Abstract

The interplay of magnetism and spin-orbit coupling on an Fe kagome lattice in Fe3Sn2 crystal produces a unique band structure leading to an order of magnitude larger anomalous Hall effect than in conventional ferromagnetic metals. In this work, we demonstrate that Fe-Sn nanocrystalline films also exhibit a large anomalous Hall effect, being applicable to magnetic sensors that satisfy both high sensitivity and thermal stability. In the films prepared by a co-sputtering technique at room temperature, the partial development of crystalline lattice order appears as nanocrystals of the Fe-Sn kagome layer. The tangent of Hall angle, the ratio of Hall resistivity to longitudinal resistivity, is maximized in the optimal alloy composition of close to Fe3Sn2, implying the possible contribution of the kagome origin even though the films are composed of nanocrystal and amorphous-like domains. These ferromagnetic Fe-Sn films possess great advantages as a Hall sensor over semiconductors in thermal stability owing to the weak temperature dependence of the anomalous Hall responses. Moreover, the room-temperature fabrication enables us to develop a mechanically flexible Hall sensor on an organic substrate. These demonstrations manifest the potential of ferromagnetic kagome metals as untapped reservoir for designing new functional devices.

Introduction

Iron-based alloys and compounds have constituted the outstanding basis for applications, particularly with judicious utilization of their rich magnetism and magneto-transport characteristics1–4. To enrich their functionality further, extensive investigations have continued on iron-based ferromagnetic materials including ordered alloys5, oxides6, and nitrides7. In this study, we exemplify magnetic sensor functions in a ferromagnetic iron-tin alloy that is fabricated to harness massive Dirac bands of the kagome metal Fe3Sn2 (ref.8). Magnetic sensors are capable of electrically detecting a magnetic field9 and are becoming increasingly important towards the acceleration of Internet of Things. Their applications include monitoring of electric current via the Oersted field, electronic compasses and motion detection of mechanical parts in microdevices. In conventional semiconductor Hall sensors, the detection of a magnetic field B (termed instead of magnetic induction, hereafter) relies on the ordinary Hall effect, which converts a flow of electric current to the transverse Hall voltage Vyx (ref.10). Since the output Vyx is proportional to B and the injection current, good sensor performance under a constant input voltage is achieved in III–V semiconductors such as GaAs, InAs, and InSb with a high carrier mobility10. These semiconductor devices are constructed essentially on highly crystalline films with a low carrier density precisely tuned by high-temperature growth. Their bandgaps are, however, inevitably accompanied by substantial temperature (T) dependences of device characteristics. To ensure the stable operation in a wide T range, an external circuit that compensates the T dependence needs to be implemented.

Without changing the basic device structure, the semiconductor can be replaced by a ferromagnetic material if the anomalous Hall effect (AHE) is sufficiently large and provides a linear response to the applied B. Vyx induced by AHE is a nominal function of magnetization M and is proportional to tangent of Hall angle, the ratio of Hall resistivity to longitudinal resistivity; materials design is thus better guided with tangent of Hall angle rather than mobility and carrier density. However, conventional ferromagnetic metals such as Fe, Co, and Ni show low tangent of Hall angle values of less than approximately 0.01 (ref.11), and are not suited to AHE-type Hall sensors. In the past two decades, significant progress has been made in the development of AHE materials and understanding of their physical origins11. Of particular interest is the intrinsic AHE where Berry curvature arising from electronic band topology acts as an effective magnetic field and can produce a large tangent of Hall angle and Vyx. In this context, a ferromagnetic Fe-Sn compound, Fe3Sn2 (Curie temperature TC = 657 K), is attracting attention because of its very large AHE at room temperature8,12,13. The crystal structure consists of alternate stacking of stanene and a bilayer of Fe3Sn with a kagome network of Fe, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. A recent angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopic study proposed that an interplay of the kagome lattice, which in analogy to graphene produces linearly dispersed bands and Dirac points, and spin-orbit coupling yields massive Dirac bands that concentrate Berry curvature8. By positioning the Fermi level within the gap, e.g. with electrostatic gating and impurity doping, quantized AHE14,15 may be realized at room temperature. Fe3Sn2 is, however, the high-temperature phase stable above 607 °C; the bulk crystal is formed by a quenching technique8,12,13,16,17. Recognizing the uniqueness of Fe3Sn2, we focus on the thin film of Fe-Sn kagome compounds18,19 as a candidate for AHE-type Hall sensors (Fig. 1b). Here we demonstrate magnetic sensor functions of nanocrystalline Fe-Sn alloy films prepared by room-temperature sputtering. Despite the lack of macroscopic lattice order, these films clearly bear characteristics of the crystalline Fe-Sn phase diagram and exhibit large and linear AHE responses as in the Fe3Sn2 bulk. This metal-based Hall device can outperform conventional semiconductor Hall sensors in thermal stability. The integration on a bendable polymer sheet thanks to the room-temperature fabrication is demonstrated for potential use in flexible electronics. These findings should accelerate challenges to exploitation of exotic physics hosted by iron and other transition-metal kagome compounds20–23.

