Abstract

Background

General anaesthesia combined with epidural analgesia may have a beneficial effect on clinical outcomes. However, use of epidural analgesia for cardiac surgery is controversial due to a theoretical increased risk of epidural haematoma associated with systemic heparinization. This review was published in 2013, and it was updated in 2019.

Objectives

To determine the impact of perioperative epidural analgesia in adults undergoing cardiac surgery, with or without cardiopulmonary bypass, on perioperative mortality and cardiac, pulmonary, or neurological morbidity.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and Embase in November 2018, and two trial registers up to February 2019, together with references and relevant conference abstracts.

Selection criteria

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including adults undergoing any type of cardiac surgery under general anaesthesia and comparing epidural analgesia versus another modality of postoperative pain treatment. The primary outcome was mortality.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures as expected by Cochrane.

Main results

We included 69 trials with 4860 participants: 2404 given epidural analgesia and 2456 receiving comparators (systemic analgesia, peripheral nerve block, intrapleural analgesia, or wound infiltration). The mean (or median) age of participants varied between 43.5 years and 74.6 years. Surgeries performed were coronary artery bypass grafting or valvular procedures and surgeries for congenital heart disease. We judged that no trials were at low risk of bias for all domains, and that all trials were at unclear/high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel taking care of study participants.

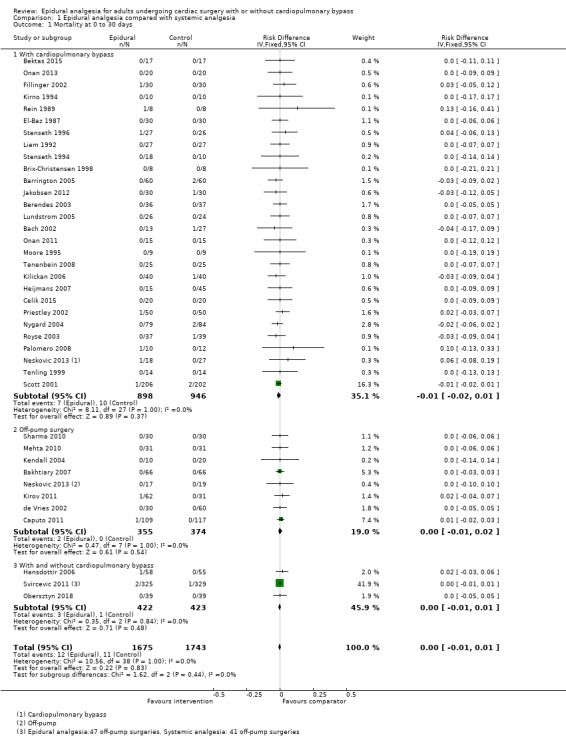

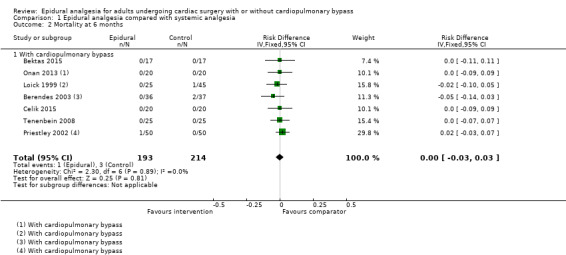

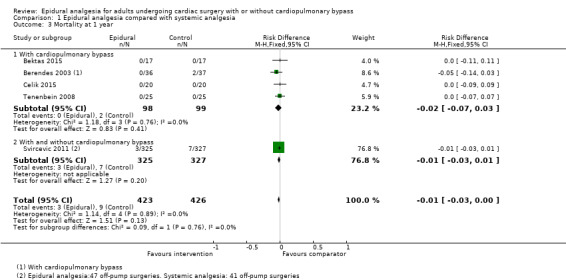

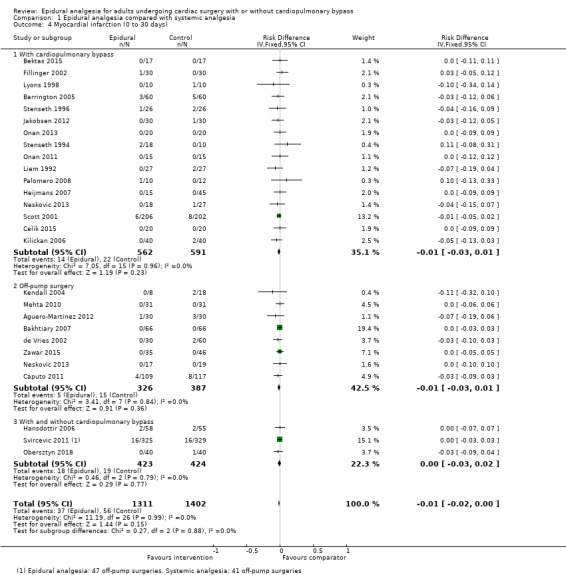

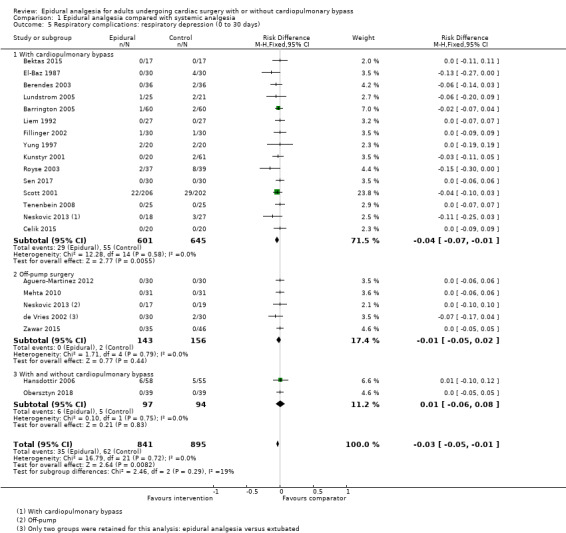

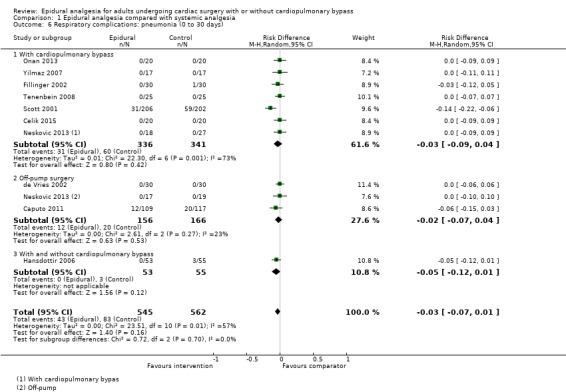

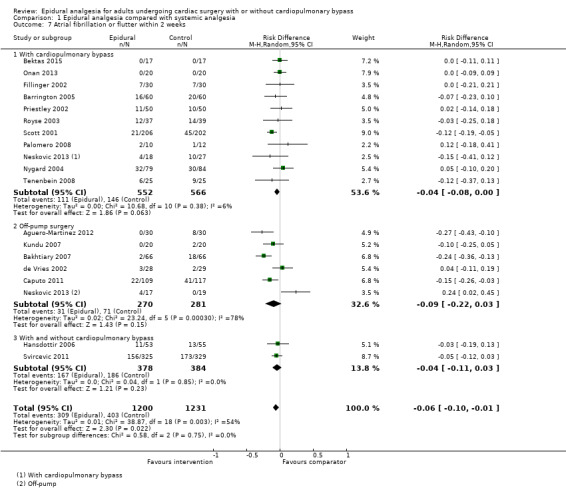

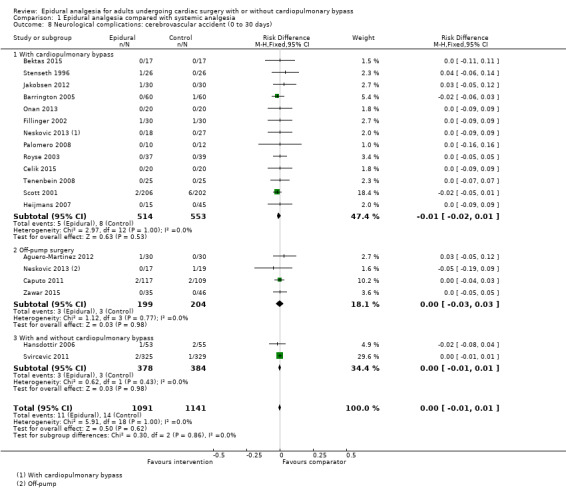

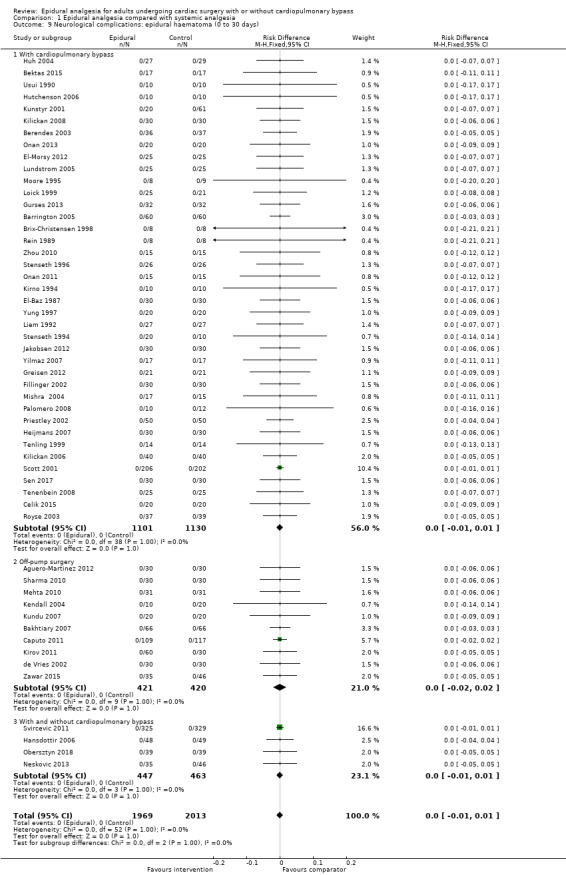

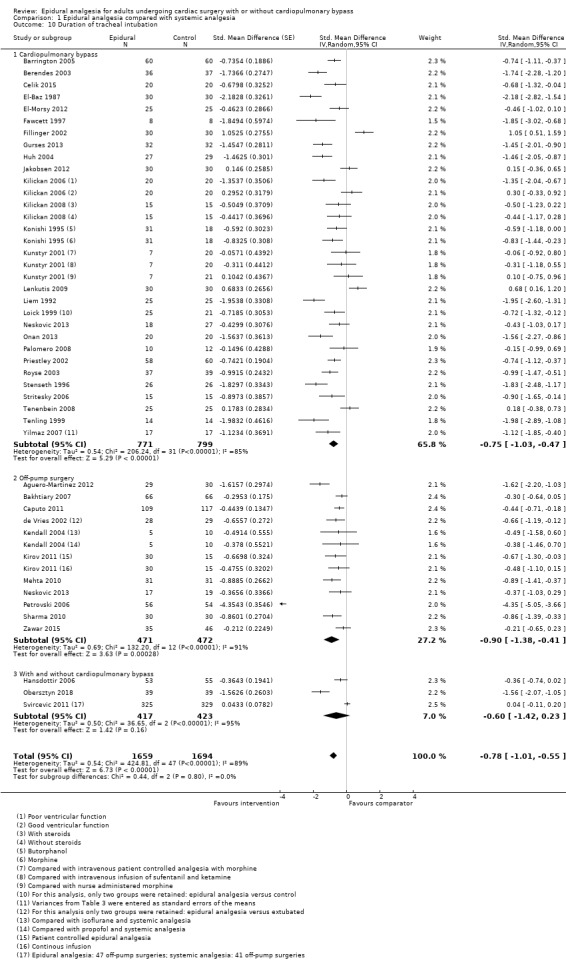

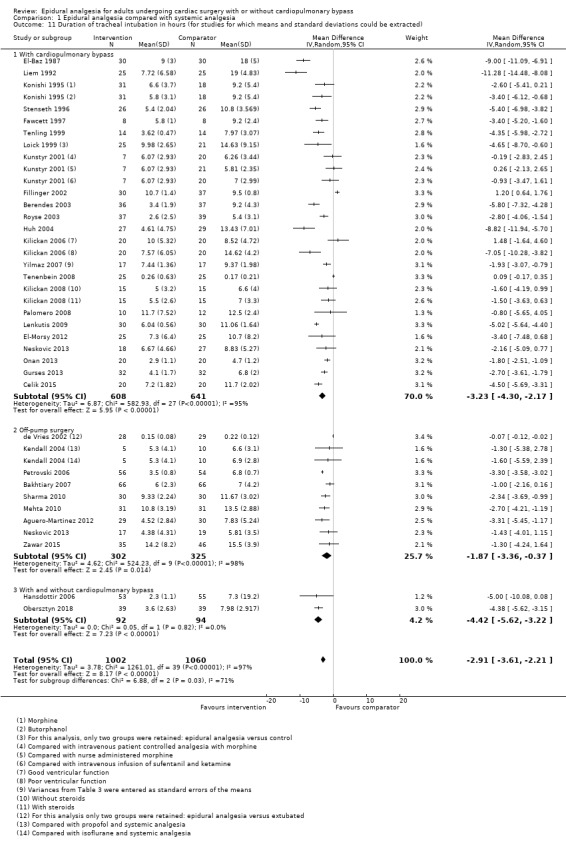

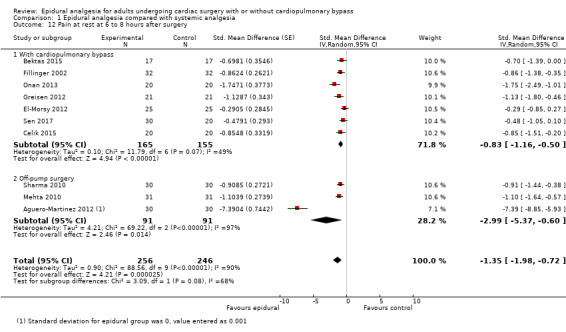

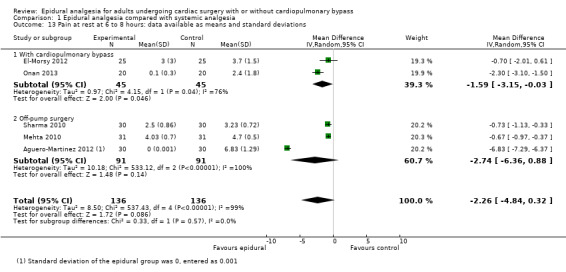

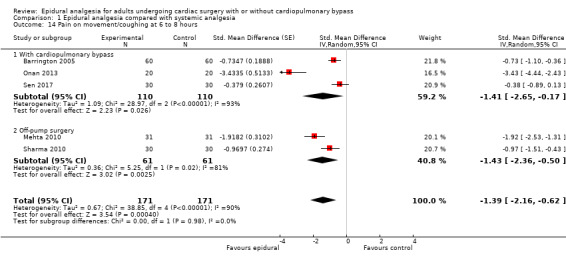

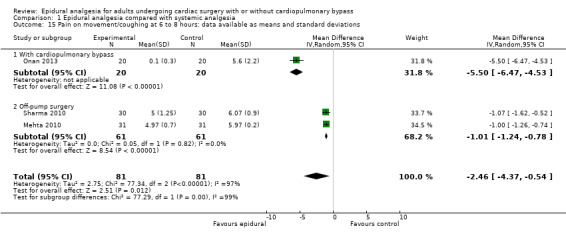

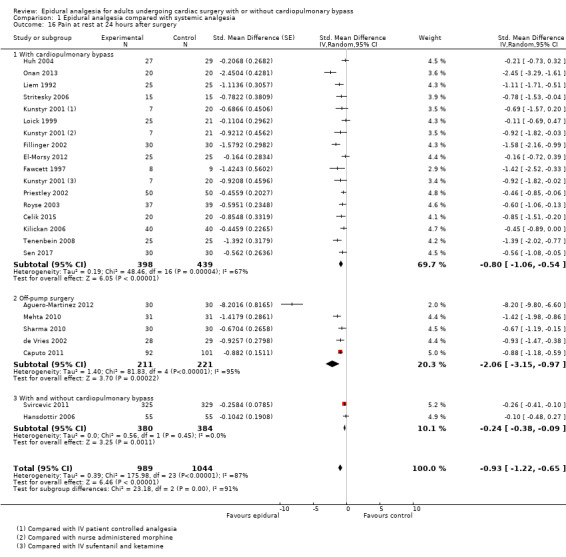

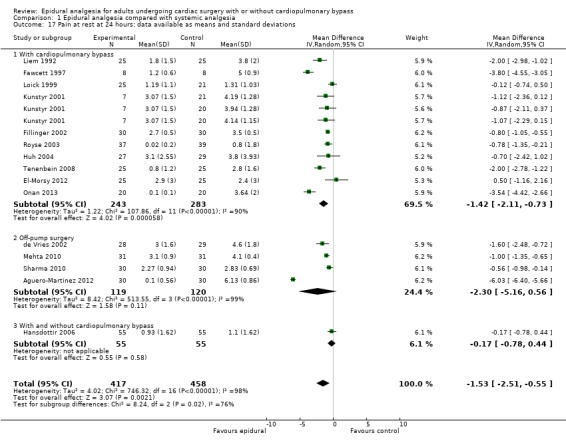

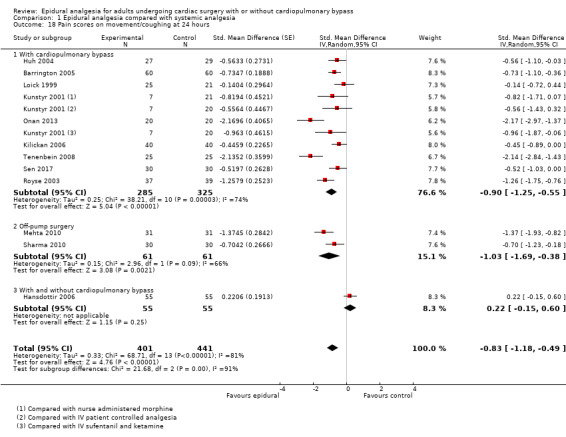

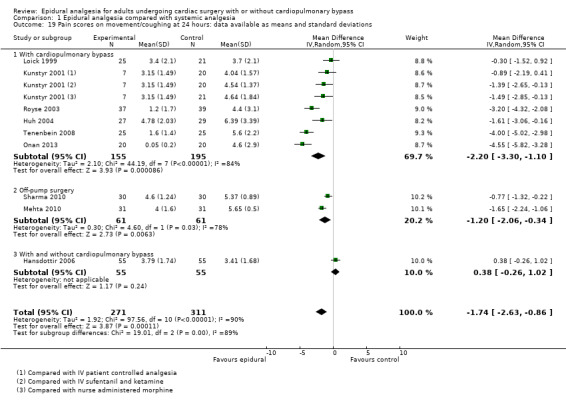

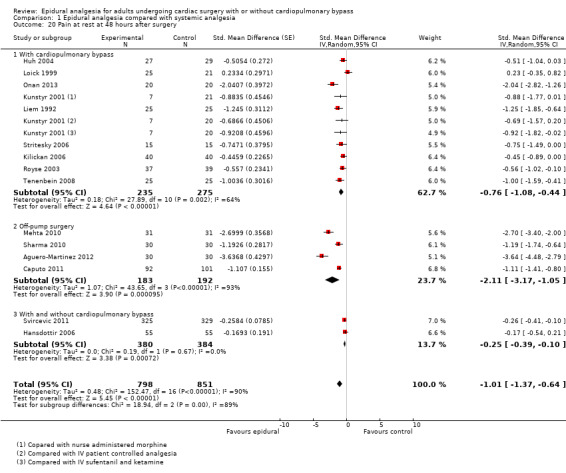

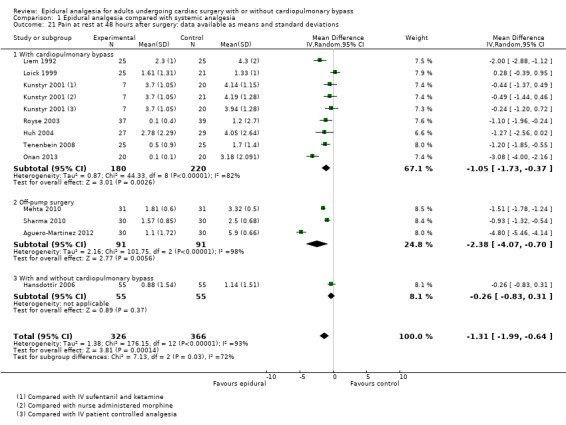

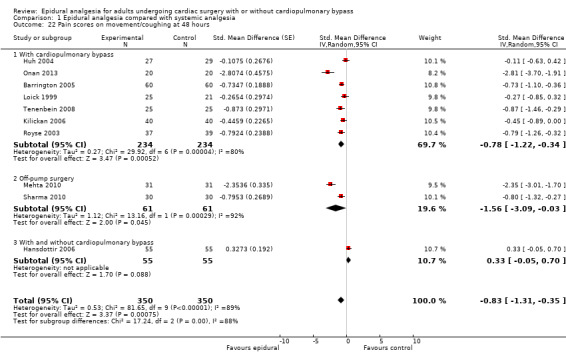

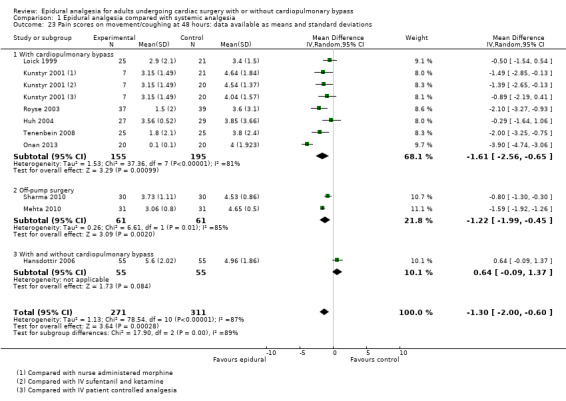

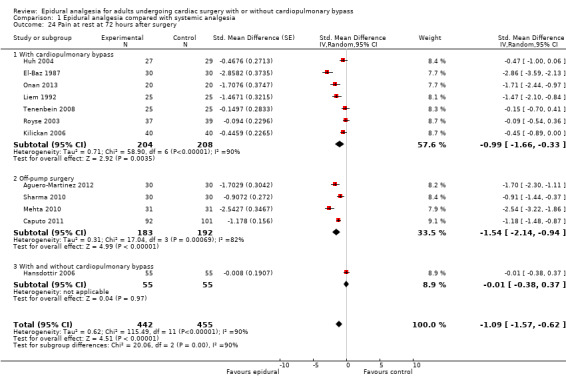

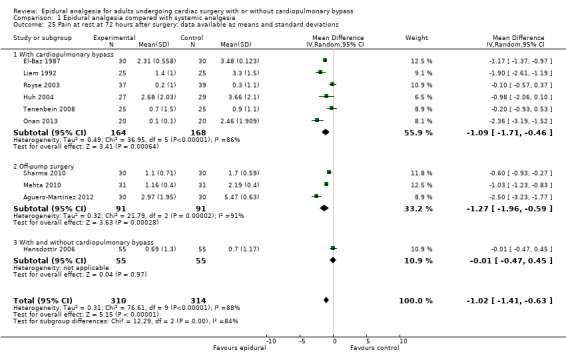

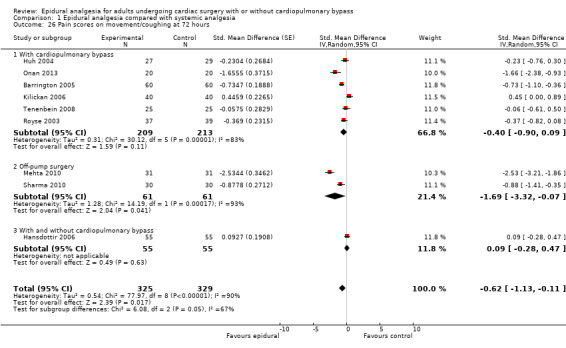

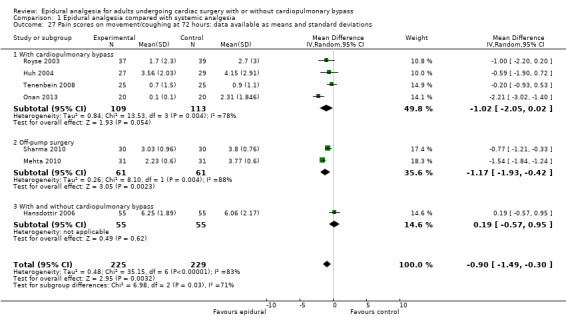

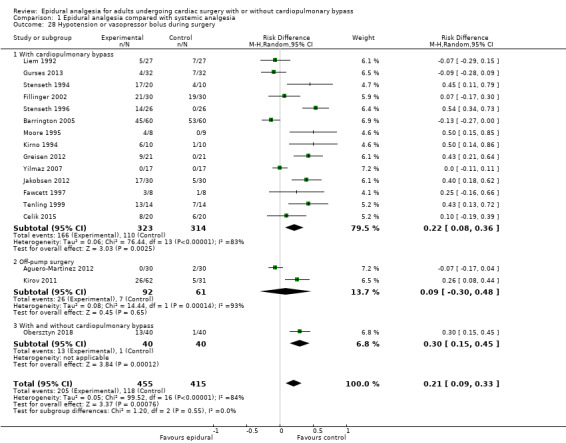

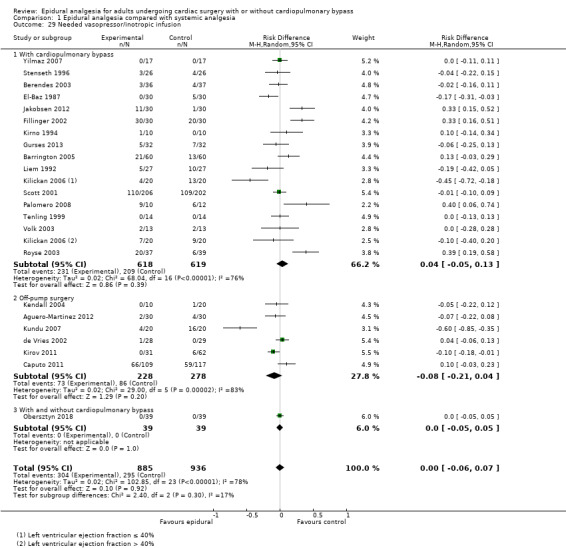

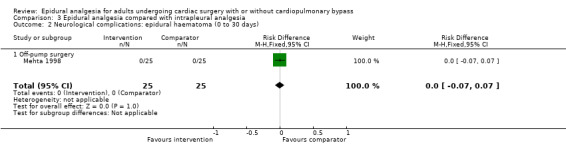

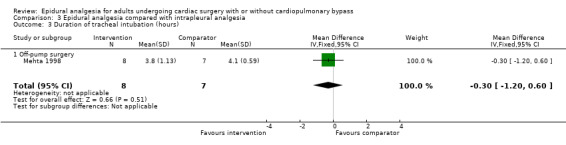

Epidural analgesia versus systemic analgesia

Trials show there may be no difference in mortality at 0 to 30 days (risk difference (RD) 0.00, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.01 to 0.01; 38 trials with 3418 participants; low‐quality evidence), and there may be a reduction in myocardial infarction at 0 to 30 days (RD −0.01, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.00; 26 trials with 2713 participants; low‐quality evidence). Epidural analgesia may reduce the risk of 0 to 30 days respiratory depression (RD −0.03, 95% CI −0.05 to −0.01; 21 trials with 1736 participants; low‐quality evidence). There is probably little or no difference in risk of pneumonia at 0 to 30 days (RD −0.03, 95% CI −0.07 to 0.01; 10 trials with 1107 participants; moderate‐quality evidence), and epidural analgesia probably reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter at 0 to 2 weeks (RD −0.06, 95% CI −0.10 to −0.01; 18 trials with 2431 participants; moderate‐quality evidence). There may be no difference in cerebrovascular accidents at 0 to 30 days (RD −0.00, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.01; 18 trials with 2232 participants; very low‐quality evidence), and none of the included trials reported any epidural haematoma events at 0 to 30 days (53 trials with 3982 participants; low‐quality evidence). Epidural analgesia probably reduces the