Abstract

Introduction

We aimed to evaluate sexual function, sexual knowledge, and fertility status in adult patients with congenital genitourinary abnormalities (CGUA).

Methods

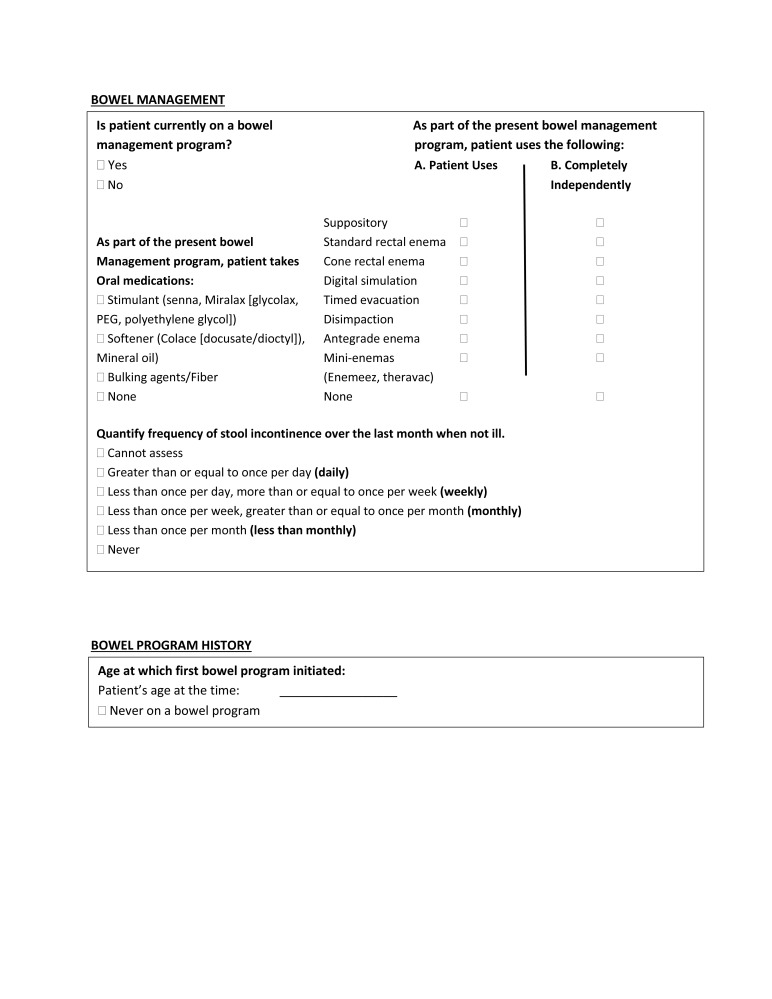

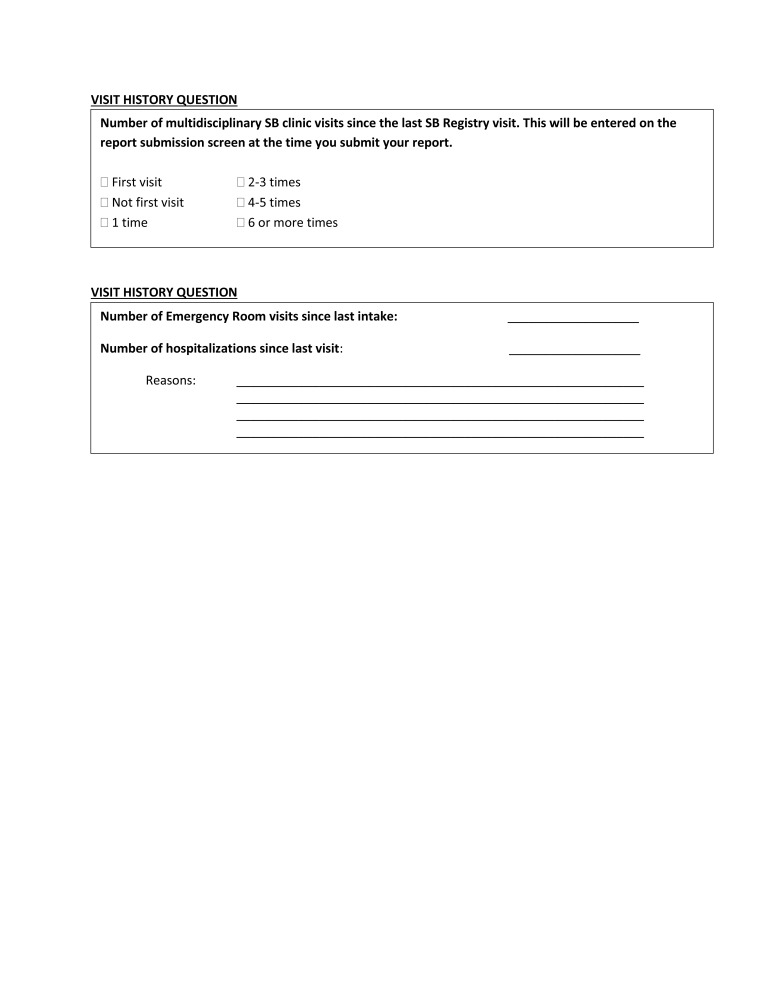

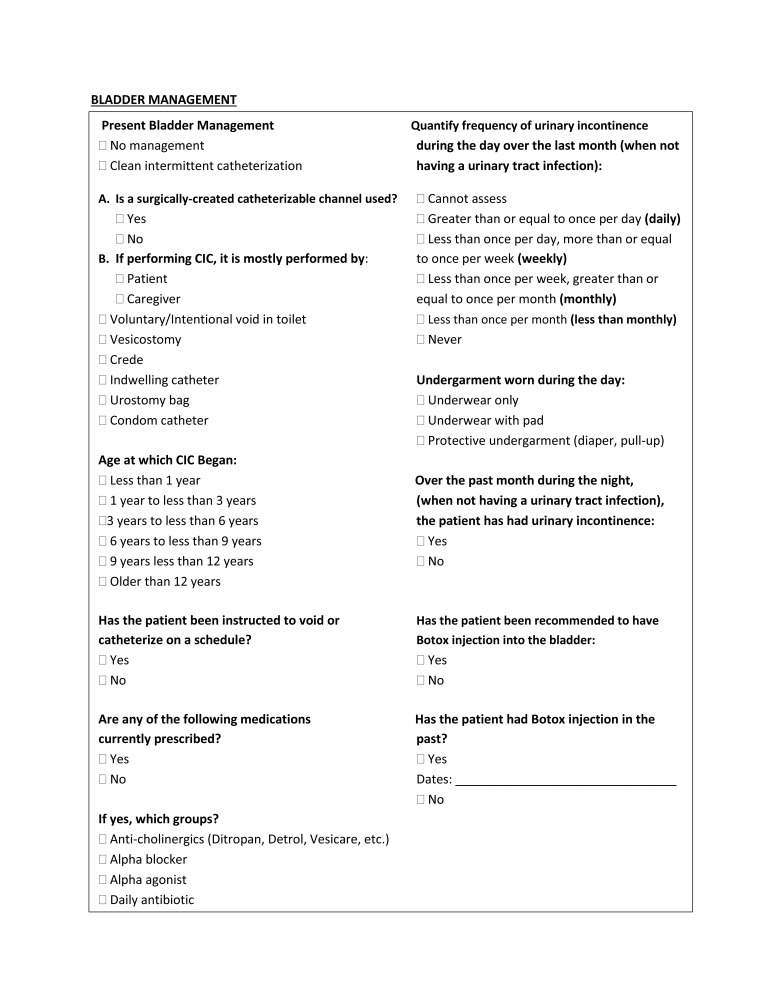

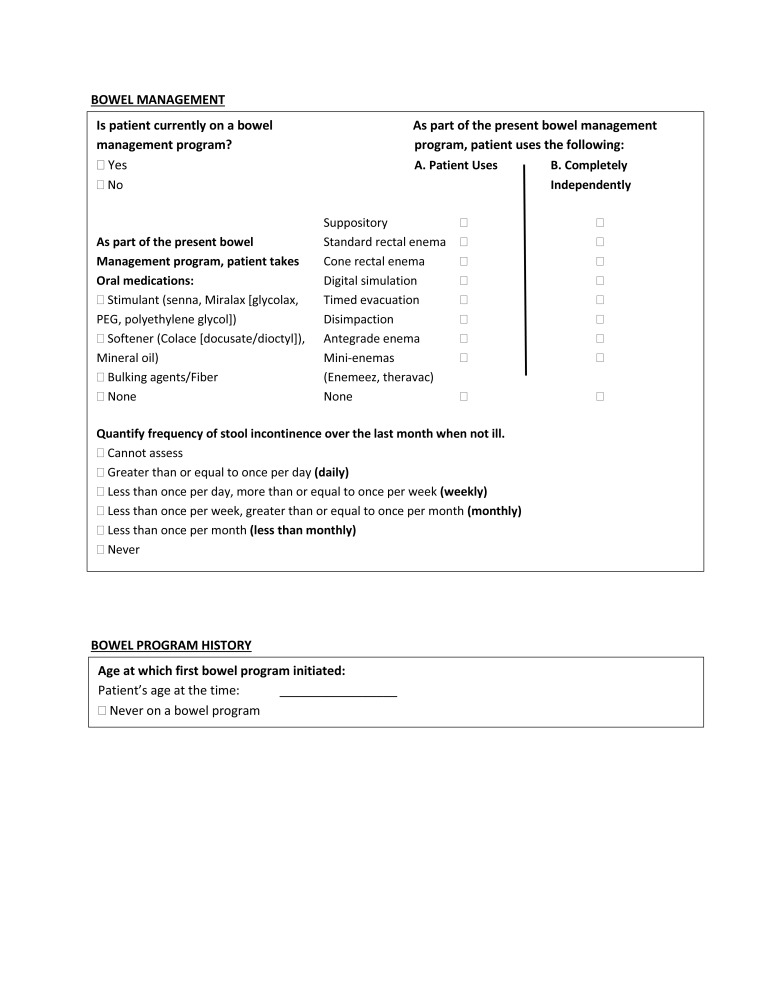

Adult patients with CGUA who were referred to a single transitional urology clinic between 2014 and 2017 were prospectively recruited to participate in the study. Questionnaires about general demographics, bowel and bladder continence, fertility, and sexuality were gathered. Validated questionnaires, including the Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM) and Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women (BISF-W), were also collected.

Results

A total of 167 adults with CGUA were referred to our clinic within the defined time frame. Sixty patients (25 males, 35 females) with a mean age of 25.4 years (range 18–75) met inclusion criteria and responded to questionnaires pertaining to sexuality and fertility. Forty-five (75%) responded to the fertility questionnaire; 26 (58%) had never heard of assisted reproductive technologies, and only one had received prior fertility counselling. Fifty-eight participants (97%) responded to the sexuality questionnaire; 21 (36%) reported a history of sexual activity, with 12 (21%) being currently sexually active. Twenty (34%) wanted to learn more about sexuality and/or fertility. The SHIM response rate was 44%, and only three females (9%) completed the BISF-W in its entirety.

Conclusions

Adults with CGUA desire more sexuality and fertility education, yet they are uncomfortable completing current questionnaires. Our sexuality and fertility questionnaires are too challenging for this patient population to complete despite assistance. Thus, modifications are urgently needed. Additionally, medical providers should discuss sexual and reproductive health with these patients earlier and in more detail.

