Abstract

Past research indicates that firefighters are at increased risk for suicide. Firefighter-specific occupational stress may contribute to elevated suicidality. Among a large sample of firefighters, this study examined if occupational stress is associated with multiple indicators of suicide risk, and whether distress tolerance, the perceived and/or actual ability to endure negative emotional or physical states, attenuates these associations. A total of 831 firefighters participated (mean [SD] age = 38.37y[8.53y]; 94.5% male; 75.2% White). The Sources of Occupational Stress-14 (SOOS-14), Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS), and Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire—Revised (SBQ-R) were utilized to examine firefighter-specific occupational stress, distress tolerance, and suicidality, respectively. Consistent with predictions, occupational stress interacted with distress tolerance, such that the effects of occupational stress on suicide risk, broadly, as well as lifetime suicide threats and current suicidal intent, specifically, were attenuated at high levels of distress tolerance. Distress tolerance may buffer the effects of occupational stress on suicidality among firefighters. Pending replication, findings suggest that distress tolerance may be a viable target for suicide prevention initiatives within the fire service.

Keywords: Firefighters, Distress tolerance, Occupational stress, Suicidality

1. Introduction

Over the past several years, research has identified firefighters to be an occupational group at increased risk for suicide (see Stanley et al., 2016, for review). One study of 1,027 male and female career and volunteer firefighters throughout the United States (U.S.) found rates of suicide ideation and attempts occurring throughout one’s career as a firefighter (i.e., career rates) to be 46.8% and 15.5%, respectively (Stanley et al., 2015). Similarly, a separate investigation of female firefighters found elevated rates of suicidality, with 37.7% reporting career suicide ideation and 3.5% reporting a career suicide attempt (Stanley et al., 2017a). Moreover, converging data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest that firefighters are at increased risk for suicide (McIntosh et al., 2016). The CDC found that workers in protective service roles, including firefighters, demonstrate elevated rates of death by suicide compared to other occupational groups (McIntosh et al., 2016; see also Tiesman et al., 2015). Thus, together with research demonstrating elevated rates of mental health disorders associated with increased suicide risk among firefighters (Carleton et al., 2017), research into factors that exacerbate and mitigate suicide risk among this population is deserving of increased empirical inquiry. (Fig. 1)

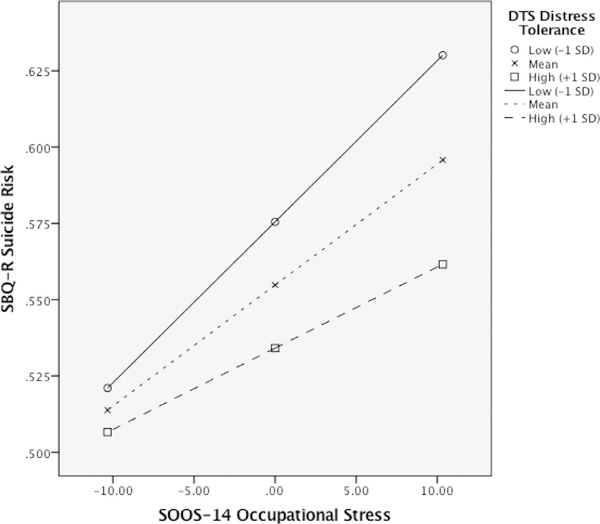

Fig. 1.

The Effects of Occupational Stress on Suicide Risk as a Function of Distress Tolerance

Note. Interaction presented at low (−1SD), mean, and high (+1SD) levels of DTS distress tolerance. The form of the interaction indicates that the effects of SOOS-14 occupational stress on suicide risk is attenuated at high levels of distress tolerance (and potentiated at low levels of distress tolerance). DTS = Distress Tolerance Scale; SBQ-R =Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire—Revised; SOOS-14 =Sources of Occupational Stress Scale—14. Predictor variables centered around their means. SBQ-R transformed variable utilized. Uncontrolled model presented to enhance interpretability.

Indeed, the occupational responsibilities of firefighters include routine exposure to events that may pose a substantial risk for serious injury or death, such as running into burning buildings, extracting car accident victims from the side of a busy highway, and recovering dead bodies, some of which are themselves suicide fatalities (see Kimbrel et al., 2016). These traumatic exposures could, in part, contribute to a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Incidentally, to date, four separate investigations have implicated PTSD symptoms in the pathogenesis of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among firefighters (Boffa et al., 2018b, 2017; Martin et al., 2016; Stanley et al., 2017b). However, beyond onthe-job traumatic exposures, there are many other occupational stressors experienced by firefighters (Henderson et al., 2016). These stressors include sleep disturbances, due in part to long and erratic shift schedules (U.S. Department of Labor, 2015), marital and family stress (Sanford et al., 2017), and harassment (Griffith et al., 2016). The mosaic of occupational stressors experienced by firefighters may, in part, contribute to elevated rates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors observed across multiple studies (Stanley et al., 2017a, 2015). Nevertheless, research examining the effects of occupational stress on suicidal and suicide-related symptoms among firefighters is scarce, with a few exceptions.

