Summary

The introduction of azole heterocycles into a peptide backbone is the principal step in the biosynthesis of numerous compounds with therapeutic potential. One of them is microcin B17, a bacterial topoisomerase inhibitor whose activity depends on the conversion of selected serine and cysteine residues of the precursor peptide to oxazoles and thiazoles by the McbBCD synthetase complex. Crystal structures of McbBCD reveal an octameric B4C2D2 complex with two bound substrate peptides. Each McbB dimer clamps the N-terminal recognition sequence, while the C-terminal heterocycle of the modified peptide is trapped in the active site of McbC. The McbD and McbC active sites are distant from each other, which necessitates alternate shuttling of the peptide substrate between them, while remaining tethered to the McbB dimer. An atomic-level view of the azole synthetase is a starting point for deeper understanding and control of biosynthesis of a large group of ribosomally synthesized natural products.

Keywords: antibiotic, protein complex crystal structure, Escherichia coli microcin B17, DNA gyrase, RiPP, LAP, azole synthetase, cyclodehydratase, heterocyclase, dehydrogenase

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Azole synthetase McbBCD is co-crystallized with its product, microcin B17

-

•

Crystal structure of McbBCD reveals an octameric assembly of B4C2D2

-

•

Two McbB subunits within each asymmetric unit interact to recognize a peptide

-

•

Formation of each azole ring requires shuttling of peptide between two active centers

A topoisomerase inhibitor microcin B17 of Escherichia coli is synthesized from a ribosomally made precursor by conversion of serine and cysteine residues to thiazole and oxazole rings. Ghilarov et al. solved the crystal structure of octameric cyclodehydratase/dehydrogenase complex McbBCD, reconciling data from almost 30 years of studies.

Introduction

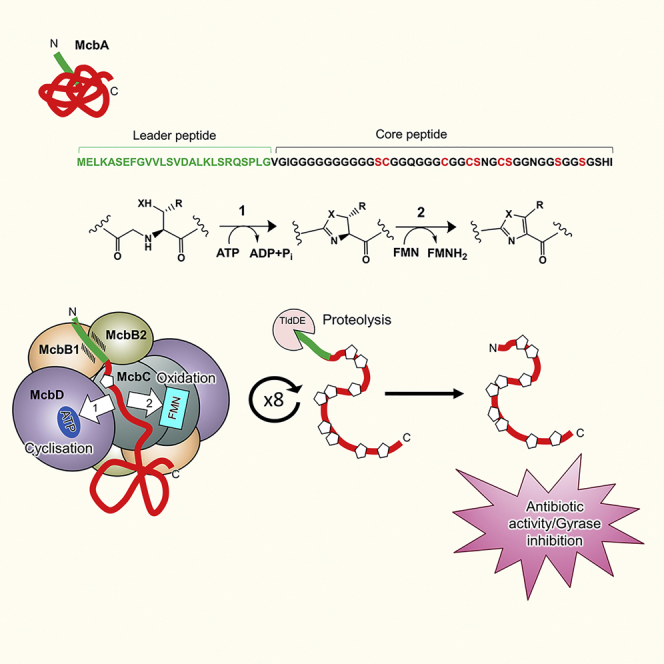

Resistance to antibiotics is one of the biggest threats facing mankind in the 21st century. DNA topoisomerases are among the most successful targets for antimicrobial agents, with the quinolone drugs enjoying spectacular success. However, resistance to quinolones is now a serious problem, and there is an urgent need to find replacements. Complex natural products selected by eons of microbial co-evolution represent an attractive source of new antibiotic scaffolds (Brown and Wright, 2016, Walsh, 2017). Microcin B17 (MccB17) is a ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide (RiPP) antibiotic produced by Escherichia coli that targets a bacterial topoisomerase, DNA gyrase, in a similar way to quinolones but appears to bind at a distinct site (Heddle et al., 2001, Pierrat and Maxwell, 2005). Within the larger RiPP group, MccB17 is classified as a prototypic member of an extended family of linear azole-modified peptides, or LAPs—ribosomally synthesized peptides containing azole heterocycles and endowed with diverse biological activities (Burkhart et al., 2017, Melby et al., 2011). MccB17 biosynthesis is encoded by a plasmid-borne seven-gene cluster mcbABCDEFG (Genilloud et al., 1989). The antibiotic activity appears after the 69-aa McbA precursor peptide is modified by the products of the mcbBCD genes, which transform 4–5 serine and 4 cysteine McbA residues into, respectively, 4–5 oxazole and 4 thiazole heterocycles (Heddle et al., 2001, Yorgey et al., 1994). Following the typical logic of RiPP biosynthesis (Oman and van der Donk, 2010), the N-terminal leader peptide (McbA 1–26) is used for the peptide recognition by McbBCD and heterocyclization and is later removed by the action of the chromosomally encoded TldD/E protease before the active compound is exported from the cell (Allali et al., 2002, Ghilarov et al., 2017, Madison et al., 1997) (Figure 1).

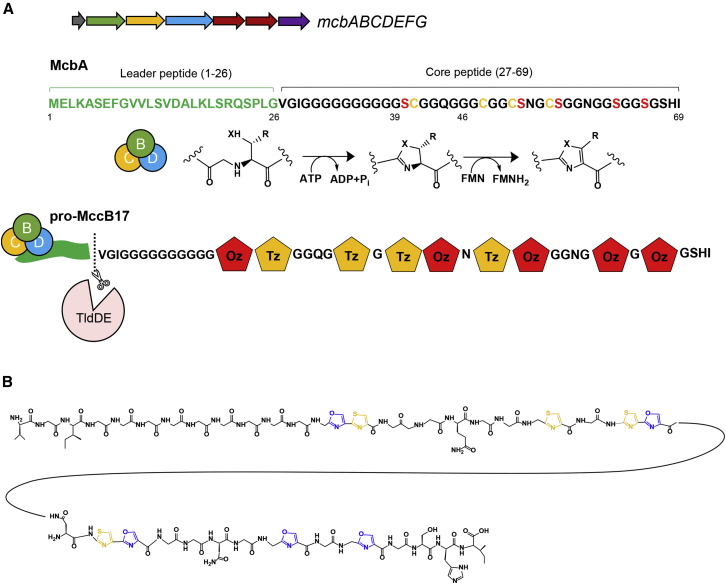

Figure 1.

Structure and Biosynthesis of MccB17

(A) General scheme of MccB17 biosynthesis. The gene cluster mcbABCDEFG is color coded according to recommended nomenclature (Arnison et al., 2013). The McbBCD complex is shown as green, yellow, and blue circles. The leader peptide is indicated in green and heterocyclization sites of McbA peptide in red and yellow. Yellow and red pentagons indicate thiazoles and oxazoles, respectively, of the modified peptide. TldD/E is a protease responsible for the removal of the leader peptide, leading to the dissociation of mature MccB17 from the McbBCD complex.

(B) Chemical structure of mature MccB17 (26–69).

Different azole-containing peptides are identified by genome mining (Cox et al., 2015), but the mechanisms responsible for heterocycle formation are not fully understood. Early studies showed that McbB, McbC, and McbD form a stoichiometric complex that in vitro introduces heterocycles into the McbA peptide precursor in the presence of ATP (Li et al., 1996). Advances coming from studies of different RiPPs revealed the universally conserved YcaO domain (corresponding to McbD) to be a heterocyclase responsible for the azoline cycle formation (Dunbar et al., 2012, Dunbar et al., 2014, Koehnke et al., 2013, Koehnke et al., 2015). O18 transfer studies confirmed that ATP is directly used by YcaO for activation of an amide bond, with the phosphate group facilitating removal of water (Dunbar and Mitchell, 2013). Leader peptide recognition is thought to be mediated by the McbB protein, which shares homology with the E1/ubiquitin ligase-like proteins and contains a so-called RRE (RiPP recognition element): a leader-binding motif common to several unrelated RiPPs (Burkhart et al., 2015, Dunbar et al., 2014, Koehnke et al., 2015, Ortega et al., 2015, Regni et al., 2009). In about half of the known YcaO-containing clusters, McbB and McbD homologs are fused into a single polypeptide (Burkhart et al., 2017).

Azole introduction into the MccB17 precursor requires coordination of the activities of the heterocyclase, which converts Ser and Cys residues into azolines, and the dehydrogenase, which oxidizes the azolines to azoles. In contrast to some other systems (McIntosh and Schmidt, 2010, Molohon et al., 2011), reduced azoline cycles have never been observed during MccB17 biosynthesis, suggesting tight coupling of the two reactions (Belshaw et al., 1998, Milne et al., 1999). There is a strict N-C directionality in the introduction of azolines/azoles that currently remains largely unexplained (Kelleher et al., 1999).

Structural information on azole biosynthesis in RiPPs remains scarce. Relevant structures of the YcaO domain from RiPP clusters include the cyanobactin heterocyclases LynD (from Lyngbya sp.) (Koehnke et al., 2015) and TruD (from Prochloron spp.) (Koehnke et al., 2013) and a thioamidation YcaO from Methanopyrus kandleri (Mahanta et al., 2018). Another available structure is that of E. coli YcaO (Dunbar et al., 2014), an enzyme that is not associated with LAP biosynthesis but is structurally very similar to YcaO proteins from RiPP clusters mentioned above. Only one LAP dehydrogenase is characterized structurally: ThcOx from a cyanothecamide pathway (Bent et al., 2016). None of these structures has a substrate peptide bound apart from LynD, where only the leader peptide of PatE is observed in the electron density.

In this work, we developed a strategy for co-purification of the modified McbA peptide together with all three components of the MccB17 synthetase as a stable complex. We report four crystal structures of apo- and peptide-bound synthetase in complex with ATP and FMN ligands. These structures provide the first snapshots of the organization of a multimeric heterocyclase-dehydrogenase catalytic complex and show the spatial relationships between the two distinct enzymatic activities and the leader peptide binding site. We propose that the general organization of the McbBCD complex could be common to other LAP synthetases that have the same domain composition and connectivity. The structures obtained in this work provide a three-dimensional framework to interpret the abundant biochemical data collected on MccB17 and other LAPs.