Introduction

Spinal dysraphism is one of the most common birth defects,1 with incidence ranging from 3.4–4.0 per 10 000 live births in the U.S.2 Due to medical advancement, the life expectancy of patients with spinal dysraphism has extended to the point where it is no longer exclusively considered a pediatric disease. As these patients transition into adulthood, they encounter many difficulties. From a urological perspective, bladder/bowel management and preservation of renal function tend to be the primary focus, while problems with sexual or reproductive functioning are less often addressed. However, sexual function and fertility status are important aspects of adult life and have been shown to impact quality of life.3,4

Few studies have investigated sexual function in adults with spinal dysraphism or other congenital genitourinary abnormality (CGUA),5–15 and many of these were published more than a decade ago.5–10 Five of these studies used validated questionnaires,9,10,13–15 of which only two included both male and female subjects.10,14 Given this lack of objective data in the literature, the present study aimed to further examine sexual function in CGUA patients by applying validated questionnaires. Sexual knowledge and fertility status in this patient population was also evaluated.

Methods

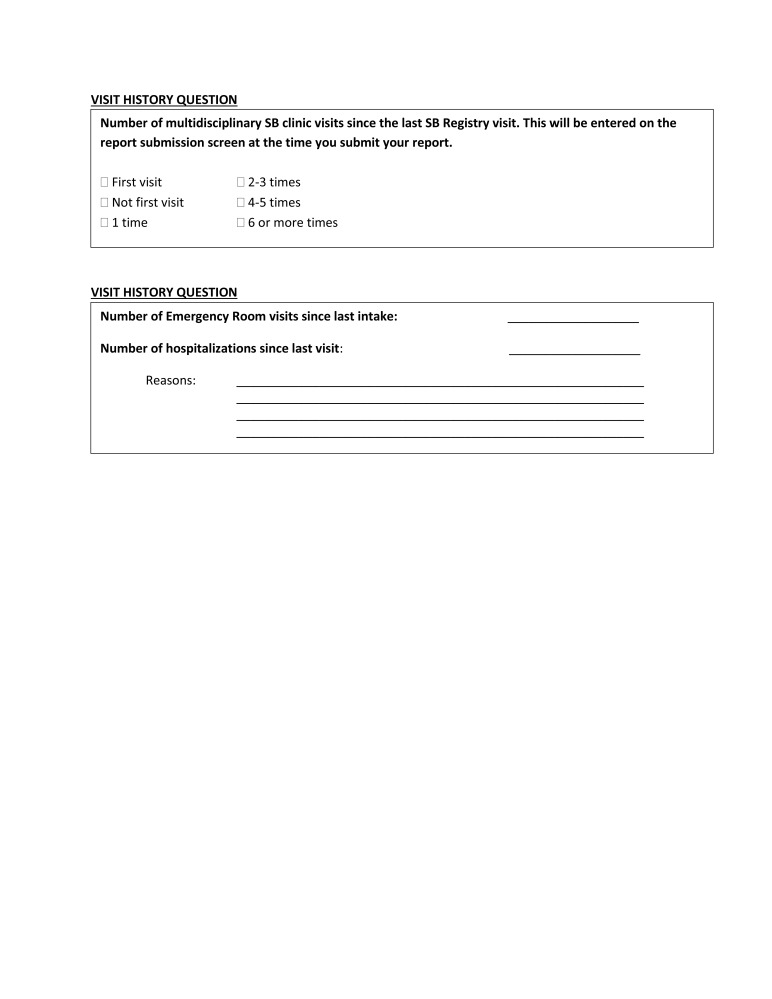

Patients who visited a single tertiary transitional urology care clinic at our institution were identified for study participation as part of a prospective cohort database. A cross-sectional study of adult patients with spinal dysraphism or other CGUA referred to the clinic between February 2014 and May 2017 was performed. Approval by the institutional review board was obtained prior to onset.

