Abstract

Moyamoya disease (MMD) is a type of chronic cerebrovascular occlusion disease, which frequently occurs in East Asian populations, including pediatric and adult patients, and may lead to ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, headache, epilepsy or transient ischemic attack. To date, the underlying mechanisms of MMD have remained to be fully elucidated, but certain studies have indicated that genetic factors may be an important component of its development. Cerebral angiography is the best approach for diagnosing MMD. However, with technological advances, non-invasive techniques are increasingly used to accurately evaluate MMD. MMD is commonly treated via surgery, and an increasing number of patients are benefitting from the intra- and extra-cranial revascularization. The present article provides a comprehensive review of MMD on the basis of previous research.

Keywords: moyamoya disease, cerebral stroke, revascularization, progress in research

1. Introduction

Moyamoya disease (MMD) is a type of chronic occlusive cerebrovascular disease. The pathogenetic mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated. Its major characteristic is a steno-occlusive change at the end of the internal carotid artery (ICA), middle cerebral artery (MCA) and/or proximal anterior cerebral artery (ACA), which is accompanied by the formation of smoke-like abnormal blood vessels in the base of the skull in digital subtraction angiography (DSA). In 1957, Takeuchi and Shimizu described the pathological manifestation of MMD for the first time for bilateral hypoplasia of the ICA (1). Cerebral angiography in such patients reveals smog-like blood vessels in the skull base, which was officially named MMD by Suzuki and Takaku (2) in 1969. The incidence of MMD is high in East Asian populations but low in European and North American populations (3). The clinical signs of MMD mainly include two types: Cerebral ischemia and cerebral hemorrhage. These two types of symptom differ in their distribution between pediatric and adult patients. Most of the pediatric patients present with progressive cerebral ischemia, including transient cerebral ischemic attacks and cerebral infarctions. Mental decline or seizures may be the first symptom in children. In half of the cases in adults, intracranial hemorrhage is the first symptom, while ischemic symptoms first occur in the other half (3). In recent years, large amounts of research on the diagnosis and treatment of MMD have been performed in China, Japan and South Korea. The present article provides a review of the relevant domestic and international literature for the following aspects of MMD: Diagnosis, clinical symptoms, epidemiology, genetics, radiographic evaluation, pathology and treatment methods.

2. Diagnostic criteria and clinical symptoms of MMD

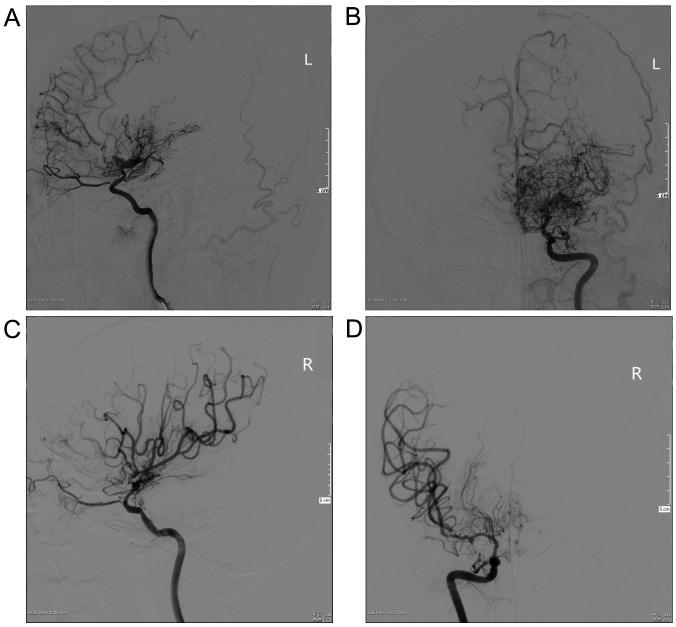

In 1996, Japan issued a guide for the diagnosis and treatment of the spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis (‘Moyamoya’ disease, MMD) (4), which suggests the following manifestations on cerebral angiography i) Stenosis or occlusion at the end of the carotid artery, the proximal ACA and/or MCA; ii) an abnormal vascular network in the vicinity of stenotic occlusion lesions in the arterial phase; and iii) the above manifestations are bilateral (Fig. 1). In 2012, the latest guidelines for the pathology and treatment of MMD on the basis of the 1997 guidelines were published in Japan; the 1997 diagnostic criteria were revised in these novel guidelines (5). In the 2012 guidelines, cerebral angiography remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of MMD with the staging performed according to angiographic findings (Table I). The novel guidelines added a staging based on scores of magnetic resonance (MR) angiography (MRA) and the diagnostic criteria are as follows: i) Stenosis or occlusion at the end of ICA and/or the initial segment of the ACA and/or MCA. ii) At least two obvious shadows of the blood flow are displayed on the same scan level at the basal ganglia region, suggesting the existence of an abnormal vascular network. iii) The above manifestations are bilateral, but bilateral lesions may be staged differently (Table II). In the evaluation system, the MRA results are simply scored and totaled. A total score of 0–1 represents stage 1, which indicates DSA I and II; a score of 2–4 represents stage 2, which indicates DSA III; a score of 5–7 represents stage 3, which indicates DSA IV; and a score of 8–10 represents stage 4, which indicates DSA V and VI.

Figure 1.

