breast cancer (up to 10 years) | Cardiac conditions, arthritis, hypertension, diabetes | 1, 2, 3, 5 |

| Fix [41] 2014 | USA | QL/longitudinal interviews | Hypertension self-management in patients with comorbidities | Male and female patients (N = 48, 43 are male) | Mean age 60 years | Grounded theory approach; Kleinman’s explanatory model as a framework | Prostate cancer, renal cancer (years not reported) | Hypertension, anxiety, arthritis, back pain, cardiovascular disease, COPD, depression, glaucoma, Parkinson’s disease | 1, 2, 4, 5 |

| Hannum [42] 2016 | USA | QL/longitudinal interviews | Narratives of cancer among chronically ill older adults | Male and female patients (N = 16, 13 are female) | 65 and over | Thematic analysis based on symbolic interactionism, constructivism and phenomenology | Breast, colon, brain, endometrial, oesophageal, GIST, large B cell lymphoma, pancreatic, stomach (within 1 year) | Diabetes, glaucoma | 2, 3 |

| Hershey [43] 2012 | USA | Mixed/phone survey with two open-ended questions | Impact of cancer and its treatment on diabetes self-management | Male and female patients (N = 37) | 50 and over | Qualitative content analysis | Breast, lung and pancreas (years not reported) | Diabetes (type I and II) | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Kantsiper [44] 2009 | USA | QL/focus group interviews | Needs and priorities of breast cancer patients, oncologists and PCPs. | Female patients; male and female professionals (N = 52) | ? | Qualitative thematic analysis | Breast (1 year or more) | Diabetes, hypertension, renal issues | 5 |

| Loerzel [45] 2012 | USA | QL/semi-structured interviews | Understanding post-treatment survivorship in older women with breast cancer | Female patients (N = 20) | 65–86 years | Grounded theory approach and analysis | Breast (within 1 year) | Fibromyalgia, arthritis | 1, 2, 3 |

| Loerzel [46] 2013 | USA | QL/semi-structured interviews | Understanding post-treatment survivorship in older women with breast cancer | Female patients (N = 20) | 65–86 years | Grounded theory approach and analysis | Breast (within 1 year) | Fibromyalgia, arthritis | 2, 3 |

| Mason [23] 2014 | UK | QL/in-depth serial interviews | Experience of advanced multi-morbidity and implications for palliative and end of life care | Male and female patients and carers (N = 37) | 55–62 years (mean 76) | Thematic analysis; constructionist approach | Lung (years not reported) | Heart disease, respiratory, liver, renal failure, neurological conditions, dementia | 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Morgan [47] 2015 | UK | QL/in-depth serial interviews | Experience of advanced multi-morbidity and implications for palliative and end of life care | Male and female patients and carers (N = 37) | 55–62 years (mean 76) | Thematic analysis; constructionist approach | Breast; professional interviews | Dementia and others non-specified | 1, 5 |

| Nanton [48] 2016 | UK | QL/in-depth serial interviews | To examine the impact of uncertainty on identity in people with advanced multi-morbidity and the role of HCPs and health systems | Male and female patients and carers (N = 37) | 41–92 years | Thematic analysis; based on social constructionism and ethnography | Lung, prostate (years not reported) | Stroke, ischaemic heart disease, dementia, osteoarthritis, hypertension | 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Norman [49] 2001 | Canada | QL/semi-structured interviews | Palliative care patients’ relationships with their family physicians | Male and female patients (N = 25) | 28–84 years | Grounded theory approach | 12 types of cancer (1 month-12 years) | Diabetes | 5 |

| Palmer [50] 2011 | USA | Mixed/survey and interviews | Health-related goals of post-treatment colorectal cancer survivors | Male and female patients (N = 41) | 33–87 years | Unclear; thematic analysis described | Colorectal (within 2 years) | Diabetes, chronic pain | 2, 3, 4 |

| Palmer [51] 2013 | USA | QL/semi-structured interviews | Health-related goals of post-treatment colorectal cancer survivors | Male and female patients (N = 41) | 33–87 years | Content analysis | Colorectal (within 2 years) | Diabetes, chronic pain | 2, 4 |

