When children experience early failures in caregiving, they are at increased risk for developing insecure and disorganized attachments (Van IJzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1999). When distressed, insecurely attached children use coherent and organized strategies, including avoidance or resistance, whereas children with disorganized attachments often demonstrate a breakdown in strategy or fearful behaviors in the presence of their caregivers (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Main & Solomon, 1990). Insecure attachments are associated with less optimal outcomes than secure attachments, but disorganized attachments in particular are associated with adverse long-term outcomes (Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Van IJzendoorn, Lapsley, & Roisman, 2010). These adverse outcomes can be observed in middle childhood, when establishing peer relationships is one of the most important developmental tasks (Hartup, 1996). Social information processing (SIP) deficits have been proposed as a key mechanism explaining why children develop problematic peer relations (Crick & Dodge, 1994). However, to our knowledge, attachment disorganization in infancy has not been linked to problematic social information processing patterns in middle childhood. Findings are also mixed as to whether children with insecure attachments in infancy demonstrate more maladaptive social information processing patterns in middle childhood than children with secure attachments. Moreover, the link between attachment quality in infancy and later SIP is rarely assessed when taking into account parental sensitivity. To address these questions, this study examined attachment disorganization and insecurity in infancy and insensitive parenting behaviors at age eight as developmental precursors and correlates, respectively, to social information processing deficits at age eight.

Peer Relations, Early Adversity, and Attachment

Children who experience early adversity, such as maltreatment, are more likely to have problems establishing positive peer relationships than other children. Children who have experienced adversity are more likely to act aggressively (e.g., Salzinger, Feldman, Hammer, & Rosario, 1993; Weiss, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1992), withdraw socially (Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1992; Shields, Cicchetti, & Ryan, 1994), exhibit negative affect (Parker & Herrera, 1996), and are ultimately more likely to experience peer rejection than children who have not experienced adversity (Bolger & Patterson, 2001).

Children who experience early adversity are at risk for developing insecure attachments, which may play a role in later problematic peer relations outcomes. Insecure attachment may diminish children’s ability to establish friendships by hindering the development of relationship skills that make children more attractive to peers and depriving them of the confidence to explore the new environment of peer relationships (Kerns, 1996; Russell, Pettit, & Mize, 1991; Sroufe et al., 2009). A meta-analysis by Schneider, Atkinson, and Tardif (2001) supported this prediction; children with insecure attachments had lower quality friendships, were more socially withdrawn and aggressive, and showed less leadership and sociability with peers in early and middle childhood than children with secure attachments in infancy.

Disorganized attachment may place children at even greater risk for negative peer relations than insecure attachment. Indeed, children with disorganized attachments experience more challenges forming and maintaining peer relationships than children with insecure (but organized) attachments (Hartup, 1996; Jacobvitz & Hazen, 1999; Lyons-Ruth, Alpern, & Repacholi, 1993; Seibert & Kerns, 2015). During the preschool years, children with disorganized attachments tend to act out aggressively or withdraw from social situations (Jacobvitz & Hazen, 1999); Lyons-Ruth, Alpern, and Repacholli (1993) found that the strongest single predictor of hostile behavior among preschoolers was disorganized attachment. In a recent study, Seibert and Kerns (2015) found that attachment disorganization in infancy, and not attachment insecurity, predicted high levels of relational aggression and peer victimization and low levels of prosocial behavior in middle childhood. These findings are consistent with a body of literature suggesting that attachment disorganization is a stronger predictor of externalizing behavior than attachment insecurity (Fearon et al., 2010).

Peer Relations and Social Information Processing

Children with insecure and disorganized attachments are at risk for processing social information differently than children with secure and organized attachments, and this distorted processing may explain why children with insecure and disorganized attachments experience problematic peer relations. Proposed by Dodge and colleagues (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Dodge, Petit, McClaskey, Brown, & Gottman, 1986), the SIP model provides a framework for the series of mental steps that children undergo when they encounter a social situation. The five steps include the encoding of internal and external cues, interpretation of these cues, selection of goals, construction of possible behavioral responses, and evaluation of those responses (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Fontaine & Dodge, 2006). Deficits in each step are associated with maladaptive social behavior, particularly aggression (Dodge et al., 1986), and these deficits are cumulative (Crick & Dodge, 1994).

Hostile cue interpretations.

Hostile attributional bias, a social cognitive pattern in which children over-perceive hostility following ambiguous provocation, is a strong and consistent predictor of aggressive behavior toward peers (Orobio de Castro, Veerman, Koops, Bosch, & Monshouwer, 2002). Prior research has drawn theoretically meaningful connections between attachment and hostile attributional bias (e.g., McElwain, Booth-LaForce, Lansford, Wu, & Dyer, 2008). In brief, early experiences with caregivers influence the extent to which children feel deserving of care and affection and view their caregiver as available, accepting, and responsive (Bowlby, 1969). These beliefs, often referred to as internal working models, may develop into more generalized expectations about the warmth and responsiveness of others, including peers (Collins, 1996). According to attachment theory, when children repeatedly receive rejection and hostility from an attachment figure, they begin to expect it from others outside the caregiving relationship.

Two studies have supported a link between attachment insecurity and hostile attributional bias (Suess, Grossman, & Sroufe, 1992; Ziv, Oppenheim, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2004), whereas other studies did not find a significant association between infant attachment security and hostile attributional bias in the early school years (Cassidy et al., 1996; Raikes & Thompson, 2008). One study found that disorganized attachment in early childhood was concurrently associated with hostile attributional bias (Zaccagnino et al., 2013), but to our knowledge, links between attachment disorganization in infancy and hostile attributional bias in middle childhood have not been reported in the literature.

Aggressive goals.

After children interpret a social situation, they must then identify a goal or a desired outcome. To our knowledge, no longitudinal study has examined infant attachment as a predictor of aggressive goals in the peer context in the SIP model. However, in a study examining the concurrent relations between attachment representations and SIP goals in early adolescence, secure attachment representations were negatively associated with the endorsement of antisocial goals (e.g., the desire to retaliate using physical aggression), and disorganized representations were positively associated with the endorsement of antisocial goals (Granot & Mayseless, 2012).

Aggressive responses.

With their goal in mind, children generate potential behavioral responses. In a longitudinal study, no support was found for a link between infant attachment and aggressive response generation in middle childhood (Ziv, Oppenheim, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2004). One cross-sectional study found that disorganized and insecure-ambivalent attachment representations were concurrently associated with aggressive problem solving in early childhood (Zaccagnino et al., 2013). In a second cross-sectional study conducted with an early adolescent sample, disorganized representations were positively correlated with antisocial-aggressive responses, and secure attachment representations were negatively correlated with antisocial-aggressive responses (Granot & Mayseless, 2012).

Aggressive response evaluation.

In the only study of which we are aware to investigate attachment and aggressive response evaluation, children with secure versus insecure attachment in infancy were compared on their evaluation of competent, inept, and aggressive responses in middle childhood (Ziv, Oppenheim, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2004). Children who were securely attached in infancy differentiated the responses, associating competent responses with positive interpersonal and instrumental outcomes but inept or aggressive responses with negative social outcomes. Children who were insecurely attached in infancy did not make such discriminations, instead associating all three responses with negative outcomes. No associations emerged between attachment disorganization in infancy and response evaluation (Ziv, Oppenheim, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2004).

Parenting Behaviors and Children’s Social Information Processing

Many attachment researchers posit that child functioning is not solely a function of developmental history but also current experience. For example, studies have demonstrated the importance of considering later assessments of parent-child relationship quality in addition to infant attachment when predicting preschool social competence and behavior problems (Egeland, Kalkoske, Gottesman, & Erickson, 1990; Sroufe, Egeland, & Kreutzer, 1990). Studies examining antecedent and concurrent parenting behaviors associated with maladaptive social information processing are reviewed next, with particular attention paid to parenting behaviors, such as sensitivity and harsh behaviors, identified as relevant to the development of attachment and internal working models.

