Abstract

Purpose

Cancer threatens the social well-being of patients and their informal caregivers. Social life is even more profoundly affected in advanced diseases, but research on social consequences of advanced cancer is scarce. This study aims to explore social consequences of advanced cancer as experienced by patients and their informal caregivers.

Methods

Seven focus groups and seven in-depth semi-structured interviews with patients (n = 18) suffering from advanced cancer and their informal caregivers (n = 15) were conducted. Audiotapes were transcribed verbatim and open coded using a thematic analysis approach.

Results

Social consequences were categorized in three themes: “social engagement,” “social identity,” and “social network.” Regarding social engagement, patients and informal caregivers said that they strive for normality by continuing their life as prior to the diagnosis, but experienced barriers in doing so. Regarding social identity, patients and informal caregivers reported feelings of social isolation. The social network became more transparent, and the value of social relations had increased since the diagnosis. Many experienced positive and negative shifts in the quantity and quality of their social relations.

Conclusions

Social consequences of advanced cancer are substantial. There appears to be a great risk of social isolation in which responses from social relations play an important role. Empowering patients and informal caregivers to discuss their experienced social consequences is beneficial. Creating awareness among healthcare professionals is essential as they provide social support and anticipate on social problems. Finally, educating social relations regarding the impact of advanced cancer and effective support methods may empower social support systems and reduce feelings of isolation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00520-018-4437-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Social well-being, Social consequences, Advanced cancer, Palliative oncology, Informal caregivers, Focus groups

Introduction

Maintaining or improving quality of life (QoL) is a crucial outcome of palliative care. There is much attention for the physical domain of QoL, but the other domains (i.e., emotional, spiritual, and social well-being) receive less attention [1]. Social well-being is important for overall QoL because we are social creatures; people have an innate need to feel connected to other people [2–4]. This connection is the essence of social well-being. Cancer and its treatment can seriously threaten social well-being [5, 6]. Pooled data from multiple studies showed that 45% of cancer patients reported high levels of social difficulty [7] such as problems in social relationships and support [6], feelings of social isolation [8], restriction in social activities [9], challenges in work [10], and responsibilities outside work [11]. Wright and colleagues [12] identified 32 social problems experienced by cancer patients in the following categories: managing at home, health and welfare-services, finances, employment, legal matters, relationships, sexuality and body image, and recreation.

Cancer does not only affect patients, but also their social relations such as partners, friends, and family members. Social relations of patients, who often act as informal caregivers, can help patients cope with the illness’ consequences. Providing informal care is a meaningful task, but it can also be burdensome [13]. Informal caregivers often experience social consequences as a result of their caring activities [14–16]. Moreover, they find it challenging to communicate about the cancer with their social relations [15, 16] and experience negative responses from social relations [14, 17]. Furthermore, informal caregivers appear to participate less in social activities [18, 19] due to feelings of guilt or worry when they are separated from the patient [20]. A recent review showed that informal caregivers also experience positive social consequences of caring for someone with cancer such as an enhanced relationship with the patient [21].

A body of research on social consequences of cancer focused on cancer patients undergoing curative treatment or on cancer survivors. Patients with advanced cancer have received less attention. This is surprising because social life is even more affected in advanced cancer [7]. Patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers are confronted with proximity to death that often changes their perspective on life and influences their social life [22]. Advanced cancer may seriously threaten the social well-being of patients and informal caregivers. However, knowledge on social consequences of advanced cancer including the perspective of patients and their informal caregivers simultaneously is lacking. Therefore, this study aims to explore the social consequences of advanced cancer in patients and their informal caregivers.

Methods

Study design

This qualitative focus group study was embedded within a larger study on quality of life and quality of care as experienced by patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers (eQuiPe study (NTR6584)), conducted in the Netherlands.

Study population

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were diagnosed with colorectal cancer (stage IV and at least two metastasis in liver, peritoneum or lung), lung cancer (stage IV), breast cancer (stage IV with at least visceral or brain metastasis), prostate cancer (stage IV and castration resistant), non-resectable pancreatic cancer, or non-resectable esophageal cancer. Both patients and informal caregivers were eligible if they were 18 years or older and understood the objective of the study. An informal caregiver could participate regardless of patient participation and vice versa. Patients and informal caregivers were not eligible for inclusion if they had a poor expression of the Dutch language, they suffered from dementia, or they had a history of severe psychiatric illness.

