Abstract

Background/purpose

The behavioral control of child patients is an important issue in pediatric dentistry. The emotional states of the mothers of patients may influence the attitudes of their children. The aim of this study was to investigate the emotional states estimated from physiological responses of child patients and the subjective anxieties of their mothers during dental treatments and discuss the emotional relationships between children and their mothers.

Materials and methods

To assess physiological responses associated with emotional changes induced by dental treatments in child patients aged 3–6 years, activity in the autonomic nervous were analyzed from variations in inter-beat intervals in electrocardiogram. Anxiety levels of accompanying mothers were examined using the State Trait Anxiety Inventory, which was filled out during the treatment of their child.

Results

Regarding the stress of child patients from the aspect of autonomic nervous activities during dental treatments, comparison between the cooperative and uncooperative patient groups showed that the uncooperative group demonstrated significantly higher sympathetic nervous activity and significantly lower parasympathetic nervous activity relative to the cooperative group, and their accompanying mothers showed significantly higher state anxiety scores relative to the mothers of cooperative children. Moreover, positive correlation between state anxiety scores of mothers and sympathetic nervous activities of their children was observed.

Conclusion

These results indicated that uncooperative child patients undergo more stress and their mothers feel more anxiety from dental treatments, resulting in an emotional relationship between children and their mothers, which requires dental professionals to make special considerations to calm the anxiety of the mother, as well as the stress of the child patient.

Keywords: child patient, emotion, mother, pediatric dentistry, relationship

Introduction

Providing a comfortable and safe clinical environment is essential for pediatric dentistry in order to prevent children from developing dental anxiety and/or phobias and to cultivate desirable oral health habits. Since a pediatric dental practice is generally conducted in the presence of the caregiver in Japan, the triple relationship between dental professionals, child patients, and their caregivers is important. Several studies on anxiety or fear subjectively experienced by child patients during dental treatment were performed.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Additional studies investigated the relationship between mother and child in pediatric dentistry, as well as other fields, and reported the deep and strong mental correlation between mother and child.6, 7, 8 However, most of these studies examined the subjective anxiety assessed by children themselves or by accompanying parents using psychometric scales to evaluate the internal anxiety or stress of children.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 These reports did not always reflect the internal anxiety states of child patients, because young children have difficulties in verbally expressing their feelings accurately. In order to comprehensively understand the anxiety or stress felt by children, additional objective assessment is required.

For objective assessment of internal emotion of children, several physiological responses induced by dental treatments have been utilized. As physiological responses to anxiety or stress, changes in heart rate, blood pressure, electrodermal activity, autonomic nervous activity, and salivary concentrations of cortisol and α-amylase have been measured in previous studies.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Among these factors, sympathetic nervous activities have been reported as valuable in assessing the internal stress of children, even when no expressed signs of anxiety and stress are present during dental treatment.15 Thus, in the present study, we measured the autonomic nervous activities through power spectrum analysis of the inter-beat (R-R) interval variation from electrocardiogram (ECG) and estimated the internal stress levels of child patients. Additionally, we examined the subjective anxiety levels of mothers accompanying child patients by using the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). From these objective and subjective measurements, we investigated the emotional relationships between child patients and their mothers.

Materials and methods

Participants

The participants were selected from patients registered for treatment at pediatric dental clinics in the university dental hospital. The criteria for selection were an age range of 3–6 years old and healthy, without any systemic or psychological problems and medication use. The investigation was performed between October 2013 and June 2014. Twenty-seven patients (15 males and 12 females) and their mothers participated in this study. Treatment for all patients was composite resin restoration. Out of 27 patients, 13 (6 males and 7 females) underwent treatment with restraint (uncooperative group) and 14 (9 males and 5 females) underwent treatment without restraint (cooperative group). When behavioral approaches, such as tell-show-do and distraction, were unsuccessful, passive restraint was considered, since general anesthesia or sedation is not preferred by Japanese parents. Passive restraint describes a treatment using a restraining device to stabilize patient's movement and make the practice safer. Most patients of pediatric dental clinics at our university are referred by their primary dentists and need urgent treatment, because they have strongly refused treatment and remained untreated. Therefore, the use of passive restraint is often chosen in our clinic in cases where usual behavioral control ends unsuccessfully. Table 1 summarizes the number of patients by age and two types of attitude toward treatment (cooperative and uncooperative).

