Abstract

RNA editing converting cytidines into uridines is a hallmark of gene expression in land plant chloroplasts and mitochondria. Pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins have a key role in target recognition, but the functional editosome in the plant organelles has remained elusive. Here we show that individual Physcomitrella patens DYW-type PPR proteins alone can perform efficient C-to-U editing in Escherichia coli reproducing the moss mitochondrial editing. Single amino acid exchanges in the DYW domain abolish RNA editing, confirming it as the functional cytidine deaminase. The modification of RNA targets and the identification of numerous off-targets in the E. coli transcriptome reveal nucleotide identities critical for RNA recognition and cytidine conversion. The straightforward amenability of the new E. coli setup will accelerate future studies on RNA target recognition through PPRs, on the C-to-U editing deamination machinery and towards future establishment of transcript editing in other genetic systems.

Bastian Oldenkott et al. show that single moss pentatricopeptide repeat proteins with a DYW domain are sufficient to drive efficient C-to-U RNA editing in Escherichia coli. They demonstrate that the E.coli system is an easy to manipulate platform for future studies on RNA target recognition and C-to-U RNA editing.

Introduction

C-to-U RNA editing of organellar messenger RNAs (mRNAs) is nearly omnipresent in land plants and can affect up to thousands of sites in chloroplast or mitochondrial transcriptomes, respectively1,2. Core to the recognition of specific cytidines for conversion into uridines are plant-specific RNA-binding pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins1,3,4. PPR arrays in these editing factors are of the PLS type with long (L, 35–36aa) and short (S, 31–32aa) PPR variants alternating with the canonical P-type PPRs of 35 amino acids. The three carboxy-terminal PPRs of PLS-type PPR proteins generally differ in their amino acid conservation and are labeled P2, L2, and S2. Many additional trans-acting proteins contribute to complex editosomes in flowering plants5–7. Early land plant lineages, however, seem to lack such additional components. All of the few C-to-U RNA editing sites in the moss Physcomitrella patens have been assigned to specific editing factors addressing one or maximally two edits, respectively8–10. All these editing factors are PPR proteins with a terminal DYW domain, which had been proposed to be the cytidine deaminase needed for the biochemical conversion of cytidine into uridine11. Further circumstantial evidence supported that concept12–16, but other studies questioned the idea of the DYW domain as a cytidine deaminase17,18.

Studying plant RNA editing in vivo is time-consuming and labor-intensive and hindered by occasionally strong mutant phenotypes, lack of a transformation protocol for plant mitochondria, and the background of interacting proteins in the native system.

Here we demonstrate that single DYW-type plant editing factors can faithfully edit their corresponding targets in Escherichia coli. Single amino acid mutations in the DYW domain clearly demonstrate its role as the cytidine deaminase acting on polyribonucleotides. Mutations in the cognate RNA targets and within the PLS-type PPR arrays essentially confirm the current PPR-RNA recognition code, but also reveal that some conceptually improved PPR-RNA matches may decrease rather than improve RNA editing and that at least some L-type PPRs evidently play an important role in the process. We demonstrate that changing key amino acid positions in a PPR will allow for a corresponding nucleotide change in the RNA, resulting in a designed target switch. The identification of numerous off-targets in the E. coli background transcriptome will accelerate our understanding of RNA target recognition by PLS-type PPRs.

