Abstract

In primary care settings, cultural perception and competence attitude are imperative as notion of health, illness, sickness, and care means different to different people. The knowledge of cultural beliefs and customs facilitate healthcare providers to afford improved care and helps to avert misunderstandings among care provider's staff, patients, and their families. It is a very useful approach in family practice towards improving the health care to racial/ethnic minor groups and reducing the disparities.

Keywords: Cultural competence, ethic minority, diversity, social determinants of health, family practice, primary care

Introduction

The term liberalization of the global economy has come into existence since 1991 after World Bank's embarkment of new economic policy. It seems to have increased in internal and external migration. As per the estimates of UNDP, 2009, nearly 740 million people are internal migrants who live within their home country but outside their region of birth although these numbers reduce the 232 million international migrants worldwide as per the UNFPA 2015 estimates. Increase in race, ethnic, and cultural diversity within low- and middle-income country makes evident that requirement of cultural competence in the healthcare sector is to call for action.

The need to address cultural competence is being increasing felt the globe as national diversity among the population is steadily rising. Cultural competence always aims to reduce the healthcare disparities and improving the clinical care of the patients. The adverse health outcomes in South Asian countries experienced among racial and ethnic minorities such as higher rates of Tuberculosis, diabetes, and cancer[1] and tend to receive a lower quality of health care.

Involvement of patients and their families in the planning, development, and assessment of the health care is called patient-centered care (PCC). PCC is a key dimension to improve health outcomes.[2] Patients and their family members are part of the care team and have a significant part in decisions at the patient and system level. PCC has effectively proven to bring results on the patient's length of stay in the hospital, and other indicators in improving the efficiency and cost of the care.

As existing literature strongly suggests reducing health and health care disparities is possible through the culturally competent healthcare delivery system. The National Quality Forum defines culturally competent care as the “ongoing capacity of health care systems, organizations, and professionals to provide for diverse patient populations high-quality care that is safe, patient and family-centered, evidence-based, and equitable.”[3] PCC along with culturally competent system would necessarily meet the healthcare needs of diverse populations in family practice.

Understanding of culture and diversity

Basically, culture is defined as learned patterns of thoughts and behavior, which makes particular social group distinguish from others.[4] As early as in 1987, Edward defined Culture as a concept including knowledge, belief, arts, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by human beings as a member of society.[5] There are nearly 160 different definitions representing different groups as mentioned by Kroeber and Kluckhohn.[6,7]

Diversity is generally a broad concept referring to groups or individuals perceived to be group comparing to the general community (Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health, 2003). Culture in relation to diversity, referring cultural diversity, tends to focus on the rights of individuals and groups. UNESCO's Universal Declaration on Cultural diversity as “a source of exchange, innovation, and creativity which are necessary for mankind as biodiversity is for nature” which got adopted in 2001. As per the Department of Human Services, 2006, the term cultural and linguistic diversity refers to a range of different cultures and language groups signified in the population. Communities having nonmainstream cultural or linguistic affiliations by their place of birth, ancestry or ethnic origin, religion, preferred language, or language spoken at home.

Cultural competence

There are continuing efforts to define the cultural competence and its uses within the healthcare contexts. Cultural competence is a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals and enable to work effectively in cross-cultural situations.[8]

Cultural competence can be viewed at an individual level whereby it is the ability to identify and challenge one's cultural assumptions, values, and beliefs.[9] As per the National Health and Medical Research Council, Cultural competence is more than a responsiveness of cultural differences, as it can be used to improve health and well-being by integrating culture into the delivery of health services.

Nowadays, cultural competence slowly gains attention in the healthcare sector emerged as one strategy to address the disparities in healthcare. In relation to healthcare, Leininger in 1978 described the cultural competence who is a pioneer in the field. He proposed cultural competence as a means of addressing culturally-specific health needs. The various definition of cultural competence of healthcare sector has been in existence.[10] But there is no universally accepted definition.

Recent definition for cultural competence in healthcare from constructivist says, “A complex know-act grounded in critical reflection and action, which the healthcare professional draws upon to provide culturally safe, congruent, and effective care in partnership with individuals, families, and communities living health experiences, and which considers the social and political dimensions of care”.[11] Although the definition from Cross et al. is widely accepted across the globe.

Continuing Learning Process

Health professionals thinking to address global health issues must have cultural competence to recommend feasible solutions for the intended population. The dynamic attribute of culture remains another substantial reason to follow cultural competence in the healthcare sector. As communities evolve, culture constantly changes in accordance with it.[12] As a result, the development of cultural competence must be a continuous learning process.

