Abstract

Entosis is a homogeneous cell-in-cell phenomenon and a non-apoptotic cell death process. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have been used in the treatment of prostate cancer and have already demonstrated efficacy in a clinical setting. The present study investigated the role of entosis in prostate cancer treated with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor nintedanib. Prostate cancer cells were treated with nintedanib in vitro and entosis was observed. Mice xenografts were created to evaluate whether nintedanib is able to induce entosis in vivo. The reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction, western blotting and immunofluorescence were performed to investigate whether the entosis pathway is induced by nintedanib. It was also investigated whether entosis can contribute to cell survival and progression under nintedanib stress, and nintedanib was revealed to enhance prostate cancer cell entosis. Nintedanib-induced entosis in prostate cancer cells occurred through phosphoinositide 3-kinase/cell division cycle 42 (CDC42) inhibition, followed by the upregulation of epithelial (E-)cadherin and components of the Rho kinase (ROCK) signaling pathway. In addition, nintedanib-resistant cells exhibiting entosis had a higher invasive ability. In addition, in vivo treatment of mice xenografts with nintedanib also increased the expression of E-cadherin and components of the ROCK signaling pathway. Nintedanib can promote entosis during prostate cancer treatment by modulating the CDC42 pathway. Furthermore, prostate cancer cells acquired nintedanib resistance and survived by activating entosis.

Keywords: nintedanib, prostate cancer, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, cell division cycle 42, entosis

Introduction

In the USA, prostate cancer (Pca) was the second leading cause of cancer-associated mortality in men with 26,120 succumbing in 2015 (1). Specifically, patients with metastatic castrate-resistant Pca exhibit poor prognosis, with a median overall survival time of ~14 months (2). The majority of available therapies focus on controlling disease progression, including targeted therapy. Targeted therapies are drugs that are designed to target and inhibit cancer growth by interfering with specific molecular signaling pathways (3). Tyrosine kinase (TK) is an enzyme that transfers γ-phosphate groups from ATP to the hydroxy group of tyrosine residues on signal transduction molecules (4). Strict regulation of TK activity controls fundamental cell processes, such as the cell cycle, proliferation, differentiation, motility and cell survival (5). A previous study indicated that TKs are involved in prostate tumorigenesis and progression through the activation of receptor and non-receptor TKs (6). The fibroblast growth factor (FGF) axis is required for normal prostate development; however, it becomes aberrantly activated in Pca (7). The FGF receptor (FGFR) activates a downstream pathway cascade, including phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/cell division cycle 42 (CDC42) (8). CDC42 is a member of the Rho GTPase protein family that serves a key role in local actin organization through a number of kinase and non-kinase effector proteins (9). CDC42 activity is regulated by the cell cycle and controls certain mitotic processes, including kinetochore attachment and chromosome segregation (9). A recent study indicated that CDC42 is involved in the cell entosis process, and knockout of CDC42 expression induces entosis in breast cancer and promotes cancer progression (10). Known as cell cannibalism, entosis is described as the ingestion of live cells, resulting in the unusual appearance of whole cells contained within large vacuoles, or so-called ‘cell-in-cell’ structures (11). Entosis is frequently identified in human malignancies, which are associated with oncogenesis and tumor progression, such as breast cancer (10). It has been reported previously that entosis is particularly frequent in high-grade aggressive breast cancers with poor prognosis (10). In addition, enosis has also been identified in castration-resistant Pca and is therefore associated with a poor prognosis (12). Through entosis, winner tumor cells (engulfing cells) engulf and kill loser cells (engulfed cells), and benefit from their death, which is a mechanism whereby cells survive under stress and become more tumorigenic (10). Multiple molecules and pathways are involved in the entosis process, including epithelial (E-)cadherin and the RhoA/Rho kinase (ROCK) signaling pathway (13). RhoA is a member of the Ras superfamily of small GTP-binding proteins, whereas ROCKs are downstream target proteins of RhoA (13). RhoA activity and ROCK1/2 were accumulated in internalizing cells by contributing to myosin contraction (14).

Nintedanib, is a TK inhibitor (TKI) that can inhibit FGFR1-3, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFR)1-3, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)α/β, Src, Lck and Lyn, and a Phase II clinical trial has exhibited antitumor effects in patients with castration-resistant Pca (15). In another trial, the combination of nintedanib, docetaxel and prednisone led to a decrease from the baseline in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels and induced a partial response (16). However, in these two trials, certain patients did not respond to nintedanib, and certain tumors developed resistance and then became more aggressive, despite initially responding to nintedanib treatment.

In the present study, we hypothesized resistance would develop during the treatment of TKI nintedanib in Pca cells, and entosis may contribute this process. Therefore, the present study investigated the mechanism of resistance and the potential involved pathways.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The Pca cell lines 22RV1 (CRL-2505), LNCaP (CRL-1740), DU145 (HTB-81) and PC3 (CRL-1435) and 293 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) or Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) that were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. All drugs were purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA), and Pca cells were treated at the following concentrations: Nintedanib (3 µM for 4 weeks to develop resistance), PI3K inhibitor buparlisib (1.5 µM for 4 weeks) (17), protein kinase B (Akt) inhibitor MK2206 (10 µM for 4 weeks) (18), extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 inhibitor SCH772984 (3 µM for 4 weeks) (19), CDC42 inhibitor ML141 (2 µM for 4 weeks) (20), or ROCK1/2 inhibitor Y-27632 (10 µM for 1 week) (21). For drug treatment experiments, all the cells were seeded at a density of 1×105 cells/well in 6-well culture plates in the corresponding medium. Following 24 h of incubation at 37°C for attachment, the cells were treated with drugs.

Cell viability assay and drug half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) determination

Pca cells were seeded in 96-well plates (5,000 cells/well) and allowed to attach overnight at 37°C. Cells were treated with drugs for 72 h at 37°C. Cell viability was subsequently determined using a WST-1 assay (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Absorbance was determined using a Multimode Plate Reader at 440 and 690 nm (using 690 nm to remove background).