Results

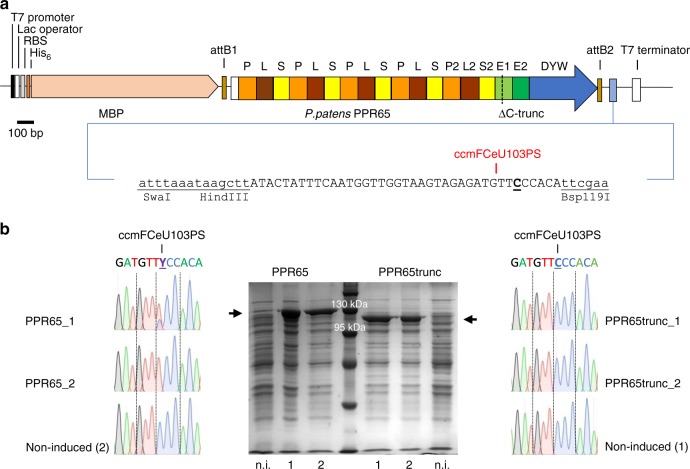

Escherichia coli expression system

The bacterial system allows for straightforward identification of the key determinants for efficient C-to-U editing both on the side of the editing protein and on the RNA target side. PPR65 has been identified as the editing factor addressing editing event ccmFCeU103PS in P. patens mitochondria (for nomenclature see Fig. 1) and binding to its target was previously demonstrated in vitro by RNA electromobility shift assays after successful expression in E. coli8. We adapted an expression system (see Methods), allowing insertion of target sequences behind the editing factor coding sequences on the same transcript (Fig. 1a). Indeed, isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-induced E. coli cultures edited the target cytidine very efficiently from 70 up to 100% (Fig. 1b). Deleting the C terminus of PPR65, essentially reducing it to its array of 15 PLS-type PPRs, abolished C-to-U conversion completely (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Strategy for establishing a plant C-to-U RNA editing setup in Escherichia coli, shown for P. patens pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) protein PPR65 and its target editing site ccmFCeU103PS. a The PPR65 coding sequence is inserted into the pETG_41K vector system resulting in the fusion to a His6-tagged maltose binding protein (MBP, RBS: ribosome binding site). The editing target sequence is cloned downstream. Expression is driven by a T7 promoter inducible by isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Editing site is labeled with target gene name (ccmFC encoding subunit FC of the cytochrome c maturation machinery) followed by eU, transcript position, and resulting amino acid change. b Editing of ccmFC103PS by PPR65 relies on its C-terminal domain in E. coli. Shown are protein expression and sequencing electropherograms revealing editing frequencies for two independent E. coli cultures with PPR65 and C terminally truncated PPR65, respectively, and non-induced samples as negative controls. Bacterial lysates on a denaturing sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel correspond to ca. 4.5 × 107 cells of a 20-h culture after IPTG induction (n.i. = non-induced, PPR65trunc = C terminally truncated)

Specific nucleotides are required for RNA targeting

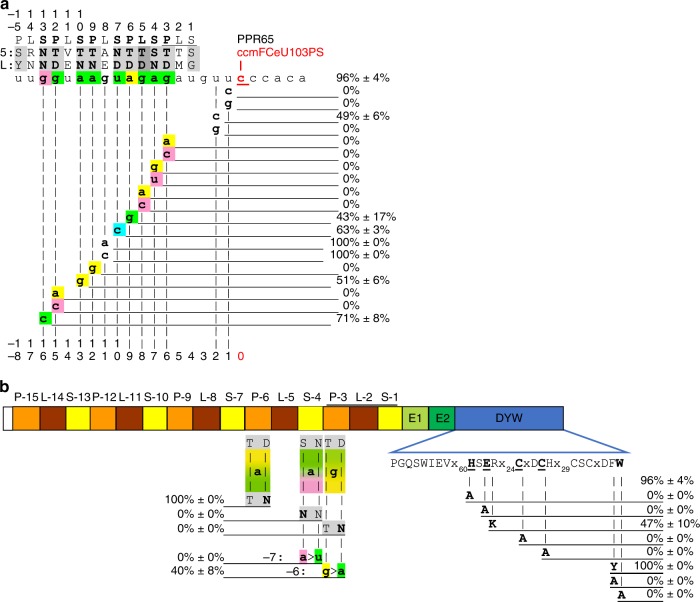

We created a series of RNA target mutants to check for the relevance of nucleotide identities juxtaposed with the PPR array according to the PPR-RNA recognition rules1 (Fig. 2a). In PPR65, six out of eight PPRs perfectly match the nucleotide recognition code for P- and S-type repeats (Fig. 2). Moreover, PPR65 exceptionally features an L-type PPR (L-5TD), which could perfectly match the expected guanosine in the target, although the functional contribution of L-type PPRs is currently not understood. All exchanges of matching purines by transversions or transitions, including the G juxtaposed with PPR L-5TD, abolish RNA editing completely except for an A-to-G change in position −13 that is moderately tolerated with reduced editing of ca. 51% (Fig. 2a). In contrast, exchange of the G in position −11 opposite of PPR L-8AE does not affect RNA editing. Converting the matching uridine in position −10 opposite of PPR S-7ND to cytidine reduces editing efficiency to ca. 63% (Fig. 2a). These data clearly underline the generally larger importance of PPRs matching purines over those matching pyrimidines. Notably, the conceptually improved matches opposite of PPR P-6TD (A-to-G) and of PPR S-13NN (G-to-C) also led to detectable reduction of editing efficiencies to ca. 43% and 71%, respectively. A complete loss of RNA editing was observed after U-to-G transversions in positions −1 and −2 upstream of the editing site. Converting a U to C in position −1 likewise abolished editing completely, whereas the same change in position −2 led to reduced editing of ca. 49% (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

DYW-type pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) protein PPR65 and its corresponding RNA editing site ccmFCeU103PS tested for target nucleotide (a) and amino acid mutations (b) in the new E. coli setup. a Labels of PLS-type PPRs use backward numbering (top numbers) with S-1 juxtaposed to nucleotide −4 (bottom numbers) upstream of the editing site (red) and indicate the respective amino acid identities in PPR positions 5 and L (last). The terminal P2L2S2 PPR triplet is underlined. Target nucleotide color shading is according to the PPR-RNA code for P- and S-type PPRs (gray, T/S + N: A, T/S + D: G, N + N: C/U, N + S: C > U, N + D: U > C) with green for perfect matches, blue for pyrimidine transitions, yellow for purine transitions, and pink for mismatches. Exceptionally, L-type PPR L-5TD (dark gray) would also match the G in position −8 of the native target. b Amino acid identities 5 or L of selected PPRs and conserved residues of the assumed Zn2+-binding cytidine deaminase signature and the carboxy-terminal DFW motif in the DYW domain (shown in blue) were changed as indicated. Introduced PPR mutations (left part, bold) were attempted to be compensated with corresponding mutations A-to-U and G-to-A in positions −7 and −6 in the target, respectively. RNA editing efficiencies are given as the mean ± s.d. of at least three biological replicates (independent primary E. coli clones) when at least some RNA editing activity was initially detected. The absence of RNA editing was confirmed with at least an additional clone. Primary data are listed in Supplementary Data 1