Recruitment

Patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers were informed about the study by their treating physician to participate between January 2017 and June 2017 in six Dutch hospitals. The physician asked permission for a research team member to call the patient to give detailed information about the study, address questions, and invite them to participate. Subsequently, when patients and/or informal caregivers agreed to participate, they were invited for a focus group.

Study procedure

Participants were assigned to a focus group based on their availability, and patients and informal caregivers participated in separate focus groups to minimize response bias. A focus group was approximately 90 min and was facilitated by two researchers (JvR and LB). A moderator (JvR) asked the questions, probed, and made sure that all participants were heard, and an observer (LB) listed the proceedings during each focus group (supplement 1). Consecutively, all participants completed a self-administered questionnaire regarding socio-demographics. If participants were not willing to participate in a focus group, an individual interview was offered. Interviews were also conducted separately for patients and informal caregivers. Two patients only wanted to participate with their informal caregiver present during the interview. All focus groups and interviews were audiotaped. After data saturation was reached, no additional focus groups and interviews were organized.

Data analysis

All focus groups and interviews have been transcribed verbatim and analyzed with content analysis using Atlas.ti version 7.5.15. Two researchers (NR and JvR) independently coded a randomly selected transcript and compared results to evaluate consensus. Transcripts were coded by the qualitative thematic analysis approach [23, 24]. Data was analyzed by the open coding procedure [25]. The procedure to confirm uniformity across researchers was repeated four times during data analysis phase. Quotes reflecting social consequences as experienced by patients and informal caregivers were included in the further analysis. Two researchers (JvR and NR) clustered the subcategories to identify main themes. To illustrate important results from the analysis, quotes have been presented followed by an alphanumeric code in brackets where P = patient, C = informal caregiver, FG = focus group, and IV = interview.

Results

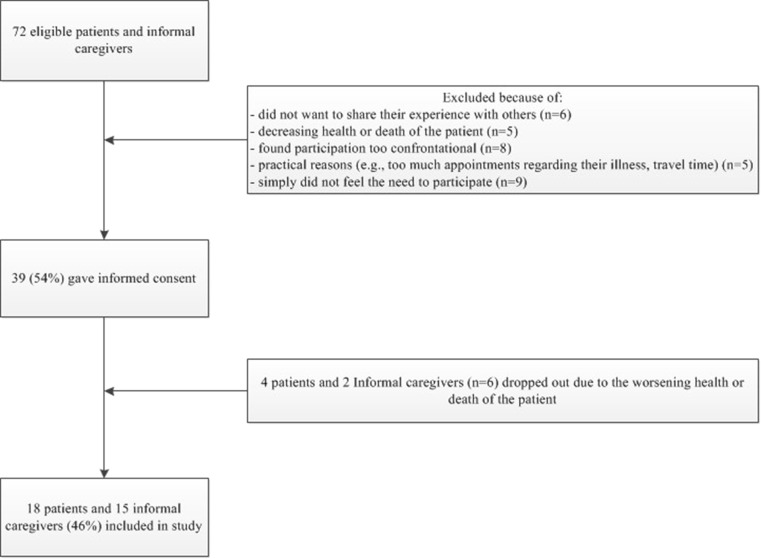

In total, 18 patients and 15 informal caregivers participated in a focus group (n = 23) or in an interview (n = 10) (Fig. 1). Most patients had lung or colorectal cancer and informal caregivers were most often the patients’ partners (Table 1).

