Rifampin (RIF) plus clarithromycin (CLR) for 8 weeks is now the standard of care for Buruli ulcer (BU) treatment, but CLR may not be an ideal companion for rifamycins due to bidirectional drug-drug interactions. The oxazolidinone linezolid (LZD) was previously shown to be active against Mycobacterium ulcerans infection in mice but has dose- and duration-dependent toxicity in humans.

KEYWORDS: Buruli ulcer, Mycobacterium ulcerans, linezolid, oxazolidinones, sutezolid, tedizolid

ABSTRACT

Rifampin (RIF) plus clarithromycin (CLR) for 8 weeks is now the standard of care for Buruli ulcer (BU) treatment, but CLR may not be an ideal companion for rifamycins due to bidirectional drug-drug interactions. The oxazolidinone linezolid (LZD) was previously shown to be active against Mycobacterium ulcerans infection in mice but has dose- and duration-dependent toxicity in humans. Sutezolid (SZD) and tedizolid (TZD) may be safer than LZD. Here, we evaluated the efficacy of these oxazolidinones in combination with rifampin in a murine BU model. Mice with M. ulcerans-infected footpads received control regimens of RIF plus either streptomycin (STR) or CLR or test regimens of RIF plus either LZD (1 of 2 doses), SZD, or TZD for up to 8 weeks. All combination regimens reduced the swelling and bacterial burden in footpads after two weeks of treatment compared with RIF alone. RIF+SZD was the most active test regimen, while RIF+LZD was also no less active than RIF+CLR. After 4 and 6 weeks of treatment, neither CLR nor the oxazolidinones added significant bactericidal activity to RIF alone. By the end of 8 weeks of treatment, all regimens rendered footpads culture negative. We conclude that SZD and LZD warrant consideration as alternative companion agents to CLR in combination with RIF to treat BU, especially when CLR is contraindicated, intolerable, or unavailable. Further evaluation could prove SZD superior to CLR in this combination.

INTRODUCTION

The treatment of Buruli ulcer (BU) caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans infection has evolved from wide surgical excision of lesions followed by skin grafting to an 8-week course of rifampin (RIF) combined with streptomycin (STR) or, more recently, with clarithromycin (CLR) (1–3). The RIF+CLR regimen is now preferred due to oral administration and the avoidance of ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity (4) associated with STR. Preliminary results of a clinical trial (ClinicalTrials registration no. NCT01659437) indicate that the regimens have equivalent efficacy when administered for 8 weeks (5). However, patients undergoing treatment with CLR may have gastrointestinal complaints (6), and receipt of CLR for longer than 2 weeks may increase the risk of death in those with heart disease (7). RIF also dramatically increases the metabolism of CLR (8–10), which could result in subtherapeutic exposures of CLR, especially when CLR is administered as 500 mg/day. A major objective of BU drug development efforts is to identify more potent regimens with a higher safety/tolerability profile that can shorten treatment duration (2).

Oxazolidinones are potential candidates to replace CLR. Linezolid (LZD), the first marketed member of this drug class, is highly orally bioavailable, less affected by coadministration with RIF, and is no longer patent protected. Ji et al. (12) showed that LZD was active in vitro and in a mouse footpad model of M. ulcerans infection. The MIC90 of LZD was 2.0 µg/ml. At a dose of 100 mg/kg of body weight per day, LZD monotherapy rendered 0% and 30% of mice culture negative after 4 and 8 weeks, respectively. The combination of LZD with RIF (10 mg/kg/day) rendered 90% and 100% of mice culture negative after 4 and 8 weeks of treatment, respectively, a result that could not be distinguished from results with RIF alone or RIF+STR.

LZD is associated with dose- and duration-dependent hematologic and neurologic toxicities (13), although neuropathy only rarely occurs in the first 4 to 8 weeks of treatment. Newer oxazolidinones in development may be safer than LZD. For example, sutezolid (SZD), originally designated PNU-100480, exhibited less hematological toxicity in a phase 1 trial and also may have superior antimycobacterial activity (14). Tedizolid (TZD) is another oxazolidinone licensed for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections that may also be less toxic than LZD at the approved dose (15). To our knowledge, neither SZD nor TZD have been evaluated against M. ulcerans.

