Short abstract

The neuropeptide of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) plays critical roles in chronic pain, especially in migraine. Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization studies have shown that CGRP and its receptors are expressed in cortical areas including pain perception-related prefrontal anterior cingulate cortex. However, less information is available for the functional roles of CGRP in cortical regions such as the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). Recent studies have consistently demonstrated that long-term potentiation is a key cellular mechanism for chronic pain in the ACC. In the present study, we used 64-electrode array field recording system to investigate the effect of CGRP on excitatory transmission in the ACC. We found that CGRP induced potentiation of synaptic transmission in a dose-dependently manner (1, 10, 50, and 100 nM). CGRP also recruited inactive circuit in the ACC. An application of the calcitonin receptor-like receptor antagonist CGRP8-37 blocked CGRP-induced chemical long-term potentiation and the recruitment of inactive channels. CGRP-induced long-term potentiation was also blocked by N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist AP-5. Consistently, the application of CGRP increased NMDA receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents. Finally, we found that CGRP-induced long-term potentiation required the activation of calcium-stimulated adenylyl cyclase subtype 1 (AC1) and protein kinase A. Genetic deletion of AC1 using AC1−/− mice, an AC1 inhibitor NB001 or a protein kinase A inhibitor KT5720, all reduced or blocked CGRP-induced potentiation. Our results provide direct evidence that CGRP may contribute to synaptic potentiation in important physiological and pathological conditions in the ACC, an AC1 inhibitor NB001 may be beneficial for the treatment of chronic headache.

Keywords: Calcitonin gene-related peptide, long-term potentiation, MED64, adenylyl cyclase 1, NMDA receptor, migraine, pain, mice

Introduction

Headache is a major health problem, and it caused many unwanted health problems such as stress and sleep deprivation. Migraine is common types of primary headaches disorder characterized by recurrent headaches, which is present with pulsing head pain, nausea, vomiting, photophobia (sensitivity to light), and phonophobia (sensitivity to sound).1,2 There are two main theories of migraine pathogenesis that are the vascular theory and the central neuronal theory. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms are not fully known.3 Recent clinical studies show that the neuropeptide calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) plays a key role in migraine. It is known that CGRP is released by the activation of primary sensory neurons in the trigeminal vascular system in humans. The concentrations of CGRP have been reported to be elevated in both saliva and plasma drawn during chronic migraine.3,4 Furthermore, administration of CGRP (i.v.) is able to induce migraine.5 Clinical studies have demonstrated that CGRP receptor antagonists are effective for treating migraine.4,6,7

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is a critical cortical region for pain perception and emotion. Neurons in the ACC are activated by noxious sensory stimuli and inhibition of excitatory transmission in the ACC neurons produced analgesic effects in different animal models of chronic pain.8–11 Considerable clinical evidence suggests that the ACC is also involved in the modulation of migraine processing.2,12 Human brain imaging studies suggest that ACC activities are increased during or after chronic migraine.13,14 Excitatory neurotransmitters in the ACC and insula are altered in migraine patients during their interictal period.15 In our recent animal model of migraine, we found that activity-induced ACC long-term potentiation (LTP) was affected (Liu et al., unpublished). Although CGRP and its receptors have been reported in the ACC, less is known if CGRP may affect synaptic transmission. In the present experiments, we used a 64-channel multielectrode array recording system (MED64) to record the effects of CGRP on synaptic transmission and cortical network in the ACC of adult mice.

Materials and methods

Animals

Adult male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Xi’an Jiaotong University (8–12 weeks old). AC1−/− mice were a gift from Dr. Daniel R. Storm (University of Washington, Seattle, WA)16 and were maintained on a C57BL/6 background. All mice were randomly housed in corncob-lined plastic cages under an artificial 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on 9 a.m. to 9 p.m.) with food and water provided ad libitum, at least one week before carrying out experiments. Animal protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of Xi’an Jiaotong University.

Brain slice preparation

Coronal brain slices (300 μm) containing the ACC from C57BL/6 mice or AC1−/− mice were prepared using standard methods.17,18 Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 1%–2% isoflurane and sacrificed by decapitation. The whole brain was quickly removed from the skull and submerged in the ice-cold oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM) 124 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgSO4, 25 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, and 10 glucose, pH 7.3–7.4. After cooling for a short time, the whole brain was trimmed for an appropriate part to glue onto the cutting staged tissue slicer of a Leica VT1200S Vibratome. Slices were transferred to a submerged recovery chamber with oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) ACSF at room temperature for at least 1 h.

Chemicals and drug application

α-CGRP was purchased from BACHEM AG (Bubendorf, Switzerland). CGRP8-37 (CGRP1 receptor antagonist), AP-5 (D (-)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid), NMDA receptor antagonist), and KT5720 (protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitor) were obtained from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK). NB001 was provided by NeoBrain Pharmac Inc (Canada). Drugs were prepared as stock solutions for frozen aliquots at −20°C. They were diluted from the stock solution to the final desired concentration in the ACSF before being applied to the perfusion solution.

Field potential recording

Preparation of the multi-electrode array

The MED64 recording system (Panasonic, Japan) was used for extracellular field potential recordings. There is an array of 64 planar microelectrodes in the MED64 probe (P515A, Panasonic, Japan), arranged in an 8 × 8 pattern, with an interpolar distance of 150 μm. The surface of the MED64 probe was treated with 0.1% polyethyleneimine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO; P-3143) in 25 mmol/L borate buffer (pH 8.4) overnight at room temperature before experiments. Then the surface of probe was rinsed three times with sterile distilled water.17,19

Electrophysiological recordings

After incubation, one slice containing the ACC was transferred to the prepared MED64 probe and perfused with oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) ACSF at 28–30°C and maintained at a 2 ml/min flow rate. The slice was positioned on the MED64 probe in such a way that the different layers of the ACC were entirely covered by the whole array of the electrodes, and then a fine-mesh anchor was placed on the slice to ensure its stabilization during the experiments. One of the channels located in the layer V of the ACC was chosen as the stimulation site, from which the best synaptic responses can be induced in the surrounding recording channels. Slices were kept in the recording chamber for at least 1 h before the start of experiments. Bipolar constant current pulse stimulation (1–10 µA, 0.2 ms) was applied to the stimulation channel, and the intensity was adjusted so that a half-maximal field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSP) was elicited in the channels closest to the stimulation site. The channels with fEPSPs were considered as active channels and their fEPSPs responses were sampled every 1 min and averaged every 5 min. The parameter of “slope” indicated the averaged slope of each fEPSP recorded by activated channels. Stable baseline responses were first recorded until the baseline response variation less than 5% in most of the active channels within 0.5 h. After recording stable baseline, the drug of CGRP was applied 30 min before washout in the C57BL/6 and AC1−/− mice. AP-5 or KT5720 was applied 30 min before CGRP applied and washed out together with CGRP.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recording

