Abstract

Rapid, inexpensive, and sensitive detection of bacterial pathogens is an important goal for several aspects of human health and safety. We present a simple strategy for detecting a variety of bacterial species based on the interaction between bacterial cells and the viruses that infect them (phages). We engineer phage M13 to display the receptor-binding protein from a phage that naturally targets the desired bacteria. Thiolation of the engineered phages allows the binding of gold nanoparticles, which aggregate on the phages and act as a signal amplifier, resulting in a visible color change due to alteration of surface plasmon resonance properties. We demonstrate the detection of two strains of Escherichia coli, the human pathogens Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Vibrio cholerae, and two strains of the plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris. The assay can detect ∼100 cells with no cross-reactivity found among the Gram-negative bacterial species tested here. The assay can be performed in less than an hour and is robust to different media, including seawater and human serum. This strategy combines highly evolved biological materials with the optical properties of gold nanoparticles to achieve the simple, sensitive, and specific detection of bacterial species.

Keywords: gold nanoparticles, phage display, bacteria, detection, biosensor

The rapid detection of specific bacterial species has many potential applications in medicine and environmental and food safety.1,2 Conventional methods, including culturing, ELISA, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods, have important drawbacks, such as long processing times and the need for specialized equipment.3,4 Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are an ideal candidate for rapid biosensing based on the sensitivity of the surface plasmon resonance to aggregation state, which produces a visible color change. AuNPs also have other advantages, including high surface area to volume ratio and facile surface modification.5,6 Indeed, antibody-conjugated AuNPs have been used to detect pathogenic bacteria in multiple systems.7−11 However, the isolation and production of antibodies can be costly and nontrivial, and optimization may be required to improve stability and solubility in the relevant context. Therefore, AuNP-based technology utilizing a different molecular mechanism for targeting is desirable.

The high-affinity, high-specificity interactions that characterize antibodies are the result of intense evolutionary pressure on molecular recognition between host and pathogen. A similar selective pressure has driven the long-term evolution of tight interactions between receptor-binding proteins (RBPs) of bacteriophages and receptors on bacterial host cells. For example, the effective affinity of phage M13 for its bacterial host (F+E. coli) is reported to be <2 pM.12 The breadth of host range depends on the phage, but phages can be specific to a bacterial species or strain.13 Phage RBPs are therefore an interesting potential source of affinity reagents for bacterial detection.

Phages have been studied previously for pathogen detection because they are less expensive to produce and more stable to storage and assay conditions compared with antibodies.14 Phage-based assays include infection of the host cells causing expression of a phage-encoded reporter gene15−17 and phages labeled with fluorescent or enzymatic tags.18−22 Phage proteins conjugated to a gold surface have been used to capture bacteria and detect the changes in surface plasmon resonance.23,24 However, compared to the AuNP-based approach described here, these detection modalities require extended time and equipment, which may not be available in certain settings (e.g., point-of-care or field work).

Here, we combine the AuNP detection modality with chimeric phages that display the RBP of a phage that naturally targets the desired bacterial species. In this approach, the capsids of chimeric phages are thiolated, and the phages are incubated with the bacteria. The attachment of phages to bacteria and subsequent aggregation of AuNPs on the capsid leads to a colorimetric signal (Figure 1). M13 was used as the phage scaffold, on which RBPs from other filamentous phages (genus Inovirus) were displayed. Use of a scaffold phage rather than native phage is desirable because most phages are poorly characterized, posing difficulties for propagation and protocol standardization. In contrast, high titers of M13 derivatives can be readily produced in Escherichia coli and handled downstream. Members of Inovirus infect a variety of Gram-negative genera of medical and agricultural interest, including Pseudomonas, Xanthomonas, Yersinia, and Neisseria.25 The RBP, or minor coat protein, pIII, consists of two domains. The N-terminal domain of pIII (encoded by g3p-N) attaches to the primary host receptor (e.g., the F pilus for the Ff phages, such as M13), while the C-terminal domain interacts with a secondary host receptor and aids cell penetration.26 The replacement of g3p-N by a homologous domain switches attachment specificity to the corresponding host in at least two cases.27,28 We extend this strategy to additional Inovirus members and thiolate the resulting chimeric phages for interaction with AuNPs. This strategy demonstrates rapid and specific detection of two strains of E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Vibrio cholerae, and two strains of the plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris with a detection limit of ∼100 cells. We first describe validation of this technique using thiolated M13 phage to aggregate AuNPs to detect E. coli. We then describe the generalization of this strategy to use RBPs from five other filamentous phages, allowing the targeting of their respective host species or strain.

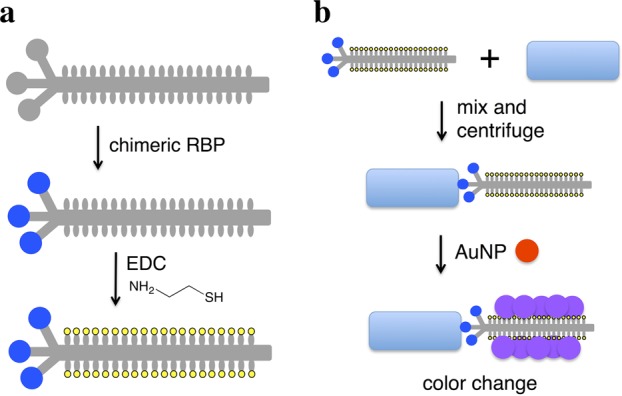

Figure 1.

Scheme for chimeric phage detection of bacterial species. (a) M13 phage (gray) is engineered to express a foreign receptor-binding protein (blue circle) fused to the minor coat protein pIII, and the chimeric phage is thiolated (yellow) through EDC chemistry. (b) Thiolated chimeric phages are added to media containing bacteria (blue rectangle) and may attach to the cells. Centrifugation separates cell-phage complexes from free phage. The pellet is resuspended in solution with gold nanoparticles (red), whose aggregation on the thiolated phage produces a color change (purple).