Results and Discussion

Purification and Crystallization of McbBCD-pro-MccB17 Complexes

Deletion of the tldD gene leads to intracellular accumulation of the full-length MccB17 precursor bearing nine heterocycles (pro-MccB17) in MccB17-producing E. coli cells (Allali et al., 2002, Ghilarov et al., 2017). We hypothesized that in the absence of TldD/E proteolysis, a modified McbA peptide may remain bound to the McbBCD synthetase. Indeed, introduction of an N-terminal hexahistidine tag into the McbA peptide enabled co-purification of the modified peptide together with all three components of the MccB17 synthetase complex. Size exclusion chromatography confirmed that McbB, McbC, McbD, and pro-MccB17 co-elute in a single sharp peak, suggesting a stable complex, which we named BCD-pB17. The molecular weight of the complex determined by analytical size exclusion chromatography was estimated at ∼260 kDa, more than twice the mass expected for a 1:1:1:1 stoichiometry, and thus suggesting that the functional unit of McbBCD contains two copies of each component. A similar result was obtained for a homologous KlpBCD synthetase (Travin et al., 2018) (Figures S1D and S1E). Treatment of BCD-pB17 with purified TldD/E protease (Ghilarov et al., 2017) led to the formation of fully mature active MccB17 with nine heterocycles (MW 3,074 Da), leaving peptide-free McbBCD complex (BCD-free), which was no longer retained on a Ni-NTA column (data not shown). A similar approach was used to purify a BCD complex with a His-tagged MccB17 precursor truncated at residue 46 (Belshaw et al., 1998, Kelleher et al., 1999) and thus harboring only the first bis-heterocycle (BCD-pB17short). Four crystal structures were determined: BCD-free, BCD-pB17, BCD-pB17 with ADP plus phosphate (BCD-pB17-ADP-P), and BCD-pB17short (see Figure S2 and Table 1).

Table 1.

X-Ray Data Collection and Processing Statistics for MccB17 Synthetase

| Dataset | BCD-pB17 SeMet | BCD-pB17 Native | BCD-pB17-ADP-P | BCD-pB17short | BCD-free |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beamline | I03 | I24 | I04 | I02 | I03 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9798 | 0.9790 | 0.9795 | 0.9795 | 0.9795 |

| Detector | Pilatus 6M | Pilatus 6M | Pilatus 6M | Pilatus 6M | Pilatus 6M |

| Resolution range (Å)a | 90.45–2.40 (2.46–2.40) | 57.39–2.10 (2.15–2.10) | 86.76–2.35 (2.41–2.35) | 57.54–1.85 (1.90–1.85) | 91.92–2.70 (2.77–2.70) |

| Space group | C2 | C2 | C2 | C2 | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 181.0, 83.1, 86.7 | 181.0, 83.4, 86.9 | 180.6, 83.3, 86.8 | 180.7, 83.7, 87.1 | 183.9, 82.1, 87.5 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0, 91.7, 90.0 | 90.0, 91.5, 90.0 | 90.0, 91.4, 90.0 | 90.0, 91.3, 90.0 | 90.0, 91.45, 90.0 |

| Total observationsa | 690,691 (49,659) | 800,263 (56,044) | 409,359 (29,556) | 595,165 (44,272) | 245,530 (17,471) |

| Unique reflectionsa | 50,386 (3,712) | 75,405 (5,495) | 53,732 (3,965) | 110,695 (8,183) | 35,976 (2,618) |

| Multiplicitya | 13.7 (13.4) | 10.6 (10.2) | 7.6 (7.5) | 5.4 (5.4) | 6.8 (6.7) |

| Mean I/σ(I)a | 9.9 (1.5) | 10.7 (1.6) | 11.6 (1.2) | 11.3 (1.2) | 13.1 (1.1) |

| Completeness (%)a | 100.0 (99.9) | 99.8 (99.4) | 99.9 (99.5) | 99.9 (99.8) | 99.9 (99.8) |

| Rmergea,b | 0.220 (1.879) | 0.153 (1.489) | 0.140 (1.641) | 0.086 (1.435) | 0.118 (1.660) |

| Rmeasa,c | 0.229 (1.954) | 0.161 (1.568) | 0.150 (1.763) | 0.095 (1.587) | 0.128 (1.801) |

| CC½a,d | 0.997 (0.398) | 0.998 (0.540) | 0.998 (0.422) | 0.998 (0.388) | 0.998 (0.436) |

| Wilson B value (Å2) | 52.0 | 35.7 | 45.9 | 30.7 | 65.8 |

Values for the outer resolution shell are given in parentheses.

Rmerge = ∑hkl ∑i |Ii(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉|/ ∑hkl ∑iIi(hkl).

Rmeas = ∑hkl [N/(N − 1)]1/2 × ∑i |Ii(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉|/∑hkl ∑iIi(hkl), where Ii(hkl) is the ith observation of reflection hkl, 〈I(hkl)〉 is the weighted average intensity for all observations i of reflection hkl, and N is the number of observations of reflection hkl.

CC½ is the correlation coefficient between symmetry-related intensities taken from random halves of the dataset.

The Structure of the McbBCD-pro-MccB17 Complex, BCD-pB17

The asymmetric unit of the MccB17 synthetase structure is comprised of one copy each of McbC and McbD and, unexpectedly, two copies of McbB (Figure 2; Video S1). This tetrameric assembly associates with a copy of itself (#McbB2CD) to generate an octameric McbB4C2D2 complex, with a total molecular weight of around 290 kDa and approximate dimensions of 150 × 85 × 85 Å. The 2-fold interface is dominated by interactions between the two opposing FMN-containing McbC dehydrogenase subunits, with an interface area of 5,361 Å2, whereas the two copies of the McbD cyclodehydratase lie at opposite ends of the assembly. Within the asymmetric unit, the two copies of the non-catalytic McbB subunits adopt different conformations, and we refer to these as McbB1 and McbB2. They interact closely with each other (1,483 Å2); McbB1 interacts also with #McbC (1,509 Å2), while McbB2 interacts with McbD (2,191 Å2). Although mass spectrometry shows that the fully modified hexahistidine-tagged MccB17 precursor peptide (pro-MccB17, MW = 6,712 Da) is present in the purified synthetase complex after size exclusion, only a handful of pB17 fragments are resolved in the electron density at subunit interfaces (Figure 2; see also Video S1 and Figure S2 for nomenclature and Figure S3 for the omit difference density maps). In particular, the leader peptide is visible at both McbB1-McbB2 interfaces, and the terminal oxazole moiety is visible adjacent to the FMN in the dehydrogenase active sites, which lie at the interface between the pair of McbC subunits at the core of the octamer.

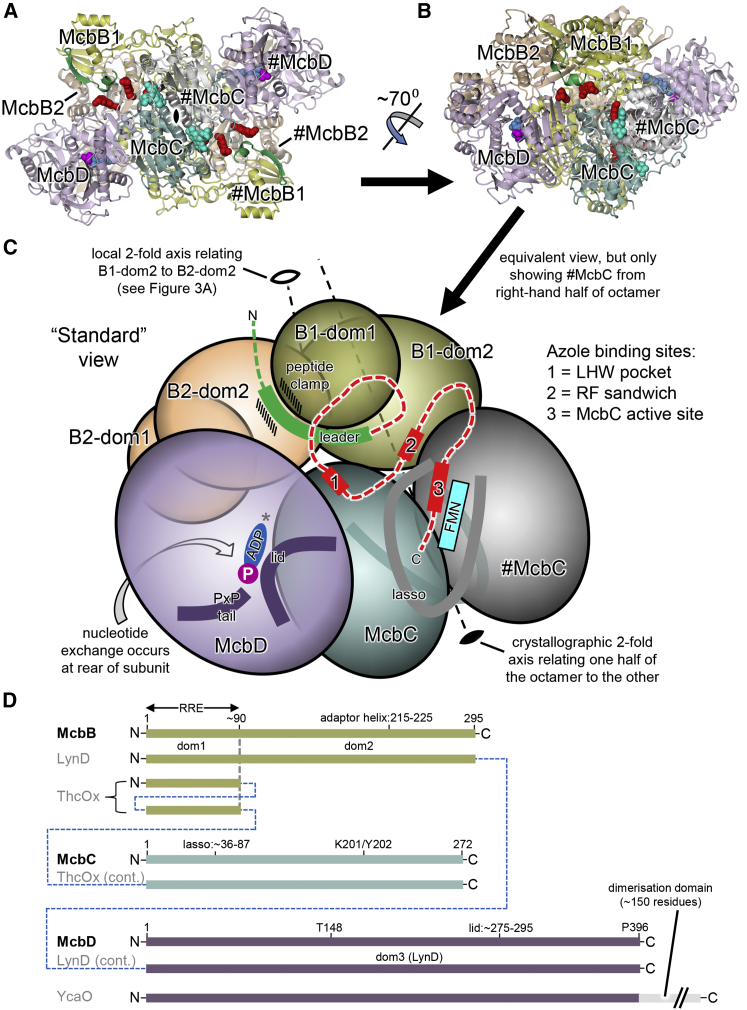

Figure 2.

Structure of the Microcin B17 Synthetase Complex

(A) The full McbB4C2D2 octamer in cartoon representation as viewed down the crystallographic 2-fold axis (indicated by the black symbol) with individual subunits labeled, where those belonging to the right-hand asymmetric unit are preceded by the hash (#) symbol. Two copies of the leader peptide are shown in green cartoon representation and as van der Waals spheres: ADP (blue), phosphate (magenta), FMN (cyan), and bound heterocycles (red).

(B) Alternate view, which will be the “standard” view for many of the subsequent figures (the subunit coloring scheme is maintained throughout).

(C) Schematic representation of standard view showing the asymmetric unit plus the copy of McbC from the other tetramer (#McbC), with key features labeled. The two copies of McbB are split into the smaller N-terminal domain (dom1) and the larger C-terminal domain (dom2). Crystallographic and local 2-fold axes are shown as dashed lines and marked by closed and open symbols, respectively. A possible path for pro-MccB17 in the BCD-pB17 structure is indicated by the dashed red line, which links up the leader peptide with the crystallographically observed heterocycles. The asterisk adjacent to the ADP indicates the location of Leu222 from #McbB1 (which is not shown) that helps to provide nucleotide specificity.

(D) Annotated linear representations of McbB, McbC, and McbD aligned with selected homologs of known structure. The dashed blue lines indicate where elements are fused in the homologs. ThcOx possesses two copies of the RRE domain fused directly onto an equivalent of McbC (Bent et al., 2016, Burkhart et al., 2017). Ec-YcaO differs from McbD and LynD in that it has a C-terminal dimerization domain and thus does not have a C-terminal proline residue inserted into the active site pocket.

Shown are observed parts of McbA peptide (green cartoon representation) and, as van der Waals spheres, ADP (blue), FMN (cyan), and bound heterocycles (red).

