Abstract

Aims:

We performed an analysis of maltotriose utilization by 52 Saccharomyces yeast strains able to ferment maltose efficiently and correlated the observed phenotypes with differences in the copy number of genes possibly involved in maltotriose utilization by yeast cells.

Methods and Results:

The analysis of maltose and maltotriose utilization by laboratory and industrial strains of the species Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces pastorianus (a natural S. cerevisiae/Saccharomyces bayanus hybrid) was carried out using microscale liquid cultivation, as well as in aerobic batch cultures. All strains utilize maltose efficiently as a carbon source, but three different phenotypes were observed for maltotriose utilization: efficient growth, slow/delayed growth and no growth. Through microarray karyotyping and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis blots, we analysed the copy number and localization of several maltose-related genes in selected S. cerevisiae strains. While most strains lacked the MPH2 and MPH3 transporter genes, almost all strains analysed had the AGT1 gene and increased copy number of MALx1 permeases.

Conclusions:

Our results showed that S. pastorianus yeast strains utilized maltotriose more efficiently than S. cerevisiae strains and highlighted the importance of the AGT1 gene for efficient maltotriose utilization by S. cerevisiae yeasts.

Significance and Impact of the Study:

Our results revealed new maltotriose utilization phenotypes, contributing to a better understanding of the metabolism of this carbon source for improved fermentation by Saccharomyces yeasts.

Keywords: AGT1, gene copy number variation, MAL genes, maltotriose, Saccharomyces

Introduction

Saccharomyces yeast strains have been used by humans for millennia for brewing, baking and the production of wine and diverse distilled beverages. The yeast species Saccharomyces cerevisiae is considered the predominant agent present in these fermentations, but other species of the Saccharomyces sensu stricto complex (such as Saccharomyces bayanus and Saccharomyces paradoxus) have also been isolated from these industrial processes. Hybrid strains between species in the Saccharomyces complex have also been described in wine and beer fermentations, and strains of Saccharomyces pastorianus, a natural hybrid yeast between S. cerevisiae and S. bayanus, are traditionally used to brew lager beers (Querol and Bond 2009).

Many of the industrial applications of Saccharomyces yeasts rely on the efficient fermentation of starch hydrolysates rich in the α-glucosides maltose and maltotriose. In the brewing industry, for example, these two sugars are of special importance as they are the predominant sugars in wort (typically 50–60% is maltose, 15–20% is maltotriose), followed by glucose (10–15%) and other minor carbohydrates. Of these sugars, glucose is preferentially and rapidly utilized by yeast cells, but both process efficiency and product quality require the complete fermentation of all sugars, including maltose and maltotriose. Although maltose is easily fermented by the majority of yeast strains after glucose exhaustion, maltotriose is not only the least preferred sugar for uptake by these Saccharomyces cells, but many yeasts may not use this α-gluco-side at all (Zheng et al. 1994b; Yoon et al. 2003). Slow and incomplete yeast sugar fermentation represents a significant economic loss for these industries, and consequently most strain development programmes aim to select yeasts with improved fermentation performance.

Utilization of these α-glucosides requires the active transport of the sugar across the plasma membrane by maltose permeases and its subsequent hydrolysis by cytoplasmic α-glucosidases (maltases). The genetic and biochemical analysis of maltose fermentation by yeast cells revealed a series of five unlinked telomere-associated multi-gene MAL loci: MAL1 (chromosome VII), MAL2 (chromosome III), MAL3 (chromosome II), MAL4 (chromosome XI) and MAL6 (chromosome VIII). Each locus contains at least one copy of three different genes encoding a maltose permease (MALx1, where x stands for one of the five loci, e.g. MAL11 is the permease at the MAL1 locus on chromosome VII), a maltase (MALx2) and a positive regulatory protein (MALx3) that induces the transcription of the two previous genes in the presence of maltose (Novak et al. 2004). The genes in the MAL loci show a high degree of sequence and functional similarity, but there can be extensive variability, and several different alleles that determine distinct phenotypes (i.e. MAL-inducible and MAL-constitutive strains) have been described. The MAL1 locus is considered the progenitor locus from where all other MAL loci were derived, as all S. cerevisiae strains, and even its closest related yeast species S. paradoxus, contain MAL1 sequences near the right telomere of chromosome VII. This holds true even for many maltose nonfermenting strains, which may harbour partially functional mal1p (mal11 mal12 MAL13), mal1g (MAL11 MAL12 mal13) or mal10 (mal11 MAL12 mal13) loci containing only a functional regulator, only a functional permease and maltase or only a functional maltase, respectively (Charron and Michels 1988; Naumov et al. 1994). Indeed, the genome sequence of strain S288C, a maltose-negative laboratory strain, contains a mal1g and a mal3g loci (each containing only a functional permease and maltase, but nonfunctional regulatory genes) and two other maltose permease genes, MPH2 and MPH3, located at the telomeres of chromosome IV and X, respectively (Feuermann et al. 1995; Volckaert et al. 1997; Day et al. 2002a).

All α-glucoside transport systems so far characterized in yeast are H+-symporters that use the electrochemical proton gradient to actively transport these sugars into the cell, even for downhill transport of the sugar (Crumplen et al. 1996; Stambuk and de Araujo 2001). Maltose transport into the cell is required for full induction of MAL genes, and several reports have shown that maltose uptake is also the rate-limiting step for fermentation (Kodama et al. 1995; Wang et al. 2002; Rautio and Londesborough 2003). Maltose transport has thus been extensively studied in both laboratory and industrial yeast strains, revealing complex kinetics that indicate the presence of high- and low-affinity transporters (Crumplen et al. 1996; Zastrow et al. 2001; Rautio and Londesborough 2003). At least three different maltose transporters have been identified in S. cerevisiae cells, and while the MALx1 transporters (and probably the two MPH2 and MPH3 alleles) encode high-affinity (Km 2–4 mmol l−1) maltose permeases, the AGT1 permease (a gene present in partially functional mal1g loci) transports maltose with lower (Km c. 20 mmol l−1) affinity (Han et al. 1995; Stambuk and de Araujo 2001; Day et al. 2002a; Alves et al. 2007, 2008).

Significantly less well-characterized than maltose transport, maltotriose uptake by yeast cells also shows complex kinetics indicating the presence of high- and low-affinity transport activities, and studies on sugar utilization by yeast cells also revealed that maltose and maltotriose are apparently transported by different permeases (Zheng et al. 1994a; Zastrow et al. 2001). Two known permease genes have been described as transporting maltotriose in yeasts, the S. cerevisiae AGT1 transporter and the S. pastorianus MTY1 (also known as MTT1) permease, both having relatively low affinity (Km c. 20 mmol l−1) for maltotriose (Stambuk and de Araujo 2001; Salema-Oom et al. 2005; Dietvorst et al. 2005; Alves et al. 2007, 2008).

