Abstract

Background

People with chronic venous insufficiency who develop leg ulcers face a difficult condition to treat. Venous leg ulcers may persist for long periods of time and have a negative impact on quality of life. Treatment requires frequent health care provider visits, creating a substantial burden across health care settings.

The objective of this health technology assessment was to evaluate the effectiveness, safety, cost-effectiveness, budget impact, and patient experiences of compression stockings for prevention of venous leg ulcer recurrence.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the literature to identify randomized trials and observational studies examining the effectiveness of compression stockings in reducing the risk of recurrence of venous leg ulcers after healing and/or reported on the quality of life for patients and any adverse events from the wearing of compression stockings. We performed a literature search to identify studies and evaluated the quality of the evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

We conducted a cost–utility analysis with a 5-year time horizon from the perspective of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. We compared compression stockings to usual care (no compression stockings) and simulated a hypothetical cohort of 65-year-old patients with healed venous ulcers, using a Markov model. Model input parameters were obtained primarily from the published literature. In addition, we used Ontario costing sources and consultation with clinical experts. We estimated quality-adjusted life years gained and direct medical costs. We conducted sensitivity analyses and a budget impact analysis to estimate the additional costs required to publicly fund compression stockings in Ontario. All costs are presented in 2018 Canadian dollars.

We spoke to people who recently began using compression stockings and those who have used them for many years to gain an understanding of their day-to-day experience with the management of chronic venous insufficiency and compression stockings.

Results

One randomized controlled trial reported that the recurrence rate was significantly lower at 12 months in people who were assigned to the compression stocking group compared with people assigned to the control group (risk ratio 0.43, 95% CI, 0.27–0.69; P = .001) (GRADE: Moderate). Three randomized controlled trials reported no significant difference in recurrence rates between the levels of pressure. One randomized controlled trial also reported that the risk of recurrence was six times higher in those who did not adhere to compression stockings than in those who did adhere. One single-arm cohort study showed that the recurrence rate was considerably higher in people who did not adhere or had poor adherence (79%) compared with those who adhered to compression stockings (4%).

Compared with usual care, compression stockings were associated with higher costs and with increased quality-adjusted life years. We estimated that, on average, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of compression stockings was $27,300 per quality-adjusted life year gained compared to no compression stockings. There was some uncertainty in our results, but most simulations (> 70%) showed that the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio remained below $50,000 per quality-adjusted life-year. We estimated that the annual budget impact of funding compression stockings would range between $0.95 million and $3.19 million per year over the next five years.

People interviewed commonly reported that chronic venous insufficiency had a substantial impact on their day-to-day lives. There were social impacts from the difficulty or inability to walk and emotional impacts from the loss of independence and fear of ulcer recurrence. There were barriers to the wearing of compression stockings, including replacement cost and the difficulty of putting them on; however, most people interviewed reported that using compression stockings improved their condition and their quality of life.

Conclusions

The available evidence shows that, compared with usual care, compression stockings are effective in preventing venous leg ulcer recurrence and likely to be cost-effective. In people with a healed venous leg ulcer, wearing compression stockings helps to reduce the risk of recurrence by about half. Publicly funding compression stockings for people with venous leg ulcers would result in additional costs to the Ontario health care system over the next 5 years. Despite concerns about cost and the daily chore of wearing compression stockings, most people interviewed felt that compression stockings provided important benefits through reduction of swelling and prevention of recurrence.

OBJECTIVE

This health technology assessment looks at the effectiveness, safety, cost-effectiveness, budget impact, and patient experiences of compression stockings for prevention of venous leg ulcer recurrence.

BACKGROUND

Health Condition

Venous leg ulcers are open wounds in the skin of the lower leg due to high pressure of the blood in the leg veins. Venous leg ulcers commonly result from a cycle of events in the leg's venous system. When functioning normally, valves in the deep and superficial veins of the leg prevent backflow of the blood. But if a person has chronic venous insufficiency, the blood can pool and the venous pressure increase. The higher pressure stretches and damages the one-way valves inside the veins, affecting functioning. In a feedback effect, this compromised functioning further increases pressure in the venous system, affecting the surrounding tissues. The sustained high pressure leads to a backflow of the blood into the thin wall of the superficial veins, forcing them to stretch and dilate. These changes lead to capillary distension, which in turn allows plasma to leak into the skin tissue, causing inflammation, edema, eczema, lipodermatosclerosis, and skin damage. Finally, an ulcer develops around the damaged skin.

Venous leg ulcers often develop in the legs of older adults with venous leg insufficiency and can lead to pain, loss of function, and distress. The ulcers may become chronic and persist for long periods of time, affecting quality of life. Recurrence of the healed venous leg ulcer is a challenging issue for health care providers and particularly for community nursing providers who are involved in the care of people with venous leg ulcers.

Some people might be candidates for surgical correction of the underlying pathology. Surgical methods, as well as a variety of minimally invasive methods that correct the underlying cause can lead to marked improvement in the condition.

Venous leg ulcers have been shown to heal faster when care is delivered by a team of specially trained professionals following an evidence-informed protocol. The majority of venous leg ulcers heal if proper compression is applied. The Canadian Bandaging Trial,1 which compared two types of compression bandages, reported a 12-month healing rate of 92% with short stretch bandages and 83% with four-layer bandages.

Classification of Venous Leg Disorders

Accurate classification of venous leg disorders is critically important for standardization of venous disease severity and appropriate treatment.2 The Clinical, Etiology, Anatomy, and Pathophysiology (CEAP) classification system, introduced in 1994 and revised in 2004, forms the basis for chronic venous disease documentation.2 The CEAP classification is as follows:

| CO | No visible or palpable signs of venous disease |

| C1 | Telangiectasies or reticular veins |

| C2 | Varicose veins |

| C3 | Edema |

| C4a | Pigmentation or eczema |

| C4b | Lipodermatosclerosis or atrophy blanche |

| C5 | Healed venous ulcers |

| C6 | Active venous ulcers |

Clinical Need and Target Population

Venous leg ulcers may cause social, personal, financial, and psychological burdens on patients and are a significant burden on the health care system. People with leg ulcers commonly report pain, itching, and sleep disturbance.3,4 The majority of people with venous leg ulcers are of advanced age, have a higher body mass index,5 and suffer from other health problems and/or impaired mobility that could affect their overall well-being as well as the healing process.6 The high recurrence rate of venous leg ulcers creates a clinical challenge, adding to the burden on clinicians and on the health care system.

Incidence and Prevalence of Venous Leg Ulcers

Prevalence studies undertaken nationally and internationally have produced estimates that between 1.5 and 3.0 per 1,000 people have active leg ulcers.7,8 In Ontario, the prevalence of active lower limb ulcers in people over the age of 25 years was estimated to be 1.8 per 1,000 people,9 with about three quarters over the age of 65. Harrison et al1 found that in Ontario, 50% of people with lower limb ulcers had leg ulcers, 35% had foot ulcers, and 15% had leg and foot ulcers.9 A large Swedish population-based study showed that 36% of all leg ulcers are caused by abnormalities in the venous system.10 Based on these findings, we estimate that 0.65 per 1,000 people in Ontario over the age of 25 years have active venous leg ulcers.

International studies that provide estimates for either leg ulcers or venous leg ulcers are comparable with the Ontario study.9 A large study from the United Kingdom11 that examined a database of about 13.5 million people reported prevalence rates of active venous leg ulcers at 0.8 to 1.2 per 1,000 for women and 0.5 to 0.8 per 1,000 for men. In a population-based study from Australia12 that included 238,000 people, the prevalence of active venous leg ulcers was 0.62 per 1,000 people, and 3.3 per 1,000 for people over the age of 60.

Epidemiological studies by Nelzen et al8 in Skarborg County, Sweden (population 270,800), show that introducing a new strategy consisting of multidisciplinary cooperation and team work, and that also includes compression stockings after healing, can decrease the prevalence of leg ulcers. Over a 14-year period after introduction of the program, the prevalence of venous leg ulcers reduced from 1.6 per 1,000 to 0.9 per 1,000, a reduction of 46%.

Venous ulcer prevalence and incidence are greater in the long-term care population than in the community at large.13 In a study of long-term care homes in Missouri,13 the prevalence of venous leg ulcer on admission was 2.5%. The incidence of venous leg ulcer for those admitted without an ulcer was 1.0%, 1.3%, 1.8%, and 2.2% at 90, 180, 270, and 365 days after admission, respectively.

The incidence of venous leg ulcer was reported by a large study from the United Kingdom11 that used The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database, which contains data prospectively collected from general practice between 2001 and 2006 for adult patients. The incidence of venous leg ulcer was 1.0 per 1,000 people.

Current Treatment Options

Compression therapy is an important component of venous leg ulcer treatment and prevention of recurrence.2,14 It helps lower venous hypertension, decrease venous stasis and inflammation, and enhance tissue vascularization. After healing, preventive measures need to be followed to prevent ulcers from recurring. Patient education along with well-fitting compression stockings and regular checkups are the standard preventive measures to minimize the risk of recurrence. Strategies to help clinicians effectively manage patients with venous leg ulcers should be considered a priority for the health system.