duration of tracheal intubation by the equivalent of 2.4 hours (standardized mean difference (SMD) −0.78, 95% CI −1.01 to −0.55; 40 trials with 3353 participants; moderate‐quality evidence). Epidural analgesia reduces pain at rest and on movement up to 72 hours after surgery. At six to eight hours, researchers noted a reduction in pain, equivalent to a reduction of 1 point on a 0 to 10 pain scale (SMD −1.35, 95% CI −1.98 to −0.72; 10 trials with 502 participants; moderate‐quality evidence). Epidural analgesia may increase risk of hypotension (RD 0.21, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.33; 17 trials with 870 participants; low‐quality evidence) but may make little or no difference in the need for infusion of inotropics or vasopressors (RD 0.00, 95% CI −0.06 to 0.07; 23 trials with 1821 participants; low‐quality evidence).

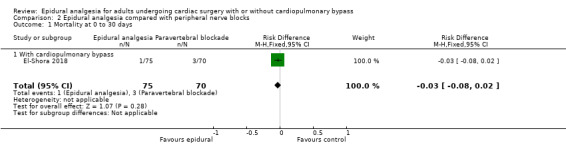

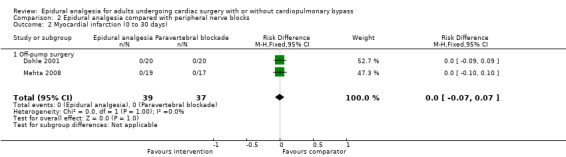

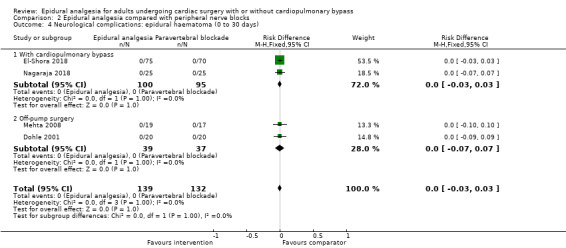

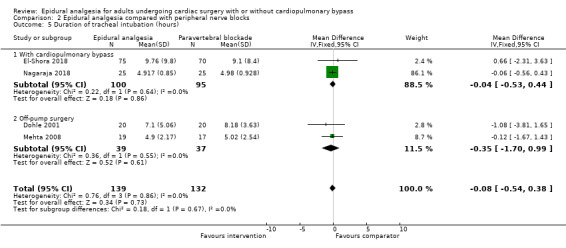

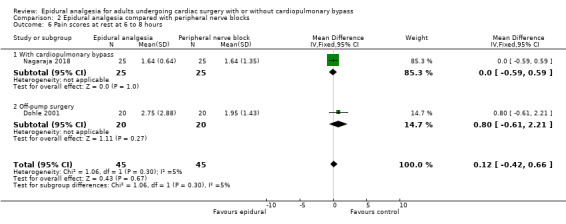

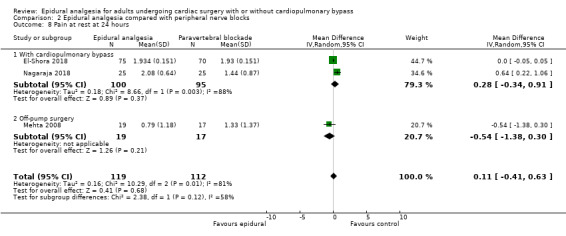

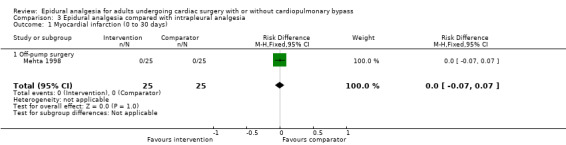

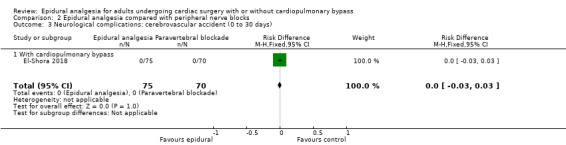

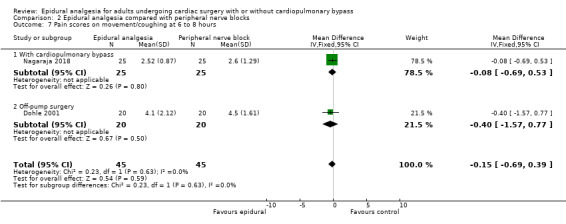

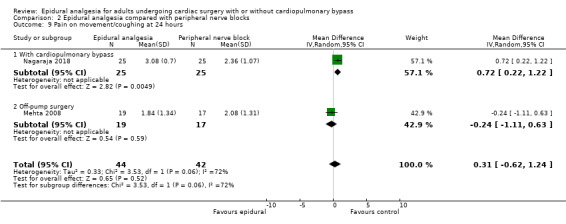

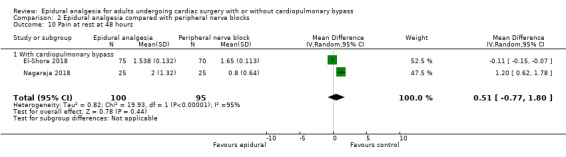

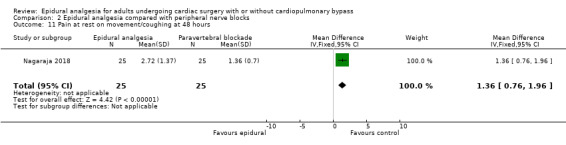

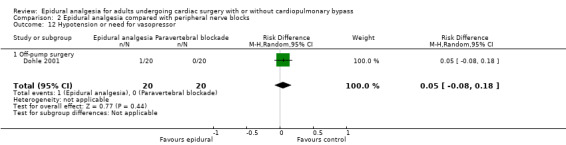

Epidural analgesia versus other comparators

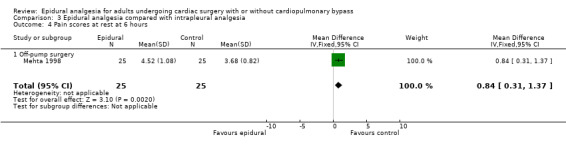

Fewer studies compared epidural analgesia versus peripheral nerve blocks (four studies), intrapleural analgesia (one study), and wound infiltration (one study). Investigators provided no data for pulmonary complications, atrial fibrillation or flutter, or for any of the comparisons. When reported, other outcomes for these comparisons (mortality, myocardial infarction, neurological complications, duration of tracheal intubation, pain, and haemodynamic support) were uncertain due to the small numbers of trials and participants.

Authors' conclusions

Compared with systemic analgesia, epidural analgesia may reduce the risk of myocardial infarction, respiratory depression, and atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter, as well as the duration of tracheal intubation and pain, in adults undergoing cardiac surgery. There may be little or no difference in mortality, pneumonia, and epidural haematoma, and effects on cerebrovascular accident are uncertain. Evidence is insufficient to show the effects of epidural analgesia compared with peripheral nerve blocks, intrapleural analgesia, or wound infiltration.

Plain language summary

Epidural analgesia for heart surgery with or without the heart lung machine in adults

Review question

We set out to determine from randomized controlled trials the effect of epidural pain relief on the number of deaths following surgery and risk of heart, lung, or nerve complications in adults undergoing heart surgery.

This review was first published in 2013, and it was updated in 2019.

Background

For epidural pain relief, a local anaesthetic, an opioid, or a mixture of both drugs is given through a catheter in the epidural space, which is the space immediately outside the membrane surrounding the cord. Epidural analgesia could reduce the risk of complications after surgery, such as lung infections including pneumonia, difficulty in breathing (respiratory failure), heart attack, and irregular heart rhythm caused by atrial fibrillation. A concern is that for cardiac surgery, the blood has to be thinned to reduce blood clotting, which may increase the chance of bleeding around the spinal cord. The collection of blood puts pressure on the spinal cord and can cause permanent nerve damage and disability.

Study characteristics

We included randomized controlled trials involving adults undergoing any type of cardiac surgery under general anaesthesia with or without cardiopulmonary bypass where researchers compared epidural pain relief around the time of surgery against other forms of pain relief. Surgeries performed were coronary artery bypass grafting or valvular procedures and surgeries for congenital heart disease. The average age of participants was between 43 and 75 years. Outcomes were measured up to one year after surgery.

We included 69 studies with 4860 participants. Where stated, the studies were funded by governmental resources (five studies), charity (eight), institutional resources (23), or in part by the industry (two). In all, 31 trials did not mention the source of funding. The evidence is current to November 2018.