However, there have been other reports regarding the observed patterns of maltose and maltotriose utilization by yeast cells that contradict the results described earlier. Some years ago, Day and co-workers presented data indicating that all known α-glucoside transporters present in S. cerevisiae, including the maltose permeases MAL31, MAL61, MPH2 and MHP3, allowed growth of the yeast cells on both maltose and maltotriose (Day et al. 2002a,b). Furthermore, their kinetic analysis of maltose and maltotriose uptake by the cells indicated that all these transporters, including the AGT1 permease, could transport both sugars with practically the same affinities and capacity. Thus, aiming to better understand maltotriose utilization by yeast strains, we performed an analysis of maltose and maltotriose utilization by 52 laboratory and industrial Saccharomyces yeast strains; we then used microarray comparative genome hybridization (aCGH), to correlate the observed phenotypes with copy number variations (CNVs) in genes known to be involved in maltose and maltotriose utilization by yeasts.

Materials and methods

Strains, media and growth conditions

The Saccharomyces strains analysed in the present study are described in Tables 1 and 2. The AGT1 gene was deleted from the genome of yeast strains according to a previously described PCR-based gene replacement procedure (Batista et al. 2004; Alves et al. 2008). Rich YP medium (1% yeast extract and 2% Bacto peptone) was supplemented with 2% of the indicated carbon source (maltose or maltotriose), and the pH of the medium was adjusted to pH 5·0 with HCl. Yeast cells were pregrown overnight in 3 ml of YP-2% maltose, and 1 : 100 dilutions of these precultures were used to inoculate 100 μl of rich YP medium containing the indicated sugars in 96-well plates in a Tecan GENios microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland), to determine the growth at 30°C. All wells in the plate were tightly sealed with Accu-Clear Sealing Film for qPCR (E&K Scientific, Santa Clara, CA), and growth of each culture was monitored by measuring the OD600 every 15 min, with high intensity orbital shaking between measurements. All growth curves were performed in duplicate, and controls in rich YP medium without a carbon source were included; the no-carbon curves were subtracted from the growth curves obtained in the presence of the sugar to yield normalized growth curves. All growth experiments were repeated at least twice, and we observed that differences between strains were highly reproducible. Alternatively, cells were batch grown (160 rev min−1, 30°C) in cotton-plugged Erlenmeyer flasks filled to 1/5 of the volume with medium, and culture samples were harvested regularly, centrifuged (5000 g, 1 min), and their supernatants used for the determination of sugars and ethanol as described in the following.

Table 1.

Laboratory Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts analysed

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| S288C | MATα mal13 AGT1 MAL12 mal33 MAL31 MAL32 mel gal2 flo1 flo8–1 hap1 ho bio1 bio6 SUC2 | Mortimer and Johnston (1986) |

| RM11–1a | MATa mal13 agt1 MAL12 MAL3 leu2Δ ura3Δ ho::Kan | Brem et al. (2002) |

| VJM789 | MATa MAL1 MAL3 ho::hisG Iys2 gal2 | Wei et al. (2007) |

| CMY001 | MATa mal11::MAL61/HA MAL12 MAL13 GAL ura3–52 Ieu2his3–200 trp1-Δ63 Iys2–801 ade2–101 | Wang et al. (2002) |

| CEN.PK2–1C | MATa MAL2–8C MAL3 mal13 AGT1 MAL12 SUC2 ura3–52 his3Δ1 leu2–3, 112 trp 1–289 | Alves et al.(2008) |

| LCM003 | agt1Δ::kanMX6 derivative of CEN.PK2–1C | Alves et al. (2008) |

| 1403–7A | MATa MAL4C mal33 MAL31 MAL32 mal13 AGT1 MAL12 MAL21 MGL3 gal3 gal4 trp1 ura3 suc− | Alves et al. (2008) |

| LCM001 | agt1A::kanMX6 derivative of 1403–7A | Alves et al. (2008) |

| Y55 | MATα/MATa HO/HO gal3/gal3 MAL1/MAL1 SUC1/SUC1 | Houghton-Larsen and Brandt (2006) |

Table 2.

Other Saccharomyces yeasts analysed

| Strain | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Saccharomyces bayanus var. uvarum | ||

| CBS7001 | Dunn and Sherlock (2008) | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae industrial strains | ||

| GSY2; UCD522 | Montrachet wine yeasts | Dunn et al. (2005) |

| UCD819 | Prise de Mousse wine yeast | Dunn et al. (2005) |

| GSY924 | Leinenkugel Ale Brewing yeast | Dunn and Sherlock (2008) |

| LBCC-A3 | Ale Brewing yeast | Batistote et al. (2006) |

| G11; G13; G14; G15; G30; G34; G35 | Baker’s yeasts | -* |

| CAT-1; SA-1; PE-2; VR-1 | Fuel ethanol yeasts | Basso et al. (2008) |

| GDB-178; GDB-379 | Fuel ethanol yeasts | da Silva-Filho et al. (2005) |

| UFMG-A905; UFMG-A1007 | Cachaça production yeasts | Gomes et al. (2007) |

|

Saccharomyces pastorianus industrial strains DBVPG6033; DBVPG6047; DBVPG6257; DBVPG6258; DBVPG6261; DBVPG6282; DBVPG6283; DBVPG6284; DBVPG6285; DBVPG6560 |

Lager Brewing yeasts | Dunn and Sherlock (2008) |

| CBS1174; CBS1483; CBS1484; CBS2156; CBS2440; CBS6903 | Lager Brewing yeasts | Dunn and Sherlock (2008) |

| LBCC-L52 | Lager Brewing yeasts | Batistote et al. (2006) |

| WY2124 | Bohemian Lager Brewing yeast | -† |

| WY2206 | Bavarian Lager Brewing yeast | -† |

| W-34/70 | Weihenstephan Lager Brewing yeast | Nakao et al. (2009) |

| Other S. cerevisiae × S. bayanus hybrid strains | ||

| Y251 | Wine yeast | -‡ |

| Y165 | Cider yeast | -‡ |

| CLIB180 | S. pastorianus (monacensis) distiller’s yeast | dos Santos et al. (2007) |

Strains provided by M. Ettayebi, University Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdallah, Fez, Morocco.

