Abstract

This article presents methods for generating in vitro fibrin clots and analyzing the effect of beta-amyloid (Aβ) protein on clot formation and structure by spectrometry and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Aβ, which forms neurotoxic amyloid aggregates in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), has been shown to interact with fibrinogen. This Aβ-fibrinogen interaction makes the fibrin clot structurally abnormal and resistant to fibrinolysis. Aβ-induced abnormalities in fibrin clotting may also contribute to cerebrovascular aspects of the AD pathology such as microinfarcts, inflammation, as well as, cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Given the potentially critical role of neurovascular deficits in AD pathology, developing compounds which can inhibit or lessen the Aβ-fibrinogen interaction has promising therapeutic value. In vitro methods by which fibrin clot formation can be easily and systematically assessed are potentially useful tools for developing therapeutic compounds. Presented here is an optimized protocol for in vitro generation of the fibrin clot, as well as analysis of the effect of Aβ and Aβ-fibrinogen interaction inhibitors. The clot turbidity assay is rapid, highly reproducible and can be used to test multiple conditions simultaneously, allowing for the screening of large numbers of Aβ-fibrinogen inhibitors. Hit compounds from this screening can be further evaluated for their ability to ameliorate Aβ-induced structural abnormalities of the fibrin clot architecture using SEM. The effectiveness of these optimized protocols is demonstrated here using TDI-2760, a recently identified Aβ-fibrinogen interaction inhibitor.

Keywords: Biochemistry, Issue 141, Fibrinogen, beta-amyloid, Alzheimer’s disease, blood, spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a neurodegenerative disease leading to cognitive decline in elderly patients, predominately arises from abnormal beta-amyloid (Aβ) expression, aggregation and impaired clearance resulting in neurotoxicity1,2. Despite the well-characterized association between Aβ aggregates and AD3, the precise mechanisms underlying the disease pathology are not well understood4. Increasing evidence suggests that neurovascular deficits play a role in the progression and severity of AD5, as Aβ directly interacts with the components of the circulatory system6. Aβ has a high-affinity interaction with fibrinogen7,8, which also localizes to Aβ deposits in both AD patients and mouse models9,10,11. Furthermore, the Aβ-fibrinogen interaction induces abnormal fibrin-clot formation and structure, as well as resistance to fibrinolysis9,12. One therapeutic possibility in treating AD, is alleviating circulatory deficits by inhibiting the interaction between Aβ and fibrinogen13,14. We, therefore, identified several small compounds inhibiting the Aβ-fibrinogen interaction using high throughput screening and medicinal chemistry approaches13,14. To test the efficacy of Aβ-fibrinogen interaction inhibitors, we optimized two methods for the analysis of in vitro fibrin clot formation: clot turbidity assay and scanning electron microscopy (SEM)14.

