Abstract

Background/purpose

Heat treatment of nickel–titanium (NiTi) alloy produces a better arrangement of the crystal structure, thereby leading to increased flexibility and improved fatigue resistance or plastic behavior. This study aimed to assess the performance of various heat-treated NiTi rotary instruments in S-shaped resin canals.

Materials and methods

Forty S-shaped resin canals were instrumented (10/group) with either Twisted Files (R-phase), WaveOne (M-wire), Hyflex CM, or V Taper 2H (CM-wire) with the same apical size and taper (25/0.08). Each S-shaped resin canal was scanned both before and after instrumentation with microcomputed tomography. Changes in canal volume and transportation were evaluated at regular intervals (0.5 mm). Differences between instruments at the apical curve, coronal curve, and straight portion of the canals were analyzed statistically.

Results

All tested instruments caused more transportation at the coronal rather than apical curvatures, with the exception of Twisted Files for which apical transportation was the highest for any instrument or location (P < 0.05). The transportation was mostly influenced by the alloy type rather than their cross-sectional characteristics (P < 0.05). The volumetric increase after instrumentation was similar for all tested instruments at the apical curve (P > 0.05), whereas Hyflex CM created the most conservative preparations at the coronal curve (P < 0.05). At the straight portion, volumetric changes were largest for Twisted Files and smallest for V Taper 2H (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Amongst heat-treated NiTi instruments, the CM-wire based instruments created the most favorable preparations in S-shaped resin canals.

Keywords: CM-wire, micro-computed tomography, M-wire, R-phase, S-curved resin canal, transportation

Introduction

Advanced root canal preparation techniques with nickel–titanium (NiTi) rotary instruments offer the potential to avoid some of the major drawbacks of traditional instruments and devices. Attempts to develop better performing NiTi instruments have included modifications in design, mode of action, and treatment of the NiTi alloy. Recently, thermal treatment of NiTi alloys has been used to optimize their mechanical properties, and several studies have shown this to increase the flexibility of NiTi instruments.1, 2, 3

Heat treatment of conventional NiTi wires that are in the austenite phase transforms them into an intermediate R-phase between austenite and martensite.4 R-phase heat treatments used in the manufacturing of Twisted files (TF; SybronEndo, Orange, CA, USA), increases their flexibility and resistance to cyclic fatigue.5, 6 Additionally, M-wire (Dentsply Tulsa-Dental Specialties, Tulsa, OK, USA) based NiTi alloy contains portions that are in both the deformed and microtwinned martensitic, premartensitic R-phase, and are austenite whilst maintaining a pseudoelastic state.7, 8 M-wire based instruments such as WaveOne (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) exhibit improved resistance to cyclic fatigue and good torsional properties compared with conventional wire based instruments.9, 10 Most recently, controlled-memory (CM) NiTi alloys have been developed with modified phase transformation behavior due to an increase in their austenite transformation temperature. This makes the CM-wire based instruments extremely flexible, while retaining their shape memory that is typical of other NiTi instruments.11 The CM-wire based Hyflex CM (Coltene-Whaledent, Allstetten, Switzerland) and V Taper 2H (SS White Dental Inc., Lakewood, NJ, USA) were only recently released. Hyflex CM is reportedly more flexible with superior cyclic fatigue and torsional resistance than conventional NiTi instruments or M-wire based instruments.12

Accordingly, heat-treated NiTi instruments are expected to perform better by maintaining canal curvature to minimize transportation and avoid instrument separation. However, there have not been any definitive analytical studies of their shaping ability in curved canals. Therefore, this study compared various heat-treated NiTi instruments in their preparation of standardized S-shaped resin canals. The null hypothesis was that there are no significant differences in canal preparation between the different heat-treated NiTi instruments.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition

Instruments (N = 10/group) of TF (SybronEndo) for R-phase, WaveOne (Dentsply Maillefer) for M-wire, Hyflex CM (Coltene-Whaledent), and V Taper 2H (SS White Dental Inc.) for CM-wire based NiTi alloy instruments of the same apical size and taper (#25/0.08 taper) were used. They were scanned using micro-computed tomography (MCT; SkyScan 1172; SkyScan, Aartselaar, Belgium) at 80 kV and 124 μA with an isotropic resolution of 3.98 μm. Their cross-sectional configuration were analyzed at 3 mm from the instrument tip.

