Abstract

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with limited coding potential, which have emerged as novel regulators in many biological and pathological processes, including growth, development, and oncogenesis. Accumulating evidence suggests that lncRNAs have a special role in the osteogenic differentiation of various types of cell, including stem cells from different sources such as embryo, bone marrow, adipose tissue and periodontal ligaments, and induced pluripotent stem cells. Involved in complex mechanisms, lncRNAs regulate osteogenic markers and key regulators and pathways in osteogenic differentiation. In this review, we provide insights into the functions and molecular mechanisms of lncRNAs in osteogenesis and highlight their emerging roles and clinical value in regenerative medicine and osteogenesis-related diseases.

Cite this article: J. Zhang, X. Hao, M. Yin, T. Xu, F. Guo. Long non-coding RNA in osteogenesis: A new world to be explored. Bone Joint Res 2019;8:73–80. DOI: 10.1302/2046-3758.82.BJR-2018-0074.R1.

Keywords: lncRNA, Molecular mechanism, Osteogenesis, Osteogenic differentiation

Article focus

Accumulating evidence highlights the significant roles of lncRNAs in osteogenesis.

The detailed mechanisms of lncRNAs in osteogenesis remain to be elucidated.

This systematic review summarizes the roles and molecular mechanisms of osteogenesis-related lncRNAs, identifies limitations of current research, and offers future research directions.

Key messages

High-throughput technologies have been applied to identify critical osteogenesis-related lncRNAs.

lncRNAs regulate osteogenic markers or key regulators and pathways in complex mechanisms to participate in osteogenesis.

Most studies have focused on the crosstalk between lncRNAs and microRNA, providing insights into the mechanism by which non-coding RNA coordinate to regulate the osteogenesis, and few have focused on the subcellular localization of lncRNAs and discussed the possibility of the competing mode of regulation.

Introduction

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with a low coding potential.1-3 However, a subset of lncRNAs longer than 10 000 nucleotides contain small open reading frames that undergo active translation,4 redefining lncRNA. Although the precise roles of the most lncRNAs are still under investigation,5 they have been identified as the essential regulators in many biological and pathological processes, such as growth, development, and oncogenesis.6-10 IncRNAs participate in these processes by regulating gene expression patterns at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level.11-13

Accumulating evidence has provided insights into the major roles of lncRNAs in osteogenesis. A growing number of lncRNAs, including H19,14 DANCR,15 MALAT1,16 MEG3,17 and HOTAIR,18 have been identified as differentially expressed in osteogenesis and further confirmed to regulate osteogenic markers or key regulators and pathways in osteogenic differentiation, such as the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway.19-21 The mechanisms of competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) during osteogenic processes have been expounded, and a connection between lncRNAs and microRNAs (miRNAs) which has been widely observed in osteogenesis,14,18,22-24 has been identified. Moreover, lncRNAs serve as scaffolds or guides to modulate the function of key regulators, such as EZH224 and FOXO1.15 The present review summarizes the current evidence of the differential expression and molecular mechanisms of lncRNAs and provides insights into their roles in osteogenesis. An overview of IncRNAs and their roles in osteogenesis is provided in Table I and Fig. 1.8,14-19,21-24,25-49

Table I.

Overview of lncRNAs and their roles in osteogenesis

| Name | Cell type | Expression* | Functional role | Related molecules | Related pathways | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H19 | hMSC/mMSC/MC3T3-E1/UMR10 | Upregulation | Promotion | miR-675/TGF-β1/Smad3/HDAC; miR-675-5p /miR-141/miR-22; OPN; DKK4; miR-449a/miR-449b/miR-107/miR-106/miR-125a/miR27b/miR-34a/miR-17; miR-141/miR-22; miR-675/NOMO1; miR-138/FAK | Wnt/β-catenin signalling | 14,19,22,23,26-28 |

| DANCR | MSC/hBMSC/ hDTSC†/ hFOB1.19 | Downregulation | Inhibition | EZH2/Runx2; p-GSK-3β/β-catenin; FOXO1/SKP2; Runx2; p38 | Wnt/β-catenin signalling; MAPK signalling | 15,25,29-32 |

| MEG3 | hMSC/hBMSC/hASC | ND | Controversy | SOX2/BMP4/OSX/OCN; miR-140-5p; miR-133a-3p/SLC39A1 | ND | 17,33,34 |

| HOTAIR | hBMSC/hAVIC | Downregulation | Inhibition | β-catenin/BMP1/BMP4/BMP6/BMPR6/COL1A1; miR-17-5p/Smad7/Runx2/COL1A1/ALP | Wnt/β-catenin signalling | 18,21 |

| MALAT1 | hFOB 1.19/hAVIC | Upregulation | Promotion | OPG; miR-204/Smad4 | ND | 16,35 |

| AK007000 | MC3T3-E1/C2C12/C3H10T1/2 | Upregulation | Promotion | BMP2 | ND | 36 |

| AK089560 | C3H10T1/2 | Downregulation | ND | Sema3a | ND | 37 |

| AK138929 | MC3T3-E1 | Downregulation | Inhibition | miR-489-3p/PTPN6 | ND | 38 |

| AK141205 | rBMSC | Upregulation | Promotion | OPG/CXCL13/H4 histone | ND | 39 |

| AK028326 | hBMSC | ND | Promotion | CXCL13 | ND | 40 |

| MIR31HG | hASC | ND | Inhibition | NF-κB/p65/IκB-α | NF-κB signalling | 41 |

| NONHSAT009968 | hBMSC | ND | Inhibition | ND | ND | 42 |

| POIR | hPDLSC | ND | Promotion | miR-182/FOXO1/TCF-4/β-catenin | Wnt/β-catenin signalling | 43 |

