Abstract

The biosynthetic and endocytic pathways of secretory cells are characterized by progressive luminal acidification, a process which is crucial for post-translational modifications and membrane trafficking. This progressive fall in luminal pH is mainly achieved by the Vacuolar-type-H+ ATPase (VATPase). V-ATPases are large, evolutionarily ancient rotary proton pumps that consist of a peripheral V1 complex, which hydrolyzes ATP, and an integral membrane V0 complex, which transports protons from the cytosol into the lumen. Upon sensing the desired luminal pH, V-ATPase activity is regulated by reversible dissociation of the complex into its V1 and V0 components. Molecular details of how intraluminal pH is sensed and transmitted to the cytosol are not fully understood. Peptidylglycine α-amidating monooxygenase (PAM; EC 1.14.17.3), a secretory pathway membrane enzyme which shares similar topology with two V-ATPase accessory proteins (Ac45 and prorenin receptor), has a pH-sensitive luminal linker region. Immunofluorescence and sucrose gradient analysis of peptidergic cells (AtT-20) identified distinct subcellular compartments exhibiting spatial co-occurrence of PAM and V-ATPase. In vitro binding assays demonstrated direct binding of the cytosolic domain of PAM to V1H. Blue native PAGE identified heterogeneous high molecular weight complexes of PAM and V-ATPase. A PAM-1 mutant (PAM-1/H3A) with altered pH sensitivity had diminished ability to form high molecular weight complexes. In addition, V-ATPase assembly status was altered in PAM-1/H3A expressing cells. Our analysis of the secretory and endocytic pathways of peptidergic cells supports the hypothesis that PAM serves as a luminal pH-sensor, regulating V-ATPase action by altering its assembly status.

Keywords: Histidine cluster, corticotrope tumor cells, AtT-20, subcellular fractionation, proton pump, luminal pH, blue native PAGE

1. Introduction

In eukaryotic cells, luminal pH affects the activities of resident enzymes and is a chief determinant of protein and lipid sorting. The luminal pH is uniquely different in each of the organelles of the secretory pathway and becomes progressively acidic as biosynthetic cargo approaches its destination (Paroutis et al., 2004). Luminal pH is chiefly determined by the activity of vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase), with contributions from proton leakage, ClC chloride channels and sodium/proton exchangers (NHEs) (Brown et al., 2009; Casey et al., 2010). V-ATPases are ancient, large multisubunit pumps which translocate protons across the endomembrane. V-ATPases are expressed in all eukaryotes. The mammalian V-ATPase is composed of 13 subunits that are assembled into two domains: a peripheral V1 domain of 8 proteins (A3B3CDE3FG3H) and a membrane intrinsic V0 domain comprising 5 proteins (a, c, c”, d, e) (Brown et al., 2009; Cotter et al., 2015; Forgac, 2007; Marshansky et al., 2014). A progressively acidified secretory pathway lumen is crucial to control the activity of many regulated secretory pathway enzymes; the prohormone convertase and carboxypeptidase require an acidic environment for maximal activity. These enzymes generate the C-terminal glycine-extended peptides that are substrates for the amidating enzyme, peptidylglycine α-amidating monooxygenase (PAM) (EC 1.14.17.3). Peptide amidation occurs maximally in an acidified granule lumen and also depends on a pH sensitive copper delivery system from ATP7A (Bauman et al., 2011; Kline et al., 2016).

The luminal pH of the secretory pathway is modulated in many physiological and pathological conditions. Despite its importance, little is known about the mechanisms of pH regulation in the secretory pathway of cells specialized for the production and storage of peptides. Normal functioning of the proton pump necessitates a precise pH sensing mechanism which can modulate its activity. Sensing luminal pH requires transmembrane proteins or complexes that can access both sides of the endomembrane. Although a pH dependent interaction of V-ATPase with cytosolic proteins such as cytohesin-2/Arf6, leading to endosomal acidification, has been well investigated (Hurtado-Lorenzo et al., 2006; Marshansky et al., 2014), luminal pH sensing mechanisms remain obscure. It has been hypothesized that the proton pump itself senses luminal pH by using luminal histidine residues in its V0a2 subunit (Marshansky, 2007; Marshansky et al., 2014). However, ambiguity regarding the folding and transmembrane topology of mammalian V0a-isoforms and their yeast orthologues (Vph1p/Stv1p) has prevented an experimental demonstration of this process (Marshansky et al., 2014).

We recently demonstrated that a well conserved histidine cluster in the linker region of PAM, which separates the two catalytic cores, imparts pH sensing capability to this integral membrane enzyme (Vishwanatha et al., 2014). We now demonstrate that PAM expressed in neuroendocrine cells interacts with V-ATPase. The cytosolic domain of PAM interacts directly with purified V1H. Pump assembly status differs in cells stably expressing PAM-1/H3A, a mutant in which the histidine cluster has been replaced by alanine residues (H3A). The histidine cluster in PAM affects association of the V1 complex to V0 in the membranes of the endocytic pathway of neuroendocrine cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells

AtT-20 cells stably expressing PAM-1 (Milgram et al., 1992) or PAM-1/H3A (Vishwanatha et al., 2014) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/Ham’s F-12 (DMEM/F-12; Invitrogen, USA)) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, USA), 10% NuSerum (Fischer Scientific, USA) and G418 (0.5 mg/ml) and passaged weekly using trypsin. Wildtype (WT) AtT-20 cells were maintained in the same medium without G418.

2.2. Transcriptomic analysis of WT AtT-20 cells

RNA was extracted and purified as described (Eipper-Mains et al., 2013). RNA sequencing was performed on barcoded libraries, 8 samples per lane, using 75 nt paired-end reads. The result was an average of 16.6 million reads per sample, followed by Bowtie alignment to identify transcripts (Mus musculus genome mm10, NCBI Build 38, 2011, allowing up to two mismatches); 70–78% of the reads aligned to known transcripts, as expected after removal of rRNA.

2.3. Differential centrifugation and subcellular fractionation

AtT-20 cells expressing PAM-1 were grown to confluence in 15-cm dishes and cells were briefly rinsed twice with complete serum free medium (CSFM) and harvested into fresh CSFM. After pelleting cells at 800 X g for 5 min, pellets were resuspended and homogenized at 4°C in 10 volumes (w/v) of homogenization buffer (0.32 M sucrose in 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, containing 0.3 mg mL−1 phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.16 mg mL−1 benzamidine, 0.02 mg mL−1 leupeptin, and 0.10 mg mL−1 lima bean trypsin inhibitor (inhibitor mix) using six strokes of a motor-driven glass Potter–Elvehjem homogenizer with a Teflon pestle. The homogenate was centrifuged for 5 min at 800 X g to pellet nuclei and debris and further subjected to differential centrifugation at 4°C as described (Bonnemaison et al., 2015a). Sucrose solutions were always made fresh in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 containing inhibitor mix. A post-nuclear P2 pellet was resuspended in homogenization buffer and loaded onto a discontinuous sucrose density gradient composed (bottom to top) of: 200 μL 2 M sucrose, 350 μL of 1.6 M sucrose, 350 μL 1.4 M sucrose, 350 μL 1.2 M sucrose, 200 μL 1 M sucrose, 200 μL 0.8 M sucrose, 200 μL 0.4 M sucrose, all in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (Oyarce and Eipper, 1995). After centrifugation at 120,000 X g in a TLS-55 rotor for two hours at 4°C, aliquots of 150 μL were collected from top to bottom and kept at −80°C until further analysis.

2.4. Western Blotting

Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis as described (Vishwanatha et al., 2014). Affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibodies (1:1000 dilution for each) used to visualize PAM included: PHM antibody JH1761 [raised to rPAM-1(37–382) (Milgram et al., 1997)]; exon 16 antibody JH629 [raised to rPAM-1(394–498) (Yun et al., 1995)]; PAL antibody JH 471 [raised to rPAM-1(463–864) (Steveson et al., 1999)]; CD antibody CT267 [raised to rPAM-1(965–976) (Rajagopal et al., 2009)].

2.5. Immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy

Cells grown on coverslips were fixed, blocked, permeabilized, immunostained and visualized as before (Vishwanatha et al., 2014; Vishwanatha et al., 2016). Primary antibodies used include GM130 (Golgi marker; BD Biosciences), and JH44 (to the C-terminus of ACTH(1–39)) (Schnabel et al., 1989), at 1:1000 dilution. Mouse hybridoma medium (clone 6E6) to recombinant PAM C-terminal domain (Milgram et al., 1997) and rat hybridoma medium (clone 1D4B) to LAMP-1 (Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa) were diluted 1:50. Fluorescent images were obtained on a Zeiss LSM510/Meta confocal laser-scanning microscope using a 63X oil immersion objective (NA 1.40).