Recurrence is a major concern in people who have been successfully treated for venous leg ulcers owing to the underlying chronic venous insufficiency. A variety of surgical methods are used in clinical practice to correct the underlying cause of reflux and increased pressure in the veins. These surgical methods treat incompetent superficial, deep, and perforating veins of the leg. The most intractable ulcers occur when the valves of the deep veins are incompetent.15 A combination of surgical correction of the underlying cause and continued application of compression has been shown to significantly reduce recurrence of venous leg ulcers, compared with compression alone.16,17 Clinicians use a variety of minimally invasive techniques, including endovenous laser ablation, endovenous radiofrequency ablation, and sclerotherapy, to correct the underlying cause of venous hypertension.18

Health Technology Under Review

Medical-grade graduated compression stockings apply higher pressure to the ankle region, gradually decreasing the pressure in higher areas of the leg. Recent studies have also examined the potential benefits of progressive compression, where the pressure increases in the higher areas of the leg.19 Compression therapy is an essential concept in the treatment of venous and lymphatic insufficiency.15 The most commonly used compression therapy systems for venous leg ulcers are compression bandages that can provide sustained compression and aid ulcer healing. Other forms of compression therapy for venous leg ulcers include boots and intermittent pneumatic devices. Once a venous leg ulcer is healed, compression stockings are used to reduce edema and ulcer recurrence.

There is no worldwide standard to grade the level of compression pressure. Medical-grade compression stockings are categorized by the manufacturers according to the pressure they are supposed to apply to the leg; however, the described pressure may not accurately reflect the actual level of compression because there are other factors that can influence the pressure actually applied. For example, the elasticity of the stocking can break down with use. The technique used to put on and remove the stocking, as well as patient characteristics such as the shape and circumference of the leg, can also affect the level of compression achieved.14

In Ontario, class I stockings (defined as < 20 mm Hg) that provide lower pressure are available without a prescription. These are used mainly by people who stand on their feet for long periods of time or who sit in confined spaces, such as on an airplane. Medical-grade stockings offering higher pressure are dispensed by a prescription that indicates the recommended pressure. To ensure proper compression, stockings need to be replaced at regular intervals (usually every 4 months).

Before starting compression therapy, the clinician should ensure that there is adequate arterial supply to the foot. The arterial perfusion pressure is determined by the arterial brachial pressure index (ABPI). Some guidelines recommend an ABPI of 0.8 or higher for compression therapy.14 Other guidelines recommended the threshold of 0.9.2 Limb ischemia and pulmonary edema are contraindications for compression therapy.20

Regulatory Information

In Canada, compression stockings are considered Class 1 devices and they do not require a medical device licence (Personal communication, Health Canada Medical Devices Bureau).

Ontario Context

Compression stockings are not routinely publicly funded in Ontario for recurrence of venous leg ulcers. They are publicly funded in part through the provincial assistive devices program (ADP) for people with lymphedema. Funding requires diagnosis by an approved prescriber, authorization by an approved authorizer, and provision by an approved vendor. Many insurance companies provide coverage through employee benefit plans.

CLINICAL EVIDENCE

Research Questions

In people with healed venous leg ulcers:

Is there any difference in the frequency of venous leg ulcer recurrence in people who wear compression stockings compared with those who do not?

What level of compression is most effective in preventing recurrence of the healed venous leg ulcer?

What length of compression stocking is most effective in preventing recurrence of the healed venous leg ulcer?

What is the adherence rate with compression stockings at different compression levels?

What is the effect of a compression stocking on the quality of life of the person wearing it?

What are the adverse effects of compression stockings when used after venous leg ulcer healing?

Methods

We developed the research questions in consultation with patients, health care providers, clinical experts, and other health system stakeholders.

Clinical Literature Search

We performed a literature search on November 21, 2017, to retrieve studies published from inception to the search date. We used the Ovid interface in the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CRD Health Technology Assessment, and National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED). We used the EBSCOhost interface to search the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL).

Medical librarians developed the search strategy using controlled vocabulary (i.e., Medical Subject Headings) and relevant keywords. The final search strategy was peer reviewed using the PRESS Checklist.21 We created database auto-alerts in MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL and monitored them for the duration of the assessment period.

We performed targeted grey literature searching of health technology assessment agency sites and clinical trial registries. See Appendix 1 for literature search strategies, including all search terms.

Literature Screening

Two review authors conducted the initial screening of the titles and abstracts using DistillerSR management software (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, ON) and then obtained the full text of studies that appeared eligible for the review according to the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus. The reviewers then examined the full text articles and selected studies that were eligible for inclusion. They also examined reference lists of the included studies for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

Studies published from inception to November 21, 2017

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective cohort studies that compared the recurrence rate in people with a healed venous leg ulcer with and without the use of compression stockings

RCTs that compared results of different compression levels in people with a healed venous leg ulcer

RCTs that compared results of different lengths of stockings (e.g., below vs. above knee/thigh length) in people with a healed venous leg ulcer

Studies that examined the effect of compression stockings on the quality of life of people with a healed venous leg ulcer

Studies that examined the adverse effects or mortality caused by compression stockings in people with a healed venous leg ulcer

Exclusion Criteria

Studies on compression bandages and devices such as boots and pneumatic devices

Studies in which the origin of the ulcer was not venous

Studies that compared different brands of stockings or compared compression stockings with other compression methods

Editorials, case reports, or commentaries

Outcomes of Interest

Primary Outcome

Recurrence of the healed venous leg ulcer or the occurrence of a new venous leg ulcer on either leg

Secondary Outcomes

Time to recurrence of the healed venous leg ulcer

Time to occurrence of a new venous leg ulcer

Adherence rate

Quality of life

Adverse effects of compression stockings

Mortality

Out of Scope

There are minimally invasive and other surgical methods to correct the underlying pathology that causes venous leg ulcer recurrence, but they are out of scope for this review.

Data Extraction

We extracted relevant data on study and patient characteristics, outcomes, and risk-of-bias items using a data form to collect information about the following:

Source (citation information)

Methods (study design, study place, follow-up, participant characteristics, and randomized groups)

Outcomes (recurrence rate, time to recurrence, adherence to compression stockings, number of participants for each outcome, number of participants missing for each outcome, and time points at which the outcomes were assessed)

Items for risk of bias for RCTs (method of sequence generation, method of allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting of outcomes)

Items for risk of bias for cohort studies

Statistical Analysis

We used STATA 11 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas) to perform a meta-analysis on the reported recurrence rates and produced a forest plot. We used the risk ratio and its 95% confidence interval as the summary statistic to display the difference between groups. We used a random effects model to pool the data and the chi-square test to determine statistical heterogeneity among the studies.

Critical Appraisal of Evidence

For randomized controlled trials, we assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias tool.22 For observational cohort studies, we used Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I).23 We evaluated the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Handbook.24 The body of evidence was assessed based on the following considerations: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. The quality score reflects our assessment of the reliability of the evidence presented.

Expert Consultation

We solicited expert feedback from a variety of organizations involved in the management of ulcers in Ontario. We consulted dermatologists, nurses specialized in wound care, and chiropodists who routinely visit patients with venous leg ulcers. The role of the expert advisors was to provide feedback on our questions, to provide advice on the appropriate use of the technology, and to review the clinical review plan and the health technology assessment report.

Results

Literature Search

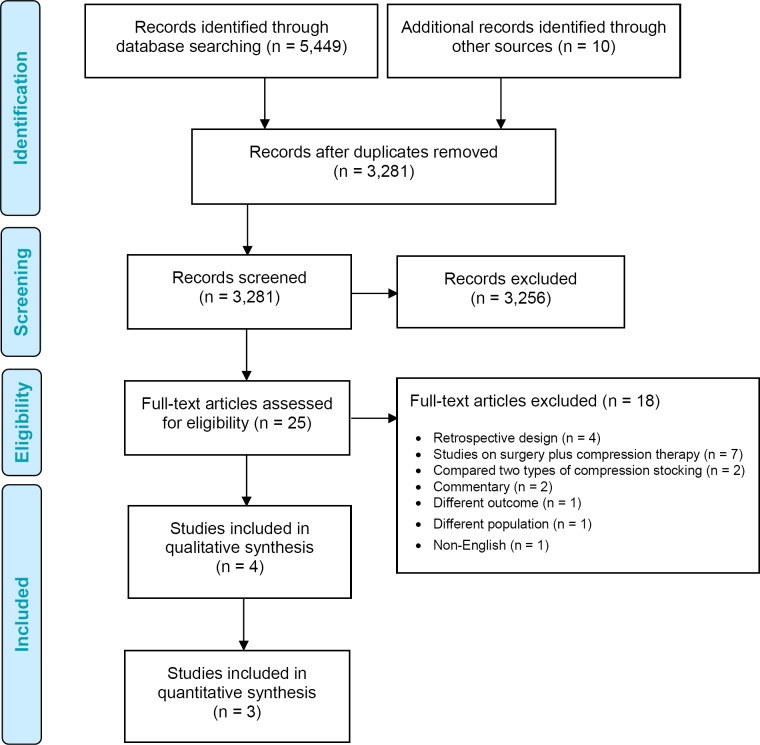

The literature search yielded 3,281 citations published from inception to November 21, 2017, after removing duplicates. Seven studies (four randomized control trials25–28 and three prospective cohort studies29–31) met the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1 presents the flow diagram for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Figure 1: PRISMA Flow Diagram—Clinical Search Strategy.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al.32

Study and Patient Characteristics

Four RCTs25–28 and three single-arm observational cohort studies29–31 met our inclusion criteria. One RCT compared compression with no compression and three RCTs compared two levels of compression pressure. Two observational cohort studies compared the recurrence rate of those who adhered to stockings with the recurrence rate of those who did not, or with people who dropped out. One prospective observational study reported on patients' quality of life.

