Abstract

Background

Acute abdominal pain (AAP) comprises up to 10% of all emergency department (ED) visits. Current pain management practice is moving toward multi-modal analgesia regimens that decrease opioid use.

Objective

This project sought to determine whether, in patients with AAP (population), does administration of butyrophenone antipsychotics (intervention) compared to placebo, usual care, or opiates alone (comparisons) improve analgesia or decrease opiate consumption (outcomes)?

Methods

A structured search was performed in Cochrane CENTRAL, CINAHL, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Directory of Open Access Journals, Embase, IEEE-Xplorer, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, Magiran, PubMed, Scientific Information Database, Scopus, TÜBİTAK ULAKBİM, and Web of Science. Clinical trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry), relevant bibliographies, and conference proceedings were also searched. Searches were not limited by date, language, or publication status. Studies eligible for inclusion were prospective randomized clinical trials enrolling patients (age ≥18 years) with AAP treated in acute care environments (ED, intensive care unit, postoperative). The butyrophenone must have been administered either intravenously or intra-muscularly. Comparison groups included placebo, opiate only, corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or acetaminophen.

Results

We identified 7,217 references. Six studies met inclusion criteria. One study assessed ED patients with AAP associated with gastroparesis, whereas five studies assessed patients with postoperative AAP: abdominal hysterectomy (n=4), sleeve gastrectomy (n=1). Three of four studies found improvements in pain intensity with butyrophenone use. Three of five studies reported no change in postoperative opiate consumption, while two reported a decrease. One ED study reported no change in patient satisfaction, while one postoperative study reported improved satisfaction scores. Both extrapyramidal side effects (n=3) and sedation (n=3) were reported as unchanged.

Conclusion

Based on available evidence, we cannot draw a conclusion on the efficacy or benefit of neuroleptanalgesia in the management of patients with AAP. However, preliminary data suggest that it may improve analgesia and decrease opiate consumption.

Keywords: neuroleptanalgesia, butryophenone, abdominal pain, haloperidol, droperidol

Background

Description of the condition

Acute abdominal pain (AAP): emergency medicine

AAP is one of the most common chief complaints of patients in the emergency department (ED), constituting 6%–10% of all visits,1,2 and the incidence is rising.3 The average ED length-of-stay (LOS) is over 6 hours, with admission rates approaching 25%.1,2 The majority (44%–59%) of patients are treated with an opiate/opioid analgesic, with morphine being the single most commonly administered analgesic (20%).4,5 In addition, inadequate pain management (oligoanalgesia) in the ED is a common problem.6 Only 50%–66% of ED patients with abdominal pain receive analgesia.3,4,7–9 Average analgesia wait times vary considerably, with one study reporting mean analgesia wait times of 4.1 hours for mild pain, 1.85 hours for moderate pain, and 1.37 hours for severe pain.10 This time to analgesia may itself be longer than the entire mean ED LOS for all comers.2,3,11 Timely analgesic administration has been shown to improve patient care and reduced ED LOS.12 Many factors contribute to ED oligoanalgesia, including the myth that early analgesia delays diagnosis of abdominal pain, despite evidence to the contrary.13–15 Commonly administered opioid analgesics also create a range of problems, from underuse (oligoanalgesia/opiophobia) and undesirable side effects to misuse (opioid crisis).16 A concerning observation is that 25% of AAP patients treated with an opioid are discharged with a prescription for one. Current pain management practice is moving toward recent United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) goals that emphasize adequate pain control with increased use of multimodal pain regimens and decreased opioid use.17 Insufficient data regarding the efficacy of alternative regimens and their side effect profiles have hampered efforts to move away from heavy opiate regimens.18,19

AAP: postoperative

According to data from the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 6 of the 15 most common operating room procedures performed during hospital stays in 2012 were abdominal procedures, including 1) cholecystectomy and common duct exploration, 2) hysterectomy (abdominal and vaginal), 3) colorectal resection, 4) excision, lysis of peritoneal adhesions, 5) appendectomy, and 6) oophorectomy (unilateral and bilateral).20 These accounted for accounting for 1.85 million hospital stays.20 Evidence suggests that postoperative patients frequently need less opiates on discharge than that are prescribed, leaving excess opioid for potential diversion.21–23 Moreover, 5% of young adults continue to receive opioid refills long after surgery.24 Studies have demonstrated that opioid sparing postoperative analgesia techniques may be effective following abdominal surgery. For example, treatment with acetaminophen (1,000 mg intravenous [IV] every 6 hours or 650 mg IV every 4 hours) or non-steroidal agents has been shown to lower opioid consumption and the need for rescue medication following abdominal surgery, with greater effects demonstrated by combining these agents.25–27 In addition, IV lidocaine has been shown to hasten patient rehabilitation and shorten hospital stays following abdominal surgery.28 Dipyrone (metamazol) has been shown to have opiate sparing effects for abdominal pain in the postoperative setting.29 It remains unclear which (if any) opioid sparing postoperative analgesia regimens alter postoperative opioid requirements post-discharge.

Description of the intervention

How the intervention might work

Neuroleptanalgesia involves combining an opiate with a neuroleptic drug (eg, haloperidol and droperidol) for analgesia. The most commonly used neuroleptics in the USA are butyrophenones. Butyrophenones are a subclass of neuroleptic antipsychotic drugs. Haloperidol, which was introduced in 1957 and was approved by the US FDA in 1967, is a derivative of meperidine (Demerol) and is the most widely used butyrophenone in the USA. Although once widely used, droperidol (introduced in 1961, FDA approved in 1970) is now unavailable due to a black box warning and drug shortages. A complete list of butyrophenone medications is listed in Table 1. Benperidol is available in Europe only, and azaperone is approved for use in veterinary settings only at this time.

Table 1.

Marketed butyrophenones with approval status and indication

| Generic name | Trade name | Approved for human use? | Approved for use in the USA? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azaperone | Azaperona, Stresnil, Fluoperidol, Suicalm, Eucalmyl, Sedaperone vet | No | Yes | Approved for veterinary use only |

| Benperidol | Anquil, Glianimon | Yes | No | Most potent neuroleptic on the European market; 150%–200% potency of haloperidol |

| Bromperidol | Brimidol, Bromodol, Erodium, Impromen | Yes | No | Only available in Belgium, German, the Netherlands, and Italy |

| Cinuperone | Yes | No | ||

| Droperidol | Droleptan, Dridol, Inapsine, Xomolix, Innovar (combination with fentanyl) | Yes | Yes | US FDA Black Box warning for torsade’s de pointesa |

| Fluanisone | Haloanison, Sedalande, Anti-Pica, Metorin | Yes | No | Veterinary use; used for agitation in humans, but no longer marketed; was available in Belgium, France, Germany, and Switzerland |

| Haloperidol | Haldol, Peridol | Yes | Yes | |

| Lenperone | Elanone-V | Yes | No | Veterinary use |

| Moperone | Luvatren, Methylperidol, Meperon, Luvatrena | Yes | No | No longer available on market. Previously available in Japan, Sweden, and Switzerland |

| Nonaperone | Nonaperonum, Nonaperona | Yes | No | Only available in India. |

| Pipamperone | Dipiperone, Dipiperal, Piperonil, Piperonyl, Propitan | Yes | No | Also known by non-trade names including carpiperone and floropipamide or fluoropipamide, and as floropipamide hydrochloride |

| Spiperone | Spiroperidol, Spiropitan | Yes | No | Marketed in Japan |

| Timiperone | Tolopelon | Yes | No | Marketed in Japan |

| Trifluperidol | Psychoperidol, Triperidol, Trisedyl | Yes | No | Only available in India. Previously available in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, and the UK |

Notes:

In 2001, the US FDA changed the labeling requirements for droperidol injection to include a Black Box Warning, citing concerns of QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. The evidence for this is disputed, with nine reported cases of torsades de pointes in 30 years and all of those having received doses more than 5 mg. QT prolongation is a dose-related effect, and it appears that droperidol is not a significant risk in low doses. A study in 2015 showed that droperidol is relatively safe and effective for the management of violent and aggressive adult patients in hospital emergency departments in doses of 10 mg and above and that there was no increased risk of QT prolongation and torsades de pointes.

Abbreviation: US FDA, United States Food and Drug Administration.