| Sada [52] 2011 | USA | QL/semi-structured interviews | PCP and oncologists’ roles and communication in shared care of cancer patients | Male patients, male and female professionals (N = 24) | 40–80+ | Unclear; some form of thematic analysis | Colorectal (within 2 years) | COPD, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and others non-specified | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Saunders-Sturm [31] 2003 | USA | QL/semi-structured interviews | Lived experience of breast cancer | Female patients (N = 33) | 47 years and over | Grounded theory approach; social constructionist | Breast (18 months-4 years) | Arthritis, asthma, chronic bronchitis, high blood pressure and diabetes | 2, 3, 4 |

| Sawin [54] 2012 | USA | QL/semi-structured interviews | Ageing related experiences of women with breast cancer in unsupportive relationships | Female patients (N = 16) | 50–84 years (mean 68.1) | Hermeneutic phenomenological analysis | Breast (1–31 years; mean 7.4) | Hypertension, chronic pain, COPD | 1, 2, 3 |

| Sinding [55] 2008 | Canada | QL/semi-structured interviews at two time points | Older women’s experiences of cancer | Female patients (N = 15) | 70 years and over | Grounded theory approach and analysis | Breast and gynaecological (within 3 years) | Diabetes, Chrohn’s disease, ‘mental illness’ | 1, 2, 3 |

| Sowerbutts [56] 2015 | UK | QL/in-depth interviews | Surgery decisions in older women with breast cancer | Female patients (N = 28) | 70–99 years | Framework analysis | Breast (within 30 days) | Non-specified | 1, 3, 5 |

| Thomé [57] 2003 | Sweden | QL/interviews | Experiences of older people living with cancer and its impact on daily life | Male and female patients (N = 64) | 76–99 years (mean 87) | Latent content analysis | Breast, prostate, gastro, gynae, urogenital, skin, lung/larynx, haematological |

Within 5 years | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Volker [58] 2013 | USA | QL/focus group interviews | Cancer diagnosis for people with pre-existing functional limitations and topics for a wellness intervention programme | Female patients (N = 19) | 21 and over (mean 59.5) | Patton’s qualitative content analysis | Breast, colorectal, bladder, gynae, melanoma, thyroid, kidney (10 years on average) | Arthritis, multiple sclerosis | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

| Wallace [59] 2015 | USA | QL/semi-structured interviews at two time points | Treatment experiences of newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients and influence of age and time | Male and female patients (N = 41, 32 are male) | 45–91 (mean 58.4) | Cresswell’s qualitative analysis; based on socio-emotional selective theory and Leventhal’s self-regulation model | Head and neck (within 2 weeks) | Heart disease, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, COPD, arthritis, fibromyalgia, liver failure | 3, 4, 5 |

| Wimberley [60] 2012 | USA | QL/in-depth serial interviews | Influence of breast cancer on women’s meanings, understanding and self-identities over time. | Female patients (N = 15) | 41–76 years (mean 59.4) | Hermeneutic analysis; phenomenological underpinnings | Breast (5–25 years) | Scleroderma and hypothyroidism | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Yoo [61] 2010 | USA | QL/in-depth interviews | Psychosocial impact of breast cancer and social support for older women | Female patients (N = 47) | 65–83 years | Grounded theory approach and analysis | Breast (within 4 years) | Heart disease and others non-specified | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Zhang [62] 2015 | USA | Mixed/psychometric test and interviews | Universal and unique depressive symptoms in African American cancer patients | Male and female patients (N = 74) | Mean 62 years | Unclear; thematic analysis described | Not reported | Depression | 2 |

The identified papers represented a heterogeneous range of studies including different cancer and comorbidity types. The majority of studies did not focus on the experience of cancer and comorbidity. It was often the case that comorbid conditions were mentioned briefly in relation to another issue, with only small amounts of qualitative data and limited discussion of specific issues relating to cancer and comorbidity. A small number of studies focused mainly on the experience of comorbidity or multi-morbidity and cancer was considered tangentially. Studies were largely exclusively qualitative, with five mixed methods papers, and include three PhD theses. Qualitative studies primarily used interviews (including longitudinal interviews), with a small number of focus group studies and one paper including case studies and observations. Two quantitative surveys included free-text comments.