Key results

When researchers compared epidural analgesia versus systemic pain relief (e.g. by an analgesic given directly into a vein), they could not detect any difference in the number of deaths in the first 30 days after surgery (38 studies, 3418 participants). There might be a difference in the number of people experiencing heart attacks (26 studies, 2713 participants). These findings were supported by low‐quality evidence. We found a small reduction in the risk of respiratory depression with epidural pain relief (21 studies, 1736 participants), but not in the risk of pneumonia (10 studies, 1107 participants) (low‐ or moderate‐quality evidence). The reduced risk of respiratory depression was more obvious when cardiopulmonary bypass was needed for cardiac surgery. Epidural analgesia reduced the risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter early in recovery at zero to two weeks (18 studies, 2431 participants; moderate‐quality evidence). The number of cerebrovascular accidents was not clearly different (18 studies, 2232 participants), and no lasting neurological complications or epidural haematomas were reported (53 studies, 3982 participants; very low‐ or low‐quality evidence). Although epidural analgesia may have reduced the duration of tracheal intubation, this was noted mainly in older studies, and clinical practices have changed since that time (40 trials, 3353 participants; moderate‐quality evidence).

We found only six studies that compared epidural pain relief versus application of local anaesthetic on the body surface to produce peripheral nerve blocks directly into the space around the lungs (intrapleural analgesia) and onto the surgical wound (wound infiltration). These studies provided low‐ or very low‐quality evidence and did not report on many of the outcomes for this review. Study authors reported no heart attacks and no epidural haematomas.

Quality of the evidence

We rated the quality of evidence as moderate, low, or very low. We included too few participants in our review to rule out any differences in the number of patient deaths between epidural analgesia and systemic analgesia, nor to see any increase in epidural haematomas.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

The addition of thoracic epidural analgesia to general anaesthesia has been suggested to benefit patients after cardiac surgery (Svircevic 2013). However, this regional anaesthetic technique is controversial because the insertion of an epidural catheter in patients requiring full heparinization for cardiopulmonary bypass may lead to an epidural haematoma. The benefits of practicing off‐pump surgery instead of operating with the aid of cardiopulmonary bypass are not recognized by everyone, except perhaps for decreased risk of cerebrovascular accident and for high‐risk patients (Kowalewski 2016). Some clinicians argue that cardiopulmonary bypass induces a more severe inflammatory response. Also, using cardiopulmonary bypass usually requires more complete heparinization than off‐pump surgery. For this reason, we decided to evaluate all our outcomes while subgrouping the data by with or without cardiopulmonary bypass.

Description of the intervention

Epidural analgesia is a technique by which a local anaesthetic or an opioid or a mixture of both drugs is given in the epidural space (Guay 2016a; Guay 2016b; Salicath 2018). Epidural analgesia produces a superior quality of analgesia and may reduce the risk of postoperative complications such as pneumonia, respiratory failure, and myocardial infarction (Guay 2006; Guay 2014; Guay 2016a; Guay 2016b). Epidural analgesia may also shorten the duration of tracheal intubation as well as the time spent in an intensive care unit, which could have economic benefits (Guay 2016b).

How the intervention might work

High thoracic epidural analgesia may provide cardioprotective effects. High thoracic epidural analgesia increases myocardial oxygen availability, as reported in Lagunilla 2006, and reduces myocardial oxygen consumption (Hutchenson 2006). The latter is attributed to an attenuation of sympathetic response to the surgical stimuli (Kirno 1994). An influence on inflammatory response to the surgical stress and/or the cardiopulmonary bypass has also been reported (Volk 2003).

