Abstract

In this review we bring together three different lines of evidence to bear on the issue of local shaping of function in the motor cortex. The first line of evidence comes from the description by Cajal (1911) of the recurrent collaterals of pyramidal cell axons in the precentral gyrus. The second line of evidence comes from the electrophysiological study of the functional effects of these collaterals (Stefanis and Jasper, 1964a,b) and associated interneurons (Stefanis, 1969) using intracellular recordings. And third came the discovery of directional tuning in the motor cortex (Georgopoulos et al., 1982) in the behaving monkey. We hazard the hypothesis that the bell-shaped directional tuning curve is the outcome of orderly, local neuronal interactions in the motor cortex in which the recurrent pyramidal cell collaterals play a crucial role. Specifically, we propose that these collaterals and the intercalated interneurons they impinge upon serve to spatially sharpen the motor cortical activation to a locus corresponding to the direction of the intended movement. Thus, the originally proposed role of the pyramidal cell collaterals in enhancing “motor contrast” (Stefanis, 1969) would translate to creating a “directional tuning field” on the motor cortical surface, where the enhanced motor contrast would correspond to high activity at the center of directional field, and the suppression of the fringe would correspond to lower activity at the periphery of the field, resulting, together in spatial tuning.

Keywords: Motor cortex, Recurrent collaterals, Directional tuning, Local circuit

1. Introduction

Cajal devoted only a small section of his monumental Textura (1904) to the precentral cortex; yet, he perceptively identified the presence and described in detail the distribution of the recurrent collaterals of the pyramidal cells. Fifty-three years later, the functional role of these collaterals in the motor cortical network was investigated using intracellular recording techniques (Stefanis and Jasper, 1964a,b). Since then, additional morphological (Sloper, 1973; Gatter and Powell, 1978; Sloper and Powell, 1979; Sloper et al., 1979; Lund et al., 1993; DeFelipe et al., 1986a,b; Somogyi et al., 1998) and electrophysiological (Takahashi et al., 1967; Kang et al., 1988; Ghosh and Porter, 1988) studies have led, overall, to a more detailed description of the local neuronal network in the motor cortex. In parallel, studies of the relations of motor cortical neuronal activity to movement in the behaving monkey led to the discovery of directional tuning (Georgopoulos et al., 1982; Schwartz et al., 1988): a cell would discharge at high rates for movements in a particular direction (the cell’s “preferred direction”) and at progressively lower rates for movements farther and farther away from the preferred direction. This orderly variation of cell activity with the direction of movement is characterized by the directional tuning curve, a bell-shaped, cosine-function curve with a peak at the cell’s preferred direction. How does directional tuning arise? What is the cellular basis for the directional tuning curve? We propose the hypothesis that the directional tuning curve is the result of local neuronal interactions in which the recurrent collaterals of the pyramidal cell axons play a crucial, formative role. In that what follows we first review the literature on the morphology and cellular electrophysiology of the local (“canonical”) motor cortical network and then examine the hypothesis above in the light of studies of the columnar arrangement (Georgopoulos et al., 1984; Amirikian and Georgopoulos, 2003) and tangential representation of the preferred direction in the motor cortex of the monkey (Naselaris et al., 2005, 2006).