In this study, we compared the efficacy of these oxazolidinones, including a reduced dose of LZD, in combination with RIF to that of standard-of-care regimens based on their ability to reduce footpad swelling and bacterial burden in a well-established mouse footpad model. The addition of SZD increased the efficacy of RIF, and the combination of RIF+SZD was comparable in activity to RIF+STR and at least as good as RIF+CLR over the first 2 weeks of treatment. At the dose tested, TZD appeared less effective than SZD or LZD. After 8 weeks, all regimens tested achieved culture negativity. The oxazolidinones SZD and LZD may be effective alternatives to CLR or STR in the treatment of BU.

RESULTS

Dose-ranging activity of oxazolidinones as monotherapy.

An initial evaluation of the dose-ranging activity of SZD and LZD against the nonluminescent 1615 strain was performed in a more acute “kinetic” model of M. ulcerans infection, in which treatment is initiated prior to the onset of footpad swelling when the bacterial burden is increasing exponentially. The scheme of the experiment is presented in Table S1 in the supplemental material. SZD and LZD doses of 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg were compared with RIF doses of 10 mg/kg and CLR doses of 150 and 300 mg/kg. At the start of treatment 5 weeks after inoculating a mean (±SD) of 2.56 ± 0.18 log10 CFU per footpad, the mean CFU count had increased to 3.86 ± 0.45. Footpad swelling became apparent in the vast majority of untreated mice between 8 and 9 weeks postinfection (i.e., 3 and 4 weeks into the treatment period) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and CFU continued to increase before a plateau was reached at mean CFU counts of 6.09 ± 0.23 and 5.88 ± 0.13 at weeks 6 and 8, respectively (see Table S2 and Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). RIF, CLR, and any dose of SZD prevented swelling for the duration of treatment. On the other hand, LZD delayed, but did not prevent, the development of swelling in the majority of mice in a dose-dependent manner, indicating that bacteriostasis was not achieved. These observations were supported by the footpad CFU counts demonstrating that RIF was bactericidal, LZD only approached bacteriostasis at the 100 mg/kg dose, and CLR and SZD were bacteriostatic over the first 4 weeks, while SZD had weak bactericidal activity at doses of 50 to 100 mg/kg during the last 4 weeks of treatment.

Efficacy of rifampin-oxazolidinone combinations.

To evaluate the potential contribution of LZD, SZD, and TZD to RIF-based combination therapy, a more established footpad infection model was used, in which footpad swelling and a plateau in the bacterial burden are achieved prior to the onset of treatment.

