Abstract

Background

The threat of drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires great efforts to develop highly effective and safe bactericide.

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the antibacterial activity and mechanism of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) against multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa.

Methods

The antimicrobial effect of AgNPs on clinical isolates of resistant P. aeruginosa was assessed by minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC). In multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa, the alterations of morphology and structure were observed by the transmission electron microscopy (TEM); the differentially expressed proteins were analyzed by quantitative proteomics; the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was assayed by H2DCF-DA staining; the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and peroxidase (POD) was chemically measured and the apoptosis-like effect was determined by flow cytometry.

Results

Antimicrobial tests revealed that AgNPs had highly bactericidal effect on the drug-resistant or multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa with the MIC range of 1.406–5.625 µg/mL and the MBC range of 2.813–5.625 µg/mL. TEM showed that AgNPs could enter the multidrug-resistant bacteria and impair their morphology and structure. The proteomics quantified that, in the AgNP-treated bacteria, the levels of SOD, CAT, and POD, such as alkyl hydroperoxide reductase and organic hydroperoxide resistance protein, were obviously high, as well as the significant upregulation of low oxygen regulatory oxidases, including cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit P2, N2, and O2. Further results confirmed the excessive production of ROS. The antioxidants, reduced glutathione and ascorbic acid, partially antagonized the antibacterial action of AgNPs. The apoptosis-like rate of AgNP-treated bacteria was remarkably higher than that of the untreated bacteria (P<0.01).

Conclusion

This study proved that AgNPs could play antimicrobial roles on the multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. The main mechanism involves the disequilibrium of oxidation and antioxidation processes and the failure to eliminate the excessive ROS.

Keywords: silver nanoparticles, AgNPs, antibacterial activity, mechanism, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, multidrug-resistant bacterium

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most frequently isolated non-fermentative gram-negative bacillus and one of the most common opportunistic pathogens. It is easily found in patients with lung or burn wound infection and is a predominant colonized bacterium in some implanted medical devices, such as catheter. By taking advantage of its structural components, toxins, enzymes, and so on, P. aeruginosa incursion results in violent neutrophil response and tissue damage of the body.1,2 Moreover, formation of biofilm and quorum sensing system during the bacterial growth induces adaptive resistance,3,4 which gives rise to multidrug-resistant strains, especially resistant to carbapenems. Infection and spread of the resistant microbes are the reasons for chronic disease status and the “culprits” for high morbidity and mortality.5

Tacconelli et al6 evaluated the priority of 20 bacteria bearing 25 patterns of acquired resistance. Three levels of critical, high, and medium were classified according to ten criteria, such as fatality rate, drug-resistant tendency and distribution, medical care burden, preventive and therapeutic effect, and so on. The results showed that the critical-priority bacteria included carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa and carbapenem, and third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae.6 Clinically, carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa is cross-resistant to cephalosporins, quinolones, and aminoglycosides. Hence, development of new effective, safe, and broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents is urgently required to prevent and treat P. aeruginosa infection.

Nowadays, nanoparticles have achieved remarkable attention as novel antimicrobial products as they possess high surface area-to-volume ratio and unique physical and chemical properties.7–10 The different metals including silver, copper, titanium, zinc, and gold are used as antimicrobial materials. Hernándezsierra et al compared the anti-Streptococcus mutans activity of nano scale silver, gold, and zinc oxide and found that silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) worked best.11

Previous studies proved the strong antibacterial action of AgNPs on either gram-positive or gram-negative bacteria. Sondi and Salopek-Sondi first reported their observations of AgNPs against Escherichia coli and revealed that formation of “pits” in bacterial cell wall and accumulation of AgNPs in the cellular membrane led to an augmented permeability of the cell wall and ultimately the cell death.12 Shameli et al revealed that AgNPs were able to kill or curb Staphylococcus aureus or Salmonella typhimurium, and their antibacterial performance strongly relied on the dimension of the particles.13 To the best of our knowledge, only very few studies reported that AgNPs had antimicrobial activity on multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa.14 Moreover, the antimicrobial mechanisms of AgNPs on multidrug-resistant bacteria remain enigmatic. Currently, the most known mechanisms of AgNPs involve 1) AgNPs disrupt the integrity of the bacterial cell wall and membrane, promoting the permeability of the membrane and the leakage of the cell constituents, and eventually induce cell death;15 2) AgNPs interrupt the respiratory chain reaction by combining the sulfhydryl, resulting in lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage of DNA and proteins, and then the cell death;16,17 3) AgNPs bind to sulfur and phosphorous groups of the DNA, which leads to damage and aggregation of the DNA and disrupt its transcription and translation;18 4) AgNPs foster dephosphorylation of phosphotyrosines, and thereby interfere the process of cell signal transduction and killing the cells;15 5) when AgNPs are exposed to aerobic conditions, they could release Ag+ from the surface of the particles. The released Ag+ plays strong antimicrobial roles by interacting with the cell membrane and cell wall components of the bacteria, which is one of the crucial mechanisms of toxicity of AgNPs.19

This study aimed to investigate the antibacterial activity of AgNPs on clinically isolated multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa and to explore the potential mechanisms. Morphology and structure alternations of the bacteria, when exposed to AgNPs, were observed with TEM. Tandem Mass Tag (TMT)-labeled quantitative proteomic was conducted to disclose the impact of AgNPs on the protein expression of the bacteria. Our data revealed that AgNPs could effectively kill the multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa in vitro. The main mechanisms may involve disequilibrium of oxidation and antioxidation processes and failure to eliminate the overproduced reactive oxygen species in the bacteria, which cause lipid peroxidation and damage of the DNA and ribosome, and accordingly, the synthesis of the large molecules is reduced and cell death occurs.

Materials and methods

Preparations for AgNPs

The ready-to-use AgNP stock solution (containing 1,000 µg/mL nano silver) was provided by Hunan Anson Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Changsha, China). Briefly, 0.78 g/L silver nitrate and 0.5 g/L branched cyclodextrin solution were separately prepared. About 10 mL of AgNO3 was slowly dropped into 40 mL of branched cyclodextrin, and the mixed solution was water bathed at 90°C; keep stirring the mixture until the Ag+ was completely reduced to Ag0. The completion of the reaction was confirmed by Na2S addition. To be exact, if black precipitates are formed after adding 0.1 g/L Na2S into the above Ag+/Ag0-contained solution, it indicated incomplete transformation of Ag+ to Ag0; in contrast, if no black precipitates appeared, it meant the reaction is complete and the obtained AgNPs were qualified. The NPs synthesized by this method could form stable complex with branched cyclodextrin to prevent silver particles from agglomeration. After the specific absorption spectrum of AgNPs was measured by UV-visible spectrophotometry, the morphology of the particles was observed by TEM and their size was measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS). For TEM detection, briefly, the aliquots of the AgNP solution were dropped onto a carbon film held by a copper mesh and air-dried at room temperature before they were characterized by conventional bright-field TEM images. For particle size measurement, 3–5 mL of 10 µg/mL nano silver dilution was tested by a laser particle size analyzer HPPS 5001 (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK).

Isolation of P. aeruginosa and the antimicrobial susceptibility test

The bacteria of P. aeruginosa were isolated from the clinically infectious specimens and identified using the VITEK2 computer automatic bacteria identification system (Bio Merière, Lyon, France) and rechecked by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, which were part of our routine laboratory procedure. A total of 21 strains of P. aeruginosa were obtained and their antimicrobial susceptibility was tested by Kirby–Bauer method. The bacterial concentration was 1×108 CFU/mL, and the anti-microbials included gentamycin, levofloxacin, piperacillin/tazobactam, cefepime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, and meropenem. P. aeruginosa strain of ATCC 27853 was used as the quality control. According to 2017 guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, the bacteria were divided into three groups of sensitive, drug resistant, and multidrug resistant. Those resistant to three antimicrobials or more were classified as multidrug-resistant strain.

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) measurements of AgNPs against P. aeruginosa

The MIC of AgNPs against 21 clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa was tested with agar double dilution method; the MBC was determined by broth double dilution. The concentration of the bacteria used in this measurement was about 1×104 CFU/mL, and the concentration gradients of AgNPs were from 45, 22.5, 11.25, 5.625, 2.813, 1.406, 0.703, 0.352, 0.176 to 0.088 µg/mL. Furthermore, the MIC values of AgNPs against multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa at different concentrations of 103, 105, and 107 CFU/mL were measured and compared. In addition, the antibacterial effects of AgNPs under the concentration of 1 MIC or 2 MIC at different time intervals were measured by counting the living bacteria on plates and the time–bactericidal curves were plotted.

AgNP treatment and preparations for TEM observation

In order to observe the impact of AgNPs on the morphology and structure of P. aeruginosa, five isolates of multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa were adopted, and each was proliferated to 1×108 CFU/mL. After being exposed to 11.25 µg/mL AgNPs for 2 hours, the culture was precipitated by centrifugation and washed once with PBS and then centrifugated; the precipitates were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde overnight, and rinsed three times with 0.1 M phosphoric acid; the bacteria were dehydrated, paraffin embedded, and sliced, then double stained with 3% uranium acetate and lead nitrate before being observed by Hitachi H7700 TEM. The bacteria without AgNPs treatment were performed as controls.

TMT-labeled quantitative proteomic analysis

Bacteria of 1×108 CFU/mL P. aeruginosa were co-cultured with 11.25 µg/mL AgNPs in Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid medium at 37°C for 1 hour. Following centrifugation, the precipitates were washed with PBS and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. After thawing, the samples were lysed with four times the volume of the lysis buffer, containing 8 M urea, 1% protease inhibitor, and 2 mM EDTA, and then underwent ultrasonication and centrifugation at 16,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 minutes. The sediment was further dissolved in 8 M urea and the protein concentration of the solution was determined with bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit. For TMT proteomic analysis, the protein solution was first reduced with dithiothreitol for 30 minutes at 56°C, alkylated with iodoacetamide for 15 minutes at room temperature in the darkness and then diluted with 100 M triethyl ammonium bicarbonate (TEAB). After that, trypsin was added into the dilution at a mass ratio of 1:50 (trypsin:protein) for overnight digestion at 37°C. Further digestion was conducted by adding trypsin into the solution at a mass ratio of 1:100 for another 4 hours. Using a Strata X C18 SPE column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA), the tryptic peptides were desalted, vacuum-dried, reconstituted in 0.5 M TEAB and further labeled by TMT in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The labeled tryptic peptides were fractionated by high pH reverse-phase HPLC using Agi-lent 300 Extend C18 column (5 µm particles, 4.6 mm ID, 250 mm length). Briefly, the peptides were first separated with a gradient of 8%–32% acetonitrile (pH 9.0) into 60 fractions. Then, the peptides were combined into 18 fractions and dried by vacuum centrifuging. The peptides in these fractions were further separated using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). MS/MS data containing all the peptides information were identified and analyzed by software Maxquant (version 1.5.2.8). Using the UniPort-GOA database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/GOA/), InterProScan (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/), and Gene Ontology (GO) annotation (http://geneonfelogy.org/), all the identified proteins were classified into three categories (cell component, molecular function, and biological process) by GO analysis. Only proteins with fold change >1.30 or <0.77 and a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test P-value <0.05 in three replicates were considered as significantly upregulated or downregulated in protein abundance, compared to the AgNPs-untreated control.

