Abstract

Introduction

The development and implementation of policy, systems and environmental (PSE) change is a commonly used public health approach to reduce disease burden. CDC’s National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program conducted a demonstration with 13 programs to determine whether and to what extent dedicated resources would enhance the adoption of PSE strategies. This paper describes results of the qualitative portion of a longitudinal, mixed-methods evaluation of this demonstration.

Methods

We conducted case studies with a diverse subset of the 13 programs, completing 106 in-depth interviews with state/tribal program staff, community partners, and decision-makers. Interviews addressed PSE change planning and capacity building, partnerships, local context, and how programs achieved PSE change.

Results

Dedicated PSE resources, including a policy analyst, helped increase PSE change capacity, intensify focus on PSE change overall, and accomplish specific PSE changes within individual jurisdictions. Stakeholders described PSE change as a gradual process requiring preparation and prioritization, strategic collaboration, and navigation of local context.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that the demonstration program, including PSE-dedicated funds and a policy analyst, was successful in both increasing PSE change capacity and achieving PSE change itself. These results may be useful to other state, tribal, territorial and public health organizations planning or implementing PSE change strategies.

Keywords: case study evaluation, systems change, public health, cancer prevention and control

Background

Since 1998, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has funded the National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program (NCCCP) in 50 states, the District of Columbia, 7 tribes and tribal organizations, and 7 U.S. territories and Pacific Island Jurisdictions to control cancer in their populations.1 Over the years, many NCCCP grantees have incorporated policy, systems and environmental (PSE) change strategies into their cancer prevention efforts to effect sustainable change.2,3 Typical PSE change strategies used by grantees include educating about existing policies in local settings, such as hospitals and workplaces, and creating systems and environmental changes within those settings that increase adherence to those policies. The recent public health focus on activities with the potential for high impact relative to resource expenditure has brought PSE change capacity and strategies into the forefront.4,5

In 2010, CDC initiated a 5-year demonstration program to increase the capacity of NCCCP grantees to focus on PSE change strategies in cancer prevention and to align with and inform PSE priorities introduced within the larger NCCCP that same year.1,6 Thirteen grantees were funded through the demonstration program: Cherokee Nation, Colorado, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, Utah, and Wisconsin. Expected outcomes of this demonstration were the development of PSE initiatives to address local priorities, increased collaboration with traditional and non-traditional partners, and the development of model PSE change processes and procedures that could inform all NCCCP grantees.

To ascertain the extent to which the demonstration’s dedicated resources achieved these outcomes, we conducted a comprehensive, mixed methods evaluation. The qualitative component of the evaluation was designed to facilitate a deeper understanding of programmatic contexts and their influence on grantees’ approaches. The objective of this paper is to highlight these qualitative findings to inform other state, tribal, territorial and public health organizations planning or implementing PSE change strategies in their jurisdictions. These findings can be applied to both the NCCCP and other similar public health programs using PSE strategies to reduce disease burden.

Methods

We conducted a longitudinal, multiple case study comprised of semi-structured, in-depth interviews with stakeholders from six of the 13 NCCCP grantees participating in this demonstration project. The subset of grantees for the evaluation consisted of Cherokee Nation, Florida, Louisiana, Michigan, Oregon, and Utah and was selected based on criteria that would ensure a diversity of experiences, program contexts, and local policy capacity (Table 1). We worked with the NCCCP program director from each selected program to identify a diverse range of stakeholders for the key informant interviews.

Table 1.

Case Selection Criteria

| Domain | Criterion | Description | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structurea | Centralization | Public health system centralization - are local HDs autonomous or centralized under state HD? The model of state and local public health relationships as a reflection of the overall structure of the public health system in a jurisdiction. | Centralized organizational control, Decentralized organizational control, Hybrid |

| Policy Climateb | State Partisan Composition | State partisan control | Democrat, Republican, Split |

| Number of childhood obesity-related bills enacted, by state, 2008–2011 (% of Bills Introduced) | Number of childhood obesity-related bills enacted, by state, 2008–2011; includes nutrition, physical activity, and obesity. | Count (% of all related bills introduced) | |

| ‘07–’08 School Nutrition Policies | Whether policies have been enacted or proposed regarding public school nutrition. | Enacted, proposed, none | |

