Abstract

Background

Major depression is defined as a period of depression lasting at least 2 weeks characterized by depressed mood, most of the day, nearly every day, and/or markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities. Anxiety disorders encompass a broad range of disorders in which people experience feelings of fear and excessive worry that interfere with normal day-to-day functioning.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a form of evidence-based psychotherapy used to treat major depression and anxiety disorders. Internet-delivered CBT (iCBT) is structured, goal-oriented CBT delivered via the internet. It may be guided, in which the patient communicates with a regulated health care professional, or unguided, in which the patient is not supported by a regulated health care professional.

Methods

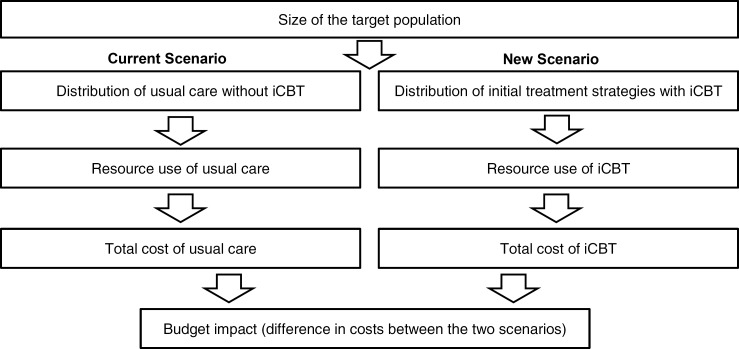

We conducted a health technology assessment, which included an evaluation of clinical benefit, value for money, and patient preferences and values related to the use of iCBT for the treatment of mild to moderate major depression or anxiety disorders. We performed a systematic review of the clinical and economic literature and conducted a grey literature search. We reported Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) ratings if sufficient information was provided. When other quality assessment tools were used by the systematic review authors in the included studies, these were reported. We assessed the risk of bias within the included reviews. We also developed decision-analytic models to compare the costs and benefits of unguided iCBT, guided iCBT, face-to-face CBT, and usual care over 1 year using a sequential approach. We further explored the lifetime and short-term cost-effectiveness of stepped-care models, including iCBT, compared with usual care. We calculated incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) from the perspective of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and estimated the 5-year budget impact of publicly funding iCBT for mild to moderate major depression or anxiety disorders in Ontario. To contextualize the potential value of iCBT as a treatment option for major depression or anxiety disorders, we spoke with people with these conditions.

Results

People who had undergone guided iCBT for mild to moderate major depression (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.83, 95% CI 0.59–1.07, GRADE moderate), generalized anxiety disorder (SMD = 0.84, 95% CI 0.45–1.23, GRADE low), panic disorder (small to very large effects, GRADE low), and social phobia (SMD = 0.85, 95% CI 0.66–1.05, GRADE moderate) showed a statistically significant improvement in symptoms compared with people on a waiting list. People who had undergone iCBT for panic disorder (SMD= 1.15, 95% CI: 0.94 to 1.37) and iCBT for social anxiety disorder (SMD=0.91, 95% CI: 0.74–1.07) showed a statistically significant improvement in symptoms compared with people on a waiting list. There was a statistically significant improvement in quality of life for people with generalized anxiety disorder who had undergone iCBT (SMD = 0.38, 95% CI 0.08–0.67) compared with people on a waiting list. The mean differences between people who had undergone iCBT compared with usual care at 3, 5, and 8 months were −4.3, −3.9, and −5.9, respectively. The negative mean difference at each follow-up showed an improvement in symptoms of depression for participants randomized to the iCBT group compared with usual care. People who had undergone guided iCBT showed no statistically significant improvement in symptoms of panic disorder compared with individual or group face-to-face CBT (d = 0.00, 95% CI −0.41 to 0.41, GRADE very low). Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference in symptoms of specific phobia in people who had undergone guided iCBT compared with brief therapist-led exposure (GRADE very low). There was a small statistically significant improvement in symptoms in favour of guided iCBT compared with group face-to-face CBT (d= 0.41, 95% CI 0.03–0.78, GRADE low) for social phobia. There was no statistically significant improvement in quality of life reported for people with panic disorder who had undergone iCBT compared with face-to-face CBT (SMD = −0.07, 95% CI −0.34 to 0.21).