Representative cerebral angiography image of one patient with moyamoya disease. Internal carotid artery angiography: (A) Left lateral, (B) left Towne's position, (C) right lateral and (D) right Towne's position. The occlusion of the internal carotid artery was visible, and there a large number of ‘smoke-like’ vessels were present in the skull base. L, left; R, right; AO, anterior oblique views; CRA, cranial; CAU, caudal.

Table I.

Stages and cerebral angiographic findings (5).

| Stage | Cerebral angiographic findings |

|---|---|

| I | Arrowing of the carotid fork |

| II | Initiation of the moyamoya (dilated major cerebral artery and a slight moyamoya vessel network) |

| III | Intensification of the moyamoya (disappearance of the middle and anterior cerebral arteries, and thick and distinct moyamoya vessels) |

| IV | Minimization of the moyamoya (disappearance of the posterior cerebral artery, and narrowing of individual moyamoya vessels) |

| V | Reduction of the moyamoya (disappearance of all the main cerebral arteries arising from the internal carotid artery system, further minimization of the moyamoya vessels, and an increase in the collateral pathways from the external carotid artery system) |

| VI | Disappearance of the moyamoya (disappearance of the moyamoya vessels, with cerebral blood flow derived only from the external carotid artery and the vertebrobasilar artery systems) |

Table II.

Classification and scoring based on the MRA findings (5).

| A, Scoring for each artery | |

|---|---|

| Score | MRA findings |

| Internal carotid artery | |

| 0 | Normal |

| 1 | Stenosis of C1 |

| 2 | Discontinuity of the C1 signal |

| 3 | Invisible |

| Middle cerebral artery | |

| 0 | Normal |

| 1 | Stenosis of M1 |

| 2 | Discontinuity of the M1 signal |

| 3 | Invisible |

| Anterior cerebral artery | |

| 0 | Normal A2 and blood vessels distal to A2 |

| 1 | Signal decrease A2 and its distal blood vessels |

| 2 | Invisible |

| Posterior cerebral artery | |

| 0 | Normal P2 and blood vessels distal to P2 |

| 1 | Signal decrease P2 and its distal blood vessels |

| 2 | Invisible |

| B, Total score calculated individually for the right and left side | |

| MRA total score | MRA stage |

| 0–1 | 1 |

| 2–4 | 2 |

| 5–7 | 3 |

| 8–10 | 4 |

MRA, magnetic resonance angiography.

According to the new guidelines, differential diagnoses of MMD, which should be excluded, are the following underlying cerebrovascular diseases: Atherosclerosis, autoimmune diseases, meningitis, brain tumors, Down syndrome, Recklinghausen's disease, head injury and cerebrovascular damage after head irradiation. Recently, a Chinese experts' consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of MMD and MM syndrome (MMS) was published (6), which argues that the identification of MMD and MMS lacks molecular markers or other characteristic objective indicators. Instead, the identification of MMS and MMD diagnoses mainly depends on morphological characteristics and the exclusion of other diseases in which one of the main symptoms is the presents of smoke-like abnormal blood vessels, which is not feasible to perform in the clinic. In most cases, there is no significant difference in principles of treatment between MMD and MMS. For the diagnosis and treatment options for patients with suspected MMS, it is possible to refer to the guidelines for MMD.

The clinical symptoms of MMD include transient ischemic attacks, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, epilepsy, headache and cognitive dysfunction, with the incidence of each symptom varying depending on the age of the patient (5). MMD has two major symptoms: Cerebral ischemia and cerebral hemorrhage. Most pediatric patients with MMD are characterized by progressive cerebral ischemic symptoms, including transient ischemic attack and cerebral infarction, mental decline, seizures and involuntary movements. About half of all adult patients present with intracranial hemorrhage, and the other half with ischemic symptoms (3). In adult patients aged >40 years, the hemorrhagic type is more common than the ischemic type. The most common symptom for patients with ischemic MMD is dyskinesia, and an impaired consciousness is the most common symptom for those with hemorrhagic MMD (7). For each of the two types of MMD, cerebral ischemia or cerebral hemorrhage is often recurrent, but these two signs rarely occur in the same type of patient with MMD. Cerebral ischemia and transient ischemic attack are common in North American and European patients, while Asian patients often suffer from intracranial hemorrhage as the first symptom (5,8–11). However, according to certain experts, MMD is mainly ischemic in China (12).

Among pediatric patients (under 14 years old) with MMD, ~20% suffer from headache. Seol et al (13) reported that 44 of 204 (21.6%) pediatric patients with MMD complained of headaches. At present, it is thought that headache may occur due to the reduction of cerebral blood flow or cerebral blood flow reserve and diffusive cortical inhibition. Headache symptoms may be relieved by improving cerebral vascular perfusion (14).

3. Epidemiology of MMD

The incidence of MMD exhibits significant regional differences, with a high incidence in East Asia and a low incidence in other regions. According to previous studies, the prevalence of MMD is 10.5/100,000 individuals and the incidence rate is 0.94/100,000 individuals in Japan (15); in South Korea, the prevalence rate is 16.1/100,000 and the incidence rate is 2.3/100,000 individuals (16). The incidence of MMD was as low as 0.09/100,000 individuals in other regions, including North America, but it has exhibited an upward trend in the US (17). In Nanjing (China), the prevalence of MMD in the time frame of 2000–2007 was 3.92/100,000 (18). According to the most recent study, 2,430 cases of MMD have been reported in China since 1976 (12).