We did not find any study reporting on mortality resulting from the wearing of compression stockings. Also, we did not find any study that compared compression stockings of different lengths.

Tables 1 and 2 show study design, patient characteristics, adherence rate, and recurrence rate for RCTs and observational studies.

Table 1:

Study, Patient, and Intervention Characteristics: Randomized Controlled Trials on Compression Stockings

| Author, Year | Country | Study Objective | Randomized Groupsa | Stocking Type | Patients Na | Female/Male N | Mean Age Years (SD)a | Outcome Measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kapp et al, 201326 | Australia | To compare the effect of moderate pressure with high pressure on recurrence of VLU and patient adherence | 23–32 mm Hg vs. 34–46 mm Hg |

Venosan 5000 range, Salzmann, MEDICO, St Gallen, Switzerland Below knee length Participants were provided with two stockings for wear on the study leg only |

93 Moderate: 49 High: 44 |

68/25 | 23–32 mm Hg: 79.04 (10.40) 34–46 mm Hg: 78.27 (10.56) |

Recurrence rate Time to recurrence Adherence rate Adverse effects |

| Clarke-Moloney et al, 201425 | Ireland | To compare the effect of two European classes of MCS on recurrence of VLU and patient adherence | 18–21 mm Hg vs. 23–32 mm Hg |

Mediven elegance (closed toe) or Mediven plus (open toe) | 100 18–21 mm Hg: 50 23–32 mm Hg: 50 |

NA | 18–21 mm Hg: 69.7 23–32 mm Hg: 68.9 |

Recurrence rate Adherence rate |

| Nelson et al, 200627 | United Kingdom | To compare the effect of two European classes of MCS on recurrence of VLU and patient adherence | 18–24 mm Hg vs. 25–35 mm Hg |

Jobst or Medi Knee or thigh length |

300 18–24 mm Hg: 151 25–35 mm Hg: 149 |

18–24 mm Hg: 92/59 25–35 mm Hg: 83/66 |

18–24 mm Hg: 65.1 (12.9) 25–35 mm Hg: 63.6 (11.4) |

Recurrence rate Time to recurrence Adherence rate |

| Vandongen & Stacey, 200028 | Australia | To compare the effect of MCS with no MCS on reducing the area of lipodermatosclerosis and recurrence of VLU | MCS with pressure of 35–45 mm Hg vs. no MCS | Venosan 2003 Below knee length |

153 MCS: 72 No MCS: 81 |

NA | 67 (range, 37–85) | Recurrence rate Adherence rate |

Abbreviations: MCS, medical compression stocking; NA, not available; SD, standard deviation; VLU, venous leg ulcer.

mm Hg stocking pressure.

Table 2:

Study, Patient, and Intervention Characteristics: Single Arm Prospective Trials on Compression Stockings

| Author, Year | Country | Study Objective | Subgroup Analysis | Stocking Type | Patients N | Female/Male n | Mean Age, Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samson & Showalter, 199631 | USA | To evaluate MCS for treatment of VLU and prevention of recurrence | Adherence vs. nonadherence | UlcerCare System (Jobst) | 53 | 28/25 | 71 (range, 45–94) |

| Dinn & Henry, 199229 | Ireland | To determine whether use of MCS can reduce the risk of VLU recurrence | Adherents vs. dropped out | Scholl Soft Grip elastic stockings | 126 (VLUs were healed by sclerotherapy) | 91/35 | 59.5 (range 26–80) |

| Reich-Schupke et al 200930 | Germany | To assess whether there are differences in the treatment behaviour and the quality of life of patients experiencing compression therapy | NA | NA | 110 | 72/38 | 66.2 (SD, 13.57) |

Abbreviations: MCS, medical compression stocking; NA, not applicable; SD, standard deviation; VLU, venous leg ulcer.

Recurrence Rate

Recurrence rates reported by the four RCTs are shown in Table 3. Vandongen and Stacey28 randomized participants into compression stocking and no compression stocking groups. Compression stockings reduced the risk of recurrence by half after 12 months (24% vs. 54% in the compression stocking vs. no compression stocking groups, respectively; risk ratio 0.43, 95% CI, 0.27–0.69; P = .001). The primary outcome of this study was an assessment of the effectiveness of compression stockings in reducing the area of lipodermatosclerosis (considered a precursor of venous leg ulcers) in participants with healed venous ulcers. Participants were given two pairs of stockings with pressure of 35–45 mm Hg every 6 months and were instructed to wear each pair on alternate days. Participants who did not adhere to the instructions were withdrawn from the study. In the stocking group, there were 12 stocking-related withdrawals at 6 months and 16 at 12 months. In the no-stocking group, three participants withdrew so that they could wear stockings. Other causes of withdrawal after 12 months in the no-stocking group were personal/medical (n = 7), death (n = 3), lost to follow-up (n = 3).

Table 3:

Recurrence Rates in Randomized Controlled Trials

| Author, Year | Recurrence Rate | P |

|---|---|---|

| Kapp et al, 201326 |

6 months leg locationa 23–32 mm Hg: 7/49 (14.3%) 34–46 mm Hg: 6/44 (13.6%) |

1.00 |

|

6 months study ulcera 23–32 mm Hg: 7/49 (14.3%) 34–46 mm Hg: 4/44 (9.1%) |

.65 | |

| Clarke-Moloney et al, 201425 |

12 months 18–21 mm Hg: 10/50 (20%) 23–32 mm Hg: 6/50 (12%) |

.29 |

| For those adhered to MCS: 9/85 (10.6%) 18–21 mm Hg: 6/43 (14%) 23–32 mm Hg: 3/45 (7%) |

.31 | |

| For those not adhered to MCS: 7/11 (63.6%) Risk ratio: 6.2 (95% CI, 2.9–13.5; P < .001) |

||

| Nelson et al, 200627 |

5 years 18–24 mm Hg: 59/151 (39%) 25–35 mm Hg: 48/149 (32%) |

.13 |

| Vandongen & Stacey, 200028 |

6 months MCS: 15/72 (21%) No MCS: 37/81 (46%) 12 months MCS: 17/72 (24%) No MCS: 44/81 (54%) Median percentage change in lipodermatosclerosis area in participants who did not develop ulcers 12 months (n = 46) MCS: −33.1 (95% CI, −61.9–15.07) No MCS: +11.9 (95% CI, −24.6–122.2) |

.04 |

Abbreviation: MCS, medical compression stocking.

Study ulcers develop in the same anatomical location as the previous ulcer. Leg location ulcers develop in a different anatomical location as the previous ulcer.

Vandongen and Stacey28 found that in participants whose ulcer did not recur, the area of lipodermatosclerosis was significantly reduced after 6 and 12 months in the stockings group, while it increased in the control group. The median percentage change in the area of lipodermatosclerosis at 6 months was −22% in the stocking group and +7.8% in the no-stocking group (indicating an increase in the area). At the 12-month follow-up, the change in the area was −33.1 (95% CI, −61.9–15.07) for the stocking group, and +11.9 (95% CI, −24.6–122.2) for the no-stocking group (P = .04). The initial area of lipodermatosclerosis was significantly larger in participants whose ulcer recurred within 2 years of entering the study compared with those whose ulcer did not recur (median area of 293.4 cm2 vs. 49.5 cm2, respectively).

The two observational studies included in this review were single arm cohort studies, but they provided indirect comparison of compression use and also provided data on longer term follow-up.29,31 Although the findings from these studies are based on their subgroup analysis, they may provide support for the findings of the RCT.28 Samson and Showalter31 included only people with documented deep venous insufficiency whose ulcer had healed. This observational study evaluated a new type of compression stocking that consisted of a liner that provided mild pressure and an outer layer with zipper to provide 40 mm Hg pressure. They found the risk of recurrence at follow-up (mean of 28 months) was 20 times higher in participants who had poor or no adherence to the compression stockings than in those who had good adherence (RR 18.4, 95% CI 2.68–126.16, P < .001).

The other observational study, by Dinn and Henry,29 had a 5-year follow-up that compared the recurrence rate between those who adhered to stockings and those who dropped out of the study. The rationale for this comparison was that it would be unrealistic to request people in a varicose vain clinic to not wear compression stockings. In this study, a high degree of adherence was obtained by exact fitting of the stockings and regular review by the same clinician. At the end of the 5 years, 21 participants had dropped out. Of the 21, 7 were untraceable and 2 had died. Ten of the 12 traceable people had ulcer recurrence. Of the 105 people who adhered to stockings, 33 (31%) had ulcer recurrence over a 5-year period of follow-up.

