Abstract

Posttranslational modifications (PTM) including glycosylation, phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation and ubiquitination dynamically alter the proteome. The evolutionarily conserved enzymes O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase are responsible for the addition and removal, respectively, of the nutrient-sensitive PTM of protein serine and threonine residues with O-GlcNAc. Indeed, the O-GlcNAc modification acts at every step in the “central dogma” of molecular biology and alters signaling pathways leading to amplified or blunted biological responses. The cellular roles of OGT and the dynamic PTM O-GlcNAc have been clarified with recently developed chemical tools including high-throughput assays, structural and mechanistic studies and potent enzyme inhibitors. These evolving chemical tools complement genetic and biochemical approaches for exposing the underlying biological information conferred by O-GlcNAc cycling.

Keywords: O-GlcNAc, O-GlcNAc transferase, OGT’s activity assays, OGT’s catalytic mechanism, OGT’s inhibitors

Introduction

The modification of serine and threonine residues of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins by the monosaccharide, 2-acetamideo-2-deoxy-D-glucopyranose (GlcNAc) through a β-glycosidic linkage (O-linked N-acetylglucosamine; O-GlcNAc) is a notable post-translational glycosylation. O-GlcNAc is present in all intracellular compartments with a particular abundance on nuclear proteins. Its addition and removal is a dynamic process, turning over more rapidly than the polypeptide backbone of the proteins it modifies. Its rapid, continual cycling poises the modification to influence diverse cellular processes including nutrient signaling (Yang et al., 2008), regulation of gene transcription and translation (Sinclair et al., 2009), neural development (Rex-Mathes et al., 2001), stress response (Zachara et al., 2004) and cell division (Slawson et al., 2005).

In mammals, only two genes encode the evolutionarily conserved nucleocytoplasmic enzymes responsible for the addition and removal of O-GlcNAc. Uridine diphospho-N-acetyl-glucosamine:polypeptide β-N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase, termed O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT), uses the donor substrate uridine diphospho-2-acetamideo-2-deoxy-D-glucopyranose (UDP-GlcNAc) to add the monosaccharide to target protein serine and threonine residues (Haltiwanger et al., 1990; Kreppel et al., 1997; Lubas et al., 1997). A glycoside hydrolase, β-N-acetylglucosaminidase, termed O-GlcNAcase (OGA), returns glycosylated proteins to their unmodified state by removing O-GlcNAc (Gao et al., 2001). Although this review focuses on the protein responsible for the addition of the ubiquitous nuclear and cytoplasmic O-GlcNAc, we note a third enzyme that is located in the secretory pathway, eOGT, adds O-GlcNAc to a small subset of cell surface proteins (Müller et al., 2013; Sakaidani et al., 2012; Shaheen et al., 2013).

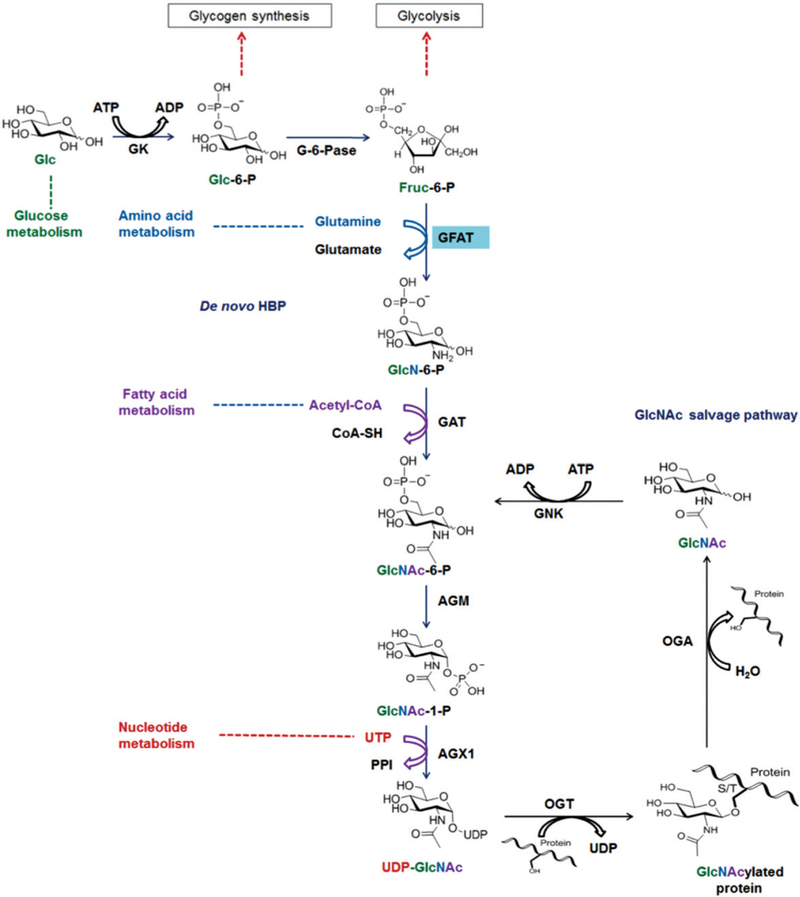

Because the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP) requires rate-limiting metabolites, nearly every metabolic pathway in the cell affects the production of UDP-GlcNAc (Figure 1). This activated sugar nucleotide product of the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP) (Marshall et al., 1991) is used by OGT, thereby poising O-GlcNAc to respond to cellular stimuli including insulin, nutrients and cellular stress (Hanover, 2001; Hart et al., 2007; Love & Hanover, 2005; Wells et al., 2001) and makes OGT an attractive therapeutic target. Indeed, deregulation of O-GlcNAc has been suggested to play a mechanistic role in several diseases processes including diabetes (McClain et al., 2002; Vosseller et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2008), cancers (Caldwell et al., 2010) and neurodegenerative disorders (Lazarus et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2004; Yuzwa et al., 2008) as well as a protective role in acute stress and ischemia/reperfusion injury (Chatham & Marchase, 2010; Laczy et al., 2009). Methods for detecting and modulating O-GlcNAc continue to expand with a focus on optimizing the chemical tools that will further our understanding of the biological roles played by OGT and O-GlcNAc (Çetinbaş et al., 2006; Dorfmueller et al., 2011; Gloster et al., 2011; Gross et al., 2005; Jiang et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2006a,b; Macauley et al., 2005). This review highlights assays and molecules that have been applied to elucidate OGT’s activity at the molecular level, potent OGT inhibitors, high-throughput OGT activity assays and the structural and mechanistic studies of OGT.

Figure 1.

The de novo hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP) and GlcNAc salvage pathway. In most cell types, 2–5% of cellular glucose (Glc) enters the HBP, resulting in the end product, UDP-GlcNAc. UDP-GlcNAc can be used by OGT to catalyze the addition of GlcNAc to nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins, whereas OGA catalyzes the removal of the O-GlcNAc PTM. GFAT is the rate-limiting enzyme for the HBP. GK, glucokinase; G-6-Pase, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase; GFAT, glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase; GAT, acetyl-CoA:D-glucosamine-6-phosphate N-acetyltransferase; GNK, GlcNAc kinase; AGM, phosphor-N-acetylglucosamine mutase; AGX1, UDP-GlcNAc pyrophosphorylase. (see colour version of this figure at www.informahealthcare.com/bmg).

O-GlcNAc transferase

OGT was first characterized from cytosolic fractions of rabbit reticulocytes (Haltiwanger et al., 1990) and was later purified from rat liver cytosol where it was present in two forms: a 110-kDa α-subunit and a 78-kDa β-subunit (Haltiwanger et al., 1992). Subsequently, the OGT genes in rat (Kreppel et al., 1997), Caenorhabditis elegans (Lubas et al., 1997), human (Lubas et al., 1997) and plant (Olszewski et al., 2010; Thornton et al., 1999) were cloned. The human OGT gene is composed of 23 exons and 21 introns and resides on the X chromosome near the Xist locus (Xq13.1), which is a region associated with Parkinson’s disease (Shafi et al., 2000). Knockout studies have shown that mammalian OGT is essential for the viability of embryonic stem cells and embryonic development (Shafi et al., 2000). Interestingly, OGT null C. elegans are viable but exhibit profound metabolic changes, such as insulin resistance and macronutrient storage modifications (Hanover et al., 2005). Although OGT is encoded by a single, highly conserved gene in animals (Kreppel et al., 1997; Lubas & Hanover, 1997), the enzyme has over 1000 protein targets (Hahne et al., 2013; Hart et al., 2007; Love & Hanover, 2005; Wells et al, 2001). The implication of OGT’s regulated modification of its numerous protein substrates will be briefly explored at the conclusion of this article.