2.6. Blue Native-PAGE (BN-PAGE)

2.6.1. Sample generation

AtT-20 cells expressing PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A were grown to confluence in 15-cm dishes. Cells were briefly rinsed with CSFM and harvested into fresh CSFM. Cells were pelleted at 1000 X g for 5 min and pellets were resuspended into ice cold lysis buffer (25 mM imidazole, 250 mM sucrose, pH 7.4) supplemented with protease inhibitors. Cells were homogenized using a motor-driven Potter Elvehjem homogenizer with a Teflon pestle at 4°C in 10 volumes (w/v) of lysis buffer and cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation (1000 X g for 5 min). The resulting supernatant was subjected to centrifugation for 15 min at 100,000 X g using a TL100 ultracentrifuge (Beckman) to yield pellets enriched in membranous organelles. Pellets were solubilized into NativePAGE sample buffer (50 mM BisTris, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and Ponceau S; Life Technology) containing 0.5% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) and protease inhibitors for 30–45 min at 4°C with occasional vortexing. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation for 15 min at 100,000 X g and the supernatant was subjected to one-dimensional BN-PAGE.

2.6.2. One-dimensional BN-PAGE

Subcellular fractions from non-transfected (WT) or PAM-1 AtT-20 cells were prepared as described above. Samples (10 μg protein) from both cell types were subjected to one-dimensional PAGE after addition of 0.05% Coomassie G250. Samples were separated on linear 3–12% (w/v) BisTris gels (Life Technology) in 15 mM BisTris, 50 mM Tricine, 0.05% Coomassie G250 running buffer and 15 mM BisTris (pH 7.0) as anode buffer. A mixture of native proteins (NativeMark, unstained protein standard, Life Technology) was used as a standard. For western blotting, the complexes were transferred onto PVDF membranes using NuPAGE transfer buffer (Life Technology) with 10% methanol using a constant current of 200 mA for 2.5 h. Blots were probed with antibodies against subunits of V0 (V0a1 and V0d1) or V1 (V1A and V1E1) to visualize the V-ATPase holocomplex and its assembly intermediates. Similar strips from PAM-1 cells were stained with PAL antibody (JH471) to visualize PAM complexes.

2.6.3. Two-dimensional BN-PAGE/SDS-PAGE

Two-dimensional BN-PAGE/SDS-PAGE analyses were carried out as described by the manufacturer (Life Technology). Briefly, after separating the complexes in one-dimension using the BN-PAGE buffer system described above, gel strips (~5 cm × 1 cm) were incubated with gentle shaking in 5 ml NuPAGE reducing solution containing 50 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 15–30 min at room temperature; the reaction was stopped by incubating the gel strips in quenching solution (NuPAGE LDS sample buffer with 20% ethanol and 5 mM DTT) for 15 min at RT. After reduction, BN-PAGE lanes were placed on top of 4–20% (w/v) Tris-Glycine Zoom SDS-PAGE gels and electrophoresed in parallel with molecular mass markers (Precision Plus Protein All Blue Standard, Bio-Rad). Proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes and subjected to Western blot analysis using PAM-CD antibody. The location of high molecular weight clathrin complexes (determined by western blot) was used to calibrate native molecular weights in the second dimension.

2.6.4. Identification of V-ATPase subunits after BN-PAGE/SDS-PAGE by mass spectrometry

Subcellular fractions from PAM-1 cells were separated by BN-PAGE/SDS-PAGE and visualized using the SilverSNAP Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Vertical strips of gels spanning the region known to contain PAM and V-ATPase complexes were excised using a sterile scalpel, placed into a sterile Eppendorf microfuge tube and frozen. Gel fragments were washed 4 times: first with 500 μL 60% acetonitrile containing 0.1%TFA; then with 5% acetic acid; then with 250 μL 50% H2O/50% acetonitrile; then with 250 μL 50% CH3CN/50 mM NH4HCO3. Gel fragments were washed with 250 μL 50% CH3CN/10 mM NH4HCO3 prior to drying in a Speed Vac. 1 μg of trypsin (Promega Trypsin Gold MS grade) freshly diluted into 10 mM NH4HCO3 was added to the dried gels pieces and incubated at 37°C for 18 hours (20). Briefly, peptides were separated on a nanoAcquity™ UPLC™ column (Waters) coupled to a Q-Exactive Plus mass spectrometer. High resolution tandem LC MS/MS data were collected by Higher-Energy Collisional Dissociation (HCD) with a 1.4 Da window followed by normalized collision energy of 32%. Resulting LC MS/MS data were analyzed and processed through Proteome Discoverer (linked to MASCOT and a Sequest Search engine).

2.7. Co-Immunoprecipitation

A confluent well of a 6-well dish of AtT-20 cells stably expressing PAM-1 or PAM-1/H3A was extracted into 300 μl of 20 mM NaTES, 10 mM mannitol, 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.4 (TMT) plus protease inhibitor cocktail. Cell extracts were clarified by centrifugation at 22,000 X g at 4°C for 20 min.

Supernatants were transferred into a new tube containing 1 μg of affinity-purified rabbit antibody to the PHM domain of PAM-1 or 1 μg of rabbit polyclonal antibody ATP6V1A (#17115–1-AP; ProteinTech Group) to the V1A subunit of V-ATPase; an equal amount (1 μg) of rabbit immunoglobulin was used as the control. Samples were tumbled overnight at 4°C and subjected to centrifugation at 22,000 X g at 4°C for 20 min. Protein A beads (20 μl of 50% slurry in TMT) were added to supernatants and samples were tumbled for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were washed twice with TMT and once with TM buffer (20 mM NaTES, 10 mM mannitol, pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors. Bound proteins were eluted into Laemmli sample buffer by heating at 95°C for 5 min. Samples were fractionated by SDS-PAGE on 4–15% Tris-Glycine gradient gels (Bio-Rad) and subjected to western blot analysis.

Adult mouse (C57bl/6, males and females) atria were used to assess an in vivo interaction between PAM and V-ATPase because atria express high levels of PAM (Braas et al., 1989; Muth et al., 2004). The atrial homogenates were prepared as previously described (Eipper et al., 1988). In brief, atrial tissue from 40 adult mice was collected into 0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM TES, pH 7.0 buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail and dispersed using a motor driven Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 2000 x g for 10 min to remove connective tissue, unbroken cells and nuclei; the supernatant was spun again at the same speed to remove more debris. Centrifugation of this supernatant at 145,000 x g for 60 min yielded a crude pellet containing the membranous organelles. These pellets were resuspended in TMT buffer and clarified aliquots were used for Co-IP experiments as described above. Along with antibody to V1A, an additional rabbit polyclonal antibody to the V1H subunit (ATP6V1H (#26683–1-AP), ProteinTech Group) was used for immunoisolation of mouse atrial PAM.

2.8. Preparation of recombinant V1H and PAM-CD for GST-pulldown assays

A bacterial expression vector encoding GST fused to full length V1H was used as described previously (Lu et al., 1998). To facilitate proper folding of the GST-V1H fusion protein, cells were grown at 20°C for 2 h after induction with 0.4 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The bacterial pellet was washed twice with PBS, resuspended in 30 ml PBS with protease inhibitor mix (1 mM DTT, 0.3 mg/ml benzamidine, 2 mM EDTA and 0.3 mg/ml PMSF) and lysed using a Misonix S4000 ultrasonic liquid processor (Qsonica, LLC, Newtown, CT). The GST-V1H fusion protein was purified using an Akta FPLC system fitted with a 5 ml GSTrap-4B column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) equilibrated with PBS (flow rate 0.5ml/min). Bound protein was eluted with a gradient to 10 mM reduced glutathione in the same buffer over 60 min. Free GST and other minor contaminants were removed by gel filtration chromatography on a Superose 6 10/300 GL column equilibrated with PBS. Recombinant PAM-CD was expressed and purified as described previously (Yun et al., 1995). Protein purity was verified by Coomassie Blue staining after SDS-PAGE; protein concentrations were determined by measuring absorbance at 280 nm and using the calculated extinction coefficient.

For in vitro binding assays, 1 μg PAM-CD was incubated with an equimolar amount (125 nM) of GST or GST-V1H overnight in binding buffer (PBS buffer with 0.05% NP-40 and protease inhibitors). GST proteins were then isolated by binding to glutathione Sepharose 4B beads (Bioworld, USA) for 1 hour at 4°C. Beads were washed once with binding buffer and bound proteins were eluted into Laemmli sample buffer by boiling at 95°C for 5 min. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by Coomassie staining (V1H and GST) or western blotting (PAM-CD) with the C-terminal antibody.