Worldwide, the age of onset of MMD is significantly bimodal in distribution, with a bimodal peak consisting of a major peak in the first decade of life and a moderate peak in the late 20 to 30s (4–6,12,15–19). Of note, geographic differences in sex distribution have been observed. In foreign populations, the incidence of MMD in females was reported to be higher than that in males with the male-to-female ratio ranging from 1:1.8 to 1:2.2 (5,15–17); however, the sex ratio is 1:1 in China (12,18,19).

4. Genetic factors associated with MMD

MMD has been reported to have an increased prevalence in certain ethnicities and pedigrees (20), suggesting that genetic factors may be involved. Numerous studies have indicated that genetic factors have an important role in the pathogenesis of MMD (21–23). In 2011, a whole genome-wide association study (GWAS) on 72 patients with MMD by Kamada et al (24) identified a novel susceptibility gene, Ringin Protein 213 (RNF213), and indicated that this gene is highly associated with familial MMD. In the same year, Liu et al (25) also demonstrated the genetic susceptibility of RNF213 in patients with MMD in a GWAS on 8 MMD families. Subsequent studies have indicated that the presence of a low-frequency variation of RNF213 (c.14576G>A, p.R4810K) significantly increases the risk of MMD in Asian populations (26–28). RND213 p.R4810K mutations are divided into homozygous and heterozygous mutations; MMD patients with a homozygous mutation are characterized by an earlier onset, more severe symptoms and a worse prognosis. A study by Kim et al (29) on a Korean population revealed that in MMD patients with a RNF213 p.R4810K homozygous mutation, the age was <5 years, the disease mainly manifested as cerebral infarction and patients exhibited cognitive dysfunction. To date, RNF213 p.R4810K mutations have not been detected in European patients with MMD, but certain rare variants of RNF213 have been identified (28,30,31). According to the most recent study, RNF213 mutations other than p.R4810K have an important role in Caucasians with MMD (32).

Domestic genetic studies on MMD have been performed in succession. In a study by Li et al (33) from 2010, 208 cases of Han Chinese subjects with MMD and 224 control subjects were assessed, revealing that a polymorphism of the 1,171 locus of the matrix metalloproteinase-3 gene was closely associated with MMD. In 2012, Wu et al (26) reported that in a population of 170 Han Chinese patients with MMD and 507 control subjects, a single-nucleotide polymorphism of the R4810K locus of the RNF213 gene was associated with a significantly increased risk of MMD, while that in another locus, A4399T, may be associated with hemorrhagic MMD.

5. Imaging assessment of MMD

Cerebral angiography is the gold standard for diagnosing MMD and assessing its progression. The system most widely used for its evaluation is the Suzuki staging system (2), in which the cerebral angiographic findings of MMD patients are divided into 6 stages (Table I). This staging system is based on the progression degree of smog-like blood vessels (34), and suggests that, in cases of stenotic-occlusive changes in the carotid artery system of MMD patients, a compensation of the intra-cranial cycle exists in the extracranial arterial system (35). In 2002, Mugikura et al (36) proposed a new staging system, which is a revised version of the Suzuki staging system, where re-staging is performed according to the severity of stenosis or occlusion in the MCA and the proximal ACA on cerebral angiography and the angiographic extent of their branches (Table III). The Suzuki staging system and the improved version by Mugikura et al (36) are used for staging of MMD according to the performance of the internal carotid artery. The same group has also proposed a classification involving the vertebral basilar artery in childhood MMD (37).

Table III.

Angiographic ICA staging system modified by Mugikura et al (36).

| ICA stage | Angiographic findings |

|---|---|

| I | Mild to moderate stenosis around carotid bifurcation with absent or slightly developed ICA moyamoya: Almost the entire ACA and MCA branches are opacified in antegrade fashion |

| II | Severe stenosis around carotid bifurcation or occlusion of either of proximal ACA or MCA with well-developed ICA moyamoya: The ACA and/or MCA branches are clearly defective, but at least several of the ACA or MCA branches remain opacified in antegrade fashion |

| III | Occlusion of the proximal ACA and/or MCA with well-developed ICA moyamoya: Only a few of the ACA and/or MCA branches are faintly opacified in antegrade fashion through the meshwork of ICA moyamoya |

| IV | Complete occlusion of the proximal ACA and MCA with absent or small amount of ICA moyamoya: No opacification of either ACA or MCA branches in antegrade fashion |

ACA, anterior cerebral artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; ICA, internal carotid artery.

Brain MR imaging (MRI) is able to display the brain parenchymal lesions associated with MMD, and MRA is able to reveal abnormalities consistent with cerebral angiography. In 2005, Houkin et al (38) established a scoring system based on the degree of lesions of the ICA, ACA, MCA and posterior cerebral artery on MRA and claimed that this system was as suitable as the Suzuki staging system. This MRA scoring system was added to the 2012 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of MMD in Japan (5). Ryoo et al (39) reported that high-resolution nuclear MRI is able to effectively distinguish between MMD and atherosclerosis based on differences in cerebral blood vessels.