OGT isoforms

Three predominant human OGT isoforms are generated by alternative splicing (Figure 2): the longest isoform produces a protein encoded by exons 1–4 spliced directly to exon 6 yielding a ~ 116 kDa protein, which localizes to both the nucleus and cytoplasm (designated ncOGT) (Hanover et al., 2003). ncOGT has 12 tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) motifs and is known to be associated with transcriptional repression (Comer & Hart, 2001), proteasomal inhibition (Zhang et al., 2003, 2007) and stress tolerance (Zachara et al., 2004). One striking feature of human OGT is that the fourth intron can also encode an exon (exon 5), which contains an unique ATG. Use of exons 5–23 encodes the second longest isoform producing a ~ 103 kDa protein. This isoform produces an N-terminal domain that contains a unique mitochondrial targeting sequence, followed by a membrane-spanning α-helix that (termed mOGT) (Love et al., 2003). The mOGT variant has nine TPRs and may be associated with the activation of transcription factor Sp1 by mitochondrial superoxide overproduction (Du et al., 2001). The shortest OGT isoform has a truncated amino terminus encoded by exons 10–23, producing a protein of ~ 75 kDa, and it has been termed sOGT for its short length (Hanover et al., 2003). The sOGT variant contains two TPR motifs, is localized to both the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Lazarus et al., 2006) and is proposed to have an anti-apoptotic function (Fletcher et al., 2002).

Figure 2.

Genomic structure of human OGT splice variants (A). OGT protein domain structure (B) and OGT immunoblot (C). The OGT gene is composed of 23 exons and the three isoforms differ at their amino terminus yielding ncOGT, mOGT and sOGT. Alternative use of intron 4 (exon 5) to produce an altered amino terminus is indicated by the light rectangular box. The exons encoding the nucleocytoplasmic, mitochondrial, and short isoforms are numbered and the different start codons are denoted by the arrows. The potential promoters are indicated as P1 and P2. The predicted downstream promoter (P2) could only produce a transcript encoding the shorter isoforms of OGT. Immunoblot analysis shows the presence of three OGT isoforms in HeLa cells (Hanover et al., 2003). MTS, mitochondrial targeting sequence; CD, catalytic domain; TPR, tetratricopeptide repeat. (see colour version of this figure at www.informahealthcare.com/bmg).

All OGT isoforms consist of two distinct N-terminal and C-terminal domains separated by an intermediate spacer region (Figure 2). The N-terminal domain contains a variable number of TPR motifs. The TPR motif itself consists of 34 amino acids, of which eight residues are highly conserved (Blatch & Lässle, 1999; D’Andrea & Regan, 2003) and is found as a domain in various proteins throughout many organisms (Blatch & Lässle, 1999). TPR motifs are often found in serial arrays and are arranged as two a-helices packed together to form a superhelix with a large groove responsible for binding protein substrates or accessory proteins (Blatch & Lässle, 1999; D’Andrea & Regan, 2003; Kreppel & Hart, 1999; Lubas & Hanover, 2000). The OGT C-terminal catalytic domain (CD) is identical in all three isoforms and has homology to glycogen phosphorylase (Wrabl & Grishin, 2001). The CD consists of three regions: an N-terminal catalytic region (CD-1), C-terminal catalytic region (CD-2) and the intervening region between CD-1 and CD-2. Expression of all three OGT isoforms vary among cell and tissue types suggesting that each may have distinct functions responding to cellular cues (Hanover et al., 2003; Lazarus et al., 2006). In addition, the OGT isoforms have been shown to exhibit in vitro peptide and protein preferences (Lazarus et al., 2006).

With a varying number of TPR motifs, OGT serves as a binding scaffold for numerous partners (Andrali et al., 2005; Cheung et al., 2008; Housley et al., 2009; Iyer & Hart, 2003; Wells et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2002). By the sequential removal of TPR segments, the role of TPR domain length in OGT substrate recognition has been explored. It has been suggested that OGT uses different TPR motifs to recognize specific protein substrates (Kreppel & Hart, 1999; Lubas & Hanover, 2000) and that the TPR domains affect OGT’s catalytic activity (Iyer & Hart, 2003). For example, Iyer et al. demonstrated that removal of the first 2.5 TPR domains of rat OGT impaired its catalytic activity but the construct was still able to effectively bind its interacting partner 0IP106 (OGT-interacting protein, 106 kDa) (Iyer & Hart, 2003). Regulation of OGT activity has been proposed to occur via its interaction with other protein partners such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ-co-activator 1α (PGC1-α) (Housley et al., 2009), myosin phosphatase-targeting subunit 1 (Cheung et al., 2008) and p38 MAP kinase (Cheung & Hart, 2008) as well as the formation of its complex with OGA (Whisenhunt et al., 2006). Recent in vitro data, however, does not clearly support the formation of a functionally significant complex between OGT and OGA affecting OGT activity (David et al., 2012). It has been proposed that OGT activity can be regulated via post-translational modifications including phosphorylation (Song et al., 2008; Whelan et al., 2008), cysteine nitrosylation (Ryu & Do, 2011) and O-GlcNAc modification (Kreppel et al., 1997). Finally, recent kinetic studies showed that both OGT and OGA give different in vitro second-order rate constants toward different protein substrates, and these values can differ in response to the post-translational modification of the target proteins (David et al., 2012).

O-GlcNAc level modulation through small molecule inhibition

Manipulation of intracellular O-GlcNAc levels has been widely used to elucidate the biological functions of the O-GlcNAc modification. Global O-GlcNAc levels can be increased and decreased by both genetic and pharmacological methods, the latter of which is discussed herein. Since an overview of OGA inhibitors and an increase in O-GlcNAc levels has been well described in recent literature (Macauley & Vocadlo, 2010), we discuss several approaches of decreasing O-GlcNAc levels in vitro and in vivo with a special emphasis on small molecule inhibition of OGT.

Decreasing levels of UDP-GlcNAc

Diminishing the upstream UDP-GlcNAc concentration is one method used to globally decrease O-GlcNAc addition to proteins. To decrease flux through the HBP, inhibitors of GFAT (the first and rate-limiting enzyme of the HBP that converts fructose-6-phosphate to glucosamine-6-phosphate) have been used (Gao et al., 2003; Majumdar et al., 2003). Successful GFAT inhibitors are glutamine analogs, 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (1, Figure 3) (Dion et al., 1956) and O-(2-diazoacetyl)-L-serine (azaserine, 2, Figure 3) (Kolm-Litty et al., 1998). Not only do 1 and 2 impact O-GlcNAc levels but they also inhibit amidotransferases in a number of metabolic pathways (Staiano et al., 1980; Wu et al., 1999) suggesting that results obtained using these compounds need to be interpreted with great caution. Indeed, OGT is not the only enzyme that uses UDP-GlcNAc as a substrate: many other N-acetylglucosaminyl transferases use UDP-GlcNAc to construct cell surface glycoconjuates including N-glycans, mucin-type O-linked glycans and glycosphingolipids. Finally, UDP-GlcNAc is a versatile metabolic precursor that is converted into other nucleotide sugar substrates such as cytidine-5′-monophospho-sialic acid (3, Figure 3) and UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc, 4, Figure 3) (Du et al., 2009). Given the central role UDP-GlcNAc plays in various metabolic pathways, the global decrease of UDP-GlcNAc to study O-GlcNAc’s biological role is not an ideal research strategy.

Figure 3.

Structures of the molecules described in the article. (see colour version of this figure at www.informahealthcare.com/bmg).

OGT inhibition by small-molecule inhibitors

Selective inhibition of OGT’s catalytic function is the ideal way to profile the specific roles of the O-GlcNAc modification. Small-molecule inhibitors have proven invaluable for elucidating the biological functions of many classes of enzymes (Knight & Shokat, 2007; Mayer, 2003). Cell permeable small-molecule inhibitors provide several advantages over genetic methods: (1) there is no need for transfection reagents or viral infection and (2) cells can be monitored in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Small molecules are especially useful in cells that are not easily transfected and to monitor whether inhibition yields lasting cellular effects upon inhibitor removal.

An ideal OGT inhibitor has high affinity to OGT, is cell membrane-permeable and exhibits a high specificity to OGT inhibition. The inhibitors described below were discovered by either library screening or rational design. For an in-depth look at several small molecule inhibitors of OGT and OGA, please refer to a recent review and the references therein (Ostrowski & van Aalten, 2013).

UDP

UDP (5, Figure 3) is a by-product of the OGT glycosyl transfer reaction using UDP-GlcNAc and is a potent feedback inhibitor of OGT. A reported half-maximal inhibition (IC50) value of UDP is 1.8 μM for recombinant human ncOGT with the use of a small biotinylated peptide substrate (called biotinylated DEBtide) (Dorfmueller et al., 2011). UDP was reported to have a 50% inhibition value of 0.2 μM when a multimeric OGT enzyme purified from rat liver cytosol and a synthetic peptide (YSDSPSTST) were used (Haltiwanger et al., 1992). UDP occupies a pocket in the carboxy-terminal domain of the catalytic region of OGT and acts as a competitive UDP-GlcNAc inhibitor (Lazarus et al., 2011). Although UDP is a potent inhibitor of OGT, it also inhibits many other glycosyltransferases that utilize UDP-containing sugar nucleotides.