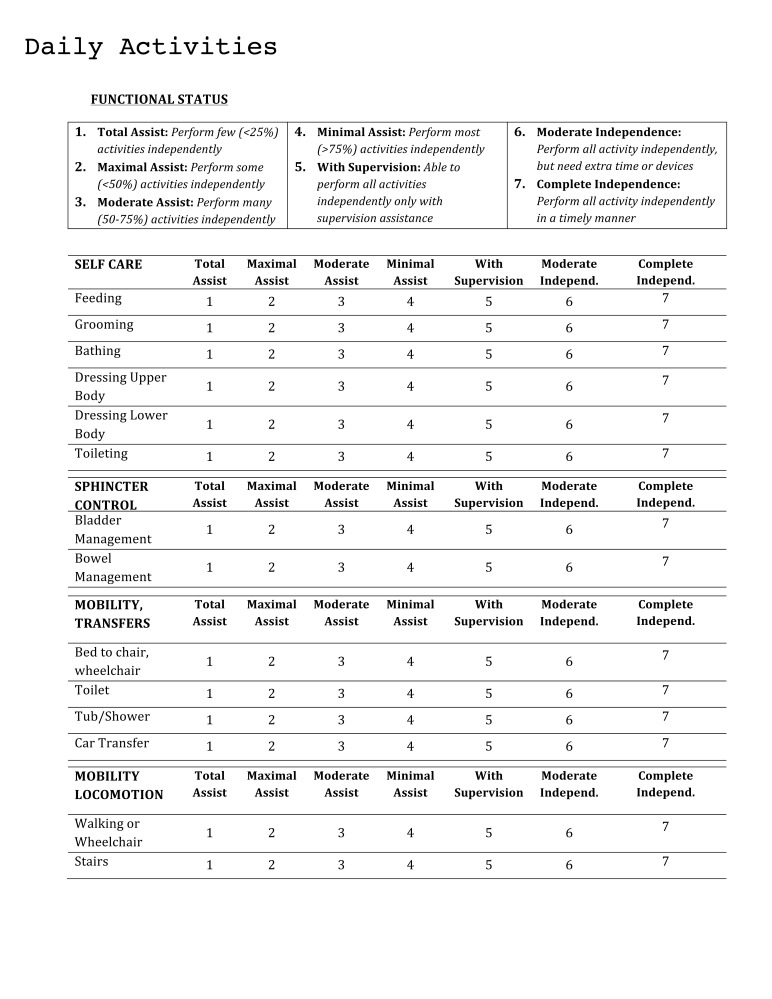

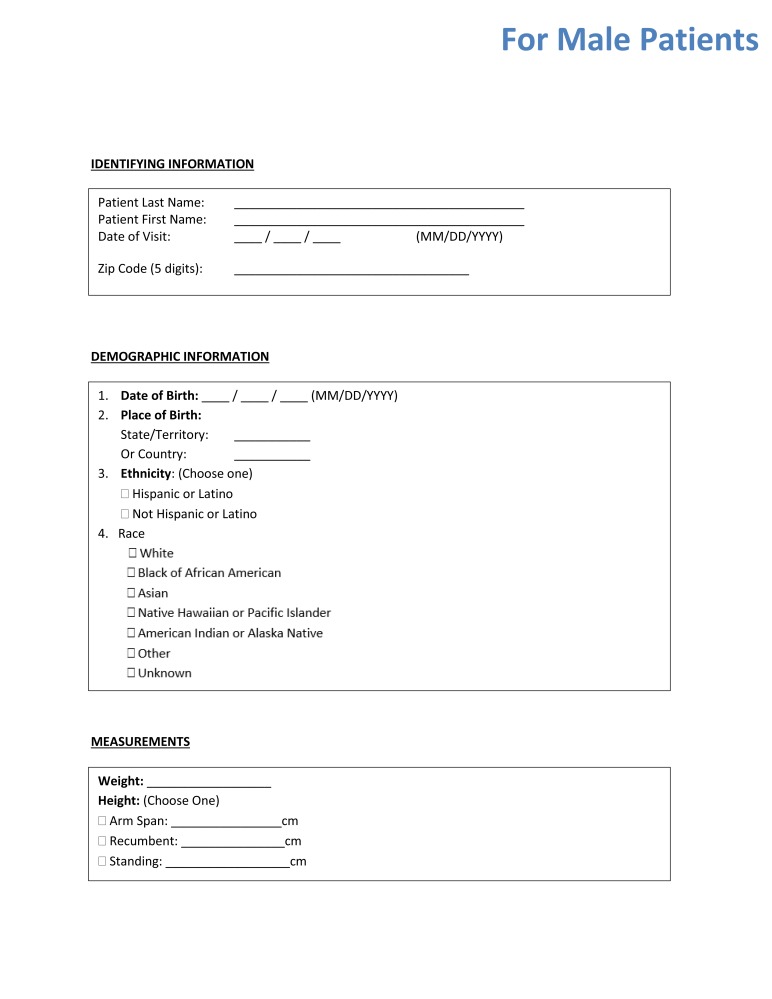

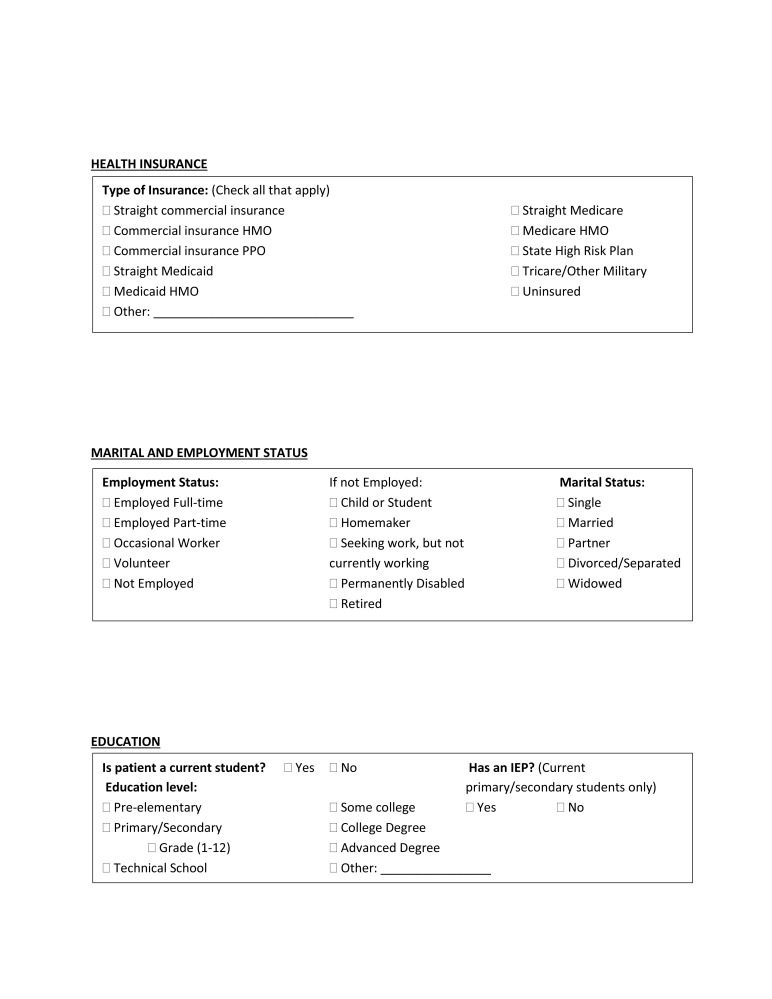

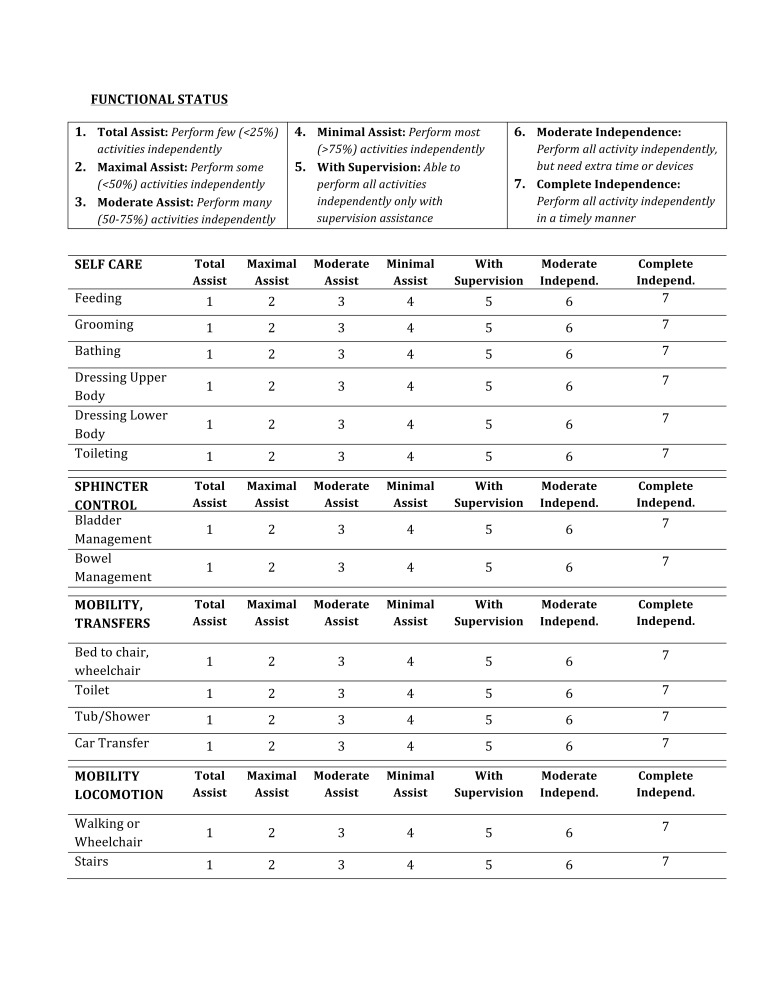

Questionnaires were administered to patients who consented to study participation. Patients were offered and received assistance in completing questionnaires by research coordinators if they desired. Patients decided if their parents were present or absent during the sexuality/fertility discussions. Patients were excluded from analysis for either poor cognitive ability or poor functional status, defined as an education level of pre-elementary and cumulative self-care score of ≤12, respectively. The self-care score was calculated from participants’ self-reported degree of dependence in six domains: feeding, grooming, bathing, dressing upper body, dressing lower body, and toileting. Responses to each of these six domains, which were based on a rating scale from 1 (total assist) to 7 (complete independence), were summed to arrive at the total self-care score (range 6–42). Since the aim of the study was to focus on adult patients, patients under 18 years of age were also excluded from analysis.