Detection of ROS and superoxide anions

Dynamic changes of the ROS in the bacteria, with AgNP-processed time or concentration, were assessed, and so were the superoxide anions (O2−). To be exact, at different time points of 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, and 2 hours post-AgNP treatment on 1×108 CFU/mL P. aeruginosa, or when 1×108 CFU/mL P. aeruginosa was subjected to AgNPs for 1 hour with the gradient concentrations of 0, 5.625, 11.25, 22.5, and 45 µg/mL, the bacteria were collected for further analysis.

ROS was measured by 2′,7′-dichloro fluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA). In the beginning, 10 mM H2DCF-DA stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide was diluted to 1 mM working solution with LB medium. The collected bacteria were washed with PBS and suspended in 1.8 mL of PBS; then, the samples were incubated with 200 µL of working solution at 37°C for 30 minutes in darkness. After that, the cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended in PBS, and this bacterial suspension was dropped on a slide and naturally dried in darkness at room temperature before fluorescence microscope detection. Meanwhile, the cultured bacteria were lysed by alkaline lysis buffer and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 minutes. Subsequently, 1 mL of supernatant of the lysate was prepared for fluorescence spectrophotometry detection at the wavelength of 520 nm.

The O2− contents were tested by hydroxylamine oxidation assay kit (Suzhou Kechromium Biotechnology Inc., Suzhou, China). The testing principle is that the O2− reacts with hydroxylamine hydrochloride to form NO2−, and under the action of p-aminobenzenesulfonic acid and α-naphthylamine, NO2− produces a red azo compound with a characteristic absorption peak at a wavelength of 530 nm and the O2− content of the sample can be calculated from the A 530 value.

Detection of the activity of the relevant REDOX enzymes

The activities of catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were measured at different time intervals of 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, and 4 hours post-AgNP treatment on 1×108 CFU/mL P. aeruginosa, or when 1×108 CFU/mL P. aeruginosa suffered AgNP treatment for 1 hour with the gradient concentrations of 0, 5.625, 11.25, 22.5, and 45 µg/mL. The bacteria were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes and then washed and suspended with PBS. Following ultrasonic disruption in ice bath for 5 minutes, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 minutes, and the protein levels in the supernatants were assayed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250; the activity of SOD was measured by water soluble tetrazole salt assay, POD by guaiacol method, and CAT by ammonium molybdate colorimetry. The kits were purchased from Najing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China).

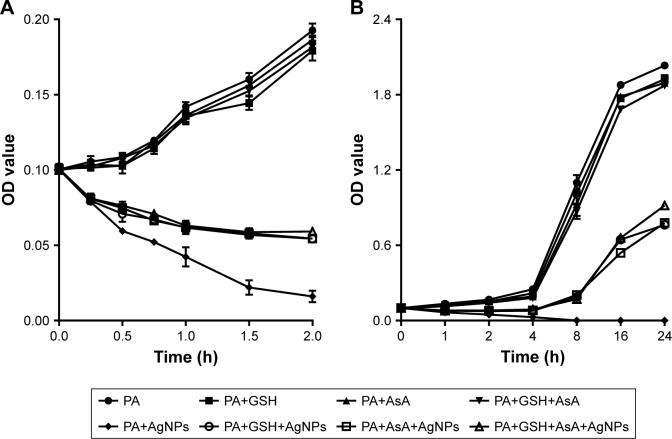

Detection of the effect of antioxidants on the antibacterial ability of AgNPs

Glutathione (GSH) and ascorbic acid (AsA) are the common antioxidants that can neutralize ROS in the cell. To explore their action on the growth of P. aeruginosa, GSH or AsA was added alone or together to the AgNPs-treated bacteria and the 625 nm OD values of the bacteria was determined. To be exact, 1×108 CFU/mL P. aeruginosa treated with 11.25 µg/mL AgNPs was incubated in LB medium at 37°C, with the addition of 1.5 mmol/mL GSH or AsA or both. The OD values of the bacteria were measured at each time points of 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, and 2 hours, or at time points of 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 24 hours posttreatment. The bacteria in the absence of AgNPs or antioxidant or both were cultured as controls.

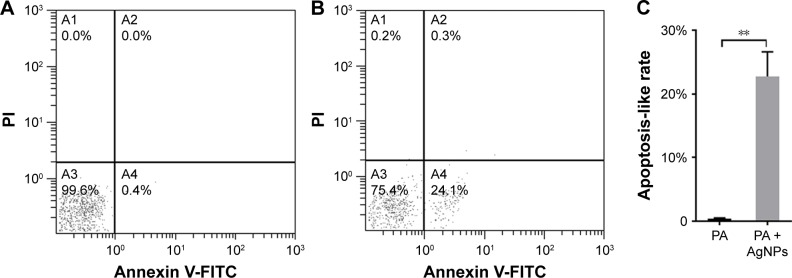

Detection of the bacterial apoptosis-like effect

The apoptosis-like effect of AgNP-treated multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa was detected by annexin V and propidium iodide double staining under the guidance of the manufacturer’s instruction (US Everbright Inc., Suzhou, China). Briefly, 1×108 CFU/mL P. aeruginosa was exposed to 11.25 µg/mL AgNPs in LB medium at 37°C for 2 hours; then the bacteria were collected and washed once with pre-cooled PBS. After resuspended in 100 µL of annexin V-binding buffer and icily incubated with 5 µL of FITC-conjugated annexin V and 2 µL of propidium iodide for 15 minutes away from light, the samples were diluted with 400 µL of PBS and loaded to a FC 500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter Inc., CA, USA) within 1 hour. The bacteria without AgNP addition were taken for negative controls.

Results

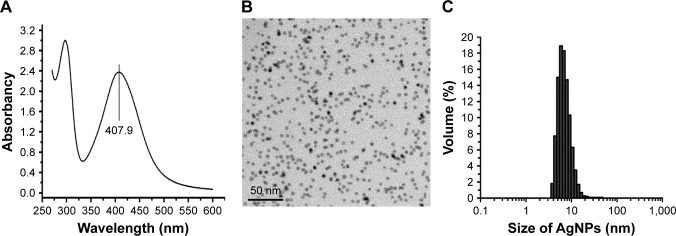

Characteristics of the AgNP solution

AgNP solution was tested by a UV-visible spectrophotometer ranging from 250 to 600 nm. The results showed a typical AgNP absorption peak at 407.9 nm (Figure 1A). Under TEM, the AgNP particles in the solution presented near-spherical shape, uniform size, and perfect dispersion (Figure 1B). DLS measurement demonstrated that the nanoparticles were normally distributed in diameter between 5 and 20 nm; most of them were of 5–10 nm in diameter (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Physical and chemical properties of AgNP solution.

Notes: (A) The ultraviolet-visible absorption spectrum of AgNPs, with a peak at 407.9 nm. (B) The morphology and size of AgNPs under TEM observation. (C) The particle size distribution of AgNPs measured by DLS.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; DLS, dynamic light scattering; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Screening for the phenotype of resistant P. aeruginosa

A total of 21 strains of P. aeruginosa were isolated and identified from clinically infectious specimens. Drug susceptibility test determined that 12 (57.14%) of them were drug-resistant and nine (42.86%) multidrug-resistant; none of them were drug-sensitive. Notably, meropenem resistance was found in each of the strains.

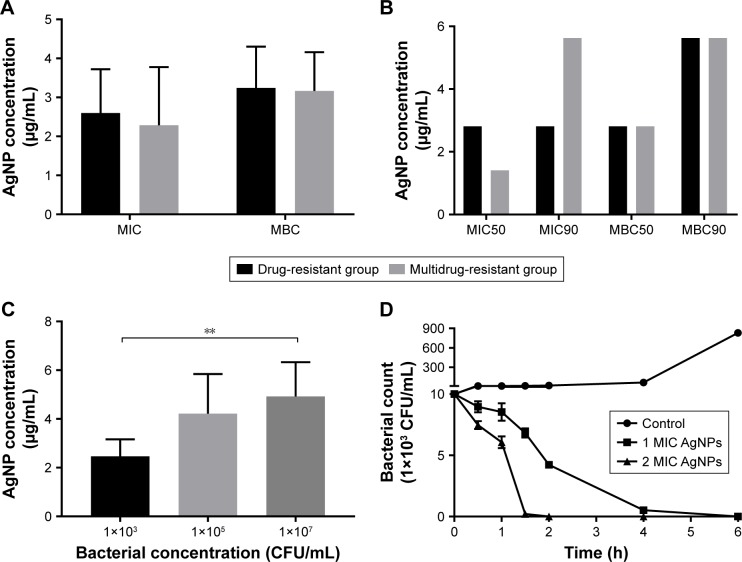

Antibacterial effect of AgNPs on resistant P. aeruginosa

Agar dilution test revealed that the mean MIC in the multidrug-resistant group was 2.285±1.492 µg/mL and the mean MBC 3.165±0.994 µg/mL; in comparison, the mean MIC and MBC in the drug-resistant group were 2.596±1.126 µg/mL and 3.246±1.056 µg/mL, respectively. The values of MIC or MBC were not significantly different between the two groups (P.0.05, Figure 2A; Table S1). The values of MIC 50/90 and MBC 50/90 between the two groups were also compared in Figure 2B. The results showed that AgNPs had high bactericidal effect on the drug-resistant or multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa with the MIC range of 1.406–5.625 µg/mL and the MBC range of 2.813–5.625 µg/mL.

Figure 2.

Antibacterial effect of AgNPs against the resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Notes: (A) The mean values of MIC and MBC of AgNPs against P. aeruginosa. (B) The values of MIC50 and MBC90 of AgNPs against P. aeruginosa. (C) The effect of different concentrations of P. aeruginosa on MIC of AgNPs. (D) The time–bactericidal curve of AgNPs against P. aeruginosa. **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; MBC, minimal bactericidal concentration; MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration.

The MIC values of AgNPs against multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa at different density of 103, 105, and 107 CFU/mL were measured to figure out whether the concentration difference of the bacteria exerts influence on the activities of AgNPs. As shown in Figure 2C, the MIC of AgNPs significantly stepped up with the increase of the bacterial concentration (P<0.05). The results indicated that the bacterial concentration could affect the MIC of AgNPs; the higher the concentration was, the bigger the MIC of AgNPs.

