Abstract

Sir4 is a core component of heterochromatin found in yeasts of the Saccharomycetaceae family, whose general hallmark is to harbor a three-loci mating-type system with two silent loci. However, a large part of the Sir4 amino acid sequences has remained unexplored, belonging to the dark proteome. Here, we analyzed the phylogenetic profile of yet undescribed foldable regions present in Sir4 as well as in Esc1, an Sir4-interacting perinuclear anchoring protein. Within Sir4, we identified a new conserved motif (TOC) adjacent to the N-terminal KU-binding motif. We also found that the Esc1-interacting region of Sir4 is a Dbf4-related H-BRCT domain, only present in species possessing the HO endonuclease and in Kluveryomyces lactis. In addition, we found new motifs within Esc1 including a motif (Esc1-F) that is unique to species where Sir4 possesses an H-BRCT domain. Mutagenesis of conserved amino acids of the Sir4 H-BRCT domain, known to play a critical role in the Dbf4 function, shows that the function of this domain is separable from the essential role of Sir4 in transcriptional silencing and the protection from HO-induced cutting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In the more distant methylotrophic clade of yeasts, which often harbor a two-loci mating-type system with one silent locus, we also found a yet undescribed H-BRCT domain in a distinct protein, the ISWI2 chromatin-remodeling factor subunit Itc1. This study provides new insights on yeast heterochromatin evolution and emphasizes the interest of using sensitive methods of sequence analysis for identifying hitherto ignored functional regions within the dark proteome.

Keywords: H-BRCT, Sir4, Itc1, Esc1, Asf2, Dbf4, mating-type switching, hydrophobic cluster analysis

Introduction

Heterochromatin is a feature of eukaryotic chromosomes with conserved roles in gene expression, genome spatial organization, and chromosome stability. In most eukaryotes, heterochromatic domains are decorated by histones H3 methylated on lysine 9 and bound by the heterochromatin protein HP1 (Larson et al. 2017; Strom et al. 2017; Allshire and Madhani 2018; Machida et al. 2018). These domains are usually large and can comprise up to half of the genome. Among eukaryotes, some yeast species do not share these two hallmarks. In the most studied budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, heterochromatin (also called silent chromatin) is restricted to a small fraction of the genome (<1%). It lacks the histone H3 lysine 9 methylation and HP1. Instead, its core components are H4 lysine 16 deacetylated nucleosomes bridged by the histone-binding factor Sir3 in stoichiometric complex with the protein Sir4 and the histone deacetylase Sir2 (Behrouzi et al. 2016; Gartenberg and Smith 2016). Despite these differences, other general properties of heterochromatin are conserved such as cis and trans cooperativity in the establishment of a repressive compartment for transcription, clustering at the nuclear periphery and near the nucleolus, epigenetic variegation, and late replication (Meister and Taddei 2013; Tatarakis et al. 2017).

The main function of heterochromatin in S.cerevisiae relates to mating, the ability of two haploid cells of opposite mating type (a and α) to form a diploid zygote. The MAT locus specifies the haploid cell mating type. To favor mating, a programmed DNA rearrangement allows a reversible switch from one mating type to the other (Hicks and Herskowitz 1976; Strathern et al. 1982; Haber 2012; Hanson and Wolfe 2017). In this process, DNA at the MAT locus is cleaved by the endonuclease HO, removed and replaced with DNA from either the HML or HMR locus. HML and HMR are ∼3-kb-long silent cassettes that store the sequence information specific of each mating type. Sir2/Sir3/Sir4-dependent heterochromatin prevents HML and HMR transcription and protects them from cleavage by HO during mating-type switching.

Heterochromatin in S.cerevisiae also covers a few kilobases at each telomere (Gartenberg and Smith 2016; Hocher et al. 2018). This subtelomeric heterochromatin has several functions. It clusters telomeres at the nuclear periphery and generates a local environment favoring heterochromatin at HML and HMR because both loci are not far from a telomere (∼15 and ∼25 kb, respectively). It also acts as a molecular sink ensuring that Sir proteins do not bind promiscuously at other sites in the genome (Buck and Shore 1995; Maillet et al. 1996; Marcand et al. 1996; Ruault et al. 2011; Meister and Taddei 2013; Guidi et al. 2015). Finally, subtelomeric heterochromatin contributes to genome stability. It prevents loss-of-heterozygosity by break-induced recombination at subtelomeres (Batté et al. 2017). It also inhibits telomere fusions by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) (Marcand et al. 2008) and favors telomere elongation through telomerase recruitment (Chen et al. 2018), two functions relying more specifically on Sir4, not Sir3 and Sir2.

As Sir4 binds each of the other Sir proteins, it is generally considered as a scaffold for the Sir complex assembly. Two structural domains have been recognized to date in Sir4, which are directly implicated in the Sir complex assembly. First, the extreme C-terminal end (amino acid [aa] 1271–1346) folds into a helical coiled-coil, allowing the protein to dimerize (Chang et al. 2003; Murphy et al. 2003) and to interact with Sir3 (Moretti et al. 1994; Moazed et al. 1997; Park et al. 1998). Second, a central domain, called the Sir2 interaction domain (SID, aa 737–893), makes contact with Sir2 (Moazed et al. 1997; Cockell et al. 2000; Ghidelli et al. 2001; Hoppe et al. 2002; Hsu et al. 2013), stimulating its deacetylase activity (Tanny et al. 2004; Cubizolles et al. 2006; Hsu et al. 2013).

In addition, both the N- and C-terminal regions of Sir4 target the Sir complex to chromatin, through association with other proteins, among which the DNA-binding factor Rap1 (Moretti et al. 1994; Luo et al. 2002) and the two subunits of the KU end-binding factor (Tsukamoto et al. 1997; Laroche et al. 1998; Martin et al. 1999; Mishra and Shore 1999; Luo et al. 2002; Roy et al. 2004; Taddei et al. 2004; Ribes-Zamora et al. 2007; Hass and Zappulla 2015; Chen et al. 2018). KU binding to Sir4 contributes to telomerase recruitment and the subsequent lengthening of telomeres (Chen et al. 2018; Hass and Zappulla 2015). Sir4 also participates in the anchoring of yeast telomeres at the nuclear periphery through its “partitioning and anchoring domain” (PAD, aa 960–1150), which interacts with the peripheral membrane anchor Esc1 (Ansari and Gartenberg 1997; Andrulis et al. 2002; Taddei et al. 2004). The same Sir4 PAD additionally interacts with the integrase of the Ty5 yeast retrotransposon, an interaction essential for the preferential integration of Ty5 in heterochromatin (Zhu et al. 2003; Kvaratskhelia et al. 2014). No structural information is, however, available for the Sir4 PAD and Esc1.

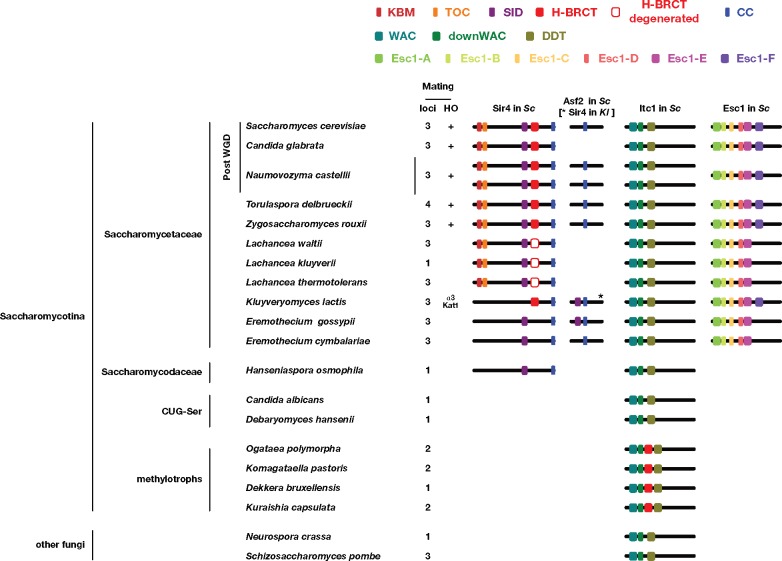

On an evolutionary point of view, Sir4 is the least conserved protein among the Sir proteins. It seemed to coappear in evolution with the two silent mating-type cassettes, that is, the three MAT-like-loci system found in the Saccharomycetaceae family of yeasts (including Candida glabrata, Naumovozyma castellii, Zygosaccharomyces rouxii, Kluyveryomyces lactis, and Lachancea waltii) (Génolevures Consortium 2009; Dujon 2010; Gordon et al. 2011; Wolfe and Butler 2017) (fig. 1). Within the larger subphylum Saccharomycotina, yeast species from the CUG-Ser clade (including Candida albicans and Debaryomyces hansenii) have only one MAT locus, no silent cassette, and apparently lack Sir4 (Bennett and Johnson 2005). The more distant yeasts of the methylotrophs clade often display a two MAT-like-loci system with only one silent cassette adjacent to a telomere or a centromere but also lack Sir4 (De Schutter et al. 2009; Kuberl et al. 2011; Curtin et al. 2012; Piskur et al. 2012; Morales et al. 2013; Ravin et al. 2013; Hanson et al. 2014, 2017; Maekawa and Kaneko 2014; Coughlan et al. 2016; Hanson and Wolfe 2017). How silencing is achieved in these yeasts is unknown.

