ABSTRACT

Objectives

To determine the BD Onclarity human papillomavirus (HPV) assay performance and risk values for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN2) or higher and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN3) or higher during Papanicolaou/HPV cotesting in a negative for intraepithelial lesions or malignancies (NILM) population.

Methods

In total, 22,383 of the 33,858 enrolled women were 30 years or older with NILM cytology. HPV+ and a subset of HPV– patients (3,219/33,858 combined; 9.5%) were referred to colposcopy/biopsy.

Results

Overall, 7.9% of women were Onclarity positive; HPV 16 had the highest prevalence (1.5%). Verification bias-adjusted (VBA) CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher prevalences were 0.9% and 0.3%, respectively. Onclarity had VBA CIN2 or higher (44.1%) and CIN3 or higher (69.5%) sensitivities, as well as CIN2 or higher (92.4%) and CIN3 or higher (92.3%) specificities—all similar to Hybrid Capture 2. HPV 16, 18, 45, and the other 11 genotypes had CIN3 or higher risks of 6.9%, 2.6%, 1.1%, and 2.2%, respectively.

Conclusions

Onclarity is clinically validated for cotesting in NILM women. Genotyping actionably stratifies women at greater CIN3 or higher risk.

Keywords: Cervical cancer screening, Cotesting, Human papillomavirus, Genotype, Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, Negative for intraepithelial lesions and malignancies, Adjunct testing

Infection of the genital tract by mucosotropic human papillomavirus (HPV) types is nearly ubiquitous.1 Most infections are asymptomatic and innocuous. Yet a subset of infections with high-risk HPV types may lead to transformation of the cervical epithelium, producing cervical neoplasia.1,2 Hence, more than 95% of cervical cancer is caused by a panel of 13 to 14 HPV types that are detected in clinically valid HPV screening tests.3-7 As cervical cytology may miss a significant percentage of precancer or cancer cases, many countries have implemented HPV testing to supplement8,9 or, in some cases, replace10 cytology-based cervical cancer screening. In the United States in 2018, HPV testing is recommended for screening as a triage for atypical squamous cells–undetermined significance (ASC-US) cytology in women 21 years or older, as an adjunct test to cytology in women 30 years or older, or as a primary screening test in women 25 years or older or 30 years or older.11-14 Several randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that HPV-based screening reduces the incidence of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or cervical cancer cases during subsequent screening rounds compared with cytology alone.15-20

Published guidelines have integrated risk-based approaches for screening, triage, management, and treatment following cervical cancer screening efforts.13,21 Although no universal thresholds for any of these management strategies exist,21 3- and 5-year risk values for CIN grade 3 (CIN3) or higher associated with low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) cytology (4.3% and 5.2%, respectively) have been identified as a US benchmark for referral to colposcopy.22-24 For women 30 years or older, cotesting with HPV more effectively predicts risk for cervical cancer and precancer, compared with cytology alone, and facilitates extension of the screening interval duration from 3 to 5 years.11,14 In addition, cotesting increases sensitivity to detect CIN3 or higher cervical pathology,25 provides greater negative predictive value,26 and offers assurance in the accuracy of a negative screening result.12,17,27,28

Although HPV testing improves the ability to detect women who are at high risk for cervical cancer and precancer, the prevalence of HPV in women without cervical disease reduces the specificity of cotesting during screening. Genotyping for HPV-positive women can increase the ability to assess risk in cotesting scenarios compared with testing only for overall, pooled HPV results.29 For example, Schiffman et al,30 studying a partial genotyping assay, demonstrated that women (≥30 years of age) with negative for intraepithelial lesions or malignancies (NILM) cytology were at higher cumulative 3-year risk for CIN3 or higher pathology if they were HPV 16 (10.3%) or HPV 18 (5.0%) positive, compared with those positive for any HPV type other than HPV 16/18 (2.3%). Stratification in this way can effectively allow for triage of women at or above the threshold for a referral to colposcopy, without generating a large number of additional, unnecessary colposcopies for women not at a high risk for cancer.29,31

The Onclarity (Becton, Dickinson and Company, BD Life Sciences–Diagnostic Systems) HPV assay was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an HPV assay for use during cotesting with liquid-based cytology (LBC) in women 30 years or older and is the first DNA test approved for individual reporting of HPV 16, 18, and 45 with this cotesting strategy. This report describes baseline data from the Onclarity HPV trial, a study involving over 33,000 women (≥21 years of age), conducted to determine the performance of the Onclarity HPV assay during routine screening. Here, a subset of women with NILM cytology was selected to determine the efficacy of overall HPV (any of 14 high-risk HPV types) and specific genotypes 16, 18, and 45 for improving risk stratification as a cotest with LBC in women 30 years or older.

Materials and Methods

The study protocol was approved by institutional review boards at all study sites, and written informed consent was obtained prior to any trial-related procedures. This study was conducted according to the principles set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. This report was prepared according to Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) reporting standards.

The study protocol, including details of each visit, is described in detail in a prior publication.32 For clarity, relevant details are briefly as follows.