| ‘07–’08 School PA/PE Policies | Whether policies have been enacted or proposed regarding public school physical activity/physical education. | ||

| 2012 Smoke-free public school Campus Policies | Whether policies have been enacted for smoke free public school campuses. | Yes, No | |

| Capacity | CTGc FUNDED | Whether CTG funding was received by an agency or organization in the CCCP jurisdiction. | Yes, No |

| CTG SCOPE | If CTG FUNDED=Yes, then the jurisdictional/geographic scope of the funding. | County, State, Tribe | |

| CPPWd FUNDED | Whether CPPW funding was received by an agency or organization in the CCCP jurisdiction. | Yes, No | |

| CPPW SCOPE | If CPPW FUNDED=Yes, then the jurisdictional/geographic scope of the funding. | City, Metro, County, State, Tribe | |

| Focus Arease | Systems Change Efforts | General PSE Approaches | “Yes” if it is an area of focus for grantee (as of Sept 2012) |

| Tobacco Control | Primary prevention | ||

| Nutrition | |||

| Physical Activity | |||

| Vaccination | |||

| Sun Safety | |||

| Built Environment | |||

| Radon | |||

| Breast Cancer Screening | Secondary prevention | ||

| Colorectal Cancer Screening | |||

| Patient Navigation | |||

| Worksite Wellness | |||

| Survivorship | Tertiary prevention | ||

| Demographicsf | % Non-Metropolitan | % Rural (% non-Metropolitan) | 0–100% |

| % in Poverty | % under 100% Federal Poverty Level | 0–100% | |

| Health Ranking of the Populationg | America’s Health Rankings | Ranking of each state (but not Cherokee Nation or other tribes/territories) based on the America’s Health Rankings composite health score. | 1–50 |

| Adults 50+ w/preventive screenings & services | The annual percentage of adults age 50 and older who receive recommended screenings and preventive services as an overall indicator. | 0–100% |

Data Source: Page 27 of the 2011 ASTHO report http://www.astho.org/Display/AssetDisplay.aspx?id=2882,

Data Sources: State political party in power: http://www.ncsl.org/documents/statevote/2010_Legis_and_State_post.pdf; CDC Chronic Disease Policy Database: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/CDPHPPolicySearch/Default.aspx; RWJ, 2009 report on NPAO policies by state http://www.rwjf.org/files/research/20090330ncsllegislationreport2009.pdf; OSH, http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/statesystem -interactive data base on specific tobacco policies by state.

The Community Transformation Grant (CTG) program, funded from 2011–2014, helped communities design and carry out local programs to prevent chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. Grantees partnered with various sectors of the community to plan and implement programs, using PSE approaches. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dch/programs/communitytransformation/index.htm

The Communities Putting Prevention to Work (CPPW) program, funded from 2010–2012, supported 50 communities working to reduce obesity and tobacco use. Strategies in this program were directed at the population-level and used PSE approaches. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dch/programs/communitiesputtingpreventiontowork/index.htm

Data Source: Policy, Systems, and Environmental Education Forum meeting materials, Sept 19–20, 2012, American Cancer Society,

Data Sources: America’s Health Rankings: A call to action for individuals and their communities. 2011 Edition. United Health Foundation, Minnetonka, MN. (Table 1, p. 16); County Rankings: http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/#app

Key informants included NCCCP program directors and staff, the policy analyst (who was supported by the demonstration funds), community stakeholders, and decision-makers. Partners involved in the state or tribal cancer coalition’s policy-related initiatives were also included. A cancer coalition, vital to the work of the NCCCP, is a state, tribal or territorial-specific group, made up of diverse cancer practitioners and charged with both writing the grantee’s cancer plan and assisting with implementation of initiatives to achieve cancer burden reduction according to the plan. In total, we conducted 106 interviews with 68 unique individuals over the course of the evaluation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of Unique Participants and Interviews Conducted

| Jurisdiction | Total Unique Participants | Number of Wave 1 Interviews | Number of Wave 2 Interviews | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cherokee Nation | 12 | 11 | 9 | 20 |

| Florida | 11 | 10 | 8 | 18 |

| Louisiana | 9 | 8 | 7 | 15 |

| Michigan | 12 | 11 | 8 | 19 |

| Oregon | 10 | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| Utah | 14 | 12 | 8 | 20 |

