Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a frequent cause of heart failure and a common indication for heart transplantation. Dilated cardiomyopathy has a strong genetic basis, and the most common disease-causing mutations are variants that truncate the sarcomeric protein titin (TTN-truncating variants [TTNtvs] are prevalent in 25%1 of familial DCM cases and 13%2 of idiopathic DCM cases). The prognosis of DCM is poor, but functional recovery from end-stage failure has been reported following both optimal medical therapy3 and left ventricular assist device (LVAD) support,4,5 although the determinants of successful recovery are unknown. It has been proposed that recovery from genetic cardiomyopathy may not be expected because the underlying cause is irreversible, whereas recovery may be more likely when DCM is caused by reversible, nongenetic factors (eg, myocarditis).6 To address this directly, we sequenced TTN in patients with end-stage DCM who either recovered or did not recover following LVAD support.

Methods

We sequenced TTN in 70 patients referred to the Royal Brompton and Harefield National Health Service Trust between 1998 and 2010 for LVAD implantation owing to nonischemic, medically refractory, end-stage DCM. Of these, 29 patients recovered cardiac function during LVAD support and had their LVAD explanted. The other 41 patients did not recover cardiac function and underwent transplant or died while on LVAD support. A pharmacological regimen designed to promote recovery (combination therapy4,5) was used in 45 of 70 patients and continued after explantation. The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service Committee South Central, Hampshire B, with written informed consent from participants.

Targeted next-generation sequencing was performed using an assay designed to assess all known coding exons in TTN.2 Genetic variants in next-generation sequencing data were identified as previously described2 and were confirmed independently. Statistical comparisons between groups were tested using the Fisher exact test, analysis of variance, and unpaired t test as appropriate. Differences in survival rates were tested using the Mantel-Cox test. Statistical significance was defined as a P value of less than .05.

