Significance

An incredible diversity of microbial species inhabit the Earth. Many new interactions of bacteria with animals are only beginning to surface. We show that feeding a worm, Caenorhabditis elegans, with Rhizobium bacteria causes failed nuclear divisions in intestinal cells. C. elegans mutations compromising DNA damage repair pathways and exogenous reactive oxygen species cause similar failure in intestinal nuclear divisions, suggesting that Rhizobium may produce reactive oxygen species. In accordance, free radical scavenger chemicals suppress the response to Rhizobium. We propose that Rhizobium induces reactive oxygen species in its encounter with C. elegans. Our findings provide an insight into the interactions between microbes and animal cells.

Keywords: C. elegans, microbiota, DNA damage, ROS, Rhizobium

Abstract

In their natural habitat of rotting fruit, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans feeds on the complex bacterial communities that thrive in this rich growth medium. Hundreds of diverse bacterial strains cultured from such rotting fruit allow C. elegans growth and reproduction when tested individually. In screens for C. elegans responses to single bacterial strains associated with nematodes in fruit, we found that Rhizobium causes a genome instability phenotype; we observed abnormally long or fragmented intestinal nuclei due to aberrant nuclear division, or defective karyokinesis. The karyokinesis defects were restricted to intestinal cells and required close proximity between bacteria and the worm. A genetic screen for C. elegans mutations that cause the same intestinal karyokinesis defect followed by genome sequencing of the isolated mutant strains identified mutations that disrupt DNA damage repair pathways, suggesting that Rhizobium may cause DNA damage in C. elegans intestinal cells. We hypothesized that such DNA damage is caused by reactive oxygen species produced by Rhizobium and found that hydrogen peroxide added to benign Escherichia coli can cause the same intestinal karyokinesis defects in WT C. elegans. Supporting this model, free radical scavengers suppressed the Rhizobium-induced C. elegans DNA damage. Thus, Rhizobium may signal to eukaryotic hosts via reactive oxygen species, and the host may respond with DNA damage repair pathways.

The free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans in the laboratory feeds on Escherichia coli. Cultivation of C. elegans on a diet of E. coli was natural for the E. coli geneticists who were the pioneers of C. elegans research. But the native habitat of C. elegans is not the laboratory, and, until recently, very little was known about its natural history (1–6). For many years, C. elegans has been called a soil nematode, which now appears to be inaccurate. In geographically diverse areas, C. elegans inhabits decaying plants and fruits, which fuel the proliferation of diverse species of bacteria which C. elegans finds scrumptious (5, 7). Félix and coworkers have systematically characterized the bacterial species that can be cultured from the same decaying fruits that foster the growth of C. elegans and other nematodes (5, 7). The potential influence on C. elegans of these bacterial species, either individually or in reconstructed communities of bacteria, has begun to emerge (8).

Here, we show that particular species of bacteria from the C. elegans natural habitat tested individually as the sole food source for C. elegans cultivation: For example, Rhizobium huautlense, inhibited normal karyokinesis during postembryonic intestinal development. Our analysis based on comprehensive C. elegans genetics screens, and free radical exposure or free radical scavenger treatments, show that Rhizobium produces reactive oxygen species (ROS), which induces DNA damage in the animal intestine to in turn cause defective karyokinesis. This ROS damage is likely to cause the formation of chromosome bridges preventing the proper separation of nuclei after a cell cycle. Chemical free radical scavengers can partially suppress this Rhizobium-induced DNA damage. Chemical addition of reactive oxygen to an otherwise benign E. coli bacteria also induced such an aberrant nuclear division. Our findings provide an insight into the interactions between microbes and animal cells.

Results and Discussion

Feeding C. elegans on Particular Strains of Bacteria Cultured from Its Natural Habitat Causes Abnormal Intestinal Nuclei Divisions.

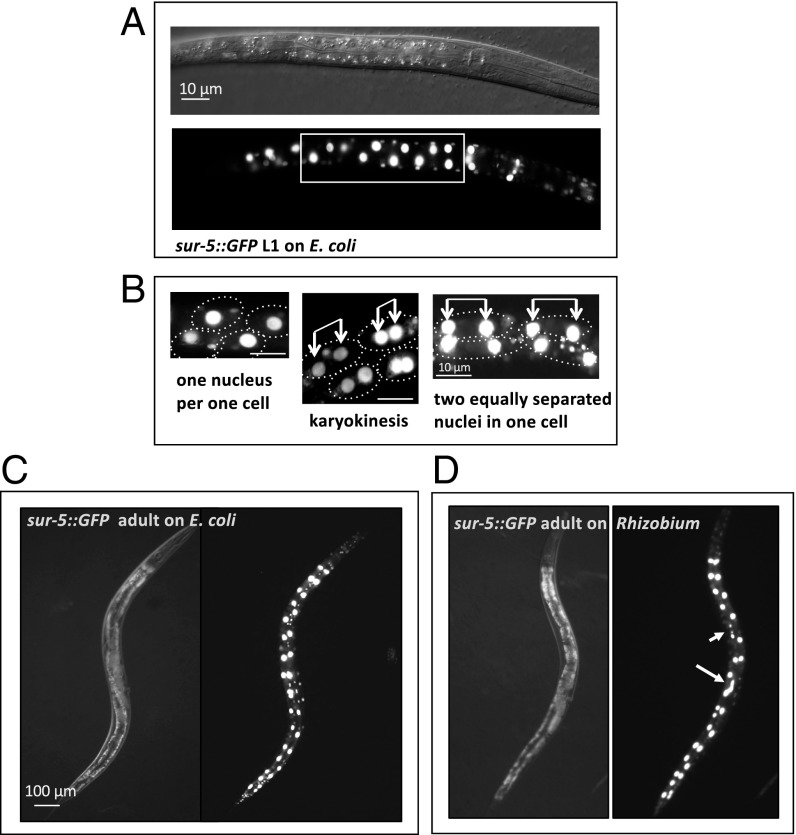

In the laboratory, C. elegans is often cultivated on a diet of E. coli (OP50 strain) bacteria grown from a few drops of a saturated liquid overnight culture, which is spotted on nematode growth media agar plates (NGM-plates). We cultivated C. elegans on individual bacterial species isolated from the C. elegans natural habitat of rotting fruit (3, 4, 9) instead of E. coli and tested whether any of these strains induce the expression of GFP fusion reporter genes associated with particular developmental milestones or with stress and immunity (8). We tested these reporter genes on a cultured collection of 90 species that coinhabit rotting fruits with C. elegans (the JUb bacterial library) (8) (Materials and Methods), which have been 16s rRNA gene sequenced for classification. A sur-5::GFP fusion gene (10), which expresses a nuclear-localized green fluorescent protein (GFP) in all somatic cells, allows many postembryonic cell divisions that occur during larval stages of C. elegans to be monitored. In C. elegans carrying the sur-5::GFP fusion cultivated on benign E. coli, bright GFP is observed in the intestine, where 20 large round intestinal nuclei line up in a regular pattern. The number and spatial distribution of these nuclei in larvae and adults is stereotyped. At the first larval (or L1) stage, larvae hatch with 20 mononucleated intestinal cells formed during embryogenesis, but, during the late L1 stage, a specific subset of 8 to 12 intestinal nuclei duplicate after DNA replication and divide, and these duplicated nuclei separate without cytokinesis (i.e., karyokinesis without cytokinesis), generating binucleate intestinal cells and totaling 28 to 32 nuclei by the end of the L1 stage (11) (Fig. 1 A–C). Feeding sur-5::GFP C. elegans with one bacterial strain at a time from the collection of 90 bacterial species revealed that representatives of Sphingobacterium, Pseudomonas, Providencia, Rhizobium, and other taxa change the shape and pattern of intestinal nuclei (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Table S1). Some intestinal nuclei were elongated or fragmented while the normally invariant separation between daughter nuclei became irregular when animals were fed on these taxa of bacteria (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Postembryonic development of C. elegans intestine: karyokinesis without cytokinesis during the L1 stage. (A) Differential interference contrast (DIC) and corresponding fluorescent images of early L1 larva with nuclei revealed by sur-5::GFP, which carries a nuclear localization sequence. A rectangle marks midintestinal cells that will become binucleate later during the L1 stage. (B) sur-5::GFP fluorescent images showing nuclei divisions and segregation within intestinal cells in late L1 larvae; dotted circles approximately show cell boundaries. Connected arrows point to recently divided cell nuclei. (C) DIC and fluorescent images of sur-5::GFP adult fed on E. coli from the time of hatching. (D) DIC and fluorescent images of a sur-5::GFP adult animal fed on Rhizobium from the time of hatching. Long and short arrows point to abnormally elongated and fragmented gut nuclei, respectively. On average, 78% of worms fed on Rhizobium have at least two instances of aberrant karyokinesis (elongated or fragmented nuclei or chromosomal bridges) whereas less than 10% have this phenotype on E. coli (n > 1,000).