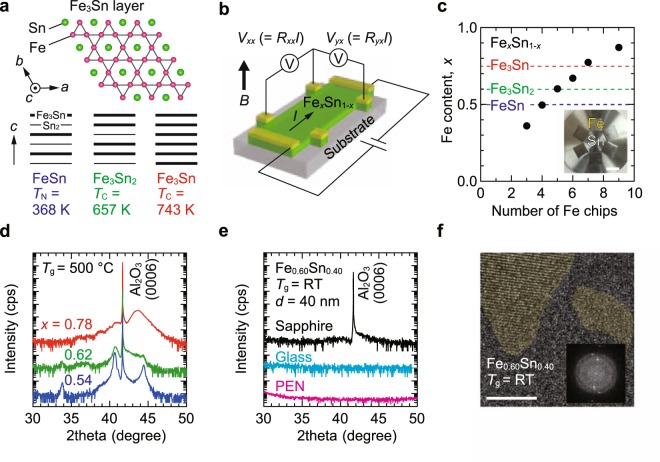

Figure 1.

Sputtered Fe-Sn alloy films. (a) Layered Fe-Sn kagome compounds. The Fe3Sn kagome layer is depicted in the upper side, and the layer stackings in antiferromagnetic FeSn, ferromagnetic Fe3Sn2 and Fe3Sn are displayed in the lower side. (b) The device structure is shown schematically. An excitation current I was injected to an Fe-Sn film on an insulating substrate, and longitudinal voltage Vxx and transverse Hal voltage Vyx were measured. A magnetic field B is applied perpendicularly to the film plane. (c) Fe content x in FexSn1−x films was controlled by changing the Fe chip configuration on the Sn target. Error bars (standard deviations for x) are smaller than the symbols. A photograph when six Fe chips are placed is shown in the inset. The scale bar shows 10 mm. Blue, green, and, red broken lines correspond to x = 0.50 (FeSn), 0.60 (Fe3Sn2), and 0.75 (Fe3Sn), respectively. (d) XRD patterns for FexSn1−x films with x = 0.54, 0.62, and 0.78 grown on sapphire (0001) substrates at Tg = 500 °C. The data are shifted vertically for clarity. The film thicknesses were approximately 40 nm. See the text and Supplementary Fig. S1 for the phase identification of these films. (e) XRD patterns for 40-nm-thick Fe0.60Sn0.40 films on sapphire, glass and, PEN sheet substrates prepared at room temperature. (f) (False color image) Cross-sectional high-resolution transmission electron microscopy image of a room-temperature sputtered Fe0.60Sn0.40 film on a sapphire substrate. The scale bar shows 5 nm. The inset shows a selected area electron diffraction pattern, revealing the presence of nanocrystalline domains.