Further plate counting confirmed that when the concentration of AgNPs was at 1 MIC, the count of multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa fell at 0.5 hour post-culture; this downtrend continued, as Figure 2D depicts that at 2 hours post-culture, the number of bacteria reduced further, and at 4 hours post-culture, the majority of the bacteria was destroyed; few bacteria survived at 6 hours post-culture. When the concentration of AgNPs was at 2 MIC, the number of bacteria decreased more rapidly compared to that at 1 MIC; almost all the bacteria were killed at 2 hours post-culture. It proved that AgNPs could effectively kill multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa, and the effectiveness was positively related to the concentration of AgNPs.

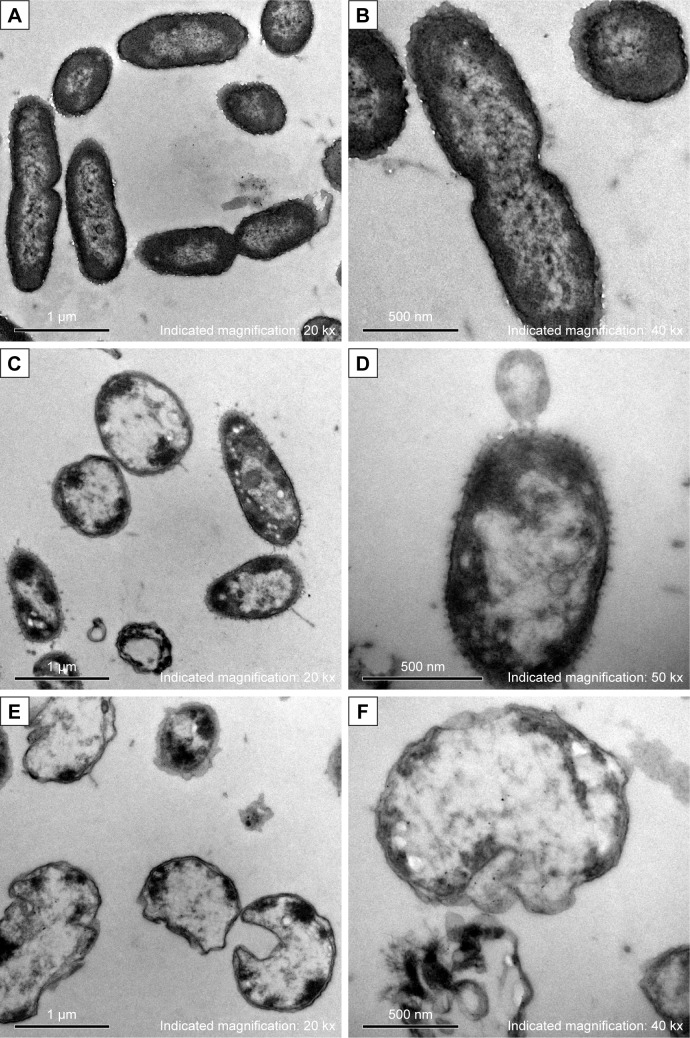

AgNPs altered morphology and structure of multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa

After treated with AgNPs for 2 hours, the bacteria of each multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa were collected for morphology and structure examination by TEM. In contrast to the untreated bacteria, which showed intact morphology of bacilliform with evenly distributed nucleoplasm and visible flagellum (Figure 3A and B), alterations in the AgNP-treated groups (covering five isolates) were similar, which included that the cell wall became thin or even disappeared; the cell membrane was crumpled and the cell integrity was violated, along with AgNPs, vacuoles, and nucleoplasm agglutination inside the cell (Figure 3C and D). Some bacteria became swollen or atrophy, combined with cell membrane deformation or rupture and release of the cell contents (Figure 3E and F).

Figure 3.

Morphology and structure alterations of AgNP-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa observed by TEM.

Notes: (A, B) The untreated P. aeruginosa. (C, D) The changes of P. aeruginosa post-AgNP treatment at the early stage. (E, F) The changes of P. aeruginosa post-AgNP treatment at the late stage.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

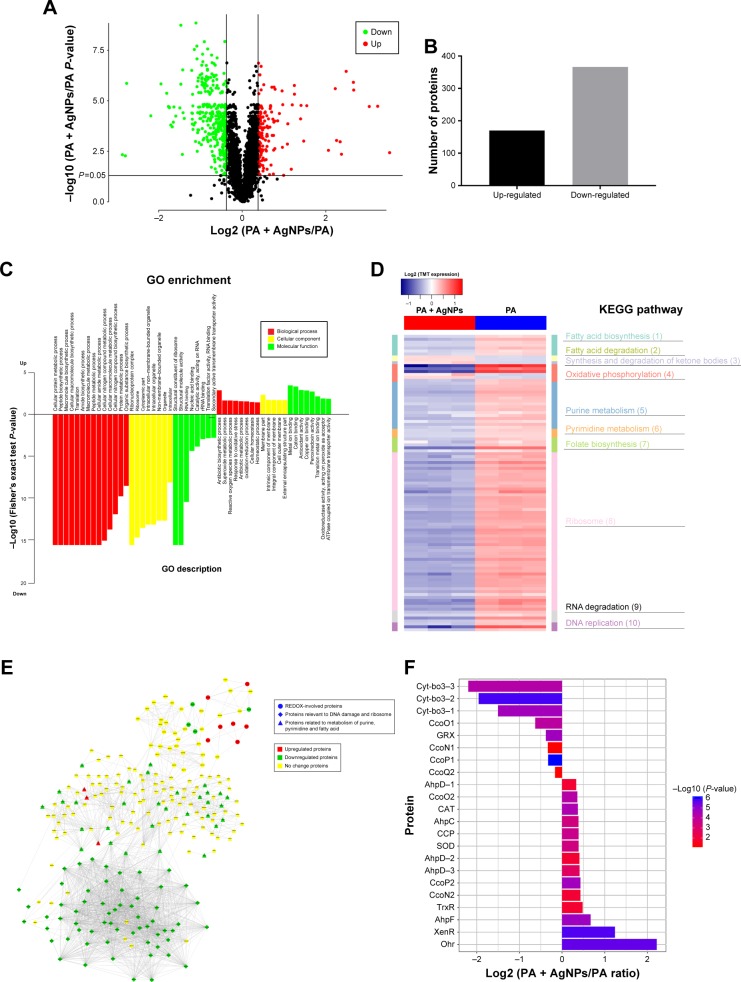

AgNPs destroyed the REDOX homeostasis of multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa

Based on TMT-labeled quantitative proteomic platform, a total of 3,247 proteins were identified; among them, 3,011 were quantified in multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa. In comparison with the control group, 170 proteins were upregulated and 366 proteins were downregulated in the AgNP-treated bacteria (P<0.05, Figure 4A and B). GO enrichment analysis showed that the proteins involved in the processes of reactive oxygen metabolism, oxidative stress, and REDOX were significantly highly expressed in the experimental group; while the expression of the proteins with reference to synthesis, metabolic processes, amino compound, and the macromolecular substances was low (Figure 4C). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis concluded that in the AgNP-treated group, proteins participating in oxidative phosphorylation, purine and pyrimidine metabolism, ribosome and RNA degradation, DNA replication, fatty acid degradation, and synthesis and degradation of ketone bodies were significantly enriched (Figure 4D). Protein interaction analysis described that the majority of oxidative and antioxidant proteins were increased in the treatment group, but the DNA and RNA damage-related proteins and ribosomal proteins were decreased (Figure 4E). Further analysis of oxidative stress-related proteins showed that the expression level of SOD, CAT, alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpD, AhpC, and AhpF), cytochrome c551 peroxidase, and organic hydroperoxide resistance protein (Ohr) in AgNP-addressed P. aeruginosa were distinctively higher than those in the control group; cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit P2 (CcoP2), N2 (CcoN2), and O2 (CcoO2) were significantly upregulated in the experimental group; cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit P1 (CcoP1), O1 (CcoO1), and cytochrome bo3 ubiquinol oxidase (Cyt-bo3) were down-regulated in the AgNP-treated P. aeruginosa (Figure 4F; Table S2). The proteomic results imply that AgNPs acting on P. aeruginosa may impel developing oxidative stress reaction in the bacteria and lessen the local oxygen pressure, which inversely upregulate the corresponding reductases and hypoxia regulatory oxidases and downregulate the constitutive and hyperoxic regulatory oxidases. Consequently, AgNPs may impact on the bactericidal performance by affecting the REDOX process, DNA replication, RNA transcription, biosynthesis, and metabolism of the ribosomes, purines, pyrimidines, and fatty acids of the bacteria (Table S3).

Figure 4.

Expression and function analysis of the proteins identified by TMT-labeled quantitative proteomic in AgNP-treated multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Notes: (A) The volcano map of differentially expressed proteins. The abscissa denotes the ratios of differential expression proteins in the AgNP-treated P. aeruginosa vs those in the untreated bacteria; the ordinate represents the P-values between the two groups. (B) The number of differentially expressed proteins identified by TMT-labeled quantitative proteomic. (C) GO enrichment cluster analysis of the differential proteins. The red color represents the proteins relevant to biological processes; the yellow, cellular localization and the green, molecular function. Those above the horizontal axis are the upregulated proteins and those below the axis are the downregulated proteins. (D) KEGG pathway clustering heat map of the differential proteins. The deeper the blue color, the more significant the enrichment is. (E) The interactive network of three groups of proteins and their differential expression in the AgNP-treated P. aeruginosa vs those in the untreated bacteria. (F) The comparative analysis of oxidative stress-related proteins between pre- and post-AgNP treatment.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; PA, P. aeruginosa; TMT, Tandem Mass Tag.