Results

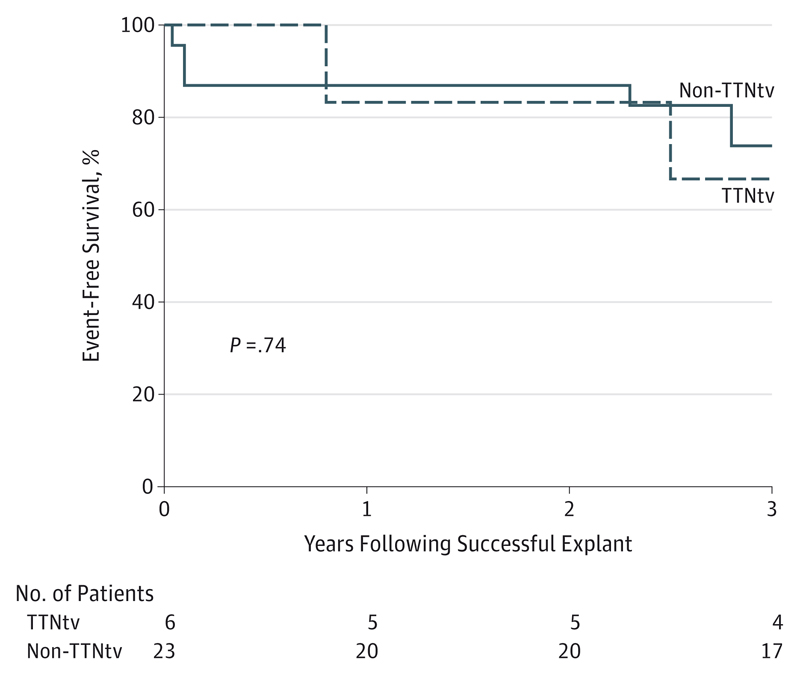

We identified TTNtvs in 10 of 70 patients (14% of total; Table). The TTNtvs were considered disease-causing because all variants were located in exons constitutively expressed in the heart and were either novel or very rare. Nine TTNtvs were not present in the Exome Aggregation Consortium,7 while 1 variant had a minor allele frequency of 0.0000166.2 Of the patients with a TTNtv, 6 of 10 recovered sufficient cardiac function to enable LVAD explantation. There was no statistical difference in TTNtv frequency between recovery patients and those who underwent transplant or died with the device (6 of 29 [21%] vs 4 of 41 [10%], P = .30) and no evidence of clinical differences between TTNtv-positive and TTNtv-negative cases at the time of LVAD implantation (Table). Comparing the transplant-free survival rate in recovered patients, we found no difference between TTNtv-positive and TTNtv-negative cases; at 3 years postexplant, 4 of 6 TTNtv-positive cases (67%) were free from death and transplantation compared with 17 of 23 TTNtv-negative cases (74%) (Figure; P = .74).

Table. TTNtv Status and Clinical Features of Patients With LVAD-Supported, End-Stage DCM Who Either Recovered Cardiac Function and Had Successful Explantation (Recovered), or Who Had Transplantation or Died With the Device In Situ (Not Recovered).

| Variable | TTNtva (n = 10) |

No TTNtv (n = 60) |

P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recoveredb | Not Recoveredc | Recovered | Not Recovered | ||

| No. of patients | 6 | 4 | 23 | 37 | .30d |

| Male, No. (%) | 6 (100) | 4 (100) | 18 (78) | 30 (81) | .29d |

| Clinical comments | None | 1 Postchemotherapy | 2 PPCM | 3 PPCM 2 Postchemotherapy |

|

| Family history, No. (%) | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (2.7) | >.99d |

| Survived >30 d post-LVAD implant, No. (%) | 6 (100) | 2 (50) | 23 (100) | 34 (92) | .13d |

| Received combination therapy,3 No. (%) | 6 (100) | 2 (50) | 23 (100) | 14 (38) | .69d |

| Age, mean (SD), y | |||||

| At diagnosis | 31.7 (10.8) | 37.3 (15.6) | 31.6 (12.5) | 34.5 (11.9) | .77e |

| At implant | 33.0 (12.2) | 38.6 (17.3) | 35.5 (12.8) | 37.5 (12.8) | .83e |

| Implant, mean (SD) | |||||

| LVEF, % | 25.6 (13.3) | 19.7 (9.5) | 20.8 (10.1) | 18.8 (9.6) | .58e |

| FS, % | 10.3 (4.6) | 8.5 (3.4) | 9.3 (3.9) | 8.6 (4.2) | .90e |

| LVEDD, mm | 69.8 (6.6) | 72.3 (10.4) | 73.1 (14.3) | 71.7 (9.6) | .95e |

| Time on LVAD, mean (SD), d | 214 (125) | 212 (313) | 317 (151) | 520 (532) | .11e |

| Explant, mean (SD) | |||||

| LVEF, % | 64.0 (4.2) | NA | 65.9 (9.5) | NA | .64f |

| FS, % | 29.5 (3.3) | NA | 31.9 (7.3) | NA | .53f |

| LVEDD, mm | 44.5 (6.4) | NA | 54.3 (8.9) | NA | .05f |

Abbreviations: DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; FS, fractional shortening; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEDD, left ventricular end diastolic dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NA, not applicable; PPCM, peripartum cardiomyopathy; TTNtv, titin truncating variant.

TTNtv position is given according to locus reference genomic (LRG) sequence 391_t1. A detailed overview of TTN gene structure, including the isoforms and protein domains affected by the TTNtvs described here, can be found at http://cardiodb.org/titin.

TTNtvs in cohort who recovered: c.87624C>A; c.49346-1G>A; c.76383_76386delTAAT; c.46782C>A; c.81518delC (variants reported in Roberts et al2); and c.71326G>T.

TTNtvs in cohort who did not recover: c.67495C>T 58172delA; c.58172delA (variants reported in Roberts et al2); c.69976G>T; and c.41641C>T.

P values calculated with Fisher exact test.

P values calculated with analysis of variance.