Haloperidol is a first-generation antipsychotic that exerts its effects via non-selectively blocking postsynaptic dopaminergic D2 receptors in the brain. It may also have effects by binding D1 dopamine, 5-HT2 serotonin, H1 histamine, and alpha2 adrenergic receptors in the central nervous system.30,31 The use of butyrophenones for analgesia dates back to the 1970s.32,33 It is believed that haloperidol exerts analgesic effects and synergistic analgesic effects, through the modulation of NMDA-receptors as well as sigma-1 receptors.34–36 After a single dose of 3 mg haloperidol, sigma-1 receptor antagonists will mimic opioid efficacy by blocking pain perception without unwanted opioid side effects.37 It has also been suggested that they decrease pain sensitivity via NMDA inhibition, thereby inhibiting the pain wind-up and opioid hyperalgesia phenomenon.38,39 Droperidol has some additional mechanisms of action; however, we will defer this discussion as the drug is not currently clinically available.

Haloperidol is metabolized by CYP 3A4, 1A2, and 2D6, therefore drug interactions will arise with any other medication that would induce or inhibit these hepatic enzymes, most notably carbamazepine, ketoconazole, and rifampin.40,41 Common side effects from short-term haloperidol administration include sedation and anticholinergic effects. Less common effects include orthostatic hypotension and tachycardia, although hypotension is less common with haloperidol than droperidol due to less alpha blocking effect.42 Uncommon adverse effects include pruritis, diarrhea, and electrocardiogram changes. QT-prolongation is a known side effect, thus concurrent administration with other QT-prolonging medications in patients with a prolonged QT or electrolyte abnormalities (low potassium or magnesium) should be avoided to prevent dysrhythmia (most notably torsades de pointes).41 Coadministration with other neuroleptics or dopaminergic agents may precipitate extrapyramidal symptoms and possibly even neuroleptic malignant syndrome.31,41

Whether all butyrophenones have similar analgesic qualities is not known as there are no studies that directly compare individual butyrophenones with each other. However, several studies have demonstrated clinically significant pain relief and/or decreased opioid consumption with the administration of haloperidol and droperidol.30,43–45 In healthy volunteers, droperidol potentiated analgesic effects of fentanyl.46 Trials of ED patients with abdominal pain have shown that haloperidol may improve analgesia and reduce opiate consumption, nausea, and admission rates.34,47–53 Similarly, droperidol has been shown to reduce pain in patients presenting with biliary colic,54 postoperative patients following urologic procedures,55 and during gastrointestinal endoscopy.56,57 Several studies have reported improvements in postoperative pain and reduced opiate consumption with both haloperidol and droperidol.58–60 Moreover, haloperidol has shown efficacy in patients with chronic abdominal pain,61 chronic functional intestinal disorders,62 and pain in the setting of opiate dependence.47 The onset of action of haloperidol and droperidol is within 20 and 10 minutes, respectively, both with peaks around 30 minutes. The notable analgesia duration for each is from 0.5 to 3 hours post-administration.31 Although tolerance to haloperidol has been described for catalepsy and behavioral effects, butyrophenone drug tolerance for pain has not been reported.59 The dosing of haloperidol is typically 5 mg. One study found no additional benefit for postoperative pain for Haldol 10 mg over 5 mg dosing.63 Whether administration route alters efficacy is unclear.

Why it is important to do this review?

In the late 1990s, the medical community began to prescribe opioids at a greater rate, in part due to advertising and misguidance from pharmaceutical companies coupled with the public awareness of health care failure to adequately address pain.64,65 This spurred a widespread misuse of opioids, including prescription drugs, heroin, and synthetics. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there was a quadrupling in the number of opioid prescriptions from 1999 to 2010, with a corresponding quadrupling of opioid-related deaths over the same period.65 The link between prescribing rates and overdose deaths appears to be directly related to maximum prescribed daily doses and not to regularly scheduled and as-needed doses.65

This is not to say that opioid analgesics do not serve an important role in the treatment of acute and chronic pain, but misuse has become a public health crisis. The USA has become the prescriber of 80% of global prescribed narcotics; ≥50 times more than the rest of the world combined.66,67 Nearly 25% of prescribed opioid users misuse their prescription, and 115 Americans die daily from opioid overdose.68–70 Global consumption of opioids has more than tripled over the past 20 years with a majority of use in North America and Europe.71 Opiates comprise 58% of analgesic use in the ED,5 with abdominal pain accounting for 10%–44% of ED opioid administration.4,72–75 Administration of opioids (with later prescription) in the ED has been linked to an increased risk of becoming a recurrent opioid user.72 Identifying safe and effective analgesia techniques that limit narcotic consumption and prescription is needed. We investigated the evidence for using neuroleptanalgesia as an effective opioid sparing alternative to analgesia in patients with AAP.

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review was to address the following research question: in patients with AAP (population), does administration of butyrophenone antipsychotics (intervention) compared to placebo, usual care, or opiates alone (comparisons) improve analgesia and decrease opiate consumption (outcomes)?

Methods

This systematic review followed the steps outlined in the PRISMA. A systematic review protocol was developed before conducting the project. The systematic review was registered at the International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO, registration number: CRD42018104226).

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Prospective randomized trials were included.

Types of participants

Adult patients being treated for AAP in the ED, intensive care unit (ICU), or immediate postoperative setting were included.

Types of interventions

We assessed the analgesic effects of butyrophenone (haloperidol, droperidol) antipsychotics administered by either intravenous or intramuscular route. For all endpoints with available data, we compared 1) butyrophenone alone vs placebo or conventional therapy, 2) butyrophenone alone vs opiate alone, and 3) butyrophenone plus opiate vs opiate alone. For selected variables (eg, opiate consumption), we also analyzed the following data separately: 1) ED patients only and 2) postoperative patients only.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes included 1) adequate pain control using any validated pain scale used by the original trials and 2) opiate consumption (milligrams of morphine sulfate or morphine equivalents) administered to achieve pain control.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were 1) patient satisfaction with analgesia, 2) admission rates for ED patients, 3) ED LOS, 4) hospital LOS, and 5) side effects (extrapyramidal, akathisia, and cardiac).

Search methods for the identification of studies

Electronic searches

A librarian who was specialized in systematic reviews and meta-analysis developed a structured search strategy for Cochrane CENTRAL, CINAHL, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), Embase, IEEE-Xplorer, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), Magiran, PubMed, Scientific Information Database (SID), Scopus, TÜBİTAK ULAKBİM, and Web of Science. Bibliographies of the relevant articles were also searched. The searches were not limited by date, language, or publication status.

Searching other resources

To limit publication bias, searches were conducted in Clinical-Trials.gov website, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP), and the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR). Abstracts of the conference proceedings of the relevant disciplines were also searched (past 5 years) to identify any presented but not published abstracts. We also contacted the experts in the field and inquired about the possible ongoing trials that might not have been identified in our search. Unpublished or “in press” trials that met inclusion criteria were eligible for inclusion if only the authors responded to inquiry from ACM with requested primary data sets or unpublished results.

Selection of studies

Three authors (ACM, AMK, and AACB) reviewed the titles and abstracts to determine eligibility for inclusion based on relevance. Studies eligible for inclusion were prospective and randomized clinical trials enrolling patients with AAP treated in acute care environments (ED, ICU, and postoperative). The butyrophenone of interest must have been administered by either the IV or intramuscular route. Acceptable comparison groups included placebo, opiate only, corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or acetaminophen. The full articles of relevant abstracts were obtained and reviewed in their entirety.

Data extraction and management

Reference management and application of inclusion/exclusion criteria was performed with Rayyan (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Ar-Rayyan, Qatar; https://rayyan.qcri.org/). Three authors applied inclusion exclusion criteria (ACM, AMK, and YM). Four review authors (ACM, AMK, AACB, and YM) extracted data onto a pre-designed structured data extraction forms. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus. We arranged translation of any papers by experts where necessary.

Assessment of reporting biases and quality assessment

Three review authors (AMK, AACB, and YM) independently assessed the risk of bias using two validated tools: Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE),76 and RoB 2.0: “Revised tool for Risk of Bias in randomized trials”.77 ACM reviewed the Risk of Bias assessments. The review authors considered methods of randomization and allocation, blinding (of treatment administrator, participants, and outcome assessors), selective outcome reporting (eg, failure to report adverse events), and incomplete outcome data. Each trial was graded as high, low, or unclear risk of bias for each of these criteria.