The Structure and Function of McbB Subunits Are Context Dependent

One of the unexpected features of the McbBCD synthetase structure is the presence of a second copy of McbB in the asymmetric unit, giving a total of four monomers in the full assembly (Figure 3). They are each comprised of a smaller N-terminal domain with a winged-helix fold that corresponds to the RREs of other RiPP-modifying enzymes, and a larger C-terminal domain, resembling the adenylation domains of E1-like enzymes. These two domains correspond closely to domains 1 and 2 of the homodimeric enzymes LynD (Figure 3) and TruD. The two subunits of LynD and TruD have a head-to-tail arrangement within the dimer, which juxtaposes domain 1 of each subunit with domain 2 of the other to form two copies of the so-called “peptide clamp” responsible for binding of the leader peptide. The two copies of McbB domain 2 within the asymmetric unit show a similar relationship, but the relative placement of domain 1 differs significantly between McbB1 and McbB2 such that the McbB1:McbB2 dimer is asymmetric and there is only one equivalent of the peptide clamp, between McbB1-dom1 and McbB2-dom2. Another notable difference between McbB1 and McbB2 is the conformation of α helix 9 in domain 2, which we termed the “adaptor” helix. In McbB2, it is involved in the peptide clamp, while in McbB1 it forms contacts with the nucleotide bound in #McbD (see below). Thus, the two McbB subunits in the octamer have different functions (Figure 3).

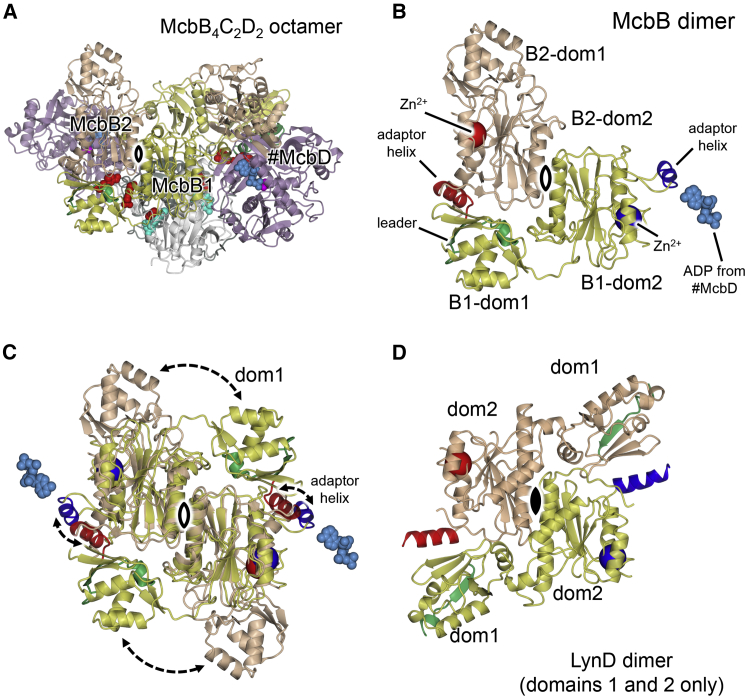

Figure 3.

The Structure of McbB

(A) The full McbB4C2D2 octamer as represented in Figure 2 but viewed down the local 2-fold axis that relates McbB1B1-dom2 to McbB2 B2-dom2 (open symbol).

(B) The McbB dimer in isolation shown in the same orientation as in (A), where the structural zinc ion and adaptor helix are shown in dark blue for McbB1 and in red for McbB2. Also shown are the ADP molecule from #McbD, which interacts with the McbB1 adaptor helix, and the leader peptide, which interacts with the McbB2 adaptor helix.

(C) Superposition of the McbB dimer (as shown in B) upon itself to emphasize the relative positions of domain 1 and the adaptor helix between McbB1 and McbB2.

(D) Equivalent representation of LynD homodimer (with domain 3 not shown). In this instance, the subunits are identical (being related by crystallographic symmetry; closed symbol) and adopt a conformation that corresponds closely to that of McbB1.

The presence of zinc in McbB was previously established (Milne et al., 1999) and was the basis for its initial assignment as a heterocyclase, which turned out to be incorrect. In our structures, the metal ion is bound to four Cys residues (Cys192, Cys195, Cys290, and Cys292) in each monomer (Figures 3, S3H, and S3I). The metal ions appear to have a purely structural role in tethering the C-terminal part of McbB to the core of domain 2.

Leader Peptide Binding Site

In the structure of BCD-pB17, most of the 26-residue MccB17 leader peptide is resolved (residues 4–22). The peptide folds into a β turn (residues 6–9), followed by a β strand (residues 9–14), and a short α helix (residues 16–21). The majority of leader peptide interactions with the synthetase involve McbB1-dom1 (RRE), where residues 9–14 of the leader contribute a fourth β strand to the anti-parallel β sheet of the winged helix motif (Figure 4). A similar arrangement is seen in the peptide clamp of LynD (Koehnke et al., 2015) and other RiPP-modifying enzymes (Burkhart et al., 2015). Additionally, the side chains of Phe8 and Leu12 of McbA occupy two hydrophobic pockets, one lying at the end of the three-helix bundle in McbB1-dom1 and the other at the interface between McbB1-dom1 and McbB2-dom2, respectively (Figures 4C and 4D). The existence of these pockets explains why the FxxxL motif of McbA (Roy et al., 1998) or, more generally, an Fxxx[L/I/V] motif in the leader sequences of other peptide toxins (Mitchell et al., 2009) was previously reported as being critically important for leader peptide binding to the synthetase. Finally, the α-helical portion of the McbA leader is tethered to McbB2-dom2 via two salt bridges: Asp15 and Lys18 of McbA pair up with Lys175 and Glu176 of McbB2, respectively (Figures 4E and 4F). The former residues were previously implicated in leader peptide binding based on mutational analysis (Roy et al., 1998).

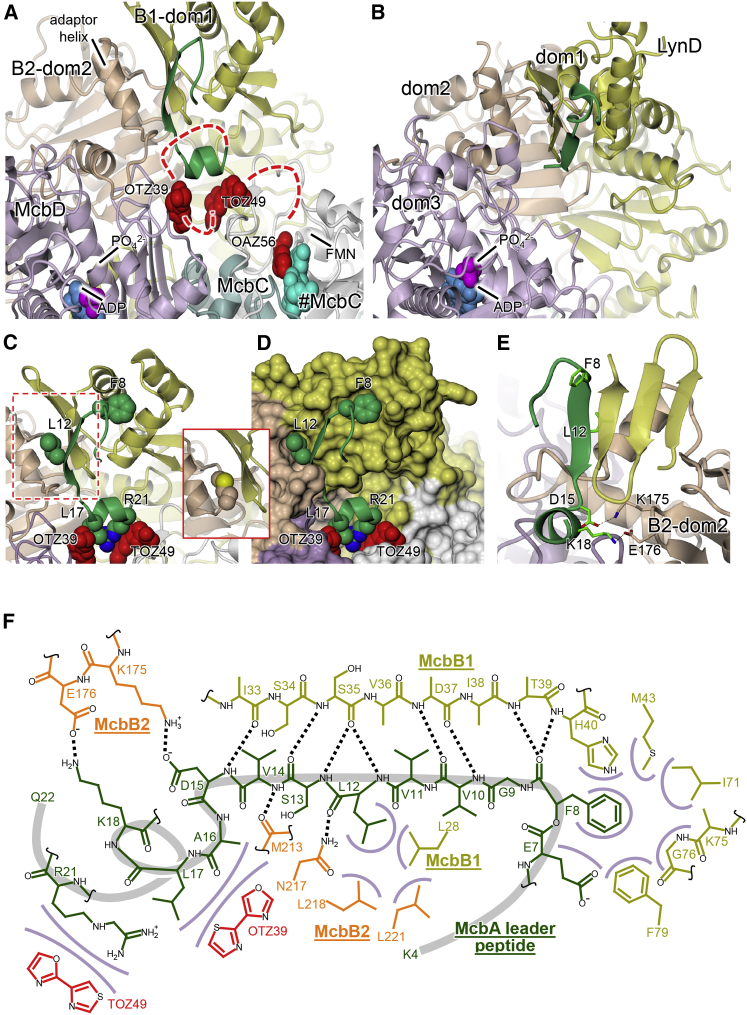

Figure 4.

The Peptide Clamp and Relative Positions of Leader Peptides and Heterocyclase Active Sites in McbBCD and LynD

(A) Overview showing the relative dispositions of peptide clamp (green), the two active sites, and the bound heterocycles in the BCD-pB17 structure (view as in Figure 2C).

(B) Equivalent view for LynD showing that the peptide clamp and the heterocyclase active sites are similarly placed with respect to each other.

(C and D) Close-up views (in cartoon [C] and molecular surface [D] representations, respectively) of the peptide clamp region emphasizing the van der Waals interactions made by the leader peptide, i.e., Phe8 with the three-helix bundle of McbB1-dom1, Leu12 at the McbB1-dom1/McbB2-dom2 interface, and Leu17 and Arg21, with bound heterocycles (see Figure S3). The inset shows the interface in the BCD-free structure where the McbB2 Met213 occupies the pocket that is otherwise used by Leu12 of the leader peptide.

(E) Orthogonal view showing only the anti-parallel β sheet for McbB1-dom1 to emphasize the extension of the latter by residues 9–14 of the leader peptide, in addition to the salt bridges formed between Asp15 and Lys18 of the leader and a loop of McbB2-dom2.

(F) Schematic diagram showing contacts between the leader peptide (dark green), McbB1 (olive), and McbB2 (orange). Black dotted lines denote hydrogen bonds and salt bridges, while van der Waals interactions are represented by lilac arcs. In red are putative bis-heterocycles observed in the electron density.

There are no large conformational changes between the McbBCD structures with and without bound peptide (i.e., BCD-pB17 versus BCD-free; overall RMSD of 0.868 Å), with the most significant differences being small changes in the orientations of domains 1 of both McbB1 and McbB2 and that the loop preceding the adaptor helix in McbB2 (residues 204–212) and a neighboring loop (residues 34–40) in McbD are both disordered in the absence of leader peptide. Additionally, in BCD-free, Met213 of McbB2 re-adjusts such that its side chain occupies the pocket at the McbB1-dom1/McbB2-dom2 interface that accommodates Leu12 of the leader peptide in the BCD-pB17 complex (Figure 4C, inset). It is notable that the orientation and position of the leader peptide relative to the heterocyclase active site is essentially conserved between McbBCD and LynD, which suggests that the direction from which the peptide substrate approaches the active site is common to both (Figure 4B). Curiously, however, while LynD also adds heterocycles sequentially, it does so starting from the C-terminal end of the substrate (Koehnke et al., 2015).

