Abstract

Objective

To compare efficacy and safety of subcutaneous sarilumab 200 mg and 150 mg every 2 weeks plus conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (+csDMARDs) versus other targeted DMARDs+csDMARDs and placebo+csDMARDs, in inadequate responders to csDMARDs (csDMARD-IR) or tumour necrosis factor α inhibitors (TNFi-IR).

Methods

Systematic literature review and network meta-analyses (NMA) conducted on 24 week efficacy and safety outcomes: Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index, modified total sharp score (mTSS, including 52 weeks), American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20/50/70, European League Against Rheumatism Disease Activity Score 28-joint count erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28)<2.6; serious infections/serious adverse events (including 52 weeks).

Results

53 trials were selected for NMA. csDMARD-IR: Sarilumab 200 mg+csDMARDs and 150 mg+csDMARDs were superior versus placebo+csDMARDs on all outcomes. Against most targeted DMARDs, sarilumab 200 mg showed no statistically significant differences, except superiority to baricitinib 2 mg, tofacitinib and certolizumab on 24 week mTSS. Sarilumab 150 mg was similar to all targeted DMARDs. TNFi-IR: Sarilumab 200 mg was similar to abatacept, golimumab, tocilizumab 4 mg and 8 mg/kg intravenously and rituximab on ACR20/50/70, superior to baricitinib 2 mg on ACR50 and DAS28<2.6 and to abatacept, golimumab, tocilizumab 4 mg/kg intravenously and rituximab on DAS28<2.6. Sarilumab 150 mg was similar to targeted DMARDs but superior to baricitinib 2 mg and rituximab on DAS28<2.6 and inferior to tocilizumab 8 mg on ACR20 and DAS28<2.6. Serious adverse events, including serious infections, appeared similar for sarilumab versus comparators.

Conclusions

Results suggest that in csDMARD-IR and TNFi-IR (a smaller network), sarilumab+csDMARD had superior efficacy and similar safety versus placebo+csDMARDs and at least similar efficacy and safety versus other targeted DMARDs+csDMARDs.

Keywords: sarilumab, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, rheumatoid arthritis, network meta-analysis

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

The addition of bDMARDs to csDMARDs is recommended in guidelines from ACR and EULAR for achieving remission or reducing disease activity in patients with RA who have an inadequate response to csDMARDs alone.

Given the variety of treatments currently available for RA, a comprehensive evaluation of the comparative effectiveness and safety of sarilumab against other DMARDs is necessary to inform treatment decisions and health technology assessments, as well as to guide evidence-based medicine.

What does this study add?

In the absence of head-to-head trials, network meta-analysis can provide estimates of comparative effectiveness via the combined evaluation of direct and indirect trial evidence.

For inadequate responders of csDMARDs or tumour necrosis factor inhibitors, sarilumab 150 mg and 200 mg subcutaneous every 2 weeks plus csDMARDs had superior efficacy and similar safety versus continued use of csDMARDs alone. Sarilumab 150 mg and 200 mg had at least similar efficacy versus all other comparable doses of targeted DMARDs added to csDMARDs.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Physicians may use these results from this clinical study to inform treatment decisions for patients with RA.

Introduction

The addition of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) (including tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors (TNFi), T cell costimulatory inhibitors, anti-B cell agents and anti-interleukin-6 receptor (anti-IL-6R) monoclonal antibodies) or targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) to conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs) is recommended in guidelines issued by both The American College of Rheumatology (ACR)1 and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)2 for achieving remission or reducing disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who have inadequate response (IR) to csDMARDs alone. Sarilumab is a human immunoglobulin (Ig) G1 anti-IL-6Rα monoclonal antibody for the treatment of RA as monotherapy or combination therapy with csDMARDs.3–6 Given the variety of treatments currently available for RA, a comprehensive evaluation of the comparative effectiveness and safety of sarilumab against other DMARDs is necessary to inform treatment decisions and health technology assessments, as well as to guide evidence-based medicine.7

Active comparator randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard methodological approach for comparative efficacy.8 However, research is mainly characterised by placebo-controlled studies, while head-to-head trials are not readily available. In the absence of head-to-head studies, network meta-analysis (NMA) can provide estimates of comparative effectiveness via the combined evaluation of direct and indirect trial evidence;9–11 treatments can then be compared with each other via common comparators.

This NMA was conducted to evaluate the comparative efficacy and safety of subcutaneous (SC) sarilumab at doses of 150 mg and 200 mg, administered every 2 weeks (q2w) and added to csDMARDs. Sarilumab was evaluated versus other licensed treatments for RA, including csDMARDs, bDMARDs and tsDMARDs, at recommended doses for the treatment of RA, in two groups of patients: csDMARD-IR and TNFi-IR. The csDMARD-IR population was studied separately for combination therapy and monotherapy. The focus of the current NMA is on patients receiving an addition of a bDMARD or tsDMARD to their existing csDMARD treatment regimen.

Methods

A systematic literature review (SLR) and NMA were conducted following methods in line with PRISMA guidelines12 and recommended in the current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) specification for manufacturer and sponsor submission of evidence13 and the 2016 NICE technology appraisal of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab and abatacept for RA.14

Study selection

Searches for the SLR were conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane databases (all with no backwards time limit) and conference proceedings (since 2013), on evidence published until 6 December 2016, and studies were selected according to predefined PICOS (population/intervention/comparator/outcome/study design) criteria12 13 15 16 (table 1). All titles, abstracts and articles were screened independently by two researchers, with study selection following published best practice guidelines for NMA.13 15 16 Data on study design, patient characteristics, efficacy, safety and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) at the time points 12 (±4), 24 (±4) and 52 (±8) weeks for all studies (except open-label extensions) were extracted independently by two reviewers in a predefined data extraction process.

Table 1.

Population/intervention/comparator/outcome/study design and search criteria for the systematic review

| Criteria | Inclusion | ||

| Study design | Randomised controlled trials above phase I (including crossover studies up to time of crossover) |

||

| Population |

|

||

| Treatment/intervention | The following interventions are of interest at any dosage or administration type: | ||

|

|

|

|

| Comparator | Placebo or any of the above listed treatments in combination with a csDMARD(s) (ie, methotrexate, leflunomide, hydroxychloroquine, minocycline, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, sodium aurothiomalate and auranofin) or csDMARD as monotherapy or in combination with other csDMARD(s). | ||

| Outcomes | Efficacy, safety and patient-reported outcomes at 24 weeks (±4 weeks) and 52 weeks (±8 weeks). | ||

| Time | No limit on time horizon. | ||

| Language | English language. | ||

csDMARD, conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

Evidence for the NMA was filtered for drugs licensed for RA at doses approved in Europe, the USA and Canada. In addition, the investigational drug baricitinib 2 mg daily (qd) and 4 mg qd combined with methotrexate/csDMARD were included as this agent was at advanced regulatory stages at the time of analyses. Rituximab (currently only licensed for the TNFi-IR population) was included for the csDMARD-IR population in the interest of providing a bridge for relevant comparators, while anakinra was excluded due to its uncommon use, in addition to its reported limited effectiveness relative to other biologics.1

All trials comparing one intervention of interest with at least one other intervention of interest or methotrexate or ≥1 csDMARD(s) were considered in the evidence base. Small studies (less than 30 patients per arm) were excluded from the evidence base on the basis that small studies have been shown to distort meta-analyses.17 Studies that did not report any outcomes of interest were also excluded.

