Abstract

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the heaviest malignant burdens in China. Molecular targeting agent, sorafenib, is the main therapeutic option for antitumor therapy of advanced HCC, but it is currently too expensive for the public and its therapeutic effect does not satisfy initial expectation. Therefore, it is important to develop more effective molecular targeted therapeutic strategies for advanced HCC.

Materials and methods

The antitumor effects of sorafenib or ARQ-197, an antagonist of c-MET (tyrosine-protein kinase Met or hepatocyte growth factor receptor), were examined by MTT or in murine tumor model. The effect of ARQ-197 on epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) or multidrug resistance (MDR) was examined by quantitative real-time PCR for the expression of related genes. The clearance of sorafenib in HCC cells was detected by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry.

Results

ARQ-197 treatment enhanced the sensitivity of HCC cells to sorafenib. Mechanistic studies indicated that ARQ-197 inhibited the expression of EMT- and MDR-related genes. Moreover, ARQ-197 treatment decelerated the clearance of sorafenib in cultured HCC cells and subcutaneous HCC tumors in nude mice.

Conclusion

In the present work, our data suggested that ARQ-197 decelerated the clearance of sorafenib in HCC cells and enhanced the antitumor effect of sorafenib.

Keywords: advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, molecular targeted agents, ARQ-197 and sorafenib, drug clearance, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, multidrug resistance

Introduction

In China, viral hepatitis (infection by hepatitis B or hepatitis C) has a high morbidity and >80 million people suffer from hepatitis-related chronic liver diseases.1–5 Despite the progress made in the current prevention approaches of hepatitis, patients suffering from chronic liver diseases have a sky-high chance of developing into hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).6–8 Unfortunately, due to the poor clinical diagnosis technology, most patients with HCC are not diagnosed until the disease develops into advanced stage, when radical treatments such as surgical resection and liver transplantation are not useful.6–8 Currently, molecular targeted agent sorafenib is the first-class anticancer drug used for advanced HCC treatment.9,10 Although global multicenter clinical trials, such as the Oriental trial and the SHARP trial,11,12 have demonstrated that sorafenib treatment could prolong patient survival, there are many shortcomings of the clinical application of sorafenib: 1) only a low proportion of patients are sensitive to sorafenib and can be benefited from the treatment;11,12 2) for patients who are initially sensitive to sorafenib, drug resistance may occur as treatment progresses;13 and 3) sorafenib is expensive, which puts a huge financial burden on patients. Therefore, it is of great clinical significance to develop new and more effective treatment strategies to improve the anti-tumor effect of sorafenib.

Receptor tyrosine kinase c-MET was initially discovered in human osteosarcoma, and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) is the only known ligand of c-MET.14,15 Recently, multiple evidences have shown that elevated level of c-MET is found in 20%–40% cases of HCC and it is associated with high risk of metastasis and poor prognosis.16–18 HGF regulates hepatic regeneration and hepatocyte apoptosis in normal tissues and promotes the metastasis of HCC cells.19–21 On HCC cells, HGF binds and activates c-MET, further inducing the transduction of c-MET downstream pathways, such as Raf/MEK/ERK and AKT/ETS-1 signaling pathways, and leads to the proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cells.22–24 Thus, based on the roles of c-MET in many such features of tumor cells, we hypothesized that it may participate in multidrug resistance and the clearance of anti-tumor agents. In this study, we used ARQ-197 (also named Tivantinib), a highly selective and non-ATP competitive inhibitor of c-MET for HCC cell treatment, and found that it inhibited the activation of c-MET, promoted apoptosis, and inhibited proliferation and metastasis of HCC cells.25–30 Our results revealed that ARQ-197 decelerated the clearance of sorafenib in cultured HCC cells or subcutaneous HCC tumors in nude mice, and the combination of ARQ-197 and sorafenib could upregulate the antitumor effect of sorafenib on HCC cells.

Materials and methods

Cell line and reagents

L-02 (a nontumor hepatic cell line) HCC cell lines, HepG2 (an HCC cells line), LM-3 (a highly aggressive HCC cell line), MHCC97-H cells (a highly aggressive HCC cell line), Hu7 (an HCC cell line), BEL-7402 (an HCC cell line), MHCC97-L (a lowly aggressive HCC cell line), and SMMC-7721 (an HCC cell line), which were purchased from the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China) or the National Infrastructure of Cell Line Resources, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing, People’s Republic of China), the culture collection centers of the Chinese government, have been described in our previous publication and were maintained under conditions described in our previous work.31–34 ARQ-197 (catalog no. S2753) or sorafenib (catalog no. S7397) was purchased from Selleck Corporation (Houston, TX, USA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich Corporation (St Louis, MO, USA). The usage of cell lines was permitted by the Ethics Committee, the Fifth Medical Center of the PLA General Hospital.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA of HCC cells was extracted by using a PARISTM Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and reverse transcribed by Multiscribe™ Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) agent. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed following the methods described in references.35,36 The level of β-actin mRNA was measured as a loading control. Primers used in qPCR experiments are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used in quantitative real-time PCR experiments

| Targets | Forward/reverse | Sequences of primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| E-cadherin | Forward sequence | GCCTCCTGAAAAGAGAGTGGAAG |

| Reverse sequence | TGGCAGTGTCTCTCCAAATCCG | |

| N-cadherin | Forward sequence | CCTCCAGAGTTTACTGCCATGAC |

| Reverse sequence | GTAGGATCTCCGCCACTGATTC | |

| Vimentin | Forward sequence | AGGCAAAGCAGGAGTCCACTGA |

| Reverse sequence | ATCTGGCGTTCCAGGGACTCAT | |

| MMP-3 | Forward sequence | CACTCACAGACCTGACTCGGTT |

| Reverse sequence | AAGCAGGATCACAGTTGGCTGG | |

| MMP-9 | Forward sequence | GCCACTACTGTGCCTTTGAGTC |

| Reverse sequence | CCCTCAGAGAATCGCCAGTACT | |

| TIMP-1 | Forward sequence | GGAGAGTGTCTGCGGATACTTC |

| Reverse sequence | GCAGGTAGTGATGTGCAAGAGTC | |

| MDR-1 | Forward sequence | GCTGTCAAGGAAGCCAATGCCT |

| Reverse sequence | TGCAATGGCGATCCTCTGCTTC | |

| CYP3A4 | Forward sequence | CCGAGTGGATTTCCTTCAGCTG |

| Reverse sequence | TGCTCGTGGTTTCATAGCCAGC | |

| UGT1A9 | Forward sequence | GCTCTAAAAGCAGTCATCAATGAC |

| Reverse sequence | GTGCCTCATCACAAACTCCACC | |

| β-actin | Forward sequence | CACCATTGGCAATGAGCGGTTC |

| Reverse sequence | AGGTCTTTGCGGATGTCCACGT | |

MTT assay

ARQ-197 or sorafenib was dissolved in DMSO. Then, the drugs were diluted with DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The concentrations of ARQ-197 or sorafenib used are shown in Table 2. HCC cells were treated with indicated concentration of drugs and MTT assay was performed. Inhibition rates and IC50 values were calculated following the methods described in our previous studies.37

Table 2.