Hostile cue interpretations.

Two studies have supported a link between harsh parenting behaviors and hostile attributional bias (Gomez, Gomez, DeMello, & Tallent, 2001; Weiss, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1992). Specifically, greater physical punishment has been linked with increased hostile attributional bias in kindergartners (Weiss, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1992), and child-reported maternal controlling behaviors predicted children’s hostile attributional bias one year later in a sample of aggressive clinic-referred children in middle childhood (Gomez, Gomez, DeMello, & Tallent, 2001). However, early maternal sensitivity did not predict hostile attributional bias at 54 months or 1st grade (Raikes & Thompson, 2008). Similarly, in a different longitudinal study, harsh parenting during infancy and early childhood did not predict hostile attributional bias during preschool (Runions & Keating, 2007).

Aggressive goals.

To the best of our knowledge, no longitudinal studies have examined sensitive parenting as a predictor of children’s aggressive goals. However, parent report of corporal punishment in 4th grade was found to be concurrently associated with dominance goals for boys (Heidgerken, Hughes, Cavell, & Willson, 2004).

Aggressive responses.

Two longitudinal studies did not find a link between maternal negative control or harsh parenting and children’s aggressive response generation (Heidgerken, Hughes, Cavell, & Willson, 2004; Runions & Keating, 2007). However, using maternal retrospective self-report, Weiss, Dodge, Bates, and Pettit (1992) found that greater physical punishment was associated with children’s increased tendency to generate aggressive responses. In a sample of aggressive clinic-referred children, children’s perceptions of maternal support and warmth were negatively associated with their aggressive responses one year later, whereas children’s perceptions of maternal controlling behaviors were positively associated with their aggressive responses (Gomez, Gomez, DeMello, & Tallent, 2001). Of note, Raikes and Thompson (2008) found that concurrent and early maternal sensitivity were negatively associated with aggressive responses, and these effects for sensitivity contributed over and above the effects of secure attachment in infancy or early childhood.

Aggressive response evaluations.

Links between coercive parenting behaviors and more positive evaluations for aggressive responses with peers have been found in two studies, one with preschoolers and one with first and fourth graders (Hart, Ladd, & Burleson, 1990; Pettit, Harrist, Bates, & Dodge, 1991). Additionally, in one study with preschoolers and kindergartners, observed maternal negative control was associated with children’s maladaptive response evaluation two to four weeks later (Ziv, Kupermintz, & Aviezer, 2016).

The Current Study

Although existing literature suggests links between attachment and SIP, to the best of our knowledge, attachment disorganization in infancy has never been linked to maladaptive SIP in middle childhood. This is surprising, given that disorganized attachment is a consistent predictor of externalizing symptoms (Fearon et al., 2010) and poor peer relations (Jacobvitz & Hazen, 1999; Lyons-Ruth, Alpern, & Repacholi, 1993; Seibert & Kerns, 2015). Additionally, to the best of our knowledge, only one study has examined both attachment and parental sensitivity (Raikes & Thompson, 2008) as predictors of social information processing. Given the importance of taking into account not only attachment quality during infancy but also later assessments of parent-child relationship quality when predicting child outcomes, this is a critical gap in the literature. Thus, the goal of the current study was to investigate the link between disorganized attachment in infancy and maladaptive SIP in middle childhood, while also accounting for parental sensitivity in middle childhood.

We hypothesized that children with disorganized attachments would interpret ambiguous provocation more hostilely, set more aggressive goals, endorse more aggressive responses, and evaluate those aggressive responses more positively, than children with secure or organized attachments. Relations between disorganized attachment in infancy and SIP in middle childhood were the focal interest for the current study, but relations between insecure attachment in infancy and SIP were also explored. Due to the contradictory findings with regard to attachment insecurity and SIP, we made no specific hypotheses regarding attachment insecurity’s relation to specific steps of SIP. Although the focus of the current study was to examine links between disorganized attachment in infancy and maladaptive SIP in middle childhood, we also hypothesized that higher levels of parental sensitivity in middle childhood would be associated with more adaptive SIP. In other words, children with highly sensitive parents would be less likely to interpret ambiguous provocation hostilely, set aggressive goals, endorse aggressive responses, and evaluate those aggressive responses positively than children with less sensitive parents.

Method

Participants

A total of 82 children participated in the current study. These children had been recruited as infants to participate in a randomized clinical trial testing the efficacy of an intervention for parents. Child welfare agencies in a large, mid-Atlantic city referred parents with children at high risk for maltreatment. Fifty-four percent (n = 44) of the children were male. Just over 89% of the children (n = 73) were African American or Biracial, and the remainder were White. Twenty-four percent (n = 20) were Hispanic or Latino, and 76% were non-Hispanic. When parental sensitivity and children’s SIP patterns were assessed, parents ranged in age from 22.77 to 63.65 years (M = 37.17, SD = 10.58). All parents were female, with the exception of 5 males (6%). Just over 78% of the caregivers (n = 65) were African American or Biracial, and the remainder were White. Twenty-two percent (n = 18) were Hispanic or Latino, and 78% were non-Hispanic. Twenty-five parents (30%) did not complete high school, 43 parents (52%) earned a high school diploma or passed the GED exam, 11 parents (13%) completed some college, and three parents (4%) completed college or a graduate program. The average household income was approximately $25,000, and 45 caregivers (55%) reported receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or other welfare benefits. Eleven parents (13%) were married, 23 parents (28%) reported being in a romantic relationship and living with their partner, 31 parents (38%) reported being in a romantic relationship and not living with their partner, and 17 parents (21%) were not in a romantic relationship.

Procedures

When families enrolled in the study, they were randomized to receive the experimental intervention (Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-Up; ABC; n = 38) or the control intervention (Developmental Education for Families; DEF; n = 44). Both interventions were delivered over the course of ten weeks in families’ homes. Intervention sessions were an hour long and led by a trained interventionist (referred to as a parent coach). ABC was developed to help parents increase nurturance to child distress, increase sensitivity to child signals, and decrease frightening and harsh behaviors (Bernard, Meade, & Dozier, 2013). Parent coaches provided “in-the-moment” feedback during ABC sessions to help parents practice intervention targets when interacting with their children. During DEF sessions, parent coaches focused on enhancing children’s cognitive and motor development; coaches provided information about developmental milestones and encouraged parents to participate in activities promoting children’s cognitive and motor development.

Children’s attachment quality was assessed post-intervention, when children were on average 19.39-months-old (SD = 6.07). Parental sensitivity and children’s SIP were assessed at a follow-up visit during middle childhood, when children were on average 8.39-years-old (SD = 0.33). Data collection for attachment quality was completed from 2007 – 2010, and data collection for parental sensitivity and children’s SIP patterns was completed from 2014 – 2016.

Participants were included in the analyses if information about the child’s attachment quality and SIP at age eight were both available. Attrition analyses demonstrated that there were no significant differences between the sample of children who completed the visit in middle childhood and the original sample of parents randomized to receive ABC or DEF (n = 212) based on demographic characteristics at the time of enrollment (including parent age, parent education level, family income, marital status, and employment status), parent gender, parent race/ethnicity, child gender, and child race/ethnicity. Similarly, there were no significant differences with regard to demographic characteristics at the time of enrollment between the subsample of children who had both attachment quality and SIP data at age eight and children who were missing attachment quality or SIP data.

Data Collection

Attachment quality.

When children were infants, they completed the Strange Situation with their parents. The Strange Situation is a laboratory procedure developed to assess children’s reliance on their parents when they are upset or distressed (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). It is approximately 24 minutes long and consists of two separations from and subsequent reunions with the parent.