Treatment categorisation

Treatment categorisation was based on grouping all the available treatments for inclusion in the networks (table 2). Methotrexate and csDMARD used as background therapies were considered similar and grouped, while randomised treatment groups with one csDMARD+methotrexate were separated from those including two csDMARDs+methotrexate. Different licensed dosages and different routes of administration (eg, intravenous (IV) vs SC delivery) of the same treatment were pooled in many cases, on the basis of evidence of equivalence (table 2). These decisions were explored by examining forest plots of the OR for ACR20 at 24 weeks in individual studies by group of interventions. If the confidence intervals were overlapping (eg, for infliximab studies), the doses were pooled. The validity of the decisions was also confirmed via clinician input.

Table 2.

Key features of patient demographics and baseline data for selected studies

| csDMARD-IR | |

| Patient demographics | |

| Age | Mean ages were similar between all studies (and study arms) ranging from 46.7 years35 to 57.3 years36–38 |

| Sex | In all trials except ATTEST, the majority of patients were female |

| Ethnicity | In those trials reporting ethnicity, the majority of the patients were Caucasian, although in seven trials, the entire population was Asian35 39–45 |

| Patient baseline clinical status | |

| Weight | Mean weight ranged from 52.9 kg (J-RAPID) to 82 kg (MEASURE) |

| Proportion rheumatoid factor positive | The proportion of patients who were rheumatoid factor positive was above 60% in all studies reporting this value, except for the ASSET trial (55.6% for abatacept intravenous 8 mg/kg q4w+methotrexate) |

| Disease duration | Mean disease duration ranged widely, from 6 months (SWEFOT) to 13.1 years (ARMADA) |

| Tender joint count | Mean tender joint count ranged from 3 (ENCOURAGE) to 35 (DANCER) on the 68-count scale |

| Swollen joint count | Mean swollen joint count ranged from 3.2 (CERTAIN) to 24.0 (ATTRACT) on the 66-count scale |

| Prior DMARD use | Prior DMARD use ranged from 1.1 (STAR) to 3.1 (ARMADA) in 26 studies that reported prior DMARD use |

| TNFi-IR | |

| Patient demographics | |

| Age | Mean ages were similar across the patient populations, ranging from 50.94 years (RADIATE) to 58.2 years (ORAL Step) |

| Sex | The majority of patients were female |

| Ethnicity | In those trials reporting ethnicity, the majority of the patients were Caucasian |

| Patient baseline clinical status | |

| Weight | Two studies reported mean weight from 78.2 kg (ATTAIN) to 79.4 kg (TARGET) |

| Proportion rheumatoid factor positive | The proportion of patients who were rheumatoid factor positive varied from 51% (Manders 2014) to 79% (TARGET, RADIATE and REFLEX) |

| Disease duration | Mean disease duration ranged from 5.6 years (Manders 2014) to 14.0 years46 (RA-BEACON) |

| Tender joint count | Mean tender joint count ranged from 27.6 (ORAL step) to 33.9 (REFLEX) |

| Swollen joint count | Mean swollen joint count ranged from 6 (RA-BEACON) to 23.4 (REFLEX) |

| Prior DMARD use | In the two studies (REFLEX and RADIATE) reporting prior csDMARD use, the use varied from 1.9 (RADIATE) to 2.6 (REFLEX) |

| Baseline disease severity | Mean DAS28 differed between the studies. For the csDMARD or methotrexate arms, the mean baseline DAS28-CRP ranged from 5.4 (ORAL Step) to 6.9 (REFLEX); the DAS28-ESR from 4.7 (Manders et al 2015) to 6.5 (ORAL Step) and the DAS28-unspecified from 6.5 (ATTAIN) to 6.8 (RADIATE) |

CRP, C reactive protein; csDMARD, conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs;DAS-28, Disease Activity Score 28-joint count; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IR, inadequate response; TNF, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

Outcomes examined for the NMA included: ACR 20%, 50% and 70% (ACR20/50/70) response criteria, EULAR Disease Activity Score 28-joint count (DAS28) remission (defined as DAS28 erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C reactive protein (CRP) <2.6), Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) change from baseline (CFB), modified total sharp score (mTSS) CFB, incidence of serious infections (SIs) and serious adverse events (SAEs). However, as different studies reported different scores for radiographic progression, for example, van der Heijde mTSS or Genant total sharp score, only the studies reporting van der Heijde mTSS were considered for this endpoint; the other scoring systems were deemed to be incomparable.18

All efficacy outcomes were examined at 24 weeks; mTSS was also evaluated at week 52 in addition to week 24; SI and SAE in the csDMARD-IR and TNFi-IR populations were evaluated at week 24 and week 52, respectively.

Network meta-analysis

NMA feasibility assessment

The sufficiency of the evidence base to draw feasible networks was assessed for all outcomes of interest. The exchangeability assumption is critical and requires that selected trials measure the same underlying relative treatment effects. Deviations to this assumption can be evaluated through two metrics: (1) heterogeneity (ie, evaluation of comparability in characteristics and results across included studies) and (2) consistency (ie, evaluation of consistency between direct and indirect evidence).

A high level of variability in placebo response was observed across both the csDMARD-IR and TNFi-IR networks. Such heterogeneity of response in the placebo arms of the studies (ie, placebo+csDMARDs in combination studies) has previously been noted in other RA clinical studies and by NICE.19 Therefore, to account for the variation in the placebo responses across studies, alternative analytic methods were applied in the present NMA.

For the larger csDMARD-IR combination network, NMA with regression on baseline risk (BR-NMA) was used to adjust for variability in placebo responder rates. The BR-NMA model is similar to the conventional NMA method with the addition of an adjustment for the baseline odds and better adjusts for potential bias introduced by variability in the placebo responder rates across the different studies. This approach is recommended by NICE Decision Support Unit (DSU) guidelines.20 However, as only binary outcomes have sufficient data to facilitate the BR-NMA, NMA with regression on baseline risk for placebo response was conducted on binary outcomes (ACR20/50/70 and DAS28 remission) as the base case model for the csDMARD-IR population.

For any regression, a relatively high number of studies per covariate is necessary, otherwise the model is unlikely to converge and less precise estimations are produced, resulting in wide credible intervals around the point estimates. In previous NMAs, prior to the publication of NICE guidance to address the problem of high variation of study effects, a conventional OR approach was applied, which gave inconsistent results (eg, this may have overestimated relative effect for treatment with studies having low study effect and reverse).19 Therefore, for the smaller TNFi-IR network, an alternative method of NMA based on risk differences (RD-NMA) was adopted,13 21 whereby a risk difference scale is used in place of a log OR scale; responder levels are treated as continuous outcomes following a normal distribution. This approach was based on Spiegelhalter and colleagues21 and practical guidance in the NICE DSU Guidance on Network Meta-Analysis.20

For safety outcomes, a conventional OR model was used for SAE in the csDMARD combination population, and for SI and SAE in the TNFi-IR population. RD-NMA was applied for SI in the csDMARD-IR population due to convergence issues in the OR model.

