Abstract

Obesity, particularly visceral adiposity, has been linked to mitochondrial dysfunction and increased oxidative stress, which have been suggested as mechanisms of insulin resistance. The mechanism(s) behind this remains incompletely understood. In this study, we hypothesized that mitochondrial complex II dysfunction plays a role in impaired insulin sensitivity in visceral adipose tissue of subjects with obesity. We obtained subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue biopsies from 43 subjects with obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) during planned bariatric surgery. Compared with subcutaneous adipose tissue, visceral adipose tissue exhibited decreased complex II activity, which was restored with the reducing agent dithiothreitol (5 mM) (P < 0.01). A biotin switch assay identified that cysteine oxidative posttranslational modifications (OPTM) in complex II subunit A (succinate dehydrogenase A) were increased in visceral vs. subcutaneous fat (P < 0.05). Insulin treatment (100 nM) stimulated complex II activity in subcutaneous fat (P < 0.05). In contrast, insulin treatment of visceral fat led to a decrease in complex II activity (P < 0.01), which was restored with addition of the mitochondria-specific oxidant scavenger mito-TEMPO (10 µM). In a cohort of 10 subjects with severe obesity, surgical weight loss decreased OPTM and restored complex II activity, exclusively in the visceral depot. Mitochondrial complex II may be an unrecognized and novel mediator of insulin resistance associated with visceral adiposity. The activity of complex II is improved by weight loss, which may contribute to metabolic improvements associated with bariatric surgery.

Keywords: adipose tissue, insulin resistance, mitochondrial complex II, mitochondrial function, obesity, succinate dehydrogenase

INTRODUCTION

Obesity has emerged as one of the most critical health care problems, affecting over 600 million people worldwide (33a). In obesity, adipose tissue expands and develops into one of the largest endocrine organs in the body and plays a central role in regulating metabolism and lipid storage. Specifically, increased visceral fat accumulation has been more strongly linked to insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus, and adverse cardiometabolic outcomes compared with subcutaneous fat accumulation in obesity (11, 16, 23). We recently demonstrated that visceral fat exhibits marked impairment in vascular responses to insulin compared with the subcutaneous depot, and there was a significant decrease in insulin-stimulated activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in isolated endothelial cells in the visceral depot with corresponding decrease in insulin-stimulated microvascular relaxation (17). Furthermore, we also showed a reduction in insulin-stimulated adipose arteriolar vasorelaxation in the visceral depot in individuals with obesity, but no impairment was observed in nonobese subjects without diabetes (12). However, the regulatory mechanisms contributing to these findings are incompletely understood. Mitochondrial dysfunction, characterized by increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in adipose tissue, has been linked to metabolic dysfunction (5, 8, 9). There is increased protein carbonylation (35), downregulation of electron transport chain proteins (18), and reduced mitochondrial respiration in visceral compared with subcutaneous fat from obese individuals (18). In particular, adipose tissue mitochondrial dysfunction is more pronounced in subjects with concurrent obesity and diabetes (10).

Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) is a key enzyme in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and also acts as complex II of the electron transport chain, thus participating in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (1). Complex II/SDH may also be a significant source of ROS under pathological conditions (5, 31, 32). We previously demonstrated that increased ROS generation is central to the pathogenesis of obesity-induced metabolic heart disease (31, 32). Visceral adiposity is associated with increased oxidative stress, both systemically and within visceral depots, along with mitochondrial abnormalities (20). There is a strong nexus between visceral adiposity, insulin resistance, diabetes, and development of cardiovascular disease, which is mediated, at least in part, via increased redox stress and mitochondrial dysfunction (25). Our recent work specifically identified that increased ROS generation in obesity-induced metabolic heart disease is due to decreased complex II/SDH activity as a result of oxidative posttranslational modifications (OPTM) of cysteine-rich SDH subunits (31, 32). Given the fact that obesity affects adipose tissue function, we sought to determine whether impaired complex II/SDH function could contribute to the pathogenesis of obesity-induced adipose tissue dysfunction, specifically in visceral adiposity. We compared complex II/SDH activity in subcutaneous vs. visceral adipose tissue obtained from individuals with severe obesity, hypothesizing that complex II activity would be decreased in the visceral depot. Furthermore, we also examined 1) the potential mechanisms responsible for differential enzyme activity; 2) the effects of insulin stimulation on depot-specific SDH activity; and 3) whether bariatric surgical weight loss, with corresponding improvements in metabolic profile, improves complex II activity in both subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue depots.

METHODS

Study Populations

Cross-sectional study.

Consecutive subjects with severe long-standing obesity (obesity > 10 yr; n = 43; body mass index ≥ 35 kg/m2, age ≥ 18 yr), enrolled in the Boston Medical Center Bariatric Surgery Program, were recruited into the study. Samples of subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue were collected intraoperatively from the lower abdominal wall and greater omentum, respectively, during bariatric surgery as previously described (24). Patients with unstable medical conditions or pregnancy were not eligible for gastric bypass surgery and were thus excluded. Throughout the experimental protocol below, samples from both male and female subjects were used. The study was approved by the Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Longitudinal weight loss study.

In a separate cohort, paired subcutaneous and omental adipose tissues were obtained from 10 individuals (n = 5 men, n = 5 women) with severe obesity who underwent roux-en-Y gastric bypass at Wakefield Hospital, Wellington, New Zealand, and ultimately required repeat operations for clinical indications [reasons for repeat operation included incisional hernia repair with (n = 2)/without (n = 8) abdominoplasty]. Repeat operations provided longitudinal access to visceral adipose tissue that otherwise would not have been accessible. Mean time between operations was 18.8 mo, with a range of 10–30 mo. Adipose tissue samples were taken at the time of surgery, immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

All patients gave their written informed consent. The Central Regional Ethics Committee, Wellington, New Zealand, approved the study, which complied with the Helsinki Declaration on human research.

Anthropometric and Biochemical Measures

During a single outpatient visit before planned bariatric surgery, clinical characteristics including blood pressure, height, and weight were measured, along with cardiovascular risk factors. Fasting blood was taken via an antecubital vein for biochemical parameters including lipids, glucose, insulin, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP).