I have never been prepared for the social consequences. I found them much bigger and much more serious – so much more all-encompassing than I could ever have imagined. (P7-IV).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart inclusion process

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

| Patients with advanced cancer (n = 18) | Informal caregivers (n = 15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 9 (50%) | 6 (40%) |

| Age | Mean (range) | 59 years (38–76) | 58 years (40–76) |

| Educationa | Low education | 2 (11%) | 4 (27%) |

| Middle education | 6 (33%) | 8 (53%) | |

| High education | 9 (50%) | 3 (20%) | |

| Missing | 1 (6%) | – | |

| Ethnicity | Dutch | 15 (83%) | 15 (100%) |

| French | 1 (6%) | – | |

| Religious beliefs | None | 3 (17%) | 5 (33%) |

| Protestants Christian, active | 2 (11%) | – | |

| Protestants Christian, not active | 1 (6%) | 1 (7%) | |

| Roman Catholic, active | 3 (17%) | 1 (7%) | |

| Roman Catholic, not active | 9 (50%) | 7 (47%) | |

| Other, atheist | – | 1 (7%) | |

| Primary cancer site in patients | Lung | 8 (44%) | 11 (73%) |

| Colorectal | 6 (33%) | 1 (7%) | |

| Breast | 2 (11%) | 2 (13%) | |

| Esophagus | 1 (6%) | 1 (7%) | |

| Prostate | 1 (6%) | – | |

| Time since patient’s diagnosis | 1 year | 5 (28%) | 6 (40%) |

| 2 years | 6 (33%) | 4 (27%) | |

| ≥ 3 years | 5 (28%) | 3 (20%) | |

| Missing | 2 (11%) | 2 (13%) | |

| Relation with patient | Partner | – | 12 (80%) |

| Daughter | 2 (13%) | ||

| Friend | 1 (7%) |

aLow educational level = no education or primary school (e.g., LBO, VBO, LTS, LHNO, VMBO, MBO1), intermediate educational level = lower general secondary education, vocational training or equivalent (e.g., MAVO, VMBO-t, MBO-kort, MBO, MTS, MEAO, HAVO, VWO), high educational level = pre-university education, high vocational training, university (e.g., Hbo-bachelor, Hbo-master, wo-bachelor, wo-master, doctor)

Social consequences of advanced cancer mentioned by patients and informal caregivers were categorized in three main themes: “social engagement,” “social identity,” and “social network” (Table 2).

Table 2.

Social consequences of advanced cancer

| Main theme | Subtheme | Category | Mentioned by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social engagement | Struggle to proceed as normal | Focus on continuing life prior to cancer | p, c |

| More fun activities | p, c | ||

| Caregiving role | c | ||

| Missing out | Missing out on social events | p, c | |

| Consequences of missing out | p | ||

| Work consequences | p, c | ||

| Value of social activities | Daily social activities | p | |

| Personal social activities | c | ||

| Social identity | Cancer is central | Public possession | p |

| One of them | c | ||

| Social talk | p, c | ||

| Seeking anonymity | c | ||

| Being confronted with assumptions | Appearances | p, c | |

| Treated differently | p, c | ||

| Isolation | p | ||

| Stigma | c | ||

| Instructing social ties | p, c | ||

| Social network | Value of social relations | Meaning in life | p, c |

| Instrumental | p | ||

| Changes in the network | Loss of ties | p, c | |

| New ties | p, c | ||

| Quality existing ties | p, c | ||

| Perceived social support | Decreased support over time | p | |

| Delayed support | c | ||

| Lack of emotional support | p, c | ||

| Positive support | c |

p patients, c informal caregivers

Consequences for social engagement

Struggle to proceed with social life as normal

Both patients and informal caregivers emphasized the importance of continuing life prior the cancer diagnosis as much as possible; to strive for normality. “What it means to me is that I want to live my life just as I used to. And I want to make as few concessions as I possibly can to changing the way of life that I had. [...].The only thing I would want to change about my former life, is to fit more nice things into the way I live now.” (P3-IV). Patients explained that normality distracts them from the dominant feeling of being a patient. Being able to do the same things also gave them a feeling of control, satisfaction, meaning, and social embeddedness. Many patients mentioned adding more fun activities to their life as a consequence of prioritizing and the urge to escape from the situation. However, some informal caregivers mentioned that patients interpreted going on holiday with their children as a farewell because the reason for initiating this activity was their advanced cancer.