Why it is important to do this review

A possible complication of epidural analgesia includes spinal cord compression caused by a haematoma, which can result in paraplegia (Bos 2018). Systemic anticoagulation is needed for cardiac surgery and may increase the incidence of epidural haematoma related to the use of an epidural catheter (Horlocker 2018). While reviewing the literature, Landoni and colleagues found 25 cases of epidural haematoma out of 88,820 positioned epidurals in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, for an estimated risk of catheter‐related epidural haematoma of 3 per 10,000 procedures (95% confidence interval (CI) 2 to 4 per 10,000 procedures) (Landoni 2015). For the general population, the incidence of haematoma related to an epidural would be 1 per 10,000 procedures (95% CI 0 to 6 per 10,000 procedures) (Moen 2004). Although the incidence found by Landoni and colleagues may seem relatively low, the consequences of this complication may sometimes be catastrophic. In their large trial, Moen and colleagues reported 33 spinal haematomas related to neuraxial blocks. Only 6 of 33 patients made a full recovery, and 27 suffered permanent neurological damage (Moen 2004). It is therefore mandatory to have a clear view of the real benefits of epidural analgesia in cardiac surgery patients, so that patients and clinicians can make an informed decision when choosing the mode of postoperative analgesia.

This is an update of a previously published Cochrane review (Svircevic 2013).

Objectives

To determine the impact of perioperative epidural analgesia in adults undergoing cardiac surgery, with or without cardiopulmonary bypass, on perioperative mortality and cardiac, pulmonary, or neurological morbidity.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs). We excluded observational studies, quasi‐randomized trials, cross‐over trials, and cluster‐randomized trials. We did not exclude studies on the basis of language of publication or publication status.

Types of participants

We included adult participants undergoing general anaesthesia for all types of cardiac surgery with or without cardiopulmonary bypass.

Types of interventions

We included trials that compared cardiac surgery including one group of participants with and one group of participants without epidural analgesia (Table 5). We excluded studies that compared cardiac surgery with participants with and participants without spinal anaesthesia. We included studies in which investigators administered epidural analgesia as a single shot block or as a continuous infusion for any duration and containing a local anaesthetic alone (extended duration or not), or in combination with an opioid (extended duration or not), or an opioid alone. We did not exclude studies in which trialists added an adjuvant other than an opioid to the solution. We excluded trials comparing nerve blocks versus systemic analgesia. For the comparator, we included all other modes of analgesia and divided them into:

1. Postoperative analgesia.

| Study | Regional blockade | Comparator |

| Aguero‐Martinez 2012 | TEA (T3‐T4) with 10 mL bupivacaine 0.5% and morphine 5 mg administered at least 1 hour before IV heparin | Low doses of opioids |

| Bach 2002 | TEA (T12‐L1) inserted the evening before surgery Bupivacaine 0.25% 10 mL Bupivacaine 0.25% ((body height (cm) − 100) × 10‐1 = mL/h) for 18 hours Catheter removed on the second or third day after surgery when coagulation parameters had returned to normal range |

Not reported |

| Bakhtiary 2007 | TEA (T1‐T3; soft multi‐port) inserted the day before surgery 6 mL ropivacaine 0.16% plus sufentanil 1 mcg/mL Ropivacaine 0.16% plus sufentanil 1 mcg/mL at 2 to 5 mL/h started before surgery and continued for 3 days after surgery |

Metamizole and piritramide |

| Barrington 2005 | TEA (T1‐T3) (20‐gauge; Portex, Hythe, Kent, UK) inserted 4 cm cephalad the day before surgery using a midline approach and a loss of resistance to saline technique Ropivacaine 1% 5 mL and fentanyl 50 mcg (adjusted for T1 to T6 sensory block) Ropivacaine 0.2% and fentanyl 2 mcg/mL 5 mL/h started 1 hour after induction and continued until morning of postoperative day 3 (adjusted on pain scores) |

IV morphine infusion and infiltration of chest drain sites |

| Bektas 2015 | TEA (T2‐T4) inserted 5 cm into the epidural space 1 day before surgery Lidocaine 60 mg Levobupivacaine 0.25% 0.1 mL/kg/min and fentanyl 2 mcg/kg/min bolus for T1‐L2 sensory block Levobupivacaine 0.25% 0.1 mL/kg/h and fentanyl 2 mcg/mL |

IV PCA with morphine for 24 hours |

| Berendes 2003 | TEA (C7‐T1) with a median approach and a hanging drop technique inserted the day before surgery 2 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine Bupivacaine 0.5% at 6 to 12 mL/h plus sufentanil 15 to 25 mcg started just before surgery and kept for 4 days |

Not reported |

| Brix‐Christensen 1998 | TEA (T3‐T4) inserted at least 12 hours before surgery Bupivacaine 0.5% 8 mL 30 minutes before induction of anaesthesia Continuous infusion with bupivacaine 2 mg/mL and fentanyl 5 mcg/mL at 5 mL/h during and after surgery until the second postoperative day |

IV morphine |

| Caputo 2011 | TEA (T2‐T4) inserted before surgery Bupivacaine 0.5% 5 + 5 mL Bupivacaine 0.125% plus clonidine 0.0003% 10 mL/hour started after induction and continued for 72 hours (adjusted for T1 to T10 sensory block and on pain scores) |

IV PCA with morphine |

| Celik 2015 | TEA (T5‐T6) inserted the day before surgery Levobupivacaine 2 mcg/mL and fentanyl 10 mcg/mL started at ICU admission at 5 mL/h and maintained for 24 hours |

IV fentanyl infusion at 8 mcg/kg/h for 24 hours |

| Cheng‐Wei 2017 | TEA PCEA with 0.075% bupivacaine and 2 mcg/mL fentanyl |

Wound infusion with 0.15% bupivacaine infused continuously at 2 mL/h through a catheter embedded in the wound plus IV PCA |

| de Vries 2002 | TEA (T3‐T4) placed immediately before induction of anaesthesia

Test dose with 3 to 4 mL of lidocaine 2% with epinephrine 1:200,000 8 to 10 mL bupivacaine 0.25% with sufentanil 25 mcg/10 mL Bupivacaine 0.125% and sufentanil 25 mcg/50 mL given at 8 to 10 mL/h |

Piritramide 0.2 mg/kg intramuscularly on request |

| Dohle 2001 | TEA (T4‐T5) 18G, midline approach, catheter advanced 3 cm past the needle tip Test dose with 3 mL 2% lidocaine Loading with 8 mL 0.5% bupivacaine injected through the catheter, followed by infusion of 0.25% bupivacaine at the rate of 6 mL/h |

Paravertebral blockade, left T4 to T5, loss of resistance with saline, catheter advanced 3 cm past the needle tip Test dose with 3 mL 2% lidocaine Loading with 8 mL 0.5% bupivacaine injected through the catheter, followed by an infusion of 0.25% bupivacaine at the rate of 6 mL/h |

| El‐Baz 1987 | TEA (T3‐T4), epidural catheter (American Pharmaseal Labs, Glendale, CA, USA) inserted by lateral approach Position of the catheter in the epidural space was confirmed by the catheter advancement test (El‐Baz 1984; "After eliciting a lack of resistance to the injection of air through the epidural needle, the ability to advance 20 cm of a soft epidural catheter, without stylet, beyond the vertebral lamina with minimal resistance was indicative of a successful epidural catheterization. After a successful advancement with minimal resistance, the epidural catheter was withdrawn 17‐18 cm leaving 2 ‐3 cm of the catheter in the epidural space and the tip near the spinal segment (T4 ‐ 5) that corresponded to the site of surgical incision. Subdural and intravascular catheterization were excluded by placing the proximal end of the epidural catheter below the site of injection for gravity drainage to assure the absence of cerebrospinal fluid or blood flow through the catheter") Morphine 0.1 mg/h started in ICU |

IV morphine on request |

| El‐Morsy 2012 | TEA (T3‐T4) inserted at least 2 hours before heparinization (change of level if blood in the needle or catheter) Test dose with 3 mL 1.5% lidocaine 0.125% bupivacaine with 1 mcg/mL fentanyl at 5 mL/h and continued until 24 hours postoperatively |

IV tramadol on demand |

| El‐Shora 2018 | TEA (T6‐T7) catheter inserted through a 17G Tuohy needle with loss of resistance technique Bupivacaine 0.125% plus fentanyl 1 mcg/mL 12 mL followed by 12 mL/h for 48 hours and started after surgery |

Ultrasound‐guided bilateral paravertebral blockade at T6‐T7 Bupivacaine 0.125% plus fentanyl 1 mcg/mL 6 mL per side followed by 6 mL/h for 48 hours and started after surgery |

| Fawcett 1997 | TEA (T2‐T4) inserted in operating room 15 mL bupivacaine 0.5% after CPB Bupivacaine 0.375% at 5 to 8 mL/h for 24 hours |

IV morphine infusion for 24 hours |

| Fillinger 2002 | TEA (T3‐T10), catheter inserted before induction of anaesthesia through an 18G Hustead needle using loss of resistance to saline technique and leaving 3 cm of catheter in the epidural space Test dose with 3 mL 1.5% lidocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine Loading with morphine 20 mcg/kg and 0.5% bupivacaine in 5‐mg increments, to a total loading dose of 25 to 35 mg bupivacaine 0.5% bupivacaine with morphine 25 mcg/mL at 4 to 10 mL/h beginning after induction of anaesthesia (adjusted on haemodynamic parameters) Epidural catheters removed on the first postoperative day |

Intravenous morphine, intravenous meperidine, and oral oxycodone |

| Greisen 2012 | TEA (T2‐T4) inserted the day before surgery 5 to 7 mL 5.0 mg/mL bupivacaine (Marcaine, Astra, Södertälje, Sweden) together with sufentanil 2.5 mcg/mL Bupivacaine 2.5 mg/mL and sufentanil 1 mcg/mL 4 to 6 mL/h, by discretion of the attending anaesthesiologist, until end of surgery Changed to bupivacaine 1 mg/mL together with sufentanil 1 mcg/mL in ICU and continued after discharge from ICU until second postoperative day |

Not reported |

| Gurses 2013 | CEA (C6‐C7) (Braun Perifix 20 G) inserted 3 to 4 cm caudally (T2‐T4) at least 1 hour before heparin injection 0.075 mg/kg levobupivacaine hydrochloride (Chirocaine 5 mg/mL, Abbott Lab, Istanbul, Turkey) + 2 mcg/kg fentanyl (fentanyl citrate 50 mcg/mL, Abbott Lab, Istanbul, Turkey) in total 10 mL bolus 0.0375 mg/kg/h levobupivacaine + 0.5 mcg/kg/h fentanyl epidural infusion started with patient‐controlled analgesia instrument (Abbott Pain Management Provider, Abbott Laboratoires, North Chicago, IL, USA) |

Intramuscular diclofenac sodium (Dikloron 75 mg 10 amp, Mefar Drug Ltd, Istanbul, Turkey) |

| Hansdottir 2006 | TEA (T2‐T5) inserted the day before surgery using median hanging drop or loss of resistance technique, 3 to 5 cm into the epidural space Test dose with 4 mL lidocaine 1% PCEA with bupivacaine 0.1% and fentanyl 2 mcg/mL |

IV PCA with morphine |

| Heijmans 2007 | TEA (C7‐T1) by median approach and hanging drop technique Test dose of 2 mL lidocaine 2% Loading dose of 10 mL bupivacaine 0.25% with 2.5 mg morphine infused over 1 hour Bupivacaine 0.125% and morphine 0.2 mg/mL at 1.5 mL/h for 48 hours |

IV piritramide 0.15 mg/kg |

| Huh 2004 | TEA (T4‐T5) inserted the day before surgery Test dose with 3 mL lidocaine 2% and epinephrine 5 to 7 mL bupivacaine 0.15% and fentanyl 50 mcg before skin incision Bupivacaine 0.15% and fentanyl 10 mcg/mL through PCEA for 3 days after surgery |

IV meperidine, tramadol, and NSAIDs |

| Hutchenson 2006 | TEA (T2‐T4) inserted 3 cm the day before surgery with fluoroscopic guidance Bupivacaine 0.5% 200 mcg/cm body height Bupivacaine 0.25% 200 mcg/cm body height per hour |

Not reported |

| Jakobsen 2012 | TEA (T3‐T4) Test dose of 3 mL 2% lidocaine Bolus dose of 5 to 7 mL, guided by primary patient heights, of 0.5% bupivacaine (Marcaine; Astra, Södertälje, Sweden) and sufentanil 2.5 mcg/mL Bupivacaine 2.5 mg/mL/sufentanil 1 mcg/mL, 4 to 6 mL/h during surgery Bupivacaine 1 mg/mL and sufentanil 1 mcg/mL postoperatively and continued after discharge from ICU until second postoperative day |

Participants in both groups received intravenous morphine or alfentanil according to the department’s general guidelines (i.e. morphine 0.05 mg/kg, or alfentanil 25 mcg, if rapid pain relief was needed) All participants in both groups received additional oral or intravenous paracetamol 1 g every 6 hours |

| Kendall 2004 | TEA (T1‐T4) inserted after induction through a paramedian approach and loss of resistance technique 2 mL 0.5% bupivacaine plus epinephrine 0.1 mL/kg 0.1% bupivacaine plus fentanyl 5 mcg/mL followed by infusion at 0.1 mL/kg/h kept for 48 hours |

IV PCA with morphine |

| Kilickan 2006 | TEA (T1‐T5) inserted the day before surgery (3 attempts only) Test dose with 3 to 4 mL 2% lidocaine, position confirmed with injection of contrast material and X‐ray Bupivacaine 20 mg after anaesthesia induction Bupivacaine 0.125% 4 to 10 mL/h intraoperatively and postoperatively for 3 days, adjusted for a sensory blockade from T1 to T10 |

IV PCA with morphine |

| Kilickan 2008 | TEA (T1‐T5) inserted the day before surgery (3 attempts only) Test dose with 3 to 4 mL 2% lidocaine, position confirmed with injection of contrast material and X‐ray Bupivacaine 20 mg 60 minutes before induction of anaesthesia Bupivacaine 20 mg/h intraoperatively and postoperatively for 3 days |