For a detailed investigation of the unusual gut nuclei defect, we studied one of the wild bacteria isolates, a Rhizobium, which had the strongest karyokinesis defect (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Table S1). This Rhizobium species was identified with 16S rRNA gene sequencing as Rhizobium huautlense. Feeding C. elegans with other closely related Rhizobium species (R. huautlense, ATCCBAA-115; and Rhizobium galegae, ATCC43677) obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), as well as the closely related genus Agrobacterium, also showed similar intestinal karyokinesis defects, indicating that induction of an intestinal nuclear division defect is common to multiple members of the Agrobacterium/Rhizobium clade (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Table S1).

Feeding with Rhizobium Disrupts Karyokinesis During Larval Stage One Intestinal Nuclei Divisions.

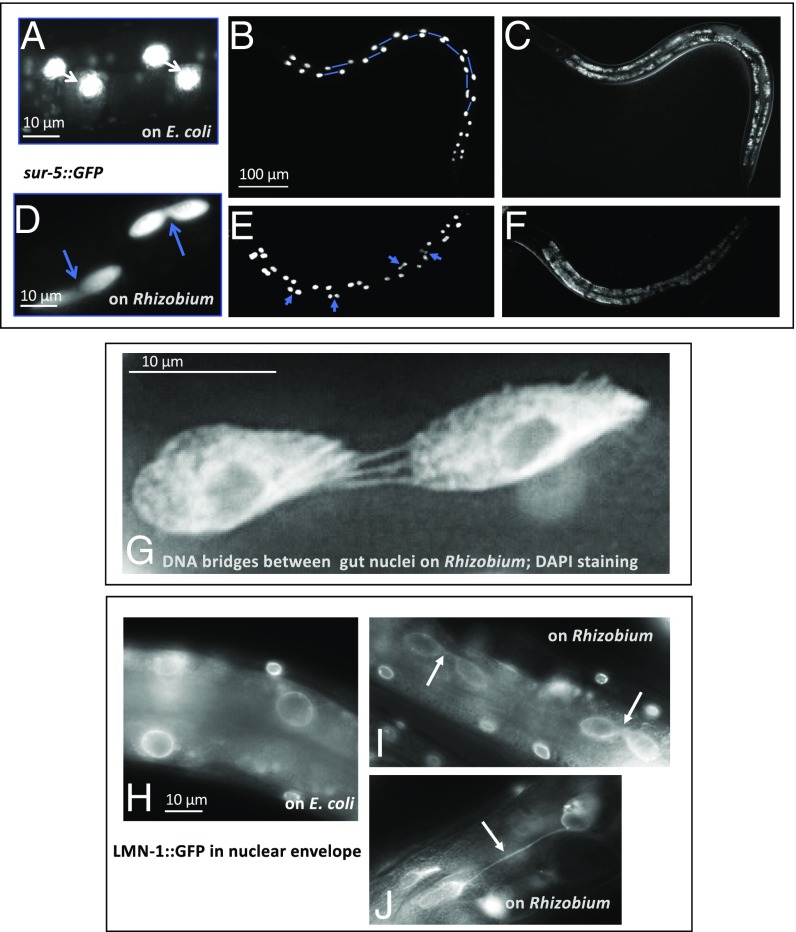

WT C. elegans larvae fed with E. coli underwent a programmed intestinal nuclear division during the late L1 stage. These nuclei divided and moved away from each other within a cell, creating an invariant regular pattern (Figs. 1B and 2 A–C). In contrast, in WT larvae fed on Rhizobium, intestinal nuclei divided, but often failed to separate. The doublets of nuclei could be easily seen in late larvae and adults (Fig. 2 D–F). In some cases, the divided nuclei separated but remained connected with DNA bridges (Fig. 2G) and encapsulated in the same nuclear envelope (Fig. 2 H–J). The intestinal nuclear defects of C. elegans grown on Rhizobium were observed in 78% of animals grown on Rhizobium (at least two pairs of abnormal nuclei) whereas, on E. coli, less than 10% of the animals showed this defect. Defective intestinal karyokinesis was observed in C. elegans fed on Rhizobium from the time of hatching. The defect in karyokinesis at the L1 stage was not cured at later stages and could be easily observed in adult intestinal cells with large polyploid nuclei. If initial feeding at the L1 stage was on E. coli and switched to Rhizobium at later stages (L2 to adults), the gut nuclei pattern remained normal. Thus, the exposure to Rhizobium was required before DNA replication and nuclear division of intestinal cells during the late L1 stage (12). To test for inheritance of the phenotype, parent animals grown on Rhizobium with abnormal intestinal karyokinesis were allowed to produce progeny animals that were then fed with E. coli from the time of hatching, and these progeny had normal intestinal nuclei. Thus, defective intestinal karyokinesis required an exposure to the causative bacteria at early L1 larvae, and it was not inherited.

Fig. 2.

In animals feeding on Rhizobium huautlense, intestinal nuclei divide normally during the L1 stage, but the nuclear envelopes fail to separate. (A–F) Fluorescent sur-5::GFP and differential interference contrast images illustrating a difference in gut nuclei segregation between C. elegans fed with E. coli (A–C) and R. huautlense (D–F). On E. coli, nuclei are evenly spaced within the binucleate intestinal cell (shown connected by lines). On Rhizobium, the failed segregation of nuclei is shown with arrows. (G) High magnification image of DAPI-stained nuclei showing multiple DNA bridges between incompletely separated intestinal nuclei in C. elegans fed with Rhizobium. (H) The divided intestinal nuclei highlighted by a nuclear lamin::GFP fusion protein in C. elegans fed with E. coli and nuclei failed in karyokinesis in C. elegans fed with Rhizobium (I and J). Arrows point to nuclei envelope bridges. Most of the affected animals had four to six abnormal gut nuclei randomly positioned along the intestine, out of 12 of the 20 gut cells that normally divide during the L1 stage.

Mutations in C. elegans DNA Damage Response Genes also Cause Abnormal Intestinal Karyokinesis.