| TOTAL | 68 | 60 | 46 | 106 |

We conducted interviews at two points in time: during July and August of 2014 (third year of the demonstration funding) and July and August of 2015 (fourth and final year of funding). In 2014, we conducted in-person interviews; in 2015 we conducted telephone interviews. For the second wave of interviews, we scheduled interviews with the same group of participants as 2014, to the extent possible. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Interview questions were tailored to the role of each key informant and addressed the following topics: preparation and prioritization, collaboration and partnerships, implementation, technical assistance and training, evaluation efforts, and outcomes. The semi-structured nature of the interviews made it possible for interviewers to probe for more information on an especially important topics while also learning about and discussing activities unanticipated by the evaluators.

Data Security and Confidentiality

All interview data were treated as confidential; electronic interview data were stored on a password-protected shared space on a secure computer network. Digital audio recordings of the interviews were destroyed after transcripts were produced; identifying data were maintained by case study coordinators but not shared with CDC.

Human Participant Protection

Prior to each interview, the participant was asked to review and acknowledge an informed consent document, which included permission to audio record. The evaluation protocol was reviewed and approved by Battelle’s institutional review board (IRB). This information collected in this study was approved by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), approval number 0920-1016.

Data Analysis

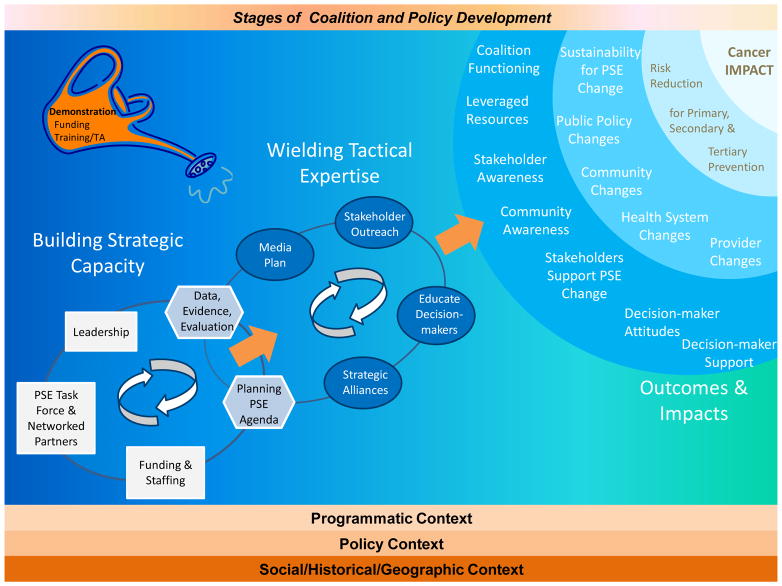

We used NVivo® (version 9.2, Victoria, Australia) to manage the qualitative data. To address the questions driving the overall evaluation, we used a combination of conventional and directed content analysis approaches7 and constant comparative methods 8–11 to analyze data. First, we coded according to the interview questions, the evaluation questions and topics, and the theoretical concepts represented in the conceptual model (Figure 1), developed out of an environmental scan conducted earlier in the study. This model highlights the importance of acknowledging that PSE change occurs within complex systems and of understanding contexts within which program implementation takes place.12 The constant comparative approach allowed us to detect patterns in the case study data, making multiple comparisons within and across cases during analysis.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model for the Demonstrating the Capacity of Comprehensive Cancer Control Programs to Implement Policy, Systems, and Environmental Change Cancer Control Interventions.

TA: Technical Assistance

PSE: Policy, Systems, and Environmental Change

Our systematic analytic process began with conducting team debriefings immediately after each visit to a state or tribe. Debriefing notes formed the basis of a preliminary codebook that we used as the starting point for the data analysis. The code development process continued as we conducted thorough reviews of each interview transcript. Since analyzing qualitative data is an iterative process, new themes were added to the preliminary codebook as they emerged during the data review and analysis process. All interviews were then coded using the final codebook. We then derived themes from commonalities across the experiences and perspectives of the various participants in each program and subsequently compared themes across programs to perform the cross case analysis.