Study Design

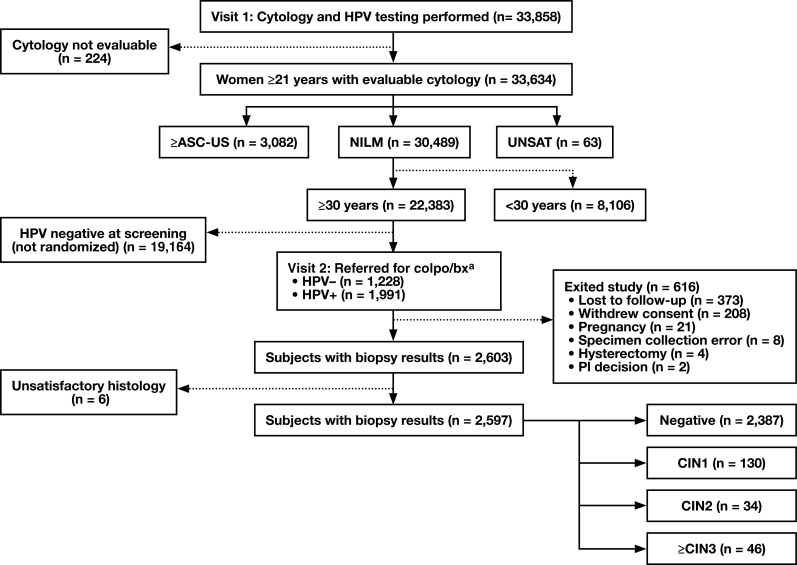

This study was conducted in two phases: a baseline and a 3-year longitudinal phase. The baseline design and selection algorithm for a referral to colposcopy and biopsy, established by LBC result, age, and HPV results for the baseline study, have been described in detail previously.32 Subject reconciliation for specimens used in this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Patient reconciliation during baseline enrollment and participation for this study. ≥ASC-US, atypical squamous cells–undetermined significance or greater; CIN1, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1; CIN2, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2; CIN3, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3; colpo/bx, colposcopy and biopsy; HPV, human papillomavirus; NILM, negative for intraepithelial lesions or malignancies; PI, principal investigator; UNSAT, unsatisfactory cytology. aPatients positive/negative for either HC2 or Onclarity (regardless of liquid-based cytology collection method).

The primary study end point was detection of biopsy-proven, high-grade (CIN grade 2 [CIN2] or higher) lesions (CIN2, CIN3, adenocarcinoma in situ, and invasive cervical cancer). Of the 33,858 screened patients, 224 were excluded due to nonevaluable cytology. Of the remaining 33,634 specimens, those with ASC-US or higher (n = 3,082) were discussed in Wright et al,33 and a further 63 with unsatisfactory cytology were not included in the current analysis. Likewise, 8,106 patients were younger than 30 years, leaving 22,383 patients, 30 years or older, with a NILM cytology result. In total, 19,164 patients were not referred to colposcopy/biopsy because they were either negative for HPV at screening or were not included with the 5% of negative patients who were randomly selected for referral. Of the remaining 3,219 patients referred to colposcopy, 1,228 were HPV negative (for all HPV tests) and 1,991 were HPV positive (for any HPV test). From this group, 373 were lost to follow-up, 208 withdrew consent, 21 exited due to pregnancy, eight samples were not used due to collection error, four exited due to hysterectomy, two exited due to a decision by the principal investigator, and six samples were not used due to nonevaluable histology. The final number of NILM (≥30 years) patients with all required specimens evaluable and with complete results in this study was 2,597. The overall HPV vaccination rate (≥1 dose) permitted in the study was capped at 10%.

Enrollment Visit (Study Visit 1)

Two cervical samples were placed into separate LBC vials; one BD SurePath vial (TriPath Imaging) was collected first, followed by one PreservCyt vial (Hologic).

Cytology reporting was performed according to the 2001 Bethesda System. Here, NILM indicates negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy, ASC-US indicates atypical squamous cells–undetermined significance, and LSIL and HSIL indicate low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, respectively.34 Evaluation of cytology was performed without computer-assisted imaging.

The SurePath specimen was used to evaluate cytology and for testing with the BD Onclarity HPV assay (Becton, Dickinson and Company, BD Life Sciences–Diagnostic Systems). The PreservCyt sample was used for Onclarity HPV and the digene Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2; Qiagen) assays. As all women had NILM cytology in this analysis, referral to colposcopy was based solely on at least one positive HPV result from either Onclarity (regardless of LBC collection method) or HC2; a subset of HPV-negative patients was selected for colposcopy/biopsy as controls. Henceforth in this report, HPV indicates high-risk HPV, unless otherwise noted.

Colposcopy and Biopsy Visit (Study Visit 2)

Women selected for colposcopy/biopsy underwent the procedure within 84 days of the enrollment visit, and colposcopists were masked to cytology and HPV assay results. Biopsies were obtained from any lesion or acetowhite area, or a random biopsy, at the squamocolumnar junction, was performed. An endocervical curettage (ECC) was collected from all patients during colposcopy.