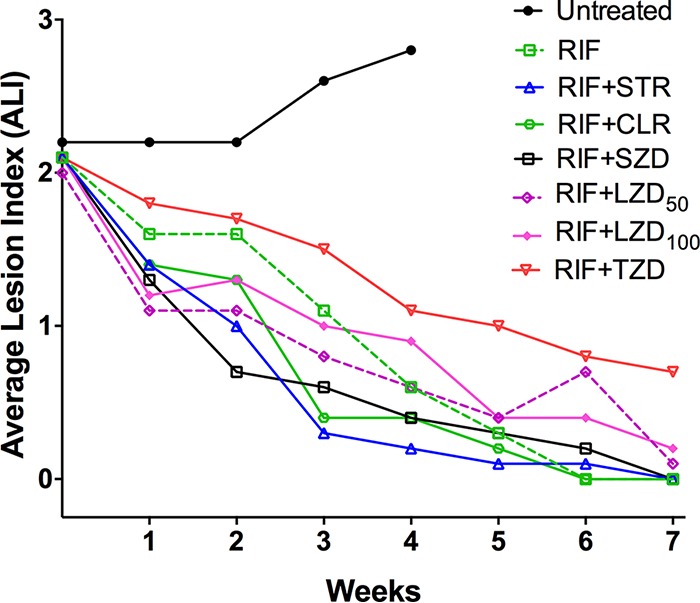

Footpad average lesion index. Footpad swelling was apparent after 4 weeks of infection. By day 0 (D0), the average lesion index (ALI) was 2.1 ± 0.4. Thereafter, the ALI steadily declined in all groups except in the untreated mice in whom it increased to 2.8 ± 0.4 by week 4 (Fig. 1). All treated mice reached an ALI of 0 (i.e., normal appearance by week 6 or week 7), except in the RIF+TZD group, in which some residual swelling (ALI, 0.8 ± 0.4) remained at the end of treatment.

FIG 1.

Treatment with rifampin and companion drugs reduces footpad swelling in M. ulcerans-infected mice.

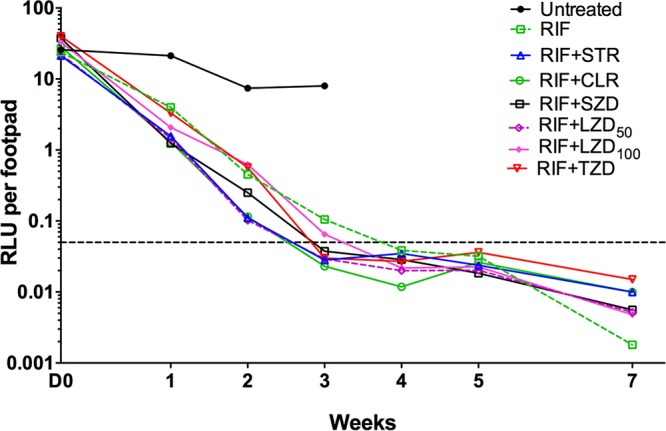

Footpad RLU counts. Untreated mice had increasing RLU counts from the day of infection until D0, after which time the values remained stable or declined slowly (Fig. 2). In contrast, the RLU counts in all treatment groups declined sharply compared with untreated controls and, except for RIF and RIF+TZD groups, all were an order of magnitude lower than controls after 1 week of treatment. By week 2, RLU counts in all treated groups were at least an order of magnitude lower than untreated controls and none could be differentiated from RIF alone. By the end of week 3, all treatment groups except for RIF alone (mean RLU, 0.10 ± 0.11) and combined with LZD at 100 mg/kg (RIF+LZD100) (mean RLU, 0.06 ± 0.05) had mean RLU counts below the background RLU cutoff of 0.05 (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Treatment with rifampin and companion drugs reduces bacterial burden as assessed by footpad relative light unit (RLU) counts in the M. ulcerans-infected mice. The horizontal line indicates background RLU level.