Concentrations of agents used in cell survival experiments

| Agents | Concentrations (μmol/L) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| ARQ-197 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1 | 3 | 10 |

| Sorafenib | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1 | 3 | 10 |

Gene reporter luciferase assay

Luciferase reporters EBS-Luc (ETS-1 binding site luciferase reporter), direct repeat 3 (DR3)-Luc (PXR binding site DR3 luciferase reporter), and everted repeat 6 (ER6)-Luc (PXR binding site ER6 luciferase reporter) have been described in our previous work.38,39 HCC cells, which were treated with indicated concentrations of drugs, were harvested to analyze luciferase or β-galactosidase activities following the methods described in references.40,41

Subcutaneous tumor

All methods or protocols of the animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Fifth Medical Center of the PLA General Hospital. All animal studies were performed in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 and associated guidelines. Nude mice (T-cell deficient) mice aged 4–6 weeks were purchased from Si-Bei-Fu Biotechnology Corporation (Beijing, People’s Republic of China). For subcutaneous tumor models,42–44 MHCC97-H cells were injected into nude mice (1×106 cells per animal).

Pharmacokinetic experiments

The sequences and effects of PXR siRNA and ETS-1 siRNA are described in our previous work.38,45 The pharmacokinetic experiments were performed according to the methods provided by Shao et al46 and Wu et al.47 For cell-based experiments, HCC cells were treated with 1 μmol/L sorafenib for 12 hours. Then the cells were harvested at indicated time points. For subcutaneous tumor experiments, HCC cells were injected into nude mice to form subcutaneous tumors. Sorafenib solution was injected into subcutaneous tumors and tissue samples were harvested at indicated time points. The collected samples were extracted by acetonitrile, and the amount of sorafenib sustained in samples was identified by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) following the methods provided by Feng et al47 and Shao et al.46

In vivo antitumor effect of sorafenib

In vivo antitumor effect of sorafenib was examined in a subcutaneous tumor model following the protocols described by Jia et al32 and An et al.48 HCC cells were injected into nude mice (1×106 cells per animal) and 3–4 days after injection, mice received sorafenib (2 mg/kg) treatment. Mice were orally administered sorafenib every 2 days. After 21 days of treatment (ten times treatment), mice were harvested and the volumes or weights of tumor tissues were examined. Inhibition rates of sorafenib on tumor volumes or tumor weight were calculated following the methods described by Jia et al32 and An et al.48

Statistical analysis

All statistical significance analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 statistical software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The IC50 values or half-life time (t1/2) values were calculated by Origin software (Origin 6.1; OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Statistical significance was analyzed by Bonferroni correction with two-way ANOVA, and paired samples were tested by paired-sample t-test (SPSS 16.0 statistical software; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

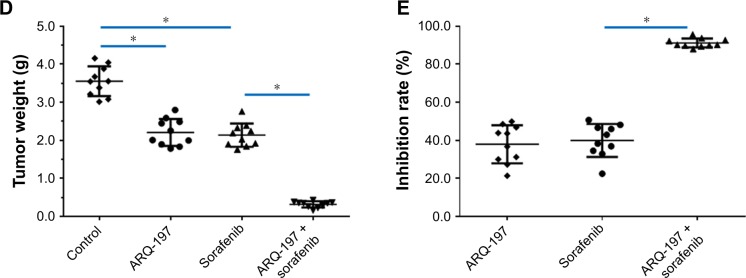

c-MET is highly expressed in aggressive HCC cell lines

First, in order to investigate the role of c-MET in HCC cells, we measured the expression of c-MET in both non-malignant and HCC cell lines using qPCR. As shown in Figure 1, the expression level of c-MET in nontumor L-02 cell line was significantly lower than that in different HCC cell lines. In highly aggressive cell lines MHCC97-H and LM-3, the expression level of c-MET was significantly higher than that in less-aggressive MHCC97-L cells.

Figure 1.

The mRNA level of c-MET in hepatic cells.

Notes: Hepatic cells – L-02, HepG2, LM-3, MHCC97-H, Hu7, BEL-7402, SMMC-7721, or MHCC97-L – were harvested for qPCR experiments.

Abbreviation: qPCR, quantitative real-time PCR.

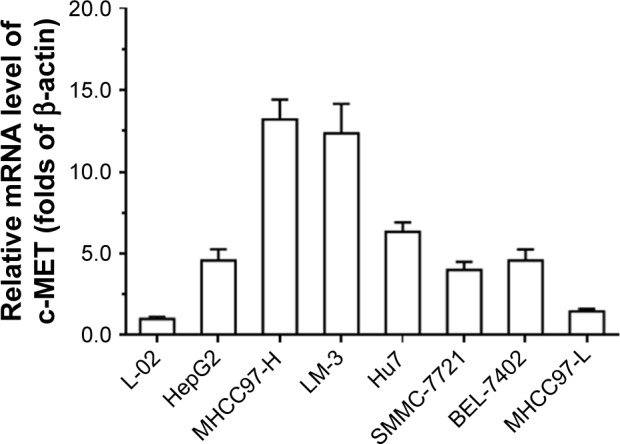

The in vitro antitumor effect of ARQ-197 on HCC cells

Next, the in vitro antitumor effect of ARQ-197 on HCC cells was examined by MTT assay. As shown in Figure 2, ARQ-197 inhibited the survival of MHCC97-H (Figure 2A), LM-3 (Figure 2B), and HepG2 (Figure 2C) cells in a dose-dependent manner. Interestingly, we observed the effect of ARQ-197 was stronger in cells with higher endogenous c-MET expression level. The effective concentration (IC25), half-inhibitory effective concentration (IC50), and maximum action concentration (ICmax) of ARQ-197 on each cell line are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 2.

ARQ-197 inhibits the survival of HCC cells in a dose-dependent manner.

Notes: HCC cells MHCC97-H (A), LM-3 (B), and HepG2 (C), which were treated with indicated concentrations of ARQ-197, were analyzed by MTT experiments. Inhibition rate of ARQ-197 on HCC cells was calculated at OD 490 nm.

Abbreviation: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Table 3.

