Abstract

This population-based, case-control study analyzes the potential barriers to cancer care resources in rural Honduras in a cohort of patients with gastric cancer.

Cancer is a growing burden on low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1 By 2030, 70% of the cancer burden will occur in LMICs and be driven by 7 major cancers, including gastric cancer.2 Gastric cancer is an appropriate model to assess barriers to cancer care because it is the third leading cause of global cancer mortality and the leading cause in regions such as the Central America-4 (CA-4): Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. The CA-4 is the largest LMIC region in the Western hemisphere with 36 million inhabitants, half of whom live in rural areas that lack regional treatment capacity.2,3,4,5,6 We describe treatment patterns of gastric cancer care in rural Honduras, a high-incidence region.4

Methods

We analyzed factors associated with treatment and gastric cancer care in rural western Honduras in a cohort of patients with gastric cancer in an ongoing population-based, case-control study with an endoscopy and pathology registry from 2002 through 2015.4 The nascent population-based cancer registry data were used to assess completeness for 2013 through 2015.5 An active follow-up protocol was used in 2016 during household visits in rural and remote areas by interviewing the patient and/or relatives. Given the high mortality, most interviews were conducted with family members. Surveys were administered by trained interviewers with tablets using Research Electronic Data Capture. Treatment was defined as either receiving chemotherapy, undergoing surgical resection, or both. Data were obtained on alternative treatments. Socioeconomic status was estimated via unsatisfied basic needs assessment. Travel time (eg, walking, bus) was used as a surrogate for distance to treatment. Multivariable logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals to identify factors (Figure) associated with treatment (STATA, version 14). Institutional review board approvals were obtained from Vanderbilt University and the Honduras Ministry of Health. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant.

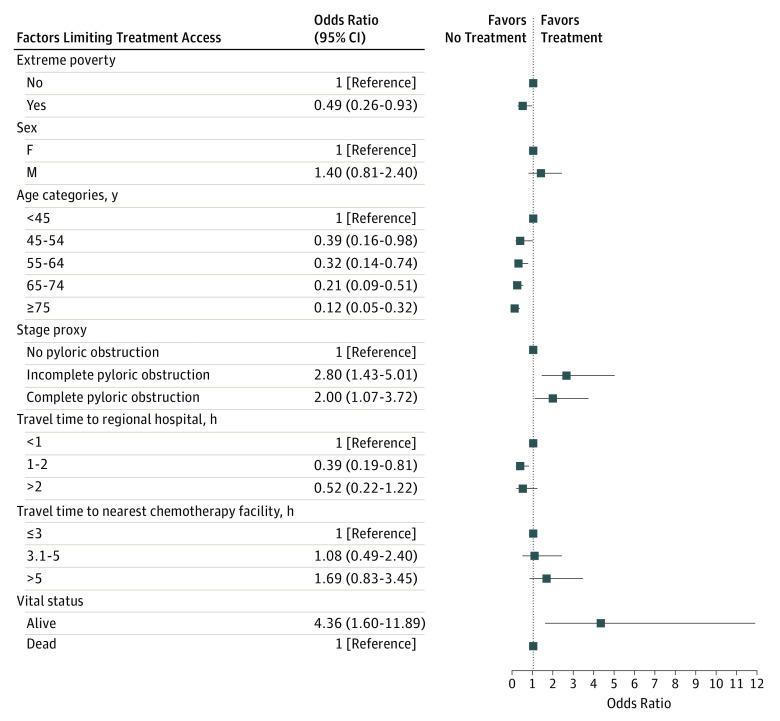

Figure. Factors Limiting Access to Gastric Cancer Treatment in Western Honduras.

Risk factors independently associated with limited access to cancer treatment were identified using multivariate logistic regression models for cases diagnosed between 2002 and 2015. Complete data were available for 55.5% of cases. All variables included in the model are shown in the figure. The vertical line represents an odds ratio (OR) of 1.00, the reference category for factors limiting treatment access (OR, <1.00).