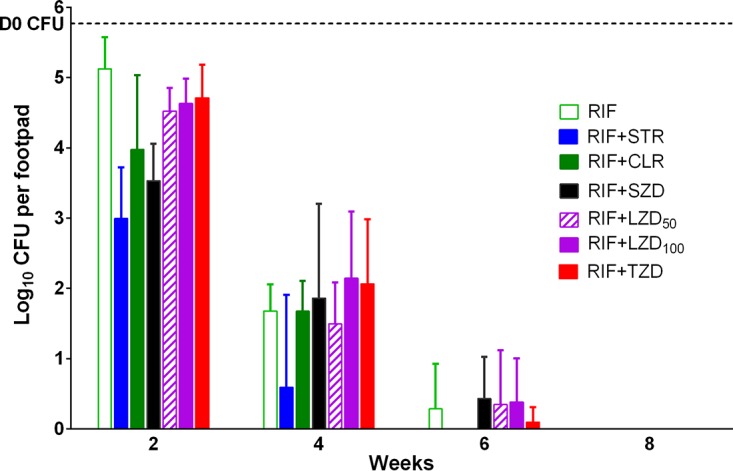

Footpad CFU counts. The mean footpad CFU count (± SD) was 4.09 ± 0.23 log10 on the day after infection (D-38), increased to 4.94 ± 0.12 at 14 days prior to treatment (D-14), and increased further to 5.77 ± 0.60 log10 by D0 (Fig. 3). After 2 weeks of treatment, the mean CFU counts (± SD) declined most rapidly in mice treated with RIF+STR (2.99 ± 0.73), followed by RIF+SZD (3.53 ± 0.53), RIF+CLR (3.98 ± 1.05), RIF+LZD50 (LZD at 50 mg/kg) (4.51 ± 0.33), RIF+LZD100 (4.63 ± 0.35), RIF+TZD (4.71 ± 0.47), and RIF alone (5.13 ± 0.45). Compared with the current all-oral recommended standard of care RIF+CLR (3, 5), treatment with RIF+SZD reduced the CFU counts by an additional half-log, while CFU counts in groups receiving RIF combined with LZD or TZD were at least a half-log higher. None of these differences between combinations were statistically significant. Compared to RIF alone, RIF+SZD was the only oxazolidinone-containing regimen to show significantly (P < 0.01) greater activity, while both RIF+CLR and RIF+STR control regimens were also significantly better (P < 0.05 and P < 0.0001, respectively) than RIF alone. After 4 weeks of treatment, similar trends in CFU counts were seen; RIF+STR produced the lowest mean CFU counts (± SD) (0.59 ± 1.32), followed by RIF+LZD50 (1.50 ± 0.59), RIF alone (1.68 ± 0.38), RIF+CLR (1.68 ± 0.43), RIF+SZD (1.86 ± 1.35), RIF+LZD100 (2.14 ± 0.95), and RIF+TZD (2.06 ± 0.92). Mean CFU counts (± SD) in mice receiving various combinations of RIF with oxazolidinones ranged from 1.50 to 2.06 and were not significantly different from those in mice receiving RIF+CLR (1.68 ± 0.43). By week 6, most footpads were culture negative, including all of those from mice treated with RIF+STR or RIF+CLR, 4 of 5 mice treated with RIF+LZD50 or RIF+TZD, and 3 of 5 mice treated with RIF+LZD100 or RIF+SZD. Again, there were no significant differences between the combination regimens. All footpads in all mice were culture negative at week 8.

FIG 3.

Treatment with rifampin and companion drugs reduces bacterial burden as assessed by footpad colony forming unit (CFU) counts in M. ulcerans-infected mice. The horizontal line represents the CFU burden at the start (D0) of treatment.

DISCUSSION

In the past two decades, considerable progress has occurred in the treatment of BU (2, 16). Initial recommendations involved extensive surgical excision of the lesions. Studies in mouse footpad models identified that regimens containing RIF and an aminoglycoside would be efficacious, and subsequent clinical trials established the effectiveness of 8 weeks of RIF+STR. However, the use of STR has the disadvantages of ototoxicity and the need for injections for 8 weeks (2, 4). As an alternative to STR, the WHO technical advisory group on Buruli ulcer recently recommended an all-oral regimen of RIF+CLR based on results of a series of clinical trials (5). Although RIF+CLR appears effective, it still requires administration for 8 weeks, whereas a shorter regimen would likely enhance treatment completion and reduce utilization of precious health care resources. In addition, CLR is compromised by tolerability concerns and a drug-drug interaction with RIF that significantly reduces CLR exposures (a problem that may worsen if high-dose rifamycin regimens are tested as they are in TB) (8–10, 17, 18), may reduce its effectiveness as a companion agent, and possibly result in acquired RIF resistance. Therefore, new oral companion agents are sought to shorten treatment and/or provide a more effective companion agent to RIF. We sought to determine whether an oxazolidinone might achieve these objectives.