For one, a study of 334 U.S. firefighters examined the effects of occupational stress on suicidal ideation (Carpenter et al., 2015). Although the researchers did not find a main effect of occupational stress on suicidal ideation, they did find an interaction with social support such that the concomitant presence of high occupational stress and low social support conferred increased risk for reporting suicidal ideation. This study is noted for several strengths, including its large sample size and use of a measure of occupational stress developed specifically for firefighter populations (i.e., the Sources of Occupational Stress Scale—14 [SOOS-14]; Kimbrel et al., 2011). One limitation is that only suicidal ideation was examined as the criterion variable, which does not capture the severity of suicide risk more broadly (e.g., past suicide attempts, recent suicidal ideation, self-reported future likelihood of making a suicide attempt; Chu et al., 2015; Osman et al., 2001). Yet, this study confirms the importance of examining the effects of occupational stress on suicidal symptoms among firefighters.

Given that occupational stress is, in many ways, endemic to the fire service, it is important to identify associated constructs that are amenable to interventions and may temper the impact of occupational stress on suicidality. One such cognitive-affective factor is distress tolerance—the perceived and/or actual ability to endure negative emotional or physical states (Leyro et al., 2010; Zvolensky et al., 2011). Low levels of distress tolerance have been found to be associated with elevated levels of PTSD symptoms (Marshall-Berenz et al., 2010; Vujanovic et al., 2011) as well as increased suicidal desire (Anestis et al., 2011; Vujanovic et al., 2017a). Thus, distress tolerance is an important construct to consider in the context of both occupational stress and suicidality. Importantly, distress tolerance is amenable to cognitive-behavioral interventions (Bornovalova et al., 2012; Linehan, 2015). Thus, if occupational stress is related to suicide risk at low, but not high, levels of distress tolerance, the administration of interventions designed to augment distress tolerance may reduce suicide risk among firefighters.

Indeed, among a sample of 268 paid U.S. firefighters who work 24-h shifts, Sawhney et al. (2017) found that occupational stress predicted mental health symptoms (e.g., depression, anger, anxiety) one-month later. Moreover, the researchers found that engagement in “work recovery strategies” such as exercise, spending time with coworkers, and recreational activities (cf. distress tolerance activities) mitigates the effects of occupational stress on mental health symptoms. The study by Sawhney and colleagues is noted for several strengths, including a longitudinal design utilizing a large sample of firefighters. However, the study did not evaluate the effects of occupational stress on suicidal symptoms (Stanley et al., 2016). To our knowledge, no study to date has examined the moderating role of distress tolerance on the association between occupational stress and suicide risk among firefighters.

1.1. The current study

Utilizing a large sample of career firefighters, the purpose of this study was to examine the association of occupational stress and suicide risk. Suicide risk was operationalized separately as a total score on the Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire—Revised (SBQ-R; Osman et al., 2001) as well as each of the four SBQ-R items (i.e., lifetime suicidal ideation/attempts, past-year suicidal ideation, lifetime suicide threats, and current suicidal intent). Consistent with past research (Boffa et al., 2018a; Osman et al., 2001; Stanley et al., 2017c), we examined individual SBQ-R items as the criterion variable because the SBQ-R total score, though clinically informative and empirically justified (Batterham et al., 2015), conflates multiple aspects of suicidality. Differentiating between the different facets of suicidality is important because factors associated with suicidal ideation may be different than factors associated with suicidal behaviors (Klonsky and May, 2014; Nock et al., 2016). Further, we examined whether distress tolerance attenuates the association between occupational stress and suicide risk outcomes (i.e., an occupational stress by distress tolerance interaction). We predicted that occupational stress would be associated with increased levels of suicide risk (SBQ-R total score and each SBQ-R item) and that this association would be attenuated with higher self-reported distress tolerance.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Data from 831 firefighters were available for the current study, which was part of a larger ongoing study examining stress and health-related behaviors among career firefighters in a large southern U.S. metropolitan area. In this department, all firefighters also perform emergency medical service (EMS) duties. To be included in the study, participants must have been current firefighters aged 18 years or older. See Table 1 for a summary of participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant Sociodemographic Characteristics (N = 831).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SD) [Range: 20y–63y] | 38.37y (8.53y) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 785 (94.5%) |

| Female | 40 (4.8%) |

| Transgender | 6 (0.7%) |

| Race, No. (Valid %) | |

| White/Caucasian | 625 (75.2%) |

| Black/African American | 106 (12.8%) |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 13 (1.6%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 12 (1.4%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.1%) |

| Other | 74 (8.9%) |

| Ethnicity, No. (Valid %) | |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 216 (26.0%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino/a | 615 (74.0%) |

| Education, No. (Valid %) | |

| Did Not Complete High School | 11 (1.3%) |

| High School Graduate/GED | 67 (8.1%) |

| Some College | 387 (46.6%) |

| College Graduate | 366 (44.0%) |

| Total Years as a Firefighter, Mean (SD) [Range: 0y–42y] | 13.02y (8.71y) |

| Military Status, No. (Valid %) | |

| Active Duty in the Past (Not Now) | 188 (22.6%) |

| Active Duty (Now) | 4 (0.5%) |

| Participated in Initial/Basic Training Only | 20 (2.4%) |

| No Military Experience | 691 (74.5%) |

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic questionnaire

Participants reported information pertaining to sociodemographic and fire service characteristics.

