Abstract

Objective

To characterize the benefits and optimal dose of long-acting methylphenidate for management of long-term attention problems after childhood TBI.

Design

Phase 2, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled, dose-titration, cross-over clinical trial.

Setting

Outpatient, clinical research

Participants

26 children aged 6 to 17 years who were at least 6-months post TBI and met criteria for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) at time of enrollment.

Outcome Measures

Vanderbilt Rating Scale of attention problems, Pittsburgh Side Effects Rating Scale (PSERS), and vital signs.

Results

Among the 26 participants randomized, 20 completed the trial. The mean ages at injury and enrollment were 6.3 and 11.5 years, respectively. Eight participants had a severe TBI. On optimal dose of medication, greater reductions were found on the Vanderbilt parent rating scale for the medicated condition than for placebo (p=.022, effect size = .59). The mean optimal dose of methylphenidate was 40.5 mg (1.00 mg/kg/day). Preinjury ADHD diagnosis status was not associated with a differential medication response. Methylphenidate was associated with weight loss (~ 1 kg), increased systolic blood pressure (~3–6 point increase), and mild reported changes in appetite.

Conclusion

Findings support use of long-acting methylphenidate for management of long-term attention problems after pediatric TBI. Larger trials are warranted of stimulant medications, including comparative effectiveness and combination medication and non-medication interventions.

Keywords: clinical trial, traumatic brain injury, attention problems, pediatrics, medication

Introduction

Pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a world-wide health problem and among the most common causes of acquired morbidity.1–6 TBI results in 7,843 deaths, 46,260 hospitalizations, and 1,083,122 emergency department visits in children and young adults yearly in the United States.6 Early injuries can have a life-long impact.7 TBI-related psychiatric and neurobehavioral problems, including difficulties with concentration and memory, frequently occur within the first 3–24 months post injury.8–11 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a risk factor for pediatric TBI with approximately 20–30% of children with TBI having a premorbid diagnosis of ADHD12,13. However, 15–20% of children with no premorbid diagnosis of ADHD meet ADHD diagnostic criteria post-TBI. This condition is termed secondary ADHD (SADHD).12,13 SADHD has a pattern of ADHD-related disability similar to that of primary ADHD including academic, social, and parent-child relationship problems.12,13

Stimulant medication use has been extensively studied in children with primary ADHD14, but not as robustly in TBI populations. Several studies with adults demonstrated the safety and efficacy of stimulants in reducing TBI-related attention problems.15 However, there is a paucity of studies evaluating the use of stimulants to treat SADHD in children, despite their common clinical use.12,16 Studies evaluating stimulant use for attention problems following pediatric TBI have yielded mixed results.17–22 Prior work is limited by small heterogeneous samples, poorly defined ADHD diagnostic criteria for enrollment, and reliance on a single dose of methylphenidate, which was likely not optimal for some children. Given the frequency of attention problems after pediatric TBI and lack of evidence-based protocols to guide methylphenidate use for SADHD treatment, controlled studies are critically needed.

This trial sought to characterize methylphenidate response in children with persistent attention problems following TBI. Using a randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled, dose-titration, cross-over design, we hypothesized that methylphenidate would reduce attention problems and that higher doses would be associated with greater reductions in attention problems.

Methods

Participants and Recruitment

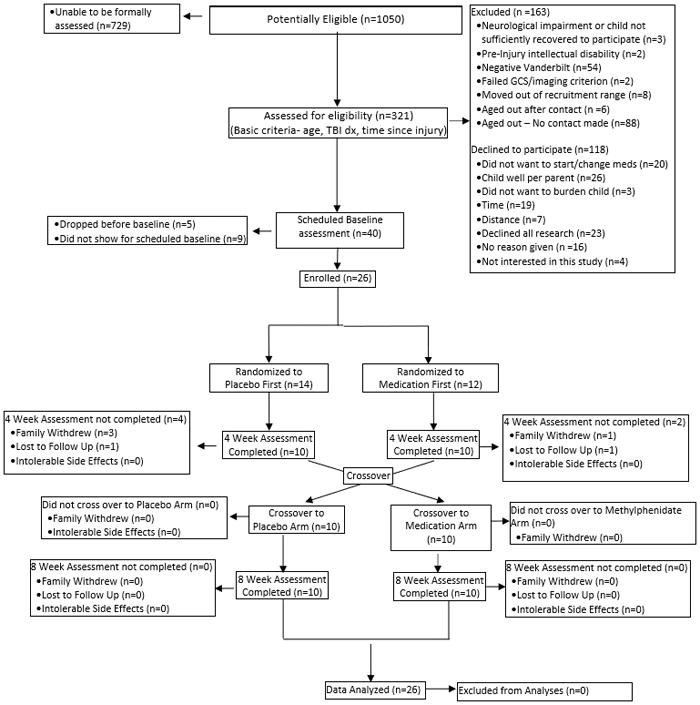

Recruitment and enrollment were completed between January 1, 2014 and July 20, 2017. Participants were recruited from a tertiary pediatric hospital in the Midwestern United States with a Level I trauma designation through the trauma registry, outpatient brain injury clinics, study advertisements displayed throughout the medical center, direct mailings, and telephone contact. Primary inclusion criteria were: ages 6–17 years, hospital admission for blunt head trauma, and a confirmed diagnosis of moderate to severe TBI as categorized by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score.23 Severe TBI was defined as a GCS score of ≤ 8 at any point after injury. Moderate TBI was defined as either a GCS score of 9–12 or a higher score with evidence of abnormalities on neuroimaging. The lower age limit of six years was based on clinical practice guidelines recommending stimulants be considered as first-line treatment for ADHD at age six years and older.14 Other inclusion criteria were: English as the primary language and positive endorsement of at least 6 of 9 current symptoms on at least one subscale of the Vanderbilt Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Parent Diagnostic Rating Scale (VADPRS)24 or met current criteria for ADHD based on the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School–age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-P/L). Children with preinjury diagnoses of developmental (e.g., autism, severe developmental delay) or neurological disorders (e.g., seizures, brain tumor, other brain malformation or acquired brain injuries) and children who were hospitalized for psychiatric reasons in the past 12 months were excluded. Children involved in active behavioral and/or medication treatments for attention problems and/or who had contraindications to methylphenidate use or were on medications that had potentially severe interactions with methylphenidate were also excluded. The CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 1) details enrollment.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