The majority of studies were published from 2010 onwards, with only five included studies published prior to this. Papers were mostly published from high-income countries. The majority were US-based, followed by the UK, Germany, Sweden and Canada. Researchers came from a number of different disciplines, settings and health systems, all of which influence their approach, reporting style and thus the extent to which the results can be synthesised.

Studies were mostly set in secondary care hospitals, specialist clinics or specialist cancer centres; others included primary and community care settings (not all studies specified where participants were recruited from). The majority of studies included patient perspectives and two also included informal carer interviews. Six studies included health professional perspectives (two of these alongside patient interviews): three primary care and three specialist views.

Nine studies focused exclusively on breast cancer. Other common cancers included were prostate, lung, colorectal and lymphoma. Three studies did not specify a cancer type whereas others non-specifically reported on ‘any’ cancer type. Comorbid conditions were mostly reported in general but three studies focused on exclusive conditions: diabetes, dementia and depression. Common examples of other comorbid conditions featured were cardiac conditions including hypertension, arthritis, chronic pain, lung/respiratory conditions and stroke.

There was variation of stage and severity of cancer and/or comorbid condition, and in time since original diagnosis (depending on the aims and objectives of the included studies) such that experience could be expected to vary considerably depending on these characteristics, limiting opportunity for synthesis. It was important to consider these variations when interpreting differences in findings.

The total number of participants in a study ranged from five to 1056 (free-text comments from a survey of 3300 [37]. Eleven papers looked at women only; the rest included both men and women apart from one study with health professionals which did not specify gender. Experience of ageing in the context of illness was a key issue (mentioned in 11 papers), although interpretation of ‘older’ varied considerably from 50+ to 70+ with included participants in their late 90s so experiences were likely to vary extensively.

Studies varied considerably in their reporting of theoretical underpinnings and epistemology. Some described analysis without referring to a theoretical or methodological approach and only a few studies gave more detailed accounts of their theoretical stance and the methodological coherence.

Synthesis

Five themes emerged from the analysis. The themes relating to each included study are listed in column 10 of Table 1.

Interaction and impact of cancer and comorbidity

The interaction of having cancer and additional chronic illness reportedly produces a complex and increased burden of ill health for many,

‘They're morbidly obese, they have heart disease, diabetes, they all have orthopedic issues... breast cancer's just one thing’. (Nurse navigator, [33])

There is an indication in the literature reviewed that this complexity influences not only quality of life, and recovery (e.g. Corner et al. [37]), but also treatment decisions,

‘I could not have [general anaesthetic] because it affects my heart, you see’. (Patient 23, [56])

‘If you have got umm a person with reduced mental capacity [because of dementia] living on their own then the safety of giving chemotherapy is a risk’. (Oncologist, [38])

Symptom experience

Related to interaction and impact of cancer and comorbidity, experiencing additional chronic ill health as well as cancer brought about a complex symptom burden that appeared to be mediated by stage and severity as well as proximity to diagnosis of the cancer and/or comorbidity. Evidence varied to suggest that some patients prioritised one condition over another; whereas, for others, they appeared to be entwined. Participants in some studies described cancer as merely a ‘bump in the road’; whereas, for others, the symptoms and effects were more enduring. For some, complexity of disease led to a blurring of symptoms and an inability to attribute symptomology to a particular condition; a source of fear of the cancer returning,

‘Dr C said that he doesn't really feel that I got too much to worry about, that they got it in time, but then how do they know if they got everything? ...And when my lungs are bad [asthma], it frightens you’. (Judith, [55])

Illness expectations and identity

Ability to adjust and cope with a complex burden of ill health was influenced by past experience of illness (including sequencing of conditions, i.e. whether the cancer or the comorbid condition came first) as well as notions of ageing and expectations of ailing health and functional ability. Expecting illness with advancing age helped to ‘lessen the shock’ of cancer diagnosis for some participants in the included studies [45], captured by those participating in Mason et al as ‘old not ill’ [23].