Standardized resin blocks (Endo Training Block-S; Dentsply Maillefer) have a simulated canal with a taper of 0.02, an apical diameter of 0.15 mm, and a length of 16 mm. The respective angles and radii of the curvatures are 30° and 5 mm for the coronal curvature, and 20° and 4.5 mm for the apical curvature. The patency of the canals was confirmed by passing a size 10 K-file just beyond the apex. They were then scanned using MCT to acquire detailed initial images at 50 kV and 200 μA, with a voxel size of 17.29 μm3.

The resin blocks were randomly assigned to four experimental groups for canal preparation. After glide-path preparation with Pathfile NiTi rotary instruments #1, 2, and 3 (Dentsply Maillefer), the canals were instrumented by using one of the tested instrument and an X-smart Plus motor (Dentsply Maillefer) as follows: WaveOne Primary, preprogrammed reciprocating motion [170° counter clockwise (CW) and 50° CW at 350 revolution per minute (rpm)]; V Taper 2H, continuous CW rotation at 300 rpm and 2.0 Nm torque; Hyflex CM and TF, continuous CW rotation at 500 rpm and 2.0 Nm torque.

All canals were prepared by the same experienced operator, with a new instrument for each canal. During instrumentation, RC-Prep (Premier Dental Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA) was used as a lubricant and saline as the irrigant. The instruments were used in a slight pecking motion (amplitude ≤ 3 mm) according to the manufacturers’ instructions, and their flutes cleaned after retrieval from the canals during instrumentation, or after three pecks. Following preparation, the canals were copiously irrigated and dried. Then they were rescanned using MCT with the same settings that were used for initial data acquisition.

Data analyses

Images at 3 mm from the tip of each instrument were analyzed. Their cross-sectional configurations were compared, and the images converted into black and white to automatically calculate cross-sectional areas using CTan software (version 1.11.0.0; Bruker-MicroCT, Contich, Belgium).

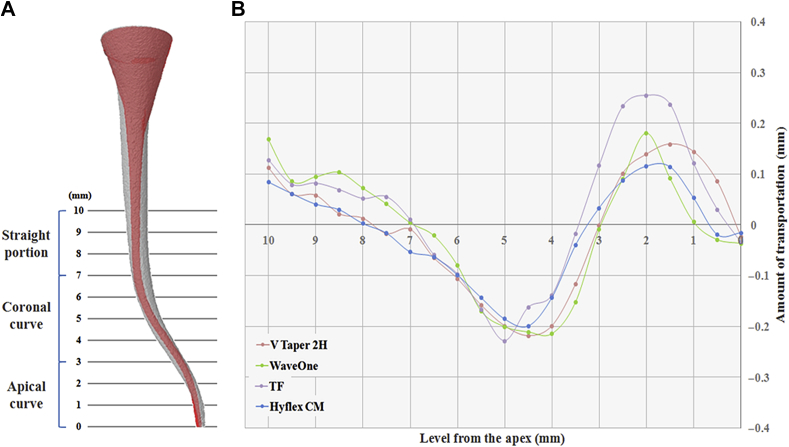

To assess the performance of the tested instruments, three-dimensional models of the canals both before and after preparation were created from the MCT data using three-dimensional modeling software CTan and CTVol (version 2.1.1.2; Bruker-MicroCT). Data were compared for canal transportation at 0.5-mm intervals, and the increase in canal volume after preparation within each independent canal region (apical curve, 0–3 mm; coronal curve, 3–7 mm; and straight portion, 7–10 mm; Figure 1A). The amount of transportation was calculated at each 0.5-mm interval by automatically plotting the canal center and measuring the differences after instrumentation. Additionally, the direction and amount of canal transportation within each region was calculated by subtracting the amount of resin removed at the inner side (concavity of the apical curvature) of the canal from the amount removed at the outer side. The volume of each canal was calculated for each independent canal region and the change in canal volume after instrumentation was expressed as a percentage.