2.9. Association of V1 with membrane fractions

WT AtT-20 cells and cells stably expressing PAM-1 or PAM-1/H3A were grown in 10-cm dishes for 48–72 h. After rinsing the cells twice with serum free medium, cells were disrupted using a ball bearing homogenizer; membranous organelles were separated from debris and from cytosol by differential centrifugation (Stransky and Forgac, 2015). Protein concentrations were measured using the BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL); after separation by SDS-PAGE, samples were analyzed by western blotting

3.0. Statistical Analysis

Results are plotted as bar graphs along with their mean values. Single comparisons of the mean values were performed by Student’s t test (two sample, one tail). Differences considered statistically significant are reported with a p value; p > 0.05 was reported as non-significant. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

3. Results

3.1. V-ATPase localization in peptidergic cells - immunofluorescence

Expression of the 13 subunits of V0 and V1 is cell type specific. To identify the major transcripts expressed in WT AtT-20 cells, we subjected polyA RNA to RNASeq analysis (Supplemental Table 1). Based on transcript abundance, the V0 membrane sector consists of a1 or a2, b, c, c”, d1, and e. The V1 peripheral sector consists of A, B2, C1 or C2, D, E1, F, G1 and H (summarized in Table 1). The cells also express two essential V-ATPase complex accessory proteins, ATP6AP1 (Ac45 (Jansen et al., 1998)) and ATP6AP2 (PRR/M8–9 (Nguyen and Muller, 2010)), along with CCDC115 and TMEM199, recently described critical factors responsible for assembly of the V0 complex in the endoplasmic reticulum (Miles et al., 2017).

Table 1. Transcriptomic analysis of AtT-20 cells.

FPKM values for different V-ATPase subunits and accessory proteins in WT AtT-20 cells are given along with specific antibodies used in this study and their source. Complete FPKM data are in Supplemental Table 1.

| Gene | Mean FPKM value | Antigen | Working dilution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V0 complex | ||||

| ATP6V0A1 | 38 | V0al | 1:1000 | (#13828–1-AP) ProteinTech Group |

| ATP6V0A2 | 8 | |||

| ATP6V0B | 359 | |||

| ATP6V0C | 191 | |||

| ATP6V0D1 | 117 | V0dl | 1:1000 | (#18274–1-AP) ProteinTech Group |

| ATP6V0E | 234 | |||

| V1 complex | ||||

| ATP6V1A | 104 | V1A | 1:1000 | (#17115–1-AP) ProteinTech Group |

| ATP6V1B2 | 187 | |||

| ATP6V1C1 | 47 | |||

| ATP6V1C2 | 24 | |||

| ATP6V1D | 112 | |||

| ATP6V1E1 | 232 | V1E1 | 1:1000 | (#15820-l-AP) ProteinTech Group |

| ATP6V1F | 460 | |||

| ATP6V1G1 | 156 | V1G1 | 1:1000 | (#16143–1-AP) ProteinTech Group |

| ATP6V1G2 | 2 | |||

| ATP6V1H | 154 | V1H | 1:1000 | (#26683-l-AP) ProteinTech Group |

| Accessory/Assembly factors | ||||

| ATP6VAP1 | 181 | |||

| ATP6VAP2 | 177 | |||

| CCDC115 | 131 | |||

| TMEM199 | 98 |

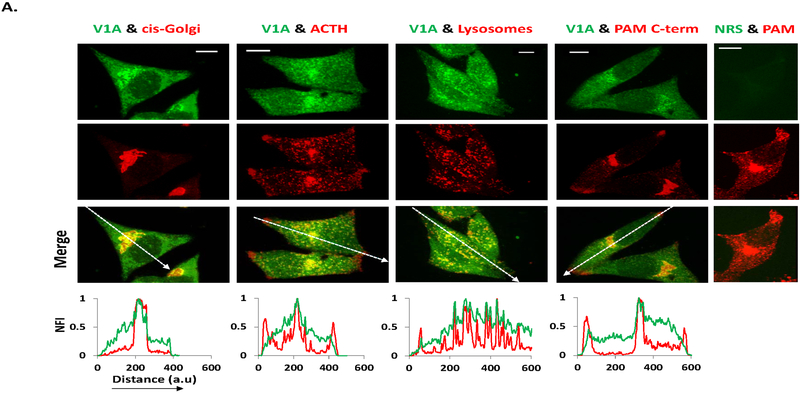

We next evaluated the subcellular localization of endogenous V-ATPase in AtT-20 PAM-1 cells (Milgram et al., 1992). Antiserum to the V1A subunit, which produced a single band of the expected molecular weight when used for immunoblot analysis was utilized (Fig. S1). Similar attempts to identify V0 subunit antisera that could be used to stain fixed cells were not successful. In order to study localization of V-ATPase complexes in AtT-20/PAM-1 cells, antisera to a cis-Golgi marker, a secretory granule marker (ACTH), a lysosomal marker (LAMP1) and PAM were utilized. Considerable colocalization of V1A with the cis-Golgi marker along with extensive co-localization of V1A and ACTH was observed (Fig.1). V1A staining was also strongly colocalized with LAMP1 staining (Fig.1), which showed occasional co-labeling with PAM antibodies (Milgram et al., 1993; Sobota et al., 2009; Steveson et al., 1999). Diffuse V1A staining was also observed throughout the cytoplasm, presumably corresponding to the uncoupled peripheral V1 domain.

Fig.1. PAM and V-ATPase colocalize in secretory and endocytic compartments.

The steady state distribution of the peripheral V1 subunit of V-ATPase (V1A) along the secretory pathway of stably transfected AtT-20/PAM-1 cells. The distribution of endogenous V1A staining was compared with that of GM130 (cis-Golgi marker), the COOH-terminus of ACTH (mature secretory granules) and LAMP1 (lysosomes). Confocal microscopy analysis of (single image) V1A (green) indicated a punctate staining pattern of the membrane associated V1A corresponding to Golgi region and secretory granules where it extensively overlaps with PAM (red). A modest amount of green fluorescence was also observed throughout the cytoplasm, indicating unassembled V1A. When the V1A antibody was replaced by normal rabbit serum (NRS, right-most panel), staining was eliminated. Representative line scans of the merged images demonstrate colocalization between V1A and other markers. NFI, normalized fluorescence intensity. Scale bar =10 μm.

We were especially interested in sites at which V1A and PAM-1 were co-localized. In order to focus on membrane-associated forms of PAM, we utilized a monoclonal antibody to its C-terminal region (6E6). Unlike antisera to the PHM domain, which highlight soluble PHM stored in secretory granules, antisera to the C-terminal region of PAM yield a strong signal in the Golgi region, where both biosynthetic and endocytic vesicles accumulate. Extensive colocalization of V1A and the C-terminal region of PAM was observed in the Golgi region and sparsely in vesicular structures near the tips of the cells (Fig.1).

3.2. V-ATPase localization in peptidergic cells – subcellular fractionation

To further explore the subcellular compartments in which PAM and V-ATPase could coexist, we turned to differential centrifugation followed by sucrose gradient fractionation. Western blot analysis allowed us to utilize additional V-ATPase antibodies (Table 1). Post-nuclear pellet fractions (P2) from rat anterior pituitary (Fig. 2A) and AtT-20/PAM-1 cells (Fig. 2B) were resuspended and separated on linear sucrose gradients. Equal volumes from each fraction were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies to V-ATPase subunits, markers for late endosomes, recycling endosomes, secretory granules, and lysosomes. Cells producing growth hormone (somatotropes) and prolactin (lactotropes) are the major cell types in the anterior pituitary; AtT-20 cells are corticotropes, a minor anterior pituitary cell type. In the anterior pituitary gradient, late endosomes (CPD, PAM-1) localized near the top of the gradient and extended into denser fractions (Oyarce and Eipper, 1995). In the AtT-20 gradient, recycling endosomes (syntaxin 13) were recovered in lighter fractions than lysosomes (LAMP1), which extended into the denser fractions that contained secretory granules (PC1).

Fig.2. Distribution of V-ATPase subunits and PAM after sucrose gradient fractionation.