Because of the clinical and statistical heterogeneity of the studies, the intended meta-analysis was omitted.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

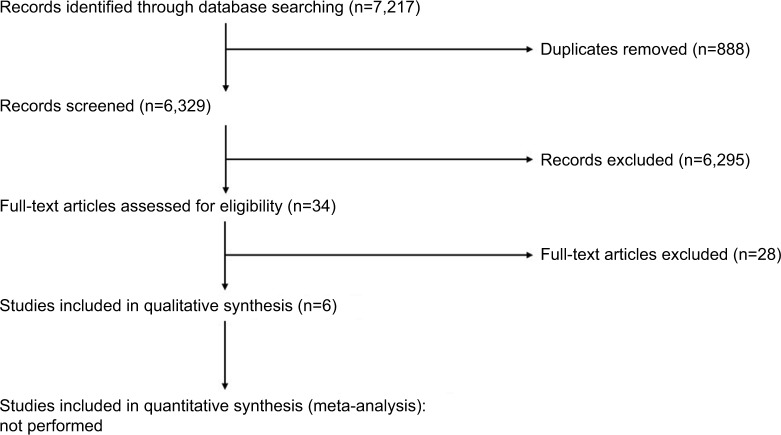

We identified 7,217 references from the following sources: Cochrane CENTRAL (n=108), CINAHL (n=129), DARE (n=5), DOAJ (n=25), Embase (n=4850), IEEE-Xplorer (n=149), LILACS (n=87), Magiran (n=10), PubMed (n=925), SID (n=22), Scopus (n=722), TÜBİTAK ULAKBİM (n=0), and Web of Science (n=185). We found no ongoing studies in the Clinicaltrials.gov, WHO ICTRP, or ANZCTR. No ongoing studies were identified in Clinicaltrials.gov, WHO ICTRP, or ANZCTR. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram, and the Supplementary material provides the search strategy.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Included studies

Six studies met the inclusion criteria and are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.78–83 One study assessed patients presenting to the ED with AAP associated with gastroparesis,83 whereas five studies assessed patients with abdominal pain following abdominal surgery: abdominal hysterectomy (n=4)79–82 and sleeve gastrectomy (n=1).78

Table 2.

Included studies of neuroleptanalgesia in patients with acute abdominal pain

| Author (year) | Design (N) | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Primary endpoints | Secondary endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency department | ||||||

| Roldan (2017)83 | Prospective Randomized Double-blind Controlled (33) | USA; 2 hospitals; emergency department; adult patients with acute exacerbation of previously diagnosed gastroparesis | Haloperidol 5 mg IM (single dose) | Placebo (single dose) + Conventional therapy | Pain intensity measured validated 10-point visual analog scale | 1. ED disposition 2. ED LOS 3. Nausea |

| Postoperative | ||||||

| Sharma (1993)82 | Prospective Randomized (42) | UK; hospital number not reported; post-op; adult women undergoing abdominal hysterectomy | PCA (no basal infusion) with bolus of Morphine 1 mg + droperidol 0.05 mg, and 5 minutes lockout (continued for 24 hours) | PCA (no basal infusion) with bolus of Morphine 1 mg, and 5 minutes lockout (continued for 24 hours) | Morphine consumption defined by mg of morphine received over 24 hours post-op | 1. Patient satisfaction with analgesia 2. Extrapyramidal side effects 3. Nausea |

| Laffey (2002)79 | Prospective Randomized Double-blind (30) | Ireland; 1 hospital; post-op; adult women undergoing abdominal hysterectomy | Post-op PCA of morphine (1.0 mg) plus cyclizine (2 mg). No basal infusion, 6-minute lock-out, 4 hours max morphine sulfate dose of 30 mg (continued for 48 hours) | Post-op PCA of morphine (1.0 mg) plus droperidol (0.05 mg). No basal infusion, 6-minute lock-out, 4 hours max morphine sulfate dose of 30 mg. (continued for 48 hours) | Pain intensity measured by 10 cm visual analog scale | 1. Nausea and vomiting 2. Sedation 3. Extra-pyramidal side effects |

| Liu (2003)80 | Prospective Randomized Double-blind (60) | China; 1 hospital; post-op; adult women undergoing abdominal hysterectomy | PCA (no basal infusion) with bolus of tramadol 20 mg + droperidol 0.1 mg; 10-minute lockout (continued for 36 hours) | PCA (no basal infusion) with bolus of tramadol 20 mg; 10-minute lockout. (continued for 36 hours) | 1. Pain intensity measured by 10 cm visual analog scale 2. Analgesia consumption defined by mg of morphine received over 36 hours post-op |

Side effects (sedation, nausea, vomiting, others) |

| Lo (2005)81 | Prospective Randomized Double-blind (179) | Taiwan; 1 hospital; post-op; adult women undergoing abdominal hysterectomy | PCA (no basal infusion) with bolus of morphine 1 mg + droperidol 0.05 mg. 5-minuite lockout. 4 hours morphine max of 30 mg (continued for 72 hours) | PCA (no basal infusion) with bolus of morphine 1 mg. 5-minuite lockout. 4 hours morphine max of 30 mg (continued for 72 hours) | 1. Pain intensity measured by a 10-point verbal rating scale 2. Morphine consumption defined by mg of morphine received over 72 hours post-op |

Side effects: extrapyramidal (restless, muscle spasms, involuntary/irregular movements) |

| Oliviera (2013)78 | Prospective Randomized Double-blind (90) | Brazil; 1 hospital; post-op; adult patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | Ondansetron 8 mg IV + dexamethasone 8 mg + haloperidol 2 mg (single dose) | Ondansetron 8 mg IV Ondansetron 8 mg IV + dexamethasone 8 mg IV (both single dose) | 1. Nausea defined by a 10-point verbal numerical scale 2. Pain intensity defined by a 10-point verbal rating scale |

Morphine consumption defined by mg of morphine received over 36 hours post-op |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; LOS, length-of-stay; IM, intramuscular; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; IV, intravenous; post-op, postoperative.

Table 3.

Summary of the clinical effects of neuroleptanalgesia in patients with acute abdominal pain

| Variable | Emergency department | Postoperative | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Roldan (2017)83 | Sharma (1993)82 | Laffey (2002)79 | Liu (2003)80 | Lo (2005)81 | Oliviera (2013)78 |

| Butyrophenone | Haloperidol | Droperidol | Droperidol | Droperidol | Droperidol | Haloperidol |

| Comparison | Standard care | Morphine | Morphine | Tramadol | Morphine | Dexamethasone Ondansetron |

| Pain intensity | ↓ | NC | ↓ | ↓a | ||

| Patient satisfaction | NC | ↑ | ||||

| Opiate consumption | NC | NC | NC | ↓ | ↓ | |

| ED admission | ↓ | |||||

| ED LOS | NC | |||||

| Extrapyramidal side effects | NC | NC | NC | |||

| Nausea | ↓ | ↓ | NC | Early – ↓ Late – NC |

Early – ↓ Late – NC |

↓ |

| Vomiting | ↓ | NC | Early – ↓ Late – NC |

Early – ↓ Late – NC |

NC | |

| Sedation | NC | NC | NC | |||

Notes: NC means no change.

The Haldol + dexamethasone + ondansetron group had improved pain scores compared to ondansetron alone (P=0.046), but no change compared to dexamethasone + ondansetron group (P=0.052).

