Abstract

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) are aggressive soft-tissue sarcomas. The prognosis of MPNSTs has been reported to differ among previous studies. However, there have been a number of reported prognostic biomarkers associated with MPNSTs. In the present study, a proteomics study was performed to discover the differential protein expression in patients with MPSNTs with different prognoses. The clinical data of 30 primary extremities of patients with MPNSTs, who underwent surgery at the Department of Hand Surgery, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University between January 2002 and December 2011, were acquired. A total of 16 patients succumbed to their diseases within 5 years, whereas 14 patients were disease-free for >5 years. Samples from the 9 patients who succumbed within 2 years were assigned to Group D, while samples from the 8 patients who were continuously disease-free for >5 years following diagnosis were assigned to Group L for the proteomics study. Label-free quantitative proteomics and mass spectrometry were performed to filtrate differential protein in patients with MPSNTs with different prognoses. Decorin was filtrated as a differential protein of note. The expression level of decorin was significantly lower in Group D compared with that in Group L (D/L=0.0948; P=0.0004). The result was verified by immunohistochemical staining in the 30 primary extremities of patients with MPNSTs. The 5-year survival rate of patients with positive expression of decorin was 78.57%, while the 5-year survival rate of patients negative for decorin expression was 18.75% (P=0.0014). Overall, a high level of decorin indicted a better prognosis in patients with MPNSTs. With further investigation, decorin may be a reliable prognostic biomarker for MPNSTs.

Keywords: decorin, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, label-free quantitative proteomics, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded, prognostic biomarker

Introduction

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) are aggressive tumors that comprise 5–10% of all soft-tissue sarcomas (1). The extremities are the most common sites in which these tumors occur. The most common treatment for an MPNST is extended resection plus radiotherapy or chemotherapy (2). However, the prognosis for MPNSTs is generally poor, with a high rate of local recurrence and metastasis. The prognosis has been reported to differ among previous studies, with the 5-year survival rate ranging between 15 and 50% (1,3). Therefore, further investigation is required to identify potential predictive biomarkers for the prognosis of patients with MPSNTs.

The importance of tumor proteomics has recently become more recognized. However, to the best of our knowledge, the proteomic studies of MPNSTs are rarely reported in the literature, as they are rare in nature. Use of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues is a powerful resource for biomarker discovery, as it facilitates the long-distance exchange of samples, it is stable and biohazard-free, and it presents a limited number of ethical issues compared with the use of fresh tissues (4). Analyzing the FFPE tissue samples with a label-free quantitative proteomics approach has been reported to be an easy and effective method for investigation (5–7). To the best of our knowledge, research on MPNST samples using the aforementioned approach has not previously been reported in the literature.

In the present study, the FFPE tissue samples of patients with MPNSTs were obtained. A proteomics study on MPNST FFPE tissue samples with label-free quantitative proteomics and mass spectrometry was performed to discover the differential protein expressed in patients with MPSNTs with different prognoses. Immunohistochemical staining was performed to verify the results of the present study.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

The clinical data of 30 primary extremities of patients with MPNSTs, who underwent surgery in the Department of Hand Surgery, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, between January 2002 and December 2011, were acquired. The mean age of the patients was 49.06 years old, ranged from 11 to 71 years old, 8 patients were male while 9 were female. A total of 16 patients succumbed to their diseases within 5 years, whereas 14 patients had a survival rate of >5 years. The FFPE tissue samples of all these patients were obtained. The histological diagnosis of the tissues was reviewed by two senior pathologists. A total of 17 typical samples were divided into the following two groups: Group D, comprising of samples from 9 patients who succumbed within 2 years; and Group L, comprising of samples from 8 patients who were continuously disease-free for >5 years following diagnosis. The detailed clinical data are presented in Table I. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their family members. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The present study was approved by the ethics committee of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University.

Table I.