Mutations in the PLS-type PPRs and a target switch

We selected PPRs P-6TD, S-4SN, and P-3TD in PPR65 for converting one of the critical residues for ribonucleotide recognition 5 or L (last) in each PPR to complement the findings for target mutations. Improving the fit of P-6TD to the A by converting it to P-6TN yields perfect editing (Fig. 2b). The native mismatch in position −9 can thus be corrected by a mutation on the protein side, but is surprisingly disfavored by an A-to-G mutation on the target side (Fig. 2a), demonstrating that yet further details of RNA recognition by editing factors remain to be elucidated. Mutating S-4SN matching an A in position −7 to S-4NN or changing P-3TD matching a G in position −6 to P-3TN both abolished editing completely. PPR65 mutant versions were combined with targets holding the appropriate nucleotides (T and A) at position −7 and −6, respectively. The target switch succeeded for the purine G-to-A transition resulting in the recovery of editing to ca. 40%, but not for the A-to-U transversion (Fig. 2b).

DYW domain mutations confirm its cytidine deaminase function

We also exchanged key residues of the DYW domain assumed relevant for its presumed function as a cytidine deaminase, notably including those considered important for Zn2+ ion coordination (Fig. 2b, HxERx24CxxC). A single amino acid conversion into alanine at any of the important residues led to a complete loss of RNA editing. Position 4 of this signature is alternatively lysine (K) or arginine (R) in other editing factors. Converting the native arginine of PPR65 into lysine, however, reduced editing efficiency to ca. 47%. Similarly, the tyrosine (Y) of the name-giving tripeptide motif at the end of the DYW domain is occasionally replaced by phenylalanine (F), like in PPR65. The substitution of the one aromatic amino acid for the other did not result in a detectable reduction of editing efficiency (Fig. 2b). Converting the phenylalanine into alanine, however, abolishes editing activity completely, just like the mutation of the terminal tryptophan (W).

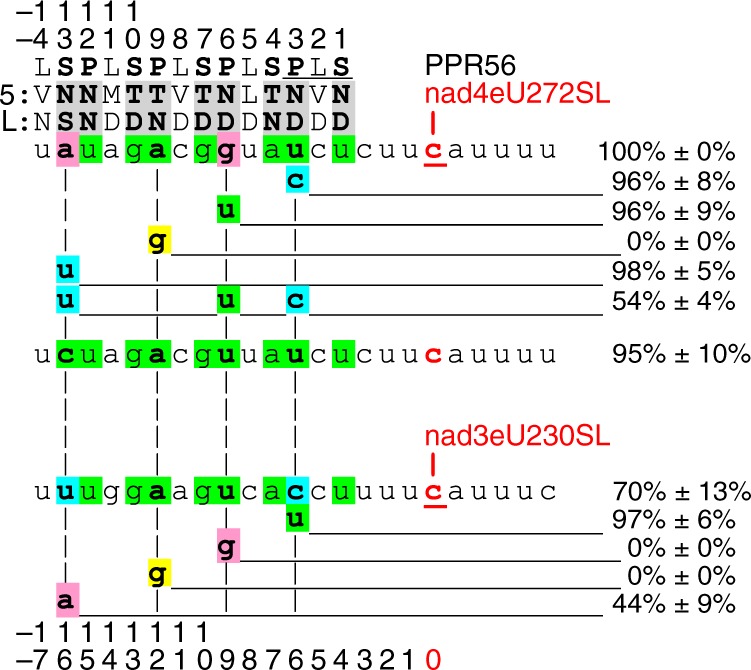

PPR56 RNA targeting in E. coli reflects activity in planta

We next focused on PPR56 as a second Physcomitrella editing factor for further studies because it serves two RNA editing targets, nad4eU272SL with 100% editing efficiency and nad3eU230SL with variably observed editing of 70–100% in planta19–21. The two targets were cloned alternatively behind the PPR56 coding sequence like that shown for PPR65 (Fig. 1). PPR56 in the E. coli setup fully reflects the native situation in the moss with partial editing detected for the nad3eU230SL target, and highly efficient editing of the nad4eU272SL target. The two alternative targets provide the option for individual mutations to be introduced for better matches to the respective other target in positions −6, −9, and −16 in the E. coli setup. Neither the individual changes nor the modification of the nad4 target sequence with two point mutations for a complete match resulted in clear reductions of RNA editing in the nad4 target after 20 h. Only introducing the mutations in positions −6, −9, and −16 jointly towards matching the nad3 target led to reduction of the editing efficiency to ca. 54% after 20 h, indicating a cooperative effect (Fig. 3). The corresponding changes in the nad3 target led to stronger changes and consistently follow the PPR-RNA recognition rules. The U-to-G mutation in position −9 abolishes editing, in contrast to the native nad4 target, and the U-to-A mutation in −16 reduces editing to ca. 44%, whereas editing increases to ca. 97% with the C-to-U mutation in position −6 for improved matching to P-3ND. Purine transition A-to-G in position −12 matching P-9TN in both targets led to complete loss of editing like that observed for PPR65.

Fig. 3.