Insulin Stimulation of Adipose Tissue

Freshly collected adipose tissue was cut into 1- to 2-mm pieces and incubated overnight in serum-starved (0.5% serum) EBM-2 medium without growth factors (catalog no. CC5036, Lonza, Hopkinton, MA) containing d-glucose (dextrose) at 5.55 mM concentration. Tissue was then treated with vehicle (control) or 100 nM insulin for 30 min, collected, snap frozen, and stored at −80°C until analysis. For n = 11 subject samples, visceral adipose tissue was preincubated with mito-TEMPO (10 μM) vs. vehicle control (DMSO) for 1 h before stimulation with insulin.

Measurements of Succinate Dehydrogenase (Complex II) Activity

Whole adipose tissue was homogenized in 2 ml of HES buffer (5 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25 M sucrose, pH 7.4 adjusted with 1 M KOH) with a Teflon-on-glass electric homogenizer. All steps were performed at 4°C. The homogenate was centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 9,000 g for 15 min at 4°C, and the mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of HES buffer with 0.3% of fatty acid-free BSA. Protein was quantified with bicinchoninic acid (Pierce), and the value of HES-BSA buffer alone was subtracted. A total of 50 μg of protein per sample was used after total tissue/cell lysis to measure mitochondrial activity.

Complex II enzyme activity of isolated mitochondria was measured with a microplate assay kit (Abcam/Mitosciences, ab109908/MS241), as previously described (15). In this assay, complex II is immunocaptured within the wells of the microplate. The production of ubiquinol by complex II is coupled to the reduction of the dye 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol, and decreases in its absorbance at 600 nm are measured spectrophotometrically. The assay is performed in the presence of succinate as a substrate. Here the assay was performed in the presence and absence of 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Enzymatic activity was normalized to mitochondrial protein concentration.

Biotin Switch Assay

Labeling with biotin iodoacetamide (BIAM; Life Technologies, B-1591) was used in a biotin switch assay to detect reversibly oxidized cysteines as previously described by us, with minor modifications (15). Freshly isolated adipose tissue was immediately snap frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen. Tissue was thawed and lysed in RIPA buffer containing 100 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to block all free thiols and prevent further oxidation. Excess NEM was removed by passing the lysates over Zeba spin columns. NEM-labeled proteins were treated with 5 mM DTT at room temperature for 15 min to reduce reversible oxidations to free thiols and again column cleaned to eliminate DTT. Samples were incubated with 4 mM BIAM for 2 h at room temperature in the dark, labeling any reactive free thiols that were previously reversibly oxidized. BIAM-labeled proteins were isolated from the total protein pool with streptavidin magnetic beads (50 µl) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark, washed, and cleaved from beads by boiling in 30 µl of 2× nonreducing Laemmli buffer for 10 min. Entire BIAM-labeled and unlabeled protein fractions were subjected to Western blotting and probed with anti-SDHA (Abcam, ab14714) antibodies, and bands were detected by near-infrared dye-conjugated secondary antibodies and quantified with the LI-COR Odyssey two-color infrared imaging system. The ratio of labeled to total (labeled + unlabeled) proteins represents the percentage of reversibly oxidized cysteines in SDHA.

Immunoblotting for Mitochondrial Proteins

Proteins were extracted from adipose tissue by homogenization in liquid nitrogen followed by the addition of ice-cold lysis buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.25% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail, phosphatase inhibitor 2 and 3]. Samples were assayed for protein content with Bradford’s method. Twenty to thirty micrograms of protein was subjected to electrophoresis in 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions and then blotted to a PVDF membrane with the Bio-Rad Transblot Turbo Transfer system, blocked with Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR Biosciences), and incubated overnight with the respective anti-human primary antibodies at 4°C. The amount of protein loaded was the same for both depots for each specific subject. Blots were incubated with OXPHOS Human WB Antibody cocktail (1:500) [containing 5 antibodies, 1 each against complex I subunit NDUFB8, complex II subunit B (SDHB), complex III Core protein 2 (UQCRC2), complex IV subunit I (MTCO1), and complex V α-subunit (ATP5A) (Abcam, ab110441)] and anti-VDAC1 (1:500) (Abcam, ab15895) detected with the use of the LI-COR Odyssey two-color infrared imaging system.

Statistics

Analyses of clinical characteristics were performed with SPSS 23.0 and are presented as mean ± SD or percentage. Other analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 6.0 software. Differences between treatment and vehicle control were analyzed with paired t-tests. Paired t-tests were used to analyze differences in responses between subcutaneous and visceral depots from the same patient. Linear regression analysis was performed to examine associations between insulin-stimulated complex II activity in visceral fat and HbA1c. A value of P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Graphic data are presented as means ± SE unless otherwise indicated.

RESULTS

A total of 43 subjects with obesity (body mass index 48.5 ± 11.2 kg/m2, waist circumference 113 ± 15 cm) were recruited for the cross-sectional component of the study. Clinical characteristics of the patients (Table 1) are consistent with the bariatric population at our hospital and other medical centers, with the majority of subjects (n = 32; 74%) being female. In all experiments outlined below samples from both sexes were used, and on detailed analyses there were no significant differences between sexes in any parameters tested.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of bariatric subjects: cross-sectional study

| Parameter | N = 43 |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 42 ± 10 |

| Female [n (%)] | 32 (74) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 48.5 ± 11.2 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 46.5 ± 10.5 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 115.5 ± 30.2 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 178.9 ± 47.5 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 113.9 ± 48 |

| Insulin, mIU/l | 14.3 ± 5.7 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 110.3 ± 64.5 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.0 ± 1.4 |

| hsCRP, mg/dl | 5.8 (0.3, 59.6)* |

| Diabetes [n (%)] | 16 (30) |

| Hypertension [n (%)] | 21 (40) |

| Dyslipidemia [n (%)] | 9 (21) |

Data are presented as means ± SD (total N = 43 subjects), unless stated otherwise. BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Median (min, max).

