Abstract

Child development refers to the continuous but predictably sequential biological, psychological and emotional changes that occur in human beings between birth and the end of adolescence. Developmental surveillance should be incorporated into every child visit. Parents play an important role in the child’s developmental assessment. The primary care physician should educate and encourage parents to use the developmental checklist in the health booklet to monitor their child’s development. Further evaluation is necessary when developmental delay is identified. This article aimed to highlight the normal child developmental assessment as well as to provide suggestions for screening tools and questions to be used within the primary care setting.

Keywords: child developmental, developmental screening tools, primary care, surveillance

Felicia’s parents brought their 12-month-old girl to your clinic for routine vaccinations. They expressed concern that she was not walking yet and reported that she had been able to sit independently at eight months and crawl at nine months. Felicia could pull herself up to stand while holding on to the bed rails. Her birth and medical history were unremarkable. She looked active and her physical examination results were within normal limits.

WHAT IS CHILD DEVELOPMENT?

Child development refers to the continuous but predictably sequential biological, psychological and emotional changes that occur in human beings between birth and the end of adolescence. The sequence of development is the same for all children and can be described in terms of developmental milestones. As children develop at different rates, which are determined by a complex interplay of environmental and genetic factors,(1) the age of attainment for each milestone ranges widely. It is essential to not only be aware of the median age of attainment of the milestone (i.e. the age at which half of the standard population achieves the milestone) but the limit age as well (i.e. the upper age limit at which the particular milestone should have been achieved). This would help to guide the clinician on whether to reassure the parent/caregiver, monitor the child’s development closely or refer the child to a specialist for a detailed assessment and further management. It is also essential for the clinician to assess the quality of the skill rather than taking note of the age at which the milestone was achieved. For example, a child may have acquired sufficient language skills to allow him to speak in phrases, but may be unskilled in using language for conversational purposes.

The basic architecture of the brain is constructed by an ongoing process that begins before birth and continues into adulthood. Maximum brain development occurs within the first three years of a child’s life and is hence called the early developmental phase. It is therefore essential to recommend that parents engage in appropriate stimulation activities with their children, starting from the newborn period.

HOW RELEVANT IS THIS TO MY PRACTICE?

In Singapore, every well child is scheduled to be seen at specific ages by a trained nurse or a doctor for a developmental screening, according to the child health surveillance programme at the polyclinics and in line with practice guidelines endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics.(2) The child’s health booklet provides guidelines on the time points when developmental screening should occur, as part of six recommended touch points between the ages of one month and 4–6 years. The developmental checklist in the health booklet is based on the Denver Developmental Screening Test, which is the only tool standardised for the local population (DDST-Singapore).(3) As the cut-offs indicate 90th percentile norms, if a child is unable to achieve a milestone for the stated age (indicating that 90% of the same age population is able to achieve it), a more in-depth assessment and a low threshold for further specialist referral are required. The parents and professionals working with the child are responsible for updating the developmental checklist, which provides guidelines to monitor the child’s development.