Immunofluorescence

22RV1 and DU145 cells were seeded on coverslips and then cultured with 3 µM nintedanib until they developed resistance (4 weeks). For the detection of RhoA, 22RV1 and DU145 cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 10 min and blocked for 20 min in PBS containing 1% (w/v) BSA-0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 at room temperature. A primary antibody (mouse monoclonal anti-RhoA; cat. no. sc-166399; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) was diluted 1:200 and incubated at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, the cells were incubated for 1 h with a rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) FITC antibody (4 µg/ml; cat. no. sc-358916; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) at room temperature and then mounted in antifade mounting medium with DAPI. Images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope at ×400 magnification (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Western blotting

Pca cell pellets were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation buffer with a proteinase inhibitor (cat. no. sc-24948; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). The samples were diluted to same quantities (20 µg) by the BCA assays and then loaded. Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels, and then transferred onto polyvinyl difluoride membranes (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature for 1 h, and then incubated with primary antibody (1:3,000) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with anti-Rabbit IgG (cat. no. ab205718; Abcam), or anti-mouse IgG (ab131368; Abcam). The proteins on the blot were detected using the Western Bright Enhanced Chemiluminescence western blotting detection kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). Equal sample loading was verified by the detection of GAPDH. The primary antibodies were as follows: Mouse monoclonal anti-β-catenin (cat. no. sc-7963; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse monoclonal anti-CDC42 (cat. no. sc-8401; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit monoclonal anti-cyclin D1 (cat. no. 2978; Cell signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-Akt (cat. no. sc-377556; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-Akt (cat. no. sc-271966; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit monoclonal anti-ROCK1 (cat. no. ab45171; Abcam), rabbit monoclonal anti-ROCK2 (cat. no. ab125025; Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-ERK1/2 (cat. no. sc-514302; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (cat. no. sc-81492, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit monoclonal anti-E-cadherin (cat. no. EPR699; Abcam) and mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (cat. no. sc-47724; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

Short interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection

22RV1 and DU145 cells were seeded at a density of 1×105 cells per well in 12-well culture plates, then transfected with anti-CDC42 siRNA or a scrambled probe (cat. no. sc-37007; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) at a final concentration of 40 nM using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The transfection efficiency was validated using the reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). The 5′-CCUCUACUAUUGAGAAACU-3′ and 3′-GGAGAUGAUAACUCUUUGA-5′ oligoribonucleotides were used to inhibit CDC42 synthesis. At 72 h after transfection, cells were collected and the RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) prior to RT-qPCR and western blotting to detect the results of inhibition.

Immunohistochemical staining (IHC)

Sections (5 µm) on glass slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated (Xylene: Twice, each for 5 min, 100% ethanol for 3 min, 95% ethanol for 3 min, 70% ethanol for 3 min, 50% ethanol for 3 min, wash slides in deionized water for 3 min). The sections were stained with the aforementioned antibodies (1:200 dilution) against CDC42 or E-cadherin at 4°C overnight and then incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-labeled dextran polymer coupled to an anti-mouse antibody at room temperature for 2 h. Cytoplasmic staining that was clearly distinguishable from the background was considered positive. The slides were reviewed twice by two independent investigators. Target protein expression was graded semi-quantitatively according to the staining score results (22), and the mean values were used for statistical analysis.

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR

RNA from the Pca cells was extracted using a RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) and cDNA was generated using a reverse transcription kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Candidate genes were measured using a RT-qPCR system according to the manufacturer's protocol (40 cycles as 93°C, 30 sec, 95°C, 30 sec, 55°C, 1 min, 68°C, 1 min). Primers used were: CDC42, 5′-CCCTGAAACAGCGTTGGGAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGGATGAACGATCCCTTTAGC-3′ (reverse); ROCK1, 5′-AACATGCTGCTGGATAAATCTGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGTATCACATCGTACCATGCCT-3′ (reverse); ROCK2, 5′-TCAGAGGTCTACAGATGAAGGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCAGGGGCTATTGGCAAAGG-3′ (reverse); E-cadherin, 5′-AGAACTTACCGCTACTTCTTGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGCCCACATACTGATAATCGGA-3′ (reverse); RhoA, 5′-AGCCTGTGGAAAGACATGCTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCAAACACTGTGGGCACATAC-3′ (reverse); and GAPDH, 5′-TGTGGGCATCAATGGATTTGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACACCATGTATTCCGGGTCAAT-3′ (reverse). The RNA concentrations in samples varied between 500 and 1,000 ng/µl, and the A260/A230 ratios were more than 2. A 500 ng amount of RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA. All PCRs were run in triplicate. The relative quantification of gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method and normalized to GAPDH expression (23).

Animal xenograft study

The present study was approved by the Hebei General Hospital Institutional Ethics Committee (Shijiazhuang, China). DU145 cells (106 cells) were mixed with Matrigel (1:1) and then subcutaneously injected into the right flanks of 20 male severe combined immunodeficient mice (8 weeks old). The dimensions of each tumor were determined directly with calipers every 3 days, and the volume was calculated by the following formula: Tumor volume=½ (length × width2). The care and treatment of experimental animals were in accordance with institutional guidelines (24). The mice were euthanized when their tumors exceeded 1 cm, and the diameter of the largest subcutaneous tumor was 1.3 cm. When the tumor volume reached 200 mm3, the mice were randomized into two groups (10 ×enografts/group) that received nintedanib (50 mg/kg/day dissolved in 5% dimethylsulfoxide) or a vehicle control by oral gavage (25). Tumor volumes were determined and growth curves were generated. At the end of the study, the animals were sacrificed via CO2 inhalation (20% of the chamber volume/min) and the tumors were collected.

Transwell invasion assay

Cell invasion assays were performed in a 24-well Transwell chamber (0.4 µm; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Nintedanib-resistant 22RV1 and DU145 cells or negative controls (matched cells without treatment) were added to the upper chamber (1×105 cells/ml). Following 24 h of incubation, the cells that passed through the filter were fixed and stained using 0.1% crystal violet at room temperature for 20 min. The numbers of invading cells were counted in five randomly selected fields under an Olympus IX71 microscope under ×400 magnification.