Fig. 1.

—Schematic view of the structural and functional domains identified in Sir4, Asf2, Itc1, and Esc1 in yeast species. Number of mating loci from Gordon et al. (2011) and Wolfe and Butler (2017). The empty red square represents the degenerated H-BRCT domains present in species from the Lachancea clade.

A large part of the Sir4 protein sequence, including regions which are known to interact with partners, remains in the dark, that is, lacks annotations relative to known domain databases. In fact, such orphan sequences represent a significant portion of the whole proteomes (Faure and Callebaut 2013a; Bitard-Feildel and Callebaut 2017). A large part of this dark proteome corresponds to foldable regions, which once delineated, can be in some cases linked to already known families of domains, or are at the basis of the definition of novel families of domains (Faure and Callebaut 2013a; Bitard-Feildel and Callebaut 2017). These “hidden” relationships can be identified especially using fold signatures, which are more conserved than the sequences (Faure and Callebaut 2013b).

Using computational methods we previously developed (Faure and Callebaut 2013a, 2013b), we identified new domains or motifs in Sir4 and its partner Esc1. Particularly, we identified significant similarities of the Sir4 PAD with the conserved H-BRCT domain of Dbf4, the regulatory subunit of the Dbf4-dependent kinase (DDK or Cdc7) that is essential to replication initiation in eukaryotes. Dbf4 H-BRCT interacts in S. cerevisiae with an FHA domain of the Rad53CHK2 checkpoint kinase and constitutes a particular subfamily of BRCT (BRCA1 C-terminus) domains (Gabrielse et al. 2006; Matthews et al. 2012, 2014; Chen et al. 2013). The H-BRCT domain, hitherto uniquely found in Dbf4, has additional elements at the N- or C-terminus of a conserved BRCT core (Koonin et al. 1996; Callebaut and Mornon 1997; Leung and Glover 2011), which are critical to its specific function. We also identified H-BRCT domains within Itc1, a component of the conserved chromatin remodeling complex ISWI2 in Sir4-free species belonging to the methylotrophs clade. This study thus opens new perspectives on yeast heterochromatin evolution and for characterizing the role of H-BRCT domains, whose presence goes beyond the single Dbf4 protein.

Materials and Methods

Sequence Analysis

Hydrophobic cluster analysis (HCA) is well adapted to predict foldable domains (i.e., regions with a high density in hydrophobic clusters, mainly corresponding to the regular secondary structures) (Faure and Callebaut 2013a; Bitard-Feildel and Callebaut 2017) and to highlight within these foldable domains’ structural invariants, which are much more conserved than amino acid sequences (Faure and Callebaut 2013b; Bitard-Feildel et al. 2015). It is thus useful for deciphering information within “orphan” sequences, including well-folded domains for which it is possible to identify remote relationships (as for the H-BRCT domain highlighted here), as well as intrinsically disordered regions undergoing disorder-to-order transitions (as for the KU-binding motif [KBM] and TOC motif also described here) (Bitard-Feildel et al. 2018). Additional disorder predictions were made using IUPred (Dosztányi et al. 2005a, 2005b), completed by predictions of disorder-to-order transitions through the ANCHOR program (Dosztányi et al. 2009; Mészáros et al. 2009).

Sequence similarity searches were performed using PSI-BLAST (Altschul et al. 1997) and HHblits (Remmert et al. 2011), combined with HCA (Gaboriaud et al. 1987; Callebaut et al. 1997). Searches for sequence similarities with known 3D structures were made using HHpred (Meier and Söding 2015) and Phyre (Bennett-Lovsey et al. 2008).

The Yeast Gene Order Browser (http://ygob.ucd.ie/; last accessed February 2018) (Byrne and Wolfe 2005) was also used to visualize the syntenic context of the different genes.

Manipulation of 3D structures were performed using Chimera (Pettersen et al. 2004), whereas sequence alignment rendering was made using ESPript (Gouet et al. 1999).

Results

Analysis of the Whole Sir4 Sequence

Using HCA and SEG-HCA (Faure and Callebaut 2013a) (see Materials and Methods for the principles of the method) and starting from the only information of the single amino acid sequence of S. cerevisiae Sir4, we identified several regions predicted to consist of foldable domains (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). Up to aa 720, hydrophobic clusters are scarce within globally charged regions, suggesting that this amino-terminal half of S. cerevisiae Sir4 should be globally disordered. Such a prediction is supported by disorder predictors, such as IUPred (Dosztányi et al. 2005a, 2005b) (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). However, several regions in this amino-terminal half part have a higher density in hydrophobic clusters (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online), the lengths of which match those of regular secondary structures. Although these regions should not form on their own stable 3D structures, they may adopt such structures after energetic stabilization (typically upon binding with a partner) (Faure and Callebaut 2013a; Bitard-Feildel et al. 2018). This hypothesis is supported by ANCHOR results, which predicted disorder-to-order transitions in the same regions (Dosztányi et al. 2009; Mészáros et al. 2009) (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). From aa 720 onward, the Sir4 sequence contains two regions that are predicted as globular, which can be further subdivided using SEG-HCA into seven foldable domains. The two first ones (aa 737–910) correspond to the SID, with the hinge separating the two regions (aa 786–802) matching the disordered segment of the domain (see below). The following ones (third to seventh) extend from aa 970 onward. The two last regions correspond to the coiled-coil domain. The other (third to fifth) regions are yet undescribed.

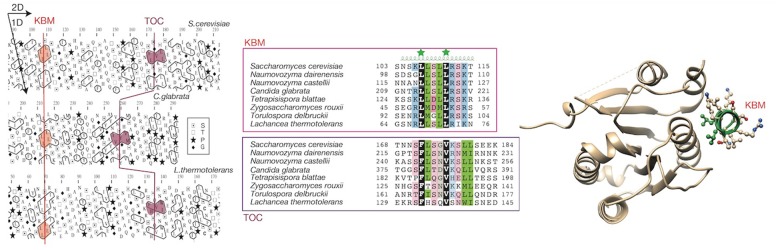

Conserved Sequences within the N-terminal Region

The few hydrophobic clusters of the N-terminal region have binary patterns (where 1 stands for any strong hydrophobic amino acid [V, I, L, M, F, Y, W] and 0 for other ones) typical of α-helices and β-strands, as deduced from our dictionary of hydrophobic clusters (Eudes et al. [2007]; supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). Most of them have limited lengths, except from nine clusters including four or more strong hydrophobic amino acids. Two of these last clusters (between aa 107 and 111 [binary code 11011] and aa 172 and 180 [binary code 110010011]), typical of α-helices, are detectable in Sir4 sequences from some species of the Saccharomycetaceae family, being, however, separated by sequences of variable length and embedded in predicted disordered regions (figs. 1 and 2). The first cluster is a KBM, which was recently observed in an α-helical structure in complex with KU (Chen et al. 2018) [PDB 5Y59]. The second cluster is a yet undescribed functional motif, which we called TOC for “second of TwO Clusters.” Of note is that these similarities could not be identified using standard search programs such as PSI-BLAST, due to the low sequence identities and the nonglobular character of the sequences. Instead, they were found by inspection of the conservation of HCA binary patterns. Although not detected here, we cannot exclude that KBM and TOC motifs are present, with degenerated sequences, in some members of the Saccharomycetaceae family, such as K.lactis and Eremothecium cymbalariae. No obvious sequence conservation was observed around the other hydrophobic clusters of the N-terminal half of Sir4.