Many informal caregivers were aware that they would outlive the patient, and some informal caregivers felt the need to invest in a life after the patients’ death. Informal caregivers often explained how hard it was to combine their caregiving role with other responsibilities such as work and social activities: “At that time I made a conscious decision to continue playing golf; it is something that enables me to clear my head, and that is extremely important to me. But it is difficult, because you are away for four or five hours at a time which is often rather too long for [PATIENT] […]At the beginning you stop going for a while. But I realise that if I don’t go…, you really need to make some time for yourself. You can’t be joined at the hip 24/7.” (C7-IV).

Missing out

Patients’ diagnosis and treatments interfered with their social life by physical or psychological complaints and medical appointments, and they often missed out on social events and resigned or reduced their job. Patients also explained how society is rushing by, while they were struggling with the uncertainty regarding their limited life expectation. Some patients planned social events ahead regardless of their condition, while others put their social life on hold, as illustrated here: “And even if it is just a weekend away or something like that... but I do find it difficult, everything is difficult actually, we are now planning a few things... you do try some things, but I can’t promise anything because I don’t know where I will be up to after the end of March.” (P24-FG). Missing out on social events made patients feel socially excluded, as well as missing out on conversations about these events.

For informal caregivers, there were also major social consequences. Some resigned their job to spend as much time as possible with the patient, while others kept working as long as possible. Reasons for informal caregivers to continue working were financial pressure, satisfaction, and distraction. Many working informal caregivers mentioned that their career was on hold and that their professional functioning was negatively affected because their situation pushed them to their limits. Many found it difficult to continue work because they felt to be of more use at home. Others also mentioned that social relations were sometimes judgmental about continuing work.

The value of social activities

Many patients explained how daily activities in life gained value, the cancer diagnosis appeared to change the perspective on daily activities: “Do you know what you never do any more when you are as sick as I am? You don’t just pop out to the shops on your own, or have a rummage in the bargain basement of a department store and end up buying a lipstick that you don’t really need. I miss that.” (P7-IV). One patient called it the “noise” or “playfulness” of life.

Some informal caregivers emphasized the increased value of social activities. However, most informal caregivers spend less time on social activities for multiple reasons: lack of time and energy due to the experienced caregiving burden, difficult to leave the patient due to feelings of selfishness, shame, worries, or being judged by others. Some also explained that social activities did not result in positive energy as it used to do. They explained how their current life did not feel as their own, and social activities became associated with freedom and self-control. Most patients stimulated their caregivers to engage in social activities: “It is very important to me that she continues to live her own life as far as possible. We do a lot of things together, but you don’t have to do everything together. If she fancies going to town to buy a new dress or if she wants to have lunch with a friend, although actually she doesn’t really want to go out and leave me. But I push her to go, I’m fine staying at home.” (P21-IV).

Consequences for social identity

Cancer is central

Patients and informal caregivers often explained how cancer has become central to their social identity. Conversations with social relations were often focused on the illness and its treatments: “It got to the point where I was beginning to find it rather strange to be the focus of so much attention, I felt like a freak or something; all of a sudden everyone wanted to know all about how things were going.” (P39-FG). Some patients were also troubled when random people would ask them intimate questions about their health status.

Informal caregivers emphasized that many social relations feel uncomfortable to address the patient directly. Informal caregivers received many cancer-related questions from social relations that were tiresome. Some mentioned that social events were often a burden to them because of the confrontation with people asking questions about their situation. “I don’t want to be the main attraction. Of course people look at you, and they do look at you. Or ask you things [..].There is always a moment of hesitation, although not with the inner circle if you know what I mean. It is more with those people who aren’t quite so close. There comes a time when you don’t feel always feel comfortable with it, or strong enough. Or you really don’t want to discuss it. You perceive it differently. It is a very serious business, not some light-hearted social occasion.” (C32-IV). As a consequence, some informal caregivers mentioned that going on holiday would temporarily relieve them from their new social identity because they would be anonymous there.

Being confronted with assumptions regarding cancer patients

Many patients and informal caregivers emphasized that the patient’s appearance can be misleading because people often assume you feel good when you look good. Many patients and informal caregivers found it confronting when people complimented the appearance of the patient or spoke negatively about it. Some informal caregivers mentioned that patients were keeping up appearances, because patients did not want to feel like a burden to others. According to informal caregivers, this behavior of the patient misrepresented their situation and made informal caregivers feel misunderstood by social relations.