IV PCA with Dolantin |

| Kirno 1994 | TEA (T3‐T4; Perifix, B. Braun, Melsungen AG, Germany) at least 12 hours before surgery Mepivacaine 20 mg/mL (Carbocain, Astra, Södertälje, Sweden) was injected to achieve a T1‐T5 block |

Not reported |

| Kirov 2011 | TEA (T2‐T4) Test dose of 1 mL 2% lidocaine Ropivacaine 0.75% 1 mg/kg and fentanyl 1 mcg/kg for surgery Ropivacaine 0.2% and fentanyl 2 mcg/mL at 3 to 8 mL/h (VAS score < 30 mm at rest) or via PCEA after surgery |

IV fentanyl 10 mcg/mL at 3 to 8 mL/h |

| Konishi 1995 | TEA (T7‐T10) inserted the day before surgery Butorphanol 0.5 to 1.0 mg or Morphine 2.5 mg |

Fentanyl, pentazocine, and minor tranquillizers |

| Kundu 2007 | TEA (C7‐T2) inserted 3 to 4 cm cephaladly before anaesthesia induction with hanging drop technique in left lateral decubitus position Lidocaine 1% 5 mL Bupivacaine 0.25% 5 mL plus fentanyl 10 mcg Bupivacaine 0.25% 5 mL plus fentanyl 10 mcg every 2 hours |

Not reported |

| Kunstyr 2001 | TEA (T1‐T5) inserted at least 60 minutes before heparinization 10 mL bupivacaine 0.5% Bupivacaine 0.125% plus sufentanil 1 mcg/mL infused at 3 to 8 mL/h after surgery |

|

| Lenkutis 2009 | TEA (T1‐T2) Lidocaine 2% 7 to 8 mL Bupivacaine 0.25% at 8 mL/h during surgery Bupivacaine 0.25% and fentanyl 5 mcg/mL at 5 to 7 mL/h for at least 84 hours postoperatively |

IM/IV pethidine 0.1 to 0.4 mg/kg |

| Liem 1992 | TEA (T1‐T2) inserted the day before surgery by paramedian approach and hanging drop technique

Test dose with 2 mL 2% lidocaine Loading with 0.375% bupivacaine plus sufentanil 5 mcg/mL at a dose of 0.05 mL/cm body length administered over a 10‐minute period 0.125% bupivacaine plus sufentanil 1 mcg/mL at 0.05 mL/cm body length/h started before induction and continued for 72 hours |

IV nicomorphine |

| Loick 1999 | TEA (C7‐T1) inserted the day before surgery by median approach and hanging drop technique Test dose with 2 mL bupivacaine 0.5% with adrenaline Loading before induction with 8 to 12 mL bupivacaine 0.375% and 16 to 24 mcg sufentanil into the epidural space in increments to block the somatosensory level C7‐T6 PCEA with bupivacaine 0.75% plus sufentanil 1 mcg/mL if < 65 years of age, and without adjuvant if ≥ 65 years (duration unclear, possibly 48 hours) |

PCA with piritramide |

| Lundstrom 2005 | TEA (T1‐T3) inserted the day before surgery by median approach using hanging drop technique Test dose with 2 mL 2% lidocaine Loading with 8 to 10 mL bupivacaine 0.5% (adjusted for sensory block T1‐T8) before induction Bupivacaine 0.125% and morphine 25 mcg/mL at 5 mL/h plus 4 mL every hour started after induction Bupivacaine 0.25% 4 mL on request after surgery (adjusted for T1‐T8) Catheters removed on day 4 or 5 |

Morphine IV for 24 hours, then orally |

| Lyons 1998 | TEA (C7‐T1) Bupivacaine 0.5% 0.1 mL/kg Bupivacaine 0.1% and fentanyl 2 mcg/mL, infusion for 72 hours |

Not reported |

| Mehta 1998 | TEA (T4‐T5 or T5‐T6) 16G, median approach, loss of resistance to saline, catheter inserted 3 to 4 cm past the needle tip On first demand for pain relief, participants in the TEA group received 8 mL 0.25% bupivacaine hydrochloride Maximum of 3 doses was given over the next 12 hours, if required |

Intrapleural catheter: 16G epidural catheter inserted in intercostal space 6 to 7 cm in left anterior axillary line by the operating surgeon, 6 to 8 cm in intrapleural space, directed posteriorly and anchored with a skin suture before thoracotomy closure On first demand for pain relief, participants in the intrapleural group received 20 mL 0.25% bupivacaine hydrochloride Before injection of intrapleural bupivacaine, participants were positioned supine with a one‐third left lateral tilt and with the intercostal chest tube clamped after exclusion of any air leak. The chest tube was kept clamped for 20 minutes after the injection Maximum of 3 doses was given over the next 12 hours, if required |

| Mehta 2008 | TEA (C7‐T1) hanging drop technique in the sitting position, catheter inserted 4 cm beyond needle tip Lidocaine 2% 3 mL Bupivacaine 0.5% 8 mL Bupivacaine 0.25% at 0.1 mL/kg/h |

Paravertebral blockade Loss of resistance to saline at left T4‐T5 Lidocaine 2% 3 mL Bupivacaine 0.5% 8 mL Bupivacaine 0.25% at 0.1 mL/kg/h |

| Mehta 2010 | TEA (C7‐T1) using hanging drop technique in sitting position inserted at least 2 hours before heparinization; intervention postponed in cases of bloody tap 3 mL 2% lidocaine without epinephrine; adequacy and level of the block established by confirming loss of pin‐prick sensation and warm/cold discrimination 8 to 10 mL 0.25% bupivacaine (aim at T4 sensory block) Bupivacaine infusion (0.125%) with fentanyl citrate (1 mcg/mL) at the rate of 5 mL/h was commenced and continued until postoperative day 3 to provide intraoperative and postoperative analgesia |

Not reported |

| Mishra 2004 | No details available | Not reported |

| Moore 1995 | TEA (T1‐T5) Bupivacaine 0.5% in 2 mL increments for sensory block from T1 to L2 Bupivacaine 0.375% at 5 to 8 mL/h started before induction Bupivacaine 0.25% at 5 to 8 mL/h for at least 24 hours |

IV papaveretum |

| Nagaraja 2018 | TEA (C7‐T1) inserted (3 to 4 cm caudally) the day before surgery through an 18G Tuohy needle 0.25% plain bupivacaine 15 mL before surgery followed by 0.125% plain bupivacaine at 0.1 mL/kg/h for 48 hours post extubation |

Ultrasound‑guided (in‐plane) erector spinae plane lock Catherer inserted 5 cm cephaladly the day before surgery through an 18G Tuohy needle. 3 cm lateral to T6 spinous process (T5 transverse process) with hydrodissection below the erector spinae muscle with 5 mL normal saline, 0.25% plain bupivacaine, 15 mL in each catheter before surgery, followed by 0.125% plain bupivacaine at 0.1 mL/kg/h for 48 hours post extubation, through each catheter |

| Neskovic 2013 | TEA (T2‐T4) inserted 30 minutes before surgery and at least 2 hours before the first dose of heparin Test dose 10 to 15 mL 0.125 or 0.25% bupivacaine with fentanyl 0.125 or 0.25% bupivacaine with fentanyl at 5 to 10 mL/h |

Not reported |

| Nygard 2004 | TEA (T1‐T3) inserted the day before surgery by the median approach and hanging drop technique Test dose with 2 mL 2% lidocaine Loading with 8 to 10 mL bupivacaine 05% before induction (adjusted for T1 to T8) Bupivacaine 0.125% with morphine 25 mcg/mL at 5 mL/h started after induction and continued for 4 days Additional bolus doses of 4 mL bupivacaine 0.5% hourly during the operation |

Morphine IV for 24 hours, then orally |

| Obersztyn 2018 | TEA (T1‐T3) with hanging drop technique, catheters inserted 3 to 4 cm into the epidural space at least 6 hours before surgery Before surgery: 9 to 11 mL 0.25% bupivacaine with fentanyl in a concentration of 10 mcg/mL, followed by 0.19% (more exactly, 0.1875%) bupivacaine and fentanyl at 6 mL/h during surgery and 0.125% bupivacaine plus fentanyl 6.25 mcg/mL at 2 to 8 mL/h after surgery until discharge fro the ICU (mean 18.8 hours) |

IV morphine |

| Onan 2011 | TEA (T2‐T4; side‐holed 18 G epidural catheter) by using a median approach and a loss of resistance technique with saline solution Test dose with 3 to 4 mL 2% lidocaine 20 mg bolus 0.25% bupivacaine through the epidural catheters 1 hour before surgery 0.25% bupivacaine infused at a rate of 20 mg/h during surgery 0.125% bupivacaine at 4 to 10 mL/h after surgery (adjusted for T1‐T10) Epidural catheters removed at 24 hours postoperatively |

Not reported |

| Onan 2013 | TEA (T1‐T5) inserted the night before surgery 3 cm into epidural space Test dose with 3 to 4 mL 2% lidocaine Sensory blockade tested with ice plus X‐ray after injection of contrast material Bolus of 20 mg 0.25% bupivacaine 1 hour before surgery 20 mg/h 0.25% bupivacaine intraoperatively Bupivacaine 0.25% 10 to 20 mL/h during first 24 hours after surgery (adjusted according to pain scores) |

Acetaminophen (500 mg) and tramadol (1 mg/kg) used as rescue medications |

| Palomero 2008 | TEA (T3‐T6) inserted the day before surgery Bolus of 6 to 8 mL 0.33% bupivacaine 0.175% bupivacaine 6 to 8 mL/h for 48 hours Catheter withdrawn after check of coagulation status |

Morphine 0.5 to 1 mL/h |

| Petrovski 2006 | TEA; no details | Not reported |

| Priestley 2002 | TEA (T1‐T4; 18G side‐holed epidural catheter) inserted the evening before surgery Test dose with 2% lidocaine 3 to 4 mL Loading with 4 mL ropivacaine 1% and fentanyl 100 mcg (adjusted for T1‐T6) Ropivacaine 1% and fentanyl 5 mcg/mL at 3 to 5 mL/h started before induction and continued for 48 hours |

Continuous morphine infusion for 24 hours, followed by PCA with morphine |

| Rein 1989 | TEA (T4‐T5) Bupivacaine 0.5% 10 mL at induction of anaesthesia and 4 mL every hour during surgery Bupivacaine 0.5% at 4 mL/h for 24 hours |

Morphine |

| Royse 2003 | TEA (T1‐T3) inserted the night before the operation 8 mL bupivacaine 0.5% with fentanyl 20 mcg before induction Ropivacaine 0.2% with fentanyl 2 mcg/mL at 5 to 14 mL/h (for T1‐T10 sensory block) and continued until postoperative day 3, 6H00 AM |

PCA with morphine |

| Scott 2001 | TEA (T2‐T4) inserted before induction Loading with bupivacaine 0.5% 2 boluses of 5 mL (for T1‐T10) Bupivacaine 0.125% and 0.0006% clonidine at 10 L/h started after induction and continued for 96 hours (adjusted on pain scores and sensory block) |

Target controlled infusion of alfentanil for 24 hours followed by PCA with morphine for another 48 hours (adjusted on pain scores) |

| Sen 2017 | TEA (T2‐T4) inserted 4 to 6 cm into epidural space the day before surgery Lidocaine 2% with epinephrine 5 mcg/mL 3 mL Bupivacaine 0.1% and fentanyl 2 mcg/mL at 0.1 mL/kg/h started after induction |

IV fentanyl 0.5 to 2 mcg/kg/h IV tramadol 100 mg as rescue analgesia |

| Sharma 2010 | TEA (C7‐T2) inserted at least 2 hours before heparinization and using hanging drop technique via midline approach Test dose 3 mL 2% lignocaine without epinephrine Loading with 8 to 10 mL bupivacaine 0.25% (for sensory block until at least T4) before induction Bupivacaine 0.125% with 1 mcg/mL fentanyl citrate at 5 mL/h started after induction and continued until third postoperative day |

IV continuous infusion of tramadol |

| Stenseth 1994 | TEA (T4‐T6) inserted the day before surgery Test dose with lidocaine 10 mL bupivacaine 0.5% before induction 4 mL bupivacaine 0.5% hourly during surgery Bupivacaine 0.5% at 3 mL/h plus 4 mL every 4 hours after surgery |

IV morphine on request |

| Stenseth 1996 | TEA (T4‐T6) inserted the day before surgery Test dose with lidocaine 10 mL bupivacaine 0.5% before induction (for at least T1‐T2 block) 4 mL bupivacaine 0.5% hourly during surgery Bupivacaine 0.5% at 3 mL/h plus 4 mL every 4 hours after surgery Morphine epidurally 4 to 6 mg 3 to 4 times a day for the next 2 days, supplemented with bupivacaine 5 mg/mL when needed until third postoperative day |

IV morphine on request |

| Stritesky 2006 | TEA (T2‐T4) 1 hour before surgery with an 18G Tuohy needle and hanging drop or loss of resistance technique, with catheter inserted 4 cm past the needle tip 10 mL bupivacaine 0.25% plus fentanyl 100 mcg for loading (half through the needle and half through the catheter) Bupivacaine 0.25% and fentanyl 1 mcg/mL at 8 to 12 mL/h during surgery and for 48 hours |

Not reported |

| Svircevic 2011 | TEA (T2‐T4) at least 4 hours before heparinization Test dose with lidocaine 2% 3 mL 0.1 mL/kg administered of a solution of 0.08 mg/mL morphine and 0.125% bupivacaine, followed by continuous infusion of 4 to 8 mL/h of the same solution started before induction Epidural catheter removed before transfer to the general ward (median 22 hours) |