Fig. 2.

—The KBM–TOC region. Alignment of two conserved sequences defining the KBM and TOC motif. At left are shown the alignment of the 2D HCA plots of Sir4 from three species, as well as the corresponding 1D sequence alignments, extended to several other species. At right is shown the 3D structure of the recently solved KBM–KU complex (PDB 5Y59), with the two highly conserved leucine from KBM highlighted in green. On the HCA plots, the sequence is shown on a duplicated alpha helical net, on which the strong hydrophobic amino acids (V, I, L, M, F, Y, W) are contoured. These form clusters, which have been shown to mainly correspond to regular secondary structures (Gaboriaud et al. 1987; Callebaut et al. 1997). The way to read the sequence and the secondary structures are indicated with arrows. Special symbols are reported in the inset. In the alignment, positions conserved over the family are colored in green for hydrophobic amino acids (V, I, L, F, M, Y, W), in blue and pink for basic and acidic ones, in gray for loop forming residues (P, G, D, N, S). The UniProt identifiers of the sequences are reported in supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online. No significant trace of KBM, moreover accompanied by a downstream TOC motif, could be found in the Kluyveromyces lactis and Eremothecium Sir4 sequences (both motifs presented in figure 3 of Chen et al. [2018] actually correspond to Asf2 sequences).

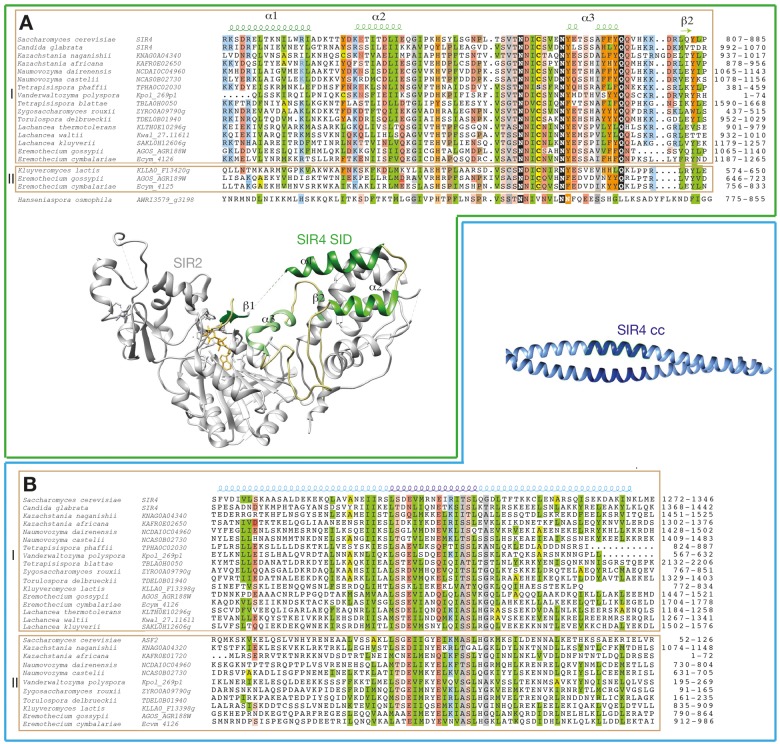

The SID and Relationship between Sir4 and Asf2

The second half of the Sir4 protein sequences contains seven regions that are predicted as foldable (see before, supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). The two first ones correspond to the SID, whose 3D structure has been solved in complex with Sir2 (Hsu et al. 2013) [PDB 4AIO]. In isolation, the Sir4 SID does not appear to have a stable structure but folds in contact with Sir2 through multiple sites (fig. 3A). One of these sites, accommodating Sir4 strand β1, corresponds to the first foldable segment, whereas the second foldable segment includes helices α1 to α3 and strand β2. The two segments are separated by a disordered sequence. SID is well conserved in the Sir4 proteins of the whole Saccharomycetaceae family (fig. 3A, top panel). Using PSI-BLAST with the S. cerevisiae SID sequence as query, we also found this domain in a hypothetical protein (g3198) from Hanseniaspora osmophila (UniProt A0A1E5R7W4), a member of the Saccharomycodaceae family, which is placed just nearby the Saccharomycetaceae family, according to recent phylogeny trees (Riley et al. 2016; Shen et al. 2016) (fig. 3A). This sequence shares the characteristics of the Sir4 family, with a significant proportion of disordered sequences which may undergo disorder-to-order transitions, and a C-terminal coiled-coil. Using this sequence (either the SID or the whole sequence) for further similarity searches did not lead to reveal any potential Sir4 sequences in more distant yeast species.

Fig. 3.

—The SID and coiled-coil (CC) of S. cerevisiae Sir4 and Asf2 and related proteins in the Saccharomycetaceae clade. These domains are analyzed within the two groups (I and II) of proteins (designated with the corresponding species and gene names), including S. cerevisiae Sir4 and Asf2 and defined according to the YGOB synteny and to the similarity relationships identified here. (A) Multiple alignment of the SID (except from the most variable N-terminal region, including strand β1). (B) Multiple alignment of the CC region. In the alignments, positions conserved over the family are colored in green for hydrophobic amino acids (V, I, L, F, M, Y, W), light green for amino acids that can substitute for hydrophobic amino acids in a context-dependent way (A, T, S, C), orange for aromatic amino acids (F, Y, W), gray for small amino acids (G, V, A, S, T), brown for P, yellow for the conserved C, blue for basic (K, R, H) amino acids, and pink for acidic (D, E) amino acids. Domain limits are reported at the end of the sequences, and the UniProt identifiers of the sequences are reported in supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online. Between the alignments are reported the ribbon representations of the SID-Sir2 3D structure complex (PDB 4AIO) and of the Sir4 CC (PDB 1PL5). The corresponding regular secondary structures are reported up the alignments.

Of note in the Saccharomycetaceae family is that SID is found in two protein sequences of Eremotheciumgossypii (AGR188Wp and AGR189Wp), whose genes are contiguous (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online). Looking at corresponding contiguous genes also present in pre-whole genome duplication (WGD) (K. lactis, Z. rouxii, and Torulospora delbruckii) and post-WGD species (N. castelli, N. dairensis, K. naganishii, and Vanderwaltozyma polyspora) (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online), one can observe that all proteins syntenic to AGR188Wp (group I) except one possess an SID (green boxes) and a C-terminal coiled-coil (blue boxes), displaying the same architecture than the S. cerevisiae Sir4. In these species, a newly discovered H-BRCT domain (orange boxes, see below) is also present between the SID and coiled-coil region. The only exception is for K. lactis F13398p (syntenic to E. gossypii AGR188Wp), which lacks SID but maintains the H-BRCT domain and coiled-coil in similar positions to that observed in other species. In contrast, none of the products of the genes syntenic to E. gossypii AGR189Wp (group II) except one (K. lactis F13420p) possesses as AGR189Wp an SID. A conserved motif (blue boxes) was detected in this group II between these proteins and S. cerevisiae Asf2, which moreover share similarities with the Sir4 C-terminal coiled-coil (figs. 1 and 3B, supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online). These observations of shared domains (SID, limited to two species, and coiled-coil) thus further support a common origin for Sir4 and Asf2 at the emergence of the Saccharomycetaceae family, likely stemming from a tandem gene duplication (Byrne and Wolfe 2005; Hickman et al. 2011; Gartenberg and Smith 2016). Asf2 is missing in some species (from the Lachancea clade and in C.glabrata). Asf2 from S. cerevisiae interacts with Sir3 and has an undefined role in silencing regulation (Le et al. 1997; Buchberger et al. 2008). We show here that, contrary to Sir4, Asf2 from S. cerevisiae is not required for telomere protection against fusions by NHEJ (supplementary fig. S3, Supplementary Material online). Interestingly, F13420p from K. lactis, which is syntenic to E. gossypii AGR189Wp and possesses an SID, was previously described as the Sir4 protein in K. lactis, because it complements the mating defect of a S. cerevisiae sir4Δ mutant and that its deletion in K. lactis derepresses the cryptic HML-α1 gene (Aström and Rine 1998; Hickman and Rusche 2009). This suggests a separation of functions in K. lactis, with the protein bearing the SID holding the Sir2-dependent transcriptional repression activity and the other holding other functions that remain to be explored.