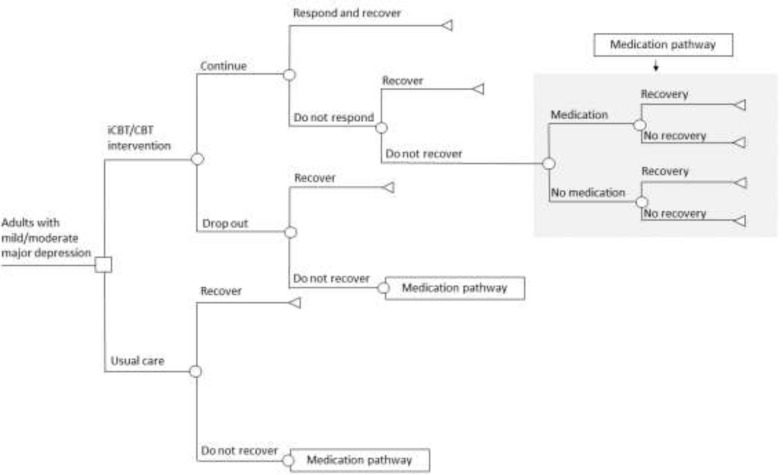

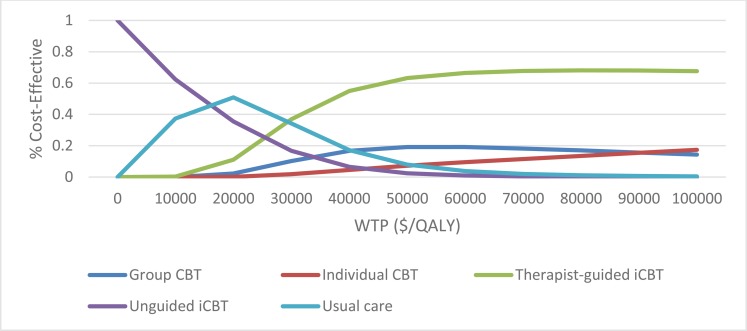

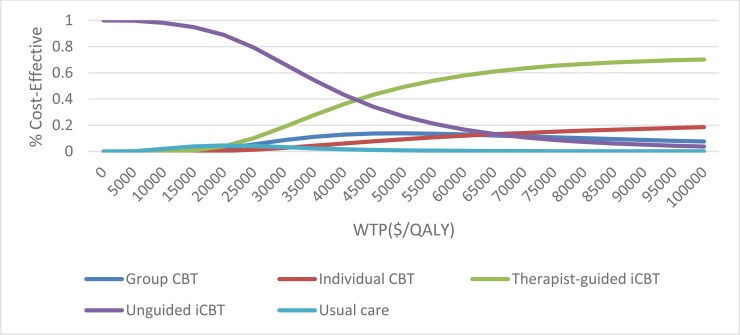

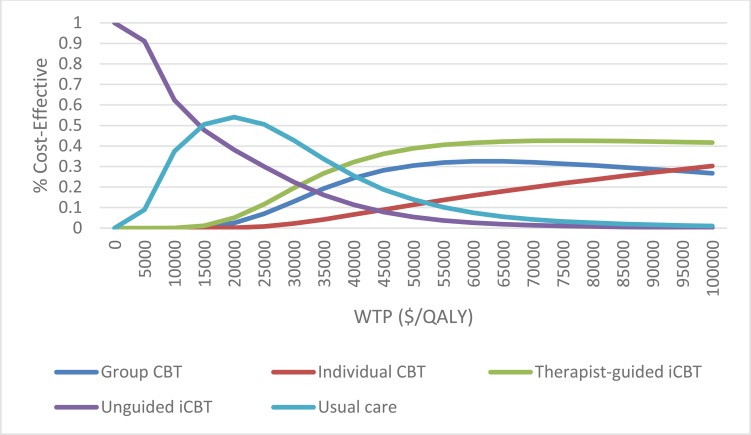

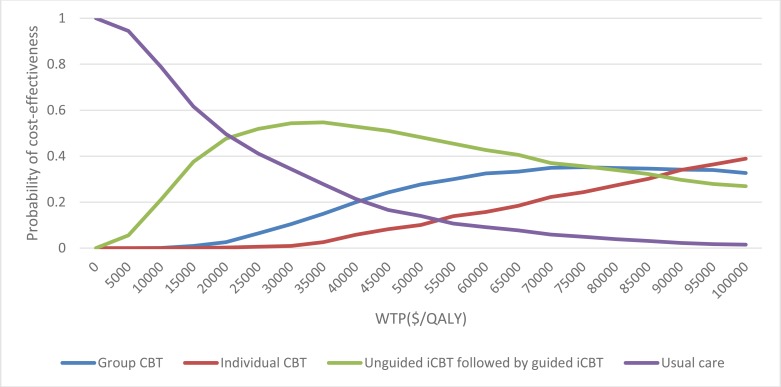

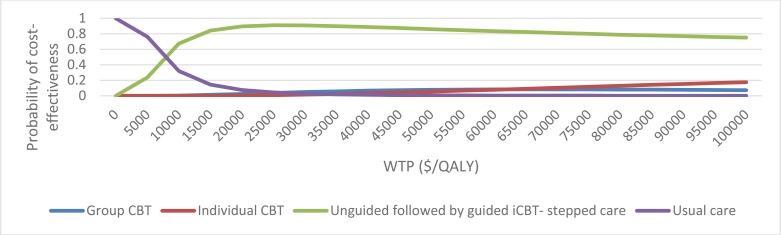

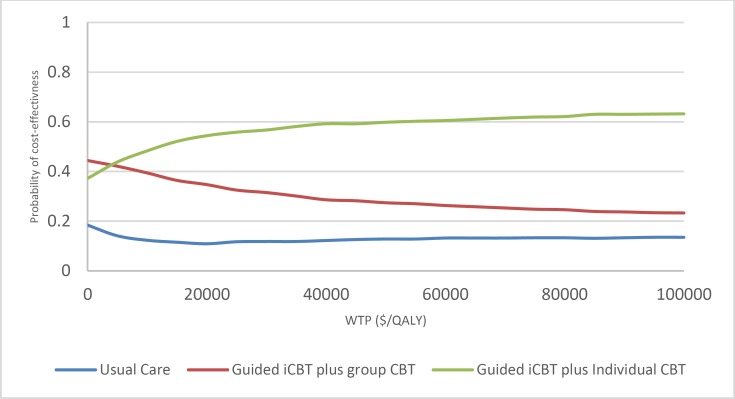

Guided iCBT was the optimal strategy in the reference case cost–utility analyses. For adults with mild to moderate major depression, guided iCBT was associated with increases in both quality-adjusted survival (0.04 quality-adjusted life-years [QALYs]) and cost ($1,257), yielding an ICER of $31,575 per QALY gained when compared with usual care. In adults with anxiety disorders, guided iCBT was also associated with increases in both quality-adjusted survival (0.03 QALYs) and cost ($1,395), yielding an ICER of $43,214 per QALY gained when compared with unguided iCBT. In this population, guided iCBT was associated with an ICER of $26,719 per QALY gained when compared with usual care. The probability of cost-effectiveness of guided iCBT for major depression and anxiety disorders, respectively, was 67% and 70% at willingness-to-pay of $100,000 per QALY gained. Guided iCBT delivered within stepped-care models appears to represent good value for money for the treatment of mild to moderate major depression and anxiety disorders.

Assuming a 3% increase in access per year (from about 8,000 people in year 1 to about 32,000 people in year 5), the net budget impact of publicly funding guided iCBT for the treatment of mild to moderate major depression would range from about $10 million in year 1 to about $40 million in year 5. The corresponding net budget impact for the treatment of anxiety disorders would range from about $16 million in year 1 (about 13,000 people) to about $65 million in year 5 (about 52,000 people).

People with depression or an anxiety disorder with whom we spoke reported that iCBT improves access for those who face challenges with face-to-face therapy because of costs, time, or the severity of their condition. They reported that iCBT provides better control over the pace, time, and location of therapy, as well as greater access to educational material. Some reported barriers to iCBT include the cost of therapy; the need for a computer and internet access, computer literacy, and the ability to understand complex written information. Language and disability barriers also exist. Reported limitations to iCBT include the ridigity of the program, the lack of face-to-face interactions with a therapist, technological difficulties, and the inability of an internet protocol to treat severe depression and some types of anxiety disorder.

Conclusions

Compared with waiting list, guided iCBT is effective and likely results in symptom improvement in mild to moderate major depression and social phobia. Guided iCBT may improve the symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder compared with waiting list. However, we are uncertain about the effectiveness of iCBT compared with individual or group face-to-face CBT. Guided iCBT represents good value for money and could be offered for the short-term treatment of adults with mild to moderate major depression or anxiety disorders. Most people with mild to moderate depression or anxiety disorders with whom we spoke felt that, despite some perceived limitations, iCBT provides greater control over the time, pace, and location of therapy. It also improves access for people who could not otherwise access therapy because of cost, time, or the nature of their health condition.

OBJECTIVE

This health technology assessment looked at the effectiveness, safety, cost-effectiveness, budget impact of publicly funding, and patient preferences and values associated with internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) for the treatment of mild to moderate major depression and anxiety disorders.

This health technology assessment has been registered on PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42018096042), available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO.

BACKGROUND

Health Condition

Major depression is one of the most common mental illnesses, imposing a huge human and economic burden on people and society. Each year, about 7% of people in Canada meet the diagnostic criteria for major depression, and about 13% to 15% of these people will experience major depression for the rest of their lives.1 The essential feature of major depression is the occurrence of one or more major depressive episodes, defined as periods lasting at least 2 weeks characterized by depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, and/or a markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities.2 To receive a diagnosis of major depression, within the same 2-week period a person must experience five or more symptoms from the criteria for a major depressive episode as described in the current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).3

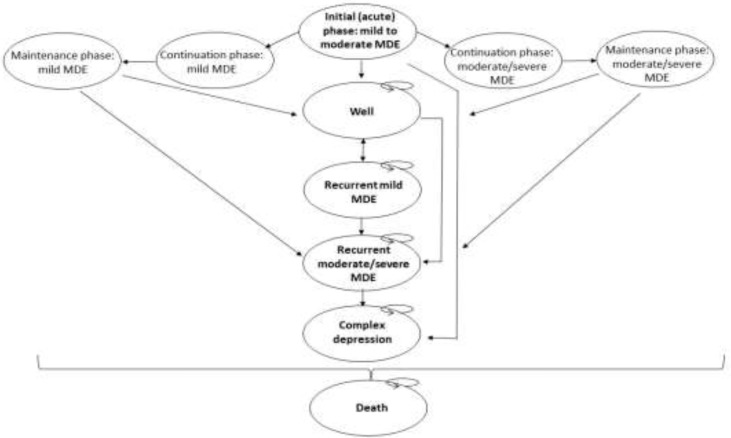

Major depression is both chronic (lasting 3 months or more) and episodic (consisting of separate episodes) in nature. It consists of initial phases (i.e., the acute and continuation phases, each lasting approximately 3 months) and a maintenance phase (lasting approximately 6 to 24 months, with an average 9 to 12 months).2,4–6 The category of anxiety disorders includes a broad range of disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (with and without agoraphobia), social anxiety disorder, and specific phobias (common phobias include fear of animals, insects, germs, heights, thunder, driving, public transportation, flying, dental or medical procedures, and elevators). People with anxiety disorders experience feelings of fear and excessive worry that impacts their overall well-being and functioning. The DSM classifies post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) outside of the category of anxiety disorders.7,8 Anxiety disorders can exist in isolation or coexist with other anxiety and depressive disorders.9,10

Clinical Need and Target Population

Approximately 11.3% of the Canadian population have been classified as meeting criteria for major depression at some point in their life.2,11 Major depression affects not only individuals and families but also occupational functioning, through absenteeism and presenteeism (loss of productivity from attending work while unwell).2 Major depression also negatively affects people's ability to perform personal activities such as parenting and housekeeping.

As of 2006, the lifetime prevalence rates of panic disorder, agoraphobia, and social phobia in Canada were 3.7%, 1.5%, and 8.1%, respectively.12 One Ontario study estimated that 12% of adults between the ages of 15 and 64 years—9% of men and 16% of women—experience an anxiety disorder during any 12-month period.12

Current Treatment Options

Treatment for acute major depression consists of pharmacological and psychological interventions. The use of antidepressant medications has increased over the last 20 years, mainly due to the advent of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, as well as newer agents.13 While antidepressants continue to be a mainstay in the treatment of major depression, adherence rates are low, in part because of patients' concerns about side effects and possible dependency. Surveys have demonstrated patients' preference for psychological therapies over antidepressants.13

Psychotherapy is the treatment of mental or emotional illness through psychological methods rather than through drugs. There are many types of psychotherapy. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is an evidence-based, structured, intensive, time-limited, symptom-focused form of psychotherapy recommended for the treatment of major depression and anxiety disorders.14

Cognitive behavioural therapy helps people become aware of how certain negative automatic thoughts, attitudes, expectations, and beliefs contribute to feelings of sadness and anxiety. People undergoing CBT learn how their thinking patterns, which may have developed in the past to deal with difficult or painful experiences, can be identified and changed to reduce unhappiness.14

Barriers to face-to-face CBT include stigmas around people seeking help in person, geography (distance from health care professional), time, and cost. Increasingly, there is a desire to pursue internet delivery as an option to increase access to treatment.15

The treatment of major depression can be divided into acute and maintenance phases.2,4–6 The aim of treatment in the acute and continuation phases is the reduction or elimination (remission) of symptoms and a return to the level of psychological and social functioning (psychosocial functioning) experienced before the onset of major depression.2 The aim of treatment in the maintenance phase is to prevent symptoms from recurring.2

A Health Quality Ontario quality standard on major depression1 recommends that people with major depression have timely access to either antidepressant medication or evidence-based psychotherapy, based on their preference. Clinical guidelines suggest that CBT may be offered as an initial treatment for anxiety disorders. Pharmacological treatment may be considered if the person has a poor response to CBT treatment.16

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend a stepped-care approach that starts with low-intensity treatments such as guided iCBT for people with mild to moderate major depression or anxiety disorders.17 They recommend higher-intensity interventions (face-to-face psychotherapies such as CBT or interpersonal therapy) alone or in combination with medications for people who do not respond to treatment or who progress to more severe depression or anxiety.17

Health Service Under Review

Internet-delivered CBT is based on the principles of CBT, consists of structured modules with clearly defined goals, and is delivered via the internet.14 Although there are many types of iCBT programs, each are goal oriented sessions that typically consist of 8 to 12 modules and can be guided or unguided.14 Internet-delivered CBT programs are made available by computer, smartphone, or tablet, for a fee.14 With unguided iCBT, patients are informed of a website through which they can participate in an online self-directed program. Guided iCBT involves support from a regulated health professional (e.g., social worker, psychologist, psychotherapist, occupational therapist, nurse, or physician). In guided iCBT, people complete modules and communicate (via email, text messages, or telephone calls) their progress to a regulated health professional.14

Current recommendations indicate that iCBT is not appropriate for severely ill people.14

Regulatory Information

Internet-delivered CBT does not require regulatory approval from Health Canada.