ARQ-197 inhibits hepatic cells’ survival in a dose-dependent manner

| Cell lines | IC25 values

|

IC50 values

|

ICmax values

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrations (μmol/L) | |||

|

| |||

| L-02 | 3.44±0.24 | 7.59±0.78 | – |

| MHCC97-H | 0.09±0.01 | 0.76±0.22 | 3.56±0.65 |

| LM-3 | 0.08±0.02 | 0.67±0.16 | 4.62±0.80 |

| HepG2 | 0.23±0.07 | 1.99±0.47 | 9.55±0.57 |

| MHCC97-L | 1.29±0.52 | 4.63±0.93 | – |

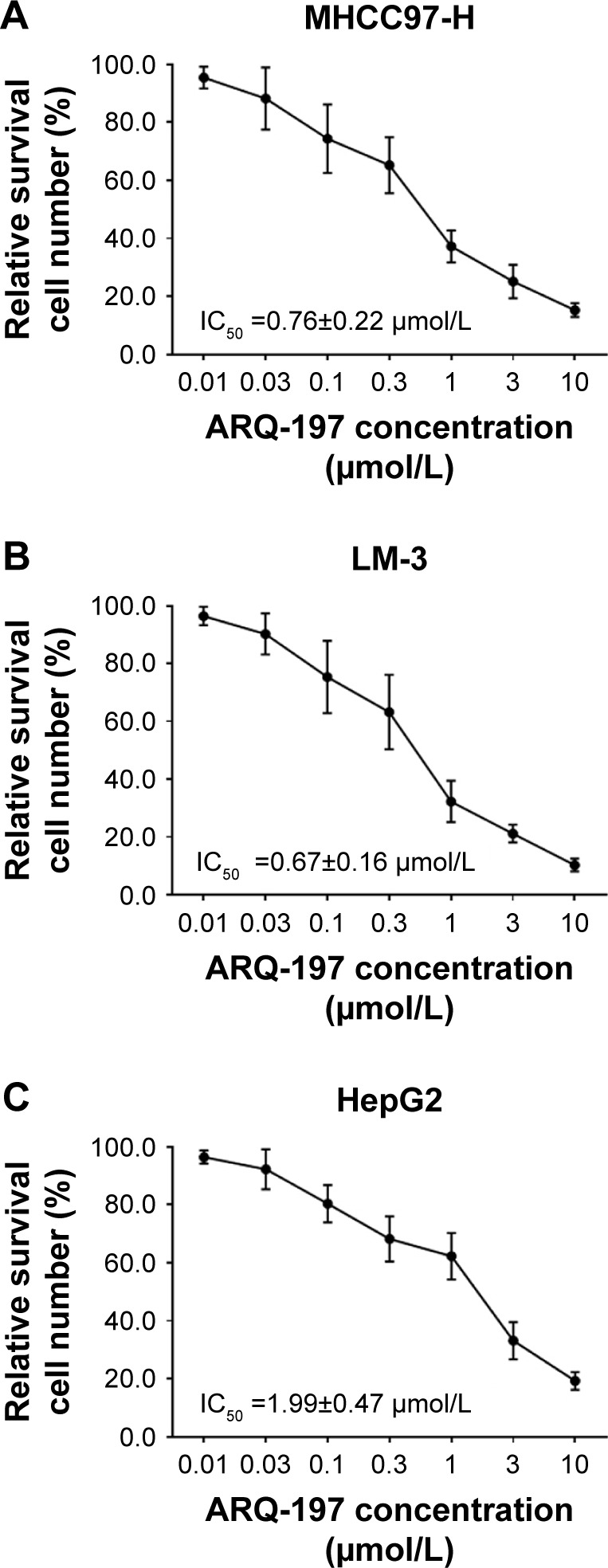

ARQ-197 enhances the in vitro antitumor effect of sorafenib on HCC cells

To examine whether ARQ-197 enhances the antitumor effect of sorafenib on HCC cells, we performed combined treatment and MTT assay. As shown in Figure 3, ARQ-197 treatment at IC25 concentration enhanced the antitumor effect of sorafenib on HCC cells MHCC97-H (Figure 3A), LM-3 (Figure 3B), and HepG2 (Figure 3C). Moreover, ARQ-197 treatment decreased the IC50 value of sorafenib on HCC cells (Table 4). Therefore, ARQ-197 enhances the in vitro antitumor effect of sorafenib on HCC cells.

Figure 3.

ARQ-197 enhances the antitumor effect of sorafenib or inhibits the survival of HCC cells in a dose-dependent manner.

Notes: The HCC cells MHCC97-H (A), LM-3 (B), and HepG2 (C), which were pretreated with IC25 concentration of ARQ-197, were treated with indicated concentrations of sorafenib. Next, the cells were analyzed by MTT experiments. Inhibition rates of sorafenib on HCC cells were calculated at OD 490 nm.

Abbreviation: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Table 4.

ARQ-197 enhances the sensitivity of HCC cells to sorafenib

| Cell lines | Solvent control

|

ARQ-197

|

|---|---|---|

| IC50 values of sorafenib (μmol/L) | ||

|

| ||

| MHCC97-H | 1.39±0.46 | 0.24±0.05 |

| LM-3 | 1.29±0.25 | 0.22±0.07 |

| HepG2 | 1.68±0.42 | 0.53±0.17 |

| MHCC97-L | 2.73±0.40 | 0.97±0.39 |

Abbreviation: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

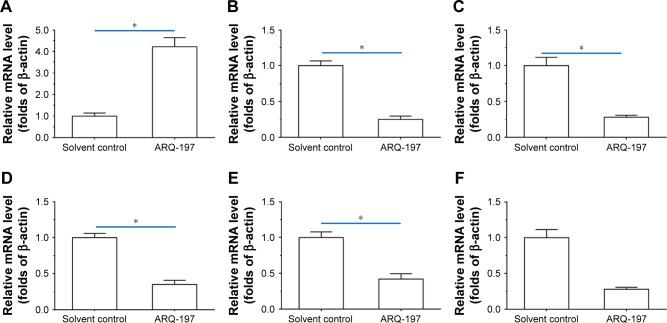

ARQ-197 inhibits the expression of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and multidrug resistance (MDR) related genes

