Abstract

Background:

Being a fatal and 100% preventable disease, all efforts must be made by the health system to prevent even a single case of rabies. By assessing the knowledge of people regarding rabies prevention, we can make plans and policies for its prevention. The aim of this study was to assess the knowledge regarding rabies among attendees of anti-rabies clinic of a teaching hospital, Jaipur.

Methods:

This observational cross-sectional study was conducted among attendees of anti-rabies clinic, Govt. R.D.B.P. Jaipuria hospital, Jaipur from February 2018 to July 2018. A total of 107 participants were included in the study. Data was collected using preformed questionnaire. Continuous data were expressed in mean and standard deviation and count data were expressed in proportion.

Results:

In our study population, only 22.5% respondents had good knowledge, 56% had fair, and 21.5% had poor knowledge. Fatality of rabies was known to 68.2% of participants. One fourth of the participants knew that rabies is not curable, however, approximately 83% knew that it is preventable. Fifty-six percent of the participants were aware about washing the bite wound with soap and water. Approximately one-third (36%) of the participants knew that it is an infectious disease, however, only 7.5% knew that saliva, vomitus, tear, and urine of rabies patient may have rabies virus. Approximately 15% of the attendees had a wrong concept that a single injection is sufficient for immunization.

Conclusion:

Although this study was done at a teaching hospital, lack of knowledge is still a big issue in urban population as well. This study concludes that knowledge regarding rabies should be highlighted in national programs of India to acknowledge Indian population regarding fatal rabies.

Keywords: Animal bite, anti-rabies clinic, dog bite, rabies

Introduction

Rabies is a highly fatal still completely preventable acute viral disease of the central nervous system that causes fatal encephalomyelitis in virtually all warm-blooded animals including humans.[1] The causative agent belongs to the genus Lyssavirus of the family Rhabdoviridae.[2] It is endemic throughout the country, except Andaman and Nicobar and Lakshadweep Islands.[3] Rabies is classified under the neglected tropical and zoonotic diseases. Many myths and cultural rituals still persist without any logic and appropriate knowledge regarding rabies. Many myths are prevalent in the community for wound management of animal bite, such as application of red chilli, lime, and herbs, instead of washing the wound with soap and water. This situation is rooted in the lack of awareness regarding preventive measures of rabies and proper post-exposure prophylaxis. Insufficient dog vaccination, an uncontrolled canine population, and an irregular supply of anti-rabies vaccine and immunoglobulin, particularly in primary healthcare facilities of rural India are also responsible for the same. Our study focused on community awareness regarding rabies and its prevention. Study of knowledge regarding rabies vaccine and vaccination is needed because at referral/teaching-level institute it (anti-rabies serum) is available but is not freely available at all primary health centres and community health centres (PHCs/CHCs) and even at district-level hospitals. In India or other developing countries where health and hygiene are the major concern of government policies, these kinds of studies can contribute significantly. Along with the knowledge of complete course of four doses of intradermal anti-rabies vaccine (ARV) on bilateral deltoid, anti-rabies serum (in category 3 bite), and wound management including tetanus toxoid and immediate washing of wound with soap and water for a minimum of 15 min can save many lives from fatal rabies. For successfully implementing this, there should be availability and consistent supply of anti-rabies vaccine and anti-rabies serum at health centres and community awareness about seeking medical care, and important preventive measures need to be practiced immediately after bite. Awareness regarding the disease and its preventive measures can play a vital role in decreasing rabies-related morbidity and mortality. Approximately 65,000 people across the globe and 20,000 people in India die of rabies every year, making India the country with the highest rabies fatalities in Asia and the second highest in the world.[4] It is estimated that the number of deaths due to rabies may be 10 times more than that reported.[5] India spends approximately 15 billion INR for rabies vaccines alone, exerting a sizeable economic burden on the government.[6] Deaths caused by rabies could be prevented by timely application of appropriate prophylaxis.[7]

This study was conducted at the anti-rabies clinic of R.D.B.P. Jaipuria hospital, associated with RUHS medical college, Jaipur, to assess the knowledge of attendees of anti-rabies clinic regarding rabies.