| HCG18 | NPC | ND | Promotion | miR-146a-5p/TARF6/NFκB | NFκB signalling | 44 |

| HOXA-AS3 | mMSC | No change | Inhibition | EZH2/Runx2/H3K27me3 | ND | 45 |

| lncRUNX2-AS1 | hBMSC | ND | Inhibition | Runx2 | ND | 46 |

| MIAT | hASC | Downregulation | Inhibition | ND | ND | 8 |

| MODR | MSMSC | Upregulation | Promotion | miR-454 | ND | 47 |

| HIF1A-AS2 | hPDLSC | ND | Inhibition | ND | ND | 48 |

| TUG1 | hAVIC | ND | Promotion | miR-204-5p/Runx2 | ND | 24 |

| TCONS_00041960 | rBMSC | ND | Promotion | Glucocorticoid/miR-204-5p/miR-125a-3p/Runx2/GILZ | ND | 49 |

lncRNA expression during osteogenic differentiation

hDTSC, human dental tissue-derived stem cell, including human periodontal ligament stem cell (hPDLSC), human dental stem pulp cell (hDPSC), and human stem cell from the apical papilla (hSCAP).

MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; hMSC, human mesenchymal stem cell; mMSC, mouse mesenchymal stem cell; rMSC, rat mesenchymal stem cell; hBMSC, human marrow mesenchymal stem cell; rBMSC, rat marrow mesenchymal stem cell; hASC, human adipose-derived stem cell; hAVIC, human aortic valve interstitial cell; NPC, nucleus pulposus cell; MSMSC, maxillary sinus membrane stem cell; ND, not determined.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the systematic review.

A total of 508 studies were identified by a literature search in Pubmed, Embase, and Web of Science, up to 27 February 2018. The combined search terms were: “osteogenesis” or “osteogenic” or “osteogenic differentiation” or “bone formation” or “osteoblast” or “MC3T3” and “long noncoding RNA” or “long non-coding RNA” or “lncRNA”. After excluding 424 irrelevant or duplicated studies by screening, 84 studies were further assessed using the following criteria: (1) research focus on screening for osteogenesis-related lncRNA; (2) research focus on the roles of lncRNA in osteogenesis; (3) not review articles; (4) full text available. Finally, 73 eligible studies involving 21 lncRNAs and eight types of cell, including mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) from various sources and species, dental tissue-derived stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells, were included in this systematic review (Table I, Fig. 1).

High-throughput technology, such as RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) and microarray profiling, has been applied to investigate the patterns of expression of lncRNA during osteogenic differentiation, and has successfully characterized various osteogenesis-related lncRNAs. Identification of functional lncRNAs in osteogenesis has mainly focused on types of MSC from various sources, including the embryo and bone marrow. For example, Zuo et al50 identified 116 differentially expressed lncRNAs in BMP2-treated C3H10T1/2 stem cells, among which 24 pairs of co-expressed lncRNAs and nearby mRNAs such as lincRNA0231-EGFR and MEG3-DLK1 were identified. Cheng et al51 identified 24 downregulated lncRNAs in BMP2-treated C3H10T1/2 stem cells, among which AK035085 was shown to inhibit osteogenic differentiation. In order to identify potential lncRNAs involved in osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hBMSCs), Luo et al52 screened for the lncRNAs near to osteogenesis-related genes Smurf1, MSX1, and BMP1, and identified promising regulators AK096529 and uc003ups, which may positively regulate Smurf-1. Meanwhile, Gordon et al53 identified 1912 annotated lncRNAs expressed during osteoblast differentiation of mouse MSCs, among which 198 lncRNAs were differentially expressed. The analysis, combined with chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing data, revealed that > 40% of the genomic loci of these lncRNAs were bound with Runx2, suggesting that many are potentially regulated by Runx2. In addition, Harris et al54 found that 3764 lncRNAs were differentially expressed during the differentiation of α-SMA-positive BMSCs into mineralizing osteoblasts-osteocytes, among which 745 intersected with H3K27ac active enhancers, indicating a set of candidate enhancer RNAs (eRNA) for osteoblast differentiation. Based on public RNA-Seq data, Song et al55 identified that the expression of 574 lncRNAs significantly altered during the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs. Of these, the IncRNAs TCONS_00046478, TCONS_00027225, and TCONS_00007697 may function in osteogenic differentiation by acting as miRNA precursors (e.g. miR-544, miR-601, miR-640, and miR-689) and regulating the expression of co-expressed genes (COL4A4, COL21A1, and WNT2). In lncRNA microarray analyses of hBMSCs, Wang et al56 identified 1206 lncRNAs that were differentially expressed during osteogenic differentiation, among which H19 and uc022axw.1 probably have important roles in osteogenesis. Xie et al57 found that 520 lncRNAs exhibited differential expression in osteogenically differentiated hBMSCs from patients with ankylosing spondylitis (ASMSCs), among which lnc-USP50-2, lnc-FRG2C-3, lnc-LIN54-1, and lnc-ZNF354A-1 may be involved in the mechanism leading to the imbalance between BMP2 and NOG that promotes the abnormal osteogenic differentiation of ASMSCs. Moreover, 339 differentially expressed lncRNAs were identified in hBMSCs co-cultured with human amnion-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hAMSCs), among which DANCR may participate in complex regulatory mechanisms of hAMSC-derived osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs.25 Zhang et al58 revealed six core regulators (NR_024031, XR_111050, FR148647, FR406817, FR401275, and FR374455) among 1408 differentially expressed lncRNAs of hBMSCs during osteogenic differentiation, of which XR_111050 promoted the osteogenic potential of hBMSCs. Finally, Qiu et al59 identified 433 upregulated and 232 downregulated lncRNAs in the osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs, among which ENST00000502125.2 may be a promising target to promote osteogenesis.