2. Morphology of the Local Motor Cortical Network

A detailed description of the cellular elements in the motor cortex was given by Sloper (1973), Sloper et al. (1979) and by Somogyi et al. (1998). Basically, 72% of the neurons are pyramidal cells and 28% are presumed interneurons (Sloper et al., 1979). Of the latter, 21% are small stellate cells, probably excitatory, and 7% are large stellate cells, probably inhibitory. A detailed electron microscopic study of the site of cellular contact made by degenerating thalamocortical and corticocortical fibers (commissural from the opposite sensorimotor cortex, ipsilateral premotor area 6, and ipsilateral somatosensory cortex, SI) following lesions of the respective areas (Sloper and Powell, 1979) revealed a common pattern with some systematic variations, as follows. (a) All afferent inputs above are presumably excitatory, since degenerating terminals had asymmetric membrane specializations. (b) The large majority of all inputs made synapses on to dendritic spines of pyramidal cells (89.5% from thalamus, 96% from commissural, 76% from area 6, and 82% from SI). (c) The remaining terminals made synapses on to dendritic shafts (9% of thalamic, 3% of commissural, 24% of area 6, and 18% of SI afferents), and very few on to cell somata, of mostly large stellate cells. Given that these large stellate (basket) cells are GABAergic (DeFelipe et al., 1986b) and inhibitory (Szabadics et al., 2006; in contrast, GABAergic axo-axonic cells can also be excitatory), the following two important points can be made. First, all inputs above to the motor cortex address simultaneously excitatory and inhibitory mechanisms. And second, the relative excitatory : inhibitory bias differs for different inputs. Specifically, the ratio of pyramidal : large stellate cell terminations from the thalamus (90% : 9%) is very close to that of the cell counts (72% : 7%). This argues for a more or less even distribution of thalamocortical terminations across cortical layers. In contrast, commissural input is biased towards pyramidal cell terminations (96% : 3%), whereas inputs from SI and area 6 are biased towards inhibitory mechanisms (76% ; 24% for area 6, and 82% : 18% for SI). On a topographic level, afferent inputs to the motor cortex are characterized by a large amount of convergence from thalamic and cortical sources (Darian-Smith and Darian-Smith, 1993).

Various morphological aspects of the motor cortical network have been investigated using different methods. Cajal (1911), using Golgi impregnation, noted the presence of recurrent pyramidal axon collaterals and their extensive distribution, and Lorente de Nó (1949) further amplified on them. Lund et al. (1993), using Golgi impregnation, biocytin labeling and cytochrome oxidase staining, described patches of intrinsic connectivity and stressed the role of inhibition in shaping local patterns of activity. DeFelipe at al. (1986a), using injections of horseradish peroxidase, described the multi-focal nature of long-range connections from SI to motor cortex. Finally, Gatter and Powell (1978) made very small lesions by inserting microelectrodes in the motor cortex and examined the resulting distribution of degenerating fibers. They found a zone of dense fine terminal degeneration for a radius of 200 to 300 μm all around the lesion. These fibers arose from within the cortex and occupied, horizontally, the boundary of layers II and III and layer of Betz cells. A smaller degree of degeneration was present for a further 2 to 3 mm.

3. Electrophysiology of the Local Motor Cortical Network

Various electrophysiological studies have complemented the morphological picture above in delineating some basic functional aspects of the motor cortical network. Phillips (1959), recording intracellularly from pyramidal cells, demonstrated transient changes of transmembrane polarization elicited by (antidromic) stimulation of the pyramidal tract even at current strengths low enough to prevent excitation of adjacent lemniscal fibers. Stefanis and Jasper (1964a,b) investigated in detail the excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (EPSP and IPSP, respectively) elicited by electrical stimulation of the pyramidal tract and cerebral peducles. They studied in detail the nature of the postsynaptic potential in 94 cells recorded from intracellularly in the motor cortex of the cat (Stefanis and Jasper, 1964a, Table 1, p. 833). Polarizing potentials (pure IPSPs) were elicited in approximately 30/94 (31.9%) cells. Depolarizing potentials were elicited in 22/94 (23.4%) cells (13/22 identified as EPSPs and 9/22 as of undetermined nature); in many cases these initial depolarizing potentials were followed by polarizing potentials (IPSPs). In a small percentage of cells (7/94, 7.5%) the kind of synaptic potential elicited could vary (polarizing or depolarizing) depending on the parameters of the antidromic stimulation and/or the functional state of the neuron. Finally, 13/94 (13.8%) cells did not show any substantial changes in membrane polarization irrespective of the parameters of stimulation.