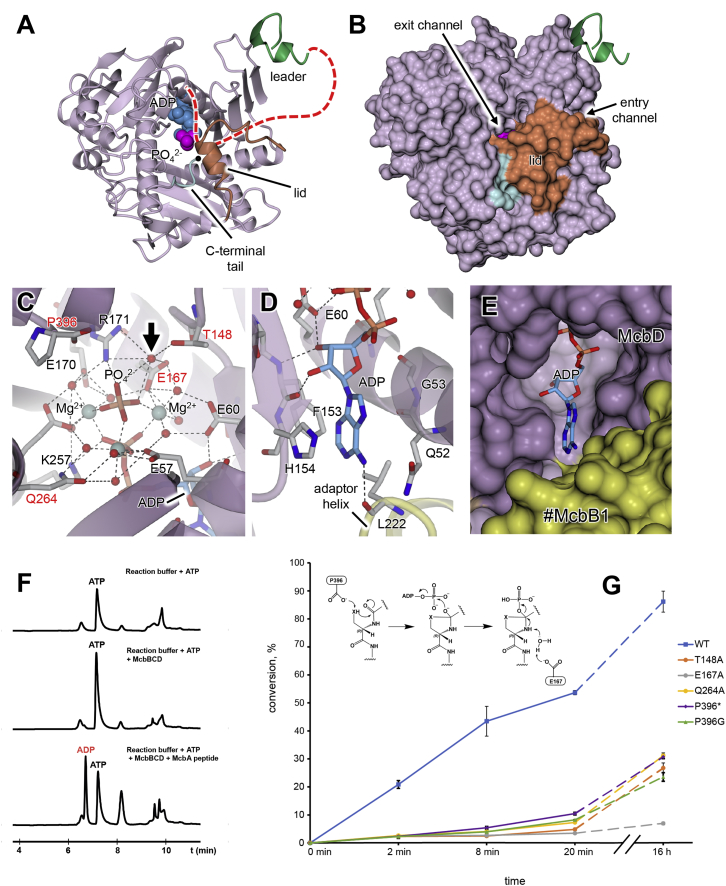

Structure of the Cyclodehydratase McbD

The two copies of McbD lie at opposite ends of the octamer, each of them interacting mostly with McbB2. The McbD structure is very similar to those of LynD and TruD (domain 3) and E. coli YcaO, despite the low level of sequence identity (e.g., 15% with LynD). The structure can be divided into three α/β sub-domains, forming a central cavity (Figures 5 and S5) containing the nucleotide-binding site and the expected site of heterocyclization. Although the nucleotide-bound structure was obtained through co-crystallization with ATP, the electron density is consistent with ADP plus a phosphate ion, the latter being linked to the β-phosphate of the ADP by a ring of three magnesium ions, as was also observed for LynD. The adenine moiety is mainly held by van der Waals contacts and π-stacking interactions between the base and His154 on one side, and the Gln52-Gly53 peptide on the other side. The only hydrogen bonding interaction with the adenine is between the N5 amino group and the carbonyl oxygen of Leu222 from McbB1 in the opposing asymmetric unit. Leu222 lies at the end of the adaptor helix that projects away from the core of McbB1-dom2 relative to its counterpart in McbB2 that forms part of the peptide clamp (see above and Figures 3 and 4). The nucleotide binding site is accessible from the underside of McbD, as viewed in Figure 2C, indicating that nucleotide exchange likely occurs from this side.

Figure 5.

The Structure and Mechanism of the Heterocyclase McbD

(A and B) show the isolated McbD subunit (in standard view) in cartoon (A) and molecular surface (B) representations. Also shown is the relative position of the leader peptide (green, which is somewhat in the foreground) and, as van der Waals spheres, the bound ADP (blue) and phosphate (magenta). The lid region (orange) and C-terminal tail (cyan) partially occlude the active site, although the phosphate is just visible through a pore that we designate the exit channel (see also Figure S5). A putative path for the substrate peptide extending from the end of the leader and going through the McbD active site (under the lid) is traced by the red dashed line in (A), and the Cα of the terminal Pro396 is highlighted by the black sphere.

(C) Close up of the active-site region adjacent to the phosphate ion showing side chains (in stick representation) that interact with the ADP, phosphate, and associated magnesium ions. The residues selected for mutagenesis are labeled in red. Also shown is a highly coordinated water molecule (indicated by the black arrow), for which we postulate a role in catalysis (see also Figures 5G and S6).

(D) Close up of the interactions with the ribose and base of ADP as viewed from the rear of the subunit relative to the standard view (Figure 2C), also showing the interaction with Leu222 in the adaptor helix of #McbB1.

(E) Molecular surface representation of region shown in (D), showing that nucleotide exchange is possible from this side of McbD.

(F) HPLC traces of reactions containing McbBCD and ATP. ADP is formed in the presence of a substrate peptide.

(G) A diagram of efficiency of substrate conversion by different active-center mutants along with the proposed mechanism of McbD (see also Figures S4 and S6). Briefly, we suggest that Pro396 takes the role of a general base to activate a nucleophile (X = O, S) for attack on an adjacent carbonyl leading to the postulated hemiorthoamide intermediate to be activated by ATP. Phosphate elimination initiated by a coordinated water molecule leads to the formation of an azoline. Substrate conversion efficiency was calculated similarly to (Dunbar et al., 2014) but for 9 heterocycles. Three independent reactions were analyzed for each time point, and the resultant means are presented, with errors plotted as ±1 SD.

The site of heterocyclization is expected to lie adjacent to the phosphate ion and, given the location of the peptide clamp that tethers the peptide substrate, would need to be accessed from the front, as viewed in Figure 2C. In our structures, this site is partially occluded by a surface loop, which we term the “lid” (residues 275–295), and by the C terminus of McbD, leaving only two narrow pores (Figures 5 and S5). Two possible mechanisms exist whereby the precursor peptide could access the McbD active site. The C-terminal end of McbA could be threaded into the site up to the modification point. In addition to an entry channel, this would also necessitate an exit channel to prevent the active site “clogging up” with peptide. This option appears to be commensurate with our structure without substantive structural changes. However, it is seemingly inconsistent with an earlier observation that C-terminal McbA fusions to β-gal can be efficiently modified (Madison et al., 1997). An alternative looping mechanism, whereby a loop of the precursor flips into the active site, would require more significant changes to McbD. The equivalent of the McbD lid in LynD is substantially more open (Figure S5), suggesting that a structural change here could provide unhindered access to the active site. Indeed, once substrate has entered the active site, it could be transiently trapped by the re-closure of the lid, with the flanking peptide chains emerging from the two pores described above. Nevertheless, we see no evidence of different lid conformations in our structures.

The Heterocyclase Mechanism

A number of mechanisms were proposed for azoline formation by YcaO-domain enzymes (reviewed in detail in Burkhart et al., 2017, Truman, 2016). In the McbBCD structure co-crystallized with ATP, the β-γ phosphodiester bond of ATP is cleaved, which was previously seen in other structures (Koehnke et al., 2015, Dunbar et al., 2014) and is consistent with a suggested kinase mechanism of substrate activation (Dunbar et al., 2012). In order to additionally verify our observations, nucleotides present in McbBCD-containing reactions were analyzed by LC/MS. A peak for ADP was readily observed, but only in the presence of McbA substrate, suggesting strong coupling between the modification and nucleotide turnover (Figure 5F). The presence of an ester-bond-containing form of MccB17 that results from an acyl shift during biosynthesis (Ghilarov et al., 2011) strongly suggests that the reaction occurs via formation of a hemiorthoamide intermediate, which can be subsequently phosphorylated by ATP (see Figure 5G). In this mechanism, two general bases are implicated: the first to activate either a serine hydroxyl or a cysteine thiol group for nucleophilic attack, and the second to facilitate phosphate release from the phosphorylated hemiorthoamide. We tried to identify residues that could serve as general bases in the likely substrate binding site adjacent to the phosphate (Figure 5C). The ConSurf (Ashkenazy et al., 2010, Ashkenazy et al., 2016, Celniker et al., 2013, Glaser et al., 2003, Landau et al., 2005) server mapped residues 147–151 and the C-terminal tail (393–396) as the most conserved elements of McbD in addition to the three long α helices providing the ATP coordination sphere (Figure S7).

A number of residues were selected for site-directed mutagenesis, including Glu167 and Gln264 from the ATP coordination sphere; Thr148, which is either a Thr or a Ser in RiPP-associated YcaO domains; and the C-terminal Pro396 (that has a free carboxyl), which was shown to be important for BalhD and McbD catalysis (Dunbar et al., 2014). As expected, a replacement of one of the highly conserved Mg2+-coordinating Glu residues (E167A) almost completely abolished processing when compared to a wild-type complex; however, slow accumulation of one heterocycle could be observed overnight (Figures 5G, S4A, and S4B). A Q264A replacement also lead to a major decrease in substrate processing (heterocycle accumulation) as judged by MALDI-MS, with the full complement of 9 heterocycles forming in vitro only after overnight incubation (Figures 5G and S4C). Similar results were obtained for T148A substitution (Figure S4D). It is notable that Thr148 is the first residue of a β turn giving a backbone conformation that projects its side chain into the active site cavity, a feature that is common to all known structures of YcaO domains. Replacement of two C-terminal prolines (Pro396 and Pro394) by glycines significantly affected processing; however, a small fraction of a fully modified product was still present (Figures 5F and S4E). In contrast, a deletion of the C-terminal Pro396 (P396∗ mutant) led to the accumulation of a tetra-azole product, with trace amounts of a penta-azole species formed only after overnight incubation (Figure S4F). Iodacetamide labeling of the reaction products showed that the tetra-azole intermediate had four Cys residues protected from alkylation (i.e., the modifications were all thiazoles; Figure S4G). This differs from the wild-type synthetase which generates the oxazole-thiazole bis-heterocycle first (Kelleher et al., 1999) and then proceeds to complete the remaining six or seven cycles in sequence. Therefore, either the processing of the rings is severely dysregulated in the mutant, as was seen previously for BalhD Pro429∗ (Dunbar et al., 2014), or the mutant entirely lost the ability to process serines. Since thiol is a better nucleophile than hydroxyl, the predominant processing of cysteines by the Pro396∗ mutant suggests that the C-terminal residue is the general base that initiates the heterocyclization mechanism. After manual modeling of potential conformations of substrate and intermediate in the active center (Figure S6), we conclude that Thr148 is most likely involved in the dephosphorylation event leading to formation of the azoline product. Thr148 would require deprotonation by a neighboring residue to act as a base, but there are no suitable candidates in the immediate vicinity. We propose that a highly coordinated water (Figure 5) acts as the base after deprotonation by Glu167 and that the main role of Thr148 is to correctly position this water (Figures 5G and S6). Similarly, Gln264 might be implicated in the coordination of Mg2+ ions and water molecules that help to stabilize the phosphate group during catalysis.