A New H-BRCT Domain in the C-terminal Domain of Sir4

The second region, separated from SID by a large hinge (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online), includes at its C-terminal extremity the coiled-coil dimerization domain, whose structure has also been solved (Chang et al. 2003; Murphy et al. 2003) [PDB 1PL5 and 1NYH].

Searching the NCBI nr database using the sequence of the region encompassing aa 970–1197 (region preceding the extended coiled-coil region) as query using PSI-BLAST revealed significant similarities on its first part, encompassing a hundred amino acids (aa 970–1087). These are observed with Sir4 protein sequences of all the species of the Saccharomycetaceae family, up to K.lactis (fig. 4, upper panel), with the exception of Sir4 proteins from the Eremothecium and Lachancea clades (L. kluyverii, L. thermotolerans). From the second PSI-BLAST iteration onward, significant similarities then appeared between this Sir4 conserved domain and the H-BRCT domain of yeast Dbf4, whose experimental 3D structure has been solved (Matthews et al. 2012) [PDB 3QBZ] (fig. 4, middle panel).

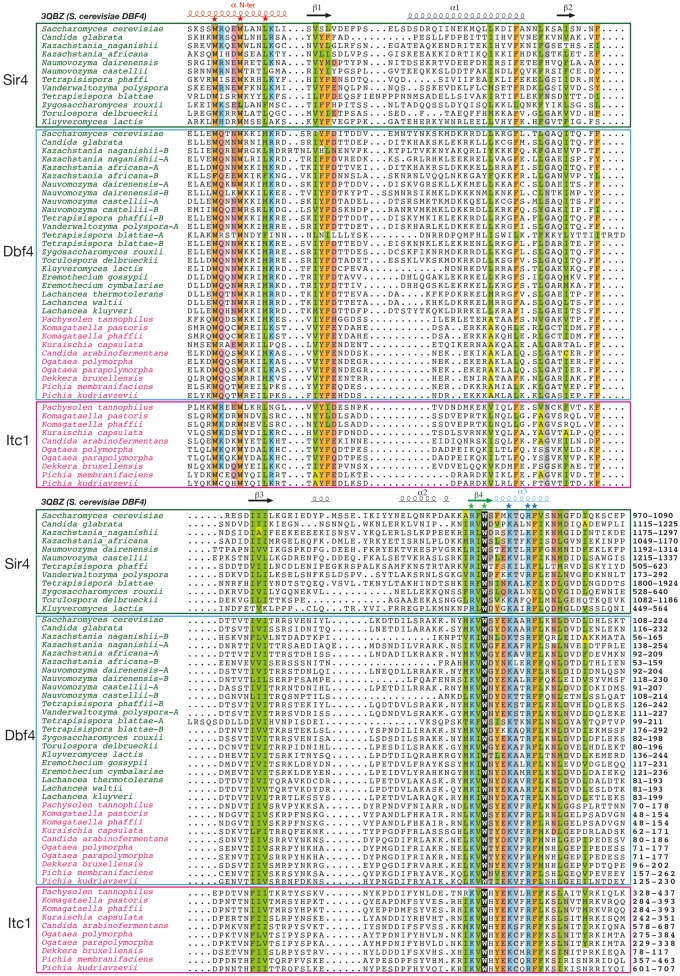

Fig. 4.

—The H-BRCT domains of S. cerevisiae Sir4 and related proteins of the Saccharomycetaceae clade and of Itc1 from the methylotrophs clade compared with those of Dbf4. Multiple alignment of the H-BRCT domain sequences. Sequences related to S. cerevisiae Sir4 belong to the group I sequences, as described in supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online. Regular secondary structures based on the experimental 3D structure of the S. cerevisiae Dbf4 H-BRCT domain (PDB 3QBZ; Matthews et al. 2012) are reported above the alignment. Positions conserved over the entire H-BRCT family are colored in green for hydrophobic amino acids (V, I, L, F, M, Y, W), light green for amino acids that can substitute for hydrophobic amino acids in a context-dependent way (A, T, S), orange for aromatic amino acids (F, Y, W), yellow for loop-forming amino acids (P, G, D, N, S) and related amino acids (E, T), blue for basic (K, R, H) amino acids, and pink for acidic (D, E) amino acids. Highly conserved amino acids reported on the representation of the 3D structure of yeast Dbf4 H-BRCT domain (fig. 5) are depicted with stars. Domain limits are reported at the end of the sequences, and the UniProt identifiers of the sequences are reported in supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online.

Examination of the HCA plots of the Sir4 sequences from the Lachancea clade suggests that the H-BRCT region is likely present in these proteins, as supported by some conserved clusters and some sequence motifs, but should be degenerated relatively to well-conserved amino acids (supplementary figs. S4A and S5, Supplementary Material online). In particular, two highly conserved tryptophan residues at the beginning of the H-BRCT domain are not present in the Lachancea sequences. Such hypothesis is also supported by similarities reported, however, with nonsignificant E-values in the PSI-BLAST results. In contrast, no trace of an H-BRCT domain could be found in the Eremothecium Sir4 sequences, although some hydrophobic clusters are still present between the SID and the coiled-coil region (supplementary fig. S4A, Supplementary Material online). No H-BRCT trace could be highlighted in the Hanseniaspora Sir4-like protein. The Sir4 sequences downstream the H-BRCT domains (i.e., between the H-BRCT domain and the coiled-coil region) show no obvious similarities with any other protein sequences.

An H-BRCT Domain Is Also Found in Itc1 Proteins from the Methyltrophs Clade

An H-BRCT domain is also retrieved in all the Itc1 proteins from the methylotrophs clade (fig. 4, bottom panel and supplementary fig. S4B, Supplementary Material online), between a conserved, yet unknown domain (that we named downWAC) downstream of a WAC domain (after WSTF/Acf1/cbp146 [Ito et al. 1999]) and a DDT domain (after the better-characterized DNA-binding homeobox-containing proteins and the different transcription and chromatin remodeling factors in which it is found [Doerks et al. 2001]). This domain is not present in the Itc1 proteins of the Saccharomycetaceae clade, the corresponding sequence being shorter and generally disordered (supplementary fig. S4B, Supplementary Material online). It is also not retrieved in Ascoidea rubescens Itc1, an observation which may support a placement of this species outside the methylotrophs clade, according to the comments and trees reported in recent studies (Riley et al. 2016; Shen et al. 2016).

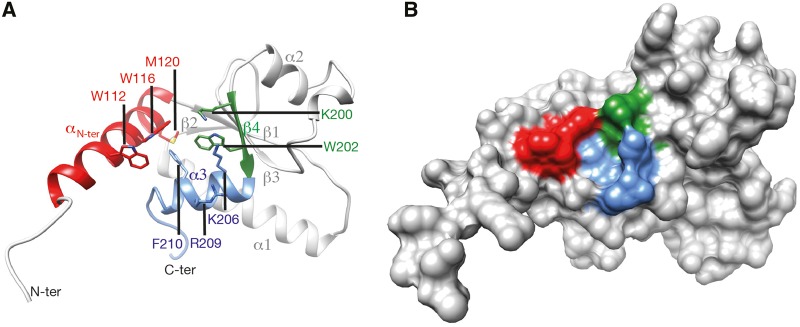

Conserved Sequence Features of H-BRCT Domains

The enlargement of the H-BRCT family to Sir4 and Itc1 allowed to identify the few conserved amino acids which may play a key functional role. The multiple sequence alignment of the Sir4, Dbf4, and Itc1 H-BRCT domains is shown in figure 4, together with the secondary structures observed in the S. cerevisiae Dbf4 H-BRCT 3D structure [PDB 3QBZ]. The corresponding 3D structure is reported in figure 5 (surface and ribbon representations), on which the highly conserved amino acids (stars in fig. 4) are highlighted. The Dbf4 H-BRCT domain consists in a bona fide BRCT core, comprising four β-strands and three α-helices, accompanied by a long N-terminal helix (α N-ter) that participates in the core of the domain. The concave surface defined by α1, β4, and α4, important for the binding of Dbf4 with Rad53 (Matthews et al. 2012), concentrates most of the amino acids that are conserved between Sir4, Itc1, and Dbf4 (fig. 5). Mutation of W202 (star in strand ß4) in yeast Dbf4 has been shown to cause increased sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents and hydroxyurea (Gabrielse et al. 2006) and to lose the interaction with Rad53 (Matthews et al. 2012). This interaction is also lost with mutations of W116 and M120 (stars in helix α Nter), as well in constructs with the L109A/W112D and W116D/M120A double mutations (Matthews et al. 2012). The importance of these amino acids has been suggested to be due to their participation in the hydrophobic core of the H-BRCT domain. However, one can also note that the four highly conserved aromatic amino acids (W202, W112, W116, and F210 in the S. cerevisiae Dbf4 sequence) form a putative binding cage (with F210 at the bottom, fig. 5), suggesting a possible role in the interaction.