The P2 pellet obtained by differential centrifugation of rat anterior pituitary or AtT-20/PAM-1 cells was resuspended in homogenization buffer and fractionated on a sucrose density gradient. Fractions collected from the top of the gradient were analyzed for the steady state distribution of V-ATPase subunits and PAM along with markers of subcellular organelles. Fractions from gradients generated using rat anterior pituitary (A) or AtT-20/PAM-1 cells (B) were subjected to western blot analysis; equal volumes of each fraction were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane and probed with the antibodies indicated. Intact PAM-1 and PHM were visualized with PHM antibody (JH1761). Soluble PHM and 63 kDa PC1 localize to secretory granules (Gra). CPD, Rab 7 and syntaxin 13 migrate with endosomes (Endo) and LAMP1 is a lysosomal marker (Lyso). Western blot analyses of P2 sucrose gradient fractions showed intact PAM in granule and endosomal fractions, along with V1 and V0 subunits. In = input. (C) Percent distribution of V-ATPase subunits and PAM in endosomes, lysosomes and matured granules was calculated from signal intensities of pooled fractions from Fig.2B and the values are represented as histograms; average from 3 experiments.

Consistent with its reversible association with membranes, V1A was broadly distributed throughout the gradients for both anterior pituitary and AtT-20/PAM-1 lysates. A distinct peak of V0a1 and V0d1, along with intact PAM-1, was apparent near the top of the anterior pituitary gradient (Fig. 2A). Although both V0a1 and V0d1 were detectable in the dense, secretory granule enriched fractions of the anterior pituitary gradient, the ratio of V0a1 to V0d1 signal was greatly diminished compared to that observed in the lighter fractions. In the AtT-20/PAM-1 gradient (Fig. 2B), the V0a1 and V0d1 patterns were more similar to each other; both subunits were detected in fractions enriched in syntaxin 13 (late endosomes), LAMP1 (lysosomes) and PC1 (secretory granules). Intact PAM-1 has been identified in the TGN, secretory granules and multiple endocytic compartments in AtT-20 cells; both V0a1 and V0d1 showed extensive overlap with PAM-1.

Non-saturated images from the AtT-20/PAM-1 gradient (Fig. 2B) were densitized and the percentage of the pooled signal for each antigen in representative fractions was plotted (Fig. 2C). V0a1 and V0d1 were distributed in a similar manner, peaking in the region that encompasses secretory granules. V1A was more broadly distributed, with significant levels in the endosomal, lysosomal and secretory granule enriched fractions (Fig. 2C, histogram). The modest amount of V1A recovered in the lightest fractions may represent dissociation that occurs during fractionation. Intact PAM-1 was recovered from fractions enriched in endosomes and secretory granules (Fig. 2C, histogram). In complete agreement with our immunofluorescence results, subcellular fractionation identified multiple compartments in which VATPase and PAM-1 could interact.

3.3. Blue Native PAGE analysis of V-ATPase and PAM complexes

In order to determine whether PAM and V-ATPase co-exist in a complex, we utilized blue native-PAGE. To enrich for protein complexes associated with the secretory/endocytic pathway, P2 fractions from WT and PAM-1 cells were solubilized with 0.5% dodecylmaltoside (DDM) containing sample buffer. After electrophoretic separation of the high molecular weight native complexes, PVDF membranes were probed with antibodies against V0 subunits a1 and d1 and V1 subunits E1 and A, revealing the presence of multiple complexes (Fig. 3A). The holoenzyme, V0 and V1 (total mass 800 ± 25kDa), was recognized by all four antibodies. Large amounts of the V0 complex (total mass 520 ± 20 kDa) were detected by both V0 subunit antibodies. Various presumptive assembly intermediates (V0, 620 kDa; V1, 620, 680 & 700 kDa) were recognized to different extents by the different antibodies (Fig. 3A).

Fig.3. Blue native PAGE analysis reveals complexes of PAM and V-ATPase.

(A) Dodecyl β-D- maltoside (0.5%) solubilized membrane proteins prepared from WT AtT-20 or PAM-1/AtT-20 cells were separated by 1D-blue native PAGE. Native molecular weight markers are indicated. After transfer to a PVDF membrane under native conditions, blots were probed with antibodies to the V0 or V1 subunits of V-ATPase. The western blots demonstrated the presence of V-ATPase holocomplex and assembly intermediates (V0, 620 kDa (♣); V1, 620 (♦), 680 (♥) & 700 kDa (♠)). (B) Blots from PAM-1/AtT-20 cells were probed with antibody to the PAL region (JH471) or the C-terminus (CT267). Multiple high molecular weight complexes containing PAM were apparent against using both antibodies. (C) Single gel lanes from one dimensional blue native PAGE separation of AtT-20/PAM-1 cell extracts were excised; proteins in this lane were reduced and denatured and then fractionated by SDS-PAGE. After transfer to a PVDF membrane, PAM proteins were visualized using a C-terminus antibody and antibodies to the indicated V-ATPase subunits; relative positions of denatured molecular weight markers are indicated on the left and native molecular weight markers are shown above the blots. (D) A full 2-dimensional blot for PAM probed with C-terminal antibody (CT267), as in Panel C, is shown, highlighting the presence of multiprotein complexes containing PALm and CD, the major proteolytic fragments of PAM-1. Clathrin heavy chain was identified by immunoblotting. Native molecular weight markers are shown above; cartoons on the right show PAM-1 and its major cleavage products (yellow=PHM; green=PAL). This experiment was repeated three times using separate lysates, with similar results.

Analysis of the same samples using antisera to the PAL domain or the cytosolic domain of PAM-1 revealed a heterogeneous collection of high molecular weight PAM complexes (Fig. 3B). Similar lysates prepared from mouse pituitary also showed the presence of heterogeneous high molecular weight complexes of PAM (results not shown). PAM complexes were observed throughout the regions that contained intact V-ATPase complexes, assembly intermediates and the V0 complex.

To further explore these high molecular weight V-ATPase and PAM complexes, gel lanes containing samples from AtT-20/PAM-1 cells fractionated in one dimension were reduced and denatured before separation in the second dimension by SDS-PAGE. After transferring the denatured proteins to a PVDF membrane, the V0 and V1 subunit antibodies were used to explore the nature of each complex. As expected, antisera to V1A, V1G1, V0a1 and V0d1 each recognized a protein of the expected size contained in a vertical column representing the ‘footprint’ of an ~800 kDa protein complex (Fig. 3C). The V0a1 and V0d1 antibodies also each recognized a protein of the expected size in a vertical column representing the ‘footprint’ of an ~520 kDa complex. The ~700 kDa complex recognized by the V1A antibody did not contain either of these V0 subunits.

PAM proteins were visualized using an antibody to the C-terminal domain of PAM (Fig. 3C (upper panel) and Fig. 3D). Fractionation of the control sample by denaturing SDS-PAGE (2nd dimension) revealed a heterogeneous collection of PAM-1 complexes. It is also interesting to note that the major transmembrane proteolytic products of PAM-1 (PALm and the TMD-CD fragment) showed similarly heterogeneous patterns, reflecting their presence in multi-protein complexes (Fig. 3D).

In order to confirm the presence of a full complex of V-ATPase subunits and PAM in the same region of the blue native gels, vertical strips of the two-dimensional SDS gels were analyzed by mass spectrometry. PAM-1 was identified, with a sequence coverage of 20%. Two V0 subunits (V0a1 and V0d1) and all eight V1 subunits were identified in the same slice (Table 2). Sequence coverage ranged from 30% for both V0 subunits to 88% for V1F. The same vertical slice also contained secretory granule V-ATPase accessory proteins Atp6ap1 (Ac45) and Atp6ap2 (PRR), along with Vma21, an integral membrane protein essential for V-ATPase assembly (Table 2). Various other proteins reported to interact with the V-ATPase complex were also identified in this analysis (Table 2). The presence of the V-ATPase subunits, along with its accessory proteins and various interactors supports the appearance of multiple assembly intermediates, as observed on the 1D-gel (Fig. 3A).

Table 2. Identification of V-ATPase subunits and their interactors in the MS/MS screen.