In studies that compared the effectiveness of two levels of compression pressure, recurrence rates ranged from 14% to 39% for stockings with lower pressure and from 12% to 32% for stockings with relatively higher pressure. None of the studies found a significant difference between the two groups. Recurrence rates reported by RCTs are shown in Table 3.

Table 4 shows risk ratios that we calculated for recurrence rates in RCTs.

Table 4:

Risk Ratios for Recurrence

| Author, Year | Follow-Up (Months) | Group 1 | Recurrence | Group 2 | Recurrence | Risk Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kapp et al, 201326 | 6 | 34–46 mm Hg | 6/44 (13.6%) | 23–32 mm Hg | 7/49 (14.3%) | 0.73 (0.23–2.3) P = .59 |

| Clarke-Moloney et al, 201425 | 12 | 25–35 mm Hg | 6/50 (12%) | 18–24 mm Hg | 10/50 (20%) | 0.60 (0.23–1.52) P = .28 |

| Nelson et al, 200627 | 60 | 25–35 mm Hg | 48/149 (32%) | 18–24 mm Hg | 59/151 (39%) | 0.82 (0.61–1.12) P = .23 |

| Vandongen & Stacey, 200028 | 12 | MCS | 17/72 (24%) | No MCS | 44/81 (54%) | 0.43 (0.27–0.69) P = .001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; MCS, medical compression stocking.

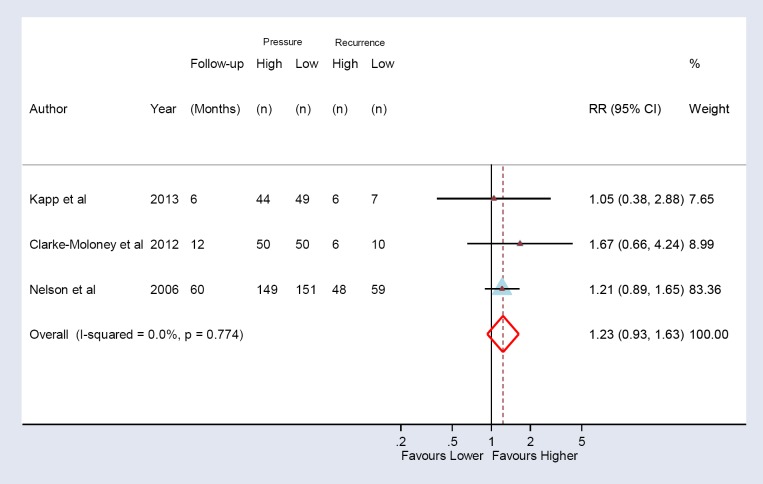

We meta-analyzed the recurrence rate of three RCTs comparing the effectiveness of different levels of compression pressure for the prevention of venous leg ulcer recurrence. The pooled estimate showed that recurrence rates were slightly higher for stockings with lower pressure than those for stockings with higher pressure, but the results did not reach statistical significance (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Recurrence Rate for Compression Stockings With Higher and Lower Compression Pressure.

Sources: Nelson et al, 200627; Kapp et al, 201326; Clark-Moloney et al, 2014.25

Time to Recurrence

Only one RCT reported data for time to recurrence for any ulcer on the leg. In a group randomized to compression stockings of 23–32 mm Hg pressure, ulcers recurred in 78 ± 59 days.26 In a comparison group with compression stockings of 34–46 mm Hg pressure, ulcers recurred in 57 ± 61 days. However, a significantly higher percentage of participants in the 34–46 mm Hg group did not adhere to the compression protocol compared with those who were assigned to the 23–32 mm Hg group (61.4% vs. 28.6%; P = .003). Another RCT27 reported no difference between lower and higher pressure stockings in time to recurrence (P = .14).

Adherence Rate

We found three RCTs that compared stockings with different levels of pressure, and one observational study that reported adherence. In one RCT, the adherence rate was higher for stockings with lower pressure than for stockings with higher pressure. Table 5 provides a summary of the adherence rates reported by the RCTs.

Table 5:

Adherence Rate: Compression Stockings With Different Pressure

| Author, Year | Follow-Up (Months) | Pressure (mm Hg) | Adherence | Pressure (mm Hg) | Adherence | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kapp et al, 201326 | 6 | 34–46 | 38.6% | 23–32 | 71.4% | .003 |

| Clarke-Moloney et al, 201425 | 12 | 25–35 | 90% | 18–24 | 86% | .76 |

| Nelson et al, 200627 | 60 | 25–35 | Stopped wearing MCS: 2% Switched to other group: 40% |

18–24 | Stopped wearing MCS: 2% Switched to other group: 25% |

NA |

Abbreviations: MCS, medical compression stocking; NA, not available.

In the observational study, participants wearing stockings of 40 mm Hg pressure were categorized as good, poor, and none with respect to their adherence to protocol.31 Twenty five of 53 participants (47%) had good adherence and 28 (53%) had either poor or no adherence to the stocking protocol.

Quality of Life

Reich-Schupke et al30 reported on a prospective observational study on the quality of life and adverse effects of compression therapy. A questionnaire was sent to adults with stages C2–C6 chronic venous insufficiency who were being treated with compression therapy at a vein centre in Germany.

Two hundred questionnaires were sent and 110 were returned (55%). Seventy-two (65.5%) respondents were female and 38 (34.5%) were male. The respondents were being treated with compression therapy due to sclerotherapy (41.8%), venous surgery (37.3%), leg ulcer (13.6%), conservative therapy for venous insufficiency (12.7%), post-thrombotic syndrome (11.8%), deep vein thrombosis (4.5%), and other reasons (8.2%). Some respondents qualified under more than one category. Compression therapy was applied mostly through compression stockings (97%). The mean duration of compression therapy was 61.5 ± 135.5 months for those who had leg ulcers, 23.63 ± 56.02 months for those who had surgery, and 22.53 ± 61.39 months for those who had sclerotherapy.

Life quality items were scored from 0 to 4, with 0 indicating no problem and 4 indicating discomfort or concern. Responses to quality of life experiences are shown in Table 6.

Table 6:

Quality of Life Scores

| Life Quality Items | Median Score |

|---|---|

| Global health | 1.36 |

| Handling of symptoms | 1.32 |

| Global life quality | 1.29 |

| Symptoms of the legs | 1.25 |

| Anxiety and worries | 1.21 |

| Life satisfaction | 1.18 |

| Functional status | 0.84 |

The results suggest that compression therapy did not have a substantial negative impact on quality of the life for most respondents. Reported impressions of stockings included functional (56.4%), comfortable (29.1%), uncomfortable (19.1%), and intolerable (1.8%).

The authors performed a subgroup analysis according to the duration of treatment (< 2 mo, 2–12 mo, 13–48 mo, and > 48 mo).30 All groups reported improvement in their symptoms. There were no significant differences between the groups for acceptance of use or changes they felt in their legs. The primary complaint across all groups was suboptimal fitting of stockings that caused slipping or uncomfortable contraction.

Adverse Effects

One RCT26 reported that 9% of participants experienced adverse effects. Eight (8%) reported discomfort with the stockings due to tightness and one (1%) had skin irritation due to sensitivity, which was resolved in 3 days by removing the stocking. All participants who experienced adverse effects agreed to remain in the study for follow-up.

Respondents to the questionnaire from Reich-Schupke et al30 reported dryness (58.5%), itching of the legs (32.7%), slipping (29.1%), constriction of the leg (24.5%), scaling (24.5%), sweating (19.1%), feeling of cold (15.5%), redness (10.9%), pain (6.4%), paresthesia (5.5%), restriction of the movement in the ankle region (4.5%), and a burning sensation (1.8%).

Critical Appraisal of the Evidence

We used the Cochrane risk of bias tool22 to assess the risk of bias for RCTs and ROBINS-I23 for non-randomized studies. We evaluated the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome according to the GRADE methodology. Randomized controlled trials were downgraded due to the high rate of nonadherence to the study or to the randomized group. Tables A1 and A2 (Appendix 2) show our evaluation of the risk of bias and Tables A3–A5 (Appendix 2) show the overall quality of evidence.

Discussion

We found that compression stockings are an effective intervention to reduce the risk of ulcer recurrence. One RCT that randomized participants into compression stockings and no compression showed that the recurrence rate at 12 months was two times higher among participants in the no-compression group (GRADE: Moderate).28 The pooled estimate for 3 RCTs that compared compression stockings with different levels of pressure did not show a statistically significant difference in ulcer recurrence rates.

Generally, stockings with a 25–35 mm Hg pressure have a clear effect on superficial veins, but less or no effect on the deep veins of the leg. Higher pressure stockings, such as 35–45 mm Hg or higher, show benefits for both the superficial and deep veins and are more effective when deep venous systems are involved.31 In a study by Clarke-Moloney,25 one third of participants who had both superficial and deep vein incompetence and were assigned to low pressure stockings developed ulcers.

Patient adherence to compression stockings is an important factor for the intervention to be effective. One RCT25 showed that the risk of ulcer recurrence was six times higher in those who did not adhere to stockings than in those who adhered. One observational study31 demonstrated that the recurrence rate was much lower in people who adhered to compression stockings (4% recurrence) than in those who did not (79% recurrence). High-pressure compression stockings were associated with lower adherence levels due to higher rates of discomfort. There is insufficient evidence to determine whether the lower adherence rate for high pressure stockings is offset by their higher effectiveness.