Using criteria identified by Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, and Wall (1978), children were classified as secure, avoidant, resistant, or disorganized. During the reunion, children who sought contact with and were soothed by their caregivers were classified as secure. Children who did not look to the caregiver for reassurance or turned away were classified as avoidant. Children who showed a mixture of proximity seeking and resistance, combined with an inability to be soothed, were classified as resistant. Finally, using guidelines specified by Main and Solomon (1990), children were classified as disorganized if they met the threshold for disorganized behaviors, such as displaying contradictory behaviors, freezing or stilling, approaching the stranger when upset, expressing fear when the parent returns, and disoriented wandering. Children who were classified as disorganized were given a secondary classification of secure, avoidant, or resistant.

Blind to other study information, coders classified each participant’s Strange Situation video. The primary coder, who had previously attended Strange Situation coding training at the University of Minnesota and passed the reliability test, coded all videos. The second coder, an expert coder of Strange Situations and co-leader of Strange Situation coder training, coded 34% of the videos. The two coders agreed on 85% of the classifications including both the original classification as secure, avoidant, resistant, or disorganized and the secondary classification of disorganized children as also secure, avoidant, or resistant (k = .74). In addition, the two coders agreed on 92% of two-way secure-insecure classifications (k = .76) and 87% of the two-way organized-disorganized classifications (k = .76). Any disagreements were resolved by conferencing. Alan Sroufe, another expert coder and leader of Strange Situation coder training, provided consultation for particularly challenging disagreements.

Parental sensitivity.

When children were eight years old, they completed a parent-child interaction task with their primary caregiver. For this task, parents and children were instructed to have a five-minute conversation focused on planning the perfect birthday party for the child. This discussion task was developed based on similar tasks that have been used in other studies assessing parental sensitivity during middle childhood and early adolescence (e.g., NICHD ECCRN, 2008; Sroufe, 1991). These interactions were video-recorded and later coded for parental sensitivity by trained research assistants. The sensitivity scale assessed the parent’s ability to “follow the child’s lead” based on the child’s interests, signals, and capabilities. Examples of sensitive behaviors during this task might include the parent asking open-ended questions, providing well-timed vocalizations, matching the child’s energy and affect, encouraging the child’s contributions, and expressing interest in the child’s ideas. Research assistants considered both quality and quantity of sensitive behaviors and assigned a single rating. A highly sensitive caregiver would receive a score of 5, whereas a highly insensitive caregiver would receive a score of 1. All observations were double-coded, and half points (i.e., 1.5, 2.5, 3.5, and 4.5) were used in this coding system. The interrater reliability for sensitivity was high (ICC = .88), and sensitivity ratings between the two coders were averaged. One parent-child dyad’s interaction task was uncodeable due to technical difficulties with the video camera.

Social information processing (SIP).

When children were eight years old, their SIP patterns were assessed using the Social Information Processing Application (SIP-AP), a computerized, Web-based, standardized measure designed to measure SIP cognitions. It consists of eight vignettes that portray everyday social situations with peers. Each vignette is filmed from the perspective of the protagonist and depicts an outcome for the protagonist that is negative, although the intentions of the perpetrator peer are ambiguous. The vignettes were developed by Dodge et al. (1986) and adapted for video presentation by Kupersmidt, Stelter, and Dodge (2011). Kupersmidt and colleagues developed video versions of these vignettes for use by and depicting elementary-school-aged boys. We collaborated with Janis Kupersmidt to create videos that were as similar as possible to the boy videos for use by and depicting elementary-school-aged girls. Child actors varied in race/ethnicity across the eight vignettes, and children of the same race/ethnicity were used in the boy and girl versions of each vignette.

The vignettes showed four different types of ambiguously aggressive behavior, with two vignettes depicting each type of aggression: a) relational aggression (e.g., protagonist approaches a group of peers whispering about a party to which he/she is not invited), b) physical aggression (e.g., protagonist is “frozen” during freeze tag and is bumped into by another child), c) covert aggression (e.g., protagonist loses a basketball game to a peer who may have cheated by crossing the free throw line), and d) property destruction (e.g., peer’s ball knocks over a marble-run structure the protagonist built). Vignette order was counterbalanced across participants.

Children were instructed to imagine that the situation shown in each vignette was happening to them. After watching each vignette on a computer monitor, they answered 12 multiple-choice questions assessing various aspects of SIP. Each question and its corresponding possible answers were visually presented and read aloud by the computer program. Children selected their answer with a mouse click and received a warning from the program if they proceeded through the questions too quickly.

The first four questions assessed children’s hostile cue interpretations in the ambiguous provocation depicted in the vignette. The first question asked about hostile attributional biases as they have been traditionally assessed (“Do you think the boy/girl intended to be mean?”). The remaining three questions further assessed children’s interpretations of the hostility of the ambiguous provocation. Specifically, children were asked about how rejected, disrespected, or angry the situation would make them feel (“How disliked or rejected [disrespected, angry] would you feel if this happened to you?”). Scores ranged from 1 (no, definitely not mean; not at all disliked or rejected; not at all disrespected; not at all angry) to 5 (yes, definitely mean; very very disliked or rejected; very very disrespected; very very angry). Scores for variables termed Hostile Attributions, Rejection Attributions, Disrespect Attributions, and Anger were calculated by averaging scores for the relevant question across the eight vignettes.

Two questions assessed children’s aggressive goals, including revenge goals (“Would you want to get back at the boy/girl or get the boy/girl in trouble if this happened to you?”) and dominance goals (“Would you want to make sure that the boy/girl knows that you are the boss and he/she can’t push you around?”). Scores ranged from 1 (no, definitely not) to 5 (yes, definitely). Scores for variables termed Revenge Goals and Dominance Goals were calculated by averaging scores for the relevant question across the eight vignettes.

Three questions assessed children’s reported aggressive responses, specifically overt aggression (“Would you push, hit, call names, or insult the boy/girl or try to hurt him/her in some other way?”), dominance (“Would you threaten the boy/girl, order him/her around, or let him/her know you are the boss in some other way?”), and relational aggression (“Would you talk about the boy/girl behind his/her back or try to get other kids to not play with him/her?”). Scores ranged from 1 (no, definitely not) to 5 (yes, definitely). Scores for variables termed Overt Aggressive Responses, Dominance Responses, and Relationally Aggressive Responses were calculated by averaging scores for the relevant question across the eight vignettes.

Three questions assessed children’s aggressive response evaluations, including aggressive outcome expectancy (“If you get back at the boy/girl, would things turn out to be good or bad for you?”), self-efficacy (“How easy or hard would it be for you to get back at the boy/girl?”), and moral acceptability (“How right or wrong would it be to get back at the boy/girl?”). Scores ranged from 1 (very bad for me; very hard; definitely the wrong thing to do) to 5 (very good for me; very easy; definitely the right thing to do). Scores for variables termed Aggressive Outcome Expectancies, Self-Efficacy for Aggression, and Moral Acceptability of Aggression were calculated by averaging scores for the relevant questions across the eight vignettes.

Results

Preliminary analyses for the attachment classifications and parental sensitivity examined gender and intervention differences. Additional preliminary analyses for the SIP variables examined descriptive statistics, internal consistency, interscale correlations, and gender and intervention differences. Furthermore, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) examined the number of factors that best represented the SIP variables.

Primary analyses addressed two questions. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to examine whether attachment security (secure versus insecure) and organization (organized versus disorganized) in infancy significantly predicted SIP at age eight when also controlling for concurrent parental sensitivity at age eight.

Descriptive statistics, internal consistencies, and preliminary data analyses were conducted using SPSS version 23. Mplus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998 – 2015) was used for all tests of model fit.

Preliminary Analyses for Attachment Variables

Forty children were classified as secure, eight children were classified as avoidant, and four children were classified as resistant. Fourteen children were classified as disorganized-secure, five children were classified as disorganized-avoidant, and five children were classified as disorganized-resistant. Four children who received a primary classification of disorganized demonstrated a mix of extreme behaviors that did not fit into previously identified categories and could not receive a secondary classification of secure, avoidant, or resistant. Similarly, there were two children who demonstrated a mix of extreme behaviors that did not fit into previously identified categories and could not receive a primary classification of organized (i.e., secure, avoidant, or resistant) or disorganized. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Lionetti, Pastore, & Barone, 2015), these children were included with the cases classified as disorganized.