Results and Discussion

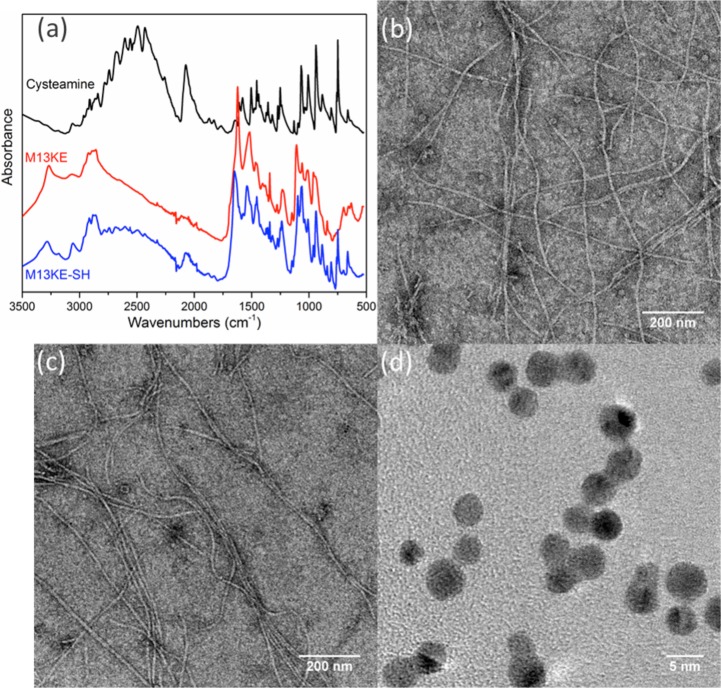

The phages are chemically modified by thiolation to generate an interaction with AuNPs. Each major capsid protein (pVIII) of the M13 scaffold contains at least three solvent-accessible carboxylic amino acids at the N-terminus (Glu2, Asp4, and Asp5), which can be potentially modified by EDC chemistry under mild conditions. As a proof of concept, the wild-type M13KE phages were thiolated with cysteamine to detect E. coli ER2738 bacteria. The concentration of chemically incorporated thiol groups was quantified with Ellman’s assay, while the concentration of phage particles was determined by real-time PCR. Thus, we estimated that the chemical modification led to the addition of ∼1800 thiol groups per virion (Table S1). This level is consistent with a substantial fraction of the phage coat being modified (∼2700 copies of pVIII per virion).29 Attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) analysis further confirmed the presence of thiol groups on the phage after modification (Figure 2a). In addition, the ζ potential of the phage is expected to increase upon thiolation due to the masking of Glu and Asp residues. Indeed, the ζ of unmodified M13KE phage in water was measured to be −44.3 mV, while that of the thiolated M13KE phage was −10.31 mV. These results support the successful functionalization of the phage.

Figure 2.

Preparation of thiolated phage capsids and AuNPs. (a) ATR-FTIR of purified thiolated M13KE phage indicates gain of S–H stretching (2550 cm–1) and C–S stretching (659 cm–1) signals. Shown are cysteamine (black), phage before modification (red), and phage after modification (blue). Representative TEM images of wild-type M13KE phage (b) before and (c) after thiolation indicate little change in gross morphology. (d) TEM image of AuNPs shows homogeneous particles of ∼4 nm diameter.

To check the gross morphology of thiolated M13KE virions, we measured their hydrodynamic behavior by dynamic light scattering (DLS). The effective diameter of the wild type phage showed little change after modification (Figure S1). Normal virion morphology and lack of agglomeration30,31 was also verified by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Figure 2b,c). Another potential concern was that thiolation of pIII might interfere with binding to the host cell because there may be solvent-accessible carboxylic amino acids (e.g., Glu2 and Glu5) on pIII.32 The thiolated M13KE phage was tested for attachment to host cells expressing a cyan-fluorescent protein.33 The virions were labeled with a fluorescent dye FITC through thiol–maleimide click chemistry and purified. After incubation at room temperature for 30 min to allow for attachment, the sample was visualized by confocal microscopy. The fluorescence of the modified phages was found to be in close proximity to the cell surfaces (Figure S2). Thus, thiolated phages exhibit normal morphology and retain the ability to bind host cells. Furthermore, the dissociation constants (Kd) of wild type M13KE and thiolated M13KE for E. coli (F+) were found to be similar (see Figure S3 and the Supporting Methods), indicating that thiolation did not substantially perturb attachment to host cells.

Citrate-stabilized AuNPs were synthesized and verified by TEM to have a diameter of ∼4 nm (Figure 2d). DLS showed a relatively monodispersed population centered at diameter ∼8 nm (Figure S4). The apparent size difference is reasonable considering the difference in hydration state and the intensity-based weighting of the DLS data. The ζ potential of the AuNPs in water was found to be −45.1 mV, indicating a highly negatively charged surface, intended to stabilize the colloidal particles in solution.34

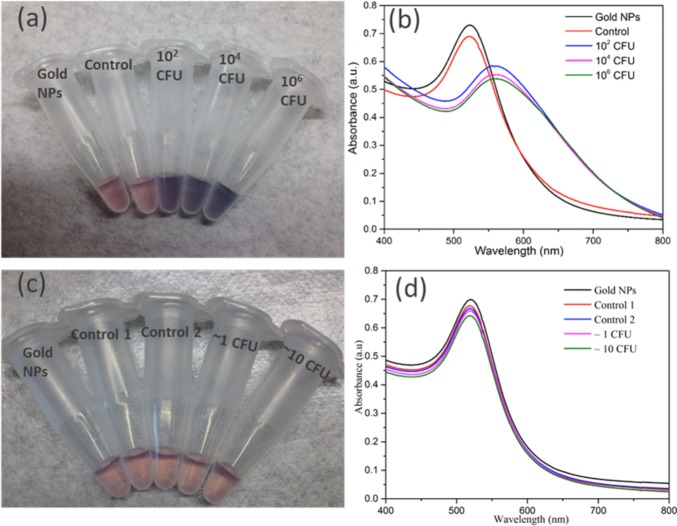

To test the assay principle using thiolated M13KE phage with AuNPs for detection of E. coli, varying concentrations of E. coli ER2738 were diluted into tap water and incubated with the phage for 30 min. The cells (with attached phages) were washed twice and then resuspended in a solution containing AuNPs. In the absence of bacteria or in the presence of unmodified M13KE, a red solution is obtained, consistent with the color of the un-aggregated AuNPs in solution. The aggregation of AuNPs on thiolated phage, indicating the presence of E. coli, was observed by a change in the absorbance spectrum, resulting in a purple solution easily observed by the naked eye (Figure 3). This assay can detect as few as 60 CFU cells (Figure S5). Therefore, the limit of detection is on the order of ∼102 CFU, indicating the high sensitivity of the present technique. Similar sensitivity is seen when a more-concentrated solution of AuNPs is used (Figure S6). While this aggregation-based assay is not suitable for creating a standard curve with a large dynamic range (Figure S7), a dilution series of a sample could be used to obtain a rough order-of-magnitude estimate of the concentration of a specific bacterial species. In particular, the dilution at which the number of cells becomes less than ∼100 could be identified and used to infer the concentration of the original sample. To characterize the interaction, TEM images were obtained for the mixtures (Figure S8). Large aggregates containing AuNPs and thiolated phages were observed in samples containing thiolated phages and E. coli cells but were absent when unmodified M13KE was used. Attachment of AuNPs to free bacteria was not observed by TEM, consistent with electrostatic repulsion given the negative zeta potential of AuNPs and E. coli (ζ = −8.88 mV, measured here). The phages are also negatively charged (ζ = −10.31 mV, measured for thiolated M13KE), so AuNP association with the phages is driven by the Au–S interaction despite electrostatic repulsion. It should be noted that free filamentous phage do not pellet at the centrifugation speeds used to pellet the cells and cell–phage complexes. Overall, in this assay, unbound virions were removed and the AuNPs aggregated on the thiolated phages attached to the host bacteria, resulting in a visible color change.