In our study, SZD was the only oxazolidinone that exhibited bactericidal activity as monotherapy in the kinetic model and, like CLR, added activity to RIF alone in a statistically significant manner at week 2 and was not worse than RIF+STR against a more established footpad infection. However, RIF combined with LZD at 50 and 100 g/kg doses producing exposures similar to 600-mg and 1,200-mg daily doses, respectively, in patients had activity that was indistinguishable from RIF+CLR and from each other, while RIF+TZD was numerically worse than all regimens at weeks 2 and 4 by CFU and swelling scores. SZD is currently in clinical development for the treatment of tuberculosis, where it has demonstrated significant early bactericidal activity and reduced hematologic toxicity compared with LZD (14, 19). Therefore, it could represent a promising alternative to CLR. However, additional clinical studies are needed to determine whether an adverse drug-drug interaction with RIF exists before its candidacy for BU treatment regimens could be seriously considered.

LZD has received increasing attention as a second-line drug for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). In fact, it was recently ranked as a group A drug by the WHO, indicating that it should be prioritized for inclusion in the regimen for any MDR-TB patient (20). It is also off patent and should be increasingly available at lower prices. Although we did not find that the addition of LZD significantly improved the activity of RIF alone, the mean CFU counts and swelling grades were numerically lower in either RIF+LZD group than in the RIF alone group during the first 2 weeks. These results suggest that LZD may still play a role in enhancing the bactericidal effect of RIF-containing regimens and in reducing the risk of selecting RIF-resistant mutants. Although LZD carries a risk of dose- and duration-dependent toxicity (13), its neurotoxicity consists primarily of peripheral and occasional optic neuropathies that typically do not manifest before 3 to 4 months of treatment (21) and would not be a major concern for BU treatment. Hematologic toxicity, typically thrombocytopenia or anemia, is reversible and tends to occur after 2 to 4 weeks of treatment. It is trough dependent and is, therefore, less likely to occur with once-daily treatment (22). Importantly we found that the 50-mg/kg dose of LZD was just as effective as the 100-mg/kg dose, indicating that 600 mg daily may be just as effective as 1,200 mg daily in humans. We also found that any additive effect of LZD (as with SZD) was most evident in the first 2 to 4 weeks. Taken together, the results may suggest that LZD 600 mg for 2 to 4 weeks may more-or-less optimize the contribution of LZD to a RIF+LZD regimen and be largely devoid of neurotoxicity and hematologic toxicity.

Tedizolid is marketed for acute bacterial skin and soft tissue infections and, at the approved dose of 200 mg daily, appears to have less hematologic toxicity than LZD 600 mg twice daily (15). However, whether it is less toxic than LZD 600 mg administered once daily remains unknown. Moreover, TZD appeared to be the least effective oxazolidinone in this model.

While we did not find that any oxazolidinone-containing regimen was superior to RIF+CLR, it should be kept in mind that the CLR dose used in our experiments could overrepresent CLR exposures obtained in humans because the induction of CLR metabolism by RIF in mice is likely not as great as what is observed in patients, where CLR exposures are reduced by 70% to 90% (8–10). Thus, the contribution of CLR to the RIF+CLR combination may be overestimated by the 100-mg/kg CLR dose in mice. Moreover, the significance of the RIF-CLR interaction will only increase if higher doses of RIF or rifapentine are evaluated for BU, as they are currently being evaluated for TB (23). Coadministration with RIF also reduces LZD plasma exposures, although to a much more limited extent, and this interaction may actually provide some protection against trough-driven LZD toxicity (24, 25).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

M. ulcerans strains 1059 and 1615, originally obtained from patients in Ghana and Malaysia, respectively, were kindly provided by Pamela Small, University of Tennessee. The 1059 strain was subsequently engineered to be autoluminescent (Mu1059AL) (26, 27), while remaining virulent in mouse footpad models.

Antibiotics.

RIF and STR were purchased from Sigma. CLR was purchased from the Johns Hopkins Hospital pharmacy. LZD, SZD, and TZD were kindly provided by the Global Alliance for TB Drug Development. RIF and CLR were prepared in sterile 0.05% agarose solution, and STR was prepared in sterile water. Oxazolidinones were prepared and formulated for oral administration, as described elsewhere (28).

Mouse infection and treatment.