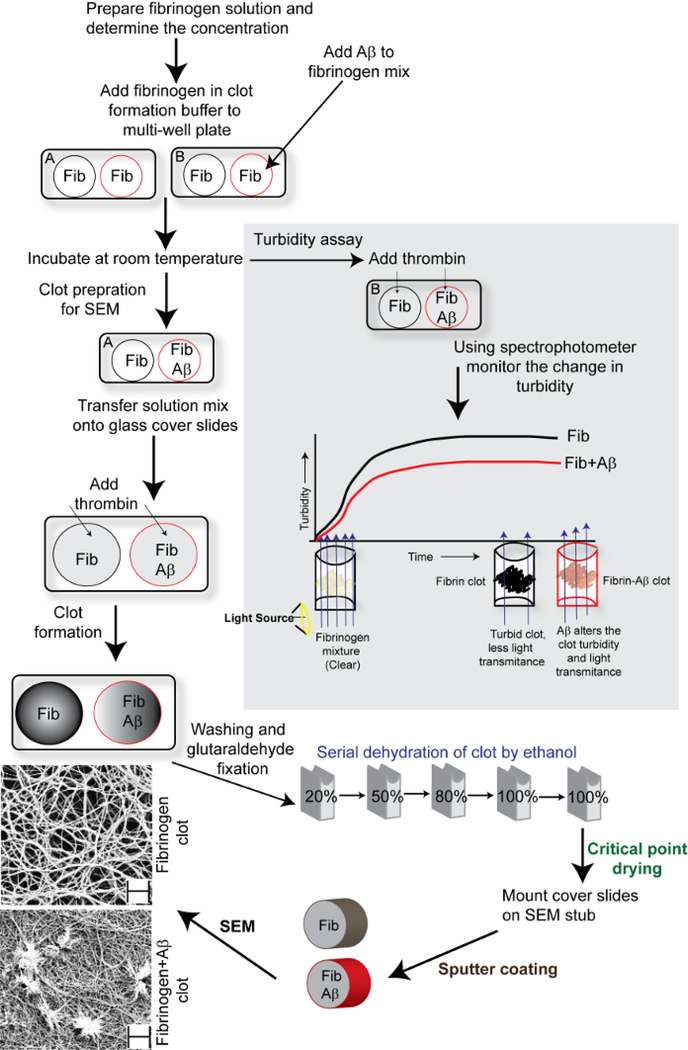

Clot turbidity assay is a straight-forward and rapid method for monitoring fibrin clot formation using UV-visible spectroscopy. As the fibrin clot forms, light is increasingly scattered and the turbidity of the solution increases. Conversely, when Aβ is present, the structure of the fibrin clot is altered, and the turbidity of the mixture is reduced (Figure 1). The effect of inhibitory compounds can be assessed for the potential to restore clot turbidity from Aβ-induced abnormalities. While the turbidity assay allows for rapid analysis of multiple conditions, it provides limited information on the clot shape and structure. SEM, in which the topography of solid objects is revealed by electron probe, allows for the analysis of the 3D architecture of the clot15,16,17,18 and the assessment of how the presence of Aβ and/or inhibitory compounds alters that structure9,14. Both spectrometry and SEM are classical laboratory techniques that have been used for various purposes, for example, spectrophotometry is used for monitoring amyloid aggregation19,20. Similarly, SEM is also used to analyze fibrin clot formed from the plasma of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and thromboembolic stroke patients21,22,23. The protocols presented here are optimized for assessing fibrin-clot formation in a reproducible and rapid manner.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of fibrin clot analysis by turbidity assay and SEM.

The schematic shows the steps involved in fibrin clot analysis and the effect of Aβ on fibrin clot turbidity and structural topography. The scale bars of SEM images (bottom left) are 2 μm and the magnification is 10,000X.

The following protocol provides the instructions for the preparation of an in vitro fibrin-clot both with and without Aβ. It also details the methods to analyze the effect of Aβ on fibrin clot formation and structure. The effectiveness of these two methods for measuring the inhibition of the Aβ-fibrinogen interaction is demonstrated using TDI-2760, a small inhibitory compound14. These methods, both individually and together, allow for rapid and straightforward analysis of in vitro fibrin clot formation.

Protocol

1. Preparation of Aβ42 and Fibrinogen for Analysis

- Prepare monomeric Aβ42 from lyophilized powder

- Warm Aβ42 powder to room temperature and spin down at 1,500 × g for 30 s.

- Add 100 μL of ice-cold hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) per 0.5 mg of Aβ42 powder and incubate for 30 min on ice. CAUTION: Use care when handling HFIP and perform all steps in a chemical hood.

- Prepare 20 μL aliquots and let the films air dry in a chemical hood for 2–3 h. Films can be stored at −20 °C.

- Reconstitute monomeric Aβ42 film in 10 μL of fresh dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) by agitation in a bath sonicator for 10 min at room temperature.

- Add 190 μL of 50 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris) buffer (pH 7.4) and pipette up and down gently.

- Remove the protein aggregates by centrifugation at 20,817 × g at 4 °C for 20 min.