The inhibitory effects were investigated in more detail (Stefanis and Jasper, 1964b) by testing systematically the changes in membrane excitability and potential of single intracellularly recorded pyramidal tract cells at different time intervals following a conditioning stimulus (single shock or brief train of repetitive, near-threshold brief shocks) applied to the descending axons of pyramidal tract cells. The results obtained demonstrated the following. (a) They documented the occurrence of IPSPs; (b) they provided strong evidence for the mediation of the recurrent inhibition by inhibitory interneurons intercalated between the pyramidal axon collateral (stimulated) and the pyramidal cell recorded from; (c) they provided strong evidence for the recurrent IPSPs being exerted close to the spike-triggering zone, in accordance to recent morphological demonstration of inhibitory axo-axonic synapses (Somogyi et al., 1998); and (d) they suggested that a synchronous increase in both spatiotemporal summation and temporal dispersion underlie the (i) shortening of the onset time of inhibition, (ii) the shortening of time to its peak, (iii) the increase of its strength, and (iv) the increase of its duration, all effected by increasing the parameters of the conditioning stimulus. Finally, and most importantly, these studies provided quantitative measurements of inhibition parameters: onset time of recurrent inhibition 5–20 ms, time to maximum inhibition ~20 ms, and duration of inhibition up to 80–100 ms. The recurrent inhibition is obviously mediated by intercalated interneurons. A study of such presumed inhibitory interneurons (Stefanis, 1969) revealed that the recurrent input and the inputs from other sources (the thalamus or cortex) converged on the same interneuron. In addition, the approximate location of most of interneurons studied was just below layer III (Stefanis, 1969, Fig. 262, p. 518), where most of the large stellate cells are found (Sloper and Powell, 1979).

4. The Motor Contrast Enhancement Hypothesis

Based on the considerations above, it was proposed that a major role of recurrent collateral inhibition in the motor cortex is the spatial sharpening of the focus of excitation (Stefanis and Jasper, 1964b; Stefanis, 1969): “[T]he motor cortex is functionally organized with respect to specific synaptic drives into overlapping receptive fields encircling clusters of PT neurons [neurons with axons traveling in the pyramidal tract] which can be functionally differentiated within the field by their response characteristics to afferent stimulation; some responding with repetitive or single discharges and others with subliminal excitation. Since collateral activity is exerted primarily by volleys in extraneous axons, it follows from the above considerations that recurrent inhibition will be derived mainly from PT neurons, the strategic location of which in the receptor field favors repetitive discharges and will mainly affect the excitability and discharge activity of neurons in the fringe of the receptive field where afferent excitation is weak and easily antagonized by recurrent collateral inhibition.” (Stefanis and Jasper, 1964b, p. 874). Then, the motor contrast hypothesis was formulated as follows: “Recurrent inhibition is primarily exerted upon the less active or even subliminally excited PT neurons on the fringe of the receptive field. Such a distribution of recurrent inhibition within the receptive field enhances ‘motor contrast’, prevents spread of excitation to wide cortical areas and facilitates precise activation. On the other hand, recurrent facilitation seems to be weak and seems to be exerted primarily upon the very active PT cells in the center of the field by the less active PT cells located at the fringe of the receptive field. This topographical arrangement of the facilitatory input will supplement recurrent inhibition by enhancing motor contrast” (Stefanis, 1969, p. 505). This idea was similar to that proposed for the Renshaw cells in spatial sharpening of motoneuronal excitation in the spinal cord (Baldissera et al., 1981). The innovation of the motor contrast hypothesis above lay in emphasizing the spatial effect of the recurrent collateral inhibition and excitation. This aspect was lost in subsequent studies which attempted to distinguish recurrent effects based on the conduction velocity of pyramidal tract neurons (Takahashi et al., 1967; Kang et al., 1988; Ghosh and Porter, 1988). Although those observations were probably correct, the latter interpretation of them did not lead to a better understanding of motor cortical organization. As pointed out by Stefanis (1969, p. 505), “[I]t is not so much the size of the PT neuron,…, but its position with respect to the receptive field and its discharge frequency which will determine if it will exert an inhibitory or facilitatory action upon the neighboring PT cells.”. Now, if the motor contrast hypothesis is correct, what exactly is the “motor contrast”? What would be that aspect of the movement that would create a focus of excitation surrounded by decreasing excitation and/or increasing inhibition? We propose that this is the direction of the movement.

5. The Directional Tuning Field

Our hypothesis is that the changes in cell activity observed in a fixed location with movements in different directions reflect the shifting locus of a canonical, spatially sharpened directional tuning field. We postulate that this directional field corresponds to the synaptic receptive field of Stefanis and Jasper (1964b). The center of the directional field is occupied by the direction of the intended movement; excitatory and inhibitory mechanisms, driven mainly by recurrent pyramidal cell collaterals, shape the field, from the center to its periphery. Two main questions arise: first, what is the shape of the directional field, and, second, how that shape is produced. To answer these questions, we draw on the results of past (Georgopoulos et al., 1982; Schwartz et al., 1988) and recent (Naselaris et al., 2005, 2006) studies of directional tuning in the motor cortex.

