Abstract

Mitochondria are key organelles in regulating the metabolic state of a cell. In the brain, mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is the prevailing mechanism for neurons to generate ATP. While it is firmly established that neuronal function is highly dependent on mitochondrial metabolism, it is less well-understood how astrocytes function rely on mitochondria. In this study, we investigate if astrocytes require a functional mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) and oxidative phosphorylation (oxPhos) under physiological and injury conditions. By immunohistochemistry we show that astrocytes expressed components of the ETC and oxPhos complexes in vivo. Genetic inhibition of mitochondrial transcription by conditional deletion of mitochondrial transcription factor A (Tfam) led to dysfunctional ETC and oxPhos activity, as indicated by aberrant mitochondrial swelling in astrocytes. Mitochondrial dysfunction did not impair survival of astrocytes, but caused a reactive gliosis in the cortex under physiological conditions. Photochemically initiated thrombosis induced ischemic stroke led to formation of hyperfused mitochondrial networks in reactive astrocytes of the perilesional area. Importantly, mitochondrial dysfunction significantly reduced the generation of new astrocytes and increased neuronal cell death in the perilesional area. These results indicate that astrocytes require a functional ETC and oxPhos machinery for proliferation and neuroprotection under injury conditions.

Keywords: mitochondrial metabolism, astrocytes, stroke/photothrombotic lesion, electron transport chain, oxidative phosphorylation, reactive gliosis, Tfam

Introduction

Astrocytes are highly abundant in the brain (Nedergaard et al., 2003) and central to homeostasis of the nervous system by, e.g., regulating glutamate, ion and water homeostasis, synapse formation and modulation, tissue repair, energy storage, and defense against oxidative stress (Volterra and Meldolesi, 2005; Belanger and Magistretti, 2009). Astrocytes are also critically important for brain metabolism (Hertz et al., 2007; Belanger et al., 2011). Bridging between neurons and blood vessels, astrocytes are major components of neurovascular coupling. Fine astrocytic processes cover synaptic contacts on one side (Iadecola and Nedergaard, 2007; Oberheim et al., 2009), while on the other side, astrocyte end-feet enwrap the brain microvasculature and regulate the vascular tone as well as blood–brain function (Attwell et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2015). These morphological characteristics and a special regionalized molecular set-up allow astrocytes to sense neuronal activity at the synapse (via receptors for neurotransmitters, cytokines, growths factors, transporters, and ion channels), and react with the appropriate metabolic supply via their end-feet on the blood vessels (via glucose transporters and aquaporin 4), thereby coordinating synaptic needs and metabolic supply.

In contrast to neurons that sustain a high rate of oxidative mitochondrial metabolism, astrocytes characteristically perform glycolysis (Belanger et al., 2011). Still, astrocytes possess almost as many mitochondria as neurons (Lovatt et al., 2007), and transcriptome analysis indicated that astrocytes are equipped with the necessary molecular machinery to perform oxidative metabolism (Lovatt et al., 2007; Cahoy et al., 2008). However, it is an ongoing debate if and to which extent astrocytes in vivo perform and require oxPhos. A recent publication showed that conditional ablation of electron transport chain (ETC) neither affected long-term viability of astrocytes nor caused any obvious brain pathology (Supplie et al., 2017). An interesting question now is how astrocytes behave under stress conditions. Astrocytes have a unique capacity to adapt to conditions of metabolic challenge and are able to adjust their metabolic state to distinct injuries as assessed by transcriptome analysis (Hamby et al., 2012; Zamanian et al., 2012). Furthermore, preservation of mitochondrial respiratory function in astrocytes may be important for the brain’s energy balance and for production of antioxidants that contribute to neuronal protection (Greenamyre et al., 2003; Dugan and Kim-Han, 2004). In many neurodegenerative disorders and under injury conditions, the astrocyte’s response to injury and disease becomes increasingly recognized because astrocytes bare the potential to enhance neuronal survival and regeneration (Sofroniew and Vinters, 2010; Barreto et al., 2012).

Here, we investigated the impact of mitochondrial ETC and oxPhos in astrocytes in vivo under pathological conditions in a stroke model of photochemically initiated thrombosis (PIT). Toward this aim, we abolished ETC complexes I, III, and IV function as well as oxPhos complex V activity in astrocytes by conditional deletion of the mitochondrial transcription factor A (Tfam; Larsson et al., 1998). Deletion of Tfam did not impair survival of astrocytes but induced reactive gliosis in the cortex and led to morphological alteration of mitochondria in reactive astrocytes. Upon photothrombotic lesions, Tfam-deficiency worsened mitochondrial morphology phenotypes and impaired the generation of new astrocytes in the perilesional area. Most notably, dysfunctional mitochondrial respiration in astrocytes increased neuronal cell death in the perilesional area, indicating that astrocytes require functional mitochondrial machinery for proliferation after injury and for protecting the neurons from the damage induced by stroke.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Model and Subject Details

All experiments were carried out in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive (86/609/EEC). Animal experiments were approved by the Government of Upper Bavaria. For all experiments, mice were group housed in standard cages under a 12 h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to water and food. The astrocyte specific conditional Tfam knockout line and the control line (Tfamcko and Tfamctrl, respectively) were generated from TfamloxP/loxP mice (Larsson et al., 1998), GLAST::CreERT2 (Mori et al., 2006), CAG-CAT-EGFP reporter mice (Nakamura et al., 2006) and were described previously (Beckervordersandforth et al., 2017).

Tamoxifen Administration

Tamoxifen was dissolved at 10 mg/ml in corn oil (Sigma) and animals were intraperitonially (i.p.) injected with 1 mg on postnatal days 14, 16, and 18 (Beckervordersandforth et al., 2017).

Genotyping PCR

The following primers were used for genotyping: Tfam-A CTGCCTTCCTCTAGCCCGGG, Tfam-B GTAACAGCAGACAACTTGTG, Tfam-C CTCTGAAGCACATGGTCAAT. The expected size of PCR products for Tfamwt was 404 bp, for Tfamfloxed = 437 bp, and for Tfamcko = 329 bp.

Astrocyte Culture

Primary astrocytes were isolated as previously described (Heinrich et al., 2010). Briefly, postnatal day 5 (P5) CAG CAT GFP; Tfamfl/fl mice were decapitated and cortices were dissected in ice-cold dissection medium (HBSS with Hepes 10 mM) by carefully removing all meninges. Dissected slices were minced into small tissue pieces, and further dissociated with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette into a single cell suspension. After centrifugation (900 rcf, 5 min, RT), the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet resuspended in 10 ml astrocyte medium (DMEM/F12, 0,45% Glucose, 10%FBS, 5% horse serum, B27, 10 ng/ml EFG and FGF). Cell suspension was transferred into in a medium sized flask (10 ml, 1T75) if two brains were pooled. Cells of one brain were transferred into a small flask (5 ml, 1T25). Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Medium was changed every 4 days after shaking (200 rpm) at room tempertaure (RT) to remove unattached tissue like microglia and oligodendrocytes. Cells were passaged by trypsination when cell density reached 70% confluence. For immunostainings, cells were seeded onto PDL-coated glass cover slips. Two days after passaging, cells were transduced with HTNCre protein (1, 2, or 4 μl). For immunochemistry, cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 5 min 6 days post-transduction. For PCR, cells were trypsinized 6 days post-transduction, and DNA was isolated using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen).