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were based on our previous studies.18,20 Experiments were performed in a recording chamber on the stage of an Olympus BX51W1 microscope equipped with infrared differential interference contrast optics for visualization. Excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were recorded in the voltage-clamp configuration, and the resting membrane potential was held at −60 mV from layer II/III pyramidal neurons in the ACC with an Axon 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). The recording pipettes (3–5 MΩ) were filled with a solution containing (in mM) 145 K-gluconate, 5 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.2 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 Mg-ATP, and 0.1 Na3-GTP (adjusted to pH 7.2 with KOH, 290 mOsmol). NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs were recorded in Mg2+-free ACSF and neurons were held at −70 mV in the presence of CNQX (20 µM) and glycine (1 µM). The stimulation was delivered by a bipolar tungsten-stimulating electrode placed in layers V/VI of the ACC. Picrotoxin (100 µM) was always present to block GABAa receptor-mediated inhibitory synaptic currents in all experiments. Access resistance was 15–30 MΩ and monitored throughout the experiment. Data were discarded if access resistance changed 15% during an experiment. Data were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz using the digidata 1440A. Data were collected and analyzed with Clampex and Clampfit 10.2 software (Axon Instruments).

Data analysis

The data presented as means ± SEM. Statistical comparisons between two groups were performed using two-tail paired or unpaired Student’s t test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to identify significant differences. In all cases, *P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

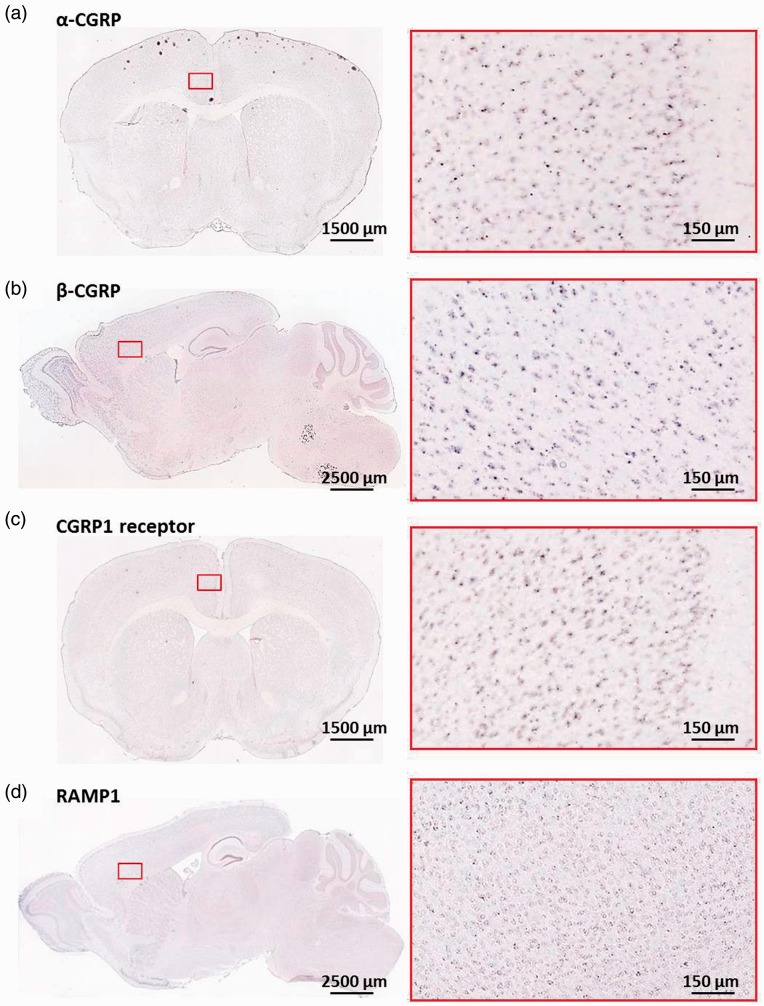

The expression of CGRP and its receptors in the ACC

To understand if CGRP and its receptors may be distributed in mouse ACC, we took the advantage of online brain mapping database (the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas). By searching, we found that in adult mouse brains the Calca gene is highly enriched in the ACC of wild-type mice, which encoded the α-CGRP in the brain (Figure 1(a), http://mouse.brain-map.org/experiment/show/79587715). Consistent with CGRP distribution in the ACC, the calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CGRP1 receptor) mRNA is also highly expressed in the ACC (Figure 1(c), http://mouse.brain-map.org/experiment/show/74988670). Especially in both layers II–III and deep layers of the ACC, they are highly expressed. In addition, another form of CGRP gene (Calcb) mRNA-encoded β-CGRP is also found in the ACC area (Figure 1(b), http://mouse.brain-map.org/experiment/show/69540278). Furthermore, we found that a receptor activity-modifying protein (RAMP1) mRNA was expressed in the ACC, which is another low-affinity CGRP receptor (Figure 1(d), http://mouse.brain-map.org/experiment/show/1913). These results are consistent with a recent report that CGRP, CGRP1 receptor, and RAMP1 immunoreactivities were detected in the almost entire cortical layers.21

Figure 1.

Expression of the CGRP and its receptors in the ACC (from the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas). (a) In situ hybridization on a coronal section of mouse brain, showing the expression of the α-CGRP gene in the ACC of wild-type mice (rectangled area, http://mouse.brain-map.org/experiment/show/79587715). (b) In situ hybridization on a sagittal section of mouse brain, showing the expression of the β-CGRP gene in the ACC of wild-type mice (rectangled area, http://mouse.brain-map.org/experiment/show/69540278). (c) In situ hybridization on a coronal section of mouse brain, showing expression of the calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CGRP1 receptor) gene in the ACC of wild-type mice (rectangled area, http://mouse.brain-map.org/experiment/show/74988670). (d) In situ hybridization on a sagittal section of mouse brain, showing expression of the RAMP1 gene in the ACC of wild-type mice (rectangled area, http://mouse.brain-map.org/experiment/show/1913). CGRP: calcitonin gene-related peptide; RAMP1: receptor activity-modifying protein 1.