Plasmid construction and transfection

Full-length human CDC42 cDNAs (OriGene Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) were sequenced and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 expression vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A lentiviral vector expressing tagged CDC42 was generated using the ViraPower™ T-Rex™ system (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Subsequently, 293 cells were transfected using the calcium phosphate precipitation method and Pca cells were transfected using the FuGENE Transfection Reagent (Roche Diagnostics).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean of three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher's least-significant difference post hoc test, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests or Student's t-test was used for the statistical analysis using R (version 3.4.3) developed by R Core Team. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Nintedanib inhibits Pca cell proliferation in vitro

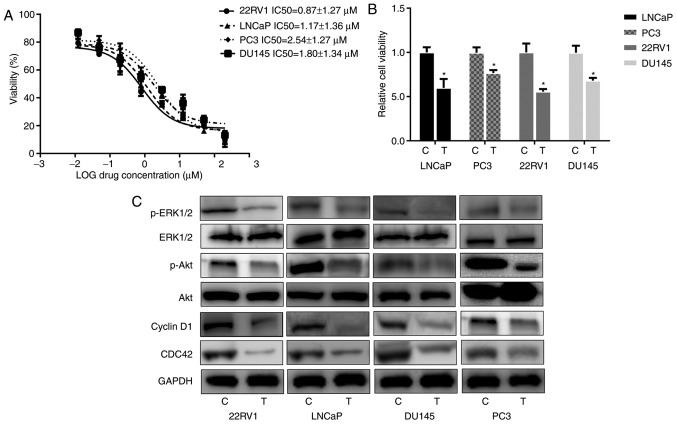

Different Pca cell lines were selected for experimentation including LNCaP, PC3, 22RV1 and DU145. The data revealed that IC50 values for nintedanib in the different cell lines varied between 0.87 and 2.54 µM (Fig. 1A). The Pca cells were then treated with 3 µM nintedanib, and the viability assay revealed that the cell proliferation was inhibited by nintedanib in vitro, which indicated that nintedanib is capable of suppressing the proliferation of these cells (Fig. 1B). The antitumor effects of nintedanib could be attributed to its selective anti-pan-receptor TKI activity. Nintedanib is already known as an inhibitor of TKs, by binding to the ATP-binding site in the cleft between the N- and C-terminal lobes of the kinase domain (25). At the pharmacological level, nintedanib can inhibit TKs, which include all three VEGFR subtypes (IC50, 13–34 nmol/l), PDGFRα and PDGFRβ (IC50, 59 and 65 nmol/l), and FGFR types 1, 2 and 3 (IC50, 69, 37 and 108 nmol/l), respectively (25). Marked death of Pca cells was not observed following treatment with 3 µM nintedanib. Instead, in the 2 days following treatment, the cells maintained proliferation, prior to suspension of cell proliferation. Consistent with the proliferation assay results, nintedanib treatment suppressed the expression of proteins downstream of PI3K, including CDC42, phospho-Akt and phospho-ERK1/2 (Fig. 1C). Cyclin D1 expression was also decreased due to nintedanib treatment.

Figure 1.

Effects of nintedanib treatment on Pca cell proliferation in vitro. (A) Pca cells were treated with the indicated doses of nintedanib (concentrations ranged between 0.012 and 200 µM) and the IC50 values were calculated in different Pca cell lines. (B) Cell viability of Pca cells treated with nintedanib (3 µM) for 72 h determined using a WST-1 assay. The different treatment groups were compared with the control. *P<0.05 vs. control (Student's t-test). (C) Western blot analysis revealed that nintedanib inhibited the phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling pathway and its downstream pathways in Pca cells. Pca, prostate cancer; IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; C, control; T, treatment; p-, phospho-; ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; Akt, protein kinase B; CDC42, cell division cycle 42.

Activation of entosis mediates acquired resistance to nintedanib

To identify potential mechanisms of acquired resistance to nintedanib in Pca, the present study established different cell lines with acquired resistance by exposing the cells to 3 µM nintedanib. All Pca cells exhibited marked resistance to nintedanib (Fig. 2A) at 4 weeks after nintedanib treatment. Immunoblotting revealed that β-catenin expression increased markedly in all cell lines examined when compared with cells that did not undergo treatment (Fig. 2B); this is relevant as β-catenin is a molecule that contributes to cell adherens junctions (26). The nintedanib-resistant cells were observed under a microscope and exhibited the cell-in-cell phenomenon morphology, which refers to one or more viable cells present inside other cells, or more cells involved in sequential engulfment (Fig. 2C). These were similar to the entotic structures identified in other studies (10,12). Notably, the engulfing cells morphologically transformed into phagocyte-like cells, with pseudopodia and a multipolar shape. Under a fluorescence microscope, positive expression of RhoA in nintedanib-resistant Pca cells was observed, which is a marker of entosis (Fig. 2B and C). In addition, the size of the cell and the nucleus markedly increased in Pca cells treated with nintedanib (27).

Figure 2.

Treatment with 3 µM nintedanib for 4 weeks promoted Pca cell entosis. (A) Entosis developed when Pca cells were treated with nintedanib. Engulfing cells were morphologically transformed into phagocytes with pseudopodia, a multipolar shape and multiple nuclei (magnification, ×200). (B) β-catenin expression was increased compared with the cells without nintedanib treatment. (C) Fluorescence images of 22RV1 and DU145 cells treated with nintedanib. Cells were incubated with antibody against RhoA and visualized under a fluorescence microscope (magnification, ×400). The immunofluorescence images revealed entosis-like changes. Pca, prostate cancer; C, control; T, treatment.

Taken together, these results demonstrated that treatment of Pca cells with nintedanib may lead to entosis. Therefore, in the subsequent experiments, only the 22RV1 (androgen receptor-positive) and DU145 (androgen receptor-negative) Pca cell lines were selected to further investigate the mechanism of entosis induced by nintedanib.