Baseline Interviews

The ADHD portion of the K-SADS-P/L was used to assess: (1) preinjury ADHD diagnostic status when children were age 4 years or older at the time of injury, and (2) current (i.e., at time of study enrollment) ADHD diagnostic status according to DSM-IV criteria.25 Consistent with previous investigations of pediatric TBI26–29, the McMaster Family Assessment Device 12-item General Functioning Scale (FAD-GF) was used to assess family functioning. The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) provided a baseline intelligence rating.27,30 Information on parental educational attainment and census track median income provided an index of socioeconomic status.

Measures

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was changes in symptoms ratings on the Vanderbilt ADHD parent rating scales (VADPRS).24,31 A measure of ADHD symptom severity (Total Symptom Score [TSS]) is computed by totaling the scores from items 1–18 (Inattentive + Hyperactive-impulsive domains), with a rating of none=0, occasionally=1, often=2, very often=3 provided. Scores for inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive domains were generated by totaling the 9 symptoms in these domains, and a TSS was computed by totaling items across domains. The average TSS served as the primary outcome measure, with exploratory analyses performed for the inattentive and hyperactive subscales. Internal consistency is excellent for the VADPRS subscales.24 Primary care givers or guardians with most contact with participant completed the measures. The oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), and anxiety/depression subscales on the parent Vanderbilt ratings were used to characterize comorbidities in the study population.24,32 Children ≥ 11 years completed the Vanderbilt form as a self-report.

Side Effects

The Pittsburgh Side Effects Rating Scale (PSERS) was used to assess participant- and parent-reported severity of adverse events, including dullness, tiredness, listlessness, headache, stomachache, loss of appetite, and trouble sleeping.33,34 Adverse events were rated as none=0, mild=1, moderate=2, or severe=3. Vital signs included heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration rate.

Design

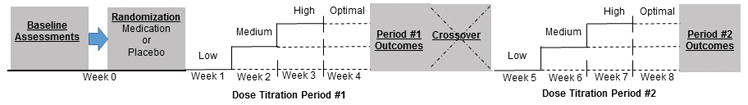

The study design was a randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled, dose-titration, cross-over clinical trial (Figure 2). It was approved by the institutional review board, and signed informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians at the initial visit. Children < 11 years provided verbal assent; older children gave verbal and signed assent. Eligible participants completed baseline measures and were randomized to long-acting methylphenidate (Concerta®) or placebo. Participants were asked to complete a 4-week period in their initial randomized condition and then switch to the other condition for an additional 4-week period. Long-acting methylphenidate was chosen since it is one of the most commonly used stimulants for primary ADHD management.14 Random number generation was used to develop randomization assignments. Using the randomization scheme, the investigational pharmacist dispensed pills in a masked fashion to study staff. Both participants and study staff with participant contact were masked to medication type. A research coordinator who did not interact with participants was assigned as a randomization broker if questions arose regarding randomization.

Figure 2. Study design.

Baseline assessments were completed prior to randomization. At the end of the baseline assessment, each participant was randomized to medication or placebo and received the low dose condition at the end of the enrollment visit (week 0). Upward dose titration to medium and high dose conditions was completed during weeks 2 and 3. After week 3, medication effects and side effects were reviewed for each dose condition and the optimal dose was determine. At the end of week 4, outcomes were measured. Participants then crossed-over to the opposite condition and repeated the same procedures. The total duration of the trial was 8 weeks.

Medication dosing and administration

Study medication consisted of identical capsules filled with either an inert white powder (placebo) or long-acting methylphenidate over-encapsulated to preserve double-masking. As depicted in figure 2, the first week consisted of the low-dose condition. Over the subsequent 3 weeks, the dose was titrated based on medication response and side effects to determine the optimal dose used for week 4. At the end of week 4, outcomes were assessed and participants crossed-over and repeated the same procedures for the opposite condition (i.e., methylphenidate or placebo). The same procedures for dose titration and optimal dose determination were performed for the methylphenidate and placebo conditions to preserve double-masking. Because the half-life of methylphenidate is below 12 hours and previous trials demonstrated that daily changes of methylphenidate are feasible35,36, a wash-out period was not used.

Participants weighing less than 25kg received 18mg (low), 27mg (medium), and 36mg (high) dosages; participants weighing above 25kg received 18mg (low), 36mg (medium), and 54mg (high) dosages. Only the above doses were used for titration and optimal dose visits; intermediate doses were not used. If there was room for improvement, defined as Vanderbilt Parent Ratings (VADPRS)24,31 TSS ≥ 9, the dosage was increased to the next highest dosage (e.g., medium dose for Week 2). If attention symptoms reached maximal anticipated clinical improvement, defined as VADPRS total score < 9, the dosage remained the same. A total score of 9 was chosen as the cut-off for maximal clinical improvement as this is approximately one standard deviation below the mean (i.e., less severe symptoms) for the best VADPRS (M = 19.52, SD = 10.90) TSS found in a developmental ADHD population treated with long-acting methylphenidate 37;it is also consistent with normative data indicating that mean total scores between approximately 7 and 12 (depending on child age and sex) are typical for a representative U.S. population of children between ages 5 and 17 years.38 If the side effects exceeded potential benefits, doses could be reduced to the previous week’s dosage or discontinued based on discussion with family and participant. Planned dose increases stopped when maximal anticipated clinical improvement was reached, side effects become prohibitive, or the trial ended.