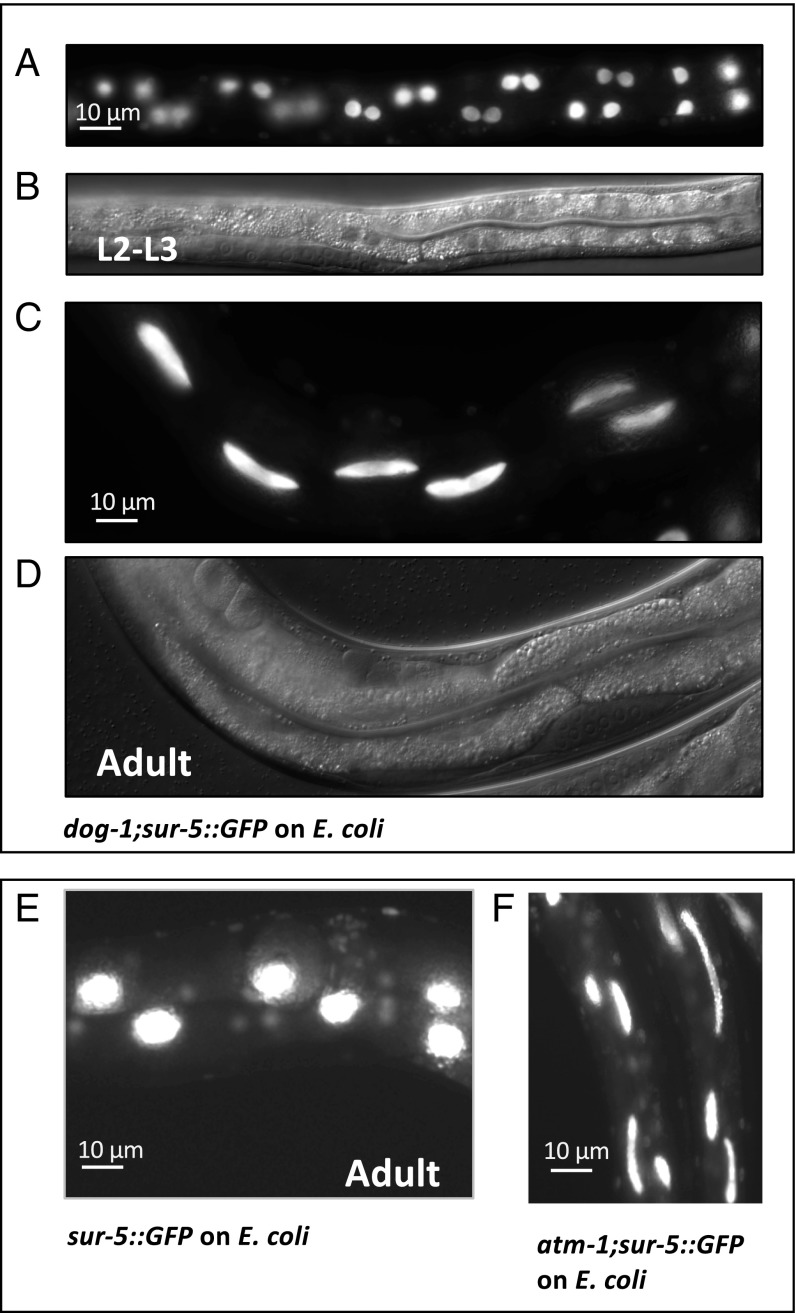

The occurrence of chromosomal bridges and fragmented nuclei is a hallmark of DNA damage and chromosome breakage (13, 14) and suggested that such DNA damage may occur in the gut nuclei of C. elegans fed on Rhizobium. To explore what C. elegans processes might be affected to cause the elongated and fragmented gut nuclei, and thus reveal the host pathways that Rhizobium might disrupt, we mutagenized the sur-5::GFP C. elegans with ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) (6) and screened two generations after the mutagenesis for C. elegans mutants that have elongated and fragmented gut phenotype when grown on benign E. coli (∼10,000 haploid genomes were screened). Using whole genome sequencing, we identified point mutations in coding regions of six mutants: atm-1 (C578T) and dog-1 (five alleles: G759A, G118A, G845A, C346T, and splice site donor C to T between exons 6 and 7) genes (Fig. 3 and Table 1). atm-1 encodes the C. elegans ortholog of ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase that responds to DNA damage by phosphorylating key substrates involved in DNA repair and/or cell cycle control, and dog-1 encodes the C. elegans ortholog of the helicase mutated in Fanconi anemia, also implicated in a DNA damage response. The atm-1 and dog-1 mutants frequently produced males, a phenotype often associated with DNA damage and aneuploidy, and were viable.

Fig. 3.

C. elegans strains with mutations in DNA damage response pathways grown on E. coli show the same defective nuclear division phenotype observed in WT C. elegans fed with Rhizobium huautlense. (A–D) Fluorescence and differential interference contrast sur-5::GFP images of C. elegans dog-1 mutant animals grown on E. coli illustrate failed intestinal nuclei segregation in L2-L3 larvae (A and B) resulting in “elongated” gut nuclei phenotype in adults (C and D). (E and F) Fluorescence images of gut nuclei patterning in sur-5::GFP (E) and the atm-1;sur-5::GFP adults (F) (one of the extreme cases). Intestinal karyokinesis is affected in 100% of atm-1;sur-5::GFP and dog-1;sur-5::GFP mutants fed with E. coli (SI Appendix, Table S1); other tissues were not evaluated.

Table 1.

Mutations in the listed genes alter karyokinesis in the C. elegans developing intestine

| Gene | Name | Cellular function | EMS mutation/ alleles | Amino acid change | CGC strains | C-test* | CGC strain gut nuclei abnormal | Human homolog |

| atm-1 | Ataxia telangiectasia mutated family | DDR | C578T | R/C | VC381 (gk186) | No | Yes | ATM |

| dog-1 | Deletion of G-rich DNA | DNA repair/ maintenance | G118A† | G/R | VC13 (gk10) | No | Yes | FANCJ/ BRIP1/ BACH1 |

| C15021247T position on chromosome I | Splice site donor | No | ||||||

| G759A | C/Y | n/t | ||||||

| G845A | G/D | |||||||

| C346T | P/S |

C-test, complementation test. “No” means that a cross between the EMS mutant and the corresponding CGC strain does not rescue the abnormal phenotype, indicating that the same gene is mutated in both strains.

Five alleles of dog-1 were isolated in the screen; two were evaluated in a C-test. n/t, not tested. Amino acid abbreviations: R, arginine; C, cysteine; G, glycine; Y, tyrosine; D, aspartic acid; P, proline; S, serine. Sources: https://wormbase.org/#012-34-5.

The following genetic data indicate that mutations in atm-1 and dog-1 genes cause the elongated gut nuclear phenotype: (i) Complementation tests between our isolated mutants and standard mutant alleles obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center (CGC) strain collection showed that the isolated atm-1 and dog-1 alleles failed to complement the standard atm-1 and dog-1 alleles, respectively; (ii) the standard CGC atm-1 and dog-1 mutations crossed with sur-5::GFP reporter showed a similar karyokinesis defect (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and Table S1); and (iii) multiple alleles of dog-1 came out of the screen.

In all of the isolated C. elegans mutants, the intestinal karyokinesis defect was stronger (most of the intestinal nuclei failed to separate) and more penetrant (100% of worms, n > 100 were affected) (SI Appendix, Table S1) than in WT C. elegans fed Rhizobium. Because both genes that answered the genetic screen, atm-1 and dog-1, have a role in genome stability and/or DNA damage response and repair (DDR) (15–21), this genetic analysis suggested that C. elegans grown on Rhizobium experiences DNA damage, as revealed by the sur-5::GFP reporter as DNA bridges and fragmented nuclei (Fig. 2).

To test if the abnormal karyokinesis phenotype is a characteristic of a specific step in the DNA damage response pathway, we performed an RNAi screen of C. elegans carrying sur-5::GFP using gene inactivation known to affect specific steps in the DNA damage response and repair pathway (22). We found that inhibition of mus-101 (23) and rad-51 (24) (genes representing double strand break repair pathway), lin-40 (25) (a chromatin factor), wwp-1 (26) (a protein degradation pathway), nola-3 (27) (RNA processing and trafficking), and sex-1 (28) showed abnormal gut karyokinesis similar to that observed in WT C. elegans grown on Rhizobium (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Thus, the aberrant nuclei division in the gut cannot be attributed to a specific DDR gene or a single pathway. It is likely to be a consequence of general DNA damage causing compromised DNA/chromosomal integrity.

Hydrogen Peroxide Causes Intestinal DNA Damage in C. elegans Fed on Rhizobium.

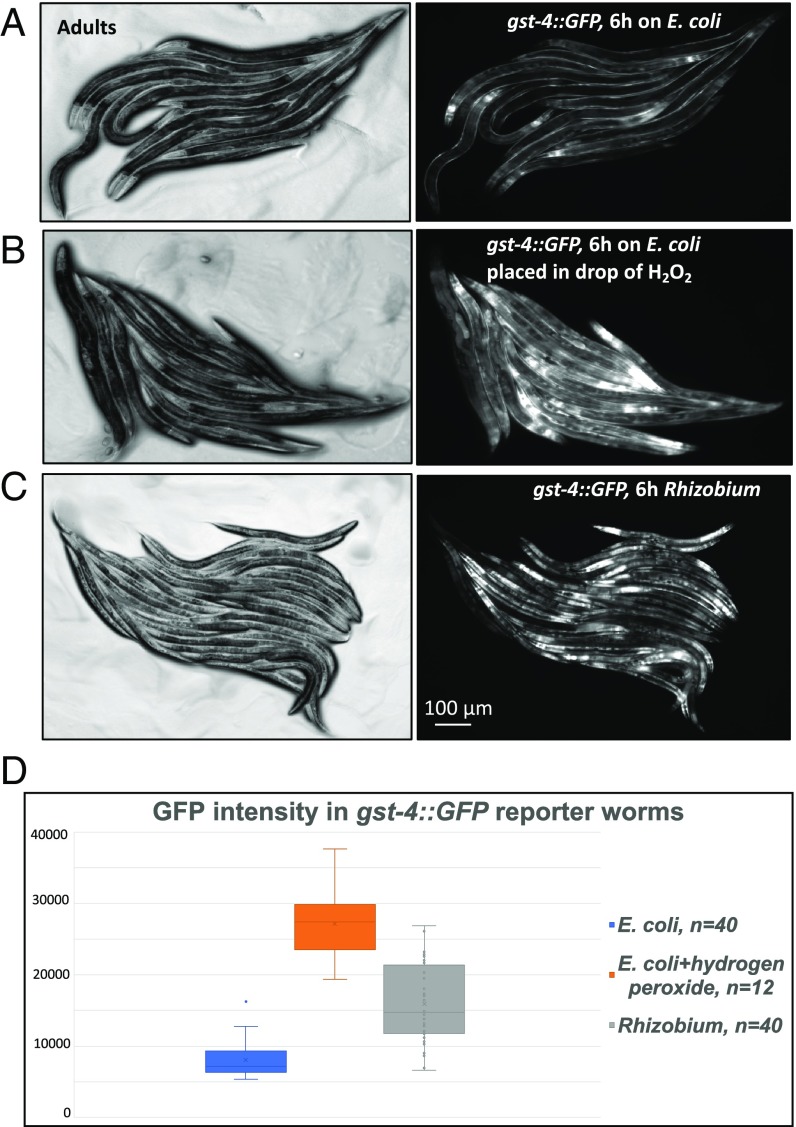

A common cause of DNA damage is reactive oxygen. Using a GST induction reporter gene gst-4p::GFP as an oxidative stress reporter (29), we showed that C. elegans grown on Rhizobium, but not on E. coli, induced the expression of gst-4p::GFP to the level comparable with the expression induced by a potent oxidizer, hydrogen peroxide (30) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Feeding on Rhizobium causes oxidative stress response. (A–C) Fluorescence and differential interference contrast gst-4p::GFP images of C. elegans adults transferred from an E. coli lawn to a new E. coli lawn (A), or transferred to a new E. coli lawn and treated with 30 μL of 3% H2O2 (B), or transferred to a Rhizobium lawn (C). Images were taken 6 h after the transfer of the C. elegans. (D) Graph showing the corresponding GFP intensities in the gut measured with ImageJ software. t test for E. coli vs. E. coli + hydrogen peroxide returns P = 8.95503E−24, and for E. coli vs. Rhizobium, P = 1.29942E−12.