Alloxan

The diabetogenic compound alloxan (6, Figure 3), a uracil analog, is a chemically unstable compound with a half-life of 1.5 min at 37 °C in phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 (Lenzen & Munday, 1991). Nonetheless, alloxan was demonstrated to be an OGT inhibitor (Dorfmueller et al., 2011; Konrad et al., 2002). Konrad et al. measured complete inhibition of OGT activity at 1 mM and IC50 at 0.1 mM alloxan by a traditional radiometric assay using a recombinant protein substrate, nucleoporin 62 (Nup62) and a radioisotope-labeled sugar donor substrate, UDP-[3H]-GlcNAc. Other experiments suggest alloxan exhibits more effective OGT inhibition (IC50 ~ 18 μM) with a small synthetic peptide acceptor substrate (Dorfmueller et al., 2011). The modification of cysteine residues (Konrad et al., 2002) or binding to the uracil binding pocket are two proposed methods of alloxan inhibition (Dorfmueller et al., 2011). Alloxan has been used to investigate OGT’s cellular function and has been shown to decrease O-GlcNAc levels in several studies (Dehennaut et al., 2007; Kang et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2005, 2006, 2007; Noach et al., 2007). For example, in the study of O-GlcNAc’s role in cell cycle regulation (Dehennaut et al., 2007), treatment with alloxan decreased O-GlcNAc levels without a decrease in the cellular UDP-GlcNAc pool and blocked the G2/M transition in an OGT-inhibition dependent manner in Xenopus faevis oocyte. One concern for the use of alloxan is its toxicity through reactive oxygen species generation (Zhang et al., 1992), but the study by Dehennaut et al. (2007) suggests that the mechanism of G2/M transition inhibition is not caused by its toxic effect as two detoxifying enzymes were used in conjunction with the experiments. The lack of target specificity is a second concern for alloxan as it may affect many cellular processes beyond OGT catalysis (Lenzen & Panten, 1988). Indeed, alloxan was also shown to act as a weak OGA inhibitor (5mM alloxan was required for 62% inhibition of recombinant OGA activity), although its inhibition mechanism was not fully established (Lee et al., 2006).

UDP-C-GlcNAc and UDP-S-GlcNAc

Replacing the UDP-GlcNAc glycosidic oxygen with nonhydrolysable isosteric linkages was hypothesized to confer resistance toward enzymatic and chemical hydrolysis. To explore this idea, two OGT inhibitors were synthesized and evaluated: UDP-C-GlcNAc (7, Figure 3) and UDP-S-GlcNAc (8, Figure 3), in which the glycosidic oxygen is replaced by a carbon or sulfur atom, respectively (Dorfmueller et al., 2011; Hajduch et al., 2008). Despite its promise, UDP-C-GlcNAc proved to be a poor inhibitor with an IC50 of more than 5 mM, suggesting that the presence of the glycosidic oxygen in UDP-GlcNAc is important for substrate binding (Hajduch et al., 2008). It is possible that the lack of hydrogen bonds between the isosteric methylene group of the C1-phosphonate analog of UDP-GlcNAc and the active site residues of the enzyme may severely weaken the substrate binding affinity. UDP-S-GlcNAc and UDP-C-GlcNAc were found to occupy different positions in OGT’s active site. Although UDPS-GlcNAc positions the thioglycosidic bond within hydrogen bonding distance of OGT’s active site residues, its inhibitory property was reported to be even worse than UDP-C-GlcNAc (2.3 times) (Dorfmueller et al., 2011). Moreover, UDP-C- and UDP-S-GlcNAc are likely to inhibit other glycosyltransferases that utilize UDP-GlcNAc as a donor and neither analog is readily cell-permeable precluding their use for cellular studies.

UDP-5SGlcNAc

Inhibitors for cell-based studies require minimal polarity and charge to ensure cell permeability. Taking advantage of the promiscuity of cellular enzymes that tolerate unnatural sugar analogs (Agard & Bertozzi, 2009; Jones et al., 2004; Keppler et al., 2001; Vocadlo et al., 2003), Gloster et al. (2011) introduced cell membrane permeable OGT inhibitor precursors. In their strategy, 2-acetamido-1,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-2-deoxy-5-thio-α-D-glucopyranose [(Ac)4-5SGlcNAc] (9, Figure 3) is converted to UDP-5SGlcNAc (10, Figure 3) through the HBP and the GlcNAc salvage pathway in cells (Figure 1). UDP-5SGlcNAc 10 is a chemically modified analog of UDP-GlcNAc, with the endocyclic oxygen atom replaced by sulfur. This molecule was found to be a much poorer donor substrate than natural UDP-GlcNAc (~ 0.03% glycosyl transfer compared with that of the natural sugar donor) (Lazarus et al., 2012) and served as a potent OGT inhibitor both in vitro and in cells (Gloster et al., 2011). Consistent with previous findings (Offen et al., 2006; Tsuruta et al., 1997, 2003), results demonstrated that no measurable amount of 5SGlcNAc-modified proteins were detected in cell-based assays. In addition, Gloster et al. (2011) defined that this is not due to the faster hydrolysis of 5SGlcNAc-modified proteins by OGA but due to the much less efficient transfer of 5SGlcNAc by OGT (UDP-5SGlcNAc was measured to be approximately three times worse substrate for OGT compared to the corresponding sugar substrate for OGA). Structural and modeling studies have shown that the sulfur substitution in the ring does not cause alteration of the sugar conformation (Lazarus et al., 2012). The proposed dissociative SN2 mechanism of OGT involves the development and movement of an oxocarbenium ion-like species away from the leaving group toward the acceptor (Lazarus et al., 2012). The substitution of the endocyclic oxygen with sulfur is thought to reduce the stabilizing effect on the anomeric carbon making it resist the formation and movement of an electrophilic anomeric center relative to its oxygen counterpart.

Like several OGT inhibitors described above, UDP-5SGlcNAc is speculated to inhibit other glycosyltransferases that use UDP-GlcNAc as the donor substrate. Interestingly, no effect on cell surface glycosylation is detected by the treatment of cells with (Ac)4-5SGlcNAc (Gloster et al., 2011). However, testing did not indicate whether UDP-5SGlcNAc inhibits only OGT. There are numerous possible explanations for the absence of cell surface glycosylation changes, including: (1) the O-GlcNAc modification turns over at a faster rate than cell surface glycans and is, therefore, more quickly affected in the time frames tested and (2) 5SGlcNAc is not sufficiently distributed in the secretory pathway due to differences in transport rates. The second interesting, but surprising feature of 5SGlcNAc, is that it has no apparent toxicity in mammalian cells yielding no changes in cell morphology or cellular growth rate, despite the fact that its treatment dramatically decreases cellular O-GlcNAc levels (Gloster et al., 2011). This result contrasts genetic studies that show that selective OGT knockout, and consequent loss of O-GlcNAc leads to neuronal apoptosis (O’Donnell et al., 2004) and loss of embryonic stem cell viability (Shafi et al., 2000). These conflicting results imply that diminishing O-GlcNAc levels may not be the direct cause for these crippled cellular functions. Continued efforts toward the development of cell permeable and highly specific OGT inhibitors are essential to clarify the precise basis for the differences observed between the genetic and chemical tools.

Bisubstrate UDP-peptide conjugates

In order to improve the specificity of target enzyme inhibition, molecules that combine elements of both donor and acceptor substrates have been constructed and evaluated as selective inhibitors (Izumi et al., 2009; Lavogina et al., 2010; Palcic et al., 1989). In line with this concept, bisubstrate UDP-peptide conjugates (11 and 12, Figure 3) were synthesized and evaluated as OGT inhibitors. These compounds feature a short linker that replaces the GlcNAc moiety of the donor substrate, covalently connect the UDP to the serine of an acceptor peptide (VTPVSTA), and were found to be in vitro OGT inhibitors with IC50 values in the micromolar range (Borodkin et al., 2013). Although selectivity was not thoroughly examined, they have some OGT specificity in that bisubstrate UDP-peptide 11 inhibits OGT (IC50 of 18 μM when a synthetic peptide was used) but not the N-acetylglucosamine transferase SmNodC (Borodkin et al., 2013). However, these bisubstrate UDP-peptide conjugates failed to inhibit OGT in cells, most likely due to the lack of cell permeability (Borodkin et al., 2013).

Neutral diphosphate mimics: dicarbamate core-containing compounds

In 2005, the Walker laboratory elected to utilize a high-throughput library screening strategy and identified several in vitro micromolar inhibitors of human OGT (13–15) (~ 10–100 μM) (Gross et al., 2005), some of which were later shown to have utility in cells (Caldwell et al., 2010; Hart et al., 2011; Ngoh et al., 2008). Of the compounds identified, one containing a benzo[d]oxazol-2-one moiety and a phenyl carbamate moiety featuring dicarbamate (15, Figure 3) was further studied (Jiang et al., 2012). To deduce the mechanism of OGT inhibition, several dicarba-mate derivatives were synthesized (Jiang et al., 2012), and the Walker laboratory identified that in the OGT active site, the dicarbamate moiety resides in the same location as UDPGlcNAc’s diphosphate group. Specifically, lysine 842 (K842) points to the dicarbamate carbonyls and OGT inhibition has been proposed to occur via a double displacement mechanism (Figure 4). K842 in the enzyme’s active site is thought to act as the primary nucleophile attacking the acyclic dicarbamate carbonyl thus forming a covalent bond. Subsequently, a nearby second nucleophile cysteine 917 (C917) attacks the K842 dicarbamate carbonyl adduct to form a C=O crosslink between two active site nucleophiles, resulting in an irreversible loss of enzyme activity. It is interesting to note that the compound 16 (Figure 3) with an electron-donating substituent at the phenyl carbamate moiety gave the most potent inhibition among several derivatives with different substituents on the dicarbamate scaffold tested. This may be explained by the electron-donating substitution of the phenyl carbamate, which decreases the reactivity of the acyclic carbonyl carbon of the dicarbamate toward the nucleophilic substitution by an enzyme’s nucleophile. The decreased reactivity of the acyclic carbonyl carbon, in turn, improves its selectivity for the attacking nucleophile of the enzyme.