Bayesian NMA

The selected outcomes, that is, relative efficacy and safety of the treatments of interest, were evaluated using a Bayesian NMA approach,16 22 23 which involves a likelihood distribution, a model with parameters and prior distributions for these parameters. In this analysis, a linear model with normal likelihood distribution was used for continuous outcomes, and a binomial likelihood with a log link for the dichotomous outcomes.20 21 Flat (non-informative) prior distributions were assumed for nearly all outcomes so as not to influence the observed results by the prior distribution; this approach was consistent with NICE guidelines.20 Prior distributions of the baseline treatments and relative treatment effects were normal, with zero mean and variance of 10 000, while a uniform distribution with range zero to five was used as the prior of the between-study SD.

For most outcomes, random-effects and fixed-effects models were evaluated to allow for heterogeneity of treatment effects between studies. Random-effects models were applied where sufficient data were available; where the number of studies was smaller (eg, most outcomes in the TNFi-IR population), it was necessary to use the fixed-effects model, as random-effects models would provide unrealistically wide credible intervals for such limited datasets. Where both random-effects and fixed-effects models were run, the choice of base case was informed by Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) values.21 Total residual deviance (compared against the number of fitted data points) was also considered in model selection, indicating the adequacy of the model to the data. In addition, the consistency of modelled data with directly reported trial results was also taken into consideration in selecting the preferred model.

Posterior densities for unknown parameters were estimated using Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations. All results for conventional OR and RD-NMA were based on 100 000 iterations on three chains, with a burn-in of 20 000 iterations. All results for BR-NMA models were based on 70 000 iterations on three chains, with a burn-in of 15 000 iterations. Convergence was assessed by visual inspection of trace plots. The accuracy of the posterior estimates was assessed using the Monte Carlo error for each parameter (Monte Carlo error <1% of the posterior SD). All models were implemented using WinBUGS.14

Bayesian NMA provided posterior distributions of the relative treatment effects between interventions and the probability that one treatment is better than another for each outcome of interest. The results of the NMA are presented in terms of ‘point estimates’ (median of posterior) for the relative treatment effects, along with the 95% credible intervals.

Scenario analyses

A series of scenario analyses were conducted whereby outlier studies excluded (or included) in the base case were included (or excluded) in separate scenarios (online supplementary table 3). In csDMARD-IR, a scenario was tested to address the potential modifying effect of patient weight. Weight was selected as a potential modifier by first establishing the link via scatter plot and a trend, and then evaluating the regression and coefficient of R2 between patient characteristics at baseline and ACR20. This process identified weight as a potential effect modifier. However, meta-regression using average weight of the study as a variable was not possible due to the level of missing data for weight across the studies. Instead, those studies conducted in exclusively Asian populations were excluded in a scenario analysis. The basis of this exclusion was that Asian ethnicity would serve as a proxy for populations with relatively lower weight than other populations.

rmdopen-2018-000798supp001.htm (163.6KB, htm)

In a separate scenario, the ATTRACT and SWEFOT studies were included in a scenario and mTSS at 52 weeks was examined; ATTRACT (and the connected SWEFOT study of interferon triple-combination therapy with two csDMARDs and methotrexate) was initially excluded in the base case due to a high mTSS at baseline. In an additional scenario in csDMARD-IR, TNFi were pooled together as a class; ACR outcomes were compared with the base case, which evaluated the TNFi individually. This scenario was evaluated to inform cost-effectiveness evaluations of sarilumab.

Finally, a scenario analysis in the TNFi-IR population considered exclusion of the GO-AFTER study, which evaluated a mix of monotherapy and combination therapy.

Results

Literature search and selection

The literature search identified a total of 15 698 citations (figure 1) relevant to DMARD combination treatments and monotherapies for RA. Three hundred and nine citations that met the screening criteria, reporting results of 108 trials, were retrieved. Of these, 87 RCTs were included in the SLR, but 32 were excluded based on the n<30 sample size or owing to not reporting outcomes of interest, invalid study design or not linked in network (including RACAT and Machado 2014 reported data on the outcomes of interest but could not be linked in the analyses networks; these were subsequently pooled with other TNFi studies in scenario analysis). RACAT was also excluded, as the control arm is not a single csDMARD but a combination of sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine. There were no equivalent controls from other RCTs.

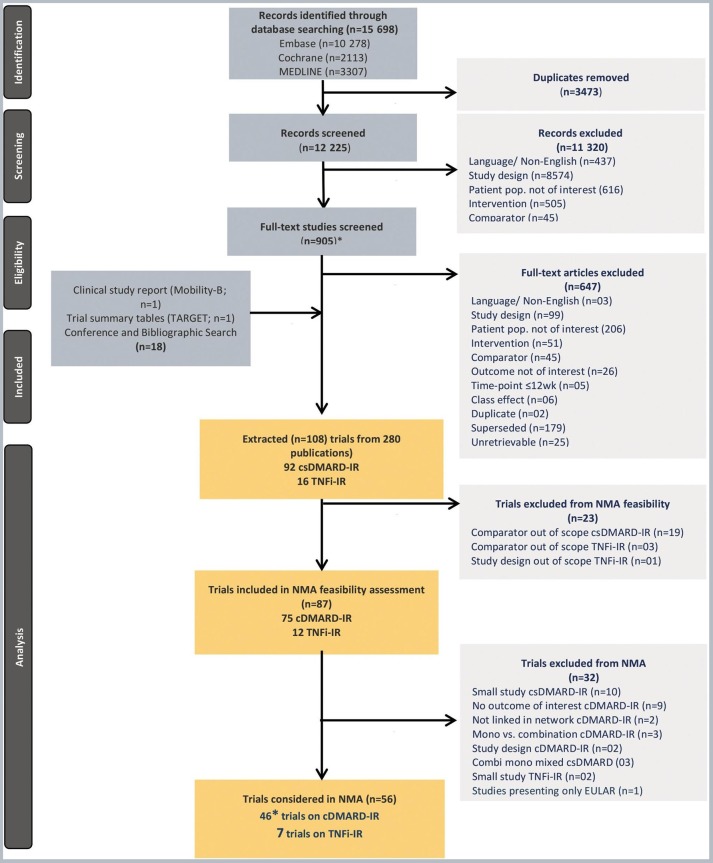

Figure 1.

Systematic review and network meta-analyses study selection flow chart. *45 studies reporting outcomes at week 24 and one study reporting outcome at week 52. csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; IR, inadequate responders; NMA, network meta-analyses; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor α inhibitors.

A total of 46 RCTs (45 studies at week 24 and one study at week 52) were included for the csDMARD-IR population and nine RCTs were included for the TNFi-IR population for the present NMA in combination treatments (figure 1). These included the three sarilumab+csDMARD combination treatment RCTs: MOBILITY-A, MOBILITY-B and TARGET.