Excessive ROS production in AgNP-treated multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa

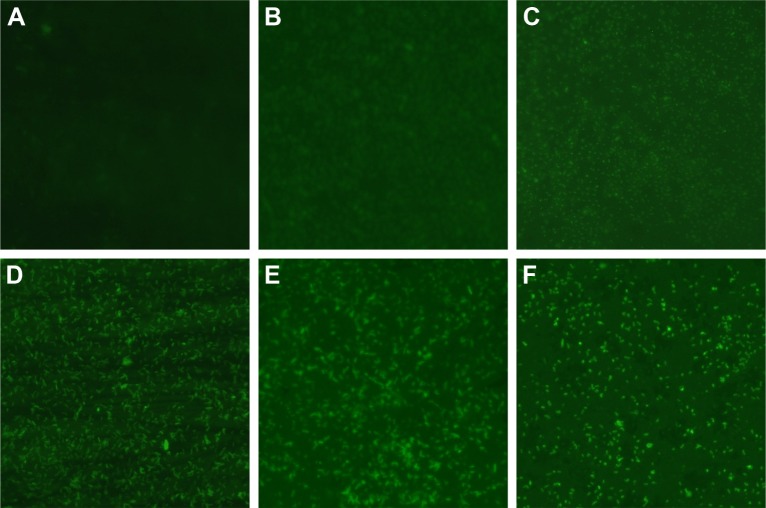

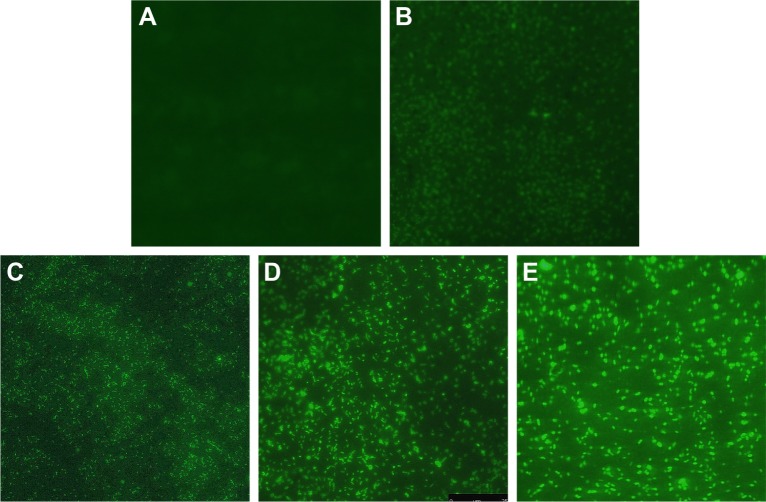

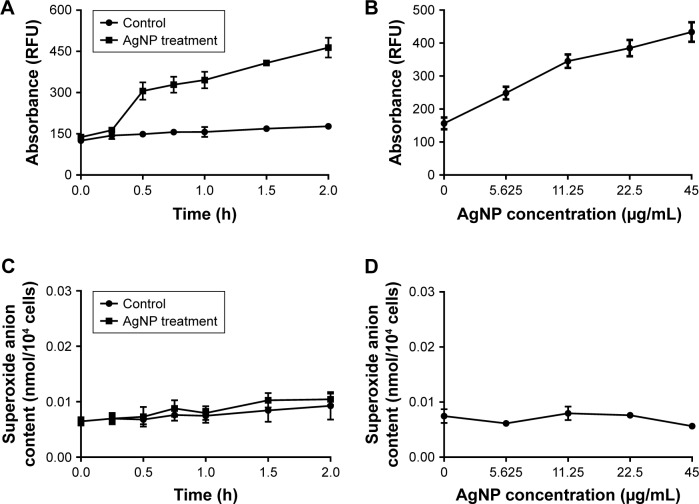

The H2DCF-DA staining and fluorescence microscopy revealed that compared to the weak fluorescence of untreated P. aeruginosa, the fluorescence intensity of the AgNP-treated bacteria accumulated with the extension of AgNPs acting time within 2 hours (Figure 5). Moreover, when exposed to a series of AgNP solution with different concentrations for 1 hour, the bacteria showed ascent fluorescence when the AgNPs were multiplied (Figure 6). The relative fluorescence intensity of AgNP-treated bacteria detected by fluorescence spectrophotometer was much higher than that of the control group within 2 hours (Figure 7A). When exposed to different concentrations of AgNPs within 1 hour, the fluorescence of the bacteria was gradually elevated with the increase of AgNPs (Figure 7B). Thence we infer that AgNPs induce excessive ROS production in multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. The ROS production is likely to be generated in the early stage of the interaction between AgNPs and the bacteria. However, the contents of O2− in both AgNP-treated and -untreated bacteria were very low, and no statistically significant difference was found between them (Figure 7C and D), which suggests that AgNPs may not help produce O2− in multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa.

Figure 5.

Changes of ROS production in AgNP-treated multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa at different time intervals under fluorescence microscopy with ×400 magnification.

Notes: (A) The untreated P. aeruginosa without observable fluorescence. (B–F) Fluorescence observation of the bacteria treated with AgNPs at different points of 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, and 2 hours, respectively, indicating that AgNPs induce ROS production in a time-dependent manner.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Figure 6.

Changes of ROS production in multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa exposed to different concentrations of AgNPs under fluorescence microscopy with ×400 magnification.

Notes: (A) The untreated P. aeruginosa without observable fluorescence. (B–E) Fluorescence observation of the bacteria exposed to 5.625, 11.25, 22.5, and 45 µg/mL AgNPs, respectively.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Figure 7.

Changes of ROS and O2− production in AgNP-treated multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Notes: (A) RFU–time curve of ROS production of the bacteria at different AgNP-treated time points of 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, and 2 hours. (B) RFU–concentration curve of ROS production of the bacteria, exposed to different AgNPs concentrations of 0, 5.625, 11.25, 22.5, and 45 µg/mL. (C) The O2− content–time curve of the bacteria at different AgNP-treated time points of 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, and 2 hours. (D) The O2− content–concentration curve of the bacteria, exposed to different AgNP concentrations of 0, 5.625, 11.25, 22.5, and 45 µg/mL, respectively.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; RFU, relative fluorescence unit; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

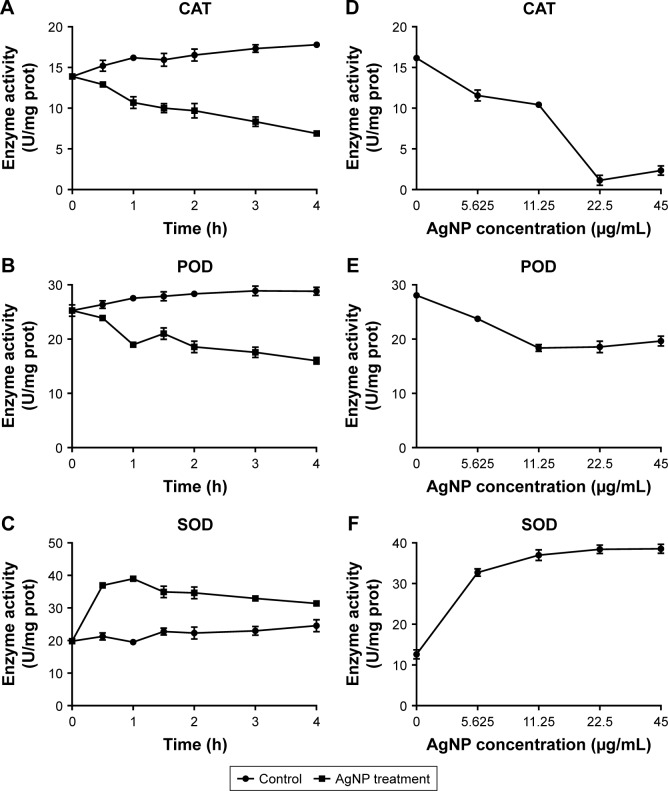

Alteration of the activity of the REDOX relevant enzymes in AgNP-treated multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa

Despite AgNPs prospered the ROS generation in the multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa, the contents of some REDOX relevant enzymes were increased because of the oxidative stress reaction in the bacteria. Therefore, the activity of these enzymes, including CAT, POD, and SOD, needs to be further explored. We found that the activity of CAT or POD was gradually lowered as the time of AgNP administration was prolonged. Compared to the control, the significantly low activity of CAT began at 0.5 hour post-treatment (P<0.05, Figure 8A); while for POD, it began at 1 hour posttreatment (P<0.05, Figure 8B). Moreover, the activity of SOD was boomed during the first 0.5 hour and maintained high level by 1 hour; then it reduced but still higher than that of the control group (P<0.05, Figure 8C). In addition, the activities of CAT, POD, and SOD were detected at the time of 1 hour after AgNPs were added to the bacteria with different concentration. As shown in Figure 8D–F, the activity of CAT was plummeted with the increase of AgNP concentration; while the activity of POD was first decreased at the range of 5.625–11.25 µg/mL AgNPs and thereafter remained stable in much higher level of AgNPs solution; the activity of SOD was enhanced with the addition of AgNPs but that was not closely correlated to the concentration of the AgNPs. In conclusion, AgNPs even though may constrain the action of CAT and POD, it is not the case when working on SOD.

Figure 8.

Alteration of the activities of CAT, POD, and SOD in AgNP-treated multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Notes: (A–C) The activity–time curves of CAT, POD, and SOD, respectively, when P. aeruginosa was exposed to AgNP treatment at different time points of 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, and 4 hours, respectively. (D–F) The activity–concentration curves of CAT, POD, and SOD, respectively, when the bacteria were addressed by a series of AgNP concentrations of 0, 5.625, 11.25, 22.5, and 45 µg/mL, respectively.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; CAT, catalase; POD, peroxidase; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

Partial antagonization of antioxidants in AgNP-treated multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa

Determination of the activities of antioxidants on the antimicrobial effect of AgNPs revealed that, in the group without the addition of antioxidant, the number of P. aeruginosa was distinctly reduced at 2 hours post-AgNP treatment and most of the bacteria were dead at 4 hours; in contrast, in the group added with antioxidant, the number of bacteria had no significant change at 2 hours post-AgNP treatment and obvious proliferation of bacteria was observed from 4 hours (P<0.01). Notably, there was no significant change of the bacterial growth when GSH or AsA was added alone or together (Figure 9A and B). It is reasonable to deduce that the antioxidants can remove the ROS induced by AgNPs and thereby partially antagonize the antibacterial activity of AgNPs, but GSH and AsA may not act in a synergistic way.

Figure 9.

The effect of addition of antioxidant on the growth of AgNP-treated multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Notes: (A) Bacterial growth–time curve in different groups treated by AgNPs together with GSH, AsA, or GSH+AsA within 2 hours, compared to the groups without AgNP treatment or antioxidant addition. (B) Bacterial growth–time curve in different groups treated with AgNPs together with GSH, AsA, or GSH+AsA within 24 hours, compared to the groups without AgNP treatment or antioxidant addition.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; AsA, ascorbic acid; GSH, glutathione; OD, optical density; PA, P. aeruginosa.

Apoptosis-like effect of AgNP-treated multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa

Flow cytometry with Annexin V and propidium iodide double staining assay identified that the average apoptosis-like rate of bacteria in the AgNP-treated group was 22.73%, predominantly higher than that of the untreated bacteria, which was 0.4% (P<0.01, Figure 10), and early apoptosis prevailed in the process. The results give evidences to support the inference that the excessive ROS induced by AgNPs may promote the apoptosis-like effect of P. aeruginosa.

Figure 10.