Strains kindly provided by B. Maca, Miller Brewing Co., Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Strains provided by J. Piskur, Department of Microbiology, Technical University of Denmark.

Microarray karyotyping

The microarray karyotyping analysis of the industrial yeast strains was performed essentially as described previously (Dunn et al. 2005). We used microarrays onto which had been spotted PCR products corresponding to full-length ORFs from the S288C strain of S. cerevisiae (DeRisi et al. 1997), and thus the reference DNA used in all hybridizations was isolated from this strain. Genomic DNA was isolated with YeaStar columns (Zymo Research, Orange, CA) and then cut with HaeIII (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Approximately, 1 mg of this DNA was labelled with fluorescently tagged nucleotides (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA), usually Cy3-dUTP for the reference strain (thus giving a green signal for every spot) and Cy-5 dUTP for the industrial strains, using the BioPrime random-prime labelling system (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD). After labelling, the reactions were heat-inactivated, the experimental (Cy5-labelled) and reference (Cy3-labelled) DNAs were mixed, purified away from unincorporated label using Zymo Clean&Concentrate columns (Zymo Research) and then hybridized to the microarrays at 65°C as described (Dunn et al. 2005). Arrays were scanned with an Axon 4000A scanner, and the data were extracted using GenePix (Molecular Devices Corp., Union City, CA, USA) software. The array data were treated and analysed as described previously (Dunn et al. 2005; Stambuk et al. 2009); note that all arrays contained duplicated spots for each gene, and all data presented are the average of the values from the duplicate spots. As all array data were normalized by setting the average log fluorescence hybridization ratio of all array elements to a value of zero, differences in hybridization intensity because of ploidy differences are eliminated. Therefore, even if the industrial strains are of diploid or higher ploidy, the normalization process allows direct comparison to the haploid reference strain so that relative CNVs of a given gene within a strain, as determined by the red:green (R/G) hybridization ratio, will be relative to its haploid genome.

PFGE, chromosome blotting and hybridization

Yeast chromosomes were prepared as previously described (Guerring et al. 1991), and the pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) performed in 1% agarose gels in 50 mmol l−1 Tris, 50 mmol l−1 boric acid, 1 mmol l−1 EDTA, pH 8·3, at 10°C using a Gene Navigator pulsed-field system (Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, UK) for a total of 27 h at 200 V. The pulse time was stepped from 70 s after 15 h to 120 s for 12 h. The chromosomes separated by PFGE were transferred to a nylon membrane (Ausubel et al. 1995), and prehybridization, hybridization, stringency washes and chemiluminescent signal generation and detection were performed using an AlkPhos kit (GE Healthcare/Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK). Probes corresponding to nucleotides +1 through +1848 of the AGT1 ORF, or −73 through +1845 of the MAL31 gene, were generated by PCR using primers AGT1-F (AG GAGCTCATGAAAAATATCATTTCATTGG) and AGT1-R (TTGGATCCACATTTATCAGCT GC), and MAL31-F (CCATACTTGTTGTGAGTGG) and MAL31-R (TCATT TGTTCACAACAGATG), respectively, and genomic DNA from strain CEN.PK2–1C as the template.

Sugar and ethanol quantification

Maltose and maltotriose were determined spectrophotometrically at 540 nm with methylamine in 0·25 mol l−1 NaOH, while the ethanol produced by the yeast cells was assessed with alcohol oxidase and peroxidase, as previously described (Alves et al. 2007, 2008).

Results

Analysis of maltose and maltotriose utilization by Saccharomyces strains

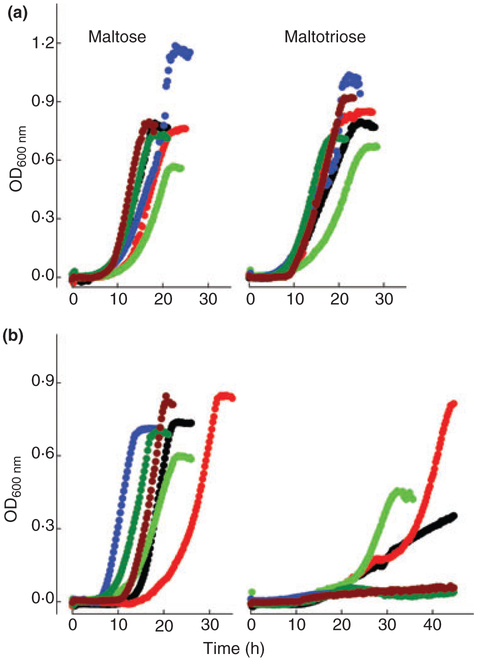

To analyse the maltose and maltotriose utilization patterns of a fairly large number of laboratory and industrial yeast strains, while also taking into account the high price of maltotriose, we decided to use 96-well microplates and a Tecan GENios reader to obtain growth curves for the 53 different yeast strains described in Tables 1 and 2. These yeast strains included nine laboratory and 20 industrial S. cerevisiae strains, as well as one S. bayanus and three S. cerevisiae × S. bayanus hybrids, and 20 lager brewing strains of the species S. pastorianus. All the strains analysed utilized maltose efficiently, reaching the stationary phase of growth with this carbon source after 15–30 h of incubation, although the rate of growth and the maximal OD reached varied to different extents depending on the strain analysed (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Growth on rich YP medium containing 2% maltose (left panel) or maltotriose (right panel) by representative yeast strains (a) belonging to Group 1 (G1), or (b) belonging to Group 2 (G2) and Group 3 (G3). G1: ( ) 1403–7A; (

) 1403–7A; ( ) CBS1513; (

) CBS1513; ( ) CBS1260; (

) CBS1260; ( ) DBVPG6283; (

) DBVPG6283; ( ) WY2124 and (

) WY2124 and ( ) CLIB180; G2: (

) CLIB180; G2: ( ) LCM001; (

) LCM001; ( ) SA-1 and (

) SA-1 and ( ) CBS1503; G3: (

) CBS1503; G3: ( ) LCM003; (

) LCM003; ( ) CBS1486 and (

) CBS1486 and ( ) GDB-379.

) GDB-379.