Clinical data of the patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in Group L and Group D.

| Patient no. | Age, years | Sex | Largest dimension of the tumor, cm | Tumor-involved nerve | Surgery | Adjuvant therapy | Local recurrence | Metastasis | Survival time following diagnosis, months | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70 | Male | 3 | Ulnar nerve | Extended | No | No | No | >60 | Disease-free |

| 2 | 42 | Female | 4 | Deep peroneal nerve | Extended | No | No | No | >60 | Disease-free |

| 3 | 41 | Female | 9 | Median nerve | Extended | No | No | No | >60 | Disease-free |

| 4 | 11 | Male | 8 | C5 nerve root | Extended | Radiotherapy | No | No | >60 | Disease-free |

| 5 | 55 | Female | 4 | Radial nerve | Extended | Radiotherapy | No | No | >60 | Disease-free |

| 6 | 60 | Female | 6 | Subcutaneous nerve | Extended | No | No | No | >60 | Disease-free |

| 7 | 59 | Male | 6 | Median nerve | Extended | No | No | No | >60 | Disease-free |

| 8 | 53 | Male | 5.5 | Median nerve | Extended | Radiotherapy | No | No | >60 | Disease-free |

| 9 | 50 | Female | 12 | Brachial plexus | Subtotal | Chemotherapy | No | Yes | 18 | Succumbed to disease |

| 10 | 71 | Female | 10 | L2 nerve root | Subtotal | No | No | Yes | 10 | Succumbed to disease |

| 11 | 67 | Female | 4 | Subcutaneous nerve | Extended | Radiotherapy | No | Yes | 3 | Succumbed to disease |

| 12 | 33 | Male | 8 | Lateral cord | Extended | Radiotherapy | Yes | Yes | 9 | Succumbed to disease |

| 13 | 60 | Male | 4.5 | Sciatic nerve | Extended | No | No | Yes | 4 | Succumbed to disease |

| 14 | 71 | Female | 1 | Posterior tibial nerve | Extended | No | No | Yes | 12 | Succumbed to disease |

| 15 | 23 | Male | 2 | Suprascapular nerve | Extended | Radiotherapy | Yes | Yes | 19 | Succumbed to disease |

| 16 | 42 | Female | 9 | Radial nerve | Subtotal | No | No | No | 2 | Succumbed to disease |

| 17 | 26 | Male | 7 | Lower trunk | Extended | Radiotherapy | Yes | No | 5 | Succumbed to disease |

Group L, succumbed within 2 years of diagnosis; Group D, continuously disease-free for >5 years following diagnosis.

Label-free quantitative proteomics

Microtome sections (10-µm thick and 80-mm 2 wide) were cut from FFPE tissue blocks (10% formalin was used for 10 hr at room temperature) and deparaffinized by incubation in a graded series of xylene (100, 67 and 33%) for 10 min at room temperature prior to rehydration in a graded series of ethanol (100, 67 and 33%) for 10 min at room temperature. The tissue sections were scraped from the slides and then resuspended in SDT buffers (4% SDS, 100 mM DTT, 100 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.6). All samples were incubated in the buffers at 100°C for 20 min, and at 80°C for 2 h with oscillation. The extracts were centrifuged for 30 min at 14,000 × g at 4°C. Protein quantification was performed using the BCA (bicinchoninic acid) method. A total of 20 µg of each sample was obtained for SDS-PAGE (12%). Bands were clearly separated.

A total of 200 µg of each sample was solubilized in 100 mM dithiothreitol (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) using a boiling water bath for 5 min, and subsequently cooled down until it reached room temperature. A total of 200 µl uric acid (UA) buffer (urea, 8 M; Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM) was added, mixed and centrifuged for 15 min at 14,000 × g at 4°C. A total of 200 µl UA buffer was added, centrifuged for 15 min at 14,000 × g and filtrated at 4°C. Next, 100 µl indole-3-acetic acid (IAA, Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in 50 mM UA was added, oscillated, kept in darkness for 30 min and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g at 4°C. A total of 100 µl UA buffer was added and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g at 4°C, repeated in duplicate. Subsequently, 100 µl dissolution buffer was added and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g at 4°C and repeated twice. Lastly, a total of 40 µl trypsin buffer (5 µg trypsin in 40 µl dissolution buffer) was added, oscillated, kept at 37°C for 16 h. A new collecting tube was changed and the sample was centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g at 4°C. The resulting peptides were collected as a filtrate. The peptide content was estimated by UV light spectral density at 280 nm. The result of OD280 peptide quantification of the two groups were >0.1, which means the effect of proteolysis was satisfied.