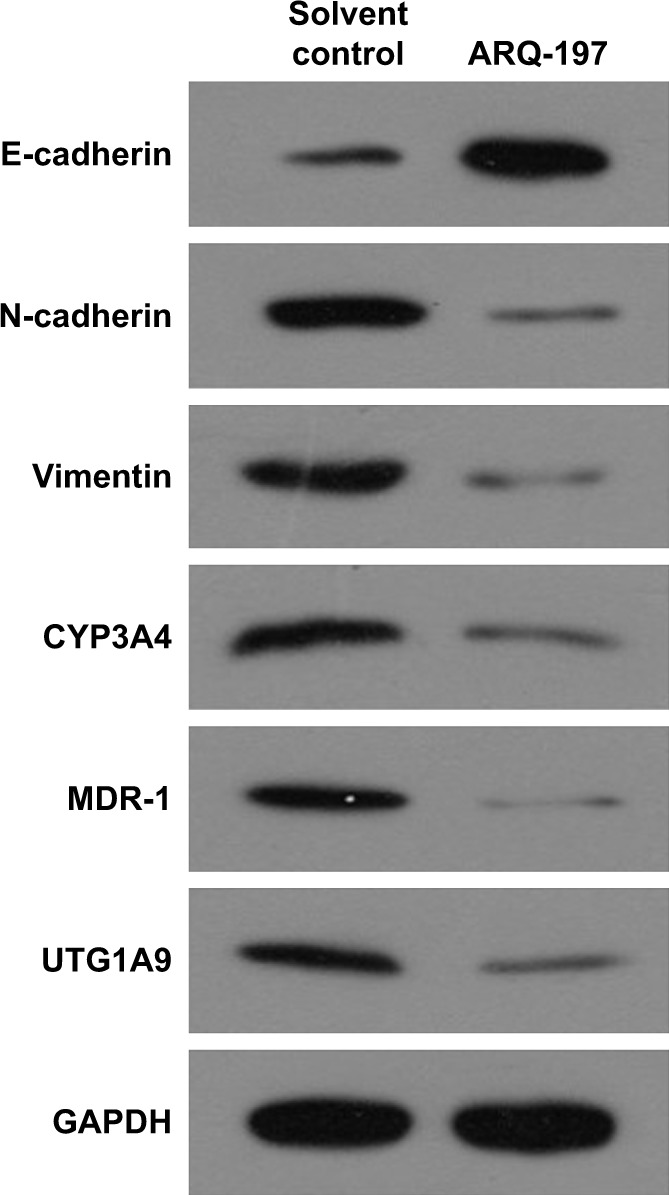

To examine the working mechanism of ARQ-197, the effect of ARQ-197 on the expression of genes related to EMT and MDR was examined by qPCR. It is well known that EMT is an important process that participates in drug resistance. As shown in Figure 4, treatment of MHCC87-H cells with ARQ-197 at IC25 concentration enhanced the expression of E-cadherin (Figure 4A), an indicator of epithelial formation, and decreased the expression of N-cadherin (Figure 4B) and vimentin (Figure 4C), two indicators of mesenchymal formation. This result suggests that ARQ-197 treatment inhibited the EMT process of MHCC97-H cells. Next, the effect of ARQ-197 on PXR-induced drug resistance was examined. As shown in Figure 4, ARQ-197 treatment at IC25 concentration decreased the expression of drug resistance-related genes: Cyp3a4 (Figure 4D), Mdr-1 (Figure 4E), and Ugt1a9 (Figure 4F). Similar results were obtained from Western blotting (Figure 5). Therefore, ARQ-197 inhibited the expression of genes related to MDR in MHCC97-H cells.

Figure 4.

ARQ-197 inhibits EMT- or MDR-related genes’ expression in MHCC97-H cells.

Notes: MHCC97-H cells, which were treated with IC25 concentration of ARQ-197, were harvested for qPCR experiments. The mRNA level of EMT-related genes, E-cadherin (A), N-cadherin (B), vimentin (C), or MDR-related genes, CYP3A4 (D), MDR-1 (E), UTG1A9 (F), was examined by qPCR. *P<0.05.

Abbreviations: EMT, epithelial–mesenchymal transition; MDR, multidrug resistance; qPCR, quantitative real-time PCR.

Figure 5.

ARQ-197 inhibits the protein level of EMT- or MDR-related genes’ expression in MHCC97-H cells.

Notes: MHCC97-H cells, which were treated with IC25 concentration of ARQ-197, were harvested for Western blot experiments. The protein levels of EMT-related genes, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, vimentin, or MDR-related genes, CYP3A4, MDR-1, UTG1A9, were examined by their antibodies.

Abbreviations: EMT, epithelial–mesenchymal transition; MDR, multidrug resistance.

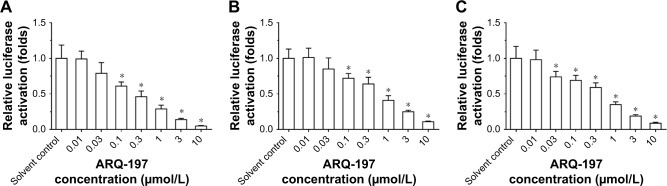

ARQ-197 inhibits the transcription factor activities of ETS-1 and PXR

Moreover, previous work from our lab had revealed that, HGF/c-MET signaling pathway promoted sorafenib resistance by enhancing PXR downstream drug resistance-related genes’ expression via interaction between PXR and ETS-1.45 To further examine the effect of ARQ-197, luciferase experiments were performed. We transfected ETS-1 responsible gene reporter plasmid EBS-Luc or PXR responsible gene reporter plasmids DR3-Luc or ER6-Luc, respectively, and then administered ARQ-197. As shown in Figure 6, ARQ-197 treatment inhibited the luciferase activities of EBS-Luc reporter (Figure 6A), DR3-Luc (Figure 6B), and ER6-Luc (Figure 6C) in a dose-dependent manner. These results indicate that ARQ-197 inhibits the expression of genes related to EMT or MDR by decreasing the transcription factor activities of ETS-1 and PXR.

Figure 6.

ARQ-197 decreases the transcription factor activation of ETS-1 and PXR in MHCC97-H cells.

Notes: MHCC97-H cells which were transfected with luciferase reporters of (A) ETS-1 (EBS-Luc) or luciferase reporters of PXR (DR3-Luc [B] or ER6-Luc [C]) were treated with indicated concentration of ARQ-197. *P<0.05.

Abbreviations: DR3, direct repeat 3; ER6, everted repeat 6.

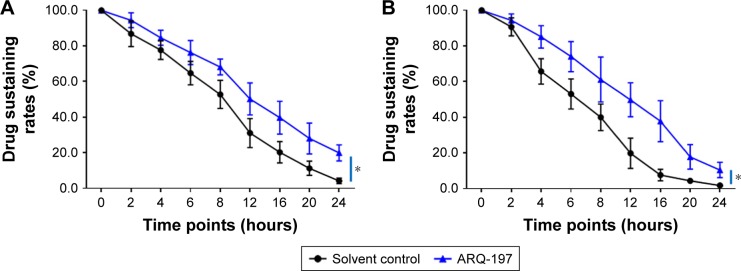

ARQ-197 decelerates the clearance of sorafenib in HCC cells

The clearance of sorafenib in HCC cells was examined by LC-MS/MS. As shown in Figure 7, ARQ-197 treatment decelerated the clearance of sorafenib in MHCC97-H cells. The half-life time (t1/2) of sorafenib in MHCC97-H cells increased from 9.08±0.43 to 13.60±0.65 hours. Moreover, ARQ-197 also decelerated the clearance of sorafenib in subcutaneous MHCC97-H tumors. The half-life time (t1/2) of sorafenib in tumors increased from 19.49±0.79 to 30.33±0.98 hours. Table 5 shows the half-life of sorafenib in HCC cells with ARQ-197 or solvent control treatment. Moreover, to reveal the specificity of ARQ-197, PXR siRNA or ETS-1 siRNA was used. As shown in Table 6, knockdown of ETS-1 or PXR’s expression decelerated the clearance of sorafenib in MHCC97-H or LM-3 cells. ARQ-197 did not affect the half-life values of sorafenib in MHCC97-H or LM-3 cells in the presence of ETS-1 siRNA or PXR siRNA (Table 6). These data suggest that c-MET functions in a PXR/ETS-1-dependent manner.