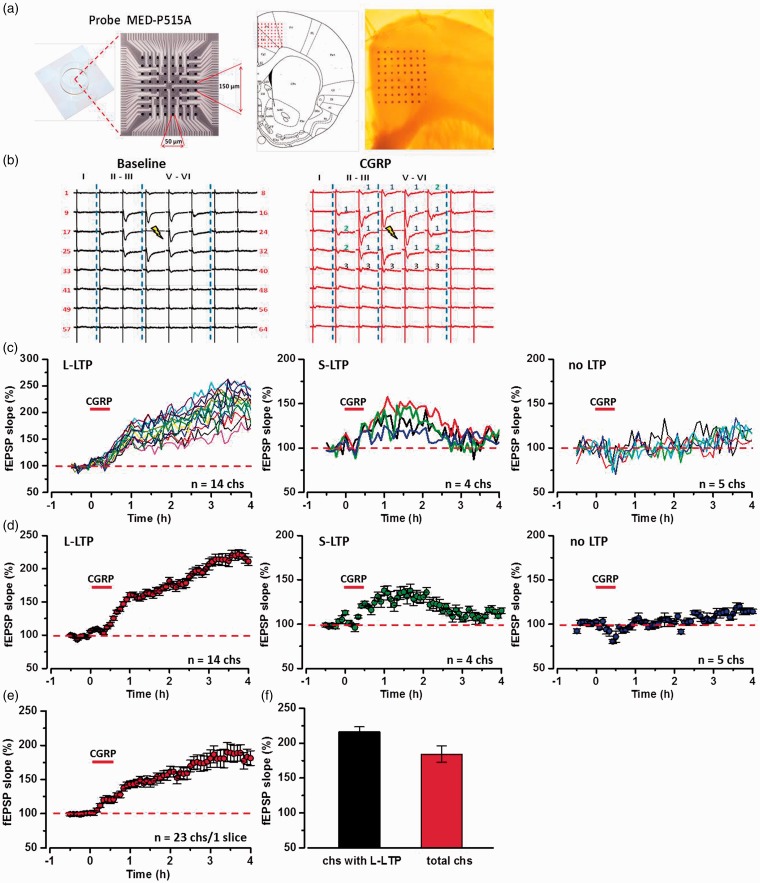

CGRP-induced long-term potentiation

Due to high-level expression of CGRP and its receptors, we wanted to examine if CGRP may affect excitatory synaptic transmission in the ACC. The 64-channel multielectrode array recording system (MED64) is a unique system to record field responses over a long period of time.17,22 The location of the 8 × 8 array MED64 probe electrodes within the ACC slice was shown in Figure 2(a). One channel in the deep layer V of the ACC was chosen as the stimulation site, and field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded from the other 63 channels around the stimulation site. After 30 min stable baseline recording, CGRP (100 nM) was applied for 30 min and then washed out. As shown in a typical sample slice with 23 active channels in the ACC (Figure 2(a) to (d)), 14 active channels (60.9%) showed potentiation of the fEPSP slope lasting for 4 h (L-LTP, 216.2 ± 7.0% of baseline) and four active channels (17.4%) showed a short-term potentiation lasting for <2 h (S-LTP), while five channels (21.7%) showed no potentiation throughout the entire recording period. The final averaged slope of all 23 channels was 184.3 ± 11.9% of baseline at 4 h after CGRP application (Figure 2(e) and (f)).

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of CGRP-induced LTP in the ACC obtaining with multichannel field potential recording. (a) Schematic diagram and the microphotograph showed the scale of the MED-64 probe (left), location of MED-64 probe on the ACC slice (middle), and one example microscopy photograph of the location of ACC slice and MED-64 probe (right). (b) Two mapped samples showed the spatial distribution of evoked field potentials in the ACC of baseline (left) and after the application of CGRP (right). The fEPSPs were induced by electrical stimulation on one channel (20, marked as light yellow) and were recorded from the other 63 channels for 30 min baseline (black), 30 min applied CGRP (100 nM), and 3.5 h after washout CGRP (Red). Channels with late phase LTP (L-LTP), short-term LTP (S-LTP), and no LTP were marked as “1” (blue) and “2” (green), and “3” (black), respectively. Vertical lines indicated the layers of ACC slices. (c) The sample temporal changes of the fEPSP slopes with three types of plasticity from one ACC slice of applying CGRP: 14 channels with L-LTP, 4 channels with S-LTP, and 5 channels without potentiation. (d) The averaged temporal changes of fEPSP slopes with three types of plasticity from one ACC slice of the application of CGRP: L-LTP, S-LTP, and no LTP. (e) The final averaged slope shown for all 23 active channels with 4 h after the application of CGRP in the ACC one slice. (f) Summarized data showed fEPSP slopes from channels with only L-LTP and from total active channels after the application of CGRP in the ACC one slice. The dashed line indicated the mean basal synaptic responses. CGRP: calcitonin gene-related peptide; LTP: long-term potentiation; fEPSP: field excitatory postsynaptic potential.

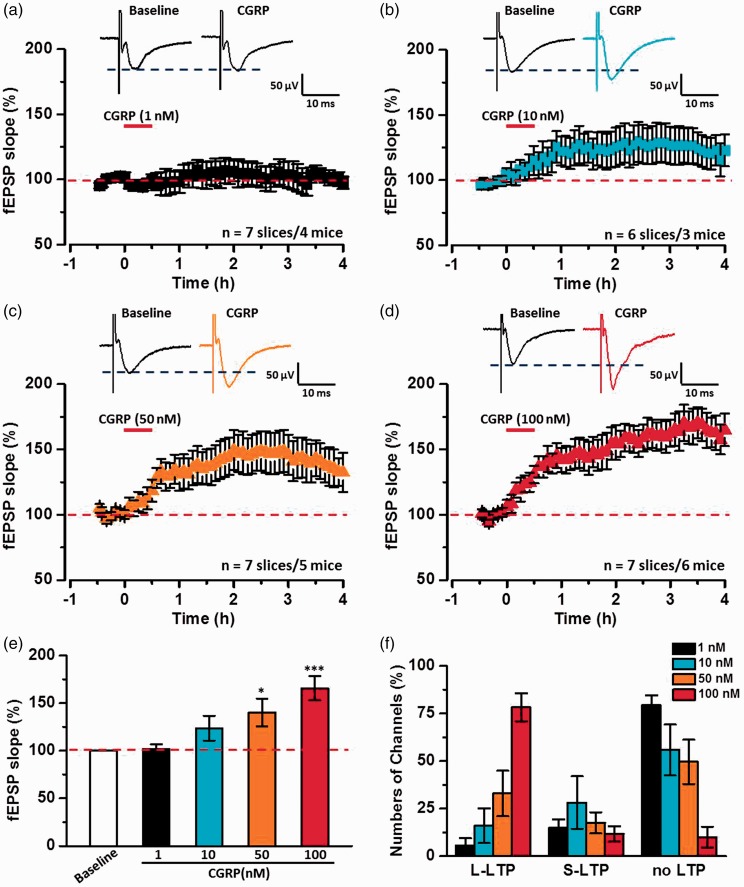

We then tested dose–response curves of CGRP’s effect on synaptic transmission in the ACC (Figure 3). As shown in Figure 3(a), a low dose of CGRP (1 nM) applied for the same duration did not change the fEPSP slope in the ACC (102.0 ± 4.7% of baseline, n = 7 slices/4 mice, P = 0.47, paired t test). The slope of fEPSP was no significantly changed after the application of 10 nM CGRP (121.2 ± 12.1% of baseline, n = 6 slices/3 mice, P = 0.12, paired t test).