Table 1.

Number of patients in each age group and in two types of attitudes toward treatment (cooperative and uncooperative).

| 3-y | 4-y | 5-y | 6-y | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperative | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 14 |

| Uncooperative | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Total | 15 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 27 |

Measurement of autonomic nervous activity

ECG of patients was recorded throughout the treatment to analyze the autonomic nervous response to anxiety and stress conditions. Patients were equipped with a portable ECG monitor (Active Tracer AC-301A; GMS Co., Tokyo, Japan) immediately after lying on the dental chair for treatment. The ECG of the patient was recorded once in the early stage of treatment. The variations of separate R-R intervals in ECG were analyzed with the software MemCalc/Win version 2 (Tarawa; GMS Co.), which outputs the power of two specific bands through power-spectral analysis. One is a high-frequency band (HF; 0.15–0.4 Hz), which signifies parasympathetic nervous activity, and the other is a low-frequency band (LF; 0.04–0.15 HZ), which reflects both parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous activities. The LF/HF ratio was recorded as a specific marker of sympathetic nervous activity.9

Questionnaire study on anxieties of mothers

Twenty-seven mothers whose children participated in the ECG study participated in the questionnaire study. The anxiety of mothers was measured using the STAI, which they completed while their children underwent treatment. The STAI is a psychological inventory based on a 4-point Likert scale and consists of 40 questions. The STAI evaluates two types of anxiety: event-related (state) anxiety and trait anxiety that reflects personal features.16

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS version 21 (Japan IBM Co., Tokyo, Japan). Student t test was used to assess the differences between two groups. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the relationship between autonomic nervous activities of children and the anxiety levels of mothers. Statistical significance was determined as P < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This study was performed after all parents of child patients gave informed consent for the research. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Dentistry, Tokyo Medical and Dental University (Tokyo, Japan; approval number 976).

Results

Characteristics of autonomic nervous system activities of child patients

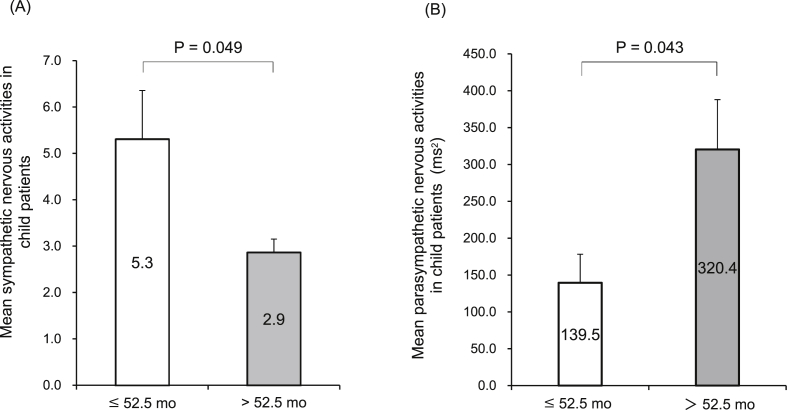

No significant difference was observed between boys and girls regarding either sympathetic or parasympathetic nervous activity. When the children were divided into younger and older age groups based on the average age, the mean sympathetic activity of the younger group was significantly higher than the older group (P = 0.049), and the mean parasympathetic nervous activity of the younger group was significantly lower as compared with the older group (P = 0.043; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the mean (A) sympathetic nervous and (B) parasympathetic nervous activities between younger and older patient groups. The error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