High-performance liquid chromatography and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS)

A total of 2 µg of each enzymatic hydrolysis sample was obtained and LCMS analysis was performed. The system was used at room temperature. The desolvation gas was set to 500 l/h at a temperature of 350°C. The cone gas was set to 25 l/h, and the source temperature was set to 120°C. The liquid phase solution A was 0.1% formic acid acetonitrile water solution (2% acetonitrile), while the solution B was 0.1% formic acid acetonitrile aqueous solution (84% acetonitrile). Chromatographic Thermo Scientific EASY column (SC200; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with RP-C18 column (150 µm ×100 mm) was balanced with 100% solution A. The samples were loaded onto Thermo Scientific EASY column SC001 traps equipped with RP-C18 column (150 µm × 20 mm) and separated by a chromatographic column with a 400 nl/min flow rate. The peptides generated from the digestion were eluted with the following binary gradients: Solution A and 0–45% solution B for 100 min, followed by 45–100% solution B for additional 12 min. The enzymatic hydrolysis sample was separated by capillary high performance liquid chromatography. MS was performed by Q-Exactive (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 120 min. The detection method was positive ions. Parent ion scan ranged between 300–1800 m/z.

Original files of LCMS/MS were imported into Maxquant software (version 1.3.0.5; http://www.biochem.mpg.de/5111795/maxquant). Label-free quantification was performed by using IBAQ, according to the Uniprot Human database (www.uniprot.org). The major parameters were as follows: Main search ppm, 6; missed cleavage, 2; MS/MS tolerance ppm, 20; de-isotopic, TRUE; enzyme, trypsin; database, uniprot_human_138560_20141014.fasta; fixed modification, carbamidomethyl (C); variable modification, oxidation (M), acetyl (protein N-term); decoy database pattern, reverse; iBAQ, TRUE; match between runs, 2 min; peptide false discovery rate (FDR), 0.01; and protein FDR, 0.01.

Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemical staining was performed in 30 MPNST FFPE tissue samples to verify the chosen protein. Antibodies were acquired as follows: Anti-decorin (dilution, 1:50; cat. no. ab54728; Abcam). Two certified pathologists, who were blinded to the clinical data of the patients, performed the immunohistochemical staining. Samples were blocked with 10% goat serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1hr at room temperature. The 5 µm-thick tissue sections were autoclaved in EDTA Antigen repair solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and incubated with anti-decorin antibody at room temperature for 45 min. Immunostaining was performed using the biotin-free horseradish peroxidase enzyme-labeled polymer (SABC ready-to used antibody (sa1020, boster) Duration: 1:1,000 room temperature 1h of the Envision Plus detection system. (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) with a light microscope at ×100 magnification. The results were based on the percentage of stained cells, <5 % was classified as negative, while others were classified as positive.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed by Perseus (version 1.3.0.4; www.coxdocs.org). In the data analysis process, an unpaired Student's t-test was used to determine significant differences. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. All data are shown as mean ± SD (n=3).

Bioinformatics analysis

Bioinformatics analysis including Gene Ontology (GO) analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome (KEGG) was performed. GO analysis (http://www.geneontology.org/) was performed by Blast2GO (version 2.8.0) (8). KEGG pathways analysis was performed by KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html) (9). The significant differential proteins were filtrated according to the following criteria: the ratio between Group L and Group D was >2.0 or <0.5, with a P-value of <0.05.

Results

Overview of quantitative proteomics

A total of 1,646 proteins were identified following protein extraction according to the previously described protocol. A total of 152 differential proteins were subsequently filtrated according to the following criteria: The ratio between Group L and Group D was >2.0 or <0.5, with a P-value of <0.05. There were 73 upregulated and 79 downregulated proteins in Group D compared with Group L.