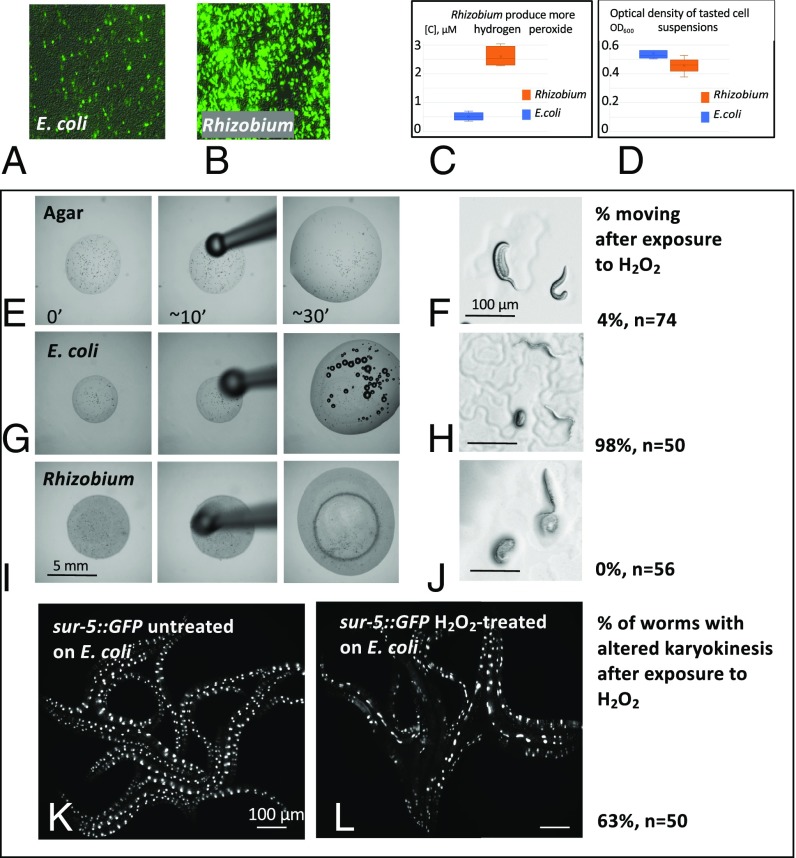

How could Rhizobium cause oxidative stress in C. elegans? Using dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, H2DCFDA-AM, a membrane penetrant redox detector (31, 32), we measured the redox status in living Rhizobium or E. coli cells (Materials and Methods). Rhizobium caused much more intense H2DCFDA-AM fluorescence than E. coli, indicating the presence of more oxidizing metabolites and possibly a higher level of ROS (Fig. 5 A and B). One possible source of bacterial ROS is hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). We measured H2O2 concentrations in E. coli and Rhizobium using a fluorimetric hydrogen peroxide assay. The assay utilizes a substrate for hydrogen peroxidase, an enzyme which, in the presence of hydrogen peroxide, converts it into a fluorescent compound (Materials and Methods). The assay is applicable for the analysis of live cells. The measurement revealed that Rhizobium contains about five times more hydrogen peroxide than E. coli (Fig. 5 C and D).

Fig. 5.

Rhizobium huautlense cells are positive for oxidative stress, produce more hydrogen peroxide, and have less or no catalase activity. Hydrogen peroxide is sufficient to interfere with karyokinesis in the C. elegans gut. (A and B) A fluorescence test for oxidative stress indicates that Rhizobium has more redox activity (more cells have brighter fluorescence) than E. coli grown on NGM agar at room temperature. (C) A graph showing that Rhizobium produces more hydrogen peroxide than E. coli as measured by fluorimetric hydrogen peroxide assay. (D) Graph showing similar absorption (OD600) and therefore concentrations of E. coli and Rhizobium suspensions used in the assay. (E–J) Images of L1 larvae C. elegans treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide on agar (E and F), E. coli lawn (G and H), and Rhizobium lawn (I and J). Catalase activity of E. coli (G and H), but not Rhizobium (I and J) suppresses the paralysis of the L1. Numbers on the right of F, H, and J show percent of moving L1 larvae, and “n” is a number of scored larvae for each condition. (K and L) Fluorescence images of sur-5::GFP reporter C. elegans untreated (K) or treated with hydrogen peroxide (L) during L1 stage. Approximately 63% of treated animals developed the phenotype, n = 50.

Hydrogen peroxide is cytotoxic, but highly conserved catalase enzymes protect cells by metabolizing hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. A simple assay can detect catalase: A drop of 3% H2O2 onto a freshly grown E. coli lawn bubbles due to oxygen production by catalase (Movies S1 and S2). A fresh Rhizobium lawn does not generate bubbles (Movie S3), indicating low or absent catalase activity. C. elegans L1 larvae exposed to 3% hydrogen peroxide on unseeded agar or on a Rhizobium lawn became paralyzed within minutes due to H2O2 toxicity. On E. coli, C. elegans larvae exposed to 3% hydrogen peroxide remained mobile. The catalase activity of E. coli may detoxify the H2O2 whereas the Rhizobium does not produce catalase and could not detoxify the H2O2 (Fig. 5 E–J). Treatment of C. elegans early L1 larvae with 3% hydrogen peroxide on an E. coli lawn induced the same defective intestinal karyokinesis as caused by Rhizobium feeding (Fig. 5 K and L and SI Appendix, Table S1): 63% of C. elegans fed E. coli and treated with 3% H2O2 showed defective karyokinesis.

Based on the facts that feeding on Rhizobium, but not E. coli, causes oxidative stress in C. elegans, that Rhizobium has higher cellular oxidative state and likely higher ROS than E. coli, that Rhizobium accumulate more hydrogen peroxide possibly because of low catalase activity, and that exogenous hydrogen peroxide causes intestinal karyokinesis defects similar to those induced by feeding with Rhizobium, we hypothesized that hydrogen peroxide produced by Rhizobium could be the oxidizing metabolite. Rhizobium could produce hydrogen peroxide in the C. elegans gut, the probable first C. elegans cells to encounter Rhizobium separated by only a cell membrane, as digestion ensues, causing, directly or indirectly, DNA damage in adjacent intestinal cells.

Hypoxia or Antioxidants Suppress the Karyokinesis Defect in C. elegans Grown on Rhizobium.

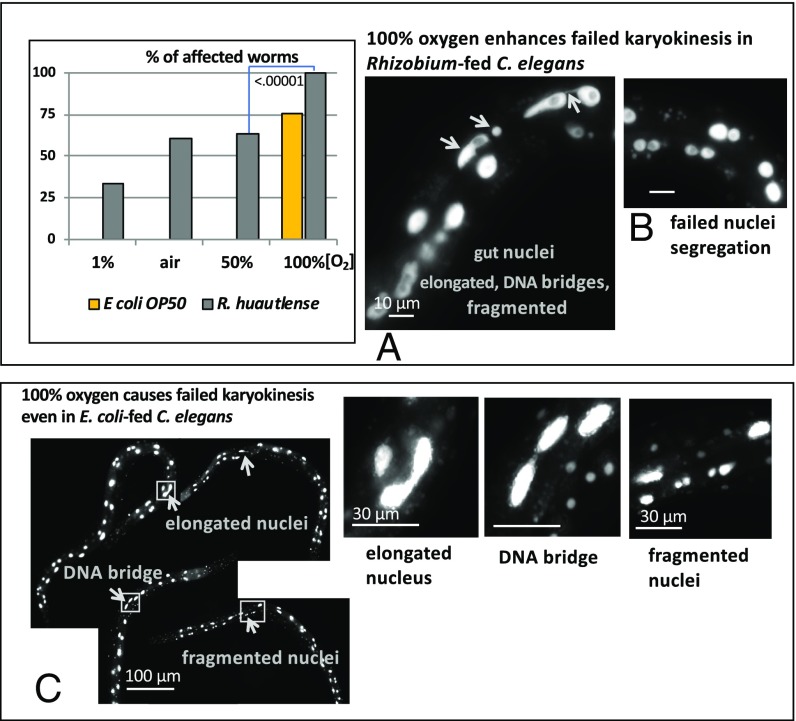

If the oxidative stress model is correct, then karyokinesis defect caused by Rhizobium should depend on oxygen concentration. We found that hypoxia (1% oxygen) significantly reduced the defective gut karyokinesis phenotype in C. elegans grown on Rhizobium whereas high oxygen (100% oxygen) enhanced the phenotype on Rhizobium (graph in Fig. 6, Fig. 6 A and B, and SI Appendix, Table S1). Moreover, 100% O2 caused the defective gut karyokinesis phenotype in C. elegans fed on normally benign E. coli (Fig. 6C and SI Appendix, Table S1). These DNA damage responses to increased oxygen both on E. coli and Rhizobium are likely to be via increased production of ROS.