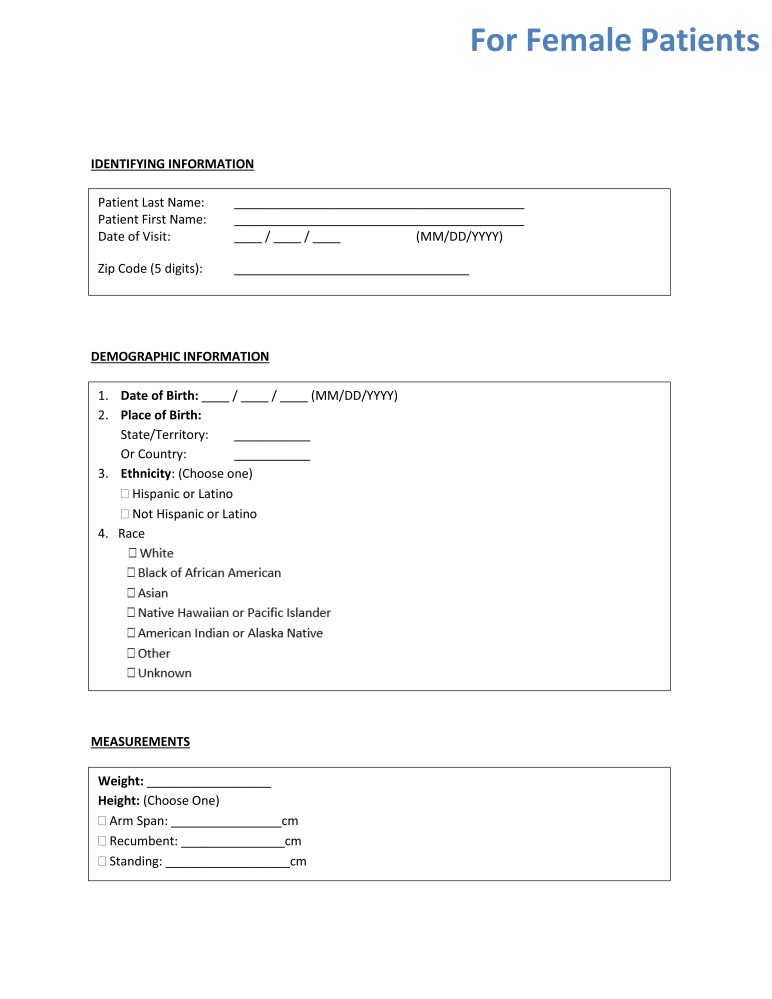

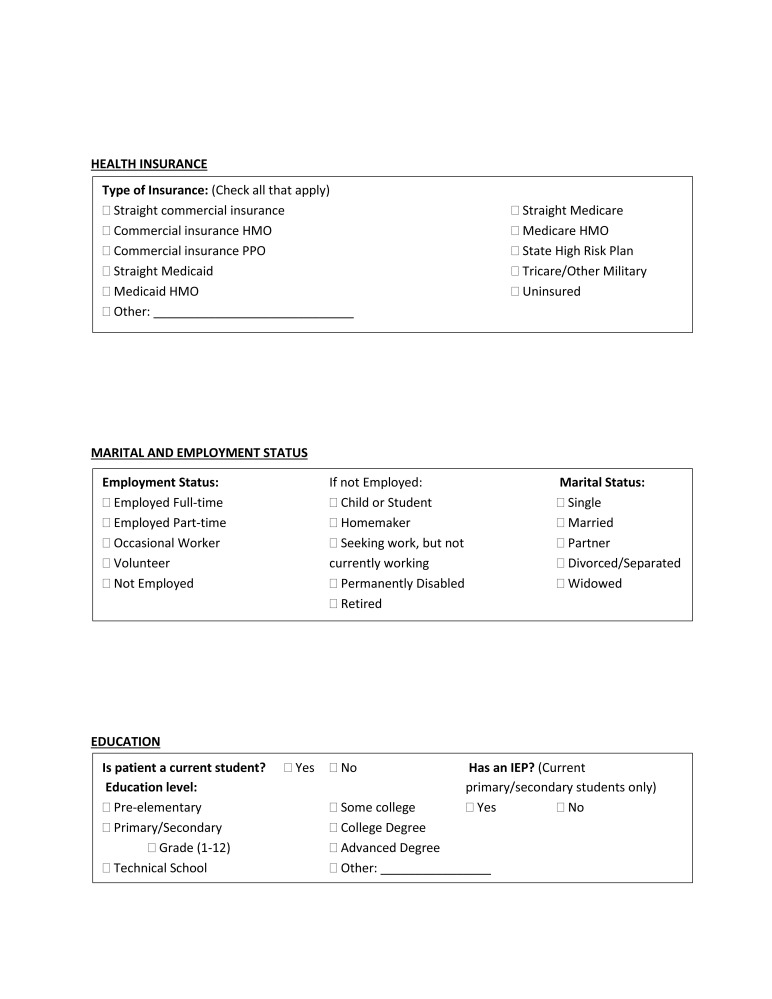

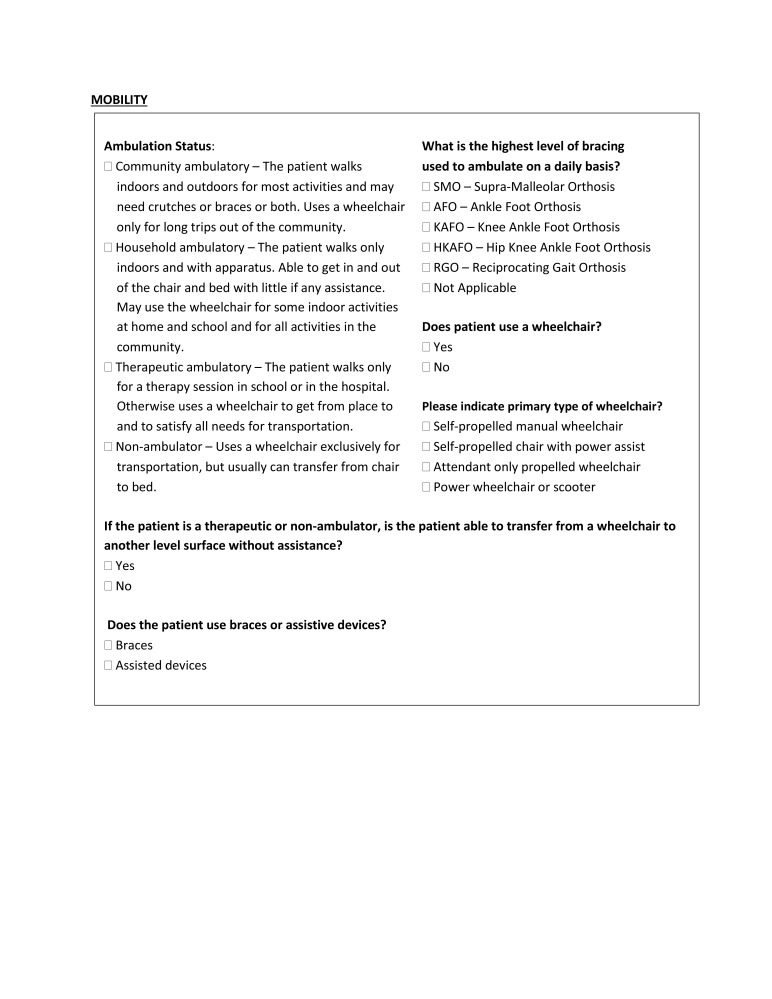

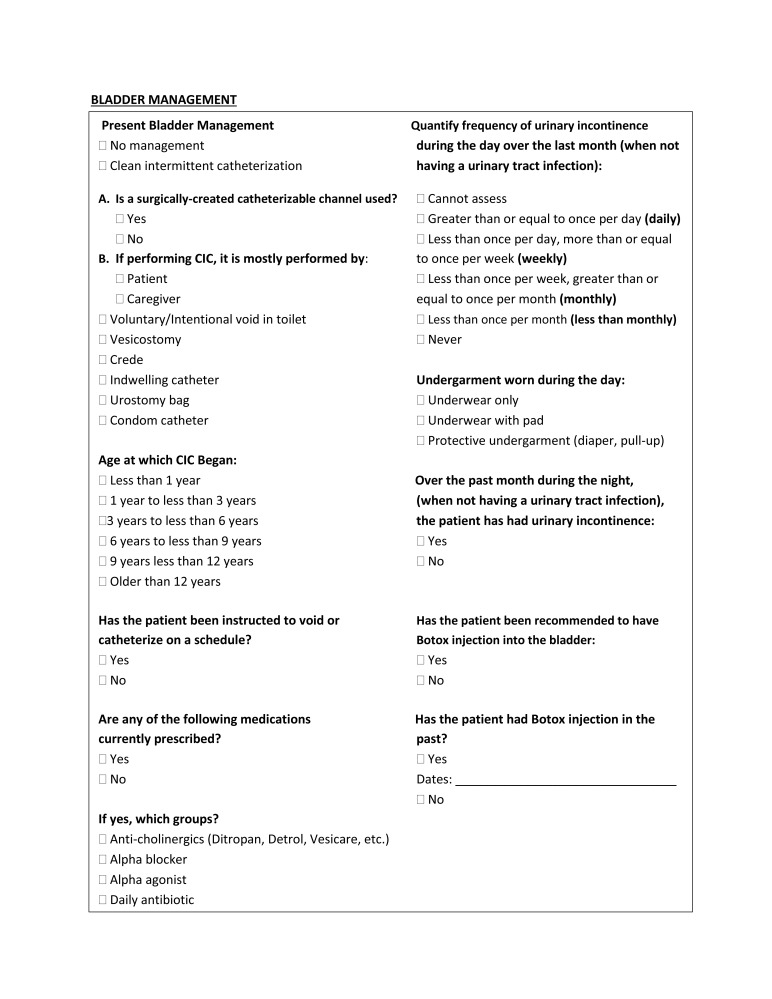

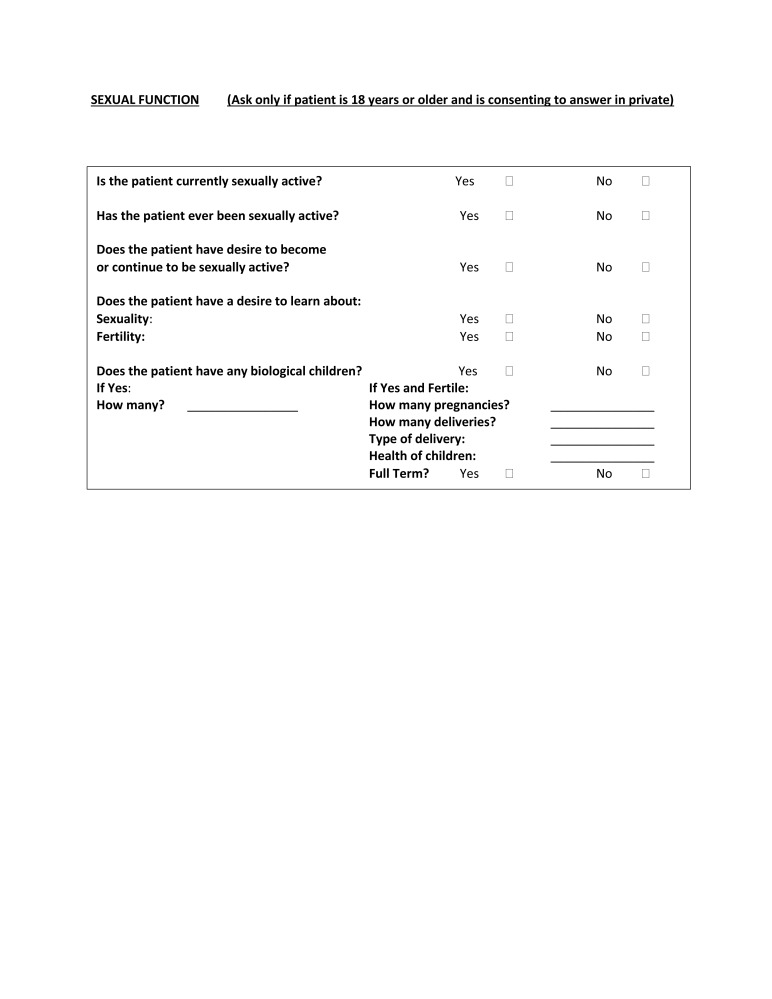

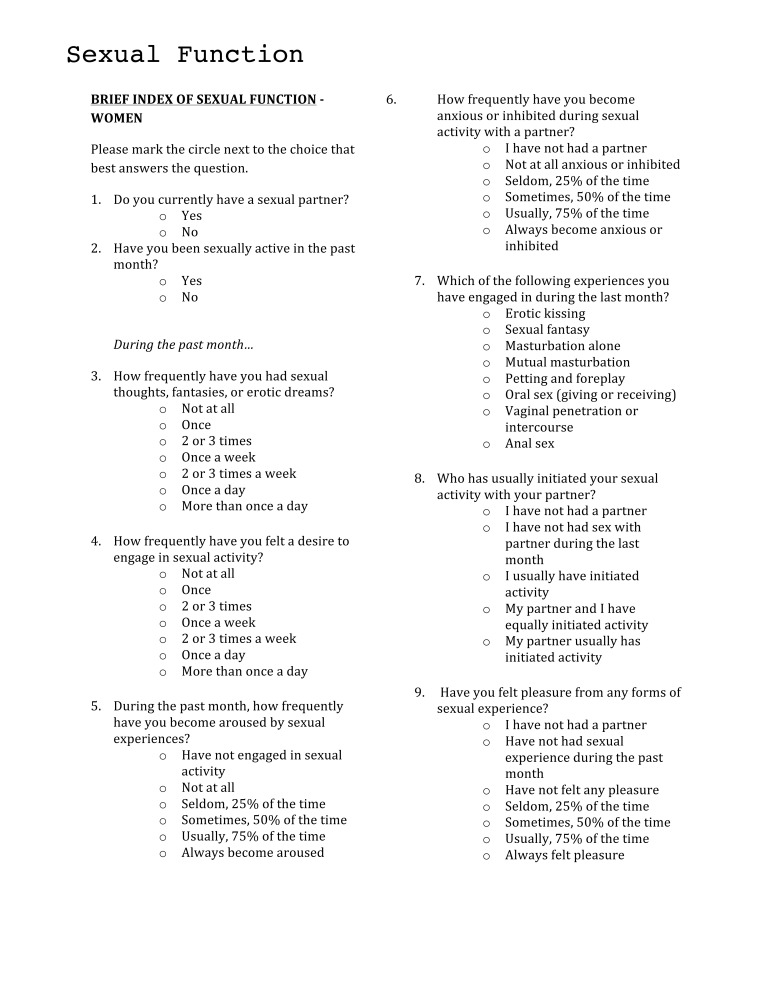

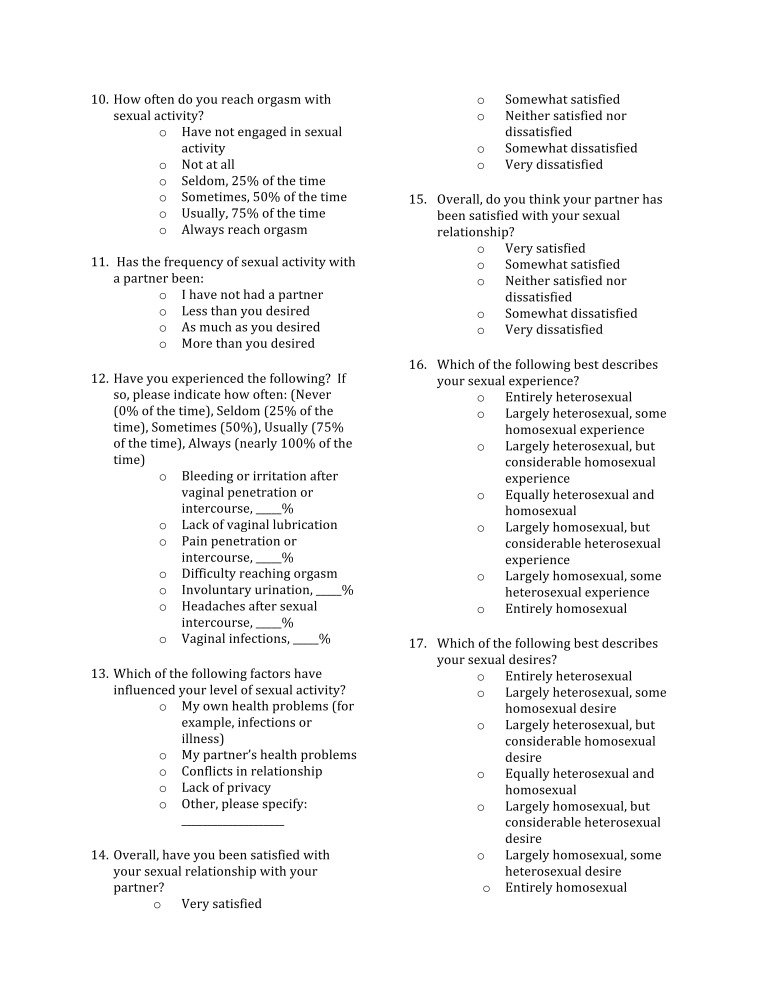

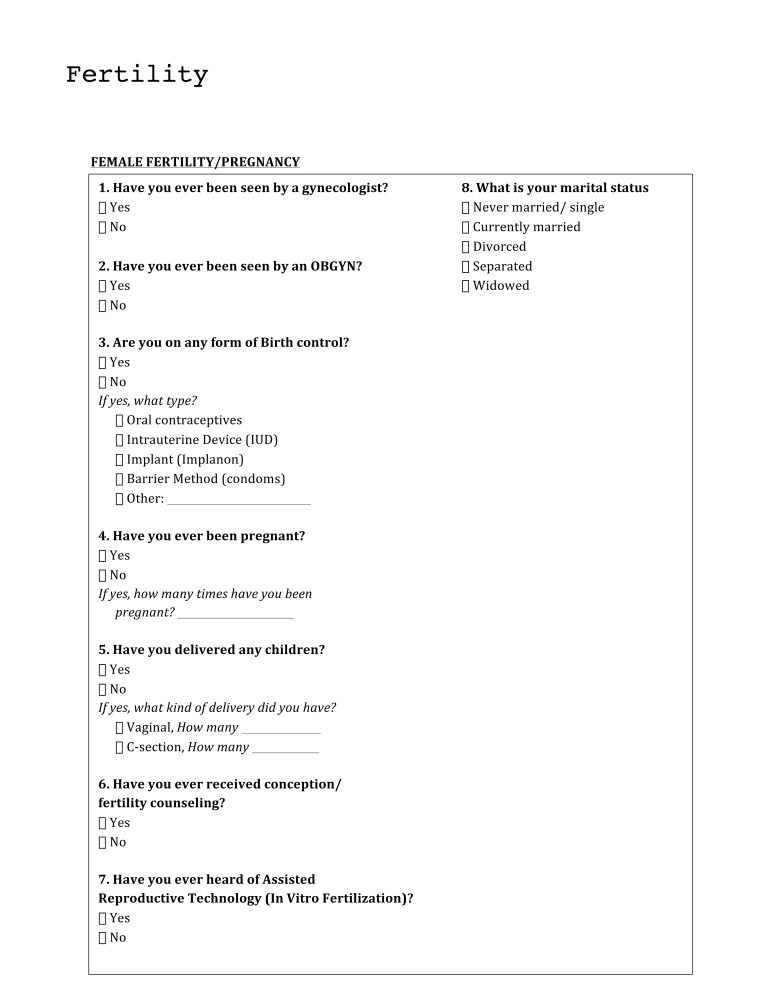

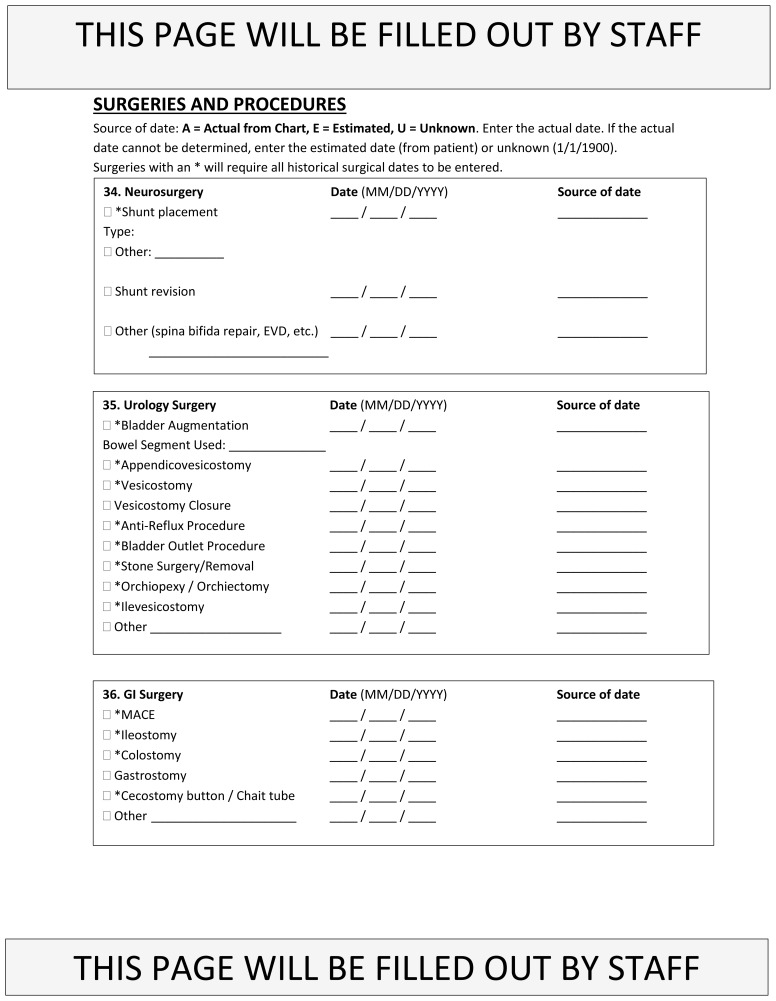

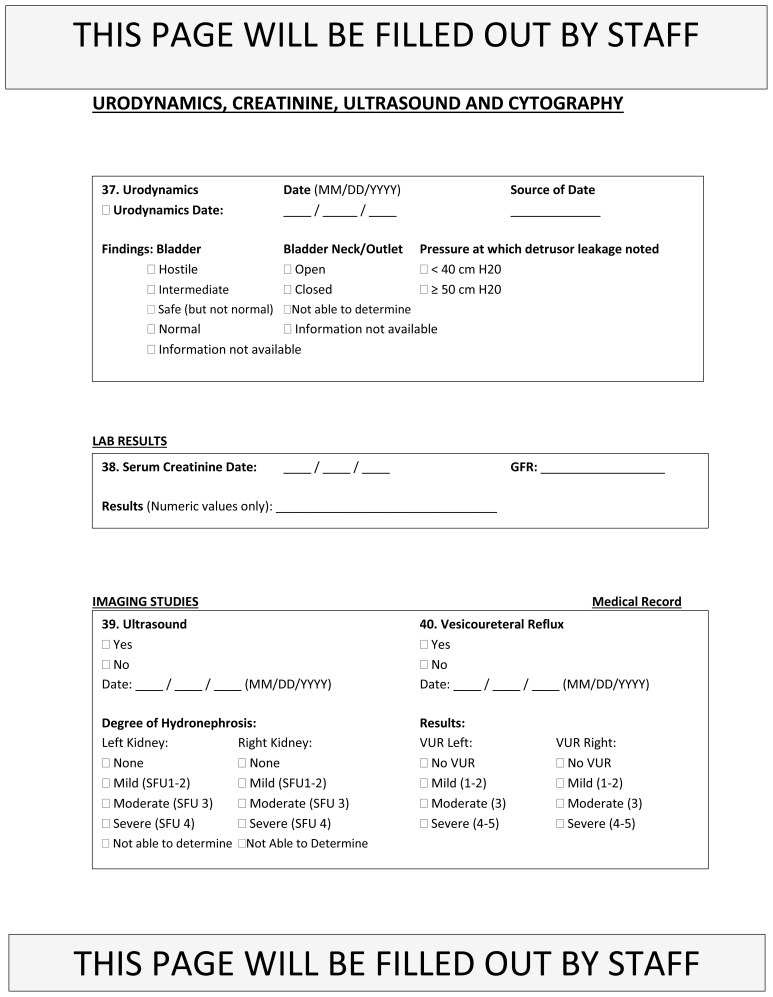

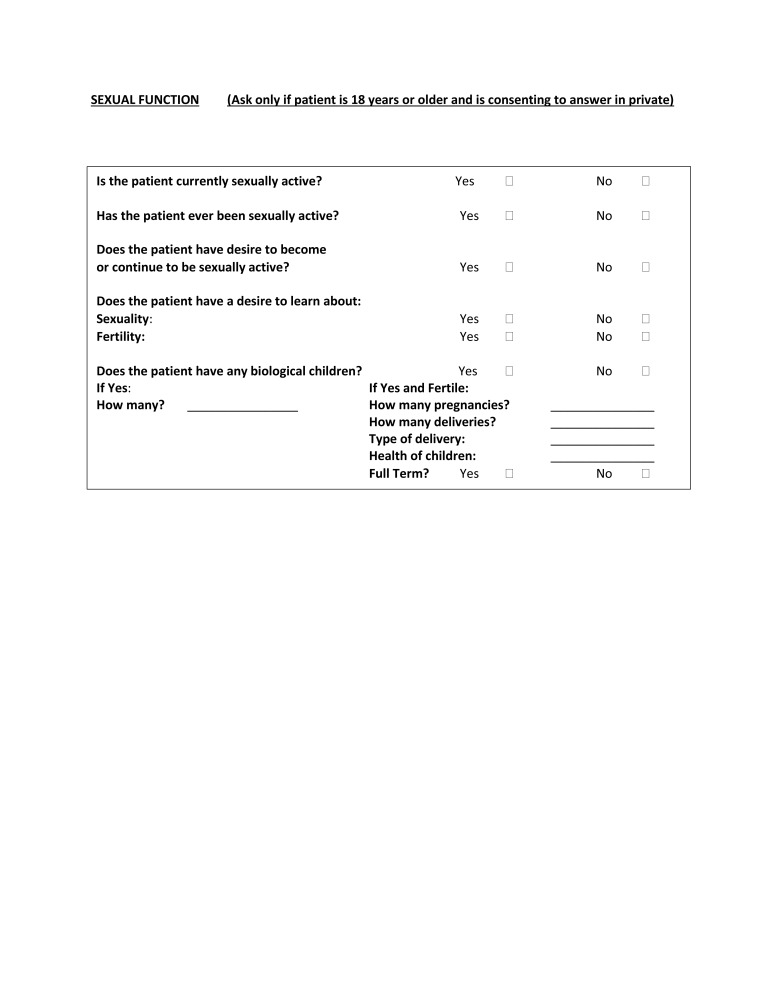

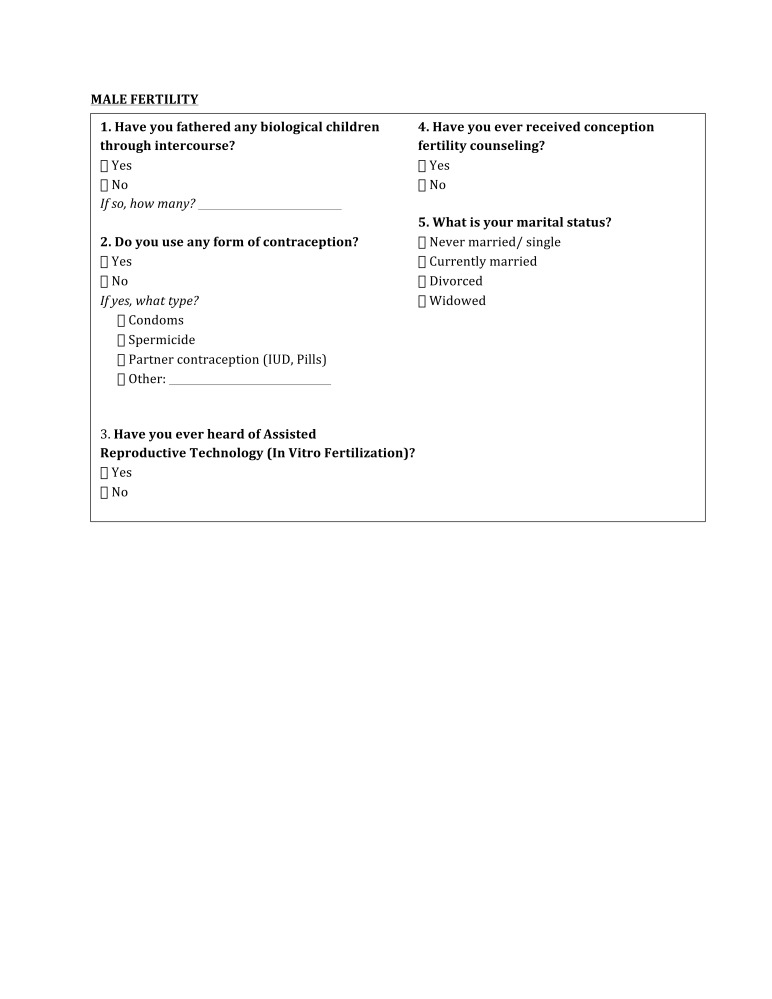

Study questionnaires included questions about general demographics, education, health insurance, physical disability, bowel and bladder continence, partnership, fertility status, sexual function, and sexual knowledge. The questionnaires for males also included the Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM), whereas the female