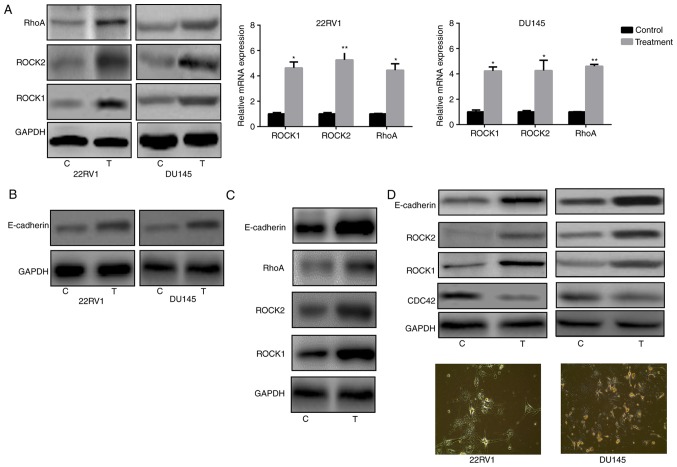

Increased Rho/ROCK and E-cadherin in Pca cells treated with nintedanib

It is well established that entosis is regulated by the RhoA/ROCK1/2 signaling pathway and E-cadherin (28). Therefore, RhoA and ROCK1/2 expression was analyzed in Pca cells and it was observed that nintedanib treatment of 22RV1 and DU145 cells led to an increase in the expression of RhoA, ROCK1 and ROCK2 (Fig. 3A). The present study also evaluated E-cadherin expression in Pca cells following treatment with nintedanib. The results indicated that E-cadherin expression was also significantly increased (Fig. 3B). Since E-cadherin is another biomarker of the entosis phenomenon, the experiment presented in Fig. 3B was attempted to verify that entosis developed following treatment with nintedanib, accompanied by an increased E-cadherin level. Although PC3 is a Pca cell line with a deep PTEN deletion and Akt activation, treatment of PC3 cells with nintedanib still increased the expression of ROCK1/2 and E-cadherin (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Nintedanib induced the ROCK pathway and E-cadherin expression (3 µM for 4 weeks) by western blot analysis and the reverse transcription- quantitative polymerase chain reaction. (A) ROCK pathway-associated molecule expression following nintedanib treatment. (B) E-cadherin expression following nintedanib treatment. (C) Treatment of PC3 cells with nintedanib increased ROCK1/2 and E-cadherin expression. (D) Buparlisib treatment induced Pca cell entosis and increased ROCK1/2 and E-cadherin expression, whereas CDC42 levels decreased in Pca cells (1.5 µM, treatment for 4 weeks, ×400 magnification). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control (Student's t-test). ROCK, Rho kinase; E-cadherin, epithelial cadherin; Pca, prostate cancer; CDC42, cell division cycle 42; C, control; T, treatment.