Fig. 6.

Abnormal intestinal karyokinesis in C. elegans fed with Rhizobium depends on oxygen. (A) The graph shows the percentage of C. elegans with defective gut nuclear division when grown on Rhizobium from hatching in a chamber with indicated concentration of oxygen; n > 50, P value is shown. (A and B) Fluorescence images of gut nuclei in adult C. elegans fed on Rhizobium and maintained at 100% oxygen; (A) arrows point to elongated nuclei, fragmented nuclei, and nuclei connected with DNA bridges. (B) Closely positioned nuclei indicate a failed nuclei segregation. (C) Images of C. elegans fed with E. coli at 100% oxygen from the time of hatching illustrate abnormal gut nuclei pattern (arrowheads and Insets).

We tested if a treatment of L1 larvae with N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), a potent antioxidant that reacts with hydrogen peroxide (33), could alleviate the Rhizobium gut karyokinesis defect. We treated L1 larvae with NAC by letting them hatch overnight in a solution of NAC. The treated and untreated C. elegans were plated on Rhizobium or Rhizobium supplemented with NAC, as well as on control E. coli lawns, and scored for the intestinal karyokinesis defect (Materials and Methods). Treatment of L1 larvae with NAC before exposure to Rhizobium suppressed the karyokinesis defect, but a supplementation of a Rhizobium lawn with NAC could not rescue the Rhizobium-induced karyokinesis defect in untreated larvae (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A and Table S1). The data indicate that NAC promotes a resistance to oxidative stress in larvae rather than reduced ROS levels in Rhizobium. These results support the hypothesis that bacterial-induced oxidative stress and ROS cause abnormal karyokinesis in intestinal nuclei.

In a related experiment, we found that growth of C. elegans on Rhizobium in the presence of an apple slice (Materials and Methods), likely to contain a natural antioxidant, also inhibited the intestinal karyokinesis defect (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B and Table S1). A reduction of ROS by antioxidants in the apple or indirectly through a change in Rhizobium metabolism is possible. The suppression of ROS damage by the apple could explain why proliferating C. elegans are almost always found on fallen fruits in nature, but not in soil harboring similar bacterial strains (34, 35).

Rhizobium Induces C. elegans Intestinal Karyokinesis Defects over a Short Range.

Since there were no obvious changes in karyokinesis outside of the intestine (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), we hypothesized that ingested Rhizobium disrupts intestinal karyokinesis over a short range from the lumen of the gut to the gut nucleus. We tested this hypothesis by obstructing direct contact between Rhizobium and C. elegans with a 0.22-µm-pore-size filter. The filter was placed on the Rhizobium lawn, and the C. elegans eggs were spotted on top of the filter along with a small aliquot of E. coli as a food to stimulate postembryonic development (36). A second filter prepared with a mixture of E. coli with Rhizobium without filter served as a control. We found that a presence of the filter between Rhizobium and the C. elegans inhibited the intestinal karyokinesis defects whereas control C. elegans in contact with Rhizobium showed the gut karyokinesis defect (Materials and Methods and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). These results suggest that the intestinal karyokinesis defect could be caused by Rhizobium cells contacting cells in the nematode. Such a short-range agent of DNA damage is consistent with hydrogen peroxide.

We also measured formation of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), one of the hallmarks of oxidative DNA damage, in chromosomal DNA isolated from C. elegans grown on E. coli and Rhizobium (Materials and Methods). We did not detect a significant difference in the concentration of 8-OHdG between the Rhizobium- or E. coli-grown C. elegans (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). But, if DNA damage is localized to only intestinal cells (less than 1% of the DNA content of a fertile hermaphrodite), we would not expect to see a dramatic change in 8-OHdG as measured for the entire DNA content of a C. elegans. In published experiments, treatment of C. elegans with hydrogen peroxide, a known agent promoting formation of 8-OHdG (37), resulted only in a modest increase in [8-OHdG], from 20 to 25 pg per microgram of chromosomal DNA, despite high dosage of hydrogen peroxide and lengthy treatment (38). Thus, our results should not be interpreted as an absence of a change in 8-OHdG as this assay might not be sensitive enough to reveal the change in chromosomal DNA of intestinal cells.

Does Higher ROS Level Associated with Aberrant Karyokinesis in C. elegans Come Exclusively from Ingested Rhizobium?

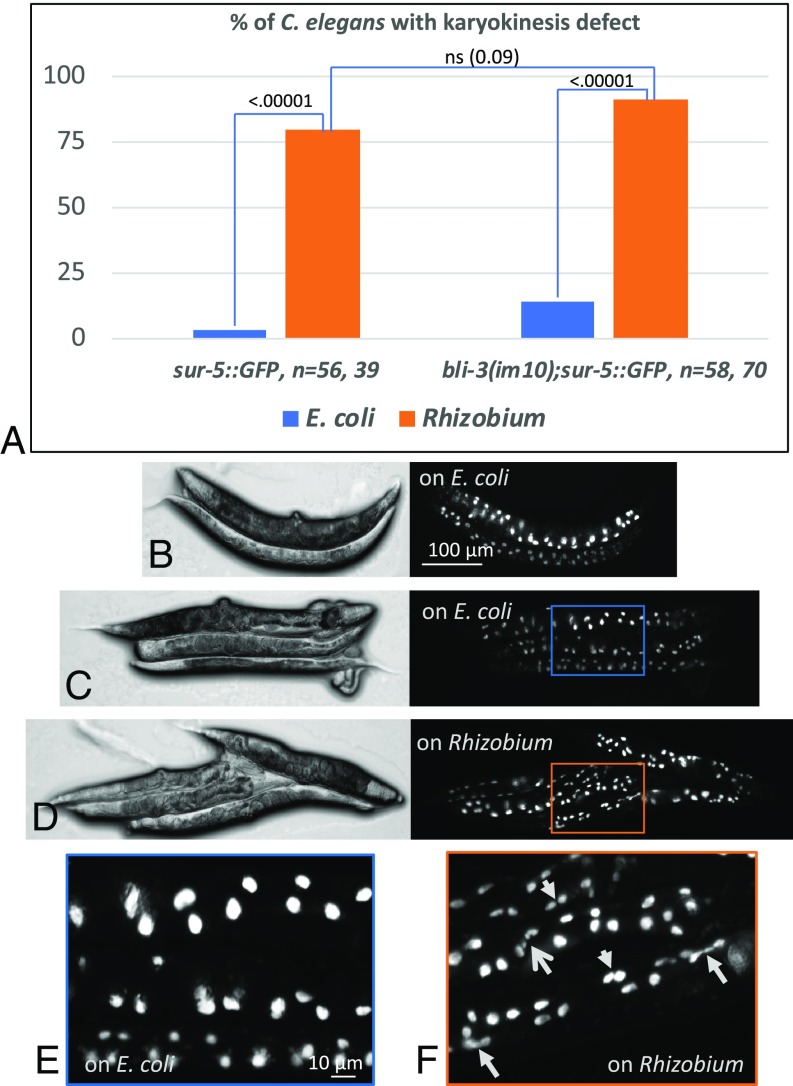

The pathogenic bacteria Enterobacteria faecalis does not produce ROS during infection but induces ROS production by the worm itself through activation of its dual oxidase, BLI-3 (39–41). BLI-3 has a NADPH oxidase (NOX) domain responsible for the ROS production and a peroxidase-like domain utilizing hydrogen peroxide (40, 42–44). We tested if NOX contributes to aberrant karyokinesis in worms fed on Rhizobium. An inhibition of NOX function in bli-3(im10) mutants decreases hydrogen peroxide level during E. faecalis infection (40). We thus crossed bli-3(im10) worms with sur-5::GFP reporter strain and compared the karyokinesis phenotype in the worms grown on E. coli and Rhizobium (Fig. 7). The characteristic Rhizobium-induced elongated, double and fragmented nuclei phenotype could still be seen in these worms. This result indicated that a NOX-mediated increase in hydrogen peroxide level upon infection is not essential for the karyokinesis defect in worms grown on Rhizobium.

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of ROS production by NOX in bli-3(im10) mutants does not rescue aberrant karyokinesis in gut nuclei of C. elegans grown on Rhizobium. (A) Graph showing percentage of worms with karyokinesis defect on E. coli and Rhizobium. P values are shown. ns, not significant. (B–F) differential interference contrast and fluorescence bli-3(im10);sur-5::GFP images of adult worms grown on E. coli (B, C, and E) and Rhizobium (D and F). (E and F) Enlarged Insets shown in C and D, correspondingly. (F) Arrows point to elongated (closed arrows), fragmented (open arrow), and double nuclei (short arrows). bli-3 mutants have “blistered” phenotype and small and deformed body shapes due to its role in collagen crosslinking of the cuticle (43, 44). Because of that, the gut nuclei pattern is somewhat disturbed in comparison with WT worms but the karyokinesis defect can be observed in the intestine.