2.2.2. Sources of occupational stress-14 (SOOS-14; Kimbrel et al., 2011)

Occupational stress severity was measured with the 14-item revised version of the Sources of Occupational Stress Scale (Beaton and Murphy, 1993). The SOOS-14 measures on-the-job stress (e.g., “Discrimination based on gender, ethnicity, or age,” “Financial strain due to inadequate pay,” “Disruption of sleep,” and “Concerns about serious personal injury/disablement/death due to work”). Items are scored on a

2.2.3. Distress tolerance scale (DTS; Simons & Gaher, 2005)

The DTS is a 15-item self-report measure that evaluates the extent to which respondents believe that they can experience and withstand distressing emotional states (e.g., “I can’t handle feeling distressed or upset” and “Being distressed or upset is always a major ordeal for me”). Respondents rate their responses to each item on a 5-point Likert-style scale (1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree). Subscales are derived for the first-order factors (i.e., tolerance, absorption, appraisal, and regulation) by averaging across relevant items. In turn, the higher-order score is derived by averaging subscale scores (Simons & Gaher, 2005). For the current study, the DTS Total Score was used as a predictor variable to index perceived psychological distress tolerance, consistent with past research (Vujanovic et al., 2013). The DTS has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Simons & Gaher, 2005). In the current study, the DTS was analyzed as a continuous variable and internal consistency was excellent (α = 0.93).

2.2.4. Suicidal behaviors questionnaire-revised (SBQ-R; Osman et al., 2001)

The SBQ-R is a 4-item self-report measure used to assess suicidality. Each of the four items on the SBQ-R assesses a different aspect of suicidality: Item 1 assesses lifetime suicide ideation and/or suicide attempts (i.e., “Have you ever thought about or attempted to kill yourself?”; 1 = never to 4 = I have attempted to kill myself, and really hoped to die); Item 2 assesses the frequency of suicidal ideation over the past twelve months (i.e., “Have often have you thought about killing yourself in the past year?”; 1 = never to 5 = very often [5 or more times]); Item 3 assesses the threat of suicide attempt (i.e., “Have you ever told someone that you were going to commit suicide, or that you might do it?; 1 = no to 3 = Yes, more than once, but did not want to do it / Yes, more than once, and really wanted to do it); and Item 4 evaluates the self-reported likelihood of suicidal behavior in the future (i.e., “How likely is it that you will attempt suicide someday?”; 0 = never to 6 = very likely). Total scores range from 3–18, with higher scores indicating greater levels of suicidal ideation and/or behavior. Suggested cutoff scores to identify at-risk individuals and specific risk behaviors for the adult general population are ≥ 7 (Osman et al., 2001). The total SBQ-R demonstrates good psychometric properties (Osman et al., 2001) and has been identified as a gold standard assessment of suicidality (Batterham et al., 2015). In the current study, the SBQ-R was analyzed as a continuous variable and internal consistency was acceptable (α = 0.77).

2.2.5. Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977)

The CES-D is a 20-item measure of depressive symptom severity. Participants self-report the frequency of depression symptoms in the past week on a 4-point scale (0 = never or rarely/less than 1 day per week to 3 = almost all the time/5–7 days per week); higher total scores indicate greater severity of depression symptoms. This instrument has been validated in a sample of firefighters (Chiu et al., 2010). In the current study, the CES-D was analyzed as a continuous variable and internal consistency was good (α = 0.82).

2.3. Procedure

Firefighters completed a voluntary online survey that included questions about stress and mental health. A department-wide email was sent to all firefighters, notifying them of the opportunity to complete an online research survey for one continuing education (CE) credit and a chance to win one of several raffle prizes (e.g., restaurant gift cards, movie theatre passes, drink tumblers). A total of three monthly reminders regarding the survey were sent via the department-wide email notification system. All notification emails indicated that the purpose of the survey was to better understand how firefighters cope with stress and how much firefighters engage in health-related behaviors. The fire department from which these data were obtained employs approximately 4,035 firefighters. Although data collection is ongoing and thus a precise response rate is indeterminable, the 831 firefighters included in this study represent approximately 20.6% of the fire department; importantly, the sociodemographic characteristics of our sample is generally consistent with the sociodemographic characteristics of the fire department as a whole.

Firefighters were given access to the informed consent form and survey through an online fire department CE portal. Once firefighters accessed the fire department CE portal, they were provided with a description of the survey and the opportunity to review the informed consent form. Participants who then indicated that they were interested in participating (by clicking ‘yes’) were automatically directed to the study informed consent form in Qualtrics. Once the participants electronically signed off on the study informed consent form, they were immediately directed to the online survey questionnaires in Qualtrics, which took approximately 45–60 min to complete. Firefighters had the option to discontinue participation at any time without penalty. The current study is based on secondary data analyses of participants who provided data on the variables of interest and has been approved by all relevant institutional review boards.

2.4. Data analytic strategy

Variables were initially screened for outliers and violations of normality. The SBQ-R demonstrated a violation of normality (i.e., skew = 3.015; kurtosis = 11.175). Thus, consistent with past research (Kimbrel et al., 2016; Rogers et al., 2016), we applied a log transformation to the SBQ-R to reduce skew (1.918) and kurtosis (3.179) to acceptable levels. We constructed models both using the transformed and non-transformed SBQ-R variable. For the moderation analyses, we utilized linear regression modeling within the PROCESS macro for SPSS (see Hayes, 2013) to examine the interaction between SOOS-14 occupational stress and DTS distress tolerance in the prediction of SBQ-R suicide risk (total score and individual SBQ-R items). We centered predictor variables around their means and probed significant interactions at low (−1 SD) and high (+ 1 SD) levels of DTS distress tolerance. Analyses controlled for depression symptom severity, as measured by the CES-D (Radloff, 1977) as well as sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., age, race [White = 1, non-White = 0], and sex [Male = 1, nonMale = 0]) that have been shown to be associated with suicide risk among firefighters (Stanley et al., 2015). Missing data were minimal (< 2% for cases included as part of this ongoing study) and handled utilizing listwise deletion. SPSS version 23 was used.