NMA evidence base

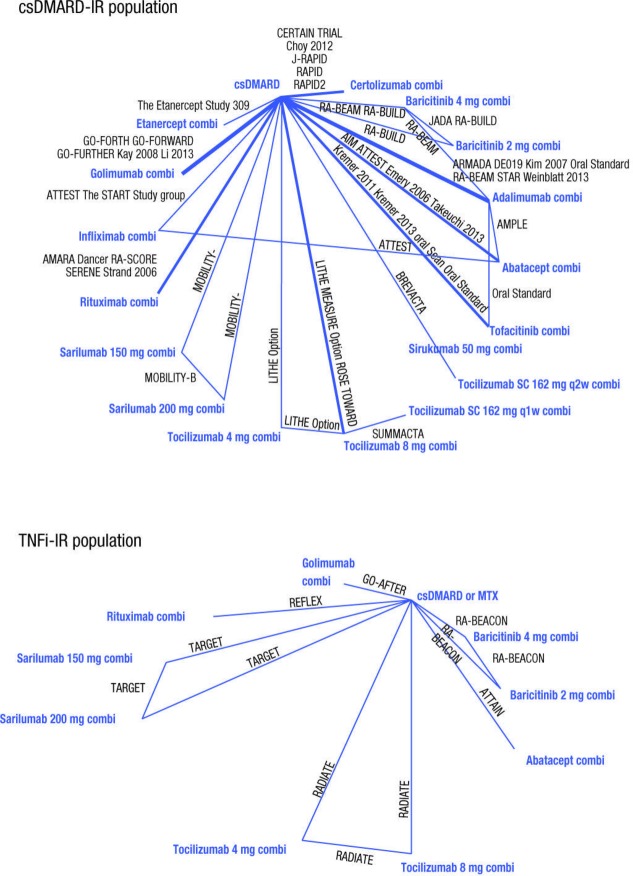

Although sarilumab has been evaluated in phase III studies across both csDMARD-IR and TNFi-IR patient populations, availability of data for the other comparators varied across the two populations; most data were in csDMARD-IR patients, with fewer RCTs in the TNFi-IR setting, limiting the ability to accurately evaluate the comparative efficacy of combination therapies in TNFi-IR. For both patient populations, the networks for EULAR response were small and a high level of variability was observed in response rates between different studies and thus these results are not reported here. The networks for ACR response, with ACR20 in particular, were the most robust for both populations (figure 2) where most interventions were included in multiple trials. Based on previously published studies, high variation in the placebo response rates was observed across studies.14 24

Figure 2.

Evidence base networks for American College of Rheumatology 20 outcomes at 24 weeks. Comi, combination; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; IR, inadequate responders; MTX, methotrexate; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor α inhibitors.

Key features of patient demographics and baseline data from the selected studies are provided in table 2.

csDMARD-IR studies

Among 46 trials included in csDMARD combination population (online supplementary table 1), 29 were phase III trials, seven were phase II trials, two were phase II/III trials and eight did not mention trial phase. Study durations varied from 24 up to 52 weeks with several studies allowing for open-label extensions. In 33 studies, patients had to have been on stable methotrexate for at least 12 weeks prior to entering the study, in four studies, this criterion was not required and in the rest of the studies, no information was reported. Sample sizes varied from less than 40 patients to more than 400 patients per randomised group. Rescue medication was permitted in 25 of the trials, not permitted in two trials and not reported in the remainder of the trials.

TNFi-IR studies

The TNFi-IR studies included seven phase III trials and one trial that did not mention the RCT phase (online supplementary table 2). Study duration varied from 24 up to 104 weeks. Sample sizes varied from 42 patients per arm to more than 200 patients per arm. Rescue medication was allowed in five of the trials and not reported in the remainder of the trials. Overall, eight studies reported ACR20/50/70 and HAQ-DI at 24 weeks (respectively) and were included in the NMA; the others included different endpoints that were not evaluated in this NMA.

Base case NMA results

NMA results for the csDMARD-IR and TNFi-IR populations are shown in tables 3 and 4 versus csDMARDs in the csDMARD-IR population, and superior efficacy was observed for sarilumab 200 mg and sarilumab 150 mg on all outcomes (table 3). Sarilumab 200 mg showed superior efficacy versus baricitinib 2 mg, tofacitinib and certolizumab combinations on 24 week mTSS, and similar efficacy versus baricitinib 4 mg, adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab and tocilizumab combinations (all doses) on all other outcomes. Sarilumab 150 mg showed similar efficacy to all lower doses of targeted DMARD combinations on all outcomes. Rates of SI/SAE were similar for sarilumab 150 mg and sarilumab 200 mg versus all comparators in csDMARD-IR.

Table 3.

Summary results for sarilumab 200 mg q2w combination vs other DMARD combinations in the csDMARD-IR population: median estimates of relative treatment effects (95% credible intervals) (base case) for week 24 efficacy and week 52 mTSS and safety (SI, SAE)

| Sarilumab 200 mg+csDMARD combination vs | ACR20 OR rREM (DIC=671.68) |

ACR50 OR rREM (DIC=632.99) |

ACR70 OR rREM (DIC=560.94) |

DAS28<2.6 OR rREM (DIC=427.34) | HAQ CFB diff REM (DIC=–133.71) |

mTSS 24 week CFB diff FEM (DIC=49.51) | mTSS 52 week CFB diff FEM (DIC=17.72) | SI 52 week RD REM (DIC=–44.23) |