Overall, patients reported improvement in their leg symptoms without a substantial negative impact on their quality of life. However, 19% reported discomfort and about 2% reported that the discomfort was intolerable. The main problem people found with their stockings was suboptimal fitting that caused slipping or uncomfortable contraction. The use of compression stockings is usually safe, although some adverse effects may occur, including allergic reaction and damage to the skin tissue. However, most adverse effects can be minimized or prevented.

Our results are comparable with a previous Cochrane systematic review by Nelson and Bell-Syer.7 Their search was conducted in 2014, when only three RCTs and one abstract were available for assessment.

Limitations

There are few published studies investigating the effect of compression therapy in the prevention of venous leg ulcer recurrence. Most studies of venous leg ulcers focus on ulcer treatment strategies rather than on prevention of recurrence.

Conclusions

The available evidence shows that compression stockings are safe and effective in preventing venous leg ulcer recurrence. In people with a healed venous leg ulcer, wearing a compression stocking helps to reduce the risk of recurrence by about half (GRADE: Moderate).

ECONOMIC EVIDENCE

Research Question

What is the cost-effectiveness of compression stockings for the prevention of venous leg ulcer recurrence in people with a healed venous ulcer, based on the published literature?

Methods

We performed an economic literature search on November 23, 2017, for studies published from inception to the search date. To retrieve relevant studies, the search was developed using the clinical search strategy with an economic filter applied.

We created database auto-alerts in MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL and monitored them for the duration of the HTA review. We performed targeted grey literature searching of health technology assessment agency websites, clinical trial registries, and Tufts Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry. See Clinical Literature Search, page 13, above, for further details on methods used, and Appendix 1 for literature search strategies, including all search terms.

Literature Screening

A single reviewer reviewed titles and abstracts, and, for those studies likely to meet the eligibility criteria, we obtained full-text articles and performed further assessment for eligibility.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

Studies published from inception to November 23, 2017

Studies examining compression stockings for the prevention of venous leg ulcer recurrence in people with a healed venous ulcer

Cost–utility, cost-effectiveness, or cost-benefit analyses

Exclusion Criteria

Reviews, letters or editorials, case reports, commentaries, abstracts, and posters

Studies that conducted an economic evaluation on people with unhealed leg ulcers

Outcomes of Interest

Costs

Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) or time without recurrence

Incremental cost and incremental effectiveness

Incremental cost per QALY or per other health outcome gained

Data Extraction

We extracted relevant data on the following:

Source (i.e., name, location year)

Population and comparator

Interventions

Outcomes (i.e., health outcomes, costs, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio) We contacted authors of the studies to provide clarification as needed.

Study Applicability

We determined the usefulness of each identified study for decision-making by applying a modified applicability checklist for economic evaluations that was originally developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom.33 The original checklist is used to inform development of clinical guidelines by NICE. We retained questions from the NICE checklist related to study applicability and modified the wording of the questions to remove references to guidelines and to make it Ontario-specific. A summary of the number of studies judged to be directly applicable, partially applicable, or not applicable to the research question is presented.

Results

Literature Search

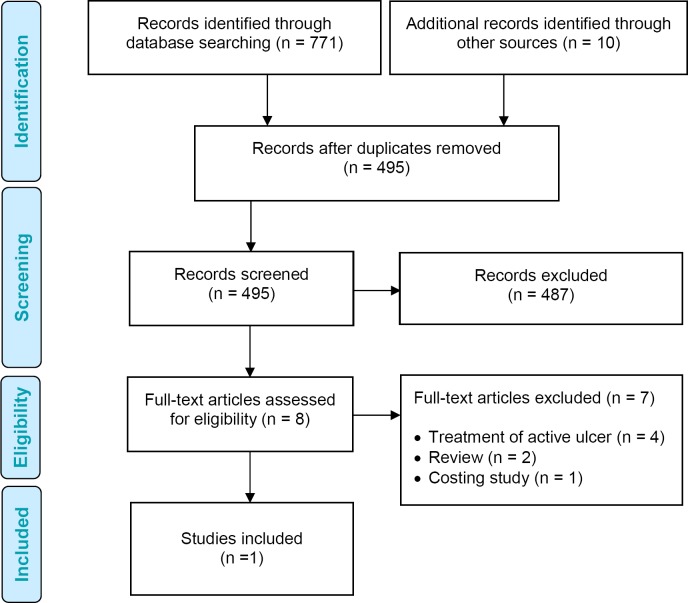

The literature search yielded 495 citations published between inception and November 23, 2017, after removing duplicates. We excluded a total of 487 articles based on information in the title and abstract. We then obtained the full texts of eight potentially relevant articles for further assessment.34–40 Figure 3 presents the flow diagram for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Figure 3: PRISMA Flow Diagram—Economic Search Strategy.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al.32

After review of the eight full-text articles, we found that one study34 met the inclusion criteria. We reviewed the reference list for any additional studies not identified through the systematic search. Excluded studies included two reviews,35,36 four cost-effectiveness analyses that evaluated treatment of active venous ulcers,37–40 and one costing study31 that estimated only the costs of healing in people with primary and recurred ulcers.

Review of Included Economic Studies

Table 7 provides a summary of the included study,34 a model-based cost–utility analysis conducted over a lifetime horizon from a United States health payer perspective. The results indicate that ulcer prevention with compression stockings and patient education is dominant (less costly and more effective) compared with no intervention in people with healed venous ulcers. In the study, compression stockings plus patient education led to 0.37 more QALYs and saved $5,904 USD per patient, compared to no intervention.34 The authors conducted several sensitivity analyses. When the cost of amputations or ulcer treatment was excluded, or when the cost of stockings were increased by 600%, compression stockings with patient education remained cost-effective at a willingness-to-pay threshold below $60,000 USD per QALY gained. Compression stockings were no longer cost-effective when the mean time to ulcer recurrence for people using stockings was shorter (21.1 months).

Table 7:

Results of Economic Literature Review—Summary

| Author, Year, Location | Study Design, Analytic Technique, Perspective, and Time Horizon | Population | Intervention/Comparator | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Outcomes | Costsa | Cost-Effectiveness | ||||

| Korn et al., 2002, United States34 |

|

55-year-old patients with prior leg ulcer |

|

Total QALYs:

|

Total cost:

|

CS with PE dominated (more effective, less costly) no intervention |

Abbreviations: CS, compression stockings; PE, patient education; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

All costs in US dollars.

Perspective of Medicare and other insurers.

Applicability of the Included Study

The results of the applicability checklist for economic evaluations applied to the included study is presented in Appendix 2 (Table A6). The study was deemed partially applicable to the research question.

Discussion

Our systematic review identified one study evaluating the cost–utility of prevention with compression stockings and patient education compared to no intervention in 55-year-old patients with prior venous leg ulcers.34 Authors obtained recurrence rates and patient adherence data from a published retrospective review of clinic records41 and clinical trials with 15 years follow up.42 Costs were derived from the cost accounting system at the New York Presbyterian Hospital (Transition Systems, Inc, Boston, MA) and the published literature. The authors concluded that compression stockings plus patient education was effective and cost saving, even under conservative assumptions.34

The study by Korn et al34 has several limitations that may limit the applicability of the study results to the Ontario setting. First, the study was conducted from a US health payer perspective. Second, although the specified target population was people with healed ulcers, some transition probabilities for the analysis were obtained from studies of patients with active ulcers. Third, amputation was included in the model as a potential complication, but it is unclear how the risk of amputation was derived for this population. Finally, Korn et al evaluated prophylactic compression stockings combined with patient education.34 Our review examines the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of compression stockings alone, and not in combination with a patient education program.

Conclusions

One study showed that compression stockings with patient education for the prevention of venous leg ulcers was effective and cost saving, at least in the US context. No studies identified were directly applicable to the Ontario or Canadian health system perspective.

PRIMARY ECONOMIC EVALUATION

The published economic evaluation identified in the literature review examined the cost-effectiveness of compression stockings for the prevention of venous leg ulcers, but the study did not take a Canadian perspective. Further, the study looked at compression stockings in combination with a patient education program. Owing to these limitations, we conducted a primary economic evaluation.

Research Question

What is the cost-effectiveness of compression stockings compared with usual care (no compression stockings) in preventing the recurrence of venous leg ulcers from the perspective of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care?

Methods

The information presented in this report follows the reporting standards set out by the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards Statement.43

Type of Analysis

We conducted a reference case analysis and various types of sensitivity analyses. Our reference case analysis adhered to the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) guidelines,44 where appropriate, and represents the analysis with the most likely set of input parameters and model assumptions. In sensitivity analyses, we explored how the results are affected by varying input parameters and model assumptions.

We performed a cost–utility analysis that assessed the cost per QALY gained.

Target Population

The study population of interest was people aged 65 with a healed venous leg ulcer who are at risk of ulcer recurrence.