- Incubate the supernatant at 4 °C for overnight and next day centrifuge the solution at 20,817 × g at 4 °C for 20 min to discard any further protein aggregates.

- Measure Aβ42 concentration by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Serial dilute purified bovine serum albumin (BSA) from 1 mg/mL to 0.0625 mg/mL to produce a protein standard, add 10 μL of each standard to the wells of a multi-well plate in triplicate. Dilute Aβ samples 1:4 and add 10 μL to the wells in triplicate. Mix BCA solutions A and B and add 200 μL to each well. Incubate for 30 min at 37 °C and read on a plate reader at 562 nm. Keep the remaining Aβ solution on ice and use this preparation for turbidity assay and SEM.

- Prepare Fibrinogen solution

- Measure 20 mg of lyophilized fibrinogen powder into a 15 mL tube and re-suspend with pre-warmed 2 mL of 20 mM hydroxyethylpiperazine ethane sulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer (pH 7.4).

- Incubate in a 37 °C water bath for 10 min.

- Filter solution through a 0.2 μm syringe filter and store at 4 °C for 30 min. Take out the solution from 4 °C and filter again through 0.1 μm syringe filter to remove fibrinogen aggregates or pre-existing fibrin.

- Measure the fibrinogen concentration by BCA assay. Follow the instructions from Step 1.1.8. Keep the remaining fibrinogen solution at 4 °C and use this preparation for turbidity assay and SEM.

2. Clot Turbidity Assay

-

To each experimental well of the 96-well plate, add 20 μL of 30 μM Aβ42 solution from Step 1.1.8 so that its final concentration is 3.0 μM in 200 μL of the buffer. Add the same volume of 5% DMSO in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) to buffer control wells in the 96-well plate.

NOTE: The exact volume of Aβ42 at this step is not important. For low concentration preparations, a higher volume can be used, and the volume of the clot formation buffer can be adjusted. The final volume should remain 200 μL.

-

If testing inhibitory compounds, dilute the compound to the working concentration as DMSO. Add compound or DMSO alone for a control to the wells with Aβ42 and mix well.

NOTE: Aβ42 solution should form a discrete droplet at the bottom of the well, the compound or DMSO should be pipetted directly into the center of the droplet.

-

Dilute the fibrinogen stock solution from Step 1.2.4 in clot formation buffer (20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4), 5 mM CaCl2, and 137 mM NaCl) and add it to Aβ42 containing and control wells of the 96-well plate. Adjust the volume of the fibrinogen solution so that its final concentration becomes 1.5 μM in total 200 μL reaction volume. Pipette the solution slowly and avoid forming bubbles. Incubate the plate at room temperature for 30 min shaking on a rotating platform.

NOTE: The volume of fibrinogen solution may vary depending on its stock concentration, but the total volume in each well should be 170 μL while incubation.

Prepare thrombin solution by dissolving commercially purified thrombin powder in ddH2O to make a stock solution of 50 U/mL. Dilute to the 5 U/mL working solution in 20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) directly before use.

-

After 30 min of incubation, simultaneously add 30 μL of thrombin solution (5 U/mL) into the fibrinogen solutions in the 96-well plate from Step 2.3 using multichannel pipette. Addition of thrombin will immediately initiate the clot formation. Therefore, add thrombin directly into the center of the fibrinogen solution with care to avoid forming bubbles.

NOTE: The activity of thrombin can vary between experimental conditions, as well as thrombin lots. The correct concentration required to robustly produce clots may have to be determined empirically.

-

Read the absorbance of in vitro clot on a plate reader immediately following the thrombin addition. Measure the absorbance at 350 nm over the course of 10 min, every 30–60 s. Perform the entire assay at room temperature.

NOTE: Some inhibitor compounds may alter the solution absorbance at 350 nm, in which case the turbidity can be measured at 405 nm.

3. Scanning Electron Microscopy

- Preparation of clot, fixation, and washing

- Place clean siliconized glass circle cover slides (12 mm) into a 12-well or 24-well plate using forceps.