SAE 52 week OR REM (DIC=140.50) |

| csDMARDs+placebo |

4.45

(2.43 to 8.25) |

5.14

(2.82 to 9.7) |

7.32

(3.03 to 20.69) |

7.88

(4.35 to 15.81) |

–0.25

(–0.36 to –0.141) |

–1.091

(–1.601 to –0.575) |

–2.53

(–3.42 to –1.65) |

0.012 (–0.151 to 0.178) |

2.31 (0.57 to 9.46) |

| csDMARDs+: | |||||||||

| Abatacept | 1.04 (0.52 to 2.03) |

1.14 (0.58 to 2.25) |

1.15 (0.43 to 3.29) |

1.37 (0.67 to 2.94) |

0.01 (–0.156 to 0.177) |

– | –0.13 (–1.73 to 1.44) |

0.004 (–0.178 to 0.202) |

2.61 (0.56 to 13.63) |

| Baricitinib 2 mg | 1.38 (0.61 to 3.15) |

1.56 (0.7 to 3.6) |

1.21 (0.39 to 4.19) |

1.33 (0.63 to 3.15) |

–0.003 (–0.181 to 0.175) |

–0.721

(–1.353 to –0.087) |

– | – | – |

| Baricitinib 4 mg | 0.9 (0.43 to 1.87) |

0.97 (0.46 to 1.95) |

0.83 (0.28 to 2.4) |

0.97 (0.48 to 2.04) |

0.053 (–0.11 to 0.219) |

–0.541 (–1.236 to 0.155) |

– | – | – |

| Tofacitinib | 1.69 (0.85 to 3.36) |

1.3 (0.66 to 2.66) |

1.07 (0.38 to 3.42) |

2 (0.94 to 4.71) |

0.037 (–0.102 to 0.177) |

–0.739

(–1.357 to –0.122) |

– | – | – |

| Adalimumab | 1.26 (0.66 to 2.42) |

1.17 (0.61 to 2.24) |

1.28 (0.5 to 3.55) |

1.27 (0.66 to 2.94) |

0.016 (–0.12 to 0.144) |

–0.082 (–0.848 to 0.684) |

0.07 (–1.39 to 1.49) |

–0.017 (–0.221 to 0.192) |

2.91 (0.37 to 26.5) |

| Certolizumab | 1.23 (0.58 to 2.68) |

1.18 (0.57 to 2.66) |

1.28 (0.44 to 4.75) |

1.24 (0.49 to 3.22) |

0.066 (–0.073 to 0.198) |

–0.906

(–1.637 to –0.178) |

–0.14 (–1.54 to 1.26) |

–0.018 (–0.250 to 0.212) |

1.02 (0.13 to 7.78) |

| Etanercept | 0.64 (0.24 to 1.67) |

0.7 (0.26 to 1.83) |

0.61 (0.09 to 2.99) |

0.4 (0.15 to 1.03) |

0.204 (–0.181 to 0.604) |

– | –1.24 (–3.09 to 0.63) |

– | – |

| Golimumab | 1.19 (0.59 to 2.37) |

1.39 (0.7 to 2.84) |

1.29 (0.48 to 4.03) |

1.43 (0.72 to 2.94) |

0.088 (–0.045 to 0.22) |

0.011 (–0.676 to 0.706) |

– | – | – |

| Infliximab | 1.41 (0.7 to 2.88) |

1.4 (0.67 to 3.01) |

1.3 (0.44 to 3.93) |

1.39 (0.67 to 3) |

0.165 (–1.451 to 1.907) |

– | – | –0.021 (–0.219 to 0.198) |

2.03 (0.35 to 12.43) |

| Tocilizumab 4 mg/kg intravenously | 1.93 (0.92 to 4.1) |

1.81 (0.87 to 3.96) |

1.8 (0.61 to 6.44) |

1.31 (0.58 to 3.14) |

–0.052 (–0.22 to 0.115) |

– | – | – | – |

| Tocilizumab 8 mg/kg intravenously | 1.48 (0.75 to 2.94) |

1.25 (0.64 to 2.57) |

1.18 (0.44 to 3.8) |

0.54 (0.26 to 1.19) |

–0.003 (–0.153 to 0.142) |

– | – | – | – |

| Tocilizumab SC 162 mg q1w | 1.63 (0.66 to 4.09) |

1.3 (0.54 to 3.37) |

1.37 (0.38 to 6.21) |

0.49 (0.2 to 1.34) |

– | – | – | – | – |

| Tocilizumab SC 162 mg q2w | 1.24 (0.53 to 2.93) |

1.07 (0.46 to 2.61) |

1.16 (0.34 to 4.32) |

0.64 (0.25 to 1.7) |

– | –0.477 (–1.182 to 0.223) |

– | – | – |

| Rituximab | 1.58 (0.78 to 3.16) |

1.65 (0.82 to 3.41) |

1.63 (0.57 to 5) |

2.32 (0.73 to 7.42) |

0.048 (–0.2 to 0.3) |

– | – | –0.037 (–0.276 to 0.200) |

2.57 (0.38 to 18.05) |

| Sarilumab 150 mg | 1.440 (0.76 to 2.69) |

1.43 (0.77 to 2.68) |

1.34 (0.54 to 3.33) |

1.35 (0.73 to 2.48) |

–0.01 (–0.119 to 0.098) |

–0.41 (–0.828 to 0.008) |

–0.65

(–1.29 to –0.01) |

0.010 (–0.153 to 0.174) |

1.26 (0.32 to 5.00) |

Models: ACR response and DAS28<2.6 using network meta-analyses with baseline risk rREM; HAQ using CFB with REM; Van der Heijde mTSS using mean CFB with FEM; SI using RD with REM; SAEs using logit model (OR) with REM; Italic text: in favour of sarilumab 200 mg combination; roman text: two treatment options are comparable.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CFB, change from baseline; DAS, Disease Activity Score; DIC, deviance information criterion; FEM, fixed-effects model; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; IR, inadequate response; MTX, methotrexate; RD, risk difference; SAEs, serious adverse events; SC, subcutaneous; SI, serious infections; csDMARD, conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; diff, difference; mTSS, modified total sharp score; rRAM, regression with random effects model.

Table 4.

Summary results for sarilumab 200 mg q2w combinations vs other combinations in the TNFi-IR population: median estimates of relative treatment effects (95% credible intervals) (base case) for week 24 efficacy and safety (SI, SAE)