A cell’s preferred direction is that direction of movement for which the cell would discharge at the highest rate. Preferred directions are organized in cortical columns (Amirikian and Georgopoulos, 2003), are multiply represented in the motor cortex (Georgopoulos et al., 1984; Schwartz et al., 1988; Naselaris et al., 2006), and are surrounded by other preferred directions (Naselaris et al., 2006). In terms of the cortical landscape, when a movement in a specific direction is to be made, the highest activity on the motor cortical surface will be in those loci where preferred directions coincide with the intended movement direction. If a microelectrode is placed in one of these loci and the activity of a single cell is recorded, a certain rate of discharge will be recorded. Now, if the activity of the same cell is recorded when movements in different directions are made, an orderly gradation of activity is obtained (Georgopoulos et al., 1982; Schwartz et al., 1988), such that activity decreases progressively for movements in directions progressively away from the cell’s preferred direction (Fig. 1), i.e. as the angle between the cell’s preferred direction and the particular movement increases.

Fig. 1.

Raster activity of a single cell recorded in the motor cortex of a monkey during movements on a plane in different directions, indicated by the arrows at the center. T, range of target onset. Rasters are aligned to M, movement onset. Notice the short-latency, abrupt decrease of activity for movement direction at 2 o’clock. (Adapted from Georgopoulos et al., 1982)