Maintaining a sense of control and one’s existing personal identity appeared to be an important part of illness experience for participants in many included studies,

‘One feels sorry for oneself, in the sense that one loses one's independence and you become dependent on others’. (91 year old patient with back problems, cancer, heart disease and other conditions, [36])

Managing medications and self-management

A smaller number of studies referred to managing medications as being a challenge for people living with cancer and other chronic illness at the same time. In addition to issues such as being refused trial participation due to contraindicated medications and the financial cost of medications in relevant health systems, one of the concerns raised was the ability to self-manage the range of medications needed. Patients also had to look out for contraindications as the communication between primary and secondary care or between different specialists was not always optimal, meaning the patient often had to champion their position,

‘The fact that I'm on this pain control regimen, doctors wanted to ignore it, he didn't want to deal with someone on Fentnyl patch and Oxycodone, just didn't want to deal with that. So if you don't advocate for yourself, forget it...sometimes you get tired of fighting for yourself and trying to educate everybody’. (Cancer patient, [58])

In terms of self-management, studies emphasised the need for shared care or supported self-management (including looking after overall health and well-being), and the need for resources to enable this and to take the pressure off primary care in providing follow-up care and support for this patient group.

Role of primary and secondary care

The evidence suggests that oncologists do not often see the management of comorbid conditions as being part of their role or within their perceived level of competency. GPs were more likely to regard holistic condition management as part of their role and advocated a patient-centred ‘joined up’ approach. For example, a medical oncologist interviewed by Sada et al. said:

‘I encourage patients to continue the management of their [chronic illness] with their PCP...I'm so subspecialised that I don't really feel comfortable managing [it]’. (Medical oncologist 6, [52])

However, primary care practitioners did not always feel comfortable managing advanced cancer symptoms, potentially leading to a fragmented experience of care, as another study suggests:

‘[The FP (family physician) is] still looking after their diabetes…One kind of doctor does this; he does that: [to] each their own. Symptom control is not in their hands…You leave that to the specialists. She’s just a family physician’. (Cancer patient, [49]).

Managing cancer multi-morbidity in primary care carries many challenges:

‘…Actually most of our patients have five or six issues, and so we’re trying to manage their diabetes or hypertension or renal insufficiency and then end up with a breast issue, and it’s impossible…that’s like more than an hour’s worth of time where you have like four patients scheduled in 15-min increments, and it’s overwhelming’. (Primary Care Professional, [44])

Discussion

Summary

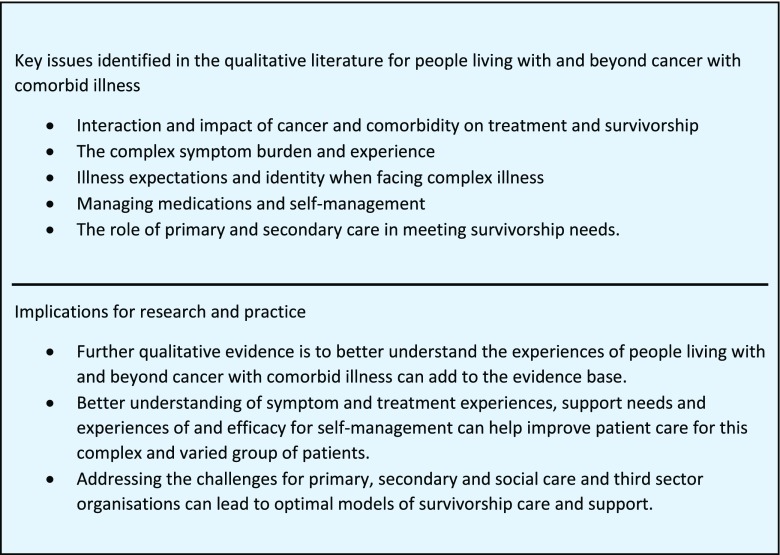

This systematic review of the evidence relating to the experience of living with and beyond cancer with comorbid illness identified a small number of heterogeneous papers with a range of aims and perspectives. Qualitative data on this specific topic was difficult to identify as comorbidities were often mentioned in passing or ‘buried’ in articles with a different dominant focus. From the 31 included studies, a number of themes emerged to give a summary of the current evidence and help identify topics for further investigation (see Fig. 2). These issues relate to the burden of symptoms, the combined impact on one’s illness experience and how adjustment was entwined with previous experience of illness, illness expectations and the severity of the illness burden. Dealing with polypharmacy, self-managing and the related challenges and demand for health services, including the relationship between primary and specialist care, were also identified as important concerns. Overall, there is need to grow the evidence base on this topic, in order to address the support needs of the growing number of cancer survivors living with other chronic conditions, their informal carers and health care professionals.