Other Phenotypes Associated with Feeding on Rhizobium.

C. elegans grown on Rhizobium from the time of hatching were thinner and smaller in body size (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A and B). We tested a hypothesis that altered karyokinesis in some intestinal cells might impair intestinal function, resulting in the body mass deficiency. We supplemented Rhizobium food with E. coli by mixing Rhizobium with E. coli 1:10, 1:1, 10:1, and 100:1 by volume and evaluated both body size and gut nuclei morphology in C. elegans maintained on the mixed bacterial lawns from the time of hatching. We found that supplementation with E. coli at any dilution fully rescued the small, scrawny phenotype, but not the intestinal karyokinesis defect, although reducing its penetrance from 79 to 40% (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 C and D). This result indicates that Rhizobium may generate less of an essential nutrient or micronutrient for rapid C. elegans growth that is produced by E. coli. Because only a small fraction of E. coli could suppress the slow growth phenotype, but not the intestinal karyokinesis defect, the bacterial mixing experiment also suggested that a micronutrient malnutrition rather than a gut function defect prevented normal growth in C. elegans fed on Rhizobium. Considering that the abnormal gut nuclei morphology was observed only in a few nuclei in a 1,000-celled worm, it is not surprising that the physiological consequence of it was insignificant.

A test for bacterial aversion behavior revealed that Rhizobium does not repel C. elegans (SI Appendix, Fig. S9), indicating that the C. elegans pathogen surveillance system was not activated (45). In nature, Rhizobium forms a symbiotic relationship with particular legumes, fixing atmospheric nitrogen for the plant in return for carbon (46, 47). The Rhizobium–C. elegans ROS interaction may be mechanistically related to this more intimate plant bacterial symbiosis.

Concluding Remarks

We have shown that the Rhizobium that C. elegans may encounter in nature in rotting fruits inhibits normal karyokinesis in intestinal cells. We could cause a similar intestinal cell phenotype via genetic lesions in C. elegans DNA damage response genes, atm-1 and dog-1, suggesting that, indeed, DNA damage is a likely reason for abnormal nuclei divisions in the gut of C. elegans fed on Rhizobium. How does feeding on Rhizobium cause DNA damage in C. elegans? A common cause of DNA damage is reactive oxygen species (ROS). We showed that the Rhizobium diet evoked an oxidative stress response in C. elegans. A measurement of intracellular oxidative activity in Rhizobium revealed that it is higher than E. coli. The suppression of the karyokinesis defect on Rhizobium by growth under hypoxia conditions or with free radical scavengers also supports the model of ROS as a cause. What could be the Rhizobium-produced ROS? We favor the model that the ROS is hydrogen peroxide. Treatment with exogenous hydrogen peroxide causes abnormal karyokinesis similar to that caused by Rhizobium, and the concentration of hydrogen peroxide is higher in Rhizobium than in E. coli. In addition, it is feasible that relatively stable (half-life in milliseconds) and polar hydrogen peroxide can transit from bacteria inside the intestinal lumen, across two bacterial and one eukaryotic cell membrane, into the intestinal cell where it is converted into a hydroxyl radical in the presence of ferrous (Fe2+) iron via the Fenton reaction (48) to damage DNA. The short half-life of this ROS would explain why a proximity between gut and Rhizobium cells is required for DNA damage to occur. It would also explain why most nuclei are not affected, which would be expected from a diffusion of more stable toxic product along intestinal tract. Why does the Rhizobium impair intestinal karyokinesis but not noticeably affect the function of the gut as might be expected from DNA damage mutagenesis? One possible explanation is that, in C. elegans, intestinal cells endoreduplicate genomic DNA during postembryonic development to generate the 32C per nucleus (11). The high copy number of these genomes may decrease the probability of a protein deficiency caused by DNA damage.

The altered gut nuclei phenotype is an easy readout; it could be used to further understand consequences of a high oxygen environment on animal cells. An interesting by-product of our EMS screen was a finding that the altered intestinal nuclei phenotype in sur-5::GFP reporter strain could be used as a discovery tool in a search for genes required for genome stability. Some of the candidate mutations selected in the screen are in the genes not previously linked to DNA damage response, repair, or chromosome segregation and, therefore, may reveal new genes involved in these processes (SI Appendix, Fig. S10).

In bacteria, ROS [superoxide (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl ion (HO·)] are naturally generated during aerobic growth when molecular oxygen acquires electrons from reduced cofactors of various flavoproteins (49) and from side reactions of the electron transport chain (50). ROS inhibits enzymes containing iron or iron–sulfur clusters, including multiple enzymes involved in DNA replication and repair. To resist ROS, bacteria have evolved a number of strategies, such as the ROS efflux, compartmentalization, scavenging, and DNA repair mechanisms (49, 51). Some bacteria use ROS in fighting prokaryotic competitors less protected from oxidative stress, by either releasing ROS or inducing ROS production within neighboring cells by secreting redox cycling drugs (51–56). ROS-producing Helicobacter pylori and Enterococcus faecalis in the mammalian intestine may cause double strand breaks in DNA of epithelial cells, thus contributing to gastric carcinogenesis (57, 58). Killing of C. elegans with streptococcal species and Enterococcus faecium via hydrogen peroxide has been reported (59–61). It would be fascinating to explore the potential countermeasures that eukaryotes marshal to respond to bacteria and the counter countermeasures in turn used by bacteria.

Materials and Methods

The C. elegans and Bacteria Strains and Maintenance.

The C. elegans and bacteria strains and maintenance were as follows: N2 Bristol, GR3065: translational sur-5::GFP from laboratory stock; VC381: atm-1(gk186), VC13: dog-1(gk10), CL2166: gst-4p::GFP, GS3798: arIs99 [dpy-7p::2Xnls::YFP], and LW699: GFP-tagged LMN-1 were obtained from CGC; GR3066: atp-1(mg665);sur-5::GFP, GR3067: dog-1(mg666);sur-5::GFP, GR3068: dog-1(mg667);sur-5::GFP, GR3069: dog-1(mg668);sur-5::GFP, GR3195: dog-1(mg694);sur-5::GFP, and GR3196: dog-1(mg695);sur-5::GFP were generated by EMS in the course of this study. bli-3(im10) was a gift from Hiroki Moribe, Kurume University School of Medicine, Fukuoka, Japan. These mutants were crossed with sur-5::GFP reporter strain. All strains were maintained at 15 °C on nematode growth media (NGM) (62) agar plates in the presence of streptomycin (250 μg/mL final concentration) and seeded with OP50-1 E. coli carrying an integrated streptomycin resistance gene (CGC). Throughout the text, it is referred to as E. coli. RNAi was performed as described (63).

The library of the wild bacterial isolates (JUb) was created by, and obtained from, the M.-A. Félix laboratory (3, 8, 64). Rhizobium huautlense (ATCCBAA-115) and Rhizobium galegae (ATCC43677) were obtained from ATCC. Agrobacterium was a gift from the Jen Sheen laboratory (Department of Molecular Biology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston).

Screening the JUb Library.

Bacteria were grown in liquid LB for 3 to 4 d at room temperature until suspensions appeared cloudy. Then, 300 µL of the liquid cultures were spotted on 3-cm NGM agar plates without antibiotic. The plates with the bacteria were maintained at room temperature for 2 d before setting up experiments. C. elegans sur-5::GFP eggs were obtained by bleaching gravid adults (62) and were spotted on the top of the bacterial lawn. The plates with C. elegans were maintained at 15 °C. The phenotypes were scored at various time points. Identity of all bacterial strains mentioned in this work was confirmed by 16S sequencing (MacrogenUSA).

Microscopy and DAPI Staining.

For staining with DAPI, 30 C. elegans were transferred to a 1.5-mL Eppendorf tube filled with 20 µL of cold methanol and kept at −20 °C for 5 min. Methanol was aspirated, and 20 µL of S-basal (62) was added and pipetted up and down to separate bacteria stuck to C. elegans. The bacteria suspended in S-basal were removed. Finally, 10 µL of S-basal with 0.5 µL of DAPI solution (200×) was added to the worm pellet. After 5 min of incubation with DAPI, the worm’s corpses were mounted on a microscopic agarose pad.

Live and fixed C. elegans were visualized with AxioZoom.V16 (Zeiss) and AxioImagerZ.1 (Zeiss) microscopes equipped with OrkaFlash 4.0 (Hamamatsu) and Axiocam HRc (Zeiss) cameras, respectively. Images were processed with ImageJ software.

Feeding C. elegans with Rhizobium.