Here, as in Stoler et al,32 a three-tiered CIN terminology was used for adjudication of histology: CIN grade 1 (CIN1) indicates LSIL, CIN2 indicates HSIL (CIN2), and CIN3 indicates HSIL (CIN3).35 All H&E-stained biopsy specimens and ECC samples were initially reviewed by two pathologists (M.H.S. and T.C.W.). Each pathologist was provided the age of the patient but otherwise was masked to all other study information. Samples, about which the first two diagnoses did not agree, were reviewed by a third pathologist. Consensus was reached when two of the three pathologists agreed on a diagnosis using eight disease categories: unsatisfactory, negative (including no significant pathologic findings, reactive or inflammatory processes, atypical [equivocal] squamous cell or glandular changes, or squamous metaplasia), CIN1, CIN2, CIN3, adenocarcinoma in situ, squamous cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma (the latter two were compiled into one category). If all three diagnoses were discordant, the specimen(s) in question were reviewed by all three pathologists, together, to achieve a consensus pathology diagnosis. When at least one reviewer identified a biopsy specimen as CIN2 or when one reviewer rated a specimen as CIN2 or higher, with a second reviewer scoring the same sample as less than CIN2, immunostaining for p16INK4A was employed while adjudicating a final diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

Data for prevalence estimates were limited to patients with key demographic information, LBC results, and HPV assay results for all genotypes. Verification bias adjustment (VBA) was used to normalize for the difference in the rate of selection for colposcopy/biopsy (briefly, the entire population was stratified based on HPV results from the assays used in the study; then, CIN– disease status for all patients who did not undergo colposcopy was imputed at the same rate as the observed rates in the patients who underwent colposcopy).36 Unadjusted performance values (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value [PPV], negative predictive value [NPV], positive likelihood ratio [PLR], and negative likelihood ratio [NLR]) were determined using standard statistical methods. VBA-adjusted absolute risk values were calculated by classifying patients hierarchically as HPV 16, else HPV 18, else HPV 45, else HPV 11-other positive, else HPV negative. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CIs) for adjusted performance values and adjusted risks were calculated by using bootstrapping. The lower and upper limits for the 95% CIs were determined using the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bootstrapped distribution.

Results

Demographics of NILM Study Population

In this trial, 22,383 patients were 30 years or older and had NILM cytology Table 1. The mean (43.9 years) and median (43 years) ages were similar in this study population. The racial makeup of this study population was 80.4% white, 16.6% African American, and 1.5% Asian. Hispanic participants represented 20.5% of the study population. The patients were largely nonsmokers, with only 33.9% of patients reporting to be current or former smokers. Given that the HPV vaccine was introduced to the market in 2006, 97.2% of the study population was unvaccinated. Only 1.3% of the patients were immunocompromised. In this population, 10.4% and 6.4% of the patients reported having abnormal cytology or had a colposcopy procedure, respectively, within 5 years prior to participation in this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Characteristics of Patients 30 Years or Older With NILM Cytologya

| Characteristic | Patients With NILM Cytology (n = 22,383) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| Mean | 43.9 |

| SD | 9.6 |

| Median | 43 |

| Minimum | 30 |

| Maximum | 83 |

| Race | |

| Asian | 336 (1.5) |

| African American | 3,722 (16.6) |

| White | 17,988 (80.4) |

| Otherb | 337 (1.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 4,592 (20.5) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 17,789 (79.5) |

| Other | 2 (<0.1) |

| Smoking history | |

| Nonsmoker | 14,794 (66.1) |

| Current | 3,214 (14.4) |

| Past | 4,375 (19.5) |

| HPV vaccinated | |

| Yes | 403 (1.8) |

| No | 21,762 (97.2) |

| Unknown | 218 (1.0) |

| Postmenopausal | 5,590 (25.0) |

| Immunocompromised | 285 (1.3) |

| Abnormal cytology (past 5 years) | 2,330 (10.4) |

| Colposcopy (past 5 years) | 1,439 (6.4) |

HPV, human papillomavirus; NILM, negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy.

aValues are presented as number (%) unless otherwise indicated.

bIncludes American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander.

Prevalence of High-Risk HPV

Of the 22,383 patients with NILM cytology who were included in this study, 22,284 had evaluable HPV results using the Onclarity assay Table 2. Of these patients, 7.9% were positive for any HPV genotype by Onclarity—compared with 6.9% for patients tested with HC2. The prevalence of any HPV-positive result tended to decrease with increasing age. HPV 16 was the most prevalent genotype (1.5%); HPV 18 and HPV 45 had prevalence values of 0.4% and 0.5%, respectively. The combined prevalence of HPV 16/18 and HPV 16/18/45 was 1.9% and 2.4%, respectively. The prevalence of the 11 other genotypes detected by Onclarity was 5.5%.

Table 2.

HPV Detection of Genotype Prevalence by Onclarity Across Age Groups in Patients 30 Years or Older With NILM Cytology

| Age Group, No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV Result | 30-39 y (n = 8,663) | 40-49 y (n = 6,829) | ≥50 y (n = 6,792) | Overall (n = 22,284) |

| Overall HPV | 889 (10.3) | 485 (7.1) | 387 (5.7) | 1,761 (7.9) |

| HPV 16 | 173 (2.0) | 77 (1.1) | 80 (1.2) | 330 (1.5) |

| HPV 18 | 41 (0.5) | 29 (0.4) | 23 (0.3) | 93 (0.4) |

| HPV 45 | 63 (0.7) | 34 (0.5) | 18 (0.3) | 115 (0.5) |

| HPV 16/18 | 214 (2.5) | 106 (1.6) | 103 (1.5) | 423 (1.9) |

| HPV 18/45 | 104 (1.2) | 63 (0.9) | 41 (0.6) | 208 (0.9) |

| HPV 16/18/45 | 277 (3.2) | 140 (2.1) | 121 (1.8) | 538 (2.4) |

| Other 11 GTs | 612 (7.1) | 345 (5.1) | 266 (3.9) | 1,223 (5.5) |

| HPV negative | 7,774 (89.7) | 6,344 (92.9) | 6,405 (94.3) | 20,523 (92.1) |

| HC2 positive | 773/8,644 (8.9) | 421/6,814 (6.2) | 331/6,774 (4.9) | 1,525/22,232 (6.9) |

GT, genotype; HC2, digene Hybrid Capture 2 assay; HPV, human papillomavirus; NILM, negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancies.