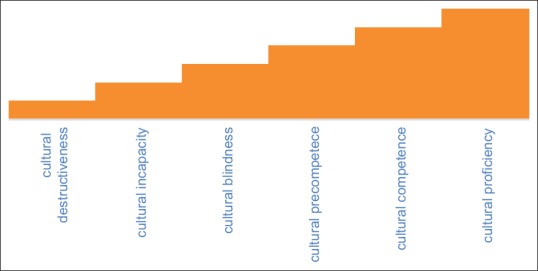

There are different stages of cultural competence are explained in an organization [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Stages of cultural competence

Stage 1: Cultural destructiveness at organizational level

Healthcare institutions instead of making treatment programs that provide culturally congruent services, they expect people belonging to different ethnic and cultural backgrounds to adapt the existing treatment program services. The relevance of behavioral health services gets nullified when healthcare institutions fail to create comfortable environment and is unable to provide basic services.

Stage 2: Cultural incapacity organizational level

Because of the dearth of the healthcare institutional responsiveness, services, the culture of the provider may be biased, and patients and their caregivers may find it onerous. The healthcare provider at cultural incapacity becomes inflexible and fails to adapt to the patients and their caregivers needs. Due to varied population, active participation of people in planning of treatment decreases the need for culturally congruent treatment services. Counsellors also neglect the importance of culture as they frame culturagram by opting for dominant culture people.

Stage 3: Cultural blindness organizational level

Assumption for cultural blindness that all cultural groups are same and share identical experiences makes healthcare providers to rationalize the treatment services that will suffice all patients. Thus, organization will keep on implementing policies and procedures that will inseminate discrimination.

Stage 4: Cultural pre-competence organizational level

As the hospital/organization recognizes the need for more culturally responsive services, convenient services for culturally diverse population can be established with the support and planning from the governing and advisory boards, community, and administrators.

Stage 5: Cultural competence and proficiency organizational level

A strategic plan is needed by healthcare institution to conduct self-assessment for adopting cultural competence plan which can help in integrating services that are compatible with diverse populations. Proficiency includes training, evaluation, and development of culturally congruent services.

Many causes including low socioeconomic status, language barriers or limited English proficiency, education, and cultural beliefs would cause health disparities.[13,14,15,16] These may have a negative impact on the utilization, adherence to healthcare services, satisfaction, and healthcare expenditures.[17] For addressing the disparities along with improving the minority health, government organizations, hospitals, and public health organizations, and personnel must work together.[1] Still, it is remaining a debated topic whether cultural competence help in healthcare disparities as there is not enough evidence to prove the facts.[18,19]

Factors influencing the cultural competence

Lack of uptake of policy frameworks: There is a lack of funding and service agreements to incorporate into the public health system, though the government has recognized the need to develop the cultural competency guidelines. As no steps were taken from government level, the decision to embrace the developed guidelines left to the discretion of the practitioner. There exists evidence that suggests that health promotion programs involving coalitions may have had limited impact on community health status.[20] Health programs as general do not include the cultural competence as a tool for improving the healthcare disparities.[21]

Though other countries have proven the cultural competence is an effective way to reduce the healthcare disparities, India, is still in process of accepting it. Many studies in India rely on self-report, which is subject to a range of biases, while objective evidence of intervention effectiveness was rare.[22]

Lack of evidence base: Although some studies have done in this area, there remain many gaps in the evidence base. Conventional research frequently excludes consideration of culturally and linguistically diverse background people due to perceived methodological difficulties and costs.[22]

Inconsistent practice: Data entry level from people does not follow a consistent method in people's background perspective. However, there is enough evidence to suggest that some ethnic minority group poorer access to services, poorer quality, and often delayed access until diseases and symptoms are well established.[23] Without organizational support, it is not feasible to design and implement a wide spectrum of cultural competent training activities for universal practice that improves the consistent practice across the place.[19]

Insufficient Resources: Increased time and resources required to culturally competent research need to be accounted for the researchers and public health practitioners in program and research budgets. Lack of tools to measure the cultural competency would be one of the factors responsible for the lack of organized researches conducted.[24,25]

Lack of community participation: System-level hinderance to community involvement include lack of work at the grassroots level and lack of investment in community capacity building. Community involvement is very important for any change at the program level. The evidence from the past 20 years suggests that many community-based programs have had an only modest impact due to a number of reasons including lack of community participation.[20,26]

Future Scope of cultural competence

Individual healthcare provider, public health researcher, family medicine or health promotion practitioner, professional associations and academic journals, and organizational and systemic factors should act as a positive factor for influencing the cultural competence in healthcare by developing common practices and system to be followed for the cultural competence, which directly influences the policy level changes.