Ontario Context

Internet-delivered CBT is not currently publicly funded in a systematic manner in Ontario. Guided iCBT is currently provided by some hospitals and in the private sector. There are several pilot programs underway or recently completed in Canada, funded through public and private sources.

CLINICAL EVIDENCE

Research Question

What are the effectiveness and safety of iCBT for improving outcomes for adults with mild to moderate major depression or anxiety disorders?

Methods

We developed the research questions in consultation with health care providers and clinical experts.

Clinical Literature Search

We performed a literature search on February 15, 2018, to retrieve studies published from January 1, 2000 to the search date. We used the Ovid interface to search the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Health Technology Assessment, National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), and PsycINFO. We used the EBSCOhost interface to search the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL).

Medical librarians developed the search strategies using controlled vocabulary (e.g., Medical Subject Headings) and relevant keywords. We applied a search filter to limit results to systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and health technology assessments. The final search strategy was peer reviewed using the PRESS Checklist.18 We created database auto-alerts in MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL and monitored them for the duration of the assessment period.

We performed targeted grey literature searching of health technology assessment agency websites and PROSPERO. See Appendix 1 for the literature search strategies, including all search terms.

Literature Screening

Two reviewers conducted an initial screening of titles and abstracts using Covidence management software and obtained full-text articles that appeared eligible according to the inclusion criteria. The reviewers then examined the full texts of articles that appeared eligible to identify studies eligible for inclusion.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies

We conducted an overview of systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials. We considered publications to be systematic reviews if they met all the following criteria:

Clearly described inclusion and exclusion criteria

Undertook a reproducible search of two or more electronic literature databases

Assessed and documented the quality of the included randomized controlled trials

We included English-language full-text systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials published between January 1, 2000, and February 15, 2018.

Participants

We included studies of outpatient adults aged 16 years and older with a primary diagnosis of mild to moderate major depression or anxiety disorder according to validated diagnostic instruments such as the DSM, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD), the Centre for Epidemiological Scale for Depression, the Beck Depression Inventory, or the Patient Health Questionnaire, Structured Diagnostic Interview Schedule.1 We included studies of people with a primary diagnosis of anxiety disorder or of mild to moderate major depression coexisting with other mental health conditions (excluding OCD and PTSD).

We excluded studies of people less than 16 years old or had participants with postpartum depression, bipolar disorder, dysthymia, seasonal affective disorder, a psychotic disorder, drug or alcohol dependence–related depression or anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, major depression or anxiety comorbid with physical disorders (e.g., cancer, stroke, or acute coronary syndrome).

Intervention

We included reviews that assessed iCBT. We excluded non-traditional CBT (e.g., mindfulness CBT), transdiagnostic interventions, CBT delivered via bibliotherapy, and CBT described as computerized but for which there was no analysis specifically for iCBT.

Comparators

We included the following comparators:

Face-to-face CBT, defined as individual or group face-to-face CBT

Usual care, defined as any treatment prescribed by a general practitioner

Waiting list, defined as participants receiving iCBT at a later date

Combination of usual care, waiting list, and/or information control

Outcomes of Interest

We included the following outcomes of interest:

Remission of depression or anxiety symptoms (acute phase)

Prevention of relapse following a successful acute treatment (maintenance phase)

Response to therapy (50% reduction in symptoms from baseline)

Safety

Quality of life

Satisfaction with care

Patient adherence

Data Extraction

Two reviewers extracted relevant data using a data extraction form that included the following study characteristics: study population, inclusion and exclusion criteria, description of the interventions, types of comparators, outcomes, results, and quality assessment as conducted by authors of the systematic reviews. For reviews where a portion of the participants or the intervention did not match the population or intervention of interest, we extracted the results specific to our population or intervention of interest

We contacted authors of the systematic reviews to provide clarification as needed.

Evidence Synthesis

We undertook a narrative summary of the results reported in the included systematic reviews. We did not perform an analysis of primary studies. Results for guided and unguided iCBT were reported separately where available. Unless specified, “iCBT” refers to both guided and unguided iCBT.

Critical Appraisal of Evidence

A single reviewer assessed risk of bias using the Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews (ROBIS) tool.19 See Appendix 2 for details of the ROBIS assessment.

We assessed the quality of the evidence within the included reviews by extracting the review authors' Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) ratings if sufficient information was provided. If other quality assessment tools were used by the systematic review authors in the included studies, these were reported.

Expert Consultation

Consulted experts included physicians in the specialty areas of psychiatry and psychology and regulated mental health professionals. Their role was to review the clinical review plan, contextualize the evidence, and provide feedback on the appropriate use of iCBT.

Results

Literature Search

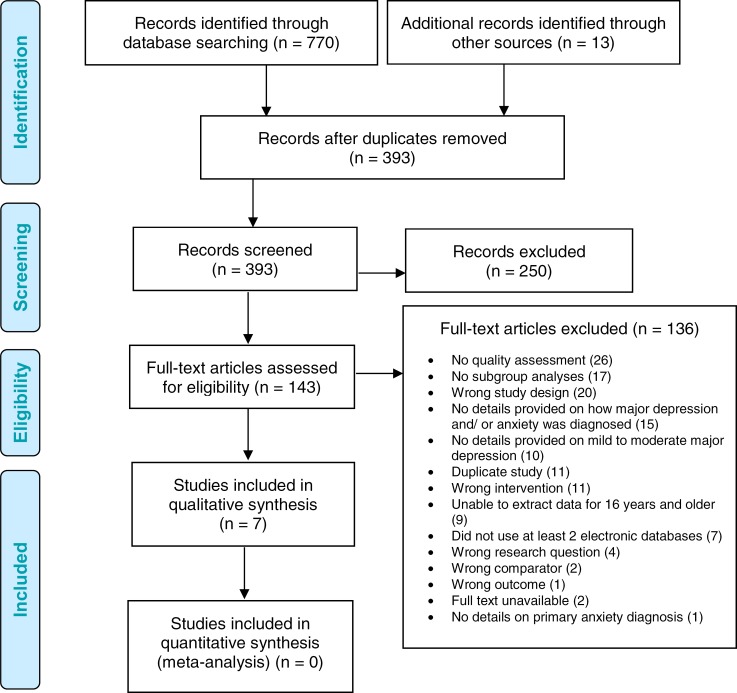

The literature search yielded 393 citations published between January 1, 2000, and February 15, 2018, after removing duplicates. We obtained the full text of 143 articles for further assessment. Seven systematic reviews met the inclusion criteria.7,20–25 The primary reasons for exclusions are provided below. See Appendix 3 for a selected list of studies excluded after full-text review that includes the primary reason for exclusion.

Figure 1 presents the flow diagram for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Figure 1: PRISMA Flow Diagram—Clinical Search Strategy.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al.26

Characteristics of Included Systematic Reviews

We identified one systematic review22 that evaluated iCBT for mild to moderate major depression and five systematic reviews7,21,23–25 that evaluated iCBT for anxiety disorders. One systematic review reported data on both mild to moderate major depression and anxiety disorders.20 There was inconsistency across the systematic reviews in reporting and analyzing the level of support associated with iCBT. One systematic review reported the degree of support as therapist-guided (i.e., clinical support).20 The type of therapist support included email correspondence and weekly phone conversations of 10 to 20 minutes for each participant.

The instruments used to diagnose mild to moderate major depression and anxiety disorders in the inclusion criteria of the included systematic reviews varied. There was additional variation across the scales used to measure the change in symptoms from pre- to post-treatment.