FACSorting

Tfamctrl and Tfamcko animals were decapitated. The different brain areas were isolated and cut into small pieces. Tissue from one mouse was resuspended in 1 ml of enzyme mixture, incubated for maximal 25 min at 37°C, and dissociated with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette every 5 min. The enzyme mix contained 50 μl EDTA (50 mM), 50 μl L-Cystein (100 mM), 2 mg Papain, 5 mg Dispase, 2 mg DNAse I, and 167 μl MgSO4 dissolved in 5 ml HBSS, and was sterile filtrated before use. After digestion, the tissue-enzyme mix was passed through a 70 μm filter, and the filter was flushed with 2 ml DMEM/F12 (Gibco-32331) supplemented with 10% FBS. After centrifugation (1000 rcf for 3 min at RT), the pellet was resolved in 10 ml DMEM/F12 with 10% FCS. The centrifugation step was repeated and cell pellet was resuspended in 5 ml DMEM/F12 with 10% FCS mixed with 5 ml Percoll (4.5 ml Percoll in 0.5 ml 10x PBS) prior to 30 min centrifugation at 1000 rcf at RT. Then the cell pellet was washed with 1x PBS. After centrifugation (1000 rcf for 3 min at RT), the pellet was resuspended in 300 μl DMEM/F12 and passed through a 40 μm cell strainer. Recombined GFP+ astrocytes were FACSorted (BD FACS Aria in BD FACS Flow TM medium, with a sheath pressure of 70 psi and a nozzle diameter of 70 μm). DNA isolation was performed using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen).

Genotyping PCR was performed to analyze recombination of the Tfam locus.

Tissue Processing

Animals were sacrificed using CO2. Mice were transcardially perfused with 50 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) followed by 100 ml 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at a rate of 10 ml/min. Brains were post-fixed in 4% PFA for 12 h at 4°C and were subsequently transferred to a 30% sucrose solution. Coronal brain sections were produced using a sliding microtome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) for phenotyping and morphological analysis.

Histology and Counting Procedures

The following primary antibodies were used: chicken anti-GFP (1:2000, Aves), goat anti-HSP60 (1:500, Santa Cruz), mouse anti-OXPHOS/ETC mix (1:500, Abcam), mouse anti-NDUFB8 (1:500, Abcam), mouse anti-Cox1 (MTCO1; 1:500, Abcam), mouse anti-ATP5A (1:500, Abcam), mouse anti-GFAP (1:500, Sigma), rabbit anti-GFAP (1:500, DAKO), mouse anti-Nestin (1:500, Millipore), rat anti-BrdU (1:500, Bio-Rad, formerly Serotec); mouse anti-BrdU (1:500, Millipore), rabbit anti-Casp3 (1:100, Cell Signaling), mouse anti-NeuN (1:100, Merck Millipore), rabbit anti-Tfam (1:500, gift from Nils-Göran Larsson), mouse anti-CytC (1:500, Becton Dickson).

Primary antibodies were visualized with Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies (all 1:400, Invitrogen). As negative controls staining were performed using secondary antibody only.

Immunofluorescent stainings were performed on free-floating 40 and 50 μm sections. Slices were washed three times with PBS and incubated with primary antibodies in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and 10% normal donkey serum (NDS) for 72 h at 4°C. After incubation with the primary antibody, tissue was thoroughly washed with PBS at room temperature and subsequently incubated with the secondary antibody in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and 10% NDS overnight at 4°C or 2 h at room temperature. After washing thoroughly in PBS, nuclei were stained with DAPI and sections were mounted on coverslips with Aqua poly mount (Polysciences).

For BrdU staining, tissue was pre-treated in 2 M HCL for 30 min, washed shortly in PBS, incubated in Borate buffer (0.1 M, pH 8.5) two times for 15 min, followed by washing with PBS before adding the BrdU antibody.

For immunostainings against activated Caspase 3 (Casp3) and mitochondrial markers HSP60, NDUFB8, Cox1, ATP5A, and mitochondrial complexes I–V mix (OXPHOS/ETC mix), sections were subjected to antigen retrieval. Slices were incubated in Tris-EDTA/Tween20 for 5 min at 99°C and washed three times with MilliQ water followed by one washing step with PBS prior incubation with primary antibody. Biotinylated secondary antibodies (1:400; Vector Laboratories) were used in combination with Alexa-conjugated to Streptavidin (1:400; Invitrogen) to enhance the signal of Casp3, NDUFB8, Cox1, HSP60, ATP5A, and OXPHOS/ETC mix.

Confocal single plane images and Z-stacks were taken at the Zeiss LSM 780 with four lasers (405, 488, 559, and 633 nm) and 40 and 63x objective lens. Images were processed using Fiji ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop CS5.

Photochemically Initiated Thrombosis (PIT)

Photochemically initiated thrombosis was induced in 4 months-old Tfamctrl (n = 6) and Tfamcko mice (n = 7), the time point when the mitochondrial phenotype of GlastCre::ERT2-mediated Tfam deletion manifested (Beckervordersandforth et al., 2017). For that mice were deeply anesthetized by intraperitonial (i.p.) injection of Fentanyl (0.05 mg/kg; Janssen-Cilag AG, New Brunswick, NJ, United States), Midazolam (5 mg/kg; Dormicum, Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and Medetomidine (0.5 mg/kg; Domitor, Pfizer, Inc., New York City, NY, United States) dissolved in 0.9% NaCl, followed by i.p. injection with a saline solution of Rose Bengal (0.2 ml of 10 mg/ml in 0.9% NaCl). Illumination of the exposed skull with an optic fiber bundle connected to a cold light source (3200 Kelvin) led to a photochemical induction of Rose Bengal causing the formation of superoxide and singlet oxygen. This results in endothelial injury, platelet aggregation and activation, causing thrombosis of the cortical vessel in the region of the irradiated skull (Watson et al., 1985; Keiner et al., 2008, 2009).

Infarct Volumetry Analysis

Using a charge-coupled device camera, Simple PCI software and Scion Image we measured the infarct area of the photothrombotic lesion (mm2) on every 8Th cresyl violet stained section (containing approximately 6–7 slices). Further, the measured lesion areas of each animal were added and multiplied with the section interval and the section thickness (40 μm) to determine the lesion volume per animal and group.

BrdU Administration

For proliferation studies, animals were i.p. injected with a single daily dose of Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, 50 mg/kg body weight, Sigma-Aldrich) on days 2–6 post-PIT. The number of BrdU-incorporating astrocytes was counted 14 days post-PIT. BrdU was dissolved in 0.9% NaCl and sterile filtered.

Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, we first tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. If normally distributed, significance levels were assessed using unpaired Student’s t-test with unequal variances, for non-normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney test was used. Differences were considered statistically significant at ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. All data are presented as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). The number of samples analyzed for each experiment is indicated in the figure legends.