Figure 3.

Detection of E. coli with thiolated M13KE and AuNPs. (a, c) Digital photos and (b, d) UV–vis spectra are shown. From left to right in panel a, samples contain AuNPs and: no bacteria or phages (black line in panel b), unmodified M13KE with 106 CFU E. coli (red line in panel b), and thiolated M13KE with E. coli at 102, 104, and 106 CFU (blue, magenta, and green lines, respectively, in panel b). From left to right in panel c, samples contain AuNPs and no bacteria or phages (black line in panel d), unmodified M13KE phage and ∼1 or ∼10 CFU of E. coli (red or blue lines in panel d, respectively), and thiolated M13KE phage and ∼1 or ∼10 CFU of E. coli (magenta or green lines in panel d, respectively).

The robustness of a bacterial detection platform in different media is an important consideration for potential applications. To test this, thiolated M13KE was incubated with E. coli in seawater and human serum with the remaining steps carried out as described above. Incubations in all media yield a detectable colorimetric response to the presence of E. coli (Figures 4 and S9). E. coli can survive in seawater for several days, similar to survival in freshwater.35−38 The change in absorption spectrum for samples incubated in human serum was less pronounced than that for the different samples of water. Given that human serum contains a complex mixture of proteins and other macromolecules,39,40 it is possible that some of these components might interfere with the interaction among bacteria, phage, and AuNPs. Nevertheless, the color change of AuNPs on phages is still visible even in this complex media.

Figure 4.

Detection of E. coli ER2738 in (a, b) seawater or (c, d) human serum. (a, c) Digital photos and (b, d) UV–vis spectra are shown. From left to right in panels a and c, samples contain AuNPs and no bacteria or phages (black lines in panels b and d), unmodified M13KE with 106 CFU E. coli (red lines in b and d), and thiolated M13KE with E. coli at 102, 104, and 106 CFU (blue, magenta, and green lines, respectively, in panels b and d).

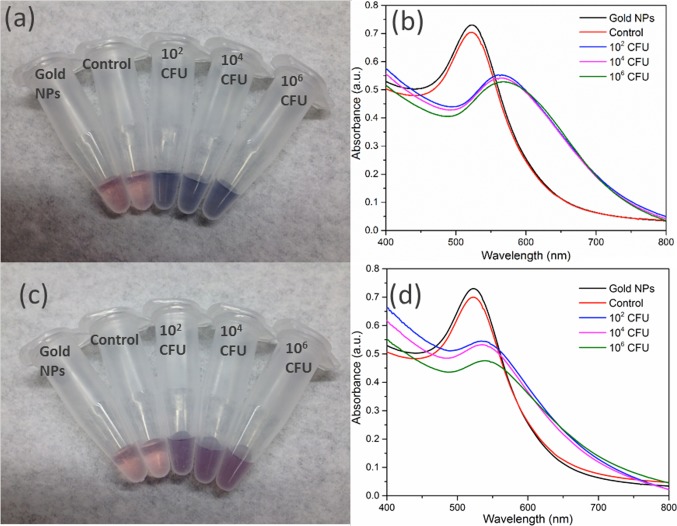

Having validated the technique to detect E. coli, we then engineered phages capable of recognizing pathogenic bacterial species. We cloned chimeric phages using a derivatized M13 genome as a scaffold to display the RBP from five other filamentous phages: CTXϕ, If1,41,42 ϕXv,28 ϕLf,28 and Pf143 (Table 1). In each case, the RBP gene of M13 (g3p-N) was replaced by its known or putative homologue from the other phage. The RBP sequences were adjusted for codon bias in E. coli but were used without other optimization. Successful construction was verified by restriction digestion and sequencing (see the Supporting Information). The resulting phages were produced in E. coli cells after transformation. The chimeric phages (M13-g3p(CTXϕ), M13-g3p(Pf1), M13-g3p(ϕLf), M13-g3p(ϕXv), and M13-g3p(If1)) were thiolated (Table S1) and used to detect their respective host bacteria in tap water, seawater, and human serum. The thiolated chimeric phages showed comparable sensitivity to detect their host bacteria compared to M13KE with F+E. coli (Figures 5 and S10–S14). The limit of detection in all cases was ∼102 CFU, demonstrating the adaptability of this approach to targeting different bacterial species and strains.

Table 1. Chimeric Phages and Target Bacterial Species.

| bacterial target species | strain used | source of RBP | designation of chimeric phage |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (F+) | ER2738 | wild-type M13 | |

| V. cholerae | 0395 (gift of M. Mahan) | CTXϕ | M13-g3p(CTXϕ) |

| P. aeruginosa | ATCC25102 (Schroeter) Migula | Pf1 | M13-g3p(Pf1) |

| X. campestris (pv campestris) | ATCC33913 | ϕLf | M13-g3p(ϕLf) |

| X. campestris (pv vesicatoria) | ATCC35937 | ϕXv | M13-g3p(ϕXv) |

| E. coli (I+) | ATCC27065 (Migula) Castellani and Chalmers | Ιϕ1 | M13-g3p(If1) |