Excluded studies

Excluded references assessing neuroleptanalgesia for abdominal pain included three case reports,48,49,61 three case series,54,59,84 and one non-randomized controlled trial.61 Ramirez et al34 was excluded as it had a retrospective cohort design. Three studies assessed pain in mixed populations, including abdominal, but data for abdominal pain patients was not listed independently.38,47,85 Bertrand et al55 was excluded as they did not clearly describe which urologic procedures were included or whether they were intra-abdominal. Lamond et al58 was excluded due to lack of a morphine only, placebo, or “no droperidol” control arm. Lastly, studies that assessed the effect of butyrophenones for abdominal pain administered neither intravenously or intramuscularly were excluded: epidural, extradural, or intrathecal;86–94 subcutaneous;95 or oral.96

Risk of bias in included studies

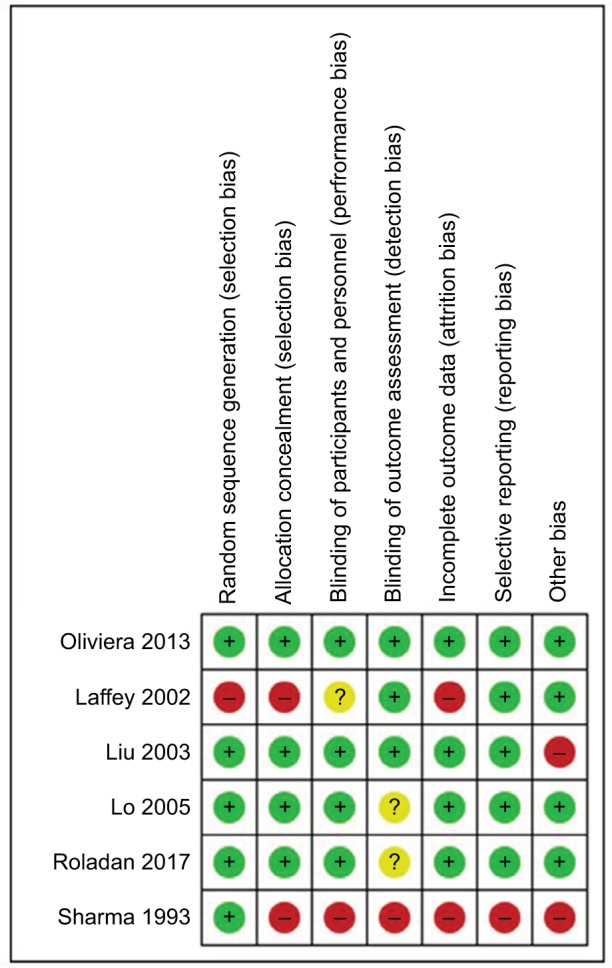

We have summarized our risk of bias and GRADE assessments in Figure 2 and Table 4.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment.

Notes: + signifies low risk; ? signifies uncertain risk; – signifies high risk.

Table 4.

GRADE quality of evidence ratings

| Certainty assessment | Certainty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Number of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |

| Opiate consumption | 5 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Very seriousa | Not serious | Not serious | Publication bias strongly suspectedb | ⨁○○○ Very low |

| Pain intensity | 4 | Randomized trials | Seriousc | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Publication bias strongly suspectedb | ⨁⨁○○ Low |

| ED admission | 1 | Randomized trials | Very seriousd | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Publication bias strongly suspectedb | ⨁○○○ Very low |

| ED length-of-stay | 1 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Publication bias strongly suspectedb | ⨁⨁⨁○ Moderate |

| Patient satisfaction | 2 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Publication bias strongly suspectedb | ⨁⨁⨁○ Moderate |

| Extrapyramidal side effects | 3 | Randomized trials | Very seriouse | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Publication bias strongly suspectedb | ⨁○○○ Very low |

Notes:

Two study drugs were assessed: haloperidol (two studies) and droperidol (three studies). Significant variability existed in control groups: conventional therapy (one study), morphine plus cyclizine (one study), tramadol (one study), morphine alone (one study), and dexamethasone and ondansetron (one study).

Small number of studies resulting in likely type II error. Absence of negative or neutral studies suggests evidence of publication bias.

Risk of bias high in one study, low in three studies.

The study was judged to have a high risk of bias.

One study at high risk, one study at moderate risk, and one study at low risk for bias.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations.

Allocation (selection bias)

Four studies were at low risk of selection bias, being adequately randomized with allocation concealment.78,80,81,83 Among the remaining studies, the risk of bias from the method of randomization was unclear,79 and the risk of bias for allocation concealment was unclear or high.79,82

Blinding (performance bias and detection bias)

Four studies were double-blinded.78,80,81,83 Although all six studies had a control arm, only one was a placebo controlled trial.83 One study reported “double-blind”, but the methods of concealment and blinding were not described in the manuscript, so it was marked as unclear.82 One article did not describe blinding or placebo use.82

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Two studies reported no patient attrition.78,79 One study reported <10% attrition,81 whereas one reported a rate of 16% for attrition.82 Two studies did not report patient attrition data.80,83

Selective reporting (reporting bias)

All included studies reported their intended primary outcomes. One study did not report adverse events.78

Other potential sources of bias

Diagnostic criteria

All included studies gave adequate information, namely that patients were diagnosed with AAP.78–83

Outcome criteria

Five studies assessed pain intensity. Three used a VAS (1–10),79,80,83 while two used a verbal rating scale (VRS; 1–10).78,81 Five studies assessed opiate consumption in terms of milligrams of morphine78,79,81,82 or tramadol80 consumed. Patient satisfaction with analgesia was reported in two studies using a 5-point scoring system.82,83

Statistical analysis

Five of the six included trials provided adequate details; they clearly stated the statistical tests used, which appeared appropriate.78–81,83 One trial was market “unclear” as it did not state the tests used.82

Baseline differences between groups

In five of the six trials, the provided information were adequate in this category.78–81,83 No significant differences were observed between treatment groups for these studies. One study scored “unclear” in this category as it did not clearly describe differences between groups.82

Pooling the data

We detected significant differences in clinical settings, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and quality of the trials. Due to high level of clinical heterogeneity, we determined that pooling the data and performing a meta-analysis would not be appropriate.

Effects of interventions

An overview of results is presented in Table 3. Three of four studies found improvements in pain intensity in the butyrophenone group. Three of five studies reporting postoperative opiate consumption reported no change,79,80,82 while two reported a decrease in opiate consumption.78,81 One ED study reported no change in patient satisfaction,83 while one postoperative study reported improvement in satisfaction scores.82 Extrapyramidal side effects79,81,82 and sedation79,80,82 were both reported as unchanged in three studies each.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Six RCTs (538 participants) that met the inclusion criteria were identified. Neuroleptanalgesia was associated with improved pain control (three of four studies); however, only two studies compared the strategy to an opiate-only group (morphine, n=1; tramadol, n=1).78,80,81,83 Opiate consumption was reported in five postoperative studies (no change [n=3],79,80,82 decreased [n=2]).78,81 One ED study reported no change in patient satisfaction,83 while one postoperative study reported improvement in satisfaction scores.82 Extrapyramidal side effects79,81,82 and sedation79,80,82 were both reported as unchanged in three studies each.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

There are some caveats that should be considered before drawing any conclusions from the findings of this systematic review. The small number of studies identified, of which all are positive, suggest both a high risk for publication bias and possibly type I error.

Heterogeneity may be due to clinical variation, for example, in study participation characteristics, baseline disease severity, delay in receiving treatment, different treatment used, and small numbers. For example, the mean age of included studies ranged from 32 to 58 years. It is unclear how this relatively young patient demographic influenced the findings. Conversely, included studies represent a mixture of resource-rich and -poor environments, with one study each from Brazil, China, England, Ireland, Taiwan, and the USA.

In addition, variation may be due to methodological considerations such as method of randomization, the use of blinding, the choice of outcome assessment measures, and trial duration. In particular, the trial by Sharma et al had methodological weaknesses in allocation concealment, blinding (participants and personnel), blinding of outcome assessment, and incomplete outcome data.82

Heterogeneity was less notable in the postoperative studies as the inclusion criteria were narrow. Only one ED study was included. Clinical heterogeneity (different pain assessment scales used) and methodological heterogeneity (different treatment regimens and follow-up plans) limit the interpretation of these data. We found variation in the clinical endpoints chosen as defining improved analgesia: three trials reported VAS,79,80,83 two reported VRS,78,81 and two reported patient satisfaction with analgesia scores.82,83 Whereas the differences in symptoms at recruitment are likely minimal for the postoperative trials, it is unclear whether a difference existed between the ED and postoperative trials.

Quality of evidence

We downgraded the quality of evidence for the trial by Sharma et al for concerns for potential selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and not describing a sample size calculation. The quality of evidence was also downgraded for the trial by Laffey et al because of concerns for potential selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment) and attrition bias.