Figure 3.

CGRP dose-dependently induced chemical LTP in the ACC. (a) Sample traces (top) and pooled fEPSP slopes (down) to illustrate the time course of 1 nM CGRP failed to induce LTP in the ACC (n = 7 slices/4 mice). (b) Sample traces (top) and pooled fEPSP slopes (down) to illustrate the time course of 10 nM CGRP potentiated the fEPSP slopes a little in the ACC (n = 6 slices/3 mice). (c) Sample traces (top) and pooled fEPSP slopes (down) to illustrate the time course of 50 nM CGRP induced a persistent LTP in the ACC (n = 7 slices/5 mice). (d) Sample traces (top) and pooled fEPSP slopes (down) to illustrate the time course of 100 nM CGRP induced a persistent LTP in the ACC (n = 7 slices/6 mice). (e) Statistical results showed that CGRP dose-dependently induced LTP after the application of CGRP 4 h in the ACC. (f) CGRP dose-dependently increased the percentage of L-LTP-occurring channels in the ACC. The dashed line indicated the mean basal synaptic responses. *P < 0.05, and ***P < 0.001, error bars indicated SEM.

However, after the application of 50 nM, CGRP induced a persistent chemical LTP in the ACC and lasted for 4 h (137.1 ± 12.9% of baseline, n = 7 slices/5 mice, P < 0.05, paired t test). Moreover, 100 nM CGRP induced a robust and persistent chemical LTP in the ACC (165.4 ± 11.9% of baseline, n = 7 slices/6 mice, P < 0.001, paired t test). This chemical LTP can last for more than 4 h and some slices could record for 6 h. Statistical results in Figure 3(e) showed that CGRP dose-dependently increased synaptic transmission and induced chemical LTP in the ACC (F(4, 31) = 8.83, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA). In addition, we analyzed the distribution ratios of L-LTP, S-LTP, and no LTP channels at different doses of CGRP application. We found that CGRP also dose-dependently increased the percentage of L-LTP-occurring channels in the ACC (1 nM: 5.7 ± 3.8%, 10 nM: 16.0 ± 9.1%, 50 nM: 33.0 ± 11.9%, 100 nM: 78.2 ± 7.4%, Figure 3(f)).

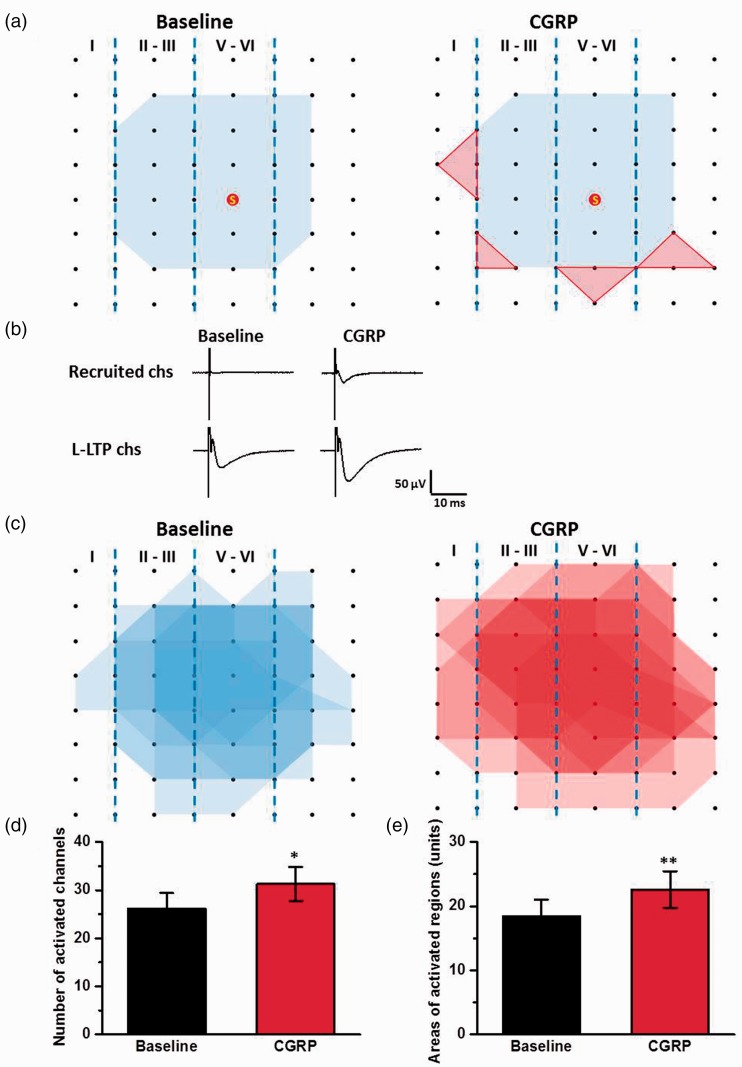

Spatial distribution and recruitment of synaptic responses within CGRP-induced LTP

Next, we mapped the spatial distribution of the active responses in the ACC before and after CGRP-induced potentiation using the previous method.17,19,22 As shown in Figure 4(a) and (c), the distribution of all observed activated-channels was displayed by a polygonal diagram on a grid representing the channels. The application of CGRP (100 nM) significantly enhanced the spatial distribution of active responses in the ACC. The region of four MED64 channels was defined as one unit and the area of one unit is 200 μm × 200 μm. The averaged area of activated regions was 18.4 ± 2.6 units for each slice and the area was increased to 22.6 ± 2.9 units after the application of CGRP (n = 7 slices/6 mice, P < 0.01, Figure 4(e)). The enlarged area was observed both in the deep and superficial layers in the ACC. Our previous studies reported that recruitment of synaptic responses can be observed in the theta burst stimulation (TBS) induction LTP.17,22 The recruited channels also were observed in chemical LTP induced by the application of CGRP (Figure 4(a) and (d)). In baseline phase, 26 ± 3 channels per slice (n = 7 slices/6 mice) were originally activated and showed fEPSPs. After CGRP-induced LTP, 5 ± 1 channels were recruited. These results suggest that CGRP enhances the network connection and recruitment of synaptic responses in the ACC.

Figure 4.

CGRP enhanced the network propagation of synaptic responses in the ACC. (a) Sample polygonal diagram showed the distribution of activated channels in the baseline state (blue) and CGRP recruited channels (red). The circled S indicates the stimulation site. (b) The sample traces showed the recruited response induced by CGRP. (c) Superimposed polygonal diagrams of the activated channels in the baseline state (blue) and the enlarged area after the application of CGRP (red) in seven slices from six wild-type mice. Black dots represented the 64 channels in the MED64. Vertical lines indicated the layers in the ACC slice. (d) and (e) The average number of active channels (d) and areas (e) that were activated before and after CGRP application. The area of one unit was defined 200 μm × 200 μm. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, error bars indicated SEM.