Characteristics of the included systematic reviews are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Included Systematic Reviews

| Author, Year | Objective | Study Design and Methods | Comparators | Outcomes of interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrews et al, 201821 | Replication and extension of 2010 meta-analysis to examine whether computerised therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable, and practical health care. |

Inclusion criteria Adutls ≥18 yrs with a primary diagnosis of either major depression, GAD, PD with or without agoraphobia, or SAD Diagnosis could be determined by a clinician, through telephone interview or by meeting a recognised cut-off on a validated self-report questionnaire. Exclusion criteria Studies of treatments aimed at a range of diagnoses (transdiagnostic studies), and studies of depressive or anxiety symptoms in which no data on the probability of satisfying diagnostic criteria were supplied. |

Waitlist control, information control, care as usual, or placebo. | Subgroup analyses examining the effects of iCBT on change in symptom severity for depression and anxiety disorders. |

| Arnberg et al, 201420 | (1) Is internet-delivered psychological treatment efficacious, safe, and cost-effective for mood and anxiety disorders in children, adolescents and adults? (2) Is internet-delivered treatment noninferior to established psychological treatments? |

Inclusion Criteria Participants: children, adolescents, and adults with anxiety or mood disorders, including major depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, social phobia, PD, GAD, PTSD, OCD, specific phobia, and separation anxiety (in children and adolescents). Intervention: internet-delivered psychological treatments that are based on an explicit psychological theory and not conducted at a clinic. Any support had to be remotely delivered (e.g. email-like messages or telephone). The degree of support was categorized into pure self-help (no support), technician-assisted (e.g., nonclinical), or therapist-guided (i.e., clinical support). Study design: for short-term effects and risk of adverse events, only RCTs were included. For long-term follow-up assessments (i.e., ≥6 mo post-assessment), RCTs and observational studies were included because of the ethical and practical dilemmas of conducting long-term RCTs. For cost-effectiveness data, economic evaluations based on individual-level data and decision models were used. Exclusion Criteria Studies where the participants were selected primarily because of a specific physical illness. |

Any established psychological treatments, waiting list, usual care, or attention control. | Change in symptoms of the primary disorder, adverse events, and cost per effect and per quality-adjusted life year. |

| Kampmann et al, 201625 | Evaluate the efficacy of technology-assisted interventions for individuals with a diagnosis of SAD. |

Inclusion Criteria Participants: lts ≥18 yrs who meet the criteria for a diagnosis of SAD and who had their SAD symptoms assessed during or after the initial assessment. Interventions: treatments targeting SAD symptoms. Study design: RCTs with at least 10 participants per treatment condition, no language restrictions. Exclusion Criteria Dissertation abstracts, reviews, and study protocols. |

Passive control, active control. | Symptoms of depression at post-assessment, efficacy and changes in quality of life. |

| Adelman et al, 20147 | Examine cCBT efficacy for non-PTSD, non-OCD anxiety disorders along multiple dimensions, including treatment efficacy by comparison condition, diagnostic target, level of therapist involvement, study quality, and participant age group. |

Inclusion Criteria RCTs assessing efficacy of cCBT for anxiety disorders, subjects who meet criteria for GAD, PD, SAD, or a specific phobia based on DSM-IV criteria, trials recorded to compare cCBT to waiting list or in-person CBT control condition. Exclusion Criteria OCD and PTSD trials, due to the underlying neuropathology of these conditions, the CBT techniques used to treat these conditions were considered to be sufficiently different from the other anxiety disorders, OCD, and PTSD within diagnostic categories that are distinct from the anxiety disorders. Trials with <10 participants. |

Waiting list or in-person CBT. | Endpoint score on a rating scale used to measure anxiety. Results were stratified by comparator. |

| Kaltenthaler et al, 200822 | Systematically review RCTs of computerized CBT (cCBT) software packages for the treatment of mild to moderate depression. |

Inclusion Criteria Adults with mild to moderate depression, with or without anxiety, as defined by individual studies. Exclusion Criteria Studies on postnatal depression, bipolar disorder, depression with psychotic symptoms or current major depression, or serious suicidal thoughts. |

Current standard treatments including therapist-led CBT, non-directive counselling, primary care counselling, routine management (including drug treatment), and alternative methods of CBT delivery such as bibliotherapy and group CBT. | Improvement in psychological symptoms, quality of life, patient satisfaction. |

| Dedert et al, 201323 | (1) For adults with depressive disorder, PTSD, PD, or GAD, what are the effects of cCBT interventions compared with inactive controls? (2) For cCBT interventions, what level, type, and modality of user support is provided (e.g., daily telephone calls, weekly email correspondence), who provides this support (e.g., therapist, graduate student, peer), what is the clinical context (primary intervention, adjunct), and how is this support related to patient outcomes? Examine the influence of support-related factors on treatment outcomes, including satisfaction, response, and completion. (3) For adults with major depression, PTSD, PD, or GAD, what are the effects of cCBT interventions compared with face-toface therapy? Compare the effectiveness of cCBT with face-to-face CBT. |

Inclusion Criteria Participants: Adults ≥18 yrs with one or more of the following conditions:

Interventions: CBT delivered primarily by a computerized (i.e., electronic) mechanism. Interventions may be self-guided or with clinician support, but the computerized mechanism must be the key intervention that differs from the control group. Study design: RCTs with N > 20. Exclusion Criteria Participants: people with test anxiety, phobias, or SAD. Interventions: interpersonal therapy designed to prevent the onset or relapse of mental illness; interventions that are primarily telemedicine-based (e.g., therapy via video chat or phone interactions, including those by interactive voice response); interventions that use virtual reality as the primary therapeutic mode, do not use the key components of CBT, disease management interventions where CBT is only one component of a more comprehensive intervention, are delivered primarily in face-to-face encounters but supplemented by text messages, or use online materials that do not meet the definition of CBT or CBT-related intervention. |

Usual care not involving psychotherapy; waitlist control; attention/information control, cCBT with a different level of therapist support, face-to-face CBT. | Patient satisfaction, safety, symptom measure, health related quality of life. |

| Richards et al, 201524 | Systematically review and conduct a meta-analysis of internet-delivered psychological therapy for GAD compared to waiting list control groups. |

Inclusion Criteria Adults ≥18yr who have a clinical diagnosis of GAD and may have comorbidity with depression and/or impairment in functioning. Study design: RCTs. |

Waiting list | Clinical efficacy |

Abbreviations: cCBT, computerized CBT; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; iCBT, internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; PD, panic disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SAD, social anxiety disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Mild to Moderate Major Depression

Guided Internet-Delivered CBT Compared to Waiting List

Symptoms and Response to Treatment

Arnberg et al20 identified five randomized control trials comparing guided iCBT to waiting list. People on the waiting list received iCBT after participants randomized to receive iCBT completed the study. Guided iCBT was delivered in the form of email correspondence or telephone conversations lasting about 10 to 20 minutes for each participant on a weekly basis. Participants who received guided iCBT experienced a reduction in symptoms of depression compared with waiting list (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.83, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.59–1.07). This reduction was statistically significant.

Internet-Delivered CBT Compared to Weekly Telephone Calls

Symptoms and Response to Treatment

Kaltenthaler et al22 reported data from one randomized controlled trial that assessed changes in psychological outcomes before and 6 weeks after treatment for participants with mild to moderate major depression randomized to an iCBT program or control group. The study did not specify whether participants received guided or unguided iCBT. The control group received phone calls from interviewers once a week to discuss lifestyle and environmental factors that may have had an influence on depression. The authors found that participants who received iCBT showed a significant reduction in symptoms of depression compared to the control group (mean difference 3.2, 95% CI 0.9–5.4). This randomized controlled trial used the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale as a primary outcome measure of symptoms of depression.

Patient Satisfaction

Kaltenthaler et al22 reported that participants overall accepted the iCBT program.

Patient Dropout and Treatment Adherence

Kaltenthaler et al22 analyzed one randomized controlled trial that reported on patient dropout when iCBT was compared with participants who received weekly telephone calls from interviewers about environmental and lifestyle factors that may have had an influence on depression. Of 525 participants randomized, 25.3% dropped out of the iCBT program, and 10% of participants who received weekly telephone calls from interviewers about environmental and lifestyle factors were loss to follow-up.

Internet-Delivered CBT Compared to Usual Care

Symptoms and Response to Treatment

Kaltenthaler et al22 reported data from a randomized controlled trial that assessed change in psychological outcomes before and after treatment for participants with mild to moderate major depression randomized to an iCBT program or usual care. Usual care was defined as whatever treatment the general practitioner prescribed, such as medications, or referral to a counsellor or a health professional. The authors found that the mean score using the Beck Depression Inventory at 3, 5, and 8 months after treatment demonstrated an improvement in symptoms for participants receiving iCBT compared to usual care. The mean difference between iCBT and usual care was −4.3, −3.9, and −5.9 at 3, 5, and 8 months, respectively.22 The negative mean difference at each follow-up signifies improvement in symptoms of depression for participants randomized to the iCBT group compared to usual care.

Patient Satisfaction

Kaltenthaler et al22 reported that participants receiving iCBT were significantly more satisfied with treatment compared to individuals randomized to usual care.22

Patient Dropout and Treatment Adherence

Kaltenthaler et al22 reported data from a randomized controlled trial that assessed patient drop out for participants with mild to moderate major depression randomized to an iCBT program or usual care. Of the 274 participants, 35% dropped out during the study.22 The proportion of participants who were lost to follow-up in the iCBT program versus the usual care program is unclear.

See Table 2 for summary of results for major depression.