Throughout the case study, we took steps to enhance trustworthiness, or rigor, in the qualitative process. Prior to beginning each round of site visits, case study teams participated in protocol trainings to ensure consistency in interviewing and data analysis across site visit teams. To enhance coding consistency, two team members independently coded the same interview transcripts (2–3), jointly reviewed the coding, reconciled differences by consensus, and clarified code definitions and ambiguities prior to analysis of the complete site visit data set. This rigorous process helped ensure high agreement among coders, who subsequently coded the complete set of interviews independently. We maintained an audit trail throughout these processes.

Results

Participation in the demonstration project enabled grantees to add the support of a policy analyst and make PSE change initiatives a priority. Overall outcomes that respondents identified were improved PSE change capacity and the achievement of PSE change itself. As respondents described the complex processes involved in working to achieve these outcomes, several overlapping themes emerged as being particularly important: preparation and prioritization, strategic collaboration, and navigation of local context.

Outcomes

Improved PSE Change Capacity

Participants across all jurisdictions indicated that the demonstration funding helped increase their overall capacity to undertake PSE change work, often through the addition of dedicated policy analyst staff to support this work. The policy analysts, who often brought knowledge of the policy process, could commit time to PSE change work, including coordinating PSE change efforts with partners. As one respondent explained, “[PSE] work takes people-power, and there is never enough people-power to pull this kind of stuff off, and so that’s been helpful in just adding some boots on the ground.” In one program, the momentum for PSE change initiatives led to the formation of an internal policy workgroup to apply a PSE change lens to chronic disease work beyond solely that of the cancer control programs.

Another way in which the demonstration helped increase programs’ PSE change capacity was through trainings and technical assistance (TA). Respondents explained that not only did they receive PSE change training and TA from CDC and other sources, but also they had the opportunity to provide PSE change TA to their partners and stakeholders. Many respondents stated that once partners and stakeholders demonstrated increased understanding and support of PSE change, some cancer coalitions shifted their work toward PSE change initiatives. One participant explained, “Rather than planning health fairs to address an issue, [partners] now consider the environment and existing laws when developing initiatives.” In one jurisdiction, respondents stated that their program was heavily engaged in PSE change work prior to the demonstration. In this case, respondents said that participation in this project did not necessarily increase their knowledge and skills to do this work, but it enabled them to increase the number of staff members who could devote time to PSE change work.

Achievement of PSE Change

Respondents described various PSE change achievements, particularly in tobacco control for cancer burden reduction. Many programs and partners were already addressing tobacco control in cancer prior to the demonstration, and their participation in the demonstration helped sustain these efforts. In one jurisdiction, respondents indicated that a governor asked the coalition for information about the efficacy of smoke-free policies on cigarette use. Subsequently, the governor issued a tobacco-free executive order that banned tobacco use on state property. Respondents from another jurisdiction explained that tobacco control efforts of local coalitions and partners led to the passing of a smoke-free ordinance in a major city and increased the state tobacco tax, the first such increase in approximately 15 years. Jurisdictions also made large-scale environmental change in other arenas. One jurisdiction created a bicycle and pedestrian master plan, which not only generated a lot of interest from communities across the state, but also demonstrated how a small amount of government funding could be leveraged to obtain additional partner funding and support for the program. Another jurisdiction described their community health worker (CHW) initiative as a major PSE change success. This initiative included transitioning the state CHW coalition into a nonprofit organization and supporting the organization’s work to establish a statewide CHW certification process.

Processes

Preparation and Prioritization

Demonstration grantees were required to develop specific agendas to guide their PSE change work, and they described how they identified PSE change priorities. They articulated the importance of selecting issues that were most significant in their communities, which were driven by data and community input. Several jurisdictions identified new or emerging issues, while others focused on issues that were already being addressed in their communities. Respondents in one jurisdiction described their long history of PSE change work and explained how participation in the demonstration helped advance these efforts. One such respondent said, “We had everything all lined up… [During the demonstration period] we had a lot of leadership interest, and the timing was right.”

Strategic Collaboration

Program staff consistently talked about the importance of collaborating with the right partners when working on PSE change issues. All six grantees evaluated had long histories of working collaboratively with a variety of partners and stakeholders in their communities that preceded the demonstration program. Partnerships included particular community partners and stakeholders who were valuable for addressing specific PSE change goals. Programs not only relied on established partnerships to form a consistent base of support throughout the demonstration project, but also established new relationships with non-traditional partners in order to build support for particular PSE change initiatives.