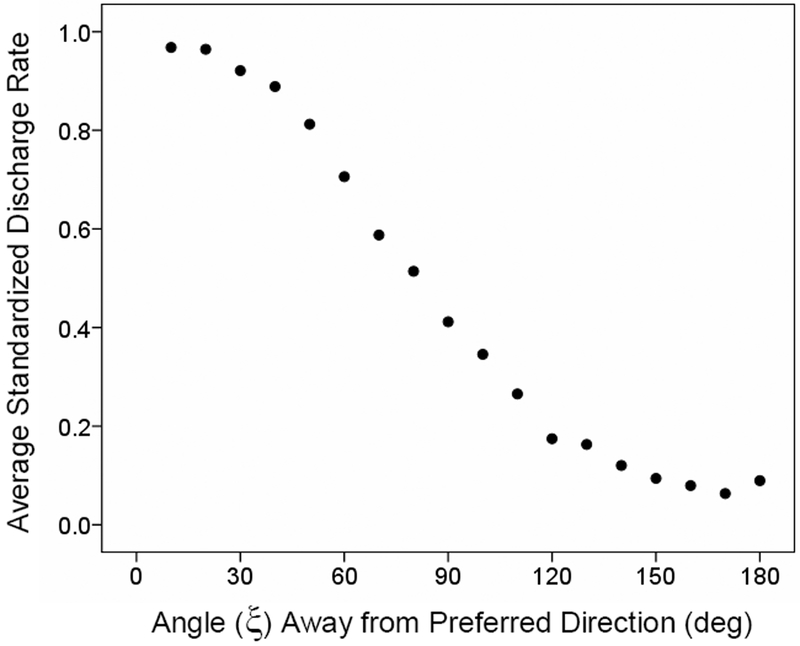

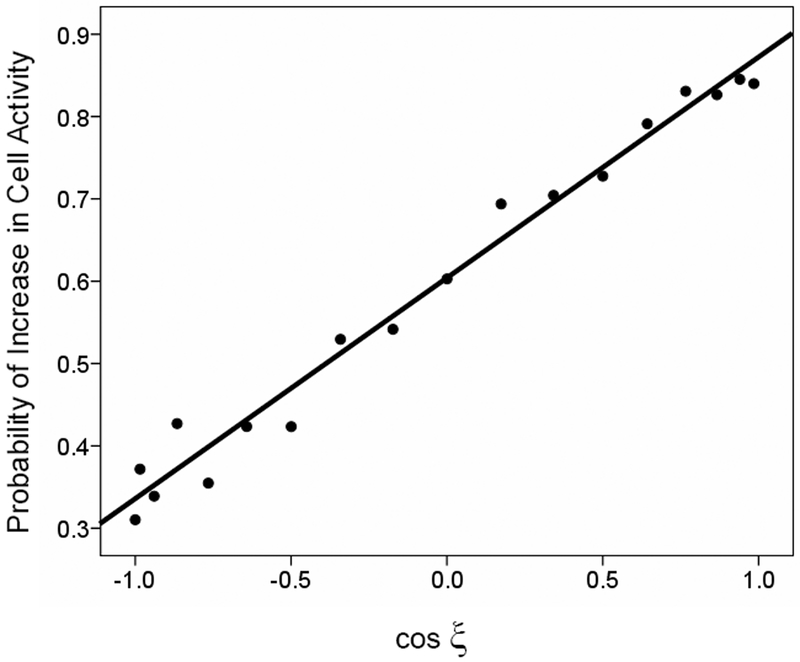

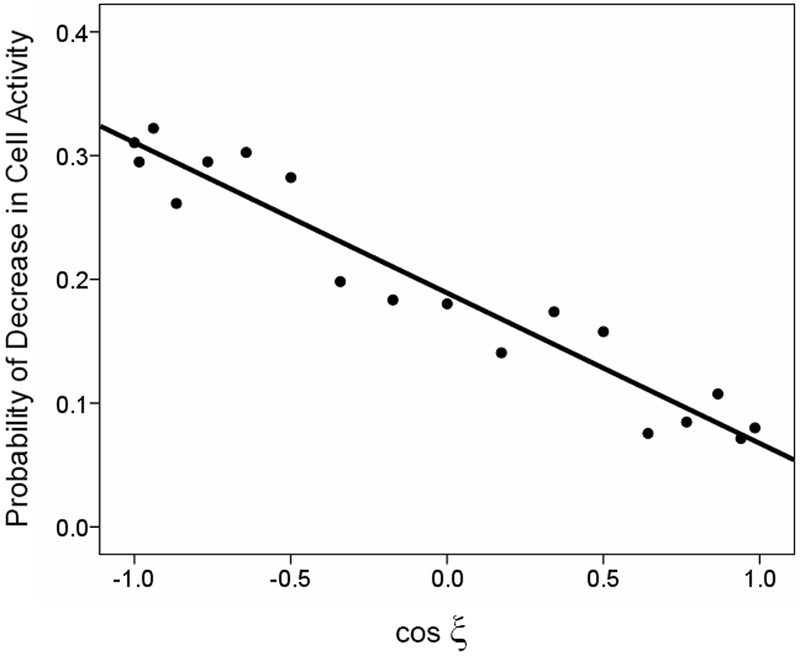

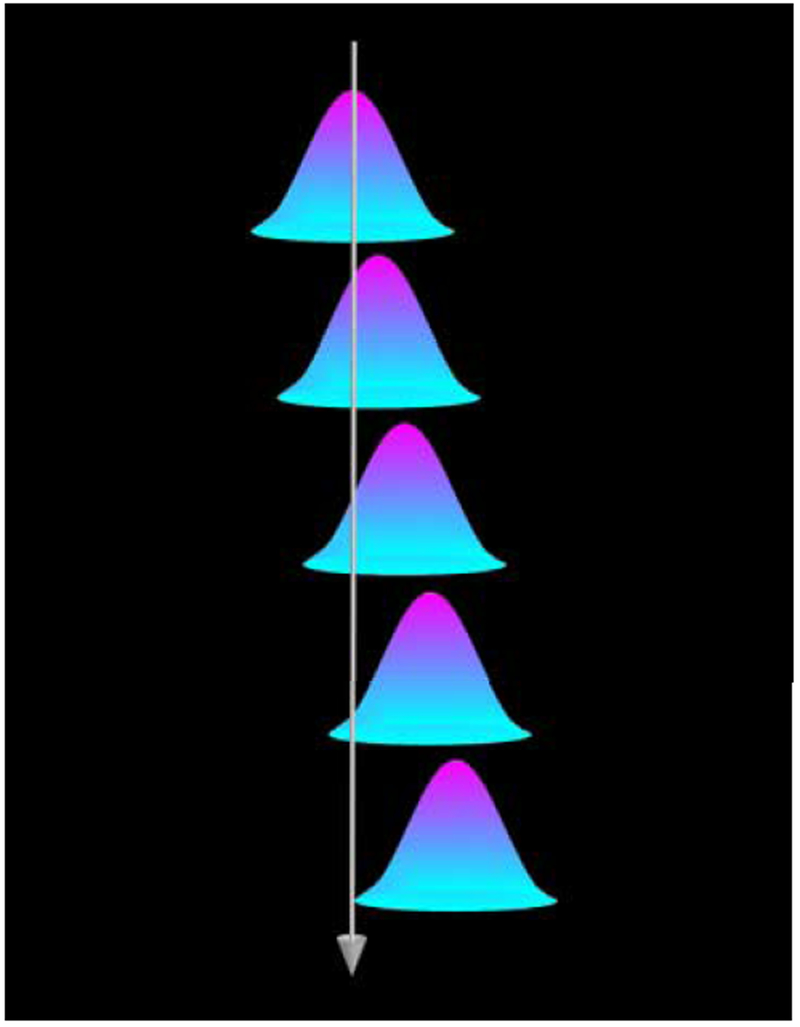

There are two relevant quantitative measures regarding cell activity within the directional field. The first measure concerns the quantification of the relation between the average discharge rate and the direction of movement. This is the bell-shaped directional tuning curve. This means that the rate of cell discharge decreases as a function of the cosine of the angle between the cell’s preferred direction and the direction of a particular movement. An average, standardized tuning curve derived from many free, 3D reaching movements is shown in Fig. 2; it is an excellent cosine fit. The second measure concerns the probability of increase, decrease or no change in discharge as a function of the angle between the preferred direction and directions away from it (see Fig. 6 in Georgopoulos et al., 1982). To calculate this measure, the preferred direction of each cell in the population is determined as well as the kind of the first statistically significant change from background activity (i.e. increase, decrease, or no change). Then, the relative frequency of occurrence of each one of the three kinds of change is calculated for movement directions away from the preferred direction. Thus, for each such direction, these frequencies can be regarded as probabilities of occurrence of the three kinds of change, summing to one. Although inhibition cannot be distinguished from disfacilitation using extracellular recordings, we will assume, for the current purposes, that increase or decrease of activity from a steady-state background activity indicate the occurrence of excitation or inhibition, respectively. (Lack of change in activity could reflect a true absence, or a balance, of excitatory and inhibitory effects.) Now, the ideal directional tuning field can be visualized as a circular field on the motor cortical