Morphine IV infusion |

| Tenenbein 2008 | TEA (T2‐T5) inserted at least 4 hours before systemic heparinization 2.5 mL test dose of 2% lidocaine, with 1:200,000 epinephrine on insertion 3 mL test dose of 2% lidocaine before surgery 0.75% ropivacaine 5 mL with hydromorphone 200 mcg followed by an infusion of ropivacaine 0.75% at 5 mL/h during surgery 0.2% ropivacaine with hydromorphone 15 mcg/mL for 48 hours after surgery |

IV PCA with morphine Indomethacin suppositories (100 mg) postoperatively, and twice‐daily naproxen (500 mg) |

| Tenling 1999 | TEA (T3‐T5; 16G), inserted the day before surgery through the lateral approach and loss of resistance technique with saline 0.9% Test dose of 2 to 3 mL lidocaine 1% 8 to 12 mL bupivacaine 0.5% the morning of the operation (for T1‐T8 sensory block) Bupivacaine 0.5% at 4 to 8 mL/h until ICU admission Bupivacaine 0.2% and sufentanil 1 mcg/mL at 3 to 7 mL/h from arrival to ICU until the day after the operation |

IV ketobemidone |

| Usui 1990 | TEA (T6‐T7) inserted 4 cm past needle tip 24 hours before surgery and kept for 1 or 2 days after extubation Morphine 3 mg given after surgery and repeated as required |

Morphine 10 mg IV as required Additional co‐analgesia as required |

| Volk 2003 | TEA (C7‐T3) inserted the day before surgery Lidocaine 2% for T1‐T6 sensory block Bupivacaine 0.5% 6 to 10 mL hourly during surgery Bupivacaine 0.25% at 6 to 12 mL/h for at least 24 hours |

IV patient‐controlled analgesia with piritramide |

| Yang 1996 | TEA (T4‐T5) inserted 3 cm cephalad in the right lateral decubitus position Lidocaine 2% 3 mL Bupivacaine 0.375% and fentanyl 5 mcg/mL 0.06 mL/cm of body length Bupivacaine 0.25% with fentanyl 5 mcg/mL 0.03 mL/cm of body length every hour |

Not reported |

| Yilmaz 2007 | TEA (T3‐T6) inserted cranially 3 to 4 cm 16 to 24 hours before systemic heparinization (Perifix 18G, Braun) Loading with morphine 5 mcg/kg and 6 mL bupivacaine 0.25% at least 45 minutes before surgical incision 6 mL bupivacaine 0.12% with fentanyl 2.5 mcg/kg every 6 hours for 48 hours, after which catheters were withdrawn |

IV fentanyl 0.7 mcg/kg/h |

| Yung 1997 | TEA or upper lumbar epidural inserted 24 hours before surgery Lidocaine 1.5% 25 to 30 mL with ketamine 15 mg, morphine 1 mg/10 kg for surgery Morhine 1 mg in 10 mL normal saline every 12 hours for 5 days for postoperative analgesia |

IV meperidine HCl |

| Zawar 2015 | TEA (C7‐T2) catheters inserted 4 to 5 cm cranially using hanging drop technique If a “bloody tap” was to occur, the operation was postponed for 24 hours and participant was excluded from the study Bolus of 6 to 14 mL ropivacaine 0.75% for T1‐T10 sensory block (sensory loss to cold pack and needle prick) Infusion of 5 to 15 mL/h ropivacaine 0.2% for 72 hours after surgery |

IV tramadol hydrochloride 100 mg 8 hourly |

| Zhou 2010 | TEA (T4‐T6) inserted in lateral decubitus position the day before surgery Bolus 8 to 20 mL lidocaine 1% PCEA with ropivacaine 0.125% and fentanyl 2 mcg/mL at 4 mL/h plus 2 mL bolus (lockout time 20 minutes) |

IV PCA with fentanyl |

CEA: cervical epidural analgesia; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; ICU: intensive care unit; NSAIDs: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs; PCA: patient‐controlled analgesia; PCEA: patient‐controlled epidural analgesia; TEA: thoracic epidural analgesia; VAS: visual/verbal analogical pain score.

all forms of systemic analgesia (opioid‐based regimen or other), regardless of the route of administration (intravenous (with or without a self‐administered patient‐controlled device), intramuscular, or oral analgesia);

peripheral nerve blocks;

intrapleural analgesia; and

wound infiltration.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Risk of mortality (0 to 30 days, six months, and one year)

Secondary outcomes

Risk of myocardial infarction (0 to 30 days; study author's definitions (Table 6))

-

Risk of pulmonary complications

Riisk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter during surgery and up to two weeks after surgery

-

Risk of neurological complications

Cerebrovascular accident (0 to 30 days; study author's definitions (Table 8))

Risk of serious neurological complications from epidural analgesia (lasting (> 3 months) sensory or motor deficit) or epidural haematoma (with or without epidural analgesia) (0 to 30 days)

Duration of tracheal intubation (Table 9)

Pain scores (rest and movement at 6 to 8, 24, 48, and 72 hours)

-

Haemodynamic support (in hospital)

Hypotension or need for vasopressor boluses

Inotropic or vasopressor infusions

2. Diagnostic criteria for myocardial infarction.

| Study | Criteria |

| Aguero‐Martinez 2012 | New pathological Q wave (duration ≥ 0.04 second and depth ≥ 25% of the R wave or QRS complex) in more than 1 derivation. Non‐specific changes that included elevation of the ST segment > 1.5 mm from the isoelectric line in 2 or more leads of the same region, ST depression > 2 mm in the precordial leads, or reversal of the T wave for longer than 48 hours; absence of R wave in the precordial leads. Ventricular or atrioventricular conduction defects Enzymatic criteria: 5 times normal values: troponin > 1 mcg/mL, CK > 250 U/L, CK‐MB > 133 U/L, LDH > 800 U/L, LDH 1/LDH 2 > 1 in blood samples collected between postoperative days 2 and 3, and GOT > 90 U/L Echocardiographic criteria: new segmental motility disorders Anatomopathological criteria: in dead patients |

| Bakhtiary 2007 | Unspecified |

| Barrington 2005 | Transmural infarction defined as new Q waves |

| Bektas 2015 | 1. Cardiac biomarkers (with troponins preferred) rise > 10 times 99% upper reference limit (URL) from normal preoperative level 2. New pathological Q waves or new left bundle branch block (LBBB) and/or imaging or angiographic evidence of new occlusion of native vessels or grafts, new regional wall motion abnormality, or loss of viable myocardium |

| Caputo 2011 | New Q waves of 0.04 ms and/or reduction in R waves > 25% in at least 2 contiguous leads on ECG |

| Celik 2015 | ECG monitored (ST analysis); CK‐MB and troponin I levels measured at fourth and 24th hours |

| de Vries 2002 | Myocardial infarction defined as a new Q wave on ECG and CK 180 U/L with CK‐MB 10% of total |

| Dohle 2001 | Myocardial infarction assessed by ECG changes and CK‐MB values |

| Fillinger 2002 | New Q waves of at least 0.04 second duration or postoperative elevation of serum creatine phosphokinase confirmed by creatine phosphokinase isoenzyme pattern |

| Hansdottir 2006 | New Q waves or CK‐MB isoenzyme concentration ≥ 50 |

| Heijmans 2007 | Myocardial infarction not mentioned in the report |

| Jakobsen 2012 | Perioperative myocardial infarction, defined as new Q waves of 0.04 ms and/or reduction in R waves > 25% in at least 2 contiguous leads on ECG |

| Kendall 2004 | ECG changes (new Q wave, or loss of R wave progression, or new permanent left bundle branch block) and increase in creatinine kinase myocardial fraction (CK‐MB) to > 120 units per litre |

| Kilickan 2006 | Unspecified |

| Liem 1992 | CK‐MB values ≥ 80 IU/L and evidence of new Q waves or bundle branch block on postoperative ECG |

| Loick 1999 | Unclear |

| Lyons 1998 | Unclear |

| Mehta 1998 | Incidence of perioperative myocardial infarction also analysed by an independent cardiologist, as per the appearance of new Q waves in the ECG and increase in creatine phosphokinase‐myocardial band isoenzyme (CPK‐MB) levels to > 70 ng/mL in the first 12 hours postoperatively |

| Mehta 2010 | 2‐lead ECG and CPK, CPK‐MB levels |

| Neskovic 2013 | New ECG changes with positive enzymes (CK‐MB and troponin) |

| Obersztyn 2018 | ECG and elevated serum enzymes |

| Onan 2011 | Unspecified |

| Onan 2013 | Unspecified |

| Palomero 2008 | Myocardial infarction defined by analysis of the ECG (new Q waves or increases in ST segment > 3 mm) |

| Priestley 2002 | New Q waves (assessed by the blinded cardiologist) on a 12‐lead ECG on days 0, 1, 2, and 4 and assessment of venous blood levels of troponin T and creatine kinase‐MB fraction on arrival in the ICU, and again at 4, 12, and 24 hours and on postoperative day 2 |

| Scott 2001 | Q waves, ST segment increase of 3 mm, and a myocardial specific serum creatinine kinase level ≥ 60 ng/mL |

| Stenseth 1994 | Unspecified |

| Stenseth 1996 | Unspecified |

| Svircevic 2011 | Creatine kinase muscle–brain isoenzymes > 75 units per litre (5 times upper limit of normal level) and peak creatine kinase muscle–brain isoenzyme/creatine kinase ratio > 10% or new Q wave infarction |

| Zawar 2015 | Myocardial infarction defined as developing ECG changes, new Q waves on postoperative ECG ≥ 0.03 second in duration in 2 or more adjacent leads lasting until discharge, rise in creatine phosphokinase‑MB and troponin I, and new regional wall motion abnormalities |

CK: creatinine kinase; CK‐MB: creatinine kinase muscle brain; ECG: electrocardiogram; GOT: glutamic‐oxaloacetic transaminase; LBBB: left bundle branch block; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; URL: upper reference limit.

3. Diagnostic criteria for pulmonary complications.

| Study | Criteria |

| Aguero‐Martinez 2012 | Respiratory depression |

| Barrington 2005 | Respiratory depression: reintubation |

| Berendes 2003 | Respiratory depression: need of ICU 24 hours due to intermittent respiratory insufficiency |

| Caputo 2011 | Pneumonia: presence of purulent sputum associated with fever and requiring antibiotic therapy according to positive sputum culture |

| Celik 2015 | Respiratory depression: PaCO₂ and PO₂ measurements at baseline and at first, sixth, and 12th hours were followed Pneumonia: fever, C‐reactive protein, leukocyte values, and chest radiography were assessed |

| de Vries 2002 | Respirarory depression: respiratory acidosis Pneumonia: criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| El‐Baz 1987 | Respiratory depression: respiratory insufficiency requiring intubation and ventilatory support |

| Fillinger 2002 | Respiratory depression: need for mechanical ventilation for 24 hours after surgery or clinical decision to initiate mechanical ventilation after initial tracheal extubation Pneumonia: positive sputum culture and chest radiograph changes |

| Hansdottir 2006 | Respiratory depression: postoperative mechanical ventilation for longer than 24 hours or need for non‐invasive positive‐pressure ventilation Pneumonia: defined as pulmonary infiltrate with positive microbial cultures from sputum or fever, high leukocyte count, or high levels of C‐reactive protein |

| Kunstyr 2001 | Respiratory depression: 8 or fewer breaths per minute and PaCO₂ > 55 kPa |

| Liem 1992 | Respiratory depression: no details provided |

| Lundstrom 2005 | Respiratory depression: constant hypoxaemia on third night after surgery |

| Mehta 2010 | Respiratory depression: no details provided |

| Neskovic 2013 | Respiratory depression: need for re‐intubation Pneumonia: febrile state, with new chest radiography findings |

| Obersztyn 2018 | Respiratory depression: need for respiratory support after extubation |

| Onan 2013 | Pneumonia: no details provided |

| Royse 2003 | Respiratory depression: need for non‐invasive respiratory support or re‐intubation |

| Scott 2001 | Respiratory depression: respiratory failure requiring tracheal re‐intubation or prolonged mechanical ventilation (> 24 hours) Pneumonia: combination of increased white cell count, pyrexia, productive sputum, radiological signs, and positive bacterial growth on culture |

| Tenenbein 2008 | Respiratory depression: no details provided Pneumonia: no details provided |

| Yilmaz 2007 | Pneumonia: respiratory infection |

| Yung 1997 | Respiratory depression: re‐intubation |

| Zawar 2015 | Respiratory depression: re‐intubation |

ICU: intensive care unit; kPa: kilopascal; PaCO₂: partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO₂: partial pressure of oxygen.