All study measures were collected at baseline. In addition, weekly visits were conducted throughout the trial during which the VADPRS, side effects, and vital signs were collected. Visits typically occurred in the afternoons and evenings; however, there was variation depending on participants and families’ schedules.

Sample Size, a priori power calculations

Since this was a crossover trial, the variance of interest in estimating the sample size was the within subject variance. In studies looking at treatment effects of methylphenidate for developmental ADHD using parent and teacher attention symptom ratings, the effect sizes ranged from 1.02 – 1.05.39 In adult TBI, caregiver ratings of attention problems with methylphenidate treatment versus placebo yielded effect sizes of 0.44–0.50.40 A range of a priori sample size calculations considering a two period, two treatment cross-over study design and based on a paired t-test, two-sided alpha of .05 and 80% power indicated that a sample size of 24 would allow detection of an effect size of .6 and a sample size of 19 would allow detection of an effect size of .7. Therefore, the final sample size (n=20) in the context of this study provided 80% power to detect an effect size between .6 and .7.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample. Comparisons between conditions were assessed with t-tests and Fisher’s Exact tests when appropriate. Repeated measures linear mixed models41 were used to determine the efficacy of methylphenidate for treatment of attention problems. Analyses were based on intention to treat principles.42 In all models, baseline ratings were included as a covariate. The period of the evaluation (week 4 or week 8) and the interaction between period and treatment (which captures the potential carry over effect) were included as independent variables. Potential covariates including age, sex, time since injury, injury severity (GCS score), general intellectual ability (WASI), family functioning (FAD-GF), race, and socioeconomic status (as measured by maternal education, college graduate or not) were assessed for inclusion in models.10,11,43 Prior to constructing multivariate models, each potential covariate was examined individually with treatment group and period as well as the baseline value of the measure of interest to determine its relation with the dependent variable (in the presence of group and period effects). Covariates with p-values below 0.10 in these analyses were included in the final model. Multivariate models were then analyzed with and without preinjury ADHD diagnostic status as an independent variable to determine its potential influence on medication response.

The primary dependent variable was VADPRS TSS obtained at the end of the optimal dose week. Secondary outcomes were modeled in an exploratory fashion similarly to the primary dependent variable and included inattentive and hyperactive parent and self-report Vanderbilt ratings.

A medication effect was defined as a significant effect on the treatment term (medication versus placebo condition). Effect sizes were derived based on Least Squares (adjusted) mean differences divided by an adjusted estimate of the standard deviation: the standard error of the difference multiplied by the square root of the adjusted degrees of freedom.44 All analyses were conducted using the SAS ® statistical software package version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Demographics and baseline assessments

Twenty six individuals completed baseline assessments and were randomized. Table 1 summarizes participant demographics and characteristics. Mean age at injury and baseline visit were 6.3 (SD:4.1) and 11.5 (SD:2.8) years, respectively. The mean time since injury was 5.2 (SD:3.8) years. Six participants were female and 19 were white. Eight participants had a severe TBI, and the overall mean GCS was 11.9 (SD:4.2). Based on KSADS interview, 12 participants did not have preinjury ADHD, eight were too young (mean age 1.25 years) at the time of injury to assess preinjury ADHD status, and six met criteria for pre-injury ADHD (3 inattentive and 3 combined subtype) (Table 1). Comorbid conditions among groups were similar, with seven, one, and two participants meeting criteria for ODD, CD, and anxiety/depression, respectively, at the baseline assessment (Table 1). The only differences between completers and non-completers (Table 1) were that non-completers had higher inattentive scores on the self-report Vanderbilt and higher heart rate compared to completers. At enrollment, six participants had combined type, 18 had primarily inattentive and two had primarily hyperactive type ADHD (Table 1). There were no significant differences between groups that received medication versus placebo first (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study population characteristics and demographics

| Intent-To-Treat | Completers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Randomized (n=26) | Non-Completer (n=6) | Completer (n=20) | p-value* | Medication First (n=10) | Placebo First (n=10) | p-value* | |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Females, n (%) | 6 (23.1%) | 1 (16.7%) | 5 (25.0%) | 1.0 | 1 (10.0%) | 4 (40.0%) | 0.30 |

| Caucasians, n (%) | 19 (73.1%) | 3 (50.0%) | 16 (80.0%) | 0.29 | 8 (80.0%) | 8 (80.0%) | 1.0 |

| Household Income at least $70,000, n (%) | 9 (34.6%) | 2 (33.3%) | 7 (35.0%) | 1.0 | 4 (40.0%) | 3 (30.0%) | 1.0 |

| Mother Graduated College, n (%) | 8 (30.8%) | 2 (33.3%) | 6 (30.0%) | 1.0 | 4 (40.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0.63 |

| CT Scan Abnormal, n (%) | 25 (96.2%) | 6 (100%) | 19 (95.0%) | 1.0 | 9 (90.0%) | 10 (100%) | 1.0 |

| Severe TBI, n (%) | 8 (30.8%) | 2 (33.3%) | 6 (30.0%) | 1.0 | 4 (40.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0.63 |