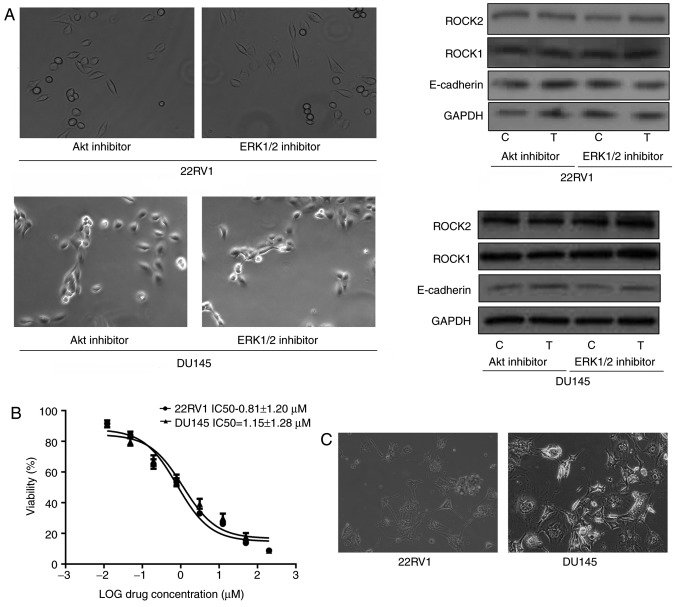

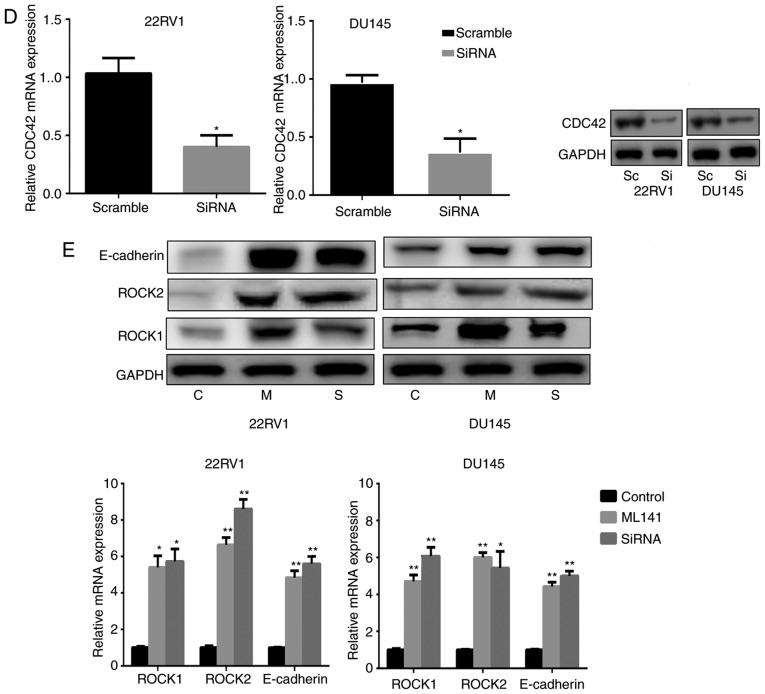

Nintedanib regulates entosis via the PI3K/CDC42 signaling pathway

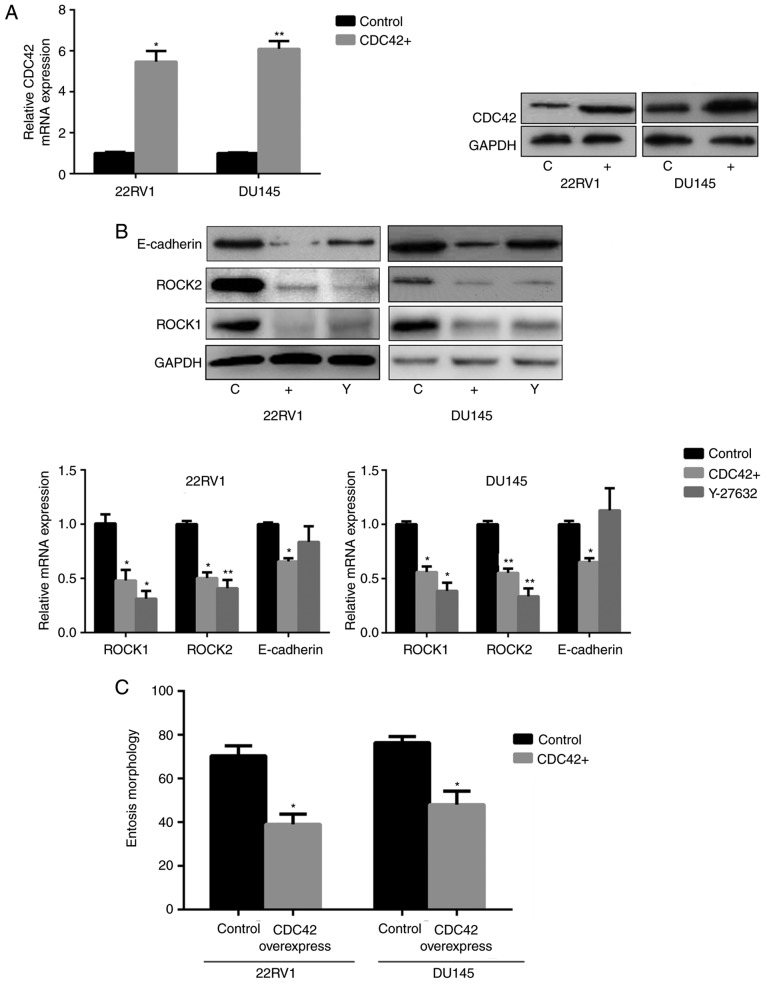

Nintedanib inhibits FGFR in Pca cells, and inhibits the activation of its downstream pathways, including PI3K. The data indicated that nintedanib inhibited CDC42, Akt and ERK1/2 expression (downstream of PI3K) in 22RV1 and DU145 cells (Fig. 1C). In addition, CDC42 was inhibited when the cells were treated with the PI3K inhibitor buparlisib (Fig. 3D). However, cells in which either Akt or ERK1/2 were inhibited neither developed entosis nor exhibited an increase in ROCK1/2 or E-cadherin expression (Fig. 4A). Therefore, we hypothesized that nintedanib could induce entosis via the CDC42 pathway. Consequently, Pca cells were treated with a CDC42 inhibitor, and observed that entosis morphology developed following 2 weeks of treatment along with increased ROCK1/2 and E-cadherin expression (Fig. 4B and C). Furthermore, increased ROCK1/2 and E-cadherin expression were also observed in CDC42-knockdown cells (Fig. 4D and E). Subsequently CDC42 was overexpressed in Pca cells via transfection (Fig. 5A). The results demonstrated that ROCK1/2 expression decreased under CDC42 overexpression, which was also observed in cells treated with the ROCK1/2 inhibitor Y-27632. E-cadherin expression also decreased in cells overexpressing CDC42 (Fig. 5B). In addition, nintedanib-associated entosis was significantly inhibited in cells overexpressing CDC42 compared with controls (P<0.05, Fig. 5C). Therefore, PI3K/CDC42 negatively regulated ROCK1/2 and E-cadherin expression.

Figure 4.

Decreased CDC42 induces entosis by promoting the ROCK1/2 signaling pathway and E-cadherin expression in Pca cells (×400 magnification). (A) No entosis morphology or increased ROCK1/2 or E-cadherin expression was observed in Pca cells treated with Akt inhibitor (MK2206; 10 µM) or ERK1/2 inhibitor (SCH772984; 3 µM) for 4 weeks, respectively. (B) IC50 values of the CDC42 inhibitor ML141 in the Pca cell lines. (C) Entosis-like morphology of Pca cells under ML141 pressure (2 µM for 4 weeks). (D) siRNA knockdown of CDC42 expression at the mRNA and protein level. *P<0.05 vs. control (Student's t-test) (E) CDC42 siRNA and ML141 (2 µM) promote ROCK1/2 expression and E-cadherin expression (following treatment for 1 week). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control (one-way analysis of variance followed by Fisher's least-significant difference test). CDC42, cell division cycle 42; ROCK, Rho kinase; Pca, prostate cancer; Akt, protein kinase B; ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; siRNA, short interfering RNA; E-cadherin, epithelial cadherin; C, control; T, treatment; M, ML141 treatment; S/Si, siRNA treatment; Sc, scrambled.

Figure 5.

CDC42 overexpression blocks entosis in Pca cells. (A) Overexpression of CDC42 in Pca cells at the mRNA and protein level. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control (Student's t-test). (B) CDC42 overexpression decreased ROCK1/2 and E-cadherin expression at the mRNA and protein levels. The ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (10 µM for 1 week) was used as a control. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control (one-way analysis of variance followed by Fisher's least-significant difference test). (C) Effects of CDC42 overexpression on entosis in vitro following 4 weeks of nintedanib pressure (3 µM). A total of 500 randomly selected cells per condition were scored. *P<0.05 vs. control (Student's t-test). CDC42, cell division cycle 42; Pca, prostate cancer; ROCK, Rho kinase; E-cadherin, epithelial cadherin; C, control; +, CDC42+; Y, Y-27632.

Entosis promotes invasion in under nintedanib stress

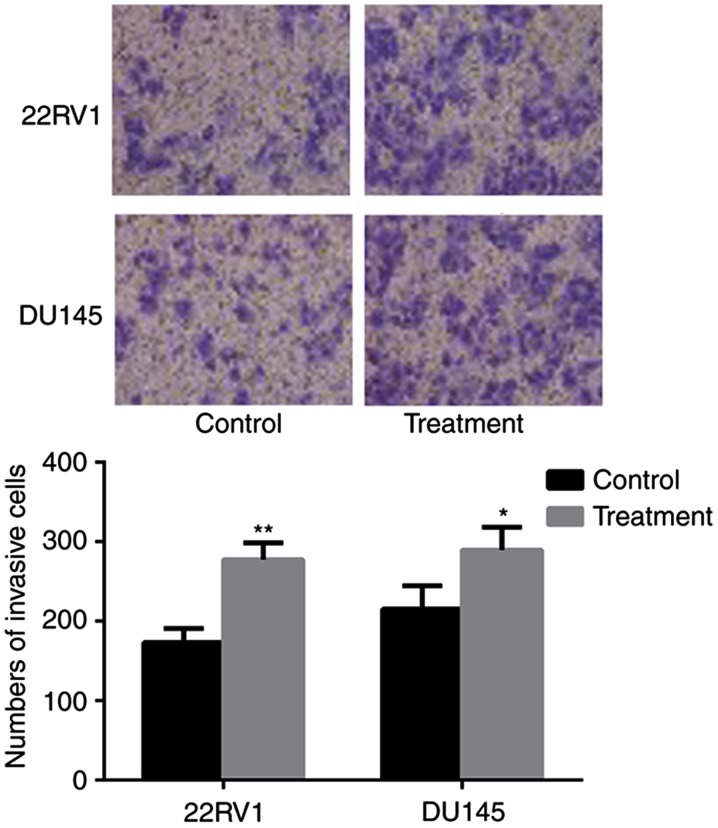

The consequences of nintedanib-induced entosis on cell invasion ability were investigated. Over the extended period (8 weeks) of treatment, the cell population was continuously decreased by the frequent occurrence of entosis, apoptosis and necrosis, until the cells developed nintedanib resistance and avoided cell death. Pca cells with passage-matched resistant cells as controls were cultured, and the Transwell invasion assay indicated that the invasive ability of nintedanib-resistant Pca cells had significantly increased (P<0.05; Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Entosis results in significantly increased Pca cell invasion capacity (×400 magnification). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. control (Student's t-test).