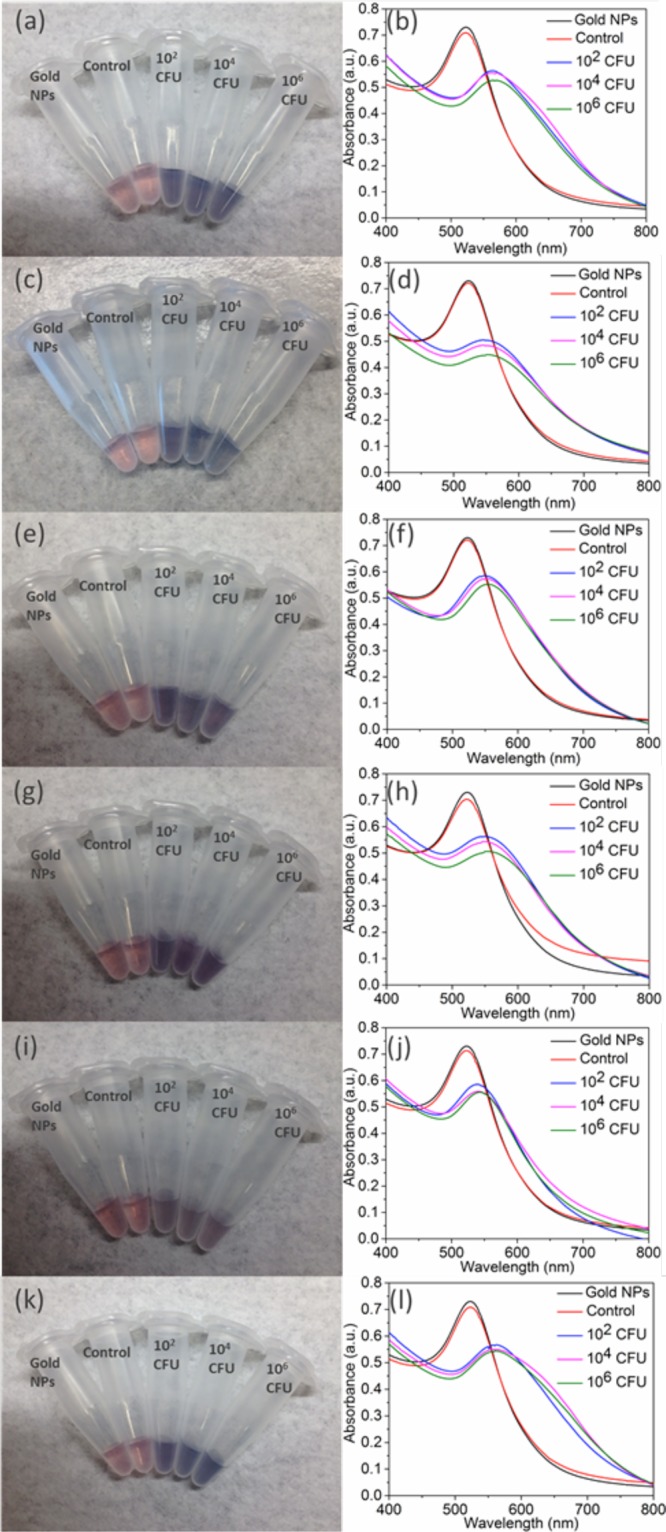

Figure 5.

Detection of several bacterial species in relevant media: (a, b) V. cholerae 0395 in seawater, (c, d) X. campestris (pv campestris) in tap water, (e, f) X. campestris (pv vesicatoria) in tap water, (g, h) P. aeruginosa in tap water, and (i, j) human serum and (k, l) E. coli (I+) in tap water. The corresponding chimeric phage (Table 1) was used in each case. Shown are digital photographs (left) and UV–vis spectra (right). Left column: from left to right, samples contain AuNPs and no bacteria or phages (black line in right column), unmodified phage with 106 CFU host bacteria (red line in right column), and thiolated phage with host bacteria at 102, 104, and 106 CFU (blue, magenta, and green lines, respectively, in the right column).

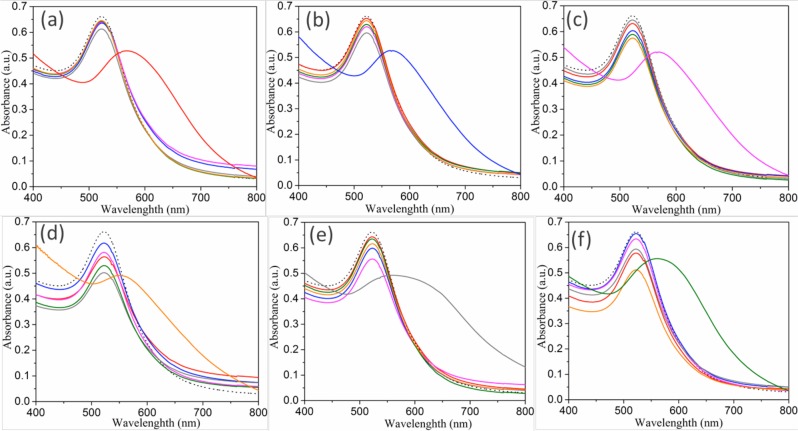

Because the specificity of detection is important for identifying bacteria, each of the six phages (M13KE and the five chimeric phages) was tested for its ability to detect the hosts of the other phages. No shift of SPR peaks in the UV–vis spectrum was observed in any case (Figure 6), indicating little cross-reactivity within the group of Gram-negative organisms tested. This is likely a reflection of the specificity of the source phages themselves. We also tested whether detection by individual phages was affected in a heterogeneous mixture of bacteria [E. coli (F+), V. cholerae, and P. aeruginosa]. The red-shift of SPR peaks only occurred when the bacterial mixture contained the host cells targeted by the phage [M13KE, M13-g3p(CTXϕ), or M13-g3p(Pf1), respectively; Figure S15], confirming the expected specificity of the phages.

Figure 6.

Specificity of bacterial detection. Absorption spectra of (a) M13KE, (b) M13-g3p(CTXϕ), (c) M13-g3p(If1), (d) M13-g3p(Pf1), (e) M13-g3p(ϕLf), and (f) M13-g3p(ϕXv) when incubated with different bacterial species and AuNPs. Bacterial species shown are E. coli (F+) (red), V. cholerae 0395 (blue), E. coli (I+) (magenta), P. aeruginosa (orange), X. campestris (pv campestris) (gray), and X. campestris (pv vesicatoria) (green). The spectrum of AuNPs alone (dotted black line) is also shown.

All of the chimeric phages that we attempted gave high sensitivity and specificity in the AuNP-based assay without empirical optimization. The generalizability of this strategy might be understood in terms of the evolutionary “arms race” between bacteria and phage: both host receptors and phage RBPs are characterized by rapid evolution, and thus, it is likely that both the phage scaffold and the RBPs have evolved high tolerance to changes in the RBP. Similarly, the assay tolerated tap water and filtered seawater with negligible change. Although human serum decreased the absorbance shift, the assay was still readily interpretable in this media. The tolerance of the assay to different conditions may also reflect the evolutionary history of phages, which have been selected to attach to their hosts in natural, sometimes harsh, environments. The primary cost associated with the assay is cloning the chimeric phage. Given this, the assay itself can be performed in less than an hour with a reagent cost of <$1.40 per assay (Table S2). It is possible to decrease the reagent costs further by use of silver nanoparticles, which give a yellow to orange color change upon aggregation and also interact strongly with thiols.44 Indeed, AgNPs can be used in analogous fashion in our assay (Figures S16 and S17). In addition, a potentially interesting feature of AgNPs is their antimicrobial properties.45 An Eppendorf centrifuge is used to separate bacteria from free phage here, although separations might also be achieved by less-expensive means.15,46 Labor costs for the assay, as presented here, are likely to exceed materials costs.

Conclusions

Here, we have presented a platform for the rapid, inexpensive, sensitive, and specific detection of microbial pathogens, based on the phage-bacteria interactions that have evolved in nature.47−49 In this design, the RBP of a foreign phage was displayed on an M13 scaffold, creating chimeric phages to bind different host bacteria. The phages were further chemically modified to interact with AuNPs, bridging the target bacteria to the AuNPs, which act as a signal amplifier, as aggregation of the AuNPs causes a visible shift in SPR absorbance. The limit of detection (∼100 cells) in the present assay is comparable with other high-sensitivity assays,50−53 and might be lowered by using a lower resuspension volume or by addition of a culturing step. No cross-reactivity was detected for the organisms tested here, although specificity likely depends on the characteristics of the phage RBPs. Some versatility has been demonstrated here, including detection of two human pathogens as well as two strains of a plant pathogen, with no experimental optimization required. This straightforward approach may be useful for detection and identification of bacteria in situations in which time and/or equipment resources are limited.