Potential biases in the review process

We excluded several studies and a published abstract that provided insufficient information. One abstract50 seemed to duplicate information available in a subsequent published manuscript.83 One study was excluded because the published manuscript did not differentiate patients with abdominal pain from those with extremity pain.47 Attempts to contact the author for results on the abdominal pain patients did not receive response. As a result, there could be some risk of publication and selective reporting bias due to data from some studies being unavailable.

Lastly, we included studies conducted in Asia, North and South America, and Europe. It is possible that genetic differences in drug metabolism or response or even different etiological processes may account for some of the observed variation in response.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We identified no other systematic reviews or meta-analyses on this topic for comparison.

Conclusion

Implications for practice

Based on available evidence, we cannot draw any definitive conclusion on the efficacy or benefit of neuroleptanalgesia in the management of patients with AAP. However, the existing data suggest that these drugs may improve analgesia and decrease opiate consumption.

Implications for research

Additional clinical study is needed to assess the utility of neuroleptanalgesia for decreasing pain and opiate consumption of patients in acute care settings with abdominal pain from gastroparesis, cyclical vomiting syndrome, cannabinoid hyperemesis, and other forms of AAP.

Differences between protocol and review

The presence of significant methodological differences between studies precluded the performance of a meta-analysis. Therefore, only the systematic review portion of the project is presented in this manuscript.

Supplementary material

Literature search strategy

Combined search for butyrophenones

“Butyrophenones”[Mesh] OR “acetabutone” [Supplementary Concept] OR “Azaperone”[Mesh] OR “Benperidol”[Mesh] OR “bromperidol” [Supplementary Concept] OR “bromperidol decanoate” [Supplementary Concept] OR “4-bromospi-perone” [Supplementary Concept] OR “Droperidol”[Mesh] OR “fluanisone” [Supplementary Concept] OR “butofilolol” [Supplementary Concept] OR “carebastine” [Supplementary Concept] OR “centbutindole” [Supplementary Concept] OR “clofluperol” [Supplementary Concept] OR “Droperidol” [Mesh] OR “ebastine” [Supplementary Concept] OR “fluanisone” [Supplementary Concept] OR “Haloperidol”[Mesh] OR “ketocaine” [Supplementary Concept] OR “lenperone” [Supplementary Concept] OR “metylperon” [Supplementary Concept] OR “moperone” [Supplementary Concept] OR “pipamperone” [Supplementary Concept] OR “setoperone” [Supplementary Concept] OR “Spiperone”[Mesh] OR “spiramide” [Supplementary Concept]) OR “timiperone” [Supplementary Concept]) OR “Trifluperidol”[Mesh] OR Butyrophenone[tiab] OR Butyrophenones[tiab] OR Aceperone[tiab] OR Acetabutone[tiab] OR Acetobutone[tiab] OR Azaperone[tiab] OR Butanone[tiab] OR Sedaperone[tiab] OR Stresnil[tiab] OR Benperidol[tiab] OR Benperidone[tiab] OR Benzperidol[tiab] OR Frenactyl[tiab] OR Phenactil[tiab] OR Anquil[tiab] OR Frenactil[tiab] OR Glianimon[tiab] OR Bromperidol[tiab] OR Bromoperidol[tiab] OR Impromen[tiab] OR Tesoprel[tiab] OR Erodium[tiab] OR Bromospiperone[tiab] OR Bromospiroperidol[tiab] OR Butofilolol[tiab] OR cafide[tiab] OR Carebastine[tiab] OR Centbutindole[tiab] OR Indole[tiab] OR Cinuperone[tiab] OR Clofluperol[tiab] OR seperidol[tiab] OR Droperidol[tiab] OR Dridol[tiab] OR Droleptan[tiab] OR Droperol[tiab] OR Halkan[tiab] OR Inaprine[tiab] OR Inapsin[tiab] OR Inapsine[tiab] OR Oridol[tiab] OR Sintodian[tiab] OR Troperidol[tiab] OR Xomolix[tiab] OR Ebastine[tiab] OR Bactil[tiab] OR bastel[tiab] OR busidril[tiab] OR ebachoi[tiab] OR ebarren[tiab] OR ebastel[tiab] OR ebonde[tiab] OR ebontan[tiab] OR ebouda[tiab] OR evastel[tiab] OR kestin[tiab] OR kestine[tiab] OR “nosedat”[tiab] OR nosedat[tiab] OR oroba[tiab] OR Fluanisone[tiab] OR Hypnorm[tiab] OR “anti pica”[tiab] OR antipica[tiab] OR fluanison[tiab] OR fluanisone dihydrochloride[tiab] OR fluanizone[tiab] OR fluoanisone[tiab] OR haloanison[tiab] OR haloanisone[tiab] OR haloanizone[tiab] OR sedalande[tiab] OR sedalanide[tiab] OR solusediv[tiab] OR Fluspiperone[tiab] OR Haloperidol[tiab] OR alased[tiab] OR aloperidin[tiab] OR aloperidine[tiab] OR binison[tiab] OR brotopon[tiab] OR celenase[tiab] OR cereen[tiab] OR cerenace[tiab] OR cizoren[tiab] OR depidol[tiab] OR dores[tiab] OR dozic[tiab] OR duraperidol[tiab] OR fortunan[tiab] OR govotil[tiab] OR haldol[tiab] OR halidol[tiab] OR “halo-p”[tiab] OR halojust[tiab] OR halomed[tiab] OR haloneural[tiab] OR haloper[tiab] OR haloperil[tiab] OR haloperin[tiab] OR haloperitol[tiab] OR halopidol[tiab] OR halopol[tiab] OR halosten[tiab] OR haricon[tiab] OR haridol-d[tiab] OR keselan[tiab] OR linton[tiab] OR mixidol[tiab] OR novoperidol[tiab] OR peluces[tiab] OR perida[tiab] OR peridol[tiab] OR peridor[tiab] OR selezyme[tiab] OR seranace[tiab] OR serenace[tiab] OR serenase[tiab] OR serenelfi[tiab] OR siegoperidol[tiab] OR sigaperidol[tiab] OR Ketocaine[tiab] OR Lenperone[tiab] OR elanone[tiab] OR Lumateperone[tiab] OR Tosylate[tiab] OR Melperone[tiab] OR bunil[tiab] OR buronil[tiab] OR eunerpan[tiab] OR flubuperone[tiab] OR harmosin[tiab] OR melneurin[tiab] OR melperomerck[tiab] OR melperon[tiab] OR methylperon[tiab] OR methylperone[tiab] OR metylperone[tiab] OR metylperonum[tiab] OR Moperone[tiab] OR Libernil[tiab] OR luvatren[tiab] OR luvatrena[tiab] OR “methyl peridol”[tiab] OR methylperidol[tiab] OR methylperidole[tiab] OR moperon[tiab] OR Perfomedil[tiab] OR Pipamperone[tiab] OR car piperone[tiab] OR dipeperon[tiab] OR dipiperon[tiab] OR “dl piperonyl”[tiab] OR dipiperal[tiab] OR floropipamide[tiab] OR flouropipamide[tiab] OR piperonil[tiab] OR piperonyl[tiab] OR pripamperone[tiab] OR propitan[tiab] OR Setoperone[tiab] OR Spiperone[tiab] OR Spiroperidol[tiab] OR Spiropitan[tiab] OR Spiramide[tiab] OR “AMI-193”[tiab] OR Timiperone[tiab] OR tolopelon[tiab] OR Trifluperidol[tiab] OR triperidol[tiab] OR psicoperidol[tiab] OR trisedil[tiab] OR trisedyl[tiab].

Combined search for abdominal pain

Version 1: Combined MeSH terms for pain, postop pain, and acute pain with terms for abdomen and GI tract, without including all the MeSH terms nested under “pain”.