Results

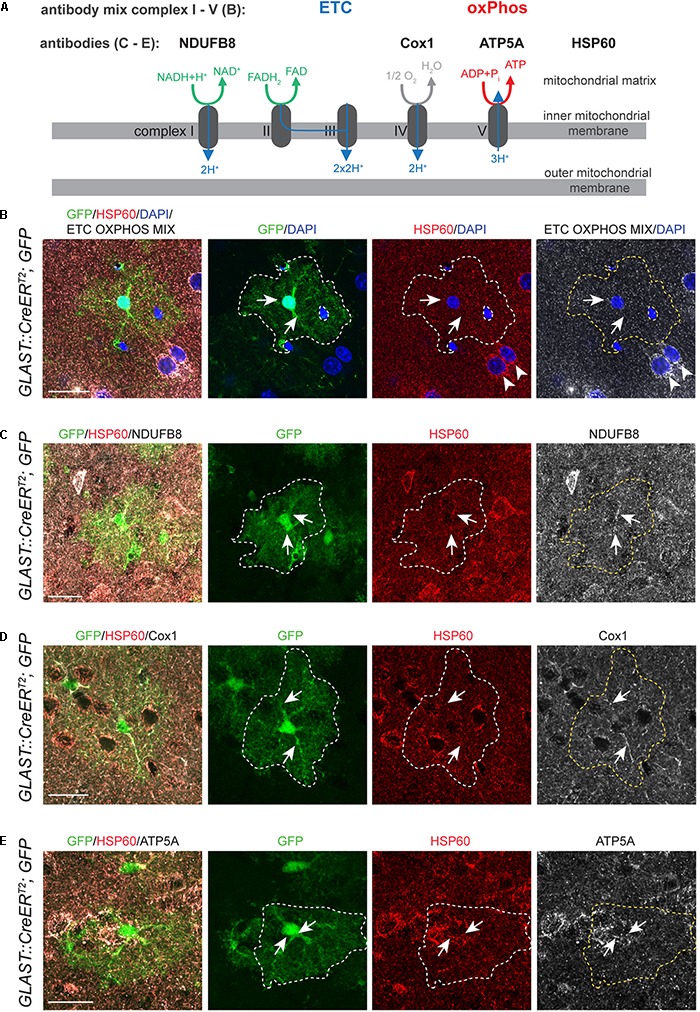

Astrocytes Expressed ETC and oxPhos Components in vivo

Data from mRNA expression analyses suggest that astrocytes express the necessary molecular machinery to perform oxidative metabolism (Lovatt et al., 2007; Cahoy et al., 2008). To further support this notion and to validate the expression of ETC and oxPhos components on protein level, we made use of a recently established fluorescent immunohistochemistry protocol for the labeling of mitochondrial matrix protein and components of the mitochondrial ETC and oxPhos complexes in vivo in brain sections (Beckervordersandforth et al., 2017). To visualize the astrocytic cell bodies, we crossed GLAST::CreERT2 mice (Mori et al., 2006) to cytoplasmic GFP reporter mice [CAG CAT GFP mice; (Nakamura et al., 2006)]. Recombination was induced by intraperitonial administration of Tamoxifen at postnatal days 14, 16, and 18, and resulted in mosaic labeling of cortical astrocytes. Mitochondria were identified using an antibody against mitochondrial chaperone HSP60 (Figure 1A–E), an intramitochondrially localized molecule (Bukau and Horwich, 1998). First evidence for the expression of mitochondrial ETC and oxPhos components in cortical astrocytes came from the analysis of ETC/OXPHOS antibody-mix (Figure 1B, arrows), containing five different antibodies against components of mitochondrial complexes I–V. GFP-labeled cortical astrocytes revealed expression of ETC/OXPHOS components in HSP60+ mitochondria (Figure 1B, arrows). Surrounding cortical neurons contained a large number of HSP60+ mitochondria expressing the ETC/OXPHOS mix (arrowheads; Figure 1B). To delineate individual mitochondrial complexes we next used antibodies against single components of complex I (NADH: ubiquinoneoxidoreductase subunit B8, NDUFB8; Figure 1C), complex IV (Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1, Cox1; Figure 1D) and complex V (ATP synthase subunit 5A, ATP5A; Figure 1E). All tested components were present in astrocytic mitochondria, indicating that cortical astrocytes express ETC and oxPhos proteins in vivo.

FIGURE 1.

Astrocytes express ETC and oxPhos components in vivo. (A) Schematic drawing illustrating localization and function of mitochondrial complexes of the electron transport chain (ETC) and oxidative phosphorylation (oxPhos); antibodies used in (B–E) to visualize expression of mitochondrial complex components are indicated. (B) DAPI was used to counterstain nuclei of glial and neuronal cells (arrowheads). (B–E) Glast::CreERT2;GFP mice labeled single astrocytes (green; outlined by white or yellow dotted line in all pictures except merge on the left); HSP60 labeled mitochondria (red); immunoreactivity for ETC OXPHOS MIX (B) and specific mitochondrial complex components NDUFB8 (C), Cox1 (D), ATP5A (E) shown in white. Immunostainings revealed that astrocytes in the cortex express all mitochondrial complex components tested (arrows in B–E). Pictures represent collapses of 2–3 confocal stacks. All scale bars = 20 μm.

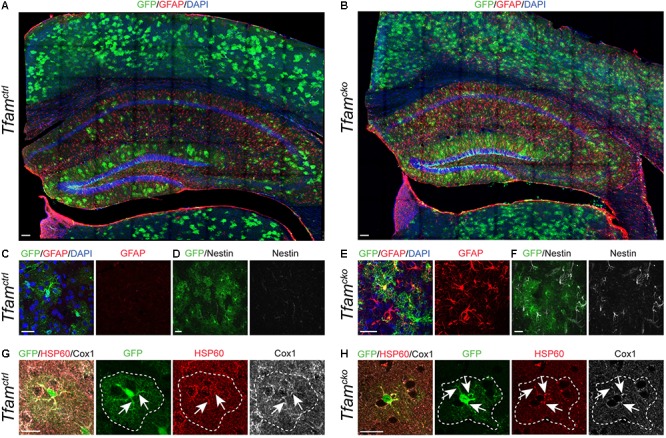

Conditional Deletion of Tfam in Cortical Astrocytes Induced Reactive Gliosis and Mitochondrial Swelling