| GCS, Mean (SD)# | 11.9 (4.2) | 10.7 (4.6) | 12.4 (4.1) | 0.45 | 11.6 (4.1) | 13.2 (4.2) | 0.42 |

| Age at Baseline, mean (SD) | 11.5 (2.8) | 12.1 (2.7) | 11.3 (2.8) | 0.57 | 10.9 (2.9) | 11.7 (2.7) | 0.52 |

| Age at Injury, mean (SD) | 6.3 (4.1) | 6.9 (3.8) | 6.1 (4.3) | 0.68 | 5.7 (5.2) | 6.5 (3.5) | 0.70 |

| Time Since Injury at Baseline, mean (SD) | 5.2 (3.8) | 5.2 (4.2) | 5.2 (3.8) | 1.0 | 5.2 (4.2) | 5.3 (3.7) | 0.97 |

| Pre-injury ADHD diagnosis status, n (%) | |||||||

| No Pre-Injury Diagnosis | 12 (46.2%) | 4 (66.7%) | 8 (40.0%) | - | 2 (20.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | - |

| Pre-Injury Inattentive | 3 (11.5%) | 1 (16.6%) | 2 (10.0%) | - | 1 (10.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | - |

| Pre-Injury Hyperactive | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | - | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| Pre-Injury Combined | 3 (11.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | - | 2 (20.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | - |

| Too Young at time of injury to determine Preinjury Diagnosis | 8 (30.8%) | 1 (16.6%) | 7 (35.0%) | 0.58** | 5 (50.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0.34** |

| Baseline ADHD diagnosis status, n (%) | |||||||

| Inattentive | 18 (69.2%) | 4 (66.7%) | 14 (70.0%) | - | 8 (80.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | - |

| Hyperactive | 2 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10.0%) | - | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | - |

| Combined | 6 (23.1%) | 2 (33.3%) | 4 (20.0%) | 0.78** | 2 (20.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0.52** |

| Baseline comorbidity status, n (%) | |||||||

| Oppositional Defiant | 7 (27.0%) | 1 (16.7%) | 6 (30%) | 1.0 | 4 (40%) | 2 (20%) | .63 |

| Disorder (ODD) Conduct Disorder (CD) |

1 (3.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5%) | 1.0 | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 1.0 |

| Anxiety/Depression | 2 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10%) | 1.0 | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (20%) | .47 |

| Baseline measures, mean (SD) | |||||||

| Vanderbilt Parent TSS (mean per item) | 1.9 (0.5) | 2.1 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.4) | 0.36 | 1.9 (0.3) | 1.7 (0.5) | 0.47 |

| Vanderbilt Parent Hyperactive (mean per item) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.6 (1.1) | 1.4 (0.6) | 0.70 | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.7) | 0.94 |

| Vanderbilt Parent Inattentive (mean per item) | 2.2 (0.5) | 2.5 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.5) | 0.13 | 2.3 (0.4) | 2.0 (0.5) | 0.13 |

| Vanderbilt Self TSS$ (mean per item) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.4) | 0.15 | 1.2 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.21 |

| Vanderbilt Self Hyperactive$ (mean per item) | 1.0 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.4) | 0.88 | 1.2 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.26 |

| Vanderbilt Self Inattentive$ (mean per item) | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.6) | 0.03 | 1.3 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.6) | 0.35 |

| FAD General Functioning | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.5) | 0.40 | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.5) | 0.39 |

| WASI-IQ@ | 95.2 (15.4) | 89.8 (20.4) | 96.6 (14.2) | 0.52 | 97.7 (17.3) | 95.4 (11.0) | 0.73 |

| Baseline vital signs, mean (SD) | |||||||

| Heart Rate | 80.4 (12.6) | 90.8 (11.1) | 77.3 (11.4) | 0.03 | 77.5 (15.8) | 77.0 (5.0) | 0.93 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 117.4 (12.2) | 119.7 (12.3) | 116.7 (12.4) | 0.62 | 116.5 (13.4) | 116.9 (12.0) | 0.94 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 63.9 (7.1) | 61.5 (5.8) | 64.6 (7.4) | 0.31 | 64.3 (6.7) | 64.9 (8.3) | 0.86 |

| Respirations Per Min | 18.3 (3.2) | 16.5 (4.5) | 18.9 (2.7) | 0.27 | 17.9 (3.2) | 19.8 (1.7) | 0.12 |

| Weight (kg) | 44.7 (12.8) | 42.2 (10.5) | 45.4 (13.5) | 0.55 | 40.4 (13.1) | 50.4 (12.6) | 0.10 |

ADHD=Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, CT = Computerized Tomography, FAD = Family Assessment Device, GCS = Glasgow Coma Score, TBI = Traumatic Brain Injury, TSS = total symptom score, WASI-IQ = Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence

N for randomized, non-completers, completers, medication-first, and placebo-first groups are 23, 6, 17, 9, 8, respectively. GCS not available for 3 individuals.

N’s for randomized, non-completers, completers, medication-first, and placebo-first groups are 13, 4, 9, 4, 5, respectively, Self-reports n’s are lower as only participants 11 years and older at time of enrollment completed self-report measures

N’s for randomized, non-completers, completers, medication-first, and placebo-first groups are 25, 5, 20, 10, 10. One non-completer decline to complete WASIFSIQ.

Based on t-test. Wilcoxon concurred except for two significant results as noted.

Distribution Based on Fisher’s Exact Test.