Fig. 2.

Identified issues and implications for research and practice

Place in the wider literature

The findings from the review sit within a wider literature examining experiences of cancer survivors and the role for primary and secondary care, as well as literature around multi-morbidity, e.g. [20, 63–68]. There have been a number of intervention studies to support patients living with and beyond cancer [69, 70], and to consider the views of health care providers [21, 71]. There is also a recognition that guidance is needed for a model of survivorship care that acknowledges the challenges for and complexity of this patient group, including measuring comorbid conditions and managing them in the treatment and survivorship contexts [12, 13, 72].

A number of potential theoretical positions may provide insight to the emergent themes from the synthesis. Indeed, a small number of included studies refer to theory in order to make sense of their findings. For example, issues of symptom burden and people’s illness expectations and identity relate to experience of illness theory around keeping illness at the boundaries of one’s self concept in an attempt to maintain one’s existing personal identity (Charmaz 2000) and can be understood in the context of biographical disruption, flow and continuity [73, 74] and Frank’s illness narratives [75]. Further in-depth research can revisit the potential contribution of these theoretical insights to the experience of cancer and comorbid illness.

The issue of the pressure on primary care to manage cancer survivor follow-up and for patients to self-manage is one that has been problematised in the sociological literature, marking a shift toward ‘living with and beyond cancer’. It is argued that the term ‘survivor’ is heavily loaded with expectations of optimism in ‘fighting’ the cancer battle with an emphasis on individual responsibility and accountability for lifestyle change and secondary prevention [76, 77], with implications for the ‘burden of treatment’ work expected of patients and their families, and with repercussions for health services [78].

Strengths and limitations

This review brings together studies exploring experience of illness. It focuses on qualitative findings to meet the aims of identifying contextual evidence of psychosocial issues and supportive care needs.

The articles included in the review come from differing settings and foci. Due to the broad exploratory nature of the topic, it was difficult to design a search strategy that was sensitive and specific. Given the ‘snippets’ of qualitative data relating to the topic of cancer and comorbid illness, there may be additional articles containing relevant data that were not identified. Additional methods of snowball referencing and related articles searching as well as expert consultation were undertaken to address this potential limitation. Also, despite the heterogeneity of the studies, it was possible to deduce some common themes, suggesting that a diverse sample of papers from a number of different settings can enable a level of conceptual saturation of ideas [79], and remains true to the aim of producing an abstract synthesis that is ‘faithful to the group of studies from which it was extracted’ [80].

The research agenda

While multi-morbidity in cancer survivors is often highlighted as a key issue in literature and policy, qualitative research to date has yet to focus on it as a substantive concern. Reviewing the qualitative evidence on this topic has identified key themes that warrant further exploration and focus. Variations in symptoms burden and the interaction and impact on one’s illness experience have been indicated in the included studies. Further, qualitative work is needed to explore the influence of stage of survivorship, severity of the concomitant illnesses and the meaning attributed to cancer in relation to other chronic conditions. The challenges for health services have been identified in the literature: there is a call for further work to better understand the difficulties facing primary and secondary care in managing survivorship care in the context of multi-morbidity and what patients want from services in this context. Finally, carers’ views have been largely under-represented and it is important to explore the additional strain that caring for someone with cancer and additional chronic conditions imposes. These issues have also emerged from research prioritisation work carried out by the authors in relation to this topic (in draft), as well as the wider context of the recent National Cancer Research Institute Top 10 research priorities for living with and beyond cancer (www.NCRI.org.uk/lwbc), and have combined to inform the design (including aims, sampling decisions and interview topic guide) of an in-depth, multi-perspective interview study with patients, carers and health care professionals.

Conclusions

Further, qualitative evidence is required to understand better symptom experience, stage, severity and proximity to diagnosis of disease, views on and experiences of current care, support for self-management and the role of primary and secondary care, as well as carer experiences, to develop optimal care for the complex needs of this growing and diverse group of cancer survivors.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 337 kb)

(PDF 486 kb)

(PDF 449 kb)

(PDF 402 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Meghan Davies for her help with quality appraisal and Marshall Dozier (University of Edinburgh Academic Librarian) for her help in developing the search strategy and terms. We thank academic experts in the field who suggested potential papers for inclusion in the review: Marjan van den Akker, Camilla Hoffman-Merrild, Gill Hubbard, Larissa Nekhlyudov, Diane Sarfati, Jeannine Stairmand, Peter Lewis and Annette Berendsen.