Next, we aimed to assess if cortical astrocytes require a functional ETC and oxPhos machinery. For that reason, ETC and oxPhos activity was genetically disrupted by conditional deletion of Tfam, a transcription factor required for the transcription of mitochondrial DNA, which mostly encodes for components of ETC and oxPhos complexes. By crossing Tfamfl/fl mice (Larsson et al., 1998) with GLAST::CreERT2 and CAG CAT GFP, we generated conditional knockout mice that upon Tamoxifen-induced recombination lacked Tfam (Tfamcko), and as a consequence transcription of mtDNA encoded ETC and oxPhos components in astrocytes. GFP-reporter expression allowed for the detection of recombined astrocytes. GLAST::CreERT2; CAG CAT GFP mice harboring WT alleles for Tfam served as controls (Tfamctrl). Recombination was induced postnatally as described above. Because of the long half-life of Tfam transcripts conditional Tfam mutants consistently show protracted development of a phenotype after disruption of the Tfam locus (Wang et al., 1999; Sorensen et al., 2001; Ekstrand et al., 2007; Beckervordersandforth et al., 2017). Analysis was therefore carried out starting 3 months post-induction. First, we validated if Cre-mediated recombination led to a loss of Tfam. To assess recombination of the Tfam locus in vivo, we isolated GFP-expressing astrocytes from different brain areas of postnatally recombined animals by fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS), and performed PCR (Supplementary Figure 1A). Astrocytes isolated from Tfamctrl mice revealed a single band of 404 bp representing the wildtype (Supplementary Figure 1B, left). In astrocytes isolated from the cortex of Tfamcko animals we detected a strong Tfamcko band (330 bp) and a weak Tfamfloxed band (437 bp; Supplementary Figure 1B, right), indicating that the Tfam locus was successfully recombined in vivo. Due to an unreliable immunofluorescent signal of the available TFAM antibodies in vivo, we were not able to assess if recombination led to loss of Tfam protein. We therefore switched to an in vitro system, and isolated cortical astrocytes from postnatal day 5 mice harboring the GFP-reporter as well as conditional Tfamfloxed alleles (CAG CAT GFP; Tfamfl/fl). Recombination was induced by transduction with the His-TAT-NLS-Cre (HTNCre) protein (Supplementary Figure 1C; Peitz et al., 2002). Six days post-transduction, the astrocytes were either fixed for immunohistochemistry (Supplementary Figure 1D), or used for PCR to validate recombination of the conditional Tfam locus (Supplementary Figure 1E). Immunohistochemistry against the Tfam protein revealed that Tfam was almost completely absent in GFP+ astrocytes, but present in non-recombined GFP- astrocytes (Supplementary Figure 1D). Importantly, the mitochondrial marker Cytochrome C (CytC) confirmed that mitochondria were present in both non-recombined GFP- and recombined GFP+ astrocytes (Supplementary Figure 1D). PCR of cortical astrocyte cultures transduced with increasing amount of HTNCre (1, 2, and 4 μl) revealed an increase of the Tfamcko band (330 bp), and a reduction of the Tfamfloxed band (437 bp; Supplementary Figure 1E). These results indicated that the conditional Tfam locus could be efficiently recombined in cortical astrocytes by Cre recombinase. The results also confirmed that Tfam protein is lost upon Cre-mediated recombination, and further validated that recombination events correlated with the expression of the GFP reporter.

We first investigated the effects of Tfam deletion in cortical astrocytes in vivo. In the cortex, GLAST::CreERT2 driven recombination efficiency was more than 50% as reported before (Supplie et al., 2017), and was comparable between genotypes 4 months and 1 year post-recombination (Figure 2A,B and Supplementary Figures 2A,B), indicating that deletion of Tfam in astrocytes did not affect their survival. However, Tfam dysfunction induced upregulation of intermediate filament components glial acidic fibrillary protein (GFAP, Figure 2A–C,E) and Nestin (Figure 2D,F). Neither GFAP nor Nestin are expressed in astrocytes of the adult cortex under physiological conditions. Only upon challenge, such as injury or disease astrocytes become reactive, and upregulate GFAP and Nestin as an important hallmark of reactive gliosis (Robel et al., 2011). Thus, Tfam deletion induced a reactive gliosis in cortical astrocytes (Figure 2B,E,F) in comparison to Tfamctrl mice (Figure 2A,C,D).

FIGURE 2.

Tfam deletion in astrocytes induces reactive gliosis and aberrant mitochondrial morphology in the cortex. Phenotypic comparison between Tfamctrl (left) and Tfamcko mice (right). (A–F) Tfam deletion in astrocytes induced reactive gliosis in the cortex as shown by intermediate filament markers GFAP (A–C,E) and Nestin (D,F). (G,H) Immunostaining for Tfam-independent mitochondrial marker HSP60 (red) and Tfam-dependent mitochondrial protein Cox1 (white); GFP (green) served to identify recombined cells (outlined by white dotted lines). Tfam depletion led to mitochondrial clumping in astrocytes, but did not result in loss of Cox1 expression (arrows). All scale bars = 20 μm, except (A,B) scale bars = 100 μm.

Next, we wanted to find out how Tfam deletion affected mitochondria of astrocytes. Therefore, analysis of mitochondrial morphology and expression of HSP60 together with ETC and oxPhos components in recombined cells in Tfamctrl and Tfamcko animals was carried out (Figure 2G,H). While mitochondrial shape was undistinguishable between recombined and non-recombined cells in Tfamctrl mice (Figure 2G), 55% of recombined cells in Tfamcko mice contained mitochondria with an aberrant clumpy morphology and increased HSP60 expression levels (Figure 2H). These morphological alterations (often referred to as mitochondrial “swellings”) have been reported across different cell types following Tfam-depletion, including neurons (Beckervordersandforth et al., 2017), epidermal stem cells (Baris et al., 2011), cardiac stem cells (Chung et al., 2007), and brown adipose tissue (Vernochet et al., 2012), and are indicative of mitochondrial dysfunction. Surprisingly, and in contrast to Tfam deletion in newborn neurons (Beckervordersandforth et al., 2017), mitochondria of recombined astrocytes still contained mtDNA-encoded Cox1 protein (Figure 2H, arrows), whose expression requires Tfam.

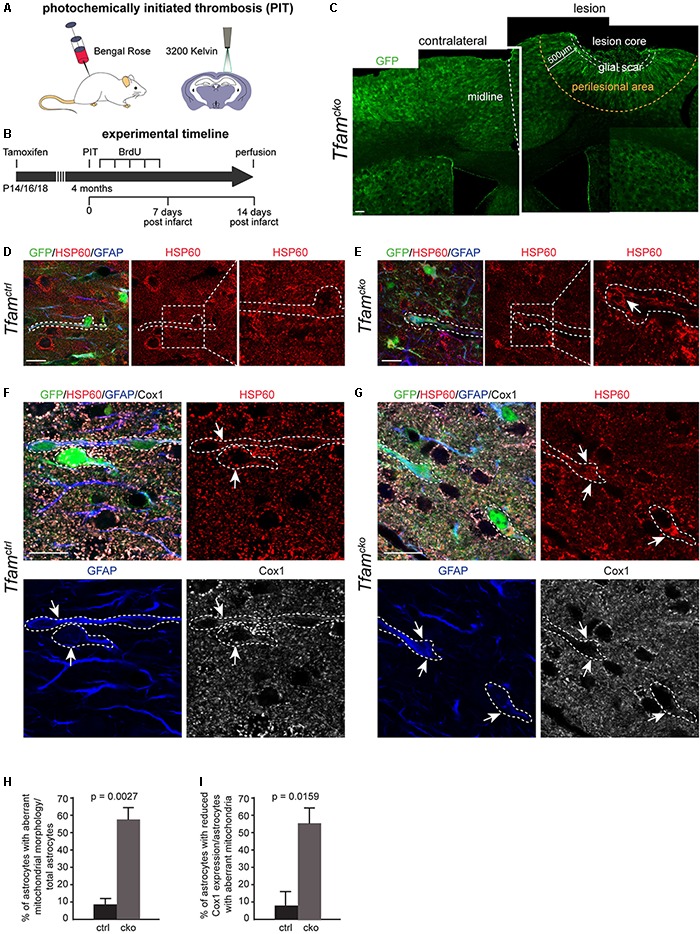

Photochemically Initiated Thrombosis Worsened Mitochondrial Morphology in Tfam-Depleted Cortical Astrocytes of the Perilesional Area

Changes in astrocyte function during injury response can markedly impair healing and regeneration of insulted CNS areas (Burda and Sofroniew, 2014). Next, we investigated if mitochondrial dysfunction impaired astrocytes function in the context of CNS injury. Ischemic stroke was induced in the cortex of 4 months old Tfamctrl and Tfamcko mice by PIT (Figure 3A). The effects on reactive astrocytes and surrounding tissue were investigated 2 weeks later (Figure 3B). PIT created a lesion that affected all cortical layers but left the subcortical white matter intact (Figure 3C). The lesion consisted of three distinct regions as described before: core, glial scar, and perilesional area (Wanner et al., 2013; Burda and Sofroniew, 2014). The lesion core mainly contains dead cells and tissue that is irretrievably damaged. The glial scar consists of astrocytes and surrounds the core tissue as a structural border between dead non-neuronal tissue and viable cells. The perilesional area is adjacent to the scar and is populated by astrocytes, neurons, oligodendrocytes, and microglia (Wanner et al., 2013). It is the only part of the lesion responsive to interventions and rehabilitation therapies. Furthermore, astrocytes have been shown to play a role in plasticity of the perilesional area in response to PIT (Keiner et al., 2008). For these reasons, our analysis was focused on the perilesional area, which we defined as the area within 500 μm from the boarders of the lesion core (Figure 3C).