The Rhizobium cultures and plates were prepared as described above for the JUb library clones. Control E. coli strain was grown the same way and plated on NGM without antibiotics. Typically, two to three adults or 100 eggs or L1 larvae hatched in S-basal buffer overnight were plated on the lawns.

Testing a Requirement for a Contact Between the Rhizobium and C. elegans for Inducing Intestinal Nuclei Phenotype.

A small, 10-mm-diameter, Rhizobium lawn was covered with a polyethersulfone (PES) 0.2-μm, 25-mm membrane filter (Sterlitech Corp.). Then, 100 µL of overnight suspension of E. coli, was placed on the top of the filter and was allowed to form a lawn. This was needed to stimulate the worm’s development, which requires consumption of the live bacterial food (36). As a control, 100 µL of LB without E. coli was added to the Rhizobium lawn and to the Rhizobium covered with the filter. Analogously, 100 µL of E. coli was added to the Rhizobium lawn without the filter. Bleached sur-5::GFP eggs were plated on the top. The gut phenotype was scored in the grown adults (n = 50).

EMS Mutagenesis and Selection of Mutants.

Mutagenesis of sur-5::GFP was done according to the published protocol (6). The aliquots of treated C. elegans were distributed on dozens of 10-cm NGM agar plates seeded with 10× concentrated E. coli bacterial lawn. Second generation (F1) progeny were bleached and plated in aliquots on 10 10-cm NGM agar plates seeded with 10× concentrated E. coli bacterial lawn. Adults (F2) with the desired phenotype were cloned, and homozygote progeny were outcrossed with a parental strain more than two times. Fewer than 10,000 haploid genomes were screened; the screen was not performed to saturation.

Identification of EMS mutants.

Next-generation sequencing of EMS mutants.

DNA isolation, library construction, and whole genome sequencing with Illumina were carried out according to the published protocol (65).

Complementation test.

Available alleles of the candidate genes were obtained from CGC and crossed with corresponding EMS mutants. An appearance of the altered gut nuclei phenotype indicated failed complementation and suggested that corresponding genes are the causative genes.

Evaluation of the gut nuclei phenotype with sur-5::GFP reporter.

The candidate mutants obtained from CGC were outcrossed two times and crossed with sur-5::GFP, and their gut nuclei phenotype was evaluated on E. coli bacterial lawn.

RNAi Screen.

C. elegans sur-5::GFP adults were bleached, and eggs were plated on bacterial lawn expressing RNAi (63) targeting a subset of DDR genes. Adult C. elegans were evaluated for abnormal gut nuclei.

Oxidative Stress Detection in E. coli and Rhizobium with H2DCFDA-AM Reagent.

The reagent dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate allowed the oxidative stress detection inside living cells. The procedure was according to the provided protocol: 10 µL of H2DCFDA-AM reagent (Molecular Probes) [10× stock solution in DMSO] spotted on the top of bacterial lawns. After 1 h at room temperature, cells were transferred on microscopic agarose and evaluated under the UV scope.

Hydrogen Peroxide Detection in E. coli and Rhizobium.

Bacteria were grown in LB liquid media at room temperature to saturation (OD600 ∼ 0.5). The suspensions were spun down and resuspended in the same volume of S-basal media. Then, 50 μL of the suspension in triplicates were tested for hydrogen peroxide concentration with a Fluorimetric Hydrogen Peroxide Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Sigma-Aldrich). Fluorescence Ex λ540/Em λ590 was measured with microplate reader SpectraMax M5e (Molecular Dynamics).

Hydrogen Peroxide Treatment.

Early L1 larvae hatched in S-basal overnight were spotted on the small (∼1 cm in diameter) E. coli lawn on regular NGM plates. Then, 50 µL of 3% hydrogen peroxide was added so that all of the lawn area was covered. An appearance of bubbles (oxygen) indicated the presence of hydrogen peroxide and catalase activity: 2H2O2 →catalase→ 2H2O+O2. The plates were kept at room temperature. The adult C. elegans grown from the treated L1 were inspected on day 3.

Catalase Tests.

To test catalase activity, 10 μL of 3% hydrogen peroxide was dropped on E. coli and Rhizobium lawns; a generation of bubbles was observed and recorded. To test the efficiency of bacterial catalase on reducing hydrogen peroxide concentration, 5 μL of synchronized L1 larvae in S-basal were plated on agar, E. coli and Rhizobium lawns and immediately covered with hydrogen peroxide at a toxic dose of 30 μL of 3%. The process and generation of bubbles on E. coli, but not on agar or Rhizobium, was recorded. Two hours later, the C. elegans were visually examined for their ability to move.

Oxygen Treatment.

Rhizobium and E. coli lawns on NGM plates without antibiotics prepared as described above were seeded with C. elegans eggs and placed in oxygen chambers (Hypoxia Incubator Chamber; Stemcell technologies) with 1% (hypoxia) and high oxygen (50% and 100%) at 20 °C and kept under the conditions for 2 d. The phenotype was scored in adults.

Evaluation of DNA Damage with 8-OHdG ELISA.

Chromosomal DNA was extracted from adult C. elegans grown on E. coli and Rhizobium according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Puregene Tissue kit; Qiagen). Isolated DNA was treated with nuclease P1 and shrimp alkaline phosphatase (Sigma-Aldrich) to prepare for the assay as instructed in the protocol (OxiSelect Oxidative DNA Damage ELISA Kit; Cell Biolabs). Three biological replicates (DNA isolated from different batches of C. elegans on different days) and two technical replicates (split DNA solution from the same isolate) were obtained from C. elegans grown on E. coli and two biological and two technical replicates from the C. elegans grown on Rhizobium. The samples and standards were treated according to the protocol (OxiSelect Oxidative DNA Damage ELISA Kit; Cell Biolabs). Microplate reader SpectraMax M5e (Molecular Dynamics) was used for measurement absorption at 450 nm. Concentration of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) in the samples was determined according to the standard curve in Excel.

Treating C. elegans with N-acetyl-cysteine.

Stock solution of NAC (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared by dissolving 80 mg of NAC crystals in 10 mL of sterile water (∼50 mM). Then, 1 mL of NAC solution or sterile water (as a control) was added on the top of 3-d-old E. coli or Rhizobium lawn on NGM agar without antibiotics, making roughly 5 mM final concentration of NAC. Eggs obtained by bleaching were spotted immediately after addition of NAC or water to the plates. Also, NAC (1/10 by volume) was added to the rest of the egg prep and incubated overnight at room temperature. L1 larvae hatched in NAC solution were plated on the E. coli and Rhizobium plates treated with NAC as above. Adult C. elegans were scored for the abnormal gut nuclei phenotype.

Feeding C. elegans with an Apple Supplement.

Rhizobium plates were prepared as described above. Red apple cultivars, MacIntosh and Macoun, obtained from a local grocery store, were tested. The apples were wiped out with ethanol-soaked paper and rinsed with sterile water three times. Apple slices were cut out with a sterile blade and placed on the top of bacterial lawn. C. elegans eggs were plated on the top and near the slices (one slice per plate). No contaminating bacteria or fungi were visually detected on the apple plates within 5 to 6 d of the experiment.

Statistics.