Some studies have investigated other types of cell, such as human periodontal ligament stem cells (hPDLSCs), human adipose-derived stem cells (hASCs), the mouse osteoblast cell line MC3T3-E1, and human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Qu et al found that 994 lncRNAs were upregulated and 1177 were downregulated in the osteogenic differentiation of hPDLSCs, among which 393 lncRNAs were closely related to osteogenesis-related mRNAs (ALP, BMP2, BMP5, BMP6, IL6, COL1A1, and COL1A2). Moreover, RP11-305L7.6, RP4-613B23.1, RP11-45A16.4, XLOC_002932, and AC078851.1 were recognized as key candidate lncRNAs. MEG3 was upregulated after osteogenic induction, indicative of its critical functions in the osteogenesis in hPDLSCs. Furthermore, AC078851.1 was negatively correlated with IL6, while TCONS_00007046 was positively correlated with BMP2 and ALP.60 Meanwhile, Gu et al61 confirmed that a total of 960 lncRNAs were differentially expressed during hPDLSC osteogenic differentiation. In particular, TCONS_00212979 and TCONS_00212984 might interact with miR-34a and miR-146a to modulate the osteogenic differentiation of hPDLSCs via the MAPK pathway. Furthermore, Hu et al62 identified 857 lncRNAs that were significantly altered during MC3T3-E1 osteoblast differentiation under simulated microgravity, as well as 132 pairs of lncRNA and nearby coding genes, among which NONMMUT044983-Ptbp2, NONMMUT023474-Ext1, and NONMMUT018832-Tnpo1 were screened for possible functions in osteoblast differentiation. Huang et al63 found that 1460 upregulated and 1112 downregulated lncRNAs in the osteogenic differentiation of hASCs, and constructed the lncRNA-mRNA co-expression network that included 12 lncRNAs and 157 mRNAs. Finally, Paik et al64 analyzed the transcriptome of iPSCs induced by BMP2 using RNA-Seq and identified that the lncRNA SNHG1 was upregulated in response to BMP2 among the 5566 differentially expressed transcripts, of which lncRNAs accounted for 4%.

lncRNAs in osteogenesis

The lncRNA H19 has been found to be one of the most abundant and conserved non-coding transcripts in mammalian development, which has profound effects on proliferation, differentiation, and carcinogenesis.65 Significant upregulation of H19 in osteogenesis was first proposed by Huang et al,26 and subsequently confirmed by other studies in osteoblasts and hBMSCs.22,27 These findings ignited academic interest in the role of H19 in osteogenesis.

Accumulating evidence has suggested a crucial role of H19 as a ceRNA. Huang et al26 proposed that H19 could promote the osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs through the miR-675/TGF-β1/Smad3/HDAC pathway (Fig. 2a) Meanwhile, Liang et al22 demonstrated that H19 promoted osteogenesis in vivo and in vitro, by functioning as a ceRNA to sponge miR-22 and miR-141, two negative regulators of osteogenesis targeting β-catenin, ultimately activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and enhancing osteogenesis (Fig. 2b). Moreover, the feedback loop between H19 and its encoded miR-675-5p may partially account for the regulation of osteoblast differentiation.22 Furthermore, Dong et al27 found that H19 was upregulated in 20(R)-ginsenoside Rh2 (Rh2)-treated MC3T3-E1, which increased the expression of osteopontin by inhibiting acetylation of histones H3 and H4 in its promoter to participate in Rh2-mediated proliferation. Huang et al26 showed that the silencing of H19 reduced the expression of osteogenesis-related genes in hASCs, including ALPL and Runx2.27 Li et al19 applied RNA-Seq to investigate the functions of H19 in disuse osteoporosis. Among 464 differentially expressed lncRNAs, H19 decreased with a fold-change of 2.86 in response to mechanical unloading, with related genes that were mainly involved in the Wnt signalling pathway. Knockdown of H19 upregulated Dkk4, which suppressed Wnt signalling and inhibited osteogenesis in UMR106 cells. These findings partially demonstrate the pivotal roles of H19 in osteoporosis of hindlimb-unloaded rats (Fig. 2b).19

The molecular mechanisms of H19 in osteogenesis. (a) H19 regulates osteogenesis-related genes. (b) H19 regulates the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway. (c) H19 regulates the MAPK signalling pathway.

Liao et al66 showed the dynamic changes in H19 during BMP9-induced osteogenesis of mouse MSCs, in which H19 was sharply upregulated during the early stage, followed by a rapid decrease and gradual return to basal levels, accompanied by expression changes of osteogenic markers. However, the well-coordinated biphasic expression of H19 may be critical in osteogenic differentiation, because either overexpression or silencing of H19 impaired osteogenesis by dysregulating Notch signalling-targeting miRNAs (Fig. 2c).66 Liang et al22 found that H19 activated the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by sponging miR-141 and miR-22, resulting in the potentiated expression of β-catenin and other osteogenic markers to promote osteogenesis in hBMSCs (Fig. 2b). Zhao et al23 demonstrated that the mutation of DLX3 interferes with bone formation partially through the H19/miR-675/NOMO1 axis in tricho-dento-osseous (TDO) syndrome. Finally, Wu et al14 showed that mechanical tension (10%, 0.5 Hz) could enhance osteogenic differentiation by increasing H19 expression in hBMSCs, which sponged miR-138, and increasing its target FAK (Fig. 2a).