Figure 1.

(A) Superimposed microcomputed tomographic images of initial (red) and prepared (gray) S-shaped resin canals that show the apical curve (0–3 mm), coronal curve (3–7 mm), and straight (7–10 mm) portions of the canal; (B) direction and amount of canal transportation (mm) calculated at 0.5-mm intervals along the canal. TF = Twisted File.

Statistical analysis

The normal distribution of the data was confirmed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences in the amounts of transportation, volumetric increases after instrumentation, and cross-sectional areas between instruments were examined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The amount of transportation within each independent canal region was analyzed to assess the influence of alloy type and cross-sectional characteristics using two-way ANOVA. Tukey’s test was selected for post hoc pair-wise comparisons. All analyses were performed with SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics 21; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) at a significance level of α = 0.05.

Scanning electron microscopy analyses

After canal preparation, each instrument was examined for flute deformation using scanning electron microscopy (SEM; S-4700, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The apical 10-mm segments of the tested instruments were washed in distilled water and sputter coated with platinum for SEM observation at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

Results

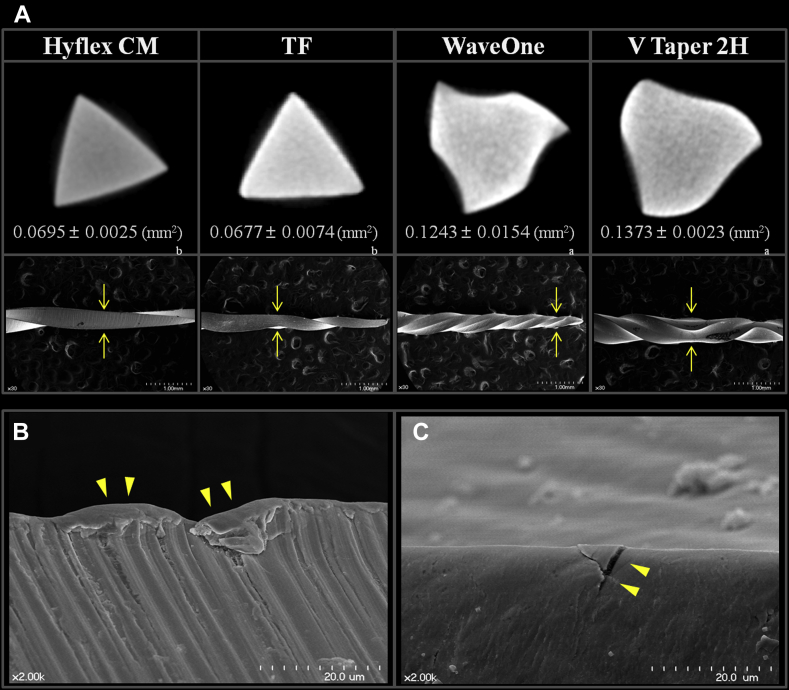

The cross-sectional configuration of the tested instruments and their cross-sectional area at a 3-mm level from the instrument tip are presented in Figure 2A. TF (0.0695 ± 0.0025 mm2) and Hyflex (0.0677 ± 0.0074 mm2) had a significantly smaller cross-sectional area than WaveOne (0.1243 ± 0.0154 mm2) and V Taper 2H (0.1373 ± 0.0023 mm2; P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

(A) Upper, cross-section images and the cross-sectional area (mm2) at a 3-mm level from the apical tip of each instrument. Microcomputed tomographic images. Lower, Scanning electron microscope images showing flute deformation (unwinding, arrow) of each instrument after canal preparation (×30); (B) scanning electron microscope images showing roll over in WaveOne (arrowheads); (C) scanning electron microscope images showing roll over in microcrack in V Taper 2H (arrowheads) found at the deformed flute area of each instrument (×20,000). Values with the same lowercase superscript letter are not significantly different (P > 0.05). TF = Twisted File.