Many patients found it difficult that their social identity changed due to cancer. Some informal caregivers also said that they were treated differently by social relations since the cancer diagnosis. “I’ve noticed that most people, my really good friends, find it difficult to disagree with me. Do you know what I mean? They treat you with kid gloves. And I am the type who always says ‘Come on then! If you have a different opinion - come on, let’s talk about it! But nowadays they are very guarded, and not happy with me tackling things head on. It isn’t really helpful to me. So I invite them over and do it anyway.” (C32-IV). Many patients also mentioned feelings of isolation due to exclusion from conversations about events. “And people just don’t tell you things any more. Like accidently discovering that your brother has been to Italy. Then you ask them why they didn’t tell you, and they reply because you can’t go on holiday anymore and they thought it might upset you.” (P7-IV). Most informal caregivers mentioned that they helped their social relations to stop avoiding the patient and instruct them how to treat the patient and themselves. Some informal caregivers were very accepting towards socially awkward responses of their social relations, while others could not grasp the misconception of others.

Consequences for social network

The value of social relations

Most patients and informal caregivers spoke about an increased importance of social relationships. For patients, social connectedness has been giving meaning to their lives and brought support and enjoyment, but this was hindered by experienced social exclusion. “My friend has been to Spain recently and I told her how much I enjoy hearing her stories about it. And she said, I know you do but I find it difficult – us enjoying ourselves sitting in the sun enjoying a drink in Malaga. I feel so bad for you because you can’t. And I told how upsetting it is when people just don’t tell you things any more. I can’t go anywhere myself any more, but at least I can enjoy it through you.” (P7-IV).

Changes in the network

Most patients and informal caregivers mentioned that they had lost social relations and that their social network also unexpectedly had expanded simultaneously by new social contacts and re-establishing contacts. “They have eaten here, they have drunk here, they have got drunk here, they have partied – they did it all, and now it’s over. OK, if that’s the way you want it, that’s the way you’ll get it. Then again, I have been back in contact with my brother for the past two years, not every day though.” (P22-IV). Some informal caregivers said that they had less time to invest in relationships and to attend social events what has led to the loss of social relations. Both patients and informal caregivers also mentioned a decreased interest in superficial relations. Many patient and informal caregivers appreciated the increased transparency of their social network. They also mentioned an increased quality of certain relationships, supportive relations with healthcare professionals, and positive and negative changes in the relation between the patient and informal caregivers.

Perceived social support

Most patients experienced more support than they had anticipated. Patients and informal caregivers experienced mainly practical support, and emotional support was less available. “I used to be able to do everything, clean the whole house. Unfortunately those days are over. But two friends come every week to clean, they have set up a cleaning club especially for the purpose.” (P4-FG). Many patients experienced a decrease in support over time. Contrary, most informal caregivers experienced an increase in support over time. “More people are beginning to ask me how I am, my colleagues too. The first three or four months nobody bothers to ask. Because the person who is ill gets all the attention.” (C19-FG).

Visits from social relations were sometimes burdensome, while other times, they were helpful. This depended on how social relations approached the situation. “I had a friend with cancer, I used to go and see her often and she always used to say that I came in full of life and ideas about we could do that day... it wasn’t always immediately gloom and misery. She said, she didn’t need anyone reminding her about that. It was so much better for her if someone suggested going out to lunch, or going for a walk or invited her over to eat with the family that evening. For people like her, these are definitely the best reactions to the situation.” (C21-IV). Some patients appreciated peer support, while others found it confronting because it made them feel like a patient. Many informal caregivers informed social relations about the patient’s status and instructed them how to treat the patient. Most informal caregivers mentioned that their mediating role was important for maintaining the patient’s supportive social network. Most informal caregivers also provided support to their social relations regarding the situation.