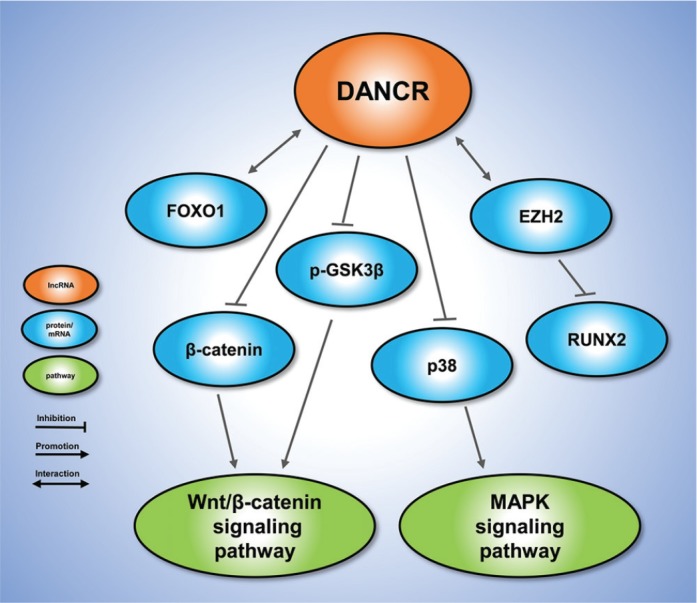

Differentiation antagonizing non-protein coding RNA (DANCR), previously called anti-differentiation non-coding RNA (ANCR), is a novel lncRNA downregulated during stem cell differentiation that maintains epidermal stem cells or osteoblast cells in an undifferentiated state.28 The upregulation of DANCR has been confirmed during osteogenesis in many cell types, including hFOB1.19 bone cells,29 hPDLSCs,30 human dental stem pulp cells (hDPSCs),20 human stem cells from the apical papilla (hSCAP)31 and, hBMSCs.32 For example, Zhu et al29 found that the downregulation of DANCR promoted osteoblast differentiation in hFOB1.19, whereas DANCR overexpression inhibited this process. In particular, DANCR suppressed the expression of Runx2 by physically interacting with EZH2 in Runx2 gene promoters, subsequently blocking osteoblast differentiation. Meanwhile, Jia et al30 showed that DANCR suppressed proliferation of hPDLSCs, which is promising for the use of dental tissue-derived stem cells (DTSCs) in tissue engineering. Downregulation of DANCR enhanced the osteogenic potential of hPDLSCs by promoting the Wnt signalling pathway and upregulating osteogenic markers. They also investigated the regulatory effects of DANCR on the proliferation and differentiation of two other types of DTSCs, hDPSCs, and hSCAPs. Although few effects on the proliferation of hDPSC and hSCAP were observed, the downregulation of DANCR promoted the osteogenic, adipogenic, and neurogenic differentiation of DTSCs (including hPDLSCs), indicating that DANCR is an important regulator of stem cell differentiation.31 In an integrated lncRNA profiling analysis of hDPSCs, a total of 139 lncRNAs were differentially expressed during hDPSC differentiation into odontoblast-like cells, among which DANCR was significantly downregulated in a time-dependent manner. The upregulation of DANCR significantly decreased the expression of p-GSK-3β and β-catenin to block mineralized nodule formation, suggesting that DANCR can suppress the Wnt/β-catenin pathway during the odontoblast-like differentiation of hDPSCs.20 Wang et al25 identified that DANCR was significantly decreased in the hBMSCs co-cultured with hAMSCs, and DANCR overexpression inhibited the enhanced osteogenic effect of hAMSCs on hBMSCs by suppressing Runx2 upregulation. In addition, Zhang et al32 found that DANCR was abnormally decreased in hBMSCs during osteogenic differentiation, and significantly inhibited the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs by suppressing p38 MAPK activation, rather than ERK1/2 or JNK MAPKs. Tang et al15 detected the expression of DANCR in clinical samples and MSCs to investigate its functions in osteolysis following total hip arthroplasty. In periprosthetic tissues, DANCR was upregulated while FOXO1 was downregulated. Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), a common adhesive agent used in arthroplasty, inhibited MSC osteogenesis via the DANCR/FOXO1 pathway. In this mechanism, PMMA increases the expression of DANCR, which binds to FOXO1 and promotes Skp2-mediated ubiquitination of FOXO1 to decrease its expression. (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3.

The molecular mechanisms of MEG3 in osteogenesis.

MEG3 is an important regulator involved in human development and various diseases.67-70 Accumulating evidence for the biological and clinical significance of MEG3 in osteogenesis has been highlighted in recent years. However, the role of MEG3 in osteogenesis remains controversial. Zhuang et al33 identified lower MEG3 expression in hBMSCs isolated from patients with multiple myeloma than in those from normal donors during osteogenic differentiation. MEG3 exhibited a critical transcriptional regulatory function by dissociating SOX2 from the BMP4 promoter, thereby relieving the suppression effect of SOX2 on BMP4. In addition, MEG3 positively regulates other key osteogenic markers, including Runx2, osterix, and osteocalcin (OCN).33 Similarly, Li et al71 found that MEG3, which was downregulated during adipogenesis and upregulated during osteogenesis in hASCs, regulated the balance of adipogenesis and osteogenesis in hASCs by suppressing miR-140-5p. Nevertheless, Wang et al17 found that both MEG3 and miR-133a-3p were increased in hBMSCs during postmenopausal osteoporosis. By contrast, the expression of MEG3 and miR-133a-3p was markedly decreased in the differentiation of hBMSCs into osteoblasts. MEG3 was confirmed to regulate positively miR-133a-3p which targets SLC39A1, thereby leading to the inhibition of osteogenesis in hBMSCs.17 Overall, the role of MEG3 in osteogenesis appears to differ substantially depending on the cell type and conditions (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The molecular mechanisms of DANCR in osteogenesis. DANCR regulates the Wnt/β-catenin signalling and MAPK signalling pathways.