Figure 4.

Proposed double displacement mechanism for the inhibition of OGT by the dicarbamate core-containing compounds (compound 16 pictured here) (Jiang et al., 2012). One dicarbamate acyclic carbonyl reacts with an active site lysine (K842) and the lysine adduct reacts again with a nearby cysteine (C917) to crosslink the OGT active site yielding irreversible loss of enzymatic activity. (see colour version of this figure at www.informahealthcare.com/bmg).

Even at a few hundred micromolar concentration, the molecules functioning as the neutral diphosphate mimics yielded a significant decrease in the cellular O-GlcNAc levels (Dehennaut et al., 2007; Jiang et al., 2012). For example, the benzoxazolinone derivative (15, 500 μM) used in the study of the relationship between O-GlcNAc and the cell cycle has been shown to inhibit the increase of progesterone-induced O-GlcNAc levels and block G2/M transition in Xenopus immature oocyte via the inhibition of OGT (Dehennaut et al., 2007). However, related dicarbamate scaffolds may inhibit other enzymes that bind diphosphate-containing substrates.

OGT activity assay methods

Availability of a useful enzymatic assay to measure OGT activity is a prerequisite for developing potent and selective OGT inhibitors. Indeed, aided by several useful, high-throughput, enzymatic assays and mechanistic and structural insights for OGA, the design of potent and OGA selective inhibitors has flourished in recent years (for reviews, see Gloster & Vocadlo, 2010; Kim, 2011; Macauley & Vocadlo, 2010 and references therein). The use of small-molecule OGA inhibitors has greatly improved our understanding of O- GlcNAc’s physiological roles. In contrast, efficient discovery of potent OGT inhibitors has been impeded by the lack of a rapid and easy method to continuously monitor OGT activity. OGT enzymatic assay methods adaptable to high-throughput detection technologies have been introduced and are discussed below along with the conventional OGT activity assay.

Direct measurement of OGT enzymatic activity

Conventional in vitro OGT activity assay

The conventional in vitro OGT activity assay uses a radiolabeled sugar donor substrate such as UDP-[14C]-GlcNAc or UDP-[3H]-GlcNAc and a sugar acceptor protein substrate such as unmodified Nup62 (Lubas & Hanover, 2000). OGT activity is quantified by measuring radiolabeled GlcNAc incorporation into the protein substrate during the enzymatic reaction. Two detection methods, autoradiography and liquid scintillation counting, are predominately used for assaying incorporated radioactivity. Although the radiometric method is extremely useful in life science studies, it involves a tedious procedure, high cost and inevitable radiochemical waste, which render it unsuitable for rapid high-throughput analysis.

Azido-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Leavy & Bertozzi (2007) introduced the high-throughput azido-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Figure 5), in order to interrogate OGT’s r (avidin and biotin) and an azide-selective chemical reaction (Staudinger ligation). First, a solution-phase enzymatic reaction is performed using unnatural substrates, UDP-N-azidoacetyl glucosamine (UDP-GlcNAz) and biotinylated peptide in the presence of OGT. The resulting reaction mixture is then transferred onto avidin-coated microplates to capture the GlcNAz-labeled biotinylated peptide substrates. Subsequently, a chemoselective reaction between the GlcNAz-labeled peptides immobilized on the microplates, and a phosphine-FLAG probe is performed. The resulting FLAG-labeled epitopes bound to the microplate are used for a colorimetric readout of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) activity by using a HRP-conjugated anti-FLAG antibody yielding the relative OGT activity toward each peptide substrate. Transferring the solution-phase enzymatic reaction onto a microplate reduces this method’s efficiency and may increase the risk of introducing experimental error. In addition, the method requires the synthesis of the phosphine-FLAG probe as it is not commercially available at the time of this writing. We have recently developed a versatile 96-well plate-based assay where purification of OGT is not required (Kim et al., 2014). This assay is expected to be useful for the identification of new inhibitors, substrates and OGT enzyme variants and all reagents are readily available.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the azido-ELISA method for measuring OGT activity. (see colour version of this figure at www.informahealthcare.com/bmg).

Indirect measurement of OGT enzymatic activity

Protease protection assay

In order to monitor glycosyltransferase activity, the Walker laboratory. reported a strategy that measures OGT activity indirectly through protease activity (Figure 6A) (Gross et al., 2008). The “protease protection assay” exploits the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) phenomenon (Figure 6B) with a FRET pair tethered at each end of a substrate. In FRET, a fluorescent donor absorbs light at a defined wavelength and is excited to the singlet state. Upon relaxation to the lowest excited singlet state, S1, some of the absorbed energy dissipates. If no acceptor fluorophore is in proximity to the donor, the relaxed singlet state of the donor returns to its ground energy state (So) by emitting the remaining light energy at a longer wavelength in the form of specific fluorescence. However, if an acceptor fluorophore is near the donor, the energy released from the donor can be transferred and excite the acceptor fluorophore in a nonradiative process termed “resonance”. The excited acceptor then emits energy at a new wavelength and returns to the ground state. For resonance energy transfer to occur, a FRET pair must simultaneously satisfy compatibility and proximity. In recent years, quencher molecules that transform the light energy to heat and remain “dark” have emerged to replace fluorescent acceptor molecules. Fluorophore-quencher dual-labeled constructs have no measurable fluorescence as long as the construct remains intact, thus simplifying many fluorescence-based assays (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The “protease-protection OGT assay” (A) and a representation of the “FRET” phenomenon (B). (see colour version of this figure at www.informahealthcare.com/bmg).

Walker et al. employed substrates containing a fluorescein donor at one terminus and a quencher or fluorescent acceptor molecule at the other terminus (Gross et al., 2008). Their strategy exploits the fact that proteases preferentially cleave less sterically hindered unglycosylated peptides over glycosylated peptides. In this method, FRET-pair labeled peptides are O-GlcNAcylated by OGT and then treated with a protease. The degree of peptide O-GlcNAcylation is assumed to be inversely related to the amount of proteolysis and is determined by measuring the resulting FRET signal after proteolysis. The indirect nature of the assay presents a potential concern since inhibitors or activators of the protease activity can make negative compounds as appear as positive hits.

Measurement of ligands’ binding affinity for OGT: a fluorescent-based substrate displacement method

A “fluorescent-based substrate displacement” method (Figure 7) was exploited by the Walker group to rapidly screening small-molecule OGT inhibitors (Gross et al., 2005). This strategy involves monitoring the fluorescence polarization of a fluorescent substrate. Fluorescence polarization depends on the mobility of a fluorescent molecule and provides a non-disruptive means of measuring the association of a fluorescent substrate with a larger molecule such as a protein: if the small fluorescent molecule is freely moving, it will emit the light in a different direction from the incident light and tend to “scramble” the polarization of the light. This “scrambling” effect results in a low level of polarization. Conversely, large molecules such as proteins in solution move relatively slowly and will emit polarized light when excited with polarized light. In the fluorescent-based substrate displacement OGT assay, a small unbound fluorescent UDPGlcNAc analog (17, Figure 3) rotates rapidly and maintains low levels of polarization after excitation. However, if the fluorescent molecule binds OGT, forming a larger and more stable complex, the bound fluorescent probe rotates more slowly reducing the “scrambling” effect and increasing the amount of polarized light. Therefore, the amount of polarization observed is proportional to the amount of OGT complex formed, which is itself proportional to the concentration of its binding to the OGT partner.

Figure 7.

A “fluorescent-based substrate displacement” method for high-throughput screening of OGT inhibitors. (see colour version of this figure at www.informahealthcare.com/bmg).

All the assays described above require that the OGT enzyme be added in a highly purified form. OGT activity is sensitive to temperature and loss of the enzyme’s activity can occur during the enzyme’s purification. In fact, OGT’s catalytic activity requires proper storage and preparation conditions and the enzyme’s activity is affected by repeated freeze/thaw cycles. Therefore, preparation and purification of catalytically active OGT is not trivial and careful attention needs to be paid to the protocol used (Kim & Hanover, 2013). For a more rapid, facile analysis of OGT activity and screening of OGT inhibitors, a high-throughput assay that does not require the OGT enzyme purification is desired.