- Prepare fibrinogen in clot formation buffer. See protocol step 1.2 for details.

- To evaluate the effect of Aβ-fibrinogen interaction inhibitors on fibrin clot structure, follow the instructions for incubation as described for the turbidity assay (Step 2). Always include control wells which contain fibrinogen in the absence of both Aβ and inhibitors.

- Pipette 80 μL of the fibrinogen mixture from Step 3.1.3 on the cover slides. Gently spread the solution so that it is evenly distributed on the cover slide.

-

Dilute thrombin stock (50 U/mL) into 20 mM HEPES buffered saline to a final concentration of 2.5 U/mL and add 20 μL directly to the center of to the fibrinogen solution without mixing.NOTE: If required, a higher thrombin working concentration (5 U/mL) can be used.

- Cover the 12-well plate with a plastic lid and leave it at room temperature for 30–60 min.

- While clotting reaction is running, prepare dehydration and fixation solutions. Prepare sodium cacodylate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4). Dilute 10% glutaraldehyde stock solution in sodium cacodylate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) to make a 2% working solution of glutaraldehyde. Keep all these solutions on ice. Freshly diluted glutaraldehyde (2%) should be used within 1 week, when properly stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C.

-

Dilute absolute ethanol (100%) in double distilled water (80%, 50%, and 20% ethanol). Keep these ethanol solutions and absolute ethanol (100%) on ice.CAUTION: Use care when handling sodium cacodylate and glutaraldehyde, perform these steps in a chemical hood.

- After 30 min, gently wash the clots with ice-cold sodium cacodylate buffer (0.1 M) twice. Add 2 mL of the buffer to each well such that the clot is completely submerged. Cover the well plate with a lid and leave it for 2 min at room temperature. After 2 min, gently remove the buffer using a 1 mL pipette or narrow stem transfer pipette. Repeat once.

- Fix the clots with ice-cold glutaraldehyde (2%). Keeping the well plate on ice, add around 2–3 mL of 2% glutaraldehyde to each well. Make sure the clots are completely submerged. Cover and leave the plate on ice for 30 min.

- After 30 min, gently remove the glutaraldehyde from each well and wash the clots using sodium cacodylate buffer (0.1 M) as described above (2 min, twice). Keep the well plate on ice.

- Serial dehydration of clot and critical point drying

- Dehydrate the clots in a graded series of ice-cold ethanol washes prepared in Step 3.1.8 (20%, 50%, 80%, 100%, and again100%) for 5 min each. For each ethanol series, add 2–3 mL, making sure the clots are submerged. Cover and incubate on ice.

-

After each ethanol step, remove the ethanol solution using a 1 mL pipette or disposable pipette dropper. Do not remove the ethanol completely. Make sure the clot surface is not exposed to air.NOTE: Dehydration in absolute ethanol (100%) should be performed twice.

- While keeping the sample submerged in the final 100% ethanol, transfer to a critical point dryer (CPD). Use a CPD sample holder or a cover slip holder with a washer for transferring the slides into the CPD chamber. Place at least one washer between each slide.

- Take out the cover slide from the CPD chamber and mount it on an SEM stub using carbon tape.

-

Sputter coating and imaging

Transfer all the samples with SEM stub to the sputter coating chamber.

-

Sputter coat less than 20 nm of gold/palladium or other conductive materials, such as carbon, using a vacuum sputter coater.

NOTE: We have used 18 nm of gold/palladium coating. The sputter coating was performed for 45 s and the coating speed was 4 Å/ s. Sputter coated samples are stable when kept properly in a dry environment at room temperature for few weeks. SEM analysis can be performed anytime.

-

Acquire images on a scanning electron microscope equipped with the SE2 detector at 4 kV.

NOTE: The image pixel size in this image set range from 13 nm- 31 nm.