Our target population was based on a randomized controlled trial with a 5-year follow-up.27 The study was conducted in leg ulcer clinics in two hospitals in Scotland.27 The study included 300 outpatients (71% female) with recently healed venous ulcers and no significant arterial disease, rheumatoid disease, or diabetes mellitus. The average age and sex ratio from this study is similar to that for venous leg ulcer patients in Ontario.40

Perspective

We conducted this analysis from the perspective of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Intervention and Comparator

We compared preventative treatment with compression stockings to no compression stockings. Compression stockings come in different classes, based on the pressure (measured in mm Hg) provided at the ankle.

Currently, there are no international standards on the classification of compression stockings. Our analysis used clinical data from the previously described RCT conducted in Scotland.27 That study adopted the UK classification of compression therapies45:

Class 1 represents compression at the ankle of 13–17 mm Hg

Class 2 represents compression at the ankle of 18–24 mm Hg

Class 3 represents compression at the ankle 25–35 mm Hg

North American classification46 includes the following compression classes:

Support represents compression at the ankle of 15–20 mm Hg

Class 1 represents compression at the ankle of 20–30 mm Hg

Class 2 represents compression at the ankle of 30–40 mm Hg

Class 3 represents compression at the ankle of 40–50 mm Hg

In practice, North American Class 3 is infrequently prescribed or tolerated by patients (Laura Teague, written communication, Dec 11, 2017).

For clarity, throughout this report we discuss the level of compression by reference to mm Hg at the ankle and we assume that UK clinical evidence and classifications are generalizable to Ontario.

Our intention was to examine the cost-effectiveness of compression therapy. We did not attempt to determine the relative cost-effectiveness of specific compression values (classes) versus other compression values. We assumed that the compression class prescribed would be determined based on patient history and preferences. Table 8 summarizes the interventions evaluated in the economic model.

Table 8:

Disease Interventions and Comparators Evaluated in the Primary Economic Model

| Intervention | Comparator | Patient Population | Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compression stockings | No compression stockings | People with a healed venous leg ulcer, aged 65 y, 71% female | QALYs | Nelson et al, 200627 |

Abbreviation: QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

Outcomes of Interest

Effectiveness outcomes: QALYs

Direct medical costs

-

Incremental cost-effectiveness/cost–utility ratio (ICER): cost per QALY gained

∘ The ICER is given by the difference in mean expected costs (i.e., incremental cost, ΔC) between the two compared strategies divided by the difference in mean expected outcomes (i.e., incremental effect, ΔE) between these strategies (ICER = ΔC/ΔE)

Discounting and Time Horizon

We applied an annual discount rate of 1.5% to both costs and QALYs based on the most recent CADTH economic guidelines.44 We used a 5-year time horizon in all analyses based on the longest follow up time reported in our clinical review and a recent Cochrane review on ulcer prevention.7

Model Structure

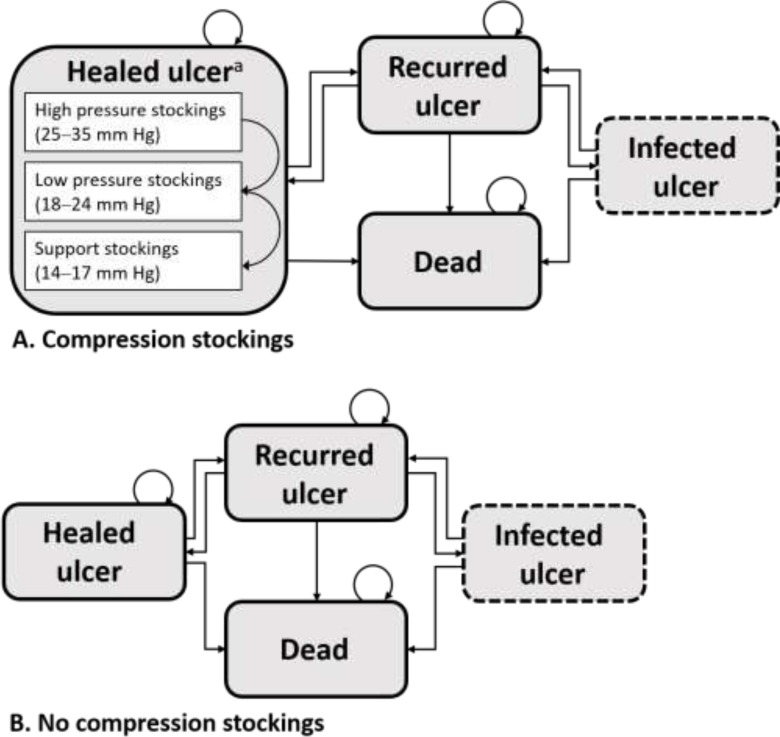

We developed a state-transition Markov model to determine the incremental cost per QALY (Figure 4). The model was adapted from a model structure developed by Nherera et al.47 for people with the chronic venous leg ulcers. We used 1-month cycles to follow people over 5 years.

Figure 4: Markov Model Structure.

aNonadherent patients switch to lower pressure stockings.

The main Markov health states are as follows:

Healed ulcer: people with a healed venous leg ulcer

Recurred ulcer: people who develop a venous leg ulcer on the reference limb (the limb with the healed ulcer)

Infected ulcer: people with a venous leg ulcer exposed to bacterial infection with the symptoms of worsening pain, a green or unpleasant discharge coming from the ulcer, redness and swelling of the skin around the ulcer, and/or a high temperature (fever)48

Dead: Death could be the result of comorbidities or any other cause

Further health states are used to capture adherence to compression stockings

Everyone entered the Markov model in the healed ulcer health state. People in the compression stockings arm were treated with compression stockings for the duration of the model (Figure 4A). People in the no compression stockings arm did not receive any compression stockings for the duration of the model (Figure 4B).

We considered three ranges of compression stockings in our model, based on the UK classes:

High pressure (25–35 mm Hg compression at the ankle)

Low pressure (18–24 mm Hg compression at the ankle)

Support (13–17 mm Hg compression at the ankle)

We excluded 40–50 mm Hg compression at the ankle as it is rarely used in clinical practice (see Intervention and Comparator, above).

Based on the RCT conducted by Nelson and colleagues,27 we assumed that all individuals would initially be prescribed high pressure or low pressure compression stockings. That is, some individuals in the compression stockings arm would start in the high-pressure range and others in the low-pressure range.

Over the course of the study, people could transition between states if events warranted. For instance, a person who had a leg ulcer recurrence would transition from the healed ulcer health state to the recurred ulcer health state. The infected ulcer health state is a temporary condition. We assumed people who move from the recurred ulcer health state to the infected ulcer health state would heal after 1 month and return to their previous (recurred ulcer) health state. Because the infected ulcer health state is of shorter duration, we distinguish it from the other health states in Figure 4 with a dashed border.

People in the compression stockings group could adhere (i.e., wear the prescribed compression stockings) or not adhere (i.e., fail to wear the prescribed compression stockings) with the intervention. Those who did not adhere to the prescribed treatment were changed to lower pressure stockings (those originally prescribed high pressure would switch to low pressure and those originally prescribed low pressure would switch to support; see Figure 4A). We assumed that nonadherence would occur at a steady rate over the 5-year time horizon. We also assumed that all patients would adhere with second-line compression stockings. This was consistent with the trial conducted by Nelson and colleagues,27 which found only 2.7% of patients did not adhere to any compression level over the 5-year time horizon. We tested this assumption in a sensitivity analysis. Further, we assumed that people with a recurrence and subsequent healing of an ulcer would return to the previous level of compression and that this would hold for the duration of the model unless they did not adhere.

People in the no compression stocking group (usual care) had a similar model structure (Figure 4B).

Main Assumptions

The major assumptions for this model are:

Everyone has a healed venous leg ulcer before entering the model

People who get an ulcer during the model will go back to the same compression grade once healed

People (alone or with the help of a caregiver) are responsible for putting on and removing their own compression stockings

Compression stockings are replaced every four months

All infections require treatment with antibiotics, but there are no other complications that affect QALYs or cost

People with infected ulcers spend no more than 1 month in the infected ulcer health state

People who change to a lower pressure stocking because they did not adhere to treatment will adhere to this lower pressure treatment

The adherence rate does not change over time

Classes in Ontario are equivalent with those used in the model

Everyone starts on low pressure (18–24 mm Hg) or high pressure (25–35 mm Hg) compression stockings

Clinical Input Parameters

We obtained our clinical input parameters from the published literature and expert opinion (Table 9).

Table 9:

Input Parameters: Probabilities and Risks

| Model Parameter | Mean | Rangea | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial distribution of people in compression stockings arm | |||

| High pressure (25–35 mm Hg) | 0.3 | 0.1–0.5 | Expert opinion |

| Low pressure (18–24 mm Hg) | 0.7 | 0.4–0.9 | Expert opinion |

| Support (14–17 mm Hg) | 0 | 0.1–0.3 | Expert opinion |

| Monthly probabilities and rates | |||

| Probability of nonadherence: | |||

| High pressure (25–35 mm Hg) | 0.009 | 0.006–0.012 | Nelson et al, 200627 |

| Low pressure (18–24 mm Hg) | 0.005 | 0.003–0.007 | Nelson et al, 200627 |

| Support (14–17 mm Hg) | 0.0005b | 0.0002–0.0008 | Nelson et al, 200627 |

| Probability of ulcer recurrence, compression stockings: | |||

| High pressure (25–35 mm Hg) | 0.006 | 0.004–0.008 | Nelson et al, 200627 |

| Low pressure (18–24 mm Hg) | 0.008 | 0.006–0.010 | Nelson et al, 200627 |

| Support (14–17 mm Hg) | 0.010 | 0.008–0.012 | Assumption |

| Weighted average | 0.0077 | 0.0070–0.0085 | Calculation based on above |

| Risk of ulcer recurrence: | |||

| Compression stockings vs. no compression stockings | 0.43 | 0.27–0.69 | Vandongen & Stacey, 200028 |

| Probability of ulcer healing with compression bandages | 0.163 | 0.147–0.179 | Pham et al, 201240 |

| Probability of infection | 0.05 | 0.1–0.01 | Carter et al, 201449 |

Ranges were used in one-way sensitivity analyses.