Structural and mechanistic studies of OGT

The CDs of OGT have Rossmann-like folds typical of a glycosyltransferase 41 (GT41), type B (GT-B) family in the Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (Cantarel et al., 2009). In detail, OGT catalyzes glycosyl transfer from the a-linked sugar on UDP-GlcNAc inverting the stereochemistry to form the β-O-GlcNAc linked protein modification. OGT is exquisitely sensitive to pH with an optimum catalytic activity at pH 6, and its activity is dramatically decreased at a pH lower than 6 or higher than 7 (Haltiwanger et al., 1992). Unlike many other glycosyltransferases, OGT does not require the presence of a divalent metal ion for efficient catalysis (Haltiwanger et al., 1990, 1992). One notable feature of OGT is the intervening domain between the catalytic lobes: together with an adjacent helix of the CD-2 domain, a basic patch is formed and was previously proposed to function as a PIP3-specific binding region (Yang et al., 2008). Recent mutagenesis studies were not consistent with this proposal, necessitating further investigation to elucidate the exact roles of the intervening domain (Lazarus et al., 2011).

Structural insights into the TPR domain of OGT

The first structural insights into OGT architecture were provided by the crystal structure of the TPR domain of human ncOGT (Jinek et al., 2004). The crystallized protein lacking the C-terminal domain exists as a homo-dimer [which differs from the trimeric state previously proposed for ncOGT (Kreppel & Hart, 1999)] with each monomer consisting of 23 anti-parallel α-helices that form a right-handed superhelix. This TPR structure showed an extended superhelical architecture with a groove along the lengthwise axis, the center part of which is lined with asparagine residues (Jinek et al., 2004). This asparagine “ladder” in OGT resembles the armadillo repeats found in the structures of importin α (Conti & Kuriyan, 2000; Conti et al., 1998) and β-catenin (Huber & Weis, 2001); in these proteins, the asparagine ladder is important for recognition of their target peptides. The considerable length of the TPR motifs in OGT is suggested to provide a scaffold to accommodate many protein partners in different orientations and binding modes, thereby explaining the absence of an explicit primary sequence motif for the O-GlcNAc modification.

Although there is no obvious consensus sequence that directs for the addition of O-GlcNAc, recent advances in chemical and biological methodologies in conjunction with the development of various mass spectrometry technologies have led to the detailing of the O-GlcNAc proteome. In addition, O-GlcNAc proteomic databases and bioinformatics software tools are available for the in siiico prediction of potential O-GlcNAc modification sites: namely, YinOYang (Blom et al., 2004) (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/YinOYang), OGlcNAcScan (Wang et al., 2011) (http://cbsb.lombardi.georgetown.edu/hulab/OGAP.html) and O-GlcNAcPRED (Jia et al., 2013) (website for this tool is not available as of publication). Along with computational analysis (Frequency amino acids analysis with online Protein Sequence Logos), Liu et al. (2014) examined key amino acid positions and identities affecting O-GlcNAcylation of peptides experimentally. The authors found that the computational amino acid site analysis was not always consistent with the experimental data suggesting that for improved prediction accuracy, the tools need to be further developed.

Structural insights into the CD of OGT

Structural insights into the C-terminal domain of OGT were first obtained from the structure of a GT41 bacterial homolog of OGT from the plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestis (XcGT41) by two independent groups (Clarke et al., 2008; Martinez-Fleites et al., 2008). The XcGT41 structures revealed that the C-terminal CD displays glycosyltransferase GT-B topology and UDP-GlcNAc binding between the two (α/β)-fold domains (Clarke et al., 2008; Martinez-Fleites et al., 2008). Although the bacterial enzyme lacks anintervening region between the two (α/β)-fold domains of the GT-B fold, which appears in all mammalian sequences, these structures enabled the identification of the OGT active site. In addition, this research elucidated how the superhelical grove of the TPR domain extends directly into the CD and active site (Clarke et al., 2008; Martinez-Fleites et al., 2008). The long awaited three-dimensional structure of human OGT, featuring 4.5 TPRs and the CDs was solved by the Walker group in 2011 (Lazarus et al., 2011). The ternary structure of the OGT-UDP-peptide complex revealed that UDP binds in a pocket in the CD-2 domain near the interface with the CD-1 domain. Moreover, the peptide substrate binds in the cleft between the TPR and the catalytic region and extends along the interface between the CD-1 and CD-2 domains, lying over the UDP-GlcNAc binding pocket. The information derived from the human OGT’s crystal structure provided numerous clues for deducing an OGT catalytic mechanism although the identification of the catalytic residues and reaction mechanism remains to be defined.

Proposed OGT catalytic mechanisms

A sequentiai “bi-bi” mechanism

OGT was initially thought to function through a random sequential “bi-bi (two on; two off)” mechanism in which either substrate can bind first (Kreppel & Hart, 1999). However, the crystal structure of human OGT in complex with UDP and peptide revealed that the peptide-binding region lies above the UDP-GlcNAc-binding pocket, thus blocking access to it. This finding supports an ordered, sequential bi-bi mechanism in which UDP-GlcNAc binds first, and then the peptide acceptor binds over the nucleotide sugar (Figure 8) (Lazarus et al., 2011). The structure also revealed that the TPR domain is separated from the CD by a flexible “hinge” region and the conformational motion that occurs around the “hinge” would either allow or restrict protein substrates to enter the active site.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of an ordered “bi-bi” kinetic mechanism of OGT and two proposed mechanisms for O-GlcNAc transfer. (A) A mechanism proposed by Schimpl et al. in which the α-phosphate oxygen serves as the base catalyst (Schimpl et al., 2012). (B) A mechanism suggested by Lazarus et al. in which the proton of the acceptor hydroxyl is relayed out of the active site through a chain of intervening water molecules to an acceptor (Asp554) in a “Grotthuss-type” mechanism (Lazarus et al., 2012). (see colour version of this figure at www.informahealthcare.com/bmg).

The elusive OGT catalytic base

A big advance in understanding the OGT mechanism through a catalytic base was made in 2012 when UDP-5SGlcNAc was used in complex with human OGT (Lazarus et al., 2012; Schimpl et al., 2012). The enzyme’s catalytic base is thought to increase the reactivity of an acceptor protein toward its nucleophilic attack on the anomeric carbon of UDP-GlcNAc by abstracting a proton from a serine or threonine hydroxyl of the acceptor substrate. Histidine residues [human His498 (Lazarus et al., 2011) and human His558 deducted from the His218 in a bacterial OGT structure from the plant pathogen X. campestis (Martinez-Fleites et al., 2008)] and Tyr841 (Dorfmueller et al., 2011) were previously proposed as potential bases for OGT’s catalysis. However, two recent papers describing crystal structures of the ternary complexes of OGT with UDP-GlcNAc and peptide acceptor analogs rejected the idea of direct interaction of the acceptor with any of those proposed residues as they were too far from the acceptor hydroxyl (Lazarus et al., 2012; Schimpl et al., 2012). In the two independent studies, both groups employed strategies to capture a ternary complex of OGT:UDP-sugar:peptide acceptor since glycosyl transfer tends to occur during the time scale of crystallization when the natural donor substrate (UDP-GlcNAc) is used. In order to reduce the rate of enzymatic turnover or avoid hydrolysis of the donor substrate, the groups used UDP-5SGlcNAc (10, Figure 3), an inhibitor of OGT (Gloster et al., 2011) and serine-substituted peptide acceptor analogs.

Lazarus et al. chose to use an incompetent peptide acceptor, the CKII peptide analog (CKIIA) wherein the GlcNAc-modification site is removed by the mutation of a serine to alanine and observed that no glycosyl transfer occurred during crystallization when used in conjunction with UDP-5SGlcNAc (Lazarus et al., 2012). In their work, Schimpl et al. (2012) used a derivative of the TAB1 acceptor substrate in which the serine hydroxyl was replaced with aminoalanine residue (aaTAB1) and found that glycosyl transfer onto the aminoalanine of the aaTAB1 peptide was very slow when used with UDP-5SGlcNAc. These non-natural substrates were shown to adopt the same binding position and conformation as their natural substrates, providing meaningful insight into the reaction coordinate and catalytic mechanism of OGT. It is interesting to note that the UDP-sugar donor interacts extensively with the enzyme’s active site residues and with the peptide acceptor. This observation is consistent with the recently reported kinetic data; apparent Km values for UDP-GlcNAc vary with regard to the different protein acceptors (David et al., 2012). Overlay of the ternary substrate complex (OGT:UDP-5SGlcNAc:CKIIA) and the ternary product complex (OGT:UDP:GlcNAcylated CKII) revealed that the UDP moiety and the peptide acceptor remain immobile, whereas C5-O5-C1-C2 atoms of the β-linked GlcNAc moiety in the 4C1 chair conformation vary in position, such that the anomeric carbon (C1), is tilted away from the pyrophosphate group and points toward the nucleophilic serine hydroxyl along the reaction coordinate (Lazarus et al., 2012). The structure of another ternary product complex (OGT:UDP:GlcNAcylated TAB1) solved by Schimpl et al. (2012) showed that the N-acetyl moiety lies in a relatively spacious pocket between the catalytic core and the TPR repeats, explaining why OGT can tolerate a diverse array of UDP-GlcNAc analogs bearing bulky amido substituents (Gross et al., 2005; Vocadlo et al., 2003). The Walker and van Aalten groups each suggest different residues acting as the catalytic base (Figure 8A and 8B), and their findings are highlighted in a short report from 2012 (Withers & Davies, 2012). General features and implications of the proposed mechanisms are discussed below.