Fig. 5.

—The H-BRCT domain 3D structure. Experimental 3D structure of the H-BRCT domain of S. cerevisiae Dbf4 (PDB 3QBZ; Matthews et al. 2012), on which are highlighted the highly conserved positions depicted with stars in figure 5. (A) Ribbon representation. (B) Solvent accessible surface.

The region encompassing the H-BRCT domain mediates the interaction of S. cerevisiae Sir4 with both peripheral membrane anchor Esc1 (Ansari and Gartenberg 1997; Andrulis et al. 2002; Taddei et al. 2004) and the Ty5 integrase (Zhu et al. 2003; Kvaratskhelia et al. 2014). Interestingly, Sir4 amino acids W974 and R975 (helix α Nter) have been shown to be critical for the interaction with Ty5, W974 occupying in Sir4 a position in Dbf4 (W112) that have been shown to be critical for interaction with Rad53 (Matthews et al. 2012).

To assess Sir4 H-BRCT domain function in S. cerevisiae, we mutated the conserved tryptophan residues W974 and W978 into alanine (sir4-AA; supplementary fig. S6A, Supplementary Material online). Integrated at the endogenous locus, the mutant allele impacts protein stability (moderately in exponentially growing cells, more severely in stationary cells) and causes a silencing defect at HML (supplementary fig. S6B and C, Supplementary Material online). This defect is suppressed by the addition of one or a few extra copies of sir4-AA (supplementary fig. S6C, Supplementary Material online), indicating that the two mutated residues are not essential for transcriptional silencing when Sir4 protein level is closer to wild-type level. In addition, these two residues are required neither for the protection of HML against HO cleavage nor for the repair of HO-induced double-strand break at MAT (supplementary fig. S6D, Supplementary Material online). These results do not support an essential role for Sir4 H-BRCT domain in transcriptional silencing, protection from HO-induced cutting and mating-type switching. However, they do not rule out a contributive role.

Identification of Conserved Motifs in Esc1

A clue for Sir4 H-BRCT domain function may come from its inclusion within the previously defined PAD of Sir4 (aa 960–1150), which interacts with the nuclear periphery protein Esc1 (Ansari and Gartenberg 1997; Andrulis et al. 2002; Taddei et al. 2004). Esc1 is a poorly defined protein. In S. cerevisiae, it anchors telomere at the nuclear periphery through its association with Sir4. This Esc1-dependent peripheral anchoring is a facultative contributor to transcriptional silencing (Andrulis et al. 2002; Taddei et al. 2004; Meister and Taddei 2013) and could be the function of Sir4 H-BRCT domain. Contrary to Sir4, Esc1 is not required for telomere protection against fusions by NHEJ (supplementary fig. S7, Supplementary Material online).

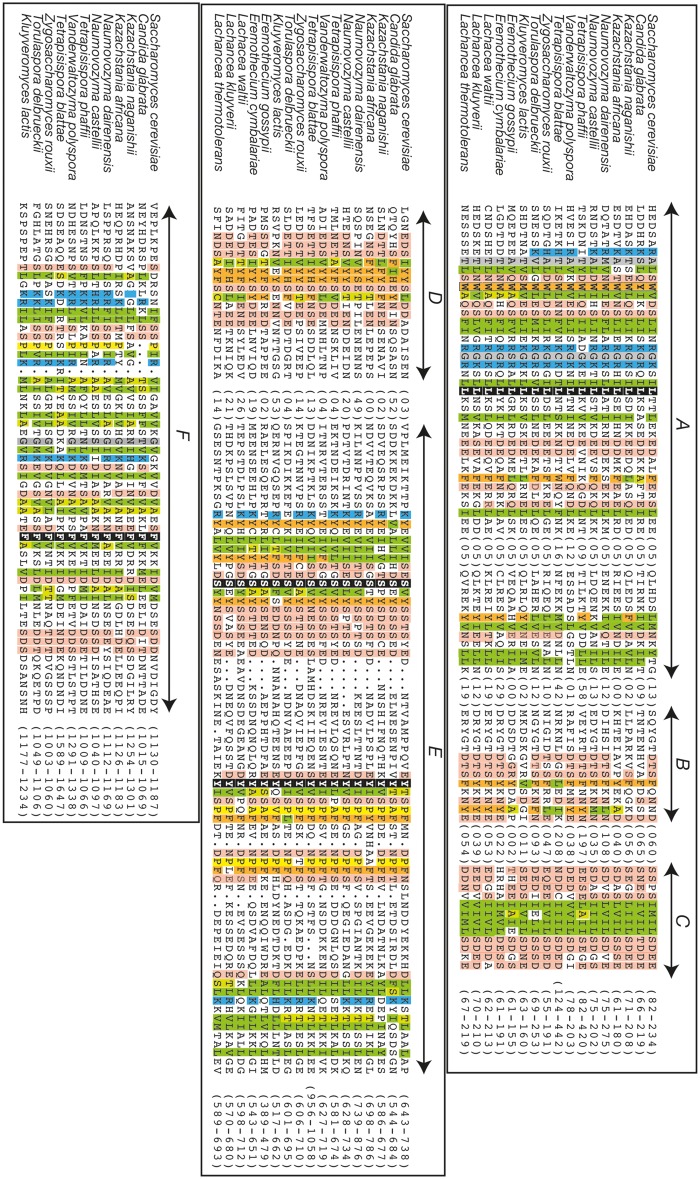

As Esc1 structure was unexplored, we searched for foldable regions in this large protein (1,658 amino acids). We identified six motifs conserved between Esc1 from the different species (Motifs Esc1-A to Esc1-F; figs. 1 and figs. 6, supplementary fig. S8, Supplementary Material online). Motif Esc1-A is predicted to form a globular domain, mainly made of α-helices. Motif Esc1-B appears less conserved in some sequences (such as C.glabrata and K.lactis), whereas motif Esc1-C, consisting of a β-strand motif followed by a serine and acidic sequences, evokes the possibility of a conserved SUMO-interacting motif (SIM) (Kerscher 2007). Note that this motif could be highlighted in some sequences (such as Tetrapisispora) only by visual inspection of the HCA plot, as it is short and separated from other conserved motifs by sequences of variable length (supplementary fig. S8, Supplementary Material online). Interestingly, the SUMO E3 ligase Siz2 SUMOylates Sir4 (in particular at position K1128, i.e., within the PAD downstream of the H-BCRT domain) and perinuclear anchoring through Sir4 also requires Siz2 (Ferreira et al. 2011; Kueng et al. 2012). In addition, Sir4, Esc1, and Siz2 are part of a larger complex with a subset of nucleoporins (Lapetina et al. 2017). The SIM within motif Esc1-C might thus contribute to the regulation of this complex. The two following conserved motifs (Esc1-D and Esc1-E) are found in all species of the Saccharomycetaceae family examined, including in particular some highly conserved aromatic amino acids. Finally, a conserved motif (Esc1-F), likely adopting a helical structure, is found in the C-terminal part of Esc1 proteins from the Saccharomycetaceae family, except from the Lachancea and Eremothecium (fig. 1). Note that the more divergent motif F of the C.glabrata Esc1 was found only after examination of the HCA plot (supplementary fig. S8, Supplementary Material online). The apparent absence of motif Esc1-F in species lacking a functional H-BRCT in Sir4 raises the interesting possibility that these two domains coevolve (although we cannot exclude that such a divergent motif is present but undetected yet in the Lachancea and Eremothecium sequences). Motif Esc1-F is unlikely to interact with Sir4 because the region sufficient for Esc1-Sir4 interaction is situated more downstream in Esc1 (aa 1395–1551; Andrulis et al. 2002). No conserved motif could, however, be highlighted in this region. No obvious similarity could also be highlighted with known 3D structures for the different motifs using HHpred and Phyre.