Female BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories) were inoculated subcutaneously in the right hind footpad with 0.03 ml of a culture suspension. The dose-ranging monotherapy experiment was performed in the kinetic model after infection with the 1615 strain. A frozen culture obtained after passage in mouse footpads was thawed and used for infection. The inoculum was estimated to contain approximately 2.56 log10 CFU of Mu1615 based on the CFU counts performed on Middlebrook 7H11 plates. Treatment began 35 days after infection, before the onset of footpad swelling. Mice were randomized to receive no treatment or monotherapy with RIF, CLR, LZD, or SZD at the doses indicated in Table S1 and treated for 2, 3, 4, 6, or 8 weeks.

The combination therapy experiment used an established footpad infection model in which the treatment began after the onset of swelling, when the peak bacterial burden had already been achieved. The Mu1059AL strain was prepared from freshly harvested footpad suspension of previously infected mice (ALI, 2 to 3). The inoculum was estimated to contain approximately 4.56 log10 CFU. Treatment began 39 days (D0) after infection when the ALI was 2.1 ± 0.4. Mice were randomized to 1 of the 7 treatment regimens and treated for 2, 4, 6, or 8 weeks (Table 1). Control regimens included RIF10+STR150, RIF10+CLR100, or RIF10 alone, where the subscript represents the dose in mg per kg body weight. Test regimens consisted of RIF10+LZD50, RIF10+LZD100, RIF10+SZD50, and RIF10+TZD10.

TABLE 1.

Experimental scheme for the combination therapy experiment

| Drug regimen | No. of mice sacrificed at the following time pointsa

: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-38 | D-14 | D0 | W2 | W4 | W6 | W8 | Total | |

| Control | ||||||||

| Untreated | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 20 | |||

| RIF10 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 20 | |||

| RIF10+STR150 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 20 | |||

| RIF10+CLR100 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 20 | |||

| Test | ||||||||

| RIF10+LZD50 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 20 | |||

| RIF10+LZD100 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 20 | |||

| RIF10+SZD50 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 20 | |||

| RIF10+TZD10 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 20 | |||

| Total | 5 | 5 | 5 | 35 | 40 | 35 | 35 | 160 |

W2, W4, W6, and W8 indicate completion of 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks, respectively, of treatment.

In both experiments, drugs were administered 5 days per week in 0.2 ml by gavage, except for STR, which was administered by subcutaneous injection. Drug doses were chosen based on mean plasma exposures (i.e., area under the concentration-time curve over 24-h postdose) compared with human doses (28–30). All animal procedures were conducted according to relevant national and international guidelines and approved by the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee.

Evaluation of treatment response.

The following three parameters were used to monitor the progress of infection and treatment response in mouse footpads in the combination therapy experiment: (i) the average lesion index (ALI), (ii) relative light unit (RLU) counts, and (iii) CFU counts. The RLU endpoint was not possible in the monotherapy experiment that did not use the luminescent reporter strain. The scoring of the lesion index was described previously (2, 29). Briefly, the presence and the degree of inflammatory swelling of the infected footpad are assessed weekly and scored from 0 (no swelling) to 4 (inflammatory swelling extending to the entire limb). RLU counts in infected footpads were determined in live mice by anesthetizing them with ketamine/xylazine (87.5/12.5 mg/kg, injected intraperitoneally), placing them in a tabletop luminometer (TD 20/20), and measuring the RLU for 4 s (26, 27). Five mice were sacrificed for CFU counts on the day after infection and at D0 to determine the infectious dose and the pretreatment CFU counts, respectively. The response to treatment was determined by sacrificing 5 mice from each treatment group at the time points designated in Table S1 and Table 1 and harvesting the footpads after thorough disinfection with 70% alcohol swabs. Footpad tissue was then homogenized by fine mincing and suspended in 2.5 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Ten-fold serial dilutions were plated in 0.5-ml aliquots onto selective Middlebrook 7H11 plates and incubated at 32°C for 8 to 12 weeks before the CFUs were enumerated. At week 4, 6, and 8 time points, the entire footpad homogenate was plated to maximize the detection of low CFU numbers.