Assessment of cerebral hemodynamics and the brain metabolism level is also an important part of the imaging assessment of patients with MMD. This assessment provides a more objective and realistic indicator for the selection and efficacy assessment of surgery regimens for MMD. In the current assessment of brain metabolism, positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography may be employed for detection. For the assessment of cerebral hemodynamics, computed tomography perfusion imaging and MR perfusion-weighted imaging may be applied (40–45).

6. Pathology of MMD

The basic pathology of MMD mainly includes intimal fibrous hyperplasia of the intracranial arterial stenosis, irregular proliferation of the inner elastic layer, thinning of the middle layer of the vessel wall and reduction of the outer diameter of the blood vessel (3,46). A high-resolution MRI cohort study indicated that most patients with MMD had a contractile remodeling at the distal end of the ICA and a long concentric enhancement (39). This result is consistent with the thickening of the arterial intima and the thinning of the tunica media detected by vascular pathology (47).

Growing evidence supports the notion that MMD is essentially a vascular intimal hyperplastic disease. Histopathological analysis of the distal carotid artery indicated that the hyperplasia occurs in arterial wall smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells (48), and that the endometrial thickening caused by fibrous cell hyperplasia of the arterial intima is the cause of arterial stenosis and occlusion (3). Guo et al (49) reported that arterial stenosis and occlusion of familial MMD may be due to smooth muscle tissue hyperplasia associated with a mutation in the actin, α2, smooth muscle, aorta gene. Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) have an important role in maintaining blood flow in the infarct region of patients with ischemic stroke (50). Kim et al (51) reported that the angiogenic function of EPCs in patients with MMD is defective, which may be the cause of abnormal angiogenesis in patients with MMD. Lee et al (52) indicated that the expression of retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 was epigenetically inhibited in endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs) from patients with MMD, which may have a key role in the functional impairment of ECFCs.

Increased levels of multiple autoimmune antibodies in patients with MMD suggest that the immune response may be involved in the pathogenesis of MMD. Kim et al (53) identified that the levels of thyroid auto-antibodies were elevated in numerous patients with MMD. Sigdel et al (54) used protein chip technology to assess patients with MMD and identified a variety of auto-antibodies associated with MMD. In addition, numerous studies have indicated that multiple cytokines, including vascular endothelial growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor, cellular retinoic acid binding protein 1 and granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor, were present in the plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, dura mater, as well as arachnoid and superficial temporal artery of patients with MMD (46,55–58). Furthermore, chronic arterial inflammation caused by immune responses has been recognized as an important driver of the progression of MMD (54). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the involvement of the immune response in MMD have remained to be fully elucidated.

7. Treatment of MMD

At present, no evidence suggesting that drug treatment is able to delay or even reverse the progression of MMD is available. The current drug treatment for in MMD only targets its clinical symptoms, including ischemia and hemorrhage, by exerting anti-coagulant or hemostatic effects. The Japanese guidelines from 2012 recommend the use of anti-platelet aggregation drugs for the treatment of ischemic MMD (5), but the risk of bleeding remains.

Regarding the occurrence of ischemic stroke in patients with ischemic MMD, the preventive effect of surgical revascularization treatment has been clinically demonstrated (35,59–62). However, intra- and extra-cranial revascularization for the prevention of recurrence of bleeding in patients with hemorrhagic MMD is controversial. Duan et al (19) performed a review of patients with MMD and noted that the probability of recurrence of cerebral ischemia or cerebral hemorrhage in patients subjected to surgical re-vascularization was significantly lower than that in patients who received conservative treatment. A study on Japanese adults with MMD from 2010 defined the primary and secondary end points as all adverse events and rebleeding attacks, respectively. It was reported that for patients with hemorrhagic MMD, the difference between the surgical and non-surgical group was statistically significant, and a Kaplan-Meier analysis suggested that the collateral circulation provided by the surgery was able to prevent recurrent bleeding (63). Further studies have provided similar results (64,65). Therefore, the prevailing opinion is that patients with ischemic or hemorrhagic MMD should receive surgical treatment (66).

Surgical revascularization of MMD includes 3 types: Direct revascularization, indirect revascularization and combined revascularization. In the direct revascularization surgery, the most common method is superficial temporal artery-MCA anastomosis. When ischemic hypoperfusion occurs in the blood supply area of the ACA or posterior cerebral artery, the superficial temporal artery-ACA or occipital artery-posterior cerebral artery anastomosis may be adopted (67,68). Indirect revascularization is a surgery based on a variety of tissues used as a source of blood supply, mainly including encephalomyosynangiosis, encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis, multiple burr hole surgery, encephaloduromyoarteriosynangiosis, encephaloduromyoarteriopericranial synangiosis and omental transplantation (69–74). Combined revascularization refers to the combined use of the former two revascularization techniques. A recent meta-analysis revealed that direct or combined revascularization surgery is better for unstable adult patients with MMD characterized by symptomatic or hemodynamic instability (75).