Fig. 6.

—The Esc1 conserved motifs. Multiple alignment of the Esc1 conserved motifs (A–E). In the alignments, positions conserved over the family are colored in green for hydrophobic amino acids (V, I, L, F, M, Y, W), light green for amino acids that can substitute for hydrophobic amino acids in a context-dependent way (A, T, S, C), orange for aromatic amino acids (F, Y, W), gray for small amino acids (G, V, A, S, T), yellow for P, blue for basic (K, R, H) amino acids, and pink for acidic (D, E, Q, N, S, T) amino acids. Domain limits (in brackets) are reported at the end of the sequences, and the UniProt identifiers of the sequences are reported in supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online.

Discussion

Sir4 is an essential scaffold for Sir complex assembly and the less understood component of yeast heterochromatin. Here, we find in Sir4 a functional Dbf4-related H-BRCT domain positioned within the PAD between the SID and the C-terminal coiled-coil. We predict a new functional region called TOC in Sir4 N-terminal region. Additionally, we identify six new conserved motifs in Sir4-interacting partner and nuclear-envelope associated protein Esc1. Finally, we find in species of the Sir4-free methylotrophs clade a related H-BRCT domain within a distinct protein, Itc1, a component of the chromatin remodeler ISWI2.

The molecular functions of these newly identified domains remain to be deciphered. As the TOC region is within an Sir4 region interacting with KU (Yku80), Rap1, and DNA (Kueng et al. 2012; Gartenberg and Smith 2016; Chen et al. 2018), it may contribute to these interactions. Sir4 H-BRCT interacts with Esc1 and therefore is likely to participate in heterochromatin anchoring at the nuclear periphery through this interaction, whose functional significance is to favor the establishment of a repressive domain within the nucleus (Meister and Taddei 2013).

Interestingly, on the one hand H-BRCT domains are missing in Sir4 from E. gossypii and E. cymbalariae (Eremothecium clade) and degenerated in the genus Lachancea. A commonality of these species is the absence of both Esc1 motif Esc1-F and the HO endonuclease (Butler et al. 2004; Wendland and Walther 2011; Agier et al. 2013). How they switch mating type is unknown. On the other hand, functional H-BRCT domain and Esc1 motif F are present in the genus K.lactis, also lacking HO, but where domesticated transposases (α3/Kat1) create double-strand DNA breaks at the MAT locus to induce mating-type switching (Barsoum et al. 2010; Rajaei et al. 2014). Thus, the presence of an H-BRCT domain in Sir4 and a motif F in Esc1 seems to correlate with how mating-type switching is induced. This observation suggests an unsuspected link between Esc1 and the recombination of MAT with the silent donors. Several models can be envisaged. For instance, the anchoring of silent mating-type cassettes to the nuclear periphery may contribute to homologous recombination within a heterochromatic template or to the maintenance of transcriptional silencing during and after repair, hypotheses remaining to be addressed. Sir4 and Esc1 may also act more indirectly by regulating checkpoint activation or replication origin firing.

The last hypotheses are relevant because DNA damage checkpoint is blind to mating-type switching (Pellicioli et al. 2001) and Sir4-associated replication origins are inefficient or inactive (Dubey et al. 1991; Palacios DeBeer and Fox 1999; Rivier et al. 1999; Vujcic et al. 1999; Sharma et al. 2001; Zappulla et al. 2002; Palacios DeBeer et al. 2003). These hypotheses would also link Sir4 H-BRCT function with the function of the H-BRCT originally found in the ubiquitous Dbf4, which is to regulate origin firing through an interaction with the checkpoint kinase Rad53 (Gabrielse et al. 2006; Lopez-Mosqueda et al. 2010; Zegerman and Diffley 2010; Matthews et al. 2012, 2014; Chen et al. 2013) (reviewed by Diffley [2010]). Remarkably, Sir3 originates from the ORC subunit Orc1 through the last WGD (Byrne and Wolfe 2005; Gartenberg and Smith 2016). In K. lactis, a pre-WGD species of the Saccharomycetaceae family, Orc1 is required for heterochromatin and a likely partner of Sir4 (Hickman and Rusche 2010; Hickman et al. 2011; Hanner and Rusche 2017). The finding reported here adds a novel example suggesting that yeast heterochromatin evolved in part from the replication initiation machinery. The significance of this origin remains to be understood.

Itc1 is a regulatory subunit of the ISWI2 chromatin remodeler. In S. cerevisiae, it contributes to the transcriptional repression of mating-type-specific genes (Fazzio et al. 2001; Ruiz et al. 2003). Addressing the role of Itc1 and its H-BRCT domain in methylotrophs could be an entry point to decipher the mechanisms behind the two MAT-like-loci system of these yeasts apparently lacking Sir4 and HP1. Together, our findings show the importance of exploring the dark proteome and provide new insights on the evolution of yeast heterochromatin and life cycle.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Angela Taddei, Karine Dubrana, and Jean-Paul Mornon for fruitful discussions and Didier Busso and Eléa Dizet (cigex platform) for the sir4-AA mutant plasmid. This work was supported by grants from Agence pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (subvention Fondation ARC) and Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Blanc-SVSE-8-2011-TELO&DICENs and ANR-14-CE10-0021-DICENs).

Data availaibility: All the analyzed sequences (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online) are publicly available from UniProt. The 3D structure coordinates are publicly available from RCSB Protein Data Bank.