Entosis in a mouse Pca xenograft

To further investigate the role of nintedanib in Pca cell entosis, mouse xenografts by were created by subcutaneously injecting DU145 cells. Mice were treated with nintedanib, and it was observed that nintedanib can attenuate the growth of tumors compared with that using the placebo. IHC indicated that the expression of E-cadherin was increased in the nintedanib-treated tumors compared with in the controls, whereas CDC42 expression was markedly decreased in nintedanib-treated tumors (Fig. 7). These results were consistent with the data obtained from the in vitro cell lines, which revealed that nintedanib could induce entosis via the upregulation of E-cadherin expression and the ROCK1/2 signaling pathway.

Figure 7.

Effect of nintedanib on tumor volumes, and CDC42 and E-cadherin expression levels in mouse xenografts. (A) Growth curves for xenografts in each group. *P<0.05 vs. control (two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests). (B) Quantitative immunohistochemistry analysis and representative microscopic fields for CDC42 and E-cadherin staining (magnification, ×200). The expression of CDC42 decreased, whereas the expression of E-cadherin increased in nintedanib-treated mice, compared with controls. **P<0.01 vs. control (Student's t-test). CDC42, cell division cycle 42; E-cadherin, epithelial cadherin.

Discussion

Nintedanib, a pan-inhibitor of TKs including FGFR, has been evaluated in clinical trials for several types of cancer, including prostate, lung and colorectal cancer (15,29,30). In a randomized Phase II trial, nintedanib combined with afatinib decreased PSA levels in ~50% of patients with castration-resistant Pca (15). In another study, nintedanib attenuated Pca progression in transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate mice (31). However, it is unknown how Pca cells survive and develop resistance under nintedanib pressure. The results of the present study indicated that: i) Nintedanib is able to inhibit Pca cell proliferation and decrease the growth of xenografts; ii) resistance to nintedanib will develop during in vitro and vivo treatment; and iii) nintedanib induces Pca cell entosis via the upregulation of E-cadherin and ROCK1/2 through the PI3K/CDC42 signaling pathway.

It was observed multiple cancer cells were treated with nintedanib at concentrations ranging between 1 and 5 µM (32), the results revealed that nintedanib inhibited cell proliferation without a toxic response. In the present study that cells that have developed nintedanib resistance display entosis. Nintedanib could block FGFR and then inhibit the downstream PI3K/CDC42 signaling pathway to promote entosis. A previous study identified that the activated PI3K signaling pathway promotes Pca cell proliferation and facilitates cell survival (33). In addition, activated PI3K was observed to promote aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells to tolerate nutrient starvation (34). In the present study, treatment with nintedanib and blocking FGFR downregulated PI3K, and also blocked its downstream pathways. CDC42 is an important molecule in the PI3K downstream signaling pathway, and the results of the present study have demonstrated that treatment with nintedanib decreased the expression of CDC42, and this effect was also observed in Pca cells treated with the PI3K inhibitor buparlisib. There are two isoforms produced by alternative splicing from CDC42 gene: CDC42a and CDC42b and to date, the functional differences between the two isoforms remains unclear; however, it has been established that the two isoforms can stimulate filopodia formation (35). In the present study, the primers used reflect the total expression level of the two isoforms of CDC42 under nintedanib pressure. However, as the focus of the present study was on the resistance of Pca cells to the nintedanib and the entosis phenomenon, differences in the expression of the CDC42 isoforms were not investigated. The PI3K/CDC42 is a classic signaling pathway in multiple cell events, including cell proliferation and movement, and serves an important role in cancer by promoting cancer progression and metastasis (36). Studies have demonstrated that blocking CDC42 can inhibit tumor growth and prolong patient survival. A study by Humphries-Bickley et al (37) suggested that blocking CDC42 can inhibit breast cancer cell migration, viability and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. A study of Guo et al (38) demonstrated that R-ketorolac blocked CDC42 and Rac1 and then inhibited ovarian cancer growth, adhesion, migration and invasion.

PI3K/CDC42 can regulate phagosomes and promote entotic vacuole maturation by regulating the ROCK signaling pathway and E-cadherin expression (10,27,39–41). Durgan et al (10) revealed that knockout of CDC42 expression induced entosis in breast cancer, and significant mitotic deadhesion and rounding was also observed following the depletion of CDC42, and these phenotypes were associated with a prominent increase in RhoA/ROCK1/2 activity. As a downregulator of the RhoA/ROCK1/2 signaling pathway, blocking CDC42 may induce RhoA/ROCK1/2 activation and promote entosis. The activated ROCK pathway would induce the accumulation of actomyosin, increase actomyosin contractility, and be indispensable for cell-in-cell formation (39). Instead of engulfing cells, the increased RhoA/ROCK1/2 activity is located in internalizing cells. In addition, actin and myosin contractility are the driving force for entosis within ‘loser’ cells (40), whereas a ROCK1/2 inhibitor can abolish the entosis process between cells in mixed culture experiments (27), which was also observed in the present study. Additionally, E-cadherin expression was also increased in Pca cells when CDC42 was blocked. The study of Izumi et al (41) identified that CDC42 downregulation increased E-cadherin expression and in turn promoted cancer progression. E-cadherin is one of the principal components of adherens junctions in epithelial cells that connects the actin cytoskeleton of neighboring cells (42). It has previously been established that E-cadherin is involved in cancer progression, metastasis, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and the cancer engulfment process (43). In breast cancer, researchers identified that entosis is induced by the establishment of epithelial adhesion through the expression of E-/placental cadherins (28). In addition, another study focused on the cell entosis association in natural killer cells and tumor cells, and observed that E-cadherin-mediated cell junctions were required for the engulfment process (44).