Bioinformatics analysis

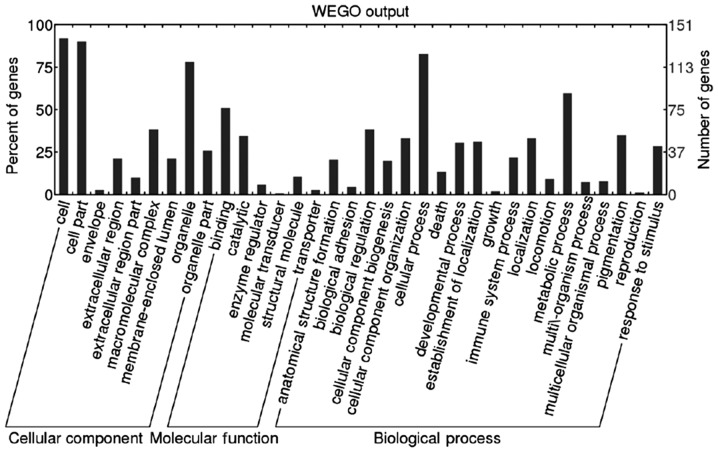

GO analysis (http://www.geneontology.org/) was performed by Blast2GO (version 2.8.0). A total of 151 (99.34%) differential proteins were annotated. Biological process, molecular function and cellular component were classified. The result of GO slim level 2 are presented as Web Gene Ontology Annotation Plot (WEGO) in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Result of Gene Ontology slim level 2, including the classification of biological process, molecular function and cellular component. WEGO, Web Gene Ontology Annotation Plot.

A total of 167 KEGG pathways associated with 79 differential proteins were extracted by KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html). Decorin, as an extinct differential protein associated with the malignant tumor, was filtrated. The level of decorin was significantly lower in Group D compared with that in Group L (D/L=0.0948; P=0.0004). Decorin was associated with the activation of the TGF-β signaling pathway. Decorin participated in ‘cellular process’, ‘single-organism process’, ‘metabolic process’, ‘cellular component organization or biogenesis’, and ‘developmental process’.