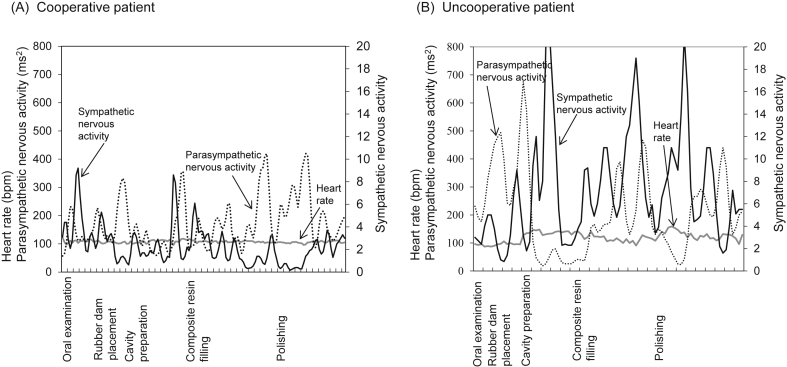

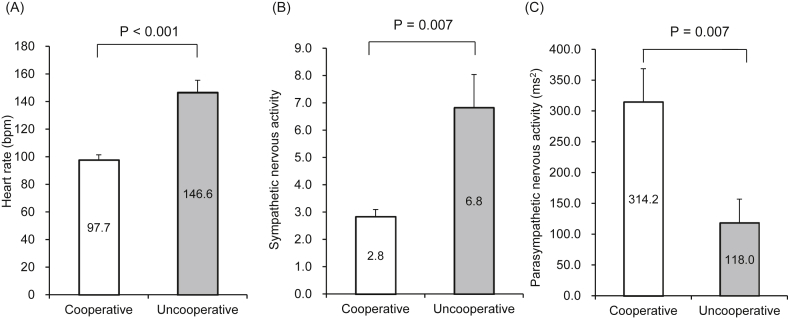

Furthermore, when the children were divided into cooperative and uncooperative groups based on the attitudes to dental treatment, differences in autonomic nervous activities were observed between the two groups. Examples of autonomic nervous activities and heart rates associated with a cooperative and uncooperative child are illustrated in Figure 2. The treatments for these patients were performed by the same dentist. The uncooperative child demonstrated much higher sympathetic nervous activity and a higher heart rate as compared with the cooperative child. As shown in Figures 3A and 3B, the mean heart rate and sympathetic nervous activity of the uncooperative group were significantly higher relative to the cooperative group (heart rate, P < 0.001; sympathetic nervous activity, P = 0.007). Furthermore, the mean parasympathetic nervous activity (Figure 3C) of the uncooperative children was significantly lower relative to the cooperative group (P = 0.007).

Figure 2.

Physiological responses of (A) cooperative and (B) uncooperative children during dental treatment involving composite resin restoration. Both children were treated by the same dentist.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the mean of (A) heart rate, (B) sympathetic nervous activity, and (C) parasympathetic nervous activity between cooperative and uncooperative child patients.

Relationship between autonomic nervous activities in children and anxiety levels of their mothers