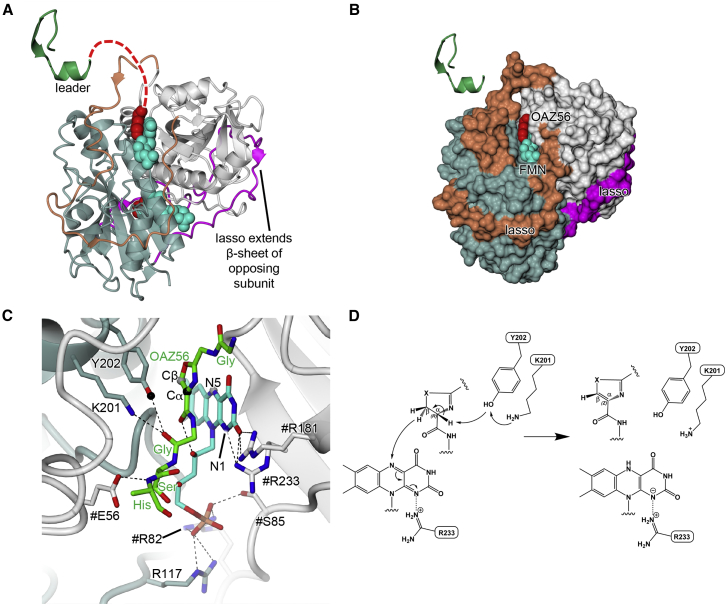

Structure and Mechanism of the Dehydrogenase McbC

Located in the center of the octameric synthetase complex, the two McbC subunits adopt an α/β-fold with a six-stranded antiparallel β sheet surrounded by nine α helices. Apart from the main dimer interface between two long α helices, a 50-residue surface loop from each subunit lassoes its neighbor, adding a seventh strand to the β sheet of the other subunit (Figure 6). Each McbC subunit contributes to the binding of the FMN cofactor molecules, with Arg82 of one McbC subunit and Arg117 of the other forming salt bridges with the phosphate group and Arg181 interacting with the O2 of FMN.

Figure 6.

The Structure and Mechanism of the Dehydrogenase McbC

(A and B) show the isolated McbC dimer (in standard view) in cartoon (A) and molecular surface (B) representations, respectively. McbC and its lasso are colored slate blue and magenta, respectively, while #McbC and its lasso are colored gray and orange, respectively. Also shown is the relative position of the leader peptide (green) and, as van der Waals spheres, the oxazole (OAZ56; red) bound alongside the FMN cofactor (cyan). A putative path for the substrate peptide extending from the end of the leader and going toward the McbC active site is traced by the red dashed line in (A).

(C) Close up of the active site region showing side chains (in stick representation) that interact with the FMN and bound product. The black spheres indicate the atoms involved in the deprotonation step, and the gray spheres indicate the atoms involved in the hydride transfer.

(D) Proposed general mechanism for McbC: an activated Tyr202 abstracts a proton from the α carbon of an azoline substrate, which results in E2 elimination of the antiproton from the β carbon and hydride transfer to FMN. Instead of a proton being provided to FMN by a general base to yield FMNH2, we propose that the negative charge on N1 of FMN is stabilized by a salt bridge with Arg233.

A Gly-oxazole-Gly-Ser fragment, representing the very C terminus of pro-MccB17, is bound facing each FMN molecule such that the oxazole ring stacks against the FMN ring system. The peptide fragment is thus placed between the cofactor and the previously characterized catalytic residues (Melby et al., 2014) Lys201 and Tyr202. Given that the Lys201-Tyr202 pair is poised over the α carbon of the bound oxazole product in the as-isolated complex, catalysis likely proceeds via the polar mechanism proposed by Melby et al. (2014). In this scheme, Lys201 deprotonates Tyr202, which in turn abstracts a proton from the α carbon of the azoline substrate (the Tyr hydroxyl is 3.0 Å from the α carbon in the product complex). This causes E2 elimination of the anti proton from the β carbon, resulting in hydride transfer to N5 of the FMN (the β carbon and N5 are 3.3 Å apart in the product complex). In the final step of the proposed mechanism, the N1 of FMN abstracts a proton from a general base to yield FMNH2, but the structure offers no suitable candidates for a general base. We propose that a negative charge develops on N1, to give a hydroquinone anion, which is stabilized by a salt bridge to the adjacent Arg233, and thus a general base is not required (Figure 6D). In support of this proposal, a similar interaction is seen with an Arg side chain in ThcOx, perhaps indicating that this represents a general mechanism for all azole dehydrogenases. Furthermore, it was proposed (Burkhart et al., 2017) that the reaction mechanism is selective for a defined substrate stereochemistry; this is supported in our structure by the orientation of the oxazole product relative to the FMN and catalytic Tyr, which is consistent with a reaction starting from L-Ser.

The importance of the active site Tyr was illustrated by the introduction of a McbC-Y202A mutation into our pBAD Ec-McB-His expression plasmid, which led to the accumulation of a species 18 Da lighter than the unprocessed McbA peptide, consistent with the formation of a single azoline heterocycle and similar to what was previously observed in vitro (Dunbar and Mitchell, 2013) (data not shown). Attempts to purify the His-McbA-McbBCY202AD mutant synthetase complex from ΔtldD cells failed, suggesting that the stability of the complex in the absence of normal azoline oxidation is compromised.

Additional Heterocycle Binding Sites

In addition to the clearly resolved leader and the C-terminal end of pro-MccB17, inspection of the electron density map for BCD-pB17 reveals two likely heterocycle binding sites that are vacant in BCD-free complex (Figures 2 and S3E–G; Video S1). One of these sites (the “LHW pocket”) is formed between Leu17 of McbA, His13 of McbC, and Trp33 of McbD. The density here was interpreted as the oxazole-thiazole-glycine peptide OTZ39 (Figure S3E; see also Table S2, Figure S2, and STAR Methods for details on nomenclature and assignments).

The other heterocycle binding site (the “RF sandwich”) occurs between the side chains of McbA Arg21 and Phe43 from McbC. In BCD-pB17, we interpret the planar density as a thiazole-oxazole bis-heterocycle and have arbitrarily assigned it as TOZ49 (Figure S3F). This site is also occupied in BCD-pB17short and, in this case, was assigned as OTZ39, since it is the only modification present in this complex (Figure S3G). The binding mode of OTZ39 is orthogonal to that of TOZ49 in BCD-pB17, indicating that the exact path taken by the peptide can be determined by which heterocycle is bound. Based on the four fixed points for pro-MccB17 in the BCD-pB17 structure (i.e., the leader peptide and three heterocyclic moieties: OTZ39, TOZ49, and OAZ56), we were able to trace a potential path for the whole of the modified peptide (Figure 2C).

Given the non-discriminative nature of the interactions with the heterocycles, we speculate that heterocycle-binding sites may be promiscuous and capable of binding different heterocycles in different orientations, dependent on the degree of modification, and therefore the conformation of the peptide substrate. To assess if these sites are important for the correct processing of substrate, McbC Phe43, McbD Trp33, and both Leu17 and Arg21 of McbA were replaced by alanines. While McbC F43A or McbA substitutions resulted only in slight differences in heterocyclization compared to the wild-type (data not shown), introduction of an additional McbD W33A mutation to the complex significantly hampered modification (Figure S4H). It is possible that other sites capable of transiently binding heterocycles may exist that are utilized during the intermediate stages of pro-MccB17 processing which we have been unable to capture structurally.

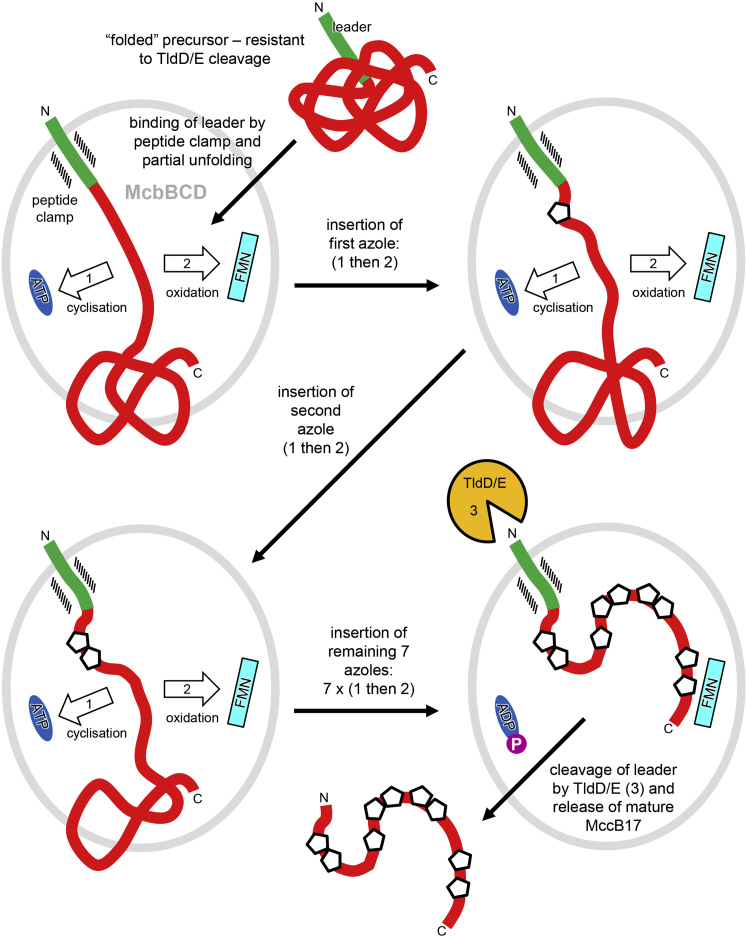

Directionality and Coordination of Synthetase Catalytic Activities: General Mechanism of McbBCD

Heterocycles are introduced sequentially from the N terminus to the C terminus of the McbA precursor peptide, with each one being fully formed before the next, since azoline intermediates have never been observed during wild-type MccB17 biosynthesis (Belshaw et al., 1998, Milne et al., 1999). This observation necessitates the repeated flipping of the peptide between the heterocyclase (McbD) and dehydrogenase (McbC) active sites, which are separated by a distance of ∼40 Å, while remaining tethered to the peptide clamp at the McbB1-McbB2 interface (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

General Mechanism of MccB17 Biosynthesis by McbBCD/TldDE

Schematic representation showing the sequence of events leading to the production of mature MccB17. First, the McbBCD synthetase binds the McbA precursor peptide via its leader peptide, then sequentially adds heterocycles to yield pro-MccB17. This involves the repeated shuttling of the precursor between McbD and McbC active centers. After the final modification, cleavage of the leader peptide by the TldD/E protease yields the mature toxin, which is then released from the complex.