Figure 7.

ARQ-197 decelerates the clearance of sorafenib in MHCC97-H cells.

Notes: (A) MHCC97-H cells, which were treated with IC25 concentration sorafenib for 12 hours, were harvested at indicated time points. (B) Sorafenib solution was injected into subcutaneous tumor formed by MHCC97-H cells, and tumor tissues were harvested at indicated time points. Samples were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Drugs clearance curve was calculated based on the sustaining of sorafenib in cells or tumors. *P<0.05.

Abbreviation: LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry.

Table 5.

ARQ-197 decelerated the clearance of sorafenib in HCC cells

| Cell lines | Models | Solvent control

|

ARQ-197

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Half-life of sorafenib (t1/2, hours) | |||

|

| |||

| MHCC97-H | Cultured cells | 9.08±0.43 | 13.60±0.65 |

| Subcutaneous tumor | 19.49±0.79 | 30.33±0.98 | |

| LM-3 | Cultured cells | 9.93±0.57 | 14.42±0.67 |

| Subcutaneous tumor | 18.80±0.72 | 39.10±0.92 | |

| HepG2 | Cultured cells | 9.62±0.82 | 12.46±0.62 |

| Subcutaneous tumor | 16.56±0.44 | 29.72±0.91 | |

| MHCC97-L | Cultured cells | 10.21±0.51 | 12.59±0.18 |

| Subcutaneous tumor | 18.09±0.22 | 24.36±0.55 | |

Abbreviation: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Table 6.

ARQ-197 decelerated the clearance of sorafenib in HCC cells in the presence of PXR or ETS-1

| Cell lines | Models | Solvent control

|

ARQ-197

|

ETS-1 siRNA

|

PXR siRNA

|

ETS-1 siRNA +ARQ-197

|

PXR siRNA +siRNA

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Half-life of sorafenib (t1/2, hours) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| MHCC97-H | Cultured cells | 9.08±0.43 | 13.60±0.65 | 13.85±0.84 | 17.69±0.91 | 13.53±0.23 | 17.62±0.88 |

| Subcutaneous tumor | 19.49±0.79 | 30.33±0.98 | 30.76±1.06 | 42.07±2.79 | 30.96±0.46 | 40.13±0.83 | |

| LM-3 | Cultured cells | 9.93±0.57 | 14.42±0.67 | 15.61±0.46 | 18.00±0.25 | 15.22±0.18 | 18.44±0.67 |

| Subcutaneous tumor | 18.80±0.72 | 39.10±0.92 | 39.45±0.74 | 52.88±0.95 | 38.26±0.60 | 50.29±3.57 | |