None of the heat-treated NiTi instruments were separated during instrumentation of S-shaped resin canals. In SEM analyses, flute deformations (unwinding) were observed in all of the TF (10/10), and some of the V Taper 2H (3/10), Hyflex CM (2/10), and WaveOne (3/10) files (Figure 2A). These included a roll over for two WaveOne files and a crack for one V Taper 2H file, which were observed in their cutting blades within the deformed flute area (Figures 2B and 2C).

For all instruments there was transportation and straightening of the standardized S-shaped resin canals (Figure 1B). In all cases, transportation was directed towards the concavities of both the coronal and apical curvatures (0–0.255 mm). There was significantly more transportation at the coronal curvatures than at the apical (P < 0.05; Table 1) for all instruments, with the exception of the TF, for which apical transportation was the highest for any instruments or location (P < 0.05). Transportation at the coronal curvatures was not significantly different for the tested instruments (P > 0.05). Transportation at the apical curvatures was significantly higher for TF than for the other instruments (P < 0.05), and lowest for Hyflex CM. Transportation within the straight portion was significantly higher for TF and WaveOne than for the other instruments (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

The mean and standard deviation values of the canal transportation at each independent canal region (apical curve, coronal curve, and straight portion) of the canal pathway (mm).

| Transportation (mm)* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Apical curve | Coronal curve | Straight portion | |

| V Taper 2H | 0.098 ± 0.043 b | 0.133 ± 0.059 a | 0.048 ± 0.041 b |

| WaveOne | 0.049 ± 0.065 b | 0.132 ± 0.068 a | 0.123 ± 0.061 a |

| Twisted File | 0.138 ± 0.041 a | 0.094 ± 0.066 a | 0.118 ± 0.070 a |

| Hyflex CM | 0.043 ± 0.058 b | 0.084 ± 0.076 a | 0.047 ± 0.037 b |

* Values with the same lowercase superscript letter in each column are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

The two way ANOVA results showed that the amount of transportation was not affected by the cross-sectional area of the tested instruments (P > 0.05). However, transportation was affected by their alloy type especially at the apical curve (P < 0.001) and straight portion (P < 0.001).

The volumetric increases after canal preparation are presented in Table 2. At the apical curve, the volumetric increases after instrumentation were similar for all tested instrument (P > 0.05). At the coronal curve, Hyflex CM showed the smallest increase and the most conservative preparation (P < 0.05). Within the straight portion, the volumetric increases were largest with TF, and the smallest with V Taper 2H (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Volumetric increase of prepared canal at each independent canal region (apical curve, coronal curve, and straight portion) of the canal pathway (%).

| Volumetric increase (%)* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Apical curve | Coronal curve | Straight portion | |

| V Taper 2H | 182.8 ± 10.7 a | 327.9 ± 6.5 a | 162.0 ± 4.5 c |

| Twisted File | 175.7 ± 20.4 a | 323.6 ± 24.3 a | 249.5 ± 23.6 a |

| WaveOne | 164.7 ± 17.0 a | 315.4 ± 17.4 a | 206.5 ± 14.2 b |

| Hyflex CM | 161.3 ± 24.7 a | 284.6 ± 21.0 b | 203.2 ± 18.0 b |

* Values with the same lowercase superscript letter in each column are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Discussion

To provide an unbiased comparison of the shaping ability of various heat-treated NiTi instruments and their capacity to maintain canal curvatures, standardized clear resin blocks were used. Unlike extracted human teeth used in other studies,13 the canals simulated in resin blocks have highly standardized shape, size, taper, and curvatures, which provide a uniform and consistent experimental model to compare instrumentation techniques and devices.14, 15 This is particularly important for complex quantitative analyses of root canal preparations, which include canal transportation and volumetric changes that are feasible with MCT. However, since the mechanical characteristics of resin blocks differ from human dentin, and heat generated from instrumentation can soften resin so that it clutches the cutting blades of instruments,16 care must be taken when extrapolating these results to clinical cases.