“Abdominal Pain” [ M e s h ] O R “A b d o m e n , Acute”[Mesh] OR “Irritable Bowel Syndrome”[Mesh] OR “Colonic Diseases”[Mesh] OR “Dyspepsia”[Mesh] OR “Gastroparesis”[Mesh] OR ((“Abdomen”[Mesh] OR “Digestive System”[Mesh]) AND (“Acute Pain”[Mesh] OR “Pain”[Mesh:NoExp] OR “Pain, Postoperative”[Mesh])) OR ((Abdomen[tiab] OR Abdomens[tiab] OR Abdominal[tiab] OR Intestine[tiab] OR Intestines[tiab] OR Intestinal[tiab] OR Viscera[tiab] OR Visceral[tiab] OR Tummy[tiab] OR Bowel[tiab] OR Bowels[tiab] OR Belly[tiab] OR Gastrointestinal[tiab] OR Gastric[tiab] OR “gi tract”[tiab] OR “gi tracts”[tiab] OR epigastric[tiab] OR Stomach[tiab] OR Stomachs[tiab]) AND (Pain[tiab] OR Pains[tiab] OR Painful[tiab] OR Ache[tiab] OR Aches[tiab] OR Achy[tiab] OR Aching[tiab] OR Cramp[tiab] OR Cramps[tiab] OR Discomfort[tiab] OR discomforting[tiab] OR Suffering[tiab] OR Sufferings[tiab] OR Agony[tiab] OR agonizing[tiab] OR Distress[tiab] OR Distressful[tiab] OR Spasm[tiab] OR Spasms[tiab] OR Paroxysm[tiab] OR paroxysms[tiab])) OR Gastroparesis[tiab] OR “gastric stasis”[tiab] OR Dyspepsia[tiab] OR Dyspeptic[tiab] OR Dyspepsias[tiab] OR “Irritable bowel syndrome”[tiab].

Version 2: Took off the ‘Mesh:NoExp’ from term “Pain”[Mesh]: yielded 553 articles when combined with butyrophenones terms.

“Abdominal Pain” [ M e s h ] O R “A b d o m e n , Acute”[Mesh] OR “Irritable Bowel Syndrome”[Mesh] OR “Colonic Diseases”[Mesh] OR “Dyspepsia”[Mesh] OR “Gastroparesis”[Mesh] OR ((“Abdomen”[Mesh] OR “Digestive System”[Mesh]) AND (“Acute Pain”[Mesh] OR “Pain”[Mesh] OR “Pain, Postoperative”[Mesh])) OR ((Abdomen[tiab] OR Abdomens[tiab] OR Abdominal[tiab] OR Intestine[tiab] OR Intestines[tiab] OR Intestinal[tiab] OR Viscera[tiab] OR Visceral[tiab] OR Tummy[tiab] OR Bowel[tiab] OR Bowels[tiab] OR Belly[tiab] OR Gastrointestinal[tiab] OR Gastric[tiab] OR “gi tract”[tiab] OR “gi tracts”[tiab] OR epigastric[tiab] OR Stomach[tiab] OR Stomachs[tiab]) AND (Pain[tiab] OR Pains[tiab] OR Painful[tiab] OR Ache[tiab] OR Aches[tiab] OR Achy[tiab] OR Aching[tiab] OR Cramp[tiab] OR Cramps[tiab] OR Discomfort[tiab] OR discomforting[tiab] OR Suffering[tiab] OR Sufferings[tiab] OR Agony[tiab] OR agonizing[tiab] OR Distress[tiab] OR Distressful[tiab] OR Spasm[tiab] OR Spasms[tiab] OR Paroxysm[tiab] OR paroxysms[tiab])) OR Gastroparesis[tiab] OR “gastric stasis”[tiab] OR Dyspepsia[tiab] OR Dyspeptic[tiab] OR Dyspepsias[tiab] OR “Irritable bowel syndrome”[tiab].

Took off the “no explosion” from Mesh term for pain: yielded 772 results when combined with butyrophenones terms; 560 articles when animal studies removed.

“Acute Pain”[Mesh] OR “Pain”[Mesh] OR “Abdominal Pain”[Mesh] OR “Abdomen, Acute”[Mesh] OR “Irritable Bowel Syndrome”[Mesh] OR “Colonic Diseases”[Mesh] OR “Dyspepsia”[Mesh] OR “Gastroparesis”[Mesh] OR ((Abdomen[tiab] OR Abdomens[tiab] OR Abdominal[tiab] OR Intestine[tiab] OR Intestines[tiab] OR Intestinal[tiab] OR Viscera[tiab] OR Visceral[tiab] OR Tummy[tiab] OR Bowel[tiab] OR Bowels[tiab] OR Belly[tiab] OR Gastrointestinal[tiab] OR Gastric[tiab] OR “gi tract”[tiab] OR “gi tracts”[tiab] OR epigastric[tiab] OR Stomach[tiab] OR Stomachs[tiab]) AND (Pain[tiab] OR Pains[tiab] OR Painful[tiab] OR Ache[tiab] OR Aches[tiab] OR Achy[tiab] OR Aching[tiab] OR Cramp[tiab] OR Cramps[tiab] OR Discomfort[tiab] OR discomforting[tiab] OR Suffering[tiab] OR Sufferings[tiab] OR Agony[tiab] OR agonizing[tiab] OR Distress[tiab] OR Distressful[tiab] OR Spasm[tiab] OR Spasms[tiab] OR Paroxysm[tiab] OR paroxysms[tiab] OR paroxysmal[tiab])) OR Gastroparesis[tiab] OR “gastric stasis”[tiab] OR Dyspepsia[tiab] OR Dyspeptic[tiab] OR Dyspepsias[tiab] OR “Irritable bowel syndrome”[tiab].

Added in terms for abdomen and GI tract: yielded 2,489 articles when combined with butyrophenones terms; 772 when animal studies removed.

“Abdominal Pain” [ M e s h ] O R “A b d o m e n , Acute”[Mesh] OR “Irritable Bowel Syndrome”[Mesh] OR “Colonic Diseases”[Mesh] OR “Dyspepsia”[Mesh] OR “Gastroparesis”[Mesh] OR “Abdomen”[Mesh] OR “Digestive System”[Mesh] OR “Acute Pain”[Mesh] OR “Pain”[Mesh:NoExp] OR “Pain, Postoperative”[Mesh] OR ((Abdomen[tiab] OR Abdomens[tiab] OR Abdominal[tiab] OR Intestine[tiab] OR Intestines[tiab] OR Intestinal[tiab] OR Viscera[tiab] OR Visceral[tiab] OR Tummy[tiab] OR Bowel[tiab] OR Bowels[tiab] OR Belly[tiab] OR Gastrointestinal[tiab] OR Gastric[tiab] OR “gi tract”[tiab] OR “gi tracts”[tiab] OR epigastric[tiab] OR Stomach[tiab] OR Stomachs[tiab]) AND (Pain[tiab] OR Pains[tiab] OR Painful[tiab] OR Ache[tiab] OR Aches[tiab] OR Achy[tiab] OR Aching[tiab] OR Cramp[tiab] OR Cramps[tiab] OR Discomfort[tiab] OR discomforting[tiab] OR Suffering[tiab] OR Sufferings[tiab] OR Agony[tiab] OR agonizing[tiab] OR Distress[tiab] OR Distressful[tiab] OR Spasm[tiab] OR Spasms[tiab] OR Paroxysm[tiab] OR paroxysms[tiab] OR paroxysmal[tiab])) OR Gastroparesis[tiab] OR “gastric stasis”[tiab] OR Dyspepsia[tiab] OR Dyspeptic[tiab] OR Dyspepsias[tiab] OR “Irritable bowel syndrome”[tiab].