Statistical analysis.

GraphPad Prism 6 was used to compare group means by Student’s t test and one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s posttest to adjust for multiple comparisons. A regimen was considered bactericidal when the CFU count was significantly lower (P < 0.05) than that of untreated controls at D0 and the footpad swelling had decreased to an ALI of <1.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01-AI113266).

We gratefully acknowledge TB Alliance for providing each oxazolidinone.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02171-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Phillips RO, Sarfo FS, Abass MK, Abotsi J, Wilson T, Forson M, Amoako YA, Thompson W, Asiedu K, Wansbrough-Jones M. 2014. Clinical and bacteriological efficacy of rifampin-streptomycin combination for two weeks followed by rifampin and clarithromycin for six weeks for treatment of Mycobacterium ulcerans disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:1161–1166. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02165-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Converse PJ, Nuermberger EL, Almeida DV, Grosset JH. 2011. Treating Mycobacterium ulcerans disease (Buruli ulcer): from surgery to antibiotics, is the pill mightier than the knife? Future Microbiol 6:1185–1198. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nienhuis WA, Stienstra Y, Thompson WA, Awuah PC, Abass KM, Tuah W, Awua-Boateng NY, Ampadu EO, Siegmund V, Schouten JP, Adjei O, Bretzel G, van der Werf TS. 2010. Antimicrobial treatment for early, limited Mycobacterium ulcerans infection: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 375:664–672. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61962-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klis S, Stienstra Y, Phillips RO, Abass KM, Tuah W, van der Werf TS. 2014. Long term streptomycin toxicity in the treatment of Buruli ulcer: follow-up of participants in the BURULICO drug trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8:e2739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Technical Advisory Group on Buruli Ulcer. 2017. Report from the meeting of the Buruli ulcer Technical Advisory Group. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Brien DP, Friedman D, Hughes A, Walton A, Athan E. 2017. Antibiotic complications during the treatment of Mycobacterium ulcerans disease in Australian patients. Intern Med J 47:1011–1019. doi: 10.1111/imj.13511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Food and Drug Administration. 2018. Clarithromycin (Biaxin): drug safety communication—potential increased risk of heart problems or death in patients with heart disease. US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace RJ, Brown BA, Griffith DE, Girard W, Tanaka K. 1995. Reduced serum levels of clarithromycin in patients treated with multidrug regimens including rifampin or rifabutin for Mycobacterium avium-M. intracellulare infection. J Infect Dis 171:747–750. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh W, Jeong B, Jeon K, Lee S, Shin SJ. 2012. Therapeutic drug monitoring in the treatment of Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186:797–802. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1088OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Ingen J, Egelund EF, Levin A, Totten SE, Boeree MJ, Mouton JW, Aarnoutse RE, Heifets LB, Peloquin CA, Daley CL. 2012. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex disease treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186:559–565. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0682OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reference deleted.

