Abstract

Objectives

The lower limit of cerebral blood flow autoregulation is the critical cerebral perfusion pressure at which cerebral blood flow begins to fall. It is important that cerebral perfusion pressure be maintained above this level to ensure adequate cerebral blood flow, especially in patients with high intracranial pressure. However, the critical cerebral perfusion pressure of 50 mm Hg, obtained by decreasing mean arterial pressure, differs from the value of 30 mm Hg, obtained by increasing intracranial pressure, which we previously showed was due to microvascular shunt flow maintenance of a falsely high cerebral blood flow. The present study shows that the critical cerebral perfusion pressure, measured by increasing intracranial pressure to decrease cerebral perfusion pressure, is inaccurate but accurately determined by dopamine-induced dynamic intracranial pressure reactivity and cerebrovascular reactivity.

Design

Cerebral perfusion pressure was decreased either by increasing intracranial pressure or decreasing mean arterial pressure and the critical cerebral perfusion pressure by both methods compared. Cortical Doppler flux, intracranial pressure, and mean arterial pressure were monitored throughout the study. At each cerebral perfusion pressure, we measured microvascular RBC flow velocity, blood-brain barrier integrity (transcapillary dye extravasation), and tissue oxygenation (reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) in the cerebral cortex of rats using in vivo two-photon laser scanning microscopy.

Setting

University laboratory.

Subjects

Male Sprague-Dawley rats.

Interventions

At each cerebral perfusion pressure, dopamine-induced arterial pressure transients (~10 mm Hg, ~45 s duration) were used to measure induced intracranial pressure reactivity (Δ intracranial pressure/Δ mean arterial pressure) and induced cerebrovascular reactivity (Δ cerebral blood flow/Δ mean arterial pressure).

Measurements and Main Results

At a normal cerebral perfusion pressure of 70 mm Hg, 10 mm Hg mean arterial pressure pulses had no effect on intracranial pressure or cerebral blood flow (induced intracranial pressure reactivity = –0.03 ± 0.07 and induced cerebrovascular reactivity = –0.02 ± 0.09), reflecting intact autoregulation. Decreasing cerebral perfusion pressure to 50 mm Hg by increasing intracranial pressure increased induced intracranial pressure reactivity and induced cerebrovascular reactivity to 0.24 ± 0.09 and 0.31 ± 0.13, respectively, reflecting impaired autoregulation (p < 0.05). By static cerebral blood flow, the first significant decrease in cerebral blood flow occurred at a cerebral perfusion pressure of 30 mm Hg (0.71 ± 0.08, p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Critical cerebral perfusion pressure of 50 mm Hg was accurately determined by induced intracranial pressure reactivity and induced cerebrovascular reactivity, whereas the static method failed. (Crit Care Med 2014; 42:2582–2590)

Keywords: blood-brain barrier permeability, cerebral blood flow autoregulation, cerebral perfusion pressure, cortical microvascular shunts, hypoxia, induced cerebrovascular reactivity, induced intracranial pressure reactivity, intracranial pressure

Cerebrovascular autoregulation is the ability of the brain to maintain cerebral blood flow (CBF) despite changes in cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP), that is, mean arterial pressure (MAP) minus intracranial pressure (ICP), by dilation or constriction of cerebral blood vessels (1, 2). The critical CPP is the pressure at which CBF begins to fall after maximum cerebrovascular dilation has occurred in the face of decreasing CPP. The critical CPP is an important concept because it is the threshold clinicians use to ensure adequate cerebral perfusion under various clinical conditions including raised ICP which could decrease CPP (3).

Historically, the critical CPP was determined by decreasing MAP to lower CPP while measuring changes in CBF (1, 2). However, whether the critical CPP measured by this method is relevant to the clinical circumstance where CPP is reduced by increasing ICP was unknown.

In 1972, Miller et al (4) showed in dogs that when CPP was manipulated by increasing ICP, the critical CPP was 30 mm Hg compared to 50 mm Hg when measured by decreasing arterial pressure. Similar results were reported in nonhuman primates (5, 6) and rats (7). However, the reason for the decrease in the critical CPP by increasing ICP as opposed to decreasing MAP has remained unexplained for nearly 40 years since it was first reported.

In an earlier study, we showed in rats that a progressive increase in ICP from 10 to 50 mm Hg resulted in increased high-velocity microvascular shunt (MVS) flow (8) and hypothesized that the decrease in critical CPP at high ICP may be due to MVS flow resulting in a falsely elevated CBF at a lower CPP.

The existence of MVS in the brain was generally not recognized among cerebrovascular researchers despite considerable histologic and physiologic evidence for their existence: “red veins” upon craniotomy for an angioma (9); shunt peaks in CBF measurements by external radiation detection (10); and hyperemia in contused and infarcted brain, that is, red veins (10–13). Precapillary MVS and thoroughfare channel shunts were histologically described in human (14–16) and animal brains (17). The difficulty in acknowledging the existence of these MVS may be because their role in the pathophysiology of the brain and its transition from normal capillary flow was not understood. In an earlier study, we observed microvascular shunting when high ICP but not arterial pressure was used to lower CPP (8). We also showed that the increase in MVS at high ICP could be mitigated by increasing CPP (18).