Funding

This review was funded by the Chief Scientist’s Office, ref. number PDF/15/06.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving humans participants and/or animals

No human or animal participants were involved in this study.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not necessary as no human subjects were involved in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Maddams J, Utley M, Møller H. Projections of cancer prevalence in the United Kingdom, 2010-2040. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1195–1202. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle D. In: Bush NJ, Gorman L, editors. Survivorship, in Psychosocial Nursing Care Along the Cancer Continuum: Oncology Nursing Society; 2018. p. 27–41.

- 3.McLean G, Gunn J, Wyke S, Guthrie B, Watt GCM, Blane DN, Mercer SW. The influence of socioeconomic deprivation on multimorbidity at different ages: a cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(624):e440–e447. doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X680545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leach CR, Weaver KE, Aziz NM, Alfano CM, Bellizzi KM, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Rowland JH. The complex health profile of long-term cancer survivors: prevalence and predictors of comorbid conditions. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(2):239–251. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams GR, Deal AM, Lund JL, Chang YK, Muss HB, Pergolotti M, Guerard EJ, Shachar SS, Wang Y, Kenzik K, Sanoff HK. Patient-reported comorbidity and survival in older adults with cancer. Oncologist. 2018;23(4):433–439. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarfati D, Koczwara B, Jackson C. The impact of comorbidity on cancer and its treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):337–350. doi: 10.3322/caac.21342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayer DK, Nasso SF, Earp JA. Defining cancer survivors, their needs, and perspectives on survivorship health care in the USA. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):e11–e18. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30573-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health, Cancer reform strategy 2007.

- 10.NHS Health Improvement and Macmillan Cancer Support, National Cancer Survivorship Initiative: Vision. 2010.

- 11.Scottish Government . Better Cancer care: an action plan. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs LA, Shulman LN. Follow-up care of cancer survivors: challenges and solutions. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):e19–e29. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30386-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nekhlyudov L, O'Malley DM, Hudson SV. Integrating primary care providers in the care of cancer survivors: gaps in evidence and future opportunities. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):e30–e38. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith SM, Allwright S, O'Dowd T. Does sharing care across the primary-specialty interface improve outcomes in chronic disease? A systematic review. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(4):213–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snyder CF, Frick KD, Herbert RJ, Blackford AL, Neville BA, Lemke KW, Carducci MA, Wolff AC, Earle CC. Comorbid condition care quality in cancer survivors: role of primary care and specialty providers and care coordination. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(4):641–649. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0440-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams GR, et al. Comorbidity in older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, Hudon C, O'Dowd T. Managing patients with multimorbidity: systematic review of interventions in primary care and community settings. Bmj. 2012;345:e5205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison SE, Watson EK, Ward AM, Khan NF, Turner D, Adams E, Forman D, Roche MF, Rose PW. Primary health and supportive care needs of long-term cancer survivors: a questionnaire survey. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(15):2091–2098. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams E, Boulton M, Rose PW, Lund S, Richardson A, Wilson S, Watson EK. A qualitative study exploring the experience of the partners of cancer survivors and their views on the role of primary care. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(11):2785–2794. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1400-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watson EK, Rose PW, Loftus R, Devane C. Cancer survivorship: the impact on primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(592):e763–e765. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X606771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson EK, et al. Views of health professionals on the role of primary care in the follow-up of men with prostate cancer. Fam Pract. 2011;28(6):647–654. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien R, Wyke S, Guthrie B, Watt G, Mercer S. An ‘endless struggle’: a qualitative study of general practitioners’ and practice nurses' experiences of managing multimorbidity in socio-economically deprived areas of Scotland. Chronic Illn. 2011;7(1):45–59. doi: 10.1177/1742395310382461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason B, et al. My body’s falling apart. Understanding the experiences of patients with advanced multimorbidity to improve care: serial interviews with patients and carers. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.France EF, Wyke S, Gunn JM, Mair FS, McLean G, Mercer SW. Multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(597):e297–e307. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X636146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemingway P, Brereton N. What is a systematic review? In: What is...? series: Haywood Medical Communications; 2009. p. 1–8.