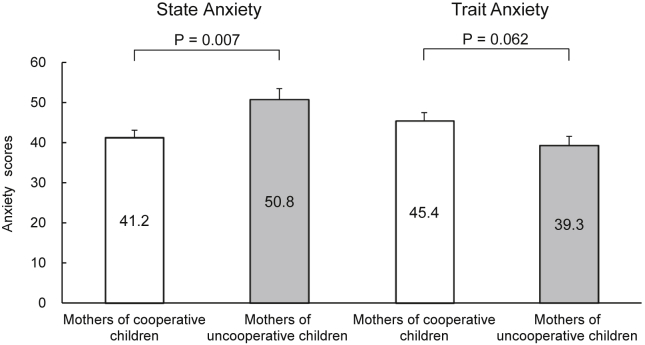

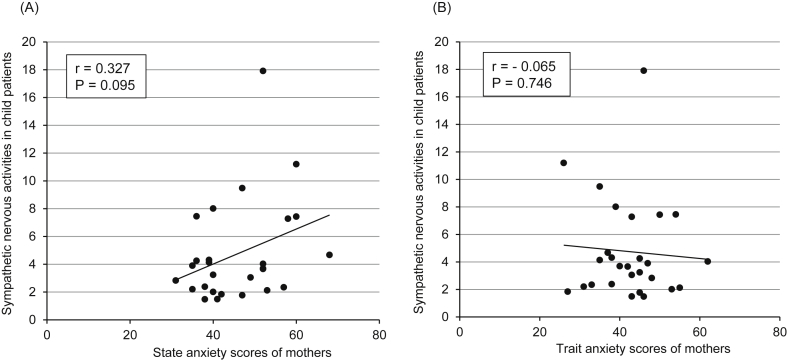

Comparison of anxiety scores between mothers of uncooperative and cooperative children demonstrated a significantly higher state anxiety score in the mothers of the uncooperative group (P = 0.007) and a tendency for a higher trait anxiety score (P = 0.062) as compared to those of the cooperative group (Figure 4). Additionally, state anxiety scores of mothers tended to positively correlate with the sympathetic nervous activities of their children (r = 0.327, P = 0.095; Figure 5A), while no correlation was found between trait anxiety scores of mothers and the sympathetic nervous activities of their children (r = −0.065, P = 0.746; Figure 5B). With regard to parasympathetic nervous activities of children, no significant correlation was observed with either state or trait anxiety scores of their mothers (state anxiety: r = −0.265, P = 0.182; trait anxiety: r = 0.190, P = 0.343).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the anxiety scores of mothers between cooperative and uncooperative child groups.

Figure 5.

Relationships between (A) state anxiety scores and (B) trait anxiety scores of accompanying mothers and the sympathetic nervous activities of their children.

Discussion

ECG monitoring in pediatric dentistry has been suggested, because it is useful for behavioral management,13, 14 based on the phenomenon that internal stress is associated with increased sympathetic nervous activity accompanied by a decrease in parasympathetic nervous activity, which in turn results in alterations in cardiac function. We previously conducted a power spectral analysis of heart-rate variability as a marker of autonomic function and revealed it to be an informative method for evaluating the internal stress induced by dental treatment.15 Here, we monitored ECGs throughout the dental treatment and analyzed the autonomic nervous response in order to objectively evaluate the anxiety or stress of child patients. The results demonstrated higher sympathetic nervous activity accompanied by lower parasympathetic nervous activity in the uncooperative group as compared with the cooperative group, suggesting that the uncooperative group felt stronger stress during dental treatments, which is consistent with our previous findings.17 In respect of patient age, the younger child patients showed higher sympathetic nervous activity, indicating that children < 4 years old easily get anxious and stressed due to limited experience with clinical situations. This result is consistent with a report that a maladapted child group at the first visit contained younger children as compared with an adaptation group.7

A few studies on mental relationships between child and mother related to dental treatment have been performed using questionnaires.6, 7 Kinjo et al6 used STAI to assess the anxiety of the mother and the Takagi-Sakamoto Personality Diagnostic Test to assess the personality of the child and observed correlations between “nervous” and “dependence” of the child and the anxiety traits of the mother.6 On the other hand, we investigated the relationship between objective stress levels of child patients and the subjective anxieties of their mothers, with results indicating significantly higher levels of state anxiety in mothers of uncooperative children and a positive correlation between the sympathetic nervous activity in child patients and subjective state anxiety levels of mothers. By contrast, for trait anxiety levels, there was no significant difference between the cooperative and uncooperative groups and no significant correlation between the sympathetic nervous activities of children and the anxiety levels of their mothers. These results suggested that the anxiety levels of the mothers may elevate irrespective of their trait anxieties during dental treatment of their children, especially in the uncooperative group, and that anxieties of the mothers may influence the stress and anxiety of the children. This result is inconsistent with the previous report by Kinjo et al,6 which demonstrated a correlation between trait anxiety of the mother and “nervous” personality of the child. The discrepancy may result from the timing of data acquisition, since the data of the previous study were collected before dental treatment, or the class of the mother, while our data were acquired during actual treatments. Another possible cause of this difference is the evaluation method. In the previous study, the personality of children was analyzed from the questionnaire answered by their mothers, while here, the stress levels of child patients were individually analyzed based on the sympathetic nervous activities. These findings suggested that the anxiety of the accompanying mother is susceptible to the influence the behavior and mental condition of her child, and that it may possibly also affect the emotional state of her child during dental treatment.