Dual-target editing factor pentatricopeptide repeat protein PPR56 expressed in the E. coli system with efficient editing of nad4eU272SL and partial editing of nad3eU230SL site. Designation of PPRs, numbering of positions, shading, and the scoring of editing efficiencies is as in Fig. 2. Single point mutations have been introduced into each of the two targets to match the respective other sequence. For the nad4eU272SL target, a combination of all three exchanges and a variant to fully match the PPR-RNA code concept have also been tested (middle). Additionally, the perfect match of an A in position −12 opposite of P-9TN was changed into G in both targets

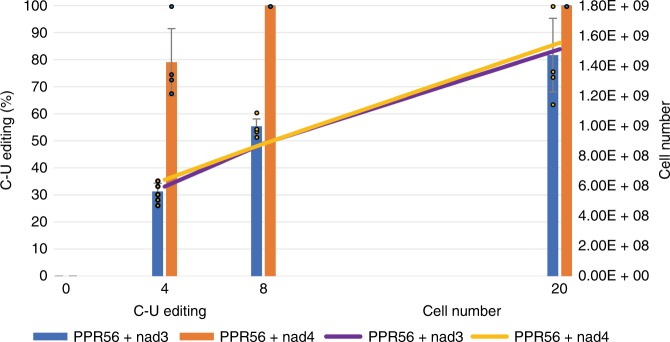

Increase in RNA editing efficiency over time

Given the efficient editing of the nad4 targets in E. coli, we also tested shorter time periods after induction, which may allow for better differentiation (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 1 and 2). We noticed that RNA editing efficiencies increase over time. The differences in editing of the original nad3 and nad4 targets were even more obvious after 4 and 8 h than after 20 h of incubation upon induction (Fig. 4, Supplementary Data 2). The strong impact of the nucleotide at position −6 (opposite of P-3ND) to editing efficiency becomes apparent after 8 h with the U-to-C change in the nad4 target leading to a reduction of editing from 100 to 69%. Vice versa, the corresponding exchange of C to U at position −6 in the nad3 target improves editing to 91% already after 8 h (Supplementary Data 1).

Fig. 4.

RNA editing by pentatricopeptide repeat protein PPR56 at its nad3 and its nad4 target increases over time. RNA editing levels and E. coli cell numbers were determined for dual-target editing factor PPR56 at 4, 8, and 20 h after induction of expression with 0.4 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cell numbers were calculated based on the culture density mean at OD600 (s.d. 0.01–0.05) of the biological and technical replicates per time point. Three experiments with independent primary clones (biological replicates) plus 1–2 technical replicates per biological replicate were included. Dots represent individual editing data used for calculating means ± s.d. Primary data are listed in Supplementary Data 2