HPV Assay Performance

Assay performance characteristics, including sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, PLR, and NLR, for detection of high-grade cervical disease, were determined for Onclarity and HC2 in this study population. Unadjusted Onclarity sensitivity values for CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher were 87.5% and 93.5%, respectively; unadjusted specificity values of Onclarity for CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher were 48.6% and 48.3%, respectively Table 3. Overall PPV for Onclarity was 5.2% for CIN2 or higher and 3.2% for CIN3 or higher. NPV for Onclarity was more than 99% for all high-grade lesion end points. VBA performance values for Onclarity and HC2 were also determined; using Onclarity, sensitivity values for CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher were 44.1% and 69.5%, respectively, and specificity values were 92.4% and 92.3%, respectively.

Table 3.

Performance of Onclarity vs HC2 for Detection of High-Grade CIN in Patients 30 Years or Older With NILM Cytologya

| Unadjusted, % (95% CI) | Adjusted, % (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Onclarity | HC2 | Onclarity | HC2 |

| ≥CIN2 | ||||

| Sensitivity | 87.5 (78.5-93.1) (n = 70/80) | 82.5 (72.7-89.3) (n = 66/80) | 44.1 (27.7-77.8) | 40.3 (25.2-69.0) |

| Specificity | 48.6 (46.7-50.6) (n = 1,220/2,508) | 52.3 (50.4-54.3) (n = 1,312/2,508) | 92.4 (92.1-92.8) | 93.4 (93.1-93.8) |

| PPV | 5.2 (4.6-5.5) (n = 70/1,358) | 5.2 (4.6-5.7) (n = 66/1,262) | 5.0 (3.9-6.1) | 5.3 (4.1-6.5) |

| NPV | 99.2 (98.6-99.5) (n = 1,220/1,230) | 98.9 (98.4-99.4) (n = 1,312/1,326) | 99.5 (98.9-99.9) | 99.4 (98.9-99.8) |

| PLR | 1.7 (1.5-1.8) | 1.7 (1.5-1.9) | 5.8 (3.7-10.2) | 6.1 (3.8-10.6) |

| NLR | 0.3 (0.1-0.4) | 0.3 (0.2-0.5) | 0.6 (0.2-0.8) | 0.6 (0.3-0.8) |

| Prevalence | 3.1 (n = 80/2,588) | 0.9 | ||

| ≥CIN3 | ||||

| Sensitivity | 93.5 (82.5-97.8) (n = 43/46) | 87.0 (74.3-93.9) (n = 40/46) | 69.5 (42.8-100) | 63.3 (38.7-94.9) |

| Specificity | 48.3 (46.3-50.2) (n = 1,227/2,542) | 51.9 (50.0-53.9) (n = 1,320/2,542) | 92.3 (92.0-92.7) | 93.3 (93.0-93.7) |

| PPV | 3.2 (2.8-3.4) (n = 43/1,358) | 3.2 (2.7-3.5) (n = 40/1,262) | 3.0 (2.2-4.0) | 3.2 (2.3-4.2) |

| NPV | 99.8 (99.3-99.9) (n = 1,227/1,230) | 99.5 (99.1-99.8) (n = 1,320/1,326) | 99.9 (99.7-100) | 99.9 (99.7-100) |

| PLR | 1.8 (1.6-1.9) | 1.8 (1.5-2.0) | 9.1 (5.5-13.2) | 9.5 (5.8-14.4) |

| NLR | 0.1 (0.1-0.4) | 0.3 (0.1-0.5) | 0.3 (0.0-0.6) | 0.4 (0.1-0.7) |

| Prevalence | 1.8 (n = 46/2,588) | 0.3 |

CI, confidence interval; CIN2, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2; CIN3, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3; HC2, digene Hybrid Capture 2 assay; NILM, negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancies; NLR, negative likelihood ratio NPV, negative predictive value; PLR, positive likelihood ratio; PPV, positive predictive value.

aResults represent p16INK4A immunostain-assisted adjudicated histology with HPV results by Onclarity and HC2 assays (paired analysis).

VBA Absolute Risk by HPV Status

VBA absolute baseline risk associated with overall HPV-positive results and with HPV genotypes 16, 18, and 45 was determined for CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher Table 4. Patients with any HPV-positive result had a 5.1% and 3.0% risk for CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher, respectively. There was a trend toward a decreased risk for both disease grades with increasing age. Patients positive for HPV 16 had elevated risk values for both CIN2 or higher (9.3%) and CIN3 or higher (6.9%) compared with overall HPV-positive results. HPV 18 was associated with risk values of 3.9% and 2.6% for CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher, respectively; for HPV 45, the risks were 2.2% and 1.1%, respectively. Absolute risks associated with the 11 other HPV genotypes as a group for CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher were 4.3% and 2.2%, respectively. Stratification by HPV 16/18/45 resulted in risk values for CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher of 6.8% and 4.9%, respectively.