4. Diagnostic criteria for neurological complications: cerebrovascular accident.

| Study | Neurological complication |

| Aguero‐Martinez 2012 | Neurological complication: any new‐onset psychiatric or neurological disorder with altered consciousness with or without focalization |

| Barrington 2005 | Stroke |

| Bektas 2015 | Stroke: All participants were postoperatively managed in the cardiac surgery intensive care unit. Postoperative stroke was suspected when a patient showed focal neurological deficits or delayed recovery of mental status after surgery. Such patients were referred to stroke neurologists and were evaluated by computed tomography. Post coronary artery bypass grafting, stroke was diagnosed as: 1) newly developed neurological deficits within 14 days of coronary artery bypass grafting; and 2) Low‐density lesions on postoperative computed tomography that were not observed preoperatively. Strokes that occurred within 24 hours after coronary artery bypass grafting were defined as immediate, whereas all others were considered delayed |

| Caputo 2011 | Stroke/transient ischaemic attack: diagnosis of stroke was made if evidence showed new neurological deficit with morphological substrate confirmed by computed tomography or nuclear magnetic resonance imaging |

| Celik 2015 | Stroke: neurological findings of participants (hemiparesis, hemiplegia, etc.) were followed |

| Fillinger 2002 | Neurological event: new sensorimotor neurological events |

| El‐Shora 2018 | Stroke |

| Hansdottir 2006 | Stroke: defined as a new central neurological deficit |

| Heijmans 2007 | Stroke |

| Jakobsen 2012 | Transitory Ischaemic attack lasting less than 24 hours |

| Neskovic 2013 | Stroke: new motor or sensory deficit after surgery |

| Onan 2013 | Cerebrovascular accident |

| Palomero 2008 | Focal neurological dysfunction defined as a sensory or motor deficit affecting 1 or more limbs appearing 5 days after surgery |

| Royse 2003 | Stroke |

| Scott 2001 | Cerebrovascular accident defined as a new motor or sensory deficit affecting 1 or more limbs and present on awakening from anaesthesia or occurring within the next 5 days |

| Stenseth 1996 | Hemiparesis |

| Svircevic 2011 | Stroke: a new motor or sensory deficit of central origin, persisting longer than 24 hours, preferably confirmed by computed tomography, resulting in a drop of 2 points on the Rankin scale |

| Tenenbein 2008 | Stroke or transient ischaemic attack |

| Zawar 2015 | Stroke was documented if diagnosed on computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging |

5. Criteria for tracheal extubation.

| Study | Criteria |

| Aguero‐Martinez 2012 | Adequate response to verbal commands, pulse oximetry 95% with FiO₂ 0.5, PaCO₂ 45 mmHg in spontaneous respiration, respiratory rate between 10 and 20/min, regular thoracic movements with tidal volume > 5 mL/kg, temperature > 36°C, stable haemodynamic parameters, and no surgical complications |

| Bakhtiary 2007 | Not reported |

| Barrington 2005 | Anaesthesiologist tracheally extubated participants in the operating room if extubation criteria—respiratory rate 10 to 20 breaths/min, responsiveness to voice, end‐tidal CO₂ 50 mmHg, SaO₂ 94% with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 1.0, haemodynamic stability, minimal chest drain output (not requiring transfusion or consideration for surgical re‐exploration), and temperature 35.9°C—were achieved within 30 minutes. For participants not extubated in the operating room, postoperative management of ventilation and extubation followed existing unit guidelines. Participants were required to respond appropriately to voice, have an acceptable ventilatory pattern and arterial blood gas analysis, and be haemodynamically stable |

| Berendes 2003 | Weaning the participant from the respirator and extubation were performed according to standard procedures |

| Caputo 2011 | Not reported |

| Celik 2015 | Not reported |

| de Vries 2002 | Extubation criteria were normothermia, haemodynamic stability, ability to respond to verbal commands, and respiratory rate of at least 8 breaths/min with peripheral oxygen saturation of at least 94% |

| Dohle 2001 | Extubated whenever they qualified for extubation |

| El‐Baz 1987 | Not reported |

| El‐Morsy 2012 | Extubation criteria included an adequate level of consciousness and muscle strength, stable cardiovascular status, normothermia, adequate pulmonary function (PaO₂ > 80 mmHg with fraction of inspired oxygen ≤ 0.4), and minimal thoracotomy tube output |

| Fillinger 2002 | Endotracheal extubation was managed by ICU staff following standardized criteria. ICU extubation criteria included an adequate level of consciousness and muscle strength, stable cardiovascular status, normothermia, adequate pulmonary function (PaO₂ 80 mmHg with fraction of inspired oxygen 0.4), and minimal thoracostomy tube output |

| Gurses 2013 | Participants were extubated when they completely recovered and regained muscular power (Aldrete’s recovery score = 9, PaCO₂ < 45 mmHg, PaO₂ > 100 mmHg, FiO₂ = 0.4, and pH between 7.35 and 7.45, together with stable haemodynamic and metabolic parameters) |

| Hansdottir 2006 | Participants underwent extubation when they fulfilled the following criteria.

|

| Huh 2004 | Participants were extubated when they were awake (eyes opened and able to follow orders), were haemodynamically stable, and had normal arterial blood gases with FiO₂ ≤ 0.3 |

| Jakobsen 2012 | Extubation was performed when the participant was awake and without pain following objective criteria such as a spontaneous respiratory rate of 10 to 16, a core temperature of 36°C, a normal acid/base balance with pH between 7.34 and 7.45, PaO₂ of 10 kPa with FiO₂ 40% and maximum positive end‐expiratory pressure 5 cm H₂O, PaCO₂ 6 kPa, drainage 100 mL/h in the 2 following hours, together with stable haemodynamics, which were considered present with 20% change in cardiac index, SvO₂, and mean arterial pressure over the last hour |

| Kendall 2004 | Intermittent positive‐pressure ventilation was continued until the participant met the following minimum criteria for extubation: haemodynamic stability with blood loss < 120 mL/h, core temperature > 36°C, responsive, co‐operative, and pain‐free |

| Kilickan 2006 | Participants were extubated when they met set criteria as assessed by the ICU nursing staff: not in pain or agitated, cardiovascular stability without inotropes, systolic pressure > 90 mmHg, core temperature > 36.4°C, spontaneous ventilation with PaO₂ > 12 kPa on FiO₂ < 0.4 and PaCO₂ < 7 kPa, blood loss from chest drains < 60 mU/h, urine output > 1 mL/kg/h |

| Kilickan 2008 | Participants were extubated when they met set criteria as assessed by the ICU nursing staff: not in pain or agitated, cardiovascular stability without inotropes, systolic pressure > 90 mmHg, core temperature > 36.4°C, spontaneous ventilation with PaO₂ > 12 kPa on FiO₂ < 0.4 and PaCO₂ < 7 kPa, blood loss from chest drains < 60 mU/h, urine output > l mL/kg/h |

| Kirov 2011 | Extubation criteria were the following: a co‐operative, alert participant; adequate muscular tone; SpO₂ > 95% with FiO₂ 0.5; PaCO₂ < 45 mmHg; stable haemodynamics without inotrope/vasopressor support; absence of arrhythmias; and body temperature > 35°C. Temporary pacing was not regarded as a contraindication to extubation |

| Konishi 1995 | Not reported in partial translation |

| Kunstyr 2001 | Not reported |

| Lenkutis 2009 | Participants were extubated according to conventional clinical criteria: bleeding < 50 mL/h, stable haemodynamics, SpO₂ > 95% on FiO₂ 50%, awake enough to follow commands |

| Liem 1992 | Participants were extubated when they fulfilled the following criteria: responsive to verbal stimuli; respiratory rate per minute ≥ 10 and ≤ 25; SaO₂ ≥ 95%; breathing adequately via endotracheal tube with 5 L/min of oxygen (pH 7.30 to 7.40; PaO₂ ≥ 10 kPa; PaCO₂ ≤ 6.5 kPa); rectal temperature ≥ 36°C and temperature "p" ("p" not defined in report) ≥ 31°C; haemodynamically stable; chest and mediastinal tube output ≤ 2 mL/kg/h; and urine output ≥ 0.5 mL/kg/h |

| Loick 1999 | Participants were tracheally extubated as soon as they fulfilled extubation criteria: sufficient spontaneous ventilation, existing protective reflexes |

| Mehta 1998 | Not reported |

| Mehta 2008 | After surgery, participants were transferred to the recovery room and were extubated when they qualified for extubation |

| Mehta 2010 | Extubation criteria included haemodynamic stability with systolic blood pressure ≥ 100 mmHg (without inotropes and/or vasopressors), core temperature ≥ 36°C, spontaneous ventilation with PaO₂ ≥ 100 mmHg on FiO₂ = 0.4 and PaCO₂ ≤ 40 mmHg, blood loss from chest drains < 50 mL/h, and urine output > 1 mL/kg/h |

| Onan 2013 | All participants were extubated in the ICU after rewarming and haemodynamic stabilization. Participants were extubated using clinical criteria together with analytical criteria (PaO₂) with the participant breathing through a T piece. The decision was made by the consultant on call |

| Palomero 2008 | Extubation time was calculated starting from the moment the participant was transferred to the ICU |

| Petrovski 2006 | Not reported |

| Priestley 2002 | Participants in the ICU were weaned from positive‐pressure ventilation and were extubated when they met set criteria as assessed by the ICU nursing staff: participant responsive to voice, oxygen saturation > 94% on inspired oxygen concentration < 50%, respiratory rate < 20 breaths/min and no obvious respiratory distress, PaCO₂ < 50 mmHg, pH > 7.3, tidal volume > 7 mL/kg on pressure support < 12 cm H₂O above end‐expiratory pressure, temperature > 36.0°C, chest tube drainage < 100 mL/h, haemodynamic stability (i.e. not requiring significant inotropic support and no uncontrolled arrhythmia) |

| Royse 2003 | Extubation was performed when the participant was awake, co‐operative, normothermic (core body temperature 36°C), pH 7.3, and PaO₂ > 75 mmHg on 40% inspired oxygen |

| Sharma 2010 | Once participants were awake with adequate spontaneous ventilation and a stable haemodynamic state, they were weaned off the ventilator and the trachea was extubated. Extubation criteria were as follows: haemodynamic stability with mean arterial pressure > 60 mmHg (without or with minimal inotropes and/or vasopressors), core temperature ≥ 36°C, spontaneous ventilation with PaO₂ > 100 mmHg on FiO₂ ≤ 0.4 and PaCO₂ < 40 mmHg, blood loss from chest drains < 50 mL/h, and urine output > 1 mL/kg/h |

| Stenseth 1996 | Participants were extubated when awake, with adequate spontaneous ventilation (PaCO₂ < 6 kPa, PaO₂ > 10 kPa at FiO₂ = 0.6), and when in a stable haemodynamic state |

| Svircevic 2011 | Participants were extubated as soon as extubation criteria were met: core temperature > 36°C, difference core/skin temperature < 5°C, haemodynamic stability without the use of major doses of vasoactive medication, chest drain output < 1.5 mL/kg/h, presence of deglutition reflex, breathing minute volume > 80 mL/kg/min, breathing frequency > 10/min and < 20/min, oxygen saturation > 94% with FiO₂ ≤ 40% |

| Tenenbein 2008 | Postoperatively, participants' tracheas were extubated when they were haemodynamically stable, awake, and able to follow commands, with oxygen saturation ≥ 97%, FiO₂ ≤ 60%, and end‐tidal CO₂ ≤ 50 |

| Tenling 1999 | Participants were tracheally extubated when they were awake and haemodynamically stable and had carbon dioxide tension < 5.5 kPa while spontaneously breathing, oxygen tension > 10 kPa, FiO₂ < 0.45, and body temperature > 37.0°C |

| Usui 1990 | Extubation was considered once participants demonstrated the ability to breathe under continuous positive airway pressure |

| Yilmaz 2007 | Criteria for tracheal extubation were: stayed awake without stimulation, respiratory rate < 30 breaths/min, PaO₂ > 100 mmHg with FiO₂ ≤ 40% and PaCO₂ < 45 mmHg, stable haemodynamic and metabolic variables, and drainage < 100 mL/h |

| Zawar 2015 | Not reported |

cm H₂O: centimetre of water; CO₂: carbon dioxide; FiO₂: fraction of inspired oxygen; ICU: intensive care unit; kPa: kilopascal; PaCO₂: partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO₂: partial pressure of oxygen; pH: acidity or alkalinity of a solution on a logarithmic scale on which 7 is neutral; SaO₂: oxygen saturation; SpO₂: pulse oximetry; SvO₂: venous oxygen saturation.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (2018, Issue 11), Ovid MEDLINE (Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily and Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to 19 November 2018), Embase (1974 to 19 November 2018), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL, EBSCO host), and Web of Science (Science Citation Index (SCI)/Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI)) (19 November 2018). We applied no language or publication status restriction. The exact search strategies can be found in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We screened reference lists from retrieved randomized trials, reviews, meta‐analyses, and systematic reviews (Appendix 2), to identify additional trials.

We searched for conference abstracts from 2012 to 2017: American Society of Regional Anesthesia spring meetings, and European Society of Anaesthesiology, European Society of Regional Anaesthesia, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (December 2017) meetings.

We searched the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/trialsearch), as well as ClinicalTrials.gov (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov), to identify trials in progress (February 2019). For trials in progress, we did not retain trials past the date of completion and not updated within the last two years. We did this to avoid listing registered trials that are unlikely to ever be completed by study authors.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We independently screened the lists of all titles and abstracts identified by the search above. We retrieved and independently read articles of interest to determine their eligibility for inclusion. We resolved discrepancies by discussion. We examined for classification trials that might be included and that we found through sources other than electronic databases (included, excluded, or awaiting classification). We documented the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009). We listed all reasons for exclusion in a Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

We independently extracted data. For selected studies, we entered the following variables into our data extraction form: risk of bias as measured with the Cochrane tool; and outcomes and factors chosen a priori for assessment of heterogeneity (Higgins 2011a; Higgins 2011b). We extracted dichotomous data as the number of participants experiencing the event and the total number of participants in each treatment group. We extracted continuous data as means, standard deviations, and total numbers of participants. When data were not available in these formats, we extracted data as P values, numbers of participants, and direction of effect. We did not consider medians as equivalent to means, and we did not estimate standard deviations from quartiles or ranges. We entered first the site where the study was performed and the date of data collection (to facilitate exclusion of duplicate publications), then whether the study was included in the review or the reason for exclusion. After we reached agreement, one review author entered into the comprehensive meta‐analysis the data and moderators for heterogeneity exploration (Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis 2007). Also, after we reached agreement, we entered the risk of bias evaluation into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We resolved disagreements by discussion. We contacted all study authors for additional information. We entered data for analysis into Review Manager in the format required to include the maximal number of studies (events and total numbers of participants for each group; means, standard deviations, and numbers of participants included in each group; or generic inverse variance, if necessary). When possible, we entered the data into an intention‐to‐treat analysis.