Substrate-assisted catalysis: α-phosphate on the UDP-GlcNAc as a general base.

Schimpl et al. (2012). proposed a “substrate-assisted catalysis” where the catalytic base is not provided by the enzyme, but by the α-phosphate on the donor substrate itself. They observed the functional difference between the two chiral α-phosphorothioate derivatives of UDP-GlcNAc in OGT-catalyzed O-GlcNAc transfer when aaTAB1 was used as an acceptor (Schimpl et al., 2012): for the one α-phosphorothioate diastereomer, sulfur replaces the α-phosphate oxygen pointing toward the acceptor serine (pro-R position, 18, Figure 3) and is catalytically inactive. The other diastereomer (pro-S position, 19, Figure 3) is a functional donor in an O-GlcNAc transfer reaction, although both diastereomers bind to OGT with a similar affinity as UDP-GlcNAc. In the proposal by Schimpl et al., the pro-R oxygen of the α-phosphate acts as a base and deprotonates the acceptor, which proceeds as a nucleophilic attack onto the anomeric carbon, with in-line displacement of the UDP leaving group, resulting in inversion of stereochemistry (Figure 8A). It is widely assumed that the less basic candidate oxygen of α-phosphate in UDP-GlcNAc (pKa ~2 in solution for the conjugate acid of this phosphate while the pKa ~16 for the conjugate acid of the serine hydroxyl) yields the α-phosphate as a less likely proton acceptor. However, unexpected UDP-GlcNAc 31P-NMR titration data suggested that the pKa could be much higher than the anticipated value (Jancan & Macnaughtan, 2012).

“Grotthuss-type” mechanism: Asp554 acts as a base through a water chain.

In contrast to the proposal for the role of the α-phosphate as a candidate base in the OGT catalysis suggested by Schimpl et al., Lazarus et al. (2012) de-emphasized the role of the α-phosphate as the catalytic base. They noted that the oxygen on the α-phosphate in their structure was hydrogen bonded to the amide backbone of the peptide, which is thought to greatly attenuate its basicity. In addition, the modeled serine rotamer, that is properly positioned to interact with the a-phosphate, was argued to be incorrectly aligned for its attack onto the anomeric carbon. Thus, they proposed a “dissociative SN2 mechanism” involving electrophilic migration of the anomeric center in which a highly dissociative oxocarbenium ion-like species moves away from the leaving group toward the acceptor. In this mechanism, the acceptor serine proton may be shuttled out of the site through a chain of intervening water molecules in a “Grotthuss-type” mechanism, possibly to the carboxylate side chain of the conserved residue Asp554 (Figure 8B). However, mutation of Asp554 (D554N) did not inactivate the enzyme (Schimpl et al., 2012), calling into question the possible role of Asp554 in catalysis as a base.

Quantum mechanical considerations: is a catalytic base necessary?

A third independent group performed calculations using quantum mechanical and molecular modeling methods (Tvaroška et al., 2012) that supports the “dissociative SN2 mechanism” for OGT catalysis, in which the structure of transition state has a significant oxocarbenium ion-like character. However, once again the choice of a base catalyst is problematic. In their model, His498 was assigned as a base catalyst, an assignment rendered highly unlikely by the recent structural and mutational studies (Lazarus et al., 2012; Schimpl et al., 2012). Alternatively, like some inverting glycosidases that seem to lack a base catalyst, a general base catalysis may not be essential for OGT (Koivula et al., 2002). The high affinity binding of UDP-GlcNAc to a deep pocket within the OGT CD is somewhat unique and may serve to increase the reactivity of the nucleotide sugar, thus lowering the energetic barrier presented by the glycosyl transfer step. At this point, the nature of the general base and the identity of the base residue for OGT catalysis are unclear and further studies are, thus, required to answer which, if any, features function in the capacity of a general base.

A role for the GlcNAc acetamido group in the OGT catalysis

A role for the GlcNAc acetamido group of the donor substrate in OGT catalysis has been proposed (Koivula et al., 2002; Lazarus et al., 2012; Schimpl et al., 2012). Both Lazarus et al. (2012) and Tvaroška et al. (2012) suggested a role for the N-acetyl NH moiety (HNAc) in stabilizing the UDP leaving group at the transition state. Lazarus et al. (2012) observed a substantial rotation of the acetamido group of the donor substrate upon its conversion to product and ascribed the stabilizing effect exerted by the HNAc moiety to its hydrogen bonding to the β-phosphate oxygen of UDP. In contrast, Tvaroška et al. (2012) ascribed it to its hydrogen bonding to the glycosidic oxygen, but the general base they assigned in their model is unlikely based on known structural information. A product complex obtained by Schimpl et al. (2012) also showed that the HNAc moiety coordinates with the β-phosphate oxygen of UDP. Since all three groups demonstrated the importance of the acetamido group of the donor substrate, catalytic activity of OGT is likely to be dependent on the presence of this moiety; OGT is catalytically active with UDP-GalNAc (4, Figure 3), but not with UDP-glucose (UDP-Glc 20, Figure 3) or UDP-2-ketoGlucose (UDP-2-ketoGlc 21, Figure 3) (Lazarus et al., 2012). The involvement of the GlcNAc acetamido group and possibly the α-phosphate moiety of the nucleotide sugar in the enzymatic reaction is intriguing in light of the proposed role of OGT as a sensor of nutrient-derived UDP-GlcNAc. Although, several catalytic mechanisms of OGT have been proposed to date, none are completely consistent with available data necessitating further research.

Conclusions and perspectives

Cellular processes such as cell cycle regulation, stress response and gene expression are regulated, in part, by the O-GlcNAc modification. Many post-translational modifications work together with O-GlcNAc in a delicate balance to appropriately maintain cellular homeostasis. With improper regulation of OGT and OGA, cellular processes can go awry yielding pathologies including cancers, diabetes II and neurodegeneration. A number of recent publications also demonstrate that modulation of OGT and O-GlcNAc may impart a cytoprotective effect in acute injury responses (Champattanachai et al., 2008; Laczy et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2007; Ngoh et al., 2010; Xing et al., 2008).

Highly active research efforts including the development of high-throughput OGT assay methods and the solution of the structure of OGT comprising both catalytic and TPR domains have yielded a better understanding of the catalytic mechanism in order to generate potent inhibitors. Continued efforts toward developing simpler OGT assay methods in which the enzyme needs not be purified, and the generation of OGT-specific and isoform-specific OGT inhibitors are on the horizon and promise to spur forward our understanding of the O-GlcNAc post-translational modification.

There are still challenging questions remaining: (1) how are OGT and OGA regulated in order to modulate O-GlcNAc levels? and (2) how does one single enzyme target so many substrates while retaining substrate specificity? The activities of OGT and OGA are likely regulated by their own post-translational modifications. The existence of multiple isoforms of the OGT and OGA arising from alternative splicing (Hanover et al., 2003; Nolte & Müller, 2002; Shafi et al., 2000) may partly explain how these enzymes can have a variety of substrates. Techniques to manipulate both OGT and O-GlcNAc levels will provide additional tools to answer these questions. Moreover, the study of gain/loss of function of OGT in either mammalian tissue culture cells or model organisms may prove equally useful.

Several proteins such as myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 1 (Cheung et al., 2008), trafficking kinesin-binding protein 1 (formerly known as OGT-interacting protein 106) (Beck et al., 2002; Iyer & Hart, 2003; Iyer et al., 2003;), p38 MAPK (Cheung et al., 2008) and PGC 1α (Housley et al., 2009) have been revealed to interact with and target OGT to unique substrates during a signaling event. Studies on such proteins and their roles demonstrate that the substrate specificities of OGT can be determined, in part, by its transient interactions with many binding partners to form various substrate specific holoenzymes. Many of these proteins are known to be modified by O-GlcNAc, which might also affect their interaction and targeting (Iyer & Hart, 2003). Discoveries of such proteins and elucidation of their roles and the nature of their interactions are also good avenues for researchers to explore.

Despite absence of a eukaryotic OGA crystal structure, the domain responsible for OGA’s glycoside hydrolase activity, and its detailed catalytic mechanism including general acid catalytic residues are well established (Çetinbaş et al., 2006; He et al., 2010). Although OGA is presumed to be targeted to O-GlcNAc-modified proteins by interacting proteins, this has yet to be fully addressed. Interestingly, the C-terminal domain of OGA which is absent in the bacterial sequences, has a putative GCN-5-related histone acetyltransferase-like domain; however, whether this domain actually has the ability to acetylate histones remains controversial (Butkinaree et al., 2008; Toleman et al., 2004). Most recently, Rao et al. demonstrated that the C-terminal domain of human OGA does not possess the key residues required for acetyltransferase activity and is a catalytically incompetent “pseudo”-acetyltransferase based on their crystal structure of a marine bacterial homolog of the human OGA C-terminal acetyltransferase domain (Rao et al., 2013). Ultimately the crystal structure of the human OGA will help to address this question.