This is the first study to have utilized MCT for analyzing instrumentation in simulated S-shaped resin canals. Our pilot study revealed that the resolution of clear resin in MCT was sufficient to compare pre- and postinstrumentation canal dimensions. Therefore, canal instrumentation was analyzed quantitatively by calculating transportation and volumetric changes in each MCT section, and their overall values within the apical curve, coronal curve, and straight portions of the canal. The accuracy and reproducibility of MCT has been verified previously,17 and it is accepted as an important scientific tool for the analysis of different root canal shaping techniques. Furthermore, this study utilized MCT for cross-sectional analyses of the instruments. Usually cross-sectional observations of endodontic instruments are performed by SEM, often following torsional fracture. However, SEM is not suitable for examining the cross-sectional area at a specific location along the instrument, because the operator cannot precisely control the cutting site, and avoid the effects of the cutting tool (e.g., disc thickness). By contrast, MCT can provide information at precise locations along an unmodified instrument, and the resolution attained in this study was sufficient to minimize marginal burnout.

Following instrumentation, the volumetric increase should theoretically be predictable from mathematical calculations. The resin canals were supposed to be size #15 with 2% taper according to their manufacturers, and they were all instrumented to an apical size #25 with 8% taper. Therefore a volumetric increase of about three- to four-fold was predicted, regardless of canal curvature. However, the actual volumetric increase in each canal region differed from the expected value for all instruments, which suggested that the initial dimensions of the resin canals differed from their manufacturer’s claims. Instead, our MCT images revealed that initial canal diameters were 0.15 ± 0.01 mm, 0.21 ± 0.01 mm, 0.23 ± 0.01 mm, and 0.36 ± 0.03 mm, at 0, 3, 7, and 10 mm, respectively, from the apex. Accordingly the calculated mean tapers were 2.27 ± 0.23 (%), 0.37 ± 0.24 (%), and 4.51 ± 1.08 (%) within the apical curve, coronal curve, and straight portions of the canal respectively. Unlike the manufacturer’s claims, these measurements of initial canal dimensions were in accordance with the volumetric increases observed.

This comparison of root canal transportation caused by various heat-treated NiTi instruments appears to be the first reported in the literature. We found that all of the instruments performed similarly within the coronal curvature (1st curved area), which is in accordance with previous studies that used simulated J-shaped canals.18, 19 However, their performance differed at the apical curve and in the straight portion of the canal. The two CM-wire based NiTi instruments created more conservative preparations in the S-shaped resin canals, regardless of their cross-sectional configuration. Their superior performance could be attributed to the effect of annealing, internal stress relaxation, smaller grain sizes, and the presence of martensite phase.11, 12 They reduce the shape memory of conventional NiTi alloy, which allows them to follow inherent canal curvature with a reduced tendency to straighten out the canal. This feature allows the creation of a more conservative shape, which respects root anatomy and maintains its original strength.

Although the instrument diameter and cross-sectional configuration are known to affect their torsional and bending behavior,20, 21 the two-way ANOVA results indicated that the shaping ability of the tested instruments were mainly affected by the type of NiTi alloy. The mechanical properties including flexibility of instruments are affected by heat treatments of NiTi alloy, which can change the phase transition temperature [e.g., austenite finishing temperature (Af)].22 Other studies reported that the Af of TF (R-phase), WaveOne (M-wire), and Hyflex (CM-wire) were 20.7°C, 50.38°C, and 50°C respectively.23, 24, 25 Similarly, our previous study showed that the Af of V taper 2H (CM-wire) is 44.95°C.26 Therefore, since NiTi instruments with lower transformation temperatures are less flexible,22 the highest transportation at the apical curve that was observed with TF may be largely due to its low Af in the present study.

Furthermore, all of the TFs showed flute deformations (unwinding), despite each being used in only a single S-shaped resin canal. Therefore we speculate that stress-induced R-phase transformation occurred when TF passed the inflection area of the S-shaped canal, in which it caused a plastic deformation under torsional stress. Additionally, the small core diameter of TF may have contributed to a lower torsional stress. By contrast, the large core diameter of WaveOne and V Taper 2H endured most of the torsional stress that would cause flute unwinding. There was only some residual stress which caused a roll over (WaveOne) or crack (V Taper 2H) within deformed flute areas of the cutting blades.