Representative Results

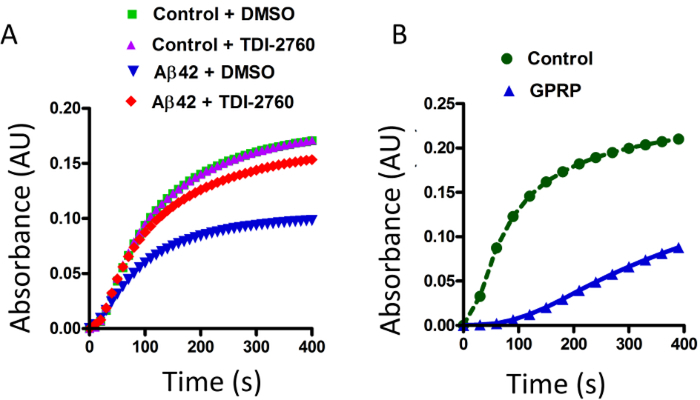

In the in vitro clotting (turbidity) assay, the enzyme thrombin cleaves fibrinogen, resulting in the formation of the fibrin network24. This fibrin clot formation causes scattering of the light passing through the solution, resulting in increased turbidity (Figure 1), plateauing before the end of the reading period (Figure 2, green). When the fibrinogen was incubated in the presence of Aβ42, the turbidity of the solution decreased, with the curve reaching a maximum height of roughly half that of fibrinogen alone (Figure 2A, blue). In a recent publication, a series of Aβ aggregation blockers were synthesized and assessed for their ability to inhibit the Aβ-fibrinogen interaction, identifying the compound TDI-276014. We have used TDI-2760 in our study to block Aβ-fibrinogen interaction. As reported previously, in the presence of TDI-2760, the effect of Aβ was ameliorated, as the turbidity was higher than with Aβ alone (Figure 2A, red). The effect of TDI-2760 does not appear to be due to background turbidity as the compound did not change the fibrin clot turbidity when Aβ was absent (Figure 2A, purple). The in vitro clotting turbidity assay described here is a rapid and simple method by which fibrin-clot formation and factors that may attenuate that process can be observed. GPRP, which is known to interfere with fibrin polymerization via interfering with fibrin monomer knob-hole interactions18,25 can be used as a positive control for the turbidity assay (Figure 2B). Consistent with the earlier reports25, with the presence of GPRP peptide, the fibrin clot turbidity was significantly reduced as compared to the fibrin clot formation with its absence (Figure 2B, blue vs green).

Figure 2: Measurement of the effect Aβ42 on in vitro fibrin clot formation by turbidity assay.

(A) Fibrinogen was incubated in the presence and absence of Aβ42. Clot formation was induced by thrombin, resulting in increased turbidity of the solution (green). In the presence of Aβ42, the fibrin clot was abnormally structured, resulting in decreased turbidity (blue). The compound TDI-2760 or DMSO were incubated with the fibrinogen solution, both with and without Aβ42. TDI-2760 restored Aβ42-induced decrease of turbidity (red) without altering the normal clot formation (purple). (B) The turbidity of a known fibrinolysis inhibitor, GPRP was also measured as a positive control for this assay. Fibrinogen was incubated in the presence and absence of 1.5 μM GPRP and the turbidity measured after adding thrombin. Similar to Aβ42, the turbidity of fibrin clot formation was significantly reduced in the presence of GPRP (blue versus green).