questionnaires included the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women (BISF-W), both of which are validated questionnaires to assess sexual function. For ease of reference, the male and female questionnaires are provided in Appendix 1.

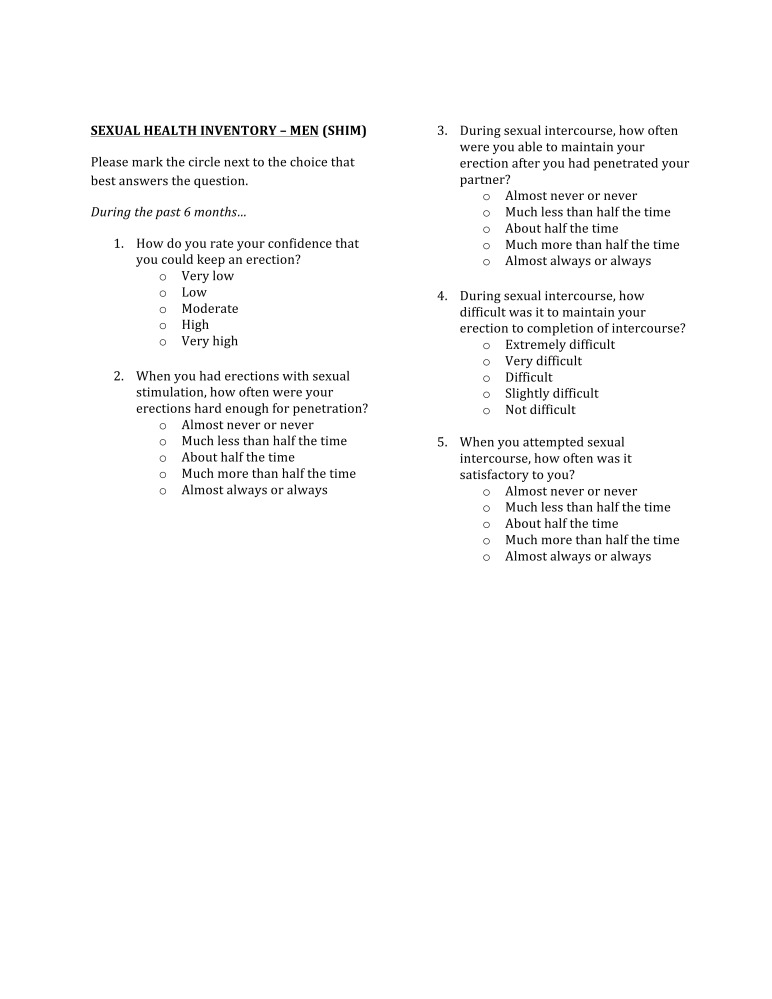

The SHIM is a five-item, self-report instrument for screening and diagnosing erectile dysfunction (ED) in clinical practice and research. Reponses to each of the five items are added to give a total SHIM score (range 1–25). ED is classified into five severity grades: no ED (≥22), mild (17–21), mild to moderate (12–16), moderate (8–11) and severe ED (1–7).16 The SHIM was preferred over the full International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) because of its brevity and ease of use, especially in this patient population.