Table 4.

Adjusted Absolute Risk for CIN2 or Higher and CIN3 or Higher Based on HPV Detection in Patients by Onclarity, 30 Years or Older, With NILM Cytology

| Characteristic | Age Group, % (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-39 y (n = 8,663) | 40-49 y (n = 6,829) | ≥50 y (n = 6,792) | Overall (n = 22,284) | |

| ≥CIN2 | ||||

| Overall HPV | 7.7 (5.7-10.1) | 3.2 (1.6-5.0) | 1.5 (0.3-3.0) | 5.1 (3.9-6.3) |

| HPV 16 | 14.1 (7.2-22.8) | 6.3 (0.0-13.6) | 2.9 (0.0-7.3) | 9.3 (5.5-13.7) |

| HPV 18 | 6.5 (0.0-16.2) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 5.0 (0.0-15.8) | 3.9 (0.0-8.4) |

| HPV 45 | 2.2 (0.0-7.5) | 3.2 (0.0-10.5) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 2.2 (0.0-5.4) |

| HPV 16/18 | 12.6 (6.8-19.9) | 4.6 (0.0-10.0) | 3.4 (0.0-7.5) | 8.1 (5.0-11.6) |

| HPV 18/45 | 3.9 (0.0-8.7) | 1.7 (0.0-5.7) | 2.8 (0.0-9.2) | 2.9 (0.6-5.5) |

| HPV 16/18/45 | 10.3 (5.7-16.1) | 4.2 (0.8-8.6) | 2.9 (0.0-6.4) | 6.8 (4.4-9.7) |

| Other 11 hrHPV | 6.6 (4.6-8.7) | 2.8 (1.1-4.8) | 0.9 (0.0-2.4) | 4.3 (3.1-5.5) |

| HPV negative | 0.6 (0.0-1.4) | 0.4 (0.0-1.1) | 0.7 (0.0-1.6) | 0.5 (0.1-1.0) |

| ≥CIN3 | ||||

| Overall HPV | 4.2 (2.9-5.7) | 2.2 (0.8-3.8) | 1.2 (0.3-2.5) | 3.0 (2.1-3.9) |

| HPV 16 | 9.0 (4.6-14.0) | 6.3 (0.0-13.6) | 2.9 (0.0-7.3) | 6.9 (3.9-9.9) |

| HPV 18 | 3.2 (0.0-10.3) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 5.0 (0.0-15.8) | 2.6 (0.0-6.4) |

| HPV 45 | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 3.2 (0.0-10.5) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 1.1 (0.0-3.4) |

| HPV 16/18 | 7.9 (4.1-12.0) | 4.6 (0.0-10.0) | 3.4 (0.0-7.5) | 5.9 (3.5-8.4) |

| HPV 18/45 | 1.3 (0.0-4.1) | 1.7 (0.0-5.7) | 2.8 (0.0-9.2) | 1.7 (0.0-3.8) |

| HPV 16/18/45 | 6.1 (3.2-9.3) | 4.2 (0.8-8.6) | 2.9 (0.0-6.4) | 4.9 (3.0-6.9) |

| Other 11 hrHPV | 3.4 (2.0-5.1) | 1.4 (0.3-2.9) | 0.5 (0.0-1.5) | 2.2 (1.4-3.2) |

| HPV negative | 0.3 (0.0-0.9) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) | 0.1 (0.0-0.3) |

CI, confidence interval; CIN2, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2; CIN3, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3; HPV, human papillomavirus; hrHPV, high-risk human papillomavirus; NILM, negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancies.

Discussion

In the past two decades, the concept of equal management for equal risk has been emphasized in cervical screening and management guidelines.13,23,24,37 Results from this large, prospective, US-based clinical HPV assay validation trial demonstrate that performance of the Onclarity assay for detection of CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher is similar to that of an established, clinically validated HPV assay (HC2). However, unlike HC2, the Onclarity assay’s integrated genotyping capability provides strong evidence that HPV detection and genotyping deliver clinical utility as an adjunct test with cytology during cervical cancer screening. In particular, these baseline results indicate that the Onclarity HPV assay can effectively predict elevated risk for both CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher pathology in women 30 years or older with NILM cytology—a population that, prior to the introduction of cotesting, was considered extremely low risk. Finally, these results show that the differential stratification of risk through the detection of individual genotypes (HPV 16, 18, or 45) has the potential to affect patient care pathways in this population.

The demographic makeup and HPV prevalence reported here are similar to demographics previously reported in studies involving other FDA-cleared HPV assays. For example, the Addressing the Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics (ATHENA) study population was demographically similar, with a mean age of 44.9 years and an ethnoracial makeup of white, 84.3%; African American, 13.0%; Asian, 1.4%; and Hispanic/Latino, 17.8%.29 Here, the prevalence of overall HPV (7.9%) was similar to prevalence values reported for other FDA-approved HPV assays in NILM populations Table 5, including the cobas HPV (Roche)40 and Aptima HPV (Hologic)38,39 assays, which reported a prevalence of 6.7% (n = 32,260) and 5.0% (n = 10,871), respectively. For individual HPV genotypes HPV 16 and 18, the ATHENA trial reported similar prevalence values for both HPV 16 (1.0%) and HPV 18 (0.5%) as those reported here.