The anchoring of the McbA leader peptide changes the heterocyclization and oxidation activities of McbBCD from otherwise unfavorable intermolecular reactions into more favorable tethered intramolecular reactions, where the local concentration of the substrate is increased. This will be maximal for the modification sites closer to the leader peptide, and thus these are statistically more likely to be modified first (also discussed in Ortega et al., 2015). As the modifications proceed along the peptide backbone, newly introduced heterocycles could be transiently bound in the RF sandwich and/or the LHW pocket, thereby reducing the flexibility of the C-terminal unmodified part and increasing the effective concentration of unmodified sites. Related to this, an earlier proposal suggested that the reduced substrate flexibility introduced by the modification of upstream sites potentiated the heterocyclization of the downstream sites by increasing the frequency of enzymatically productive collisions (Roy et al., 1999). However, such arguments could not apply to LynD, which exhibits the opposite directionality. Moreover, processing is still possible in the latter system where the leader peptide is provided in trans to (i.e., separate from) the core peptide (Koehnke et al., 2015). An alternative explanation for the directionality of McbA processing by McbBCD stems from the observation that the leader peptide of the precursor is recalcitrant to proteolysis (Ghilarov et al., 2017), suggesting that it is somehow inaccessible, perhaps shielded by the folding of the peptide. Upon encountering the synthetase and binding to the peptide clamp, the N terminus could be extruded from this folded state (interestingly, both McbA and PatE leader peptides were found to be helical in solution [Roy et al., 1998, Houssen et al., 2010]), followed by the remainder of the peptide, such that the modification sites become exposed sequentially from N terminus to C terminus. This process in vivo may start co-translationally while the C terminus of the nascent McbA peptide is still bound to the ribosome.

In order to check the importance of progressive heterocyclization for overall processing of a peptide, we replaced Cys41, Cys48, and Cys51 with prolines to construct single (Cys41Pro), double (Cys41Pro and Cys48Pro), and triple (Cys41Pro, Cys48Pro, and Cys51Pro) mutants as rough structural mimics of heterocycles and investigated their processing by the McbBCD complex. Removal of the OTZ39 significantly slowed down the processing (Figure S4I); however, McbBCD still introduced 7 heterocycles (presumably the first bis-heterocyclic site was not modified) after an overnight incubation. Further substitution of Cys48 (Figure S4J) slowed the reaction even more, and finally, the triple mutant (Figure S4K) was not processed by McbBCD at all. Similarly, mutation of a predicted catalytic residue of the McbC dehydrogenase (Dunbar and Mitchell, 2013, and this work) leads to the accumulation of MccB17 precursor with just one or two azolines (Cys41 and Cys48/51). This implies that the conversion of the first two azolines into aromatic moieties is strictly necessary for further modifications to occur. These findings suggest that the installation of heterocycles in McbA occurs independently of each other and is not completely blocked by mutations in the N-terminal cyclized positions as in the case of plantazolicin (Deane et al., 2016).

Recent years have seen a surge of interest in ribosomally synthesized natural products, which hold promise as a vast treasury of potential new compounds for therapeutic and biotechnological applications. Significant advances have been made in our understanding of the biosynthesis of many RiPPs, including crucial insights into the production of lantibiotics, lasso peptides, thiopeptides, and LAPs. Despite this progress, the mechanism of one of the most frequent RiPP modifications, the introduction of oxazole and thiazole moieties into peptide backbones, is still poorly understood. To date, the study of azole biosynthetic machinery has been hampered by problems with the purification of soluble proteins and their assembly into macromolecular complexes, coupled with low levels of in vitro activity and a dearth of crystal structures. This study took advantage of the fortuitous observation that an N-terminally His-tagged precursor peptide remained tightly associated with the MccB17 synthetase in E. coli cells unable to cleave off the leader sequence. This enabled the purification and subsequent crystallization of a stable McbB4C2D2 octameric complex together with its fully modified product pro-MccB17. The crystal structures of resulting complexes are the first reported ones for a multi-subunit LAP heterocyclase/dehydrogenase bound with the product, FMN and nucleotide, revealing the spatial relationships between the various subunits and bound ligands. Taken together with mutational analysis, they show that the precursor peptide is sequentially modified by shuttling between the widely spaced heterocyclase and dehydrogenase catalytic sites prior to release of the mature toxin upon cleavage of the leader peptide by the TldD/E protease.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| E. coli NEB5α | NEB | Cat#C2987 |

| E. coli BL21 (DE3) Gold | Agilent | Cat#230132 |

| E. coli BW25113 | Dr. Kirill A. Datsenko, Purdue University | Datsenko and Wanner, 2000 |

| E. coli BW25113 tldD- | Host lab | Ghilarov et al., 2017 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Gel Filtration HMW Calibration Kit | GE Healthcare | Cat#28403842 |

| TEV protease | Host lab stocks | N/A |

| TldD/E protease | Host lab stocks | Ghilarov et al., 2017 |

| HisTrap FF | GE Healthcare | Cat#17531901 |

| HiTrap Chelating HP | GE Healthcare | Cat#17040801 |

| Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 | GE Healthcare | Cat#28990944 |

| Superdex 200 Increase 5/150 | GE Healthcare | Cat#28990945 |

| MBPTrap HP 1ml | GE Healthcare | Cat#29048641 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Gel Extraction and DNA Cleanup Micro Kit | Thermo Scientific | Cat#K0832 |

| GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit | Thermo Scientific | Cat#K0503 |

| Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Kit | Thermo Scientific | Cat#F553S |

| Deposited Data | ||

| BCD-pB17-ADP-P (McbBCD complexed with processed McbA, ADP and phosphate) | RCSB PDB | 6GRG |

| BCD-pB17 (McbBCD complexed with fully processed McbA) | RCSB PDB | 6GOS |

| BCD-pB17short (McbBCD complexed with fully processed McbA 1–46) | RCSB PDB | 6GRH |

| BCD-free (apo McbBCD) | RCSB PDB | 6GRI |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Described in Table S2 | N/A | |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pBAD/His B | Thermo (Invitrogen) | V43001 |

| pBAD Ec-McB | Dr. Mikhail Metelev, Uppsala University | Metelev et al., 2013 |

| pBAD Ec-McB-His | This work | N/A |

| pBAD Ec-McB-His 1-46 | This work | N/A |

| pBAD mcbBCD and mutants used in the study | This work | N/A |

| pET28-MBP mcbA | Host lab | Ghilarov et al., 2017 |

| pET28-MBP mcbA mutants used in the study | This work | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| XDS | http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ | Kabsch, 2010 |

| AIMLESS | http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ | Evans and Murshudov, 2013 |

| XIA2 | http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ | Winter, 2010 |

| BUCCANEER | http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ | Cowtan, 2006 |

| CRANK2 | http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ | Skubák and Pannu, 2013 |

| SHELX | http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ | Sheldrick, 2008 |

| REFMAC5 | http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ | Murshudov et al., 1997 |

| MOLPROBITY | http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ | Davis et al., 2007 |

| COOT | http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ | Emsley and Cowtan, 2004 |

| CCP4MG | http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ | McNicholas et al., 2011 |

| Other | ||

| LithoLoops 0.02 mm | Molecular Dimensions | MD7-130 |

| SeedBead Kit PTFE | Hampton Research | HR2-320 |

| 96 well MRC crystallization plates | Molecular Dimensions | MD11-00-100 |

| Amicon concentrators 30 kDa cutoff | Millipore | UFC903024 |

| C18 Zip-Tips | Milllipore | ZTC18S096 |

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Konstantin Severinov (severik@waksman.rutgers.edu).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

E. coli BW25113 tldD- deficient for the protease responsible for the leader peptide cleavage and thus allowing for the full-length peptide/synthetase complex accumulation in cells is described elsewhere (Ghilarov et al., 2017). E. coli NEB5α was used for routine cloning and mutant generation. Both strains were routinely grown in LB medium at 37°C unless indicated otherwise. Ampicillin and kanamycin were used at the concentrations of 100 and 50 μg/mL respectively.

Method Details

Cloning and Site-Directed Mutagenesis

The plasmid pBAD Ec-McB, containing all the genes (mcbABCDEFG) necessary for microcin B17 production was a gift from Dr. M. Metelev (Uppsala University) and is described elsewhere (Metelev et al., 2013). A sequence encoding an N-terminal hexahistidine tag was introduced into the mcbA gene by PCR and cloning (NcoI-SmaI) using standard protocols (Thermo), resulting in the pBAD Ec-McB-His. To produce vector for shortened (1-46) peptide expression, a stop codon was introduced after Gln46 (pBAD Ec-McB-His 1-46). The mcbBCD fragment was subcloned into an empty pBAD vector (EcoRI-XhoI) to allow purification of synthetase with an N-terminal His-tag on McbB (pBAD mcbBCD). McbD and McbC mutants were constructed by overlap extension PCR based on the pBAD mcbBCD plasmid. McbA mutations were similarly constructed by overlap extension PCR and cloned (BamHI-NotI) into pET28MBP mcbA (Ghilarov et al., 2017). Sequences of primers used are listed in the Table S2.

Purification of McbBCD-pro-MccB17 Complex

For large-scale protein production, BW25113 tldD- cells freshly transformed with pBAD Ec-McB-His were grown in 1 L 2xYT cultures supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin in 2 L baffled flasks with shaking at 37°C to OD600 = 0.6, before induction of expression with 1 mM L-arabinose and transfer to 22°C for overnight growth. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 g for 10 min and resuspended in Lysis Buffer [20 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 5% (v/v) glycerol] supplemented with cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablets (Roche). Cells were lysed with the use of a cell disruptor (Constant Systems). The lysates were centrifuged for 40 min at 20000 g and passed through 0.45 μm filters before loading onto 5 mL HisTrap FF columns (GE Healthcare) and purified by FPLC, with lysis buffer containing 20 mM imidazole, used for washing. The complex was eluted with 250 mM imidazole, concentrated using Amicon-30 kDa centrifugal concentrators (Millipore) and further purified on a 10/300 GL Superdex-200 Increase gel-filtration column (GE Healthcare), eluting from the column as a single peak in GF Buffer [10 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl and 5% (v/v) glycerol]. The collected fractions were yellow due to the FMN cofactor, and these were concentrated to 10-20 mg/mL using Amicon-30 concentrators and then frozen in 0.2 mL aliquots using liquid nitrogen before storage at −80°C. Seleno-methionine (SeMet) substituted protein was produced by the metabolic inhibition method (Van Duyne et al., 1993) using supplemented M9 medium and purified as for the native protein, with the exception that 5 mM DTT was added to the gel-filtration buffer. The level of SeMet incorporation was estimated to be >90% by intact mass-spectrometry (Synapt).