The BISF-W is a self-report instrument for assessing female sexual function that was developed for use in clinical trials. The BISF-W is divided into seven dimension scores for each of the important aspects of female sexuality: D1 (thoughts/desire), D2 (arousal), D3 (frequency of sexual activity), D4 (receptivity/initiation), D5 (pleasure/orgasm), D6 (relationship satisfaction), and D7 (problems affecting sexual function).17

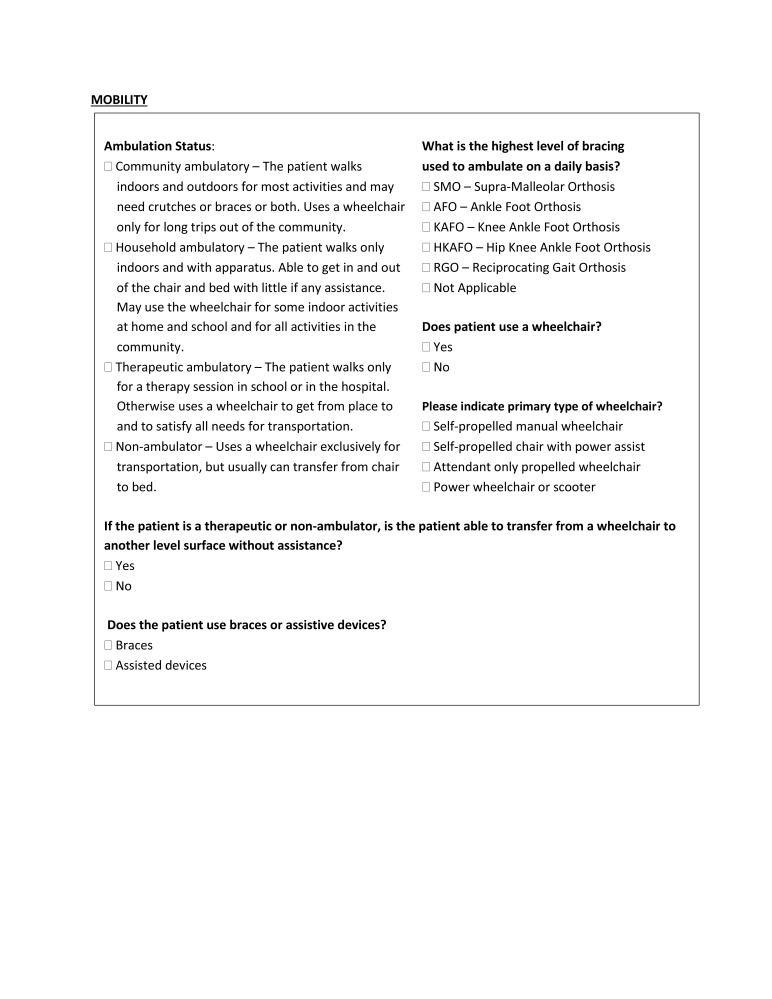

Ambulatory status was categorized using the Hoffer Classification.18 Participants with either community or household ambulatory status were considered “ambulators,” whereas those with therapeutic and non-ambulatory status were considered “non-ambulators.”

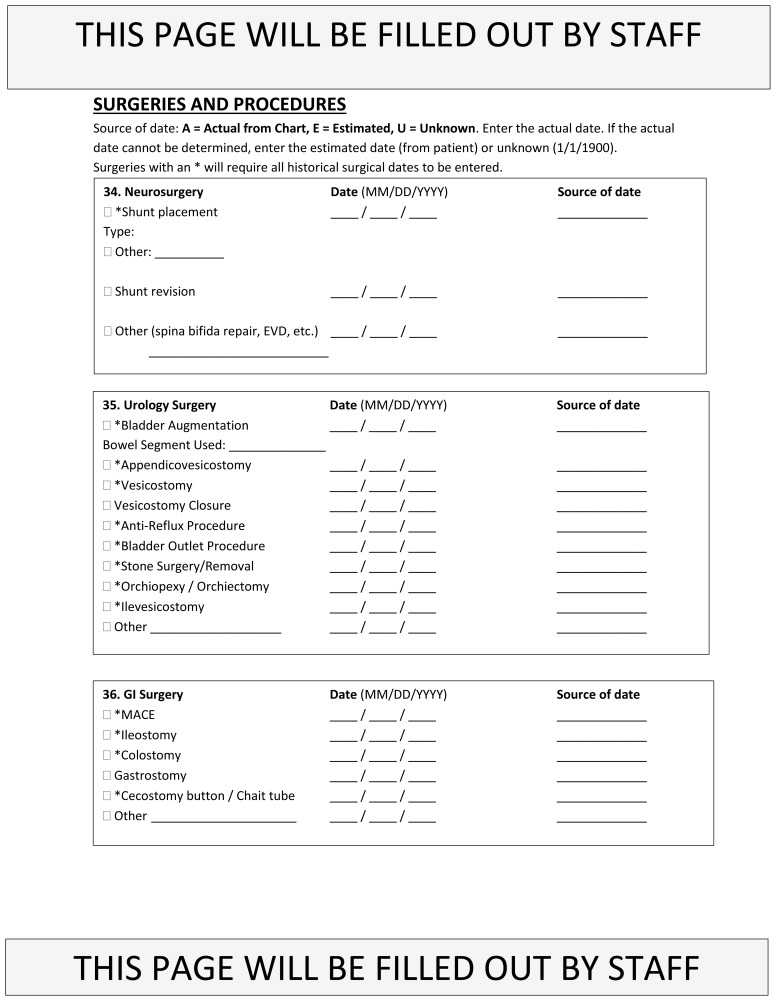

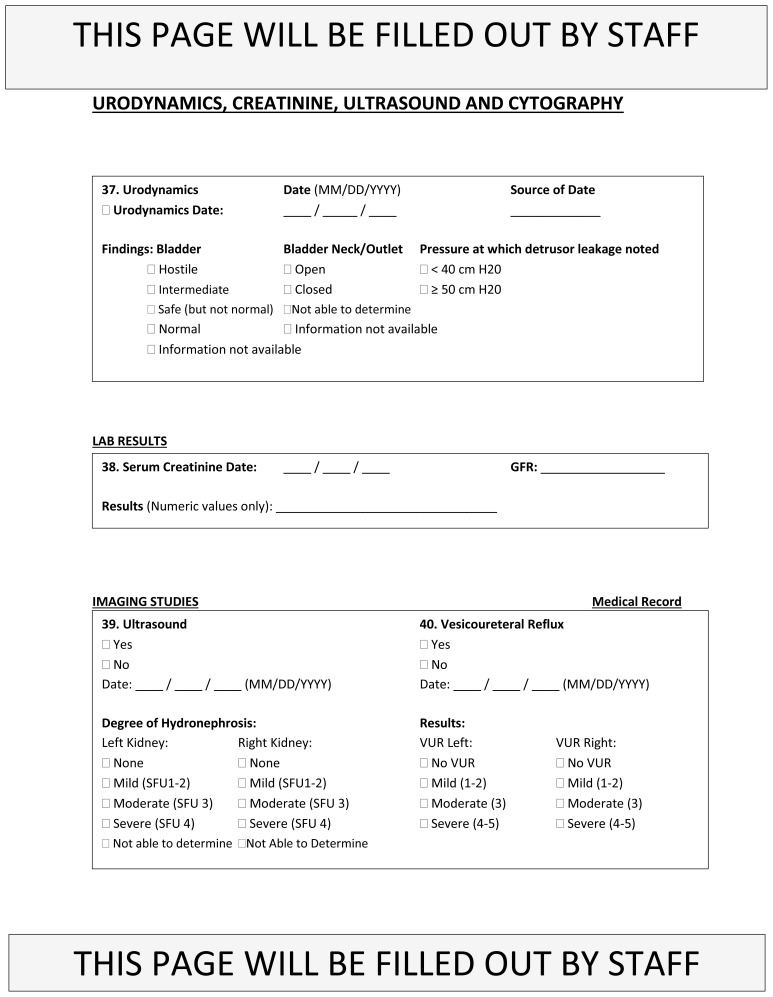

Additional data was collected from medical records of patients who filled out questionnaires, including primary diagnosis, surgical history, urodynamic results, and recent renal laboratory values and imaging.

Statistical analysis

Given our small sample size and the likelihood of non-normal data distribution, quantitative values are expressed as the median (range). These values were compared by the Mann-Whitney U-test. Proportions were compared using a Chi-square test or the Fisher’s exact test using GraphPad Prism 7.0c software for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, U.S.). The number of observations was considered when choosing the proper statistical test in order to ensure validity of results. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics & health status

A total of 167 patients were referred to the transitional urology clinic during the defined time period; 75 patients consented and filled out questionnaires. Of the 75 patients administered questionnaires, 67 (89%) responded to questions pertaining to their sexual function and fertility status. Two patients failed to meet our minimum age requirement and five patients failed to meet our criteria for study participation based on cognitive ability and functional status. Thus, seven patients in total were excluded from analysis. Sixty participants (25 males, 35 females) with a median age of 23 years (range 18–75) remained. Twenty-five percent of participants used assistance from research coordinators to complete the questionnaires. Research coordinators helped by reading and explaining the questionnaires.

Table 1 lists characteristics of male and female patients. There was no difference between genders regarding general demographics, hydrocephalus status (determined by presence or absence of a shunt), extent of physical disability (measured by self-care score and ambulatory status), and degree of urinary incontinence. Our small sample size prevented further comparison of characteristics.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of male and female participants

| Males (n=25) | Females (n=35) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 22 (18–75) | 23 (18–42) | 0.55 (NS) |

| Ethnicity (%) | >0.99 (NS) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 11 (48) | 15 (47) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 12 (52) | 17 (53) | |