Methods

This observational cross-sectional study was conducted at an anti-rabies clinic at Govt. R.D.B.P. Jaipuria hospital, associated with RUHS medical college, Jaipur, between February and July 2018. Sample size was calculated to be 100, assuming 50% knowledge among animal bite victims considering maximum variance and relative allowable error of 20% using the formula of 4PQ/l2. All attendees of the anti-rabies clinic were given a preformed questionnaire, and those who gave consent and filled the form were enrolled for study.

Exclusion criteria:

<15-year-old attendants,

Those who did not give consent

Follow-up visitors (repeat visitors).

Data was collected using a predesigned semi-structured questionnaire at the time of first visit to the clinic. Data thus collected were entered in Microsoft Excel software and analyzed using IBM SPSS version 20.0 statistical software. Continuous data were expressed as mean and standard deviation, and count data were expressed as proportion. A structured questionnaire containing a total of 13 questions regarding rabies knowledge was prepared; socio-demographic variable data were also included in the questionnaire. Scoring was done as 1 for each right answer and 0 for a wrong answer or unanswered question. For knowledge, score 0–4 was poor, 5–8 was fair, and 9–13 was good knowledge.

Results

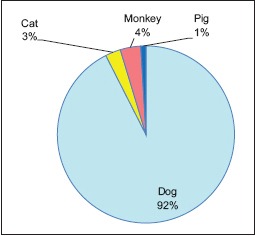

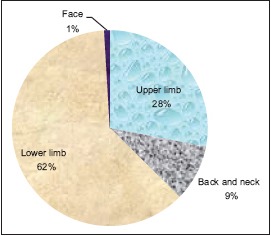

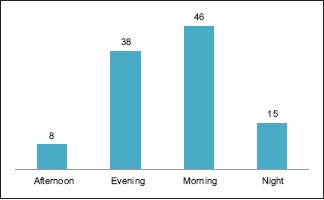

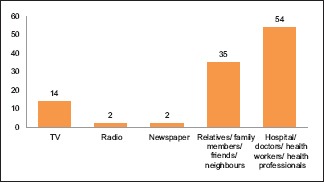

We enrolled 107 participants in our study including 72% males and 28% females. Maximum participants were from the age group of 26–35 years (43%), urban area (72%), and studying in 10th standard (22.5%) [Table 1]. Most participants were victims of dog bite (92.5%) [Graph 1]. Out of 99 cases of dog bite, 69% were bitten by street dogs and 31% were bitten by pet dogs. The most common site of bite was lower limb (62%) followed by upper limb (28%), back and neck (9%), and face (1%) [Graph 2]. Maximum bites were of category 2 (73.8%) with unprovoked bite (64.5%). In out study, maximum bite incidences occurred in the morning (43%) followed by evening (35.5%), night (14%), and the lowest in the afternoon (7.5%) [Graph 3]. Out of 107 participants, 17 (15.9%) had a past history of antirabies vaccination (ARV) vaccination in their life and 89 (83.1%) had no past history of ARV vaccination and 1 (1%) participant did not know the status of past vaccination. First source of information about rabies for most participants (50.5%) was hospital/doctors/health workers/health professionals, followed by family, friends, and relatives (32.7%), television (13%), and radio and newspaper contributing the lowest at 1.9% each [Graph 4].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile of attendees of anti-rabies clinic

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | ||

| 15-25 | 38 | 35.51 |

| 26-35 | 46 | 42.99 |

| 36-45 | 15 | 14.02 |

| 46-55 | 6 | 5.61 |

| >55 | 2 | 1.87 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 77 | 71.96 |

| Female | 30 | 28.04 |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 12 | 11.22 |

| 5th | 4 | 3.74 |

| 8th | 20 | 18.7 |

| 10th | 24 | 22.42 |

| 12th | 14 | 13.1 |

| Graduate | 22 | 20.55 |

| Postgraduate and above | 11 | 10.27 |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 30 | 28.04 |

| Urban | 77 | 71.96 |

| Total | 107 | 100 |

Graph 1.

Type of animal bite

Graph 2.

Distribution of participants according to the site of bite

Graph 3.

Distribution of participants according to the time of bite

Graph 4.