Table 5.

Comparison of Different Regulatory Trials Involving Women With NILM Cytology (≥30 Years of Age)a

| Characteristic | Aptimab,38,39 | Cobasc,29,40 | Onclarity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytology media | ThinPrep | ThinPrep | SurePath |

| No. of patients | 10,871 | 32,260 | 22,284 |

| Mean age, y | 44.2 | 44.9 | 43.9 |

| HPV+, % | 5.0 | 6.7 | 7.9 |

| HPV 16+, % | 0.4d | 1.0 | 1.5 |

| HPV 18+, % | NR | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| HPV 16/18+, % | NR | 1.5 | 1.9 |

| HPV 45+, % | NR | NR | 0.5 |

| HPV 18/45+, % | 0.4d | NR | 0.9 |

| CIN2, No. | 9 | 51e | 34 |

| ≥CIN3, No. | 11 | 80e | 46 |

| No. of cancer cases | 3 | NR | 5f |

| For ≥CIN2, % (95% CI) | |||

| Sensitivity | 75.0 (53.1-88.8) | 83.2 (75.9-88.6)e | 87.5 (78.5-93.1) |

| Specificity | 62.6 (59.2-65.9) | 60.4 (58.9-61.9)e | 48.6 (46.7-50.6) |

| For ≥CIN3, % (95% CI) | |||

| Sensitivity | 90.9 (62.3-98.4) | 90.0 (81.5-94.8)e | 93.5 (82.5-97.8) |

| Specificity | 62.4 (59.0-65.7) | 60.0 (58.5-61.5)e | 48.3 (46.3-50.2) |

CI, confidence interval; CIN2, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2; CIN3, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3; HPV, human papillomavirus; NILM, negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancies; NR, not reported.

aBaseline data unless otherwise indicated.

bData obtained from Aptima package insert unless otherwise noted.

cData obtained from Wright et al29 unless otherwise noted.

dBased on Aptima 16, 18/45 package insert (n = 10,846).

eData obtained from cobas package insert.

fIndicates adenocarcinoma in situ cases.

In accordance with FDA guidance for establishing the clinical utility of an HPV assay for use in screening, the performance for the detection of CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher was conducted for Onclarity and compared with that for HC2. For all performance values measured (sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, PLR, and NLR), Onclarity was largely in agreement with HC2. VBA was applied to the data to account for patients not assigned to colposcopy. As expected, VBA led to lower sensitivities and higher specificities for CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher compared with unadjusted values. Similar results have been shown in previous studies involving HPV screening for detection of cervical disease.41,42 Similar to previous studies,29 VBA likely deflated sensitivity due to an overestimation of disease prevalence in the large group of NILM/HPV-negative patients who were randomly not assigned to colposcopy. However, VBA adjusted values for Onclarity were similar to those obtained for HC2, indicating that Onclarity is a clinically valid assay in this screening population.

HPV infection is necessary for the development of cervical cancer, and several prospective and cross-sectional studies have shown that including HPV in a cotesting regimen with cytology can both increase concurrent detection of cervical disease and decrease its occurrence in subsequent rounds of screening.6,16-18,20,27,29,43-46 As a result, guidelines recommended an extension in the screening interval for women 30 years or older from 3 years with cytology only to 5 years when using cotesting. This reflects the improvement in NPV conferred by a negative HPV result and is accompanied by increased assurance for women undergoing cervical cancer screening. Although the 5-year interval for HPV-negative women has been controversial, it continues to be recommended in the recent US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines.11,47 Here, the Onclarity assay resulted in an NPV of 99.8% for CIN3 or higher, which is consistent with previous reports27,28 and supports an extended screening interval based on a negative cotesting result.

According to current US guidelines, acceptable actions following an HPV-positive result in the NILM population during screening include either repeat cotesting after 1 year or concurrent HPV genotyping. For the latter step, HPV 16/18–positive women would be directed to colposcopy, whereas HPV 16/18–negative women would undergo repeat cotesting in 1 year. An HPV-positive result with the Onclarity assay in this screening population imparted a VBA risk for CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher of 5.1% and 3.0%, respectively, compared with 0.5% and 0.1%, respectively, as determined in HPV-negative individuals. These results are similar to risk values determined for CIN2 or higher and CIN3 or higher reported from the ATHENA trial, which spawned the aforementioned use of 16/18 partial genotyping.29 Genotyping for HPV 16 resulted in a higher detection of risk for both CIN2 or higher (9.3% for HPV 16 vs 5.1% for overall HPV) and CIN3 or higher (6.9% for HPV 16 vs 3.0% for overall HPV) compared with risk detected by any of the 14 pooled genotypes (inclusive of HPV 16). Similar results were obtained when assessing risk associated with HPV 16/18 genotyping, although this is due to the weighting of both prevalence and risk of HPV 16. Thus, risk assessment through partial genotyping by the Onclarity assay in this study supports established screening algorithms and demonstrates its utility for the triage of HPV-positive women in the NILM population to either delayed repeat cotesting or a referral to colposcopy.