- 26.Cavers D, et al. Experience of living with cancer and comorbid illness: protocol for a qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e013383. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Information Services Division . Measuring long term conditions in Scotland. Scotland: NHS National Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research: Sociology Press; 1967.

- 32.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. 2nd ed: SAGE; 2013.

- 33.Baker AM, Smith KC, Coa KI, Helzlsouer KJ, Caulfield LE, Peairs KS, Shockney LD, Klassen AC. Clinical care providers’ perspectives on body size and weight management among long-term cancer survivors. Integr Cancer Ther. 2015;14(3):240–248. doi: 10.1177/1534735415572882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartlett A, Clarke B. An exploration of healthcare professionals’ beliefs about caring for older people dying from cancer with a coincidental dementia. Dementia (14713012) 2012;11(4):559–565. doi: 10.1177/1471301212437824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck SL, Towsley GL, Caserta MS, Lindau K, Dudley WN. Symptom experiences and quality of life of rural and urban older adult cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(5):359–369. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181a52533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clarke LH, Bennett E. You learn to live with all the things that are wrong with you’: gender and the experience of multiple chronic conditions in later life. Ageing Soc. 2013;33:342–360. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X11001243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corner J, et al. Qualitative analysis of patients' feedback from a PROMs survey of cancer patients in England. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4) (no pagination)(e002316). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Courtier N, Milton R, King A, Tope R, Morgan S, Hopkinson J. Cancer and dementia: an exploratory study of the experience of cancer treatment in people with dementia. Psycho-Oncology. 2016;25(9):1079–1084. doi: 10.1002/pon.4212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dahlhaus A, Vanneman N, Guethlin C, Behrend J, Siebenhofer A. German general practitioners’ views on their involvement and role in cancer care: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2014;31(2):209–214. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fenlon D, Frankland J, Foster CL, Brooks C, Coleman P, Payne S, Seymour J, Simmonds P, Stephens R, Walsh B, Addington-Hall JM. Living into old age with the consequences of breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(3):311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fix GM, Cohn ES, Solomon JL, Cortés DE, Mueller N, Kressin NR, Borzecki A, Katz LA, Bokhour BG. The role of comorbidities in patients' hypertension self-management. Chronic Illness. 2014;10(2):81–92. doi: 10.1177/1742395313496591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hannum SM, Rubinstein RL. The meaningfulness of time; narratives of cancer among chronically ill older adults. J Aging Stud. 2016;36:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hershey DS, Tipton J, Given B, Davis E. Perceived impact of cancer treatment on diabetes self-management. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(6):779–790. doi: 10.1177/0145721712458835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kantsiper M, et al. Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S459–S466. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loerzel VW, Aroian K. Posttreatment concerns of older women with early-stage breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(2):83–88. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31821a3843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loerzel VW, Aroian K. A bump in the road-older women’s views on surviving breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2013;31(1):65–82. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2012.741093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morgan JL, Collins K, Robinson TG, Cheung KL, Audisio R, Reed MW, Wyld L. Healthcare professionals' preferences for surgery or primary endocrine therapy to treat older women with operable breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(9):1234–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nanton V, et al. The threatened self: considerations of time, place, and uncertainty in advanced illness. Br J Health Psychol. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Norman A, et al. Family physicians and cancer care. Palliative care patients’ perspectives. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:2009–2012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palmer NRA. Goals, plans, and behavior changes: a relevant part of the post-treatment cancer experience. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 2011; 71(9-B):5413.

- 51.Palmer NRA, Bartholomew LK, McCurdy SA, Basen-Engquist KM, Naik AD. Transitioning from active treatment: colorectal cancer survivors’ health promotion goals. Palliat Support Care. 2013;11(2):101–109. doi: 10.1017/S1478951512000788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sada YH, et al. Primary care and communication in shared cancer care: a qualitative study. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(4):259–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saunders Sturm CM. Breast cancer illness narratives: examining the experience of living with breast cancer. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 2003; 63(10-A):3622.