Downregulation of Activity of Complex II/SDH in Visceral Adipose Tissue Is Due to Reversible Oxidative Posttranslational Cysteine Modifications

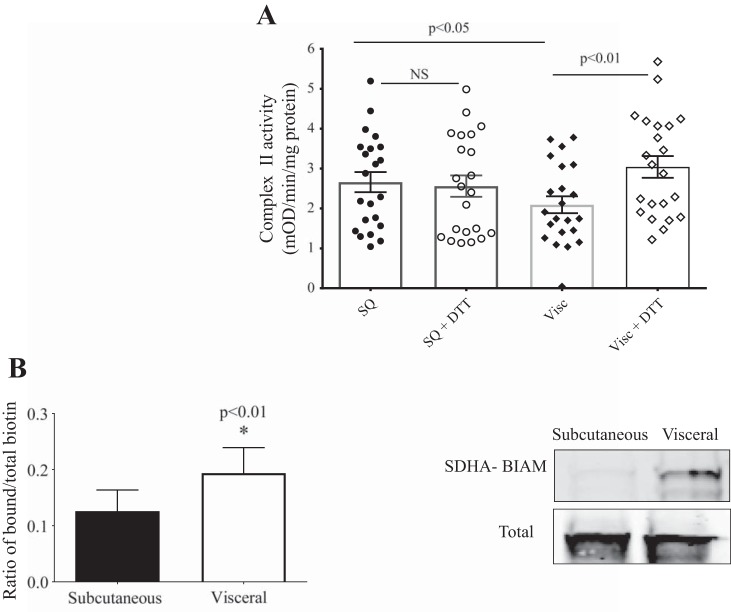

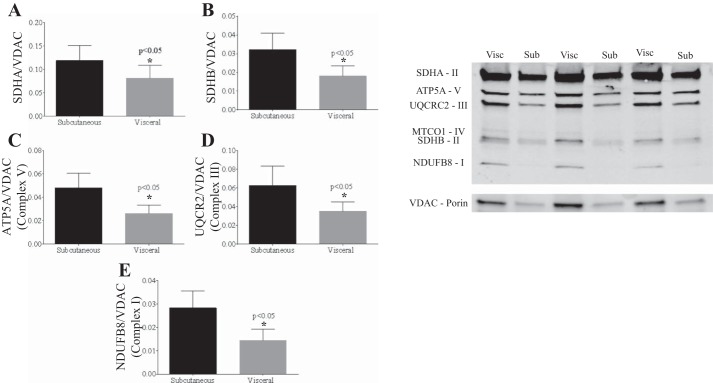

Mitochondrial complex II/SDH activity was significantly decreased in visceral vs. subcutaneous adipose tissue (n = 22, with n = 12 from cross-sectional cohort, n = 10 longitudinal cohort at baseline; P < 0.05) (Fig. 1A). There was also significant downregulation of mitochondrial electron transport chain proteins in the visceral vs. subcutaneous depots (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Complex II/succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity in visceral fat. A: complex II activity is lower and is increased by dithiothreitol (DTT) in visceral (Visc; n = 22) compared with subcutaneous (SQ; n = 22) adipose tissue (repeated measures, 2-way ANOVA analyses). B: increased reversible cysteine posttranslational modifications in SDHA subunit of complex II from visceral vs. subcutaneous fat (biotin switch assay) (n = 4, *P < 0.01). BIAM, biotin iodoacetamide; NS, not significant.

Fig. 2.

Expression of representative proteins of the complexes of electron transport chain and VDAC1. There was a significant reduction in mitochondrial electron transport chain protein expression [succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)A (A), SDHB (B), ATP5A (C), UQCRC2 (D), and NDUFB8 (E)] in visceral (Visc) vs. subcutaneous (Sub) fat (*P < 0.05).

Addition of the reducing agent DTT (5 mM) to the assay selectively restored complex II activity in visceral fat (P < 0.01) while having no effect on subcutaneous fat, suggesting that increased cysteine OPTM were responsible for the reduction in activity seen in the visceral depot (Fig. 1A). Increase in visceral fat complex II OPTM was confirmed with a biotin switch assay, which demonstrated increased reversible cysteine OPTM in SDHA in visceral fat (Fig. 1B).

Relationships Between Baseline Insulin Status and Complex II/SDH Activity in Visceral Fat

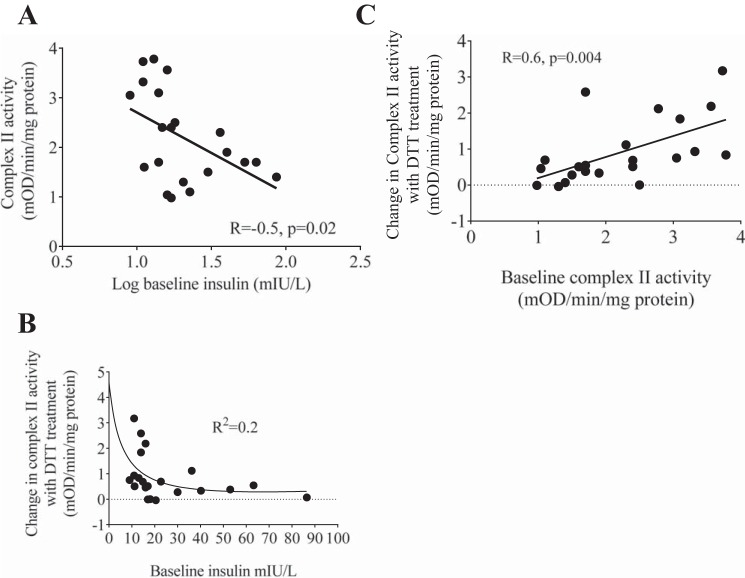

There was a significant correlation between high baseline plasma insulin levels and low complex II activity in the visceral depot, suggesting that hyperinsulinemia is associated with reduced visceral fat complex II activity (Fig. 3A). Additionally, there was a nonlinear relationship between DTT-mediated restoration of complex II activity and baseline insulin levels, consistent with irreversible OPTM of complex II with hyperinsulinemia (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, high baseline complex II activity in the visceral depot was also significantly correlated with greater improvement in DTT-mediated changes in complex II activity (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that there is potential irreversible OPTM in samples with low baseline complex II activity that cannot be reversed by DTT, whereas in samples with higher baseline complex II activity there is reversible OPTM that could restored by DTT.

Fig. 3.

Relationships between complex II/succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity and insulin. In the visceral depot, high baseline plasma fasting insulin levels were significantly correlated with low complex II activity (R = −0.5, P = 0.02; A), there was a nonlinear relationship between baseline insulin levels and dithiothreitol (DTT)-mediated changes in complex II/SDH activity (Spearman’s r = −0.55, Spearman’s correlation = 0.01; B), and baseline complex II activity was correlated with DTT-mediated changes in complex II activity (R = 0.6, P = 0.004; C).