surface with (a) a specific direction at its center, (b) directions at 180 deg angle from it at its circumference, and (c) directions at other angles in between, in an orderly progression from small to large, as one moves from the center to the periphery. Then, the probabilities of increase and decrease in activity (Figs. 3–4) can be superimposed on that field (Fig. 5, top) to derive probabilistic estimates of the spatial distribution of excitation and inhibition within the directional tuning field. We believe that this emerging picture is in keeping with the basic aspects of the “motor contrast” theory above, if only one would rename it to “directional contrast”!

Fig. 2.

Average standardized tuning curve calculated from 568 directionally tuned cells in 3D space (Schwartz et al., 1988). There were 8 average discharge rates for each cell. These rates were standardized to vary from 0 to 1 by subtracting the minimum and dividing by the range, and then averaged per 10-deg bins of the angle ξ between a particular movement and the preferred direction. B, the average rates above are plotted against the cosine of ξ. The regression equation was: Discharge rate = 0.48 + 0.471 cosξ (R2 = 0.991, p < 10−15).

Fig. 3.

Directional tuning of the probability of increase in cell activity from the preceding control period. The probability of increase is plotted against the cosine of ξ. The regression equation was: Prob(increase) = 0.603 + 0.268 cosξ (R2 = 0.990, p < 10−15). All statistical analyses were done using the SPSS statistical package for Windows, version 15 (Chicago, IL).

Fig. 4.

Directional tuning of the probability of decrease in cell activity from the preceding control period. The probability of increase is plotted against the cosine of ξ. The regression equation was: Prob(decrease) = 0.189 − 0.121 cosξ (R2 = 0.927, p < 10−10). The function for probability of no change in activity was very similar: Prob(no change) = 0.208 − 0.148 cosξ (R2 = 0.979, p < 10−12).