FIGURE 3.

Photochemically initiated thrombosis (PIT) worsened mitochondrial phenotypes of Tfam-depleted reactive astrocytes and reduced Cox1 expression. (A,B) Experimental scheme used in (C–I). (C) Confocal image of a coronal cortical section of Tfamcko mice upon PIT; midline indicated by a white dotted line; GFP indicates recombined cells. Contralateral hemisphere shown on the left; PIT lesioned hemisphere (right) with glial scar (white dotted area) and perilesional area (yellow dotted area), which was defined as the area 500 μm away from the lesion. (D–G) Comparison of mitochondrial phenotype between Tfamctrl and Tfamcko mice upon PIT (dotted lines represent process of recombined astrocyte); (D,E) dotted boxes indicate area of higher magnification on the right. (D,F,H,I) Few mitochondrial aberrations were detected in Tfamctrl mice (D, arrows in F), while Tfam depletion led to mitochondrial elongation and hyperfusion, and diminished Cox1 expression in reactive astrocytes (arrows; E,G). (H) Quantification of total astrocytes harboring aberrant mitochondria; (I) reduced Cox1 expression in perilesional astrocytes with aberrant mitochondria. (D–I) nctrl = 5 animals, ncko = 5 animals. Data represent as mean ± SEM; t-test (H) and Mann-Whitney test (I) was performed to determine significance; scale bars = 100 μm (C) and = 10 μm (D–G).

Traumatic brain injuries have been shown to induce changes in mitochondrial marker expression and ultrastructure in mice as well as in humans (Balan et al., 2013; Motori et al., 2013). Therefore, we first investigated if PIT-induced injury affected mitochondria of astrocytes by assessing their morphology (Figure 3D–H). In Tfamctrl mice, a minor fraction of astrocytes in the perilesional area showed aberrations in mitochondrial morphology (8%; Figure 3H). The percentage of astrocytes harboring morphologically aberrant mitochondria did not change between Tfamcko animals in physiological and PIT-induced injury conditions (Figure 3H). While we mostly observed mitochondrial clumping in Tfamcko mice under non-injury conditions, in the perilesional area, Tfam-depleted reactive astrocytes came mainly in two flavors: a mitochondrial clumping phenotype as well as elongated mitochondria, which in some cells appeared as an interconnected meshwork of hyperfused organelles (Figure 3E,G). Interestingly, 56% of perilesional Tfam depleted astrocytes with aberrant mitochondria showed a reduction in Cox1-protein expression (Figure 3G,I). These results suggest that focal ischemia significantly worsened the mitochondrial phenotype of Tfam-depleted astrocytes as indicated by mitochondrial hyperfusion and a reduction in Cox1 expression.

Tfam Dysfunction Impaired the Generation of New Reactive Astrocytes and Increased Death of Neurons in the Perilesional Area of PIT

Previous work has shown that the infarct size upon PIT is highly reproducible, which makes this model very suitable to investigate clinical outcome and repair mechanisms (Diederich et al., 2014; Frauenknecht et al., 2016). We therefore determined if Tfam deletion in reactive astrocytes changed lesion volumetry. Fourteen days after PIT, the infarct volume was comparable between Tfamctrl and Tfamcko mice (Figure 4A), indicating that deletion of Tfam did not alter infarct size. Next, we wanted to know if Tfam-depletion affected survival of astrocytes upon PIT. Counting the number of recombined astrocytes in the perilesional area 2 weeks post-infarct revealed no changes between Tfamctrl and Tfamcko mice (Supplementary Figure 2C), suggesting that also under severe injury conditions astrocytes are not dependent on mitochondrial respiration for survival.

FIGURE 4.

Mitochondrial dysfunction led to reduced generation of reactive astrocytes and increased neuronal death in the perilesional area. (A) Lesion volumetry revealed no difference between Tfamctrl and Tfamcko mice. (B–D) Confocal picture of Tfamctrl (B) and Tfamcko (C) animal stained against BrdU (red), GFP (green), and GFAP (white). (D) Percentage of GFAP+/GFP+ cells amongst all BrdU+ cells was sigificantly reduced in Tfamcko mice in comparison to Tfamctrl. (E–G) Confocal images and quantification of Casp3 immunostaining (red) in Tfamctrl and Tfamcko mice; GFP+ shows recombined cells (green); NeuN labels neurons (white); DAPI indicates cell nuclei. Tfam deletion in astrocytes significant increased neuronal cell death in the perilesional area (G). (A–D) nctrl = 6 animals, ncko = 8 animals; (E–G) nctrl = 4 animals, ncko = 4 animals. Data represented as mean ± SEM; t-test was performed to determine significance; all scale bars = 20 μm.

A key parameter in injury-induced reactive gliosis is proliferation of reactive astrocytes. To investigate the proliferative response of astrocytes in Tfamctrl and Tfamcko animals, we determined the number of newly generated astrocytes in the perilesional area. Animals received five consecutive injections of Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) on days 2–6 post-PIT, and the number of BrdU-incorporating astrocytes was counted 14 days post-PIT (Figure 3B). Here, we observed a significant decrease in BrdU incorporation of recombined reactive astrocytes in the Tfamcko mice compared to Tfamctrl mice (BrdU+/GFAP+/GFP+/total BrdU+ cells; Figure 4B–D).

These data suggest that the generation of new astrocytes in the perilesional area is hampered in astrocytes with mitochondrial dysfunction.

Astrocytes have neuroprotective functions potentially through secretion of neurotrophic factors, the supply of metabolites and transfer of antioxidant molecules (Belanger and Magistretti, 2009). We next examined whether Tfam-deletion induced mitochondrial dysfunction compromised the neuroprotective role of astrocytes. To this end, we combined immunostaining against the apoptosis marker activated Caspase 3 (Casp3) with the neuronal marker NeuN, and quantified the number of Casp3+/NeuN+ neurons in the perilesional area (Figure 4E–G). In the contralateral hemisphere, we did not detect differences in the number of Casp3+ cells between Tfamctrl and Tfamcko animals (Supplementary Figures 3A–F). Intriguingly, the number of Casp3+/NeuN+ neurons was more than doubled in Tfamcko compared to Tfamctrl animals (Figure 4D–F). These results indicate that mitochondrial dysfunction in astrocytes led to increased neuronal cell death upon PIT, suggesting that mitochondrial dysfunction compromises the neuroprotective function of astrocytes.