The functional roles of HOTAIR in human cancers have been largely elucidated35,72-74 and its biological functions in other diseases and physiological processes have been partly clarified.75-78 Carrion et al21 reported that HOTAIR was mechanoresponsive to cyclic stretching in human aortic valve interstitial cells (hAVICs), and inhibited aortic valve calcification by elevating two osteogenic genes, ALPL and BMP2. Targeting HOTAIR, certain osteogenic genes such as BMP1, BMP4, BMP6, BMPR6, and COL1A1 were upregulated, and the differentially expressed genes were involved in ossification. In addition, Wei et al18 found higher HOTAIR levels in samples of non-traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head compared with osteoarthritis, which was negatively related to miR-17-5p. Meanwhile, decreasing in BMP2-induced osteoblastic differentiation, HOTAIR reduced the expression of osteogenic markers, including Runx2, COL1A1, and ALP by inhibiting miR-17-5p and promoting its target Smad7 in hBMSCs.18 These findings indicate its critical roles in osteogenic differentiation.

Several studies have examined the roles of MALAT1 in osteogenesis. Che et al35 first reported that MALAT1 regulated OPG expression in hFOB1.19 bone cells, although the relationship between MALAT1 and osteoblast differentiation was unclear. Subsequently, Xiao et al16 observed an elevated expression of MALAT1 in calcific valves and hAVICs during osteogenesis, where MALAT1 acted as a ceRNA to elevate Smad4 by sponging miR-204, thereby increasing the expression of osteoblast-specific markers, such as ALP and OCN, and promoting bone matrix formation in hAVICs.

Looking at others, Gao et al36 screened an upregulated lncRNA, AK007000, from microarray analyses of MC3T3-E1, C2C12, and C3H10T1/2 induced by BMP2, which was subsequently shown to be positively related to osteogenic differentiation markers. Meanwhile, Zuo et al37 found that AK089560 was decreased in both osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of C3H10T1/2 cells, which is transcribed from the intron of Sema3a and may regulate Sema3a expression to participate in the multidirectional differentiation of MSCs. In addition, Yin et al38 found that AK138929, a novel osteogenic regulator, inhibited osteoblast differentiation by targeting miR-489-3p and promoting PTPN6 in MC3T3-E1. Moreover, Li et al39 identified the lncRNA AK141205, which was upregulated in osteogenic growth peptide-induced osteogenesis, and promoted ALP activity, formation of calcium salt nodules, and osteogenic differentiation markers, suggesting its key regulatory role in osteogenesis. Further experiments indicated that AK141205 positively promoted CXCL13 expression via acetylation of histone H4 in its promoter region. Cao et al40 found that AK028326 was decreased during high glucose-induced inhibition of osteogenic differentiation in hBMSCs, which was further confirmed to positively regulate CXCL13 expression. In addition, high glucose suppressed the osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs via the reduction of CXCL13 expression mediated by AK028326.

Jin et al41 showed that knockdown of MIR31HG significantly promoted osteogenic differentiation, completely antagonizing inflammation-induced osteogenic inhibition. The MIR31HG-NFκB regulatory loop suppressed osteogenic differentiation of hASCs, in which p65 promoted MIR31HG expression by binding to the MIR31HG promoter, and MIR31HG directly interacted with IκB-α, in turn participating in NFκB activation. They also investigated the roles of myocardial infarction-associated transcript (MIAT) in the osteogenic differentiation of hASCs. MIAT, which was downregulated during osteogenesis of hASCs, suppressed osteogenic differentiation both in vitro and in vivo.8

Among 2033 differentially expressed lncRNAs in staphylococcal protein A (SpA)-treated hBMSCs, NONHSAT009968 was upregulated 3.8-fold, and was subsequently confirmed to participate in SpA-induced osteogenic suppression in hBMSCs.42 Meanwhile, POIR positively regulated osteogenic differentiation of hPDLSCs from patients with periodontitis (pPDLSCs) by acting as a ceRNA for miR-182, leading to de-repression of its target gene, FOXO1, which increased bone formation of pPDLSCs by competing with TCF-4 for β-catenin and inhibiting the canonical Wnt pathway.43 Xi et al44 found that HCG18 was upregulated in patients with degeneration of intervertebral discs and functioned as the miR-146a-5p sponge in nucleus pulposus cells, in which osteogenic differentiation was promoted via the miR-146a-5p/TARF6/NFκB axis. Zhu et al45 found that although HOXA-AS3 remained unchanged during osteogenic induction, knockdown of HOXA-AS3 expression promoted osteogenesis and the expression of osteogenic markers, including COL1A1, Runx2, SP7, BGLAP, SPP1, and IBSP. HOXA-AS3 was confirmed to bind to EZH2 and regulate the expression of Runx2 via H3K27me3. Xu et al46 reported a highly abundant lncRNA in MSCs from multiple myeloma, namely lncRUNX2-AS1, which could be packaged into exosomes and transferred to hBMSCs, inhibiting osteogenic differentiation by forming an RNA duplex with Runx2 and decreasing its stability. Weng et al47 reported that a gradually upregulated lncRNA during osteogenic differentiation, namely MODR, acted as a ceRNA to sponge miR-454, resulting in elevated Runx2 expression and promoting osteogenesis of maxillary sinus membrane stem cells. Chen et al48 revealed that HIF1A-AS2 had a negative effect on the osteogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament cells. Yu et al24 found that TUG1 positively regulated Runx2 expression by sponging miR-204-5p, subsequently enhancing osteogenic differentiation in calcific aortic valve disease. Finally, TCONS_00041960, identified as a downregulated lncRNA in the microarray analysis of rat glucocorticoid-treated BMSCs, promoted the expression of the osteogenic genes Runx2 and GILZ by sponging miR-204-5p and miR-125a-3p, leading to enhanced osteogenesis.49