Determining the functional roles of the various OGT and OGA isoforms will be an important area for future research. Recently, dynamic O-GlcNAcylation during signaling has been demonstrated using an O-GlcNAc sensor (Carrillo et al., 2011) and a surprising study that OGT possesses proteolytic activity against HCF1 has also been reported (Capotosti et al., 2011). Continued development of technologies and tools will deepen our understanding of the roles of OGT, OGA and O-GlcNAc play in basic biology and, ultimately, human health.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge helpful comments from the Hanover and Krause laboratories and support from the Intramural NIDDK program including the NIDDK Chemical Biology Core.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

This work was supported by NIDDK intramural funds (NIH) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (2011 – 0027257).

References

- Agard NJ, Bertozzi CR. (2009). Chemical approaches to perturb, profile, and perceive glycans. Acc Chem Res 42:788–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrali SS, März P, Ozcan S. (2005). Ataxin-10 interacts with O-GlcNAc transferase OGT in pancreatic β cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 337:149–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M, Brickley K, Wilkinson HL, et al. (2002). Identification, molecular cloning, and characterization of a novel GABAA receptor-associated protein, GRIF-1. J Biol Chem 277:30079–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatch GL, Lässle M. (1999). The tetratricopeptide repeat: a structural motif mediating protein-protein interactions. BioEssays 21:932–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom N, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Gupta R, et al. (2004). Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics 4:1633–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodkin VS, Schimpl M, Gundogdu M, et al. (2013). Bisubstrate UDP-peptide conjugates as human O-GlcNAc transferase inhibitors. Biochem J 457:497–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butkinaree C, Cheung WD, Park S, et al. (2008). Characterization of β-N-acetylglucosaminidase cleavage by caspase-3 during cpoptosis. J Biol Chem 283:23557–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell SA, Jackson SR, Shahriari KS, et al. (2010). Nutrient sensor O-GlcNAc transferase regulates breast cancer tumorigenesis through targeting of the oncogenic transcription factor FoxM1. Oncogene 29: 2831–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, et al. (2009). The carbohydrate-active enZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D233–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capotosti F, Guernier S, Lammers F, et al. (2011). O-GlcNAc Transferase catalyzes site-specific proteolysis of HCF-1. Cell 144: 376–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo LD, Froemming JA, Mahal LK. (2011). Targeted in vivo O-GlcNAc sensors reveal discrete compartment-specific dynamics during signal transduction. J Biol Chem 286:6650–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çetinbaş N, Macauley MS, Stubbs KA, et al. (2006). Identification of Asp174 and Asp175 as the key catalytic residues of human OGlcNAcase by functional analysis of site-directed mutants. Biochemistry 45:3835–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champattanachai V, Marchase RB, Chatham JC. (2008). Glucosamine protects neonatal cardiomyocytes from ischemia-reperfusion injury via increased protein O-GlcNAc and increased mitochondrial Bcl-2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294:C1509–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatham JC, Marchase RB. (2010). Protein O-GlcNAcylation: a critical regulator of the cellular response to stress. Curr Signal Transduct Ther 5:49–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung WD, Hart GW. (2008). AMP-activated protein kinase and p38 MAPK activate O-GlcNAcylation of neuronal proteins during glucose deprivation. J Biol Chem 283:13009–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung WD, Sakabe K, Housley MP, et al. (2008). O-Linked β-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase substrate specificity is regulated by myosin phosphatase targeting and other interacting proteins. J Biol Chem 283:33935–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AJ, Hurtado-Guerrero R, Pathak S, et al. (2008). Structural insights into mechanism and specificity of O-GlcNAc transferase. EMBO J 27:2780–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer FI, Hart GW. (2001). Reciprocity between O-GlcNAc and O-phosphate on the carboxyl terminal domain of RNA Polymerase II. Biochemistry 40:7845–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti E, Kuriyan J. (2000). Crystallographic analysis of the specific yet versatile recognition of distinct nuclear localization signals by karyopherin α. Structure 8:329–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti E, Uy M, Leighton L, et al. (1998). Crystallographic analysis of the recognition of a nuclear localization signal by the nuclear import factor karyopherin α. Cell 94:193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea lD, Regan L. (2003). TPR proteins: the versatile helix. Trends Biochem Sci 28:655–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David LS, Tracey MG, Scott AY, David JV. (2012). Insights into O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) processing and dynamics through kinetic analysis of O-GlcNAc transferase and O-GlcNAcase activity on protein substrates. J Biol Chem 287:15395–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehennaut V, Lefebvre T, Sellier C, et al. (2007). O-Linked N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase inhibition prevents G2/M Transition in Xenopus iaevis oocytes. J Biol Chem 282:12527–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion HW, Fusari SA, Jakubowski ZL, et al. (1956). 6-Diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine, a new tumor-inhibitory substance. II. Isolation and characterization. J Am Chem Soc 78:3075–7. [Google Scholar]