Results

Fe-Sn nanocrystalline films grown by co-sputtering at room temperature

FexSn1−x alloy films were fabricated by a co-sputtering technique18,19. The two elements were supplied from a single magnetron cathode by mounting Fe chips on a Sn target (Fig. 1c inset and also see Methods section). In the Fe-Sn binary members16, antiferromagnetic FeSn (Néel temperature TN = 368 K) and ferromagnetic Fe3Sn (TC = 743 K, refs24,25) also exist, in which the Fe3Sn kagome layers are accommodated with different stacking sequences (Fig. 1a). To cover these kagome compounds widely, the Fe content x in the films was varied by the Fe chip number as displayed in Fig. 1c. The in-plane distribution of x was as small as a few atomic percent. Figure 1d shows X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of films with various x, grown on single-crystalline sapphire (0001) substrates at a growth temperature Tg of 500 °C. Nearly equimolar mixture of Fe and Sn (x = 0.54) yields a single phase of FeSn (see Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Information for peak identification). For x = 0.62, diffuse reflections of Fe3Sn2 are recognized though FeSn still remains. For x = 0.78, the Fe3Sn phase grows in addition to FeSn. Of the three kagome metals, FeSn is thermodynamically stable and the other two are easily decomposed into FeSn and Sn-rich α-Fe on cooling after high-temperature crystallization16; the above XRD results are consistent with the bulk behavior. As shown in Fig. 1e, the formation of FeSn is found to be suppressed by room-temperature sputtering. Also, macroscopically, the room-temperature grown films do not have crystalline character. Cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy, however, reveals the presence of nanocrystalline domains with typical sizes of as small as a few nanometers, as displayed in Fig. 1f (scale bar, 5 nm). Although d-spacing values calculated from the selected-area electron diffraction pattern (Fig. 1f inset) are not uniquely indexed with one of the three compounds, the clearly visible layered lattice, together with the detailed characterization (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Information), suggests the existence of Fe3Sn2-like domains in the nanocrystalline film with x = 0.60. Considering that further characterization is required for the comprehensive phase analysis, we hereafter focus on composition dependent AHE characteristics in these mixed-phase films rather than quantifying physical properties of each phase.

Comparison of anomalous Hall responses in nanocrystalline and polycrystalline films

Contrary to a naive expectation that the large AHE driven by band topology of the kagome lattice should smear out in such nanocrystalline films, we observed a clear AHE in the room-temperature grown nanocrystalline FexSn1−x. Figure 2a,b show Hall resistivity ρyx and magnetization M plots, respectively, measured at 300 K under the out-of-plane B application. It is obvious that ρyx mirrors M—AHE is mainly responsible for ρyx. The linear ρyx response at low magnetic fields and virtually closed hysteresis loops reflect the magnetization vector rotation from the in-plane easy axis to out-of-plane hard axis (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Information). The wide-range linearity up to about ±0.5 T is beneficial for AHE-type Hall sensors.

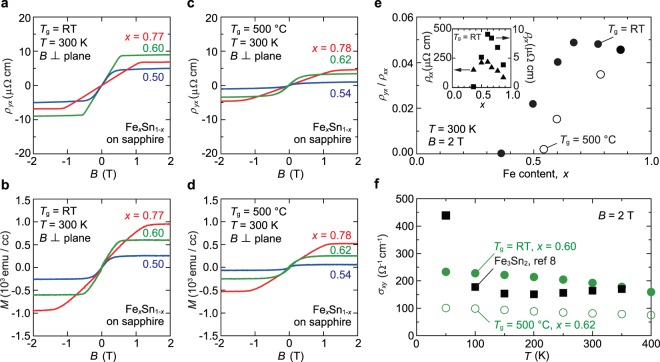

Figure 2.