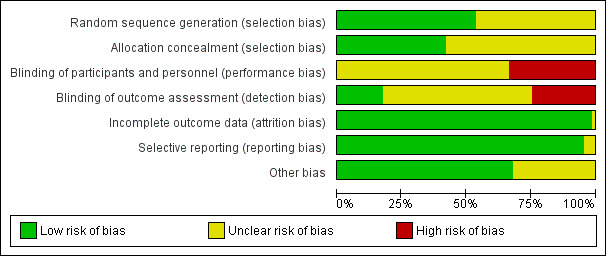

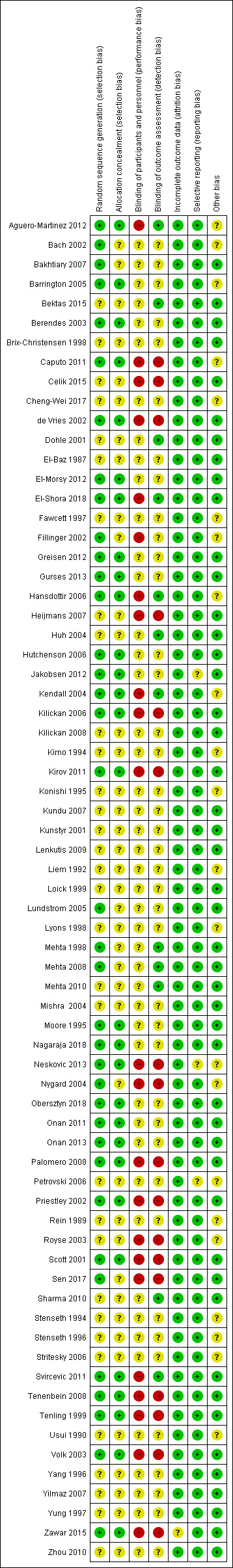

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We independently assessed the quality of included studies by using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias’ tool found in RevMan 5 (Higgins 2011a), to examine random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, or other risks of bias. We resolved disagreements by discussion. We assessed risk of bias on the basis of information presented in the reports or according to additional information received from study authors, while making no assumptions. We judged trials without a published protocol to be at low risk of bias for selective reporting when researchers provided in the results section the results for all measurements prespecified in the methods section.

Measures of treatment effect

We planned to report results as risk ratios (RRs) and to provide 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for dichotomous data (McColl 1998). Due to the large number of trials with zero cells, we analysed dichotomous data as risk differences (RDs). We reported results for continuous data (time of tracheal intubation) as mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs. For continuous data, because some data were extracted from different scales (days, hours, or minutes), and some data were available only as P values, we reported results as standardised mean differences (SMDs) with 95% CIs. For results reported as SMDs, we gave equivalence on a clinical scale. For SMDs, we considered 0.2 a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect, and 0.8 a large effect (Pace 2011). When an effect was found, we calculated using the odds ratio the number to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) (Cates 2016; Deeks 2002). When we were not able to demonstrate an effect, we calculated the number of participants required in a large trial to make sure that enough participants were included in the retained studies to justify a conclusion on the absence of effect (Brant 2017; Pogue 1998).

Unit of analysis issues

We included only parallel‐group trials. If a study contained more than two groups, we fused two groups (by using the appropriate formula for adding standard deviations when required) when we thought they were equivalent (taking our factors for heterogeneity exploration into account), or we separated them and split the control group in half if we thought they were different.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted all study authors for additional information. We made no imputation.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered clinical heterogeneity before pooling results, and we examined statistical heterogeneity before carrying out any meta‐analysis. We quantified statistical heterogeneity by using the I² statistic. We quantified the amount of heterogeneity as low (I² < 25%), moderate (I² = 25% to 74%), or high (I² = 75% or higher), depending on the value obtained for the I² statistic (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed publication bias by using a funnel plot, followed by Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill technique (Borenstein 2009; Duval 2000a; Duval 2000b). This technique not only assesses whether publication bias is likely, it also yields an estimate of effect size after correction for the possibility of publication bias when such bias is detected.

Data synthesis

We analysed data using Review Manager 5 and Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis Version 2.2.044 with fixed‐effect (I² < 25%) or random‐effects models (I² ≥ 25%) (Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis 2007; Review Manager 2014). For dichotomous data, we planned to provide results as RRs (values best understood by clinicians; McColl 1998), but due to the large number of trials with zero cells, we had to give results as RDs. For some continuous data, we had to enter data as P values, numbers of participants, and direction of effect using the RevMan 5 calculator (see Measures of treatment effect ). In such cases, MDs cannot be obtained. We then presented our results as SMDs and gave clinical equivalents calculated as follows: SMD multiplied by a typical SD on a clinical scale of one of the included trials (Higgins 2011b). For results in which the intervention produced an effect, we calculated the NNTB or the NNTH by using the odds ratio (http://www.nntonline.net/visualrx/) (Cates 2016). If an effect could not be demonstrated, we also calculated the number of participants required in a large trial to ensure that enough participants were included in the retained studies to justify a conclusion based on absence of effect (Brant 2017; Pogue 1998).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

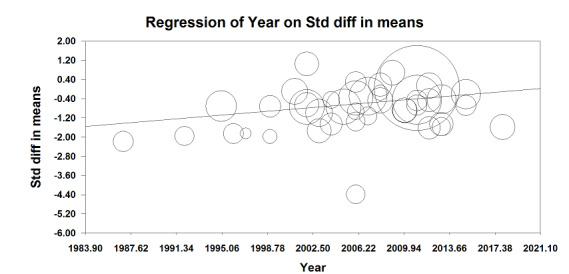

We divided all our outcomes as cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass and as off‐pump surgery (Kowalewski 2016). We looked at year of publication as a factor for heterogeneity so we could take into account changes in clinical practice and types of drugs used over time. We analysed subgroup differences using Review Manager (Chi²), and we considered a P value < 0.05 as significant for subgroup differences. We evaluated the effect of time by examining meta‐regressions between effect size and year of publication (pneumonia and duration of tracheal intubation), using Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis 2007.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis on risk of bias.

'Summary of findings’ table and GRADE

We judged the quality of the body of evidence according to the GRADE system and presented this assessment in ’Summary of findings’ tables for each comparison for all of our outcomes: mortality (0 to 30 days), myocardial infarction, respiratory complications (respiratory depression or pneumonia), atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter, neurological complications (cerebrovascular accident or epidural haematoma), duration of tracheal intubation, pain at six to eight hours, and haemodynamic support (GRADEpro GDT; Schünemann 2013). For risk of bias, we judged the quality of evidence as high when we derived most information from studies at low risk of bias, and we downgraded quality when we obtained most information from studies at high or unclear risk of bias (allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors). For inconsistency, we downgraded the quality of evidence when the I² statistic was 75% or higher without satisfactory explanation. We did not downgrade the quality of evidence for indirectness because outcomes were based on direct comparisons performed on the population of interest and were not surrogate markers. For imprecision, we downgraded the quality of evidence when the confidence interval around the effect size was large or overlapped an absence of effect and failed to exclude an important benefit or harm, or when the number of participants was less than the number required in a large trial. For publication bias, we downgraded the quality of evidence when correcting for the possibility of publication bias as assessed by Duval and Tweedie’s fill and trim analysis changed the conclusion. It is noteworthy that although factors influencing the quality of evidence are additive – such that the reduction or increase in each individual factor is added together with the other factors to reduce or increase the quality of evidence for an outcome – grading the quality of evidence involves judgements that are not exclusive. Therefore, GRADE is not a quantitative system for grading the quality of evidence. Each factor for downgrading or upgrading reflects not discrete categories but a continuum within each category and among categories (Schünemann 2013). When the body of evidence is intermediate with respect to a particular factor, the decision about whether a study falls above or below the threshold for upgrading or downgrading the quality depends on judgment. Reviewers may decide not to downgrade, even if they have some uncertainty around a specific category, when they already downgraded for another factor and further lowering the quality of evidence for this outcome would seem inappropriate (Schünemann 2013).

When the quality of the body of evidence is high, further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. When quality is moderate, further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. When quality is low, further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. When the quality is very low, any estimate of effect is very uncertain. Studies with low quality and very low quality of evidence are considered equivalent to observational studies.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

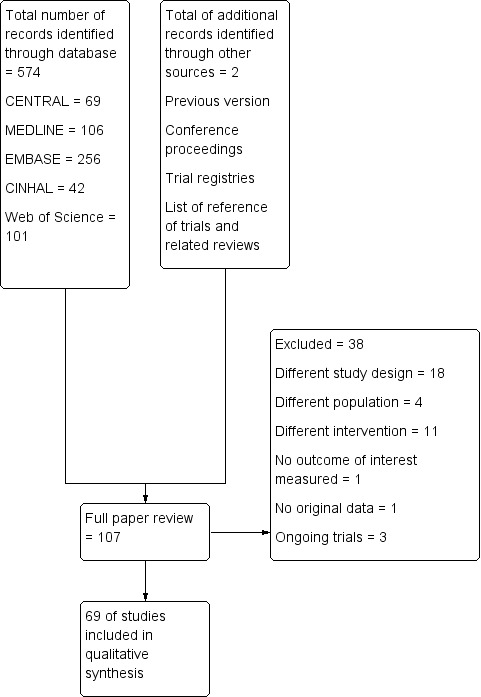

We identified 574 titles from the electronic search: 69 from CENTRAL, 106 from MEDLINE, 256 from EMBASE, 42 from CINHAL, and 101 from the Web of Science. We identified two additional trials from the other sources. We reviewed 107 trials for potential eligibility. Of these 107 trials, we excluded 38 for various reasons (see Figure 1Excluded studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of ongoing studies).

1.

Study flow diagram for update in 2019.

Included studies

We included 69 trials with 4860 participants: 2404 given epidural analgesia and 2456 given comparators. Trials were published between 1988 and 2018.

Source of funding

Of the 66 included studies:

five were funded by governmental resources;

eight by charity;

23 by departmental/institutional resources; and

two in part by the industry; and

31 trials did not specify their sources of funding.

Setting

The trials were conducted at university hospitals (n = 66) or in tertiary care centre hospitals (n = 3).

The trials were conducted in Australia (n = 3); Bangladesh (n = 1); Canada (n = 1); China (n = 2); Cuba (n = 1); Czech Republic (n = 2); Denmark (n = 5); Egypt (n = 2); Germany (n = 5); India (n = 9); Italy and UK (n = 1); Japan (n = 2); Korea (n = 1); Lithuania (n = 1); Macedonia (n = 1); Norway (n = 3); Poland (n = 1); Russia (n = 1); Serbia (n = 1); Spain (n = 1); Sweden (n = 3); Taiwan (n = 2); Turkey (n = 8); The Netherlands (n = 4); UK (n = 5); and USA (n = 3).

Participants

The mean (or median) age of participants varied between 43.5 years and 74.6 years (Characteristics of included studies).

The types of surgeries performed were:

coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) (n = 62);

mainly CABG (n = 1);

CABG or valve procedures (n = 4);

heart surgery for participants older than 15 years of age with congenital disease (n = 1); and

various cardiac procedures (n = 1).

The surgeries were performed:

with cardiopulmonary bypass (n = 50);

with off‐pump surgery (n = 15); and

on some participants with and some participants without cardiopulmonary bypass (n = 4).

Interventions

See Table 5.

Investigators administered epidural analgesia as a single injection block (n = 3); or as a continuous epidural analgesia with patient‐controlled analgesia (n = 7) or without patient‐controlled analgesia (n = 51); or as repeated injections through a catheter (n = 6).

The solution contained a local anaesthetic alone (n = 23); an opioid alone (n = 3); or a mixture of a local anaesthetic and an opioid (n = 41).

Two studies added clonidine and one added ketamine. A majority of studies added no other adjuvant to the solution (n = 64).

Local anaesthetics used were bupivacaine (n = 55); bupivacaine and ropivacaine (n = 1); ropivacaine (n = 7); levobupivacaine (n = 3); or mepivacaine (n = 1).

Opioids used were fentanyl (n = 24); morphine (n = 10); morphine or butorphanol (n = 1); sufentanil (n = 9); or hydromorphone (n = 1).

Mishra 2004 and Petrovski 2006 provided no details.

Comparators

See Table 5.

Researchers compared epidural analgesia versus systemic analgesia alone (n = 63), paravertebral blockade (n = 3), erector spinae plane block (n = 1), intrapleural analgesia (n = 1), or wound local anaesthetic infusion (n = 1).

Systemic analgesia consisted of morphine (intravenous (IV) patient‐controlled analgesia (PCA) (n = 7), IV infusion (n = 4), or on request (n = 9)); morphine or alfentanil (n = 2); fentanyl (IV PCA (n = 1) or infusion (n = 3)); nicomorphine (n = 1); piritramide (n = 5); tramadol (n = 4); meperidine (n = 3); meperidine and tramadol (n = 1); fentanyl and tramadol (n = 1); ketobemidone (n = 1); papaveretum (n = 1); diclofenac (n = 1); or various opioids (n = 4). The other trials did not provide details on systemic analgesia.

Study authors performed paravertebral blockade with bupivacaine infusion (n = 3).

Others performed erector spinae plane block with bupivacaine infusion (n = 1).

Some researchers provided intrapleural analgesia with repeated injections of bupivacaine (n = 1).

Others provided wound infusion with 0.15% bupivacaine (n = 1).

Excluded studies

We excluded 35 trials for the following reasons: different study design (n = 18), different study population (n = 4), different intervention (n = 11), or lack of original data in the publication (n = 1).

See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Studies awaiting classification

We have no studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing trials

We identified three ongoing trials (CTRI/2012/04/002608; CTRI/2018/05/013902; NCT03719248).

Risk of bias in included studies

2.