Given the varied sample sizes across attachment classifications, two forced classifications (i.e., secure vs. insecure; organized vs. disorganized) were used to allow for sufficient power to detect effects. In the first two-way classification, children were classified as secure or insecure (organized-avoidant, organized-resistant, disorganized-avoidant, disorganized-resistant, or disorganized-cannot classify). In the second two-way classification, children were classified as organized (secure, avoidant, resistant) or disorganized (disorganized-secure, disorganized-avoidant, disorganized-resistant, or disorganized-cannot classify). For the secure-insecure

dichotomy, 54 children were classified as secure, and 28 children were classified as insecure. For the organized-disorganized dichotomy, 52 children were classified as organized, and 30 children were classified as disorganized.

Gender differences in the classifications were examined using chi-square tests. Children’s gender was unrelated to the secure-insecure dichotomy, χ2 (1, N = 82) = 1.93, p = 0.17, and the organized-disorganized dichotomy, χ2 (1, N = 82) = 0.08, p = 0.77. Additional demographic variables (including parent age, parent education level, family income, parent gender, parent race/ethnicity, child age, and child race/ethnicity) were unrelated to attachment classifications.

Chi-square tests also assessed whether there were intervention group differences (intervention versus control) in attachment classifications. Bernard and colleagues (2012) previously reported attachment findings from the same randomized controlled trial using a larger sample of participants (n = 120) than in the current study. In the larger sample, 53 children (44%) were classified as having a disorganized attachment. Additionally, children whose parents received ABC were significantly less likely to be classified as having a disorganized attachment than children who had received the control intervention. In this sample of 82 children, intervention group was unrelated to the secure-insecure dichotomy, χ2 (1, N = 82) = .85, p = 0.36, and the organized-disorganized dichotomy, χ2 (1, N = 82) = 1.17, p = 0.28.

Preliminary Analyses for Parental Sensitivity

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the parental sensitivity variable. Parent education at the time of the middle childhood visit was unrelated to sensitivity ratings, r = .07, df = 80. Household income was also unrelated to sensitivity ratings, r = −.08, df = 73. Sensitivity ratings were not significantly associated with the age of the child or parent, gender of the child or parent, or the race/ethnicity of the child or parent. The intervention groups did not differ in sensitivity ratings in middle childhood, t(79) = .002, p = .99. Additionally, intervention and sensitivity ratings did not interact to predict any SIP variables at age eight.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, Skew, and Internal Consistency for Social Information Processing and Parental Sensitivity Variables

| α | M | SD | Skew | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hostile Attributions | 0.60 | 3.40 | 0.85 | −0.45 |

| Rejection Attributions | 0.78 | 3.52 | 0.99 | −0.33 |

| Disrespect Attributions | 0.83 | 3.53 | 1.03 | −0.26 |

| Anger | 0.84 | 3.66 | 1.00 | −0.42 |

| Revenge Goals | 0.83 | 2.85 | 1.22 | 0.14 |

| Dominance Goals | 0.90 | 2.86 | 1.38 | 0.11 |

| Overt Aggressive Responses | 0.90 | 2.07 | 1.24 | 1.01 |

| Dominance Responses | 0.88 | 2.07 | 1.16 | 0.98 |

| Relationally Aggressive Responses | 0.92 | 2.25 | 1.33 | 0.72 |

| Aggressive Outcome Expectancy | 0.92 | 2.56 | 1.46 | 0.40 |

| Self-Efficacy for Aggression | 0.91 | 2.98 | 1.38 | 0.10 |

| Moral Acceptability of Aggression | 0.91 | 2.10 | 1.26 | 0.92 |

| Parental Sensitivity | - | 2.80 | 0.83 | 0.09 |

Preliminary Analyses for SIP Variables

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, skewness) and internal consistencies for the SIP variables. None of the variables were significantly skewed. The internal consistency for Hostile Attributions was acceptable but low (α = 0.60). Internal consistency was also lowest for the Hostile Attributions scale in Kupersmidt, Stelter, and Dodge (2011), likely because this variable is particularly influenced by slight differences in the ambiguity of the video vignettes, which are challenging to standardize. Table 2 provides zero-order interscale correlations among the SIP variables.

Table 2.

Interscale Correlations for Social Information Processing Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Hostile Attributions | - | .56** | .51** | .50** | .38** | .33* | .26* | .27* | .28* | .23* | .27* | .19 |

| 2. Rejection Attributions | - | .91** | .82** | .61** | .39** | .33** | .30* | .31** | .30* | .29** | .25* | |

| 3. Disrespect Attributions | - | .84** | .61** | .41** | .34** | .31** | .33** | .18 | .29** | .18 | ||

| 4. Anger | - | .67** | .46** | .43** | .39** | .40** | .35** | .34** | .28* | |||

| 5. Revenge Goals | - | .62** | .65** | .64** | .65** | .40** | .50** | .43** | ||||

| 6. Dominance Goals | - | .60** | .70** | .54** | .25* | .32** | .18 | |||||

| 7. Overt Aggressive Responses | - | .84** | .89** | .37** | .35** | .35** | ||||||

| 8. Dominance Responses | - | .84** | .36** | .43** | .31** | |||||||

| 9. Relationally Aggressive Responses | - | .38** | .38** | .37** | ||||||||

| 10. Aggressive Outcome Expectancies | - | .63** | .67** | |||||||||

| 11. Self-Efficacy for Aggression | - | .44** | ||||||||||

| 12. Moral Acceptability of Aggression | - |

Note. p < .05,

p < .01

Two MANOVAs with follow-up ANOVAs tested for gender and intervention differences in the 12 SIP variables. No significant intervention differences emerged for the 12 SIP variables. Only one gender difference emerged; females reported significantly higher levels of dominance goals than males (M = 3.19, SD = 1.27 and M = 2.58, SD = 1.43, respectively; p = .05, d = 0.45). The SIP variables did not differ based on other demographic variables (e.g., family income, parent age, child age, child race/ethnicity).

SIP-AP factor structure.

Analyses began with the estimation of a hypothesized four-factor model identified in prior research (Kupersmidt, Stelter, & Dodge, 2011). The four hypothesized factors reflected underlying dimensions of the SIP framework: Hostile Cue Interpretations, Aggressive Goals, Aggressive Responses, and Aggressive Response Evaluations. Similar to Kupersmidt, Stelter, and Dodge (2011), the variables tested in this CFA were the 12 individual SIP scores, which were calculated by averaging the scores of the individual items across vignettes. These item means were analyzed in a partial aggregation model (Bagozzi & Heatherton, 1994), which reduces the number of estimated parameters and is advantageous with smaller sample sizes.

The hypothesized four-factor model was specified as such: 1) the latent variable of Hostile Cue Interpretations was specified by loading Hostile Attributions, Rejection Attributions, Disrespect Attributions, and Anger; 2) the latent variable of Aggressive Goals was specified by loading Revenge Goals and Dominance Goals; 3) the latent variable of Aggressive Responses was specified by loading Overt Aggressive Responses, Dominance Responses, and Relationally Aggressive Responses; 4) the latent variable of Aggressive Response Evaluations was specified by loading Aggressive Outcome Expectancies, Self-Efficacy for Aggression, and Moral Acceptability of Aggression.

The fit statistics for this hypothesized model were adequate [χ2(48, n = 82) = 74.92, p < .01, RMSEA = .08(90% CI = .04–0.12), CFI = .97, TLI = .95, SRMR = .05], as indicated by a variety of sources (Browne & Cudeck, 1992; Hu & Bentler, 1998, 1999; Kline, 2005). The chi-square test was significant, but the relative chi-square, or χ2 divided by the degrees of freedom, was suggestive of adequate fit (e.g., Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007; Wheaton, Muthén, Alwin, & Summers, 1977). Modification indices were examined to assess ways in which model fit could be improved; results indicated that the uniqueness for Dominance Goals and Dominance Responses should be allowed to correlate. Given their theoretical and behavioral associations, this addition to the model was justifiable.