AHE in nanocrystalline Fe-Sn alloy films. (a,b) Hall resistivity ρyx (a) and out-of-plane magnetization M (b) at T = 300 K measured for room-temperature sputtered nanocrystalline FexSn1−x films as a function of an out-of-plane magnetic field B. The film magnetization was extracted by subtracting diamagnetic contributions from the data measured. (c,d) The results for polycrystalline FexSn1−x films grown at Tg = 500 °C. (e) x dependence of tangent of Hall angle, ρyx/ρxx, at B = 2 T and T = 300 K for nanocrystalline (filled black circles) and polycrystalline FexSn1−x films (open black circles). The inset shows ρxx (triangles) and ρyx (squares) for nanocrystalline FexSn1−x. (f) T dependence of Hall conductivity σxy for a nanocrystalline Fe0.60Sn0.40 film (filled green circles) and a polycrystalline Fe0.62Sn0.38 film (open green circles). For reference, the data of Fe3Sn2 bulk in literature (ref.8) are also included (filled black squares).

The x dependence of saturation ρyx differs from that of the saturation M (Fig. 2a). To get insights into these composition dependences, we performed control experiments using high-temperature grown polycrystalline FexSn1−x films (Tg = 500 °C), shown in Fig. 2c,d. In the polycrystalline films with x = 0.62 and 0.78, the overall anomalous Hall responses and saturation magnetic fields are similar to those of the nanocrystalline ones. In contrast, AHE and M are considerably small for x = 0.54 in which antiferromagnetic FeSn is dominant as revealed by XRD. In Fig. 2e, these x-dependent AHE properties are summarized using tangent of Hall angle, ρyx/ρxx (ρxx: longitudinal resistivity). As a consequence of a sharp ρyx peak around x = 0.60 and ρxx slightly changing with x (Fig. 2e inset), ρyx/ρxx takes a broad maximum around x = 0.60–0.75 in the nanocrystalline films. A weaker but similar trend is also seen for the polycrystalline films that partly contain FeSn, Fe3Sn2, and Fe3Sn (Fig. 1d). Note that such a composition dependence is not expected for mere Sn-rich α-Fe.

In Fig. 2f, T dependence of Hall conductivity σxy = ρyx/(ρxx2 + ρyx2) is compared for nanocrystalline and polycrystalline films with x ~ 0.6 and also bulk Fe3Sn2 in literature8. The occurrence of nearly T-independent σxy in the polycrystalline films, which resembles the intrinsic behavior in Fe3Sn2 single crystals8,13, but with a much smaller σxy than the bulk value suggests a small fraction of Fe3Sn2 domains crystalized by high-temperature sputtering (Tg = 500 °C). Antiferromagnetic FeSn that persistently exists in the polycrystalline film, as found in the decreased M and ρyx (Fig. 2b,d, and also see Fig. S4 in the Supplementary Information), does not give positive contributions to the AHE. In stark contrast, σxy in the nanocrystalline film rivals the bulk data in the entire T range. One obvious reason for this is the suppression of FeSn by room-temperature sputtering. Although it is not clear whether the mechanism of the large AHE discussed for Fe3Sn2 single crystals (ref.8) is valid for such nanocrystalline Fe-Sn films, these observations demonstrate that the AHE in the Fe-Sn alloy system is maximized at specific compositions. The large ρyx and ρyx/ρxx observed for x = 0.77 may suggest that ferromagnetic Fe3Sn (refs24,25) is also a large AHE material, though the transport properties have not been clarified yet.