CBF autoregulation defined by lowering MAP to measure the critical CPP would require manipulation of blood pressure to unacceptably low levels and therefore cannot be studied in patients (19) and has historically been measured in animals (1, 2). Alternative methods of evaluating CBF autoregulation include the cerebrovascular response to a vasodilatory stimulus such as Co2 (20, 21) and acetazolamide (22–24). CBF autoregulatory status is also evaluated by induced changes in arterial pressure and the CBF response as the cerebrovascular reactivity (CVRx) (3, 25). A negative or no CBF response to a transient arterial pressure increase indicates intact autoregulation and a large response indicates loss of autoregulation. A similar measurement obtained by the ICP response to spontaneous arterial pressure transients is ICP reactivity or PRx (26, 27). Based on our earlier study showing that the historic, static method of evaluating CBF autoregulation may not apply to the brain at high ICP, our aim in this study was to determine whether induced CVRx (iCVRx) and induced PRx (iPRx) using dopamine-induced MAP challenges identify different critical CPP thresholds measured by increasing ICP as opposed to decreasing MAP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Surgical Procedures

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center and done in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The procedures used in this study were previously described (8, 18). Male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 31, 300–350 g, Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were acclimated for 1 week. The rats were intubated and mechanically ventilated (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) on 2% isoflurane/30% oxygen/70% nitrous oxide anesthesia. Femoral venous and arterial catheters were inserted for fluid replacement, arterial pressure monitoring, and blood sampling. A catheter inserted into the cisterna magna was used to manipulate ICP by a reservoir of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF). Brain temperature was maintained at 37°C using an objective heating system with a temperature probe in an immersion well above the cortex (Bioptechs, Butler, PA). Body temperature was kept at 37.5°C by a homeothermic blanket system with a rectal probe (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA).

Experimental Paradigm

The rats were studied in three groups: 1) time control group (n = 12); 2) CPP-ICP group (n = 12); and 3) CPP-MAP group (n = 7) (Table 1). In the CPP-ICP group, CPP was decreased sequentially from 70 to 50 and 30 mm Hg by increasing ICP from 10 to 30 and 50 mm Hg by elevation of the ACSF reservoir connected to the cisterna magna through a catheter. Increased ICP sometimes resulted in a Cushing reflex (a sympathetic rise in arterial pressure) that was countered by withdrawal of blood while continuously monitoring arterial pressure to regulate CPP. In the CPP-MAP group, arterial blood pressure and CPP were reduced by progressive withdrawal of venous blood (3–5 mL) into a syringe with heparinized saline. CPP was maintained constant at a given level for 30 minutes, sufficient for physiological stabilization and performing iCVRx and iPRx tests.

TABLE 1.

Study Groups and Controlled Variables

| Group I (Time Control) |

Group II (CPP-ICP Group) |

Group III (CPP-MAP Group) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (Min) | MAP | ICP | CPP | MAP | ICP | CPP | MAP | ICP | CPP |

| 0 | 81.5 ± 3.5 | 10.3 ± 3.2 | 70.7 ± 2.8 | 81.4 ± 5.4 | 10.4 ± 3.2 | 70.2 ± 6.8 | 82.3 ± 6.3 | 10.4 ± 4.4 | 70.3 ± 6.1 |

| 30 | 81.3 ± 4.2 | 11.2 ± 4.3 | 72.1 ± 3.4 | 82.3 ± 9.3 | 30.1 ± 3.7 | 50.8 ± 5.4 | 63.3 ± 6.8 | 9.7 ± 3.5 | 51.4 ± 6.5 |

| 60 | 79.8 ± 71 | 10.6 ± 5.1 | 71.2 ± 6.2 | 82.7 ± 8.8 | 50.8 ± 8.3 | 30.4 ± 5.1 | 43.1 ± 6.4 | 9.3 ± 3.2 | 31.5 ± 9.0 |

CPP = cerebral perfusion pressure, ICP = intracranial pressure, MAP = mean arterial pressure.

n = 12 rats for time control and ICP groups, n = 7 for MAP group, all values are in mm Hg, mean ± sem.

Measured Variables

Induced intracranial pressure reactivity (iPRx) and induced cerebrovascular reactivity (iCVRx), microvascular RBC flow velocity and diameters, NADH autofluorescence, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability were measured at each CPP. Cortical Doppler flux was measured continuously using a single-fiber 0.8-mm diameter probe (Moor Instruments, Axminster, United Kingdom) on the temporal bone (burr hole) just beneath the optical window for microscopy. Arterial pressure, ICP, and CBF were continuously recorded using Biopac system (Goleta, CA). Arterial blood gases, hemoglobin, hematocrit, pH, glucose, and electrolytes were measured using a CG8+ cartridge (iSTAT, ABAXIS, Union City, CA) and maintained within normal limits. Variations in blood gases were adjusted by manipulation of the rate and volume of the ventilator. Base deficits less than −5.0 mEq/L were corrected by slow IV infusion of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate.

Cerebrovascular Autoregulation

Cerebrovascular autoregulatory status was evaluated by 1) static autoregulation, that is, Doppler flux CBF curves and 2) dynamic iPRx and iCVRx by IV bolus dopamine. In both the CPP-MAP and CPP-ICP groups, static CBF autoregulation was evaluated by continuous monitoring of Doppler CBF as arterial pressure was progressively reduced by phlebotomy in the CPP-MAP group or by increasing ICP by raising the ACSF reservoir in the CPP-ICP group. Dynamic iPRx and iCVRx were determined by the response of ICP or cortical Doppler flux to induced transient arterial pressure challenge, respectively. A transient increase in MAP (10.1 ± 3.2 mm Hg, 42 ± 17 s duration) was induced by IV dopamine (33 ± 12 to 69 ± 16 μg/kg). Dynamic iPRx and iCVRx were calculated as ΔICP/ΔMAP and ΔCBF/ΔMAP, respectively.