Outcomes

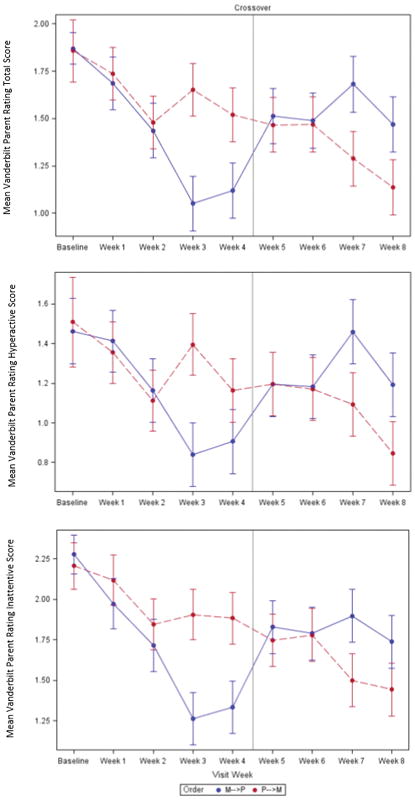

VAPRS TSS during the optimal dose week of the medication condition were lower than during the optimal dose week of the placebo condition (p=.022, Effect size = .59; see Figure 3) after controlling for baseline scores, period (i.e., first or second four weeks), and the interaction of treatment by period. This effect size correlates to an approximate mean change from baseline of 12.5 points on the TSS, with a 10–15 point changed considered clinically meaningful.45 Similar effects were observed for the hyperactive (p=.017, Effect size = .62) and inattentive (p=.018, Effect size .42) subscales (Figure 3). Preinjury ADHD diagnosis status was not associated with a differential medication response (p=.53). The mean methylphenidate dose at each visit was 18 mg (.43 mg/kg/day) at week 1, 35.6 mg (.86 mg/kg/day) at week 2, 51.3 mg (1.25 mg/kg/day) at week 3, and 40.5 mg (1.00 mg/kg/day) at week 4—the optimal dose week (Table 2). There were no differences on the Vanderbilt self-report TSS for the optimal dose visits (p=.15, effect size = .62).

Figure 3. Vanderbilt outcomes.

Graphs depicting mean ratings for Vanderbilt Parent Rating Scale Total Symptom Score (VAPRS TSS) and hyperactive and inattentive subscale items. The graph shows scores at the baseline visit, does-titration visits (weeks 1–3, and 5–7), and primary endpoints (week 4 and 8). Analyses included outcomes for the primary endpoints only. For the VAPRS TSS model (p=.022, t-value=2.52, effect size=.59), the placebo condition estimate was 1.47 with a standard error of .11 and medication condition estimate was 1.10 with standard error of .11. For the hyperactive symptom score model (p=.017, t-value=2.63, effect size=.62), the placebo condition estimate was 1.14 with a standard error of .11 and medication condition estimate was .84 with standard error of .11. For the inattentive symptom score model (p=.018, t-value = 2.48, effect size=.42), the placebo condition estimate was 1.79 with a standard error of .12 and medication condition estimate was 1.37 with standard error of .12. M=medication and P=Placebo condition.

Table 2.

Dosage, vitals, and side effects during medication and placebo conditions

| Medication | Placebo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Week | Week | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|

| ||||||||

| N=21 | N=20 | N=20 | N=20 | N=21 | N=21 | N=21 | N=20 | |

| Dosage, mean (SD)* | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Milligrams | 18.0 (0.0) | 35.6 (2.0) | 51.3 (8.8) | 40.5 (14.2) | 18.0 (0.0) | 35.6 (2.0) | 52.3 (5.4) | 35.6 (13.2) |

| Milligrams per Kilogram | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.5) |

|

| ||||||||

| Vitals, mean (SD): | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Heart Rate | 79.7 (12.7) | 83.1 (13.7) | 81.1 (11) | 84.4 (14.6) | 82.5 (14.7) | 82.6 (13.2) | 82.3 (15.7) | 81.4 (14.4) |

| Systolic blood pressure** | 113 (11.2) | 113.5 (10.2) | 110.4 (11.1) | 118.1 (9.1) | 113.3 (11.8) | 115.5 (12.5) | 112.6 (7.2) | 112.5 (10.2) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 63.1 (7.1) | 65.1 (8.9) | 62.9 (8.3) | 65.2 (6.5) | 63.6 (8.1) | 63.0 (6.7) | 62.7 (7.2) | 63.1 (9.4) |

| Respirations Per Minute | 19.8 (3.3) | 19.4 (3.0) | 19.6 (2.4) | 20.1 (4.4) | 20.2 (3.6) | 19.0 (3.1) | 19.0 (3.2) | 19.7 (2.9) |

| Weight (kg)** | 45.3 (12.9) | 44.7 (13.2) | 44.7 (13.3) | 44.6 (13.5) | 45.6 (12.9) | 45.8 (13.1) | 45.7 (13.1) | 45.7 (13.2) |

|

| ||||||||

| Side Effects, mean (SD) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Change in Appetite** | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.4) |

| Extreme Sadness | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.2) |

| Headache** | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.4) |

| Irritability | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.6) |

| Listless | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.1 (0.3) |

| Picking At | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.6) |

| Repetitive Movements | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Sees/Hears Things | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Shaky | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.4) |

| Socially Withdrawn | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.1 (0.2) |

| Stomachache | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Suicidal/Homicidal Ideations | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.2) |

| Trouble Sleeping | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.5) |

Because the study was done in a masked fashion, the presumed mg and m/kg data are reported for the placebo condition; however, no medications were received during the placebo condition

Systolic BP for Fourth Week, p-value = 0.042, Weight Second, Third, Fourth Weeks, p-values < 0.001; Change in Appetite Second and Third Weeks, p-values = 0.028 and 0.021, Headache First Week, p-value = 0.030

Side effects and adverse events

Compared to the placebo condition, the medication condition was associated with lower weight at the second, third, and fourth week (all p’s<.0001), an increased systolic blood pressure for the fourth week (p=.04), a decrease in reported headache problems during the first week (p=.03), and reported changes in appetite for the second and third weeks (p=.03 and p=.02) (Table 2). Overall, the methylphenidate condition was associated with weight loss (~ 1 kg), increased systolic blood pressure (~3–6 point increase), and mild reported changes in appetite versus the placebo condition. At the last visit, suicidal ideation was reported by one participant while on placebo.