CDC42 serves a role in cell division, and when CDC42 is blocked, cell division is disrupted (45). However, blocking cell mitosis would allow for cell entosis. Division in engulfing cells can be disrupted by entosis by blocking CDC42; thus, entosis would be completed during engulfing cells mitosis (10,46). The engulfed nucleus and mitosis-disrupted cells would create multi-nucleated cells that can contribute to the generation of aneuploidy, particularly when multipolar spindles are involved (47). Aneuploidy cells have more genetic instability, randomly distributed chromosomes and chromosome breakage (48). Aneuploidy also facilities cancer cells to gain extra copies to resist drug pressures (49). Gene copy number alterations are a major mechanism for signaling pathway modifications, as increasing the copy number can amplify gene expression, which would promote cell survival under the pressure of specific inhibitors and allow the cells to tolerate the inhibition (49). For example, in a previous study, lung cancer was treated with an epidermal growth factor receptor TKI, and the results demonstrated that MET amplification, accompanied by KRAS amplification, can result in TKI therapy failure (50). Owing to the induced aneuploidy, entosis could contribute to cancer progression. The study of Schwegler et al (51) identified that entosis occurs most frequently in high-grade breast cancers with increased recurrence and decreased overall patient survival rates. In the present study, the results of the Transwell assay indicated that entosis-like cells have increased invasive abilities.

However, there are some limitations to the present study. Namely, the anti-TK activity of nintedanib on Pca cells was not investigated, which requires further research in order to explain the effect of anti-TK on the entosis phenomenon.