Identification of proteins after two dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE by mass spectrometry. Dodecyl β-D- maltoside (0.5%) solubilized membrane proteins (10μg) prepared from PAM-1/AtT-20 cells were separated by 1D-blue native PAGE. After silver staining, 4 vertical columns covering the range from 700 to 1000 kDa (native molecular weight) were cut and subjected to mass spec analysis. Data for the slice containing ~800 kDa complexes contained eight V1 subunits along with V0d1, V0a1 and PAM. Major V-ATPase interactor proteins reported to form high molecular weight complexes are listed along with known PAM-1interactors. Expected molecular mass (MW) and percent coverage for each protein identified are given.

| Proteins | MW | % Coverage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptidyl-glycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase (PAM) | 108894 | 20.4 | |

| V-type proton ATPase V0-subunits | |||

| subunit a isoform 1, 116 kDa (ATP6V0al) | 96404 | 29.8 | |

| subunit dl (ATP6V0dl) | 40275 | 30.8 | |

| V-type proton ATPase Vl-subunits | |||

| catalytic subunit A (ATP6V1A) | 68283 | 46 | |

| subunit B, brain isoform (ATP6V1B2) | 56515 | 36.8 | |

| subunit C1 (ATP6V1C1) | 43860 | 52.1 | |

| subunit D (ATP6V1D) | 28351 | 43.7 | |

| subunit El (ATP6V1E1) | 26141 | 57.1 | |

| subunit F (ATP6V1F) | 13362 | 88.2 | |

| subunit G1 (ATP6V1G1) | 13716 | 60.2 | |

| subunitH (ATP6VlH) | 55819 | 25.9 | |

| Accessory proteins | |||

| V-type proton ATPase subunit SI (ATP6AP1/Ac45) | 50975 | 9.1 | (Jansen et al., 1998) |

| Renin receptor/M8–9 (ATP6AP2) | 39067 | 15.1 | (Nguyen and Muller, 2010) |

| Vacuolar ATPase assembly integral membrane protein (VMA21) | 11358 | 55.4 | (Malkus et al., 2004) |

| V-ATPase interactor proteins | |||

| S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 (SKP1) | 18660 | 27.6 | (Kane, 2012; Seol et al, 2001) |

| ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6) | 20069 | 22.9 | (Hurtado-Lorenzo et al, 2006) |

| AP-2 complex subunit mu (AP2M1) | 49623 | 21.6 | (Geyer et al, 2002) |

| Ras-related protein Rab-35 (RAB35) | 23011 | 24.4 | (Merkulova et al, 2015) |

| Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A (ALDOA) | 39331 | 42.6 | (Merkulova et al, 2015) |

| Presenilin-1 (PSEN1) | 52606 | 19.9 | (Li et al, 2012; Merkulova et al, 2015) |

| Vesicle-associated membrane protein 8 (VAMP8) | 11444 | 54.5 | (Merkulova et al, 2015) |

| Charged multivesicular body protein 6 (CHMP6) | 23401 | 20.5 | (Merkulova et al, 2015) |

| WD repeat-containing protein 7 (WDR7) | 163345 | 10.9 | (Merkulova et al, 2015) |

| Integrinbeta-1 (ITGB1) | 88173 | 12.7 | (Merkulova et al, 2015; Skinner and Wildeman, 1999) |

| Protein S100-A11 (S100A11) | 11075 | 26.5 | (Merkulova et al, 2015) |

| Chloride channel CLIC-like protein 1 (CLCC1) | 60582 | 22.6 | (Merkulova et al, 2015) |

| Golgin subfamily A member 2 (GOLGA2) | 113209 | 22 | (Merkulova et al, 2015) |

| Actin, cytoplasmic 2 (ACTG1) | 41766 | 37.3 | (Serra-Peinado et al, 2016) |

| PAM-1 interactor proteins | |||

| Copper-transporting ATPase 1 (ATP7A) | 161855 | 9.6 | (Otoikhian et al, 2012) |

| AP-2 complex subunit mu (AP2M1) | 49623 | 21.6 | (Bonnemaison et al, 2015) |

3.4. V-ATPase/PAM molecular association in peptidergic cells

The observations from immunofluorescence, subcellular fractionation and blue native PAGE suggest a spatial co-occurrence of PAM and V-ATPase which may involve their direct association. To explore the possibility that PAM and V-ATPase might be contained in the same complex, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays using detergent solubilized particulate fractions prepared from AtT-20/PAM-1 cells. Probing the V1A immunoprecipitate with a V0d1 antibody confirmed its presence, consistent with the presence of intact V-ATPase (Fig. 4A, left side). Probing with the PAM antibody revealed the presence of intact PAM; neither V1A nor PAM was detected in the control (IgG) immunoprecipitate. Although a PAM linker domain antibody efficiently precipitated PAM, co-immunoprecipitation of V1A was not observed (Fig. 4A, right side); the epitope recognized by this PAM antibody could be blocked in a PAM/VATPase complex or the sensitivity of the V1A antibody could preclude its detection in small amounts of complex.

Fig.4. PAM-1 interacts with V-ATPase in PAM-1/AtT-20 cells.

(A) PAM-1/AtT-20 lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) using V1A antibody, PAM Exon 16 antibody or control rabbit IgG, as indicated. Inputs (1/40th the amount used for immunoprecipitation) and immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and blotted for PAM, V1A and V0d1. The V1A antibody, which efficiently precipitated V1A, also precipitated PAM-1 and V0d1. The PAM Exon 16 antibody (right side), which efficiently precipitated PAM, did not precipitate V1A or V0d1. This experiment was repeated three times with identical results. (B) Samples from mouse atrial tissue were used to probe an in vivo interaction between PAM and V-ATPase. The detergent solubilized homogenates were immunoprecipitated with PAM-CD antibody, V1A antibody, V1H antibody or control rabbit IgG as given. Similar to AtT20 cells, the V1A antibody efficiently precipitated both V1A and PAM from atrial tissue. The V1H antibody also showed similar affinity towards PAM. The IP complexes from both V1A and V1H additionally also contained V1E1 and V1G1 subunits along with PAM. I, input; IgG, control antibody; B, bound. (C) Purified PAM-CD binds GST-V1H in vitro. Purified PAM-CD (1 μg) was incubated overnight at 4°C with equimolar amounts of GST-V1H fusion protein or GST. GST-V1H and GST were isolated by binding to glutathione agarose beads; after washing, bound proteins were eluted using Laemmli sample buffer. Inputs (50% of the amount used for binding) and duplicate samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. GST-V1H and GST were visualized with Coomassie brilliant blue; PAM-CD, which stains poorly with Coomassie, was visualized using an antibody to PAM-CD. PAM-CD recovered in the bound fractions was plotted as percentage of input. Data from three separate experiments were quantified; each bar represents mean ±SD.

To search for the in vivo interaction of endogenous PAM and V-ATPase, we analyzed adult mouse atrium, the tissue in which PAM is most highly expressed. Antisera to V1A and V1H successfully immunoprecipitated the V1 complex (Fig. 4B). Both the V1A and V1H immunoprecipitates showed presence of V1E1 in them (Fig 4B, lower part). Co-immunoprecipitation of PAM was observed with both the V1A and V1H antibodies (Fig.4B, upper panel). As observed in AtT-20/PAM-1 cells, atrial PAM immunoprecipitates did not contain V1A or V1H (Fig 4B). Taken together, the results from coimmunoprecipitation experiments suggest that PAM is present in a complex that also contains the VATPase holocomplex.

Based upon the topology of membrane PAM-1 and the presence of high molecular weight complexes containing the TMD/CD fragment of PAM-1 (Fig. 3D), we hypothesized that PAM-CD might interact with a V1 subunit. We selected the V1H subunit for in vitro binding assays because this subunit was previously shown to be a direct modulator of V-ATPase activity (Benlekbir et al., 2012; Cotter et al., 2015; Kane, 2012; Marshansky et al., 2014). We carried out GST-pulldown experiments using purified recombinant GST-V1H fusion protein (Lu et al., 1998) and PAM-CD (residues 896–976) (Yun et al., 1995). Bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue or western blotting (Fig. 4C). In vitro binding was repeated three times with duplicate samples and the average amount bound is plotted as a percentage of the input (Fig. 4C bar graph). PAM-CD was readily detected in the lanes with V1H, demonstrating a direct interaction between this region of PAM and at least one of the subunits of V-ATPase.

3.5. PAM-1/H3A mutant displays diminished interaction with V-ATPase

To determine whether its pH-sensitive luminal His-cluster played a role in the formation of high molecular weight PAM complexes or in the ability of PAM-1 to interact with V-ATPase, we used AtT-20 cells stably expressing PAM-1/H3A, which has full enzymatic activity (Vishwanatha et al., 2014). When detergent solubilized lysates prepared from AtT-20 cells expressing PAM-1 or PAM-1/H3A were subjected to immunoprecipitation with the V1A antibody (Fig. 5A), the fraction of PAM-1/H3A that could be immunoprecipitated was markedly reduced compared to PAM-1; this difference could reflect defective endocytic trafficking or an altered ability of PAM-1/H3A to interact with V1A.

Fig. 5. PAM-1/H3A fails to form native complexes with V-ATPase.