However, three different patterns of growth during maltotriose utilization by these same yeast cells were observed. The 27 strains belonging to Group 1 – cells that efficiently used both maltose and maltotriose as carbon sources for growth (Fig. 1a) – included only nine of the 29 S. cerevisiae strains (two laboratory, six baker’s and one ale brewing yeast strain), but included the majority (17 out of 20) of the S. pastorianus lager brewing yeasts and also the S. pastorianus (monacensis) distiller’s yeast (Table 3). All these strains reached the stationary phase of growth in 15–30 h of incubation in the presence of maltotriose, and the analysis of ethanol production by several strains belonging to this Group 1 revealed efficient maltose and maltotriose fermentation, with ethanol concentrations reaching 5–7 g l−1 at the moment of sugar exhaustion from the medium (data not shown).

Table 3.

Patterns of maltose and maltotriose utilization by the Saccharomyces yeast strains*

| Group 1 | Efficient maltose and maltotriose utilization |

| Strains | 1403–7A; CEN.PK2–1C; G11; G13; G14; G15; G30; G35; GSY924;CBS1174; CBS1483; CBS1484; CBS2156; CBS6903; CLIB180; DBVPG6033; DBVPG6047; DBVPG6257; DBVPG6282; DBVPG6283; DBVPG6284; DBVPG6285; DBVPG6560; LBCC-L52; W-34/70; WY2124, WY2206 |

| Group 2 | Efficient maltose utilization, and slow/delayed maltotriose utilization |

| Strains | CAT-1; G34; LBCC-A3; LCM001; PE-2; SA-1; UCD522; UCD819; VR-1; CBS2440; DBVPG6258; DBVPG6261 |

| Group 3 | Efficient maltose utilization, no maltotriose utilization |

| Strains | CMY001; G5Y2; GDB-178; GDB-379; LCM003; RM11–1a; Y55; YJM789; UFMG-A905; UFMG-A1007; CBS7001; Y251; Y165 |

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains are in italics.

The yeast strains belonging to Group 2 (12 strains, see Table 3) had a very different pattern of maltotriose utilization when compared to the strains in Group 1 (Fig. 1b). These yeasts utilized and fermented maltose efficiently, but when cultivated in the presence of maltotriose a very slow growth rate was observed; in some cases, the growth rate improved only after several days of incubation in this carbon source. The majority of strains belonging to this group were industrial S. cerevisiae strains (only one, LCM001, was a laboratory strain), as well as three S. pastorianus brewing strains. Finally, the remaining yeast strains (a total of 13 strains, including the eight remaining S. cerevisiae laboratory strains) belonged to Group 3 (see Table 3) and were characterized by their complete inability to grow on maltotriose (see Fig. 1b), while maltose fermentation and utilization by these cells was normal. Within this group was also the S. bayanus var. uvarum CBS7001 yeast strain as well as two S. cerevisiae × S. bayanus hybrid strains used for wine and cider production.

Microarray karyotyping of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains

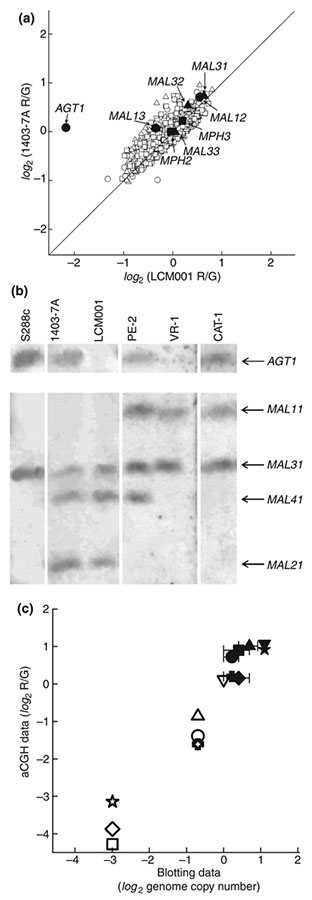

We hypothesized that gene CNVs between the yeast strains may account for some of the differences in observed maltotriose utilization and fermentation efficiency, and thus we performed aCGH on each of the strains to determine whether there were observable CNVs. As microarray karyotyping detects changes in DNA copy number relative to a reference genome (in this case the genome of laboratory strain S288C), gene duplications or deletions that result in CNV can be easily detected. As shown in Fig. 2a, the aCGH results can easily detect the presence of a deleted AGT1 gene in the genome of strain LCM001, but not in the otherwise isogenic wild-type strain 1403–7A from which it derives, while the same data indicate that these two strains have amplifications relative to S288C of both the MALx1 and MALx2 genes (known from previous work to be represented by the MAL31 maltose permease, and the MAL12 and MAL32 maltases present in the genome of strain S228C, see Feuermann et al. 1995 and Volckaert et al. 1997).

Figure 2.

Correlation between the microarray karyotyping of the laboratory strain 1403–7A and its isogenic Δagt1 strain LCM001 (a). The microarray comparative genome hybridization (aCGH) data (in log2 of the R/G ratio) for the MAL genes analysed are highlighted. Chromosomal blotting (b) of the indicated yeast strains with the AGT1 gene (upper panel) or MAL31 gene (lower panel) as probe, and (c) correlation of copy number variation of the AGT1 (open symbols) and MALx1 (black symbols) genes, as determined by aCGH (expressed as log2 of the R/G ratio) and chromosomal blotting (log2 of gene copy number per diploid genome), present in strains CAT-1 (circles), PE-2 (triangles), VR-1 (diamonds), SA-1 (squares), 1403–7A (inverted triangles), LCM001 (stars) and UFMG-1007 (crosses). For the chromosomal blotting, an arbitrary value of <0·05 was assumed for strains lacking the AGT1 gene.

Chromosome blotting and hybridization with MAL31 and AGT1 probes revealed indeed the presence of several (MAL21, MAL31 and MAL41) maltose permease genes in the chromosomes of these two (1403–7A and LCM001) strains, while, as expected, only strain LCM001 lacked the AGT1 permease (Fig. 2b). Most of the S. cerevisiae strains analysed also contained several maltose permease genes. For example, strains VR-1 and SA-1 had maltose perm-eases on both chromosomes VII (MAL11) and chromo-some II (MAL31), while strains CAT-1 and UFMG-A1007 also had these two maltose transporters genes but were heterozygous for chromosome VII, having both the AGT1 and MAL11 permease genes in each of the two chromosomes of these diploid yeast strains (see data for strain VR-1 and CAT-1 in Fig. 2b). Strain PE-2 was similar to strains CAT-1 and UFMG-A1007 (AGT1/MAL11 and MAL31), but also contained the MAL41 permease (chromosome XI) in its genome (Fig. 2b). Indeed, a good correlation was observed between gene CNV of these α-glucoside transporters present in the genome of the yeast strains, as revealed by chromosomal blotting, and the aCGH data for the corresponding AGT1 and MAL31 genes (Fig. 2c).