3. Results

See Table 2 for study variable means, standard deviations, normality statistics, and intercorrelations. In the current study, a total of 8.2% (n = 68) of participants exceeded previously established cutoff scores indicating clinically significant suicide risk (i.e., ≥ 7; Osman et al., 2001). In total, 30.6% of participants reported nonzero SBQ-R levels.1

Table 2.

Study Variable Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations (N =831).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | α | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SOOS-14 Occupational Stress | – | 0.92 | 24.57 | 10.33 | 14–70 | |||||||

| 2. DTS Distress Tolerance | −0.137** | – | 0.93 | 4.06 | 0.92 | 1–5 | ||||||

| 3. SBQ-R Suicide Risk (Total Score) | 0.326** | −0.193** | – | 0.77 | 3.85 | 1.79 | 3–16 | |||||

| 4. SBQ-R Item 1 (Lifetime Suicidal Ideation/Attempts) | 0.315** | −0.142** | 0.852** | – | – | 1.30 | 0.59 | 1–4 | ||||

| 5. SBQ-R Item 2 (Past-Year Suicidal Ideation) | 0.265** | −0.227** | 0.823** | 0.620** | – | – | 1.20 | 0.63 | 1–5 | |||

| 6. SBQ-R Item 3 (Lifetime Suicide Threats) | 0.167** | −0.128** | 0.596** | 0.497** | 0.366** | – | – | 1.06 | 0.27 | 1–3 | ||

| 7. SBQ-R Item 4 (Current Suicidal Intent) | 0.252** | −0.116** | 0.830** | 0.559** | 0.515** | 0.373** | – | – | 0.30 | 0.73 | 0–6 | |

| 8. CES-D Depression Symptoms | 0.478** | −0.364** | 0.370** | 0.283** | 0.375** | 0.150** | 0.298** | – | 0.82 | 10.60 | 7.80 | 0–49 |

Note.

p < 0.01.

CES-D=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; DTS=Distress Tolerance Scale SBQ-R=Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire—Revised (SBQ-R); SOOS-14=Sources of Occupational Stress Scale—14.

Please see Table 3 for results from each of our linear regression models testing our hypotheses that SOOS-14 occupational stress would interact with DTS distress tolerance to predict SBQ-R suicide risk (total score and individual items), controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and CES-D depression symptoms. Briefly, the interaction between SOOS-14 occupational stress and DTS distress tolerance was statistically significant for the SBQ-R total score (B = −0.001, SE = 0.001, p = 0.043),2 SBQ-R Item 3 (i.e., lifetime suicide threats; B = −0.002, SE = 0.001, p = 0.040), and SBQ-R Item 4 (i.e., current suicidal intent; B = −0.007, SE = 0.002, p = 0.005). The form of the interactions indicates that higher levels of DTS distress tolerance mitigate the effect of SOOS-14 occupational stress on SBQ-R suicide risk (globally as well as for lifetime suicide threats and current suicidal intent, specifically). The interaction between SOOS-14 occupational stress and DTS distress tolerance was not statistically significant for SBQ-R Item 1 (i.e., lifetime suicidal ideation/attempts; B = −0.003, SE = 0.002, p = 0.140) or SBQ-R Item 2 (i.e., past-year suicidal ideation; B = −0.004, SE = 0.002, p = 0.071).

Table 3.

Results from Linear Regression Analyses Examining Occupational Stress and Distress Tolerance in the Prediction of SBQ-R Suicide Risk Total and Item-Level Scores.

| B | SE | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBQ-R Total Score | |||

| F(7,823) = 25.329, p <0.001; R2 = 17.7%; f2 =0.215 | |||

| Age | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.313 |

| Race (White) | 0.026 | 0.011 | 0.013 |

| Sex (Male) | −0.051 | 0.020 | 0.010 |

| CES-D Depression Symptoms | 0.004 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| DTS Distress Tolerance | −0.013 | 0.005 | 0.021 |

| SOOS-14 Occupational Stress | 0.003 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| SOOS-14 Occupational Stress x DTS Distress Tolerance | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.043 |

| R2 increase due to the interaction: 0.4%, p = 0.043; f2 = 0.004 | |||

| Interaction: −1SD of DTS Distress Tolerance | 0.004 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Interaction: +1SD of DTS Distress Tolerance | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.005 |

| SBQ-R Item 1 (Lifetime Suicidal Ideation/Attempts) | |||

| F(7,823) = 18.391, p <0.001; R2 = 13.5%; f2 =0.156 | |||

| Age | - < 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.918 |

| Race (White) | 0.081 | 0.045 | 0.070 |

| Sex (Male) | −0.179 | 0.084 | 0.033 |

| CES-D Depression Symptoms | 0.011 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| DTS Distress Tolerance | −0.044 | 0.023 | 0.054 |

| SOOS-14 Occupational Stress | 0.013 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| SOOS-14 Occupational Stress x DTS Distress Tolerance | −0.003 | 0.002 | 0.140 |