Apoptosis-like effect of AgNP-treated multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Notes: (A) The apoptosis-like rate of the untreated P. aeruginosa measured by flow cytometry. (B) The apoptosis-like rate of the AgNP-treated bacteria measured by flow cytometry. (C) The comparative analysis of the average apoptosis-like rate of five biological replicates between the AgNP-treated and -untreated groups. **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; PA, P. aeruginosa; PI, propidium iodide.

Discussion

At present, prevention and therapy of P. aeruginosa infection become increasingly challenging, owing to its intrinsic and acquired drug-resistant properties.20 Carbapenems are currently the most important therapeutic option to deal with multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa.21 In this study, we isolated and tested 21 clinical P. aeruginosa strains. Among them, 12 were drug-resistant and nine were multidrug-resistant; most concerning of all, meropenem resistance was found in each of the strains. The threat posed by resistant P. aeruginosa requires great efforts to develop highly effective and safe bactericidal products with a wide spectrum of activity.

AgNPs can be prepared by chemical synthesis, physical methods, or biological techniques.22,23 Here we made AgNP solution by chemical methods, where a characteristic absorption peak was observed at 407.9 nm. Further detection revealed these particles were nearly spherical in shape and evenly distributed in size with an average dimension of 5–10 nm.

The antibacterial effects of AgNP correlate with the particle dimension. The bigger the diameter is, the weaker the impact. Choi et al24 found that it was difficult for the AgNPs of >20 nm to move into the bacteria; particles of 1–15 nm were able to attach at the surface of the bacteria, while at the size of around 5 nm, AgNPs could step into the bacteria and their antibacterial effect was significantly effective than those of 10–20 nm.24 To investigate the bactericidal performance of AgNPs against resistant P. aeruginosa, we adopted 5–10 nm silver spheres. Our results showed that the MIC and MBC of AgNPs against drug-resistant and multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa were between 1.406–5.625 µg/mL and 2.813–5.625 µg/mL, respectively, proving that AgNPs had strong antibacterial impact on the resistant P. aeruginosa at low concentration. Further antimicrobial tests revealed that AgNPs could rapidly destroy P. aeruginosa in a pattern based on dose and time. Orlov et al reported that AgNPs acted positively against E. coli in a concentration- and time-dependent manner at a range of low concentrations.25 Nonetheless, our results showed that the bactericidal effectiveness of AgNPs between drug-resistant and multidrug-resistant was of insignificance, indicating that the antibacterial mechanism of AgNPs may be different from that of antibiotics.

By using TEM, Shrivastava et al observed the interactive process of AgNPs and E. coli: In the beginning, AgNPs anchored on the cell wall, where the potential negative charge groups existed, and then drilled holes in the wall and went into the cytoplasm, which finally resulted in the cell membrane perforation and cell lysis.15 Another group reported that no obvious destruction was viewed in the membrane of AgNPs-treated E. coli, although electron dense granules were found in the cytoplasm.25 We found that after co-cultured with AgNPs, P. aeruginosa showed thinning cell wall and shrinking cell membrane, along with AgNPs, vacuoles, and agglutinative nucleoplasm inside the cell, while some bacteria became swollen or atrophic, which often accompanied fractured membrane and tremendous reduction of the cell contents. We conclude that AgNPs can be initially absorbed on the surface of the cell and then undermine the cell membrane, after that, the particles may be transported into the cytoplasm and imposed on a variety of macromolecules, either directly or indirectly, followed by DNA aggregation, protein degradation, or intracellular substance release and eventually, cell death.

Proteomic technology has been universally applied in the study of protein expression, post-translational modification, and their interaction, which help us to comprehensively understand the disease pathogenesis or cell metabolism at the protein level.26 Previous studies proved that AgNPs could interrupt the respiratory chain reaction in bacteria by combining the sulfhydryl units of dehydrogenase and inhibiting its activity.16 We speculate that AgNPs may curb dehydrogenase activity in P. aeruginosa and disturb the reaction of aerobic respiration and oxidative phosphorylation, resulting in accumulation of ROS and initiation of oxidative stress response in the bacteria. Actually, based on TMT-labeled quantitative proteomic analysis, our results implied that, after AgNP treatment, the oxidative stress reaction in the bacteria was strengthened with obvious high expression of SOD, CAT, and POD (such as AhpD, AhpC, AhpF, and Ohr). Our experimental results also confirmed the excessive production of ROS. In a biological context, ROS are formed as natural byproducts of the oxygen metabolism. As ROS production consumed a large amount of oxygen, oxygen pressure in the local environment in the bacteria was dropped. This drop triggered the promotion of low oxygen pressure-regulated oxidases,27 such as CcoP2, CcoN2, and CcoO2, and demotion of high oxygen pressure-regulated oxidases, such as CcoP1, CcoO1, and Cyt-bo3. Excessive ROS caused lipid peroxidation, membrane permeability augmentation, and oxidation damage of DNA, RNA, and proteins. By doing this, the oxidative phosphorylation in the bacteria was impaired and the ATP generation was attenuated, so was the metabolism of the bacteria, which facilitated the cell death. Bao et al also found that AgNPs could inhibit new DNA synthesis in the cells.28 Redundant ROS were able to improve the expression of ribosome regulatory factors and motivate ribosome 70S, in the cell’s stationary phase, transformed to an inactive dimer form of 100S, followed by the reduction of ribosome activity and protein synthesis. Our data suggest that oxidative stress may be one of the key mechanisms for AgNPs to induce toxic effects in the bacteria.

Although ROS were boosted in AgNP-treated P. aeruginosa, our proteomic analysis exhibited that the antioxidant enzymes capable of scavenging ROS, including SOD, CAT, and POD, were also mounted. The question whether oxidation or anti-oxidation was in advantage drove us to further understand the activity of these enzymes. Being the first line of defense against oxidation damage in vivo, SOD is able to translate the highly toxic O2− into H2O2; H2O2 is then decomposed by CAT and POD into H2O and O2−. Our data revealed that the activity of SOD in multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa was distinctly high within 4 hours post-AgNP management; however, the activities of CAT and POD were largely reduced, which was consistent with previous studies.29,30 Our results confirmed that although AgNPs induced ROS improvement, the O2− content did not markedly went up in multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa. Other researchers also reported that AgNPs could not induce the generation of O2− in bacteria.31 The ascending level but descending activity of CAT and POD in AgNP-treated P. aeruginosa may be explained as follows: On the one hand, as heavy metals, AgNPs could directly oppress the effect of CAT and POD in a non-competitive pattern; on the other hand, AgNPs enable SOD to strengthen its impact and catalyze the chemical reaction of O2− to H2O2, resulting in the accumulation of H2O2. The enhanced oxidative stress blocks the function of CAT and POD. Accordingly, the bacteria are crippled in degrading and removing excessive H2O2 and peroxides, which gives rise to high content of ROS in vivo.

Apart from antioxidant enzymes like SOD, CAT, and POD, other non-enzymatic antioxidants, such as AsA and GSH, are able to neutralize and remove ROS in the cell. AsA is a kind of water-soluble vitamin, which can mop up the ROS from metabolism and diminish the injury to the cells caused by membrane lipid peroxidation. As a reducing agent, AsA also plays important roles in many biochemical reactions and is used to cope with some diseases.32 Radhakrishnan et al realized that, in AgNP- and AsA-treated Candida albicans, the ROS level was decreased while the number of yeasts was increased.33 GSH is involved in the process of REDOX in organisms by binding peroxides or free radicals to antagonize the oxidative damage to sulfhydryl groups, thus contributing to protect the sulfhydryl proteins or enzymes in the cell membrane, as well as defense the free radicals’ attack to important organs. Previous surveys reported that in AgNPs-processed Phanerochaete chrysosprium, the content of ROS was strongly correlated with that of GSSG; and the consumption of GSH helped block ROS generation.29 Ahamed et al demonstrated that another effective scavenger of ROS, N-acetylcysteine, could effectively inhibit ROS formation and GSH depletion caused by SnO2 or ZnO nanoparticles, thereby preventing the cytotoxicity.34 Our results gave evidences that exogenous antioxidants could facilitate clearance of the ROS in the bacteria and resist the antibacterial effect of AgNPs, which further proves that ROS is crucial in antibacterial mechanisms of AgNPs.

A number of researchers noted that excessive ROS was the cause of apoptosis.35–38 Daniel et al found that the death of bacteria induced by antibiotics displayed the same physiological and biochemical characteristics as apoptosis.39 Other scholars also observed the morphological changes and biochemical reactions related to apoptosis in prokaryotes.40,41 In the present study, the results indicated that AgNPs could induce the apoptosis-like effect on multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa and most was presented in the early stage. Our results were consistent with reports of Bao et al.28

Lu et al founded that AgNPs exhibited strong antimicrobial property against five oral anaerobic bacteria. Nevertheless, their effectiveness on aerobic E. coli was superior to that on anaerobic bacteria.42 Another study on facultative denitrifying P. aeruginosa PAO1 revealed that under anaerobic conditions, AgNPs had antibacterial impact on P. aeruginosa, but under aerobic conditions, this impact was dramatically enhanced.43 It suggests that besides the ROS pathway, other mechanisms exist in the course of AgNPs fighting against microorganisms.

Conclusion

Our results revealed that AgNPs had significant antibacterial effect on antibiotic-resistant P. aeruginosa in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. After AgNPs acting on P. aeruginosa, the cell wall became thin; the cell membrane shriveled and fractured; and the cell constituents leaked out. Furthermore, in the bacteria, the REDOX homeostasis was thrown off and the oxidative stress response was promoted. Hence, the levels of SOD, CAT, and POD were remarkably escalated; on the other hand, as AgNPs inhibited the activity of CAT and POD, the excessive ROS (such as H2O2 and peroxides) could not be timely eliminated, which could result in impaired DNA and ribosome and declined synthesis of the macromolecules. All the above events may work together toward the bacteria death. Although our investigation provides solid evidence that ROS pathway weighs heavily in the course of AgNPs against P. aeruginosa, there are other mechanisms involved in this fight, which merits further research and will be an aim of our next work.

Supplementary materials

Table S1.

The values of MIC and MBC of AgNPs against drug-resistant and multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

| Group of PA (n) | MIC (μg/mL) | MBC (μg/mL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC ( ± S)a | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC range | MBC ( ± S)b | MBC50 | MBC90 | MBC range | |

| Drug-resistant group (12) | 2.596±1.126 | 2.813 | 2.813 | 1.406–5.625 | 3.246±1.056 | 2.813 | 5.625 | 2.813–5.625 |

| Multidrug-resistant group (9) | 2.285±1.492 | 1.406 | 5.625 | 1.406–5.625 | 3.165±0.994 | 2.813 | 5.625 | 2.813–5.625 |

| Total (21) | 2.478±1.250 | 2.813 | 2.813 | 1.406–5.625 | 3.215±1.008 | 2.813 | 5.625 | 2.813–5.625 |

Note:

Multidrug-resistance group vs drug-resistance group, P=0.593;

multidrug-resistance group vs drug-resistance group, P=0.863.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; MBC, minimal bactericidal concentration; MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration; PA, P. aeruginosa.