Table 2:

Summary of Results of Included Systematic Reviews for Mild to Moderate Major Depression

| Author, Year | No. of Studies/No. of Participants | Results | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guided internet-deliverd CBT compared with waiting list | |||

| Symptoms and Response to Treatment | |||

| Arnberg et al, 201420 | 5 RCTs/159 | SMD = 0.83 (95% CI 0.59–1.07) | GRADE: ⊕⊕⊕ moderate |

| Internet-delivered CBT compared with weekly telephone calls | |||

| Symptoms and Response to Treatment | |||

| Kaltenthaler et al, 200822 | 1 RCT/525 | SMD = 3.2 (95% CI 0.9–5.4) | CASP Tool Randomization method: statistical software program used Masking: no maskedAssessment Power calculation: yes Loss to follow-up loss: number and some reasonsreported |

| Patient Dropout and Treatment Adherence | |||

| Kaltenthaler et al, 200822 | 1 RCT/525 | 25.3% of participants dropped out of the iCBT program;10% of participants dropped out from the control group, who received weekly telephone calls | CASP Tool Randomization method: statistical software program used Masking: no masked assessment Power calculation: yes Loss to follow-up loss: number and some reasons reported |

| Internet-delivered CBT compared with usual care | |||

| Symptoms and Response to Treatment | |||

| Kaltenthaler et al, 200822 | 1 RCT/274 | iCBT vs. usual care 3 mos: −4.3 (95% CI not reported)a 5 mos: −3.9 (95% CI not reported)a 8 mos: −5.9 (95% CI not reported)a |

CASP Tool Randomization: sealed envelopes, stratified for medication and duration of current episode Masking: no masked assessment Power calculation: yes Loss to follow-up: number and some reasons reported |

| Patient Dropout and Treatment Adherence | |||

| Kaltenthaler et al, 200822 | 1 RCT/274 | 35% dropped out during the study | CASP Tool Randomization: SPSS function Masking: no masked assessment Power calculation: yes Loss to follow-up: loss and reasons reported |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; iCBT, internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy; SMD, standardized mean difference.

A positive improvement in symptoms in favour of iCBT. The mean differences were calculated by the authors of the health technology assessment.

Anxiety Disorders

Internet-Delivered CBT Compared to Waiting List

Symptoms and Response to Treatment

Arnberg et al20 identified four randomized controlled trials that reported on changes in symptoms for participants with generalized anxiety disorder. A large statistically significant pooled effect was found for guided iCBT that involved therapist (i.e., clinical) support compared to waiting list (SMD = 0.84, 95% CI 0.45–1.23).

Similarly, Adelman et al7 identified four randomized controlled trials that reported on anxiety symptoms for generalized anxiety disorder. There was a large statistically significant standardized mean difference that showed an improvement in anxiety symptoms for participants who received iCBT compared to waiting list (SMD = 1.06, 95% CI 0.82–1.30).

Arnberg et al20 found small to very large effects in favour of guided iCBT, which involved therapist (i.e., clinical) support, compared to waiting list for individuals with panic disorder.32

Adelman et al7 identified eight randomized controlled trials that reported on panic disorder. The authors found a large statistically significant standardized mean difference showing an improvement in anxiety symptoms for participants who received iCBT compared to waiting list (SMD = 1.15, 95% CI 0.94— 1.37).

Arnberg et al20 reported on changes in symptoms for eight randomized controlled trials on social phobia that compared guided iCBT, which involved therapist (i.e., clinical) support, to waiting list. A large statistically significant pooled effect was found in favour of guided iCBT compared to waiting list (SMD = 0.85, 95% CI 0.66–1.05).

Adelman et al7 identified nine randomized controlled trials that reported on anxiety symptoms for social anxiety disorder. The authors found a large statistically significant standardized mean difference that showed improvement in anxiety symptoms for participants who received iCBT compared to waiting list (SMD = 0.91, 95% CI 0.74–1.07).

Dedert et al23 identified four trials (five comparisons) in people with generalized anxiety disorder and found that those who had undergone iCBT experienced a large statistically significant difference in symptoms of anxiety compared with people on a waiting list (SMD −0.94, 95% CI −1.34 to −0.54).

Quality of Life

Richards et al24 identified two studies on generalized anxiety disorder that reported on the difference in quality of life using the Quality-of-Life Inventory pre- and post-assessment between people receiving iCBT compared to waiting list. Particiapnts that received iCBT had a statistically significant improvement in quality of life at post assessment compared to waiting list (SMD = 0.38, 95% CI 0.08–0.67).

Patient Dropout and Treatment Adherence

Dedert et al23 reported treatment adherence as the percentage of patients completing all planned sessions stratified by the level of support. The authors identified two randomized controlled trials that reported on treatment adherence for generalized anxiety disorder, and there was variation based on the level of support provided alongside iCBT. Support provided alongside iCBT included feedback by a technician (nonlicensed staff) or clinician (licensed professional), based on the participant's previous interactions with the program, and psychoeducation. This type of support was delayed (not live). Live support comprised phone sessions, a scheduled chat on internet forums, or instant messaging with either technicians or clinicians. Seventy-five percent of participants completed all sessions when there was live support, compared to only 11% when support was provided alongside iCBT.23 These results suggest that participants who received instant communication with either technicians or clinicians completed more sessions than those who received delayed communication.

Internet-Delivered CBT Compared to a Combination of Usual Care, Waiting List, and/or Information Control

Symptoms and Response to Treatment

Andrews et al21 identified 12 randomized controlled trials that reported on changes in symptom severity for panic disorder. The control group was comprised of both usual care and waiting list participants. There was a statistically significant improvement in symptoms of panic disorder among participants who received iCBT compared to control groups (Hedges' g = 1.31; 95% CI 0.85–1.76]).

Dedert et al23 identified seven randomized controlled trials that reported on panic disorder. The control group was defined as waiting list, usual care, or attention/information control. Attention/information controls received support or psychoeducation on the symptoms or disorder being targeted. A large SMD, indicative of a significant reduction in symptoms, was found in favour of participants who received iCBT compared to waiting list, usual care, or attention control (SMD = −1.08, 95% CI −1.45 to −0.72).23

Andrews et al21 identified nine randomized controlled trials that reported on improvement in symptoms for generalized anxiety disorder. Internet-delivered CBT demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in symptoms compared to usual care and waiting list (Hedge's g = 0.70, 95% CI 0.39–1.01).

Andrews et al21 also identified 11 randomized controlled trials that reported on changes in symptom severity for social anxiety disorder. Internet-delivered CBT demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in symptoms compared to usual care and waiting list (Hedge's g = 0.92, 95% CI 0.76–1.08).

Quality of Life

Dedert et al23 identified three randomized controlled trials that reported on health-related quality of life for generalized anxiety disorder. A statistically significant standardized mean difference was found in favour of iCBT compared with control (SMD = 0.57, 95% CI 0.27–0.87).23

Dedert et al23 identified six randomized controlled trials that reported on health-related quality of life for panic disorder. A statistically significant standardized mean difference was found in favour of iCBT compared to control (SMD = 0.49; 95% CI 0.23–0.75).

Patient Dropout and Treatment Adherence

Dedert et al23 reported treatment adherence as the percentage of patients completing all planned sessions and as the mean number of sessions completed stratified by the level of support. Dedert et al23 also identified four randomized controlled trials that reported on treatment adherence for panic disorder, and there was variation based on the level of support. Support provided alongside iCBT included feedback provided by a technician (nonlicensed staff) or clinician (licensed professional) based on the participant's previous interactions with the program, and psychoeducation. Live support comprised phone sessions, a scheduled chat on internet forums, or instant messaging with either technicians or clinicians. Eighty percent of participants completed sessions when there was live support, and 24% to 95% of participants completed sessions when there was delayed support.

Internet-Delivered CBT Compared to Face-to-Face Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Symptoms and Response to Treatment

Dedert et al reported23 data on four randomized controlled trials on panic disorder that assessed changes in symptoms. There was variation in the face-to-face CBT ranging from ten 2-hour group sessions in one study and 6 to 12 individual sessions in three other studies. Three randomized controlled trials provided support (e.g., feedback on the participant's previous interactions with iCBT and/or psychoeducation), and one trial used a mobile palmtop as an adjunct to face-to-face CBT. The authors found no statistically significant difference in symptoms of panic disorder for participants who had undergone iCBT compared with those who had undergone face-to-face CBT for three randomized controlled trials (SMD = 0.06, 95% CI −0.19 to 0.31).23 Similarly, one randomized controlled trial that provided iCBT as an adjunct to face-to-face CBT found no difference in symptoms of panic disorder compared with face-to-face CBT (SMD = −0.42, 95% CI −0.87 to 0.02).

Arnberg et al20 found no difference in symptoms for panic disorder between individuals randomized to guided iCBT that included therapist (i.e., clinical) support when compared to group face-to-face CBT.20 Noninferiority was not established as the confidence interval included the predefined noninferiority margin of d = −0.20. Similarly, no difference was found in symptoms of panic disorder between individuals randomized to guided iCBT that included therapist (i.e., clinical) support compared with individual face-to-face CBT. This study was not designed to assess noninferiority.

Arnberg et al20 identified one randomized controlled trial that reported on individuals with social phobia. There was a statistically significant difference in symptoms of social phobia for participants who received guided iCBT that included therapist (i.e., clinical) support when compared to group face-to-face CBT (d = 0.41, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.78).