Immunohistochemical staining

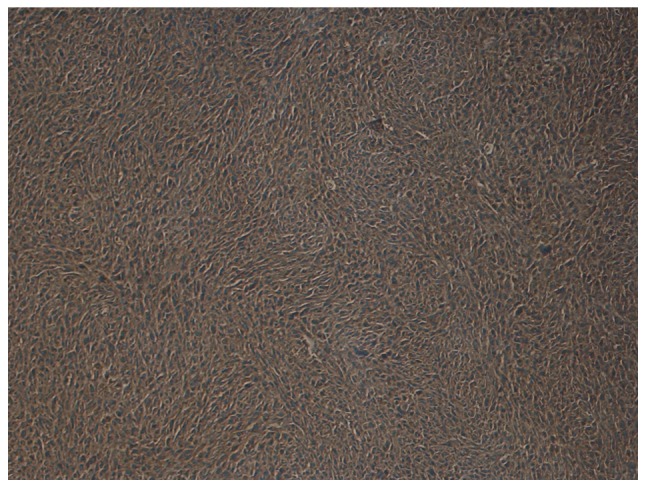

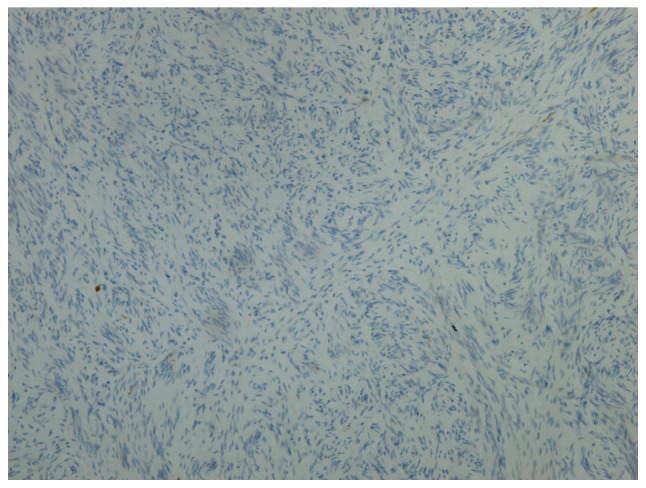

Immunohistochemical staining was performed in 30 MPNST tissue samples to verify the reliability of decorin. In Group L, decorin was positive in 11 patients (78.57%) and negative in 3 patients (21.43%). In Group D, 3 patients (18.75%) were positive for decorin and 13 patients (81.25%) were negative for decorin. Representative images of positivity and negativity for decorin in MPNST tissue samples are shown in Figs. 2 and 3. The 5-year survival rate of patients positive for decorin expression was 78.57%, while the 5-year survival rate of patients negative for decorin expression was 18.75%. The patients' 5-year survival rate with decorin positive expression was significantly higher than that with decorin negative expression (P=0.0014). According to these results, decorin may serve as a reliable prognostic biomarker for patients with MPNSTs. However, further investigations are required.

Figure 2.

Representative image showing positive decorin expression in a patient with a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (magnification, ×100).

Figure 3.

Representative image showing negative decorin expression in a patient with a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (magnification, ×100).

Discussion

The prognosis of MPNSTs has been reported to differ in the literature, with a 5-year survival rate ranging between 15 and 50% (1,3). The extremities are the most common site in which tumors occur. However, to the best of our knowledge, research focused on only extremity MPNSTs are extremely rare. In the present study, all the cases were primary extremity MPNSTs.

Investigations to examine the biomarkers for MPNSTs have been reported in the literature. Endo et al (10) reported that the inactivation of p14 (ARF), p15 (INK4b), and p16 (INK4a) genes indicated a poor prognosis in patients with MPNSTs. Bradtmöller et al (11) reported that the downregulation of phosphate and tensin homolog (PTEN) expression could contribute to malignant progression. Alaggio et al (12) reported that high expression of survivin correlated with a higher FNCLCC tumor grade and a lower survival probability in pediatric patients with MPNSTs. Fan et al (13) reported that the positive expression of E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Mdm2 (MDM2) and tumor protein p53 (TP53) indicated a lower disease-free survival rate. Ikuta et al (14) reported that hyaluronan may serve as a useful marker in differentiating MPNSTs from neurofibromas, and in identifying patients with a poor prognosis. Wang et al (15) indicated that patients who were S-100 protein-negative had a higher recurrence rate and a lower survival rate in patients with spinal MPNSTs. Kolberg et al (16) reported that survivin (BIRC5), thymidine kinase 1 (TK1) and topoisomerase 2-α (TOP2A) were upregulated in patients with MPNSTs with a poor prognosis.

However, all these prognostic biomarkers were discovered by the method of quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and/or immunohistochemical staining, which do not have the ability to widely filtrate the differential proteins. Other proteomics methods, including iTRAQ and SILAC, are costly, time-consuming and not always feasible, as they are limited by the insufficient available tags for the simultaneous discrimination of multiple samples. Label-free quantitative proteomics avoids these defects and provides a reliable and convenient study method. To the best of our knowledge, the use of label-free quantitative proteomics in the examination of MPNSTs has yet to be reported in the literature. The present study used this method to filtrate differential protein in patients with MPNSTs with different prognoses.

Decorin is a major extracellular matrix protein and a member of the small leucine-rich proteoglycan family, which serves an important role in the biological process of development, tissue repair and tumor growth by regulating proliferation, differentiation, adhesion and migration (17). Decorin has been reported to be associated with lung (18), breast (19), liver (20), pancreatic (21), colon (22), bladder (23), prostate (24) and oral (25) cancer.

However, to the best of our knowledge, there are limited studies on decorin in soft-tissue tumors. Salomäki et al (26) reported that decorin was a biomarker for distinguishing between benign and malignant vascular tumors. Cates et al (27) reported that decorin may be used in the differential diagnosis between intramuscular myxoma and low-grade myxofibrosarcoma.

Only the study by Matsumine et al (28) reported the association of decorin with the prognosis of soft-tissue sarcoma. The study investigated 77 soft-tissue tumors, including only 4 MPNSTs, by PCR and immunohistochemical staining, and concluded that a reduced decorin level was a useful biomarker of aggressiveness. In the present study, the 5-year survival rate of patients with positive expression of decorin was 78.57%, while the 5-year survival rate of patients with negative expression of decorin was 18.75% (P=0.0014). Therefore, in accordance with the aforementioned study, high expression levels of decorin resulted in a good prognosis in patients with MPNSTs. The present study included a greatly enlarged sample size and was specifically aimed at MPNST; however, the underlying mechanism involved requires further investigation. In addition, it is important to point out a limitation to the present study. Due to the rarity of MPNSTs, the samples obtained for investigation were limited, which may impact the reliability of the results.

