Introduction

Transperitoneal laparoscopic and robotic minimally invasive techniques for the management of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) are widely used. Despite familiarity with entry techniques, intraoperative adverse events attributed to the initial entry into the abdomen do occur. Open-entry methods (Hasson technique) remain commonly used in community and academic settings owing to the confidence of avoiding and recognizing major adverse events.1 Obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of greater than 30 kg/m2, provides a technical challenge to gaining efficient open entry. Laparoscopic nephrectomy has been shown to be safe in obese populations, with an acceptable complication profile but longer operative times.2 It is not uncommon at our centre to operate on patients with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or greater. We describe the use of a traditional vaginal speculum that can be done by a single operator to aid in gaining efficient initial open access in an obese patient.

Methods

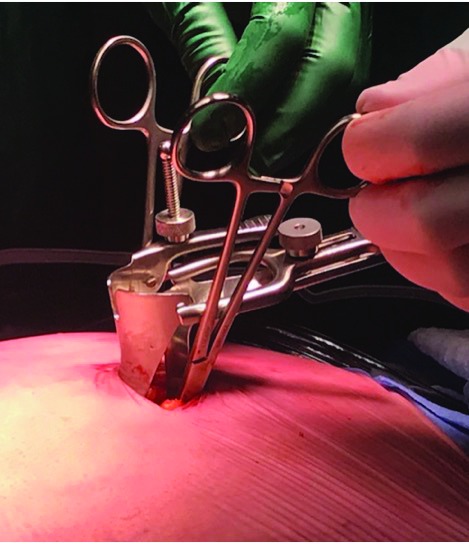

The materials used for open access in obese patients include electrocautery, pediatric vaginal speculum (Fig. 1), Kochers, polyglactin 910 (Vicryl®) stay suture, and 12 mm laparoscopic port. A skin incision is made down through subcutaneous fat, down to anterior rectus sheath, and further bluntly dissected with a vaginal speculum, which is positioned and locked into place to provide exposure (Figs.1, 2). The fascia can be easily excised, grasped with Kochers, and a Vicryl stay suture placed at the level of fascia for standard port placement. Alternatively, a balloon access port can be applied with ease as well (picture not shown). The speculum can then be used to spread muscle, expose the posterior layer of fascia, and gain entry for initial port placement. This can be done without the use of an assistant and manipulation of handheld retractors.

Fig. 1.

Pediatric vaginal speculum retracting subcutaneous fat. Kochers placed on anterior fascia prior to suture placement from outside the speculum.

Discussion

This technique can be used in obese patients undergoing laparoscopic or robotic radical or partial nephrectomy using an open-entry method of initial port placement. While we primarily use this on patients in the flank position, it can be applied to initial port placement in any transperitoneal or extraperitonal laparoascopic case. The pediatric vaginal speculum is widely available, low-cost, easily manipulated, and locked with one hand, and can be used by a single practitioner. Furthermore, it aids in the dissection of significant subcutaneous fat, aiding exposure of both anterior and posterior rectus sheath layers without the use of separate retractors.

Alternatively, for obese patients, Veress needle entry may prove to be an efficient method of entry to avoid tedious dissection. A recent Cochrane systematic review of randomized controlled trials comparing different access techniques found the use of a Veress needle was associated with an increased incidence of failed entry and extraperitoneal insufflation, but a lack of significant difference in terms of major vascular and visceral injury.3 The choice of approach is based both upon experience with initial training and preference, and many surgeons may continue with an open-access approach for the aforementioned benefits.

The only other report of an assisting speculum device was by Adshead and colleagues in 2007. They published a method of using a Killian nasal speculum for all of their initial port entries, describing quick entry with a single surgeon and usefulness in obese populations.4 In our experience, the pediatric vaginal speculum provides more visualization of the fascia layers due to its wider blades and better retraction of subcutaneous fat in the obese population.

Conclusion

We describe a pediatric vaginal speculum-assisted method of initial laparoscopic port placement using an open Hasson entry method in obese patients. This technique has been used 10 times to place the initial camera port in our obese patients (BMI range 40–51 kg/m2) during laparoscopic radical and robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy with no complications related to port placement. Our initial experience is that this technique provides quick, safe access accomplished by one surgeon compared to standard open-access techniques.

Fig. 2.

Superior view of speculum and working channel.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors report no competing personal or financial interest related to this work.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Hasson HM. Open laparoscopy. Biomed Bull. 1984;5:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arfi N, Baldini A, Decaussin-Petrucci M, et al. Impact of obesity on complications of laparoscopic simple or radical nephrectomy. Curr Urol. 2015;8:149–55. doi: 10.1159/000365707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad G, Gent D, Henderson D, et al. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD006583. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006583.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adshead J, Hanbury DH, Boustead GB, et al. Novel method for open-access laparoscopic port insertion using the Killian nasal speculum: The Lister technique. J Endourol. 2007;22:317–9. doi: 10.1089/end.2007.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]