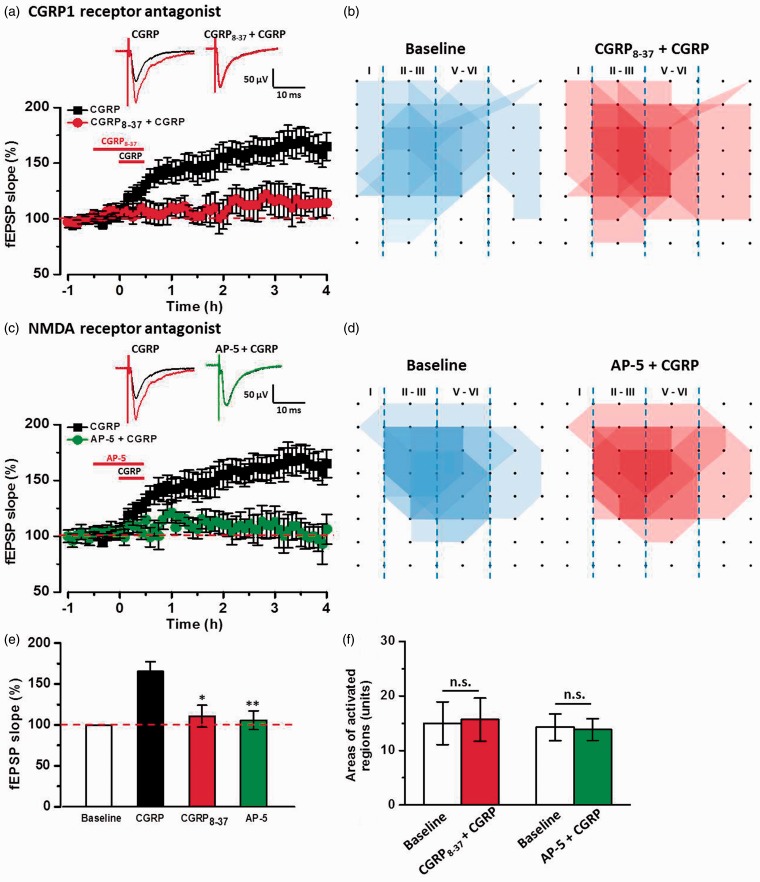

CGRP-induced LTP was blocked by CGRP1 receptor and NMDA receptor antagonists

We then tested the role of calcitonin receptor-like receptor CGRP1 in CGRP-induced chemical LTP. As shown in Figure 5(a), in the presence of CGRP1 receptor antagonist CGRP8–37 (1 μM), CGRP-induced chemical LTP was completely blocked by CGRP8–37 (110.7 ± 13.3% of baseline, n = 6 slices/4 mice, F(1, 11) = 8.67, P < 0.05 vs. CGRP group, one-way ANOVA, Figure 5(a) and (e)). CGRP8–37 also attenuated the enlargement spatial distribution of active responses induced by CGRP (15.0 ± 3.9 units for baseline; 15.6 ± 3.9 units for CGRP8–37 + CGRP; P = 0.58, paired t test; Figure 5(b) and (f)).

Figure 5.

Calcitonin receptor-like receptor and NMDA receptor were required for CGRP-induced LTP in the ACC. (a) Bath applied CGRP1 receptor antagonist CGRP8-37 (1 μM) completely blocked CGRP (100 nM)-induced LTP in the ACC slices (n = 6 slices/4 mice). (b) Superimposed polygonal diagrams of the activated channels in the baseline state (blue) and after the application of CGRP8-37 + CGRP (red) in six slices from four wild-type mice. (c) Bath applied NMDA receptor antagonist AP-5 (50 μM) blocked CGRP-induced LTP in the ACC slices (n = 6 slices/4 mice). (d) Superimposed polygonal diagrams of the activated channels in the baseline state (blue) and after the application of AP-5 + CGRP (red) in six slices from four wild-type mice. (e) Summarized results of the CGRP8-37 and AP-5 on CGRP-induced LTP in the ACC. (f) There were no significant enlarged areas after the application of CGRP in the presence of CGRP8-37 and AP-5 in the ACC. The mean slopes of fEPSPs were determined within last 30 min of 4 h LTP recording. All antagonists were applied 30 min before the application of CGRP and washed out together. The dashed line indicated the mean basal synaptic responses. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 mean antagonist groups versus CGRP group. n.s. means no significant difference, error bars indicated SEM.

NMDA receptors play crucial roles in the induction of LTP.10,23,24 Next, NMDA receptor antagonist AP-5 (50 μM) was bath-applied 30 min before the application of CGRP and then washed out together. We found that the fEPSP slope was not increased by the application of CGRP in the presence of AP-5 (105.8 ± 11.4% of baseline, n = 6 slices/4 mice, F(1, 11) = 11.83, P < 0.05 vs. CGRP group, one-way ANOVA, Figure 5(c) and (e)). Moreover, the spatial distribution of active responses was also not changed by the application of CGRP in the presence of AP-5 (14.3 ± 2.5 units for baseline; 13.8 ± 2.0 units for AP-5 + CGRP; P = 0.61, paired t test; Figure 5(d) and (f)). Taken together, these results indicate that the roles of CGRP in the ACC are CGRP1 receptor and NMDA receptor dependent.

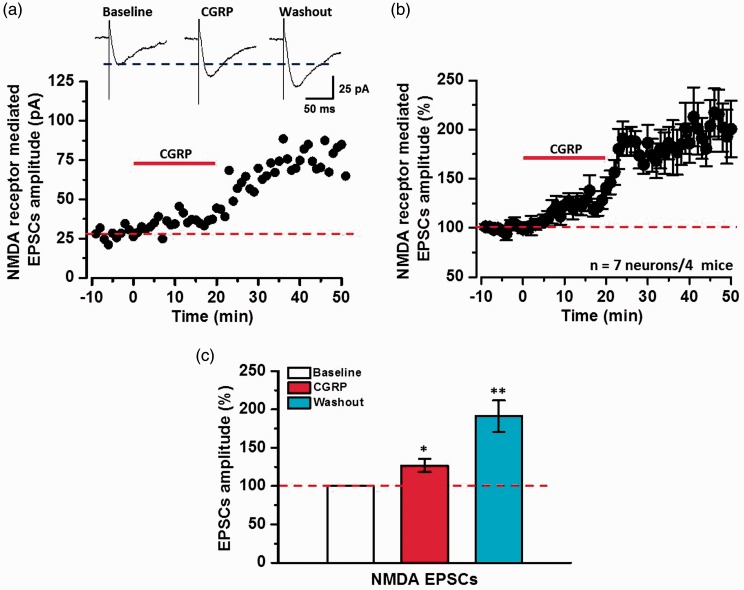

CGRP increased NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs

Since NMDA receptor is important for CGRP-induced chemical LTP in the ACC, we then tested if CGRP affects NMDA receptor-mediated currents. We examined the effects of CGRP on the NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs using whole-cell patch-clamp recording. As shown in Figure 6(a), we bath applied CGRP (100 nM, 20 min) after stable baseline recording. CGRP significantly increased the amplitudes of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs in both the application phase and washout phase. After 50 min, NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs were increased to mean 193.6 ± 20.5% of baseline (n = 7 neurons/4 mice, P < 0.01, paired t test, Figure 6(b) and (c)). This result suggests that CGRP increases NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in the ACC.