| Race (%) | — | ||

| White | 19 (83) | 26 (81) | |

| Black | 3 (13) | 4 (13) | |

| Asian | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | |

| Native American | — | 1 (3) | |

| Employment (%) | 0.43 (NS) | ||

| Employed | 6 (25) | 4 (13) | |

| Unemployed | 14 (58) | 20 (63) | |

| Student | 4 (17) | 8 (25) | |

| Education level (%) | — | ||

| Primary/secondary | 10 (56) | 15 (54) | |

| Some college | 6 (33) | 9 (32) | |

| College degree | — | 3 (11) | |

| Advanced degree | 2 (11) | 1 (4) | |

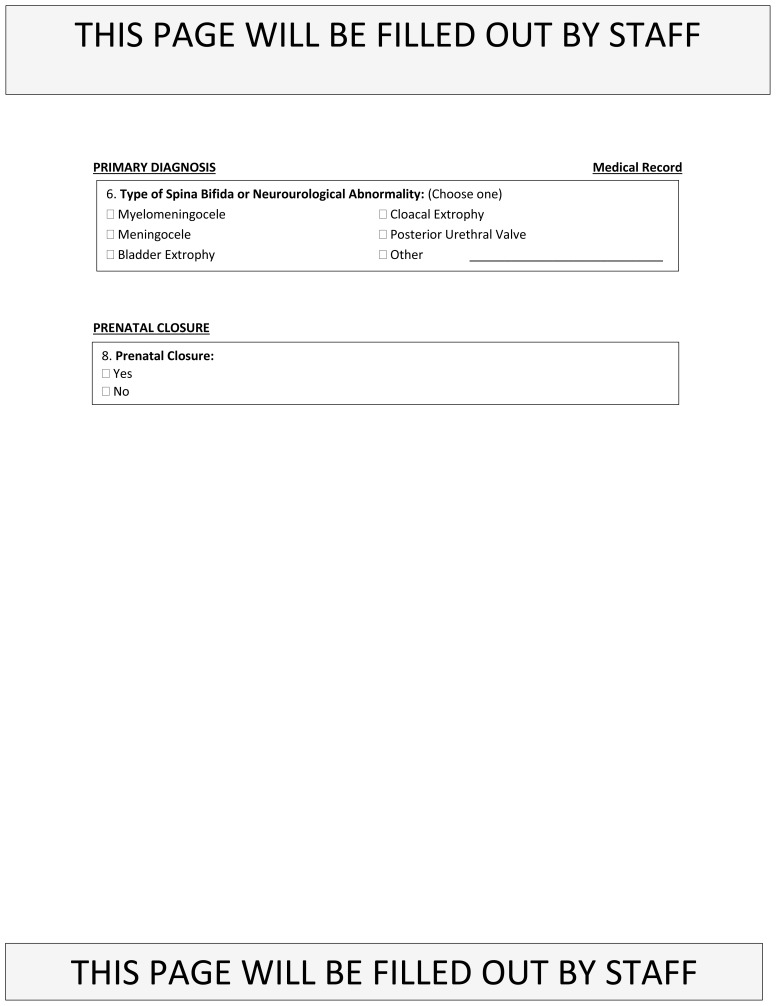

| Primary diagnosis (%) | — | ||

| Myelomeningocele | 18 (72) | 24 (69) | |

| Meningocele | 1 (4) | — | |

| Tethered cord | — | 1 (3) | |

| Sacral agenesis | 1 (4) | — | |

| Bladder exstrophy | — | 2 (6) | |

| Cloacal exstrophy | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | |

| Other* | 4 (16) | 6 (17) | |

| Shunt placement (%) | 0.27 (NS) | ||

| Yes | 19 (76) | 21 (60) | |

| No | 6 (24) | 14 (40) | |

| Self-care score (possible range: 6–42) | 40 (14–42) | 36 (16–42) | 0.28 (NS) |

| Ambulatory status (%) | 0.79 (NS) | ||

| Ambulator | 12 (55) | 17 (50) | |

| Non-ambulator | 10 (45) | 17 (50) | |

| Urinary incontinence frequency (%) | 0.82 (NS) | ||

| >1/day | 8 (38) | 8 (27) | |

| <1/day, >1/month | 5 (24) | 7 (23) | |

| <1/month (incl. never) | 5 (24) | 10 (33) | |

| Cannot assess | 3 (14) | 5 (17) |

Other includes cerebral palsy, chromosomal abnormalities, renal agenesis, Hirschsprung’s disease, etc.

Note: Proportions based on participants who provided a valid answer to that question. NS: not significant.

Males

Fertility

Seventeen of the 25 male participants (68%) responded to the fertility questionnaire (Table 2). Fifteen (88%) had a primary diagnosis of myelomeningocele, one (6%) had meningocele, and one (6%) had sacral agenesis. At the time of investigation, most men (82%) were unmarried and none had fathered biological children. None of the men had ever received fertility or conception/contraception counselling and most (65%) had never heard of assisted reproductive technologies (ART).

Table 2.

Responses to fertility and sexual function questionnaires

| Fertility questionnaire responses in all participants and in the subsets of male and female participants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Males (n=17) | Females (n=28) | ||||

| Marital status (%) | |||||

| Never married | 14 (82) | 25 (89) | |||

| Married | 2 (12) | 2 (7) | |||

| Divorced | — | — | |||

| Widowed | 1 (6) | — | |||

| Unanswered | — | 1 (4) | |||

| Previously seen obstetrics/gynecology specialist (%) | |||||

| Yes | 15 (54) | ||||

| No | 13 (46) | ||||

| Use form of birth control (%) | |||||

| Yes | 5 (29) | 11 (39) | |||

| No | 11 (65) | 16 (57) | |||

| Unanswered | 1 (6) | 1 (4) | |||

| Type of birth control (%) | |||||

| Oral contraceptive | — | 7 (25) | |||

| Intrauterine device (IUD) | — | — | |||

| Implant (Implanon) | — | 1 (4) | |||

| Barrier method (condoms) | 5 (29) | — | |||

| Other | — | 2 (7) | |||

| Do not use birth control | 11 (65) | 16 (57) | |||

| Unanswered | 1 (6) | 2 (7) | |||

| Have biological children (%) | |||||

| Yes | — | 2 (7) | |||

| No | 17 (100) | 26 (93) | |||

| Have ever received conception/fertility counselling (%) | |||||

| Yes | — | 1 (4) | |||

| No | 17 (100) | 24 (86) | |||

| Unanswered | — | 3 (11) | |||

| Have heard of assisted reproductive technology (%) | |||||

| Yes | 6 (35) | 8 (29) | |||

| No | 11 (65) | 15 (54) | |||

| Unanswered | — | 5 (18) | |||

|

| |||||

| Sexual function questionnaire responses in all participants and in the subsets of SB, male, and female participants | |||||

|

| |||||

| All subjects (n=58) | SB subjects (n=42) | Males (n=24) | Females (n=34) | p | |

|

| |||||

| History of sexual activity (%) | |||||

| Yes | 21 (36) | 17 (40) | 11 (46) | 10 (29) | 0.27 (NS) |

| No | 37 (64) | 25 (60) | 13 (54) | 24 (71) | |

| Unanswered | — | — | — | — | |

| Currently sexually active (%) | |||||

| Yes | 12 (21) | 8 (19) | 6 (25) | 6 (18) | 0.53 (NS) |

| No | 46 (79) | 34 (81) | 18 (75) | 28 (82) | |

| Unanswered | — | — | — | ||

| Desire to become/ continue being sexually active (%) | |||||

| Yes | 26 (45) | 21 (50) | 17 (71) | 9 (26) | <0.005 |

| No | 27 (47) | 18 (43) | 6 (25) | 21 (62) | |

| Unanswered | 5 (9) | 3 (7) | 1 (4) | 4 (12) | |

| Desire to learn about sexuality/fertility (%) | |||||

| Yes | 20 (34) | 17 (40) | 13 (54) | 7 (21) | <0.05 |

| No | 26 (45) | 16 (38) | 8 (33) | 18 (53) | |

| Unanswered | 12 (21) | 9 (21) | 3 (13) | 9 (26) | |

Sexual function

Twenty-four of the 25 male participants (96%) responded to the sexual function questionnaire completely (Table 2). Seventeen (71%) had myelomeningocele, one (4%) had meningocele, one (4%) had cloacal exstrophy, and five (21%) had other diagnoses. Eleven men (46%) reported a history of sexual activity, with six (25%) being currently sexually active. Most men (71%) expressed desire to become or continue being sexually active and greater than half wanted to learn more about sexuality and/or fertility.

Eleven of the 25 male participants (44%) completed the SHIM questionnaire in its entirety (Table 3). Eight (73%) had myelomeningocele, one (9%) had meningocele, one (9%) had sacral agenesis, and one (9%) had congenital Guillain-Barre syndrome. The median SHIM score was 17 (range 10–24). Of the men with spina bifida (SB), the median SHIM score was 16.5 (range 10–24). There was no significant difference between SHIM scores of men with a history of sexual activity compared to those without. No diagnosis was obviously associated with lower SHIM scores; however, the ability to recognize associations was limited by the small size — the Mann-Whitney U-test is invalid if either group has less than five samples. Similarly, no relationship between the level of the myelomeningocele and SHIM score could be detected due to the small sample size. One would assume a high level of myelomeningocele would be associated with a low SHIM score, but further testing is needed to support this assumption. Four men (16%) partially completed the SHIM questionnaire, so a composite score could not be calculated. The remaining male participants (40%) left the questionnaire blank because they were uncomfortable answering the questions. Research coordinators offered help, but these participants refused to answer personal information regarding sexual function.

Table 3.

Responses to validated questionnaires: SHIM and BISF-W

| SHIM scores and descriptive statistics (median and range) in all men and in the subsets of men with and without a sexual history | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| All men (n=11) | With sexual history (n=6) | Without sexual history (n=5) | p | ||

| SHIM score (%) | |||||

| ≥22, No ED | 1 (9) | 1 (17) | — | ||

| 17–21, Mild ED | 5 (45) | 3 (50) | 2 (40) | ||

| 12–16, Moderate to mild ED | 4 (36) | 2 (33) | 2 (40) | ||

| 8–11, Moderate ED | 1 (9) | — | 1 (20) | ||

| 1–7, Severe ED | — | — | — | ||

| Descriptive statistics | 0.14 (NS) | ||||

| Median | 17 | 17 | 14 | ||

| Range | 10–24 | 15–24 | 10–18 | ||

|

| |||||

| Descriptive statistics (median and range) for BISF-W D1, D2, D4, and D5 scores in all women and in the subsets of women with partners and without partners | |||||

|

| |||||

| Dimension | Descriptive statistics | All women | With partners | Without partners | p |

|

| |||||

| D1: Thoughts/desire (n=25) | Median | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Possible score range: 0–12 | Range | 0–9 | 1–9 | 0–6 | |

| D2: Arousal (n=25) | Median | 0 | 4 | 0 | <0.002 |

| Possible score range: 0–8 | Range | 0–5 | 0–5 | 0–4 | |

| D4: Receptivity/initiation (n=24) | Median | 0 | 5 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Possible score range: 0–10 | Range | 0–10 | 0–10 | — | |

| D5: Pleasure/orgasm (n=24) | Median | 0 | 4 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Possible score range: 0–8 | Range | 0–6 | 0–6 | 0–1 | |

BISF-W: Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women; ED: erectile dysfunction. SHIM: Sexual Health Inventory for Men.

Females

Fertility

Twenty-eight of the 35 female participants (80%) responded to the fertility questionnaire (Table 2). Nineteen (68%) had a primary diagnosis of myelomeningocele, two (7%) had cloacal exstrophy, one (4%) had bladder exstrophy, one (4%) had tethered cord syndrome, and five (18%) had other diagnoses. At the time of investigation, most women (89%) were unmarried. The two married women were the only participants who had been pregnant and given birth to children, both via cesarean section. Both women had myelomeningocele.

Almost half of the women had never seen an obstetrics/gynecology specialist. Previously visiting an obstetrics/gynecology specialist was associated with higher rates of birth control use (p<0.005). Only one woman reported previously receiving any form of fertility or conception/contraception counselling by a healthcare provider. Most women (54%) had never heard of ART.

Sexual function

Thirty-four of the 35 female participants (97%) responded to the sexual function questionnaire (Table 2). Twenty-four (71%) had myelomeningocele, two (6%) had cloacal exstrophy, two (6%) had bladder exstrophy, one (3%) had tethered cord syndrome, and five (15%) had other diagnoses. Ten women (29%) reported a history of sexual activity, with six (18%) being currently sexually active. Nine (26%) expressed desire to become or continue being sexually active, and seven (21%) wanted to learn more about sexuality and/or fertility.

Twenty-eight of the 35 female participants (80%) responded to the BISF-W questionnaire, but only three (9%) completed it in its entirety despite assistance from research coordinators. Female participants were generally hesitant to respond to the BISF-W and left questions unanswered due to discomfort with question content. Of the three who completed the questionnaire, two had myelomeningocele and one had a chromosomal abnormality. Eight (29%) women reported currently having a sexual partner, with five (18%) being sexually active in the past month. Twelve women (43%) answered questions pertaining to sexual orientation. A mixture of both heterosexual and homosexual desires and experiences were reported.

The remaining BISF-W questions are divided into the seven dimensions. Of the dimensions, D1: Thoughts/Desire and D2: Arousal had the highest response rate (n=25, 89%). Response rates for D4: Receptivity/Initiation and D5: Pleasure/Orgasm were comparable (n=24, 86%). Descriptive statistics of the D1, D2, D4, and D5 scores are given in Table 3.