In Vivo Two-Photon Laser Scanning Microscopy

Two-photon laser scanning microscopy was done using an Olympus BX51WI microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a water-immersion LUMPlan FL/IR (Olympus) 20×/0.50W objective (8). Excitation (740 nm centerline) was provided by a Prairie View Ultima laser scan unit powered by a Millennia Prime 10W diode laser source pumping a Tsunami Ti:sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics, Mountain View, CA). Images (512 × 512 pixels, 0.15 μm/pixel) were acquired using Prairie View software (Prairie Technologies, Inc., Middleton, WI). Blood plasma was labeled by IV injection of tetramethylrhodamine isothio-cyanate-dextran (155 kDa) in saline (5% wt/vol). Tetramethyl-rhodamine fluorescence was band pass filtered at 560–600 nm. All microvessels in an imaging volume (500 × 500 × 300 μm) were scanned at each study point, measuring the diameter and blood flow velocity in each vessel (3–20 μm Ø). Capillary selection was based on tortuosity, degree of branching, diameters 3–7 μm, and RBC flow velocity less than 1 mm/s (17, 28–31). MVS were differentiated by flow velocity greater than 1 mm/s and diameters 8–20 μm as previously described (8, 18). RBC motion was measured by line scans, that is, repetitive scans along the central axis of a microvessel (8, 32). In offline analysis, 3D anatomy of the vasculature was reconstructed from planar images obtained at successive focal depths (XYZ-stack). BBB permeability was assessed by tetramethylrhodamine-dextran capillary extravasation (8). For reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), 20 planar scans of fluorescence intensity were obtained in 10 μm steps starting from the pia mater at each CPP. NADH autofluorescence was band pass filtered at 425–475 nm (8, 33). In offline analyses, average intensity was calculated from the maximal intensity projection for each CPP. Imaging data processing and analysis were done using Fiji Image J processing package (version 1.48, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were done using SigmaPlot 12.3 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). Student t test or Kolgomorov-Smirnov test was used where appropriate. Differences between groups were determined using two-way analysis of variance for multiple comparisons and post hoc testing using the Mann-Whitney U test. Bonferroni multiple-comparison test was used for post hoc analysis, where the effects of different CPP were compared. Significance level was preset to p less than 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Arterial blood gases, electrolytes, hematocrit, pH, and rectal and cranial temperatures were within normal limits without significant differences between groups. Blood glucose levels were elevated in all rats likely due to the stress of surgery and anesthesia (Table 2). Importantly, hemoglobin levels were not different between the groups since in the CPP-MAP group, phlebotomy was used to decrease MAP indicating that it was not enough to affect hemoglobin levels.

TABLE 2.

Physiologic Variables in Time Control, Cerebral Perfusion Pressure-Intracranial Pressure, and Cerebral Perfusion Pressure-Mean Arterial Pressure Study Groups

| Variables | Time Control | CPP-Intracranial Pressure Group | CPP-Mean Arterial Pressure Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rectal temperature (°C) | 37.6 ± 1.1 | 37.4 ± 1.2 | 37.5 ± 1.3 |

| Cranial temperature (°C) | 37.3 ± 1.2 | 37.6 ± 1.3 | 37.4 ± 1.4 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 272.4 ± 42.4 | 269.1 ± 44.6 | 267.3 ± 45.2 |

| Na (mM/L) | 129.1 ± 4.3 | 132.3 ± 5.6 | 130.2 ± 5.9 |

| K (mM/L) | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 5.4 ± 0.7 |

| Total Co2 (mM/L) | 23.9 ± 1.7 | 23.7 ± 1.6 | 24.9 ± 1.8 |

| Ionized calcium (mM/L) | 1.33 ± 0.07 | 1.32 ± 0.04 | 1.34 ± 0.06 |

| Hematocrit (% packed cell volume) | 41.8 ± 3.4 | 42.5 ± 4.8 | 40.1 ± 4.6 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.4 ± 2.1 | 13.5 ± 3.2 | 12.7 ± 4.1 |

| pH | 7.37 ± 0.04 | 7.34 ± 0.06 | 7.32 ± 0.08 |

| Pco2 (mm Hg) | 39.7 ± 4.1 | 39.5 ± 5.5 | 40.1 ± 6.5 |

| Po2 (mm Hg) | 121 ± 7.7 | 123 ± 6.4 | 117 ± 5.2 |

| Hco3 (mM/L) | 22.3 ± 3.2 | 22.7 ± 2.9 | 21.6 ± 3.1 |

| Base excess in extracellular fluid (mM/L) | −3.11 ± 2.4 | −3.49 ± 4.2 | −4.12 ± 5.3 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 99.1 ± 0.5 | 99.3 ± 0.6 | 99.1 ± 0.7 |

CPP = cerebral perfusion pressure.

Data are mean ± sem of three blood samples per animal taken at CCP of 70, 50, and 30 mm Hg or at same time intervals in control.

n = 12 rats for time control and intracranial pressure groups, seven for mean arterial pressure group.

Cerebrovascular Autoregulation

Static CBF Autoregulation

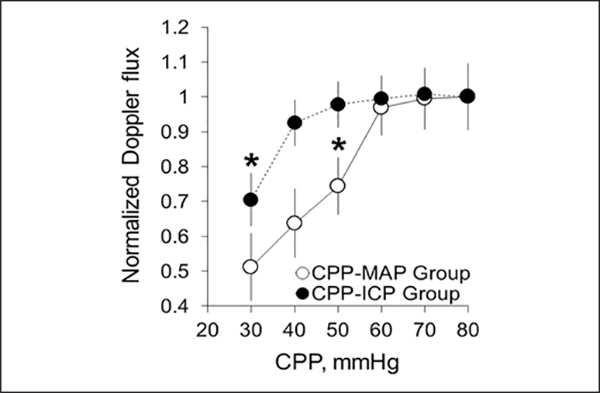

Doppler CBF measured at the cortical surface in the CPP-ICP group showed that when CPP was reduced by increasing ICP, Doppler flux fell significantly between CPP of 40 and 30 mm Hg identifying a critical CPP at high ICP of 30 mm Hg (Fig. 1, data were normalized to a baseline CPP of 70 mm Hg). At a CPP of 50 mm Hg, cortical Doppler flux was not different from CPP of 70 mm Hg (0.98 ± 0.07 vs 1.01 ± 0.06, respectively) (Table 3). In the CPPMAP group, Doppler flux fell significantly between CPP of 60 and 50 mm Hg, identifying a critical CPP of 50 mm Hg when CPP is reduced by decreasing MAP (Fig. 1 and Table 3). No change in Doppler flux was observed with time over the 4 hours in the control group (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Static autoregulation curves for cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP)-intracranial pressure (ICP) group (CPP decreased by ICP increase, n = 12 rats) and CPP-mean arterial pressure (MAP) group (CPP decreased by MAP reduction, n = 7 rats). Data were normalized to baseline CPP of 70 mm Hg obtained before any manipulation (mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05).