Results

The study identified 741 patients with gastric cancer (487 [65.7%] male) and a mean (SD) age of 63 (range, 20-97) years (Table). Of those patients, 738 (99.6%) had histologic confirmation (335 [45.2%] intestinal, 320 [43.2%] diffuse) and 580 (78.3%) received household visits. Of the patients who received household visits, 497 had complete treatment information: 123 of 497 (24.7%) received treatment; 113 of 496 (22.8%) underwent surgical resection; and 42 of 497 (8.5%) received chemotherapy. Patients who received treatment were more likely to be alive at follow-up (OR, 4.29; 95% CI, 1.57-11.73) (Figure). Patients with extreme poverty (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.26-0.93) and those older than 55 years (OR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.15-0.80) were less likely to receive treatment. The 79 patients (17.3%) who sought alternative therapies most commonly chose Aloe vera extract, herbs, and snakeskin powder. Patients with greater travel time to the regional treatment facility were less likely to undergo treatment.

Table. Overview of Gastric Cancer Treatment in Western Honduras, 2002-2015.

| Characteristics | Patients, No. (%) (N = 741) |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD), y | 63.29 (13.52) |

| Age range, y | |

| <45 | 65 (8.8) |

| 45-54 | 116 (15.7) |

| 55-64 | 199 (26.9) |

| 65-74 | 191 (25.8) |

| ≥75 | 168 (22.7) |

| Household poverty index (UBN) | |

| No (0-1) | 374 (64.5) |

| Yes (2-4) | 206 (35.5) |

| Clinical | |

| ICD-O-3 classification | |

| Adenocarcinoma, intestinal type | 335 (45.2) |

| Adenocarcinoma, diffuse type | 320 (43.2) |

| Adenocarcinoma with mixed subtypes | 54 (7.3) |

| Other (carcinoid, squamous, NOS) | 32 (4.1) |

| Stage proxy (degree of pyloric obstruction) | |

| No pyloric obstruction | 315 (42.5) |

| Incomplete pyloric obstruction | 129 (17.4) |

| Complete pyloric obstruction | 164 (22.1) |

| Unknown | 133 (17.9) |

| Patients receiving treatment | |

| No | 374 (50.5) |

| Yes | 123 (16.6) |

| Unknown | 244 (32.9) |

| Treatment modality | |

| Chemotherapy | 42/497 (8.5) |

| Surgery | 113/496 (22.9) |

| Radiotherapy | 13/494 (2.6) |

| Alternative treatment | 79/457 (17.3) |

| Follow-up | |

| Active follow-up with interview | |

| No | 161 (21.7) |

| Yes | 580 (78.3) |

| Person providing follow-up information | |

| Patient | 17 (2.9) |

| Relative | 438 (75.6) |

| Nonrelative | 124 (21.4) |

| Vital status | |

| Alive | 33 (4.9) |

| Dead | 635 (95.1) |

Abbreviations: ICD-O-3, International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Revision; NOS, not otherwise specified; UBN, unsatisfied basic needs.

Discussion

Barriers to cancer care are substantial in the rural LMIC setting of Central America. Only 1 in 5 patients received curative or palliative surgical treatment. One in 12 patients received chemotherapy, which is not available in western Honduras. Living in households below the regional poverty standard was a barrier to treatment.

Limitations to our study include case ascertainment and the absence of certain clinical variables, which are a challenge in LMICs. Staging is not routine, and we used surrogate clinical assessments (eg, pyloric obstruction). Regardless, we were able to achieve follow-up of most cases in our cohort, and completeness was verified by correlation with population-based cancer registry data and the stability of incident cases per year.

To our knowledge, this is the first study in a rural and/or LMIC setting in Latin America. Our findings may be generalizable to rural communities in the CA-4 region and may have implications for the 5 million US immigrants from the CA-4 region. Health ministries are encouraged to develop national cancer control plans that prioritize access to cancer care and promote the establishment of cost-effective cancer prevention programs in high-risk areas.5

References

- 1.World Health Organization United Nations high-level meeting on noncommunicable disease prevention and control. 2017. http://www.who.int/nmh/events/un_ncd_summit2011/en/. Accessed September 1, 2017.

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed August 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, et al. ; Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration . Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):524-548. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominguez RL, Crockett SD, Lund JL, et al. Gastric cancer incidence estimation in a resource-limited nation: use of endoscopy registry methodology. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(2):233-239. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0109-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piñeros M, Frech S, Frazier L, et al. Advancing reliable data for cancer control in the Central America Four region. J Glob Oncol. 2017. http://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/JGO.2016.008227. Published March 6, 2017. Accessed May 11, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cazap E, Magrath I, Kingham TP, Elzawawy A. Structural barriers to diagnosis and treatment of cancer in low- and middle-income countries: the urgent need for scaling up. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(1):14-19. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.9189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]