Off-targeting in the E. coli system

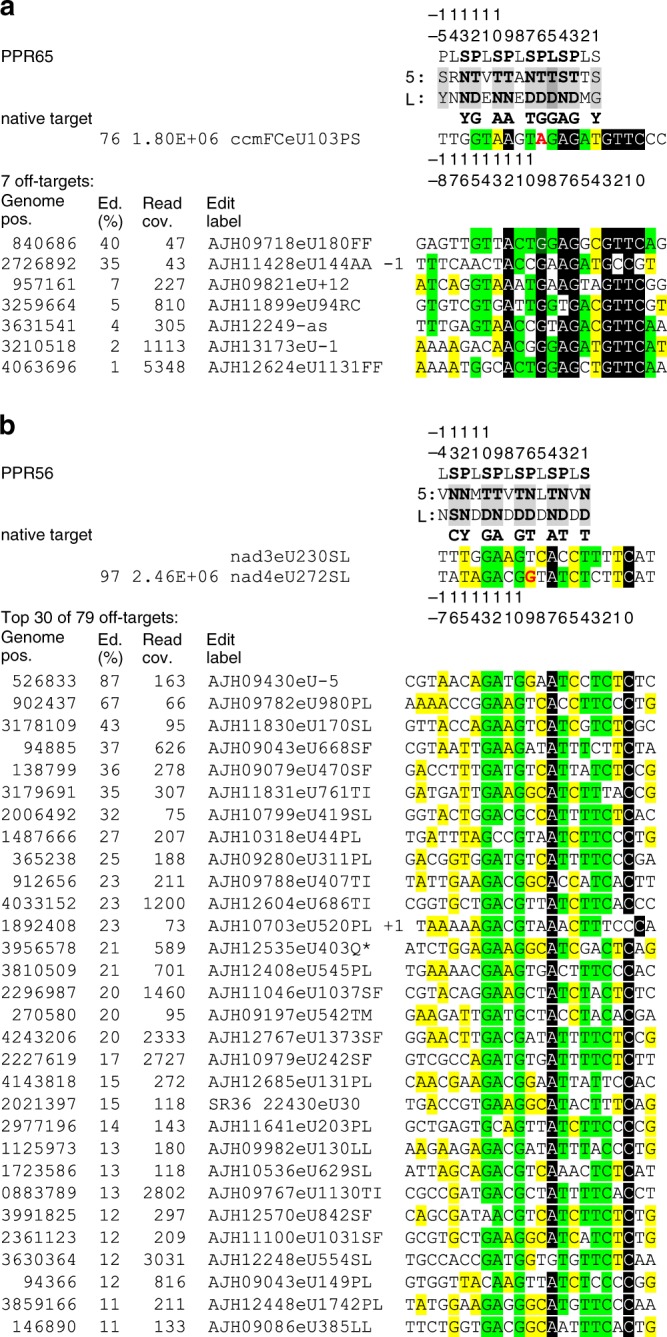

Evidently, the E. coli background transcriptome may offer secondary off-targets of C-to-U editing for the introduced plant RNA editing factors. To investigate this possibility, we performed RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) transcriptome analyses after expression of the two editing factors. This revealed only seven off-targets for PPR65, most with editing efficiencies below 10%, but 79 sites of C-to-U editing for editing factor PPR56, with one site in a 5′-untranslated region even edited in 87% of the transcripts (Fig. 5). Comparing sequences upstream of the off-target cytidines fit expectations well with conserved nucleotide identities opposite of the relevant PPRs for the natural targets of PPR65 and PPR56, respectively. No conservation is discernible for the more upstream positions juxtaposed with further N-terminal PPRs corroborating their inferior relevance. Whereas positions −1 to −3 are identical in six of seven off-targets of PPR65, these positions are much less conserved among the PPR56 off-targets (Fig. 5). This could explain the much higher number of off-targets detected for PPR56, already targeting two editing sites in its native environment. Editing efficiencies among the off-targets overall decrease with deviations from the majority consensus. Only minor preferences occur in positions juxtaposed with L-type repeats, but in the larger PPR56 data set (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 1) the majority of nucleotide always matches at least one of the native targets best. Notably, all seven off-targets of PPR65 show a G in position −9 matching the expectation for PPR P-6TD instead of the alternative A present in the native target. Likewise, it is interesting to note that G dominates in position −9 of the PPR56 off-targets, conceptually mismatched with PPR P-6ND but shared with the native, efficiently edited nad4 target, while its less efficiently edited nad3 counterpart features a uridine, fitting the PPR code in that position.

Fig. 5.

Native and off-targets of C-to-U RNA editing by pentatricopeptide repeat protein PPR65 a or PPR56 b. Off-targets are sorted with decreasing editing efficiencies and labeled using the suggested editing nomenclature (Edit label), preceded by the E. coli BL21 genome position (accession CP010816.1, genome pos.), average percentage of editing (Ed%), and total RNA read coverage (Read cov.) detected in two RNA-seq replicates (no positions are given for the native targets). One case of editing in antisense to an annotated gene is indicated by “as” and two cases of improved fit by one-nucleotide shifts are indicated by +1 and −1, respectively. Only the top 30 hits are shown for PPR56, the full list of off-targets is given in Supplementary Fig. 1. Shading in black, light green, and yellow indicate nucleotide conservation in 90%, 60%, or 30% of sequences. Mismatching nucleotides in native targets are highlighted in red

Methodological issues in the E. coli setup

Transcript abundance, RNA secondary structures, and protein abundance are evidently among the many factors other than the linear matches of PPRs to their RNA targets that could contribute to RNA editing efficiencies. We routinely checked protein expression (Supplementary Fig. 2) and used the RNAfold WebServer22 to predict possible secondary structures in our targets, which did not reveal any (stable) RNA structures to be correlated with reduced or increased editing efficiencies (Supplementary Data 3). The identification of off-targets in the E. coli transcriptome allowed us to test whether placing a target directly behind the coding sequence of a cognate editing factor would in some, yet to be explained, way promote editing efficiency. Accordingly, we cloned AJH09430eU-5, the most efficiently edited off-target of PPR56, edited to 87% (Fig. 5), into our vector system. Rather than further increasing, RNA editing efficiencies dropped to 37% for the cloned off-target (Supplementary Data 1), confirming that the one-transcript system does not per se favor editing by factors encoded upstream on the same transcript. Individual RNA editing efficiencies may certainly be affected by numerous factors contributing to specific transcript turnover including its mode of transcription, its folding and unfolding, its processing and degradation, and the presence of RNA helicases or other RNA-binding proteins in a given genetic environment.

Discussion

The E. coli RNA editing setup ultimately demonstrates that single DYW-type PPR proteins can be enough for efficient C-to-U RNA editing without any additional plant organelle-specific factors. The complete loss of RNA editing in DYW domain mutants with single amino acid changes in six independent positions (Fig. 2b) strongly supports that the DYW domain alone is the cytidine deaminase operating on RNA. It is very likely that the increasingly complex editosomes of flowering plants mainly serve to recruit functional DYW domains by (multiple) protein–protein interactions in trans when it was lost from an editing factor that became reduced to target recognition13,23–25. The E. coli setup scores ultimate editing efficiencies rather than RNA-binding efficiencies alone and seems to be more sensitive to nucleotide changes than in vitro RNA-binding studies8,26–28. While our study largely confirms the current concept of PPR-RNA recognition for P- and S-type PPRs, we additionally find that L-type repeats can also contribute to target recognition, at least when featuring typical residues in the crucial PPR positions 5 and L. On the other hand, we observe that RNA editing efficiency may be reduced upon conceptually improving target matches, offering a rationale for the mismatches observed for many natural editing factors and possibly indicating that RNA binding may not be too strong for efficient editing.