In conclusion, osteogenesis is related to various biological or pathological processes, leading to growth, development, and disease. Although many studies have partially revealed the regulatory mechanisms of osteogenesis and explored the treatments of osteogenesis-related disease,79,80 it is still unsatisfactory. An increasing number of studies have confirmed the differential expression of lncRNAs during osteogenesis and revealed their roles and molecular mechanisms in vivo and in vitro. Most have focused on the crosstalk between lncRNAs and miRNAs, providing insights into non-coding RNA coordination to regulate osteogenesis. Some studies have proposed other mechanisms, such as physical binding to transcription factors and decaying target mRNA. Nevertheless, the detailed regulatory mechanisms of lncRNAs remain unclear. In particular, the mechanism by which ceRNA sponges miRNA and modulates other osteogenesis-related genes is essential, but incomplete, for lncRNAs. Moreover, few studies have focused on the subcellular localization of lncRNAs, which is indispensable for establishing the ceRNA regulation mode. For example, if a lncRNA was mainly located in the nucleus, the ceRNA would not be in the “critical” regulation mode, as proposed by some researchers. RNA-binding protein, as its name implies, should show promise to demonstrate the mechanisms of lncRNAs in osteogenic differentiation. Given that alternative splicing is remarkable in terms of differentiation and development, future investigations should focus on the different functions of various alternative transcripts in osteogenesis.

Footnotes

Author contributions: J. Zhang: Wrote and approved the final manuscript.

X. Hao: Study conception and literature search.

M. Yin: Study conception and literature search.

T. Xu: Wrote and approved the final manuscript.

F: Guo: Wrote and approved the final manuscript.

J. Zhang and X. Hao contributed equally to this work.

Follow us @BoneJointRes

Funding statement

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81772440, 81371915 and 81572094).