Thermal stability of the AHE in room-temperature deposited films

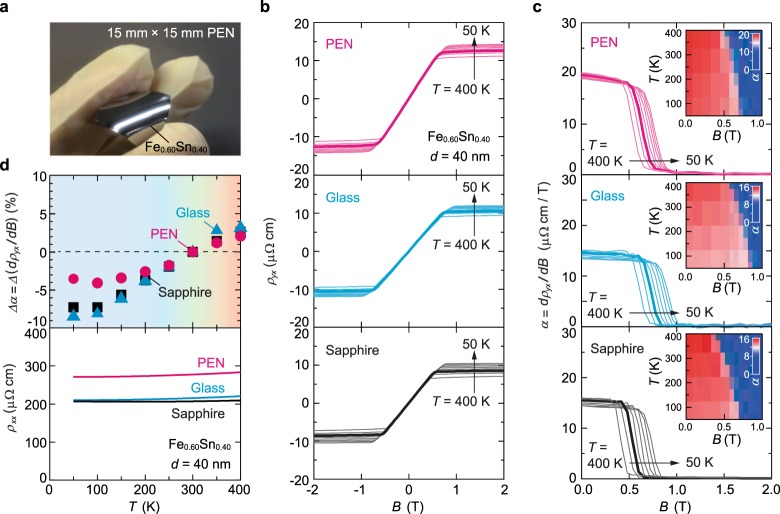

Having confirmed the large AHE in the nanocrystalline FexSn1−x, we now turn to the characterization as a magnetic sensor element. Taking advantages of room-temperature sputtering, we extend our investigation to more commercially available substrates, glass and flexible polyethylene naphthalate (PEN) sheet (Fig. 3a, also see Fig. 1e for their XRD patterns). T-dependent AHE characteristics of Fe0.60Sn0.40 films with thicknesses d~40 nm, displayed in Fig. 3b, are essentially similar on the three substrates, demonstrating that specific substrates are not required to achieve the large AHE. Magnetic-field sensing can be performed in the almost linear ρyx − B region, and the differential coefficient, α = dρyx/dΒ, corresponds to the sensitivity for B via Vyx. As displayed in Fig. 3c and inset, α is nearly constant to a large B of approximately 0.5 T, and is rather insensitive to the T variation (red colored regions in the inset). This is more clearly seen in the upper panel of Fig. 3d, where the temperature stability of α is tracked, defined as Δα = (α (T) − α (T = 300 K))/α (T = 300 K). In a general operation range of T = 200–400 K, Δα is within a few percent, corresponding to approximately 0.02%/K. The small variation in ρxx, shown in the lower panel, gives an advantage over semiconductor devices that are restricted by inherent thermally activated transport26.

Figure 3.

AHE on various substrates. (a) Photograph of a 40-nm-thick nanocrystalline Fe0.60Sn0.40 film on a flexible PEN sheet substrate. (b) ρyx of 40-nm-thick nanocrystalline Fe0.60Sn0.40 films on PEN sheet (magenta), glass (cyan), and sapphire (black) substrates. The AHE measurement was performed at T = 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 350, and 400 K. The data at 300 K are highlighted with bold lines. (c) Differential coefficient α = dρyx/dΒ. The insets display contour plots of α against T and B. (d) The T variation of α defined as Δα = (α (T) − α (T = 300 K))/α (T = 300 K) and ρxx are shown in the upper and lower panels, respectively.

Characterization of Hall sensor responses and flexibility

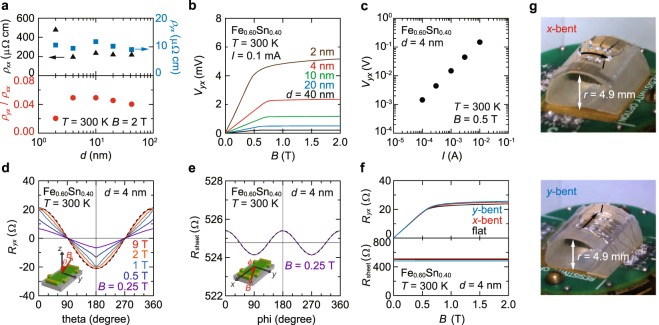

To enhance Vyx further in view of the film thickness d (Vyx = Ι × ρyx/d), we examined the lower bound of d. Judging from the d dependences of ρxx, ρyx, and ρyx/ρxx at B = 2 T (Fig. 4a) and also Vyx versus B curves (Fig. 4b), we determine that the applicable large AHE persists down to d = 4 nm. The d decrease to 2 nm is possible for ρyx, but is accompanied by a sharp rise in ρxx and the drop of ρyx/ρxx. These increase power consumption when supplying a constant excitation current (I). In other words, at the fixed input voltage, Vyx is reduced by the decreased I. The 1-nm-thick device was no longer conductive; d of approximately 2 nm may be the critical thickness where island-like domains start to coalesce and form conduction paths. As presented in Fig. 4c, by injecting I = 10 mA into the 4-nm-thick device, a large Vyx exceeding 0.1 V is generated from a magnetic field of B = 0.5 T.