The Onclarity assay is the first HPV DNA test indicated to individually detect HPV 45, in addition to HPV 16 and 18, for cotesting. Although HPV 18 and 45 are prevalent in 5% to 8% of squamous cell carcinomas and 12% to 32% of adenocarcinoma/adenosquamous cell carcinomas,2 neither had individual risks for CIN2 or higher or CIN3 or higher that exceeded those for the 14 pooled genotypes in this study. Individual risks associated with HPV 18 and 45 were similar to those for the 11 pooled genotypes exclusive of HPV 16/18/45. Women who are HPV 18 or 45 positive have demonstrated enrichment of prevalence in invasive squamous cell cancer, especially adenocarcinoma, compared with women with the 11 other HPV genotypes (exclusive of 16/18/45) in cross-sectional studies.48-50 Adenocarcinoma and adenocarcinoma in situ associated with HPV 18 and 45 are often found originating in the endocervical canal2,51 and are usually cytologically or colposcopically undetectable.51 Therefore, guidelines that recommend individual genotyping with HPV 18 (and perhaps in the future some cases with HPV 45), when cotesting or using primary screening, are based in part on the ability to detect occult glandular neoplasia associated with these two genotypes (from cross-sectional studies), not the risk of CIN2 or higher or CIN3 or higher (from prospective studies). Future considerations for risk-based colposcopy procedures involving HPV 18–positive and HPV 45–positive women may include the performance of an ECC, regardless of whether a punch biopsy is performed.

In summary, these findings validate the Onclarity HPV assay for clinical detection of 14 high-risk HPV genotypes as a pooled result and detection of individual genotypes 16, 18, and 45 in women 30 years or older with NILM cytology. The performance values and risk detection obtained using Onclarity establish its utility for use within the current US cervical cancer screening guidelines for cotesting. The CIN3 or higher risk values for HPV 16, HPV 16/18, and HPV 16/18/45 in women with NILM cytology, determined here, exceed the 5-year threshold (5.2%) for CIN3 or higher. Furthermore, the results described here are in agreement with established risk thresholds for non–HPV 16/18, HPV-positive results that direct repeat testing at 12 months, and a 5-year screening interval following a negative result with HPV testing.52 Thus, Onclarity conforms to the parameters for HPV detection in the currently accepted cotesting screening strategy.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Jeff Andrews, MD (Becton, Dickinson and Company, BD Life Sciences–Diagnostic Systems), for his thoughtful comments and critique of this manuscript and Devin S. Gary, PhD (Becton, Dickinson and Company, BD Life Sciences–Diagnostic Systems), for his contributions to the content of this manuscript and editorial assistance. We also thank Stanley Chao (Becton, Dickinson and Company, BD Life Sciences–Diagnostic Systems) for his statistical support. The individuals acknowledged here have no additional funding or additional compensation to disclose.

This work was supported by Becton, Dickinson and Company, BD Life Sciences–Diagnostic Systems.

Dr Stoler serves as a consultant in clinical trial design and as an expert pathologist for HPV vaccine and/or diagnostic trials for Becton, Dickinson and Company, BD Life Sciences–Diagnostic Systems; Roche; Inovio Pharmaceuticals; and Merck and as a speaker for Roche and Becton, Dickinson and Company, BD Life Sciences–Diagnostic Systems. Dr Wright serves as a consultant in clinical trial design and as an expert pathologist for HPV vaccine and/or diagnostic trials for Becton, Dickinson and Company, BD Life Sciences–Diagnostic Systems; Roche; and Inovio Pharmaceuticals and as a speaker for Roche and Becton, Dickinson and Company, BD Life Sciences–Diagnostic Systems. Becton, Dickinson and Co. employees who are also authors played the following roles during the study and development of the article: V.P. facilitated data acquisition and revision of the manuscript; K.Y., K.E., and S.K. facilitated conception and design of the study, data acquisition and interpretation, and drafting and revision of the manuscript; C.C. facilitated study conception and design, as well as manuscript revision. All authors provided final approval of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of this work.

Clinical trial registry URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01944722.

References

- 1. de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, et al. . Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Sanjose S, Quint WG, Alemany L, et al. ; Retrospective International Survey and HPV Time Trends Study Group Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1048-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63:1-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, et al. . Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2007;370:890-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. . Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kitchener HC, Gilham C, Sargent A, et al. . A comparison of HPV DNA testing and liquid based cytology over three rounds of primary cervical screening: extended follow up in the ARTISTIC trial. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:864-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Human papillomaviruses. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100B:255-314. [Google Scholar]

- 8. von Karsa L, Anttila A, Ronco G, et al. . Cancer screening in the European Union: report on the implementation of the Council Recommendation on Cancer Screening 2008. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/genetics/documents/cancer_screening.pdf Accessed November 10, 2017.

- 9. Wentzensen N, Arbyn M, Berkhof J, et al. . Eurogin 2016 Roadmap: how HPV knowledge is changing screening practice. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:2192-2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guidelines for preventative activities in general practice: Edition 9.5 Cervical Cancer https://www.racgp.org.au/your-practice/guidelines/redbook/9-early-detection-of-cancers/95-cervical-cancer/ Accessed November 2, 2017.