The fit statistics for the modified model were adequate [χ2(47, n = 82) = 56.12, p = .17, RMSEA = .05(90% CI = .00–0.09), CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, SRMR = .05]. The fit of the modified model was significantly better than the original model, Δχ2(1) = 18.80, p < .001. Depicted in Table 3, the standardized factor loadings for the model were all significant and high (Stevens, 2002). All of the SIP latent variables were significantly correlated with one another in the expected directions, with correlations ranging from .34 to .81.

Table 3.

SIP-AP Model Factor Loadings

| Social Information Processing Construct | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIP Variable | Hostile Cue Interpretations | Aggressive Goals | Aggressive Responses | Aggressive Response Evaluations |

| Hostile Attributions | 0.57 | |||

| Rejection Attributions | 0.94 | |||

| Disrespect Attributions | 0.96 | |||

| Anger | 0.88 | |||

| Revenge Goals | 0.89 | |||

| Dominance Goals | 0.68 | |||

| Overt Aggressive Responses | 0.94 | |||

| Dominance Responses | 0.89 | |||

| Relationally Aggressive Responses | 0.95 | |||

| Aggressive Outcome Expectancies | 0.88 | |||

| Self-Efficacy for Aggression | 0.70 | |||

| Moral Acceptability of Aggression | 0.73 | |||

Note. All scale loadings are significant at p <.001.

Internal consistencies of the four composite scales were calculated and indicated that the composites had adequate reliability. The Cronbach’s coefficient α was .90 for Hostile Cue Interpretations, .76 for Aggressive Goals, .95 for Aggressive Responses, and .80 for Aggressive Response Evaluations. Coefficient omega, which does not assume that all of the items load equally onto the latent variable (Dunn, Baguley, & Brunsden, 2014), also indicated that the items had adequate reliability. Coefficient omega was .92 for Hostile Cue Interpretations, .76 for Aggressive Goals, .95 for Aggressive Responses, and .83 for Aggressive Response Evaluations.

Attachment Classification Differences in SIP Constructs

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) examined whether attachment organization (i.e., organized versus disorganized) and attachment security (i.e., secure versus insecure) as assessed in infancy and parental sensitivity in middle childhood significantly predicted SIP constructs at age eight. SEM is advantageous because it allows the estimation of latent variable means, accounts for unreliability of measures, and can be more powerful than MANOVA (Thompson & Green, 2006).

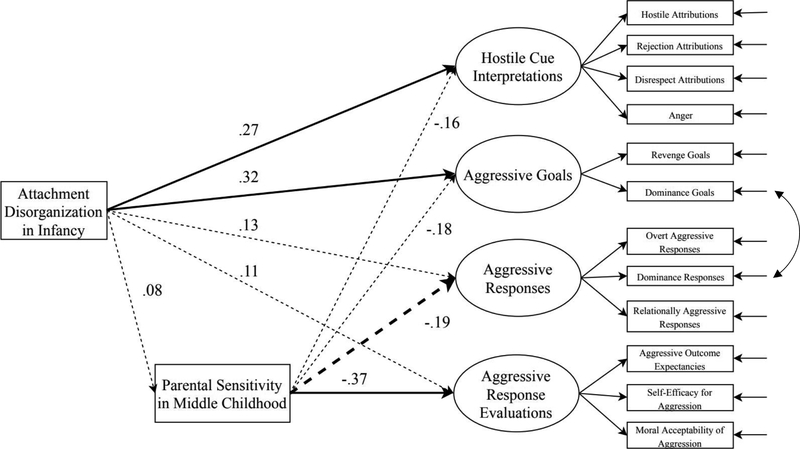

To assess whether attachment organization was a significant predictor of SIP constructs, the organized-disorganized classification was included as a categorical predictor in the four-factor SIP model. Hostile Cue Interpretations, Aggressive Goals, Aggressive Responses, and Aggressive Response Evaluations were regressed onto attachment organization. Parental sensitivity was also included in the model such that sensitivity was regressed onto attachment organization, and Hostile Cue Interpretations, Aggressive Goals, Aggressive Responses, and Aggressive Response Evaluations were regressed onto sensitivity. The fit statistics for this hypothesized model were adequate [χ2(63, n = 82) = 69.97, p = .25, RMSEA = .04(90% CI = .00–0.08), CFI = .99, TLI = .99, SRMR = .05]. Table 4 depicts factor interscale correlations. Attachment organization significantly predicted two SIP constructs: Hostile Cue Interpretations and Aggressive Goals (Figure 1). With respect to Hostile Cue Interpretations, children with disorganized attachments in infancy interpreted ambiguous provocations more negatively (as indicating more hostility, rejection, and disrespect and as resulting in more anger) at age eight than children with organized attachments. For Aggressive Goals, children with disorganized attachments endorsed significantly more revenge and dominance goals than children with organized attachments. Paternal sensitivity was marginally associated with aggressive responses and significantly associated with aggressive response evaluation. Specifically, lower levels of paternal sensitivity were marginally associated with children’s endorsement of more aggressive responses and significantly associated with more positive evaluations for aggressive responses.

Table 4.

Interscale Correlations between Social Information Processing Constructs

| Factor | Hostile Cue Interpretations | Aggressive Goals | Aggressive Responses | Aggressive Response Evaluations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hostile Cue Interpretations | - | .72** | .41** | .30** |

| Aggressive Goals | .69** | - | .83** | .55** |

| Aggressive Responses | .40** | .82** | - | .51** |

| Aggressive Response Evaluations | .28* | .53** | .50** | - |

Note. p < .05,

p < .01. Correlations for model with attachment insecurity as a predictor depicted above the diagonal, and correlations for model with attachment disorganization as a predictor below the diagonal.

Figure 1. Structural Equation Model of Attachment Disorganization and Sensitivity as Predictors of SIP Constructs.

Note. Standardized estimates are depicted. Solid lines indicate significant relations (p < .05), bolded dashed lines indicate marginally significant relations (p < .10), and dashed lines indicate non-significant relations. For ease of interpretation, relations between SIP latent variables and estimates of SIP variable loadings onto latent variables are not pictured.

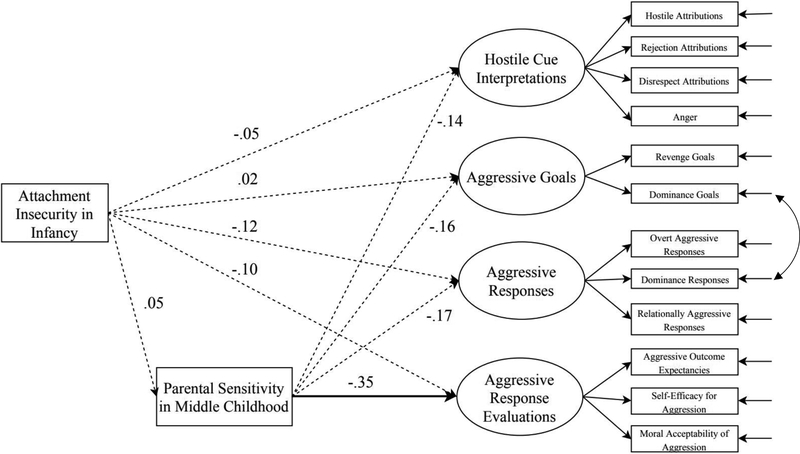

To assess whether attachment security was a significant predictor of SIP constructs, the secure-insecure classification was included as a categorical predictor in the four-factor SIP model. Hostile Cue Interpretations, Aggressive Goals, Aggressive Responses, and Aggressive Response Evaluations were regressed onto attachment security. Parental sensitivity was also included in the model such that sensitivity was regressed onto attachment security, and Hostile Cue Interpretations, Aggressive Goals, Aggressive Responses, and Aggressive Response Evaluations were regressed onto sensitivity. The fit statistics for this hypothesized model were adequate [χ2(63, n = 82) = 68.62, p = .29, RMSEA = .03(90% CI = .00–0.08), CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, SRMR = .05]. Attachment security in infancy did not significantly predict any of the SIP constructs at age eight (Figure 2). Again, lower levels of sensitivity were positively associated with more positive evaluations for aggressive responses. Table 4 depicts factor interscale correlations. Please see the electronic supplement for additional exploratory analyses comparing the organized-secure and organized-insecure groups on SIP latent variables and a series of t-tests examining differences on SIP composite variables based on attachment disorganization and insecurity.