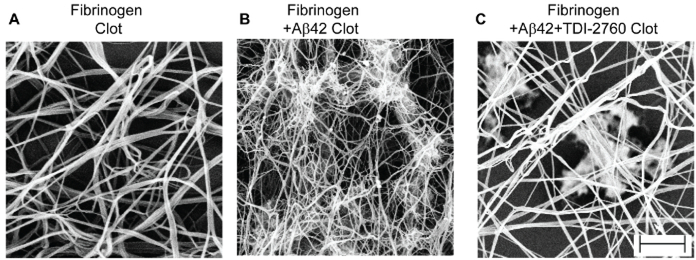

Following the same protocol and conditions as the turbidity assay described above, fibrin clots were prepared in the presence and absence of Aβ and/or TDI-2760. The clots were then processed for electron microscopy by fixation, dehydration, critical point drying, and gold-sputter coating (Figure 1). Fibrinogen in the presence of only thrombin and CaCl2 formed a fibrin mesh, with elongated and intercalated threads of fibrin as well as larger bundles (Figure 3A). When Aβ was present, the fibrin threads became thinner, with several sticky clumps/aggregates indicating Aβinduced structural abnormalities (Figure 3B). Consistent with the turbidity assay results, TDI-2760 partially restored the structure of the fibrin clot from Aβ-induced changes, as fewer clumps were present (Figure 3C). Together with the turbidity assay, SEM reveals the extent and quality of Aβ-induced changes to fibrin clot formation, as well as the effectiveness of an inhibitory compound, TDI-2760.

Figure 3: Scanning electron micrographs of Aβ-induced abnormalities to fibrin clot architecture.

Scanning electron micrographs of fibrin clot structure obtained from purified fibrinogen (A), fibrinogen + Aβ42 (B), fibrinogen + Aβ42+TDI-2760 (C). Clot formation was initiated by adding thrombin and CaCl2 to the mixture. The structural analysis revealed that clots formed in the presence of Aβ42 are thinner and abnormally clumped compared to fibrinogen by itself. TDI-2760, which is known to inhibit Aβ42-fibrinogen interaction, partially corrected the Aβ42 induced structural abnormality of the fibrin clot. Scale bar is 1 μm.

Discussion

The methods described here provide a reproducible and rapid means of assessing fibrin clot formation in vitro. Furthermore, the simplicity of the system makes the interpretation of how Aβ affects the fibrin clot formation and structure relatively straight-forward. In this lab’s previous publication, it was shown that these assays can be used to test compounds for their ability to inhibit the Aβ-fibrinogen interaction13,14. Using these two assays, a series of synthesized compounds were analyzed for the ability to inhibit the Aβ-fibrinogen interaction. Actually, the clot turbidity assay can be used to narrow the pool of hit compounds to those which have therapeutic potential, as not all compounds that can inhibit the Aβ-fibrinogen interaction can also restore fibrin clot formation.

There are a few aspects of the turbidity assay that may require troubleshooting or limit the uses of this technique. The major limitation is that there can be some variations between the experiments that may complicate the interpretation of the results. Some of this variation is to be due to the thrombin activity. To troubleshoot for thrombin activity, users can test multiple concentrations of thrombin for clot-formation activity prior to beginning experimentation with Aβ and test compounds. Under the experimental conditions presented here, Aβ, in the absence of fibrinogen, does not increase the turbidity of the solution above background levels indicating that observed turbidity curves are due to fibrin polymerization. However, Aβ is an aggregation-prone peptide and a higher concentration of Aβ solution when kept for a very long time at room temperature or 37 °C (several hours) can form fibrillar aggregates which may result in increased turbidity. If analyzing the effect an Aβ solution that has been stored for long periods of time at room temperature or warmer, the aggregation status of the solution can be determined by transmission electron microscopy. In the protocol described here, freshly prepared Aβ and fibrinogen solutions are used, which should eliminate aggregation issues. However, to ensure the quality of these preparations they have been assessed by transmission electron microscopy. Additionally, when using a new lot of commercial Aβ peptide, the extent of oligomerization and quantity of oligomers should be assessed by transmission electron microscopy. Because there might be lot to lot variation in peptide quality and ratio of preformed aggregates and monomeric Aβ, which certainly affects the oligomerization rate. It is advisable to check the concentration of Aβ solution (BCA method) before incubating for oligomerization. To minimize these variations, we tried using at least 0.1 mg/mL of Aβ solution for oligomer formation reaction.