Purification of McbBCD for In Vitro Experiments

For purification of hexahistidine-tagged BCD protein complexes, 1.5 L of 2xYT medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin was inoculated with 20 mL of overnight culture of E. coli BW25113 cells, transformed with a relevant plasmid (pBAD mcbBCD). The culture was grown at 37°C to an optical density OD600 of 0.6, induced with 1 mM L-arabinose and allowed to grow for further 16-18 hours at 22°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 10 min, resuspended in Lysis Buffer [20 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol (v/v), 5 mM imidazole, 2 mg/mL lysozyme] supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo) and lysed by sonication. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 30 min, lysate was filtered through a 0.22 μm nitrocellulose filter (Millipore) and applied to a pre-equilibrated 1 mL HiTrap Chelating HP column charged with NiCl2 (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with 5 volumes of Lysis Buffer followed by 25 volumes of Wash Buffer [20 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol (v/v), 10 mM imidazole]. His-tagged protein complexes were eluted with 5 mL of Elution Buffer [20 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol (v/v), 250 mM imidazole]. Fractions containing the highest protein concentrations (according to Bradford colorimetric assay (Bio-Rad)) were immediately loaded onto a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 gel-filtration column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with GF Buffer [10 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol (v/v)]. Peak fractions were collected, aliquoted, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Protein concentration was measured with DirectDetect IR-spectrometer (Millipore). McbD and McbC mutant synthetases were purified similarly.

Purification of MBP-Tagged Peptides

For purification of MBP-tagged peptides (McbA and its variants), 0.75 L of 2xYT medium containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin was inoculated with 20 mL of overnight culture of E. coli BL21(DE3) Gold (Agilent), transformed with the relevant plasmid (e.g., pET28MBP mcbA). The culture was grown at 37°C to the OD600 of 0.6, induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and allowed to grow for 3.5 hours at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 10 min, resuspended in MBP Lysis Buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 2.5% glycerol (v/v), 0.1% Triton X-100, 2 mg/mL lysozyme] supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo) and lysed by sonication. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 30 min, lysate was filtered through a 0.22 μm nitrocellulose filter (Millipore) and applied to pre-equilibrated 1 mL MBPTrap column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with 25 volumes of MBP Wash Buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl pH 7.5, 400 mM NaCl, 2.5% glycerol (v/v)]. MBP-tagged peptides were eluted from the column with 5 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) [137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4 and 1.8 mM KH2PO4] supplemented with 10 mM maltose. Fractions with the highest protein concentration, determined using Bradford colorimetric assay (Bio-Rad), were aliquoted, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Protein concentrations in purified MBP-fusion samples were measured with DirectDetect IR-spectrometer (Millipore).

Crystal Growth and Data Collection

All crystals were produced by vapor diffusion in sitting drops at 20°C. Sparse-matrix screening was used to find initial crystallization conditions using both commercial (Molecular Dimensions) and in-house screens. Drops consisting of 0.3 μl protein solution plus 0.3 μl reservoir solution were set up using an OryxNano crystallization robot (Douglas Instruments). Promising conditions were optimized using an Oryx8 robot (Douglas Instruments). Diffraction quality crystals were obtained through an iterative microseeding procedure using sitting drops comprised of 0.4 protein plus 0.2 μl reservoir plus 0.1 μl seed stock. For each step, the latter was prepared from the best crystals taken from the previous round of optimization using a SeedBead kit (Hampton). Crystals were harvested for data collection in reservoir solution supplemented with 5% (v/v) glycerol and 20% (v/v) ethylene glycol using LithoLoops (Molecular Dimensions) and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen.

For the complex with nucleotide, ATP (final concentration of 5 mM) was added to the concentrated protein solution before crystallization, and to the cryoprotectant solution before cooling.

The pre-cooled crystals were transferred robotically to the goniostat on beamline I02, I03, I04 or I24 at Diamond Light Source (Oxfordshire, UK) and maintained at −173°C with a Cryojet cryocooler (Oxford Instruments). X-ray diffraction data were recorded using a Pilatus 6M hybrid photon counting detector (Dectris), then integrated and scaled using XDS (Kabsch, 2010) via the XIA2 expert system (Winter, 2010), and merged using AIMLESS (Evans and Murshudov, 2013) All crystals belonged to space group C2 with approximate cell parameters of a = 181, b = 83 Å, c = 87 Å, β = 91° (see Table 1 for a summary of data collection statistics).

The structure of BCD-pB17 was solved at 2.4 Å resolution by SeMet SAD using the CRANK2 pipeline (Skubák and Pannu, 2013). After several attempts, it became apparent that the stoichiometry was not the expected 1:1:1 for McbB:McbC:McbD, but that there was an additional copy of McbB giving an asymmetric unit composition of McbB2CD with an estimated solvent content of 44%. SHELX (Sheldrick, 2008) located 26 sites (with occupancy > 0.25) and BUCCANEER (Cowtan, 2006) built 92% of the expected sequence, giving Rwork and Rfree values of 0.286 and 0.359, respectively, to 2.4 Å resolution. The model was then refined against a native dataset to 2.1 Å resolution in REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 1997), and completed by iterations of manual rebuilding in COOT (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) and further refinement in REFMAC5. The latter used isotropic thermal parameters and TLS group definitions obtained from the TLSMD server (http://skuld.bmsc.washington.edu/∼tlsmd/) (Painter and Merritt, 2006). Retrospective analysis revealed that of the 26 anomalously scattering sites, 24 corresponded to methionine positions in the final model and two corresponded to zinc sites, one in each copy of McbB. This model was used as the starting point for the other three structures described herein, which were refined using similar protocols. The geometries of the final models were validated with MOLPROBITY (Davis et al., 2007) before submission to the Protein Data Bank (see Table 2 for a summary of model statistics). Omit mFobs-DFcalc difference electron density maps were generated for the bound ligands using phases from the final model without the ligands after the application of small random shifts to the atomic coordinates, re-setting temperature factors, and re-refining to convergence. All structural figures were prepared using CCP4MG (McNicholas et al., 2011), and interface areas were calculated by jsPISA (Krissinel, 2015).

Table 2.

Refinement Statistics for MccB17 Synthetase Structures

| Dataset | BCD-pB17 | BCD-pB17-ADP-P | BCD-pB17short | BCD-free |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution range (Å)a | 57.39–2.10 (2.15–2.10) | 86.76–2.35 (2.41–2.35) | 57.54–1.85 (1.90–1.85) | 91.92–2.70 (2.77–2.70) |

| Reflections: working/freeb | 71,582/3,821 | 51,049/2,683 | 105,049/5,645 | 34,148/1,828 |

| Final Rworka,c | 0.172 (0.296) | 0.171 (0.311) | 0.172 (0.301) | 0.186 (0.317) |

| Final Rfreea,c | 0.212 (0.306) | 0.220 (0.346) | 0.207 (0.293) | 0.255 (0.382) |

| Estimated coordinate error (Å)d | 0.173 | 0.237 | 0.126 | 0.367 |

| RMS bond deviations (Å) | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.008 |

| RMS angle deviations (°) | 1.39 | 1.43 | 1.38 | 1.24 |

| No. of protein residues | 1,237 | 1,233 | 1,282 | 1,209 |

| Overall B factor (Å2) | 43.8 | 54.3 | 36.4 | 71.1 |

| Ramachandran plot: favored/allowed/disallowed (%)e | 97.7/2.1/0.2 | 96.8/3.1/0.1 | 98.0/1.9/0.1 | 96.6/3.1/0.3 |

| PDB accession code | 6GOS | 6GRG | 6GRH | 6GRI |

N.B. the ligand compositions of the above structures are summarized in Table S1.

Values for the outer resolution shell are given in parentheses.

The dataset was split into “working” and “free” sets consisting of 95% and 5% of the data, respectively. The free set was not used for refinement.

The R factors Rwork and Rfree are calculated as follows: R = ∑(| Fobs − Fcalc |)/∑| Fobs |, where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

Based on Rfree as calculated by REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 1997).

As calculated using MOLPROBITY (Davis et al., 2007).

Mass Spectrometry Analysis of In Vitro Heterocyclization Reactions

The MBP tag was removed from the fused peptide substrates by overnight incubation with TEV protease (30°C, 1:100 by weight, 10 mM DTT). The modification reaction of precursor peptide was carried out at 37°C in Reaction Buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl pH 7.5, 125 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 2.5% glycerol (v/v), 10 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP]. The reaction mixture (total volume 50 μL) contained 10 μM of precursor peptide and 1 μM of McbBCD modification complex (or one of the mutant McbBCD variants). Reactions were stopped by the addition of the equal volume of 1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Before MALDI-MS analysis, the reactions were desalted using ZipTip C18 tips (Millipore).

MALDI-MS mass spectra were recorded on an Ultraflextreme (Bruker Daltonics, Germany) MALDI-ToF-ToF-MS instrument in a positive ion measurement mode. The spectra were obtained in a linear mode with an accuracy of measuring the average m/z up to 1 Da. Sample aliquots were mixed on a steel target with a 30 mg/mL 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (Sigma) in 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid and 30% acetonitrile water solution.

Analytical Gel-Filtration

The SEC analysis of the McbBCD complex was performed using Superdex 200 Increase 5/150 column (GE Healthcare) in GF Buffer [10 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol] on 0.3 mL/min. Carbonic anhydrase (CA, 29 kDa), ovalbumin (O, 43 kDa), conalbumin (C, 75 kDa), aldolase (A, 158 kDa) and ferritin (F, 440 kDa) from Gel Filtration Calibration Kit (GE Healthcare) were used as calibrants. The injection volume was 20 μl for stock solutions of calibrants (concentrations as recommended by the supplier), McbBCD (3 mg/mL) and KlpBCD complexes (4 mg/mL). Detection was performed at 280 nm.

LC-MS Analysis of In Vitro Reactions

To determine which form of nucleoside phosphates is produced in the reaction catalyzed by McbBCD complex we subjected the in vitro reactions to subsequent HPLC analysis. Reactions were performed in 50 μL of Reaction Buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl pH 7.5, 125 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 2.5% glycerol (v/v), 10 mM DTT] supplemented where needed with 70 μM ATP, 7 μM of precursor peptide and 3 μM of McbBCD complex. Reactions were incubated for 10 min at 37°C, 30 μL of the reaction mixture were than uploaded to Eclipse Plus C18 Column 2.5 × 100 mm (Agilent). The mobile phase consisted of Buffer A (100 mM triethylamine (TEA)/acetate pH 6.0) and Buffer B (50% ACN in 100 mM TEA/acetate pH 6.0) at concentration varied as follows: 0% Buf B (0-2 min), 20% Buf B (7 min), 100% Buf B (8 min), 100% Buf B (13 min). Flow rate was set constant at 1 mL/min, detection was performed at 254 nm. Fractions of interest were than collected and subjected to MALDI-MS analysis to confirm the presence of the compound. In addition, the HPLC run with the mixture of chemical standards (Sigma) of three different nucleoside phosphates (ATP, ADP, AMP) was performed to determine the retention times of corresponding peaks.