Differential Effects of Insulin Stimulation on Complex II Activity

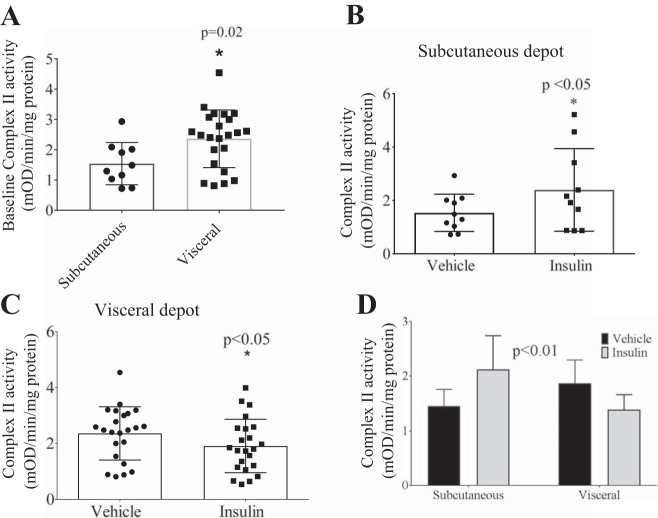

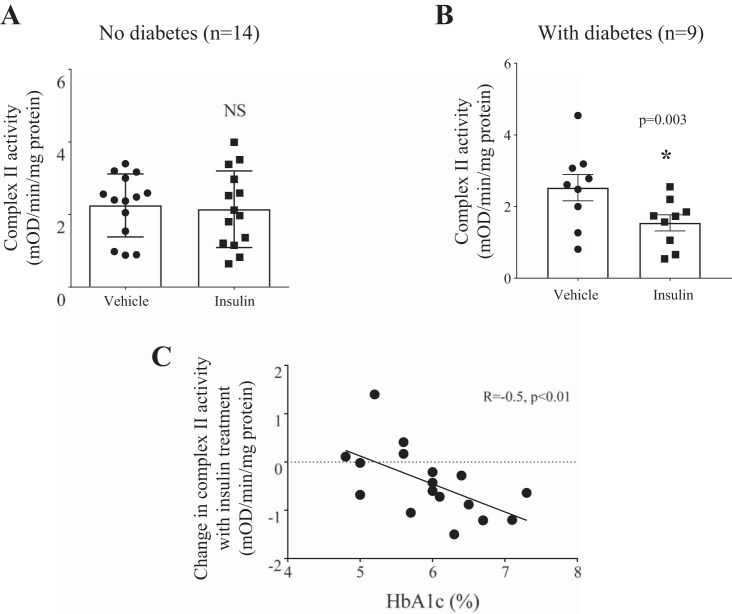

Baseline complex II activity after serum starvation was significantly higher in the visceral vs. subcutaneous depots (P = 0.02, Fig. 4A). Interestingly, although insulin treatment increased complex II activity in the subcutaneous depot (Fig. 4B; n = 10), the insulin effect on complex II activity was reduced in the visceral depot (Fig. 4C; n = 23). In a subset of patients (n = 7), insulin stimulation was performed in paired samples of subcutaneous and visceral fat: exogenous insulin administration increased complex II activity in the subcutaneous depot, whereas in visceral fat complex II activity was significantly decreased (Fig. 4D). Insulin-stimulated complex II activity was significantly decreased in visceral fat from subjects with type 2 diabetes (n = 14 without, n = 9 with diabetes) (Fig. 5, A and B). Furthermore, there was a correlation between high HbA1c and low insulin-stimulated complex II activity (Fig. 5C). Overall, these results suggest that in patients with obesity the presence of diabetes may drive the observed reduced insulin-stimulated complex II activity in visceral fat.

Fig. 4.

Differential effects of insulin stimulation in visceral vs. subcutaneous depots. A) baseline complex II activity after overnight serum starvation was significantly higher in visceral vs. subcutaneous depots (*P = 0.02, unpaired t-test); B) insulin stimulation resulted in significant increases in complex II activity in the subcutaneous depot vs. vehicle (n = 10, *P < 0.05); whereas in the C) visceral depot addition of insulin resulted in a decrease in complex II activity (n = 23, *P < 0.05); and D) there was a significant difference in complex II activity in patients who had both subcutaneous and visceral fat complex II activity in response to insulin treatment (n = 7, P < 0.01, repeated measures 2-way ANOVA).

Fig. 5.

Differential effects of insulin stimulation on complex II activity within the visceral depot in patients with or without diabetes. A: there was no difference in complex II activity with insulin stimulation in patients without diabetes (n = 14). B: insulin-stimulated complex II activity was significantly decreased in patients with diabetes (n = 9, *P = 0.003). C: in the visceral depot high HbA1c was associated with reduced insulin-stimulated complex II activity (R = −0.5, P < 0.01). NS, not significant.

Mitochondria-Targeted ROS Scavenger mito-TEMPO Restores Complex II Activity in Visceral Adipose Tissue Only in Diabetic Patients