Figure 4.

Magnetic sensor properties of nanocrystalline Fe0.60Sn0.40 films. (a) Thickness (d) dependences of ρxx, ρyx and ρyx/ρxx measured for a nanocrystalline Fe0.60Sn0.40 film on sapphire (0001) at B = 2 T. (b) Vyx versus B curves measured at I = 0.1 mA for d = 40 nm (black), 20 nm (blue), 10 nm (green), 4 nm (red), and 2 nm (brown). (c) Vyx output characteristics as a function of I. (d) Out-of-plane magnetic field angle (θ) dependence of Ryx for a 4-nm-thick nanocrystalline Fe0.60Sn0.40 film on sapphire (0001). The measurement setup is shown schematically in the inset. The black dotted curve represents a relation Ryx ∝ cosθ. (e) Anisotropic magnetoresistance measurement. Sheet resistance Rsheet was measured in an in-plane B. The in-plane rotation angle (ϕ) is defined in the inset. The dotted curve is a fitting result using a cos2ϕ function. (f) Bending effects on transport properties of a 4-nm-thick Fe0.60Sn0.40 film on PEN. See Fig. 4g for the definition of x-bent and y-bent. The sample was first measured without bending (flat, black curves), and subsequently characterized under x-bent (red) and y-bent (blue) conditions. After these cycles, the device recovered back to the initial flat state (Fig. S5). (g) Photographs of the x-bent and y-bent devices. 4-nm-thick films on PEN sheet substrates were mounted on the surface of a 4.9-mm-radius semicircular jig in two different geometries.

We would like to here note some specific features, which are potentially utilized for three-dimensional magnetic-field sensing. Figure 4d shows out-of-plane magnetic field angle dependences of Ryx under various B, measured for the 4-nm-thick Fe0.60Sn0.40 film on sapphire (0001) (the inset: the schematic measurement configuration). At B = 9 T, Ryx obeys a cosθ relation (black dotted curve) as expected from Meff ∝ Beff = Bcosθ with Meff and Beff being the out-of-plane components of magnetization and magnetic field, respectively. As B is decreased, because of the in-plane magnetic easy axis (see Fig. S3 in the Supplementary information), the actual direction of M vector becomes not to fully follow that of B vector, resulting in a deviation from the cosθ relation. Also, the in-plane magnetoresistance Rsheet vs ϕ, shown in Fig. 4e, indicates an anisotropic magnetoresistance effect even at low B = 0.25 T (the inset: the schematic measurement configuration). By combining these anisotropic responses of Ryx and Rsheet, the magnetic field vector B(θ, ϕ) could be detected with a simple Hall-bar device.

Nanocrystalline FexSn1−x as demonstrated above can be served as a Hall-type magnetic sensor. In particular, the capability of sensor integration onto a flexible substrate is appealing, potentially finding applications in flexible electronics27. We examined the mechanical bending effect on a nanocrystalline FexSn1−x device using flexible PEN substrates. Figure 4f demonstrates that, even under severe bending conditions (see Fig. 4g for the definition of bending geometries), the nanocrystalline Fe0.60Sn0.40 device on PEN offers a reversible operation with an almost unchanged sensor performance (Fig. S5 in the Supplementary Information). Such new functionality enabled by nanocrystalline FexSn1−x films, in combination with its economically and environmentally friendly ingredients, would offer a new type of magnetic sensor design utilizing AHE.