- 12.Ji B, Lefrançois S, Robert J, Chauffour A, Truffot C, Jarlier V. 2006. In vitro and in vivo activities of rifampin, streptomycin, amikacin, moxifloxacin, R207910, linezolid, and PA-824 against Mycobacterium ulcerans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1921–1926. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00052-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sotgiu G, Centis R, D'Ambrosio L, Alffenaar JC, Anger HA, Caminero JA, Castiglia P, De Lorenzo S, Ferrara G, Koh W, Schecter GF, Shim TS, Singla R, Skrahina A, Spanevello A, Udwadia ZF, Villar M, Zampogna E, Zellweger J, Zumla A, Migliori GB. 2012. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of linezolid containing regimens in treating MDR-TB and XDR-TB: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 40:1430–1442. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00022912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallis RS, Jakubiec W, Kumar V, Bedarida G, Silvia A, Paige D, Zhu T, Mitton-Fry M, Ladutko L, Campbell S, Miller PF. 2011. Biomarker-assisted dose selection for safety and efficacy in early development of PNU-100480 for tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:567–574. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01179-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lodise TP, Fang E, Minassian SL, Prokocimer PG. 2014. Platelet profile in patients with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections receiving tedizolid or linezolid: findings from the phase 3 ESTABLISH clinical trials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:7198–7204. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03509-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yotsu RR, Richardson M, Ishii N. 2018. Drugs for treating Buruli ulcer (Mycobacterium ulcerans disease). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8:CD012118. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012118.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alffenaar JWC, Nienhuis WA, de Velde F, Zuur AT, Wessels AMA, Almeida D, Grosset J, Adjei O, Uges DRA, van der Werf TS. 2010. Pharmacokinetics of rifampin and clarithromycin in patients treated for Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:3878–3883. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00099-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peloquin CA, Berning SE. 1996. Evaluation of the drug interaction between clarithromycin and rifampin. J Infect Dis Pharmacother 2:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallis RS, Dawson R, Friedrich SO, Venter A, Paige D, Zhu T, Silvia A, Gobey J, Ellery C, Zhang Y, Eisenach K, Miller P, Diacon AH. 2014. Mycobactericidal activity of sutezolid (PNU-100480) in sputum (EBA) and blood (WBA) of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS One 9:e94462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. 2018. Rapid Communication: Key changes to treatment of multidrug- and rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (MDR/RR-TB). World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee M, Lee J, Carroll MW, Choi H, Min S, Song T, Via LE, Goldfeder LC, Kang E, Jin B, Park H, Kwak H, Kim H, Jeon H, Jeong I, Joh JS, Chen RY, Olivier KN, Shaw PA, Follmann D, Song SD, Lee J, Lee D, Kim CT, Dartois V, Park S, Cho S, Barry CE. 2012. Linezolid for treatment of chronic extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 367:1508–1518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nuermberger E. 2016. Evolving strategies for dose optimization of linezolid for treatment of tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 20:48–51. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Converse PJ, Almeida DV, Tasneen R, Saini V, Tyagi S, Ammerman NC, Li S, Anders NM, Rudek MA, Grosset JH, Nuermberger EL. 2018. Shorter-course treatment for Mycobacterium ulcerans disease with high-dose rifamycins and clofazimine in a mouse model of Buruli ulcer. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12:e0006728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gandelman K, Zhu T, Fahmi OA, Glue P, Lian K, Obach RS, Damle B. 2011. Unexpected effect of rifampin on the pharmacokinetics of linezolid: in silico and in vitro approaches to explain its mechanism. J Clin Pharmacol 51:229–236. doi: 10.1177/0091270010366445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soriano A, Ortega M, García S, Peñarroja G, Bové A, Marcos M, Martínez JC, Martínez JA, Mensa J. 2007. Comparative study of the effects of pyridoxine, rifampin, and renal function on hematological adverse events induced by linezolid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:2559–2563. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00247-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang T, Li S, Nuermberger EL. 2012. Autoluminescent Mycobacterium tuberculosis for rapid, real-time, non-invasive assessment of drug and vaccine efficacy. PLoS One 7:e29774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang T, Li S, Converse PJ, Grosset JH, Nuermberger EL. 2013. Rapid, serial, non-invasive assessment of drug efficacy in mice with autoluminescent Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7:e2598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tasneen R, Betoudji F, Tyagi S, Li S, Williams K, Converse PJ, Dartois V, Yang T, Mendel CM, Mdluli KE, Nuermberger EL. 2016. Contribution of oxazolidinones to the efficacy of novel regimens containing bedaquiline and pretomanid in a mouse model of tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:270–277. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01691-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dega H, Bentoucha A, Robert J, Jarlier V, Grosset J. 2002. Bactericidal activity of rifampin-amikacin against Mycobacterium ulcerans in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:3193–3196. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.10.3193-3196.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dega H, Robert J, Bonnafous P, Jarlier V, Grosset J. 2000. Activities of several antimicrobials against Mycobacterium ulcerans infection in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:2367–2372. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.9.2367-2372.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.