Figure 2. Structural Equation Model of Attachment Insecurity and Sensitivity as Predictors of SIP Constructs.

Note. Standardized estimates are depicted. Solid lines indicate significant relations (p < .05), bolded dashed lines indicate marginally significant relations (p < .10), and dashed lines indicate non-significant relations. For ease of interpretation, relations between SIP latent variables and estimates of SIP variable loadings onto latent variables are not pictured.

Discussion

The current study was designed to enhance our understanding of the relations between attachment quality in infancy and parental sensitivity and SIP patterns in middle childhood. We hypothesized that children with disorganized attachments would interpret ambiguous provocation more hostilely, set more aggressive goals, endorse more aggressive responses, and evaluate those aggressive responses more positively than children with organized attachments. We explored whether attachment insecurity in infancy might be related to maladaptive SIP in middle childhood, but no specific hypotheses were generated for attachment insecurity in relation to specific steps of SIP. Additionally, we explored whether higher levels of parental sensitivity in middle childhood would be associated with more adaptive SIP.

Results provided support for our hypothesis that attachment disorganization predicts two steps of the SIP model. Specifically, children with disorganized attachments in infancy displayed more hostile attributional bias and endorsed more aggressive goals in middle childhood than children with organized attachments. Although theorists have speculated on links between attachment disorganization and maladaptive SIP (e.g., Jacobvitz & Hazen, 1999; Ziv, Oppenheim, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2004), to our knowledge, this is the first study to link attachment disorganization to hostile attributional bias, as well as the first longitudinal study to link attachment disorganization in infancy to aggressive goals. Considering that smaller effect sizes are typically observed when studies assess SIP using multiple-choice questions or video stimuli (Orobio de Castro et al., 2002), these significant associations are particularly notable.

The links between attachment disorganization and both hostile attributional bias and aggressive goals are theoretically supported and have important implications for children’s peer relations. Children with disorganized attachments are likely to experience harsh and frightening caregiving (Main & Hesse, 1990), and these early experiences with caregivers may foster expectations that peers will also behave with hostility. If this expectation of hostility does indeed transfer from the caregiving context to the peer context, it may impact children’s peer relations broadly, particularly with respect to peer rejection. Previous studies have documented a perpetuating cycle between hostile attributional bias and peer rejection; children who over-attribute hostility toward peers are more likely to behave aggressively, and this aggression leads to increased peer rejection (Orobio de Castro et al., 2002). Rejecting interactions with peers only further children’s conviction that peers are hostile (Crick & Dodge, 1994).

Early caregiving experiences might also explain why attachment disorganization in infancy leads to aggressive goals in middle childhood. When caregivers act in frightening and harsh ways, this might lead children to believe that they should behave in hostile ways with peers. Additionally, it is proposed that children with disorganized attachments may be placed in an “unsolvable dilemma” in that they fear but also must rely on their caregivers (Main & Hesse, 1990). As a result, they might endorse more revenge and dominance goals with their peers to establish control and stability that they lack in the home environment. This is consistent with the finding that children with disorganized attachments during infancy are more likely to demonstrate controlling behaviors with their parents than children with organized attachments (Lyons-Ruth, Alpern, & Repacholi, 1993). An orientation toward aggressive goals is also aligned with the meta-analytic finding that attachment disorganization is predictive of later externalizing symptomatology (Fearon et al., 2010). Aggressive goals are problematic because they suggest that children might use maladaptive strategies to solve social problems (Crick & Dodge, 1994). It is challenging for children to hold different social goals in their head at once (Erdley & Asher, 1996). If children with disorganized attachments have aggressive goals, they are less likely to hold prosocial goals that would encourage conflict resolution, cooperation, and kindness. This might reduce their ability to engage in behaviors that promote positive peer relations and further increase their risk of peer rejection.

In contrast, disorganized attachment in infancy did not predict aggressive responses or the evaluation of aggressive responses in middle childhood, a finding that is consistent with a previous study (Ziv, Oppenheim, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2004). The “breakdown in strategy” that distressed infants with disorganized attachments demonstrate in the presence of their caregivers may translate to the later peer context and render these children unable to respond consistently or systematically with aggressive behavior, even when their SIP tendencies at earlier stages of the model would suggest that aggressive responses would follow. The SIP-AP also did not inquire about other negative responses, such as withdrawal, that might be more typical of children with disorganized attachments in infancy. With regard to aggressive response evaluations, children with disorganized attachments exhibit conflicting behaviors when they are in distress, and this might reduce children’s ability to evaluate the efficacy of specific behaviors in the peer context.

Attachment security in infancy did not predict any step of the SIP model in middle childhood. This null result may be due to low power resulting from a small sample size, particularly with regard to the number of children classified as organized-insecure, and the small effect sizes that result when SIP is assessed using multiple-choice questions and video stimuli (Orobio de Castro et al., 2002). It is also possible that the current study’s forced attachment classification system may have resulted in the null result. However, the finding is consistent with two prior studies that also did not find an association between attachment security and children’s tendency to view ambiguous provocations as hostile (Cassidy, Kirsh, Scolton, & Parke, 1996; Raikes & Thompson, 2008). Both of these studies, as well as the current study, assessed hostile attributional bias using peers’ ambiguous provocations as stimuli. In contrast, two previous studies (Suess, Grossmann, & Sroufe, 1992; Ziv, Oppenheim, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2004) which did find an association between attachment security and hostile attributional bias used children’s interpretation of social conflict scenarios or more clearly hostile or benign behavior to index hostile attributional bias. Thus, when hostile attributional bias is strictly assessed using ambiguous provocations, previous literature and the current study consistently fail to find an association between the construct and attachment security.

With regard to the null findings for the remaining SIP constructs and attachment security, previous studies have found concurrent links between attachment insecurity and aggressive goals or responses in early childhood and early adolescence (Granot & Mayseless, 2012; Zaccagnino et al., 2013) but have failed to find longitudinal links from infancy to middle childhood (Ziv, Oppenheim, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2004). The studies finding concurrent links between attachment insecurity and aggressive goals or responses assessed both attachment representations and SIP using interviews with children. The shared method variance and temporal proximity characteristic of these studies might result in increased power to detect a relationship. The null finding for attachment security and aggressive response evaluation is in contrast to a previous study finding a longitudinal link between attachment insecurity in infancy and response evaluation in middle childhood (Ziv, Oppenheim, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2004). However, that study assessed aggressive response evaluation using clearly hostile and benign behaviors as stimuli rather than ambiguously provocative behaviors, which hold particular significance for understanding children’s peer relations (Dodge, McClaskey, & Feldman, 1985).