Partners played a variety of roles depending on their strengths and resources, such as helping implement strategies, educating stakeholders and decision-makers, conducting outreach to various communities and audiences, and providing necessary support services. In one jurisdiction, program staff described how partners provided crucial support with running their cancer control coalition. Program staff from another jurisdiction described how partner support helped with local implementation of bicycle-pedestrian development across the state. One staff member summarized, “I don’t understand how people do this job without partners.”

Program staff also spoke broadly about the importance of working with partners who served as champions in PSE change efforts. In some cases, these partners were organizations, such as the American Cancer Society or a local cancer center, while in other cases, it was a particular community advocate, policy maker, or coalition member who helped propel an issue forward. In one example, respondents discussed the story of a young skin cancer survivor who was able to successfully mobilize support for policies to prevent skin cancer across the state. The survivor, who was diagnosed with malignant melanoma at age 24, testified in front of a legislative committee to elevate the issue of skin cancer as part of an outreach team called “Ten Young Women against Skin Cancer.” This team is comprised of women who were diagnosed with skin cancer at young ages and who now advocate for sun safety policies and practices. The demonstration grantee discussed how this champion’s efforts to raise the issue of sun safety helped support the grantee’s wider efforts to educate the public about sun safety across the state. This, in turn, helped create a more supportive environment for local municipalities to incorporate shade policies into plans for new public projects, such as parks and recreation centers.

When asked how partnerships were sustained over time, program respondents described strategies for active engagement, including scheduling regular meetings, maintaining communication via a point person (such as the policy analyst), sending out newsletters, providing trainings to partners, and having a solid strategic plan with meaningful agenda items assigned to partners. While in most cases partnerships were informally structured, partners in one jurisdiction decided to formalize their cancer coalition partnership to enhance sustainability. This resulted in a transition from an informal, volunteer-based coalition to a formalized 501(c) (3) organization that could apply for grant funding and continue to operate beyond the demonstration to address cancer-related PSE change activities.

Respondents indicated that while collaboration was necessary to undertake PSE change work, keeping coalition members engaged and managing conflicts among partners was sometimes challenging. In some cases, it was difficult to keep members motivated when working on issues that were not aligned with their specific interests or preferred strategies. In one jurisdiction, a respondent described a situation where there was fundamental disagreement among partners about an approach for tobacco control. This caused substantial conflict among partners and ultimately led to the severing of ties.

Navigation of Local Context

Respondents could not overstate the importance of navigating the local context throughout the PSE change life cycle. They explained that solid data was not enough to identify and prioritize a program’s PSE agenda; local context, particularly public support and the political environment, had a major influence in determining feasibility of particular PSE change strategies. For example, strong community support and activism about radon within one jurisdiction helped propel this item forward in the PSE change process. In another jurisdiction, respondents described how a state legislator with an interest in skin cancer and sun safety approached the health department with a request for information and educational resources to support a proposed tanning regulation. In this example, “The bill sponsor approached DOH [Department of Health] and said, ‘I’m looking at doing tanning legislation and would love some information from you guys.’” Respondents said they were happy to provide the educational resources she requested.

While support from the community or political environment could help propel PSE change efforts, a lack of support could serve as a barrier. Respondents from a jurisdiction self-identified as generally unsupportive of public health priorities described the difficulties in getting tobacco control initiatives implemented. In other jurisdictions, respondents described issues that were perceived as infringing on personal liberties as being controversial. For example, one jurisdiction sought to institute nutritional standards across state agencies that would regulate sugary drinks and increase access to healthier options, including water. Respondents explained that although from a nutritional standpoint the policy made sense, state employees were not ready to support a policy that they perceived as limiting individual choice such as access to sugary drinks. One respondent stated, “I’m not convinced that we have the right opportunity and the right culture yet to be able to [institute nutritional standards] on a large-scale.”

Achieving PSE change often requires flexibility to adapt to changing conditions and emerging opportunities. Respondents in several jurisdictions detailed the importance of being nimble and ready to act when a “window of opportunity” presented itself. For example, respondents in one jurisdiction described that their demonstration work poised them to act quickly when an opportunity arose to vie for additional funding, explaining that their quick efforts helped them successfully obtain tobacco prevention funding from a source that was previously unavailable to them.