TABLE 3.

Cortical Doppler Flux, Induced Cerebrovascular Reactivity, and Induced Intracranial Pressure Reactivity in Time Control, Cerebral Perfusion Pressure-Intracranial Pressure, and Cerebral Perfusion Pressure-Mean Arterial Pressure Groups

| ICP, MAP, and CPP (mm Hg) | Cortical Doppler Flux | Induced Cerebrovascular Reactivity | Induced Intracranial Pressure Reactivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time control group (n = 12) | |||

| ICP 10/MAP 80/CPP 70 | 1.00 ± 0.07 | −0.02 ± 0.09 | −0.02 ± 0.06 |

| ICP 10/MAP 80/CPP 70 | 0.99 ± 0.06 | −0.02 ± 0.09 | −0.02 ± 0.06 |

| ICP 10/MAP 80/CPP 70 | 1.01 ± 0.08 | −0.02 ± 0.09 | −0.02 ± 0.06 |

| CPP-ICP group (n = 12) | |||

| ICP 10/MAP 80/CPP 70 | 1.01 ± 0.06 | −0.02 ± 0.007 | −0.03 ± 0.008 |

| ICP 30/MAP 80/CPP 50 | 0.98 ± 0.07 | 0.31 ± 0.013a | 0.24 ± 0.016a |

| ICP 50/MAP 80/CPP 30 | 0.71 ± 0.08a | 0.50 ± 0.014b | 0.33 ± 0.013b |

| CPP-MAP group (n = 7) | |||

| ICP 10/MAP 80/CPP 70 | 1.00 ± 0.09 | −0.03 ± 0.011 | −0.02 ± 0.009b |

| ICP 10/MAP 60/CPP 50 | 0.74 ± 0.08a | 0.35 ± 0.023a | 0.24 ± 0.022a |

| ICP 10/MAP 40/CPP 30 | 0.51 ± 0.09c | 0.37 ± 0.019a | 0.19 ± 0.010a |

ICP = intracranial pressure, MAP = mean arterial pressure, CPP = cerebral perfusion pressure.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Dynamic CBF Autoregulation.

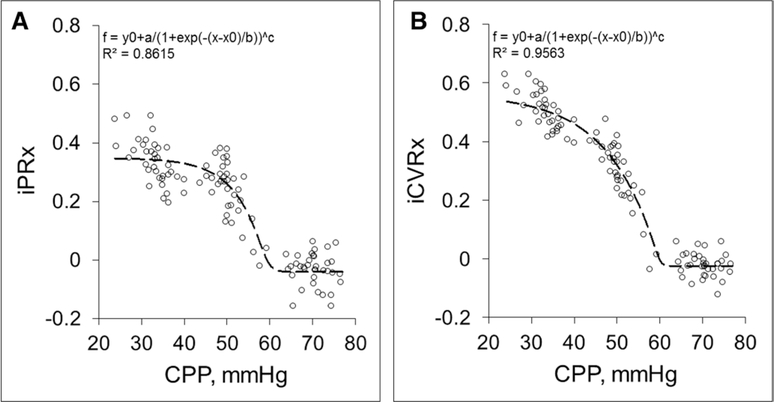

Evaluation of dynamic CBF autoregulation in the CPP-ICP group by raising ICP showed that there was no change in either iPRx or iCVRx between CPP of 80 and 60 mm Hg (Fig. 2, A and B; Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/B76 ), with average values of iPRx of –0.03 ± 0.008 and iCVRx of –0.02 ± 0.007 at a CPP of 70.2 ± 6.8 mm Hg (Table 3). After decreasing CPP below 60 mm Hg, both iPRx and iCVRx showed a steep increase in both variables (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/B76 ) but a relatively steeper increase in iPRx than iCVRx, with average values of iPRx of 0.24 ± 0.016 and iCVRx of 0.31 ± 0.013 at an average CPP of 50.8 ± 5.4 mm Hg (p < 0.05 for both) (Table 3). Below a CPP of about 50 mm Hg, both iPRx and iCVRx appeared to plateau with an average iPRx of 0.33 ± 0.013 and iCVRx of 0.50 ± 0.014 at average CPP of 30.4 ± 5.1 mm Hg (p < 0.01 for both) (Table 3). These data suggest that the critical CPP based on dynamic CBF autoregulation with high ICP is approximately 50 mm Hg in contrast to the value of 30 mm Hg derived from the static autoregulation curve.

Figure 2.

Dopamine-induced intracranial pressure reactivity (iPRx) (A) (min/max range: a [0.65, 1.95]; b [18.31, 6.10]; and c [0.00, 3.00]) and cerebrovascular reactivity (iCVRx) (B) (min/max range: a [0.75, 2.25]; b [–14.44, 4.81]; and c [0.00,3.00]) in the cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP)-intracranial pressure (ICP) group (CPP reduced by ICP elevation). Each circle represents one dopamine-induced test (nine tests per rat, total 12 rats). Trend line is the fitted sigmoidal (sigmoid, five variables) to all data points.