In the reference case analysis, we assume no one starts on support; therefore, this value is used only in the sensitivity analyses.

In the compression stockings arm of our model, people may be prescribed stockings of different compression pressures (18–24 and 25–35 mm Hg). We used expert opinion (Alexandria Crowe, written communication, Dec 22, 2017; David Keast, written communication, Jan 1, 2018) to estimate the distribution of compression classes prescribed in Ontario. To test the robustness of our model, we varied the distribution in sensitivity analysis, including an assumption that some individuals start compression at support level. Among individuals wearing stockings, the 5-year probability of nonadherence was obtained from an RCT conducted by Nelson et al.27 In the RCT, 42% of people with high pressure stockings and 28% with low pressure stockings did not adhere to their prescribed class of compression stockings. We calculated the monthly probability of nonadherence and assumed that it remained constant over the 5-year time horizon. People who did not adhere with the prescribed treatment were switched to lower pressure stockings as described previously (people at the support level went to no stockings).

We used data from a randomized controlled trial with a 5-year follow-up conducted in Scotland27 to determine ulcer recurrence rates. We converted 5-year ulcer recurrence rates to monthly transition probabilities (Appendix 4, Table A8). In people consistently receiving support stockings (14–17 mm Hg), we used expert opinion to estimate ulcer recurrence rates that are higher than in those consistently receiving low pressure (18–24 mm Hg) compression stockings (Laura Teague, written communication, Jan 16, 2018).

To determine the ulcer recurrence rate in the no compression stockings arm of our model, we obtained the relative risk of ulcer recurrence from our clinical evidence review based on an Australian randomized control trial.28 The authors compared compression stockings with no compression stockings and reported the time to ulcer recurrence over a 2-year follow-up. We multiplied the inverse relative risk by the weighted probability of ulcer recurrence in the compression stockings arm to derive ulcer recurrence in the no compression stocking group. We determined the weighted probability of ulcer recurrence based on the distribution of people in each compression class at the beginning of the model multiplied by the corresponding probability of ulcer recurrence. We assumed that all people with a recurred ulcer were treated with bandages and were adherent to treatment. We obtained the probabilities of acute ulcer healing from the Canadian Bandaging Trial.40 This trial followed 424 people with venous insufficiency and a healed leg ulcer, who were ≥ 65 years of age, for 1 year.

Infection rates were estimated based on a previous economic model.49 We assumed that patients would recover from infection after 1 month.

Lastly, our model accounted for age-dependent background mortality in Ontario. We used the results of a 5-year prospective cohort study showing that survival in people with venous ulcers was not significantly different from control50 to assume a mortality rate that is the same for all health states.

Utility Parameters

We quantified health outcomes as QALYs. The utility values used to derive QALYs can be found in Table 10. These values were obtained by Pham et al,40 who collected health utility data from 424 people with healed or active venous leg ulcers using the EQ5D questionnaire. We assumed the utility of an infected ulcer to be the same as an unhealed ulcer (Laura Teague, written communication, Jan 16, 2018). We varied the utility of infected ulcers in sensitivity analyses.

Table 10:

Utility Parameters Used in the Economic Model

| Health State | Utility (Base Case) | Rangea | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recurred ulcer | 0.77 | 0.74–0.79 | Pham et al, 201240 |

| Healed ulcer | 0.87 | 0.79–0.94 | Pham et al, 201240 |

| Infected ulcer | 0.77 | 0.70–0.90 | Assumption |

Ranges were used in one-way sensitivity analyses.

Costs and Resource Use

All cost and resource use parameters included in our study were obtained from consultation with experts, the Ontario Schedule of Benefits for Physician Services, the Ontario drug benefit formulary, Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario, an online compression stocking vendor, and the Canadian Bandaging Trial (see Table 11).

Table 11:

Resource Utilization and Costs Used in the Economic Model

| Variable | Value (Reference Case)a | Rangea,b | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healed ulcer health state resource use and costs | |||

| Compression stockings cost: | |||

| High pressure (25–35 mm Hg) | $82.1 | $54.0–$110.0 | |

| Low pressure (18–24 mm Hg) | $66.9 | $43.2–$91.8 | |

| Support (13–17 mm Hg) | $33.1 | $25.2–$44.2 | Vendor51 |

| Annual pairs of compression stockings required for preventing venous leg ulcer | 3 | 2–4 | Alexandria Crowe, written communication, Dec 22, 2017 Afsaneh Alavi, written communication, Jan 7, 2018 |

| Total monthly stockings cost: | |||

| High pressure (25–35 mm Hg) | $20.5 | $9.0–$36.7 | Calculation based on above |

| Low pressure (18–24 mm Hg) | $16.7 | $7.2–$30.6 | Calculation based on above |

| Support (13–17 mm Hg) | $8.3 | $4.2–$14.7 | Calculation based on above |

| Nursing cost: | |||

| Nurse hourly rate | $40.8 | $34.1–$45.2 | RNAO,52 includes 13% benefits; ONA Collective agreement53 |

| Length of each nursing visit | 30 min | 20–40 min | Alexandria Crowe, written communication, Dec 22, 2017 |

| Cost per nursing visit | $20.4 | $11.4–$30.1 | Calculation based on above |

| Annual number of nursing visits | |||

| Compression stockings | 1 | 0–2 | Alexandria Crowe, written communication, Feb 8, 2018; David Keast, written communication, Feb 14, 2018 |

| No compression stockings | 1 | 0–2 | Alexandria Crowe, written communication, Feb 8, 2018; David Keast, written communication, Feb 14, 2018 |

| Total monthly nursing cost: | |||

| Compression stockings | $1.7 | $0.0–$5.0 | Calculation based on above |

| No compression stockings | $1.7 | $0.0–$5.0 | Calculation based on above |

| Physician cost: | |||

| Family physician repeat consultation Annual physician visits |

$45.9 | Schedule of benefits54 (Code A006) | |

| Compression stockings | 1 | 0–2 | Alexandria Crowe, written communication, Feb 8, 2018; David Keast, written communication, Feb 14, 2018 |

| No compression stockings | 1 | 0–2 | Alexandria Crowe, written communication, Feb 8, 2018; David Keast, written communication, Feb 14, 2018 |

| Total monthly physician cost: | |||

| Compression stockings | $3.8 | $0–$7.7 | Calculation based on above |

| No compression stockings | $3.8 | $0–$7.7 | Calculation based on above |

| Total monthly cost in healed ulcer health state: | |||

| Compression stockings | |||

| High pressure (25–35 mm Hg) | $26.1 | $9.0–$49.3 | Calculation based on above |

| Low pressure (18–24 mm Hg) | $22.2 | $7.2–$43.3 | Calculation based on above |

| Support (13–17 mm Hg) | $13.8 | $4.2–$27.4 | Calculation based on above |

| No compression stockings | $5.5 | $0–$12.7 | Calculation based on above |

| Recurred ulcer health state resource use and costs | |||

| Total monthly cost in recurred ulcer health state | $128 | $116–$149 | Pham et al. 201240 |

| Infected ulcer health state resource use and costs | |||

| Monthly cost of recurred ulcer | $128 | $116–$149 | Pham et al. 201240 |

| Additional physician cost: | |||

| Debridement of ulcer | $20 | Schedule of benefits,54 (Code Z080) | |

| Monthly visits, debridement of ulcer, n | 1 | 0–2 | |

| Application of Unna's paste | $14.9 | Schedule of benefits,54 (Code Z200) | |

| Monthly visits, application Unna's paste, n | 4 | 2–6 | |

| Total additional monthly physician cost | $79.6 | $29.8–$129.4 | Calculation based on above |

| Antibiotic cost: | |||

| 1st line | |||

| Keflex (cephalexin monohydrate) 500 mg, 4 times per d for 1 wk | $15.2 | $10.0–$30.0 | Ontario drug benefit formulary55 |

| 2nd linec | |||

| Clindamycin 300 mg, 3 times per d for 1 wk | $9.3 | $7.0–$12.0 | Ontario drug benefit formulary55 |

| 3rd linec | |||

| Azithromycin 500 mg for 1 d, then 250 mg/d for 4 d | $7.8 | $5.0–$10.0 | Ontario drug benefit formulary55 |

| Total monthly cost in infected ulcer health state | $222.9 | $155.7–$308.5 | Calculation based on above |

All costs given in 2018 Canadian dollars.