Methods

Materials

Reagents were obtained from the following sources: gold(III) chloride trihydrate (HAuCl3, 99.9%, Sigma), sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 98%, Fisher Scientific), trisodium citrate dehydrate (99.9%, Sigma), E. coli (Migula) Castellani and Chalmers (ATCC27065, ATCC), Xanthomonas campestris pv campestris (ATCC33913), X. campestris pv vesicatoria (ATCC35937), P. aeruginosa (Schroeter) Migula (ATCC 25102), V. cholerae 0395 (donation from Prof. Michael J. Mahan, UCSB), M13KE phage (NEB), M13-NotI-Kan construct,12 sodium chloride (NaCl, 99%, Fisher BioReagents), tryptone (99%, Fisher BioReagents), yeast extract (99%, Fisher BioReagents), human serum (from male AB clotted whole blood, Sigma), E. coli ER2738 (NEB), fluorescein-5-maleimide (97%, TCI), N-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC, 99%, Sigma), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS, 98%, Sigma), cysteamine (98%, Sigma), poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG-8000, Sigma), dialysis kit (MWCO 3500 Da, Spectrum Laboratories), tetracycline (Sigma), kanamycin sulfate (Sigma), Top 10F′ cyan cells (Thermo Fisher), Mix and Go competent cells (Zymo Research), QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen), QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen), and KpnI-HF/NotI-HF restriction enzyme and T4 DNA ligase (NEB).

Bacterial Growth and Phage Production

E. coli ER2738 cells were grown in LB with tetracycline (10 μg mL–1) at 37 °C overnight. A total of 200 μL of an overnight E. coli culture was used to inoculate a 20 mL culture in a 250 mL Erlenmyer flask. To produce wild-type M13, 1 μL of M13KE phage solution (1013 pfu/mL) was added to the cell culture, and the flask was shaken at 37 °C and 250 rpm for 4–5 h. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 4500g for 10 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube for repeat centrifugation. The top 16 mL of supernatant was then transferred to a new tube, and 4 mL of 2.5 M NaCl/20% PEG-8000 was added and the solution mixed. The solution was stored at 4 °C overnight to precipitate the phages. The phage precipitates were collected by centrifugation at 14 000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C and dissolved in 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer. The solution was centrifuged briefly to pellet any cell debris. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube, and 200 μL of 2.5 M NaCl/20% PEG-8000 was added and the solution mixed. The sample was incubated on ice for 1 h, and the phage was centrifuged at 14 000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the phage pellet was resuspended in 200 μL of PBS buffer. The phage concentration was determined by real-time PCR (see below).

Real-Time PCR Quantitation of Phages

The concentration of phage particles was determined by real-time PCR (forward primer: 5′-AAACTGGCAGATGCACGGTT-3′; reverse primer: 5′-AACCCGTCGGATTCTCCG-3′; PCR conditions: 95 °C for 10 min and then 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 60 s) with SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix and Biorad C1000 PCR machine. See Figure S11 for the standard curve.

Construction and Production of Chimeric Phage

The RBP of M13 (g3p) was engineered to replace its N-terminal domain (g3p-N) with the homologous domain from a phage having specificity toward the target bacterial species (Table 1). A plasmid containing the g3p-N homologue of the source phage flanked by KpnI and NotI restriction sites (see the Supporting Information) was synthesized (IDT) and transformed into Mix and Go competent E. coli cells. The cells were grown in LB media with ampicillin (10 μg mL–1), and the plasmid was isolated using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit. The M13-NotI-Kan phage vector, in which a NotI restriction site was introduced between the N- and C-terminal domains of M13, was prepared previously.12 The extracted plasmid and M13-NotI-Kan vector were digested by KpnI-HF and NotI-HF. The desired products were isolated by gel electrophoresis and purified with QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit. The g3p-N homologue was ligated into the M13-NotI-Kan vector using T4 DNA ligase. The recombinant plasmid was then transformed into Mix and Go competent cells, which were plated on LB with kanamycin (50 μg mL–1) and IPTG (0.1 M) and incubated at 37 °C overnight. A single colony was selected and cultured in LB media with kanamycin (50 μg mL–1) and IPTG (0.1 M) in a shaking incubator at 37 °C overnight. The recombinant plasmid was isolated using a QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit. The inserted gene in the phage vector was amplified by PCR (forward primer: 5′- TTTGGAGCCTTTTTTTTGGAGATTTTCAAC-3′; reverse primer: 5′- CACCACCAGAGCCTGC-3′; PCR conditions: 95 °C for 3 min, then 11 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 52.3 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 60 s) and Sanger sequenced (UC Berkeley core facility) to confirm the sequence of the chimeric phage genome. To produce chimeric phages, a colony containing the chimeric phage genome was used to inoculate a liquid culture and shaken overnight at 37 °C. The phages were precipitated and purified by the double-polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation method described above.

Thiolation of Chimeric Phages

The phages were chemically modified to incorporate thiol groups by coupling to cysteamine in sterile PBS buffer at pH 7.9 according to a modified protocol.32 Oxygen in the phage solution and other reagents was removed by purging with dry nitrogen for 30 min. A total of 1012 phages were reacted with 1 mM EDC, 1 mM NHS, and 1 mM cysteamine in a volume of 2 mL with gentle stirring at room temperature. The same amount of EDC was added 2 more times at time intervals of 30 min. The reaction ran overnight before extensive dialysis through regenerated cellulose dialysis tubing (molecular weight cutoff of 3500 Da) against 250 mL of PBS buffer and 250 mL Milli-Q water followed by two rounds of PEG/NaCl precipitation. The concentration of chemically incorporated thiol groups was quantified with Ellman’s assay using a cysteine as standard.54 The number of thiol groups per phage was estimated by dividing the number of thiol groups by the number of phage particles, quantified by real-time PCR. See Figure S18 for standard curves.

Visualization of Attachment of Thiolated M13 Phage to E. coli

A total of 1011 thiolated phages produced from M13KE were incubated with 2 mg/mL fluorescein-5-maleimide in 1 mL of PBS buffer (pH 7.0) with gentle stirring at room temperature overnight. Free fluorescein-5-maleimide was removed with extensive dialysis (MWCO 3500 Da) in 500 mL of PBS buffer (pH 7.0), and phages were purified by two rounds of PEG/NaCl precipitation. Phages were resuspended in 200 μL of PBS buffer. The fluorescein-conjugated thiolated M13 phages (M13-FITC-SH) were incubated with 1 mL of Top 10F′ cells expressing cyan fluorescent protein at an optical density ∼0.6 for 30 min at room temperature.12 Free phages were removed by centrifugation at 5000 rpm and discarding of the supernatant. The pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of PBS buffer for microscopy. The fluorescence images were obtained on a Leica SP8 confocal microscope (Leica, Germany) with excitation at 405 nm (NRI, UCSB).

Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles

The gold nanoparticles were synthesized using sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as the reducing agent and trisodium citrate as the capping agent through a modified method by Oda et al.55 Typically, 0.23 mL of 0.1 M HAuCl4·3H2O aqueous solution was added into 90 mL of deionized water, followed by the injection of 2 mL of 38.8 mM trisodium citrate solution. Then 1 mL of 0.075 wt % freshly prepared NaBH4 solution (in 38.8 mM trisodium citrate solution) was added after 5 min of stirring, and the reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. When desired, AuNPs were concentrated by ultrafiltration to approximately half the original volume with an Amicon Ultra-4 10 000 filter.

Detection of Bacterial Cells Using Chimeric Phage and AuNPs

E. coli ER2738 were grown in LB with tetracycline (10 μg mL–1) at 37 °C to an optical density (OD600) of ∼0.6–1. The relationship between optical density and colony-forming units was determined by plating dilutions of the culture and counting colonies. The propagation procedure for other cells is given separately below. The cells were then diluted to desired concentrations in different media: tap water (from laboratory faucets at UCSB), seawater (from the Pacific Ocean collected at the UCSB beach, filtered with 0.45 μm vacuum filter before use), and human serum. The amount of cells is estimated based on the dilution series, so the number of cells in a ∼1 or ∼10 CFU sample will vary from the expectation value due to stochastic sampling and these values should be taken as approximations. A total of 200 μL of phage (1011 PFU/mL) was added to 1 mL of cell suspension and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The cells (and attached phages) were spun down by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The 1.2 mL of supernatant was discarded by pipetting. The pellet was washed with 0.5 mL of Milli-Q water twice before resuspension in 100 μL of AuNPs solution. The color change was recorded with a digital phone camera (iPhone 4s, Apple), and the absorbance of the solutions was measured by UV–vis spectroscopy.

Specificity of Bacterial Detection

The specificity of detection was tested in the same assay as described above, using a different bacterial species or strain from the known host of the phage source of the g3p-N homologue (Table 1). Detection was also performed in a mixture of host cells [E. coli ER2738, V. cholerae 0395, and P. aeruginosa (ATCC25102)] in an analogous fashion.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

TEM was performed on a Tecnai FEI G2 Sphera microscope (MRL, UCSB). The samples were prepared by applying a few drops of solution onto TEM grids coated with a 20 nm thick carbon film. Phage samples (5 μL) pipetted onto the TEM grids for 5 min, followed by rinsing with 10 μL of Milli-Q water. The grids were then exposed to 8 μL of a 2% uranyl acetate for 1 min as negative stain. Excess stain was removed, and the grids were rinsed again with Milli-Q water before drying in air.

Dynamic Light Scattering and ζ Potential Measurements

DLS and ζ potential were measured by using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZSP operating a 4 mW He–Ne laser at 633 nm. Each sample was allowed to equilibrate for 2 min at constant temperature of 25 °C prior to analysis. All results are averages of a minimum of three individual samples in which data from each sample are an average of 5 measurements, each consisting of 10 runs. Sizes reported are intensity-weighted diameter. Data was processed using Malvern Zetasizer software v7.11. The raw data were extracted and plotted in OriginPro 2015.

Attenuated Total Reflection Infrared Spectra Measurement

ATR-FTIR spectra were measured with a Nicolet iS10 FTIR using a MCT detector and a Harrick Scientific Corporation GATR accessory (MRL at UCSB).

Ultraviolet–Visible Spectra Measurement

UV–vis spectral and kinetic data were collected on a Shimadzu UV-1800 UV–vis spectrophotometer with a quartz spectrasil UV–vis cuvette using direct detection at a slit width of 2 nm (CNSI at UCSB).

Propagation of Bacteria

V. cholerae Propagation

The propagation of V. cholerae was carried out according to a reported protocol.56 A single colony of V. cholerae was selected and grew in 5 mL of lysogeny broth medium (pH 7) without antibiotics in a 50 mL Falcon tube at 37 °C overnight. The bacterial concentration was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm [y (CFU/mL) = 8 × 108× (OD600); the conversion factor was determined by colony formation titering assay in our lab].

P. aeruginosa ATCC 25102 (Schroeter) Migula Propagation

The strain ATCC 25102(Schroeter) Migula was propagated in ATCC Medium 3 nutrient broth. A single colony of P. aeruginosa was selected and grown in 5 mL of broth without antibiotics in a 50 mL Falcon tube at 37 °C for 24 h. The bacterial concentration was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm [y (CFU/mL) = 2.0 × 108× (OD600) + 4.0 × 106 according to a previous report].57

X. campestris (pv campestris) ATCC33913 Propagation

The strain ATCC33913 was propagated in ATCC 73 YGC medium. A single colony of X. campestris (pv campestris) was selected and grown in 5 mL of broth without antibiotics in a 50 mL Falcon tube at 26 °C for 48 h. The bacterial concentration was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600 of 0.1 = 108 CFU/mL according to a previous report).58

X. campestris (pv vesicatoria) ATCC35937 Propagation

The ATCC35937 was propagated in ATCC 1475 medium. A single colony of X. campestris (pv vesicatoria) was selected and grown in 5 mL of broth without antibiotics in a 50 mL Falcon tube at 28 °C for 48 h. The bacteria concentration was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600 of 0.2 = 108 CFU/mL according to a previous report).59

E. coli (I+) ATCC27065 (Migula) Castellani and Chalmers Propagation

The strain ATCC27065 was propagated in ATCC 265 medium. A single colony of E. coli (I+) was selected and grown in 5 mL of broth without antibiotics in a 50 mL Falcon tube at 37 °C for 24 h. The bacterial concentration was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm [y (CFU/mL) = 4.0 × 108× (OD600) + 2.18 × 107 determined by colony formation titering assay in our lab].

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the NIH (DP2 GM123457-01) and the Institute for Collaborative Biotechnologies (contract W911NF-09-0001 from the U.S. Army Research Office) is acknowledged. The authors thank M. Mahan for bacterial strains and advice and S. Verbanic for the rtPCR standard curve.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.8b06395.