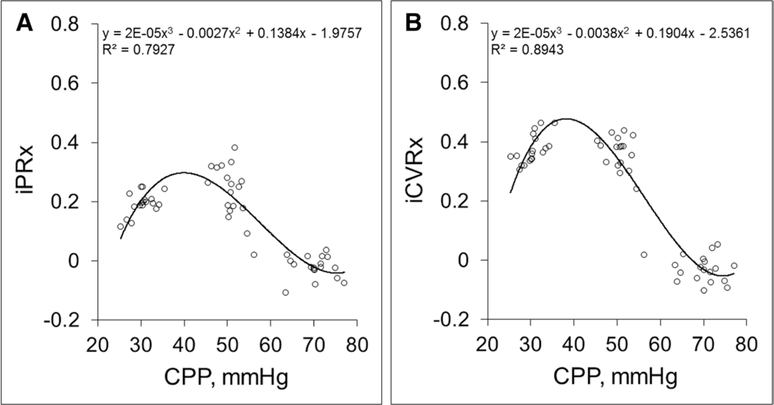

In the CPP-MAP group, the dynamic CBF autoregulation curve shows a relatively unchanged iPRx and iCVRx between CPP of 60 and 80 mm Hg (Fig. 3, A and B; and Table 3). As MAP and therefore, CPP was decreased, there was a gradual rise in iPRx and iCVRx that was significant at CPP between 50 and 60 mm Hg, suggesting a critical CPP of 50 mm Hg as obtained by decreasing CPP by MAP as shown in Figure 1 (iPRx = 0.24 ± 0.022 and iCVRx = 0.35 ± 0.023 at average CPP of 51.4 ± 6.5 mm Hg, p < 0.05 for both) (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Dopamine-induced intracranial pressure reactivity (iPRx) (A) and cerebrovascular reactivity (iCVRx) (B) in the cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP)-mean arterial pressure (MAP) group (CPP reduced by MAP decrease). Each circle represents one test (nine tests per rat, total seven rats). Trend line is the fitted polynomial (third order) to all data points.

Unlike the iPRx and iCVRx curves in the CPP-ICP group, lowering CPP below 50 mm Hg to 30 mm Hg in the CPP-MAP group resulted in a decrease in iPRx and no significant changes in iCVRx probably due to a decrease in the blood volume in the system with average value of iPRx of 0.19 ± 0.010 and iCVRx of 0.37 ± 0.019 at average CPP of 31.5 ± 9.0 mm Hg (p < 0.05 for both) (Table 3).

Microvascular Shunting, Tissue Oxygenation, and BBB Permeability

Microvascular Shunting.

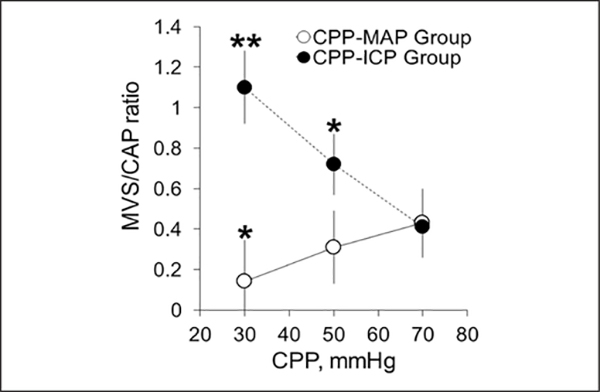

Measurements of MVS and capillary (CAP) flow were made concurrently with autoregulation status at CPP values of 70, 50, and 30 mm Hg for verification of the previously reported phenomenon (8) of increasing MVS/CAP ratio with increasing ICP and its absence with decreasing MAP (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/CCM/B77 ). The MVS/CAP ratio in the control group at a CPP of 70 mm Hg remained essentially constant with ICP kept at 10 mm Hg, MAP at 80 mm Hg, and CPP at 70 mm Hg over the 4 hours of the study (Table 4). In the CPP-ICP group, decreasing CPP to 50 and 30 mm Hg by increasing ICP to 30 and 50 mm Hg significantly increased MVS/CAP ratio at CPP of 50 mm Hg to 0.72 ± 0.15 (p < 0.05) with further increase to 1.1 ± 0.18 (p < 0.01) at 30 mm Hg (Fig. 4; and Table 4). When CPP was reduced by decreasing MAP, the MVS/CAP ratio fell at a CPP of 50 mm Hg to 0.31 ± 0.18 and to 0.12 ± 0.20 at CPP of 30 mm Hg (p < 0.01) due to decrease of blood volume and stagnation of flow in all cerebral vessels (Fig. 4 and Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Two-Photon Laser Scanning Microscopy Variables Obtained During Cortical Doppler Flux, Induced Intracranial Pressure Reactivity, and Induced Cerebrovascular Reactivity Measurements in Time Control, Cerebral Perfusion Pressure-Intracranial Pressure, and Cerebral Perfusion Pressure-Mean Arterial Pressure Groups

| ICP, MAP and CPP (mm Hg) | Microvascular Shunt Flow/Capillary Flow Ratio | Reduced Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide ΔF/Fo | Blood-Brain Barrier Damage ΔF/Fo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time control group (n = 12) | |||

| ICP 10/MAP 80/CPP 70 | 0.39 ± 0.15a | 0.01 ± 0.05a | 0.00 ± 0.31b |

| ICP 10/MAP 80/CPP 70 | 0.42 ± 0.12 | 0.00 ± 0.06 | 0.01 ± 0.30 |

| ICP 10/MAP 80/CPP 70 | 0.41 ± 0.15 | 0.02 ± 0.06 | 0.01 ± 0.32 |

| CPP-ICP group (n = 12) | |||

| ICP 10/MAP 80/CPP 70 | 0.41 ± 0.14a | 0.02 ± 0.09a | 0.01 ± 0.41b |

| ICP 30/MAP 80/CPP 50 | 0.72 ± 0.15a | 0.28 ± 0.11a | 2.24 ± 0.75b |

| ICP 50/MAP 80/CPP 30 | 1.1 ± 0.18b | 0.59 ± 0.14b | 3.89 ± 0.98c |

| CPP-MAP group (n = 7) | |||

| ICP 10/MAP 80/CPP 70 | 0.43 ± 0.17a | 0.01 ± 0.09a | 0.00 ± 0.37b |

| ICP 10/MAP 60/CPP 50 | 0.31 ± 0.18 | 0.22 ± 0.14a | 0.04 ± 0.45 |

| ICP 10/MAP 40/CPP 30 | 0.12 ± 0.20a | 0.31 ± 0.18b | 0.17 ± 0.49 |

ICP = intracranial pressure, MAP = mean arterial pressure, CPP = cerebral perfusion pressure.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Data are compared with appropriate points in time control group and within the groups (mean ± sem).