- 11. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. . Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:178-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al. . 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(suppl 1):S1-S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. ; American Cancer Society; American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology; American Society for Clinical Pathology American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137:516-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schiffman M, Yu K, Zuna R, et al. . Proof-of-principle study of a novel cervical screening and triage strategy: computer-analyzed cytology to decide which HPV-positive women are likely to have ≥CIN2. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:718-725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. ; New Technologies for Cervical Cancer Screening (NTCC) Working Group Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. . Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al. . Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests to screen for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1589-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kitchener HC, Almonte M, Thomson C, et al. . HPV testing in combination with liquid-based cytology in primary cervical screening (ARTISTIC): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:672-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bulkmans NW, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. . Human papillomavirus DNA testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 and cancer: 5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled implementation trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1764-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wentzensen N, Schiffman M, Palmer T, et al. . Triage of HPV positive women in cervical cancer screening. J Clin Virol. 2016;76(suppl 1):S49-S55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, et al. . 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:346-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, et al. . Five-year risks of CIN 3+ and cervical cancer among women with HPV testing of ASC-US Pap results. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(suppl 1):S36-S42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, et al. . Benchmarking CIN 3+ risk as the basis for incorporating HPV and Pap cotesting into cervical screening and management guidelines. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(suppl 1):S28-S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arbyn M, Sasieni P, Meijer CJ, et al. . Clinical applications of HPV testing: a summary of meta-analyses. Vaccine. 2006;24(suppl 3):S3/78-S89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Castle PE, Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, et al. . Performance of carcinogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and HPV16 or HPV18 genotyping for cervical cancer screening of women aged 25 years and older: a subanalysis of the ATHENA study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:880-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dillner J, Rebolj M, Birembaut P, et al. . Long term predictive values of cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: joint European cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 2008;337:a1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. . Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:189-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Sharma A, et al. ; ATHENA (Addressing THE Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics) Study Group Evaluation of HPV-16 and HPV-18 genotyping for the triage of women with high-risk HPV+ cytology-negative results. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:578-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schiffman M, Boyle S, Raine-Bennett T, et al. . The role of human papillomavirus genotyping in cervical cancer screening: a large-scale evaluation of the cobas HPV test. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:1304-1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wright TC Jr, Behrens CM, Ranger-Moore J, et al. . Triaging HPV-positive women with p16/Ki-67 dual-stained cytology: results from a sub-study nested into the ATHENA trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144:51-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, Parvu V, et al. . The Onclarity human papillomavirus trial: design, methods, and baseline results. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;149:498-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Parvu V, et al. . Detection of cervical neoplasia by human papillomavirus testing in an atypical squamous cells-undetermined significance population: results of the Becton Dickinson Onclarity trial. Am J Clin Pathol. 2019;151:53-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, et al. . The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287:2114-2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT, et al. ; Members of LAST Project Work Groups The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1266-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Little RJ, Rubin DB.. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gage JC, Hunt WC, Schiffman M, et al. ; New Mexico HPV Pap Registry Steering Committee Similar risk patterns after cervical screening in two large U.S. Populations: implications for clinical guidelines. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1248-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hologic. Aptima HPV Assay [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Hologic; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hologic. APTIMA® HPV 16 18/45 Genotype Assay [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Hologic; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Roche Diagnostics. Cobas 4800 HPV test [package insert, CE]. Indianapolis, IN: Roche Diagnostics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kulasingam SL, Hughes JP, Kiviat NB, et al. . Evaluation of human papillomavirus testing in primary screening for cervical abnormalities: comparison of sensitivity, specificity, and frequency of referral. JAMA. 2002;288: 1749-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, et al. ; Canadian Cervical Cancer Screening Trial Study Group Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1579-1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kjaer S, Høgdall E, Frederiksen K, et al. . The absolute risk of cervical abnormalities in high-risk human papillomavirus-positive, cytologically normal women over a 10-year period. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10630-10636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfstrom KM, et al. . Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383:524-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sherman ME, Lorincz AT, Scott DR, et al. . Baseline cytology, human papillomavirus testing, and risk for cervical neoplasia: a 10-year cohort analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:46-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wheeler CM, Hunt WC, Cuzick J, et al. ; New Mexico HPV Pap Registry Steering Committee The influence of type-specific human papillomavirus infections on the detection of cervical precancer and cancer: a population-based study of opportunistic cervical screening in the United States. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:624-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kinney W, Wright TC, Dinkelspiel HE, et al. . Increased cervical cancer risk associated with screening at longer intervals. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:311-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bekkers RL, Bulten J, Wiersma-van Tilburg A, et al. . Coexisting high-grade glandular and squamous cervical lesions and human papillomavirus infections. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:886-890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sundström K, Eloranta S, Sparén P, et al. . Prospective study of human papillomavirus (HPV) types, HPV persistence, and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:2469-2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dahlström LA, Ylitalo N, Sundström K, et al. . Prospective study of human papillomavirus and risk of cervical adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:1923-1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pirog EC, Kleter B, Olgac S, et al. . Prevalence of human papillomavirus DNA in different histological subtypes of cervical adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1055-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, et al. . Five-year risks of CIN 2+ and CIN 3+ among women with HPV-positive and HPV-negative LSIL Pap results. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(suppl 1):S43-S49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]