- Dorfmueller HC, Borodkin VS, Blair DE, et al. (2011). Substrate and product analogues as human O-GlcNAc transferase inhibitors. Amino Acids 40:781–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Meledeo MA, Wang Z, et al. (2009). Metabolic glycoengineering: sialic acid and beyond. Glycobiology 19:1382–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du XL, Edelstein D, Dimmeler S, et al. (2001). Hyperglycemia inhibits endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity by posttranslational modification at the Akt site. J Clin Invest 108:1341–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher BS, Draqstedt C, Notterpek L, Nolan GP. (2002). Functional cloning of SPIN-2, a nuclear anti-apoptotic protein with roles in cell cycle progression. Leukemia 16:1507–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Miyazaki J-I, Hart GW. (2003). The transcription factor PDX-1 is post-translationally modified by O-linked N-acetylglucosamine and this modification is correlated with its DNA binding activity and insulin secretion in min6 β-cells. Arch Biochem Biophys 415:155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Wells L, Comer FI, et al. (2001). Dynamic O-glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins: cloning and characterization of a neutral, cytosolic β-N-acetylglucosaminidase from human brain. J Biol Chem 276:9838–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloster TM, Vocadlo DJ. (2010) Mechanism, structure, and inhibition of O-GlcNAc processing enzymes. Curr Signal Transduct Ther 5:74–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloster TM, Zandberg WF, Heinonen JE, et al. (2011). Hijacking a biosynthetic pathway yields a glycosyltransferase inhibitor within cells. Nat Chem Biol 7:174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross BJ, Kraybill BC, Walker S. (2005). Discovery of O-GlcNAc transferase inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc 127:14588–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross BJ, Swoboda JG, Walker S. (2008). A strategy to discover inhibitors of O-linked glycosylation. J Am Chem Soc 130:440–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahne H, Sobotzki N, Nyberg T, et al. (2013). Proteome wide purification and identification of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins using click chemistry and mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res 12:927–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajduch J, Nam G, Kim EJ, et al. (2008). A convenient synthesis of the C-1-phosphonate analogue of UDP-GlcNAc and its evaluation as an inhibitor of O-linked GlcNAc transferase (OGT). Carbohydr Res 343: 189–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltiwanger RS, Blomberg MA, Hart GW. (1992). Glycosylation of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins. Purification and characterization of a uridine diphospho-N-acetylglucosamine: polypeptide β-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. J Biol Chem 267:9005–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltiwanger RS, Holt GD, Hart GW. (1990). Enzymatic addition of O-GlcNAc to nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins. Identification of a uridine diphospho-N-acetylglucosamine:peptide β-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. J Biol Chem 265:2563–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanover JA. (2001). Glycan-dependent signaling: O-linked N-acetylglucosamine. FaSEB J 15:1865–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanover JA, Forsythe ME, Hennessey PT, et al. (2005). A Caenorhabditis eiegans model of insulin resistance: altered macronutrient storage and dauer formation in an OGT-1 knockout. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:11266–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanover JA, Yu S, Lubas WB, et al. (2003). Mitochondrial and nucleocytoplasmic isoforms of O-linked GlcNAc transferase encoded by a single mammalian gene. Arch Biochem Biophys 409:287–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart GW, Housley MP, Slawson C. (2007). Cycling of O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine on nucleocytoplasmic proteins. Nature 446: 1017–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart GW, Slawson C, Ramirez-Correa G, Lagerlof O. (2011). Cross talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annu Rev Biochem 80:825–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Macauley MS, Stubbs KA, et al. (2010). Visualizing the reaction coordinate of an O-GlcNAc hydrolase. J Am Chem Soc 132:1807–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housley MP, Udeshi ND, Rodgers JT, et al. (2009). A PGC-1α-O-GlcNAc transferase complex regulates FoxO transcription factor activity in response to glucose. J Biol Chem 284:5148–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber AH, Weis WI. (2001). The structure of the β-catenin/E-cadherin complex and the molecular basis of diverse ligand recognition by β-catenin. Cell 105:391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer SPN, Akimoto Y, Hart GW. (2003). Identification and cloning of a novel family of coiled-coil domain proteins that interact with O-GlcNAc transferase. J Biol Chem 278:5399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer SPN, Hart GW. (2003). Roles of the tetratricopeptide repeat domain in O-GlcNAc transferase targeting and protein substrate specificity. J Biol Chem 278:24608–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi M, Yuasa H, Hashimoto H. (2009). Bisubstrate analogues as glycosyltransferase inhibitors. Curr Top Med Chem 9:87–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jancan I, Macnaughtan MA. (2012). Acid dissociation constants of uridine-5’-diphosphate compounds determined by 31phosphorus nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and internal pH referencing. Anal Chim Acta 749:63–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C, Liu T, Wang Z. (2013). O-GlcNAcPRED: a sensitive predictor to capture protein O-GlcNAcylation sites. Mol BioSyst 9:2909–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Lazarus MB, Pasquina L, et al. (2012). A neutral diphosphate mimic crosslinks the active site of human O-GlcNAc transferase. Nat Chem Biol 8:72–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M, Rehwinkel J, Lazarus BD, et al. (2004). The superhelical TPR-repeat domain of O-linked GlcNAc transferase exhibits structural similarities to importin α. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11:1001–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MB, Teng H, Rhee JK, et al. (2004). Characterization of the cellular uptake and metabolic conversion of acetylated N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc) analogues to sialic acids. Biotechnol Bioeng 85: 394–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang E-S, Han D, Park J, et al. (2008). O-GlcNAc modulation at Akt1 Ser473 correlates with apoptosis of murine pancreatic β cells. Exp Cell Res 314:2238–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppler OT, Horstkorte R, Pawlita M, et al. (2001). Biochemical engineering of the N-acyl side chain of sialic acid: biological implications. Glycobiology 11:11R–8R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ. (2011). Chemical arsenal for the study of O-GlcNAc. Molecules 16:1987–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Hanover JA. (2013). Enzymatic characterization of recombinant enzymes of O-GlcNAc cycling In: Brockhausen I, ed. Methods in molecular biology. Volume 1022: glycosyltransferase: methods and protocols. New York: Human Press, 129–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Abramowitz LK, Bond MR, et al. (2014). Versatile O-GlcNAc transferase assay for high-throughput identification of enzyme variants, substrates, and inhibitors. Bioconjug Chem. DOI: 10.1021/bc5001774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Kang DO, Love DC, Hanover JA. (2006a). Enzymatic characterization of O-GlcNAcase isoforms using a fluorogenic GlcNAc substrate. Carbohydr Res 341:971–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Perreira M, Thomas CJ, Hanover JA. (2006b). An O-GlcNAcase-specific inhibitor and substrate engineered by the extension of the N-acetyl moiety. J Am Chem Soc 128:4234–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight ZA, Shokat KM. (2007). Chemical genetics: where genetics and pharmacology meet. Cell 128:425–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivula A, Ruohonen L, Wohlfahrt G, et al. (2002). The active site of cellobiohydrolase Cel6A from Trichoderma reesei: the roles of aspartic acids D221 and D175. J Am Chem Soc 124:10015–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolm-Litty V, Sauer U, Nerlich A, et al. (1998). High glucose-induced transforming growth factor β1 production is mediated by the hexosamine pathway in porcine glomerular mesangial cells. J Clin Invest 101:160–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad RJ, Zhang F, Hale JE, et al. (2002). Alloxan is an inhibitor of the enzyme O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 293:207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreppel LK, Blomberg MA, Hart GW. (1997). Dynamic glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins: cloning and charaterization of a unique O-GlcNAc transferase with multiple tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem 272:9308–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreppel LK, Hart GW. (1999). Regulation of a cytosolic and nuclear O-GlcNAc transferase: role of the tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem 274:32015–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laczy B, Hill BG, Wang K, et al. (2009). Protein O-GlcNAcylation: a new signaling paradigm for the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296:H13–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavogina D, Enkvist E, Uri A. (2010). Bisubstrate inhibitors of protein kinases: from principle to practical applications. Chem Med Chem 5: 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus BD, Love DC, Hanover JA. (2006). Recombinant O-GlcNAc transferase isoforms: identification of O-GlcNAcase, yes tyrosine kinase, and tau as isoform-specific substrates. Glycobiology 16: 415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus BD, Love DC, Hanover JA. (2009). O-GlcNAc cycling: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41:2134–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus MB, Jiang J, Gloster TM, et al. (2012). Structural snapshots of the reaction coordinate for O-GlcNAc transferase. Nat Chem Biol 8: 966–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus MB, Nam Y, Jiang J, et al. (2011). Structure of human O-GlcNAc transferase and its complex with a peptide substrate. Nature 469:564–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavy TM, Bertozzi CR. (2007). A high-throughput assay for O-GlcNAc transferase detects primary sequence preferences in peptide substrates. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 17:3851–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TN, Alborn WE, Knierman MD, Konrad RJ. (2006). Alloxan is an inhibitor of O-GlcNAc-selective N-acetyl-D-D-glucosaminidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 350:1038–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen S, Munday R. (1991). Thiol-group reactivity, hydrophilicity and and a comparison with ninhydrin. Biochem Pharmacol 42:1385–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen S, Panten U. (1988). Alloxan: history and mechanism of action. Diabetologia 31:337–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I, et al. (2004). O-GlcNAcylation regulates phosphorylation of tau: a mechanism involved in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:10804–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Marchase RB, Chatham JC. (2007). Glutamine-induced protection of isolated rat heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury is mediated via the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway and increased protein O-GlcNAc levels. J Mol Cell Cardiol 42:177–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Pang Y, Chang T, et al. (2006). Increased hexosamine biosynthesis and protein O-GlcNAc levels associated with myocardial protection against calcium paradox and ischemia. J Mol Cell Cardiol 40:303–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Yu Y, Fan YZ, et al. (2005). Cardiovascular effects of endomorphins in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Peptides 26:607–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Li L, Wang Y, et al. the acceptor specifity of O-GlcNAc transferase. FASEB J [Online] Available from: http://www.fasebj.org/content/early/2014/04/23/fj.13-246850.long [last accessed 23 April 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- Love DC, Hanover JA. (2005). The hexosamine signaling pathway: deciphering the “O-GlcNAc Code.” Sci STKE 2005, re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love DC, Kochran J, Cathey RL, et al. (2003). Mitochondrial and nucleocytoplasmic targeting of O-linked GlcNAc transferase. J Cell Sci 116:647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubas WA, Frank DW, Krause M, Hanover JA. (1997). O-Linked GlcNAc transferase is a conserved nucleocytoplasmic protein containing tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem 272:9316–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubas WA, Hanover JA. (2000). Functional expression of O-linked GlcNAc transferase: domain structure and substrate specificity. J Biol Chem 275:10983–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller R, Jenny A, Stanley P. (2013). The EGF repeat-specific O-GlcNAc-transferase Eogt interacts with notch signaling and pyrimidine metabolism pathways in Drosophila. PLoS ONE 8:e62835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macauley MS, Vocadlo DJ. (2010). Increasing O-GlcNAc levels: an overview of small-molecule inhibitors of O-GlcNAcase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1800:107–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macauley MS, Whitworth GE, Debowski AW, et al. (2005). O-GlcNAcase uses substrate-assisted catalysis: kinetic analysis and development of highly selective mechanism-inspired inhibitors. J Biol Chem 280:25313–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar G, Harmon A, Candelaria R, et al. (2003). O-glycosylation of Sp1 and transcriptional regulation of the calmodulin gene by insulin and glucagon. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 285:E584–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall S, Bacote V, Traxinger RR. (1991). Discovery of a metabolic pathway mediating glucose-induced desensitization of the glucose transport system. Role of hexosamine biosynthesis in the induction of insulin resistance. J Biol Chem 266:4706–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Fleites C, Macauley MS, He Y, et al. (2008). Structure of an O-GlcNAc transferase homolog provides insight into intracellular glycosylation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15:764–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer TU. (2003). Chemical genetics: tailoring tools for cell biology. Trends Cell Biol 13:270–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClain DA, Lubas WA, Cooksey RC, et al. (2002). Altered glycan-dependent signaling induces insulin resistance and hyperleptinemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:10695–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngoh GA, Facundo HT, Zafir A, Jones SP. (2010). O-GlcNAc signaling in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res 107:171–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngoh GA, Watson LJ, Facundo HT, et al. (2008). Non-canonical glycosyltransferase modulates post-hypoxic cardiac myocyte death and mitochondrial permeability transition. J Mol Cell Cardiol 45: 313–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noach N, Segev Y, Levi I, et al. (2007). Modification of topoisomerase I activity by glucose and by O-Glcnacylation of the enzyme protein. Glycobiology 17:1357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte D, Müller U. (2002). Human O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT): genomic structure, analysis of splice variants, fine mapping in Xq13.1. Mamm Genome 13:62–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell N, Zachara NE, Hart GW, Marth JD. (2004). Ogt-dependent X-chromosome-linked protein glycosylation is a requisite modification in somatic cell function and embryo viability. Mol Cell Biol 24: 1680–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offen W, Martinez-Fleites C, Yang M, et al. (2006). Structure of a flavonoid glucosyltransferase reveals the basis for plant natural product modification. EMBO J 25:1396–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]