Table S2.

Differential expression of REDOX-involved proteins detected by TMT-labeled quantitative proteomics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

| Protein description | PA + AgNPsa | PAb | PA + AgNPs/PA ratio | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide dismutase | 1.131±0.043 | 0.864±0.017 | 1.309 | 0.000383 |

| Catalase | 1.128±0.024 | 0.873±0.003 | 1.293 | 3.63E–5 |

| Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit D (PA0269) | 1.117±0.053 | 0.887±0.006 | 1.259 | 0.014638 |

| Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit D (PA2331) | 1.146±0.051 | 0.862±0.043 | 1.33 | 0.001822 |

| Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit D (PA0565) | 1.154±0.066 | 0.870±0.002 | 1.327 | 0.013344 |

| Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C | 1.124±0.021 | 0.861±0.032 | 1.306 | 0.000382 |

| Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit F | 1.229±0.012 | 0.773±0.023 | 1.59 | 1.74E–5 |

| Organic hydroperoxide resistance protein | 1.658±0.026 | 0.356±0.028 | 4.654 | 2.53E–6 |

| Cytochrome c551 peroxidase | 1.141±0.036 | 0.872±0.015 | 1.308 | 0.000216 |

| Thioredoxin reductase | 1.139±0.081 | 0.815±0.106 | 1.397 | 0.016103 |

| Xenobiotic reductase | 1.396±0.019 | 0.591±0.023 | 2.36 | 1.76E–6 |

| Glutaredoxin | 0.849±0.009 | 1.106±0.018 | 0.768 | 1.9693E–5 |

| Cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit P1 | 0.882±0.004 | 1.105±0.009 | 0.798 | 9.28E–7 |

| Cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit P2 | 1.147±0.015 | 0.851±0.016 | 1.347 | 2.05E–5 |

| Cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit N2 | 1.156±0.145 | 0.858±0.018 | 1.347 | 0.014741 |

| Cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit O1 | 0.777±0.027 | 1.202±0.038 | 0.646 | 8.38E–5 |

| Cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit O2 | 1.124±0.026 | 0.877±0.008 | 1.282 | 6.11E–5 |

| Cytochrome bo 3 ubiquinol oxidase subunit 1 | 0.518±0.007 | 1.469±0.117 | 0.353 | 2.28E–5 |

| Cytochrome bo 3 ubiquinol oxidase subunit 2 | 0.408±0.018 | 1.584±0.073 | 0.258 | 1.48E–6 |

| Cytochrome bo 3 ubiquinol oxidase subunit 3 | 0.358±0.047 | 1.636±0.069 | 0.218 | 5.59E–5 |

Note:

P. aeruginosa treated with AgNP;

P. aeruginosa without AgNP treatment.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; PA, P. aeruginosa; TMT, Tandem Mass Tag.

Table S3.

Differential expression of proteins involved in the macromolecular synthesis identified by TMT-labeled quantitative proteomics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

| Protein description | PA + AgNPsa | PAb | PA + AgNPs/PA ratio | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase carboxyl transferase | 0.853±0.007 | 1.133±0.028 | 0.753 | 4.4416E–5 |

| subunit alpha | ||||

| Enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase (NADH) | 0.742±0.028 | 1.253±0.009 | 0.592 | 2.001E–5 |

| 3-Oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase | 0.848±0.006 | 1.160±0.024 | 0.731 | 1.73857E–5 |

| 3-Oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase 2 | 0.846±0.008 | 1.152±0.006 | 0.734 | 4.453E–7 |

| 3-Hydroxydecanoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] dehydratase | 0.857±0.031 | 1.126±0.032 | 0.761 | 0.00052071 |

| Malonyl CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase | 0.785±0.012 | 1.224±0.048 | 0.641 | 5.6695E–5 |

| Beta-ketoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase | 0.850±0.026 | 1.141±0.025 | 0.745 | 0.000175211 |

| Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase | 1.135±0.007 | 0.871±0.003 | 1.303 | 1.3897E–7 |

| Probable acyl-CoA thiolase | 1.135±0.015 | 0.867±0.008 | 1.309 | 4.5E–6 |

| Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase | 0.797±0.013 | 1.199±0.028 | 0.665 | 1.84241E–5 |

| Polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase | 0.839±0.015 | 1.161±0.019 | 0.722 | 2.0224E–5 |

| Adenylosuccinate lyase | 0.788±0.024 | 1.205±0.024 | 0.654 | 3.7295E–5 |

| Phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase | 0.875±0.047 | 1.137±0.057 | 0.769 | 0.0035588 |

| Bifunctional purine biosynthesis protein | 0.785±0.010 | 1.218±0.023 | 0.644 | 2.3803E–6 |

| Probable purine/pyrimidine phosphoribosyl transferase | 0.752±0.014 | 1.258±0.003 | 0.598 | 0.00044469 |

| Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine cyclo-ligase | 0.845±0.033 | 1.144±0.041 | 0.739 | 0.00055562 |

| Phosphoribosylamine-glycine ligase | 0.770±0.003 | 1.234±0.021 | 0.624 | 6.5436E–7 |

| N5-carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthase | 0.860±0.054 | 1.145±0.029 | 0.751 | 0.00174152 |

| Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase large chain | 0.852±0.002 | 1.146±0.004 | 0.744 | 1.1764E–8 |

| Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase small chain | 0.823±0.032 | 1.168±0.017 | 0.704 | 0.000137371 |

| Uridylate kinase | 0.857±0.007 | 1.129±0.009 | 0.759 | 1.0846E–6 |

| Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase, alpha-subunit (Biotin-containing) | 1.140±0.002 | 0.857±0.015 | 1.33 | 0.00129965 |

| Putative 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase | 1.144±0.019 | 0.868±0.008 | 1.317 | 1.77453E–5 |

| 7,8-Dihydroneopterin aldolase | 0.866±0.036 | 1.136±0.080 | 0.762 | 0.0043613 |

| Folylpolyglutamate synthetase | 0.810±0.017 | 1.193±0.034 | 0.679 | 4.2101E–5 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S1 | 0.718±0.009 | 1.270±0.002 | 0.565 | 0.000161656 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S2 | 0.755±0.012 | 1.250±0.028 | 0.604 | 3.1805E–6 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S3 | 0.674±0.006 | 1.326±0.022 | 0.508 | 1.7496E–7 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S4 | 0.697±0.014 | 1.293±0.002 | 0.539 | 0.0003421 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S5 | 0.731±0.013 | 1.289±0.017 | 0.567 | 7.1018E–7 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S6 | 0.744±0.019 | 1.269±0.025 | 0.586 | 4.0811E–6 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S7 | 0.688±0.012 | 1.304±0.030 | 0.527 | 1.4895E–6 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S8 | 0.717±0.010 | 1.285±0.016 | 0.558 | 3.1299E–7 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S9 | 0.694±0.018 | 1.301±0.027 | 0.534 | 2.4156E–6 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S10 | 0.683±0.010 | 1.320±0.009 | 0.517 | 1.1717E–7 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S11 | 0.693±0.010 | 1.293±0.026 | 0.536 | 8.5873E–7 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S12 | 0.675±0.015 | 1.327±0.021 | 0.509 | 8.0841E–7 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S13 | 0.695±0.004 | 1.310±0.009 | 0.53 | 1.1977E–8 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S14 | 0.641±0.005 | 1.368±0.021 | 0.469 | 8.5181E–8 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S15 | 0.71±0.0460 | 1.281±0.020 | 0.554 | 0.000100556 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S16 | 0.765±0.014 | 1.247±0.018 | 0.613 | 1.6871E–6 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S17 | 0.728±0.032 | 1.237±0.027 | 0.588 | 4.2612E–5 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S18 | 0.733±0.024 | 1.259±0.046 | 0.582 | 4.2153E–5 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S19 | 0.673±0.018 | 1.324±0.015 | 0.509 | 1.1598E–6 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S20 | 0.624±0.070 | 1.361±0.150 | 0.458 | 0.00104168 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S21 | 0.654±0.021 | 1.353±0.038 | 0.483 | 3.9375E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L1 | 0.713±0.012 | 1.286±0.030 | 0.555 | 1.8159E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L2 | 0.637±0.005 | 1.361±0.013 | 0.468 | 1.9918E–8 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L3 | 0.706±0.014 | 1.285±0.014 | 0.549 | 6.3875E–7 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L4 | 0.741±0.019 | 1.257±0.013 | 0.589 | 2.4412E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L5 | 0.732±0.015 | 1.261±0.004 | 0.58 | 0.00046125 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L6 | 0.729±0.019 | 1.266±0.032 | 0.575 | 1.59459E–5 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L7/L12 | 0.762±0.021 | 1.242±0.068 | 0.614 | 0.000158888 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L9 | 0.726±0.029 | 1.278±0.016 | 0.568 | 1.987E–5 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L10 | 0.714±0.015 | 1.269±0.014 | 0.563 | 8.4667E–7 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L11 | 0.705±0.014 | 1.308±0.027 | 0.539 | 1.4216E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L13 | 0.761±0.011 | 1.242±0.019 | 0.613 | 1.073E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L14 | 0.741±0.014 | 1.258±0.011 | 0.589 | 7.0989E–7 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L15 | 0.691±0.009 | 1.314±0.035 | 0.526 | 1.388E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L16 | 0.682±0.020 | 1.311±0.049 | 0.52 | 1.90508E–5 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L17 | 0.712±0.077 | 1.262±0.057 | 0.564 | 0.00106437 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L18 | 0.707±0.006 | 1.311±0.044 | 0.539 | 3.4752E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L19 | 0.704±0.012 | 1.304±0.031 | 0.54 | 1.7169E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L20 | 0.709±0.007 | 1.295±0.031 | 0.547 | 1.0428E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L21 | 0.746±0.020 | 1.257±0.038 | 0.594 | 2.1688E–5 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L22 | 0.717±0.008 | 1.285±0.018 | 0.558 | 2.7836E–7 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L23 | 0.707±0.019 | 1.267±0.044 | 0.558 | 2.063E–5 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L24 | 0.718±0.014 | 1.276±0.033 | 0.563 | 3.4807E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L25 | 0.759±0.013 | 1.238±0.015 | 0.613 | 1.0153E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L27 | 0.662±0.015 | 1.341±0.014 | 0.494 | 5.3758E–7 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L28 | 0.730±0.008 | 1.271±0.039 | 0.574 | 3.8545E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L29 | 0.652±0.034 | 1.329±0.021 | 0.491 | 2.06E–5 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L30 | 0.618±0.055 | 1.385±0.062 | 0.446 | 0.000158851 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L31 type B | 0.843±0.045 | 1.160±0.055 | 0.727 | 0.00152433 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L32 | 0.587±0.032 | 1.349±0.069 | 0.435 | 4.2315E–5 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L33 | 0.659±0.031 | 1.340±0.074 | 0.492 | 7.6482E–5 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L34 | 0.607±0.017 | 1.391±0.059 | 0.436 | 4.8286E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L35 | 0.608±0.011 | 1.387±0.077 | 0.438 | 1.80613E–5 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L36 | 0.689±0.019 | 1.309±0.020 | 0.526 | 1.9408E–6 |