Quality of Life

Dedert et al23 identified three randomized controlled trials that reported on health-related quality of life for panic disorder, comparing iCBT to face-to-face CBT. There was no statistically significant difference in quality of life for participants who received iCBT compared to face-to-face CBT (SMD = −0.07, 95% CI −0.34 to 0.21).

Internet-Delivered CBT Compared to Active Control

Symptoms and Response to Treatment

Kampmann et al25 reported on symptoms of social anxiety disorder, comparing iCBT with active control. The authors did not define the active control condition.

Internet-delivered CBT demonstrated a small to medium statistically significant improvement in symptoms of social anxiety disorder compared to active control conditions post-assessment (Hedges's g = 0.38, 95% CI 0.13–0.62). Similarly, a small to medium statistically significant improvement in symptoms of social anxiety disorder occurred compared to active control conditions at ≥6 months follow-up (Hedges's g = 0.23, 95% CI 0.04–0.43).25

Quality of Life

Kampmann et al25 found a small statistically significant improvement in quality of life in favour of iCBT compared to active control conditions post-assessment (Hedges'g = 0.30, 95% CI 0.10–0.50).

Internet-Delivered CBT Compared to Passive Control

Symptoms and Response to Treatment

Kampmann et al25 reported on symptoms of social anxiety disorder, comparing iCBT with passive control. However, the authors did not define the passive control condition. The authors of the systematic review reported that, compared with passive control conditions, iCBT demonstrated a large statistically significant improvement in symptoms of social anxiety disorder at post-assessment (Hedges's g = 0.84; 95% CI 0.72–0.97). An exploratory analysis of two studies did not show a statistically significant improvement in symptoms of social anxiety disorder for iCBT relative to passive control conditions until 5 months (Hedges's g = 0.12; 95% CI −0.17 to 0.42).25

Quality of Life

Kampmann et al25 found a moderate statistically significant improvement in quality of life in favour of iCBT compared to passive control (Hedges's g = 0.57; 95% CI 0.2–0.93).

See Table 3 for a summary of results for anxiety disorders.

Table 3:

Summary of Results of Included Systematic Reviews for Anxiety Disorders

| Author, Year | No., Type of Studies/No. of Participants | Results | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internet-delivered CBT compared with waiting list | |||

| Symptoms and Response to Treatment | |||

| Arnberg et al, 201420 |

Generalized anxiety disorder 4 RCTs/132 |

Guided iCBT vs. waiting list SMD = 0.84, 95% CI 0.45–1.23 |

GRADE: ⊕⊕ low |

| Adelman et al, 20147 |

Generalized anxiety disorder 4 RCTs/317 |

iCBT vs. waiting list SMD = 1.06, 95% CI 0.82–1.30 |

Jadad score unclear for the subgroup of studiesa |

| Dedert et al, 201323 |

Generalized anxiety disorder 4 RCTs/321 |

iCBT vs. waiting list SMD = −0.94, 95% CI −1.34 to −0.54 |

Stregnth of evidence: moderate |

| Arnberg et al, 201420 |

Panic disorder 4 RCTs/132 |

Guided iCBT vs. waiting list Small to very large effects |

GRADE: ⊕⊕ low |

| Adelman et al, 20147 |

Panic disorder 8 RCTs/406 |

iCBT vs. waiting list SMD = 1.15, 95% CI 0.94–1.37 |

Jadad score unclear for the subgroup of studiesa |

| Arnberg et al, 201420 |

Social phobia 8 RCTs/356 |

Guided iCBT vs. waiting list SMD = 0.85, 95% CI 0.66–1.05 |

GRADE: ⊕⊕⊕ moderate |

| Adelman et al, 20147 |

Social anxiety disorder 9 RCTs/not specified |

iCBT vs. waiting list SMD = 0.91, 95% CI 0.74–1.07 |

Jadad score unclear for the subgroup of studiesa |

| Quality of Life | |||

| Richards et al, 201524 |

Generalized anxiety disorder 2 RCTs/157 |

SMD = 0.38, 95% CI 0.08–0.67 | Risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration criteria was not reported for the subgroup of studies |

| Patient Dropout/Adherence | |||

| Dedert et al, 201323 |

Generalized anxiety disorder 2 RCTs/137 |

Guided iCBTb: 75% completion Guided iCBTc: 11% completion |

Strength of evidence not reported |

| Internet-delivered CBT compared with a combination of usual care, waiting list, and/or information control | |||

| Symptoms and Response to Treatment | |||

| Andrews et al, 201821 |

Panic disorder 12 RCTs/584 |

Hedges's g = 1.31, 95% CI 0.85–1.8 |

Low/unclear |

|

Social anxiety disorder 11 RCTs/950 |

Hedges's g = 0.92, 95% CI 0.76–1.08 |

Low/unclear | |

|

Generalized anxiety disorder 9 RCTs/1,103 |

Hedges's g = 0.70, 95% CI 0.39–1.0 |

Low | |

|

Panic disorder 7 RCTs/333 |

SMD = −1.08, 95% CI −1.45 to −0.72 |

Strength of evidence: moderate | |

| Quality of Life | |||

| Dedert et al, 201323 |

Generalized anxiety disorder 3 RCTs/176 |

SMD = 0.57, 95% CI 0.27–0.87 | Strength of evidence: low |

|

Panic disorder 6 RCTs/250 |

SMD = 0.49, 95% CI 0.23–0.75 | Strength of evidence: moderate | |

| Patient Dropout and Treatment Adherence | |||

| Dedert et al, 201323 |

Panic disorder 4 RCTs/313 |

80% of participants completed sessions when there was live support; 24–90% completed sessions when there was delayed support | Strength of evidence: not reported |

| Internet-delivered CBT compared with face-to-face CBT | |||

| Symptoms and Response to Treatment | |||

| Arnberg et al, 201420 |

Specific phobia 1 RCT/30 |

Guided iCBT vs. brief therapist-led exposure No change (no effect size reported) |

GRADE ⊕ very low |

|

Social phobia 1 RCT/126 |

Guided iCBT vs. group face-to-face CBT d = 0.41, 95% CI 0.03–0.78 |

GRADE: ⊕⊕ low | |

| Dedert et al, 201323 |

Panic disorder 1 RCT/49 |

Guided iCBT vs. individual face-to-face CBT Not statistically significant |

GRADE: ⊕ very low |

|

Panic disorder 1 RCT/113 |

Guided iCBT vs. group face-to-face CBT d = 0.00 (95% CI −0.41 to 0.41) |

GRADE: ⊕ Very low | |

|

Panic disorder 3 RCTs/248 |

iCBT vs. face-to-face CBT SMD = 0.06, 95% CI −0.19 to 0.31 |

Strength of evidence: moderate | |

| 1 RCT/121 | SMD = −0.42, 95% CI −0.87 to 0.02d | ||

| Quality of Life | |||

| Dedert et al, 201323 |

Panic disorder 3 RCTs/239 |

SMD = −0.07, 95% CI −0.34 to 0.21 | Strength of evidence: moderate |

| Internet-delivered CBT compared with active control | |||

| Symptoms and Response to Treatment | |||

| Kampmann et al, 201625 |

Social anxiety disorder Number of studies not specified/number of participants not specified |

A small to medium effect was found when iCBT was compared with active control conditions at post-assessment (Hedges's g = 0.38, 95% CI 0.13–0.62, SE = 0.13, P < 0.01, k = 8) and at follow-up 2e (Hedges's g = 0.23, 95% CI 0.04–0.43, SE = 0.10, P = 0.02; k = 5) | Risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration criteria was not reported for the subgroup of studies |

| Quality of Life | |||

| Kampmann et al, 201625 |

Social anxiety disorder Number of studies not specified/number of participants not specified |

Hedges's g = 0.30, 95% CI 0.10–0.50, SE = 0.10, P < 0.01, k = 3 | Risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration criteria was not reported for the subgroup of studies |

| Internet-delivered CBT compared to passive control | |||

| Symptoms and Response to Treatment | |||

| Kampmann et al, 201625 |

Social anxiety disorder Number of studies not specified/number of participants not specified |

Hedges's g = 0.84, 95% CI 0.72–0.97, SE = 0.07, P < 0.001, k = 16 Exploratory analysis including only two studies of iCBT relative to passive control conditions at follow-up 1f (Hedges's g = 0.12, 95% CI −0.17 to 0.42, SE = 0.15, P = 0.412, k = 2) |

Risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration criteria was not reported for the subgroup of studies |

| Quality of Life | |||

| Kampmann et al, 201625 |

Social anxiety disorder Number of studies not specified/number of participants not specified |

A medium effect for iCBT compared to passive control (Hedges's g = 0.57, 95% CI 0.21–0.93, SE = 0.31, P < 0.01, k = 2) | Risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration criteria was not reported for the subgroup of studies |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; iCBT, internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy; SE, standard error; SMD, standardized mean difference.

The authors of the health technology assessment were unable to extract the Jadad score for the subgroup of studies.

Real-time interactions with study technicians (nonlicensed staff) or clinicians (licensed professionals), including phone sessions, a scheduled chat on internet forums, or instant messaging.

Real-time communication with technician (nonlicensed staff) or clinician (licensed professionals) was delayed.

Internet-delivered CBT as an adjunct vs. face-to-face CBT.