During the peri-operative period, it is necessary to actively prevent the occurrence of ischemic complications, particularly in pediatric patients with MMD (76). Most patients undergoing direct vascular bypass surgery in the acute phase may suffer from transient neurological dysfunction due to changes in hemodynamics. The brain tissue hypoperfusion caused by changes in hemodynamics is mainly caused by the competition between the blood flow from the superficial temporal artery bridge blood vessels and the blood flow from the existing collateral circulation, due to damage to the cerebrovascular auto-regulation function (77). Studies have indicated that ~1/4 of patients with direct bypass may suffer from high perfusion symptoms, and there was a high risk of high perfusion in adult patients with MMD and patients with hemorrhagic MMD (78). A PET study indicated that cerebral blood flow and cerebral blood volume (CBV) increased, while the oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) decreased under high perfusion (71). In terms of hemodynamics, the increase in pre-operative CBV or OEF is a risk factor for post-operative high perfusion (79,80). It is necessary to closely monitor the blood pressure fluctuations in patients during the peri-operative period, in order to prevent the occurrence of low or excessive perfusion.

8. Summary

The pathogenesis of MMD still remains to be fully elucidated. The worldwide incidence of MMD is low, but it has a higher incidence in Asian countries. MMD is an important cause of cerebral stroke in pediatric and adult patients. In order to avoid the occurrence of severe neurological symptoms, a definitive diagnosis of MMD must be made as soon as possible, so that treatment may be rapidly performed and a relatively good mid- and long-term prognosis may be achieved. Surgery remains an important treatment for MMD, but an individualized clinical treatment strategy should be selected according to the condition of each patient. With the increasing number of genetic studies, novel treatment approaches for MMD at the genetic level may be developed in the future.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