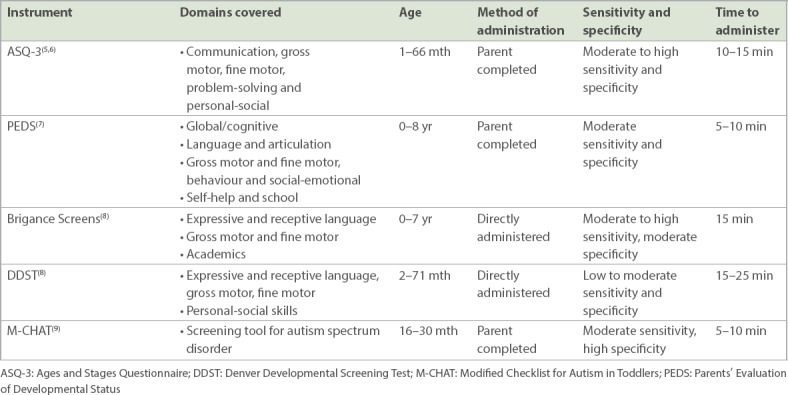

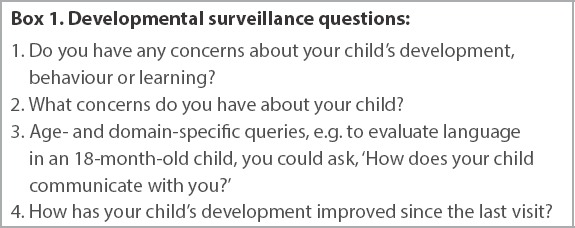

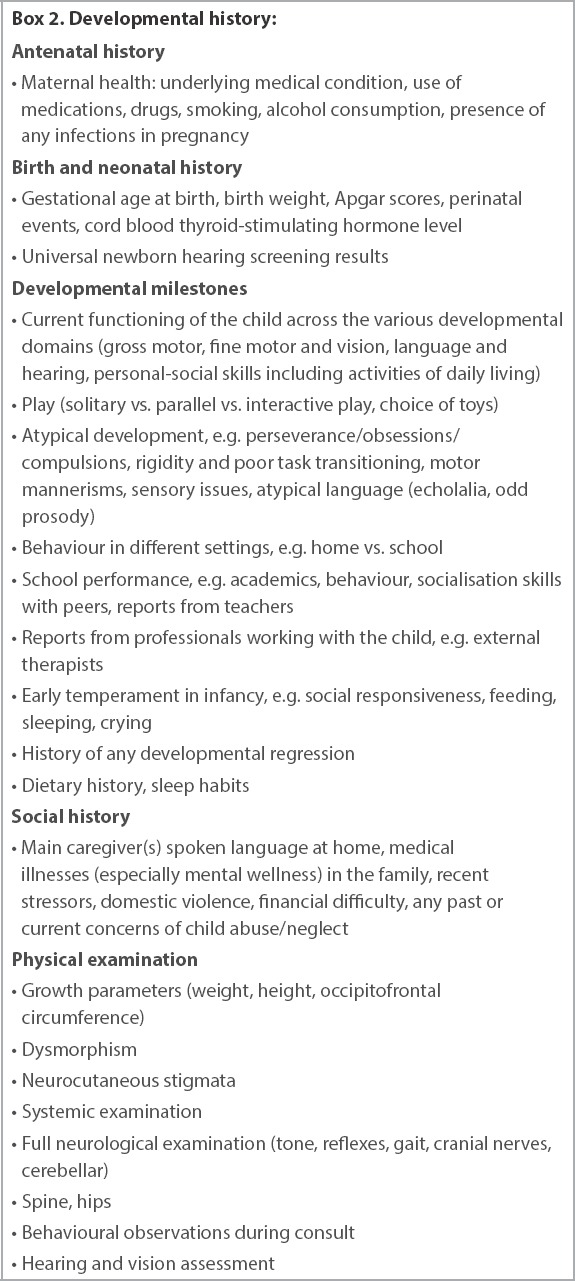

It is common for children to attend fewer developmental screening appointments after the age of 18 months. Hence, it is essential that primary care physicians conduct developmental surveillance, which is an informal yet structured monitoring of developmental status over time. The components of developmental surveillance include eliciting and addressing parents’ concerns about their child’s development (Box 1); obtaining a developmental history (Box 2); making precise observations of the child; identifying risk and protective factors; and lastly, making effective documentation of the obtained history and observation of the child.(2,4) Any concerns raised during surveillance should be promptly addressed with standardised developmental screening tools, which help to identify the child’s risk of developmental delay. Developmental screening questionnaires that are commonly used in our local setting are listed in Table I. The next article in this two-part series will cover developmental delays and management.

Table I.

Developmental screening questionnaires.