Follow-up period was defined as 6 months and greater.

Follow-up period was defined as less than 5 months.

Adverse Events

Dedert et al23 planned to assess outcomes of safety of iCBT across disorders (e.g., emergency department visits, hospital admissions related to the disorder being treated, and self-harm behaviors); however, the data were unavailable from the included studies and were not reported by the systematic review authors. No other systematic reviews included in this assessment reported any data on safety.

Discussion

Internet-delivered CBT is one type of psychotherapy for the treatment of mild to moderate major depression and anxiety disorders. Of the seven systematic reviews included in this clinical evidence review, we found little evidence on guided iCBT. None of the systematic reviews presented data on unguided iCBT. One systematic review evaluated the noninferiority of iCBT compared to group face-to-face CBT and individual face-to-face CBT for anxiety disorders.20 Overall, the level of support (guided or unguided) associated with iCBT in the included systematic reviews was limited.

There is moderate-quality evidence suggesting that, compared with waiting list, guided iCBT is effective and likely results in symptom improvement for mild to moderate major depression and social phobia. Compared with waiting list, guided iCBT may also improve the symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder. However, there is uncertainty about the effectiveness of iCBT compared with individual or group face-to-face CBT.

Although there was a statistically significant improvement in quality of life for individuals with generalized anxiety disorder who received iCBT compared to waiting list, these results should be interpreted with caution as the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval (i.e., 0.08) is very close to the zero cut-off. While iCBT demonstrated an improvement in quality of life for people with generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder compared to a combination of usual care, waiting list, and information control, the strength of evidence is low to moderate.

Guided iCBT may provide a promising option for the treatment of mild to moderate major depression and select anxiety disorders. Moreover, iCBT may expand treatment for individuls unable or unwilling to access face-to-face CBT.

Limitations

The characteristics of the study populations and the number of randomized controlled trials for each subgroup analysis varied in the included systematic reviews. Characteristics of the study participants included a high level of educational attainment and employment, and recruitment was via the internet or advertisements.20 The potential selection bias identified limits the generalizability of these findings. Furthermore, results from single-trial efficacy studies conducted on guided iCBT compared to group face-to-face CBT and individual face-to-face CBT for panic disorder, and guided iCBT compared to brief therapist-led exposure for specific phobias have limited external validity due to the small sample sizes.20

We undertook an overview of systematic reviews. There may be randomized controlled trials published since then that we have not captured. A rapid review by CADTH provides an assessment of the randomized controlled trials published since the systematic reviews assessed in this report.27

Conclusions

Compared with usual care, iCBT:

Significantly improves symptoms for mild to moderate major depression (GRADE not conducted)

Compared with waiting list, guided iCBT:

Significantly improves symptoms of mild to moderate major depression (GRADE moderate)

Significantly improves symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder (GRADE low)

Significantly improves symptoms of panic disorder (GRADE low)

Significantly improves symptoms of social phobia (GRADE moderate)

Compared with face-to-face CBT, guided iCBT:

Did not significantly improve symptoms of panic disorder (GRADE very low)

Did not significantly improve symptoms of social phobia (GRADE low)

ECONOMIC EVIDENCE

Research Questions

What is the cost-effectiveness of unguided or guided iCBT compared with face-to-face CBT or usual care in the management of adults with mild to moderate major depression?

What is the cost-effectiveness of unguided or guided iCBT compared with face-to-face CBT or usual care in the management of adults with anxiety disorders?

Methods

Economic Literature Search

We performed an economic literature search on February 21, 2018, for studies published from January 1, 2000, to the search date. To retrieve relevant studies, we developed a search using the clinical search strategy with an economic filter applied.

We created database auto-alerts in MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL and monitored them for the duration of the health technology assessment. We performed a targeted grey literature search of health technology assessment agency websites, PROSPERO, and Tufts Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry. See the Clinical Evidence literature search, above, for further details on methods used. See Appendix 1 for literature search strategies, including all search terms.

Literature Screening

A single reviewer screened titles and abstracts, and, for those studies likely to meet the eligibility inclusion criteria, we obtained full-text articles and performed further assessment for eligibility.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language, full text articles published between January 1, 2000, and the search date

Individual-level economic evaluations conducted alongside randomized controlled trials (i.e., trial-based) or economic analyses based on decision analytic models (i.e., model-based)

Studies in adults with major depression or an anxiety disorder that falls within the DSM-5 criteria

Studies comparing unguided or guided iCBT (by a therapist or a coach) with face-to-face CBT, pharmacologic therapies, treatment as usual, or no treatment (e.g., waiting list or placebo)

Exclusion Criteria

Narrative reviews of the literature, study protocols, guidelines, conference abstracts, commentaries, letters, and editorials

Economic evaluations examining iCBT used solely for the treatment of postnatal depression or depression or anxiety co-occurring with chronic conditions (e.g., depression coexisting with chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, dementia, diabetes mellitus, or inflammatory bowel disease)

Economic evaluations examining the value of non-traditional CBT (e.g., mindfulness CBT), CBT delivered via bibliotherapy, or CBT described as computerized CBT for which no further analysis was done specifically for iCBT

Feasibility studies exploring different models of care for the treatment of major depression or anxiety disorders that do not report economic outcomes

Noncomparative studies reporting the costs of iCBT or cost-of-illness studies

Outcomes of Interest

Incremental costs

Incremental effectiveness outcomes (e.g., quality-adjusted life-years [QALYs], disability-adjusted life-years [DALYs])

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER)

Incremental net benefit (INB)

Data Extraction

We extracted relevant data on the following:

Publication source (i.e., author's name, location, publication year)

Study design

Study population

Interventions and comparators

Outcomes (e.g., health outcomes, costs, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio)

Study Applicability and Limitations

We determined the usefulness of each identified study for decision-making by applying a modified quality appraisal checklist for economic evaluations that was originally developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom to inform development of NICE's clinical guidelines. We modified the wording of the questions to remove references to guidelines and to make it Ontario-specific. Next, we separated the checklist into two sections. In the first section, we assessed the applicability of each study to the research question (directly, partially, or not applicable). A summary is presented in Appendix 4. In the second section, we assessed the limitations (minor, potentially serious, or very serious) of the studies that we found to be directly or partially applicable.

Results

Literature Search

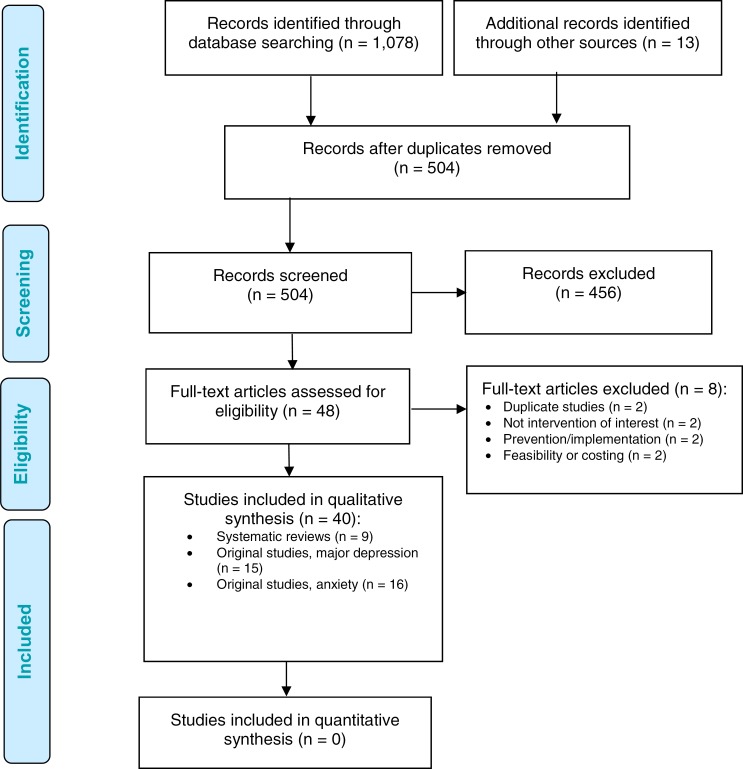

The literature search yielded 504 citations published from January 1, 2000, to February 21, 2018, after removing duplicates. We excluded a total of 456 articles based on information in the title and abstract and obtained 48 potentially relevant articles for further assessment. Forty studies met the inclusion criteria and were assessed to establish the applicability of their findings to the Ontario context. Figure 2 presents the PRISMA diagram for the economic evidence review.