Because this assay is also sensitive to small environmental changes such as temperature and motion, turbidity readings from different experiments should not be analyzed together. This means that the number of conditions that can be compared is limited by the number of wells that thrombin can be simultaneously added to with a multichannel pipette (i.e., 12). Users should also be aware that viscosity or color in the buffers and test compounds can lead to a high background turbidity, obscuring the signal from the fibrin clot and making interpretation of the experiment difficult. However, if all of the controls are included in each experiment, it should be possible to readily determine if background signal is altering the turbidity absorbance.

The turbidity assay provides information about whether formation of the fibrin clot is hindered by Aβ and furthermore if inhibitor compounds can alleviate this effect. However, it does not reveal how the structure of the fibrin clot is altered in response to Aβ and/or hit compounds. This question can be addressed by SEM, as this allows for direct visualization of the clot architecture. SEM is a well-established technique and is routinely used for visualizing clot structure from purified fibrinogen or from plasma. However, the traditional clot preparation process for SEM analysis can be complicated and time-consuming. Furthermore, small differences in protocols between different research groups can make it challenging to replicate results24. To address these issues this optimized protocol was developed, with which the effect of Aβ to induce thinner fibrin strands and clumps of protein can be observed (Figure 3). As seen with the turbidity assay, TDI-2760 alleviates the effect of Aβ, restoring the typical structure of fibrin bundles (Figure 3).

There are a few steps in the SEM sample preparation, which may also require troubleshooting. When using very low concentrations of fibrinogen (0.5 μM or less), the clots may not be firmly attached to the glass slide and can be damaged/washed away during the fixation/washing steps. If using low concentrations of fibrinogen, the clot formation time, between the addition of thrombin and fixation, can be increased up to several hours, as this may increase the clot stability. Also, users should avoid using high strength phosphate buffer or phosphate buffered saline for both the turbidity and SEM assays, as phosphate ions may interfere with calcium-mediated clot formation process. If using any other high salt containing buffer for clot formation and SEM analysis, after fixation, washing steps should also be performed with cold ddH2O.

SEM analysis of non-conductive samples such as fibrin clots requires coating with charged particles such as, gold, palladium, silver or carbon. Coating thickness is an important factor in SEM imaging, as it is possible that a very thick metal coating can mask the ultra-structure surface topography of the fibrin clot. In this protocol, thin gold/palladium coating (less than 20 nm) are used for sputter coating. To achieve less than 20 nm thickness, the sputtering was done for 45 s with a coating rate of 4 Å/s. This thin coating (18 nm) does not appear to mask the surface features of fibrin assembly. However, if concerned about masking the ultra-structure of the clot, carbon coating can be used as an alternative to gold/palladium, as it will leave less “islets” of coating molecules on the material.

While the focus here has been on the Aβ-fibrinogen interaction, this protocol can be readily modified to analyze the interaction of other proteins or compounds with the fibrin clot. Following these instructions, investigators should be able to reproduce in vitro fibrin clot formation and perform analysis with these streamlined clot-turbidity assay and SEM protocols. As shown here with the previously published inhibitor compound TDI-2760, these methods provide valuable information regarding fibrin clot formation that can be applied to further studies both in vitro and in vivo.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Masanori Kawasaki, Kazuyoshi Aso, and Michael Foley from Tri-Institutional Therapeutics Discovery Institute (TDI), New York for synthesis of Aβ-fibrinogen interaction inhibitors and their valuable suggestions. Authors also thank members of the Strickland lab for helpful discussion. This work was supported by NIH grant NS104386, the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, and Robertson Therapeutic Development Fund for H.A., NIH grant NS50537, the Tri-Institutional Therapeutics Discovery Institute, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, Rudin Family Foundation, and John A. Herrmann for S.S.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Video Link

The video component of this article can be found at https://www.jove.com/video/58475/