Koda et al18 reported that both subjective ratings and autonomic responses to watching videos of dental treatments were similar between children and their mothers. They investigated the emotional relationship between school children and their mothers under an empirical setting where the condition of stimulation can be well controlled. However, our patients were much younger than school children, and the data was acquired under an actual clinical setting where control of the environment is more difficult, since the assessment and control of stress and anxiety experienced by younger children is an important issue in pediatric dentistry. Even under these difficult situations, we found correlations between objectively assessed stress of child patients and the subjective anxieties of mothers. Collectively, these results suggested that dental professionals are asked for more careful explanation and approaches to remove the anxiety from mothers, as well as child patient stress, during the treatment of uncooperative child patients of younger age.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grant Number 26861778). We thank Dr. Haruko Fujita and the staffs of Department of Pediatric Dentistry of Tokyo Medical and Dental University for their help during the course of this study.

References

- 1.Frankle S.N., Shiere F.R., Fogels H.R. Should the parent remain with the children in the dental operatory? J Dent Child. 1962;29:150–163. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aartman I.H., van Everdingen T., Hoogstraten J., Schuurs A.H. Self-report measurement of dental anxiety and fear in children: a critical assessment. ASDC J Dent Child. 1998;65:252–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakai Y., Hirakawa T., Milgrom P. The children's fear survey schedule-dental subscale in Japan. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:196–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard K.E., Freeman R. Reliability and validity of a faces variation of the modified child dental anxiety scale. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007;17:281–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shinohara S., Nomura Y., Shingyouchi K. Structural relationship of child behavior and its evaluation during dental treatment. J Oral Sci. 2005;47:916. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.47.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinjo S., Maeda K., Kato K., Kikuchi K., Nishino M. Studies on cooperation-enhancing approach in dealing with children in the dental setting. 2. Mother's anxiety-trait and child’s personality. J Dent Child. 1987;25:109–118. [In Japanese; English abstract] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamauchi T., Yokoi K., Fukuta O., Tsuchiya T., Kurosu K. Study on adaptation of child for the first dental visit: Part 1 Factors influenced on the adaptation and maladaptation. J Dent Child. 1982;20:606–617. [In Japanese; English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cagiran E., Sergin D., Deniz M.N., Tanatti B., Emiroglu N., Alper I. Effects of sociodemographic factors and maternal anxiety on preoperative anxiety in children. J Int Med Res. 2014;42:572–580. doi: 10.1177/0300060513503758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen H., Matar M.A., Kaplan Z., Kotler M. Power spectral analysis of heart rate variability in psychiatry. Psychother Psychosom. 1999;68:59–66. doi: 10.1159/000012314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blomqvist M., Holmberg K., Lindblad F., Fernell E., Ek U., Dahllöf G. Salivary cortisol levels and dental anxiety in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Eur J Oral Sci. 2007;115:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCraty R., Atkinson M., Tiller W.A., Rein G., Watkins A.D. The effects of emotions on short-term power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:1089–1093. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato M., Kitamura T., Yanagida F., Yasui S., Takeyasu M., Daito M. Changes in amount of psychological palmar sweating in children at a dental office. Pediatr Dent J. 2011;21:44–48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuyama H., Yagiela J.A. Monitoring of vital signs during dental care. Int Dent J. 2006;56:102–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2006.tb00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farhat-McHayleh N., Harfouche A., Souaid P. Techniques for managing behavior in pediatric dentistry: Comparative study of live modelling and Tell–Show–Do based on children's heart rates during treatment. J Can Dent Assoc. 2009;75:238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uehara N., Takagi Y., Miwa Z., Sugimoto K. Objective assessment of internal stress in children during dental treatment by analysis of autonomic nervous activity. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2012;22:331–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Julian L.J. Measures of anxiety. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl 11):S467–S472. doi: 10.1002/acr.20561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuchihashi N., Uehara N., Takagi Y., Miwa Z., Sugimoto K. Internal stress in children and parental attitude to dental treatment with passive restraint. Pediatr Dent J. 2012;22:170–177. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koda A., Karibe H. Subjective ratings and autonomic responses to dental video stimulation in children and their mothers. Pediatr Dent J. 2013;23:79–85. [Google Scholar]