The remaining domains (D3: Frequency of Sexual Activity, D6: Relationship Satisfaction, and D7: Problems Affecting Sexual Function) had poor response rates ranging from 18–43%. The nine women (32%) who responded to D3 reported engaging in a mixture of erotic kissing, masturbation alone, and vaginal penetration during the last month. Of the twelve women (43%) who responded to D6, eight (67%) had sexual partners and reported a fairly high level of personal and partner satisfaction with their sexual relationship (median 5, range 3–8, possible score range: 0–8). Of the five women (18%) who responded to D7, one (20%) reported occasional involuntary urination during sexual activity and only one (20%) reported that her health problems influenced her level of sexual activity.

All subjects

Table 4 compares characteristics between participants with and without a history of sexual activity. The median age of participants with a history of sexual activity was significantly greater than those without. No significant difference was found between those with or without a sexual history regarding extent of physical disability, degree of urinary incontinence, and hydrocephalus status. Additionally, no association was found between use of birth control and history of sexual activity.

Table 4.

Age, self-care score, ambulatory status, incontinence frequency, hydrocephalus status, and birth control use in participants with versus without sexual history

| With sexual history | Without sexual history | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 28 (19–75) | 22 (18–41) | <0.01 |

| Self-care score | 41 (19–42) | 34.5 (16–42) | 0.06 |

| (possible range: 6–42) | (NS) | ||

| Ambulatory status (%) | |||

| Ambulator | 12 (60) | 15 (44) | 0.40 |

| Non-ambulator | 8 (40) | 19 (56) | (NS) |

| Incontinence frequency (%) | |||

| >1/day | 5 (25) | 10 (33) | 0.29 |

| <1/day, >1/month | 5 (25) | 7 (23) | (NS) |

| <1/month (including never) | 4 (20) | 10 (29) | |

| Cannot assess | 6 (30) | 3 (10) | |

| Shunt placement (%) | |||

| Yes | 6 (29) | 16 (44) | 0.27 |

| No | 15 (71) | 20 (56) | (NS) |

| Birth control use | |||

| Yes | 7 (44) | 9 (33) | 0.49 |

| No | 9 (56) | 18 (67) | (NS) |

Note: Proportions based on participants who provided a valid answer to that question.

Discussion

This is the third study to use validated questionnaires in the assessment of sexual function in a cohort of male and female patients with spinal dysraphsim, but it is the first study to also include adults with other congenital genitourinary abnormalities. Given the limited amount of objective data, our study aimed to contribute to and expand upon the findings of other studies.10,14 We also included data regarding sexual knowledge, partnership, and fertility.

Fertility

In our study of adult CGUA patients, most participants were unmarried with no biological children. Almost half of female participants had never been to an obstetrics/gynecology specialist and only one participant in the entire cohort had ever received any fertility or conception/contraception counselling. Despite the increasing popularity and public awareness of ART, the majority (58%) of participants had never heard of it, including in vitro fertilization. These findings show that adults with CGUA generally lack knowledge about reproductive health despite being sexually active.

Sexual function

Of our cohort of adult patients with CGUA, 36% reported a history of sexual activity, with 21% being currently sexually active. These proportions are similar to those observed in SB patients by Lassmann et al.10 The median age of participants with no sexual history was 22 years. Thus, this patient population is delayed compared to their anatomically normal peers. In a recent national survey, 46% of teenagers aged 15–19 years reported a history of sexual activity19 and the World Health Organization found the median age of first sexual intercourse to be 17.4 years in the U.S.20

As observed by Lassmann et al, sexual activity in our study cohort was unrelated to extent of disability and degree of urinary incontinence.10 Other studies have reported that the prevalence of hydrocephalus is lower in patients who are sexually actives;13,21 however, we found no association between sexual activity and hydrocephalus status. This discrepancy in results may be partly explained by our exclusion of patients with high dependence of care and poor cognitive ability, making our study population more functional in comparison.

There was no difference in gender distribution among sexually active patients, in accordance with Lassmann et al.10 However, males expressed a significantly greater interest in learning about sexuality and/or fertility compared to females. Males were also significantly more interested in becoming sexually active or continuing sexual activity. Given that males have a much stronger libido than females,22 this disparity in sexual interest and desire is not unusual.

In our study, no male participant had a SHIM score corresponding to ED. The median SHIM score was 17, which indicates mild ED. Lee et al observed the contrary, where most male participants were categorized as having severe ED, and the median SHIM score was 5. Our sample population was similar to that of Lee et al regarding ambulatory and hydrocephalus status. While our response rate for the SHIM questionnaire was poor, it was comparable to that of Lee et al.14 We observed no association between SHIM score and sexual activity.

Most female participants who responded to the BISF-W questionnaire reported satisfaction in their sexual relationships and denied that their personal health or urinary incontinence interfered with sexual activity. However, the small sample size limits generalizability of results. Like that of the SHIM questionnaire, the BISF-W response rate was poor, with only three women completing it in its entirety despite in-person assistance from research coordinators. However, the BISF-W is a much more comprehensive questionnaire compared to the SHIM, so the lower response rate is understandable. The lower response rates for different domains may be due to proximity to the end of the survey or related to embarrassment about answering the questions.

Our findings suggest that health status might not affect sexual function in adults with CGUA to the degree suggested in the literature. Their delay in sexual activity may be more attributed to a lack of education or opportunity. Social stigma of disability also likely influences how this patient population views and pursues sexual activity.

Overall

Our study found that adult patients with CGUA are generally interested in sexuality and fertility, yet they lacked knowledge about these topics. Regardless of gender, over half of participants had never heard of ART, and only one had received prior fertility or conception/contraception counselling. One-third of participants wanted to learn more about sexuality and/or fertility and almost one-fourth of participants were not currently sexually active but wanted to become sexually active in the future.

A possible explanation for the discrepancy between participants’ knowledge of and desire to learn about sexuality and fertility could be the lack of education provided by healthcare professionals or through the school system. Studies have shown that only 5–47% of adults with spinal dysraphism have discussed sexuality with a physician.8,11,12,21 Of the adults who had not spoken with a physician, Sawyer et al found that 93% “would [have] definitely” discussed these issues had the conversation been initiated by their doctor.8 Furthermore, while most adults with spinal dysraphism receive general sexual education in school, only a small fraction report receiving sexual education specific to their diagnoses.8 Healthcare providers are the best source for this disease-specific sexual education.

A considerable challenge of this study was getting participants to complete questionnaires pertaining to their sexuality and fertility status. Despite assistance with filling out questionnaires, many participants still left them unanswered. Questions pertaining to subjective desires and interests as opposed to objective facts were left blank more often. This poor response rate could reflect participants’ discomfort addressing sexuality and fertility in a healthcare setting. Discussion of these issues early in adolescence is recommended to promote patient comfort with sexuality and fertility.23

Furthermore, the validated sexual function questionnaires had significantly lower response rates than the questionnaires addressing fertility, partnership, and other aspects of reproductive function. This could be due to the format of answer choices. Participants were much more likely to respond to questions with yes/no answer choices as opposed to multiple-choice questions. With these considerations in mind, improvement of the current standard sexuality questionnaires is highly needed. Disease-specific questionnaires may be warranted to better assess sexual function in certain patient populations, and answer choices should be simplified when possible to increase response rates.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Cognitive problems in the spinal dysraphism population have been reported in the literature, but no intelligence test was administered prior to enrollment in the study. Rather a self-report questionnaire was used to assess education level. Additionally, some participants received help from their parents in filling out questionnaires, which may have influenced their responses. Also, the only validated questionnaires used in the study were the SHIM and BISF-W. The questionnaires used to assess fertility, partnership, and other aspects of reproductive function were not validated. Finally, an important limitation was our small sample size and select patient population. While our sample size was comparable to those of previous studies in this patient population, it limits the generalizability of results and could be improved with future multi-institutional studies.

Conclusion

For the millennial patients, health status might not affect sexual function in adults with CGUA to the degree suggested in the literature. Their delay in sexual activity may be more attributed to a lack of education or opportunity. While adults with CGUA desire more sexuality and fertility education, they are uncomfortable addressing these sensitive topics in our current healthcare environment. This study revealed a need for medical providers to discuss sexual and reproductive health with adult CGUA patients earlier and in more detail. Additionally, current sexuality questionnaires are difficult for this patient population to complete despite assistance. Modifications are needed. Disease-specific questionnaires may be warranted to better assess certain patient populations.

Acknowledgements

Rose Khavari is a scholar supported in part by NIH grant K12 DK0083014, the Multidisciplinary K12 Urologic Research (KURe) Career Development Program to Dolores J Lamb (DJL) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institutes of Health.

Appendix 1. For Female Patients

Appendix 2. For Male Patients

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors report no competing personal or financial interest related to this work.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Parker SE, Mai CT, Canfield MA, et al. Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004–2006. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88:1008–16. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams J, Mai CT, Mulinare J, et al. Updated estimates of neural tube defects prevented by mandatory folic acid fortification – United States, 1995–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monga M, Alexandrescu B, Katz SE, et al. Impact of infertility on quality of life, marital adjustment, and sexual function. Urology. 2004;63:126–30. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ventegodt S. Sex and the quality of life in Denmark. Arch Sex Behav. 1998;27:295–307. doi: 10.1023/A:1018655219133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diamond DA, Rickwood AMK, Thomas DG. Penile erections in myelomeningocele patients. BJU Int. 1986;58:434–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1986.tb09099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cass AS, Bloom BA, Luxenberg M. Sexual function in adults with myelomeningocele. J Urol. 1986;136:425–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)44891-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decter RM, Furness PD, Nguyen TA, et al. Reproductive understanding, sexual functioning and testosterone levels in men with spina bifida. J Urol. 1997;157:1466–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)65025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawyer SM, Roberts KV. Sexual and reproductive health in young people with spina bifida. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41:671–5. doi: 10.1017/S0012162299001383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamé X, Moscovici J, Gamé L, et al. Evaluation of sexual function in young men with spina bifida and myelomeningocele using the International Index of Erectile Function. Urology. 2006;67:566–70. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lassmann J, Gonzalez FG, Melchionni JB, et al. Sexual function in adult patients with spina bifida and its impact on quality of life. J Urol. 2007;178:1611–4. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardenas DD, Topolski TD, White CJ, et al. Sexual functioning in adolescents and young adults with spina bifida. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2008;89:31–5. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gatti C, Del Rossi C, Ferrari A, et al. Predictors of successful sexual partnering of adults with spina bifida. J Urol. 2009;182:1911–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gamé X, Moscovici J, Guillotreau J, et al. Sexual function of young women with myelomeningocele. J Ped Urol. 2014;10:418–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee NG, Andrews E, Rosoklija I, et al. The effect of spinal cord level on sexual function in the spina bifida population. J Ped Urol. 2015;11:142–e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi EK, Ji Y, Han SW. Sexual function and quality of life in young men with spina bifida: Could it be neglected aspects in clinical practice? Urology. 2017;108:225–32. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, et al. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor JF, Rosen RC, Leiblum SR. Self-report assessment of female sexual function: Psychometric evaluation of the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women. Arch Sex Behav. 1994;23:627–43. doi: 10.1007/BF01541816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffer MM, Feiwell E, Perry R, et al. Functional ambulation in patients with myelomeningocele. JBJS. 1973;55:137–48. doi: 10.2106/00004623-197355010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez G, Abma JC. Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing of teenagers aged 15–19 in the United States. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wellings K, Collumbien M, Slaymaker E, et al. Sexual behaviour in context: A global perspective. Lancet. 2006;368:1706–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69479-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verhoef M, Barf HA, Vroege JA, et al. Sex education, relationships, and sexuality in young adults with spina bifida. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2005;86:979–87. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baumeister RF, Catanese KR, Vohs KD. Is there a gender difference in strength of sex drive? Theoretical views, conceptual distinctions, and a review of relevant evidence. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. 2001;5:242–73. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0503_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy NA, Elias ER. Sexuality of children and adolescents with developmental disabilities. Pediatrics. 2006;118:398–403. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]