Parental sensitivity was only related to one stage of SIP. Specifically, lower levels of parental sensitivity were associated with more positive evaluations for aggressive responses than were higher levels of sensitivity. This finding is consistent with several other studies that have documented a link between coercive or controlling parenting behaviors and more positive evaluations for aggressive responses (e.g., Pettit, Harrist, Bates, & Dodge, 1991; Ziv, Kupermintz, & Aviezer, 2016). Some previous studies have documented links between parenting behaviors and other stages of SIP, including hostile attributional bias (Gomez, Gomez, DeMello, & Tallent, 2001), aggressive goals (Heidgerken et al., 2004), and aggressive responses (Raikes & Thompson, 2008). In contrast, however, when examining parental sensitivity or harsh parenting behaviors in relation to stages of SIP, other studies have failed to find an association when predicting hostile attributional bias (Raikes & Thompson, 2008) and aggressive response generation (Heidgerken et al., 2004; Runions & Keating, 2007). It is possible that these inconsistent findings might be due to differences with regard to the sample (e.g., clinically-referred due to aggressive behavior problems vs. CPS-involved due to concerns for maltreatment), study design (e.g., cross-sectional vs. longitudinal), methodology used to assess parenting (e.g., observational vs. parent-report) or SIP (e.g., open-ended questions vs. forced choice responses), or the age at which those variables were assessed.

Attachment disorganization in infancy predicted the first two stages of SIP, hostile attributional bias and aggressive goals, whereas parental sensitivity was associated with the final stage of SIP, aggressive response evaluation. These distinct relations underscore the importance of assessing different stages or steps of SIP and suggest that they might have different antecedents. For instance, perhaps non-conscious expectations regarding relationships may be heavily influenced by early experiences, whereas expectations about strategies for behaving in relationships develop later. This would potentially explain why attachment in infancy would be related to the interpretation of cues and goal formation and why concurrent parental sensitivity would be related to the evaluation of specific behavioral responses. Similarly, it is also possible that earlier stages of SIP are more strongly influenced by automatic cognitive processes and later stages, particularly response generation and evaluation, require slower processing and that the child mentally generate possible responses. During the response generation and evaluation stages, children may be more likely to draw from more recent interaction patterns.

Interestingly, in the current study, attachment disorganization, and not attachment insecurity, in infancy predicted hostile attributional bias and aggressive goals in middle childhood. These results are aligned with previous work suggesting that disorganized attachment may place children at even higher risk for negative peer relations than insecure attachment (e.g., Groh et al., 2014). Furthermore, attachment disorganization rather than insecurity has been associated with problematic outcomes beyond SIP that may also manifest in the peer context, including physiological dysregulation (Bernard, Dozier, Bick, & Gordon, 2015), externalizing symptoms (Fearon et al., 2010), and dissociative symptoms in middle school, high school, and early adulthood (Carlson, 1998). In this respect, the present study advances our understanding of outcomes associated specifically with attachment disorganization and provides empirical evidence to further support intervening early to promote attachment organization.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

This study is marked by several strengths, with the first being the methodologies used to assess attachment quality and SIP. Given its strong psychometric properties and observational nature, the Strange Situation procedure has been perceived as the “gold standard” for examining children’s attachment quality. Similarly, the Social Information Processing Application (SIP-AP) provided a comprehensive and psychometrically strong evaluation of the multiple steps of children’s SIP (Kupersmidt, Stelter, & Dodge, 2011). Using video vignettes that were filmed from the first-person perspective, the SIP-AP assessed four distinct steps of SIP with multiple questions to assess each step. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use both of these measures to assess relations between children’s attachment quality in infancy and multiple steps of SIP in middle childhood.

Another strength of the study was its observational assessment of sensitivity. During this parent-child interaction task, children participated in a collaborative discussion with their parents. Specifically, children were instructed to plan the perfect birthday party. This conversation topic might mirror a discussion that a child would have a peer. However, in the current study, no intervention differences were found with regard to parental sensitivity. This contrasts with previous findings suggesting that the ABC intervention promotes sensitive caregiving in infancy through early childhood (Bick & Dozier, 2013; Bernard, Simons, & Dozier, 2015). On one hand, it is possible that parenting changes do not persist until middle childhood. On the other hand, it is possible that if the interaction task had been more stressful or elicited more distress from the child, intervention differences might have emerged. Similarly, it is possible that there were no links between attachment organization or security in infancy and parental sensitivity in middle childhood due to the nature of the task. For example, if the task had been more stressful, parents might have been more likely to demonstrate behavioral lapses and act in frightening or confusing ways with their children. Frightening or frightened maternal behaviors, in particular, have been linked with the development of disorganized attachments (e.g., Madigan et al., 2006). However, other studies with high-risk samples have also failed to find a link between children’s attachment quality and parenting behaviors (e.g., Haltigan et al., 2012).

The current study benefited from a longitudinal design with a unique sample. In the peer relations literature, many studies examine SIP in clinical samples, focusing on children who present with antisocial and aggressive behaviors (Orobio de Castro et al., 2002). The present study examined SIP in children who were referred by Child Protective Services (CPS) due to being at high risk for maltreatment in infancy. Although children in the sample were identified as being at risk for maltreatment, we did not have access to CPS records. As a result, it is impossible for the current study to examine relations between the experience of maltreatment and the development of disorganized attachment or to differentiate the effects of attachment disorganization from the effects of maltreatment on social information processing. Given that disorganized attachments are more common among children who have experienced maltreatment but not all children who develop disorganized attachments have a history of maltreatment (see Granqvist et al., 2017 for a review), this is an important area of future research.

This study has several other limitations. First, the small sample size may have resulted in inadequate power to detect some effects, and it did not permit comparisons between subtypes of insecure attachment classifications (i.e., avoidant and resistant). The current study’s sample was also observed to have a relatively restricted range with regard to demographic variables (e.g., family income, parent education level). Replicating these findings in a larger sample with a greater range in socioecomic status is an important next step. Additionally, although not the focus of the current study, some children in this sample received an attachment-based intervention during infancy. In addition to sensitivity, intervention effects were not observed for the SIP variables. Given the small sample size, we hesitate to interpret these findings heavily. However, the null findings might inform intervention and prevention work by suggesting that in order to reduce the risk for maladaptive SIP in middle childhood, intervention focused on promoting attachment quality during infancy would be enhanced by intervention during later developmental periods. This intervention might continue to promote attachment relationships within the context of the family while also incorporating skills that would promote the development of positive peer relationships. Second, the SIP-AP did not include items assessing children’s encoding abilities. Finally, although SIP in response to ambiguous provocations is an important aspect of children’s peer relations, we did not measure children’s actual behavior with peers. Given that the provocations used in the SIP-AP are ambiguous, it remains unclear whether children with disorganized attachments have a bias toward hostility or whether children with organized attachments have a bias toward benignity. Future research would benefit by assessing links between attachment and SIP using additional assessments of SIP and links between SIP deficits and actual behaviors with peers.

Findings from this study suggest additional exciting avenues for future research. Given that there are several pathways to disorganized attachment and different forms of disorganized attachment (Granqvist et al., 2017; Padrón et al., 2014), an important next step is to examine whether distinct indices of disorganization or atypical maternal behaviors (e.g., withdrawal, role-confusion) are related to SIP biases. Additionally, although meta-analytic findings indicate that disorganized attachments are associated with negative outcomes (e.g., Fearon et al., 2010), the effect sizes are small to moderate, suggesting that not all children with disorganized attachments experience those adverse outcomes. Future research might explore potential mediators and moderators of the relation between attachment quality in infancy and SIP in middle childhood; possibilities might include parental psychopathology, negative life events, and children’s emotion regulation. With a larger sample size and increased power, it would be beneficial to account for other variables that are known to affect peer competence (e.g., emotion regulation) and include later assessments of attachment quality or multiple assessments of parenting quality. Relatedly, the current sample consisted mostly of mothers and children. Future studies should explore the effect of father-child attachment or relationship quality in relation to social information processing.

Conclusion

Results from this longitudinal study indicate that, even when accounting for concurrent levels of parental sensitivity in middle childhood, attachment disorganization in infancy places children at risk for greater hostile attributional bias and more aggressive goals at age eight. As the first study to provide empirical evidence that attachment disorganization in infancy predicts maladaptive SIP in middle childhood, the study advances our understanding of problematic long-term outcomes associated with attachment disorganization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant R01 MH074374 R01MH084135 to the fifth author. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank the children and families who participated in this research. We also gratefully acknowledge the support of child protection agencies in Philadelphia.