Distribution of participants according to the first source of information

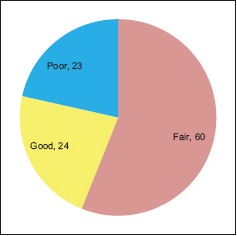

Only 22.5% participants had good knowledge. Fifty-six percent had fair knowledge, and only 21.5% participants had poor knowledge [Graph 5]. Approximately half of the participants knew the name of the disease caused by a rabid animal. More than 90% of the participants were aware of the fact that it is caused by the bite of a rabid dog. The fact that rabies can also be caused by the bite of monkey or cat or camel was known to 39% of the participants. Only one-third (35.5%) of the participants were aware about fear from water in rabies. Fatality of rabies was known to approximately two-third of the participants (68.2%). One-fourth of the participants knew that rabies is not curable, but approximately 83% knew that it is preventable and 80% knew that it can be prevented by vaccination. Fifty-six percent of the participants were aware about washing the bite wound with soap and water. Approximately one-third (36%) of the participants knew that it is an infectious disease, but only 7.5% knew that saliva, vomitus, tear, and urine of rabies patient may have rabies virus. Correct period of observation of biting dog was known to almost half (53.3%) of the participants. Approximately 15% of the attendees had a wrong notion that a single injection is sufficient for immunization [Table 2].

Graph 5.

Distribution of participants according to knowledge score

Table 2.

Knowledge about rabies/animal bite

| S.N. | Question | Correct answer number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Name of disease caused by bite of rabid animal | 54 | 50.47 |

| 2. | Rabies disease is caused by bite of rabid dog | 98 | 91.59 |

| 3. | Rabies can also occur by bite of cat or camel or monkey bite | 42 | 39.25 |

| 4. | Fear from water may be present in rabies | 38 | 35.51 |

| 5. | Is rabies fatal? | 73 | 68.22 |

| 6. | Is rabies curable? | 27 | 25.23 |

| 7. | Is rabies preventable? | 88 | 82.24 |

| 8. | Rabies can be prevented by vaccination | 85 | 79.44 |

| 9. | Washing bite wound with soap and water | 60 | 56.07 |

| 10. | Is rabies an infectious disease? | 39 | 36.45 |

| 11. | Saliva, vomitus, tear, and urine of rabies patient may have virus of rabies | 8 | 7.48 |

| 12. | Period of observation of biting dog | 57 | 53.27 |

| 13. | Is there any vaccine which can completely protect against rabies with only one dose? | 47 | 43.93 |

Discussion

Our study included 72% males similar to the studies of Ganasva et al. (71.7%),[8] Acharya et al. (76.4%),[9] Jain et al. (72%),[10] Chandan et al. (85%),[11] Tripathy (72.5%).[12] In our study, maximum participants were from an urban area (72%), whereas maximum population was from a rural area (87.5%) in the study by Tripathy.[12] Maximum participants were studying in 10th standard (22.5%), and 11.22% of the participants were illiterate in our study; whereas 52.5% of the participants had studied up to primary school and 33.75% were illiterate in the study by Tripathy.[12] Maximum bites were of category 2 (73.8%) in our study, whereas in the study by Agarvval,[13] 48% were class II bites. The most common site of bite was lower limb (62%) in our study, whereas the site of bite was legs only in 72% in Agarvval's study.[13] Approximately equal number of bites were caused by pet and street dogs in the study by Agarvval,[13] whereas in our study 69% were bitten by street dogs and 31% were bitten by pet dogs. In our study, maximum bite incidences occurred in the morning (43%) followed by evening (35.5%), night (14%), and the lowest in afternoon (7.5%), whereas no significant difference in bites occurring at different times of the day was observed in the study by Agarvval.[13]

In our study, the most common source of information was hospital/doctors/health workers/health professionals (50.5%), whereas it was mass media (television/radio/newspaper) and family members in the study by Herbert.[14] A total of 74.1% (137) were aware of rabies in the study by Herbert,[14] whereas in our study approximately half of the participants knew the name of the disease caused by the rabid animal. Eighty-four of the participants were familiar with the disease in the study by Tripathy.[12] More than 90% of the participants were aware of the fact that it is caused by the bite of a rabid dog in our study, whereas in that of Herbert study 67% understood that dogs are responsible for transmitting rabies.[14] Approximately 98% participants knew that dog was the source of infection in the study by Tripathy.[12] Only 10.11% knew other animals as the source of infection in the study by Tripathy,[12] while in our study 39% participants knew the same. Fatality of rabies was known to almost two-third of the participants (68.2%) in our study, while this figure was 54.1% Herbert's study[14] and 84% in Agarvval's study.[13]

Washing of wound with soap and water immediately for a minimum of 15 min is an important preventive aspect of rabies prevention as it helps in removing rabies viruses from the wound area. In our study, 56% of the participants were aware about washing the bite wound with soap and water. Similar results were obtained in Herbert's study[14] where approximately one-half of the residents were not aware about washing the wound from an animal bite with water.