Single-target editing factor PPR65 seems more sensitive both to mutations in the protein and in its target sequence compared to dual-target editing factor PPR56 (Figs. 2 and 3), which is also characterized by many more off-targets in E. coli (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 1). Similarly, dual-target editing factor CLB19 in Arabidopsis thaliana previously revealed surprising tolerance against individual mutations in planta27. The numerous off-targets detected upon expression of the plant RNA editing factors provide a large set of welcome extra information on cytidine target recognition. The identified off-target sequences match the proposed PPR-RNA-binding code1 and reveal lesser contribution of N-terminal PPR repeats to recognition26 (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 1). The conservation of the editing site environment of the off-targets, particulary in the case of PPR65 (Fig. 5), strongly suggest nucleotide preferences also for positions directly upstream of the editing site26. These data will be particularly helpful to elucidate the selectivity of the E1, E2, and the DYW domains for target selection in the immediate editing site environment and ideally also for understanding a likely cooperativity between individual matches, which evidently do not simply sum up as a series of individual PPR-RNA nucleotide interactions.

The new and simple bacterial system will prove valuable for further characterization of the DYW-type RNA editing machinery, most notably so also for species currently not established as genetically accessible models29. The outcome of such studies will also reveal whether pyrimidine RNA editing based on PLS-type PPR proteins can be efficiently engineered to direct editing to desired sites, similar to previous approaches for tailoring of P-type PPRs for RNA binding30,31.

Methods

Cloning and expression of MBP-DYW-PPR proteins and targets

Gateway Destination vector pETG_41K (EMBL, Heidelberg, Germany, http://www.EMBL.de) was modified to obtain pET41Kmod by creating a multiple cloning site (SwaI, HindIII, AscI, Bsp119I) in the former XhoI restriction site downstream of the gateway cassette. Protein coding sequences lacking most of the N-terminal targeting sequences were amplified with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, https://www.thermofisher.com) and introduced into the Gateway pDONR/Zeo Entry vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Plasmid clones were used as template for mutagenesis with appropriate primers in rolling-circle PCRs32. Protein coding regions were transferred into pET41Kmod by Gateway cloning (Invitrogen, http://www.invitrogen.com) to create MBP fusion proteins (see Fig. 1).

RNA editing target sequences (including at least 33 bp upstream and 5 bp downstream of the editing site) flanked by appropriate restriction sites were generated by primer annealing. Twenty microliters of a mixture of 50 mM forward and reverse primer each was heated to 95 °C for 5 min and left to cool down to 40 °C. The double-stranded product was phosphorylated (T4 Polynucleotide Kinase, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and inserted into the dephosphorylated (FastAP, Thermo Fisher Scientific) pET41Kmod vector or the respective plasmid clones of editing factors. Constructs containing editing factors and downstream targets (Supplementary Data 4 and 5) were introduced into Rosetta 2 (DE3) cells (Novagen, http://www.merkmillipore.de).

For subsequent protein expression and RNA editing assays, 5 mL E. coli starter cultures (Luria Broth with 50 µM kanamycin and 17 µM chloramphenicol) were grown overnight. 250 µL of the pre-culture were used to inoculate 25 mL of the same media supplemented with 0.4 mM ZnSO4 in 100 ml Erlenmeyer flasks with baffles. Cultures were grown at 37 °C until an OD600 of 0.4–0.6 was reached. Cultures were cooled on ice for a minimum of 5 min before adding 0.4 mM IPTG for induction of construct expression. Cells were incubated at 16 °C and 180 rpm for 20 h before harvesting 1.5 mL samples. Shorter incubation times after induction of expression were applied test wise in selected experiments (Supplementary Data 1, Fig. 4). Samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further use. Protein expression was routinely checked on denaturing sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3) and RNA editing was only analyzed when protein was clearly detectable.

Detection of RNA editing in E. coli

To check for RNA editing in E. coli, complete RNA was extracted from 109 cells using a kit system (Macherey and Nagel, http://www.mn-net.com) with the recommended option of a pre-incubation with lysozyme (AppliChem, https://www.applichem.com). RNA was treated with DNaseI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using random hexanucleotide primers (6.4 µM per assay, Carl Roth, https://www.carlroth.com). A reverse primer upstream of the T7 terminator stem-loop sequence and a forward primer binding in the PPR protein coding region were used for reverse transcription-PCR amplification. PCR amplification assays contained 1 µL template of cDNA, 0.4 µM of each primer, 1× recommended PCR buffer, 0.8 mM dNTPs, 1U GoTaq polymerase (Promega, http://www.promega.com), and double-distilled water in a final volume of 25 µL. Amplification assays included 5 min initial denaturation at 94 °C followed by 35 cycles each with 30 s denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s annealing at 52 °C, 2.30 min synthesis at 72 °C, and a final step of synthesis for 5 min at 72 °C. Oligonucleotides are listed in Supplementary Data 6.

PCR products were gel-purified (Macherey and Nagel) and sequenced directly (Macrogen, https://dna.macrogen.com). Sequencing chromatograms were analyzed with MEGA 7 and Bioedit 7.133,34 (Supplementary Data 8). RNA editing was quantified as the ratio of the resulting thymidine peak to the sum of the thymidine and cytidine peak heights at the respective editing site. Experiments were repeated with independent primary clones at least once when no editing was detected. Upon initial detection of RNA editing, at least a third independent clone was investigated given the observed variability among experiments (Supplementary Data 1). Editing values are accordingly given as the mean of at least three replicates with standard deviations as indicated in Figs. 2 and 3 and Supplementary Data 1. Designation of RNA editing sites and PPRs is according to previously suggested nomenclature proposals35,36 (see Figs. 1–3). RNA structure prediction was performed using RNAfold WebServer (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at//cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/RNAfold.cgi) with the default settings and the temperature of 16 °C.