Discussion

The requirement and function of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism in astrocyte physiology are a matter of ongoing debate. Only recently, convincing in vivo evidence has been provided that a particular astrocyte subtype, i.e., Bergmann Glia of the cerebellum does not require ETC/oxPhos for long-term-survival (Supplie et al., 2017). Here, we investigated the in vivo requirement of ETC/oxPhos in cortical astrocytes in physiological and injury context. We demonstrate that cortical astrocytes express components of the ETC and oxPhos complexes. Genetically induced dysfunction of mitochondrial oxidative metabolism did not affect astrocyte long-term survival, but caused reactive gliosis in the forebrain. Upon challenge by PIT induced ischemic stroke, mitochondrial dysfunction compromised the response of reactive astrocytes as it was associated with a decrease in the generation of new astrocytes and increased neuronal cell death in the perilesional area. These results indicate that mitochondrial respiration is not essential for astrocyte survival but is required for reactive astrocyte function.

Our data extend the recent experimental evidence that ETC and oxPhos functions are not required for long-term survival from Bergmann glia to forebrain astrocytes. In the previous study, ETC/OxPhos deficiency caused by Cox10 ablation neither induced alterations in cerebellar cytoarchitecture nor caused reactive gliosis. In contrast, deletion of Tfam resulted in reactive gliosis in the cortex, as indicated by strongly upregulated intermediate filaments GFAP and Nestin. Why does deletion of Tfam induce such a strong glial phenotype, while no signs of glial pathology and neurodegeneration could be observed upon Cox10 deficiency? The discrepancy between the two studies might be explained by the fact that Cox10 dysfunction affects exclusively complex IV. Tfam deletion efficiently reduces the activity of complexes I, III, IV and V (Larsson et al., 1998; Baris et al., 2011; Vernochet et al., 2012), resulting in a more severe dysfunction of ETC and oxPhos as suggested by the aberrant mitochondrial morphology. The observed mitochondrial “swellings” in astrocytes are indicative of mitochondrial dysfunction and have been observed in various cell types upon Tfam deletion, including skeletal muscles, epidermal and cardial stem cells, adipose tissue, hepatocytes, Schwann cells, and neurons (Sorensen et al., 2001; Diaz et al., 2005; Baris et al., 2011; Funfschilling et al., 2012; Vernochet et al., 2012; Beckervordersandforth et al., 2017). Furthermore, in the context of neurodegenerative diseases, especially ETC complex I appears to play a crucial role in development of pathological symptoms (Mizuno et al., 1989; Schapira et al., 1989; Papa et al., 2002; Keeney et al., 2006; Cassina et al., 2008), supporting the idea that impairment of multiple complexes, including complex I, may have more severe consequences on astrocyte function than the deletion of complex IV alone.

Reactive gliosis is a finely graded process ranging from mild astrogliosis with potential for resolution to an extreme form involving scar formation. Severe tissue damage, including stroke, lead to proliferation of reactive astrocytes and to formation of a compact glial scar surrounding the lesion and separating the damaged non-functional lesion core from adjacent and potentially functional neural tissue (Faulkner et al., 2004; Gadea et al., 2008; Sirko et al., 2013; Wanner et al., 2013). Transgenic disruption of the astrocyte scar by ablation of proliferating astrocytes lead to increased death of local neurons, and impaired recovery of function after focal insult (Faulkner et al., 2004; Herrmann et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008; Wanner et al., 2013). Our work uncovered a potential link between mitochondrial function and the generation of new astrocytes by showing that ETC and oxPhos dysfunction significantly reduced BrdU incorporation of astrocytes in the perilesional area in a PIT-induced stroke model suggesting a proliferation defect of Tfam-deficient reactive astrocytes. Tfam-deficiency may have also lead to impaired survival of astrocytes generated in response to injury. Immunohistochemistry against Casp3 showed that at 14 days post PIT-induced stroke astrocytic cell death is a very rare event in both Tfamctrl and Tfamcko. Further experiments are required to establish whether Tfam-deficiency may affect astrocytes survival in the PIT-induced stroke context at other time points.

How can mitochondrial respiration influence proliferation? One possible explanation may be that ETC is especially important in dividing cells because it accepts reducing equivalents generated during pyrimidine nucleotide synthesis and is therefore necessary for RNA- and DNA- production. Astrocytes in the cortex are post-mitotic under healthy conditions and not affected by the lack of Tfam. Upon injury, they are forced to divide and to generate new DNA building blocks. This process may be hampered by the accumulation of reducing equivalents, which are normally recycled by functional ETC complexes.

Under injury conditions, the mitochondrial phenotype of perilesional astrocytes deteriorated from swelled/clumped mitochondria to a hyperfused mitochondrial network. Mitochondrial fusion is essential for preserving quality control and intermixing of mitochondrial contents to facilitate changes in respiratory capacity, and adapt to cellular metabolic demands. Interestingly, it has been shown that mitofusin 2 (Mfn2), the key protein in mitochondrial fusion (Ehses et al., 2009; Belenguer and Pellegrini, 2013), negatively regulates cell proliferation. In an in vitro model of reactive gliosis, Mfn2 overexpression inhibits proliferation of reactive astrocytes by arresting the transition of cell cycle from G1 to S phase (Liu et al., 2014). Based on these results, it is tempting to speculate that proliferation may be blocked by cell cycle arrest in Tfam-depleted reactive astrocytes. It will be very interesting in the future to investigate the link between proliferation capacity and mitochondria dynamics.

Tfam-deletion in astrocytes of the perilesional area led to increased cell death of surrounding neurons. Astrocytes have the potential to enhance neuronal survival and regeneration through the release of, e.g., metabolic factors, detoxifying molecules, and neurotrophic factors (Sofroniew and Vinters, 2010; Allaman et al., 2011; Barreto et al., 2011; Cabezas et al., 2012). It is also becoming increasingly clear that protecting mitochondria in astrocytes is a promising strategy against loss of neurons in brain injury (Cabezas et al., 2012). An interesting candidate to link mitochondrial function in astrocytes to their role in neuroprotection is the translocator protein 18 kDA (TSPO). TSPO is located at the outer mitochondrial membrane and transports cholesterol into the inner compartments of mitochondria, which is the rate-limiting step in neurosteroid synthesis (reviewed in Milenkovic et al., 2015; Papadopoulos et al., 2018). Neurosteroids are important factors for protecting the brain from damage induced by, e.g., ischemic stroke or neurodegeneration (Tajalli-Nezhad et al., 2018). Interestingly, TSPO expression as well as binding of its ligands are upregulated in stroke and neurodegenerative disorders, implicating a regulatory role of mitochondrial TSPO in neurosteroid-mediated neuroprotection in pathological states. For future research, it will be very interesting to investigate if TSPO function and neurosteroid-dependent neuroprotection are affected by mitochondrial dysfunction. With the aim to identify new strategies to regenerate brain tissue after injury, a detailed understanding of the critical mitochondrial metabolic circuits in astrocytes and their function in neuroprotection is required.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data is contained within the manuscript.