Fig. 5.

A 3D visualization of the canonical directional tuning field/motor contrast on the motor cortical surface calculated as the net algebraic sum of the Prob(increase) and Prob(decrease) functions above. The arrow indicates the fixed position of a microelectrode recording from a cell for which the preferred direction coincides with the direction at the center of the field. The displaced directional tuning field indicates activation of other preferred directions farther and farther away from that of the top, such that ξ increases from left to right. It is hypothesized that the directional tuning curve of the recorded cell reflects the progressively decreasing influence of the spatially moving away directional tuning field, visualized, e.g., as the length of the line crossing the directional tuning field at a particular location.

The synaptic mechanisms underlying the shaping of the directional tuning curve remain to be elucidated. In other cortical areas, there is conflicting evidence on the role of GABA-mediated inhibition which is important for frequency tuning in the auditory cortex (Jen et al., 2002) but not for stimulus-size tuning in the visual cortex (Ozeki et al., 2004). GABA-mediated inhibition is also crucial in shaping auditory tuning curves in subcortical structures (Yajima and Hayashi, 1990; Yang et al., 1992). The effects on the width of the directional tuning curve of local injection of bicuculline, a GABA antagonist, in the motor cortex could provide valuable information in that context.

6. Conclusions: The Spatial Origin of the Directional Tuning Curve

The directional tuning curve (Fig. 2) is obtained by recording the activity of a cell during movements in various directions. Based on the considerations advanced in the previous section, we propose that the directional tuning curve reflects the changing engagement of a cell as the directional tuning field of a given direction changes location on the cortical surface with movements in different directions. Since the same cell is being recorded from during these movements, i.e. the location of the microelectrode in the cortical surface is fixed, and since the cortical center of activation (and associated field above) will change, depending on the current movement direction, we hypothesize that the characteristics of neuronal activity (its intensity and kind of change) reflect the position of the cell within the currently active directional tuning field (Fig. 5). This field, in turn, is initiated by strong, synchronous external inputs but is shaped mainly by the action of the recurrent pyramidal cell collaterals. Based on statistical averaging calculations (Amirikian and Georgopoulos, 2003), the width of the field seems to be of the order of 200–250 μm and the width of a single directional cortical minicolumn (Mountcastle, 1997) of the order of 30–50 μm. The regularity of the directional tuning field and the repeating representation of movement direction in the motor cortex provide a rich substrate not only for the corticospinal control of movement but also for the orderly interaction of the motor cortex to subcortical and other cortical areas.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by USPHS grant NS17413, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the American Legion Brain Sciences Chair.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amirikian B, Georgopoulos AP 2003. Modular organization of directionally tuned cells in the motor cortex: Is there a short-range order? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 100, 12474–12479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltissera F, Hultborn H, Illert M 1981. Integration in spinal neuronal systems In: Handbook of Physiology, Section 1: The nervous system, vol. II: Motor control, part 1, Brookhart JM and Mountcastle VB (eds.), American Physiological Society, Bethesda, MD, pp. 513–518. [Google Scholar]

- Cajal SR 1904. Textura del Sistema Nervioso del Hombre y de los Vertebrados Tomo II. Librería de Nicolás Moya, Madrid, Spain, pp. 903–912. [Google Scholar]

- Darian-Smith C, Darian-Smith I 1993. Thalamic projections to areas 3a, 3b, and 4 in the sensorimotor cortex of the mature and infant macaque monkey. J. Comp. Neurol 335, 173–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J, Conley M, Jones EG 1986a. Long-range focal collateralizaton of axons arising from corticocortical cells in monkey sensory-motor cortex. J. Neurosci 6, 3749–3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J, Hendry SHC, Jones EG 1986b. A correlative electro microscopic study of basket cells and large gabaergic neurons in the monkey sensory-motor cortex. Neuroscience 17, 991–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Nó Lorente. 1949. Cerebral cortex: Architecture, intracortical connections, motor projections In: Physiology of the nervous system, Fulton FJ (ed.), Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 289–330. [Google Scholar]