HZ was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. LZ collected data for the current review. LF designed and revised this review.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Takeuchi K, Shimizu K. Hypoplasia of the bilateral internal carotid arteries. Brain Nerve. 1957;9:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suzuki J, Takaku A. Cerebrovascular ‘moyamoya’ disease. Disease showing abnormal net-like vessels in base of brain. Arch Neurol. 1969;20:288–299. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1969.00480090076012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuroda S, Houkin K. Moyamoya disease: Current concepts and future perspectives. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1056–1066. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukui M. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis (moyamoya' disease). Research committee on spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis (moyamoya disease) of the ministry of health and welfare, Japan. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1997;99(Suppl 2):S238–S240. doi: 10.1016/S0303-8467(97)00082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Research Committee on the Pathology and Treatment of Spontaneous Occlusion of the Circle of Willis; Health Labour Sciences Research Grant for Research on Measures for Infractable Diseases: Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of moyamoya disease (spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis) Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2012;52:245–266. doi: 10.2176/nmc.52.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Syndrome Cecgodatomdam and Committee TNCoHS PatoissecoS: Chinese expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of moyamoya disease and moyamoya syndrome (2017) Chin J Neurosurg. 2017;6:541–547. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Research on intractable diseases of the Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, Japan: Recommendations for the management of moyamoya disease: A statement from research committee on spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis (moyamoya disease) Surgery for Cerebral Stroke. 2009;37:321–337. doi: 10.2335/scs.37.321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piao J, Wu W, Yang Z, Yu J. Research progress of moyamoya disease in children. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12:566–575. doi: 10.7150/ijms.11719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith ER, Scott RM. Spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis in children: Pediatric moyamoya summary with proposed evidence-based practice guidelines. A review. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2012;9:353–360. doi: 10.3171/2011.12.PEDS1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan N, Achrol AS, Guzman R, Burns TC, Dodd R, Bell-Stephens T, Steinberg GK. Sex differences in clinical presentation and treatment outcomes in Moyamoya disease. Neurosurgery. 2012;71:587–593. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182600b3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim T, Lee H, Bang JS, Kwon OK, Hwang G, Oh CW. Epidemiology of moyamoya disease in Korea: Based on national health insurance service data. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2015;57:390–395. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2015.57.6.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou XW, Wang JZ, Ma Y. Literature review and current situation of domestic moyamoya disease. Chin J Pract Nerv Dis. 2017;20:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seol HJ, Wang KC, Kim SK, Hwang YS, Kim KJ, Cho BK. Headache in pediatric moyamoya disease: Review of 204 consecutive cases. J Neurosurg. 2005;103(Suppl 5):S439–S442. doi: 10.3171/ped.2005.103.5.0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okada Y, Kawamata T, Kawashima A, Yamaguchi K, Ono Y, Hori T. The efficacy of superficial temporal artery-middle cerebral artery anastomosis in patients with moyamoya disease complaining of severe headache. J Neurosurg. 2012;116:672–679. doi: 10.3171/2011.11.JNS11944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baba T, Houkin K, Kuroda S. Novel epidemiological features of moyamoya disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:900–904. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.130666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahn IM, Park DH, Hann HJ, Kim KH, Kim HJ, Ahn HS. Incidence, prevalence, and survival of moyamoya disease in Korea: A nationwide, population-based study. Stroke. 2014;45:1090–1095. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kainth D, Chaudhry SA, Kainth H, Suri FK, Qureshi AI. Epidemiological and clinical features of moyamoya disease in the USA. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;40:282–287. doi: 10.1159/000345957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miao W, Zhao PL, Zhang YS, Liu HY, Chang Y, Ma J, Huang QJ, Lou ZX. Epidemiological and clinical features of Moyamoya disease in Nanjing, China. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duan L, Bao XY, Yang WZ, Shi WC, Li DS, Zhang ZS, Zong R, Han C, Zhao F, Feng J. Moyamoya disease in China: Its clinical features and outcomes. Stroke. 2012;43:56–60. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.621300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mineharu Y, Takenaka K, Yamakawa H, Inoue K, Ikeda H, Kikuta KI, Takagi Y, Nozaki K, Hashimoto N, Koizumi A. Inheritance pattern of familial moyamoya disease: Autosomal dominant mode and genomic imprinting. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:1025–1029. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.096040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikeda H, Sasaki T, Yoshimoto T, Fukui M, Arinami T. Mapping of a familial moyamoya disease gene to chromosome 3p24.2-p26. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:533–537. doi: 10.1086/302243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamauchi T, Tada M, Houkin K, Tanaka T, Nakamura Y, Kuroda S, Abe H, Inoue T, Ikezaki K, Matsushima T, Fukui M. Linkage of familial moyamoya disease (spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis) to chromosome 17q25. Stroke. 2000;31:930–935. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.4.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakurai K, Horiuchi Y, Ikeda H, Ikezaki K, Yoshimoto T, Fukui M, Arinami T. A novel susceptibility locus for moyamoya disease on chromosome 8q23. J Hum Genet. 2004;49:278–281. doi: 10.1007/s10038-004-0143-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamada F, Aoki Y, Narisawa A, Abe Y, Komatsuzaki S, Kikuchi A, Kanno J, Niihori T, Ono M, Ishii N, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies RNF213 as the first Moyamoya disease gene. J Hum Genet. 2011;56:34–40. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu W, Morito D, Takashima S, Mineharu Y, Kobayashi H, Hitomi T, Hashikata H, Matsuura N, Yamazaki S, Toyoda A, et al. Identification of RNF213 as a susceptibility gene for moyamoya disease and its possible role in vascular development. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu Z, Jiang H, Zhang L, Xu X, Zhang X, Kang Z, Song D, Zhang J, Guan M, Gu Y. Molecular analysis of RNF213 gene for moyamoya disease in the Chinese Han population. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyatake S, Miyake N, Touho H, Nishimura-Tadaki A, Kondo Y, Okada I, Tsurusaki Y, Doi H, Sakai H, Saitsu H, et al. Homozygous c.14576G>A variant of RNF213 predicts early-onset and severe form of moyamoya disease. Neurology. 2012;78:803–810. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318249f71f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cecchi AC, Guo D, Ren Z, Flynn K, Santos-Cortez RL, Leal SM, Wang GT, Regalado ES, Steinberg GK, Shendure J, et al. RNF213 rare variants in an ethnically diverse population with Moyamoya disease. Stroke. 2014;45:3200–3207. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim EH, Yum MS, Ra YS, Park JB, Ahn JS, Kim GH, Goo HW, Ko TS, Yoo HW. Importance of RNF213 polymorphism on clinical features and long-term outcome in moyamoya disease. J Neurosurg. 2016;124:1221–1227. doi: 10.3171/2015.4.JNS142900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi H, Brozman M, Kyselová K, Viszlayová D, Morimoto T, Roubec M, Školoudík D, Petrovičová A, Juskanič D, Strauss J, et al. RNF213 rare variants in slovakian and czech moyamoya disease patients. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raso A, Biassoni R, Mascelli S, Nozza P, Ugolotti E, DI Marco E, DE Marco P, Merello E, Cama A, Pavanello M, Capra V. Moyamoya vasculopathy shows a genetic mutational gradient decreasing from East to West. J Neurosurg Sci. 2016 doi: 10.23736/S0390-5616.16.03900-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guey S, Kraemer M, Hervé D, Ludwig T, Kossorotoff M, Bergametti F, Schwitalla JC, Choi S, Broseus L, Callebaut I, et al. Rare RNF213 variants in the C-terminal region encompassing the RING-finger domain are associated with moyamoya angiopathy in Caucasians. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:995–1003. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2017.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H, Zhang ZS, Liu W, Yang WZ, Dong ZN, Ma MJ, Han C, Yang H, Cao WC, Duan L. Association of a functional polymorphism in the MMP-3 gene with Moyamoya disease in the Chinese Han population. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;30:618–625. doi: 10.1159/000319893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hishikawa T, Tokunaga K, Sugiu K, Date I. Assessment of the difference in posterior circulation involvement between pediatric and adult patients with moyamoya disease. J Neurosurg. 2013;119:961–965. doi: 10.3171/2013.6.JNS122099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujimura M, Tominaga T. Lessons learned from moyamoya disease: Outcome of direct/indirect revascularization surgery for 150 affected hemispheres. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2012;52:327–332. doi: 10.2176/nmc.52.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mugikura S, Takahashi S, Higano S, Shirane R, Sakurai Y, Yamada S. Predominant involvement of ipsilateral anterior and posterior circulations in moyamoya disease. Stroke. 2002;33:1497–1500. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000016828.62708.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mugikura S, Takahashi S, Higano S, Shirane R, Kurihara N, Furuta S, Ezura M, Takahashi A. The relationship between cerebral infarction and angiographic characteristics in childhood moyamoya disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:336–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Houkin K, Nakayama N, Kuroda S, Nonaka T, Shonai T, Yoshimoto T. Novel magnetic resonance angiography stage grading for moyamoya disease. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;20:347–354. doi: 10.1159/000087935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryoo S, Cha J, Kim SJ, Choi JW, Ki CS, Kim KH, Jeon P, Kim JS, Hong SC, Bang OY. High-resolution magnetic resonance wall imaging findings of Moyamoya disease. Stroke. 2014;45:2457–2460. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.004761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.So Y, Lee HY, Kim SK, Lee JS, Wang KC, Cho BK, Kang E, Lee DS. Prediction of the clinical outcome of pediatric moyamoya disease with postoperative basal/acetazolamide stress brain perfusion SPECT after revascularization surgery. Stroke. 2005;36:1485–1489. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000170709.95185.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka Y, Nariai T, Nagaoka T, Akimoto H, Ishiwata K, Ishii K, Matsushima Y, Ohno K. Quantitative evaluation of cerebral hemodynamics in patients with moyamoya disease by dynamic susceptibility contrast magnetic resonance imaging-comparison with positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:291–300. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Federau C, Christensen S, Zun Z, Park SW, Ni W, Moseley M, Zaharchuk G. Cerebral blood flow, transit time, and apparent diffusion coefficient in moyamoya disease before and after acetazolamide. Neuroradiology. 2017;59:5–12. doi: 10.1007/s00234-016-1766-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen JC, Liu B, Li ZW, Yu JS, He Y, Chen RD. Using CT perfusion imaging to evaluate the effect of STA-MCA bypass on hemorrhagic moyamoya disease. Chin J Neurosurg. 2009;25:537–540. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang B, Zhou Q, Yao ZW, Li ZY, He GW. CTP and PWI in assessment of the effect of cerebral revascularization for moyamoya disease. Chin Comput Med imag. 2015;21:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakagawara J. Trends in Cerebrovascular Surgery. Springer: 2016. Reconsideration of hemodynamic cerebral ischemia using recent PET/SPECT studies; pp. 99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takagi Y, Kikuta K, Nozaki K, Fujimoto M, Hayashi J, Imamura H, Hashimoto N. Expression of hypoxia-inducing factor-1 alpha and endoglin in intimal hyperplasia of the middle cerebral artery of patients with Moyamoya disease. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:338–345. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000249275.87310.FF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takagi Y, Kikuta K, Nozaki K, Hashimoto N. Histological features of middle cerebral arteries from patients treated for Moyamoya disease. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2007;47:1–4. doi: 10.2176/nmc.47.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chmelova J, Kolar Z, Prochazka V, Curik R, Dvorackova J, Sirucek P, Kraft O, Hrbac T. Moyamoya disease is associated with endothelial activity detected by anti-nestin antibody. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2010;154:159–162. doi: 10.5507/bp.2010.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo DC, Papke CL, Tran-Fadulu V, Regalado ES, Avidan N, Johnson RJ, Kim DH, Pannu H, Willing MC, Sparks E, et al. Mutations in smooth muscle alpha-actin (ACTA2) cause coronary artery disease, stroke, and Moyamoya disease, along with thoracic aortic disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:617–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumar AH, Caplice NM. Clinical potential of adult vascular progenitor cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1080–1087. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.198895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim JH, Jung JH, Phi JH, Kang HS, Kim JE, Chae JH, Kim SJ, Kim YH, Kim YY, Cho BK, et al. Decreased level and defective function of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in children with moyamoya disease. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:510–518. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee JY, Moon YJ, Lee HO, Park AK, Choi SA, Wang KC, Han JW, Joung JG, Kang HS, Kim JE, et al. Deregulation of retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 leads to defective angiogenic function of endothelial colony-forming cells in pediatric moyamoya disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:1670–1677. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim SJ, Heo KG, Shin HY, Bang OY, Kim GM, Chung CS, Kim KH, Jeon P, Kim JS, Hong SC, Lee KH. Association of thyroid autoantibodies with moyamoya-type cerebrovascular disease: A prospective study. Stroke. 2010;41:173–176. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.562264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sigdel TK, Shoemaker LD, Chen R, Li L, Butte AJ, Sarwal MM, Steinberg GK. Immune response profiling identifies autoantibodies specific to Moyamoya patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sakamoto S, Kiura Y, Yamasaki F, Shibukawa M, Ohba S, Shrestha P, Sugiyama K, Kurisu K. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in dura mater of patients with moyamoya disease. Neurosurg Rev. 2008;31:77–81. doi: 10.1007/s10143-007-0102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Furuno A, Watari K, Nakamura M, Fukunaga Y, Jung JH, Ono M. A natural anti-inflammatory enone fatty acid inhibits angiogenesis by attenuating nuclear factor-κB signaling in vascular endothelial cells. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:493–501. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2010.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kang HS, Kim JH, Phi JH, Kim YY, Kim JE, Wang KC, Cho BK, Kim SK. Plasma matrix metalloproteinases, cytokines and angiogenic factors in moyamoya disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:673–678. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.191817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jeon JS, Ahn JH, Moon YJ, Cho WS, Son YJ, Kim SK, Wang KC, Bang JS, Kang HS, Kim JE, Oh CW. Expression of cellular retinoic acid-binding protein-I (CRABP-I) in the cerebrospinal fluid of adult onset moyamoya disease and its association with clinical presentation and postoperative haemodynamic change. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:726–731. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-305953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fung LW, Thompson D, Ganesan V. Revascularisation surgery for paediatric moyamoya: A review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:358–364. doi: 10.1007/s00381-004-1118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guzman R, Lee M, Achrol A, Bell-Stephens T, Kelly M, Do HM, Marks MP, Steinberg GK. Clinical outcome after 450 revascularization procedures for moyamoya disease. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:927–935. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.JNS081649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hallemeier CL, Rich KM, Grubb RL, Jr, Chicoine MR, Moran CJ, Cross DT, III, Zipfel GJ, Dacey RG, Jr, Derdeyn CP. Clinical features and outcome in North American adults with moyamoya phenomenon. Stroke. 2006;37:1490–1496. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000221787.70503.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scott RM, Smith JL, Robertson RL, Madsen JR, Soriano SG, Rockoff MA. Long-term outcome in children with moyamoya syndrome after cranial revascularization by pial synangiosis. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(2 Suppl Pediatrics):S142–S149. doi: 10.3171/ped.2004.100.2.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miyamoto S, Yoshimoto T, Hashimoto N, Okada Y, Tsuji I, Tominaga T, Nakagawara J, Takahashi JC, JAM Trial Investigators Effects of extracranial-intracranial bypass for patients with hemorrhagic moyamoya disease: Results of the Japan Adult Moyamoya Trial. Stroke. 2014;45:1415–1421. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wan M, Duan L. Recent progress in hemorrhagic moyamoya disease. Br J Neurosurg. 2015;29:189–191. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2014.976177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang Z, Ding X, Men W, Zhang D, Zhao Y, Wang R, Wang S, Zhao J. Clinical features and outcomes in 154 patients with haemorrhagic moyamoya disease: Comparison of conservative treatment and surgical revascularization. Neurol Res. 2015;37:886–892. doi: 10.1179/1743132815Y.0000000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee SU, Oh CW, Kwon OK, Bang JS, Ban SP, Byoun HS, Kim T. Surgical treatment of adult moyamoya disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2018;20:22. doi: 10.1007/s11940-018-0511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kawashima A, Kawamata T, Yamaguchi K, Hori T, Okada Y. Successful superficial temporal artery-anterior cerebral artery direct bypass using a long graft for moyamoya disease. Neurosurgery. 2010;67(3 Suppl Operative):ons145–ons149. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000382975.86267.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hayashi T, Shirane R, Tominaga T. Additional surgery for postoperative ischemic symptoms in patients with moyamoya disease: The effectiveness of occipital artery-posterior cerebral artery bypass with an indirect procedure: Technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:E195–E196. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000336311.60660.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karasawa J, Kikuchi H, Furuse S, Sakaki T, Yoshida Y. A surgical treatment of ‘moyamoya’ disease ‘encephalo-myo synangiosis’. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1977;17:29–37. doi: 10.2176/nmc.17pt1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Matsushima Y, Aoyagi M, Koumo Y, Takasato Y, Yamaguchi T, Masaoka H, Suzuki R, Ohno K. Effects of encephalo-duro-arterio-synangiosis on childhood Moyamoya patients. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1991;31:708–714. doi: 10.2176/nmc.31.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Endo M, Kawano N, Miyaska Y, Yada K. Cranial burr hole for revascularization in moyamoya disease. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:180–185. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.71.2.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kinugasa K, Mandai S, Tokunaga K, Kamata I, Sugiu K, Handa A, Ohmoto T. Ribbon enchephalo-duro-arterio-myo-synangiosis for moyamoya disease. Surg Neurol. 1994;41:455–461. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kuroda S, Houkin K, Ishikawa T, Nakayama N, Iwasaki Y. Novel bypass surgery for moyamoya disease using pericranial flap: Its impacts on cerebral hemodynamics and long-term outcome. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:1093–1101. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000369606.00861.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Karasawa J, Kikuchi H, Kawamura J, Sakai T. Intracranial transplantation of the omentum for cerebrovascular moyamoya disease: A two-year follow-up study. Surg Neurol. 1980;14:444–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim H, Jang DK, Han YM, Sung JH, Park IS, Lee KS, Yang JH, Huh PW, Park YS, Kim DS, Han KD. Direct bypass versus indirect bypass in adult moyamoya angiopathy with symptoms or hemodynamic instability: A meta-analysis of comparative studies. World Neurosurg. 2016;94:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iwama T, Hashimoto N, Yonekawa Y. The relevance of hemodynamic factors to perioperative ischemic complications in childhood moyamoya disease. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:1120–1126. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199606000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mukerji N, Cook DJ, Steinberg GK. Is local hypoperfusion the reason for transient neurological deficits after STA-MCA bypass for moyamoya disease? J Neurosurg. 2015;122:90–94. doi: 10.3171/2014.8.JNS132413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fujimura M, Mugikura S, Kaneta T, Shimizu H, Tominaga T. Incidence and risk factors for symptomatic cerebral hyperperfusion after superficial temporal artery-middle cerebral artery anastomosis in patients with moyamoya disease. Surg Neurol. 2009;71:442–447. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.07.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaku Y, Iihara K, Nakajima N, Kataoka H, Fukuda K, Masuoka J, Fukushima K, Iida H, Hashimoto N. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism of hyperperfusion after cerebral revascularization in patients with moyamoya disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:2066–2075. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Uchino H, Kuroda S, Hirata K, Shiga T, Houkin K, Tamaki N. Predictors and clinical features of postoperative hyperperfusion after surgical revascularization for moyamoya disease: A serial single photon emission CT/positron emission tomography study. Stroke. 2012;43:2610–2616. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.654723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.