Author Contributions

CF, BE, RJ, DL, and RB: conceptualization. CF, SK, BE, IS, and RB: investigation. CF, SK, BE, and RB: formal analysis. RB: resources and funding acquisition and writing-original draft. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer FC and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation at the time of review.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Götz (LMU Munich) and N. Larsson (Max Planck Institute for Biology of Ageing, Cologne) for providing the GLAST::CreERT2 and the TfamloxP/loxP mice, respectively. We also thank Julia Schneider for carefully reading the manuscript.

The present work was performed in (partial) fulfillment of the requirements for obtaining the degree “Dr. med.”

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (BE 5136/1-1, 1-2, and 2-1 to RB, KE1914/2-1 to SK,LI 858/6-3 and 9-1 to DL, INST 410/45-1 FUGG). CF and RB are fellows of the research training group 2162 “Neurodevelopment and Vulnerability of the Central Nervous System” of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG GRK2162/1). SK was supported by the Interdisciplinary Centre for Clinical Research (IZKF) Jena.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnmol.2019.00040/full#supplementary-material

References

- Allaman I., Belanger M., Magistretti P. J. (2011). Astrocyte-neuron metabolic relationships: for better and for worse. Trends Neurosci. 34 76–87. 10.1016/j.tins.2010.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D., Buchan A. M., Charpak S., Lauritzen M., Macvicar B. A., Newman E. A. (2010). Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature 468 232–243. 10.1038/nature09613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balan I. S., Saladino A. J., Aarabi B., Castellani R. J., Wade C., Stein D. M., et al. (2013). Cellular alterations in human traumatic brain injury: changes in mitochondrial morphology reflect regional levels of injury severity. J. Neurotrauma 30 367–381. 10.1089/neu.2012.2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baris O. R., Klose A., Kloepper J. E., Weiland D., Neuhaus J. F., Schauen M., et al. (2011). The mitochondrial electron transport chain is dispensable for proliferation and differentiation of epidermal progenitor cells. Stem Cells 29 1459–1468. 10.1002/stem.695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto G., White R. E., Ouyang Y., Xu L., Giffard R. G. (2011). Astrocytes: targets for neuroprotection in stroke. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 11 164–173. 10.2174/187152411796011303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto G. E., Gonzalez J., Capani F., Morales L. (2012). Neuroprotective agents in brain injury: a partial failure? Int. J. Neurosci. 122 223–226. 10.3109/00207454.2011.648292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckervordersandforth R., Ebert B., Schaffner I., Moss J., Fiebig C., Shin J., et al. (2017). Role of mitochondrial metabolism in the control of early lineage progression and aging phenotypes in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Neuron 93 560.e6–573.e6. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanger M., Allaman I., Magistretti P. J. (2011). Brain energy metabolism: focus on astrocyte-neuron metabolic cooperation. Cell Metab. 14 724–738. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanger M., Magistretti P. J. (2009). The role of astroglia in neuroprotection. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 11 281–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenguer P., Pellegrini L. (2013). The dynamin GTPase OPA1: more than mitochondria? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833 176–183. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau B., Horwich A. L. (1998). The Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone machines. Cell 92 351–366. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80928-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burda J. E., Sofroniew M. V. (2014). Reactive gliosis and the multicellular response to CNS damage and disease. Neuron 81 229–248. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas R., El-Bacha R. S., Gonzalez J., Barreto G. E. (2012). Mitochondrial functions in astrocytes: neuroprotective implications from oxidative damage by rotenone. Neurosci. Res. 74 80–90. 10.1016/j.neures.2012.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoy J. D., Emery B., Kaushal A., Foo L. C., Zamanian J. L., Christopherson K. S., et al. (2008). A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. J. Neurosci. 28 264–278. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassina P., Cassina A., Pehar M., Castellanos R., Gandelman M., de Leon A., et al. (2008). Mitochondrial dysfunction in SOD1G93A-bearing astrocytes promotes motor neuron degeneration: prevention by mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants. J. Neurosci. 28 4115–4122. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5308-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S., Dzeja P. P., Faustino R. S., Perez-Terzic C., Behfar A., Terzic A. (2007). Mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is required for the cardiac differentiation of stem cells. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 4(Suppl. 1), S60–S67. 10.1038/ncpcardio0766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz F., Thomas C. K., Garcia S., Hernandez D., Moraes C. T. (2005). Mice lacking COX10 in skeletal muscle recapitulate the phenotype of progressive mitochondrial myopathies associated with cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14 2737–2748. 10.1093/hmg/ddi307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederich K., Schmidt A., Strecker J. K., Schabitz W. R., Schilling M., Minnerup J. (2014). Cortical photothrombotic infarcts impair the recall of previously acquired memories but spare the formation of new ones. Stroke 45 614–618. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan L. L., Kim-Han J. S. (2004). Astrocyte mitochondria in in vitro models of ischemia. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 36 317–321. 10.1023/B:JOBB.0000041761.61554.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehses S., Raschke I., Mancuso G., Bernacchia A., Geimer S., Tondera D., et al. (2009). Regulation of OPA1 processing and mitochondrial fusion by m-AAA protease isoenzymes and OMA1. J. Cell Biol. 187 1023–1036. 10.1083/jcb.200906084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand M. I., Terzioglu M., Galter D., Zhu S., Hofstetter C., Lindqvist E., et al. (2007). Progressive parkinsonism in mice with respiratory-chain-deficient dopamine neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 1325–1330. 10.1073/pnas.0605208103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner J. R., Herrmann J. E., Woo M. J., Tansey K. E., Doan N. B., Sofroniew M. V. (2004). Reactive astrocytes protect tissue and preserve function after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 24 2143–2155. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3547-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frauenknecht K., Diederich K., Leukel P., Bauer H., Schabitz W. R., Sommer C. J., et al. (2016). Functional improvement after photothrombotic stroke in rats is associated with different patterns of dendritic plasticity after G-CSF treatment and G-CSF treatment combined with concomitant or sequential constraint-induced movement therapy. PLoS One 11:e0146679. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funfschilling U., Supplie L. M., Mahad D., Boretius S., Saab A. S., Edgar J., et al. (2012). Glycolytic oligodendrocytes maintain myelin and long-term axonal integrity. Nature 485 517–521. 10.1038/nature11007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadea A., Schinelli S., Gallo V. (2008). Endothelin-1 regulates astrocyte proliferation and reactive gliosis via a JNK/c-Jun signaling pathway. J. Neurosci. 28 2394–2408. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5652-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenamyre J. T., Betarbet R., Sherer T. B. (2003). The rotenone model of Parkinson’s disease: genes, environment and mitochondria. Parkinsonism. Relat. Disord. 9(Suppl. 2), S59–S64. 10.1016/S1353-8020(03)00023-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby M. E., Coppola G., Ao Y., Geschwind D. H., Khakh B. S., Sofroniew M. V. (2012). Inflammatory mediators alter the astrocyte transcriptome and calcium signaling elicited by multiple G-protein-coupled receptors. J. Neurosci. 32 14489–14510. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1256-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich C., Blum R., Gascon S., Masserdotti G., Tripathi P., Sanchez R., et al. (2010). Directing astroglia from the cerebral cortex into subtype specific functional neurons. PLoS Biol. 8:e1000373. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann J. E., Imura T., Song B., Qi J., Ao Y., Nguyen T. K., et al. (2008). STAT3 is a critical regulator of astrogliosis and scar formation after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 28 7231–7243. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1709-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz L., Peng L., Dienel G. A. (2007). Energy metabolism in astrocytes: high rate of oxidative metabolism and spatiotemporal dependence on glycolysis/glycogenolysis. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 27 219–249. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C., Nedergaard M. (2007). Glial regulation of the cerebral microvasculature. Nat. Neurosci. 10 1369–1376. 10.1038/nn2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney P. M., Xie J., Capaldi R. A., Bennett J. P., Jr. (2006). Parkinson’s disease brain mitochondrial complex I has oxidatively damaged subunits and is functionally impaired and misassembled. J. Neurosci. 26 5256–5264. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0984-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiner S., Witte O. W., Redecker C. (2009). Immunocytochemical detection of newly generated neurons in the perilesional area of cortical infarcts after intraventricular application of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 68 83–93. 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31819308e9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiner S., Wurm F., Kunze A., Witte O. W., Redecker C. (2008). Rehabilitative therapies differentially alter proliferation and survival of glial cell populations in the perilesional zone of cortical infarcts. Glia 56 516–527. 10.1002/glia.20632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson N. G., Wang J., Wilhelmsson H., Oldfors A., Rustin P., Lewandoski M., et al. (1998). Mitochondrial transcription factor A is necessary for mtDNA maintenance and embryogenesis in mice. Nat. Genet. 18 231–236. 10.1038/ng0398-231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Lundkvist A., Andersson D., Wilhelmsson U., Nagai N., Pardo A. C., et al. (2008). Protective role of reactive astrocytes in brain ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 28 468–481. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Xue C. C., Shi Y. L., Bai X. J., Li Z. F., Yi C. L. (2014). Overexpression of mitofusin 2 inhibits reactive astrogliosis proliferation in vitro. Neurosci. Lett. 579 24–29. 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovatt D., Sonnewald U., Waagepetersen H. S., Schousboe A., He W., Lin J. H., et al. (2007). The transcriptome and metabolic gene signature of protoplasmic astrocytes in the adult murine cortex. J. Neurosci. 27 12255–12266. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3404-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic V. M., Rupprecht R., Wetzel C. H. (2015). The translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO) and its role in mitochondrial biology and psychiatric disorders. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 15 366–372. 10.2174/1389557515666150324122642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno Y., Ohta S., Tanaka M., Takamiya S., Suzuki K., Sato T., et al. (1989). Deficiencies in complex I subunits of the respiratory chain in Parkinson’s disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 163 1450–1455. 10.1016/0006-291X(89)91141-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T., Tanaka K., Buffo A., Wurst W., Kuhn R., Gotz M. (2006). Inducible gene deletion in astroglia and radial glia–a valuable tool for functional and lineage analysis. Glia 54 21–34. 10.1002/glia.20350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motori E., Puyal J., Toni N., Ghanem A., Angeloni C., Malaguti M., et al. (2013). Inflammation-induced alteration of astrocyte mitochondrial dynamics requires autophagy for mitochondrial network maintenance. Cell Metab. 18 844–859. 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T., Colbert M. C., Robbins J. (2006). Neural crest cells retain multipotential characteristics in the developing valves and label the cardiac conduction system. Circ. Res. 98 1547–1554. 10.1161/01.RES.0000227505.19472.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard M., Ransom B., Goldman S. A. (2003). New roles for astrocytes: redefining the functional architecture of the brain. Trends Neurosci. 26 523–530. 10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberheim N. A., Takano T., Han X., He W., Lin J. H., Wang F., et al. (2009). Uniquely hominid features of adult human astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 29 3276–3287. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4707-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa S., Scacco S., Sardanelli A. M., Petruzzella V., Vergari R., Signorile A., et al. (2002). Complex I and the cAMP cascade in human physiopathology. Biosci. Rep. 22 3–16. 10.1023/A:1016004921277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos V., Fan J., Zirkin B. (2018). Translocator protein (18 kDa): an update on its function in steroidogenesis. J. Neuroendocrinol. 30:e12500. 10.1111/jne.12500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peitz M., Pfannkuche K., Rajewsky K., Edenhofer F. (2002). Ability of the hydrophobic FGF and basic TAT peptides to promote cellular uptake of recombinant Cre recombinase: a tool for efficient genetic engineering of mammalian genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 4489–4494. 10.1073/pnas.032068699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robel S., Berninger B., Gotz M. (2011). The stem cell potential of glia: lessons from reactive gliosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 88–104. 10.1038/nrn2978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapira A. H., Cooper J. M., Dexter D., Jenner P., Clark J. B., Marsden C. D. (1989). Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 1:1269 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)92366-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirko S., Behrendt G., Johansson P. A., Tripathi P., Costa M., Bek S., et al. (2013). Reactive glia in the injured brain acquire stem cell properties in response to sonic hedgehog [corrected]. Cell Stem Cell 12 426–439. 10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofroniew M. V., Vinters H. V. (2010). Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 119 7–35. 10.1007/s00401-009-0619-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen L., Ekstrand M., Silva J. P., Lindqvist E., Xu B., Rustin P., et al. (2001). Late-onset corticohippocampal neurodepletion attributable to catastrophic failure of oxidative phosphorylation in MILON mice. J. Neurosci. 21 8082–8090. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08082.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supplie L. M., Duking T., Campbell G., Diaz F., Moraes C. T., Gotz M., et al. (2017). Respiration-deficient astrocytes survive as glycolytic cells in vivo. J. Neurosci. 37 4231–4242. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0756-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajalli-Nezhad S., Karimian M., Beyer C., Atlasi M. A., Azami Tameh A. (2018). The regulatory role of Toll-like receptors after ischemic stroke: neurosteroids as TLR modulators with the focus on TLR2/4. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 76 523–537. 10.1007/s00018-018-2953-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernochet C., Mourier A., Bezy O., Macotela Y., Boucher J., Rardin M. J., et al. (2012). Adipose-specific deletion of TFAM increases mitochondrial oxidation and protects mice against obesity and insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 16 765–776. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volterra A., Meldolesi J. (2005). Astrocytes, from brain glue to communication elements: the revolution continues. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6 626–640. 10.1038/nrn1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wilhelmsson H., Graff C., Li H., Oldfors A., Rustin P., et al. (1999). Dilated cardiomyopathy and atrioventricular conduction blocks induced by heart-specific inactivation of mitochondrial DNA gene expression. Nat. Genet. 21 133–137. 10.1038/5089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner I. B., Anderson M. A., Song B., Levine J., Fernandez A., Gray-Thompson Z., et al. (2013). Glial scar borders are formed by newly proliferated, elongated astrocytes that interact to corral inflammatory and fibrotic cells via STAT3-dependent mechanisms after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 33 12870–12886. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2121-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson B. D., Dietrich W. D., Busto R., Wachtel M. S., Ginsberg M. D. (1985). Induction of reproducible brain infarction by photochemically initiated thrombosis. Ann. Neurol. 17 497–504. 10.1002/ana.410170513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamanian J. L., Xu L., Foo L. C., Nouri N., Zhou L., Giffard R. G., et al. (2012). Genomic analysis of reactive astrogliosis. J. Neurosci. 32 6391–6410. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6221-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z., Nelson A. R., Betsholtz C., Zlokovic B. V. (2015). Establishment and dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier. Cell 163 1064–1078. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data is contained within the manuscript.