Box 1.

Developmental surveillance questions:

Box 2.

Developmental history:

When the parents or preschool raises concerns about developmental delay, paediatricians and primary care physicians are the first points of contact for parents seeking reassurance or further assessment. Therefore, primary care physicians need to have a systematic approach when evaluating a child for development, including taking a developmental history, conducting a developmental assessment and being aware of the red flags that would warrant further specialist referrals when necessary. In the absence of any concerns, parental anxiety should be allayed. Knowledge of developmental milestones is essential for the primary care physician to be able to provide anticipatory guidance and suggest appropriate activities to the parents or caregivers so that they can facilitate the next stage of development.

COMMON PITFALLS AND CHALLENGES IN ROUTINE PRACTICE

Not all parents take their children to developmental screening assessments after the primary immunisations are completed at 18 months of age. A study conducted in Singapore of parents of children aged 30–47 months indicated that only one in four parents took their child to the 2–3 year developmental monitoring visit.(10) The same study highlighted that only about half of the parents attempted to complete the checklist. Another challenge is the time constraint from implementing developmental surveillance during busy clinics.(11) Success of developmental surveillance depends on continuous monitoring of the child and may not work well for children who receive infrequent care by different professionals. There is also variability in child development knowledge and training among front-line practitioners.(12)

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

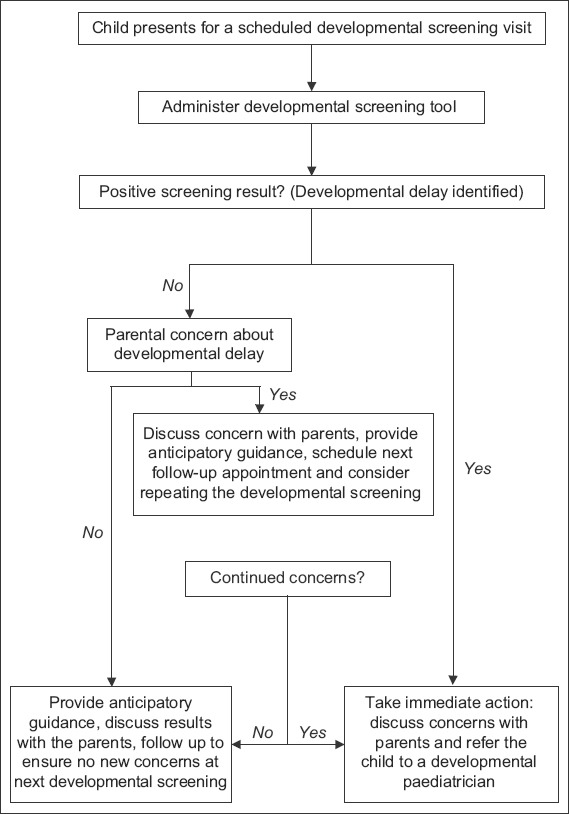

As child stimulation starts at birth, primary care physicians should advise parents on appropriate child stimulation activities at every available opportunity. While the developmental checklist in the baby health booklet can be used to monitor the child’s development, it is brief; hence, there is a need to adopt a standardised screening tool to conduct developmental screening during the vital touch points (Fig. 1).(4,13) Developmental surveillance should also be conducted at every clinic visit. If the developmental surveillance identifies any concerns, the physician should follow up with a developmental screening assessment. Concerns raised through the assessment would warrant further specialist referral as deemed necessary. When development age in any domain is after the median age but still within the 90th percentile, anticipatory guidance on various stimulation methods and activities should be given to the family, along with closer monitoring in the form of a follow-up visit. Parents should be encouraged to monitor their child’s development regularly using the health booklet. Physicians should also be aware of other factors that affect development, such as sleep, diet and family circumstances.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart shows the algorithmic approach to developmental screening.(4) Adapted and modified from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.(13)

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

The role of parents in early childhood stimulation is crucial for child developmental.