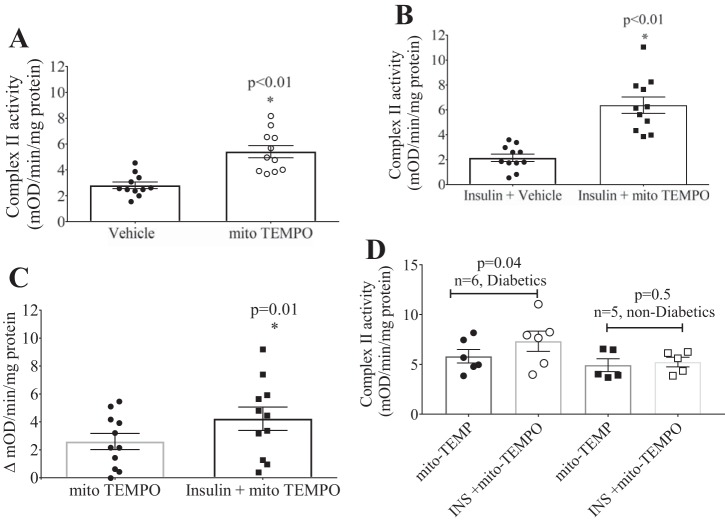

We next hypothesized that scavenging of ROS with a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant would reverse OPTM and restore complex II activity both at baseline and incrementally upon insulin stimulation. Addition of mito-TEMPO (10 μM) significantly increased complex II activity in visceral adipose tissue at baseline (Fig. 6A) and upon insulin stimulation (Fig. 6B). Importantly, mito-TEMPO potentiated the increase in insulin-stimulated complex II activity vs. without insulin stimulation (mito-TEMPO alone) (Fig. 6C). This effect of mito-TEMPO appears to be significant only in patients with diabetes (n = 6) and without effect in patients without diabetes (n = 5) (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Effects of mito-TEMPO on insulin-stimulated complex II activity in the visceral depot. A: mito-TEMPO alone significantly increased complex II activity (n = 11, *P < 0.01). B: addition of mito-TEMPO significantly increased complex II activity in the presence of insulin (n = 11, *P < 0.01). C: combination of mito-TEMPO and insulin incrementally increased complex II activity over mito-TEMPO alone (n = 11, *P = 0.01). D: restoration of complex II activity in the visceral depot with mito-TEMPO was significant in patients with diabetes, whereas this effect was not observed in patients without diabetes.

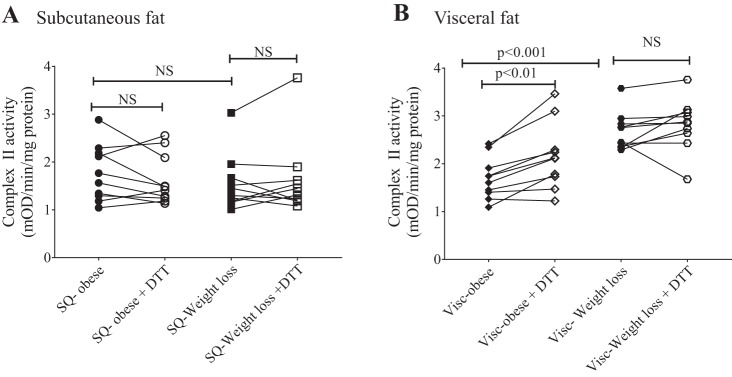

Weight Loss Restores Oxidative Modification of Complex II Activity

Paired subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissues were collected from 10 subjects before and after gastric bypass-induced weight loss. Clinical and anthropometric data for this cohort are described in Table 2. Patients lost nearly 40% of their body weight over a mean 19-mo period. There was no significant difference in complex II activity in the subcutaneous depot before and after weight loss, and addition of DTT did not alter complex II activity at either time point (Fig. 7A). In contrast, in the visceral depot complex II activity significantly increased after weight loss (Fig. 7B). Although addition of DTT significantly increased complex II activity in the visceral fat before weight loss, that effect of DTT was no longer observed after weight loss (Fig. 7B). These novel findings provide strong evidence for complex II OPTM-mediated downregulation of complex activity in the visceral fat of subjects with obesity that is reversed with surgical weight loss.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients in bariatric surgery cohort before and after weight loss: longitudinal study

| Clinical Parameter | Obese Baseline | Weight Loss | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight, kg | 155.8 ± 28.6 | 93.5 ± 12.5 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 54.7 ± 11.2 | 32.7 ± 4.2 | <0.001 |

| Insulin, mIU/l | 37.8 ± 23.8 | 7.1 ± 4.6 | 0.01 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 109.8 ± 25.2 | 88.2 ± 9 | 0.05 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.1 ± 0.5 | 5.3 ± 0.25 | 0.05 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 201 ± 46.4 | 177.9 ± 27.1 | 0.08 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 135.1 ± 42.5 | 100.5 ± 21.7 | 0.04 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 42.5 ± 4.6 | 65.7 ± 42.5 | 0.1 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 173.5 ± 70.0 | 110.7 ± 26.6 | 0.03 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 133.3 ± 19.9 | 118.9 ± 13.4 | 0.03 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 75.9 ± 12.9 | 72.2 ± 9.4 | 0.5 |

Data are expressed as means ± SD; n = 10. BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Fig. 7.

Complex II activity in subcutaneous (SQ) and visceral (Visc) adipose tissue before and after weight loss. Complex II activity in subcutaneous adipose tissue was unaltered by dithiothreitol (DTT) or weight loss (n = 10; A), and complex II activity in visceral adipose tissue increased with DTT before weight loss and was further augmented after weight loss (n = 10; B); however, DTT had no effect on complex II activity in the visceral depot after weight loss. NS, not significant.

DISCUSSION

Obesity and diabetes are associated with impaired lipid and carbohydrate metabolism reflected by elevated circulating levels of lipids and glucose. At the cellular level, lipo- and glucotoxicity result in raised production of oxidants that are increasingly recognized as a cause of protein and cellular dysfunction (34). Metabolic regulation is dependent on mitochondria, which play an important role in energy homeostasis. Reduced mitochondrial function has been reported previously in adipose tissue in human obesity and diabetes (10, 14, 27, 37). However, the mechanisms responsible for these observations have not been elucidated. To our knowledge, no prior studies have characterized mitochondrial complex II function in human adipose tissue in relation to metabolic disease or examined the effect of weight loss in both subcutaneous and visceral fat depots, the latter being extremely difficult to study given the need for repeat abdominal surgery to resample visceral domains. In this study, we thus present first-in-human evidence that mitochondrial complex II activity is decreased in visceral fat in subjects with obesity and diabetes and that weight loss can effectively reverse mitochondrial complex II dysfunction in association with metabolic recovery.