Figure 6.

CGRP increased NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs. (a) Sample traces (top) and sample time course points (bottom) showing the effect of CGRP (100 nM) on NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs in the ACC pyramidal neuron. (b) Summarized time course points showed that NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs were increased by the application of CGRP in the ACC neurons (n = 7 neurons/4 mice). (c) Statistical results showing the amplitude percentage of NMDA EPSCs during baseline, application of CGRP, and washout in the ACC. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, error bars indicated SEM.

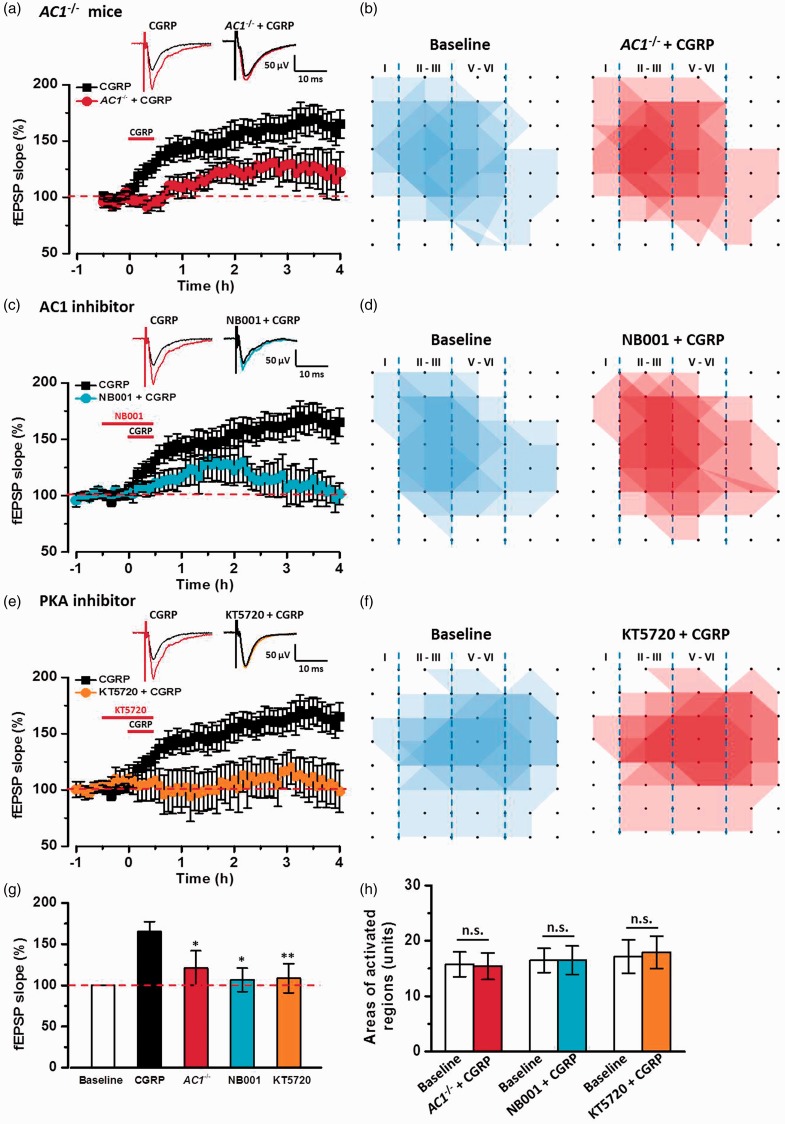

AC1 and PKA were required

In the ACC, postsynaptic LTP requires the activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase 1(AC1) and PKA.10 We then tested whether AC1 and PKA signal pathways were required for CGRP-induced chemical LTP. In genetic knockout of AC1−/− mice, CGRP-induced LTP was impaired in the ACC (120.0 ± 20.8% of baseline, n = 6 slices/3 mice, F(1, 11) = 10.04, P < 0.05 vs. CGRP, Figure 7(a) and (g)). The spatial distribution of active responses was also not affected by the application of CGRP in AC1−/− mice (Figure 7(b) and (h)). To further test the role of AC1, we used a selective AC1 inhibitor NB001. In the presence of AC1 inhibitor NB001 (20 μM), CGRP-induced LTP was attenuated by NB001 in the ACC (106.7 ± 14.4% of baseline, n = 6 slices/4 mice, F(1, 11) = 9.37, P < 0.05 vs. CGRP, Figure 7(c) and (g)) and related network propagation was also inhibited (Figure 7(d) and (h)). Finally, we applied KT5720 (1 μM), a PKA inhibitor, in the bath solution. We found that CGRP-induced LTP in the ACC was completely decreased by KT5720 (108.6 ± 17.7% of baseline, n = 6 slices/4 mice, F(1, 11) = 12.38, P < 0.01 vs. CGRP, Figure 7(e) and (g)), and no new active responses increased in the presence of KT5720 (Figure 7(f) and (h)). Taken together, these data suggest that CGRP-induced potentiation requires AC1-PKA signal pathways in the ACC.

Figure 7.

Adenylyl cyclase and PKA signal pathways were involved in CGRP-induced LTP in the ACC. (a) In AC1−/− mice, CGRP-induced LTP was attenuated in the ACC slices (n = 6 slices/3 mice). (b) Superimposed polygonal diagrams of the activated channels in the baseline state (blue) and after the application of CGRP (red) in AC1−/− mice. (c) In the presence of AC1 inhibitor NB001, CGRP-induced LTP was inhibited by NB001 (20 μM) in the ACC slices (n = 6 slices/4 mice). (d) Superimposed polygonal diagrams of the activated channels in the baseline state (blue) and after the application of NB001+ CGRP (red) in six slices from four wild-type mice. (e) PKA inhibitor, KT5720 (1 μM) completely inhibited CGRP-induced LTP (n = 6 slices/4 mice). (f) Superimposed polygonal diagrams of the activated channels in the baseline state (blue) and after the application of KT5720 + CGRP (red) in six slices from four wild-type mice. (g) Summary results showing the effects of in AC1−/− mice, AC1 inhibitor and PKA inhibitor on CGRP-induced LTP in the ACC. (h) There were no significant enlarged areas after the application of CGRP in AC1−/− mice, in the presence of NB001 and KT5720 in the ACC. The dashed line indicated the mean basal synaptic responses. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 mean inhibitor groups versus CGRP group, error bars indicated SEM.