Gene sequences; additional details on the supporting methods; figures showing size distributions, confocal microscopy results, binding curves, detection and approximate quantification of E. coli, TEM images of E. coli, limits of detection, detection of experimental species, specificity of bacterial detection, size distributions, and standard curves of Ellman’s assay and real-time PCR; tables showing the number of thiol groups per hybrid phage and approximate cost of consumable reagents (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ahmed A.; Rushworth J. V.; Hirst N. A.; Millner P. A. Biosensors for Whole-Cell Bacterial Detection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 631–646. 10.1128/CMR.00120-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slomovic S.; Pardee K.; Collins J. J. Synthetic Biology Devices for in Vitro and in Vivo Diagnostics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 14429–14435. 10.1073/pnas.1508521112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgrader P.; Benett W.; Hadley D.; Richards J.; Stratton P.; Mariella R. Jr.; Milanovich F. PCR Detection of Bacteria in Seven Minutes. Science 1999, 284, 449–450. 10.1126/science.284.5413.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadi L.; Luo J. L.; Hibbs D. E.; Perry J. D.; Anderson R. J.; Orenga S.; Groundwater P. W. Methods for the Detection and Identification of Pathogenic Bacteria: Past, Present, and Future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4818–4832. 10.1039/C6CS00693K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldewachi H.; Chalati T.; Woodroofe M. N.; Bricklebank N.; Sharrack B.; Gardiner P. Gold Nanoparticle-Based Colorimetric Biosensors. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 18–33. 10.1039/C7NR06367A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha K.; Agasti S. S.; Kim C.; Li X.; Rotello V. M. Gold Nanoparticles in Chemical and Biological Sensing. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 2739–2779. 10.1021/cr2001178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesniewski A.; Los M.; Jonsson-Niedziolka M.; Krajewska A.; Szot K.; Los J. M.; Niedziolka-Jonsson J. Antibody Modified Gold Nanoparticles for Fast and Selective, Colorimetric T7 Bacteriophage Detection. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014, 25, 644–648. 10.1021/bc500035y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B. Y.; Li X. Z.; Dong Y. H.; Wang B.; Li D. Y.; Shi Y. M.; Wu Y. Y. Colorimetric Sensor Array Based on Gold Nanoparticles with Diverse Surface Charges for Microorganisms Identification. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 10639–10643. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b02594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Zhao Q.; Wang C. A.; Lu X. F.; Li X. F.; Le X. C. Detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Using Gold Nanoparticle Labeling and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 3399–3403. 10.1021/ac100325f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma M. S.; Rogowski J. L.; Jones L.; Gu F. X. Colorimetric Biosensing of Pathogens using Gold Nanoparticles. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 666–680. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Alocilja E. C. Gold Nanoparticle-Labeled Biosensor for Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Bacterial Pathogens. J. Biol. Eng. 2015, 9, 16. 10.1186/s13036-015-0014-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A.; Jimenez J.; Derr J.; Vera P.; Manapat M. L.; Esvelt K. M.; Villanueva L.; Liu D. R.; Chen I. A. Inhibition of Bacterial Conjugation by Phage M13 and Its Protein g3p: Quantitative Analysis and Model. PLoS One 2011, 6, 1–11. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores C. O.; Meyer J. R.; Valverde S.; Farr L.; Weitz J. S. Statistical Structure of Host–Phage interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, E288–E297. 10.1073/pnas.1101595108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo R.; Singh A.; Arya S. K.; Beadle B.; Glass N.; Tanha J.; Szymanski C. M.; Evoy S. Surface-Immobilization of Chromatographically Purified Bacteriophages for the Optimized Capture of Bacteria. Bacteriophage 2012, 2, 15–24. 10.4161/bact.19079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derda R.; Lockett M. R.; Tang S. K. Y.; Fuller R. C.; Maxwell E. J.; Breiten B.; Cuddemi C. A.; Ozdogan A.; Whitesides G. M. Filter-Based Assay for Escherichia coli in Aqueous Samples Using Bacteriophage-Based Amplification. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 7213–7220. 10.1021/ac400961b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funatsu T.; Taniyama T.; Tajima T.; Tadakuma H.; Namiki H. Rapid and Sensitive Detection Method of a Bacterium by using a GFP Reporter Phage. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002, 46, 365–369. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klumpp J.; Loessner M. J. Detection of Bacteria with Bioluminescent Reporter Bacteriophage. Adv. Biochem. Eng./Biotechnol. 2014, 144, 155–171. 10.1007/978-3-662-43385-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.; Kim M.; Ryu S. Development of an Engineered Bioluminescent Reporter Phage for the Sensitive Detection of Viable Salmonella Typhimurium. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 5858–5864. 10.1021/ac500645c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Merwe R. G.; van Helden P. D.; Warren R. M.; Sampson S. L.; Gey van Pittius N. C. Phage-Based Detection of Bacterial Pathogens. Analyst 2014, 139, 2617–2626. 10.1039/C4AN00208C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. H.; Chen J. H.; Nugen S. R. Electrochemical Detection of Escherichia coli from Aqueous Samples Using Engineered Phages. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 1650–1657. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. N.; Huang T. T.; Yang L. L.; Pan J. B.; Zhu S. B.; Yan X. M. Sensitive and Selective Bacterial Detection Using Tetracysteine-Tagged Phages in Conjunction with Biarsenical Dye. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 5873–5877. 10.1002/anie.201100334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. N.; Song Y. Y.; Luan T.; Ma L.; Su L. Q.; Wang S.; Yan X. M. Specific Detection of Live Escherichia coli O157:H7 using Tetracysteine-Tagged PP01 Bacteriophage. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 86, 102–108. 10.1016/j.bios.2016.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza G. R.; Christianson D. R.; Staquicini F. I.; Ozawa M. G.; Snyder E. Y.; Sidman R. L.; Miller J. H.; Arap W.; Pasqualini R. Networks of Gold Nanoparticles and Bacteriophage as Biological Sensors and Cell-Targeting Agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 1215–1220. 10.1073/pnas.0509739103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawil N.; Sacher E.; Mandeville R.; Meunier M. Surface Plasmon Resonance Detection of E. coli and Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus Using Bacteriophages. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 37, 24–29. 10.1016/j.bios.2012.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai-Prochnow A.; Hui J. G. K.; Kjelleberg S.; Rakonjac J.; McDougald D.; Rice S. A. Big Things in Small Packages: the Genetics of Filamentous Phage and Effects on Fitness of their Host. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 39, 465–487. 10.1093/femsre/fuu007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson F.; Borrebaeck C. A. K.; Nilsson N.; Malmborg-Hager A. C. The Mechanism of Bacterial Infection by Filamentous Phages Involves Molecular Interactions Between TolA and Phage Protein 3 Domains. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 2628–2634. 10.1128/JB.185.8.2628-2634.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilpern A. J.; Waldor M. K. CTX phi Infection of Vibrio cholerae Requires the tolQRA Gene Products. J. .Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 1739–1747. 10.1128/JB.182.6.1739-1747.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N. T.; Liu T. J.; Lee T. C.; You B. Y.; Yang M. H.; Wen F. S.; Tseng Y. H. The Adsorption Protein Genes of Xanthomonas campestris Filamentous Phages Determining Host Specificity. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 2465–2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clackson T.; Lowman H. B.. Phage Display: A Practical Approach; OUP Oxford: Oxford, England, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. K.; Cao B. R.; Mao C. B. Bacteriophage Bundles with Prealigned Ca2+ Initiate the Oriented Nucleation and Growth of Hydroxylapatite. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 3630–3636. 10.1021/cm902727s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandra N.; Abbineni G.; Qu X. W.; Huai Y. Y.; Wang L.; Mao C. B. Bacteriophage Bionanowire as a Carrier for Both Cancer-Targeting Peptides and Photosensitizers and Its Use in Selective Cancer Cell Killing by Photodynamic Therapy. Small 2013, 9, 215–221. 10.1002/smll.201202090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K.; Chen Y.; Li S. Q.; Nguyen H. G.; Niu Z. W.; You S. J.; Mello C. M.; Lu X. B.; Wang Q. A. Chemical Modification of M13 Bacteriophage and Its Application in Cancer Cell Imaging. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010, 21, 1369–1377. 10.1021/bc900405q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freese P. D.; Korolev K. S.; Jimenez J. I.; Chen I. A. Genetic Drift Suppresses Bacterial Conjugation in Spatially Structured Populations. Biophys. J. 2014, 106, 944–954. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feick J. D.; Velegol D. Electrophoresis of Spheroidal Particles Having a Random Distribution of Zeta Potential. Langmuir 2000, 16, 10315–10321. 10.1021/la001031a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaro R. F.; Briggs M. P.; Carey C. L.; Ketchum B. H. Viability of Escherichia coli in Sea Water. Am. J. Public Health Nations Health 1950, 40, 1257–1266. 10.2105/AJPH.40.10.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanes N. B.; Fragala R. Effect of Seawater Concentration on Survival of Indicator Bacteria. J. Water Pollut. Control. Fed. 1967, 39, 97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies C. M.; Evison L. M. Sunlight and the Survival of Enteric Bacteria in Natural Waters. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1991, 70, 265–74. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb02935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig D. L.; Fallowfield H. J.; Cromar N. J. Use of Microcosms to Determine Persistence of Escherichia coli in Recreational Coastal Water and Sediment and Validation with in Situ Measurements. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 96, 922–930. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch S. A.; Mullen A. M.; O’Neill E. E.; Garcia C. A. Harnessing the Potential of Blood Proteins as Functional Ingredients: A Review of the State of the Art in Blood Processing. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 330–344. 10.1111/1541-4337.12254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrack J. R.; Hoch H. Serum Proteins - a Review. J. Clin. Pathol. 1949, 2, 161–192. 10.1136/jcp.2.3.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilpern A. J.; Waldor M. K. pIII(CTX), a Predicted CTX phi Minor Coat Protein, can Expand the Host Range of Coliphage fd to Include Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 1037–1044. 10.1128/JB.185.3.1037-1044.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz S. H.; Jakob R. P.; Weininger U.; Balbach J.; Dobbek H.; Schmid F. X. The Filamentous Phages fd and If1 Use Different Mechanisms to Infect Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 405, 989–1003. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland S. J.; Sanz C.; Perham R. N. Identification and Specificity of Pilus Adsorption Proteins of Filamentous Bacteriophages Infecting Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Virology 2006, 345, 540–548. 10.1016/j.virol.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borase H. P.; Patil C. D.; Salunkhe R. B.; Suryawanshi R. K.; Salunke B. K.; Patil S. V. Biofunctionalized Silver Nanoparticles as a Novel Colorimetric Probe for Melamine Detection in Raw Milk. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2015, 62, 652–662. 10.1002/bab.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernousova S.; Epple M. Silver as Antibacterial Agent: Ion, Nanoparticle, and Metal. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 1636–1653. 10.1002/anie.201205923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhamla M. S.; Benson B.; Chai C.; Katsikis G.; Johri A.; Prakash M. Hand-Powered Ultralow-Cost Paper Centrifuge. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 0009. 10.1038/s41551-016-0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smartt A. E.; Ripp S. Bacteriophage Reporter Technology for Sensing and Detecting Microbial Targets. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 400, 991–1007. 10.1007/s00216-010-4561-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smartt A. E.; Xu T. T.; Jegier P.; Carswell J. J.; Blount S. A.; Sayler G. S.; Ripp S. Pathogen Detection using Engineered Bacteriophages. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 402, 3127–3146. 10.1007/s00216-011-5555-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield D. A.; Sharp N. J.; Westwater C. Phage-Based Platforms for the Clinical Detection of Human Bacterial Pathogens. Bacteriophage 2012, 2, 105–283. 10.4161/bact.19274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou X. D.; Zhang G. H.; Herrera I.; Kinach R.; Ornatsky O.; Baranov V.; Nitz M.; Winnik M. A. Polymer-Based Elemental Tags for Sensitive Bioassays. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 6111–6114. 10.1002/anie.200700796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tram K.; Kanda P.; Salena B. J.; Huan S. Y.; Li Y. F. Translating Bacterial Detection by DNAzymes into a Litmus Test. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 12799–12802. 10.1002/anie.201407021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. Y.; Zhou Y. F.; Jiang X. X.; Sun B.; Zhu Y.; Wang H.; Su Y. Y.; He Y. Simultaneous Capture, Detection, and Inactivation of Bacteria as Enabled by a Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Multifunctional Chip. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 5132–5136. 10.1002/anie.201412294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda O. R.; Li X. N.; Garcia-Gonzalez L.; Zhu Z. J.; Yan B.; Bunz U. H. F.; Rotello V. M. Colorimetric Bacteria Sensing Using a Supramolecular Enzyme-Nanoparticle Biosensor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 9650–9653. 10.1021/ja2021729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellman G. L. Tissue Sulfhydryl Groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1959, 82, 70–77. 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J. J.; Le Saux G.; Gao J.; Buffeteau T.; Battie Y.; Barois P.; Ponsinet V.; Delville M. H.; Ersen O.; Pouget E.; Oda R. GoldHelix: Gold Nanoparticles Forming 3D Helical Superstructures with Controlled Morphology and Strong Chiroptical Property. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 3806–3818. 10.1021/acsnano.6b08723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez R. M.; Megli C. J.; Taylor R. K. Growth and Laboratory Maintenance of Vibrio cholerae. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2010, 17, 6A.1.1. 10.1002/9780471729259.mc06a01s17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. J.; Chung S. G.; Lee S. H.; Choi J. W. Relation of Microbial Biomass to Counting Units for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2012, 6, 4620–4622. 10.5897/AJMR10.902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Li R. F.; Ming Z. H.; Lu G. T.; Tang J. L. Identification of a Novel Type III Secretion-Associated Outer Membrane-Bound Protein from Xanthomonas campestris pv. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42724. 10.1038/srep42724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz A. H.; Kovacs I.; Lindermayr C. Inducible Expression of the De-Novo Designed Antimicrobial Peptide SP1–1 in Tomato Confers Resistance to Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0164097. 10.1371/journal.pone.0164097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.