Literature Cited

- Agier N, Romano OM, Touzain F, Cosentino Lagomarsino M, Fischer G.. 2013. The spatiotemporal program of replication in the genome of Lachancea kluyveri. Genome Biol Evol. 5(2):370–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allshire RC, Madhani HD.. 2018. Ten principles of heterochromatin formation and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 19(4):229–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, et al. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25(17):3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrulis ED, et al. 2002. Esc1, a nuclear periphery protein required for Sir4-based plasmid anchoring and partitioning. Mol Cell Biol. 22(23):8292–8301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari A, Gartenberg MR.. 1997. The yeast silent information regulator Sir4p anchors and partitions plasmids. Mol Cell Biol. 17(12):7061–7068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aström S, Rine J.. 1998. Theme and variation among silencing proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces lactis. Genetics 148(3):1021–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsoum E, Martinez P, Aström SU.. 2010. Alpha3, a transposable element that promotes host sexual reproduction. Genes Dev. 24(1):33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batté A, et al. 2017. Recombination at subtelomeres is regulated by physical distance, double-strand break resection and chromatin status. EMBO J. 36(17):2609–2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrouzi R, et al. 2016. Heterochromatin assembly by interrupted Sir3 bridges across neighboring nucleosomes. Elife 5:e17556.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RJ, Johnson AD.. 2005. Mating in Candida albicans and the search for a sexual cycle. Annu Rev Microbiol. 59:233–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett-Lovsey RM, Herbert AD, Sternberg MJE, Kelley LA.. 2008. Exploring the extremes of sequence/structure space with ensemble fold recognition in the program Phyre. Proteins 70(3):611–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitard-Feildel T, Callebaut I.. 2017. Exploring the dark foldable proteome by considering hydrophobic amino acids topology. Sci Rep. 7:41425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitard-Feildel T, Heberlein M, Bornberg-Bauer E, Callebaut I.. 2015. Detection of orphan domains in Drosophila using “hydrophobic cluster analysis.” Biochimie 119: 244–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitard-Feildel T, Lamiable A, Mornon JP, Callebaut I.. 2018. Order in disorder as observed by the “hydrophobic cluster analysis” of protein sequences. Proteomics. 18(21–22):e1800054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchberger JR, et al. 2008. Sir3-nucleosome interactions in spreading of silent chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 28(22):6903–6918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck S, Shore D.. 1995. Action of a RAP1 carboxy-terminal silencing domain reveals an underlying competition between HMR and telomeres in yeast. Genes Dev. 9(3):370–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler G, et al. 2004. Evolution of the MAT locus and its Ho endonuclease in yeast species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101(6):1632–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne KP, Wolfe KH.. 2005. The Yeast Gene Order Browser: combining curated homology and syntenic context reveals gene fate in polyploid species. Genome Res. 15(10):1456–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callebaut I, et al. 1997. Deciphering protein sequence information through hydrophobic cluster analysis (HCA): current status and perspectives. Cell Mol Life Sci. 53(8):621–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callebaut I, Mornon J-P.. 1997. From BRCA1 to RAP1: a widespread BRCT module closely associated with DNA repair. FEBS Lett. 400(1):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JF, et al. 2003. Structure of the coiled-coil dimerization motif of Sir4 and its interaction with Sir3. Structure 11(6):637–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, et al. 2018. Structural insights into yeast telomerase recruitment to telomeres. Cell 172(1–2):331–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-C, et al. 2013. DNA replication checkpoint signaling depends on a Rad53-Dbf4 N-terminal interaction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 194(2):389–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockell MM, Perrod S, Gasser SM.. 2000. Analysis of Sir2p domains required for rDNA and telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 154(3):1069–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan AY, Hanson SJ, Byrne KP, Wolfe KH.. 2016. Centromeres of the yeast Komagataella phaffii (Pichia pastoris) have a simple inverted-repeat structure. Genome Biol Evol. 8(8):2482–2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubizolles F, Martino F, Perrod S, Gasser SM.. 2006. A homotrimer-heterotrimer switch in Sir2 structure differentiates rDNA and telomeric silencing. Mol Cell. 21(6):825–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin CD, Borneman AR, Chambers PJ, Pretorius I.. 2012. De-novo assembly and analysis of the heterozygous triploid genome of the wine spoilage yeast Dekkera bruxellensis AWRI1499. PLoS One 7(3):e33840.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schutter K, et al. 2009. Genome sequence of the recombinant protein production host Pichia pastoris. Nat Biotechnol. 27(6):561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diffley J. 2010. The many faces of redundancy in DNA replication control. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 75:135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerks T, Copley R, Bork P.. 2001. DDT—a novel domain in different transcription and chromosome remodeling factors. Trends Biochem Sci. 26(3):145–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosztányi Z, Csizmók V, Tompa P, Simon I.. 2005a. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics 21:3433–3434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosztányi Z, Csizmók V, Tompa P, Simon I.. 2005b. The pairwise energy content estimated from amino acid composition discriminates between folded and intrinsically unstructured proteins. J Mol Biol. 347(4):827–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosztányi Z, Mészáros B, Simon I.. 2009. ANCHOR: web server for predicting protein binding regions in disordered proteins. Bioinformatics 25(20):2745–2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey DD, et al. 1991. Evidence suggesting that the ARS elements associated with silencers of the yeast mating-type locus HML do not function as chromosomal DNA replication origins. Mol Cell Biol. 11(10):5346–5355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujon B. 2010. Yeast evolutionary genomics. Nat Rev Genet. 11(7):512–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eudes R, Le Tuan K, Delettré J, Mornon J, Callebaut I.. 2007. A generalized analysis of hydrophobic and loop clusters within globular protein sequences. BMC Struct Biol. 7:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure G, Callebaut I.. 2013a. Comprehensive repertoire of foldable regions within whole genomes. PLoS Comput Biol. 9(10):e1003280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure G, Callebaut I.. 2013b. Identification of hidden relationships from the coupling of hydrophobic cluster analysis and domain architecture information. Bioinformatics 29(14):1726–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzio TG, et al. 2001. Widespread collaboration of Isw2 and Sin3-Rpd3 chromatin remodeling complexes in transcriptional repression. Mol Cell Biol. 21(19):6450–6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira HC, et al. 2011. The PIAS homologue Siz2 regulates perinuclear telomere position and telomerase activity in budding yeast. Nat Cell Biol. 13(7):867–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaboriaud C, Bissery V, Benchetrit T, Mornon JP.. 1987. Hydrophobic cluster analysis: an efficient new way to compare and analyse amino acid sequences. FEBS Lett. 224(1):149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielse C, et al. 2006. A Dbf4p BRCA1 C-terminal-like domain required for the response to replication fork arrest in budding yeast. Genetics 173(2):541–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartenberg MR, Smith JS.. 2016. The nuts and bolts of transcriptionally silent chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 203(4):1563–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Génolevures Consortium. 2009. Comparative genomics of protoploid Saccharomycetaceae. Genome Res. 19:1696–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghidelli S, Donze D, Dhillon N, Kamakaka RT.. 2001. Sir2p exists in two nucleosome-binding complexes with distinct deacetylase activities. EMBO J. 20(16):4522–4535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JL, et al. 2011. Evolutionary erosion of yeast sex chromosomes by mating-type switching accidents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 108(50):20024–20029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Metoz F.. 1999. ESPript: multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics 15(4):305–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidi M, et al. 2015. Spatial reorganization of telomeres in long-lived quiescent cells. Genome Biol. 16:206.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber JE. 2012. Mating-type genes and MAT switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 191(1):33–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanner AS, Rusche LN.. 2017. The yeast heterochromatin protein Sir3 experienced functional changes in the AAA+ domain after gene duplication and subfunctionalization. Genetics 207(2):517–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson S, Byrne K, Wolfe K.. 2014. Mating-type switching by chromosomal inversion in methylotrophic yeasts suggests an origin for the three-locus Saccharomyces cerevisae system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111(45):E4851–E4858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson SJ, Byrne KP, Wolfe KH.. 2017. Flip/flop mating-type switching in the methylotrophic yeast Ogataea polymorpha is regulated by an Efg1-Rme1-Ste12 pathway. PLoS Genet. 13(11):e1007092.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson SJ, Wolfe KH.. 2017. An evolutionary perspective on yeast mating-type switching. Genetics 206(1):9–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hass EP, Zappulla DC.. 2015. The Ku subunit of telomerase binds Sir4 to recruit telomerase to lengthen telomeres in S. cerevisiae. Elife 4:e07750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman MA, Froyd CA, Rusche LN.. 2011. Reinventing heterochromatin in budding yeasts: sir2 and the origin recognition complex take center stage. Eukaryot Cell. 10(9):1183–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman MA, Rusche LN.. 2009. The Sir2-Sum1 complex represses transcription using both promoter-specific and long-range mechanisms to regulate cell identity and sexual cycle in the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis. PLoS Genet. 5(11):e1000710.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman MA, Rusche LN.. 2010. Transcriptional silencing functions of the yeast protein Orc1/Sir3 subfunctionalized after gene duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107(45):19384–19389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JB, Herskowitz I.. 1976. Interconversion of yeast mating types I. Direct observations of the action of the homothallism (HO) gene. Genetics 83(2):245–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocher A, et al. 2018. Expanding heterochromatin reveals discrete subtelomeric domains delimited by chromatin landscape transitions. Genome Res. 28(12):1867–1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hoppe GJ, et al. 2002. Steps in assembly of silent chromatin in yeast: Sir3-independent binding of a Sir2/Sir4 complex to silencers and role for Sir2-dependent deacetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 22(12):4167–4180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H-C, et al. 2013. Structural basis for allosteric stimulation of Sir2 activity by Sir4 binding. Genes Dev. 27(1):64–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, et al. 1999. ACF consists of two subunits, Acf1 and ISWI, that function cooperatively in the ATP-dependent catalysis of chromatin assembly. Genes Dev. 13(12):1529–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerscher O. 2007. SUMO junction—what’s your function? New insights through SUMO-interacting motifs. EMBO Rep. 8(6):550–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin EV, Altschul SF, Bork P.. 1996. BRCA1 protein products … Functional motifs…. Nat Genet 13(3):266–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuberl A, et al. 2011. High-quality genome sequence of Pichia pastoris CBS7435. J Biotechnol. 