Discussion

Overall, our case study findings underscore that dedicated resources help increase capacity for undertaking PSE initiatives and for achieving PSE change. Our findings highlight the complexity of accomplishing PSE change and describe necessary processes as preparation and prioritization, strategic collaboration, and navigation of local contexts.

In addition to providing their PSE change expertise and experience, the policy analysts who participated in this demonstration project, played an important role in maintaining consistent focus, coordination, and communication among the various stakeholders and across the different PSE change initiatives, suggesting that programs of various maturity levels could benefit from a dedicated policy analyst. Even in jurisdictions where program staff and partners were experienced with PSE change, the policy analyst added value in providing a dedicated focus to PSE change initiatives. TA/training further contributed by enhancing PSE change knowledge and skills among program staff and partners involved in the planning and implementation of the initiatives. This combination of expert advisors/coordinators and TA/training has been a key factor in the success of other national initiatives promoting a PSE change orientation in public health 13–15.

Our results also suggest that contextual factors are important for implementing and achieving PSE change. General economic conditions, political climate, and community/decision-maker support for PSE changes were identified as factors that could both facilitate and hinder success. While collaborating with partners is essential, without the support of the community, PSE change is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve. Other facilitating contextual factors included a long history of collaboration among cancer control stakeholders, including well-established coalitions, which served as the basis for forming partnerships specifically focused on PSE change. The importance of acknowledging context and systems within which PSE change initiatives can be implemented has been found to be important not only across public health practice 13,15–19, but also across other disciplinary fields, such as sociology, behavioral science, and transportation 12,20.

It is important to highlight the significance of these PSE successes on reducing the cancer burden. For instance, the PSE change that resulted in statewide CHW certification will help to increase access to cancer screening and treatment 21–23. Developing a universal curriculum based on CHW competencies 24 and working with patient navigators (PNs) with decades of cancer-related experience 25,26 will enable this program to establish regular avenues for dialogue between CHWs and PNs to help each understand the other’s role and how to work together to increase access to care and improve health outcomes, serving as a model for collaboration among CHWs and PNs across health care and public health.

Since PSE change at the population level has the potential to have high impact relative to public health resource expenditure 4, these findings provide a PSE capacity framework that aligns with strategies necessary for successful public health programs 27. This framework may be useful for not only the NCCCP overall but also other state, tribal, territorial and public health organizations working to prevent other chronic diseases through PSE change. Findings also emphasize the NCCCP’s increased focus on PSE strategies to reduce risk factors for cancer prevention 28 and support public health efforts shift to environmental approaches that focus on reducing risk factors for multiple chronic diseases and improve population health 29.

Limitations and Strengths

This multiple case study has several limitations. First, due to time and resource constraints, the number of study participants was limited to approximately 10 key informants per grantee, which may have reduced the range of perspectives available for analysis. In addition, key informants were identified based on grantee recommendations, which may have introduced selection bias. Second, due to administrative challenges that delayed the initial wave of data collection, we were not able to engage with stakeholders during the earlier phases of the program funding period. Thus, questions about those earlier program phases may have been subject to recall bias and the longitudinal nature of the case study was diminished.

Despite these limitations, this multiple case study has strengths. First, we were able to engage with key informants at two time points in order to observe programmatic changes over time. Second, the qualitative methods used allowed us to solicit rich descriptions of the implementation processes, contextual conditions, and outcomes achieved. Third, collecting data from multiple key informants representing various types of stakeholders allowed us to build trustworthy depictions of the grantees’ overall experiences from multiple perspectives.

Implications for Policy and Practice.

PSE change at the population level has the potential to have high impact relative to expenditure.

Dedicated staff with PSE-related experience can greatly enhance programmatic PSE change capacity, regardless of program maturity.

PSE-focused training and Technical Assistance are important components of a comprehensive effort to increase programmatic PSE change capacity.

PSE change work has many components: preparation and prioritization, strategic collaboration, and navigation of local contexts.

Cancer prevention and control programs and coalitions are vital partners in addressing broader public health issues, particularly, reducing risk factors to multiple chronic diseases,

This PSE change framework may be useful for other state, tribal, territorial and public health organizations working to prevent other chronic diseases and improve population health.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge CDC colleagues Annette Gardner and Anne Major for their valuable contributions to the case study evaluation. We would also like to thank our case study participants for sharing their experiences and insights with us.