Figure 4.

Changes in microvascular shunt (MVS)/capillary (CAP) flow ratio showing that decrease of cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) by increasing intracranial pressure (ICP) resulted in a stagnation of CAP flow and an increase of MVS flow (CPP-ICP group, n = 12). The CPP decrease by mean arterial pressure (MAP) reduction reduced blood flow in all cerebral vessels (CPP-MAP group, n = 7). Mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, compared to a baseline CPP of 70 mm Hg.

Tissue Oxygenation.

Despite the difference in the response of the MVS/CAP ratio to the reduction in CPP by increasing ICP versus decreasing MAP, the response in the changes in brain tissue oxygenation, reflected by the increase in NADH, were in the same direction, significantly different from baseline NADH fluorescence at CPP of 50 mm Hg, reflecting the development of tissue hypoxia (ΔF/Fo of 0.28 ± 0.11 and 0.22 ± 0.14 for CPP-ICP and CPP-MAP group, respectively, p < 0.05 for both) (Table 4). However, the change in brain tissue oxygenation by increasing ICP reflected by NADH was nearly two-fold greater in the CPP-ICP group, possibly due to edema and BBB breakdown (8).

BBB Permeability.

The changes in BBB, reflected by transcapillary dye extravasation, showed a significant increase in the ICP group as early as at CPP of 50 mm Hg (ΔF/Fo = 2.24 ± 0.75, p < 0.01), whereas there was no change in the control group and an insignificant increase at a CPP of 30 mm Hg in the CPP-MAP group (Table 4). The more prominent BBB damage in CPP-ICP could be explained by the additional stress to capillary wall from the increased cerebral venous pressure in response to the increased ICP (34) leading to the development of vasogenic edema as we reported earlier (8).

Our results obtained concurrently with autoregulation status show that critical changes in CBF and metabolism begin to occur at CPP of 50 mm Hg in both CPP-ICP and CPP-MAP groups. However, in the CPP-ICP group, only dynamic iPRx and iCVRx showed correct cerebrovascular autoregulation threshold at 50 mm Hg correlating with physiological data, whereas static autoregulation curve shows erroneous threshold at 30 mm Hg.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that the critical CPP of 50 mm Hg determined by the historical method of static CBF autoregulation where the arterial pressure is passively decreased differs from the 30 mm Hg as determined by increasing ICP to decrease CPP. As previously discussed, this observation was initially made by Miller et al (4) in 1972 in dogs and confirmed in nonhuman primates (5, 6) and in rats (7). We previously hypothesized and have now shown that the decrease in the critical CPP determined by static CBF autoregulation when based on an increase in ICP rather than a decrease in arterial pressure is a result of the development of high flow velocity MVS maintaining a pathologically elevated CBF at CPP of 30–40 mm Hg. Our findings are important to the clinical management of patients with high ICP suggesting that the critical CPP is not lower, but in this circumstance, roughly equal to the critical CPP of the brain at normal ICP.

In an earlier study (18), we reported that dopamine was selected as the vasopressor of choice because two other vasopressors, phenylephrine and norepinephrine, resulted in severe metabolic acidosis whereas dopamine did not. As previously discussed (18), dopamine has effects on β2-adrenergic vasodilatory and α1-adrenergic vasoconstrictive receptors in cerebral blood vessels (35, 36). At low doses, dopamine induces a vasoconstrictive effect, whereas at higher doses, it induces a vasodilatory effect. At an infused dose of 100 μg/kg/min in monkeys, we reported that dopamine had no significant effect on CBF or cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen (37). In a study on patients suffering from subarachnoid hemorrhage and suspected of vasospasm, we reported that dopamine increased CBF in 90% of uninfarcted regions of the brain while decreasing CBF in a third of nonischemic territories (38). In traumatized rat brain, dopamine increased CBF in ischemic territories and did not appear to induce vasoconstriction. Our use of bolus doses of dopamine to induce a transient rise in arterial blood pressure should not induce vasoconstriction or vasodilation or alter cerebrovascular autoregulation (39).

The results also show that although static CBF autoregulation fails at high ICP, dynamic iCVRx and iPRx measurements are accurate. We surmise that static CBF autoregulation simply measures the decrease in CBF depending on the overall average flow rate through the microvasculature as an average of decreased capillary and high flow velocity MVS flow compartments. By contrast, an arterial pulse into the cerebral microvasculature will differentially impact capillaries and MVS and the response in ICP and CBF will depend on the degree of MVS or the MVS/CAP ratio, which we suggest correlates with the degree of loss of autoregulation as a fraction of capillary flow. As the MVS/CAP ratio increases, so does the proportion of tissue with loss of autoregulation as reflected by the increase in iPRx and iCVRx.

Two additional aspects of our study should be emphasized. First, the loss of CBF autoregulation that occurs in traumatized or ischemic brain with MVS differs from the loss of CBF autoregulation observed with cerebrovascular dilation by high CO2 (20, 21) or Diamox (22–24). Pharmacologically induced cerebrovascular dilation occurs by vasodilation of arteries, and arterioles, and high flow through capillaries resulting in a pressure passive relationship between CBF and CPP (1). This loss of CBF autoregulation differs from the opening of MVS and thoroughfare channels that circumvents capillaries (14). Thus, although static and dynamic autoregulation were correlated with isoflurane-induced loss of autoregulation in normal brain (40), it does not apply to the injured brain or brain at high ICP with MVS flow.