P values calculated by unpaired t test.

Figure. Titin-Truncating Variant (TTNtv) and Survival in Recovered Patients With Dilated Cardiomyopathy.

In the 3 years following successful left ventricular assist device explantation, the actuarial rate of survival and freedom from transplant at 1, 2, and 3 years postexplant in TTNtv-positive cases was 83%, 83%, and 67%. In TTNtv-negative cases, the rate was 88%, 88%, and 75%. Differences between the survival rates were tested using the Mantel-Cox test.

Discussion

Sustained improvement in cardiac function is observed in end-stage DCM following medical therapy and LVAD support, but to our knowledge, it was previously unknown whether recovery could be achieved in DCM caused by a genetic mutation. Here, we show that recovery is possible in DCM caused by a truncating mutation in the TTN gene. We also present the preliminary findings that DCM with a TTNtv is as recoverable as DCM without a TTNtv and that the long-term durability of recovery is also comparable. These observations now require replication in multicenter prospective studies. Because TTNtvs are the most common genetic cause of DCM, these results have important implications for patient selection for recovery programs.7 Nine TTNtvs were not present in the Exome Aggregation Consortium, while 1 variant had a minor allele frequency of 0.0000166.7

Funding/Support

This work was supported by the Fondation Leducq, Heart Research UK, the Wellcome Trust, and the National Institute for Health Research Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit at the Royal Brompton and Harefield National Health Service Foundation Trust and Imperial College London.

Role of the Funders/Sponsors: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Felkin had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Felkin, Yacoub, Birks, Barton, Cook.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Felkin, Walsh, Ware, Birks, Barton, Cook.

Drafting of the manuscript: Felkin, Yacoub, Barton, Cook.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Felkin, Walsh, Ware.

Obtained funding: Barton, Cook.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Felkin, Walsh, Birks, Barton.

Study supervision: Yacoub, Birks, Barton, Cook.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Additional Contributions: We thank all the patients who participated in this study, Rachel Buchan, BSc, MSc (Royal Brompton Hospital), for technical support and Paula Rogers, RGN, BSc, MSc (Harefield Hospital), for assistance in the collection of patient data. These contributors received no compensation for their assistance aside from employment at the institutions where the study was conducted.

Contributor Information

Leanne E. Felkin, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, England.

Roddy Walsh, National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Unit in Cardiovascular Disease at Royal Brompton and Harefield National Health Service Foundation Trust and Imperial College London, London, England.

James S. Ware, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, England.

Magdi H. Yacoub, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, England.

Emma J. Birks, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky.

Paul J. R. Barton, National InstituteforHealth Research Biomedical Research Unit in Cardiovascular Disease at Royal Brompton and Harefield National Health Service Foundation Trust and Imperial College London, London, England.

Stuart A. Cook, National Heart Centre Singapore, Singapore.

References

- 1.Herman DS, Lam L, Taylor MR, et al. Truncations of titin causing dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(7):619–628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts AM, Ware JS, Herman DS, et al. Integrated allelic, transcriptional, and phenomic dissection of the cardiac effects of titin truncations in health and disease. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(270):270ra6. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merlo M, Stolfo D, Anzini M, et al. Persistent recovery of normal left ventricular function and dimension in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy during long-term follow-up: does real healing exist? J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(1):e001504. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birks EJ, Tansley PD, Hardy J, et al. Left ventricular assist device and drug therapy for the reversal of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(18):1873–1884. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birks EJ, George RS, Hedger M, et al. Reversal of severe heart failure with a continuous-flow left ventricular assist device and pharmacological therapy: a prospective study. Circulation. 2011;123(4):381–390. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.933960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann DL, Barger PM, Burkhoff D. Myocardial recovery and the failing heart: myth, magic, or molecular target? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(24):2465–2472. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Exome Aggregation Consortium: ExAc browser (beta) [Accessed January 21, 2015]; http://exac.broadinstitute.org/