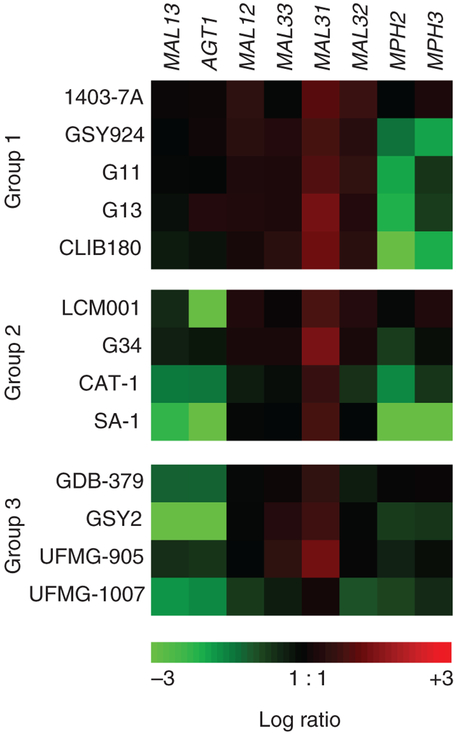

The aCGH data of MAL genes present among selected S. cerevisiae yeast strains shown in Fig. 3 indicates that the copy number of MPH2-MPH3 genes probably has little influence on maltotriose (and maltose) utilization by the S. cerevisiae yeasts analysed, as strains lacking these two genes were found among all three groups of strains with differing maltotriose utilization profiles described previously. Regarding the MALx1 transporters, practically all strains analysed in Fig. 3 showed increased copy number of this gene relative to S288C, indicating that more than one functional MAL locus is present in these strains, allowing efficient maltose utilization.

Figure 3.

Microarray karyotyping data of relative gene copy number variation (compared to strain S288C) present in the genomes of selected yeast strains from Group 1 (G1), Group 2 (G2) or Group 3 (G3).

The CGH results revealed a very different pattern regarding the AGT1 permease (Fig. 3). All the efficient maltotriose utilization strains (Group 1) analysed by microarray karyotyping have this gene in their genome, while most of the strains belonging to either Group 2 (slow/delayed maltotriose utilization) or Group 3 (no maltotriose utilization) had a lower copy number (just one gene per diploid genome), or even lacked the AGT1 gene (Fig. 3, see also Fig. 2c). Finally, although our microarrays were designed to determine gene CNVs in S. cerevisiae genomes, Fig. 3 also shows the S. cerevisiae-related aCGH data for an interspecific hybrid between this species and S. bayanus (strain CLIB180). As can be seen for this strain, which belongs to Group 1, the aCGH results indicate the presence of the AGT1 permease and amplification of the MALx1 genes, similar to what is seen in the S. cerevisiae Group 1 strains.

New maltotriose utilization phenotypes in Saccharomyces yeasts

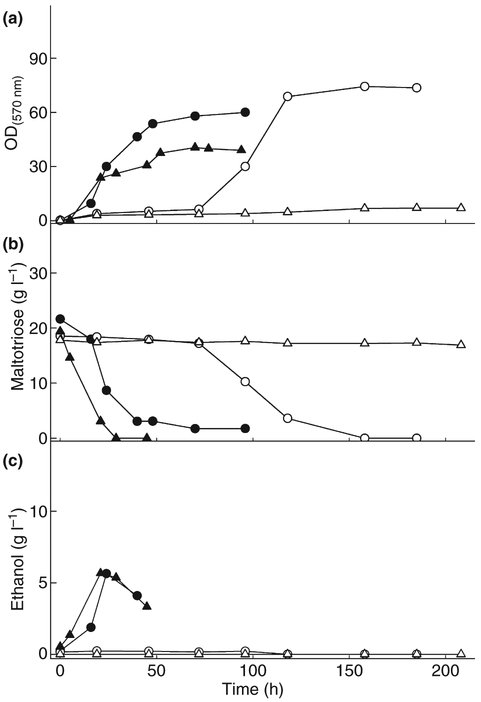

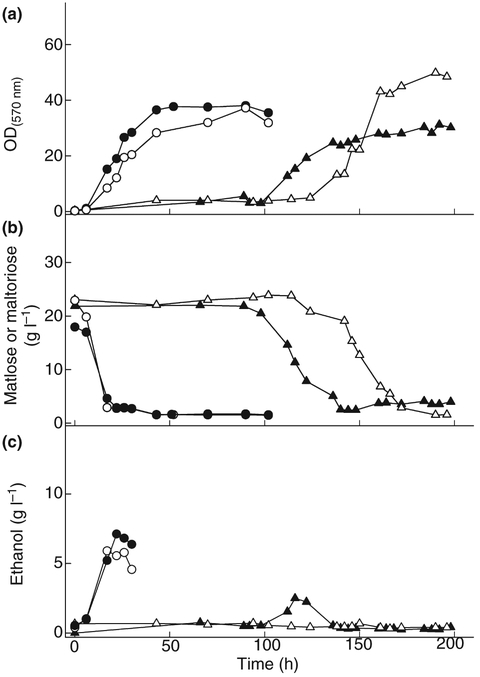

The results shown in Fig. 1 regarding the slow/delayed maltotriose utilization (Group 2) pattern observed for some yeast strains were quite unexpected and prompted us to perform a more detailed analysis of these new phenotypes. Figure 4 shows the patterns of maltotriose utilization by two laboratory S. cerevisiae strains (CEN.PK2–1C and 1403–7A) and their corresponding agt1Δ isogenic yeast strains (LCM003 and LCM001, respectively). As we have already reported for strain LCM003 (Alves et al. 2008), these agt1Δ cells are completely unable to utilize maltotriose, even after an extensive (>8 days) incubation in the presence of this carbon source. However, and in accordance with the growth assays shown in Fig. 1, strain LCM001 (also agt1Δ) had an unexpected different phenotype: it did not grow on maltotriose during the first 3–4 days of incubation, but after this extensive lag phase the cells started to consume the sugar, allowing efficient aerobic growth on maltotriose (note, though, that no ethanol was produced during sugar consumption, see Fig. 4c). This extensive lag phase phenotype was always reproducible and takes place even if cells growing exponentially in maltotriose (for example after 100 h of incubation in this carbon source) are diluted back into new YP-2% maltotriose medium; this shows that the lag phase phenotype is not merely because of selection of new maltotriose fermentative yeast mutants (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Typical cell growth (a), sugar consumption (b) and ethanol production (c) during growth on maltotriose by cells of the laboratory strains CEN.PK2–1C (black triangles) and its isogenic Δagt1 strain LCM003 (open triangles), or by strain 1403–7A (black circles) and its isogenic Δagt1 strain LCM001 (open circles).