Discussion

Using a double-masked, placebo controlled, upward titration, cross-over clinical trial design, this study supports the efficacy of methylphenidate for management of SADHD in children an average five years after moderate to severe TBI. Effects were in the clinically meaningful range when compared to research within ADHD populations (i.e., non-TBI populations) that indicates a change between 10 and 15 points on symptom score ratings is associated with a clinically meaningful change; however, depending on initial severity of symptoms, larger changes could be associated with even greater clinical improvements.45 The mean optimal dose was approximately one mg per kilogram. Changes in appetite, weight loss, and increased systolic blood pressure were associated with the medication compared to placebo condition. Future research is needed to identify those most likely to benefit from stimulant medication treatment.

Two prior randomized trials of stimulant medications for attention problems after pediatric TBI yielded mixed results.17,18 Both studies used a placebo controlled, cross-over design, but one consisted of four days of treatment with immediate release methylphenidate while the other consisted of two weeks of treatment with immediate release methylphenidate.17,18 The former study did not find differences between medication and placebo groups17 while the latter demonstrated medication-related improvement on all behavioral and lab-based tasks.18 In an aggregate n-of-1 trials study of two weeks of stimulant medications (methylphenidate or dexamphetamine) versus placebo, the authors found improvement in attention behaviors and executive function; however, only five participants completed the trial.19 In addition, in an open-label trial in twenty participants receiving 10 mg of immediate release methylphenidate three times per day for 8 weeks, methylphenidate was well-tolerated and there was improvement on behavioral rating scales.20 The mixed results from these prior studies may be related to sample size limitations, absence of placebo comparison, failure to use ADHD diagnostic criteria as inclusion criteria, lack of dose optimization, differences in duration of medication treatment, variation in short versus sustained release medication, wide time since injury range, and wide range of injury severities.

The current study is the largest randomized clinical trial reported to date and used an upward dose titration in combination with a cross-over design to identify an optimal dose. The average optimal dose of one mg/kg was higher than doses used in prior studies in pediatric TBI populations, but similar to optimal doses reported in primary ADHD populations.39,46 Unlike prior pediatric TBI studies, this trial used long-acting methylphenidate and employed a structured psychiatric interview to determine ADHD status. Use of the structured interview may have reduced heterogeneity by focusing the study on participants with specific attention-related behavior problems. Effect sizes were in the moderate range (Cohen’s d of ~.6), which is slightly lower than effect sizes (Cohen’s d of ~1) reported among children with primary ADHD47, but consistent with effect sizes in adult TBI populations treated with stimulant mediations for attention problems.40

Clinically, it is important to consider the possibility of a placebo effect. In this clinical trial there was a potential placebo effect when participants were on lower doses; therefore, as a placebo effect may be a reason for initial improvement, continued monitoring of symptom scores over time is likely warranted. In addition, because a minimum for a clinically meaningful change is believed to be a 10–15 point improvement on total attention symptom ratings45, in the context of initial improvement that is below this threshold, it seems reasonable to titrate medications to higher doses as tolerated to reach this clinically important change threshold.

Because several different stimulant medications are used for ADHD, it would be important to also understand their effects on secondary attention problems after brain injury. In typical ADHD populations, across stimulant classes there are similar effects;47,48 however, it is unclear if this relation is consistent for those with attention problems after brain injury. Furthermore, the role of non-stimulant medications for management of attention problems after TBI in children is unclear. Within typical ADHD populations, non-stimulant medications have demonstrated significant but smaller effects than stimulant medications.47,49 Comparative effectiveness studies among stimulant and non-stimulant related medications in brain injury populations would help to inform which types and/or classes of medications might be most beneficial for treatment of SADHD following pediatric TBI. Combination medication and/or behavioral and metacognitive-based treatments should also be evaluated. In typical ADHD 47,50 and adult TBI51 populations, combination therapies appear to enhance patient outcomes. Although several cognitive and attention training interventions were previously evaluated in pediatric TBI populations52–59, studies evaluating the combination of medication and non-medication interventions are lacking.21

In adult TBI and populations of children with ADHD, neural mechanisms of stimulants are being explored.60,61 However, the neural mechanism by which stimulants improve attention problems after pediatric brain injury is unclear. Better characterization of the neural mechanisms of attention problems after TBI in children and neural targets of stimulant treatments would potentially provide a more objective marker of medication response.

Limitations

This study has several limitations to consider when interpreting findings. The study focused on proxy and self-report of behaviors. Although primary caregivers or guardians who had the most contact with the child completed the proxy reports, we do not have specific information on how many hours per day they spent with the child. The study does not account for teacher reports of behavior, which may differ from parent report.62 Attempts were made to collect teacher input, but difficulty engaging teachers resulted in substantial missing data. Also, approximately one-third of the participants completed study visits over the summer and visits often overlapped with school holidays (e.g., spring break, winter break); thus, teacher data could not be obtained reliably during these periods. It will be important to also characterize the effects of stimulant mediations on neuropsychological measures of attention and examine associations between neurocognitive performance and functional outcomes. The study population consisted of approximately 75% males, 75% Whites, and primarily individuals with moderate injuries with a mean age of injury of approximately six years and time since injury at enrollment of approximately five years; therefore, findings should be generalized with caution to populations with other characteristics.