(A) Lysates prepared from AtT-20 cells expressing PAM-1 or PAM-1/H3A were subjected to immunoprecipitation as described in Fig. 4A. PAM proteins were visualized with the Exon16 antibody (exposure time, 40 sec). I = input (1/40th of the amount used for immunoprecipitation); B = bound; IgG, control. (Inset) longer exposure (460 sec) of the control and PAM IP samples from both PAM-1 and H3A cells are shown. Bar graph on the right shows the percentage of the blotted PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A that was immunoisolated with the V1A antibody. Each bar represents the mean of two separate IP experiments performed in triplicate ± SD. Detergent solubilized membrane samples prepared from PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A cells were used to compare protein complexes. (B). Duplicate samples of PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A membrane fractions contained similar levels of PAM proteins (PAM-CD antibody). Coomassie blue staining demonstrated similar loading of samples. (C) Duplicate samples from PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A membranes were separated by 1-D blue native PAGE as described earlier and were probed with CD-antibody to reveal PAM complexes. High molecular weight PAM complexes were barely detectable in PAM-1/H3A samples. (D) Identical 1-D blots were probed with antibodies to V0a1, V0d1, V1H and V1A. The V-ATPase holocomplex and assembly intermediates are marked on the right. Dashed line indicates a shift in the mobility of intermediate complexes in the V0a1 and V1E1 blots. Bar graph on the right shows quantification of V1A intermediate complexes from two independent experiments expressed as ratios of the 825 kD V-ATPase holocomplex in both PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A cells (*, p < 0.05, n = 4).

To further evaluate this result, we utilized blue native PAGE to compare the high molecular weight complexes formed by PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A. Expression of PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A in detergent solubilized samples was first evaluated using 4–15% gradient SDS-PAGE and a PAM-CD-antibody (Fig. 5B); expression levels of intact PAM-1 were similar, with the expected decline in levels of cleavage products more localized to endosomes (PALm, 22kD, 19kD). Simultaneous 1-D blue native PAGE analysis of PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A samples revealed the greatly diminished ability of PAM-1/H3A to form high molecular weight complexes (Fig. 5C). When PAM-1/H3A samples were denatured and subjected to SDS-PAGE in the second dimension, a weaker C-terminal antibody band pattern was also observed (data not shown). Interestingly, when similar blots were probed with antibodies against several V-ATPase subunits (V0a1, V0d1, V1A and V1H), the blots revealed subtle changes in holocomplex and assembly intermediate mobility in PAM-1/H3A vs PAM-1 cells (Fig. 5D; indicated by the dashed line). The relative content of intermediate complexes of V1 subunits was significantly different in PAM-1/H3A cells, indicating an alteration in proton pump assembly in PAM-1/H3A cells (Fig. 5D, bar graph).

3.6. Expression of PAM alters steady state levels of V1 subunits of V-ATPase in AtT-20 cells

In order to determine whether a change in the levels of different V-ATPase subunits could contribute to the observed changes on one dimensional BN-PAGE gels, we compared their steady state levels in WT, PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A AtT-20 cells. SDS-lysates containing equal amounts of protein (10 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and examined using antibodies against four V1 subunits and two V0 subunits (Fig.6A). Levels of the four V1 subunits examined (A, H, E1 and G1) were significantly lower in both PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A lysates than in WT lysates. As shown in Fig.6B, levels of V1A, V1H, V1E1 and V1G1 were reduced to a similar extent in PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A lysates. In contrast, levels of the two V0 subunits examined (a1 and d1) were similar in all three cell lines (Fig.6A and B). A change in steady state levels of V0 or V1 subunits cannot explain the absence of high molecular weight PAM complexes in PAM-1/H3A lysates.

Fig. 6. Expression of PAM-1 or PAM-1/H3A affects V1 subunit levels in AtT-20 cells.

Non-transfected AtT-20 cells (WT) or cells stably expressing PAM-1 or PAM-1/H3A were harvested into SDS-lysis buffer. (A) Equal amounts of protein (10 μg) from triplicate samples of each line were separated by SDS-PAGE and examined using the indicated V1 and V0 antibodies. A representative western blot is shown. Coomassie staining demonstrated equal loading. (B) Signals for individual V-ATPase subunits in PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A cells were compared to WT levels. Bar graph shows ratio of individual V1 or V0 subunits in PAM-1 or PAM-1/H3A lysates to WT levels, which were set to 1.0 (**, p < 0.001; n.s.=non-significant, n = 6).

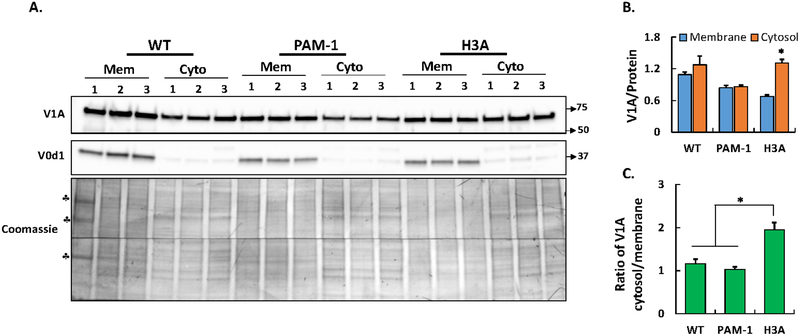

3.7. V-ATPase assembly is altered in PAM-1/H3A cells

One-dimensional BN-PAGE analysis of PAM-1/H3A cell lysates demonstrated an increase in assembly intermediates, suggesting the occurrence of altered pump assembly (Fig. 5D). In addition, coimmunoprecipitation demonstrated the decreased ability of PAM-1/H3A to interact with V-ATPase (Fig. 5A). In order to evaluate V-ATPase assembly status in a different manner, we prepared membrane and cytosolic fractions from WT, PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A cells (Fig. 7A). As expected, V0d1 was recovered almost entirely from the membrane fraction (Fig. 7A). Since V1A levels in WT AtT-20 cells exceeded V1A levels in PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A cells (Fig. 6), equal amounts of membrane and cytosolic protein were analyzed; V1A levels in the membrane fraction declined in PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A cells, as observed in total cell lysates (Fig. 7B). Strikingly, cytosolic V1A levels were higher in PAM-1/H3A cells. The ratio of cytosolic to membrane V1A is significantly increased in PAM-1/H3A cells (Fig. 7C). Our results from immunoprecipitation (Fig. 5A) and blue native PAGE experiments (Fig. 5D) suggest reduced V1 association with its membrane sector owing to its inability to interact with PAM-1/H3A.

Fig. 7. PAM-1/H3A cells display altered V-ATPase assembly.

(A) AtT-20 cells (WT, PAM-1 and PAM-1/H3A) were grown to confluence and cell homogenates were separated into membrane (mem) or cytosolic (cyto) fractions. Triplicate samples (15% by volume from both fractions) from each cell line were separated on SDS-PAGE and subjected to western blotting for V1A and V0d1. Coomassie blue staining of both slices used for western blotting demonstrated similar loading of samples (♣bands in the first lane represent molecular weight markers mixed with WT membrane sample 1). As expected, V0d1 was recovered almost entirely in the membrane fraction. The amount of V1A associated with the membrane fraction indicates the presence of V-ATPase holocomplex. A representative western blot is shown. (B) V1A signal from each sample was normalized to loaded protein obtained by gel density scans of Coomassie stained PVDF membrane after Western blot analysis. (C) Bar graph shows ratio of cytosolic V1A to the membrane associated V1A for each cell line. Non-saturated images were quantified. (*, p < 0.05; Membrane & cytosol, n = 3).

Discussion

Luminal pH is uniquely different in each of the organelles of the secretory and endocytic pathways of peptidergic cells and becomes progressively acidic as cargo approaches its destination. The gradient of luminal pH is actively modulated by the proton pumping action of the V-ATPase (Forgac, 2007; Kawasaki-Nishi et al., 2003). Proper proton pump function necessitates a precise pH sensing mechanism. Despite its importance in normal cellular physiology, little is known about the mechanisms of pH regulation in the secretory and endocytic pathways. A luminal pH sensor protein for V-ATPase has thus far not been reported in peptidergic cells. Sensing luminal pH requires transmembrane proteins or complexes that can access both sides of the endomembrane. Apart from the core subunits which make up the V1 and V0 complexes of VATPase, the essential requirements of two accessory subunits of the proton pump (Ac45 and PRR, originally isolated from bovine chromaffin granules as interactors with the V-ATPase) are well investigated in multiple experimental systems (Jansen et al., 1998; Jansen et al., 2008; Jansen et al., 2010; Nguyen and Muller, 2010). PAM, like these two proteins, is a type I integral membrane protein with a large luminal N-terminal domain and a short cytosolic C-terminus (Ichihara and Kinouchi, 2011; Jansen et al., 1998).