Assignment of Heterocycle Binding Sites in the BCD-pB17 Structure

This structure showed very clear omit density for residues 4-22 of the leader peptide of pro-MccB17 in the peptide clamp (Figure S3B), and in the McbC active site, there was omit density for a single heterocycle flanked by one unmodified residue at its N-terminal end and three unmodified residues at its C-terminal end (Figure S3D). Given that mass spectrometry shows that the peptide is fully modified in the BCD-pB17 complex (i.e., contains nine heterocycles), this must correspond to the last heterocycle, OAZ56, which sits in a Gly-OAZ-Gly-Ser-His sequence. Indeed, the unmodified residues also fit the density well, although His side chain is disordered. Moreover, it would seem logical for the last modified heterocycle to be trapped in the McbC active site rather than any of the others. We identified two further heterocycle binding sites in this structure. At the LHW pocket, the omit density is consistent with a bis-heterocycle followed by a Gly, and the density is stronger for the second ring, suggesting it is thiazole (Figure S3E). Therefore, it must be the only oxazole-thiazole moiety present, i.e., OTZ39. At the RF clamp, there is also density for a bis-heterocycle; by elimination, it has to be one of the two thiazole-oxazole moieties (Figure S3F). Stronger omit density identifies which ring is the thiazole, and this puts the carboxy terminal end pointing toward and close to the McbC active site. Given the proximity to the latter, we chose to assign it as TOZ49 (but it could be TOZ47). Based on the above assignments we are able to trace a putative path for pro-MccB17 in this structure (Figure S3A). In the BCD-pB17short structure, only the OTZ39 bis-heterocycle is present (confirmed by mass spectrometry), but rather than occupying the LHW pocket (as in BCD-pB17) there is density in the RF sandwich, which we modeled as Gly-OTZ (Figure S3G).

Modeling of Substrate and Intermediate Complexes in the McbD Heterocyclase Reaction

Modeling of the substrate and intermediate complexes was performed manually using COOT. For simplicity we chose the terminal oxazole modification, specifically starting from a Gly-Gly-Ser-Gly peptide. The phosphorylated hemiorthoamide intermediate was modeled first because its placement could be guided by overlapping with the phosphate in the BCD-pB17-ADP-P structure. Furthermore, the necessity to place the oxygen of the heterocycle close to Pro396 and the amide nitrogen close to Thr148 (and to avoid steric clashes), naturally oriented the intermediate such that the N-terminal flanking sequence was directed toward one of the pores leading out of the active site, while the C-terminal flanking sequence was directed toward the other pore. This led to their designation as substrate entry and substrate exit channels, respectively. Since the environment of Thr148 did not provide any suitable candidates to deprotonate its β-hydroxyl, we postulate that the second base in the McbC reaction is a water molecule. In the BCD-pB17-ADP-P structure a highly coordinated water (Figure 5C) seems ideally placed, since it could be deprotonated by a conserved glutamate (Glu167). The role of Thr148 could be to help orient this water and possibly to assist in substrate binding. The substrate complex was modeled by backward extrapolation from this intermediate. In order to place the serine hydroxyl into a position that would favor nucleophilic attack on the preceding carbonyl oxygen, it was necessary to distort the Gly-Ser peptide bond significantly away from planarity. This distortion could be promoted by favorable interactions with active site residues, including Thr148, and possibly through steric constraints imposed by the enclosed active center.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

For the quantification of substrate processing by McbD active sites mutants MALDI spectra were analyzed with Bruker flexAnalysis software. For each time point relative amounts of McbA species with x azoles (Px) were calculated as areas under the peak divided by the total area. % processing was then calculated as similarly to (Dunbar et al., 2014). Three independent reactions were analyzed, with mean values of % of processing and standard deviations reported.

Data and Software Availability

Coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank with accession codes PDB: 6GRG for the BCD-pB17-ADP-P, PDB: 6GOS for BCD-pB17, PDB: 6GRH for BCD-pB17short and PDB: 6GRI for BCD-free structures respectively.

Acknowledgments

Collaborative effort between Russia and UK was supported by the RFBR-Royal Society International Exchanges Scheme (KO165410043/IE160246) and Skoltech. MALDI MS facility became available to us in the framework of the Moscow State University Development Program PNG 5.13. We acknowledge National Science Centre, Poland for financial support (grant UMO-2015/19/P/NZ1/03137 to D.G.). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 665778. Work in A.M.’s lab is also funded by the Biotechnology and Biosciences Research Council (UK) Institute Strategic Programme Grants BB/J004561/1 and BB/P012523/1. Work in K.S.’s lab was supported by Skoltech and NIH RO1 AI117210 grant to Satish A. Nair and K.S. We acknowledge Diamond Light Source for access to beamlines I02, I03, I04, and I24 under proposals MX9475 and MX13467 with support from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013) under Grant Agreement 283570 (BioStruct-X). We thank S. Bornemann, A. Truman, B. Wilkinson, M. Metelev, and F. Collin for helpful discussions and feedback on the manuscript.

Author Contributions

D.G. planned work and together with D.M.L., A.M., and K.S., designed experiments. D.G. and C.E.M.S. produced crystals. D.G., C.E.M.S., and D.M.L. collected diffraction data. D.M.L. solved and analyzed structures. D.Y.T. and J.P. generated McbBCD and McbA mutants and performed in vitro synthetase experiments. M.S. collected mass-spectrometry data. D.G. and D.M.L. wrote the manuscript with input from A.M. and K.S.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: January 17, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes seven figures, two tables, and one video and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2018.11.032.

Contributor Information

David M. Lawson, Email: david.lawson@jic.ac.uk.

Konstantin Severinov, Email: severik@waksman.rutgers.edu.

Supplemental Information

References

- Allali N., Afif H., Couturier M., Van Melderen L. The highly conserved TldD and TldE proteins of Escherichia coli are involved in microcin B17 processing and in CcdA degradation. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:3224–3231. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.12.3224-3231.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnison P.G., Bibb M.J., Bierbaum G., Bowers A.A., Bugni T.S., Bulaj G., Camarero J.A., Campopiano D.J., Challis G.L., Clardy J. Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide natural products: overview and recommendations for a universal nomenclature. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013;30:108–160. doi: 10.1039/c2np20085f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazy H., Erez E., Martz E., Pupko T., Ben-Tal N. ConSurf 2010: calculating evolutionary conservation in sequence and structure of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W529–W533. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazy H., Abadi S., Martz E., Chay O., Mayrose I., Pupko T., Ben-Tal N. ConSurf 2016: an improved methodology to estimate and visualize evolutionary conservation in macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W344–W350. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belshaw P.J., Roy R.S., Kelleher N.L., Walsh C.T. Kinetics and regioselectivity of peptide-to-heterocycle conversions by microcin B17 synthetase. Chem. Biol. 1998;5:373–384. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent A.F., Mann G., Houssen W.E., Mykhaylyk V., Duman R., Thomas L., Jaspars M., Wagner A., Naismith J.H. Structure of the cyanobactin oxidase ThcOx from Cyanothece sp. PCC 7425, the first structure to be solved at Diamond Light Source beamline I23 by means of S-SAD. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2016;72:1174–1180. doi: 10.1107/S2059798316015850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E.D., Wright G.D. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature. 2016;529:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature17042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart B.J., Hudson G.A., Dunbar K.L., Mitchell D.A. A prevalent peptide-binding domain guides ribosomal natural product biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015;11:564–570. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart B.J., Schwalen C.J., Mann G., Naismith J.H., Mitchell D.A. YcaO-dependent posttranslational amide activation: biosynthesis, structure, and function. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:5389–5456. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celniker G., Nimrod G., Ashkenazy H., Glaser F., Martz E., Mayrose I., Pupko T., Ben-Tal N. ConSurf: using evolutionary data to raise testable hypotheses about protein function. Isr. J. Chem. 2013;53:199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Cowtan K. The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:1002–1011. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906022116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C.L., Doroghazi J.R., Mitchell D.A. The genomic landscape of ribosomal peptides containing thiazole and oxazole heterocycles. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:778. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2008-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko K.A., Wanner B.L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis I.W., Leaver-Fay A., Chen V.B., Block J.N., Kapral G.J., Wang X., Murray L.W., Arendall W.B., 3rd, Snoeyink J., Richardson J.S., Richardson D.C. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W375–W383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane C.D., Burkhart B.J., Blair P.M., Tietz J.I., Lin A., Mitchell D.A. In vitro biosynthesis and substrate tolerance of the plantazolicin family of natural products. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016;11:2232–2243. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar K.L., Mitchell D.A. Insights into the mechanism of peptide cyclodehydrations achieved through the chemoenzymatic generation of amide derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:8692–8701. doi: 10.1021/ja4029507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar K.L., Melby J.O., Mitchell D.A. YcaO domains use ATP to activate amide backbones during peptide cyclodehydrations. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8:569–575. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar K.L., Chekan J.R., Cox C.L., Burkhart B.J., Nair S.K., Mitchell D.A. Discovery of a new ATP-binding motif involved in peptidic azoline biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:823–829. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans P.R., Murshudov G.N. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2013;69:1204–1214. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genilloud O., Moreno F., Kolter R. DNA sequence, products, and transcriptional pattern of the genes involved in production of the DNA replication inhibitor microcin B17. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:1126–1135. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.1126-1135.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghilarov D., Serebryakova M., Shkundina I., Severinov K. A major portion of DNA gyrase inhibitor microcin B17 undergoes an N,O-peptidyl shift during synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:26308–26318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.241315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghilarov D., Serebryakova M., Stevenson C.E.M., Hearnshaw S.J., Volkov D.S., Maxwell A., Lawson D.M., Severinov K. The origins of specificity in the microcin-processing protease TldD/E. Structure. 2017;25:1549–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser F., Pupko T., Paz I., Bell R.E., Bechor-Shental D., Martz E., Ben-Tal N. ConSurf: identification of functional regions in proteins by surface-mapping of phylogenetic information. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:163–164. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heddle J.G., Blance S.J., Zamble D.B., Hollfelder F., Miller D.A., Wentzell L.M., Walsh C.T., Maxwell A. The antibiotic microcin B17 is a DNA gyrase poison: characterisation of the mode of inhibition. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;307:1223–1234. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houssen W.E., Wright S.H., Kalverda A.P., Thompson G.S., Kelly S.M., Jaspars M. Solution structure of the leader sequence of the patellamide precursor peptide, PatE1-34. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:1867–1873. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher N.L., Hendrickson C.L., Walsh C.T. Posttranslational heterocyclization of cysteine and serine residues in the antibiotic microcin B17: distributivity and directionality. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15623–15630. doi: 10.1021/bi9913698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehnke J., Bent A.F., Zollman D., Smith K., Houssen W.E., Zhu X., Mann G., Lebl T., Scharff R., Shirran S. The cyanobactin heterocyclase enzyme: a processive adenylase that operates with a defined order of reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013;52:13991–13996. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]