Acknowledgments

No funding was received for this work. An abstract of this paper was presented at the East Carolina University 21st Annual Medical Student Research Forum with interim findings. The poster is available online at https://doi.org.10.13140/RG.2.2.12582.01601.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The contributions of AACB in this study were funded by the East Carolina University Brody School of Medicine Summer Scholar Research Program. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Cervellin G, Mora R, Ticinesi A, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute abdominal pain in a large urban emergency department: retrospective analysis of 5,340 cases. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(19):362. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.09.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hastings RS, Powers RD. Abdominal pain in the ED: a 35 year retrospective. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(7):711–716. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cinar O, Jay L, Fosnocht D, et al. Longitudinal trends in the treatment of abdominal pain in an academic emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(3):324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singhal A, Tien YY, Hsia RY. Racial-ethnic disparities in opioid prescriptions at emergency department visits for conditions commonly associated with prescription drug abuse. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0159224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Todd KH. A review of current and emerging approaches to pain management in the emergency department. Pain Ther. 2017;6(2):193–202. doi: 10.1007/s40122-017-0090-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mura P, Serra E, Marinangeli F, et al. Prospective study on prevalence, intensity, type, and therapy of acute pain in a second-level urban emergency department. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2781–2788. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S137992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allione A, Melchio R, Martini G, et al. Factors influencing desired and received analgesia in emergency department. Intern Emerg Med. 2011;6(1):69–78. doi: 10.1007/s11739-010-0463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen EH, Shofer FS, Dean AJ, et al. Gender disparity in analgesic treatment of emergency department patients with acute abdominal pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(5):414–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banz VM, Christen B, Paul K, et al. Gender, age and ethnic aspects of analgesia in acute abdominal pain: is analgesia even across the groups? Intern Med J. 2012;42(3):281–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2010.02255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shabbir J, Ridgway PF, Lynch K, et al. Administration of analgesia for acute abdominal pain sufferers in the accident and emergency setting. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11(6):309–312. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200412000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang DC, Parry CR, Feldman M, Tomlinson G, Sarrazin J, Glanc P. Acute abdomen in the emergency department: Is CT a time-limiting factor? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(6):1222–1229. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.14057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sokoloff C, Daoust R, Paquet J, Chauny JM. Is adequate pain relief and time to analgesia associated with emergency department length of stay? A retrospective study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e004288. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manterola C, Vial M, Moraga J, Astudillo P. Analgesia in patients with acute abdominal pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;1:CD005660. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005660.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolfe JM, Lein DY, Lenkoski K, Smithline HA. Analgesic administration to patients with an acute abdomen: a survey of emergency medicine physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18(3):250–253. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(00)90114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Todd KH, Ducharme J, Choiniere M, et al. Pain in the emergency department: results of the pain and emergency medicine Initiative (PEMI) multicenter study. J Pain. 2007;8(6):460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinatra R. Causes and consequences of inadequate management of acute pain. Pain Med. 2010;11(12):1859–1871. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones MR, Viswanath O, Peck J, Kaye AD, Gill JS, Simopoulos TT. A brief history of the opioid epidemic and strategies for pain medicine. Pain Ther. 2018;7(1):13–21. doi: 10.1007/s40122-018-0097-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falch C, Vicente D, Häberle H, et al. Treatment of acute abdominal pain in the emergency room: a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(7):902–913. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2014.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollack CV, Diercks DB, Thomas SH, et al. Patient-reported Outcomes from a national, prospective, observational study of emergency department acute pain management with an intranasal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, opioids, or both. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(3):331–341. doi: 10.1111/acem.12902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fingar KR, Stocks C, Weiss AJ, Ca S, Fingar KR, Steiner CA. Most frequent operating room procedures performed in U.S. hospitals, 2003–2012. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Statistical Brief #186. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2014:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chesney TR, Chesney TR, Acuna SA, McLeod RS, McLeod RS, Best Practice in Surgery Group Opioid use after discharge in postoperative patients: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2018;267(6):1056–1062. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan WH, Yu J, Feaman S, et al. Opioid medication use in the surgical patient: an assessment of prescribing patterns and use. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227(2):203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.As-Sanie S, Till SR, Mowers EL, et al. Opioid prescribing patterns, patient use, and postoperative pain after hysterectomy for benign indications. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(6):1261–1268. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harbaugh CM, Lee JS, Hu HM, et al. Persistent opioid use among pediatric patients after surgery. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1):e20172439. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macario A, Royal MA. A literature review of randomized clinical trials of intravenous acetaminophen (paracetamol) for acute postoperative pain. Pain Pract. 2011;11(3):290–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ong CK, Seymour RA, Lirk P, Merry AF. Combining paracetamol (acetaminophen) with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: a qualitative systematic review of analgesic efficacy for acute postoperative pain. Anesthes Analges. 2010;110:1170–1179. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181cf9281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wininger SJ, Miller H, Minkowitz HS, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, repeat-dose study of two intravenous acetaminophen dosing regimens for the treatment of pain after abdominal laparoscopic surgery. Clin Ther. 2010;32(14):2348–2369. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marret E, Rolin M, Beaussier M, Bonnet F. Meta-analysis of intravenous lidocaine and postoperative recovery after abdominal surgery. Br J Surg. 2008;95(11):1331–1338. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tempel G, von Hundelshausen B, Reeker W. The opiate-sparing effect of dipyrone in post-operative pain therapy with morphine using a patient-controlled analgesic system. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(10):1043–1047. doi: 10.1007/BF01699225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honkaniemi J, Liimatainen S, Rainesalo S, Sulavuori S. Haloperidol in the acute treatment of migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache. 2006;46(5):781–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haloperidol® (haloperidol lactate) injection [prescribing information] Hudson, OH: Lexi-drugs; [Accessed June 2018]. online: 2016. Available from: http://online.lexi.com. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maltbie AA, Cavenar JO. Haloperidol and analgesia: case reports. Mil Med. 1977;142(12):946–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maltbie AA, Cavenar JO, Sullivan JL, Hammett EB, Zung WW. Analgesia and haloperidol: a hypothesis. J Clin Psych. 1979;40:323–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramirez R, Stalcup P, Croft B, Darracq MA. Haloperidol undermining gastroparesis symptoms (HUGS) in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(8):1118–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merlos M, Romero L, Zamanillo D, Plata-Salamán C, Vela JM. Sigma-1 receptor and pain. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;244:131–161. doi: 10.1007/164_2017_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castany S, Gris G, Vela JM, Verdú E, Boadas-Vaello P. Critical role of sigma-1 receptors in central neuropathic pain-related behaviours after mild spinal cord injury in mice. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22217-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cobos EJ, Baeyens JM. Use of very-low-dose methadone and haloperidol for pain control in palliative care patients: are the sigma-1 receptors involved? J Palliat Med. 2015;18(8):660. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salpeter SR, Buckley JS, Buckley NS, Bruera E. The use of very-low-dose methadone and haloperidol for pain control in the hospital setting: a preliminary report. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(2):114–119. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salpeter SR, Buckley JS, Bruera E. The use of very-low-dose methadone for palliative pain control and the prevention of opioid hyperalgesia. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(6):616–622. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mula M, Monaco F. Antiepileptic-antipsychotic drug interactions: a critical review of the evidence. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2002;25(5):280–289. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haldol ® (haloperidol lactate) [package insert] Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2017. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith JC, Wright EL. Haloperidol: an alternative butyrophenone for nausea and vomiting prophylaxis in anesthesia. Aana J. 2005;73(4):273–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seidel S, Aigner M, Ossege M, Pernicka E, Wildner B, Sycha T. Antipsychotics for acute and chronic pain in adults. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(4):768–778. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaffigan ME, Bruner DI, Wason C, Pritchard A, Frumkin K. A randomized controlled trial of intravenous haloperidol vs. intravenous metoclopramide for acute migraine therapy in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(3):326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fisher H. A new approach to emergency department therapy of migraine headache with intravenous haloperidol: a case series. J Emerg Med. 1995;13(1):119–122. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(94)00121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siker ES, Wolfson B, Stewart WD, Ciccarelli HE. The effects of fentanyl and droperidol, alone and in combination, on pain thresholds in human volunteers. Anesthesiology. 1968;29(4):834–838. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196807000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Afzalimoghaddam M, Edalatifard M, Nejati A, Momeni M, Isavi N, Karimialavijeh E. Midazolam plus haloperidol as adjuvant analgesics to morphine in opium dependent patients: a randomized clinical trial. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2017;9(2):142–147. doi: 10.2174/1874473710666170106122455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hickey JL, Witsil JC, Mycyk MB. Haloperidol for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(6):1003.e5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Inayat F, Virk HU, Ullah W, Hussain Q. Is haloperidol the wonder drug for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome? BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2016218239. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-218239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roldan C, Chathampally Y. (232) Haloperidol vs. placebo in addition to conventional therapy to treat pain secondary to gastroparesis in the emergency department. J Pain. 2015;16(4):S34. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carlos RJ, Paniagua L, Chathampally Y, Banuelos R. Trial of haloperidol vs. placebo in addition to conventional therapy in ED patients with gastroparesis. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:S266. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stalcup P, Croft B, Ramirez R, Darracq M. 204 Haloperidol undermining gastroparesis symptoms in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;68(4):S80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lods JC, Vallin J, Dupuy R. Treatment of hemorrhagic rectocolitis with certain butyrophenones, haloperidol and triperidol. Arch Mal Appar Dig Mal Nutr. 1964;53:93–100. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chojnacki J, Tkaczewski W, Klupińska G, Zabielski G. Droperidol in an attack of hepatic colic. Wiad Lek. 1982;35(3-4):187–189. Polish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bertrand JC, Bertrand AM, Conil JM, Guerot A. Double-blind randomized clinical study of a droperidol-fentanyl combination. Cah Anesthesiol. 1984;32(3):225. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rozen P, Ratan J, Gilat T. Fentanyl-droperidol neuroleptanalgesia in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1977;23(3):142–144. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(77)73619-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rubin J, Bryer JV, Brock-Utne JG, Moshal MG. The use of neurolept analgesia for gastro-intestinal endoscopy. S Afr Med J. 1977;52(21):835–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lamond CT, Robinson DL, Boyd JD, Cashman JN. Addition of droperidol to morphine administered by the patient-controlled analgesia method: what is the optimal dose? Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1998;15(3):304–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.1998.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krimmer H, Pfeiffer H, Arbogast R, Sprotte G. Combined infusion analgesia–an alternative concept for postoperative pain treatment. Chirug. 1986;57:327–329. German. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koetsawang S, Srisupandit S, Kiriwat O, Apimas SJ, Feldblum P. Three neuroleptanalgesia schedules for laparoscopic sterilization by electro-coagulation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1983;21(2):133–137. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(83)90050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Daw JL, Cohen-Cole SA. Haloperidol analgesia. South Med J. 1981;74(3):364–365. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198103000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barbier JP, Dorf G, Gordin J, et al. Effect of a buzepide metiodide-haloperidol combination in treating functional intestinal disorders. randomized double-blind controlled versus placebo study. Ann Gastroenterol Hepatol (Paris) 1989;25(3):123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Judkins KC, Harmer M. Haloperidol as an adjunct analgesic in the management of postoperative pain. Anaesthesia. 1982;37(11):1118–1120. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1982.tb01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2018. [Accessed August 3, 2018]. Opioid Overdose Crisis 2018. Available from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rolheiser LA, Cordes J, Subramanian SV. Opioid prescribing rates by congressional districts, United States, 2016. Am J Pub Health. 2018;108(9):1214–1219. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morris B, Mir H. The opioid epidemic: impact on orthopaedic surgery. J Am Acad Ortho Surg. 2015;23:267–271. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Multiple cause of death 1999–2016. National Center for Health Statistics; [Accessed February 2018]. Available from: http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, Frohe T, Ney JP, van der Goes DN. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156(4):569–576. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460357.01998.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.U.S. Drug overdose deaths continue to rise: increase fueled by synthetic opioids 2018. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. [Accessed August 3, 2018]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0329-drug-overdose-deaths.html. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Understanding the epidemic 2017. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Accessed August 3, 2018]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anonymous report of the International narcotics control board for 2017. Vienna, Austria: United Nations; 2018. [Accessed August 3, 2018]. pp. 1–135. Available from: https://www.incb.org/documents/Publications/AnnualReports/AR2017/Annual_Report/E_2017_AR_ebook.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hoppe JA, Nelson LS, Perrone J, Weiner SG, Prescribing Opioids Safely in the Emergency Department (POSED) Study Investigators; Prescribing Opioids Safely in the Emergency Department POSED Study Investigators Opioid prescribing in a cross section of US emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66(3):253–259.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-prescribing patterns of Emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):663–673. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1610524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Johnson K, Jones C, Compton W, et al. Federal response to the opioid crisis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15(4):293–301. doi: 10.1007/s11904-018-0398-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chang SC, Ma CC, Lee CT, Hsieh SW. Pharmacoepidemiology of chronic noncancer pain patients requiring chronic opioid therapy: a nationwide population-based study. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2015;53(3):89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.aat.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. Grade guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Higgins JPT, Sterne JAC, Savović J, et al. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. In: Chandler J, McKenzie J, Boutron I, Welch V, editors. Cochrane Methods Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10 Suppl 1 Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oliveira SDS, Aguilar-Nascimento JE, Benevides ML. Combination of haloperidol, dexamethasone, and ondansetron reduces nausea and pain intensity and Morphine consumption after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Braz J Anesthes. 2013;63:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.bjan.2012.07.011. Portugese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Laffey JG, Boylan JF. Cyclizine and droperidol have comparable efficacy and side effects during patient-controlled analgesia. Ir J Med Sci. 2002;171(3):141–144. doi: 10.1007/BF03170501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu GK, Huang YG, Zhang YF, Ren HZ, Ren HZ. Patient-controlled analgesia with tramadol and tramadol/droperidol mixture after abdominal hysterectomy: a double-blinded, randomized controlled trial. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2003;83(22):1936–1938. Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lo Y, Chia YY, Liu K, Ko NH. Morphine sparing with droperidol in patient-controlled analgesia. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17(4):271–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sharma SK, Davies MW. Patient-controlled analgesia with a mixture of morphine and droperidol. Br J Anaesth. 1993;71(3):435–436. doi: 10.1093/bja/71.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roldan CJ, Chambers KA, Paniagua L, et al. Randomized controlled double-blind trial comparing haloperidol combined with conventional therapy to conventional therapy alone in patients with symptomatic gastroparesis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(11):1307–1314. doi: 10.1111/acem.13245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Colclough, Md G, McLarney, et al. Epidural haloperidol enhances epidural morphine analgesia: three case reports. J Opioid Manag. 2018;4(3):163–166. doi: 10.5055/jom.2008.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Admiraal PV, Knape H, Zegveld C. Experience with bezitramide and droperidol in the treatment of severe chronic pain. Sur Anesthesiol. 1973;17(6):529–530. doi: 10.1093/bja/44.11.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nishimura N, Metori S. Combined use of neuroleptanalgesia and epidural anesthesia for upper abdominal surgery. Masui. 1971;20(5):403–406. Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nora LRF, Vieira AM, Marchesini CS, Schnaider TB. Droperidol and morphine epidural. Assessment of analgesia and side effects prophylaxis morphine. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 1998;48:93–98. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ochi G, Mastutani M, Ishiguro A, Hori S, Fujii A, Sato T. Epidural administration of morphine-droperidol mixture for postoperative analgesia. Masui. 1985;34(3):330–334. Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ozcengiz D, Isik G, Aribogana, Erkan O. Postoperative analgesic pain relief by epidural droperidol-fentanyl combination. Agri Dergisi. 1993;5:18–22. Turkish. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shimohata K, Shimohata T, Ikeda N, et al. Effectiveness of low dose PCEA for postoperative pain after laparoscopic gynecological surgeries–a comparison of laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy and myomectomy. Masui. 2011;60(6):666–670. Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang M, Cl C, Xq X. Application study of patient-controlled epidural analgesia in peri-interventional uterine arterial embolization for uterine myomata. J Intervent Radiol. 2006;15:483–486. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Isosu T, Katoh M, Okuaki A. Continuous epidural droperidol for postoperative pain. Masui. 1995;44(7):1014–1017. Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kobayashi M, Ando N, Mochidome M, Yoshiyama Y, Kawamata M. Extradural morphine, ketamine and droperidol for postoperative pain and nausea relieves following laparoscopic gynaecological surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28:110. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Torres Huerta JC, Hernandez Santos JR, Tenopala Villegas S, Ocampo Abundes L, Nunez Quezada G. Use of epidural droperidol as antiemetic agent combined with morphine for postoperative pain control. Rev Mex Anestesiol. 2001;24:201–207. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lopuh M. Use of Lidocaine, Ketamine and haloperidol in a subcutaneous infusion for treatment of neuropathic pain. Zdravniski Vestnik. 2008;77 Slovenian. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Amery WK, Admiral PV, Beck PH, et al. Peroral management of chronic pain by means of bezitramide (R 4845), a long-acting analgesic, and droperidol (R 4749), a neuroleptic. a multicentric pilot-study. Arzneimittelforschung. 1971;21:868–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]