Abbreviation: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

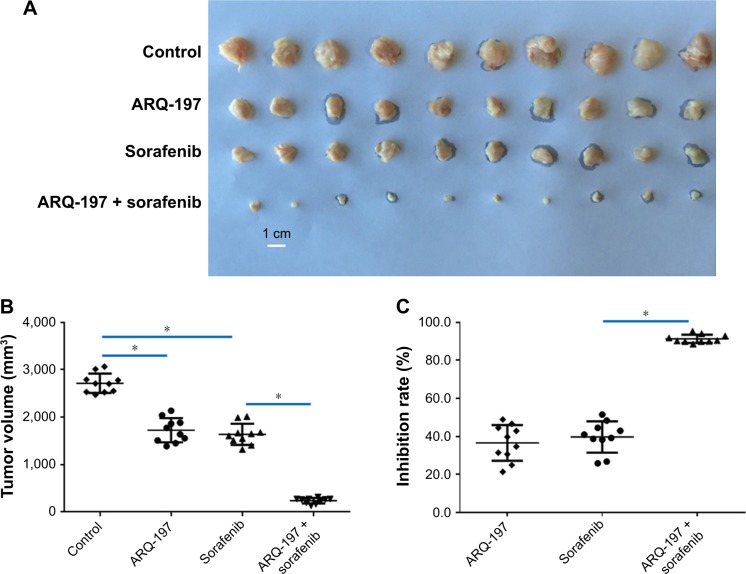

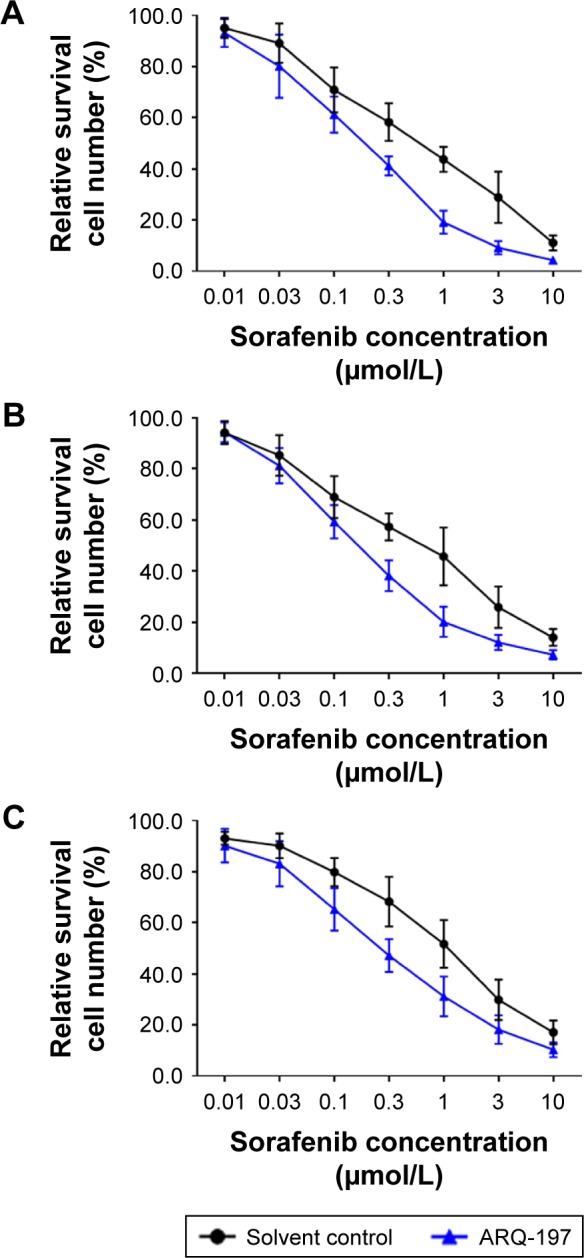

ARQ-197 enhances the in vivo antitumor effect of sorafenib on HCC tumor model

To examine the in vivo antitumor effect of ARQ-197, we administered ARQ-197 to nude mice HCC models. As shown in Figure 8, treatment with 3 mg/kg ARQ-197 or 2 mg/kg sorafenib or together inhibited the subcutaneous growth of MHCC97-H tumors compared to the vehicle controls. ARQ-197 treatment significantly enhanced the antitumor effect of sorafenib, compared to sorafenib alone (Figure 8). Therefore, as expected, ARQ-197 treatment enhanced the antitumor effect of sorafenib on HCC tumor growth.

Figure 8.

ARQ-197 enhances the antitumor effect of sorafenib on the subcutaneous growth of MHCC97-H cells in nude mice.

Notes: MHCC97-H cells were seeded into nude mice to form subcutaneous tumors. Nude mice received oral administration of solvent control, ARQ-197, sorafenib, or ARQ-197 + sorafenib. Tumors were harvested and tumor volumes or tumor weights were noted. Results are shown as photographs of subcutaneous tumors (A), tumor volumes (B), inhibition rates of agents on MHCC97-H cells’ subcutaneous growth calculated from tumor volumes (C), or tumor weights (D), orinhibition rates of agents on MHCC97-H cells’ subcutaneous growth calculated from tumor weights (E). *P<0.05.

Discussion

At present, despite the fast progress made in the research of advanced HCC, patients’ prognosis or clinical outcome is still poor.49–51 Various local therapeutic strategies including radio-frequency ablation (RFA) and transcatheter arterial chemo-embolization (TACE) can delay the disease progression and reduce the tumor burden of advanced HCC, but the recurrence of the malignancy after treatment has made treating options even narrower.52–55 These situations make chemotherapies important for advanced HCC treatment. Advanced HCC is insensitive to traditional cytotoxic chemotherapies and is featured to have MDR.56,57 Therefore, development of more effective molecular targeted therapy has always been the top priority of research. In the present work, we demonstrated that ARQ-197 treatment enhanced the sensitivity of HCC cells to sorafenib. Currently, combination therapies are mainly considered as combinations of different treatment strategies, such as TACE + RFA, TACE + sorafenib, or RFA + sorafenib.58–61 On the other hand, there are many reports of combined cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs and molecular targeted drugs or therapeutic antibodies.62–65 Although there are very few reports on molecular targeted agents’ combination, this type of combination per se is a promising strategy for cancer treatment. For example, vemurafenib + cobimetinib, dabrafenib + trametinib, and encorafenib + binimetinib have been proved to be effective in melanoma treatment.66 Our results show that the combination of ARQ-197 and sorafenib helped to achieve better therapeutic effect.

Sorafenib resistance may be achieved through multiple molecular mechanisms. EMT process and HGF/c-MET pathway are foremost molecular mechanisms of antitumor drug resistance, which significantly promotes the antitumor effect of drugs on cancer cells.67–77 Jiao et al showed that HGF treatment induced gefitinib resistance in human lung cancer cells and miR-1-3 p or miR-206 sensitizes cells to gefitinib by inhibition of c-Met and EMT process.78 In the present work, we found that ARQ-197 inhibited the EMT process of HCC cells and enhanced the sensitivity of HCC cells to sorafenib.

Moreover, ARQ-197 also inhibited the activation of PXR, which is the key regulator for exogenous drug metabolism and detoxification in cells.79,80 Previous studies have also shown that sorafenib can act as a ligand/agonist for PXR during treatment, promoting the expression of PXR downstream drug resistance–related genes by inducing PXR’s transcription factor activity, ultimately resulting in sorafenib resistance.47,81 In HCC cells, the transcription factor ETS-1, an important effector of HGF/c-MET signaling pathway, could function as a co-regulator of PXR and enhance sorafenib resistance. In the present work, we found that ARQ-197 inhibited the activation of PXR as the mechanistic explanation for the decelerated clearance of sorafenib in HCC cells. ARQ-197 decreased the expression of Cyp3a4, Mdr-1, and Utg1a9, the downstream genes of PXR, in HCC cells. MDR-1 is the most important Phase II drug-metabolizing enzyme,82 CYP3A4 is a Phase I drug-resistance enzyme, and UTG1A9 is a Phase III drug-resistance enzyme mediating sorafenib metabolism.83–85 It is well known that binding of HGF to c-MET induced the activation of multiple downstream metabolic pathways, including the mTOR pathway.86 Our results extended our knowledge about HGF/c-MET in drug metabolism. Sorafenib is the first-class molecular targeted drug for advanced HCC approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. In addition to sorafenib, regorafenib and lenvatinib have recently been approved for marketing.87,88 Future exploration of the combination of ARQ-197 with new molecular targeted drugs such as regorafenib and lenvatinib is of great significance.

Conclusion

We report that ARQ-197 enhanced the sensitivity of HCC cells to sorafenib by decelerating the clearance of sorafenib in cultured HCC cells or subcutaneous HCC tumors in nude mice. Also, our data indicate that the combination of ARQ-197 and sorafenib can upregulate the antitumor effect of sorafenib on HCC cells.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing, People’s Republic of China (grant number 7172205 to XG).