Whenever applicable, the experiments were done at least in three biological triplicates with 50 to 100 C. elegans at each condition when not indicated otherwise. P values were calculated with t test using Excel (Microsoft office) or calculating z score for the difference between two datasets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the G.R. laboratory for helpful discussions; the Marie-Anne Félix group for sharing a collection of wild bacterial isolates; the Jen Sheen laboratory for the gift of Agrobacteria; and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) for providing worm strains. The work was supported by NIH Grants GM044619 and AG043184 (to G.R.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1815656116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Shtonda BB, Avery L. Dietary choice behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:89–102. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacNeil LT, Watson E, Arda HE, Zhu LJ, Walhout AJM. Diet-induced developmental acceleration independent of TOR and insulin in C. elegans. Cell. 2013;153:240–252. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frézal L, Félix M-A. C. elegans outside the Petri dish. eLife. 2015;4:381. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulenburg H, Félix M-A. The natural biotic environment of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2017;206:55–86. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.195511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dirksen P, et al. The native microbiome of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: Gateway to a new host-microbiome model. BMC Biol. 2016;14:38. doi: 10.1186/s12915-016-0258-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Félix M-A, Braendle C. The natural history of Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R965–R969. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samuel BS, Rowedder H, Braendle C, Félix M-A, Ruvkun G. Caenorhabditis elegans responses to bacteria from its natural habitats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E3941–E3949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607183113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Félix M-A, et al. Species richness, distribution and genetic diversity of Caenorhabditis nematodes in a remote tropical rainforest. BMC Evol Biol. 2013;13:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-13-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu T, Orita S, Han M. Caenorhabditis elegans SUR-5, a novel but conserved protein, negatively regulates LET-60 Ras activity during vulval induction. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4556–4564. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedgecock EM, White JG. Polyploid tissues in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1985;107:128–133. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1977;56:110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dass Singh M, et al. Infant birth outcomes are associated with DNA damage biomarkers as measured by the cytokinesis block micronucleus cytome assay: The DADHI study. Mutagenesis. 2017;32:355–370. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gex001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakhoum SF, Kabeche L, Compton DA, Powell SN, Bastians H. Mitotic DNA damage response: At the crossroads of structural and numerical cancer chromosome instabilities. Trends Cancer. 2017;3:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones MR, Huang JC, Chua SY, Baillie DL, Rose AM. The atm-1 gene is required for genome stability in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Genet Genomics. 2012;287:325–335. doi: 10.1007/s00438-012-0681-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Youds JL, et al. DOG-1 is the Caenorhabditis elegans BRIP1/FANCJ homologue and functions in interstrand cross-link repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1470–1479. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01641-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saito TT, Lui DY, Kim H-M, Meyer K, Colaiácovo MP. Interplay between structure-specific endonucleases for crossover control during Caenorhabditis elegans meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, et al. Isolation of C. elegans and related nematodes. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3937–3947. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.11.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopson S, Thompson MJ. BAF180: Its roles in DNA repair and consequences in cancer. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:2482–2490. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J, et al. Essential roles for Caenorhabditis elegans lamin gene in nuclear organization, cell cycle progression, and spatial organization of nuclear pore complexes. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3937–3947. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.11.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimada K, et al. TORC2 signaling pathway guarantees genome stability in the face of DNA strand breaks. Mol Cell. 2013;51:829–839. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Haaften G, et al. Identification of conserved pathways of DNA-damage response and radiation protection by genome-wide RNAi. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1344–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holway AH, Hung C, Michael WM. Systematic, RNA-interference-mediated identification of mus-101 modifier genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2005;169:1451–1460. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.036137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takanami T, Mori A, Takahashi H, Horiuchi S, Higashitani A. Caenorhabditis elegans Ce-rdh-1/rad-51 functions after double-strand break formation of meiotic recombination. Chromosome Res. 2003;11:125–135. doi: 10.1023/a:1022863814686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solari F, Bateman A, Ahringer J. The Caenorhabditis elegans genes egl-27 and egr-1 are similar to MTA1, a member of a chromatin regulatory complex, and are redundantly required for embryonic patterning. Development. 1999;126:2483–2494. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrano AC, Liu Z, Dillin A, Hunter T. A conserved ubiquitination pathway determines longevity in response to diet restriction. Nature. 2009;460:396–399. doi: 10.1038/nature08130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camon E, et al. The gene ontology annotation (GOA) project: Implementation of GO in SWISS-PROT, TrEMBL, and InterPro. Genome Res. 2003;13:662–672. doi: 10.1101/gr.461403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carmi I, Kopczynski JB, Meyer BJ. The nuclear hormone receptor SEX-1 is an X-chromosome signal that determines nematode sex. Nature. 1998;396:168–173. doi: 10.1038/24164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tawe WN, Eschbach ML, Walter RD, Henkle-Dührsen K. Identification of stress-responsive genes in Caenorhabditis elegans using RT-PCR differential display. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1621–1627. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.7.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imlay JA, Chin SM, Linn S. Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science. 1988;240:640–642. doi: 10.1126/science.2834821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LeBel CP, Ischiropoulos H, Bondy SC. Evaluation of the probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin as an indicator of reactive oxygen species formation and oxidative stress. Chem Res Toxicol. 1992;5:227–231. doi: 10.1021/tx00026a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalyanaraman B, et al. Measuring reactive oxygen and nitrogen species with fluorescent probes: Challenges and limitations. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aruoma OI, Halliwell B, Hoey BM, Butler J. The antioxidant action of N-acetylcysteine: Its reaction with hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, superoxide, and hypochlorous acid. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;6:593–597. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berg M, et al. Assembly of the Caenorhabditis elegans gut microbiota from diverse soil microbial environments. ISME J. 2016;10:1998–2009. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrière A, Félix MA. Isolation of C. elegans and related nematodes. WormBook. 2006:1–9. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.115.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qi B, Kniazeva M, Han M. A vitamin-B2-sensing mechanism that regulates gut protease activity to impact animal’s food behavior and growth. eLife. 2017;6:781. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takeuchi T, Nakajima M, Morimoto K. Relationship between the intracellular reactive oxygen species and the induction of oxidative DNA damage in human neutrophil-like cells. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:1543–1548. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.8.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aan GJ, Zainudin MSA, Karim NA, Ngah WZW. Effect of the tocotrienol-rich fraction on the lifespan and oxidative biomarkers in Caenorhabditis elegans under oxidative stress. Clinics (São Paulo) 2013;68:599–604. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(05)04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chávez V, Mohri-Shiomi A, Garsin DA. Ce-Duox1/BLI-3 generates reactive oxygen species as a protective innate immune mechanism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4983–4989. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00627-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Hoeven R, Cruz MR, Chávez V, Garsin DA. Localization of the dual oxidase BLI-3 and characterization of its NADPH oxidase domain during infection of Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoeven Rv, McCallum KC, Cruz MR, Garsin DA. Ce-Duox1/BLI-3 generated reactive oxygen species trigger protective SKN-1 activity via p38 MAPK signaling during infection in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002453. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chávez V, Mohri-Shiomi A, Maadani A, Vega LA, Garsin DA. Oxidative stress enzymes are required for DAF-16-mediated immunity due to generation of reactive oxygen species by Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2007;176:1567–1577. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.072587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edens WA, et al. Tyrosine cross-linking of extracellular matrix is catalyzed by Duox, a multidomain oxidase/peroxidase with homology to the phagocyte oxidase subunit gp91phox. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:879–891. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moribe H, et al. Tetraspanin is required for generation of reactive oxygen species by the dual oxidase system in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Melo JA, Ruvkun G. Inactivation of conserved C. elegans genes engages pathogen- and xenobiotic-associated defenses. Cell. 2012;149:452–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruvkun GB, Sundaresan V, Ausubel FM. Directed transposon Tn5 mutagenesis and complementation analysis of Rhizobium meliloti symbiotic nitrogen fixation genes. Cell. 1982;29:551–559. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arthikala M-K, et al. RbohB, a Phaseolus vulgaris NADPH oxidase gene, enhances symbiosome number, bacteroid size, and nitrogen fixation in nodules and impairs mycorrhizal colonization. New Phytol. 2014;202:886–900. doi: 10.1111/nph.12714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walling C. Fenton’s reagent revisited. Acc Chem Res. 2002;8:125–131. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imlay JA. The molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences of oxidative stress: Lessons from a model bacterium. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:443–454. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boveris A. 1977. Mitochondrial production of superoxide radical and hydrogen peroxide. Tissue Hypoxia and Ischemia, Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (Springer US, Boston), pp 67–82.

- 51.Seaver LC, Imlay JA. Are respiratory enzymes the primary sources of intracellular hydrogen peroxide? J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48742–48750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell. 2007;130:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bienert GP, Schjoerring JK, Jahn TP. Membrane transport of hydrogen peroxide. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:994–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hawes SE, et al. Hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli and acquisition of vaginal infections. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1058–1063. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pericone CD, Overweg K, Hermans PW, Weiser JN. Inhibitory and bactericidal effects of hydrogen peroxide production by Streptococcus pneumoniae on other inhabitants of the upper respiratory tract. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3990–3997. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.3990-3997.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.St Amant DC, Valentin-Bon IE, Jerse AE. Inhibition of Neisseria gonorrhoeae by Lactobacillus species that are commonly isolated from the female genital tract. Infect Immun. 2002;70:7169–7171. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.7169-7171.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huycke MM, Abrams V, Moore DR. Enterococcus faecalis produces extracellular superoxide and hydrogen peroxide that damages colonic epithelial cell DNA. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:529–536. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Handa O, Naito Y, Yoshikawa T. Redox biology and gastric carcinogenesis: The role of Helicobacter pylori. Redox Rep. 2011;16:1–7. doi: 10.1179/174329211X12968219310756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jansen WTM, Bolm M, Balling R, Chhatwal GS, Schnabel R. Hydrogen peroxide-mediated killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5202–5207. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.5202-5207.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bolm M, Jansen WTM, Schnabel R, Chhatwal GS. Hydrogen peroxide-mediated killing of Caenorhabditis elegans: A common feature of different streptococcal species. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1192–1194. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.2.1192-1194.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moy TI, Mylonakis E, Calderwood SB, Ausubel FM. Cytotoxicity of hydrogen peroxide produced by Enterococcus faecium. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4512–4520. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4512-4520.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stiernagle T. Maintenance of C. elegans. WormBook. 2006:1–11. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.101.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kamath RS, Ahringer J. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods. 2003;30:313–321. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Félix M-A, Duveau F. Population dynamics and habitat sharing of natural populations of Caenorhabditis elegans and C. briggsae. BMC Biol. 2012;10:59. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lehrbach NJ, Ji F, Sadreyev R. Next-generation sequencing for identification of EMS-induced mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2017;117:7.29.1–7.29.12. doi: 10.1002/cpmb.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.