Second, a graded increase in ICP also induces a graded transition from capillary to MVS flow, which is characteristically indicative of nonnutritive flow resulting in tissue hypoxia, edema, and increased BBB permeability (8). We hypothesized that the increase in ICP results in increased cerebral venous pressure which transmits back to the capillaries causing brain edema which further increases ICP in a positive feedback loop (8, 34). The result is a separate route for blood flow, circumventing the capillaries through arteriovenous, venovenous, and arterioarterio precapillary shunts and through thoroughfare channels (14–16), resulting in capillary rarefaction as occurs in infarcted brain tissue (41–43).

The transition from capillary to MVS flow with increasing ICP provides a window into the mechanisms involved in the loss of CBF autoregulation in the injured brain (11, 12). High ICP occurs in 30% of all severe traumatic brain injury cases (44). If ICP is elevated with loss of CBF autoregulation, CPP could not be raised because a pressure passive increase in ICP could lead to brain herniation. CPP-directed therapy provides early therapeutic intervention for high ICP (45) up to CPP of 70–80 mm Hg (46). ICP-directed therapy using pharmacologic management of high ICP while keeping CPP in the range of 50–60 mm Hg was developed where increased CPP was not an option (47–49). Understanding the impact of CPP- and ICP-directed therapies on MVS flow would be of interest in the clinical management of high ICP.

CPP-directed therapy based upon the continuous measurement of PRx appears to be able to guide the setting of optimal CPP by maintaining a minimum autoregulatory index (26). However, there is a caveat because in the terminal brain where perfusion is failing and decompensated and therefore unresponsive to changes in CPP, there could be a so-called false autoregulation as observed with the no-reflow phenomenon (50, 51). Where there is complete loss of autoregulation, ICP-directed therapy becomes the only viable option in managing high ICP. In this case, CPP will be kept at 50 mm Hg while ICP is treated with vasoactive agents although low CPP is also associated with poor outcome (26).

In conclusion, the critical CPP measured by the historic CBF autoregulation curve using ICP to decrease CPP is incorrect but accurately determined by iPRx and iCVRx. The validity of the measurement of critical CPP by increasing ICP or decreasing MAP in the injured brain has yet to be determined.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Harold Nelson, biostatistician, for his input in statistical data analysis and interpretation. Data were obtained using the Optical Core of the Biomedical Research and Integrative Neuroimaging Center at the University of New Mexico.

Supported, in part, by the American Heart Association (12BGIA11730011), National Institutes of Health (NS061216 and CoBRE 8P30GM103400), Dedicated Health Research Funds from the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and China Scholarship Council Grant # 20120637504.

Dr. Bragin, Dr. Nemoto, and Ms. Statom and their institution received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and American Heart Association. Dr. Dai received support for travel and article research from the China Scholarship Council. Dr. Yonas has disclosed that he does not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal).