RNA-seq analysis and off-target identification

To identify off-targets in the E. coli transcriptomes after expressing PPR56 or PPR65, respectively, total RNA was prepared as described above in two independent experiments each. Library preparation (rRNA-depleted) and Illumina sequencing (150 bp paired-end) was done by Novogene (https://en.novogene.com/).

To identify candidate sites of C-to-U editing, transcriptome reads were aligned against the E. coli BL21 genome (CP010816.1) in parallel with genomic DNA reads (SRX326827: SRR941832) using GSNAP37 v. 2017-11-15 with proposed settings38. RNA − DNA differences to the E. coli reference genome were called using JACUSA39. In parallel, the RNA-seq data were mapped against the pET41Kmod vector sequence with the respective PPR protein and the editing target included. For a strict identification of RNA editing sites, U vs. C or A vs. G differences in RNA vs. DNA, reads were considered only when: not filter-flagged (B, H, M, or Y) in the JACUSA output, detected in the RNA-seq data of both technical replicates, not present in RNA-seq reads of wild-type BL21 DE3 included as a control (SRX4183661: SRR7280082) or of the respective other PPR clone, and at sites showing clean DNA background (C or G > 98%) and RNA reads (T + C or G + A > 98%). The level of RNA editing was defined as the ratio of altered to total RNA reads subtracted by the same quotient for the corresponding DNA reads (nearly always zero) at each site. The original transcript mapping data are available as separate Excel sheets as Supplementary Data 7 (7-1 to 7-5).

Reporting summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

Work on RNA editing is supported by a grant of the German Research Foundation (DFG grant number SCHA1952/2-1) to M.S.-R. We are grateful for the experimental work of students in our 2018 TRPL lab course and of Ms. Lin Zi during an internship in our group, for the technical assistance of Lisa Reinmuth and Sarah Brenner, and to Philipp Gerke for preparing a computational pipeline for RNA editing site detection and his help with bioinformatic issues.

Author contributions

This study was conceived and supervised by V.K. and M.S.-R. V.K. had the idea to introduce editing in E. coli. M.S.-R. created the initial setup to successfully introduce C-to-U editing into E. coli. B.O. conducted the initial experiments. B.O., Y.Y., V.K. and M.S.-R. optimized the setup and designed individual experiments. B.O., Y.Y., E.L. and M.S.-R. prepared the constructs, B.O., Y.Y. and E.L. ran E. coli experiments and Y.Y. and E.L. performed the protein studies. B.O., Y.Y., V.K. and M.S.-R. analyzed the data. V.K. and M.S.-R. drafted the manuscript and prepared the figures with contribution from all co-authors.

Data availability

RNA-seq data generated in this study were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the Bioproject PRJNA508474. Sanger sequence chromatograms used to score editing efficiencies are available as Supplementary Data 8.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Volker Knoop, Email: volker.knoop@uni-bonn.de.

Mareike Schallenberg-Rüdinger, Email: mrueding@uni-bonn.de.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s42003-019-0328-3.

References

- 1.Barkan A, Small I. Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014;65:415–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oldenkott B, Yamaguchi K, Tsuji-Tsukinoki S, Knie N, Knoop V. Chloroplast RNA editing going extreme: more than 3400 events of C-to-U editing in the chloroplast transcriptome of the lycophyte Selaginella uncinata. RNA. 2014;20:1499–1506. doi: 10.1261/rna.045575.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng S, et al. Redefining the structural motifs that determine RNA binding and RNA editing by pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in land plants. Plant J. 2016;85:532–547. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotera E, Tasaka M, Shikanai T. A pentatricopeptide repeat protein is essential for RNA editing in chloroplasts. Nature. 2005;433:326–330. doi: 10.1038/nature03229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun, T., Bentolila, S. & Hanson, M. R. The unexpected diversity of plant organelle RNA editosomes. Trends Plant Sci. 21, 962–973 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Takenaka M, et al. Multiple organellar RNA editing factor (MORF) family proteins are required for RNA editing in mitochondria and plastids of plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:5104–5109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202452109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bentolila S, et al. RIP1, a member of an Arabidopsis protein family, interacts with the protein RARE1 and broadly affects RNA editing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E1453–E1461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121465109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schallenberg-Rüdinger M, Kindgren P, Zehrmann A, Small I, Knoop V. A DYW-protein knockout in Physcomitrella affects two closely spaced mitochondrial editing sites and causes a severe developmental phenotype. Plant J. 2013;76:420–432. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichinose M, Uchida M, Sugita M. Identification of a pentatricopeptide repeat RNA editing factor in Physcomitrella patens chloroplasts. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:4060–4064. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schallenberg-Rüdinger, M. & Knoop, V. in Genomes and Evolution of Charophytes, Bryophytes and Ferns (ed. Rensing, S. A.) Vol. 78, 37–93 (2016).