PAM and V-ATPase coexist on endomembranes of peptidergic cells

Results from subcellular fractionation experiments using linear sucrose gradients show that most of the intact PAM localizes with the V0 and V1 subunits in endomembrane fractions. A significant amount of V1A and PAM-1 was also observed towards the top of the gradient along with syntaxin 13, a marker for recycling endosomes (Fig. 2B). PAM, which reaches the plasma membrane following exocytosis, is rapidly internalized and returns to the trans-Golgi network through pathways involving its regulated entry into multivesicular bodies and then into intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) (Back et al., 2010). An essential role for V-ATPase in endocytic trafficking has been demonstrated in multiple systems (Hurtado-Lorenzo et al., 2006; Kissing et al., 2015; Lafourcade et al., 2008; Vaccari et al., 2010).

The co-distribution of PAM and V-ATPase in endomembranes and the results from coimmunoprecipitation experiments suggested the possibility of a transient, but direct in vivo interaction between these proteins. Detergent solubilized membranes from PAM-1 cells revealed the presence of multiple high molecular weight PAM complexes when probed with PAM antibodies (Fig. 3B). Lysates prepared from mouse pituitary showed similar high molecular weight complexes of PAM and the VATPase, indicating that complexes observed in AtT-20 cells are representative of in vivo interactions.

After blue native PAGE followed by SDS-PAGE, PAM-1 was found in a horizontal streak, indicating its presence in multiple complexes ranging in mass from 300–1000 kDa. PAM was previously shown to interact with a number of secretory and endocytic proteins along with several cytosolic proteins (Bonnemaison et al., 2015a; Chen et al., 1998; Francone et al., 2010; Mains et al., 1999; Otoikhian et al., 2012). Results from 2-D gels and mass spectroscopy analysis confirm the presence of all of the core V-ATPase subunits in a footprint along with PAM. The regulator of ATPase in vacuoles and endosomes or RAVE complex, which consists of Rav1p, Rav2p, and Skp1p, plays an essential role in the stable assembly of yeast V-ATPase (Kane, 2006; Kane, 2012). Recently, rabconnectins, Rav1 homologs in Drosophila and mice, have been reported to function similarly in regulating the disassembly of these V-ATPases (Kane, 2012). In our MS/MS screen we identified Skp1p in the 800 kDa foot print along with other known VATPase interactor proteins such as aldolase, Arf6, actin, GOLGA2 and AP-2 (Table 2). The presence of multiple interactor proteins along with PAM-1 may reflect a transient interaction with V-ATPase in several secretory and endocytic pathway compartments in our samples.

PAM interacts with V-ATPase to convey information about luminal pH

The observed spatial co-occurrence of PAM and V-ATPase could clearly allow an interaction between them. Results from co-immunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 4A &B) and GST-pull down experiments suggest a direct interaction of PAM with at least one V1 subunit (Fig. 4C). Interaction of PAM-CD with V1H is particularly interesting as the V1H subunit plays a crucial role in regulating the activity of the holocomplex by causing the dissociation of V1 from V0. A direct interaction of PAM-CD with the V1H subunit could thus help PAM in transmembrane signaling to the V-ATPase to convey luminal pH information. As seen previously, transmembrane signaling of PAM involves contributions from both the luminal and cytosolic domains (Bonnemaison et al., 2015b). When we utilized cells expressing PAM-1/H3A, which lacks the luminal pH sensing histidine cluster (Vishwanatha et al., 2014) to measure extent of association with V-ATPase, very little PAM-1/H3A was co-immunoprecipitated by the V1A antibody (Fig. 5A) and PAM-1/H3A showed diminished ability to form multiprotein complexes (Fig. 5C).

The assembly of peripheral V1 subunits and the association of V1 complexes with membrane embedded V0 are not fully understood in mammalian V-ATPases. However earlier studies on yeast, fungi and plant V-ATPase provide possible clues. Assembly of V1 and V0 sectors proceeds independently. Through in vitro reconstitution studies it has been shown that various smaller complexes of V1 can be formed in the absence of any one subunit; these complexes could then be incorporated into larger, membrane-bound complexes (Kane, 2006; Tomashek et al., 1997).

Our analysis of the one-dimensional blue native gels indicates a possible alteration in the holoenzyme or assembly intermediates in PAM-1/H3A cells compared to PAM-1 cells (Fig. 5D). V1A subunits were more membrane associated in both WT and PAM-1 cells than in PAM-1/H3A cells (Fig. 7A&B) suggesting that lack of interaction with PAM-1 alters V-ATPase assembly or function. Increased accumulation of V1 intermediates in PAM-1/H3A cells may suggest luminal acidification status as an additional level of regulation for the assembly of intact, functional V-ATPase complexes.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1 Validation of V1A antibody Non-transfected AtT-20 cells (WT) or cells transiently transfected with vectors expressing epitope tagged V1A (HA-V1A, kind gift from Dr. Dewi Astuti (Gharanei et al., 2013) and GFP-V1A from Dr. Martin Kahms (Bodzeta et al., 2017)) were harvested into SDS-lysis buffer. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed against indicated antibodies (V1A:#17115–1-AP, ProteinTech Group; HA: #GTX628489, GeneTex; GFP: JL-8 #632381, Takara Bio). V1A panels show specific staining of endogenous V1A and epitope tagged V1A.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by NIH grants DK-032949 (BAE) and DA-018343 (Yale University School of Medicine MS and Proteomics Resource), NIH SIG Program grant 1S10ODOD018034 (supporting purchase of the Q-Exactive Plus in the MS and Proteomics Resource), the Janice and Rodney Reynolds Endowment and the Scoville Endowment. We thank Taylor Larese for many contributions to the experiments and members of the Neuropeptide Lab for vigorous discussions and productive suggestions. We thank TuKiet Lam, Kathrin Wilczak and Jean Kanyo from the Yale MS & Proteomics Resource for MS sample preparation, data collection, and analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with the contents of this article.