Nintedanib is effective for inhibiting Pca cell proliferation; however, resistance develops during the course of treatment through the activation of entosis. In addition, the nintedanib-induced entosis status is determined by ROCK activity and E-cadherin protein expression levels.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Key Technology Research and Development Program of Hebei Province (grant no. 14277774D).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Hebei General Hospital Institutional Ethics Committee (Shijiazhuang, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JL performed certain experiments and wrote the paper. LW and YZ completed the majority of the experiments. SL, FS, GW, TY, DW, LG and HX contributed to the idea and conception of this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, Stein KD, Alteri R, Jemal A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:271–289. doi: 10.3322/caac.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madan RA, Gulley JL, Schlom J, Steinberg SM, Liewehr DJ, Dahut WL, Arlen PM. Analysis of overall survival in patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with vaccine, nilutamide, and combination therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4526–4531. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hait WN, Hambley TW. Targeted cancer therapeutics. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1263–1267. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2000;103:211–225. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prenzel N, Fischer OM, Streit S, Hart S, Ullrich A. The epidermal growth factor receptor family as a central element for cellular signal transduction and diversification. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8:11–31. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai B, Chen H, Guo S, Yang X, Linn DE, Sun F, Li W, Guo Z, Xu K, Kim O, et al. Compensatory upregulation of tyrosine kinase Etk/BMX in response to androgen deprivation promotes castration-resistant growth of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5587–5596. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniele G, Corral J, Molife LR, de Bono JS. FGF receptor inhibitors: Role in cancer therapy. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14:111–119. doi: 10.1007/s11912-012-0225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muha V, Müller HA. Functions and mechanisms of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signalling in drosophila melanogaster. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:5920–5937. doi: 10.3390/ijms14035920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qadir MI, Parveen A, Ali M. Cdc42: Role in cancer management. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2015;86:432–439. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durgan J, Tseng YY, Hamann JC, Domart MC, Collinson L, Hall A, Overholtzer M, Florey O. Mitosis can drive cell cannibalism through entosis. Elife. 2017;6:e27134. doi: 10.7554/eLife.27134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun Q, Huang H, Overholtzer M. Cell-in-cell structures are involved in the competition between cells in human tumors. Mol Cell Oncol. 2015;2:e1002707. doi: 10.1080/23723556.2014.1002707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen S, Shang Z, Zhu S, Chang C, Niu Y. Androgen receptor enhances entosis, a non-apoptotic cell death, through modulation of Rho/ROCK pathway in prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2013;73:1306–1315. doi: 10.1002/pros.22676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sahai E, Olson MF, Marshall CJ. Cross-talk between Ras and Rho signalling pathways in transformation favours proliferation and increased motility. EMBO J. 2001;20:755–766. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishna S, Overholtzer M. Mechanisms and consequences of entosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:2379–2386. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2207-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molife LR, Omlin A, Jones RJ, Karavasilis V, Bloomfield D, Lumsden G, Fong PC, Olmos D, O'Sullivan JM, Pedley I, et al. Randomized phase II trial of nintedanib, afatinib and sequential combination in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Future Oncol. 2014;10:219–231. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bousquet G, Alexandre J, Le Tourneau C, Goldwasser F, Faivre S, de Mont-Serrat H, Kaiser R, Misset JL, Raymond E. Phase I study of BIBF 1120 with docetaxel and prednisone in metastatic chemo-naive hormone-refractory prostate cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1640–1645. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu L, Dong X. Complex impacts of PI3K/AKT inhibitors to androgen receptor gene expression in prostate cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Somnay Y, Simon K, Harrison AD, Kunnimalaiyaan S, Chen H, Kunnimalaiyaan M. Neuroendocrine phenotype alteration and growth suppression through apoptosis by MK-2206, an allosteric inhibitor of AKT, in carcinoid cell lines in vitro. Anticancer Drugs. 2013;24:66–72. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3283584f75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris EJ, Jha S, Restaino CR, Dayananth P, Zhu H, Cooper A, Carr D, Deng Y, Jin W, Black S, et al. Discovery of a novel ERK inhibitor with activity in models of acquired resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:742–750. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maes H, Van Eygen S, Krysko DV, Vandenabeele P, Nys K, Rillaerts K, Garg AD, Verfaillie T, Agostinis P. BNIP3 supports melanoma cell migration and vasculogenic mimicry by orchestrating the actin cytoskeleton. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1127. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chatterjee S, Schmidt S, Pouli S, Honisch S, Alkahtani S, Stournaras C, Lang F. Membrane androgen receptor sensitive Na+/H+ exchanger activity in prostate cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:1571–1579. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Detre S, Saclani Jotti G, Dowsett M. A ‘quickscore’ method for immunohistochemical semiquantitation: Validation for oestrogen receptor in breast carcinomas. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:876–878. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.9.876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hathcock KS, Farrington L, Ivanova I, Livak F, Selimyan R, Sen R, Williams J, Tai X, Hodes RJ. The requirement for pre-TCR during thymic differentiation enforces a developmental pause that is essential for V-DJbeta rearrangement. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallace J. Humane endpoints and cancer research. ILAR J. 2000;41:87–93. doi: 10.1093/ilar.41.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hilberg F, Roth GJ, Krssak M, Kautschitsch S, Sommergruber W, Tontsch-Grunt U, Garin-Chesa P, Bader G, Zoephel A, Quant J, et al. BIBF 1120: Triple angiokinase inhibitor with sustained receptor blockade and good antitumor efficacy. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4774–4782. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamann JC, Surcel A, Chen R, Teragawa C, Albeck JG, Robinson DN, Overholtzer M. Entosis is induced by glucose starvation. Cell Rep. 2017;20:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun Q, Luo T, Ren Y, Florey O, Shirasawa S, Sasazuki T, Robinson DN, Overholtzer M. Competition between human cells by entosis. Cell Res. 2014;24:1299–1310. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun Q, Cibas ES, Huang H, Hodgson L, Overholtzer M. Induction of entosis by epithelial cadherin expression. Cell Res. 2014;24:1288–1298. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riesco-Martinez MC, Sanchez-Torre A, Garcia-Carbonero R. Safety and efficacy of nintedanib for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26:1295–1305. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2017.1385762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabasa M, Ikemori R, Hilberg F, Reguart N, Alcaraz J. Nintedanib selectively inhibits the activation and tumour- promoting effects of fibroblasts from lung adenocarcinoma patients. Br J Cancer. 2017;117:1128–1138. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.da Silva RF, Nogueira-Pangrazi E, Kido LA, Montico F, Arana S, Kumar D, Raina K, Agarwal R, Cagnon VHA. Nintedanib antiangiogenic inhibitor effectiveness in delaying adenocarcinoma progression in Transgenic Adenocarcinoma of the Mouse Prostate (TRAMP) J Biomed Sci. 2017;24:31. doi: 10.1186/s12929-017-0334-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kutluk Cenik B, Ostapoff KT, Gerber DE, Brekken RA. BIBF 1120 (nintedanib), a triple angiokinase inhibitor, induces hypoxia but not EMT and blocks progression of preclinical models of lung and pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:992–1001. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raja Singh P, Sugantha Priya E, Balakrishnan S, Arunkumar R, Sharmila G, Rajalakshmi M, Arunakaran J. Inhibition of cell survival and proliferation by nimbolide in human androgen-independent prostate cancer (PC-3) cells: Involvement of the PI3K/Akt pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2017;427:69–79. doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2898-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elstrom RL, Bauer DE, Buzzai M, Karnauskas R, Harris MH, Plas DR, Zhuang H, Cinalli RM, Alavi A, Rudin CM, Thompson CB. Akt stimulates aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3892–3899. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He X, Yuan C, Yang J. Regulation and functional significance of CDC42 alternative splicing in ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:29651–29663. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murga C, Zohar M, Teramoto H, Gutkind JS. Rac1 and RhoG promote cell survival by the activation of PI3K and Akt, independently of their ability to stimulate JNK and NF-kappaB. Oncogene. 2002;21:207–216. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Humphries-Bickley T, Castillo-Pichardo L, Hernandez-O'Farrill E, Borrero-Garcia LD, Forestier-Roman I, Gerena Y, Blanco M, Rivera-Robles MJ, Rodriguez-Medina JR, Cubano LA, et al. Characterization of a Dual Rac/Cdc42 inhibitor MBQ-167 in metastatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16:805–818. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo Y, Kenney SR, Muller CY, Adams S, Rutledge T, Romero E, Murray-Krezan C, Prekeris R, Sklar LA, Hudson LG, Wandinger-Ness A. R-ketorolac targets Cdc42 and Rac1 and alters ovarian cancer cell behaviors critical for invasion and metastasis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:2215–2227. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamada S, Nelson WJ. Localized zones of Rho and Rac activities drive initiation and expansion of epithelial cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:517–527. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Purvanov V, Holst M, Khan J, Baarlink C, Grosse R. G-protein-coupled receptor signaling and polarized actin dynamics drive cell-in-cell invasion. Elife. :32014. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Izumi G, Sakisaka T, Baba T, Tanaka S, Morimoto K, Takai Y. Endocytosis of E-cadherin regulated by Rac and Cdc42 small G proteins through IQGAP1 and actin filaments. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:237–248. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baum B, Georgiou M. Dynamics of adherens junctions in epithelial establishment, maintenance, and remodeling. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:907–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petrova YI, Schecterson L, Gumbiner BM. Roles for E-cadherin cell surface regulation in cancer. Mol Biol Cell. 2016;27:3233–3244. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e16-01-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang S, Guo Z, Xia P, Liu T, Wang J, Li S, Sun L, Lu J, Wen Q, Zhou M, et al. Internalization of NK cells into tumor cells requires ezrin and leads to programmed cell-in-cell death. Cell Res. 2009;19:1350–1362. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Melendez J, Grogg M, Zheng Y. Signaling role of Cdc42 in regulating mammalian physiology. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2375–2381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.200329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krajcovic M, Overholtzer M. Mechanisms of ploidy increase in human cancers: A new role for cell cannibalism. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1596–1601. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krajcovic M, Johnson NB, Sun Q, Normand G, Hoover N, Yao E, Richardson AL, King RW, Cibas ES, Schnitt SJ, et al. A non-genetic route to aneuploidy in human cancers. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:324–330. doi: 10.1038/ncb2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guerrero AA, Gamero MC, Trachana V, Fütterer A, Pacios-Bras C, Díaz-Concha NP, Cigudosa JC, Martínez-AC, van Wely KH. Centromere-localized breaks indicate the generation of DNA damage by the mitotic spindle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4159–4164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912143106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang YC, Amon A. Gene copy-number alterations: A cost-benefit analysis. Cell. 2013;152:394–405. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D, Digumarthy S, Turke AB, Fidias P, Bergethon K, Shaw AT, Gettinger S, Cosper AK, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:75ra26. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwegler M, Wirsing AM, Schenker HM, Ott L, Ries JM, Büttner-Herold M, Fietkau R, Putz F, Distel LV. Prognostic value of homotypic cell internalization by nonprofessional phagocytic cancer cells. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:359392. doi: 10.1155/2015/359392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.