Discussion

Due to the important roles of ACC in pain perception and chronic pain, it is likely that cortical excitation in the ACC may contribute to headache. There are cumulative evidences from both basic and clinical investigations that the neuropeptide CGRP plays important roles in migraine. In the present study, we found that CGRP dose-dependently facilitated excitatory synaptic transmission and enhanced the network propagation of cortical circuitry in the ACC. NMDA receptors are dependent for the role of CGRP in the ACC. In addition, AC1 and PKA are involved in the function of CGRP in the ACC. Our results indicate that CGRP may be involved in the ACC-related physiological and pathological functions, such as headache and migraine (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The proposed model explains synaptic mechanisms of CGRP-induced chemical LTP in the ACC. Left: a simplified diagram shows that CGRP is released from trigeminal afferent nerve fibers, whose primary afferents innervate pial and dural meningeal vessels and whose efferent projections synapse with second-order neurons in the TNC of the brainstem. Neurons in the TNC project to the thalamus, where ascending input is integrated and relayed to the ACC. Right: a synaptic model for CGRP-induced LTP. CGRP in the ACC enhanced the synaptic transmission through a postsynaptic mechanism by the activation of NMDA receptor and AC1-PKA signal pathway. TNC: trigeminal nucleus caudalis.

CGRP-induced potentiation in the ACC

Previous investigation of the effect of CGRP on central synaptic transmission are mainly focused on amygdala,25–27 spinal cord,28,29 and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis.30,31 In the amygdala, CGRP was reported to contribute to synaptic transmission and plasticity. CGRP facilitates synaptic transmission and contributes critically to the pain-related plasticity.32 In the present study, we demonstrated that exogenous application of CGRP dose-dependently increased synaptic transmission and induced chemical LTP in the ACC. This CGRP-induced chemical LTP did not require high-frequency synaptic stimulation during the CGRP application.

CGRP can trigger the recruitment of cortical circuits and increase the spatial distribution of active responses in the ACC. This property of CGRP-induced chemical LTP is consistent with TBS-induced LTP in the ACC as our previous studies.17,22 In the ACC, the recruitment is unlikely caused just by enhancement of synaptic transmission. We propose that CGRP-induced recruitment may be caused by the activation of “silent” synapses in the ACC.33 Our results indicate that there are two possible mechanisms that may contribute to CGRP-induced potentiation at the circuit level in the ACC. One is CGRP-induced typical LTP, which is potentiation of synaptic responses by postsynaptic receptor modifications.11 The other possibility is to recruit postsynaptic glutamate receptors into “silent” synapses. Future studies are clearly needed to investigate the exact molecular mechanism for CGRP produced effects in the ACC.

NMDA receptors are important

In the ACC, there are at least two forms of LTP: presynaptic LTP (pre-LTP) and postsynaptic LTP (post-LTP). NMDA receptor-dependent Ca2+ signals are critical for the induction of post-LTP.10,11,23,34 In our present study, CGRP-induced chemical LTP is also NMDA receptor-dependent LTP. Moreover, we found that CGRP application also enhanced NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs. In the amygdala synapses, CGRP also induced a NMDA receptor-dependent LTP and increased NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs in a PKA-dependent manner.25–27 However, we failed to observe any CGRP enhanced AMPA receptor-mediated EPSCs in whole-cell patch recording configure (unpublished data). One possible explanation may be that CGRP induces synaptic potentiation through NMDA receptor-dependent LTP of AMPA receptor function.

AC1 and PKA signal pathway

Previous studies have reported that CGRP produced synaptic enhancement through activating ACs and PKA in the amygdala.26,27 In the ACC, we found that CGRP-induced chemical LTP was blocked in genetic deletion of neuronal or by a selective AC1 inhibitor NB001. These results provide strong evidence that CGRP enhanced ACC synaptic transmission through a postsynaptic mechanism by the activation of NMDA receptor and AC1 signal pathway. Furthermore, a PKA inhibitor also blocked CGRP-induced potentiation, supporting roles of cAMP-AC1 signaling pathway.

Physiological and pathological significance

Cumulative evidence from human and animal studies demonstrates that the ACC is important for pain-related perception and chronic pain.11,35–37 Inhibiting the induction or expression of LTP in the ACC produces significant analgesic effects in different animal models of chronic pain such as neuropathic and inflammatory pain.9,38,39 Clinical human brain imaging studies suggest that ACC activities are increased during or after chronic migraine.13,14 Our present study show that CGRP-induced LTP in the ACC, indicating that CGRP may contribute to pathological pain by enhancing synaptic transmission and NMDA receptor functions in the ACC at least. Furthermore, we demonstrate that NB001, a novel and selective AC1 inhibitor, blocks CGRP-induced LTP in the ACC. Our results provide strong evidence that NB001 may be useful for future treatment of chronic headache and migraine.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Qi-Yu Chen and Melissa Lepp for English editing.

Author Contributions

XHL, TM, RHL, and MX performed MED64 experiments. XHL and TM contributed whole-cell patch recording. XHL drafted the manuscript. XHL and MZ designed the project and finished the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR) Michael Smith Chair in Neurosciences and Mental Health, Canada Research Chair, CIHR operating grant (MOP-124807), and project grant (PJT-148648), Azrieli Neurodevelopmental Research Program and Brain Canada, awarded to MZ.