Role of Oxidative Stress in Visceral Adiposity

The mitochondrial electron transport chain, as a series of enzymatic complexes, is a source of oxygen radical generation. Mitochondrial ROS production has been implicated to play a central role in the induction of a prooxidant state and inflammation, processes that are closely linked to development of insulin resistance and diabetes, particularly in visceral adiposity (29). The effects of ROS and redox regulation are mediated mostly by OPTM of proteins. Reversible cysteine OPTM are important in physiological signal transduction and may also mediate disease-related dysregulation (28). Previously, in a mouse model of obesogenic diet-induced metabolic heart disease we demonstrated increased mitochondrial production of H2O2 and oxidative stress, with decreased complex II activity due in part to reversible cysteine OPTM of complex II subunits (31). Increased oxidative stress in visceral adipose tissue has been demonstrated in obesity (19, 35), particularly in subjects with both obesity and diabetes (35). There is now evidence that complex II can be an important source of ROS (3) either directly or indirectly via reverse electron transfer (1). Complex II dysfunction has been implicated in ischemia-reperfusion injury (9) and inflammatory diseases. For example, reversible SDH inhibition with malonate decreased ROS production and infarct size in a mouse model of cardiac ischemia-reperfusion (9). Recently, it was shown that in macrophages increased mitochondrial oxidation of succinate via SDH was the major pathway to shift from producing ATP by oxidative phosphorylation to producing ROS, thereby promoting a shift from the anti-inflammatory (M2) to the pro-inflammatory (M1) state (22), a phenomenon frequently observed in obesity (4). This suggests that mitochondrial complex II dysfunction is a potential mediator of ROS-induced activation of oxidative and inflammatory stress. In this study, we demonstrated that excessive ROS decreases complex II activity exclusively in visceral fat, as administration of the mitochondria-targeted ROS scavenger mito-TEMPO significantly improved complex II activity. Although there was significant downregulation of protein expression of the mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes in the visceral depot, consistent with our finding of lower complex II activity, we also demonstrated restoration of complex II activity in the visceral depot with addition of the cysteine-specific reducing agent DTT, suggesting that the decrease in activity is mediated, at least in part, by reversible cysteine OPTM. We further confirmed this with the biotin switch, demonstrating increased cysteine OPTM of the SDHA subunit of complex II. Restoration of complex II activity with DTT suggests that these OPTM are functionally significant.

Interaction Between Complex II Activity and Insulin Signaling

Our group has previously observed that visceral adipose tissue exhibits blunted responses to insulin stimulation in subjects with obesity (17). Here, we observed that hyperinsulinemic state is associated with reduced complex II/SDH activity in visceral adiposity, and blunted effects of DTT-mediated improvements in complex II activity, indicating for the first time that there is an interaction between complex II activity and insulin signaling in human visceral adipose tissue. Consistent with our findings, mitochondrial complex II or SDH has been implicated in regulating insulin signaling. Succinate, the substrate for complex II/SDH, was found to stimulate insulin signaling via inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatases, whereas inhibition of complex II/SDH activity by malonic acid significantly inhibited the effect of insulin in rat liver (26, 27). Furthermore, changes in complex II have also been linked to diabetes, as skeletal muscle biopsies from patients with obesity and diabetes were found to have significantly lower complex II activity (13, 26). Conversely, treatment with the insulin sensitizer rosiglitazone significantly improved complex II activity (21).

Our findings extend the current literature by demonstrating that mitochondrial complex II activity is downregulated in response to insulin only in the visceral depot and that this can be restored by addition of the mitochondria-targeted ROS scavenger mito-TEMPO, suggesting that decreased insulin-stimulated complex II activity in visceral fat is ROS mediated. Consistent with this, we found that the decrease in insulin-stimulated complex II activity occurred only in patients with diabetes and correlated significantly with HbA1c (a marker of diabetic control) and that mito-TEMPO restored complex II activity only in patients with concurrent diabetes. These results provide clinical evidence that increased mitochondrial ROS may play a major role in OPTM of complex II, which leads to diminished complex II activity and contributes to impaired insulin sensitivity in visceral adiposity.

We also observed a compensatory increase in mitochondrial complex II activity in the visceral depot, after serum starvation, before insulin stimulation in contrast to the subcutaneous depot. Serum starvation is associated with upregulation of insulin-mediated pathways such as Akt, AMPK, GLUT4 (8), and phosphorylated eNOS (33). It is entirely possible that upon serum starvation the more metabolically active visceral depot exhibits basal compensatory increase in complex II. Although there is compensatory increase at baseline, the visceral depot exhibits blunted insulin-stimulated increases in complex II activity. This phenomenon has been observed previously. Serum starvation induced significantly higher eNOS activation in endothelial cells isolated from patients with diabetes vs. those without; however, upon stimulation with insulin eNOS activation was more blunted in patients with diabetes (21). The differences in resting eNOS phosphorylation are concordant with a previous report describing high basal eNOS phosphorylation in obese subjects (30).

Although we cannot elucidate the temporal relationship between complex II-mediated ROS production and occurrence of OPTM, we have previously demonstrated that reversible oxidation of complex II in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity causes reversible inhibition of enzyme activity in association with increased ROS production from complex II (32). Complex II couples the oxidation of succinate to fumarate in the mitochondrial matrix with the reduction of ubiquinone in the membrane and consists of four nuclear-encoded proteins: SDH subunits A, B, C, and D. The complex II activity assay measures the final ability of complex II to reduce ubiquinone (occurring at subunits C and D); however, the catalytic activity (oxidation of succinate) that results in free electron production occurs at subunit A and is independent of reduction of ubiquinone (36). For example, our previous work demonstrates that OPTM of subunit B involve the iron-sulfur cluster, likely leading to changes in conformation of the cluster that affect its ability to bind iron and/or participate in electron transfer (31, 32). This would result in “spillage” of electrons from that site of complex II, leading to increased ROS production, while diminishing the ubiquinone-reducing capacity of complex II (true “activity” of complex II).

Effect of Weight Loss on Complex II Activity

To investigate whether clinical therapeutic approaches can ameliorate complex II dysfunction in obese individuals, we studied the effects of bariatric surgery on complex II activity in visceral and subcutaneous fat over a long follow-up period and in patients who achieved a large percentage of weight loss. We demonstrated that although complex II activity in the subcutaneous fat depot was unaffected by weight loss, complex II activity in the visceral fat depot was decreased in an OPTM-dependent manner (i.e., improved with DTT) and that this was significantly improved with weight loss. Even more importantly, we show that this improvement after weight loss is engendered by a decrease in complex II OPTM as evidenced by the lack of an incremental improvement with DTT. Thus we were able to demonstrate that reversible OPTM of complex II occurs in obesity and is reversed with weight loss primarily in the visceral depot, further demonstrating that improvement in metabolic homeostasis is associated with restoration of complex II activity in human fat.