Conclusion

Findings from this double-masked, placebo controlled, upward titration, cross-over clinical trial support the use of long-acting methylphenidate for management of attention problems in the long term after pediatric brain injury. Due to the high incidence of brain injury in children and significant impact of attention problems on functioning, larger trials of stimulant medications, including comparative effectiveness and combination medication and non-medication interventions, are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) grant K23HD074683 and in part, by the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1 TR001425 and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research, formerly known as the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (grant number 90RT5004). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other supporting agencies. No competing financial interests exist.

Abbreviations

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- ADHD

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- SADHD

Secondary Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- GCS

Glasgow Coma Scale

- VADPRS

Vanderbilt Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Parent Diagnostic Rating Scale

- K-SADS-P/L

Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School–age Children-Present and Lifetime

- FAD-GF

McMaster Family Assessment Device 12-item General Functioning Scale

- WASI

Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence

- TSS

Total Symptom Score

- PSERS

Pittsburgh Side Effects Rating Scale

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: All authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Trial Registration: NCT01933217

References

- 1.Maas AI, Stocchetti N, Bullock R. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(8):728–741. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Styrke J, Stalnacke BM, Sojka P, Bjornstig U. Traumatic brain injuries in a well-defined population: epidemiological aspects and severity. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(9):1425–1436. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tagliaferri F, Compagnone C, Korsic M, Servadei F, Kraus J. A systematic review of brain injury epidemiology in Europe. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006;148(3):255–268. doi: 10.1007/s00701-005-0651-y. discussion 268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langlois J, Rutland-Brown W, Thomas K. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Servicies, CDC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faul M, Xu L, Wald M, Coronado V. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: emergency department visits, hospitalizations and deaths 2002–2006. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2010. [Accessed September 9, 2013]. http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/blue_book.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor CA, Bell JM, JBM, Xu L. Traumatic brain injury–related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths — United States, 2007 and 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(9):1–18. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6609a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babikian T, Merkley T, Savage RC, Giza CC, Levin H. Chronic aspects of pediatric traumatic brain injury: Review of the literature. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32(23):1849–1860. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.3971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Max JE, Smith WL, Jr, Sato Y, et al. Traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents: psychiatric disorders in the first three months. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(1):94–102. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199701000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Max JE, Lindgren SD, Robin DA, et al. Traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents: psychiatric disorders in the second three months. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185(6):394–401. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199706000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Max JE, Schachar RJ, Levin HS, et al. Predictors of secondary attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents 6 to 24 months after traumatic brain injury. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(10):1041–1049. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000173292.05817.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Max JE, Lansing AE, Koele SL, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents following traumatic brain injury. Dev Neuropsychol. 2004;25(1–2):159–177. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2004.9651926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levin H, Hanten G, Max J, et al. Symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder following traumatic brain injury in children. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics : JDBP. 2007;28(2):108–118. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000267559.26576.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerring JP, Brady KD, Chen A, et al. Premorbid prevalence of ADHD and development of secondary ADHD after closed head injury. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(6):647–654. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199806000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder SeCoQI, Management. ADHD: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1007–1022. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neurobehavioral Guidelines Working G. Warden DL, Gordon B, et al. Guidelines for the pharmacologic treatment of neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23(10):1468–1501. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pangilinan PH, Giacoletti-Argento A, Shellhaas R, Hurvitz EA, Hornyak JE. Neuropharmacology in pediatric brain injury: a review. PM R. 2010;2(12):1127–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams SE, Ris MD, Ayyangar R, Schefft BK, Berch D. Recovery in pediatric brain injury: is psychostimulant medication beneficial? J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1998;13(3):73–81. doi: 10.1097/00001199-199806000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahalick DM, Carmel PW, Greenberg JP, et al. Psychopharmacologic treatment of acquired attention disorders in children with brain injury. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1998;29(3):121–126. doi: 10.1159/000028705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nikles CJ, Mitchell GK, Del Mar CB, Clavarino A, McNairn N. An n-of-1 trial service in clinical practice: testing the effectiveness of stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):2040–2046. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ekinci O, Direk MC, Gunes S, et al. Short-term efficacy and tolerability of methylphenidate in children with traumatic brain injury and attention problems. Brain Dev. 2017;39(4):327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Backeljauw B, Kurowski BG. Interventions for Attention Problems After Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: What Is the Evidence? PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hornyak JE, Nelson VS, Hurvitz EA. The use of methylphenidate in paediatric traumatic brain injury. Pediatr Rehabil. 1997;1(1):15–17. doi: 10.3109/17518429709060937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2(7872):81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolraich ML, Lambert W, Doffing MA, Bickman L, Simmons T, Worley K. Psychometric properties of the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic parent rating scale in a referred population. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2003;28(8):559–567. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor HG, Yeates KO, Wade SL, Drotar D, Klein SK, Stancin T. Influences on first-year recovery from traumatic brain injury in children. Neuropsychology. 1999;13(1):76–89. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.13.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCauley SR, Wilde EA, Anderson VA, et al. Recommendations for the use of common outcome measures in pediatric traumatic brain injury research. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(4):678–705. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller IW, Bishop DS, Epstein NB, Keitner GI. The Mcmaster Family Assessment Device - Reliability and Validity. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1985;11(4):345–356. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeates KO, Swift E, Taylor HG, et al. Short- and long-term social outcomes following pediatric traumatic brain injury. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS. 2004;10(3):412–426. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704103093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wechsler D. Weschler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. New York, NY: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolraich ML, Feurer ID, Hannah JN, Baumgaertel A, Pinnock TY. Obtaining systematic teacher reports of disruptive behavior disorders utilizing DSM-IV. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 1998;26(2):141–152. doi: 10.1023/a:1022673906401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Becker SP, Langberg JM, Vaughn AJ, Epstein JN. Clinical utility of the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic parent rating scale comorbidity screening scales. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics : JDBP. 2012;33(3):221–228. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318245615b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pelham W. Pharmacotherapy for children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology Review. 1993;22(2):199–227. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spencer TJ, Greenbaum M, Ginsberg LD, Murphy WR. Safety and effectiveness of coadministration of guanfacine extended release and psychostimulants in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology. 2009;19(5):501–510. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenhill LL, Abikoff HB, Arnold LE, et al. Medication treatment strategies in the MTA Study: relevance to clinicians and researchers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(10):1304–1313. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swanson JM, Kraemer HC, Hinshaw SP, et al. Clinical relevance of the primary findings of the MTA: success rates based on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms at the end of treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(2):168–179. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200102000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Froehlich TE, Epstein JN, Nick TG, et al. Pharmacogenetic predictors of methylphenidate dose-response in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(11):1129–1139.e1122. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DuPaul GJ, Reid R, Anastopoulos AD, Lambert MC, Watkins MW, Power TJ. Parent and teacher ratings of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms: Factor structure and normative data. Psychol Assessment. 2016;28(2):214–225. doi: 10.1037/pas0000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolraich ML, Greenhill LL, Pelham W, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of oros methylphenidate once a day in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2001;108(4):883–892. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whyte J, Hart T, Vaccaro M, et al. Effects of methylphenidate on attention deficits after traumatic brain injury: a multidimensional, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;83(6):401–420. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000128789.75375.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cnaan A, Laird NM, Slasor P. Using the general linear mixed model to analyse unbalanced repeated measures and longitudinal data. Statistics in Medicine. 1997;16(20):2349–2380. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971030)16:20<2349::aid-sim667>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: A review. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2(3):109–112. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.83221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Max JE, Schachar RJ, Levin HS, et al. Predictors of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder within 6 months after pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(10):1032–1040. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000173293.05817.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol. 2013;4:863. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodman D, Faraone SV, Adler LA, Dirks B, Hamdani M, Weisler R. Interpreting ADHD rating scale scores: Linking ADHD rating scale scores and CGI levels in two randomized controlled trials of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in ADHD. Primary Psychiatry. 2010;17(3):44–52. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Burrows-Maclean L, et al. Once-a-day Concerta methylphenidate versus three-times-daily methylphenidate in laboratory and natural settings. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):E105. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity D, Steering Committee on Quality I Management et al. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1007–1022. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown RT, Amler RW, Freeman WS, et al. Treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: overview of the evidence. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):e749–757. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gayleard JL, Mychailyszyn MP. Atomoxetine treatment for children and adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): a comprehensive meta-analysis of outcomes on parent-rated core symptomatology. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s12402-017-0216-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rajeh A, Amanullah S, Shivakumar K, Cole J. Interventions in ADHD: A comparative review of stimulant medications and behavioral therapies. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;25:131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McDonald BC, Flashman LA, Arciniegas DB, et al. Methylphenidate and Memory and Attention Adaptation Training for Persistent Cognitive Symptoms after Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017 doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van’t Hooft I, Andersson K, Bergman B, Sejersen T, Von Wendt L, Bartfai A. Sustained favorable effects of cognitive training in children with acquired brain injuries. NeuroRehabilitation. 2007;22(2):109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galbiati S, Recla M, Pastore V, et al. Attention remediation following traumatic brain injury in childhood and adolescence. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(1):40–49. doi: 10.1037/a0013409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Catroppa C, Anderson V, Muscara F. Rehabilitation of executive skills post-childhood traumatic brain injury (TBI): A pilot intervention study. Developmental Neurorehabilitation. 2009;12(5):361–369. doi: 10.3109/17518420903087335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sjo NM, Spellerberg S, Weidner S, Kihlgren M. Training of attention and memory deficits in children with acquired brain injury. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99(2):230–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hooft IV, Andersson K, Bergman B, Sejersen T, Von Wendt L, Bartfai A. Beneficial effect from a cognitive training programme on children with acquired brain injuries demonstrated in a controlled study. Brain injury : [BI] 2005;19(7):511–518. doi: 10.1080/02699050400025224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ho J, Epps A, Parry L, Poole M, Lah S. Rehabilitation of everyday memory deficits in paediatric brain injury: self-instruction and diary training. Neuropsychological rehabilitation. 2011;21(2):183–207. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2010.547345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Kloet AJ, Berger MA, Verhoeven IM, van Stein Callenfels K, Vlieland TP. Gaming supports youth with acquired brain injury? A pilot study. Brain injury : [BI] 2012;26(7–8):1021–1029. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2012.654592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas-Stonell N, Johnson P, Schuller R, Jutai J. Evaluation of a computer-based program for remediation of cognitive-communication skills. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 1994;9(4):25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim J, Whyte J, Patel S, et al. Methylphenidate modulates sustained attention and cortical activation in survivors of traumatic brain injury: a perfusion fMRI study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;222(1):47–57. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2622-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoo JH, Kim D, Choi J, Jeong B. Treatment effect of methylphenidate on intrinsic functional brain network in medication-naive ADHD children: A multivariate analysis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s11682-017-9713-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lavigne JV, Dulcan MK, LeBailly SA, Binns HJ. Can parent reports serve as a proxy for teacher ratings in medication management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder? Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics : JDBP. 2012;33(4):336–342. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31824afea1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]