| Sarilumab 200 mg+csDMARD combination vs: | ACR20 RD FEM (DIC=–25.55) |

ACR50 RD FEM (DIC=–35.76) |

ACR70 RD FEM (DIC=–36.14) |

DAS28<2.6 RD FEM (DIC=–36.30) |

HAQ CFB diff FEM (DIC=–55.78) |

SI 24 week OR FEM (DIC=78.37) |

SAE 24 week OR FEM (DIC=128.27) |

| csDMARDs+placebo |

0.272

(0.173 to 0.371) |

0.225

(0.135 to 0.316) |

0.091

(0.026 to 0.157) |

0.216

(0.141 to 0.292) |

−

0.241

( − 0.376 to − 0.102 ) |

0.97 (0.1 to 9.4) |

1.72 (0.61 to 5.23) |

| csDMARDs+: | |||||||

| Abatacept | −0.036 (−0.17 to 0.098) |

0.06 (−0.048 to 0.168) |

0.005 (−0.073 to 0.082) |

0.122

(0.037 to 0.208) |

0.081 (−0.083 to 0.245) |

0.88 (0.06 to 12.83) |

1.85 (0.54 to 6.77) |

| Baricitinib 2 mg combi | 0.096 (−0.043 to 0.236) |

0.126

(0.006 to 0.248) |

−0.007 (−0.093 to 0.08) |

0.169

(0.074 to 0.265) |

−0.01 (−0.217 to 0.198) |

1.24 (0.09 to 18.36) |

3.38 (0.83 to 14.96) |

| Baricitinib 4 mg combi | 0.081 (−0.058 to 0.221) |

0.063 (−0.061 to 0.186) |

−0.044 (−0.133 to 0.046) |

0.058 (−0.045 to 0.161) | 0.04 (−0.167 to 0.248) |

0.8 (0.06 to 10.76) |

1.2 (0.33 to 4.56) |

| Golimumab combi | 0.1 (−0.038 to 0.237) |

0.094 (−0.021 to 0.209) |

0.006 (−0.081 to 0.094) |

0.138

(0.044 to 0.231) |

−0.03 (−0.206 to 0.146) |

0.96 (0.07 to 13.14) |

2.4 (0.64 to 9.48) |

| Tocilizumab 4 mg/kg intravenous combi | 0.069 (−0.062 to 0.199) |

0.096 (−0.016 to 0.207) |

0.054 (−0.021 to 0.13) |

0.161

(0.072 to 0.249) |

0.02 (−0.165 to 0.206) |

1.8 (0.12 to 28.59) |

2.78 (0.77 to 10.83) |

| Tocilizumab 8 mg/kg intravenous combi | −0.127 (−0.26 to 0.006) |

−0.025 (−0.142 to 0.092) |

−0.019 (−0.103 to 0.064) |

−0.065 (−0.169 to 0.04) |

0.099 (−0.086 to 0.286) |

0.64 (0.05 to 8.03) |

3.31 (0.9 to 12.98) |

| Rituximab combi | −0.059 (−0.185 to 0.066) |

0.007 (−0.101 to 0.114) |

−0.019 (−0.096 to 0.057) |

0.126

(0.043 to 0.208) |

0.073 (−0.083 to 0.232) |

0.56 (0.04 to 7.91) |

2.38 (0.71 to 8.47) |

| Sarilumab 150 mg combi | 0.051 (−0.051 to 0.153) |

0.037 (−0.063 to 0.138) |

−0.036 (−0.114 to 0.043) |

0.04 (−0.051 to 0.13) |

−0.06 (−0.194 to 0.075) |

2.38 (0.18 to 78.26) |

1.72 (0.62 to 5.24) |

Models: ACR response and DAS28 <2.6 using RD model with fixed effects (FEM); HAQ using CFB model with FEM; SI and SAE using logit model (OR) with FEM; italic text: in favour of sarilumab 200 mg combination; roman text: two treatment options are comparable.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CFB, change from baseline; Combi, combination; DAS, Disease Activity Score; DIC, deviance information criterion; FEM, fixed-effects model; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; IR, inadequate response; MTX, methotrexate; RD, risk difference; SAEs, serious adverse events; SC, subcutaneous; SI, serious infections; csDMARD, conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; diff, difference; mTSS, modified total sharp score; rRAM, regression with random effects model.

In the TNFi-IR population (table 4), superior efficacy was observed for sarilumab 200 mg versus baricitinib 2 mg combination on ACR50 and DAS28<2.6 and versus abatacept, golimumab, tocilizumab 4 mg/kg IV and rituximab combinations on DAS28<2.6. On ACR20/50/70, similar efficacy was observed for sarilumab 200 mg compared with abatacept, golimumab, tocilizumab 4 mg and 8 mg/kg IV and rituximab combinations. Sarilumab 150 mg had superior efficacy versus baricitinib 2 mg and rituximab combinations on DAS28<2.6, similar efficacy to all other bDMARD combinations (all lowest approved dose) on all outcomes and similar efficacy to tocilizumab 4 mg on ACR70; however, efficacy was lower versus tocilizumab 8 mg on ACR20 and DAS28 remission. SAEs, including SIs, appeared similar for sarilumab 200 mg and 150 mg versus all comparators.

Scenario analyses

In the csDMARD-IR scenario, which excluded six studies assessing Asian patients only, results were similar to the ACR20/50 base cases for sarilumab 200 mg against all comparators. However, sarilumab 200 mg was superior to tocilizumab IV 4 mg/kg combination for ACR70. For the scenario that included the ATTRACT and SWEFOT studies, sarilumab 200 mg combination therapy showed superiority to csDMARD and sarilumab 150 mg combination for mTSS at 52 weeks, and inferiority to infliximab combination in the fixed-effects model. In the random-effects model, sarilumab 200 mg combination was comparable to all treatments. The scenario that pooled all 13 TNFi treatment interventions from the 43 studies included in the csDMARD-IR network, sarilumab 200 mg combination therapy was found to be superior to csDMARDs and comparable to all other combination therapies. The scenario in the TNFi-IR population excluding the GO-AFTER study obtained results consistent with the base case for sarilumab 200 mg against all the comparators except for golimumab combination on ACR20/70.

Discussion

Active comparator controlled, randomised trials evaluating the comparative efficacy and safety of bDMARDs or tsDMARDs are few and limited to adalimumab as an active comparator.4 25–29 In the absence of head-to-head trial evidence, indirect comparison through a NMA provides best estimates of comparative efficacy. NMA also provides fully conditional estimates of relative treatment effect. This NMA was undertaken to compare sarilumab versus relevant csDMARD, bDMARD and tsDMARD comparators in csDMARD-IR and TNFi-IR adult RA patient populations.

In the csDMARD-IR network, sarilumab showed significantly better efficacy versus csDMARDs, consistent with the head-to-head evidence from MOBILITY-B, and similar efficacy and safety to combination therapies including all licensed biologics, and the tsDMARDs tofacitinib and baricitinib. Typically, safety outcomes presented broad credible intervals due to their relatively low occurrence.

Sarilumab showed significantly better efficacy versus csDMARD in the TNFi-IR population, consistent with the head-to-head evidence from TARGET and comparable efficacy and safety to other biological regimens for most outcomes. Both doses of sarilumab showed favourable outcomes on ACR50 and on DAS28 remission in the TNFi-IR population compared with combination therapies with baricitinib and tocilizumab and all other bDMARDs and tofacitinib.

Strengths and limitations

There are considerable challenges in undertaking an NMA when there is heterogeneity in the placebo arms across trials. Variability in placebo response was observed across both csDMARD-IR and TNFi-IR networks. Some degree of variation in patient characteristics across studies is an inevitable feature of the RA evidence base given the evolution of clinical trial design and patient populations over the 20-year period since the first biological trials. Furthermore, geographic location may be another potential confounding factor in RA clinical trials. There are also key differences in the inclusion/exclusion of studies. If these characteristics are effect modifiers of the relative treatment effects of interest, the heterogeneity of the evidence base15 23 30 can limit the validity of indirect comparisons. Therefore, a scenario analysis was conducted to test weight as a potential modifier.

In addition, a high level of heterogeneity of response in the placebo arms of studies (ie, placebo+csDMARDs in combination studies) has been previously noted by NICE, using certolizumab pegol in RA as an example,19 where the treatment effect expressed as log ORs had a negative relationship with the baseline risk.14 24 This is an issue that can particularly limit indirect comparisons. One explanation for heterogeneity in placebo arms of recent studies may be that more recent trials in RA have included larger proportions of patients from the Latin American region, whereas earlier trials included a higher proportion of patients from North America and Western Europe. For the Latin American region, higher response rates in RA have been noted by NICE in the placebo arm as well as the active arm, compared with other regions.19 This phenomenon was also observed in the phase III MOBILITY and TARGET trials for sarilumab and other RA trials, including the GO-FORWARD trial of golimumab and the tocilizumab trials. Several reasons could account for regional variation, including differences in background and prior care, differences in patient conceptualisation of PRO components of outcome measures and differences in physician approach to practice. In the present study, variation in the placebo responses across studies were addressed by applying alternative analytical methods. We attempted to address this issue within the NMA methodology, as baseline risk regression has been suggested as a solution to this and has been previously used in RA.19 20 31 It performs well when there is a large number of trials in a network, as in the csDMARD-IR population.