Similar maltotriose utilization phenotypes were observed for some other S. cerevisiae industrial yeast strains belonging to Group 2. For example, cells of the industrial strain VR-1 also displayed long lag times (3–4 days) before starting to consume maltotriose for growth, and no ethanol was produced from this carbon source, although this yeast consumes and ferments maltose efficiently (Fig. 5c). Thus, this VR-1 yeast strain resembles the phenotype observed for the agt1Δ LCM001 strain shown above; indeed our aCGH and chromosomal blotting results indicate that this strain lacks the AGT1 permease in its genome (see Fig. 2b–c). However, for the remaining members of the Group 2 yeasts (the industrial fuel ethanol strains CAT-1, SA-1 and PE-2), yet another novel phenotype was observed: like LCM001 and VR-1, these strains consumed maltotriose only after an extensive lag phase, but unlike LCM001 and VR-1, they produced ethanol from maltotriose. Note that maltose consumption and fermentation was normal in the CAT-1, SA-1 and PE-2 strains. Nevertheless, in most cases, the ethanol yields on maltotriose were significantly lower than those obtained during maltose fermentation, as shown in Fig. 5c for the industrial S. cerevisiae yeast strain PE-2.

Figure 5.

Typical cell growth (a), sugar consumption (b) and ethanol production (c) during growth on maltose (circles) or maltotriose (triangles) by cells of the industrial strains PE-2 (black symbols) or VR-1 (open symbols).

Discussion

The fermentative performance of Saccharomyces yeast strains has long been recognized to differ between strains, and the extent of utilization of maltose, for example, has been shown to vary especially between industrial and laboratory yeast strains (Naumov et al. 1994; Han et al. 1995; Bell et al. 2001; Meneses and Jiranek 2002; Meneses et al. 2002). Furthermore, the difficulty that some industrial yeast strains have in consuming maltotriose leads to one of the problems experienced by many breweries, namely sluggish fermentations with a high content of fermentable sugars in the finished beer, lower ethanol yields and atypical beer flavor profiles. Previous studies with industrial ale (S. cerevisiae) and lager (S. pastorianus) brewing yeast strains showed that in general lager yeasts consume maltotriose from wort faster, and thus residual maltotriose is more common at the end of ale fermentations (Zheng et al. 1994b).

In this study, our analysis of maltotriose utilization by 52 efficient maltose-fermenting Saccharomyces yeast strains (Fig. 1) confirmed the superior performance of S. pastorianus lager brewing yeast strains for maltotriose fermentation, as the majority of the S. pastorianus strains analysed (18 in 23) utilized this carbon source efficiently; only three of the lager yeasts, and two other S. cerevisiae × S. bayanus hybrids, showed patterns of no or slow/delayed maltotriose utilization. The genome of the lager brewing yeast is composed of two subgenomes originated from S. cerevisiae and S. bayanus that underwent extensive chromosomal translocations and re-arrangements, including higher copy number of selected chromosomes (Dunn and Sherlock 2008; Nakao et al. 2009). The MTY1 (MTT1) α-glucoside transporter of S. pastorianus, identified as a unique yeast transporter with higher affinity for maltotriose than for maltose (Dietvorst et al. 2005; Salema-Oom et al. 2005), is present at the MAL1 (chromosome VII) locus of the S. bayanus subgenome present in lager yeasts (Nakao et al. 2009). Unfortunately, the two-species arrays developed and used previously to study the origin and evolution of this complex genome did not contain probes for this gene, as the sequences present in the microarray were based in the genome of the S. bayanus (var. uvarum) strain CBS7001 (Dunn and Sherlock 2008), a maltose fermenting but maltotriose nonfermenting yeast strain (see Table 3). Nevertheless, while several of the efficient maltotriose utilization lager yeast strains had a full-length S. cerevisiae chromosome VII in their genomes (especially the right arm where the AGT1-containing MAL1 locus is located), three lager strains that showed no or slow/delayed maltotriose utilization (strains CBS2440, DBVPG6258 and DBVPG6261) had lost most of their S. cerevisiae chromosome VII during the genome re-arrangements typical of this hybrid yeast (Dunn and Sherlock 2008); this shows a correlation between the lack of the AGT1 gene and the slow/delayed maltotriose utilization phenotype, similar to what is seen in the S. cerevisiae strains as described in the following.

In the case of the S. cerevisiae yeast strains analysed, more diverse maltotriose utilization phenotypes were observed. Besides efficient maltotriose-fermenting S. cerevisiae yeast strains (Zastrow et al. 2001; Londesborough 2001), previous reports have shown that several industrial S. cerevisiae yeast strains experience nonfermentative (respiratory) growth on this sugar, i.e. growth without concomitant ethanol production; as expected, growth was impaired with the addition of the mitochondrial inhibitor antimycin A (Zastrow et al. 2000, 2001; Dietvorst et al. 2005; Salema-Oom et al. 2005). Other industrial strains have been previously shown to have an extended lag phase (c. 1 day) during growth in maltotriose, especially when the cells were pregrown on glucose (Londesborough 2001), but the new maltotriose utilization phenotypes that we found among some laboratory and industrial S. cerevisiae strains (see Figs 1, 4 and 5) add new complexity into the utilization patterns of this important carbon source by yeast cells.