Financial Support: All funding was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed 2/1/2017];National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/ncccp/index.htm.

- 2.Nitta M, Navasca D, Tareg A, Palafox NA. Cancer risk reduction in the US Affiliated Pacific Islands: Utilizing a novel policy, systems, and environmental (PSE) approach. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;50(Pt B):278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prevention CfDCa. National Cancer Control Program: Success Stories. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/ncccp/state.htm.

- 4.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bunnell R, O’Neil D, Soler R, et al. Fifty Communities Putting Prevention to Work: Accelerating Chronic Disease Prevention Through Policy, Systems and Environmental Change. Journal of Community Health. 2012;37(5):1081–1090. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9542-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belle Isle L, Plescia M, La Porta M, Shepherd W. In conclusion: looking to the future of comprehensive cancer control. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(12):2049–2057. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9666-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin RK. Case Study Research: Designs and Methods. 5. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stake RE. Multiple Case Study Analysis. NY, New York: The Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boeije H. A Purposeful Approach to the Constant Comparative Method in the Analysis of Qualitative Interviews. Quality and Quantity. 2002;36(4):391–409. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panter J, Guell C, Prins R, Ogilvie D. Physical activity and the environment: conceptual review and framework for intervention research. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):156. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0610-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheadle A, Cromp D, Krieger JW, et al. Promoting Policy, Systems, and Environment Change to Prevent Chronic Disease: Lessons Learned From the King County Communities Putting Prevention to Work Initiative. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(4):348–359. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hefelfinger J, Patty A, Ussery A, Young W. Technical assistance from state health departments for communities engaged in policy, systems, and environmental change: the ACHIEVE Program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E175. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kane H, Hinnant L, Day K, et al. Pathways to Program Success: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) of Communities Putting Prevention to Work Case Study Programs. Journal of public health management and practice: JPHMP. 2017;23(2):104–111. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kegler MC, Honeycutt S, Davis M, et al. Policy, systems, and environmental change in the Mississippi Delta: considerations for evaluation design. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(1 Suppl):57S–66S. doi: 10.1177/1090198114568428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honeycutt S, Leeman J, McCarthy WJ, et al. Evaluating Policy, Systems, and Environmental Change Interventions: Lessons Learned From CDC’s Prevention Research Centers. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E174. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.150281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parekh AK, Scott AR, McMahon C, Teel C. Role of public-private partnerships in tackling the tobacco and obesity epidemics. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E99. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritz PJ, Irwin K, Bouza L. Using a Community Workshop Model to Initiate Policy, Systems, and Environmental Change That Support Active Living in Indiana, 2014–2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E74. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geller K, Lippke S, Nigg CR. Future directions of multiple behavior change research. J Behav Med. 2017;40(1):194–202. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9809-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenthal EL, Brownstein JN, Rush CH, et al. Community health workers: part of the solution. Health Affairs. 2010;29(7):1338–1342. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blumenthal DS, Sung J, Coates R, Williams J, Liff J. Recruitment and retention of subjects for a longitudinal cancer prevention study in an inner-city black community. Health services research. 1995;30(1 Pt 2):197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. [Accessed 3/1/2017];Improving cancer prevention and control: How state agencies can support patient navigators and community health workers. 2012 http://www.astho.org/ImprovingCancerPreventionandControl/

- 24.Rosenthal EL, Wiggins N, Ingram M, Mayfield-Johnson S, De Zapien JG. Community health workers then and now: an overview of national studies aimed at defining the field. The Journal of ambulatory care management. 2011;34(3):247–259. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31821c64d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rohan EA, Slotman B, DeGroff A, Morrissey KG, Murillo J, Schroy P. Refining the Patient Navigation Role in a Colorectal Cancer Screening Program: Results From an Intervention Study. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(11):1371–1378. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011;117(15 Suppl):3539–3542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frieden TR. Six components necessary for effective public health program implementation. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):17–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grants.gov. CDC-RFA-DP17-1701. Cancer Prevention and Control Programs for State, Territorial, and Tribal Organizations Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control-NCDPHP--Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Accessed 3/17/2017]. https://www.grants.gov/web/grants/search-grants.html. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA, Bowman BA. Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. The Lancet. 384(9937):45–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60648-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]