Cultural competence in health is always an important approach and concept to design, delivery, and evaluation of the public health system and policies, programs, and action. The shift toward achieving cultural competence in family practice and public health framework is likely to reveal new ideas about intransigent factors contributing to health inequalities and innovative strategies for health promotion and public health. With increasing population diverse globally, cultural competence will become the hallmark of high-quality public health systems, programs, and research; more specifically in the area of family medicine and primary care.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cultural Competence in Health Care: Is it important for people with chronic conditions? [Online] [Last accessed on 2018 Sep 28]. Available from: https://hpi.georgetown.edu/agingsociety/pubhtml/cultural/cultural.html .

- 2.Delaney Patient-centred care as an approach to improving health care in Australia. Collegian. 2018;25:119–23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleckman, Dal Corso M, Ramirez S, Begalieva M. Johnson Intercultural competency in public health: A call for action to incorporate training into public health education. Front Public Health. 2015;3:210. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson, Scrimshaw, Fullilove, Fielding, Normand J. Culturally competent healthcare systems. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:68–79. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Felluga. Peter Melville Logan, “On Culture: Edward B. Tylor's Primitive Culture, 1871” | BRANCH [Internet] [cited 2019 Jan 18]. Available from: http://www.branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=peter-logan-on-culture-edward-b-tylorsprimitive-culture-1871 .

- 6.Peterson Revitalizing the culture concept. Annu Rev Sociol. 1979;5:137–66. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrew Weil. Wikipedia [Internet] 2018. [Last cited on 2019 Jan 18]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Andrew_Weil&oldid=874836305 . [Google Scholar]

- 8.NCJRS Abstract-National Criminal Justice Reference Service. [Online] [Last accessed on 2018 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=124939 .

- 9.Flores G. Culture and the patient-physician relationship: Achieving cultural competency in health care. J Pediatr. 2000;136:14–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(00)90043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Betancourt, Green, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O. Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:293–302. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garneau, Pepin J. Cultural competence: A constructivist definition. J Transcult Nurs. 2015;26:9–15. doi: 10.1177/1043659614541294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinman A, Benson P. Anthropology in the clinic: The problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PLOS Med. 2006;3:e294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care [Internet] Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2003. [Last cited on 2019 Jan 18]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220358/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasu, Bawa, Suminski R, Snella K, Warady B. Health literacy impact on national healthcare utilization and expenditure. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4:747–55. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson The crucial link between literacy and health. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:875. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adult Literacy in America: A First Look at the Findings of the National Adult Literacy Survey. 30-Aug-1993. [Online] [Last accessed on 2018 Sep 28]. Available from: https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=93275 .

- 17.Brach C, Fraser I. Reducing disparities through culturally competent health care: An analysis of the business case. Qual Manag Health Care. 2002;10:15–28. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200210040-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drevdahl, Canales Dorcy Of goldfish tanks and moonlight tricks: Can cultural competency ameliorate health disparities? ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2008;31:13–27. doi: 10.1097/01.ANS.0000311526.27823.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vega Higher stakes ahead for cultural competence. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:446–50. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merzel C, D’Afflitti J. Reconsidering community-based health promotion: Promise, performance, and potential. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:557–74. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charan, Paramita S. Health programs in a developing country-why do we fail? Health Syst Policy Res. 2016;3:3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Truong M, Paradies Y, Priest N. Interventions to improve cultural competency in healthcare: A systematic review of reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:99. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Academies Press (US); 2003. I. of M. (US) C. on U. and E. R. and E. D. in Care H, Smedley , Stith , Nelson Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Diagnosis and Treatment: A Review of the Evidence and a Consideration of Causes. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson J, Dunn K. Neoliberal anti-racism: Responding to ‘everywhere but different’ racism. Progress in Human Geography. 2017;41:26–43. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gozu A, Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, Robinson K, Palacio A, et al. Self-administered instruments to measure cultural competence of health professionals: A systematic review. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19:180–90. doi: 10.1080/10401330701333654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cyril S, Smith, Possamai-Inesedy A. Renzaho Exploring the role of community engagement in improving the health of disadvantaged populations: A systematic review. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:29842. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.29842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]