- 54.Sawin EM. “The body gives way, things happen”: older women describe breast cancer with a non-supportive intimate partner. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(1):64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sinding C, Wiernikowski J. Disruption foreclosed: older women’s cancer narratives. Health. 2008;12(3):389–411. doi: 10.1177/1363459308090055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sowerbutts AM, Griffiths J, Todd C, Lavelle K. Why are older women not having surgery for breast cancer? A qualitative study. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24(9):1036–1042. doi: 10.1002/pon.3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomé B, Dykes AK, Gunnars B, Hallberg IR. The experiences of older people living with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(2):85–96. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200304000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Volker DL, Becker H, Kang SJ, Kullberg V. A double whammy: health promotion among cancer survivors with preexisting functional limitations. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(1):64–71. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.64-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wallace HM. Getting to the other side: An exploration of the head and neck cancer treatment experience. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 2015. 75(12-A(E)): p. No Pagination Specified.

- 60.Wimberley PL. Living in the long shadow of breast cancer: Saint Louis University; 2012. p. 196.

- 61.Yoo GJ, Levine EG, Aviv C, Ewing C, Au A. Older women, breast cancer, and social support. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(12):1521–1530. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0774-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang AY, Gary F, Zhu H. Exploration of depressive symptoms in African American cancer patients. J Ment Health. 2015;24(6):351–6. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2014.998806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meiklejohn JA, Mimery A, Martin JH, Bailie R, Garvey G, Walpole ET, Adams J, Williamson D, Valery PC. The role of the GP in follow-up cancer care: a systematic literature review. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10:990–1011. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0545-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuluski K, Gill A, Naganathan G, Upshur R, Jaakkimainen RL, Wodchis WP. A qualitative descriptive study on the alignment of care goals between older persons with multi-morbidities, their family physicians and informal caregivers. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14(1):133. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lewis R, Neal RD, Williams NH, France B, Wilkinson C, Hendry M, Russell D, Russell I, Hughes DA, Stuart NSA, Weller D. Nurse-led vs. conventional physician-led follow-up for patients with cancer: systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(4):706–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lewis RA, Neal RD, Hendry M, France B, Williams NH, Russell D, Hughes DA, Russell I, Stuart NSA, Weller D, Wilkinson C. Patients’ and healthcare professionals’ views of cancer follow-up: systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(564):e248–e259. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X453576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lewis RA, Neal RD, Williams NH, France B, Hendry M, Russell D, Hughes DA, Russell I, Stuart NSA, Weller D, Wilkinson C. Follow-up of cancer in primary care versus secondary care: systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(564):e234–e247. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X453567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haggerty JL. Ordering the chaos for patients with multimorbidity. Bmj. 2012;345:e5915. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH, Jeffery DD, McNeel T. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8884–8893. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watson E, et al. PROSPECTIV-a pilot trial of a nurse-led psychoeducational intervention delivered in primary care to prostate cancer survivors: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e005186. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walter FM, Usher-Smith JA, Yadlapalli S, Watson E. Caring for people living with, and beyond, cancer: an online survey of GPs in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(640):e761–e768. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X687409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williams GR, Mackenzie A, Magnuson A, Olin R, Chapman A, Mohile S, Allore H, Somerfield MR, Targia V, Extermann M, Cohen HJ, Hurria A, Holmes H. Comorbidity in older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(4):249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bury M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol Health Illn. 1982;4(2):167–182. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reeve J, Lloyd-Williams M, Payne S, Dowrick C. Revisiting biographical disruption: exploring individual embodied illness experience in people with terminal cancer. Health (London) 2010;14(2):178–195. doi: 10.1177/1363459309353298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Frank A. The wounded story teller: body, illness and ethics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bell K. Remaking the self: trauma, teachable moments and the biopolitics of cancer survivorship. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2012;36:584–600. doi: 10.1007/s11013-012-9276-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ristovski-Slijepcevic S, Bell K. Rethinking assumptions about cancer survivorship. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2014;24(3):166–168. doi: 10.5737/1181912x243166168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.May CR, Eton DT, Boehmer K, Gallacher K, Hunt K, MacDonald S, Mair FS, May CM, Montori VM, Richardson A, Rogers AE, Shippee N. Rethinking the patient: using burden of treatment theory to understand the changing dynamics of illness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:281. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Doyle N. Cancer survivorship: evolutionary concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 62(4):499–509. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 337 kb)

(PDF 486 kb)

(PDF 449 kb)

(PDF 402 kb)