References

- 1. Zhao Y, Liu Y, Lin L, et al. The lncRNA MACC1-AS1 promotes gastric cancer cell metabolic plasticity via AMPK/Lin28 mediated mRNA stability of MACC1. Mol Cancer 2018;17:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lian Y, Ding J, Zhang Z, et al. The long noncoding RNA HOXA transcript at the distal tip promotes colorectal cancer growth partially via silencing of p21 expression. Tumour Biol 2016;37:7431-7440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang M, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, et al. LncRNA UCA1 promotes migration and invasion in pancreatic cancer cells via the Hippo pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta 2018;1864(5 Pt A):1770-1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Razooky BS, Obermayer B, O'May JB, Tarakhovsky A. Viral Infection Identifies Micropeptides Differentially Regulated in smORF-Containing lncRNAs. Genes 2017;8:E206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schlosser K, Hanson J, Villeneuve PJ, et al. Assessment of Circulating LncRNAs Under Physiologic and Pathologic Conditions in Humans Reveals Potential Limitations as Biomarkers. Sci Rep 2016;6:36596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen J, Guo J, Cui X, et al. The Long Noncoding RNA LnRPT Is Regulated by PDGF-BB and Modulates the Proliferation of Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2018;58:181-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ibeagha-Awemu EM, Do DN, Dudemaine PL, Fomenky BE, Bissonnette N. Integration of lncRNA and mRNA Transcriptome Analyses Reveals Genes and Pathways Potentially Involved in Calf Intestinal Growth and Development during the Early Weeks of Life. Genes 2018;9:E142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jin C, Zheng Y, Huang Y, et al. Long non-coding RNA MIAT knockdown promotes osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells. Cell Biol Int 2017;41:33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao J, Zhang W, Lin M, et al. MYOSLID Is a Novel Serum Response Factor-Dependent Long Noncoding RNA That Amplifies the Vascular Smooth Muscle Differentiation Program. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2016;36:2088-2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Standaert L, Adriaens C, Radaelli E, et al. The long noncoding RNA Neat1 is required for mammary gland development and lactation. RNA 2014;20:1844-1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang J, Liu SC, Luo XH, et al. Exosomal Long Noncoding RNAs are Differentially Expressed in the Cervicovaginal Lavage Samples of Cervical Cancer Patients. J Clin Lab Anal 2016;30:1116-1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xia T, Chen S, Jiang Z, et al. Long noncoding RNA FER1L4 suppresses cancer cell growth by acting as a competing endogenous RNA and regulating PTEN expression. Sci Rep 2015;5:13445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schmitt AM, Chang HY. Long Noncoding RNAs in Cancer Pathways. Cancer Cell 2016;29:452-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu J, Zhao J, Sun L, et al. Long non-coding RNA H19 mediates mechanical tension-induced osteogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via FAK by sponging miR-138. Bone 2018;108:62-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tang Z, Gong Z, Sun X. LncRNA DANCR involved osteolysis after total hip arthroplasty by regulating FOXO1 expression to inhibit osteoblast differentiation. J Biomed Sci 2018;25:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xiao X, Zhou T, Guo S, et al. LncRNA MALAT1 sponges miR-204 to promote osteoblast differentiation of human aortic valve interstitial cells through up-regulating Smad4. Int J Cardiol 2017;243:404-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang Q, Li Y, Zhang Y, et al. LncRNA MEG3 inhibited osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from postmenopausal osteoporosis by targeting miR-133a-3p. Biomed Pharmacother 2017;89:1178-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wei B, Wei W, Zhao B, Guo X, Liu S. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR inhibits miR-17-5p to regulate osteogenic differentiation and proliferation in non-traumatic osteonecrosis of femoral head. PLoS One 2017;12:e0169097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li B, Liu J, Zhao J, et al. LncRNA-H19 Modulates Wnt/β-catenin Signaling by Targeting Dkk4 in Hindlimb Unloaded Rat. Orthop Surg 2017;9:319-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen L, Song Z, Huang S, et al. lncRNA DANCR suppresses odontoblast-like differentiation of human dental pulp cells by inhibiting wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cell Tissue Res 2016;364:309-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carrion K, Dyo J, Patel V, et al. The long non-coding HOTAIR is modulated by cyclic stretch and WNT/β-CATENIN in human aortic valve cells and is a novel repressor of calcification genes. PLoS One 2014;9:e96577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liang WC, Fu WM, Wang YB, et al. H19 activates Wnt signaling and promotes osteoblast differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Sci Rep 2016;6:20121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhao N, Zeng L, Liu Y, et al. DLX3 promotes bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell proliferation through H19/miR-675 axis. Clin Sci 2017;131:2721-2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yu C, Li L, Xie F, et al. LncRNA TUG1 sponges miR-204-5p to promote osteoblast differentiation through upregulating Runx2 in aortic valve calcification. Cardiovasc Res 2018;114:168-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang J, Miao J, Meng X, Chen N, Wang Y. Expression of long non-coding RNAs in human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells co-cultured with human amnion-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Med Rep 2017;16:6683-6689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang Y, Zheng Y, Jia L, Li W. Long Noncoding RNA H19 Promotes Osteoblast Differentiation Via TGF-beta1/Smad3/HDAC Signaling Pathway by Deriving miR-675. Stem Cells 2015;33:3481-3492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dong B, Pang TT. LncRNA H19 contributes to Rh2-mediated MC3T3-E1cell proliferation by regulation of osteopontin. Cell Mol Biol 2017;63:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kretz M, Webster DE, Flockhart RJ, et al. Suppression of progenitor differentiation requires the long noncoding RNA ANCR. Genes Dev 2012;26:338-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhu L, Xu PC. Downregulated LncRNA-ANCR promotes osteoblast differentiation by targeting EZH2 and regulating Runx2 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013;432:612-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jia Q, Jiang W, Ni L. Down-regulated non-coding RNA (lncRNA-ANCR) promotes osteogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells. Arch Oral Biol 2015;60:234-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jia Q, Chen X, Jiang W, et al. The Regulatory Effects of Long Noncoding RNA-ANCR on Dental Tissue-Derived Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int 2016;2016:3146805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang J, Tao Z, Wang Y. Long noncoding RNA DANCR regulates the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human bone-derived marrow mesenchymal stem cells via the p38 MAPK pathway. Int J Mol Med 2018;41:213-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhuang W, Ge X, Yang S, et al. Upregulation of lncRNA MEG3 Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells From Multiple Myeloma Patients By Targeting BMP4 Transcription. Stem Cells 2015;33:1985-1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhao W, Geng D, Li S, Chen Z, Sun M. LncRNA HOTAIR influences cell growth, migration, invasion, and apoptosis via the miR-20a-5p/HMGA2 axis in breast cancer. Cancer Med 2018;7:842-855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 35. Che W, Dong Y, Quan HB. RANKL inhibits cell proliferation by regulating MALAT1 expression in a human osteoblastic cell line hFOB 1.19. Cell Mol Biol 2015;61:7-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gao Y, Cheng C, Li J, et al. Osteogenic differentiation induced by bone morphogenetic protein 2 and long non-coding RNA AK007000. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research 2014;18:2297-2302. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zuo CQ, Lu HY, Zhong YC, et al. The expression of long non-coding RNA AK089560 in mesenchymal stem cells undergoing osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research 2014;18:3732-3738. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yin C, Zhang Y, Yan K, et al. A novel osteoblast differentiation inhibiting LNCRNA, AK138929 [abstract]. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research Conference 2016;31(Suppl 1). [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li H, Zhang Z, Chen Z, Zhang D. Osteogenic growth peptide promotes osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells mediated by LncRNA AK141205-induced upregulation of CXCL13. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015;466:82-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cao B, Liu N, Wang W. High glucose prevents osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells via lncRNA AK028326/CXCL13 pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 2016;84:544-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jin C, Jia L, Huang Y, et al. Inhibition of lncRNA MIR31HG Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells. Stem Cells 2016;34:2707-2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cui Y, Lu S, Tan H, et al. Silencing of Long Non-Coding RNA NONHSAT009968 Ameliorates the Staphylococcal Protein A-Inhibited Osteogenic Differentiation in Human Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 2016;39:1347-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang L, Wu F, Song Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA related to periodontitis interacts with miR-182 to upregulate osteogenic differentiation in periodontal mesenchymal stem cells of periodontitis patients. Cell Death Dis 2016;7:e2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xi Y, Jiang T, Wang W, et al. Long non-coding HCG18 promotes intervertebral disc degeneration by sponging miR-146a-5p and regulating TRAF6 expression. Sci Rep 2017;7:13234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhu XX, Yan YW, Chen D, et al. Long non-coding RNA HoxA-AS3 interacts with EZH2 to regulate lineage commitment of mesenchymal stem cells. Oncotarget 2016;7:63561-63570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xu H, Qian C, Shi J, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of lncRUNX2-AS1 from multiple myeloma cells to mesenchymal stem cells contributes to osteogenic differentiation. Blood Conference: 59th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, ASH 2017;130(Suppl 1). [Google Scholar]

- 47. Weng J, Peng W, Zhu S, Chen S. Long Noncoding RNA Sponges miR-454 to Promote Osteogenic Differentiation in Maxillary Sinus Membrane Stem Cells. Implant Dent 2017;26:178-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen D, Wu L, Liu L, et al. Comparison of HIF1A-AS1 and HIF1A-AS2 in regulating HIF-1α and the osteogenic differentiation of PDLCs under hypoxia. Int J Mol Med 2017;40:1529-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shang G, Wang Y, Xu Y, et al. Long non-coding RNA TCONS_00041960 enhances osteogenesis and inhibits adipogenesis of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell by targeting miR-204-5p and miR-125a-3p. J Cell Physiol 2018;233:6041-6051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zuo C, Wang Z, Lu H, et al. Expression profiling of lncRNAs in C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal stem cells undergoing early osteoblast differentiation. Mol Med Rep 2013;8:463-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cheng C, Gao Y, Li J, Pan QH. Role of long non-coding RNA in osteoblast differentiation of C3H10T1/2 cells induced by bone morphogenetic protein-2. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research 2014;18:3223-3229. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Luo J, Huang L, Liu H, et al. Screening and Primary Identification of lncRNA Involved in Osteogenic Differentiation of hMSC. Journal of Sun Yat-sen University Medical Sciences 2014;35:230-236. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gordon J, Wu H, Stein J, Lian J, Stein G. Discovery of long noncoding RNAs during osteoblast differentiation of pluripotent mesenchymal stromal cells [abstract]. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research Conference 2015;30(Suppl 1). [Google Scholar]