References

- Back N, Rajagopal C, Mains RE, Eipper BA. 2010. Secretory granule membrane protein recycles through multivesicular bodies. Traffic 11(7):972–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman AT, Broers BA, Kline CD, Blackburn NJ. 2011. A copper-methionine interaction controls the pH-dependent activation of peptidylglycine monooxygenase. Biochemistry 50(50):10819–10828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benlekbir S, Bueler SA, Rubinstein JL. 2012. Structure of the vacuolar-type ATPase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae at 11-A resolution. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19(12):1356–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodzeta A, Kahms M, Klingauf J. 2017. The Presynaptic v-ATPase Reversibly Disassembles and Thereby Modulates Exocytosis but Is Not Part of the Fusion Machinery. Cell Rep 20(6):1348–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnemaison ML, Back N, Duffy ME, Ralle M, Mains RE, Eipper BA. 2015a. Adaptor Protein-1 Complex Affects the Endocytic Trafficking and Function of Peptidylglycine alpha-Amidating Monooxygenase, a Luminal Cuproenzyme. J Biol Chem 290(35):21264–21279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnemaison ML, Back N, Duffy ME, Ralle M, Mains RE, Eipper BA. 2015b. Adaptor Protein-1 Complex Affects the Endocytic Trafficking and Function of Peptidylglycine alpha-Amidating Monooxygenase, a Luminal Cuproenzyme. J Biol Chem 290(35):21264–21279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braas KM, Stoffers DA, Eipper BA, May V. 1989. Tissue specific expression of rat peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase activity and mRNA. Mol Endocrinol 3(9):1387–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D, Paunescu TG, Breton S, Marshansky V. 2009. Regulation of the V-ATPase in kidney epithelial cells: dual role in acid-base homeostasis and vesicle trafficking. J Exp Biol 212(Pt 11):1762–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey JR, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. 2010. Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11(1):50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Johnson RC, Milgram SL. 1998. P-CIP1, a novel protein that interacts with the cytosolic domain of peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase, is associated with endosomes. J Biol Chem 273(50):33524–33532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter K, Stransky L, McGuire C, Forgac M. 2015. Recent Insights into the Structure, Regulation, and Function of the V-ATPases. Trends Biochem Sci 40(10):611–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eipper-Mains JE, Kiraly DD, Duff MO, Horowitz MJ, McManus CJ, Eipper BA, Graveley BR, Mains RE. 2013. Effects of Cocaine and Withdrawal on the Mouse Nucleus Accumbens Transcriptome. Genes Brain Behav 12:21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eipper BA, May V, Braas KM. 1988. Membrane-associated peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase in the heart. J Biol Chem 263(17):8371–8379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgac M 2007. Vacuolar ATPases: rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8(11):917–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francone VP, Ifrim MF, Rajagopal C, Leddy CJ, Wang Y, Carson JH, Mains RE, Eipper BA. 2010. Signaling from the secretory granule to the nucleus: Uhmk1 and PAM. Mol Endocrinol 24(8):1543–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharanei S, Zatyka M, Astuti D, Fenton J, Sik A, Nagy Z, Barrett TG. 2013. Vacuolar-type H+-ATPase V1A subunit is a molecular partner of Wolfram syndrome 1 (WFS1) protein, which regulates its expression and stability. Hum Mol Genet 22(2):203–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado-Lorenzo A, Skinner M, El Annan J, Futai M, Sun-Wada GH, Bourgoin S, Casanova J, Wildeman A, Bechoua S, Ausiello DA, Brown D, Marshansky V. 2006. V-ATPase interacts with ARNO and Arf6 in early endosomes and regulates the protein degradative pathway. Nat Cell Biol 8(2):124–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichihara A, Kinouchi K. 2011. Current knowledge of (pro)renin receptor as an accessory protein of vacuolar H+-ATPase. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 12(4):638–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen EJ, Holthuis JC, McGrouther C, Burbach JP, Martens GJ. 1998. Intracellular trafficking of the vacuolar H+-ATPase accessory subunit Ac45. J Cell Sci 111 ( Pt 20):2999–3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen EJ, Scheenen WJ, Hafmans TG, Martens GJ. 2008. Accessory subunit Ac45 controls the V-ATPase in the regulated secretory pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta 1783(12):2301–2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen EJ, van Bakel NH, Coenen AJ, van Dooren SH, van Lith HA, Martens GJ. 2010. An isoform of the vacuolar (H(+))-ATPase accessory subunit Ac45. Cell Mol Life Sci 67(4):629–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane PM. 2006. The where, when, and how of organelle acidification by the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70(1):177–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane PM. 2012. Targeting reversible disassembly as a mechanism of controlling V-ATPase activity. Curr Protein Pept Sci 13(2):117–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki-Nishi S, Nishi T, Forgac M. 2003. Proton translocation driven by ATP hydrolysis in V-ATPases. FEBS Lett 545(1):76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissing S, Hermsen C, Repnik U, Nesset CK, von Bargen K, Griffiths G, Ichihara A, Lee BS, Schwake M, De Brabander J, Haas A, Saftig P. 2015. Vacuolar ATPase in phagosome-lysosome fusion. J Biol Chem 290(22):14166–14180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline CD, Gambill BF, Mayfield M, Lutsenko S, Blackburn NJ. 2016. pH-regulated metal-ligand switching in the HM loop of ATP7A: a new paradigm for metal transfer chemistry. Metallomics 8(8):729–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafourcade C, Sobo K, Kieffer-Jaquinod S, Garin J, van der Goot FG. 2008. Regulation of the V-ATPase along the endocytic pathway occurs through reversible subunit association and membrane localization. PLoS One 3(7):e2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Yu H, Liu SH, Brodsky FM, Peterlin BM. 1998. Interactions between HIV1 Nef and vacuolar ATPase facilitate the internalization of CD4. Immunity 8(5):647–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mains RE, Alam MR, Johnson RC, Darlington DN, Back N, Hand TA, Eipper BA. 1999. Kalirin, a multifunctional PAM COOH-terminal domain interactor protein, affects cytoskeletal organization and ACTH secretion from AtT-20 cells. J Biol Chem 274(5):2929–2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshansky V 2007. The V-ATPase a2-subunit as a putative endosomal pH-sensor. Biochem Soc Trans 35(Pt 5):1092–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshansky V, Rubinstein JL, Gruber G. 2014. Eukaryotic V-ATPase: novel structural findings and functional insights. Biochim Biophys Acta 1837(6):857–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles AL, Burr SP, Grice GL, Nathan JA. 2017. The vacuolar-ATPase complex and assembly factors, TMEM199 and CCDC115, control HIF1alpha prolyl hydroxylation by regulating cellular iron levels. Elife 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgram SL, Johnson RC, Mains RE. 1992. Expression of individual forms of peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase in AtT-20 cells: endoproteolytic processing and routing to secretory granules. J Cell Biol 117(4):717–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgram SL, Kho ST, Martin GV, Mains RE, Eipper BA. 1997. Localization of integral membrane peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase in neuroendocrine cells. J Cell Sci 110 ( Pt 6):695–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgram SL, Mains RE, Eipper BA. 1993. COOH-terminal signals mediate the trafficking of a peptide processing enzyme in endocrine cells. J Cell Biol 121(1):23–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muth E, Driscoll WJ, Smalstig A, Goping G, Mueller GP. 2004. Proteomic analysis of rat atrial secretory granules: a platform for testable hypotheses. Biochim Biophys Acta 1699(1–2):263–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen G, Muller DN. 2010. The biology of the (pro)renin receptor. J Am Soc Nephrol 21(1):18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otoikhian A, Barry AN, Mayfield M, Nilges M, Huang Y, Lutsenko S, Blackburn NJ. 2012. Lumenal loop M672-P707 of the Menkes protein (ATP7A) transfers copper to peptidylglycine monooxygenase. J Am Chem Soc 134(25):10458–10468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyarce AM, Eipper BA. 1995. Identification of subcellular compartments containing peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase in rat anterior pituitary. J Cell Sci 108 ( Pt 1):287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paroutis P, Touret N, Grinstein S. 2004. The pH of the secretory pathway: measurement, determinants, and regulation. Physiology (Bethesda) 19:207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal C, Stone KL, Francone VP, Mains RE, Eipper BA. 2009. Secretory granule to the nucleus: role of a multiply phosphorylated intrinsically unstructured domain. J Biol Chem 284(38):25723–25734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel E, Mains RE, Farquhar MG. 1989. Proteolytic processing of pro-ACTH/endorphin begins in the Golgi complex of pituitary corticotropes and AtT-20 cells. Mol Endocrinol 3(8):1223–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobota JA, Back N, Eipper BA, Mains RE. 2009. Inhibitors of the V0 subunit of the vacuolar H+-ATPase prevent segregation of lysosomal- and secretory-pathway proteins. J Cell Sci 122(Pt 19):3542–3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steveson TC, Keutmann HT, Mains RE, Eipper BA. 1999. Phosphorylation of cytosolic domain Ser(937) affects both biosynthetic and endocytic trafficking of peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase. J Biol Chem 274(30):21128–21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stransky LA, Forgac M. 2015. Amino Acid Availability Modulates Vacuolar H+-ATPase Assembly. J Biol Chem 290(45):27360–27369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomashek JJ, Garrison BS, Klionsky DJ. 1997. Reconstitution in vitro of the V1 complex from the yeast vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase. Assembly recapitulates mechanism. J Biol Chem 272(26):16618–16623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccari T, Duchi S, Cortese K, Tacchetti C, Bilder D. 2010. The vacuolar ATPase is required for physiological as well as pathological activation of the Notch receptor. Development 137(11):1825–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishwanatha K, Back N, Mains RE, Eipper BA. 2014. A histidine-rich linker region in peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase has the properties of a pH sensor. J Biol Chem 289(18):12404–12420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishwanatha KS, Back N, Lam TT, Mains RE, Eipper BA. 2016. O-Glycosylation of a Secretory Granule Membrane Enzyme Is Essential for Its Endocytic Trafficking. J Biol Chem. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun HY, Milgram SL, Keutmann HT, Eipper BA. 1995. Phosphorylation of the cytosolic domain of peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase. J Biol Chem 270(50):30075–30083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Validation of V1A antibody Non-transfected AtT-20 cells (WT) or cells transiently transfected with vectors expressing epitope tagged V1A (HA-V1A, kind gift from Dr. Dewi Astuti (Gharanei et al., 2013) and GFP-V1A from Dr. Martin Kahms (Bodzeta et al., 2017)) were harvested into SDS-lysis buffer. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed against indicated antibodies (V1A:#17115–1-AP, ProteinTech Group; HA: #GTX628489, GeneTex; GFP: JL-8 #632381, Takara Bio). V1A panels show specific staining of endogenous V1A and epitope tagged V1A.