References

- 1.Selkoe DJ, & Schenk D Alzheimer’s disease: molecular understanding predicts amyloid-based therapeutics. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 43 545–584, (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurz A, & Perneczky R Amyloid clearance as a treatment target against Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 24 Suppl 2 61–73, (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benilova I, Karran E, & De Strooper B The toxic Abeta oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: an emperor in need of clothes. Nature Neuroscience. 15 (3), 349–357, (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karran E, & Hardy J A critique of the drug discovery and phase 3 clinical programs targeting the amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer disease. Annals of Neurology. 76 (2), 185–205, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshikawa T et al. Heterogeneity of cerebral blood flow in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. AJNR, American Journal of Neuroradiology. 24 (7), 1341–1347, (2003). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strickland S Blood will out: vascular contributions to Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 128 (2), 556–563, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn HJ et al. Alzheimer’s disease peptide beta-amyloid interacts with fibrinogen and induces its oligomerization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (50), 21812–21817, (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zamolodchikov D et al. Biochemical and structural analysis of the interaction between beta-amyloid and fibrinogen. Blood. 128 (8), 1144–1151, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortes-Canteli M et al. Fibrinogen and beta-amyloid association alters thrombosis and fibrinolysis: a possible contributing factor to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 66 (5), 695–709, (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cortes-Canteli M, Mattei L, Richards AT, Norris EH, & Strickland S Fibrin deposited in the Alzheimer’s disease brain promotes neuronal degeneration. Neurobiology of Aging. 36 (2), 608–617, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liao L et al. Proteomic characterization of postmortem amyloid plaques isolated by laser capture microdissection. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (35), 37061–37068, (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zamolodchikov D, & Strickland S Abeta delays fibrin clot lysis by altering fibrin structure and attenuating plasminogen binding to fibrin. Blood. 119 (14), 3342–3351, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahn HJ et al. A novel Abeta-fibrinogen interaction inhibitor rescues altered thrombosis and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease mice. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 211 (6), 1049–1062, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh PK et al. Aminopyrimidine Class Aggregation Inhibitor Effectively Blocks Abeta-Fibrinogen Interaction and Abeta-Induced Contact System Activation. Biochemistry. 57 (8), 1399–1409, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pretorius E, Mbotwe S, Bester J, Robinson CJ, & Kell DB Acute induction of anomalous and amyloidogenic blood clotting by molecular amplification of highly substoichiometric levels of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 13 (122), (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veklich Y, Francis CW, White J, & Weisel JW Structural studies of fibrinolysis by electron microscopy. Blood. 92 (12), 4721–4729, (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weisel JW, & Nagaswami C Computer modeling of fibrin polymerization kinetics correlated with electron microscope and turbidity observations: clot structure and assembly are kinetically controlled. Biophysical Journal. 63 (1), 111–128, (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chernysh IN, Nagaswami C, Purohit PK, & Weisel JW Fibrin clots are equilibrium polymers that can be remodeled without proteolytic digestion. Scientific Reports. 2 879, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klunk WE, Jacob RF, & Mason RP Quantifying amyloid beta-peptide (Abeta) aggregation using the Congo red-Abeta (CR-abeta) spectrophotometric assay. Analytical Biochemistry. 266 (1), 66–76, (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao R et al. Measurement of amyloid formation by turbidity assay-seeing through the cloud. Biophysical Reviews. 8 (4), 445–471, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bester J, Soma P, Kell DB, & Pretorius E Viscoelastic and ultrastructural characteristics of whole blood and plasma in Alzheimer-type dementia, and the possible role of bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS). Oncotarget. 6 (34), 35284–35303, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pretorius E, Page MJ, Mbotwe S, & Kell DB Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP) can reverse the amyloid state of fibrin seen or induced in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 13 (3), e0192121, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kell DB, & Pretorius E Proteins behaving badly. Substoichiometric molecular control and amplification of the initiation and nature of amyloid fibril formation: lessons from and for blood clotting. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 123 16–41, (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolberg AS, & Campbell RA Thrombin generation, fibrin clot formation and hemostasis. Transfusion and Apheresis Science. 38 (1), 15–23, (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soon AS, Lee CS, & Barker TH Modulation of fibrin matrix properties via knob:hole affinity interactions using peptide-PEG conjugates. Biomaterials. 32 (19), 4406–4414, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]