Discussion

This qualitative study shows that social consequences are substantial for patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers. Major consequences have been found regarding social engagement, social identity, and social network. Several findings deserve particular attention. Firstly, patients and informal caregivers often mentioned their struggle to proceed with social life as prior to cancer, with an increased focus on fun activities. However, our study also reveals that patients and informal caregivers experience barriers in doing so. This coincides with Hasegawa et al.’s [26] findings that the top unmet need in advanced cancer patients was not being able to do the usual things. Patients in our study mentioned symptom burden and lack of time due to medical appointments as barriers. This coincides with previous research showing that the diagnosis of advanced colorectal cancer takes a big part of life, leaving little time for patients to continue normal life activities [27].

Secondly, informal caregivers experienced less joy from social activities, and both patients and informal caregivers felt socially excluded to some extent. Knox et al. showed that young adults with advanced cancer became socially isolated because they felt misunderstood and alienated from the rest of the world [8]. In our study, patients, but especially caregivers, often provided instructions to social relations to reduce feelings of social isolation.

Thirdly, both patients and informal caregivers emphasized that the illness had become central in their social life. The social identification process appeared to be influenced by the strive for normality and social isolation. Many patients and informal caregivers resisted self-identification with cancer because they do not want to be treated differently by others and strive for normality. When patients and informal caregivers failed to reach normality, it appeared to be more likely that they are viewed and treated as cancer patients by their social network. Consequently, this further enhanced the self-identification with cancer. Harwood and Sparks [28] suggested that cancer identification also may have positive effects, such as the cognitive representation of a cancer patient as a strong and positive person [28]. However, such positive associations were not found in our study.

Fourth, patients and informal caregivers experienced structural changes in their social network. Mosher et al. [29] also described similar social network changes among patients with advanced colorectal cancer and their informal caregiver, including closer relationships, greater appreciation for life, and clarified priorities. In our study, the perceived support was greater than anticipated. However, patients also reported a decrease in experienced support over time, while informal caregivers experienced the opposite. It is known that the absence of a supportive context has negative health consequences for patients [30] and informal caregivers [31] and that social support also has beneficial effects in patients with advanced cancer [32, 33] and informal caregivers [34]. However, it is important to differentiate between types of social support as in our study patients, and informal caregivers reported sufficient practical support but a lack of emotional support.

Lastly, our study shows that many social consequences were partly equivalent to experiences of other cancer patients or cancer survivors [6, 8–10]. Some similarities in social consequences are changes in social relations, problems with social support, and feelings of social isolation. However, some social consequences appear to be specific for advanced cancer; patients in our study worried greatly about leaving behind their loved ones. This affected them more than worries regarding their illness or impending death. Patients were worried about the emotional impact of their death and about the financial consequences for their loved ones. Many patients were also worried about being a burden to others. Previous research found that the perception of being a burden to others can have negative health effects [35]. Social consequences specific for informal caregivers of advanced cancer patients were the struggle to combine the caregiving role with normal life activities due to an increased responsibility regarding their own and, sometimes, their children’s future after the patient’s death. They also feel less supported, because the patient already checked-out of life which made them feel less supported.

A strength of this study is that both advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers were included. Nevertheless, our study has some limitations. First, selection bias is present because most participants were highly educated and no non-western patients participated in the study. It is known that there are barriers in including minorities in studies [36, 37]. Due to this selection bias, cultural and educational differences regarding beliefs about cancer may be absent, while it is known that these differences exist [38–40]. Second, the focus groups were smaller than anticipated (two to six participants per focus group), mainly due to death or decreasing health. Guidelines advise at least six participants in a focus group, because it may be difficult to get the group conversation going [41]. However, considering our vulnerable study population, our participants felt more comfortable to discuss private topics in a smaller group with plenty opportunity to contribute to the conversation. Furthermore, this number of participants appeared to have provided sufficient variation in experiences.

Practical implications

It is ironic that cancer is able to undermine the powerful resource of social relationships to cope with the illness, which may actually cause additional distress [42]. Empowering patients and their informal caregivers to discuss their feelings regarding social consequences may be beneficial. Suggestions to empower patients and their informal caregivers are via psychological support and by increasing societal awareness, via national campaigns or websites. Also, creating awareness among healthcare professionals regarding the social impact of advanced cancer is essential as they are able to address the topic, anticipate on social problems, and provide social support. Also, informing social relations regarding the impact of advanced cancer and effective support methods may empower social support systems and reduce feelings of isolation. Furthermore, a quantitative study should map the extent of social consequences among these patients and their informal caregivers.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that advanced cancer has substantial impact on social engagement, social identity, and social networks. Many patients and their informal caregivers engage less in social activities, their social identity shifts towards the disease, and they perceive many changes in their social network. Feelings of social exclusion appear to be inevitable.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 36 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Dr. Leon Oerlemans, Tilburg School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Tilburg University, for his comments that greatly improved our work.