Discussion and Conclusions

Large ρyx at room temperature has also been obtained in ferromagnetic semiconductors28 and metal-insulator composites29. According to the established classification of AHE origins11,30,31, those highly resistive materials, however, are in the poorly conductive region (σxx < ~3 × 103 Ω−1 cm−1). Our nanocrystalline FexSn1−x is essentially a metal with σxx as high as mid - 103–104 Ω−1 cm−1, being in a different category called the intrinsic region (Fig. S6 in the Supplementary Information). In fact, it is observed in nanocrystalline FexSn1−x films that σxy is rather independent of σxx, as being consistent with intrinsic mechanisms. At present, the sensitivity of our device is about one order of magnitude lower than those of the state-of-the-art GaAs and Si Hall sensors32. If the Berry curvature mechanism8 holds for the AHE in nanocrystalline FexSn1−x films, the device performance could be further improved by Fermi-level tuning into the gap at the Dirac point8. Such an intrinsic approach, in addition to its critical importance for the next-generation of Hall sensors, may also lead to devices that incorporate exotic quantum transport phenomena, e.g., quantized AHE. We believe that the thin-film structure would be the key enabler for exploration of new functionality that emerges on the kagome lattice.

Methods

Thin-film growth

FexSn1−x alloy films were fabricated by RF magnetron sputtering. The RF power was 50 W, and Ar gas pressure was 0.5 Pa for x < 0.87 and 0.8 Pa for x = 0.87. The typical growth rate was approximately 4 nm/min as checked by X-ray reflectivity measurement and also with a surface profiler. For films with d ≤ 4 nm, the surface was covered with a 15-nm-thick SiOx insulating layer to prevent oxidation. The SiOx layer was formed by RF magnetron sputtering using a SiO2 target at an Ar gas pressure of 0.5 Pa. Compositional analysis of the films was performed with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy.

AHE and magnetization measurements

Electrical transport properties were measured with a VersaLab, a Physical Property Measurement System (Quantum Design) and a source-measure unit. Films were patterned into a Hall-bar structure (1b), and electrical contacts were made with an indium solder. The aspect ratio of electrode-electrode distance for Vxx versus that for Vyx was approximately unity. To remove thermoelectric and geometric effects, the measured data were symmetrized for Vxx and anti-symmetrized for Vyx against B as widely adopted to these measurements. Magnetization measurements were carried out using a vibrating sample magnetometry mode of VersaLab.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank K. Nakahara, M. Kawasaki, H. Kato, N. Shibata, and H. Nishikawa for their helpful advice and K. Takanashi, S. Ito and F. Sakamoto for their assistance with experiments. This work was partly supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Nos. 25000003 and JP15H05853) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and Kumagai Foundation for Science and Technology.

Author Contributions

A.T. and K.F. designed the experiments. K.F. and Y.S. fabricated samples. Y.S., K.F. and J.S. performed electrical measurements. Y.S., J.S. and T.S. contributed to magnetization measurements. Y.S., K.F. and A.T. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-39817-8.