| Ribosome modulation factor | 1.743±0.141 | 0.277±0.004 | 6.285 | 1.2295E–6 |

| DNA primase | 0.827±0.052 | 1.179±0.028 | 0.702 | 0.00076473 |

| Ribonuclease HII | 0.465±0.066 | 1.529±0.040 | 0.304 | 0.000159774 |

| Replicative DNA helicase | 0.808±0.023 | 1.174±0.020 | 0.688 | 3.9244E–5 |

| ATP-dependent RNA helicase | 0.796±0.011 | 1.189±0.019 | 0.669 | 2.4613E–6 |

| ATP-dependent RNA helicase | 0.616±0.008 | 1.372±0.005 | 0.449 | 2.9544E–8 |

| Poly(A) polymerase I | 0.854±0.005 | 1.147±0.045 | 0.744 | 0.0058823 |

| Transcription termination factor | 0.781±0.009 | 1.210±0.013 | 0.645 | 5.4598E–7 |

| DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit alpha | 0.763±0.004 | 1.227±0.014 | 0.622 | 1.4663E–7 |

| DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta | 0.751±0.008 | 1.246±0.010 | 0.603 | 1.3205E–7 |

| DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit omega | 0.699±0.017 | 1.294±0.010 | 0.54 | 9.3888E–7 |

| DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta’ | 0.748±0.002 | 1.249±0.013 | 0.598 | 5.5309E–8 |

| Regulatory protein, RsaL | 1.160±0.014 | 0.852±0.031 | 1.362 | 0.000141232 |

| Transcriptional regulator, PtxS | 1.119±0.024 | 0.854±0.037 | 1.311 | 0.00062403 |

| Two-component response regulator, CopR | 1.234±0.050 | 0.785±0.036 | 1.572 | 0.00020184 |

| Two-component response regulator, PprB | 1.200±0.095 | 0.809±0.057 | 1.483 | 0.0030848 |

Notes:

P. aeruginosa treated with AgNP;

P. aeruginosa without AgNP treatment.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; PA, P. aeruginosa; TMT, Tandem Mass Tag.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Plan Project of Hunan Province, China (no. 2017SK2092) and the Project of Hunan Anson Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China (no. H201704040250001).

Footnotes

Author contributions

LC and LW developed the research hypothesis and designed the experiments. SL, YZ, XP, and CJ performed the main experiments and wrote the main manuscript. FZ and ZC analyzed the data. QL, GD, and GW collected the samples. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. Establishment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection: lessons from a versatile opportunist. Microbes Infect. 2000;2(9):1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gellatly SL, Hancock RE. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: new insights into pathogenesis and host defenses. Pathog Dis. 2013;67(3):159–173. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieleg O, Caldara M, Baumgärtel R, Ribbeck K. Mechanical robustness of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Soft Matter. 2011;7(7):3307–3314. doi: 10.1039/c0sm01467b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjarnsholt T, Tolker-Nielsen T, Høiby N, Givskov M. Interference of Pseudomonas aeruginosa signalling and biofilm formation for infection control. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2010;12:e11. doi: 10.1017/S1462399410001420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Chen Y, Hu P, Zhou T, Xu X, Pei X. Risk assessment of infected children with Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia by combining host and pathogen predictors. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;57:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(3):318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elgorban AM, El-Samawaty AEM, Abd-Elkader OH, et al. Bioengineered silver nanoparticles using Curvularia pallescens and its fungicidal activity against Cladosporium fulvum. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2017;24(7):1522–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaheen TI, Abd El Aty AA. In-situ green myco-synthesis of silver nanoparticles onto cotton fabrics for broad spectrum antimicrobial activity. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;118(Pt B):2121–2130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fayaz AM, Ao Z, Girilal M, et al. Inactivation of microbial infectiousness by silver nanoparticles-coated condom: a new approach to inhibit HIV- and HSV-transmitted infection. Int J Nanomed. 2012;7(9):5007–5018. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S34973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu X, Li H, Xiao N. Advancement of near-infrared (NIR) laser interceded surface enactment of proline functionalized graphene oxide with silver nanoparticles for proficient antibacterial, antifungal and wound recuperating therapy in nursing care in hospitals. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2018;187:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernández-Sierra JF, Ruiz F, Cruz Pena DC, et al. The antimicrobial sensitivity of Streptococcus mutans to nanoparticles of silver, zinc oxide, and gold. Nanomedicine. 2008;4(3):237–240. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sondi I, Salopek-Sondi B. Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agent: a case study on E. coli as a model for Gram-negative bacteria. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;275(1):177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shameli K, Ahmad MB, Jazayeri SD, et al. Investigation of antibacterial properties silver nanoparticles prepared via green method. Chem Cent J. 2012;6(1):73. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-6-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salomoni R, Léo P, Montemor AF, Rinaldi BG, Rodrigues M. Antibacterial effect of silver nanoparticles in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2017;10:115–121. doi: 10.2147/NSA.S133415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shrivastava S, Bera T, Roy A, Singh G, Ramachandrarao P, Dash D. Characterization of enhanced antibacterial effects of novel silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2007;18(22):225103. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/18/22/225103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamed S, Emara M, Shawky RM, El-Domany RA, Youssef T. Silver nanoparticles: antimicrobial activity, cytotoxicity, and synergism with N-acetyl cysteine. J Basic Microbiol. 2017;57(8):659–668. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201700087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dasgupta N, Ranjan S, Mishra D, Ramalingam C. Thermal Co-reduction engineered silver nanoparticles induce oxidative cell damage in human colon cancer cells through inhibition of reduced glutathione and induction of mitochondria-involved apoptosis. Chem Biol Interact. 2018;295:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durán N, Marcato PD, Conti RD, Alves OL, Costa FTM, Brocchi M. Potential use of silver nanoparticles on pathogenic bacteria, their toxicity and possible mechanisms of action. J Braz Chem Soc. 2010;21(6):949–959. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiu ZM, Zhang QB, Puppala HL, Colvin VL, Alvarez PJ. Negligible particle-specific antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2012;12(8):4271–4275. doi: 10.1021/nl301934w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dou Y, Huan J, Guo F, Zhou Z, Shi Y. Pseudomonas aeruginosa prevalence, antibiotic resistance and antimicrobial use in Chinese burn wards from 2007 to 2014. J Int Med Res. 2017;45(3):1124–1137. doi: 10.1177/0300060517703573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaye KS, Pogue JM. Infections caused by resistant gram-negative bacteria: epidemiology and management. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35(10):949–962. doi: 10.1002/phar.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma VK, Yngard RA, Lin Y. Silver nanoparticles: green synthesis and their antimicrobial activities. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2009;145(1–2):83–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ullah Khan S, Saleh TA, Wahab A, et al. Nanosilver: new ageless and versatile biomedical therapeutic scaffold. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:733–762. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S153167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi O, Deng KK, Kim NJ, Ross L, Surampalli RY, Hu Z. The inhibitory effects of silver nanoparticles, silver ions, and silver chloride colloids on microbial growth. Water Res. 2008;42(12):3066–3074. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orlov IA, Sankova TP, Babich PS, et al. New silver nanoparticles induce apoptosis-like process in E. coli and interfere with mammalian copper metabolism. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016;11:6561–6574. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S117745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie J, Dong W, Liu R, Wang Y, Li Y. Research on the hepatotoxicity mechanism of citrate-modified silver nanoparticles based on metabolomics and proteomics. Nanotoxicology. 2018;12(1):18–31. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2017.1415389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirai T, Osamura T, Ishii M, Arai H. Expression of multiple cbb3 cytochrome c oxidase isoforms by combinations of multiple isosubunits in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(45):12815–12819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613308113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bao H, Yu X, Xu C, et al. New toxicity mechanism of silver nanoparticles: promoting apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e122535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang Z, He K, Song Z, et al. Antioxidative response of Phanerochaete chrysosporium against silver nanoparticle-induced toxicity and its potential mechanism. Chemosphere. 2018;211:573–583. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.07.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan MS, Qureshi NA, Jabeen F, Asghar MS, Shakeel M, Fakhar-E-Alam M. Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles through economical methods and assessment of toxicity through oxidative stress analysis in the Labeo rohita. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2017;176(2):416–428. doi: 10.1007/s12011-016-0838-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivask A, Bondarenko O, Jepihhina N, Kahru A. Profiling of the reactive oxygen species-related ecotoxicity of CuO, ZnO, TiO2, silver and fullerene nanoparticles using a set of recombinant luminescent Escherichia coli strains: differentiating the impact of particles and solubilised metals. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;398(2):701–716. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3962-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mo Q, Liu F, Gao J, Zhao M, Shao N. Fluorescent sensing of ascorbic acid based on iodine induced oxidative etching and aggregation of lysozyme-templated silver nanoclusters. Anal Chim Acta. 2018;1003:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2017.11.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radhakrishnan VS, Dwivedi SP, Siddiqui MH, Prasad T. In vitro studies on oxidative stress-independent, Ag nanoparticles-induced cell toxicity of Candida albicans, an opportunistic pathogen. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:91–96. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S125010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahamed M, Akhtar MJ, Majeed Khan MA, Alhadlaq HA. Oxidative stress mediated cytotoxicity of tin (IV) oxide (SnO2) nanoparticles in human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2018;172:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woo SH, Park IC, Park MJ, et al. Arsenic trioxide induces apoptosis through a reactive oxygen species-dependent pathway and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in HeLa cells. Int J Oncol. 2002;21(1):57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang L, Luo Y, Sun X, Ju H, Tian J, Yu BY. An artemisinin-mediated ROS evolving and dual protease light-up nanocapsule for real-time imaging of lysosomal tumor cell death. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;92:724–732. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qiu M, Chen L, Tan G, et al. JS-K promotes apoptosis by inducing ROS production in human prostate cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2017;13(3):1137–1142. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tripathi VK, Kumar V, Pandey A, et al. Monocrotophos induces the expression of xenobiotic metabolizing cytochrome P450s (CYP2C8 and CYP3A4) and neurotoxicity in human brain cells. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(5):3633–3651. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9938-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dwyer DJ, Camacho DM, Kohanski MA, Callura JM, Collins JJ. Antibiotic-induced bacterial cell death exhibits physiological and biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2012;46(5):561–572. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hakansson AP, Roche-Hakansson H, Mossberg AK, Svanborg C. Apoptosis-like death in bacteria induced by HAMLET, a human milk lipid-protein complex. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dorsey-Oresto A, Lu T, Mosel M, et al. YihE kinase is a central regulator of programmed cell death in bacteria. Cell Rep. 2013;3(2):528–537. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu Z, Rong K, Li J, Yang H, Chen R. Size-dependent antibacterial activities of silver nanoparticles against oral anaerobic pathogenic bacteria. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2013;24(6):1465–1471. doi: 10.1007/s10856-013-4894-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Z, Yang P, Yuan Z, Guo J. Aerobic condition enhances bacteriostatic effects of silver nanoparticles in aquatic environment: an antimicrobial study on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):7398. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07989-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