An additional challenge was met for the smaller TNFi-IR network. While sparse data preclude a number of analytic options, including meta-regression, NMA on risk difference is a promising strategy to address this limitation.14 The TNF-IR outcome networks were small (with at most seven studies) and it was therefore difficult to obtain model convergence and precise estimation by following the REM approach. To address this issue, less vague priors were used: (1) for relative treatment effect, called log-odds (under the belief of OR=(0,500), d~Normal (0,10)) and study effect (under the belief of p=(0.005, 0.995), mu~Normal (0,10)) based on the work of Spiegelhalter and colleagues for coefficient of regression.32 Therefore, it was estimated from BR of ACR20/50/70 in csDMARD-IR with variance less than 1 (SD=(0.13;0.85)) and with the mean of 0 in order to give the chance for both negative and positive sides: B~Normal (0,1), between study SD also decreased gradually in uniform distribution. However, even with informative priors, very wide credible intervals were obtained; BR-NMA results for the TNF-IR population were highly uncertain (eg, OR of ACR20 of sarilumab 200 mg combination versus csDMARDs observed in the TARGET trial was 3.28 with 95% CI 2.11, 5.12, while the NMA regression result was 2.50 with 95% CI 0.82, 6.78).

Thus, in the present NMA, the RD-NMA models worked well, even in a situation with few studies or in the case of rare events (eg, SI or SAE) and predicted data well, with a higher degree of certainty than the BR-NMA. We confirmed the reliability of this approach by reconducting analyses for the ACR20/50/70 networks using a probit random-effect model and informative priors19 20 31 for the between-study variance (log normal with mean −2.56 and variance of 1.74*1.74, proposed by Turner et al (2012),33 and results were consistent with RD-NMA models.

Finally, we faced a situation whereby different dosing regimens for some drugs were evaluated across studies. To solve this issue, the authors first assessed the overlapping of CIs of the individual studies. In most cases, there was overlap, therefore, these studies were pooled, and the validity of this approach was justified via clinical input. However, in the one case where there was no overlap, tocilizumab 25 mg two times a week versus tocilizumab 50 mg once a week, clinical input informed the decision to pool these comparable regimens.

The robustness of this NMA derives from exploration and application of rigorous methods to account for heterogeneity and also inclusion of up to date evidence including new bDMARDs sarilumab and the tsDMARD baricitinib. A range of efficacy and safety outcomes also provided a comprehensive picture of comparative efficacy and safety of sarilumab in the csDMARD-IR and TNFi-IR populations, to inform clinical decision-making and conduct of health technology assessments. The most robust networks, ACR20/50, used only one common comparator on all comparisons with sarilumab on these endpoints. Moreover, there was no major concern of inconsistencies given that the appropriate models were implemented; so, for outcomes with plentiful studies, as in the csDMARD-IR population, the results were considered robust. Four scenario analyses confirmed the results against the base case analysis, where comparisons were feasible.

Many NMAs have been published in RA, which differed in their precise aims, inclusion criteria, analyses performed and results. Thorlund and colleagues34 reviewed 13 published NMAs and despite similar stated eligibility criteria and objectives, found differences in the estimated treatment effects, the inclusion of trials, analytic approaches and endpoints evaluated. For example, some studies report DAS28-ESR and others report DAS28-CRP. In the present NMA, we examined both outcomes, although the variability in outcome definition may have impacted the DAS28 results and so it may not be appropriate to compare fully the results of this NMA with previously published NMAs. However, published NMAs have shown similar efficacy and safety between different biological drugs for the majority of comparisons14 34 and the results of the present NMA for those biologics are in line with these findings.

In the present NMA, there were limitations to the conclusions that could be made for the efficacy of sarilumab versus use of a further TNFi in TNFi-IR patients due to the very limited evidence base. The only trial that could be included was the GO-AFTER trial, in which only ~58% patients had failed their previous TNFi because of lack of efficacy. This percentage is lower than the other included studies in which almost 100% of patients had failed a previous TNFi due to lack of efficacy (eg, TARGET, 92.3%). Therefore, the conclusions regarding the relative efficacy and safety of sarilumab (or other non-TNFis) versus TNFis in TNFi-IR patients should be interpreted with caution.

Nonetheless, this NMA was conducted following best practice guidelines and demonstrated that sarilumab SC at both 150 mg and 200 mg doses in combination with csDMARDs or methotrexate has superior efficacy compared with csDMARDs alone and comparable or better efficacy compared with other biological and targeted synthetic combination therapies in both csDMARD-IR and TNFi-IR patient populations. Sarilumab 150 mg and 200 mg had parity efficacy and safety to tocilizumab 4 mg and 8 mg/kg intravenously. SAEs including SIs appeared similar for sarilumab 150 mg and 200 mg versus all comparators.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Parexel for conducting the literature searches and analyses. Medical writing assistance and editorial support, under the direction of the authors, were respectively provided by Gauri Saal, MA Economics, and Sinead Stewart, both of Prime (Knutsford, UK), funded by Sanofi/Regeneron Pharmaceuticals according to Good Publication Practice guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3). The Sponsor was involved in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data as well as data checking of information provided in the manuscript. The authors had unrestricted access to study data, were responsible for all content and editorial decisions and received no honoraria related to the development of this publication.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Competing interests: EC has received research grants, consultancy and speaker fees from Amgen, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Chugai Pharma, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novimmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, R-Pharm, Sanofi, Tonix and UCB. T-M-TH, LP, HvH and PC are employees of Sanofi and hold stock and/or stock options in the company. CP is a former employee of and current shareholder in Sanofi and current employee of Novartis. C-IC, AK and EM are employees of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and hold stock and/or stock options in the company. NF has received consulting fees from Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, Ipsen, Allergan, Takeda, Biogen, Abbvie, Lifecell.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No associated data will be shared.

References

- 1. Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, et al. . 2015 American College of rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1–26. 10.1002/art.39480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al. . EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:960–77. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Genovese MC, Fleischmann R, Kivitz AJ, et al. . Sarilumab plus methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate: results of a phase III study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:1424–37. 10.1002/art.39093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burmester GR, Lin Y, Patel R, et al. . Efficacy and safety of sarilumab monotherapy versus adalimumab monotherapy for the treatment of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (MONARCH): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group phase III trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:840–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Strand V, Kosinski M, Chen CI, et al. . Sarilumab plus methotrexate improves patient-reported outcomes in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate responses to methotrexate: results of a phase III trial. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:198 10.1186/s13075-016-1096-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fleischmann R, van Adelsberg J, Lin Y, et al. . Sarilumab and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response or intolerance to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:277–90. 10.1002/art.39944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Epstein D. The use of comparative effectiveness research and health Technology assessment in European countries: current situation and prospects for the future, 2014. Available: www.ugr.es/~davidepstein/HTA%20in%20european%20countries.docx [Accessed 27 Feb 2017].

- 8. Sorenson C, Naci H, Cylus J, et al. . Evidence of comparative efficacy should have a formal role in European drug approvals. BMJ 2011;343:d4849 10.1136/bmj.d4849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schottker B, Luhmann D, Boulkhemair D, et al. . Indirect comparisons of therapeutic interventions. GMS Health Technol Assess 2009;5:Doc09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. EUnetHTA – European network for Health Technology Assessment Comparators and comparisons – direct and indirect comparisons, 2013. Available: http://www.eunethta.eu/sites/default/files/sites/5026.fedimbo.belgium.be/files/Direct%20and%20indirect%20comparisons.pdf [Accessed 27 Feb 2017].