Of all the maltose-fermenting S. cerevisiae yeast strains we analysed, only approx. one-third of them could utilize maltotriose efficiently (Table 3). As expected, strains selected for efficient fermentation of starch hydrolysates (one ale brewing, and seven baker’s yeast strains) were able to consume this carbon source efficiently, a phenotype shared with two of the laboratory yeast strains. The results obtained with the laboratory S. cerevisiae yeast strains are in accordance with the microarray data (shown in Fig. 3) that indicate that the AGT1 permease is required for efficient maltotriose consumption and fermentation by this yeast (see Alves et al. 2008). For example, strain YJM789 is a pathogenic isolate that is MAL1 and MAL3 (Wei et al. 2007), and thus contains a normal MAL11 gene at the MAL locus in chromosome VII and consequently lacks the AGT1 gene; it is unable to utilize maltotriose. This phenotype is shared with the homothalic MAL1 diploid Y55 strain (lacking the AGT1 gene), with strain CMY001 (having a MAL61::HA allele at the MAL1 locus, and thus lacking the AGT1 gene), and with the wine strain RM11–1a (Brem et al. 2002) that contains a nonfunctional version of the AGT1 gene (lacking a cytosine at position +996 of the ORF, and truncating the permease). All of these strains are unable to utilize maltotriose, while maltose fermentation is normal. We found that some industrial strains (e.g. strains CAT-1, PE-2, G34, UFMG-905 and UFMG-1007) had the AGT1 gene in their genomes (see Figs 2 and 3), but nevertheless these strains belonged to Group 2 (slow/delayed maltotriose utilization), or even Group 3 (no maltotriose utilization). We have sequenced the AGT1 present in some of these strains (e.g. CAT-1 and PE-2) and found that they encode bona-fide full-length permeases (S.L. Alves Jr, J.M. Thevelein and B.U. Stambuk, unpublished data). However, we have failed to find an UASMAL upstream of the AGT1 gene in strains CAT-1 and PE-2, which might explain why these strains fail to efficiently ferment maltotriose. In accordance with the importance of this gene for maltotriose fermentation, transcriptome studies have also shown a high expression of this gene during wort fermentation (James et al. 2003), and we have recently shown that AGT1 overexpression improves maltotriose fermentation by industrial yeast strains (Stambuk et al. 2006).

Our results clearly show that the presence of MALx1 (MAL11, MAL21, MAL31, MAL41 or MAL61) genes in the yeast genome does not allow efficient maltotriose consumption or fermentation by S. cerevisiae cells, contrary to the early claims of Day et al. (2002a,b). However, some alleles of these MALx1 transporter genes might be implicated in the novel slow/delayed growth phenotypes we have observed for some S. cerevisiae yeast strains (Figs 4 and 5). In this regard, the MAL3 locus is an interesting candidate, as it is present in almost all strains analysed (including several members of Group 2), and a detailed mapping and molecular analysis of this locus revealed a complex structure with several MALx1-related alleles repeated in tandem (Michels et al. 1992); unfortunately, these MAL31 alleles have not been functionally analysed regarding substrate specificity. Although MALx1 genes show a high (98–99%) degree of sequence identity, minor sequence variations among these transporters can impart quite distinct transport properties to the permeases, as recently shown for a MAL21 allele (Hatanaka et al. 2009), or even for AGT1 alleles found in some distillers yeasts (Smit et al. 2008). The novel delayed maltotriose utilization profile we observed, i.e., where maltotriose utilization occurs only after an extensive lag phase, could be because of the expression of an extracellular glucoamylase, as is typically found in S. cerevisiae var diastaticus yeasts (Pretorius et al. 1991). Indeed, maltotriose is classically used as substrate to measure the activity of this enzyme at the surface of yeast cells. These diastaticus yeasts strains also grow on starch after an extensive lag phase (up to 4 days), when expression of the polymorphic STA1-STA3 genes encoding the extracellular glucoamylase takes place (Pretorius et al. 1991; Vivier et al. 1999). However, we have not been able to detect the presence of STA genes in the genome of several of the strains belonging to Group 2, using PCR with specific primers (S.L. Alves Jr, J.M. Thevelein and B.U. Stambuk, unpublished data), and assays performed to measure extracellular maltotriose hydrolysis by the late maltotriose consuming yeast strains also failed. Further studies will be required to reveal the molecular basis of the slow/delayed maltotriose utilization phenotypes uncovered in the present high throughput screening study of Saccharomyces yeasts.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from the Brazilian agencies CAPES, CNPq (552877/2007–7) and FAPESP (04/10067–6), and by a USA National Science Foundation ADVANCE grant DBI-0340856 to B.D. Work of B.U.S. at Stanford University was possible through a visiting fellowship from CAPES (BEX2793–05-9).

References

- Alves SL Jr, Herberts RA, Hollatz C, Miletti LC and Stambuk BU (2007) Maltose and maltotriose active transport and fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Am Soc Brew Chem 65, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Alves SL Jr, Herberts RA, Hollatz C, Trichez D, Miletti LC, de Araujo PS and Stambuk BU (2008) Molecular analysis of maltotriose active transport and fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals a determinant role for the AGT1 permease. Appl Environ Microbiol 74, 1494–14501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA and Struhl K (1995) Short Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Basso LC, Amorim HV, de Oliveira AJ and Lopes ML (2008) Yeast selection for fuel ethanol production in Brazil. FEMS Yeast Res 8, 1155–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista AS, Miletti LC and Stambuk BU (2004) Sucrose fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae lacking hexose transport. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 8, 26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batistote M, da Cruz SH and Ernandes JR (2006) Altered patterns of maltose and glucose fermentation by brewing and wine yeasts influenced by the complexity of nitrogen source. J Inst Brew 112, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bell PJ, Higgins VJ and Attfield PV (2001) Comparison of fermentative capacities of industrial baking and wild-type yeasts of the species Saccharomyces cerevisiae in different sugar media. Lett Appl Microbiol 32, 224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem RB, Yvert G, Clinton R and Kruglyak L (2002) Genetic dissection of transcriptional regulation in budding yeast. Science 296, 752–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charron MJ and Michels CA (1988) The naturally occurring alleles of MAL1 in Saccharomyces species evolved by various mutagenic processes including chromosomal rearrangements. Genetics 120, 83–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumplen RM, Slaughter JC and Stewart GG (1996) Characteristics of maltose transporter activity in an ale and lager strain of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Lett Appl Microbiol 23, 448–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day RE, Higgins VJ, Rogers PJ and Dawes IW (2002a) Characterization of the putative maltose transporters encoded by YDL247w and YJR160c. Yeast 19, 1015–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day RE, Rogers PJ, Dawes IW and Higgins VJ (2002b) Molecular analysis of maltotriose transport and utilization by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol 68, 5326–5335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRisi JL, Iyer VR and Brown PO (1997) Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science 278, 680–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietvorst J, Londesborough J and Steensma HY (2005) Maltotriose utilization in lager yeast strains: MTT1 encodes a maltotriose transporter. Yeast 22, 775–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn B and Sherlock G (2008) Reconstruction of the genome origins and evolution of the hybrid lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus. Genome Res 18, 1610–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn B, Levine RP and Sherlock G (2005) Microarray karyotyping of commercial wine yeast strains reveals shared, as well as unique, genomic signatures. BMC Genomics 6, 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuermann M, Charbonnel L, De Montigny J, Bloch JC, Potier S and Souciet JL (1995) Sequence of a 9.8 kb segment of yeast chromosome II including the three genes of the MAL3 locus and three unidentified open reading frames. Yeast 11, 667–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes FC, Silva CL, Marini MM, Oliveira ES and Rosa CA (2007) Use of selected indigenous Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains for the production of the traditional cachaça in Brazil. J Appl Microbiol 103, 2438–2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerring SL, Connelly C and Hieter P (1991) Positional mapping of genes by chromosome blotting and chromo-some fragmentation. Methods Enzymol 194, 57–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han EK, Cotty F, Sottas C, Jiang H and Michels CA (1995) Characterization of AGT1 encoding a general α-glucoside transporter from Saccharomyces. Mol Microbiol 17, 1093–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatanaka H, Omura F, Kodama Y and Ashikari T (2009) Gly-46 and His-50 of yeast maltose transporter Mal21p are essential for its resistance against glucose-induced degradation. J Biol Chem 284, 15448–15457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton-Larsen J and Brandt A (2006) Fermentation of high concentrations of maltose by Saccharomyces cerevisiae is limited by the COMPASS methylation complex. Appl Environ Microbiol 72, 7176–7182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James TC, Campbell S, Donnelly D and Bond U (2003) Transcription profile of brewery yeast under fermentation conditions. J Appl Microbiol 94, 432–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama Y, Fukui N, Ashikari T, Shibano Y, Morioka-Fujimoto K, Hiraki Y and Nakatani K (1995) Improvement of maltose fermentation efficiency: constitutive expression of MAL genes in brewing yeasts. J Am Soc Brew Chem 53, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Londesborough J (2001) Fermentation of maltotriose by brewer’s and baker’s yeast. Biotechnol Lett 23, 1995–2000. [Google Scholar]