Author contributions

NR and JvR participated in the design of the study. JvR, NR, LB, and MY were involved in the data collection, analysis, and interpretation. JvR drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in the critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This focus group study is part of a larger study on quality of life and quality of care as experienced by patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers (NTR6584): The eQuiPe study. This work was supported by the Roparun Foundation, the Netherlands.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical considerations

The study is conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol has been reviewed by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Dutch Cancer Institute (NKI) in Amsterdam, the Netherlands (METC16.2050). The METC has exempted this observational research from ethical review, accordingly to the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). Informed consent was obtained from all the participating patients and their informal caregivers. Furthermore, in data collection and analyses procedures, the rules of Dutch Personal Data Protection Act were followed.

References

- 1.Kamal AH, Gradison M, Maguire JM, Taylor D, Abernethy AP. Quality measures for palliative care in patients with cancer: a systematic review. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(4):281–287. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev. 1943;50(4):370–396. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(3):497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss. Volume 1, Attachment. London: Hogarth Press New York: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catt S, Starkings R, Shilling V, Fallowfield L. Patient-reported outcome measures of the impact of cancer on patients’ everyday lives: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(2):211–232. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0580-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warner EL, Kent EE, Trevino KM, Parsons HM, Zebrack BJ, Kirchhoff AC. Social well-being among adolescents and young adults with cancer: a systematic review. Cancer. 2016;122(7):1029–1037. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright P, Smith A, Booth L, Winterbottom A, Kiely M, Velikova G, Selby P. Psychosocial difficulties, deprivation, and cancer: three questionnaire studies involving 609 cancer patients. Brit J Cancer. 2005;93(6):622–626. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knox MK, Hales S, Nissim R, Jung J, Lo C, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. Lost and stranded: the experience of younger adults with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(2):399–407. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sodergren SC, Husson O, Robinson J, et al. Systematic review of the health-related quality of life issues facing adolescents and young adults with cancer. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(7):1659–1672. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1520-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malone M, Harris AL, Luscombe DK. Assessment of the impact of cancer on work, recreation, home management and sleep using a general health status measure. J R Soc Med. 1994;87(7):386–389. doi: 10.1177/014107689408700705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackenzie CR. ‘It is hard for mums to put themselves first’: how mothers diagnosed with breast cancer manage the sociological boundaries between paid work, family and caring for the self. Soc Sci Med. 2014;117:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright EP, Kiely MA, Lynch P, Cull A, Selby PJ. Social problems in oncology. Br J Cancer. 2002;87(10):1099–1104. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim Y, Schulz R. Family caregivers’ strains: comparative analysis of cancer caregiving with dementia, diabetes, and frail elderly caregiving. J Aging Health. 2008;20(5):483–503. doi: 10.1177/0898264308317533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balfe M, Keohane K, O'Brien K et al (2016) Social networks, social support and social negativity: a qualitative study of head and neck cancer caregivers’ experiences. Eur J Cancer Care 26(6) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Ewing G, Ngwenya N, Benson J, Gilligan D, Bailey S, Seymour J, Farquhar M. Sharing news of a lung cancer diagnosis with adult family members and friends: a qualitative study to inform a supportive intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(3):378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wittenberg E, Borneman T, Koczywas M, et al. Cancer communication and family caregiver quality of life. Behav Sci. 2017;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.3390/bs7010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litzelman K, Kent EE, Rowland JH. Social factors in informal cancer caregivers: the interrelationships among social stressors, relationship quality, and family functioning in the CanCORS data set. Cancer. 2016;122(2):278–286. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosher CE, Bakas T, Champion VL. Physical health, mental health, and life changes among family caregivers of patients with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(1):53–61. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.53-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Longo CJ, Fitch M, Deber RB, Williams AP. Financial and family burden associated with cancer treatment in Ontario, Canada. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(11):1077–1085. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girgis A, Lambert S, Johnson C, Waller A, Currow D. Physical, psychosocial, relationship, and economic burden of caring for people with cancer: a review. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(4):197–202. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Q, Loke AY. The positive aspects of caregiving for cancer patients: a critical review of the literature and directions for future research. Psychooncology. 2013;22(11):2399–2407. doi: 10.1002/pon.3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shilling VM, Starkings R, Jenkins VA, Fallowfield L. Uncertainty about the future for patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers: a qualitative view. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(5):218. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0628-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rennie DL. Qualitative research as methodical hermeneutics. Psychol Methods. 2012;17(3):385–398. doi: 10.1037/a0029250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasegawa T, Goto N, Matsumoto N, Sasaki Y, Ishiguro T, Kuzuya N, Sugiyama Y. Prevalence of unmet needs and correlated factors in advanced-stage cancer patients receiving rehabilitation. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(11):4761–4767. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3327-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sjövall K, Gunnars B, Olsson H, Thomé B. Experiences of living with advanced colorectal cancer from two perspectives: inside and outside. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(5):390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harwood J, Sparks L. Social identity and health: an intergroup communication approach to cancer. Health Commun. 2003;15(2):145–159. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1502_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosher CE, Adams RN, Helft PR, O’Neil BH, Shahda S, Rattray NA, Champion VL. Positive changes among patients with advanced colorectal cancer and their family caregivers: a qualitative analysis. Psychol Health. 2017;32(1):94–109. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2016.1247839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akechi T, Okuyama T, Sugawara Y, Nakano T, Shima Y, Uchitomi Y. Major depression, adjustment disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder in terminally ill cancer patients: associated and predictive factors. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(10):1957–1965. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1052–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colloca G, Colloca P. The effects of social support on health-related quality of life of patients with metastatic prostate cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31(2):244–252. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0884-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dobrikova P, Pcolkova D, AlTurabi LK, et al. The effect of social support and meaning of life on the quality-of-life care for terminally ill patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32(7):767–771. doi: 10.1177/1049909114546208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldstein NE, Concato J, Fried TR, Kasl SV, Johnson-Hurzeler R, Bradley EH. Factors associated with caregiver burden among caregivers of terminally ill patients with cancer. J Palliat Care. 2004;20(1):38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang ST, Chang WC, Chen JS, Su PJ, Hsieh CH, Chou WC. Trajectory and predictors of quality of life during the dying process: roles of perceived sense of burden to others and posttraumatic growth. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(11):2957–2964. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2288-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hudson SV, Momperousse D, Leventhal H. Physician perspectives on cancer clinical trials and barriers to minority recruitment. Cancer Control. 2005;12(2):93–96. doi: 10.1177/1073274805012004S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, Gary TL, Bolen S, Gibbons MC, Tilburt J, Baffi C, Tanpitukpongse TP, Wilson RF, Powe NR, Bass EB. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112(2):228–242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel-Kerai G, Harcourt D, Rumsey N, Naqvi H, White P. The psychosocial experiences of breast cancer amongst Black, South Asian and White survivors: do differences exist between ethnic groups? Psycho-Oncology. 2017;26(4):515–522. doi: 10.1002/pon.4187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vrinten C, Wardle J, Marlow LA. Cancer fear and fatalism among ethnic minority women in the United Kingdom. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(5):597–604. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcu A, Black G, Vedsted P, Lyratzopoulos G, Whitaker KL. Educational differences in responses to breast cancer symptoms: a qualitative comparative study. Br J Health Psychol. 2017;22(1):26–41. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raats I. Handleiding Focusgroepen. PGO Support. Raats voor mensgerichte zorg, 2017. Available at: https://www.participatiekompas.nl/sites/default/files/Handleiding%20Focusgroepen%202017%20nov.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2018

- 42.Wortman CB. Social support and the cancer patient. Conceptual and methodologic issues. Cancer. 1984;53(10):2339–2362. doi: 10.1002/cncr.1984.53.s10.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 36 kb)