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the design and conception, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. Authors took part in either drafting or revising the manuscript. At the same time, authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Razavi-Shearer D, Gamkrelidze I, Nguyen MH, Polaris Observatory Collaborators Global prevalence, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in 2016: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(6):383–403. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang S, Wang F, Zhang Z. Current advances in the elimination of hepatitis B in China by 2030. Front Med. 2017;11(4):490–501. doi: 10.1007/s11684-017-0598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang FS, Fan JG, Zhang Z, Gao B, Wang HY. The global burden of liver disease: the major impact of China. Hepatology. 2014;60(6):2099–2108. doi: 10.1002/hep.27406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1301–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyun MH, Lee YS, Kim JH, et al. Hepatic resection compared to chemo-embolization in intermediate- to advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of high-quality studies. Hepatology. 2018;68(3):977–993. doi: 10.1002/hep.29883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomaa A, Waked I. Management of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: review of current and potential therapies. Hepatoma Res. 2017;3(6):112–122. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow PKH, Gandhi M, Tan SB, et al. Asia-Pacific Hepatocellular Carcinoma Trials Group SIRveNIB: selective internal radiation therapy versus sorafenib in Asia-Pacific patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1913–1921. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.0892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reiss KA, Yu S, Mamtani R, et al. Starting dose of sorafenib for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective, multi-institutional study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(31):3575–3581. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.8245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sharp Investigators Study Group Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a Phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu YJ, Zheng B, Wang HY, Chen L, Zhu YJ, Wang HY. New knowledge of the mechanisms of sorafenib resistance in liver cancer. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38(5):614–622. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuneo KC, Mehta RK, Kurapati H, Thomas DG, Lawrence TS, Nyati MK. Enhancing the radiation response in KRAS mutant colorectal cancers using the c-Met inhibitor crizotinib. Transl Oncol. 2019;12(2):209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parr C, Ali AY. Boswellia frereana suppresses HGF-mediated breast cancer cell invasion and migration through inhibition of c-Met signalling. J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):281. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1660-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.García-Vilas JA, Medina MÁ. Updates on the hepatocyte growth factor/c-Met axis in hepatocellular carcinoma and its therapeutic implications. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(33):3695–3708. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i33.3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun CY, Zhu Y, Li XF, et al. Norcantharidin alone or in combination with crizotinib induces autophagic cell death in hepatocellular carcinoma by repressing c-Met-mTOR signaling. Oncotarget. 2017;8(70):114945–114955. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szparecki G, Ilczuk T, Gabzdyl N, Stocka-Łabno E, Górnicka B. Expression of c-met protein in various subtypes of hepatocellular adenoma compared to hepatocellular carcinoma and non-neoplastic liver in human tissue. Folia Biol (Praha) 2017;63:146–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zakaria S, Helmy MW, Salahuddin A, Omran G. Chemopreventive and antitumor effects of benzyl isothiocynate on HCC models: a possible role of HGF/pAkt/STAT3 axis and VEGF. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strickler JH, Weekes CD, Nemunaitis J, et al. First-in-human Phase I, dose-escalation and -expansion study of Telisotuzumab Vedotin, an antibody–drug conjugate targeting c-Met, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(33):3298–3306. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.7697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Virzì AR, Gentile A, Benvenuti S, Comoglio PM. Reviving oncogenic addiction to Met bypassed by BRAF (G469A) mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(40):10058–10063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1721147115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, Nie Y, Zhang K, et al. Solution structure of SHIP2 SH2 domain and its interaction with a phosphotyrosine peptide from c-met. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2018;656:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2018.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheri KC, Leonetti E, Laino L, et al. C-Met receptor as potential bio-marker and target molecule for malignant testicular germ cell tumors. Oncotarget. 2018;9(61):31842–31860. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding X, Ji J, Jiang J, et al. HGF-mediated crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and MET-unamplified gastric cancer cells activates coordinated tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(9):867. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0922-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monk P, Liu G, Stadler WM, et al. Phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of tivantinib in men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) Invest New Drugs. 2018;36(5):919–926. doi: 10.1007/s10637-018-0630-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weekes CD, Clark JW, Zhu AX. Tivantinib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: is Met still a viable target? Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(5):591–592. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rimassa L, Assenat E, Peck-Radosavljevic M, et al. Tivantinib for second-line treatment of MET-high, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (METIV-HCC): a final analysis of a Phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(5):682–693. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, Bao Z, Liao H, et al. The efficacy and safety of tivantinib in the treatment of solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(68):113153–113162. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouattour M, Raymond E, Qin S, et al. Recent developments of c-Met as a therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67(3):1132–1149. doi: 10.1002/hep.29496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rebouissou S, La Bella T, Rekik S, et al. Proliferation markers are associated with MET expression in hepatocellular carcinoma and predict tivantinib sensitivity in vitro. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(15):4364–4375. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang YP, Qu JH, Chang XJ, et al. High intratumoral metastasis-associated in colon cancer-1 expression predicts poor outcomes of cryoablation therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2013;11(1):41. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jia H, Yang Q, Wang T, et al. Rhamnetin induces sensitization of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to a small molecular kinase inhibitor or chemotherapeutic agents. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1860;2016(7):1417–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Y, Feng F, Gao X, et al. MiRNA153 reduces effects of chemotherapeutic agents or small molecular kinase inhibitor in HCC cells. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2015;15(3):176–187. doi: 10.2174/1568009615666150225122635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng F, Lu YY, Zhang F, et al. Long interspersed nuclear element ORF-1 protein promotes proliferation and resistance to chemotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(7):1068–1078. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i7.1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li L, Liang Y, Kang L, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the Warburg effect in cancer by Six1. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(3):368–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu X, Fan Z, Liang C, et al. A signature motif in LIM proteins mediates binding to checkpoint proteins and increases tumour radiosensitivity. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14059. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y, Zeng Q, Liu X, et al. LINE-1 ORF-1p enhances the transcription factor activity of pregnenolone X receptor and promotes sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:4421–4438. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S176088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Q, Feng F, Zhang F, et al. LINE-1 ORF-1p functions as a novel HGF/ETS-1 signaling pathway co-activator and promotes the growth of MDA-MB-231 cell. Cell Signal. 2013;25(12):2652–2660. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao J, Bai Z, Feng F, et al. Cross-talk between EPAS-1/HIF-2α and PXR signaling pathway regulates multi-drug resistance of stomach cancer cell. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016;72:73–88. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L, Zhao L, Jia X, et al. Aminophenols increase proliferation of thyroid tumor cells by inducing the transcription factor activity of estrogen receptor α. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:621–628. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma H, Yao Y, Wang C, et al. Transcription factor activity of estrogen receptor α activation upon nonylphenol or bisphenol a treatment enhances the in vitro proliferation, invasion, and migration of neuroblastoma cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:3451–3463. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S105745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang Y, Xu X, Wang T, et al. The EGFR/miR-338-3p/EYA2 axis controls breast tumor growth and lung metastasis. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(7):e2928. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ji Q, Xu X, Li L, et al. miR-216a inhibits osteosarcoma cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis by targeting CDK14. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(10):e3103. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li L, Kang L, Zhao W, et al. miR-30a-5p suppresses breast tumor growth and metastasis through inhibition of LDHA-mediated Warburg effect. Cancer Lett. 2017;400:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu M, Zhao G, Zhuang X, et al. Triclosan treatment decreased the antitumor effect of sorafenib on hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:2945–2954. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S165436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao Z, Li Y, Dai W, et al. Ets-1 induces sorafenib-resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via regulating transcription factor activity of PXR. Pharmacol Res. 2018;135:188–200. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng F, Jiang Q, Cao S, et al. Pregnane X receptor mediates sorafenib resistance in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 1862;2018:1017–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.An L, Li DD, Chu HX, et al. Terfenadine combined with epirubicin impedes the chemo-resistant human non-small cell lung cancer both in vitro and in vivo through EMT and Notch reversal. Pharmacol Res. 2017;124:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.European Association for the Study of the Liver1; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer EASL–EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kulik L, Heimbach JK, Zaiem F, et al. Therapies for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma awaiting liver transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):381–400. doi: 10.1002/hep.29485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu R, Zhao D, Zhang X, et al. A20 enhances the radiosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to 60Co-γ ionizing radiation. Oncotarget. 2017;8(54):93103–93116. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang R, Ma M, Lin XH, et al. Extracellular matrix collagen I promotes the tumor progression of residual hepatocellular carcinoma after heat treatment. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):901. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4820-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xie H, Yu H, Tian S, et al. MEIS-1 level in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma can predict the post-treatment outcomes of radiofrequency ablation. Oncotarget. 2018;9(20):15252–15265. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang JH, Zhong XP, Zhang YF, et al. Cezanne predicts progression and adjuvant TACE response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(9):e3043. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang X, Xia W, Chen L, et al. Synergistic antitumor effect of a γ-secretase inhibitor PF-03084014 and sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9(79):34996–35007. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim DW, Talati C, Kim R. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): beyond sorafenib-chemotherapy. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;8(2):256–265. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2016.09.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hou J, Hong Z, Feng F, et al. A novel chemotherapeutic sensitivity-testing system based on collagen gel droplet embedded 3D-culture methods for hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):729. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3706-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xie H, Yu H, Tian S, et al. What is the best combination treatment with transarterial chemoembolization of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma? A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(59):100508–100523. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feng F, Jiang Q, Jia H, et al. Which is the best combination of TACE and sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treatment? A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Pharmacol Res. 2018;135:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ishikawa K, Chiba T, Ooka Y, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization as a substitute to radiofrequency ablation for treating Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage 0/A hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9(30):21560–21568. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaibori M, Yoshii K, Hasegawa K, et al. Treatment optimization for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients in a Japanese nationwide cohort. Ann Surg. 2018 Mar 30; doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002751. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martins-Neves SR, Cleton-Jansen AM, Gomes CMF. Therapy-induced enrichment of cancer stem-like cells in solid human tumors: where do we stand? Pharmacol Res. 2018;137:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sailo BL, Banik K, Padmavathi G, Javadi M, Bordoloi D, Kunnumakkara AB. Tocotrienols: the promising analogues of vitamin E for cancer therapeutics. Pharmacol Res. 2018;130:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goyal L, Zheng H, Abrams TA, et al. A Phase II and biomarker study of sorafenib combined with modified FOLFOX in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(1):80–89. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lyu N, Kong Y, Mu L, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin vs. sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schadendorf D, van Akkooi ACJ, Berking C, et al. Melanoma. Lancet. 2018;392(10151):971–984. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31559-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang PF, Wang F, Wu J, et al. LncRNA SNHG3 induces EMT and sorafenib resistance by modulating the miR-128/CD151 pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(3):2788–2794. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mathur A, Kumar A, Babu B, Chandna S. In vitro mesenchymal–epithelial transition in NIH3T3 fibroblasts results in onset of low-dose radiation hypersensitivity coupled with attenuated connexin-43 response. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2018;1862:414–426. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vallese F, Mishra NM, Pagliari M, et al. Helicobacter pylori antigenic Lpp20 is a structural homologue of Tipα and promotes epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 1861;2017:3263–3271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watt K, Newsted D, Voorand E, et al. MicroRNA-206 suppresses TGF-β signalling to limit tumor growth and metastasis in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Signal. 2018;50:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim SH, Lee WH, Kim SW, et al. EphA3 maintains radioresistance in head and neck cancers through epithelial mesenchymal transition. Cell Signal. 2018;47:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang Y, Li D, Jiang Q, et al. Novel ADAM-17 inhibitor ZLDI-8 enhances the in vitro and in vivo chemotherapeutic effects of sorafenib on hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(7):743. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0804-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhao H, Wang Z, Tang F, et al. Carnosol-mediated Sirtuin 1 activation inhibits enhancer of Zeste homolog 2 to attenuate liver fibrosis. Pharmacol Res. 2018;128:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gao W, Han J. Overexpression of ING5 inhibits HGF-induced proliferation, invasion and EMT in thyroid cancer cells via regulation of the c-Met/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;98:265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Y, Zhang H, Li Y, et al. MiR-182 inhibits the epithelial to mesenchymal transition and metastasis of lung cancer cells by targeting the Met gene. Mol Carcinog. 2018;57(1):125–136. doi: 10.1002/mc.22741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Siddiqui-Jain A, Hoj JP, Hargiss JB, et al. Pyridine–pyrimidine amides that prevent HGF-induced epithelial scattering by two distinct mechanisms. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017;27(17):3992–4000. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu F, Song S, Yi Z, et al. HGF induces EMT in non-small-cell lung cancer through the hBVR pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;811:180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jiao D, Chen J, Li Y, et al. miR-1-3p and miR-206 sensitizes HGF-induced gefitinib-resistant human lung cancer cells through inhibition of c-Met signalling and EMT. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22(7):3526–3536. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pu S, Wu X, Yang X, et al. The therapeutic role of xenobiotic nuclear receptors against metabolic syndrome. Curr Drug Metab. 2018 Jan 10; doi: 10.2174/1389200219666180611083155. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Buchman CD, Chai SC, Chen T. A current structural perspective on PXR and CAR in drug metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2018;14(6):635–647. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2018.1476488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mackowiak B, Hodge J, Stern S, Wang H. The roles of xenobiotic receptors: beyond chemical disposition. Drug Metab Dispos. 2018;46(9):1361–1371. doi: 10.1124/dmd.118.081042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hubacek JA. Drug metabolising enzyme polymorphisms in middle- and Eastern-European Slavic populations. Drug Metabol Drug Interact. 2014;29(1):29–36. doi: 10.1515/dmdi-2013-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Edginton AN, Zimmerman EI, Vasilyeva A, Baker SD, Panetta JC. Sorafenib metabolism, transport, and enterohepatic recycling: physiologically based modeling and simulation in mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77(5):1039–1052. doi: 10.1007/s00280-016-3018-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Peer CJ, Sissung TM, Kim A, et al. Sorafenib is an inhibitor of UGT1A1 but is metabolized by UGT1A9: implications of genetic variants on pharmacokinetics and hyperbilirubinemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(7):2099–2107. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang Y, Hou J, Feng F, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases 1A7 and the risk of gastrointestinal carcinomas: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(39):66371–66381. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pievsky D, Pyrsopoulos N. Profile of tivantinib and its potential in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: the evidence to date. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2016;3:69–76. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S106072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised Phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]