Overall, in the present study, label-free quantitative proteomics and mass spectrometry were used to analyze MPNST FFPE tissue samples. It was concluded that a high level of decorin indicates a better prognosis in patients with MPNSTs. With further investigations, decorin may serve as a reliable prognostic biomarker for MPNSTs. Furthermore, by using label-free quantitative proteomics and MS, additional prognostic biomarkers for MPNSTs may be identified in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Shanghai Applied Protein Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), for their assistance in the bioinformatics analysis.

Funding

This study was supported by the Shanghai Clinical Center for Limb Function Reconstruction Project (grant no. 2017ZZ01006).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

XJ and CC collected the clinical data, performed the experiment and wrote the manuscript. LC and TK analysed the data. CY designed the experiment and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The present study was approved by the ethics committee of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Farid M, Demicco EG, Garcia R, Ahn L, Merola PR, Cioffi A, Maki RG. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Oncologist. 2014;19:193–201. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grobmyer SR, Reith JD, Shahlaee A, Bush CH, Hochwald SN. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: Molecular pathogenesis and current management considerations. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:340–349. doi: 10.1002/jso.20971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cashen DV, Parisien RC, Raskin K, Hornicek FJ, Gebhardt MC, Mankin HJ. Survival data for patients with malignant schwannoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;426:69–73. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000131256.82455.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawamura T, Nomura M, Tojo H, Fujii K, Hamasaki H, Mikami S, Bando Y, Kato H, Nishimura T. Proteomic analysis of laser-microdissected paraffin-embedded tissues: (1) Stage-related protein candidates upon non-metastatic lung adenocarcinoma. J Proteomics. 2010;73:1089–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Addis MF, Tanca A, Pagnozzi D, Crobu S, Fanciulli G, Cossu-Rocca P, Uzzau S. Generation of high-quality protein extracts from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Proteomics. 2009;9:3815–3823. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanca A, Addis MF, Pagnozzi D, Cossu-Rocca P, Tonelli R, Falchi G, Eccher A, Roggio T, Fanciulli G, Uzzau S. Proteomic analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung neuroendocrine tumor samples from hospital archives. J Proteomics. 2011;74:359–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang SK, Darfler MM, Nicholl MB, You J, Bemis KG, Tegeler TJ, Wang M, Wery JP, Chong KK, Nguyen L, Scolyer RA, Hoon DS. LC/MS-based quantitative proteomic analysis of paraffin-embedded archival melanomas reveals potential proteomic biomarkers associated with metastasis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Götz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Williams TD, Nagaraj SH, Nueda MJ, Robles M, Talón M, Dopazo J, Conesa A. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3420–3435. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D109–D114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endo M, Kobayashi C, Setsu N, Takahashi Y, Kohashi K, Yamamoto H, Tamiya S, Matsuda S, Iwamoto Y, Tsuneyoshi M, Oda Y. Prognostic significance of p14ARF, p15INK4b, and p16INK4a inactivation in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3771–3782. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradtmöller M, Hartmann C, Zietsch J, Jäschke S, Mautner VF, Kurtz A, Park SJ, Baier M, Harder A, Reuss D, et al. Impaired Pten expression in human malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alaggio R, Turrini R, Boldrin D, Merlo A, Gambini C, Ferrari A, Dall'igna P, Coffin CM, Martines A, Bonaldi L, et al. Survivin expression and prognostic significance in pediatric malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) PLoS One. 2013;8:e80456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan Q, Yang J, Wang G. Clinical and molecular prognostic predictors of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Clin Transl Oncol. 2014;16:191–199. doi: 10.1007/s12094-013-1061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikuta K, Urakawa H, Kozawa E, Arai E, Zhuo L, Futamura N, Hamada S, Kimata K, Ishiguro N, Nishida Y. Hyaluronan expression as a significant prognostic factor in patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2014;31:715–725. doi: 10.1007/s10585-014-9662-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang T, Yin H, Han S, Yang X, Wang J, Huang Q, Yan W, Zhou W, Xiao J. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) in the spine: A retrospective analysis of clinical and molecular prognostic factors. J Neurooncol. 2015;122:349–355. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1721-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolberg M, Høland M, Lind GE, Ågesen TH, Skotheim RI, Hall KS, Mandahl N, Smeland S, Mertens F, Davidson B, Lothe RA. Protein expression of BIRC5, TK1, and TOP2A in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours - A prognostic test after surgical resection. Mol Oncol. 2015;9:1129–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shintani K, Matsumine A, Kusuzaki K, Morikawa J, Matsubara T, Wakabayashi T, Araki K, Satonaka H, Wakabayashi H, Iino T, Uchida A. Decorin suppresses lung metastases of murine osteosarcoma. Oncol Rep. 2008;19:1533–1539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biaoxue R, Xiguang C, Hua L, Hui M, Shuanying Y, Wei Z, Wenli S, Jie D. Decreased expression of decorin and p57(KIP2) correlates with poor survival and lymphatic metastasis in lung cancer patients. Int J Biol Markers. 2011;26:9–21. doi: 10.5301/JBM.2011.6372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Araki K, Wakabayashi H, Shintani K, Morikawa J, Matsumine A, Kusuzaki K, Sudo A, Uchida A. Decorin suppresses bone metastasis in a breast cancer cell line. Oncology. 2009;77:92–99. doi: 10.1159/000228253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyasaka Y, Enomoto N, Nagayama K, Izumi N, Marumo F, Watanabe M, Sato C. Analysis of differentially expressed genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma using suppression subtractive hybridization. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:228–234. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Köninger J, Giese NA, di Mola FF, Berberat P, Giese T, Esposito I, Bachem MG, Büchler MW, Friess H. Overexpressed decorin in pancreatic cancer: Potential tumor growth inhibition and attenuation of chemotherapeutic action. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4776–4783. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1190-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nyman MC, Sainio AO, Pennanen MM, Lund RJ, Vuorikoski S, Sundström JT, Järveläinen HT. Decorin in human colon cancer: Localization in vivo and effect on cancer cell behavior in vitro. J Histochem Cytochem. 2015;63:710–720. doi: 10.1369/0022155415590830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Behi M, Krumeich S, Lodillinsky C, Kamoun A, Tibaldi L, Sugano G, De Reynies A, Chapeaublanc E, Laplanche A, Lebret T, et al. An essential role for decorin in bladder cancer invasiveness. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:1835–1851. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201302655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu W, Neill T, Yang Y, Hu Z, Cleveland E, Wu Y, Hutten R, Xiao X, Stock SR, Shevrin D, et al. The systemic delivery of an oncolytic adenovirus expressing decorin inhibits bone metastasis in a mouse model of human prostate cancer. Gene Ther. 2015;22:247–256. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nayak S, Goel MM, Bhatia V, Chandra S, Makker A, Kumar S, Agrawal SP, Mehrotra D, Rath SK. Molecular and phenotypic expression of decorin as modulator of angiogenesis in human potentially malignant oral lesions and oral squamous cell carcinomas. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2013;56:204–210. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.120366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salomäki HH, Sainio AO, Söderström M, Pakkanen S, Laine J, Järveläinen HT. Differential expression of decorin by human malignant and benign vascular tumors. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:639–646. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.950287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cates JM, Memoli VA, Gonzalez RS. Cell cycle and apoptosis regulatory proteins, proliferative markers, cell signaling molecules, CD209, and decorin immunoreactivity in low-grade myxofibrosarcoma and myxoma. Virchows Arch. 2015;467:211–216. doi: 10.1007/s00428-015-1778-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumine A, Shintani K, Kusuzaki K, Matsubara T, Satonaka H, Wakabayashi T, Iino T, Uchida A. Expression of decorin, a small leucine-rich proteoglycan, as a prognostic factor in soft tissue tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:411–418. doi: 10.1002/jso.20745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.