- 11. Kiefer C, Sturtz S, Bender R. Indirect comparisons and network meta-analyses. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2015;112:803–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, et al. . The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:777–84. 10.7326/M14-2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013, 2013. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9/resources/guide-to-the-methods-of-technology-appraisal-2013-pdf-2007975843781 [Accessed 27 Feb 2017]. [PubMed]

- 14. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab and abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis not previously treated with DMARDs or after conventional DMARDs only have failed, 2016. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta375/resources/adalimumab-etanercept-infliximab-certolizumab-pegol-golimumab-tocilizumab-and-abatacept-for-rheumatoid-arthritis-not-previously-treated-with-dmards-or-after-conventional-dmards-only-have-failed-82602790920133 [Accessed 27 Feb 2017].

- 15. Hoaglin DC, Hawkins N, Jansen JP, et al. . Conducting indirect-treatment-comparison and network-meta-analysis studies: report of the ISPOR Task Force on indirect treatment comparisons good research practices: Part 2. Value Health 2011;14:429–37. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jansen JP, Fleurence R, Devine B, et al. . Interpreting indirect treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis for health-care decision making: report of the ISPOR Task Force on indirect treatment comparisons good research practices: Part 1. Value Health 2011;14:417–28. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nüesch E, Trelle S, Reichenbach S, et al. . Small study effects in meta-analyses of osteoarthritis trials: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2010;341:c3515 10.1136/bmj.c3515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sedgwick P, Marston L. Meta-analyses: standardised mean differences. BMJ 2013;347:f7257–347. 10.1136/bmj.f7257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dias S, Sutton AJ, Welton NJ. NICE dsu technical support document 3: heterogeneity: subgroups, meta-regression, bias and bias-adjustment, 2011. Available: http://www.nicedsu.org.uk/TSD3%20Heterogeneity.final%20report.08.05.12.pdf [Accessed 27 Feb 2017].

- 20. Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ. NICE dsu technical support document 2: a generalised linear modelling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials, 2011. Available: http://www.nicedsu.org.uk/TSD2%20General%20meta%20analysis%20corrected%202Sep2016v2.pdf [Accessed 27 Feb 2017]. [PubMed]

- 21. Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, et al. . Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J Royal Statistical Soc B 2002;64:583–639. 10.1111/1467-9868.00353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Caldwell DM, Ades AE, Higgins JP. Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ 2005;331:897–900. 10.1136/bmj.331.7521.897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lu G, Ades AE. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Stat Med 2004;23:3105–24. 10.1002/sim.1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Machado DA, Guzman RM, Xavier RM, et al. . Open-label observation of addition of etanercept versus a conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug in subjects with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy in the Latin American region. J Clin Rheumatol 2014;20:25–33. 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weinblatt ME, Schiff M, Valente R, et al. . Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a phase IIIB, multinational, prospective, randomized study. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:28–38. 10.1002/art.37711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gabay C, Emery P, van Vollenhoven R, et al. . Tocilizumab monotherapy versus adalimumab monotherapy for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (ADACTA): a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase 4 trial. Lancet 2013;381:1541–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60250-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schiff M, Weinblatt ME, Valente R, et al. . Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: two-year efficacy and safety findings from AMPLE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:86–94. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Vollenhoven RF, Fleischmann R, Cohen S. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. [Erratum appears in N Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 18;369(3):293]. N Engl J Med 2012;367:508–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taylor PC, Keystone EC, van der Heijde D, et al. . Baricitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2017;376:652–62. 10.1056/NEJMoa1608345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, et al. . The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:683–91. 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00049-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review Targeted immune modulators for rheumatoid arthritis: effectiveness & value. Evidence report 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith TC, Spiegelhalter DJ, Thomas A. Bayesian approaches to random-effects meta-analysis: a comparative study. Statist. Med. 1995;14:2685–99. 10.1002/sim.4780142408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Turner RM, Davey J, Clarke MJ, et al. . Predicting the extent of heterogeneity in meta-analysis, using empirical data from the Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:818–27. 10.1093/ije/dys041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thorlund K, Druyts E, Aviña-Zubieta JA, et al. . Why the findings of published multiple treatment comparison meta-analyses of biologic treatments for rheumatoid arthritis are different: an overview of recurrent methodological shortcomings. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1524–35. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li Z, Zhang F, Kay J. Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous golimumab in Chinese patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite MTX therapy: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:S598–S99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Keystone EC, Kavanaugh AF, Sharp JT, et al. . Radiographic, clinical, and functional outcomes of treatment with adalimumab (a human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis receiving concomitant methotrexate therapy: a randomized, placebo-controlled, 52-week trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:1400–11. 10.1002/art.20217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Keystone EC, Kavanaugh A, Weinblatt ME, et al. . Clinical consequences of delayed addition of adalimumab to methotrexate therapy over 5 years in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2011;38:855–62. 10.3899/jrheum.100752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Keystone E, Genovese MC, Hall S, et al. . AB0267 Five-year safety and efficacy of golimumab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite prior treatment with methotrexate: final study results of the phase 3, randomized placebo-controlled go-forward trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72(Suppl 3):A867.3–A868. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-eular.2589 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Combe B, Codreanu C, Fiocco U, et al. . Etanercept and sulfasalazine, alone and combined, in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite receiving sulfasalazine: a double-blind comparison. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1357–62. 10.1136/ard.2005.049650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim HY, Lee SK, Song YW, et al. . A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study of the human anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody adalimumab administered as subcutaneous injections in Korean rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with methotrexate. APLAR J Rheumatol 2007;10:9–16. 10.1111/j.1479-8077.2007.00248.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tanaka Y, Harigai M, Takeuchi T, et al. . Golimumab in combination with methotrexate in Japanese patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of the GO-FORTH study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:817–24. 10.1136/ard.2011.200317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Takeuchi T, Kaneko Y, Atsumi T, et al. . OP0040 adding tocilizumab or switching to tocilizumab monotherapy in RA patients with inadequate response to methotrexate: 24-week results from a randomized controlled study (Surprise Study). Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72(Suppl 3):A62–A63. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-eular.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yamamoto K, Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, et al. . Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol without methotrexate co-administration in Japanese patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: the HIKARI randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Mod Rheumatol 2014;24:552–60. 10.3109/14397595.2013.843764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yamamoto K, Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, et al. . Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate: the J-RAPID randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Mod Rheumatol 2014;24:715–24. 10.3109/14397595.2013.864224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yamanaka H, Nagaoka S, Lee SK, et al. . Discontinuation of etanercept after achievement of sustained remission in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who initially had moderate disease activity-results from the encourage study, a prospective, international, multicenter randomized study. Mod Rheumatol 2016;26:651–61. 10.3109/14397595.2015.1123349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Manders SH, Kievit W, Adang E, et al. . Effectiveness of TNF inhibitor treatment with various methotrexate doses in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:e24 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2018-000798supp001.htm (163.6KB, htm)