Developmental surveillance should be incorporated in every child visit. When a concern is raised, this should be followed up with a developmental screening assessment.

Developmental screening should be performed at specific ages.

Parents and families should be encouraged to use the child’s health booklet.

You conducted a detailed developmental assessment for Felicia and noticed that all developmental milestones were appropriate for her age. Her health booklet revealed no concern during the developmental screening conducted at nine months of age. You reassured her parents that Felicia was developing normally for her age. You explained that most children commence walking at 12 months of age, and that the normal limit for starting to walk was up to the age of 16 months. You advised Felicia’s parents to continue monitoring her development by using the health booklet checklist and arranged a follow-up visit three months later to monitor the progression of her gross motor skills.

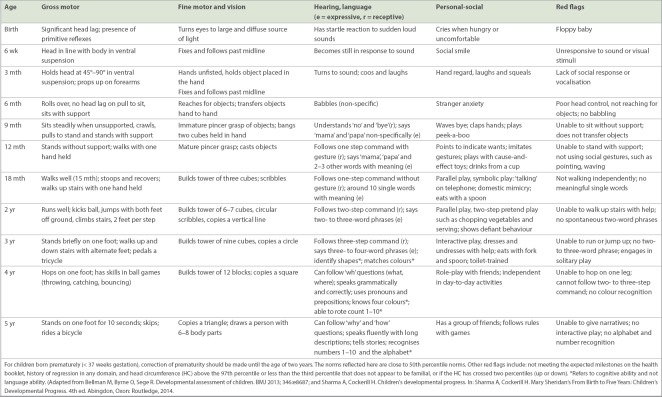

APPENDIX

Normal developmental milestones

REFERENCES

- 1.Champagne FA. Early adversity and developmental outcomes interaction between genetics, epigenetics, and social experiences across the life span. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2010;5:564–74. doi: 10.1177/1745691610383494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Council on Children With Disabilities;Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics;Bright Futures Steering Committee;Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home:an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Paediatrics. 2006;118:405–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim HC, Chan T, Yoong T. Standardisation and adaptation of the Denver Developmental Screening Test (DDST) and Denver II for use in Singapore Children. Singapore Med J. 1994;35:156–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vitrikas K, Savard D, Bucaj M. Developmental delay:when and how to screen. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96:36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton S. Screening for developmental delay:reliable, easy-to-use tools. J FamPract. 2006;55:415–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ages and Stages Questionnaires. Commonly Used Parent-Report Developmental Screening Tools. [Accessed February 14, 2016]. Available at http://agesandstages.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Comparison-Chart1.pdf.

- 7.Kiing JS, Low PS, Chan YH, Neihart M. Interpreting parents'concerns about their children's development with the Parents Evaluation of Developmental Status:culture matters. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33:179–83. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31823f686e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ringwalt S. Developmental Screening and Assessment Instruments with an Emphasis on Social and Emotional Development for Young Children Ages Birth through Five. National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center 2008. [Accessed December 11, 2015]. Available at: http://www.nectac.org/~pdfs/pubs/screening.pdf.

- 9.Koh HC, Lim SH, Chan GJ, et al. The clinical utility of the modified checklist for autism in toddlers with high risk 18-48 month old children in Singapore. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44:405–16. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1880-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koh HC, Ang SK, Kwok J, et al. The utility of developmental checklists in parent-held health records in Singapore. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2016;37:647–56. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rydz D, Shevell M, Majnemer A, Oskoui M. Topical review:developmental screening. J Child Neurol. 2005;20:4–21. doi: 10.1177/08830738050200010201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lian WB, Ho SK, Yeo CL, Ho LY. General practitioners'knowledge on childhood developmental and behavioural disorders. Singapore Med J. 2003;44:397–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Developmental Monitoring and Screening for Health Professionals. [Accessed January 11, 2019]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/childdevelopment/screening-hcp.html .

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.