References

- 1.May A, Schulte LH. Chronic migraine: risk factors, mechanisms and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 2016; 12: 455–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su M, Yu SY. Chronic migraine: a process of dysmodulation and sensitization. Mol Pain 2018; 14: 1--10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho TW, Edvinsson L, Goadsby PJ. CGRP and its receptors provide new insights into migraine pathophysiology. Nat Rev Neurol 2010; 6: 573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russo AF. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP): a new target for migraine. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2015; 55: 533–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lassen LH, Haderslev P, Jacobsen VB, Iversen HK, Sperling B, Olesen J. CGRP may play a causative role in migraine. Cephalalgia 2002; 22: 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason BN, Kaiser EA, Kuburas A, Loomis MM, Latham JA, Garcia-Martinez LF, Russo AF. Induction of migraine-like photophobic behavior in mice by both peripheral and central CGRP mechanisms. J Neurosci 2017; 37: 204–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russo AF. CGRP as a neuropeptide in migraine: lessons from mice. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015; 80: 403–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhuo M. Cortical excitation and chronic pain. Trends Neurosci 2008; 31: 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li XY, Ko HG, Chen T, Descalzi G, Koga K, Wang H, Kim SS, Shang Y, Kwak C, Park SW, Shim J, Lee K, Collingridge GL, Kaang BK, Zhuo M. Alleviating neuropathic pain hypersensitivity by inhibiting PKMzeta in the anterior cingulate cortex. Science 2010; 330: 1400–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bliss TV, Collingridge GL, Kaang BK, Zhuo M. Synaptic plasticity in the anterior cingulate cortex in acute and chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2016; 17: 485–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhuo M. Long-term potentiation in the anterior cingulate cortex and chronic pain. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2013; 369: 20130146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russo A, Tessitore A, Esposito F, D, Nardo F, Silvestro M, Trojsi F, D, Micco R, Marcuccio L, Schoenen J, Tedeschi G. Functional changes of the perigenual part of the anterior cingulate cortex after external trigeminal neurostimulation in migraine patients. Front Neurol 2017; 8: 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matharu MS, Bartsch T, Ward N, Frackowiak RSJ, Weiner R, Goadsby PJ. Central neuromodulation in chronic migraine patients with suboccipital stimulators: a PET study. Brain 2004; 127: 220–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Tommaso M, Losito L, Difruscolo O, Libro G, Guido M, Livrea P. Changes in cortical processing of pain in chronic migraine. Headache 2005; 45: 1208–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prescot A, Becerra L, Pendse G, Tully S, Jensen E, Hargreaves R, Renshaw P, Burstein R, Borsook D. Excitatory neurotransmitters in brain regions in interictal migraine patients. Mol Pain 2009; 5: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei F, Qiu CS, Kim SJ, Muglia L, Maas JW, Pineda VV, Xu HM, Chen ZF, Storm DR, Muglia LJ, Zhuo M. Genetic elimination of behavioral sensitization in mice lacking calmodulin-stimulated adenylyl cyclases. Neuron 2002; 36: 713–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song Q, Zheng HW, Li XH, Huganir RL, Kuner T, Zhuo M, Chen T. Selective phosphorylation of Ampa receptor contributes to the network of long-term potentiation in the anterior cingulate cortex. J Neurosci 2017; 37: 8534–8548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li XH, Song Q, Chen QY, Lu JS, Chen T, Zhuo M. Characterization of excitatory synaptic transmission in the anterior cingulate cortex of adult tree shrew. Mol Brain 2017; 10: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen T, O’Den G, Song Q, Koga K, Zhang MM, Zhuo M. Adenylyl cyclase subtype 1 is essential for late-phase long term potentiation and spatial propagation of synaptic responses in the anterior cingulate cortex of adult mice. Mol Pain 2014; 10: 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sellmeijer J, Mathis V, Hugel S, Li XH, Song Q, Chen QY, Barthas F, Lutz PE, Karatas M, Luthi A, Veinante P, Aertsen A, Barrot M, Zhuo M, Yalcin I. Hyperactivity of anterior cingulate cortex areas 24a/24b drives chronic pain-induced anxiodepressive-like consequences. J Neurosci 2018; 38: 3102–3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warfvinge K, Edvinsson L. Distribution of CGRP and CGRP receptor components in the rat brain. Cephalalgia 2017; 333102417728873. doi:10.1177/0333102417728873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen T, Lu JS, Song Q, Liu MG, Koga K, Descalzi G, Li YQ, Zhuo M. Pharmacological rescue of cortical synaptic and network potentiation in a mouse model for fragile X syndrome. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014; 39: 1955–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li XH, Miao HH, Zhuo M. NMDA receptor dependent long-term potentiation in chronic pain. Neurochem Res 2018. doi:10.1007/s11064-018-2614-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao MG, Toyoda H, Lee YS, Wu LJ, Ko SW, Zhang XH, Jia Y, Shum F, Xu H, Li BM, Kaang BK, Zhuo M. Roles of NMDA NR2B subtype receptor in prefrontal long-term potentiation and contextual fear memory. Neuron 2005; 47: 859–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okutsu Y, Takahashi Y, Nagase M, Shinohara K, Ikeda R, Kato F. Potentiation of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission at the parabrachial-central amygdala synapses by CGRP in mice. Mol Pain 2017; 13: 1--11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu X, Zhang JT, Liu J, Yang S, Chen T, Chen JG, Wang F. Calcitonin gene-related peptide erases the fear memory and facilitates long-term potentiation in the central nucleus of the amygdala in rats. J Neurochem 2015; 135: 787–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han JS, Li W, Neugebauer V. Critical role of calcitonin gene-related peptide 1 receptors in the amygdala in synaptic plasticity and pain behavior. J Neurosci 2005; 25: 10717–10728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCoy ES, Taylor-Blake B, Street SE, Pribisko AL, Zheng J, Zylka MJ. Peptidergic CGRPalpha primary sensory neurons encode heat and itch and tonically suppress sensitivity to cold. Neuron 2013; 78: 138–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bird GC, Han JS, Fu Y, Adwanikar H, Willis WD, Neugebauer V. Pain-related synaptic plasticity in spinal dorsal horn neurons: role of CGRP. Mol Pain 2006; 2: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gungor NZ, Pare D. CGRP inhibits neurons of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis: implications for the regulation of fear and anxiety. J Neurosci 2014; 34: 60–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campos CA, Bowen AJ, Roman CW, Palmiter RD. Encoding of danger by parabrachial CGRP neurons. Nature 2018; 555: 617–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han JS, Adwanikar H, Li Z, Ji G, Neugebauer V. Facilitation of synaptic transmission and pain responses by CGRP in the amygdala of normal rats. Mol Pain 2010; 6: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerchner GA, Nicoll RA. Silent synapses and the emergence of a postsynaptic mechanism for LTP. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008; 9: 813–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li XH, Song Q, Chen T, Zhuo M. Characterization of postsynaptic calcium signals in the pyramidal neurons of anterior cingulate cortex. Mol Pain 2017; 13: 1--13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhuo M. Ionotropic glutamate receptors contribute to pain transmission and chronic pain. Neuropharmacology 2017; 112: 228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bushnell M C, Čeko M, Low L A. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013; 14: 502–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vogt BA. Pain and emotion interactions in subregions of the cingulate gyrus. Nat Rev Neurosci 2005; 6: 533–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H, Xu H, Wu LJ, Kim SS, Chen T, Koga K, Descalzi G, Gong B, Vadakkan KI, Zhang X, Kaang BK, Zhuo M. Identification of an adenylyl cyclase inhibitor for treating neuropathic and inflammatory pain. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3: 65ra3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu LJ, Toyoda H, Zhao MG, Lee YS, Tang J, Ko SW, Jia YH, Shum FW, Zerbinatti CV, Bu G, Wei F, Xu TL, Muglia LJ, Chen ZF, Auberson YP, Kaang BK, Zhuo M. Upregulation of forebrain NMDA NR2B receptors contributes to behavioral sensitization after inflammation. J Neurosci 2005; 25: 11107–11116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]