These detailed analyses of transportation and volumetric changes from canal preparation provide valuable information for instrument selection. TF tended to straighten the S-shaped resin canals by cutting into the inner surface of the curvature. Where the dentin thickness of the roots is naturally thin (e.g., mandibular molar danger zone), this amount of transportation may weaken the root or cause a strip perforation.27 WaveOne also tended to straighten the S-shaped canal as previously reported,28 but showed a more favorable preparation within the straight portion. By contrast, both of the CM-wire based NiTi instruments created conservative preparations particularly within the cervical part of the canal. These conservative preparations would preserve the integrity of root dentin, but challenge the fitting of large (8% taper) master apical cones to working length.

However, from the perspective of anticurvature techniques,29 it is sometimes necessary to reduce cervical curvature to improve access to apical curvature. In this study, none of the tested instruments have been recommended as a single-file with the exception of WaveOne, for preparing a double curved S-shaped canal. Therefore, we should be cautious in interpreting the different shaping patterns of the tested instruments, in terms of conservation of cervical root dentin versus apical transportation. As a single instrument technique, WaveOne alone showed advantageous for both aspects. However, the effects of combining different instrument sequences, instrument systems, and tapers will need to be studied further.

Canal transportation and volumetric changes from various NiTi rotary instruments could be compared quantitatively in standardized resin root canals using MCT. All of the heat-treated NiTi instruments caused transportation in S-shaped resin canals, mostly influenced by the alloy type rather than their cross-sectional characteristics. Within the limitations of this study, the two CM-wire based NiTi instruments resulted in more favorable outcomes than other heat-treated NiTi instruments in preparing simulated S-shaped resin canals, regardless of their cross-sectional configurations. WaveOne resulted in relatively conservative preparations that preserved original root curvatures, unlike TF. These results provide valuable information in selecting endodontic instruments for complex multi-curved canal systems.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Hieawy A., Haapasalo M., Zhou H., Wang Z.J., Shen Y. Phase transformation behavior and resistance to bending and cyclic fatigue of ProTaper Gold and ProTaper universal instruments. J Endod. 2015;41:1134–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayashi Y., Yoneyama T., Yahata Y. Phase transformation behaviour and bending properties of hybrid nickel-titanium rotary endodontic instruments. Int Endod J. 2007;40:247–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yahata Y., Yoneyama T., Hayashi Y. Effect of heat treatment on transformation temperatures and bending properties of nickel-titanium endodontic instruments. Int Endod J. 2009;42:621–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2009.01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otsuka K., Ren X. Physical metallurgy of Ti-Ni-based shape memory alloys. Prog Mater Sci. 2005;50:511–678. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopes H.P., Gambarra-Soares T., Elias C.N. Comparison of the mechanical properties of rotary instruments made of conventional nickel-titanium wire, M-wire, or nickel-titanium alloy in R-phase. J Endod. 2013;39:516–520. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ha J.H., Kim S.K., Cohenca N., Kim H.C. Effect of R-phase heat treatment on torsional resistance and cyclic fatigue fracture. J Endod. 2013;39:389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alapati S.B., Brantley W.A., Iijima M. Metallurgical characterization of a new nickel-titanium wire for rotary endodontic instruments. J Endod. 2009;35:1589–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson E., Lloyd A., Kuttler S., Namerow K. Comparison between a novel nickel-titanium alloy and 508 nitinol on the cyclic fatigue life of ProFile 25/.04 rotary instruments. J Endod. 2008;34:1406–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Hadlaq S.M.S., AlJarbou F.A., AlThumairy R.I. Evaluation of Cyclic Flexural Fatigue of M-Wire nickel-titanium rotary instruments. J Endod. 2010;36:305–307. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao Y., Shotton V., Wilkinson K., Phillips G., Ben Johnson W. Effects of raw material and rotational speed on the cyclic fatigue of profile vortex rotary instruments. J Endod. 2010;36:1205–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen Y., Zhou H.M., Zheng Y.F., Campbell L., Peng B., Haapasalo M. Metallurgical characterization of controlled memory wire nickel-titanium rotary instruments. J Endod. 