Limitations

Although our data are the first to demonstrate that OPTM of mitochondrial complex II play a role in the blunted insulin effect in visceral adiposity, further work is required to understand the link between complex II/SDH dysfunction and the various relevant signaling cascades. First, our study was performed entirely with human adipose tissue samples and was therefore limited by a small sample size as determined by the medical operation and clinical care. Thus, despite the high novelty of the findings, the relative role of these specific mitochondrial changes in human visceral fat with regard to their contribution to whole body cardiometabolic disease mechanisms requires further study, potentially requiring experimental animal models. Second, there is inherent variability in complex II activity between subjects in both the subcutaneous and visceral depots as expected in clinical studies. Moreover, the majority of subjects in the cross-sectional component of the study were female; however, this distribution is consistent with prior data from our group and others and general recognition in clinical practice of the female predominance in populations that seek bariatric weight loss surgery treatment (2, 19a). Nevertheless, there were no significant differences in any of the mitochondrial baseline parameters measured between male and female subjects or any sex differences in response to bariatric weight loss. Third, we did not measure complex II activity in adipose tissue in lean subjects and thus could not compare complex II activity between lean and obese individuals. Fourth, although we did not measure other markers of mitochondrial function such as respiration and ATP production, our previous work has demonstrated that in an animal model of obesity there is reduced stage III respiration, complex II-driven respiration, and decreased cardiac ATP production (31, 32). We did not measure ROS production directly; however, given the fact that mito-TEMPO significantly restored complex II activity and insulin sensitivity, we infer that our results are consistent with previous studies that showed increased oxidative stress in visceral adiposity. Finally, it also remains unclear whether mitochondrial complex II dysfunction occurs as a consequence of ROS-mediated impairment of insulin effect or complex II dysfunction causes the ROS-mediated detrimental effects on insulin signaling in visceral adiposity.

Conclusions

We present first-in-human evidence that OPTM of mitochondrial complex II are associated with downregulation of its activity and alteration in metabolism. These data suggest that a targeted approach to reverse the OPTM of complex II may provide potential therapeutic avenues for the restoration of insulin sensitivity and metabolic dysfunction in obesity.