- 11.Salone V, et al. A hypothesis on the identification of the editing enzyme in plant organelles. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:4132–4138. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyer LM, Zhang D, Rogozin IB, Aravind L. Evolution of the deaminase fold and multiple origins of eukaryotic editing and mutagenic nucleic acid deaminases from bacterial toxin systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:9473–9497. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boussardon C, et al. The cytidine deaminase signature HxE(x)nCxxC of DYW1 binds zinc and is necessary for RNA editing of ndhD-1. New Phytol. 2014;203:1090–1095. doi: 10.1111/nph.12928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayes ML, Dang KN, Diaz MF, Mulligan RM. A conserved glutamate residue in the C-terminal deaminase domain of pentatricopeptide repeat proteins is required for RNA editing activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:10136–101342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.631630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rüdinger M, Volkmar U, Lenz H, Groth-Malonek M, Knoop V. Nuclear DYW-type PPR gene families diversify with increasing RNA editing frequencies in liverwort and moss mitochondria. J. Mol. Evol. 2012;74:37–51. doi: 10.1007/s00239-012-9486-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagoner JA, Sun T, Lin L, Hanson MR. Cytidine deaminase motifs within the DYW domain of two pentatricopeptide repeat-containing proteins are required for site-specific chloroplast RNA editing. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:2957–2968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.622084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura T, Sugita M. A conserved DYW domain of the pentatricopeptide repeat protein possesses a novel endoribonuclease activity. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:4163–4168. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okuda K, et al. Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins with the DYW motif have distinct molecular functions in RNA editing and RNA cleavage in Arabidopsis chloroplasts. Plant Cell. 2009;21:146–156. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ichinose M, Sugita M. The DYW domains of pentatricopeptide repeat RNA editing factors contribute to discriminate target and non-target editing sites. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59:1652–1659. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rüdinger M, Funk HT, Rensing SA, Maier UG, Knoop V. RNA editing: only eleven sites are present in the Physcomitrella patens mitochondrial transcriptome and a universal nomenclature proposal. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2009;281:473–481. doi: 10.1007/s00438-009-0424-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohtani S, et al. Targeted gene disruption identifies three PPR-DYW proteins involved in RNA editing for five editing sites of the moss mitochondrial transcripts. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:1942–1949. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorenz R, et al. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 2011;6:26. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guillaumot D, et al. Two interacting PPR proteins are major Arabidopsis editing factors in plastid and mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:8877–8882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705780114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diaz MF, Bentolila S, Hayes ML, Hanson MR, Mulligan RM. A protein with an unusually short PPR domain, MEF8, affects editing at over 60 Arabidopsis mitochondrial C targets of RNA editing. Plant J. 2017;92:638–649. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrés-Colás N, et al. Multiple PPR protein interactions are involved in the RNA editing system in Arabidopsis mitochondria and plastids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:8883–8888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705815114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okuda K, et al. Quantitative analysis of motifs contributing to the interaction between PLS-subfamily members and their target RNA sequences in plastid RNA editing. Plant J. 2014;80:870–882. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kindgren P, Yap A, Bond CS, Small I. Predictable alteration of sequence recognition by RNA editing factors from Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2015;27:403–416. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.134189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramos-Vega M, et al. Functional analysis of the Arabidopsis thaliana chloroplast biogenesis 19 pentatricopeptide repeat editing protein. New Phytol. 2015;208:430–441. doi: 10.1111/nph.13468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schallenberg-Rüdinger M, Lenz H, Polsakiewicz M, Gott JM, Knoop V. A survey of PPR proteins identifies DYW domains like those of land plant RNA editing factors in diverse eukaryotes. RNA Biol. 2013;10:1549–1556. doi: 10.4161/rna.25755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coquille S, et al. An artificial PPR scaffold for programmable RNA recognition. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5729. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miranda RG, McDermott JJ, Barkan A. RNA-binding specificity landscapes of designer pentatricopeptide repeat proteins elucidate principles of PPR–RNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:2613–2623. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laible, M. & Boonrod, K. Homemade site directed mutagenesis of whole plasmids. J. Vis. Exp.11, 1135 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol.33, 1870–1874 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Hall, T. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser.41, 95–98 (1999).

- 35.Lenz, H. et al. Introducing the plant RNA editing prediction and analysis computer tool PREPACT and an update on RNA editing site nomenclature. Curr. Genet.56, 189–201 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Hein, A. & Knoop, V. Expected and unexpected evolution of plant RNA editing factors CLB19, CRR28 and RARE1: retention of CLB19 despite a phylogenetically deep loss of its two known editing targets in Poaceae. BMC Evol. Biol.18, 85 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Wu, T. D., Reeder, J., Lawrence, M., Becker, G. & Brauer, M. J. GMAP and GSNAP for Genomic Sequence Alignment: Enhancements to Speed, Accuracy, and Functionality. in Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 1418, 283–334 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Picardi, E. & Pesole, G. REDItools: high-throughput RNA editing detection made easy. Bioinformatics29, 1813–1814 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Piechotta, M., Wyler, E., Ohler, U., Landthaler, M. & Dieterich, C. JACUSA: site-specific identification of RNA editing events from replicate sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics18, 7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq data generated in this study were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the Bioproject PRJNA508474. Sanger sequence chromatograms used to score editing efficiencies are available as Supplementary Data 8.