- Gatter KC, Powell TPS 1978. The intrinsic connections of the cortex of area 4 of the monkey. Brain 101, 513–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos AP, Kalaska JF, Caminiti R, Massey JT 1982. On the relations between the direction of two-dimensional arm movements and cell discharge in primate motor cortex. J. Neurosci 2, 1527–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos AP, Kalaska JF, Crutcher MD, Caminiti R, Massey JT 1984. The representation of movement direction in the motor cortex: Single cell and population studies In: Dynamic aspects of neocortical function, Edelman GM, Cowan WM and Gall WE (eds.), John Wiley and Sons, New York, pp. 501–524. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Porter R 1988. Morphology of pyramidal neurons in monkey motor cortex and the synaptic actions of their intracortical axon collaterals. J. Physiol. (London) 400, 593–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jen PH, Chen QC, Wu FJ 2002. Interaction between excitation and inhibition affects frequency tuning curve, response size and latency of neurons in the auditory cortex of the big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus. Hear Res. 174: 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Endo K, Araki T 1988. Excitatory synaptic actions between pairs of neighboring pyramidal tract cells in the motor cortex. J. Neurophysiol 59, 636–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund JS, Yoshioka T, Levitt JB 1993. Comparison of intrinsic connectivity in different areas of macaque monkey cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex 3, 148–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountcastle VB 1997. The columnar organization of the neocortex. Brain 120, 701–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naselaris T, Merchant H, Amirikian B Georgopoulos AP 2005. Spatial reconstruction of trajectories of an array of recording microelectrodes. J. Neurophysiol 93, 2318–2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naselaris N,, Merchant H, Amirikian B and Georgopoulos AP 2006. Large-scale organization of preferred directions in the motor cortex. II. Analysis of local distributions. J. Neurophysiol 96, 3237–3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozeki H, Sadakane O, Akasaki T, Naito T, Shimegi S, Sato H 2004. Relationship between excitation and inhibition underlying size tuning and contextual response modulation in the cat primary visual cortex. J Neurosci. 24:1428–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips CG 1959. Actions of antidromic pyramidal volleys on single Betz cells in the cat. Quart. J. Exp. Physiol 44, 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AB, Kettner RE, Georgopoulos AP 1988. Primate motor cortex and free arm movements to visual targets in three-dimensional space. I. Relations between single cell discharge and direction of movement. J. Neurosci 8, 2913–2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloper JJ 1973. An electron microscopic study of the neurons of the primate motor and somatic sensory cortices. J. Neurocytol 2, 351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloper JJ, Powell TPS 1979. An experimental electron microscopic study of afferent connections to the primate motor and somatic sensory cortices. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. London B Biol. Sci 285, 199–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloper JJ, Hiorns RW, Powell TPS 1979. A qualitative and quantitative electron microscopic study of the neurons in the primate motor and somatic sensory cortices. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. London B Biol. Sci 285, 141–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P, Tamás G, Lujan R, Buhl EH 1998. Salient features of synaptic organization in the cerebral cortex. Brain Res. Rev 26, 113–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P, Freund TF, Cowey A 1982. The axo-axonic interneuron in the cerebral cortex of the rat, cat, and monkey. Neuroscience 7: 2577–2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanis C, Jasper H 1964a. Intracellular microelectrode studies of antidromic responses in cortical pyramidal tract neurons. J. Neurophysiol 27, 828–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanis C, Jasper H 1964b. Recurrent collateral inhibition in pyramidal tract neurons. J. Neurophysiol 27, 855–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanis C 1969. Interneuronal mechanisms in the cortex In: The Interneuron, Brazier MAB (ed.), Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp. 497–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabadics J, Varga C, Molnár G, Oláh S, Barzó P, Tamás G 2006. Excitatory effect of GABAergic axo-axonic cells in cortical microcircuits. Science 311: 233–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Kubota K, Uno M 1967. Recurrent facilitation in cat pyramidal tract cells. J. Neurophysiol 30, 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yajima Y, Hayashi Y 1990. GABAergic inhibition upon auditory response properties of neurons in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the rat. Exp. Brain Res. 81: 581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Pollak GD, Resler C 1992. GABAergic circuits sharpen tuning curves and modify response properties in the mustache bat inferior colliculus. J. Neurophysiol 68: 1760–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]