| R2 increase due to the interaction: 0.2%, p = 0.140; f2 = 0.002 | |||

| Interaction: −1SD of DTS Distress Tolerance | 0.016 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Interaction: +1SD of DTS Distress Tolerance | 0.010 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| SBQ-R Item 2 (Past-Year Suicidal Ideation) | |||

| F(7,823) = 25.785, p <0.001; R2 = 18.0%; f2 =0.220 | |||

| Age | - < 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.896 |

| Race (White) | 0.093 | 0.046 | 0.045 |

| Sex (Male) | −0.294 | 0.087 | <0.001 |

| CES-D Depression Symptoms | 0.022 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| DTS Distress Tolerance | −0.086 | 0.024 | <0.001 |

| SOOS-14 Occupational Stress | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.005 |

| SOOS-14 Occupational Stress x DTS Distress Tolerance | −0.004 | 0.002 | 0.071 |

| R2 increase due to the interaction: 0.3%, p = 0.071; f2 = 0.003 | |||

| Interaction: −1SD of DTS Distress Tolerance | 0.010 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Interaction: +1SD of DTS Distress Tolerance | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.329 |

| SBQ-R Item 3 (Lifetime Suicide Threats) | |||

| F(7,823) = 7.234, p < 0.001; R2 =5.8%; f2 =0.062 | |||

| Age | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.461 |

| Race (White) | 0.004 | 0.021 | 0.869 |

| Sex (Male) | −0.122 | 0.040 | 0.002 |

| CES-D Depression Symptoms | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.379 |

| DTS Distress Tolerance | −0.031 | 0.011 | 0.004 |

| SOOS-14 Occupational Stress | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| SOOS-14 Occupational Stress x DTS Distress Tolerance | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.040 |

| R2 increase due to the interaction: 0.5%, p = 0.040; f2 = 0.005 | |||

| Interaction: −1SD of DTS Distress Tolerance | 0.005 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Interaction: +1SD of DTS Distress Tolerance | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.345 |

| SBQ-R Item 4 (Current Suicidal Intent) | |||

| F(7,823) = 16.517, p <0.001; R2 = 12.3%; f2 =0.140 | |||

| Age | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.051 |

| Race (White) | 0.117 | 0.055 | 0.034 |

| Sex (Male) | −0.067 | 0.104 | 0.522 |

| CES-D Depression Symptoms | 0.020 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| DTS Distress Tolerance | −0.033 | 0.029 | 0.248 |

| SOOS-14 Occupational Stress | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| SOOS-14 Occupational Stress x DTS Distress Tolerance | −0.007 | 0.002 | 0.005 |

| R2 increase due to the interaction: 0.9%, p = 0.005; f2 =0.009 | |||

| Interaction: −1SD of DTS Distress Tolerance | 0.014 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Interaction: +1SD of DTS Distress Tolerance | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.605 |

Note. CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; DTS =Distress Tolerance Scale SBQ-R =Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire—Revised (SBQ-R); SOOS-14 = Sources of Occupational Stress Scale—14.

4. Discussion

Firefighters represent an occupational group at increased risk for suicide, in part due to stressors associated with the nature of their profession. As evidence accumulates for the effects of occupational stress on suicide risk among firefighters, it is important to investigate how individual differences in cognitive-affective variables may moderate this effect. The results of the present study revealed that greater occupational stress was associated with higher global suicide risk and greater lifetime suicide threats and current suicidal intent among firefighters—and, importantly, that this effect was moderated by individual differences in distress tolerance. Notably, although occupational stress exerted a strong influence on lifetime suicide threats and current suicidal intent for individuals low in distress tolerance, the effect of occupational stress on suicide threats and intent was non-significant at high levels of distress tolerance. This finding is particularly significant, given that suicidal intent may more accurately reflect an individual’s current suicidal mode as compared to a confluence of retrospective criteria (cf. SBQ-R total scores comprising past year ideation and lifetime suicide attempts; see Chu et al., 2015). As such, these results indicate important clinical considerations with respect to mitigating the likelihood of future suicide attempts among firefighters with low distress tolerance.

The present study contributes to a growing compendium of research examining suicidality and its correlates among firefighters. Several recent studies have focused on the relationship between PTSD symptoms and suicidality. For instance, PTSD symptom severity is associated with a lifetime history of suicide ideation and prior suicide attempts in two large samples of firefighters (Boffa et al., 2017; Martin et al., 2016). Relevant to the present investigation, two recent studies of firefighters extended these results to show that PTSD symptom severity is related to global suicide risk (Boffa et al., 2018b; Stanley et al., 2017b). The present study expands these findings by broadening the scope of psychological stressors beyond trauma to that which are broadly inherent in the occupation (i.e., SOOS-14 items). Moreover, while past research has found that individual stressors such as harassment (Hom et al., 2017), sleep disturbances (Carey et al., 2011; Hom et al., 2016), and social disconnectedness (Chu et al., 2016) are associated with suicide-related symptoms among firefighter samples, this study extends these results using a more comprehensive index of occupational stress (Kimbrel et al., 2011), including those not previously explored in relation to suicidality among this population. Although SOOS-14 occupational stress scores were higher in the current study than in a previous firefighter sample (VanderVeen et al., 2012), it is worth noting that the previous sample comprised firefighter cadets. As such, the cumulative stress experienced by firefighters throughout their career may not have been captured in that relatively junior population, as compared to our sample (for which the average span of firefighter service was 13.02 years [SD = 8.71 years]).