References

- 1.Coey JMD. Permanent magnet applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2002;248:441–456. doi: 10.1016/S0304-8853(02)00335-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugimoto M. The past, present, and future of ferrites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1990;82:269–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.1999.tb20058.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss RJ. The origin of the ‘Invar’ effect. Proc. Phys. Soc. 1963;82:281. doi: 10.1088/0370-1328/82/2/314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf SA, et al. Spintronics: a spin-based electronics vision for the Future. Science. 2001;264:1488–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1065389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takanashi K, Mizuguchi M, Kojima T, Tashiro T. Fabrication and characterization of L10-ordered FeNi thin films. J. Phys. D.: Appl. Phys. 2017;50:483002. doi: 10.1088/1361-6463/aa8ff6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laurent S, et al. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, stabilization, vectorization, physicochemical characterizations, and biological applications. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2064–2110. doi: 10.1021/cr068445e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharyya S. Iron nitride family at reduced dimensions: a review of their synthesis protocols and structural and magnetic properties. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015;119:1601–1622. doi: 10.1021/jp510606z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye L, et al. Massive Dirac fermions in a ferromagnetic kagome metal. Nature. 2018;555:638–642. doi: 10.1038/nature25987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenz J, Edelstein AS. Magnetic sensors and their applications. IEEE Sensors J. 2006;6:631–649. doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2006.874493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heremans J. Solid-state magnetic field sensors and applications. J. Phys. D. 1993;26:1149–1168. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/26/8/001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagaosa N, Sinova J, Onoda S, McDonald AH, Ong NP. Anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010;82:1539–1592. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.82.1539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kida T, et al. The giant anomalous Hall effect in the ferromagnet Fe3Sn2—a frustrated kagome metal. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2011;23:112205. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/23/11/112205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Q, Sun S, Zhang X, Pang F, Lei H. Anomalous Hall effect in a ferromagnetic Fe3Sn2 single crystal with a geometrically frustrated Fe bilayer kagome lattice. Phys. Rev. B. 2016;94:075135. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.94.075135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haldane FDM. Model for Quantum Hall effect without Landau levels: condensed-matter realization of the “parity anomaly”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1988;61:2015–2018. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.61.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang. C-Z, et al. Experimental observation of the quantum anomalous Hall effect in a magnetic topological insulator. Science. 2013;340:167–170. doi: 10.1126/science.1234414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giefers H, Nicol M. High pressure X-ray diffraction study of all Fe-Sn intermetallic compounds and one Fe-Sn solid solution. J. Alloys Compd. 2006;422:132–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2005.11.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenner LA, Dee AA, Wills AS. Non-collinearity and spin frustration in the itinerant kagome ferromagnet Fe3Sn2. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2009;21:452202. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/21/45/452202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haftek E, Tan M, Barnard JA. Microstructure and magnetic properties of ferromagnetic Fe-Sn alloy thin films. Ultramicroscopy. 1992;47:400–407. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(92)90171-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao J, et al. Giant Hall effect in FexSn100−x granular alloy films. J. Appl. Phys. 2003;93:1851. doi: 10.1063/1.1536719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakatsuji S, Kiyohara N, Higo T. Large anomalous Hall effect in the colinear antiferromagnet at room temperature. Nature. 2015;527:212–215. doi: 10.1038/nature15723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuroda K, et al. Evidence for magnetic Weyl fermions in a correlated metal. Nat. Mater. 2017;16:1090–1095. doi: 10.1038/nmat4987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nayak AK, et al. Large anomalous Hall effect driven by a nonvanishing Berry curvature in the noncolinear antiferromagnet Mn3Ge. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1501870. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu E, et al. Giant anomalous Hall effect in a ferromagnetic kagome-lattice semimetal. Nat. Phys. 2018;14:1125–1131. doi: 10.1038/s41567-018-0234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trumpy G, Both E, Djega-Mariadassou C, Lecocq P. Mössbauer-Effect studies of Fe-Sn Alloys. Phys. Rev. B. 1970;2:3477–3490. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.2.3477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sales BC, Saparav B, McGuire MA, Singh DJ, Parker DS. Ferromagnetism of Fe3Sn and alloys. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:7024. doi: 10.1038/srep07024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jankowski J, El-Ahmar S, Oszwaldowski M. Hall sensors for extreme temperatures. Sensors. 2011;11:876–885. doi: 10.3390/s110100876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohta S, Ando A, Chiba D. A flexible giant magnetoresistive device for sensing strain direction. Nat. Electron. 2018;1:124–129. doi: 10.1038/s41928-018-0022-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tu NT, Hai PN, Tanaka M. High-temperature ferromagnetism in heavily Fe-doped ferromagnetic semiconductor (Ga,Fe)Sb. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016;108:192401. doi: 10.1063/1.4948692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonntag J. The Origin of the Giant Hall Effect in Metal-Insulator Composites. Open Journal of Composite Materials. 2016;5:78–90. doi: 10.4236/ojcm.2016.63008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onoda S, Sugimoto N, Nagaosa N. Intrinsic versus extrinsic anomalous Hall effect in ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;97:126602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.126602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukumura T, et al. A scaling relation of anomalous Hall effect in ferromagnetic semiconductors and metals. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2007;46:L642. doi: 10.1143/JJAP.46.L642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ripka P, Janosek M. Advances in magnetic field sensors. IEEE Sensors Journal. 2010;10:1108. doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2010.2043429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.