References

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, & Wall S (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale, N.J: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R, & Heatherton T (1994). A general approach to representing multifaceted personality constructs: Application to state self-esteem. Structural Equation Modeling, 1, 35–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Dozier M, Bick J, & Gordon MK (2015). Intervening to enhance cortisol regulation among children at risk for neglect: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Development and Psychopathology, 27(3), 829–841. doi: 10.1017/S095457941400073X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Dozier M, Bick J, Lewis‐Morrarty E, Lindhiem O, & Carlson E (2012). Enhancing attachment organization among maltreated children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Child Development, 83, 623–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01712.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Simons R, & Dozier M (2015). Effects of an Attachment-based Intervention on CPS-Referred Mothers’ Event-related Potentials to Children’s Emotions. Child Development, 86, 1673–1684. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bick J, & Dozier M (2013). The effectiveness of an attachment‐based intervention in promoting foster mothers’ sensitivity toward foster infants. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34, 95–103. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, & Patterson CJ (2001). Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to peer rejection. Child Development, 72, 549–568. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne M, & Cudeck R (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods and Research, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EA (1998). A prospective longitudinal study of attachment disorganization/disorientation.Child Development, 69, 1107–1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Kirsh SJ, Scolton KL, & Parke RD (1996). Attachment and representations of peer relationships. Developmental Psychology, 32, 892–904. doi: 10.1177/0272431611403482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, & Dodge KA (1994). A review and reformulation of social information- processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 74–101. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, & Pettit GS (1990). Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science, 250, 1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, McClaskey CL, & Feldman E (1985). Situational approach to the assessment of social competence in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 344–353. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.3.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, McClaskey CL, Brown MM, & Gottman JM (1986). Social competence in children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, i–85.3807927 [Google Scholar]

- Dunn TJ, Baguley T, & Brunsden V (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105, 399–412. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Kalkoske M, Gottesman N, & Erickson MF (1990). Preschool behavior problems: Stability and factors accounting for change. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 31, 891–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb00832.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdley CA, & Asher SR (1996). Children’s social goals and self‐efficacy perceptions as influences on their responses to ambiguous provocation. Child Development, 67, 1329–1344. doi: 10.2307/1131703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon RP, Bakermans‐Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Lapsley AM, & Roisman GI (2010). The significance of insecure attachment and disorganization in the development of children’s externalizing behavior: A meta‐analytic study. Child Development, 81, 435–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01405.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine R, & Dodge KA (2006). Real-time decision making and aggressive behavior in youth: A heuristic model of response evaluation and decision (RED). Aggressive Behavior, 32, 604–624. doi: 10.1002/ab.20150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez R, Gomez A, DeMello L, & Tallent R (2001). Perceived maternal control and support: Effects on hostile biased social information processing and aggression among clinic-referred children with high aggression. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 42, 513–522. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granot D, & Mayseless O (2012). Representations of mother-child attachment relationships and social-information processing of peer relationships in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 32, 537–564. doi: 10.1177/0272431611403482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist P, Sroufe LA, Dozier M, Hesse E, Steele M, van Ijzendoorn M, ... & Steele H (2017). Disorganized attachment in infancy: a review of the phenomenon and its implications for clinicians and policy-makers. Attachment & Human Development, 19, 534–558. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2017.1354040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh AM, Fearon RP, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Steele RD, & Roisman GI (2014). The significance of attachment security for children’s social competence with peers: A meta-analytic study. Attachment & Human Development, 16(2), 103–136. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2014.883636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltigan JD, Lambert BL, Seifer R, Ekas NV, Bauer CR, & Messinger DS (2012). Security of attachment and quality of mother–toddler social interaction in a high-risk sample. Infant Behavior and Development, 35, 83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CH, Ladd GW, & Burleson BR (1990). Children’s expectations of the outcomes of social strategies: Relations with sociometric status and maternal disciplinary styles. Child Development, 61, 127–137. doi: 10.2307/1131053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW (1996). The company they keep: Friendships and their developmental significance. Child Development, 67, 1–13. doi: 10.2307/1131681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidgerken AD, Hughes JN, Cavell TA, & Willson VL (2004). Direct and indirect effects of parenting and children’s goals on child aggression.Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 684–693. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobvitz D, & Hazen N (1999). Developmental pathways from infant disorganization to childhood peer relationships In Solomon J & George C (Eds.), Attachment disorganization (pp. 127–159). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA (1996). Individual differences in friendship quality: Links to child-mother attachment In Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF & Hartup WW (Eds.), The companythey keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence (pp. 137–157). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kline R (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 2nd edition New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmidt JB, Stelter R, & Dodge KA (2011). Development and validation of the social information processing application: A Web-based measure of social information processing patterns in elementary school-age boys. Psychological Assessment, 23, 834–847. doi: 10.1037/a0023621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti F, Pastore M, & Barone L (2015). Attachment in institutionalized children: A review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 42, 135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons‐Ruth K, Alpern L, & Repacholi B (1993). Disorganized infant attachment classification and maternal psychosocial problems as predictors of hostile‐aggressivebehavior in the preschool classroom. Child Development, 64, 572–585. doi: 10.2307/1131270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K, Repacholi B, McLeod S, & Silva E (1991). Disorganized attachment behavior in infancy: Short-term stability, maternal and infant correlates and risk-related subtypes. Development and Psychopathology, 3, 377–396. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400007586 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan S, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Moran G, Pederson DR, & Benoit D (2006). Unresolved states of mind, anomalous parental behavior, and disorganized attachment: A review and meta-analysis of a transmission gap. Attachment & Human Development, 8, 89–111. doi: 10.1080/14616730600774458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M, & Hesse E (1990). Parents’ unresolved traumatic experiences are related to infant disorganized attachment status: Is frightened and/or frightening parental behavior the linking mechanism? In Greenburg MT, Cicchetti D, & Cummings E (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 161–182). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, & Solomon J (1990). Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern In Brazelton TB & Yogman MW (Eds.), Affective development in infancy (pp. 95–124). Westport, CT: Ablex Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- McElwain NL, Booth‐LaForce C, Lansford JE, Wu X, & Justin Dyer W (2008). A process model of attachment–friend linkages: Hostile attribution biases, language ability, and mother–child affective mutuality as intervening mechanisms. Child Development, 79, 1891–1906. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01232.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén BO (1997-2015). Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (1996). Characteristics of infant child care: Factors contributing to positive caregiving. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 11, 269–306. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(96)90009-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orobio de Castro B, Veerman JW, Koops W, Bosch JD, & Monshouwer HJ (2002). Hostile attribution of intent and aggressive behavior: A meta‐analysis. Child Development, 73, 916–934. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padrón E, Carlson EA, & Sroufe LA (2014). Frightened versus not frightened disorganized infant attachment: Newborn characteristics and maternal caregiving. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84, 201–208. doi: 10.1037/h0099390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, & Herrera C (1996). Interpersonal processes in friendship: A comparison of abused and nonabused children’s experiences. Developmental Psychology, 32, 1025–1038. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.6.1025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Harrist AW, Bates JE, & Dodge KA (1991). Family interaction, social cognition and children’s subsequent relations with peers at kindergarten. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 8, 383–402. doi: 10.1177/0265407591083005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raikes HA, & Thompson RA (2008). Attachment security and parenting quality predict children’s problem-solving, attributions, and loneliness with peers. Attachment & Human Development, 10, 319–344. DOI: 10.1080/14616730802113620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runions KC, & Keating DP (2007). Young children’s social information processing: Family antecedents and behavioral correlates. Developmental Psychology, 43, 838–849. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzinger S, Feldman RS, Hammer M, & Rosario M (1993). The effects of physical abuse on children’s social relationships. Child Development, 64, 169–187. doi: 10.2307/1131444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BH, Atkinson L, & Tardif C (2001). Child–parent attachment and children’s peer relations: A quantitative review. Developmental Psychology, 37, 86–100. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.1.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]