GRANTS

D. T. M. Ngo is supported by the Diabetes Australia Research Trust, The Hospital Research Foundation (South Australia, Australia) and a New South Wales Health EMCR Fellowship (Australia). A. L. Sverdlov is supported by the CJ Martin Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC, APP1037603), an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (14POST20490003), and a Heart Foundation of Australia Future Leader Fellowship (Award ID 101918). S. Karki is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Grant T32 HL-07224. M. G. Farb is supported by NHLBI Grant K23 HL-13539. N. Gokce is supported by NHLBI Grants R01 HL-114675 and R01 HL-126141. W. S. Colucci is supported by NHLBI Grant R01 HL-064750.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.T.M.N., A.L.S., W.S.C., and N.G. conceived and designed research; D.T.M.N., A.L.S., S.K., M.G.F., B.C., and D.T.H. performed experiments; D.T.M.N., A.L.S., S.K., D.M.-C., and R.S.S. analyzed data; D.T.M.N., A.L.S., D.M.-C., R.S.S., M.G.F., B.C., D.T.H., W.S.C., and N.G. interpreted results of experiments; D.T.M.N. and A.L.S. prepared figures; D.T.M.N. drafted manuscript; D.T.M.N., A.L.S., S.K., D.M.-C., R.S.S., M.G.F., B.C., D.T.H., W.S.C., and N.G. edited and revised manuscript; D.T.M.N., A.L.S., S.K., D.M.-C., R.S.S., M.G.F., B.C., D.T.H., W.S.C., and N.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bezawork-Geleta A, Rohlena J, Dong L, Pacak K, Neuzil J. Mitochondrial complex II: at the crossroads. Trends Biochem Sci 42: 312–325, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bigornia SJ, Farb MG, Tiwari S, Karki S, Hamburg NM, Vita JA, Hess DT, Lavalley MP, Apovian CM, Gokce N. Insulin status and vascular responses to weight loss in obesity. J Am Coll Cardiol 62: 2297–2305, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brand MD. Mitochondrial generation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide as the source of mitochondrial redox signaling. Free Radic Biol Med 100: 14–31, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castoldi A, Naffah de Souza C, Câmara NO, Moraes-Vieira PM. The macrophage switch in obesity development. Front Immunol 6: 637, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen YR, Zweier JL. Cardiac mitochondria and reactive oxygen species generation. Circ Res 114: 524–537, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ching JK, Rajguru P, Marupudi N, Banerjee S, Fisher JS. A role for AMPK in increased insulin action after serum starvation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C1171–C1179, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00514.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chouchani ET, Pell VR, Gaude E, Aksentijević D, Sundier SY, Robb EL, Logan A, Nadtochiy SM, Ord EN, Smith AC, Eyassu F, Shirley R, Hu CH, Dare AJ, James AM, Rogatti S, Hartley RC, Eaton S, Costa AS, Brookes PS, Davidson SM, Duchen MR, Saeb-Parsy K, Shattock MJ, Robinson AJ, Work LM, Frezza C, Krieg T, Murphy MP. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature 515: 431–435, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nature13909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahlman I, Forsgren M, Sjögren A, Nordström EA, Kaaman M, Näslund E, Attersand A, Arner P. Downregulation of electron transport chain genes in visceral adipose tissue in type 2 diabetes independent of obesity and possibly involving tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Diabetes 55: 1792–1799, 2006. doi: 10.2337/db05-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farb MG, Gokce N. Visceral adiposopathy: a vascular perspective. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 21: 125–136, 2015. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2014-0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farb MG, Karki S, Park SY, Saggese SM, Carmine B, Hess DT, Apovian C, Fetterman JL, Bretón-Romero R, Hamburg NM, Fuster JJ, Zuriaga MA, Walsh K, Gokce N. WNT5A-JNK regulation of vascular insulin resistance in human obesity. Vasc Med 21: 489–496, 2016. doi: 10.1177/1358863X16666693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He J, Watkins S, Kelley DE. Skeletal muscle lipid content and oxidative enzyme activity in relation to muscle fiber type in type 2 diabetes and obesity. Diabetes 50: 817–823, 2001. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heinonen S, Buzkova J, Muniandy M, Kaksonen R, Ollikainen M, Ismail K, Hakkarainen A, Lundbom J, Lundbom N, Vuolteenaho K, Moilanen E, Kaprio J, Rissanen A, Suomalainen A, Pietiläinen KH. Impaired mitochondrial biogenesis in adipose tissue in acquired obesity. Diabetes 64: 3135–3145, 2015. doi: 10.2337/db14-1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horowitz JD, Chong CR, Ngo DT, Sverdlov AL. Effects of acute hyperglycaemia on cardiovascular homeostasis: does a spoonful of sugar make the flow-mediated dilatation go down? J Thorac Dis 7: E607–E611, 2015. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.12.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karki S, Ngo DT, Bigornia SJ, Farb MG, Gokce N. Insulin resistance: a key therapeutic target for cardiovascular risk reduction in obese patients? Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab 9: 93–95, 2014. doi: 10.1586/17446651.2014.878646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karki S, Farb MG, Ngo DT, Myers S, Puri V, Hamburg NM, Carmine B, Hess DT, Gokce N. Forkhead box O-1 modulation improves endothelial insulin resistance in human obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35: 1498–1506, 2015. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.305139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraunsøe R, Boushel R, Hansen CN, Schjerling P, Qvortrup K, Støckel M, Mikines KJ, Dela F. Mitochondrial respiration in subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue from patients with morbid obesity. J Physiol 588: 2023–2032, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.184754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long EK, Olson DM, Bernlohr DA. High-fat diet induces changes in adipose tissue trans-4-oxo-2-nonenal and trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal levels in a depot-specific manner. Free Radic Biol Med 63: 390–398, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 361: 445–454, 2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMurray F, Patten DA, Harper ME. Reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress in obesity—recent findings and empirical approaches. Obesity (Silver Spring) 24: 2301–2310, 2016. doi: 10.1002/oby.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mensink M, Hesselink MK, Russell AP, Schaart G, Sels JP, Schrauwen P. Improved skeletal muscle oxidative enzyme activity and restoration of PGC-1 alpha and PPAR beta/delta gene expression upon rosiglitazone treatment in obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Obes 31: 1302–1310, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mills EL, Kelly B, Logan A, Costa AS, Varma M, Bryant CE, Tourlomousis P, Däbritz JH, Gottlieb E, Latorre I, Corr SC, McManus G, Ryan D, Jacobs HT, Szibor M, Xavier RJ, Braun T, Frezza C, Murphy MP, O’Neill LA. Succinate dehydrogenase supports metabolic repurposing of mitochondria to drive inflammatory macrophages. Cell 167: 457–470.e13, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neeland IJ, Turer AT, Ayers CR, Powell-Wiley TM, Vega GL, Farzaneh-Far R, Grundy SM, Khera A, McGuire DK, de Lemos JA. Dysfunctional adiposity and the risk of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in obese adults. JAMA 308: 1150–1159, 2012. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ngo DT, Farb MG, Kikuchi R, Karki S, Tiwari S, Bigornia SJ, Bates DO, LaValley MP, Hamburg NM, Vita JA, Hess DT, Walsh K, Gokce N. Antiangiogenic actions of vascular endothelial growth factor-A165b, an inhibitory isoform of vascular endothelial growth factor-A, in human obesity. Circulation 130: 1072–1080, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niemann B, Rohrbach S, Miller MR, Newby DE, Fuster V, Kovacic JC. Oxidative Stress and cardiovascular risk: obesity, diabetes, smoking, and pollution. J Am Coll Cardiol 70: 230–251, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oberbach A, Bossenz Y, Lehmann S, Niebauer J, Adams V, Paschke R, Schön MR, Blüher M, Punkt K. Altered fiber distribution and fiber-specific glycolytic and oxidative enzyme activity in skeletal muscle of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 29: 895–900, 2006. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patti ME, Corvera S. The role of mitochondria in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev 31: 364–395, 2010. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pimentel D, Haeussler DJ, Matsui R, Burgoyne JR, Cohen RA, Bachschmid MM. Regulation of cell physiology and pathology by protein S-glutathionylation: lessons learned from the cardiovascular system. Antioxid Redox Signal 16: 524–542, 2012. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruskovska T, Bernlohr DA. Oxidative stress and protein carbonylation in adipose tissue—implications for insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus. J Proteomics 92: 323–334, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silver AE, Beske SD, Christou DD, Donato AJ, Moreau KL, Eskurza I, Gates PE, Seals DR. Overweight and obese humans demonstrate increased vascular endothelial NAD(P)H oxidase-p47(phox) expression and evidence of endothelial oxidative stress. Circulation 115: 627–637, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.657486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sverdlov AL, Elezaby A, Behring JB, Bachschmid MM, Luptak I, Tu VH, Siwik DA, Miller EJ, Liesa M, Shirihai OS, Pimentel DR, Cohen RA, Colucci WS. High fat, high sucrose diet causes cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction due in part to oxidative post-translational modification of mitochondrial complex II. J Mol Cell Cardiol 78: 165–173, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sverdlov AL, Elezaby A, Qin F, Behring JB, Luptak I, Calamaras TD, Siwik DA, Miller EJ, Liesa M, Shirihai OS, Pimentel DR, Cohen RA, Bachschmid MM, Colucci WS. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species mediate cardiac structural, functional, and mitochondrial consequences of diet-induced metabolic heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc 5: 002555, 2016. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tabit CE, Shenouda SM, Holbrook M, Fetterman JL, Kiani S, Frame AA, Kluge MA, Held A, Dohadwala MM, Gokce N, Farb MG, Rosenzweig J, Ruderman N, Vita JA, Hamburg NM. Protein kinase C-β contributes to impaired endothelial insulin signaling in humans with diabetes mellitus. Circulation 127: 86–95, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.127514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33a.WHO Obesity and Overweight Fact Sheet (Online). https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/ 2016.

- 34.Wold LE, Ceylan-Isik AF, Ren J. Oxidative stress and stress signaling: menace of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Acta Pharmacol Sin 26: 908–917, 2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu XJ, Gauthier MS, Hess DT, Apovian CM, Cacicedo JM, Gokce N, Farb M, Valentine RJ, Ruderman NB. Insulin sensitive and resistant obesity in humans: AMPK activity, oxidative stress, and depot-specific changes in gene expression in adipose tissue. J Lipid Res 53: 792–801, 2012. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P022905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yankovskaya V, Horsefield R, Törnroth S, Luna-Chavez C, Miyoshi H, Léger C, Byrne B, Cecchini G, Iwata S. Architecture of succinate dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species generation. Science 299: 700–704, 2003. doi: 10.1126/science.1079605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yin X, Lanza IR, Swain JM, Sarr MG, Nair KS, Jensen MD. Adipocyte mitochondrial function is reduced in human obesity independent of fat cell size. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99: E209–E216, 2014. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]