- 54. Harris MA, Tye C, Kalajzic I, Gordon J, Lian J, Stein G. Candidate enhancer RNA expression during aSMA+ progenitor to mineralizing osteoblasts-osteocytes: Exploration of the 'Dark Matter' of the Genome [abstract]. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research Conference 2015;30(Suppl 1). [Google Scholar]

- 55. Song WQ, Gu WQ, Qian YB, et al. Identification of long non-coding RNA involved in osteogenic differentiation from mesenchymal stem cells using RNA-Seq data. Genet Mol Res 2015;14:18268-18279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang L, Wang Y, Li Z, Li Z, Yu B. Differential expression of long noncoding ribonucleic acids during osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Int Orthop 2015;39:1013-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xie Z, Li J, Wang P, et al. Differential Expression Profiles of Long Noncoding RNA and mRNA of Osteogenically Differentiated Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Ankylosing Spondylitis. J Rheumatol 2016;43:1523-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang W, Dong R, Diao S, et al. Differential long noncoding RNA/mRNA expression profiling and functional network analysis during osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017;8:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Qiu X, Jia B, Sun X, et al. The Critical Role of Long Noncoding RNA in Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells. BioMed Res Int 2017;2017:5045827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Qu Q, Fang F, Wu B, et al. Potential Role of Long Non-Coding RNA in Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells. J Periodontol 2016;87:e127-e137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gu X, Li M, Jin Y, Liu D, Wei F. Identification and integrated analysis of differentially expressed lncRNAs and circRNAs reveal the potential ceRNA networks during PDLSC osteogenic differentiation. BMC Genet 2017;18:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hu Z, Wang H, Wang Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis and prediction of functional long noncoding RNAs in osteoblast differentiation under simulated microgravity. Mol Med Rep 2017;16:8180-8188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Huang G, Kang Y, Huang Z, et al. Identification and Characterization of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017;42:1037-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Paik KJ, Qu K, Hsueh B, et al. Abstract 158: Identification of BMP-Responsive Long Noncoding RNAs in Pluripotent Cells. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;133(Suppl):174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Huang Y, Zheng Y, Jin C, et al. Long Non-coding RNA H19 Inhibits Adipocyte Differentiation of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells through Epigenetic Modulation of Histone Deacetylases. Sci Rep 2016;6:28897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liao J, Yu X, Hu X, et al. lncRNA H19 mediates BMP9-induced osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) through Notch signaling. Oncotarget 2017;8:53581-53601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Liu W, Liu X, Luo M, et al. dNK derived IFN-γ mediates VSMC migration and apoptosis via the induction of LncRNA MEG3: A role in uterovascular transformation. Placenta 2017;50:32-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhou Y, Zhang X, Klibanski A. MEG3 noncoding RNA: a tumor suppressor. J Mol Endocrinol 2012;48:R45-R53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Piccoli MT, Gupta SK, Viereck J, et al. Inhibition of the Cardiac Fibroblast-Enriched lncRNA Meg3 Prevents Cardiac Fibrosis and Diastolic Dysfunction. Circ Res 2017;121:575-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kameswaran V, Bramswig NC, McKenna LB, et al. Epigenetic regulation of the DLK1-MEG3 microRNA cluster in human type 2 diabetic islets. Cell Metab 2014;19:135-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Li Z, Jin C, Chen S, et al. Long non-coding RNA MEG3 inhibits adipogenesis and promotes osteogenesis of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells via miR-140-5p. Mol Cell Biochem 2017;433:51-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yang Y, Jiang C, Yang Y, et al. Silencing of LncRNA-HOTAIR decreases drug resistance of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer cells by inactivating autophagy via suppressing the phosphorylation of ULK1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018;497:1003-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Liu S, Lei H, Luo F, Li Y, Xie L. The effect of lncRNA HOTAIR on chemoresistance of ovarian cancer through regulation of HOXA7. Biol Chem 2018;399:485-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Xue M, Chen LY, Wang WJ, et al. HOTAIR induces the ubiquitination of Runx3 by interacting with Mex3b and enhances the invasion of gastric cancer cells. Gastric Cancer 2018;21:756-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zhang C, Wang P, Jiang P, et al. Upregulation of lncRNA HOTAIR contributes to IL-1β-induced MMP overexpression and chondrocytes apoptosis in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Gene 2016;586:248-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zhang HJ, Wei QF, Wang SJ, et al. LncRNA HOTAIR alleviates rheumatoid arthritis by targeting miR-138 and inactivating NF-κB pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 2017;50:283-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Guo X, Chang Q, Pei H, et al. Long Non-coding RNA-mRNA Correlation Analysis Reveals the Potential Role of HOTAIR in Pathogenesis of Sporadic Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2017;54:303-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Peng Y, Meng K, Jiang L, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-induced HOTAIR activation promotes endothelial cell proliferation and migration in atherosclerosis. Biosci Rep 2017;37:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rohilla R, Wadhwani J, Devgan A, Singh R, Khanna M. Prospective randomised comparison of ring versus rail fixator in infected gap nonunion of tibia treated with distraction osteogenesis. Bone Joint J 2016;98-B:1399-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Simpson AH, Keenan G, Nayagam S, et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound does not influence bone healing by distraction osteogenesis: a multicentre double-blind randomised control trial. Bone Joint J 2017;99-B:494-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]