Figure 2: PRISMA Flow Diagram—Economic Search Strategy.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al.26

Review of Included Economic Studies

Of the 40 eligible studies, 9 were systematic literature reviews20,28–35 that examined the cost-effectiveness of iCBT among other psychological therapies for either major depression or anxiety disorders, and 31 were original research studies focusing on the cost-effectiveness of iCBT in adults with major depression (n = 15)36–50 or in adults with an anxiety disorder (n = 16).9,50–64

Systematic Reviews: The Cost-Effectiveness of iCBT for the Management of Major Depression or Anxiety Disorders

We identified nine relevant systematic reviews including data on the potential cost-effectiveness of iCBT published between 2012 and 2018.20,28–35 All reviews examined other psychological treatments in addition to iCBT: four reviews were focused on major depression,28–31 two examined anxiety disorders,32,33 and three reviews examined internet interventions for mental health conditions in general or for mood and anxiety disorders altogether.20,34,35 The reviews examining depression or anxiety disorders included mixed study populations and types of psychological treatments in addition to guided and unguided iCBT, which were examined in a wide range of included studies. In general, results were mixed. Most reviews suggested that iCBT could represent an economically viable treatment alternative over control.30 The one exception, Kolovos et al,30 included individual-level participant data and conducted a meta-analysis and concluded that guided iCBT was not a cost-effective option compared with control. None of the studies described in detail the differences between unguided and guided iCBT, and there was a great variability of cost-effectiveness estimates. We performed our own systematic review of the literature to inform our primary economic evaluation and to gain a better understanding of relevant values for our model input parameters, such as changes in health-related quality of life weights associated with progression of depression and anxiety and with iCBT treatment.

We reviewed all original studies relevant to our research questions. We then compared their study designs, including perspective, the time horizon of analysis, study populations, and comparative strategies. Lastly, we summarized the cost-effectiveness findings. Tables 4 and 5 summarize the characteristics and results of the included original studies.

Table 4:

Results of Economic Literature Review—Cost-Effectiveness of iCBT for the Treatment of Major Depression

| Name, Year, Location | Methods | Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design and Perspective | Population | Interventions/Comparators | Health Outcomes | Costs | Cost-Effectiveness | |

| Duarte et al, 201737; Littlewood et al, 2015,36 United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Romero-Sanchiz et al, 2017,43 Spain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lee et al, 2017,49 Australia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Brabyn et al, 2016,38 United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dixon et al, 2016,39 United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Titov et al, 2015,44 Australia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Geraedts et al, 2015,45 Netherlands |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Solomon et al, 2015,48 Australia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Phillips et al, 2014,41 United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gerhards et al, 2010,46 Netherlands |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Warmerdam et al, 2010,47 Netherlands |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hollinghurst et al, 2010,40 United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kaltenthaler et al, 2006,50 United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| McCrone et al, 2004,42 United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: CCBT, computerized CBT; EVPI, expected value of perfect information; EVPPI, expected value of partial perfect information; GP, general practitioner; iCBT, internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; INB, incremental net benefit; NHS, National Health Service; NICE, National Institute of Health and Care Excellence; NR, not reported; PSS, personal social services; PST, problem-solving therapy; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; RCT, randomized controlled trial; REEACT, Randomised Evaluation of the Effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and Acceptability of Computerised Therapy; ROI, return on investment; SD, standard deviation; SD, standard deviation; TAU, treatment as usual; wtp, willingness to pay.

Table 5:

Results of Economic Literature Review—Cost-Effectiveness of iCBT in the Treatment of Anxiety Disorders

| Name, Year, Location | Methods | Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Design and Perspective | Population | Interventions/Comparators | Health Outcomes | Costs | Cost-Effectiveness | |

| Kumar et al, 2018,63 United States |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| El Alaoui et al, 2017,61 Sweden |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hedman et al, 2016,60 Sweden |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dear et al, 2015,62 Australia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Nordgren et al, 2014,56 Sweden |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hedman et al, 2014,59 Sweden |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hedman et al, 2013,57 Sweden |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health and NICE, 2013,64 United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Joesch et al, 2012,55 United States |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hedman et al, 2011,58 Sweden |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health and NICE, 2011,9 United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bergstrom et al, 2010,54 Sweden |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Titov et al, 2009,53 Australia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| McCrone et al, 2009,52 United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mihalopoulos et al, 2005,51 Australia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kaltenthaler, 2006,50 United Kingdom |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: CALM, Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; CCBT, computerized CBT; DALY, disability-adjusted life-year; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; EQ-5D, European Quality of Life questionnaire in five dimensions; ESEMeD, European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; GP, general practitioner; iCBT, internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; INB, incremental net benefit; NA, not applicable; NHS, National Health Service; NICE, National Institute of Health and Care Excellence; NR, not reported; PSS, personal social services PST, problem-solving therapy; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; RCT, randomized controlled trial; ROI, return on investment; SAD, social anxiety disorder; SD, standard deviation; SF-6D, Short-Form Health Survey in 6 Dimensions; TAU, treatment as usual; wtp, willingness to pay; YLD, years lived with disability.

Original Studies: The Cost-Effectiveness of iCBT for the Management of Mild to Moderate Major Depression

Study Design

Of the 15 included studies (see Table 4), 12 were individual-level cost-effectiveness analyses conducted alongside clinical trials. Six were from the United Kingdom36–42 (the report by Littlewood et al36 was later published by Duarte et al37; it was counted as the same publication in Table 4), one study was from Spain,43 one from Australia,44 and three were from the Netherlands.45–47 Three studies were model-based cost-effectiveness analyses (two from Australia48,49 and one from the United Kingdom50).

Study Population

All economic evaluations were done with adult participants who had major depression, and the majority included mild to moderate disease severity in the inclusion criteria. Prior episodes of major depression and use of medications at baseline was reported by participants in four studies.36–40 One study was specifically conducted in older adults aged 60+ years,44 and another study45 targeted employed individuals (mean age: 43 years).45 The remaining studies recruited participants from hospitals or the general population. All but one study in older Australian adults44 included relatively large samples of about 300 to 700 participants, with the mean age ranging from 34 to 50 years, and with females composing between 50% and 80% of the study populations.

Analysis Perspective

The analysis perspective varied between the studies and may have been affected by the features of each country's health care system. Most studies conducted in the United Kingdom were done from a health sector perspective. Most of the studies done in the Netherlands, Australia, and Spain were done from a societal perspective.

Time Horizon

The duration of follow-up in trial-based cost-effectiveness analyses or of the time horizon in model-based cost-effectiveness analyses was short, ranging from 8 weeks to 12 months in most studies. This indicates a short-term, non-repetitive use of iCBT. Only two cost–utility analyses (one trial-based,36,37 and another model-based50) examined the benefits and costs of 6- to 8-session courses of unguided or coach-guided iCBT over a period of 18 months.

Interventions and Comparators

Unguided iCBT. Six studies used unguided iCBT as an intervention strategy. The unguided iCBT consists of 4 to 8 sessions, along with homework assignments. In most studies, the sessions were designed to be completed weekly. In three individual-level cost-effectiveness studies, usual care was compared with unguided or minimally guided iCBT (where minimal guidance was defined as technical guidance on use of the software).36,37,41,43,46 One study by Gerhards et al46 compared iCBT alone to usual care alone and to iCBT combined with usual care. Another study by McCrone et al42 compared iCBT combined with usual care to usual care alone. Only one model-based study by Solomon et al48 examined the benefits and costs of unguided iCBT to usual care and to face-to-face CBT.48

Guided iCBT. In total, nine studies examined therapist-guided iCBT.38–40,43–45,47,49,50 Durations varied from 6 to 16 sessions completed on a weekly basis, along with homework assignments. In four studies,38,39,47,50 including three from the United Kingdom, iCBT was guided by a coach, a non-regulated mental health worker trained to provide low-intensity CBT. Highly trained regulated therapists (e.g., clinicians or psychologists) were employed in five studies done in Spain,43 the Netherlands,45 Australia44,49 and the UK40. In seven studies, guided iCBT was compared with usual care only. One study47 compared guided iCBT with problem-solving therapy;47 another38 compared guided iCBT supported by a coach (i.e., a non-regulated mental health worker) with unguided iCBT.38

Control Treatment. In general, usual care consisted of treatment provided by a general practitioner and included active surveillance, medications or counselling, and psychoeducation according to country-specific clinical guidelines. Another frequently used control option was waiting list. One study by Phillips et al41 that examined unguided iCBT used a self-help mental health website as a control comparator.41

Cost-Effectiveness Results

In 11 of the 14 included studies, ICER estimates associated with the incremental cost-effectiveness of unguided or guided iCBT were below country-specific willingness-to-pay thresholds, indicating that these types of CBT could be economically attractive options in the management of mild to moderate depression. However, results should be interpreted with caution as there were some uncertainties around the ICER in the probabilistic sensitivity analyses. Depending on the duration and type of cost–utility analysis, the probability of unguided or guided iCBT being cost-effective ranged from 52% to more than 95% (at country-specific willingness to pay thresholds). Moreover, the probability of cost-effectiveness of guided iCBT versus unguided iCBT was 55% at a willingness to pay of £30,000/QALY.38

In most studies, the costs associated with guided iCBT were greater than the cost of usual care; however, the incremental benefits (expressed in QALYs) remained uncertain. For instance, in several studies, unguided or guided iCBT alone was associated with increments of 0.01 to 0.02 QALYs. Comparatively, slightly larger increases of 0.03 to 0.04 QALYs were shown in two studies that examined the cost-effectiveness of guided or unguided iCBT when combined with usual care.40,42 Exceptionally high increases in QALYs were also determined in a modeling study by Kaltenthaler et al50 and an individual-level cost–utility analysis by Romero-Sanchiz.43 In these studies, increments in QALYs were shown to be about 0.08 for guided or unguided iCBT compared with usual care. Lastly, a study by Brabyn et al38 that compared guided to unguided iCBT found a small gain in QALYs of 0.003 with guided iCBT.