154:312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kueng S, et al. 2012. Regulating repression: roles for the sir4 N-terminus in linker DNA protection and stabilization of epigenetic states. PLoS Genet. 8(5):e1002727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvaratskhelia M, Sharma A, Larue RC, Serrao E, Engelman A.. 2014. Molecular mechanisms of retroviral integration site selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 42(16):10209–10225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapetina DL, Ptak C, Roesner UK, Wozniak RW.. 2017. Yeast silencing factor Sir4 and a subset of nucleoporins form a complex distinct from nuclear pore complexes. J Cell Biol. 216(10):3145–3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche T, et al. 1998. Mutation of yeast Ku genes disrupts the subnuclear organization of telomeres. Curr Biol. 8(11):653–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson AG, et al. 2017. Liquid droplet formation by HP1α suggests a role for phase separation in heterochromatin. Nature 547(7662):236–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le S, Davis C, Konopka JB, Sternglanz R.. 1997. Two new S-phase-specific genes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 13(11):1029–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung CC, Glover JN.. 2011. BRCT domains: easy as one, two, three. Cell Cycle 10(15):2461–2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Mosqueda J, et al. 2010. Damage-induced phosphorylation of Sld3 is important to block late origin firing. Nature 467(7314):479–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo K, Vega-Palas MA, Grunstein M.. 2002. Rap1-Sir4 binding independent of other Sir, yKu, or histone interactions initiates the assembly of telomeric heterochromatin in yeast. Genes Dev. 16(12):1528–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida S, et al. 2018. Structural basis of heterochromatin formation by human HP1. Mol Cell. 69(3):385–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa H, Kaneko Y.. 2014. Inversion of the chromosomal region between two mating type loci switches the mating type in Hansenula polymorpha. PLoS Genet. 10(11):e1004796.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillet L, et al. 1996. Evidence for silencing compartments within the yeast nucleus: a role for telomere proximity and Sir protein concentration in silencer-mediated repression. Genes Dev. 10(14):1796–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcand S, Buck SW, Moretti P, Gilson E, Shore D.. 1996. Silencing of genes at nontelomeric sites in yeast is controlled by sequestration of silencing factors at telomeres by Rap 1 protein. Genes Dev. 10(11):1297–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcand S, Pardo B, Gratias A, Cahun S, Callebaut I.. 2008. Multiple pathways inhibit NHEJ at telomeres. Genes Dev. 22(9):1153–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SG, Laroche T, Suka N, Grunstein M, Gasser SM.. 1999. Relocalization of telomeric Ku and SIR proteins in response to DNA strand breaks in yeast. Cell 97(5):621–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews L, et al. 2014. A novel non-canonical forkhead-associated (FHA) domain-binding interface mediates the interaction between Rad53 and Dbf4 proteins. J Biol Chem. 289(5):2589–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews LA, Jones DR, Prasad AA, Duncker BP, Guarné A.. 2012. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Dbf4 has unique fold necessary for interaction with Rad53 kinase. J Biol Chem. 287(4):2378–2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier A, Söding J.. 2015. Automatic prediction of protein 3D structures by probabilistic multi-template homology modeling. PLoS Comput Biol. 11(10):e1004343.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister P, Taddei A.. 2013. Building silent compartments at the nuclear periphery: a recurrent theme. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 23(2):96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mészáros B, Simon I, Dosztányi Z.. 2009. Prediction of protein binding regions in disordered proteins. PLoS Comput Biol. 5(5):e1000376.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra K, Shore D.. 1999. Yeast Ku protein plays a direct role in telomeric silencing and counteracts inhibition by rif proteins. Curr Biol. 9(19):1123–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moazed D, Kistler A, Axelrod A, Rine J, Johnson AD.. 1997. Silent information regulator protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a SIR2/SIR4 complex and evidence for a regulatory domain in SIR4 that inhibits its interaction with SIR3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 94(6):2186–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales L, et al. 2013. Complete DNA sequence of Kuraishia capsulata illustrates novel genomic features among budding yeasts (Saccharomycotina). Genome Biol Evol. 5(12):2524–2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti P, Freeman K, Coodly L, Shore D.. 1994. Evidence that a complex of SIR proteins interacts with the silencer and telomere-binding protein RAP1. Genes Dev. 8(19):2257–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GA, et al. 2003. The Sir4 C-terminal coiled coil is required for telomeric and mating type silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Mol Biol. 334(4):769–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios DeBeer M, Fox C.. 1999. A role for a replicator dominance mechanism in silencing. EMBO J. 18(13):3808–3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios DeBeer MA, Muller U, Fox C.. 2003. Differential DNA affinity specifies roles for the origin recognition complex in budding yeast heterochromatin. Genes Dev. 17(15):1817–1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Hanish J, Lustig AJ.. 1998. Sir3p domains involved in the initiation of telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 150(3):977–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicioli A, Lee SE, Lucca C, Foiani M, Haber JE.. 2001. Regulation of Saccharomyces Rad53 checkpoint kinase during adaptation from DNA damage-induced G2/M arrest. Mol Cell. 7(2):293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, et al. 2004. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 25(13):1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piskur J, et al. 2012. The genome of wine yeast Dekkera bruxellensis provides a tool to explore its food-related properties. Int J Food Microbiol. 157:202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaei N, Chiruvella KK, Lin F, Aström SU.. 2014. Domesticated transposase Kat1 and its fossil imprints induce sexual differentiation in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111(43):15491–15496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravin NV, et al. 2013. Genome sequence and analysis of methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha DL1. BMC Genomics 14:837.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remmert M, Biegert A, Hauser A, Söding J.. 2011. HHblits: lightning-fast iterative protein sequence searching by HMM-HMM alignment. Nat Methods. 25:173–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribes-Zamora A, Mihalek I, Lichtarge O, Bertuch AA.. 2007. Distinct faces of the Ku heterodimer mediate DNA repair and telomeric functions. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 14(4):301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley R, et al. 2016. Comparative genomics of biotechnologically important yeasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 113(35):9882–9887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivier DH, Ekena JL, Rine J.. 1999. HMR-I is an origin of replication and a silencer in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 151(2):521–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy R, Meier B, McAinsh AD, Feldmann HM, Jackson SP.. 2004. Separation-of-function mutants of yeast Ku80 reveal a Yku80p-Sir4p interaction involved in telomeric silencing. J Biol Chem. 279(1):86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruault M, De Meyer A, Loïodice I, Taddei A.. 2011. Clustering heterochromatin: Sir3 promotes telomere clustering independently of silencing in yeast. J Cell Biol. 192(3):417–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz C, Escribano V, Morgado E, Molina M, Mazón MJ.. 2003. Cell-type-dependent repression of yeast a-specific genes requires Itc1p, a subunit of the Isw2p-Itc1p chromatin remodelling complex. Microbiology 149(Pt 2):341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K, Weinberger M, Huberman JA.. 2001. Roles for internal and flanking sequences in regulating the activity of mating-type-silencer-associated replication origins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 159(1):35–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X-X, et al. 2016. Reconstructing the backbone of the Saccharomycotina yeast phylogeny using genome-scale data. G3 (Bethesda) 6(12):3927–3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathern JN, et al. 1982. Homothallic switching of yeast mating type cassettes is initiated by a double-stranded cut in the MAT locus. Cell 31(1):183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom AR, et al. 2017. Phase separation drives heterochromatin domain formation. Nature 547(7662):241–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei A, Hediger F, Neumann FR, Bauer C, Gasser SM.. 2004. Separation of silencing from perinuclear anchoring functions in yeast Ku80, Sir4 and Esc1 proteins. EMBO J. 23(6):1301–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanny JC, Kirkpatrick DS, Gerber SA, Gygi SP, Moazed D.. 2004. Budding yeast silencing complexes and regulation of Sir2 activity by protein-protein interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 24(16):6931–6946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatarakis A, Behrouzi R, Moazed D.. 2017. Evolving models of heterochromatin: from foci to liquid droplets. Mol Cell. 67(5):725–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto Y, Kato J, Ikeda H.. 1997. Silencing factors participate in DNA repair and recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 388(6645):900–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujcic M, Miller CA, Kowalski D.. 1999. Activation of silent replication origins at autonomously replicating sequence elements near the HML locus in budding yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 19(9):6098–6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendland J, Walther A.. 2011. Genome evolution in the eremothecium clade of the Saccharomyces complex revealed by comparative genomics. G3 (Bethesda) 1(7):539–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe KH, Butler G.. 2017. Evolution of mating in the Saccharomycotina. Annu Rev Microbiol. 71:197–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zegerman P, Diffley JF.. 2010. Checkpoint-dependent inhibition of DNA replication initiation by Sld3 and Dbf4 phosphorylation. Nature 467(7314):474–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappulla DC, Sternglanz R, Leatherwood J.. 2002. Control of replication timing by a transcriptional silencer. Cur Biol. 12(11):869–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Dai J, Fuerst PG, Voytas DF.. 2003. Controlling integration specificity of a yeast retrotransposon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 100(10):5891–5895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.