The values of MIC and MBC of AgNPs against drug-resistant and multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

| Group of PA (n) | MIC (μg/mL) | MBC (μg/mL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC ( ± S)a | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC range | MBC ( ± S)b | MBC50 | MBC90 | MBC range | |

| Drug-resistant group (12) | 2.596±1.126 | 2.813 | 2.813 | 1.406–5.625 | 3.246±1.056 | 2.813 | 5.625 | 2.813–5.625 |

| Multidrug-resistant group (9) | 2.285±1.492 | 1.406 | 5.625 | 1.406–5.625 | 3.165±0.994 | 2.813 | 5.625 | 2.813–5.625 |

| Total (21) | 2.478±1.250 | 2.813 | 2.813 | 1.406–5.625 | 3.215±1.008 | 2.813 | 5.625 | 2.813–5.625 |

Note:

Multidrug-resistance group vs drug-resistance group, P=0.593;

multidrug-resistance group vs drug-resistance group, P=0.863.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; MBC, minimal bactericidal concentration; MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration; PA, P. aeruginosa.

Table S2.

Differential expression of REDOX-involved proteins detected by TMT-labeled quantitative proteomics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

| Protein description | PA + AgNPsa | PAb | PA + AgNPs/PA ratio | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide dismutase | 1.131±0.043 | 0.864±0.017 | 1.309 | 0.000383 |

| Catalase | 1.128±0.024 | 0.873±0.003 | 1.293 | 3.63E–5 |

| Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit D (PA0269) | 1.117±0.053 | 0.887±0.006 | 1.259 | 0.014638 |

| Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit D (PA2331) | 1.146±0.051 | 0.862±0.043 | 1.33 | 0.001822 |

| Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit D (PA0565) | 1.154±0.066 | 0.870±0.002 | 1.327 | 0.013344 |

| Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C | 1.124±0.021 | 0.861±0.032 | 1.306 | 0.000382 |

| Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit F | 1.229±0.012 | 0.773±0.023 | 1.59 | 1.74E–5 |

| Organic hydroperoxide resistance protein | 1.658±0.026 | 0.356±0.028 | 4.654 | 2.53E–6 |

| Cytochrome c551 peroxidase | 1.141±0.036 | 0.872±0.015 | 1.308 | 0.000216 |

| Thioredoxin reductase | 1.139±0.081 | 0.815±0.106 | 1.397 | 0.016103 |

| Xenobiotic reductase | 1.396±0.019 | 0.591±0.023 | 2.36 | 1.76E–6 |

| Glutaredoxin | 0.849±0.009 | 1.106±0.018 | 0.768 | 1.9693E–5 |

| Cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit P1 | 0.882±0.004 | 1.105±0.009 | 0.798 | 9.28E–7 |

| Cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit P2 | 1.147±0.015 | 0.851±0.016 | 1.347 | 2.05E–5 |

| Cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit N2 | 1.156±0.145 | 0.858±0.018 | 1.347 | 0.014741 |

| Cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit O1 | 0.777±0.027 | 1.202±0.038 | 0.646 | 8.38E–5 |

| Cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit O2 | 1.124±0.026 | 0.877±0.008 | 1.282 | 6.11E–5 |

| Cytochrome bo 3 ubiquinol oxidase subunit 1 | 0.518±0.007 | 1.469±0.117 | 0.353 | 2.28E–5 |

| Cytochrome bo 3 ubiquinol oxidase subunit 2 | 0.408±0.018 | 1.584±0.073 | 0.258 | 1.48E–6 |

| Cytochrome bo 3 ubiquinol oxidase subunit 3 | 0.358±0.047 | 1.636±0.069 | 0.218 | 5.59E–5 |

Note:

P. aeruginosa treated with AgNP;

P. aeruginosa without AgNP treatment.

Abbreviations: AgNP, silver nanoparticle; PA, P. aeruginosa; TMT, Tandem Mass Tag.

Table S3.

Differential expression of proteins involved in the macromolecular synthesis identified by TMT-labeled quantitative proteomics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

| Protein description | PA + AgNPsa | PAb | PA + AgNPs/PA ratio | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase carboxyl transferase | 0.853±0.007 | 1.133±0.028 | 0.753 | 4.4416E–5 |

| subunit alpha | ||||

| Enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase (NADH) | 0.742±0.028 | 1.253±0.009 | 0.592 | 2.001E–5 |

| 3-Oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase | 0.848±0.006 | 1.160±0.024 | 0.731 | 1.73857E–5 |

| 3-Oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase 2 | 0.846±0.008 | 1.152±0.006 | 0.734 | 4.453E–7 |

| 3-Hydroxydecanoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] dehydratase | 0.857±0.031 | 1.126±0.032 | 0.761 | 0.00052071 |

| Malonyl CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase | 0.785±0.012 | 1.224±0.048 | 0.641 | 5.6695E–5 |

| Beta-ketoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase | 0.850±0.026 | 1.141±0.025 | 0.745 | 0.000175211 |

| Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase | 1.135±0.007 | 0.871±0.003 | 1.303 | 1.3897E–7 |

| Probable acyl-CoA thiolase | 1.135±0.015 | 0.867±0.008 | 1.309 | 4.5E–6 |

| Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase | 0.797±0.013 | 1.199±0.028 | 0.665 | 1.84241E–5 |

| Polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase | 0.839±0.015 | 1.161±0.019 | 0.722 | 2.0224E–5 |

| Adenylosuccinate lyase | 0.788±0.024 | 1.205±0.024 | 0.654 | 3.7295E–5 |

| Phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase | 0.875±0.047 | 1.137±0.057 | 0.769 | 0.0035588 |

| Bifunctional purine biosynthesis protein | 0.785±0.010 | 1.218±0.023 | 0.644 | 2.3803E–6 |

| Probable purine/pyrimidine phosphoribosyl transferase | 0.752±0.014 | 1.258±0.003 | 0.598 | 0.00044469 |

| Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine cyclo-ligase | 0.845±0.033 | 1.144±0.041 | 0.739 | 0.00055562 |

| Phosphoribosylamine-glycine ligase | 0.770±0.003 | 1.234±0.021 | 0.624 | 6.5436E–7 |

| N5-carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthase | 0.860±0.054 | 1.145±0.029 | 0.751 | 0.00174152 |

| Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase large chain | 0.852±0.002 | 1.146±0.004 | 0.744 | 1.1764E–8 |

| Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase small chain | 0.823±0.032 | 1.168±0.017 | 0.704 | 0.000137371 |

| Uridylate kinase | 0.857±0.007 | 1.129±0.009 | 0.759 | 1.0846E–6 |

| Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase, alpha-subunit (Biotin-containing) | 1.140±0.002 | 0.857±0.015 | 1.33 | 0.00129965 |

| Putative 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase | 1.144±0.019 | 0.868±0.008 | 1.317 | 1.77453E–5 |

| 7,8-Dihydroneopterin aldolase | 0.866±0.036 | 1.136±0.080 | 0.762 | 0.0043613 |

| Folylpolyglutamate synthetase | 0.810±0.017 | 1.193±0.034 | 0.679 | 4.2101E–5 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S1 | 0.718±0.009 | 1.270±0.002 | 0.565 | 0.000161656 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S2 | 0.755±0.012 | 1.250±0.028 | 0.604 | 3.1805E–6 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S3 | 0.674±0.006 | 1.326±0.022 | 0.508 | 1.7496E–7 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S4 | 0.697±0.014 | 1.293±0.002 | 0.539 | 0.0003421 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S5 | 0.731±0.013 | 1.289±0.017 | 0.567 | 7.1018E–7 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S6 | 0.744±0.019 | 1.269±0.025 | 0.586 | 4.0811E–6 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S7 | 0.688±0.012 | 1.304±0.030 | 0.527 | 1.4895E–6 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S8 | 0.717±0.010 | 1.285±0.016 | 0.558 | 3.1299E–7 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S9 | 0.694±0.018 | 1.301±0.027 | 0.534 | 2.4156E–6 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S10 | 0.683±0.010 | 1.320±0.009 | 0.517 | 1.1717E–7 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S11 | 0.693±0.010 | 1.293±0.026 | 0.536 | 8.5873E–7 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S12 | 0.675±0.015 | 1.327±0.021 | 0.509 | 8.0841E–7 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S13 | 0.695±0.004 | 1.310±0.009 | 0.53 | 1.1977E–8 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S14 | 0.641±0.005 | 1.368±0.021 | 0.469 | 8.5181E–8 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S15 | 0.71±0.0460 | 1.281±0.020 | 0.554 | 0.000100556 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S16 | 0.765±0.014 | 1.247±0.018 | 0.613 | 1.6871E–6 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S17 | 0.728±0.032 | 1.237±0.027 | 0.588 | 4.2612E–5 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S18 | 0.733±0.024 | 1.259±0.046 | 0.582 | 4.2153E–5 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S19 | 0.673±0.018 | 1.324±0.015 | 0.509 | 1.1598E–6 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S20 | 0.624±0.070 | 1.361±0.150 | 0.458 | 0.00104168 |

| 30S ribosomal protein S21 | 0.654±0.021 | 1.353±0.038 | 0.483 | 3.9375E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L1 | 0.713±0.012 | 1.286±0.030 | 0.555 | 1.8159E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L2 | 0.637±0.005 | 1.361±0.013 | 0.468 | 1.9918E–8 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L3 | 0.706±0.014 | 1.285±0.014 | 0.549 | 6.3875E–7 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L4 | 0.741±0.019 | 1.257±0.013 | 0.589 | 2.4412E–6 |

| 50S ribosomal protein L5 | 0.732±0.015 | 1.261±0.004 | 0.58 | 0.00046125 |