- Meneses FJ and Jiranek V (2002) Expression patterns of genes and enzymes involved in sugar catabolism in industrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains displaying novel fermentation characteristics. J Inst Brew 108, 322–335. [Google Scholar]

- Meneses FJ, Henschke PA and Jiranek V (2002) A survey of industrial strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals numerous altered patterns of maltose and sucrose utilisation. J Inst Brew 108, 310–321. [Google Scholar]

- Michels CA, Read E, Nat K and Charron MJ (1992) The telomere-associated MAL3 locus of Saccharomyces is a tandem array of repeated genes. Yeast 8, 655–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer RK and Johnston JR (1986) Genealogy of principal strains of the yeast genetic stock center. Genetics 113, 35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao Y, Kanamori T, Itoh T, Kodama Y, Rainieri S, Nakamura N, Shimonaga T, Hattori M et al. (2009) Genome sequence of the lager brewing yeast, an interspecies hybrid. DNA Res 16, 115–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumov G, Naumova E and Michels CA (1994) Genetic variation of the repeated MAL loci in natural populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces paradoxus. Genetics 136, 803–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak S, Zechner-Krpan V and Marie V (2004) Regulation of maltose transport and metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Technol Biotechnol 42, 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius IS, Lambrechts MG and Marmur J (1991) The glucoamylase multigene family in Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. diastaticus: an overview. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 26, 53–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querol A and Bond U (2009) The complex and dynamic genomes of industrial yeasts. FEMS Microbiol Lett 293, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautio J and Londesborough J (2003) Maltose transport by brewer’s yeast in brewer’s wort. J Inst Brew 109, 251–261. [Google Scholar]

- Salema-Oom M, Pinto VV, Goncalves P and Spencer-Martins I (2005) Maltotriose utilization by industrial Saccharomyces strains: characterization of a new member of the α-glucoside transporter family. Appl Environ Microbiol 71, 5044–5049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos SKB, Basilio ACM, Brasileiro BTRV, Simoes DA, da Silva-Filho EA and de Morais M Jr (2007) Identification of yeasts within Saccharomyces sensu stricto complex by PCR-fingerprinting. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 23, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva-Filho EA, Brito dos Santos SK, Resende AM, de Morais JO, de Morais MA Jr and Simoes DA (2005) Yeast population dynamics of industrial fuel-ethanol fermentation process assessed by PCR-fingerprinting. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 88, 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit A, Moses SG, Pretorius IS and Cordero-Otero RR (2008) The Thr505 and Ser557 residues of the AGT1-encoded α-glucoside transporter are critical for maltotriose transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Appl Microbiol 104, 1103–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambuk BU and de Araujo PS (2001) Kinetics of active α-glucoside transport by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res 1, 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambuk BU, Alves SL Jr, Hollatz C and Zastrow CR (2006) Improvement of maltotriose fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Lett Appl Microbiol 43, 370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambuk BU, Dunn B, Alves SL Jr, Duval EH and Sherlock G (2009) Industrial fuel ethanol yeasts contain adaptive copy number changes in genes involved in vitamin B1 and B6 biosynthesis. Genome Res 19, 2271–2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivier MA, Sollitti P and Pretorius IS (1999) Functional analysis of multiple AUG codons in the transcripts of the STA2 glucoamylase gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet 261, 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volckaert G, Voet M and Robben J (1997) Sequence analysis of a near-subtelomeric 35.4 kb DNA segment on the right arm of chromosome VII from Saccharomyces cerevisiae carrying the MAL1 locus reveals 15 complete open reading frames, including ZUO1, BGL2 and BIO2 genes and a ABC transporter gene. Yeast 13, 251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Bali M, Medintz I and Michels CA (2002) Intracellular maltose is sufficient to induce MAL gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukariot Cell 1, 696–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, McCusker JH, Hyman RW, Jones T, Ning Y, Cao Z, Gu Z, Bruno D et al. (2007) Genome sequencing and comparative analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain YJM789. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 12825–12830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SH, Mukerjea R and Robyt JF (2003) Specificity of yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) in removing carbohydrates by fermentation. Carbohyd Res 338, 1127–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zastrow CR, Mattos MA, Hollatz C and Stambuk BU (2000) Maltotriose metabolism by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Lett 22, 455–459. [Google Scholar]

- Zastrow CR, Hollatz C, de Araujo PS and Stambuk BU (2001) Maltotriose fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 27, 34–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, D’Amore T, Russell I and Stewart GG (1994a) Transport kinetics of maltotriose in strains of Saccharomyces. J Ind Microbiol 13, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, D’Amore T, Russell I and Stewart GG (1994b) Factors influencing maltotriose utilization during brewery wort fermentations. J Am Soc Brew Chem 52, 41–47. [Google Scholar]