Beyond the presence of occupational stressors, this study also adds to a nascent body of literature examining the relationship between suicidality and individual differences in perceived ability to tolerate distress. Prior studies have reported associations between low distress tolerance and increased suicidal desire among undergraduates (Anestis et al., 2011) and acute-care psychiatric inpatients (Vujanovic et al., 2017a,b). While the present results extend this pattern to occupational stress and suicide risk as well as lifetime suicide threats and current suicidal intent among firefighters, there are unique considerations regarding the function of distress tolerance among firefighters. DTS distress tolerance scores in the present sample were significantly higher compared to prior reports of trauma-exposed adults in the community (Vujanovic et al., 2013), which we speculate may capture the broader influence of stoicism within the fire service. High distress tolerance is a desirable trait of a firefighter, and it is possible that firefighters are, in part, selected for or self-select into emergency service careers such as the fire service. However, we must consider that examining the range of these traits among firefighters means that some individuals will inevitably possess relatively lower distress tolerance.

Our findings indicated that distress tolerance attenuates the effect of occupational stress on global suicide risk as well as lifetime suicide threats and current suicidal intent, specifically. Perhaps most encouraging, we found that occupational stress did not significantly impact the reported likelihood of making a future suicide attempt for firefighters with higher levels of distress tolerance. A negligible effect of occupational stress on an individual’s current projection of likely suicidal behavior at high levels of distress tolerance is clinically meaningful for assessing, and therefore managing, present risk for a suicide attempt. As distress tolerance is malleable to therapeutic intervention (Zvolensky et al., 2011), intervening upon low distress tolerance may inoculate firefighters against the effects of occupational stress on suicide risk and intent. Various intervention formats, such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT; Becker & Zayfert, 2001; Linehan, 2015) and Skills for Improving Distress Intolerance (SIDI; Bornovalova et al., 2012), have each been shown to improve distress tolerance. Portable computerized modules targeting distress tolerance, which may be most conducive to implementation among firefighters on call or in rural areas, have likewise demonstrated positive effects (Macatee and Cougle, 2015). Despite these modalities for improving distress tolerance, few psychological interventions have been tested among first responders (Haugen et al., 2012), pointing to a critical future direction. A crucial consideration in this domain is that past research has linked high distress tolerance, as measured by a behavioral task, to increased capability for suicide (Anestis and Joiner, 2012)—a construct that the interpersonal theory of suicide theorizes develops in part through exposure to painful and provocative experiences and is necessary but not sufficient for suicidal behaviors (Chu et al., 2017; Van Orden et al., 2010). Put another way, Anestis and Joiner (2012) suggest that the ability to endure distress might facilitate the transition from thinking about suicide to engaging in suicidal behavior. Thus, a focus of clinical work should not be on merely enduring distress but finding healthy ways to mitigate distress (e.g., exercise; see Sawhney et al., 2017).

4.1. Limitations and future directions

Our findings are subject to several limitations. First, we utilized a sample of firefighters from a single, all-career fire department that serves an urban locale. Thus, findings might not generalize to firefighters at large. It is also necessary to highlight that firefighters in this study were all career (compared to volunteer) firefighters because psychiatric symptoms (e.g., suicidal intent) may have been underreported due to fears of job repercussions (cf. Anestis & Green, 2015). Further, we relied exclusively on self-report methodologies. Future research might benefit from the use of behavioral indices of distress tolerance (e.g., physiological reactivity; Nock & Mendes, 2008), rather than merely self-reported psychological distress tolerance. Moreover, the SBQ-R, while a gold standard self-report assessment instrument for suicide risk (Batterham et al., 2015), is limited in that it assesses the concomitant presence of lifetime suicide attempts, past-year suicidal thoughts, and the future likelihood of making a suicide attempt; even more, the single SBQ-R item that assesses for lifetime suicide attempt (i.e., Item 1) simultaneously assesses for lifetime suicidal ideation. In this regard, our findings are unable to distinguish if occupational stress predicts who, among suicide ideators, has made a suicide attempt (cf. the ideation-to-action framework; Klonsky & May, 2014; Klonsky et al., 2016; Nock et al., 2016). Distinguishing between suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors is especially important because there are some data to suggest that high levels of distress tolerance, while protective against suicidal desire, may actually confer increased risk for suicidal behaviors (Anestis et al., 2012; Vujanovic et al., 2017b). We did, however, attempt to address this limitation by examining each SBQ-R individual item, including an item assessing suicidal intent, and observed a consistent pattern of findings. Finally, it is worth noting that our models explained a nontrivial proportion of variance in our suicide-related outcomes, corresponding to effect sizes in the medium-to-large range; however, the additional variance accounted for by our interaction terms, though statistically significant, was relatively smaller in magnitude.

4.2. Conclusions

Among a large sample of firefighters, the present study found that greater occupational stress is associated with elevated levels of global suicide risk as well as lifetime suicide threats and current suicidal intent—and, moreover, that these associations were attenuated at higher levels of self-reported distress tolerance. Given that distress tolerance is amenable to therapeutic intervention, should these results be replicated among other firefighter samples, suicide prevention efforts within the fire service might benefit from the inclusion of distress tolerance skills building (see Linehan, 2015; Zvolensky et al., 2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH93311) as well as the Military Suicide Research Consortium (MSRC), an effort supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs under Award No. (W81XWH-162-0003). Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the MSRC, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

The range of SBQ-R scores is 3–18 (Osman et al., 2001); thus a “nonzero” score on the SBQ-R is > 3.