Fear of water was known to 1% of the participants in the study by Chandan et al.,[11] 12% in the study by Singh,[15] and 35.5% participants in our study. Awareness about the rabies vaccine was reported by 42.7% of the participants in Herbert's study[14] and 80% in our study. Approximately half of the participants (51%) had a good knowledge score, and 196 (49%) had poor knowledge score according to Chandan et al.[11] Among 400 study participants, 137 (34.25%) had good knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP), whereas 263 (65.75%) had poor KAP in the study by Tripathy.[12] Only 22.5% participants had good knowledge. In our study, 56% percent had fair knowledge and 21.5% participants had poor knowledge.

Conclusion

Incidence of rabies in India has been constant for the last few years, without any declining trend. The reported incidence is probably an underestimation of the true incidence because in India rabies is still not a notifiable disease. Public education campaigns need to be conducted to make people aware of rabies, especially in remote areas, and of the vital importance of seeking medical care immediately after an animal bite. Good knowledge regarding rabies will be definitely helpful in rapid and effective efforts to eliminate this fatal disease.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.National Guidelines on Rabies Prophylaxis. National Centre for Disease Control (Directorate General of Health Services) 22-Sham Nath Marg, Delhi - 110 054. 2015. [Last assessed on 2018 May 10]. Available from: http://www.ncdc.gov.in .

- 2.Expert consultation on rabies second report: WHO Technical Report Series 982. Geneva: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Last assessed on 2018 May 04]. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/world-rabies-day,-2017_pg .

- 4.World Health Organization. Assessing burden of rabies in India. Association for Prevention and Control of Rabies in India (APCRI) 2011. [Last accessed on 2018 May 16]. Available from: http://rabies.org.in/rabies/wp-content/uploads/2011/whosurvey.pdf .

- 5.Park K. 18th ed. Jabalpur: M/S Banarsidas Bhanot Publishers; 2005. Epidemiology of communicable diseases. Park's Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine; p. 146. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meslin FX. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. [Last accessed on 2018 Apr 15]. Appraisal on implementation of intradermal rabies vaccination in India - The Kerala experience. Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) Available from: http://www.rabiesinasia.org/keralareport.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO regional office for South East Asia. Frequently asked questions on rabies. [Last accessed on 2018 May 15]. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/

- 8.Ganasva A, Bariya B, Modi M, Shringarpure K. Perceptions and treatment seeking behaviour of dog bite patients attending regional tertiary care hospital of central Gujarat, India. J Res Med Den Sci. 2015;3:60–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acharya R, Sethia R, Sharma G, Meena P. An analysis of animal bite cases attending anti-rabies clinic attached to tertiary care centre, Bikaner, Rajasthan, India. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2016;3:1945–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain P, Jain G. Study of general awareness, attitude, behavior, and practice study on dog bites and its management in the context of prevention of rabies among the victims of dog bite attending the OPD services of CHC muradnagar. J Fam Med Primary Care. 2014;3:355–8. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.148107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandan N, Kotrabasappa K. Awareness of animal bite and rabies among agricultural workers in rural Dharwad, Karnataka, India. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2016;3:1851–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tripathy RM, Satapathy SP, Karmee N. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice regarding rabies and its prevention among construction workers: A cross-sectional study in Berhampur, Odisha. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017;5:3970–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarvval N, Reddaiah VP. Knowledge, attitude and practice following dog bite: A community-based epidemiological study. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 2003;26:154–61. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herbert M, Riyaz Basha S, Thangaraj S. Community perception regarding rabies prevention and stray dog control in urban slums in India. J Infect Public Health. 2012;5:374–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh US, Choudhary SK. Knowledge, attitude, behavior and practice study on dog-bites and its management in the context of prevention of rabies in a rural community of Gujarat. Indian J Community Med. 2005;30:81–3. [Google Scholar]