Ranges were used in one-way sensitivity analyses.

2nd and 3rd line therapy costs were used in scenario analyses.

To determine the monthly cost in each health state, we multiplied the expected resource use by unit costs (Table 11). In the healed ulcer health state, we included the costs of compression stockings (if applicable) and visits with health care professionals. Several types of health care professional may be involved in the prescribing and fitting of stockings. We included the costs of a physician and a nurse but acknowledge that, depending on the health care setting, these costs may vary. The cost in the recurred ulcer health state was obtained from the Canadian Bandaging Trial.40 In this trial, people with venous leg ulcers were treated over a 12-month period. We included the community care costs and visit costs to outpatient services, family physicians, specialists, and emergency rooms from the trial. Finally, in the infected ulcer health state, we included the costs associated with having a recurred ulcer (i.e., recurred ulcer health state) and an infection (i.e., additional physician and antibiotic costs). All costs are inflated, where applicable, and reported in 2018 Canadian dollars.

Analysis

In the reference case analysis, we applied a probabilistic approach and used actual values or mean values and distributions as the model inputs (Appendix 4, Table A7). We presented the results as incremental costs (difference in costs) and incremental QALYs (difference in QALYs) of compression stockings compared with no compression stockings.

We performed sensitivity analyses to address the uncertainty of model inputs and clinical scenarios. We assessed variability and uncertainty in several ways.

Probabilistic Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) by assigning distributions to model parameters, where applicable. In the PSA, because cost data are skewed and cannot be negative,56 we used gamma distributions to represent the uncertainty of the cost parameters. We used beta distributions for probabilities and utilities because those estimates are confined to a range of 0 to 1.57 Input parameters used for our PSA are presented in Table A7 (Appendix 4). In Monte Carlo simulations, all parameters were randomly sampled from their assigned distributions, for a cohort of 1,000 patients. We presented the results graphically and then estimated the likelihood of each treatment strategy being optimal across a range of willingness-to-pay thresholds.

One-Way Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted one-way sensitivity analyses using the plausible ranges of our model inputs (Tables 9–11). This allowed us to examine the influence of individual parameters on our results.

Scenario Analyses

Our scenario analyses examined the robustness of our results given increased nonadherence, variation in health care service use, a lifetime horizon, and more expensive treatments for infection.

Scenario 1: All Nonadherent Patients Do Not Wear Compression Stockings

In our reference case analysis, we assumed that nonadherent patients will switch to stockings with lower compression. In scenario 1, we assume that people who are nonadherent would stop wearing stockings entirely. In this scenario, nonadherent patients incur the same costs as people in the no compression stockings arm.

Scenario 2: Greater Health Care Service Use by People Using Compression Stockings

In our reference case analysis, we assumed that all patients with a healed venous leg ulcer will have the same annual number of visits with health care professionals. This could underestimate the number of visits by people using compression stockings if people must connect with their health care provider more often (e.g., for new compression stockings, to switch pressure). In scenario 2, we assumed that people using compression stockings will have one additional nursing and physician visit per year than people who do not use compression stockings.

Scenario 3: Application of Lifetime Horizon

In our reference case analysis, we used a 5-year time horizon. This was based on the follow-up time of the RCT that provided our ulcer recurrence rates.27 The occurrence of venous leg ulcers is a chronic condition; therefore, in scenario 3, we examine the costs and effectiveness of compression stockings on a lifetime horizon.

Scenario 4: Intensive Infection Treatment

In our reference case analysis, we assumed that all patients whose leg venous ulcers were infected were treated by first-line therapy (cephalexin, see Table 11). In scenario 4, we assume that patients will not be treated with first line therapy, but instead are treated using second-(clindamycin) and third-line (azithromycin) therapies.58

Generalizability

The findings of this economic analysis cannot be generalized to all people with venous leg ulcers.

Expert Consultation

We solicited expert consultation on the resource use and costs associated with the use of compression stockings. The consultation included health care professionals who had experience working with people with venous leg ulcers. The role of the expert advisors was to advise on compression stocking use for the prevention of venous leg ulcer recurrence and the typical treatment trajectories of patients.

Results

Reference Case Analysis

The results from the reference case cost–utility analysis are presented in Table 12. On average, costs and QALYs were higher in people treated with compression stockings compared with usual care (no compression stockings). We estimated that the ICER was $27,300 per QALY and therefore that stockings can be considered cost-effective below a willingness-to-pay amount of $27,300 per QALY.

Table 12:

Reference Case Analysis Results

| Strategy | Average Total Costs (95% CI) | Incremental Costa (95% CI) | Average Total Effects, QALYsa(95% CI) | Incremental Effect,a QALYs (95% CI) | ICER, $/QALY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No compression stockings | 971 (342–2,197) | 4.040 (3.870–4.187) | |||

| Compression stockings | 1,518 (1,204–2,159) | 546 (−326 to 1,206) | 4.060 (3.891–4.202) | 0.02 (0.00–0.073) | 27,300 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

Incremental cost = average cost (strategy B) – average cost (strategy A).

Incremental effect = average effect (strategy B) – average effect (strategy A).

Note: All costs in 2018 Canadian dollars.

Sensitivity Analysis

Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis

The majority (97.1%) of our simulations showed that compression stockings were more effective than no compression stockings. We also found that, in 8.5% of simulations, compression stockings were both more effective and less costly than no compression stockings.

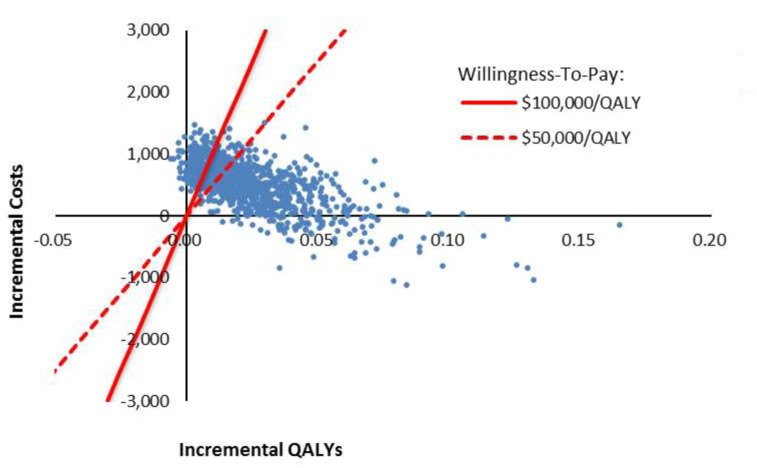

Compression stockings were cost-effective below willingness-to-pay amounts of $50,000 per QALY and $100,000 per QALY in 70.4% and 85.8% of simulations, respectively.

Figure 5 illustrates the uncertainty around the incremental costs and incremental QALYs of compression stockings compared with no compression stockings.

Figure 5: Incremental Costs Versus Incremental Quality-Adjusted Life-Years, Compression Stockings Versus No Compression Stockings.

Abbreviation: QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

One-Way Sensitivity Analysis

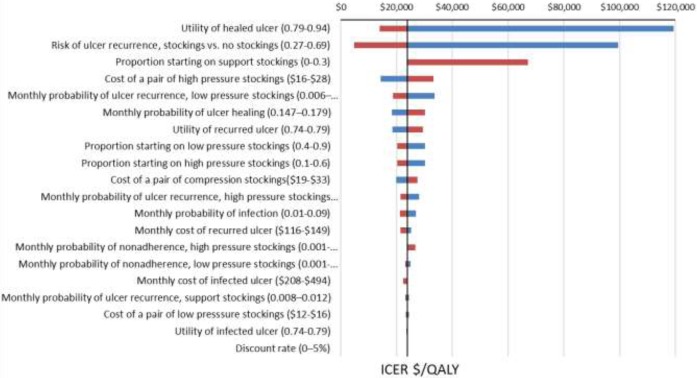

Figure 6 presents the results of the one-way sensitivity analysis. When the utility of a healed ulcer was decreased, the ICER increased to more than $100,000 per QALY. Additionally, when the risk of ulcer recurrence for people with compression stockings or the proportion of people wearing lower-pressure (support) stockings was increased, the ICER increased to more than $50,000 per QALY.

Figure 6: One-Way Sensitivity Analysis, Reference Case, Compression Stockings Versus No Compression Stockings.

Abbreviations: ICER, incremental quality-adjusted life-year; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

Scenario Analysis

Table 13 presents the results from the scenario analysis. The ICER increased to $48,229 per QALY when we assumed people using compression stockings would visit health care providers more frequently than people not using stockings. The ICERs did not change dramatically across other scenarios.

Table 13:

Scenario Analysis Results, Stockings Versus No Stockings

| Scenario | Incremental Cost ($) | Incremental Effect, QALYs | Results ($/QALY) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1: All nonadherent patients do not wear compression stockings | 495 | 0.020 | 24,750 |

| Scenario 2: Greater health care service use by people using compression stockings | 1,115 | 0.023 | 48,229 |

| Scenario 3: Application of lifetime horizon | 1,568 | 0.084 | 18,667 |

| Scenario 4: Intensive infection treatment | 549 | 0.023 | 23,767 |

Discussion