This pattern of findings remained consistent when utilizing the non-transformed SBQ-R variable as the outcome: the interaction was statistically significant in the expected direction (B=−0.015, SE=0.006, p=0.008).

References

- Association, AmericanPsychiatric, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Bagge CL, Tull MT, Joiner TE, 2011. Clarifying the role of emotion dysregulation in the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior in an undergraduate sample. J. Psychiatr. Res 45, 603–611. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Green BA, 2015. The impact of varying levels of confidentiality on disclosure of suicidal thoughts in a sample of United States national guard personnel. J. Clin. Psychol 71, 1023–1030. 10.1002/jclp.22198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Joiner TE, 2012. Behaviorally-indexed distress tolerance and suicidality. J. Psychiatr. Res 46, 703–707. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Tull MT, Bagge CL, Gratz KL, 2012. The moderating role of distress tolerance in the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters and suicidal behavior among trauma exposed substance users in residential treatment. Arch. Suicide Res 16, 198–211. 10.1080/13811118.2012.695269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterham PJ, Ftanou M, Pirkis J, Brewer JL, Mackinnon AJ, Beautrais A, et al. , 2015. A systematic review and evaluation of measures for suicidal ideation and behaviors in population-based research. Psychol. Assess 27, 501–512. 10.1037/pas0000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton RD, Murphy SA, 1993. Sources of occupational stress among firefighter/EMTs and firefighter/paramedics and correlations with job-related outcomes. Prehosp. Disaster Med 8, 140–150. 10.1017/S1049023X00040218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker CB, Zayfert C, 2001. Integrating DBT-based techniques and concepts to facilitate exposure treatment for PTSD. Cogn. Behav. Pract 8, 107–122. 10.1016/S1077-7229(01)80017-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boffa JW, King SL, Turecki G, Schmidt NB, 2018a. Investigating the role of hopelessness in the relationship between PTSD symptom change and suicidality. J. Affect. Disord 225, 298–301. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boffa JW, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Norr AM, Joiner TE, Schmidt NB, 2017. PTSD symptoms and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among firefighters. J. Psychiatr. Res 84, 277–283. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boffa JW, Stanley IH, Smith LJ, Mathes BM, Tran JK, Buser SJ, et al. , 2018b. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and suicide risk in male firefighters: the mediating role of anxiety sensitivity. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 206, 179–186. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Gratz KL, Daughters SB, Hunt ED, Lejuez CW, 2012. Initial RCT of a distress tolerance treatment for individuals with substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend 122, 70–76. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MG, Al-Zaiti SS, Dean GE, Sessanna L, Finnell DS, 2011. Sleep problems, depression, substance use, social bonding, and quality of life in professional firefighters. J. Occup. Environ. Med 53, 928–933. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318225898f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton RN, Afifi TO, Turner S, Taillieu T, Duranceau S, LeBouthillier DM, et al. , 2017. Mental disorder symptoms among public safety personnel in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 10.1177/0706743717723825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter GSJ, Carpenter TP, Kimbrel NA, Flynn EJ, Pennington ML, Cammarata C, et al. , 2015. Social support, stress, and suicidal ideation in professional firefighters. Am. J. Health Behav 39, 191–196. 10.5993/AJHB.39.2.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu S, Webber MP, Zeig-Owens R, Gustave J, Lee R, Kelly KJ, et al. , 2010. Validation of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale in screening for major depressive disorder among retired firefighters exposed to the world trade center disaster. J. Affect. Disord 121, 212–219. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Hom MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE, 2016. A test of the interpersonal theory of suicide in a large sample of current firefighters. Psychiatry Res 240, 26–33. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Tucker RP, Hagan CR, et al. , 2017. The interpersonal theory of suicide: a systematic review and metaanalysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychol. Bull 143, 1313–1345. 10.1037/bul0000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Klein KM, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Hom MA, Hagan CR, Joiner TE, 2015. Routinized assessment of suicide risk in clinical practice: an empirically informed update. J. Clin. Psychol 71, 1186–1200. 10.1002/jclp.22210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith J, Schulz J, Wakeham R, Schultz M, 2016. A replication of the 2008 U.S. national report card study on women in firefighting. Bus. Rev 24, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen PT, Evces M, Weiss DS, 2012. Treating posttraumatic stress disorder in first responders: a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev 32, 370–380. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson SN, Van Hasselt VB, LeDuc TJ, Couwels J, 2016. Firefighter suicide: understanding cultural challenges for mental health professionals. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract 10.1037/pro0000072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hom MA, Stanley IH, Rogers ML, Tzoneva M, Bernert RA, Joiner TE, 2016. The association between sleep disturbances and depression among firefighters: emotion dysregulation as an explanatory factor. J. Clin. Sleep Med 12, 235–245. 10.5664/jcsm.5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hom MA, Stanley IH, Spencer-Thomas S, Joiner TE, 2017. Women firefighters and workplace harassment. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 205, 910–917. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, Pennington ML, Cammarata CM, Leto F, Ostiguy WJ, Gulliver SB, 2016. Is cumulative exposure to suicide attempts and deaths a risk factor for suicidal behavior among firefighters? A preliminary study. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav 46, 669–677. 10.1111/sltb.12248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, Steffen LE, Meyer EC, Kruse MI, Knight JA, Zimering RT, et al. , 2011. A revised measure of occupational stress for firefighters: psychometric properties and relationship to posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and substance abuse. Psychol. Serv 8, 294–306. 10.1037/a0025845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, May AM, 2014. Differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators: a critical frontier for suicidology research. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav 44, 1–5. 10.1111/sltb.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, May AM, Saffer BY, 2016. Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol 12, 307–330. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A, 2010. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: a review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychol. Bull 136, 576–600. 10.1037/a0019712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, 2015. DBT® Skills Training Manual, Second Edition. Guilford Press, New York, NY, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Macatee RJ, Cougle JR, 2015. Development and evaluation of a computerized intervention for low distress tolerance and its effect on performance on a neutralization task. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 48, 33–39. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall-Berenz EC, Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ, 2010. Multimethod study of distress tolerance and PTSD symptom severity in a trauma-exposed community sample. J. Trauma. Stress 23, 623–630. 10.1002/jts.20568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CE, Tran JK, Buser SJ, 2016. Correlates of suicidality in firefighter/EMS personnel. J. Affect. Disord 208, 177–183. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh WL, Spies E, Stone DM, Lokey CN, Trudeau A-RT, Bartholow B, 2016. Suicide rates by occupational group — 17 States, 2012. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 65, 641–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Kessler RC, Franklin JC, 2016. Risk factors for suicide ideation differ from those for the transition to suicide attempt: The importance of creativity, rigor, and urgency in suicide research. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract 23, 31–34. 10.1111/cpsp.12133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Mendes WB, 2008. Physiological arousal, distress tolerance, and social problem-solving deficits among adolescent self-injurers. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 76, 28–38. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM, Konick LC, Kopper BA, Barrios FX, 2001. The suicidal behaviors questionnaire-revised (SBQ-R): validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment 8, 443–454. 10.1177/107319110100800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS, 1977. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas 1, 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ML, Tucker RP, Law KC, Michaels MS, Anestis MD, Joiner TE, 2016. Manifestations of overarousal account for the association between cognitive anxiety sensitivity and suicidal ideation. J. Affect. Disord 192, 116–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford K, Kruse MI, Proctor A, Torres VA, Pennington ML, Synett SJ, et al. , 2017. Couple resilience and life wellbeing in firefighters. J. Posit. Psychol 12, 660–666. 10.1080/17439760.2017.1291852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney G, Jennings KS, Britt TW, Sliter MT, 2017. Occupational stress and mental health symptoms: examining the moderating effect of work recovery strategies in firefighters. J. Occup. Health Psychol 10.1037/ocp0000091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, 2005. The distress tolerance scale: development and validation of a self-report measure. Motiv. Emot 29, 83–102. 10.1007/s11031-005-7955-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley IH, Hom MA, Hagan CR, Joiner TE, 2015. Career prevalence and correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among firefighters. J. Affect. Disord 187, 163–171. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley IH, Hom MA, Joiner TE, 2016. A systematic review of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among police officers, firefighters, EMTs, and paramedics. Clin. Psychol. Rev 44, 25–44. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley IH, Hom MA, Spencer-Thomas S, Joiner TE, 2017a. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among women firefighters: an examination of associated features and comparison of pre-career and career prevalence rates. J. Affect. Disord 221, 107–114. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley IH, Hom MA, Spencer-Thomas S, Joiner TE, 2017b. Examining anxiety sensitivity as a mediator of the association between PTSD symptoms and suicide risk among women firefighters. J. Anxiety Disord 50, 94–102. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley IH, Joiner TE, Bryan CJ, 2017c. Mild traumatic brain injury and suicide risk among a clinical sample of deployed military personnel: evidence for a serial mediation model of anger and depression. J. Psychiatr. Res 84, 161–168. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiesman HM, Konda S, Hartley D, Menéndez CC, Ridenour M, Hendricks S, 2015. Suicide in U.S workplaces, 2003–2010. Am. J. Prev. Med 48, 674–682. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor, 2015. Firefighters [WWW Document]. Occup. Outlook Handb URL. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/protective-service/firefighters.htm accessed 10.18.17.