REFERENCES

- 1.Harper AM: The inter-relationship between aPco-2 and blood pressure in the regulation of blood flow through the cerebral cortex. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 1965; 14:94–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapela CE, Green HD: Autoregulation of canine cerebral blood flow. Circ Res 1964; 15(Suppl):205–212 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panerai RB: Assessment of cerebral pressure autoregulation in humans—A review of measurement methods. Physiol Meas 1998; 19:305–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller JD, Stanek A, Langfitt TW: Concepts of cerebral perfusion pressure and vascular compression during intracranial hypertension. Prog Brain Res 1972; 35:411–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grubb RL Jr, Raichle ME, Phelps ME, et al. : Effects of increased intracranial pressure on cerebral blood volume, blood flow, and oxygen utilization in monkeys. J Neurosurg 1975; 43:385–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston IH, Rowan JO, Harper AM, et al. : Raised intracranial pressure and cerebral blood flow. I. Cisterna magna infusion in primates. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1972; 35:285–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauerberg J, Juhler M: Cerebral blood flow autoregulation in acute intracranial hypertension. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1994; 14:519–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bragin DE, Bush RC, Müller WS, et al. : High intracranial pressure effects on cerebral cortical microvascular flow in rats. J Neurotrauma 2011; 28:775–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feindel W, Yamamoto YL, Hodge CP: Red cerebral veins and the cerebral steal syndrome. Evidence from fluorescein angiography and microregional blood flow by radioisotopes during excision of an angioma. J Neurosurg 1971; 35:167–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lassen NA, Peri W (Eds): Tracer Kinetic Methods in Medical Physiology. New York, Raven Press, 1979, pp 137–155 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly DF, Kordestani RK, Martin NA, et al. : Hyperemia following traumatic brain injury: Relationship to intracranial hypertension and outcome. J Neurosurg 1996; 85:762–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin NA, Patwardhan RV, Alexander MJ, et al. : Characterization of cerebral hemodynamic phases following severe head trauma: Hypoperfusion, hyperemia, and vasospasm. J Neurosurg 1997; 87:9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oeconomos D, Kosmaoglou B, Prossalentis A: rCBF studies in patients with arteriovenous malformations of the brain In: Cerebral Blood Flow: Clinical and Experimental Results. Chapter III, Cerebrovascular Disease. Brock M, Fieschi C, Ingvar DH, et al. (Eds). Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1969, pp 146–148 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasegawa T, Ravens JR, Toole JF: Precapillary arteriovenous anastomoses. “Thoroughfare channels” in the brain. Arch Neurol 1967; 16:217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogata J, Feigin I: Arteriovenous communications in the human brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1972; 31:519–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravens JR, Toole JF, Hasegawa T: Anastomoses in the vascular bed of the human cerebrum. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1968; 27: 123–124 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motti ED, Imhof HG, Yaşargil MG: The terminal vascular bed in the superficial cortex of the rat. An SEM study of corrosion casts. J Neurosurg 1986; 65:834–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bragin DE, Bush RC, Nemoto EM: Effect of cerebral perfusion pressure on cerebral cortical microvascular shunting at high intracranial pressure in rats. Stroke 2013; 44:177–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hlatky R, Valadka AB, Robertson CS: Analysis of dynamic autoregulation assessed by the cuff deflation method. Neurocrit Care 2006; 4:127–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lepur D, Kutleša M, Baršić B: Prospective observational cohort study of cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity in patients with inflammatory CNS diseases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2011; 30:989–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spano VR, Mandell DM, Poublanc J, et al. : CO2 blood oxygen level-dependent MR mapping of cerebrovascular reserve in a clinical population: Safety, tolerability, and technical feasibility. Radiology 2013; 266:592–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nemoto EM, Yonas H, Pindzola RR, et al. : PET OEF reactivity for hemodynamic compromise in occlusive vascular disease. J Neuroimaging 2007; 17:54–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Przybylski GJ, Yonas H, Smith HA: Reduced stroke risk in patients with compromised cerebral blood flow reactivity treated with superficial temporal artery to distal middle cerebral artery bypass surgery. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 1998; 7:302–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uchino K, Lin R, Zaidi SF, et al. : Increased cerebral oxygen metabolism and ischemic stress in subjects with metabolic syndrome-associated risk factors: Preliminary observations. Transl Stroke Res 2010; 1:178–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenthal G, Sanchez-Mejia RO, Phan N, et al. : Incorporating a parenchymal thermal diffusion cerebral blood flow probe in bedside assessment of cerebral autoregulation and vasoreactivity in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg 2011; 114:62–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aries MJ, Czosnyka M, Budohoski KP, et al. : Continuous monitoring of cerebrovascular reactivity using pulse waveform of intracranial pressure. Neurocrit Care 2012; 17:67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Budohoski KP, Czosnyka M, Smielewski P, et al. : Cerebral autoregulation after subarachnoid hemorrhage: Comparison of three methods. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 33:449–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hauck EF, Apostel S, Hoffmann JF, et al. : Capillary flow and diameter changes during reperfusion after global cerebral ischemia studied by intravital video microscopy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2004; 24:383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hudetz AG, Fehér G, Kampine JP: Heterogeneous autoregulation of cerebrocortical capillary flow: Evidence for functional thoroughfare channels? Microvasc Res 1996; 51:131–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hudetz AG, Fehér G, Weigle CG, et al. : Video microscopy of cerebrocortical capillary flow: Response to hypotension and intracranial hypertension. Am J Physiol 1995; 268:H2202–H2210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seylaz J, Charbonné R, Nanri K, et al. : Dynamic in vivo measurement of erythrocyte velocity and flow in capillaries and of microvessel diameter in the rat brain by confocal laser microscopy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1999; 19:863–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleinfeld D, Mitra PP, Helmchen F, et al. : Fluctuations and stimulus-induced changes in blood flow observed in individual capillaries in layers 2 through 4 of rat neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95:15741–15746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takano T, Tian GF, Peng W, et al. : Cortical spreading depression causes and coincides with tissue hypoxia. Nat Neurosci 2007; 10:754–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nemoto EM: Dynamics of cerebral venous and intracranial pressures. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2006; 96:435–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Essen C: Effects of dopamine on the cerebral blood flow in the dog. Acta Neurol Scand 1974; 50:39–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Overgaard CB, Dzavík V: Inotropes and vasopressors: Review of physiology and clinical use in cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2008; 118:1047–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bandres J, Yao L, Nemoto EM, et al. : Effects of dobutamine and dopamine on whole brain blood flow and metabolism in unanesthetized monkeys. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 1992; 4:250–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Darby JM, Yonas H, Marks EC, et al. : Acute cerebral blood flow response to dopamine-induced hypertension after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 1994; 80:857–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kroppenstedt SN, Stover JF, Unterberg AW: Effects of dopamine on posttraumatic cerebral blood flow, brain edema, and cerebrospinal fluid glutamate and hypoxanthine concentrations. Crit Care Med 2000; 28:3792–3798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tiecks FP, Lam AM, Aaslid R, et al. : Comparison of static and dynamic cerebral autoregulation measurements. Stroke 1995; 26:1014–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gjedde A, Kuwabara H: Absent recruitment of capillaries in brain tissue recovering from stroke. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1993; 57:35–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gjedde A, Kuwabara H, Hakim AM: Reduction of functional capillary density in human brain after stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1990; 10:317–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tomita M: Significance of cerebral blood volume In: Cerebral Hyperemia and Ischemia: From the Standpoint of Cerebral Blood Volume. Tomita M, Sawata T, Naritomi H, et al. (Eds). Amsterdam, Netherlands, Excerpta Medica, 1988, pp 3–31 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farahvar A, Gerber LM, Chiu YL, et al. : Response to intracranial hypertension treatment as a predictor of death in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg 2011; 114:1471–1478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosner MJ, Daughton S: Cerebral perfusion pressure management in head injury. J Trauma 1990; 30:933–940; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balestreri M, Czosnyka M, Hutchinson P, et al. : Impact of intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure on severe disability and mortality after head injury. Neurocrit Care 2006; 4:8–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grände PO, Asgeirsson B, Nordström CH: Volume-targeted therapy of increased intracranial pressure: The Lund concept unifies surgical and non-surgical treatments. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2002; 46:929–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nordström CH: Assessment of critical thresholds for cerebral perfusion pressure by performing bedside monitoring of cerebral energy metabolism. Neurosurg Focus 2003; 15:E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nordström CH: Physiological and biochemical principles underlying volume-targeted therapy—The “Lund concept”. Neurocrit Care 2005; 2:83–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sahuquillo J, Amoros S, Santos A, et al. : False autoregulation (pseudoautoregulation) in patients with severe head injury. Its importance in CPP management. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2000; 76: 485–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Snyder JV, Nemoto EM, Carroll RG, et al. : Global ischemia in dogs: Intracranial pressures, brain blood flow and metabolism. Stroke 1975; 6:21–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.