2011;37:1566–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters O.A., Gluskin A.K., Weiss R.A., Han J.T. An in vitro assessment of the physical properties of novel Hyflex nickel-titanium rotary instruments. Int Endod J. 2012;45:1027–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2012.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saber S.E., Nagy M.M., Schafer E. Comparative evaluation of the shaping ability of ProTaper Next, iRaCe and Hyflex CM rotary NiTi files in severely curved root canals. Int Endod J. 2015;48:131–136. doi: 10.1111/iej.12291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dummer P.M., Alodeh M.H., al-Omari M.A. A method for the construction of simulated root canals in clear resin blocks. Int Endod J. 1991;24:63–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1991.tb00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weine F.S., Kelly R.F., Lio P.J. The effect of preparation procedures on original canal shape and on apical foramen shape. J Endod. 1975;1:255–262. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(75)80037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kum K.Y., Spangberg L., Cha B.Y. Shaping ability of three ProFile rotary instrumentation techniques in simulated resin root canals. J Endod. 2000;26:719–723. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200012000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gergi R., Osta N., Bourbouze G., Zgheib C., Arbab-Chirani R., Naaman A. Effects of three nickel titanium instrument systems on root canal geometry assessed by micro-computed tomography. Int Endod J. 2015;48:162–170. doi: 10.1111/iej.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva E.J., Tameirao M.D., Belladonna F.G., Neves A.A., Souza E.M., De-Deus G. Quantitative transportation assessment in simulated curved canals prepared with an adaptive movement system. J Endod. 2015;41:1125–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ersev H., Yilmaz B., Ciftcioglu E., Ozkarsli S.F. A comparison of the shaping effects of 5 nickel-titanium rotary instruments in simulated S-shaped canals. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:e86–e93. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berutti E., Chiandussi G., Gaviglio I., Ibba A. Comparative analysis of torsional and bending stresses in two mathematical models of nickel-titanium rotary instruments: ProTaper versus ProFile. J Endod. 2003;29:15–19. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu X., Eng M., Zheng Y., Eng D. Comparative study of torsional and bending properties for six models of nickel-titanium root canal instruments with different cross-sections. J Endod. 2006;32:372–375. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pereira E.S., Peixoto I.F., Viana A.C. Physical and mechanical properties of a thermomechanically treated NiTi wire used in the manufacture of rotary endodontic instruments. Int Endod J. 2012;45:469–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye J., Gao Y. Metallurgical characterization of M-Wire nickel-titanium shape memory alloy used for endodontic rotary instruments during low-cycle fatigue. J Endod. 2012;38:105–107. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braga L.C., Magalhaes R.R., Nakagawa R.K., Puente C.G., Buono V.T., Bahia M.G. Physical and mechanical properties of twisted or ground nickel-titanium instruments. Int Endod J. 2013;46:458–465. doi: 10.1111/iej.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen Y., Coil J.M., Zhou H., Zheng Y., Haapasalo M. HyFlex nickel-titanium rotary instruments after clinical use: metallurgical properties. Int Endod J. 2013;46:720–729. doi: 10.1111/iej.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang S.W., Shim K.S., Kim Y.C. Cyclic fatigue resistance, torsional resistance, and metallurgical characteristics of V taper 2 and V taper 2H rotary NiTi files. Scanning. 2016 doi: 10.1002/sca.21301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J.K., Yoo Y.J., Perinpanayagam H. Three-dimensional modelling and concurrent measurements of root anatomy in mandibular first molar mesial roots using micro-computed tomography. Int Endod J. 2015;48:380–389. doi: 10.1111/iej.12326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saleh A.M., Vakili Gilani P., Tavanafar S., Schafer E. Shaping ability of 4 different single-file systems in simulated S-shaped canals. J Endod. 2015;41:548–552. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abou-Rass M., Frank A.L., Glick D.H. The anticurvature filing method to prepare the curved root canal. J Am Den Assoc. 1980;101:792–794. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1980.0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]