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE, 2010. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev 117, 575–600. 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderVeen JW, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB, Kruse MI, Kamholz BW, Zimering RT, et al. , 2012. Differences in drinking patterns, occupational stress, and exposure to potentially traumatic events among firefighters: predictors of smoking relapse. Am. J. Addict 21, 550–554. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Bakhshaie J, Martin C, Reddy MK, Anestis MD, 2017a. Posttraumatic stress and distress tolerance: Associations with suicidality in acute-care psychiatric inpatients. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 205, 531–541. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Berenz EC, Bakhshaie J, 2017b. Multimodal examination of distress tolerance and suicidality in acute-care psychiatric inpatients. J. Exp. Psychopathol 8, 376–389. 10.5127/jep.059416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Potter CM, Marshall EC, Zvolensky MJ, 2011. An evaluation of the relation between distress tolerance and posttraumatic stress within a trauma-exposed sample. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess 33, 129–135. 10.1007/s10862-010-9209-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Hart AS, Potter CM, Berenz EC, Niles B, Bernstein A, 2013. Main and interactive effects of distress tolerance and negative affect intensity in relation to PTSD symptoms among trauma-exposed adults. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess 35, 235–243. 10.1007/s10862-012-9325-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A, Vujanovic AA, 2011. Distress Tolerance: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. Guilford Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]